Abstract

Background:

To examine current clinical research on the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in the treatment of pediatric and young adult autism spectrum disorder in intellectually capable persons (IC-ASD).

Methods:

We searched peer-reviewed international literature to identify clinical trials investigating TMS as a treatment for behavioral and cognitive symptoms of IC-ASD.

Results:

We identified sixteen studies and were able to conduct a meta-analysis on twelve of these studies. Seven were open-label or used neurotypical controls for baseline cognitive data, and nine were controlled trials. In the latter, waitlist control groups were often used over sham TMS. Only one study conducted a randomized, parallel, double-blind, and sham controlled trial. Favorable safety data was reported in low frequency repetitive TMS, high frequency repetitive TMS, and intermittent theta burst studies. Compared to TMS research of other neuropsychiatric conditions, significantly lower total TMS pulses were delivered in treatment and neuronavigation was not regularly utilized. Quantitatively, our multivariate meta-analysis results report improvement in cognitive outcomes (pooled Hedges’ g=0.735, 95% CI=0.242, 1.228; p=0.009) and primarily Criterion B symptomology of IC-ASD (pooled Hedges’ g=0.435, 95% CI=0.359, 0.511; p<0.001) with low frequency repetitive TMS to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Conclusions:

The results of our systematic review and meta-analysis data indicate that TMS may offer a promising and safe treatment option for pediatric and young adult patients with IC-ASD. However, future work should include use of neuronavigation software, theta burst protocols, targeting of various brain regions, and robust study design before clinical recommendations can be made.

Keywords: Autism, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, Pediatric, Neurodevelopmental, Neuromodulation, Brain Stimulation

Background:

Since the first studies of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults offered evidence of therapeutic response with excitatory high frequency rTMS (HF-rTMS) (≥10 Hz) of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (LtDLPFC), (George, 1995; Milev, 2016; Pascual-Leone, 1996; Rossi, 2009) interest in the therapeutic opportunity of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has grown as have options for TMS modalities. Anti-depressant response to of inhibitory low frequency rTMS (LF-rTMS) (≤1 Hz) of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (RtDLPFC) has been demonstrated, (Klein, 1999) though greater evidence supports MDD treatment via HF-rTMS of the LtDLPFC. (Lefaucheur, 2014) Theta burst stimulation (TBS) is another therapeutic TMS treatment with patterned pulses delivered in bursts of three at a higher frequency compared to rTMS (50Hz). TBS requires less stimulation time, functions at a lower overall intensity compared to rTMS protocols, with promising safety profiles in pediatric patients based on a recent systematic review. (Elmaghraby et al., 2021) Two patterns of TBS are currently utilized, the inhibitory continuous (cTBS) and excitatory intermittent (iTBS). (Chung et al., 2015) Options for delivering “deep TMS” (dTMS) further into cortical tissue have been explored as well. Rather than the traditional figure eight coil, dTMS uses the double cone coil and the H-coil were developed to allow for greater depth of cortical penetration. (Carmi et al., 2018; Tofts & Branston, 1991) Safe and efficacious use of dTMS has been demonstrated, resulting in FDA approval to treat MDD as well as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) via stimulation of medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). (Berlim et al., 2014; Blomstedt et al., 2013; Carmi et al., 2018, 2019; Levkovitz et al., 2015) Given these robust findings, as well as emerging protocols documenting the safety, efficacy, non-invasive nature, and ease of administration of TMS as a neuromodulatory treatment in both adult and pediatric patients, (Allen et al., 2017; Connolly, 2012; Damji et al., 2013; Milev, 2016; Rajapakse & Kirton, 2013; Rossi, 2009) there is a growing interest regarding the possibility of using TMS for other neuropsychiatric conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder which presents with deficits in social interaction and communication along with restricted/repetitive pattern of behaviors and interests (RRBs). (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) The condition is highly prevalent, affecting 1-2% of the population worldwide. (Lazoff et al., 2010) Individuals may present with or without intellectual disability, though substantial supports are often required in either case. (Howlin et al., 2004; Tillmann et al., 2019) Despite the burden of disease on individuals and health systems, (Becker et al., 2020) issues of diagnosis and treatment persist due to under-recognition, (Joshi et al., 2010) heterogeneity in clinical phenotypes, and the variability of symptom manifestation across development. (Jannati et al., 2020) Additionally, current pharmacologic interventions in ASD are limited to the management of co-occurring psychopathology and not for the core features of the disorder. (Hutton, 2008; Zhou et al., 2021)

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analytic research investigating the use of TMS and other neuromodulatory techniques in treatment and diagnosis (Jannati et al., 2021) of ASD regardless of age or intellectual capacities, suggest that TMS could be effective in the diagnosis of ASD, treatment of RRBs, and improving executive functioning (EF) deficits. However, heterogeneity in study design and possible publication bias are notable limiting factors in making clinical recommendations, points further highlighted in recent consensus statements by Oberman and Cole. (Barahona-Correa, 2018; Cole et al., 2019; Khaleghi et al., 2020; Oberman & Enticott, 2015) In this study, we aim to further advance current knowledge regarding the use of TMS by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature with a focus on TMS as a therapeutic tool for intellectually capable individuals with ASD (IC-ASD) with the purpose of developing future TMS trials which would advance and optimize the therapeutic potential of TMS. We have chosen a younger patient population for this TMS review due to the developmental nature of the disorder (Oberman, Pascual-Leone, et al., 2014), increasing prevalence rates of IC-ASD in this patient population, (Maenner, 2020), potential for greater effects of TMS early in development when the brain is considered to be more plastic, (Oberman & Enticott, 2015) and to mitigate study design heterogeneity by focusing on a specific population of individuals with ASD. Our study also further advances the literature by including studies published since the seminal 2018 meta-analysis by Barahona-Correa and colleagues. (Barahona-Correa, 2018) To our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis exists which specifically investigates TMS as a therapeutic tool in the management of pediatric and young adults with IC-ASD.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed international literature utilizing the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Our review was conducted via PubMed and EMBACE published through 03/22/2022 using the following search criteria: [Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation or TMS] AND [Autism Spectrum Disorder or Autism or ASD]. The authors screened, reviewed, and assessed the reference lists of the retrieved papers to ensure that all relevant articles were included in our review. Bibliographies were also cross referenced to ensure that no articles were missed. Our review was not registered. Following publication, our meta-analysis data and code will be publicly available on the Open Science Framework.

All articles were screened for predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria by four authors. Authors worked collaboratively on each article selected, no automation tools were utilized Articles were included if they met the following criteria: (1) original research in a peer-reviewed journal, (2) the study sample included individuals below 18 years of age with IC-ASD, (3) investigated TMS as a therapeutic modality in the management of IC-ASD via open label trials, controlled trials, or cross over studies, and (4) devices used in the study were FDA-approved for sale in the United States. Articles were excluded if they met the following exclusion criteria: (1) ASD sample with intellectual disability (IQ < 65), (2) focused on other disorders that were not ASD, (3) studied transcranial direct current stimulation or utilized TMS practices other than rTMS or TBS, (4) published in a language other than English, (5) did not include interpretable data, (6) were purely diagnostic in study design or (7) performed a literature review or meta-analysis. Notably, studies were included which investigated individuals above 18 years of age if the study population also contained individuals below 18 years.

Statistical Methods:

We performed two meta-analyses of standardized mean differences (SMD) in studies which conducted LF-rTMS to the DLPFC: one for behavioral outcomes and one for cognitive outcomes. To compute the SMDs, we extracted either the mean difference and standard deviation of the difference or the baseline and endpoint means and standard deviations, t-statistics, and p-values for each outcome. Given the small sample sizes of the included studies and the dependent nature of our comparison groups (pre-TMS vs. post-TMS), the standardized mean difference was calculated as Hedges’ g for pre-post scores using the following formula: ; and the accompanying sample variance was calculated as (Borenstein, 2009), where is the pre-treatment mean score, is the post-treatment mean score, is the within group standard deviation, df is the degrees of freedom used to estimate , and N is the sample size (# of pairs). The correlation coefficient, r, for pre-post scores was calculated as (Barahona-Correa, 2018). For studies where insufficient information was available to calculate r, we imputed r using the average of all the calculated correlations. Only studies that provided sufficient data to make these calculations were included in the meta-analysis. Ten studies measuring behavioral outcomes (Casanova et al., 2012, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2012, 2018) and eight studies measuring cognitive outcomes (Casanova et al., 2014, 2020; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2016, 2018; Wang et al., 2016) possessed data for inclusion. As attempts to obtain unpublished data from the authors of the studies with insufficient data were unsuccessful, they were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Given the dependencies among effect sizes, our analyses utilized random-effects multivariate meta-analysis models using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method with unstructured between-study covariance matrices as implemented in Stata (meta mvregress) (Statacorp, 2021). Due to the small number of effect sizes included in the meta-analysis, we applied Jackson-Riley adjustments to the standard errors of the regression coefficients, which are multivariate generalizations of the Knapp-Hartung adjustment in univariate meta-regression (Jackson & Riley, 2014; Statacorp, 2021). Our models utilized within-study standard errors and within-study correlations to define the within-study covariance matrices. Because our outcomes of interest were derived from only two rating scales (ABC and RBS-R) and one cognitive test (Kaniza Oddball Test), we assumed high within-study correlations between our outcomes and set the correlations to 0.8. We used the Cochran multivariate Q-test to assess the total heterogeneity across all effect sizes. A significant Q-test suggests that the effect sizes analyzed are not estimating the same population effect size. We quantified the amount of between-study variance using the Jackson-White-Riley I2 index (I2JWR) (Jackson et al., 2012).The value of this multivariate heterogeneity statistic lies between 0 and 100 and estimates the percentage of variation among effect sizes that can be attributed to heterogeneity. Additionally, since the multivariate meta-regression command (meta mvregress) in Stata provides pooled effect sizes for subdomains only and not an overall effect, we utilized the robumeta command which estimates an overall effect size by implementing meta-regression with robust variance estimation; (Hedges et al., 2010; Statacorp, 2021). When used in conjunction, the meta mvregress and robumeta commands are complement in terms of what the other is lacking. Thus, when reporting results, estimates for each subdomain were calculated using the meta mvregress command and overall estimates were calculated using the robumeta command.

We used the Egger method and funnel plots to assess for small-study effects and publication bias (Egger et al., 1997) and used selection models to correct for publication bias based on reported p-values (Iyengar & Greenhouse, 1988; Vevea & Hedges, 1995). The selection models were implemented using JASP (JASP Team, n.d.).While these statistics assessing and correcting for small-study effects and publication bias can provide some insight, they are univariate approaches and do not take into account the dependencies of effect sizes. Thus, the results should be interpreted with some caution.

Lastly, we estimated multivariate meta-analysis regression model with the effect sizes as the dependent variables and total number of pulses administered (standardized) as the independent variable. The variable for total pulses tested whether the magnitude of effect significantly differed as total pulses increased. All multivariate meta-analyses were two-tailed and performed at the 0.05 alpha level using Stata: Version 17 (Statacorp, 2021).

Results:

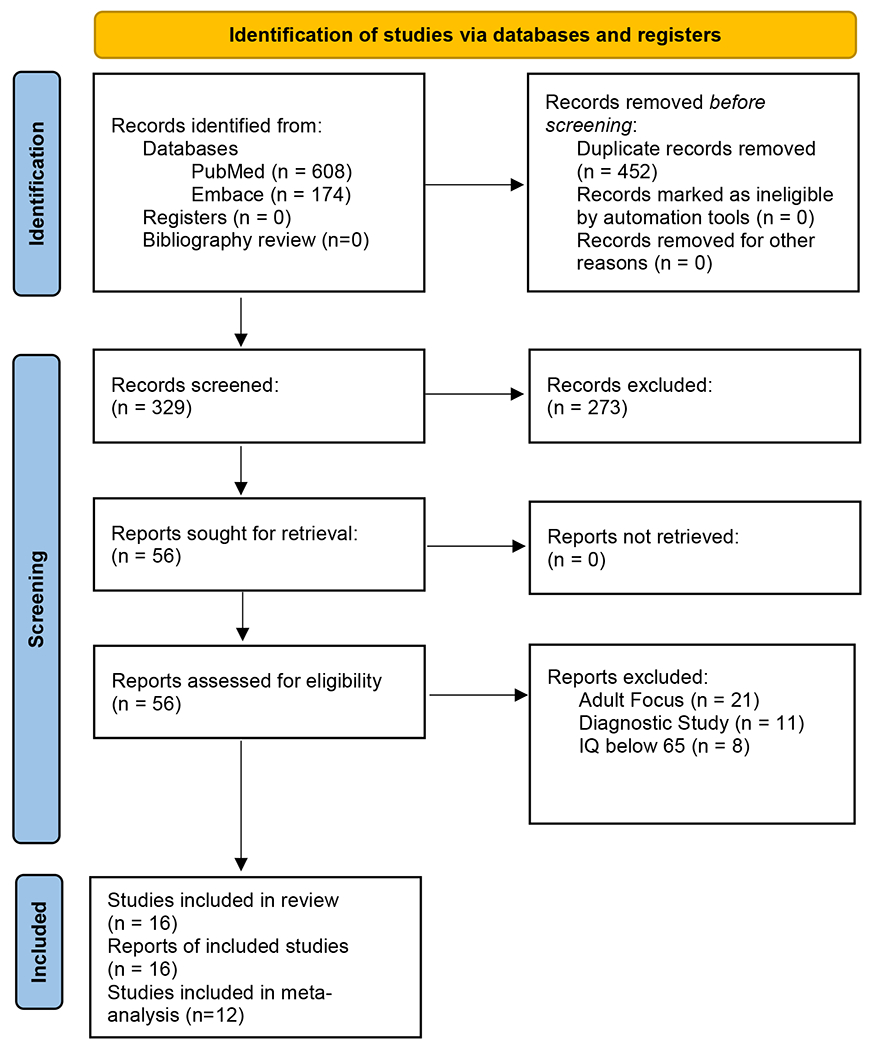

As outlined in Figure 1, in our initial search 782 articles were screened. 329 articles remained for screening after duplicates were removed. Of these, 90 were not specific to IC-ASD, 123 investigated interventions other than TBS or rTMS, 55 were review or opinion articles, 4 were non-human, and 1 was not available in English. 56 articles were assessed for full text eligibility; 21 focused primarily on adults, 11 were purely diagnostic in their focus, and 8 included individuals with intellectual impairment (IQ < 65). Thus, 16 articles were included for final qualitative synthesis. Of those 16 articles, 12 utilized LF-rTMS targeting the DLPFC, incorporated waitlist control groups which had no statistically significant changes in symptoms over the study duration, had extractable base and endpoint data and were thus, included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).

**If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Qualitative Review Summary:

Qualitative results of our review are outlined in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 includes studies with waitlist control groups and sham TMS controls. Table 2 includes studies without a control group and those which included baseline neurotypical (NT) controls. In studies reviewed, sample sizes ranged from an n=13 (E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009) to n=124. (E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2018) The maximum age of participants was 23 years with the single exception being the study by Ameis and colleagues which had a maximum age of 35 years and an average age of 22.6 years. (Ameis et al., 2020) Biologic sex was reported in all studies, with 105 females and 471 males with autism included in the research. Regarding assessment of intellectual capacities, 1/16 studies did not report quantitative measures of IQ, but identified patients as IC-ASD via DSM-IV. (Enticott, 2012) The diagnosis of IC-ASD was confirmed by clinical assessment and use of DSM-IV or DSM-V criteria based on the year the study was conducted in all studies. The autism diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R) was incorporated in 14/16 studies (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) and the autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS) in 2/9. (Ameis et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2021) See Tables 1 and 2 for ascertainment criteria of each study.

Table 1:

Qualitative Summary of Included Studies with Waitlist or Sham Controls

| Study | Age | N | Ascertainment criteria | Demographics Study Design | TMS Hz or TBS | Target and Duration | Treatment frequency | Total Pulses | Blinding Control | Behavioral Outcome | Cognitive Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. M. Sokhadze 2009 3 weeks Open label trial |

17.2 +/− 4.6 |

13 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥85 |

0 female 13 male 8 TMS group 5 waitlist |

0.5 | LtDLPFC 3 weeks |

2/week | 900 | Unblinded Waitlist Non-ASD control group for initial comparisons |

ABC: ↓ hyperactivity RBS-R: ↓ total score SRS: NR Within group outcomes |

No significant difference was observed post TMS in error rate |

|

Casanova 2012 12 weeks Open label trial |

13.0 +/−2.7 |

45 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

6 female 39 male 25 TMS group 20 waitlist |

1 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks |

Weekly | 1,800 | Unblinded Waitlist |

ABC: ↓ irritability RBS-R: ↓ restricted and repetitive behaviors, total score SRS: No statistically significant change Within group outcomes |

Error rate: ↓ omission error rate and total error rate |

|

Enticott 2012 3 weeks Open label trial |

17.6 +/− 4.1 |

11 | ASD; ADI-R IQ not formally tested, but IC-ASD per DSM-5 |

0 female 11 male Cross-over study |

1 | Left M1 SMA |

3/week alternating targets or sham | 2,700 | Unblinded Sham TMS |

No behavioral outcomes | Movement time rTMS to the SMA and left M1 was found to be associated with a gradient increase to the early component and late component of MRCPs respectively |

|

E. M. Sokhadze 2012 12 weeks Open label trial |

13.5 +/− 2.5 |

40 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥75 |

8 female 32 male 20 TMS group 20 waitlist |

1 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks |

Weekly | 1,800 | Unblinded Waitlist |

No behavioral outcomes | Error rate: ↓ omission error rate and total error rate |

| E. M. Sokhadze 2014a 18 weeks Open label trial |

14.5 +/− 2.9 |

54 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

10 female 44 male 27 TMS group 27 waitlist |

1 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 3,240 | Unblinded Waitlist |

ABC: ↓ hyperactivity and irritability RBS-R: ↓ stereotyped behaviors and total score Within group outcomes |

Error rate: ↓ commission error rate and total error rate |

| E. M. Sokhadze 2014b 18 weeks Open label trial |

14.6 +/− 3.1 |

42 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

8 female 34 male 20 TMS group 22 Waitlist |

1 20 mins post treatment received neurofeedback |

LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 3,240 | Unblinded Waitlist |

ABC: ↓ hyperactivity and social withdrawal/lethargy RBS-R: ↓ ritualistic, stereotyped behaviors, and total score SRS: NR Within group outcomes |

Error rate: ↓ commission error rate and total error rate |

|

E. M. Sokhadze 2018 18 weeks Open label trial [Continuation of 2009 study] |

13.1 | 106 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

19 female 87 male 80 TMS group 26 waitlist |

1 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 6-week arm N=25; 1,080 12- week arm N=27; 2,160 18-week arm N=28; 3,240 |

Unblinded Waitlist |

ABC: ↓ hyperactivity, irritability, and social withdrawal/lethargy RBS-R: ↓ Ritualistic, stereotyped behaviors, and total score Within group outcomes Reported only at baseline and 18 weeks of treatment |

Error rate: ↓ commission., omission, and total error rate |

|

Ameis 2020 4 weeks Randomized control trial |

22.6 +/− 4.5 |

40 | ASD; ADOS IQ ≥70 Significant EF impairment |

12 female 28 male |

20 | BiDLPFC 0-4 weeks |

5/week | 30,000 | Double blinded Sham TMS |

No behavioral outcomes | BRIEF-SR CANTAB No evidence for the efficacy of active for sham rTMS for the improvement of EF was found. However, rTMS was found to be effective in the treatment of EF deficits in ASD persons with more severe adaptive functioning deficits. |

|

Ni 2021 8 weeks Randomized control trial |

13.0 +/− 2.8 |

75 | ASD; ADOS IQ ≥70 ADHD co-morbidity included |

10 female 65 male Two groups: 4 weeks sham then active (sham-active) and no sham (active-active) |

iTBS | Bilateral pSTS 0-8 weeks |

2/week | Sham-active 19,200 Active-active 38,400 |

Single Blinded Sham TBS |

RBS-R: ↓ total score SRS: ↓ autistic mannerisms, social communication, and total score Between group outcomes Clinical response not observed in sham-active group |

No cognitive outcomes |

NR: Not reported

Table 2:

Qualitative Summary of Included Studies without Controls or with Neurotypical Controls

| Study | Age | N | Ascertainment criteria | Demographics Study Design | TMS Hz or TBS | Target and Duration | Treatment frequency | Total Pulses | Behavioral Outcome | Cognitive Outcome | Other Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. M. Sokhadze 2010 3 weeks Open label trial |

15.6 +/− 5.8 |

13 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

1 female 12 male |

0.5 | LtDLPFC 3 weeks |

2/week | 900 | RBS-R: ↓ total score SRS and ABC: Not statistically significant |

Error Rate: ↓ total error rate | |

|

Casanova 2014 18 weeks Open label trial |

13.1 +/− 2.2 |

18 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

4 female 14 male |

0.5 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 2,880 | ABC: ↓ irritability and hyperactivity RBS-R: ↓ stereotypic behaviors and total score |

No cognitive outcomes | Improved autonomic dysregulation. Changes in SCL and HRV were positively correlated with improvement in RBS-R and ABC scores |

|

Wang 2016 12 weeks Open label trial |

12.9 +/− 3.8 |

33 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥65 |

5 female 28 male |

0.5 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks |

Weekly | 1,920 | ABC: ↓ stereotypic behavior and hyperactivity RBS-R: ↓ stereotypic behaviors, ritualistic / sameness, and total score |

No cognitive outcomes | Improved autonomic dysregulation. Changes in SCL and HRV were positively correlated with improvement in RBS-R and ABC scores |

|

E. M. Sokhadze 2016 18 weeks Open label trial Initial cognitive data compared to neurotypical controls |

13.6 +/− 3.2 |

23 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

6 female 17 male |

1 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 3,240 | ABC: ↓ hyperactivity, lethargy/social withdrawal, irritability RBS-R: ↓ stereotypic behaviors, ritualistic / sameness, compulsive behavior, and total score |

Error rate: ↓ commission error rate and total error rate | |

|

G. E. Sokhadze 2017 18 weeks Open label trial |

12.5 +/− 2.9 |

27 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

6 female 21 male |

0.5 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 2,880 | ABC: ↓ hyperactivity, lethargy/social withdrawal, inappropriate speech RBS-R: ↓ stereotypic behaviors, ritualistic / sameness, compulsive behavior, and total score SRS-2: : ↓ social awareness and social cognition |

No cognitive outcomes | Improved autonomic dysregulation. Changes in SCL and HRV were positively correlated with improvement in RBS-R and ABC scores |

|

Casanova 2020 18 weeks Open label trial Initial cognitive data compared to neurotypical controls |

14.4 +/− 3.6 |

19 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

5 female 14 male |

1 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 3,240 | ABC: ↓ irritability and hyperactivity RBS-R: ↓ stereotypic behaviors, compulsive behaviors, and total score |

Error rate: ↓ commission error rate and total error rate | |

|

Casanova 2021 18 weeks Open label trial Initial cognitive data compared to neurotypical controls |

14.2 +/− 3.6 |

19 | ASD; ADI-R IQ ≥80 |

5 female 14 male |

1 | LtDLPFC 0-6 weeks RtDLPFC 7-12 weeks BiDLPFC 12-18 weeks |

Weekly | 3,240 | ABC: ↓ irritability, hyperactivity, and lethargy/social withdrawal RBS-R: ↓ stereotypic behaviors, ritualistic / sameness, and compulsive behaviors |

Error Rate: ↓ total error rate |

Study Design:

As seen on Table 1, 9/16 studies incorporated control groups for the duration of the study which included waitlist groups in 6/9 (Casanova et al., 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2012, 2018) and sham TMS in 3/9. (Ameis et al., 2020; Enticott, 2012; Ni et al., 2021) Randomization occurred in 7/9 studies; (Ameis et al., 2020; Casanova et al., 2012; Enticott, 2012; Ni et al., 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2012, 2018) the two studies which were not randomized assigned patients to the waitlist control based on commitment to the research and feasibility of follow up. (E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009) 7/9 were unblinded trials. (Casanova et al., 2012; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2012, 2018) Ni and colleagues conducted a randomized, single blind and sham controlled trial. (Ni et al., 2021) Ameis and colleagues conducted the lone randomized, parallel, double blind, and sham controlled trial. (Ameis et al., 2020)

As seen on Table 2, 7/16 studies did not use control groups for the duration of the study. (Casanova et al., 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2010, 2016; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) 3/7 incorporated the use of NT controls. (Casanova et al., 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2016) Notably, NT controls were not exposed to TMS. Rather, they underwent cognitive testing to compare initial results in the IC-ASD group to NT controls; only IC-ASD participants were exposed to TMS. 3/7 studies also investigated autonomic dysregulation in response to LF-rTMS and found improvement in autonomic measures such as skin conductance level (SCL) and heart rate variability (HRV) which was positively correlated with improvements in behavioral measures. (Casanova et al., 2014; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016)

TMS Parameters:

15/16 studies used rTMS (Ameis et al., 2020; Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) with 14/15 being LF-rTMS (0.5-1 Hz). (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) Ameis and colleagues were the only study to investigate the effects of HF-rTMS, utilizing 20 Hz of stimulation. (Ameis et al., 2020) The DLPFC was targeted in 14/16 studies: (Ameis et al., 2020; Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) specifically the LtDLPFC in 13/16, RtDLPFC in 11/16, and bilateral DLPFC (BiDLPFC) in 9/16. The 2012 study by Enticott and colleagues represents the only study to modulate the left primary motor cortex (M1) and the supplemental motor area (SMA). The study was cross-over in design with participants receiving either Left M1, SMA, and sham TMS over three weekly sessions. (Enticott, 2012) Ni and colleagues conducted the only TBS study, using the excitatory iTBS protocol (Huang et al., 2005) to stimulate the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) bilaterally. Specific information regarding dosing schedules can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

Of studies which targeted the DLPFC, the site of TMS modulation was 5 cm anterior, and in the parasagittal plane, to site of first dorsal interossei muscle (FDI) maximal stimulation in 13/14 studies. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) Studies by Ameis and Ni incorporated MRI guided individual neuronavigation. (Ameis et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2021; Rusjan et al., 2010) Additionally, compared to other studies investigated, the studies by Ni and Ameis administered significantly more total TMS pulses over the study period; delivering 30,000 rTMS pulses over a 4 week course of treatment (Ameis et al., 2020) and 38,400 iTBS pulses over an 8 week period, respectively. (Ni et al., 2021) Comparatively, the next highest number of pulses recorded were 3,240 occurring over an 18-week period. This was done in 6/14 studies targeting the DLPFC. (Casanova et al., 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2016, 2018) While no significant adverse effects or seizures were reported over all studies investigated, only the studies by Ni and Ameis reported specific adverse effects. Both studies reported mild and transient side effects, the most frequent of which was mild headache and pain at the TMS application site. (Ameis et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2021)

Outcome Measures:

9/16 studies measured cognitive and behavioral outcomes of TMS intervention; (Casanova et al., 2012, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2016, 2018) 3/16 exclusively investigated cognitive measures (Ameis et al., 2020; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2012) and 4/16 exclusively behavioral measures. (Casanova et al., 2014; Ni et al., 2021; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) Behaviorally, the social responsiveness scale (SRS-2) (Constantino & Gruber, 2012) was included in 6/16 behavioral studies (Casanova et al., 2012; Ni et al., 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017) and reported in 4/6, (Casanova et al., 2012; Ni et al., 2021; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2010; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017) repetitive behavioral scale-revised (RBS-R) (Lam & Aman, 2007) was used in all thirteen studies, and the aberrant behavioral checklist (ABC) (Aman et al., 1985) was used in 12/13. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) Of those which reported SRS-2 results, Sokhadze 2010 and Casanova 2012 found no significant changes in SRS-2 measures in response to LF-rTMS of the LtDLPFC or of the LtDLPFC and RtDLPFC, respectively. (Casanova et al., 2012; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2010) Sokhadze 2017 reported statistically significant reductions in the SRS-2 domains of social awareness and social cognition at the end of the 18-week trial. (G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017) Ni and colleagues, observed statistically significant improvement in the total SRS-2 score at 8 weeks following iTBS treatments to the bilateral STS following the open-label phase of the study in the active-active group (8 weeks of active treatment), but not in sham-active group (4 weeks of active treatment). Baseline SRS-2 score in the active-active group 107.3 (24.0) at week 1 to 98.5 (28.7) at week 8. Notably, when divided into subdomains, statistically significant improvement in the SRS-2 scale was observed only in the domains of autistic mannerisms and social communication in the active-active group. (Ni et al., 2021) Post-TMS results from the RBS-R were reported in all thirteen studies with only one study not reporting a reduction in total score. (Casanova et al., 2021) Regarding subscales, reductions in stereotypic, ritualistic, and compulsive subscales were reported in 8/13, 6/13, and 4/13 studies, respectively. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2016; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) Notably, similar to their SRS-2 findings, Ni and colleagues reported reductions in total RBS-R score by week 8 in the active-active group of their study; improvements were not observed in the sham-active group. (Ni et al., 2021) Results from the ABC were reported in 11/13 studies; statistically significant reductions in hyperactivity, irritability, social withdrawal / lethargy, stereotypic behavior, and inappropriate speech were reported in 10/13, 7/13, 5/13, 1/13, and 1/13 studies, respectively. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016)

12/16 studies investigated cognitive outcomes (Ameis et al., 2020; Casanova et al., 2012, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018) with 10/12 incorporating use of event related potentials (ERP) via the Kanizsa oddball task. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018) The task involves the presentation of targets, non-targets, and distracters for the participant to identify. Behavioral response changes which occur during the task are then measured. They include the following: ERP, reaction time, error rates, and accuracy. (Kanizsa, 1976) In these studies, the rate of commission, omission, and total errors was measured pre- and post-TMS after subjects were exposed to the Kanizsa oddball task. Improvements in the rate of omission, commission, and total errors were reported in 3/10, 5/10, and 8/10 studies, respectively. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018) In their assessment of cognitive outcomes, Ameis and colleagues were the lone study (Ameis et al., 2020) to use the Behavioral Rating Inventory for Executive Function (BRIEF)-Self Report (SR) Version or BRIEF-Adult, (Rosenthal et al., 2013) the CANTAB spatial working memory task, (CANTAB Cognitive Research Software, n.d.) and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale–II (VABS-II), a standardized measure of daily functioning. (Sparrow & Cicchetti, 1985) Overall, they found no significant difference between active and sham rTMS on EF, defined as the higher order cognitive functions necessary for flexibly shifting focus, regulating and controlling behavior, and working memory. (Pellicano, 2012). However, individuals with lower baseline adaptive functioning per the VABS-II experienced significant improvement in the active vs sham rTMS group. (Ameis et al., 2020) Lastly, the 2013 study by Enticott and colleagues which investigated the use of LF-rTMS to the left primary motor cortex and SMA sought to improve movement-related cortical potentials (MRCP) often impaired in IC-ASD. (Enticott, 2012; Rinehart et al., 2006) rTMS to the SMA and left primary motor strip was found to be associated with a gradient increase to the early component and late component of MRCPs respectively. Overall, they noted that this improvement in movement related electrophysiological activity may be due to LF-rTMS influence on cortical inhibitory processes. (Enticott, 2012)

Meta-Analysis Results:

Of the 16 articles identified, twelve had extractable data for meta-analysis of behavioral and/or cognitive outcomes in patients administered TMS treatment. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; Wang et al., 2016)

Behavioral Outcomes:

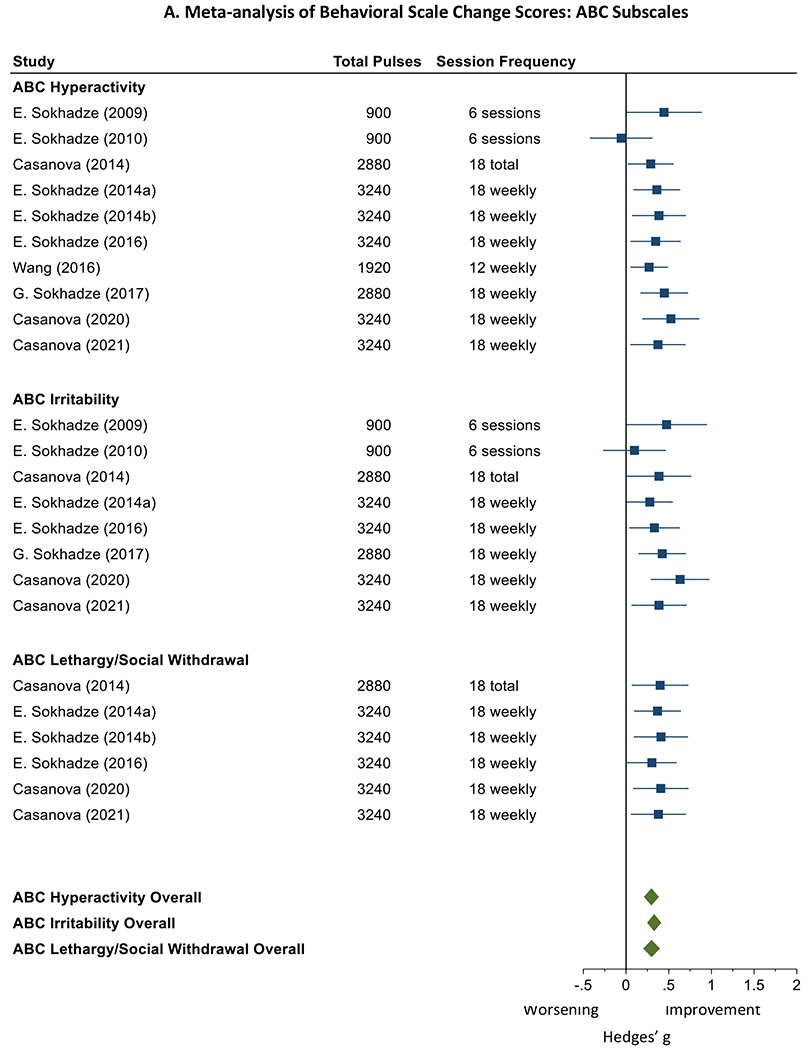

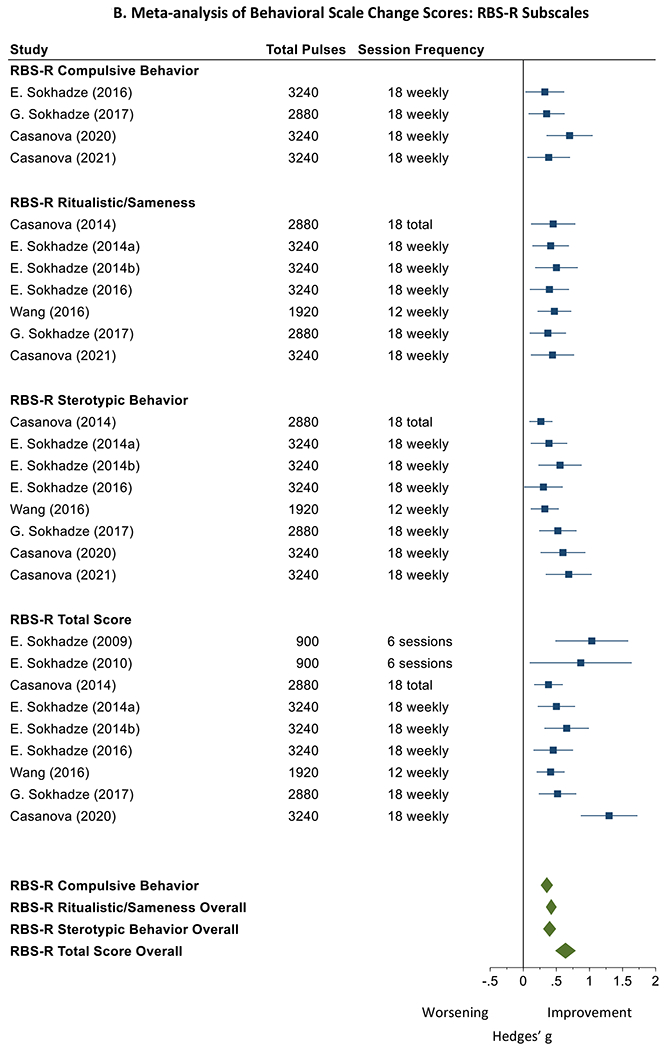

Fifty-two behavioral measures from ten studies were included in the meta-analysis of behavioral outcomes and the results are reported in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Figure 2A, and Figure 2B. The multivariate meta-analysis with robust variance estimation showed an overall significant improvement in behavioral outcomes after treatment with TMS (pooled Hedges’ g=0.435, 95% CI=0.359, 0.511; p<0.001). The Q-test was significant (p<0.001) and the joint I2JWR was 98.92%, indicating high heterogeneity and suggesting the outcomes were not estimating a common Hedges’ g. There was significant evidence of small-study effects as determined by Egger’s test (p<0.001) in Stata and publication bias as determined by selection modeling in JASP (p<0.001). Selection modeling indicated that the pooled effect size after adjusting for publication bias was 0.443 (95% CI: 0.385, 0.500; p<0.001). However, this result should be interpreted with caution because there was no way to account for dependencies among effect sizes.

Table 3.

Detailed results of the multivariate meta-analyses examining behavioral and cognitive outcomes in ASD patients treated with TMS.

| Outcome | Hedges’ g Effect Size | Standard Error | 95% CI | Test Statistic | P-value | I2JWR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Behavioral Measures | ||||||

| ABC Hyperactivity | 0.297 | 0.043 | (0.210, 0.383) | t=6.90 | <0.001 | 3.64% |

| ABC Irritability | 0.329 | 0.042 | (0.245, 0.414) | t=7.85 | <0.001 | 0.00% |

| ABC Lethargy/Social Withdrawal | 0.299 | 0.049 | (0.199, 0.399) | t=6.03 | <0.001 | 5.42% |

| RBS-R Compulsive Behavior | 0.355 | 0.047 | (0.260, 0.450) | t=7.53 | <0.001 | 0.00% |

| RBS-R Ritualistic/Sameness | 0.422 | 0.041 | (0.339, 0.505) | t=10.23 | <0.001 | 0.00% |

| RBS-R Stereotypic Behavior | 0.397 | 0.049 | (0.297, 0.498) | t=7.98 | <0.001 | 37.14% |

| RBS-R Total Score | 0.638 | 0.079 | (0.478, 0.797) | t=8.04 | <0.001 | 69.89% |

| Overall | 0.435 | 0.033 | (0.359, 0.511) | t=7.99 | <0.001 | 98.92% |

| B. Cognitive Measures | ||||||

| Commission Error Rate | 0.759 | 0.221 | (0.261, 1.259) | t=3.44 | 0.007 | 78.37% |

| Total Error Rate | 0.777 | 0.232 | (0.254, 1.301) | t=3.36 | 0.008 | 80.16% |

| Overall | 0.735 | 0.207 | (0.242, 1.228) | t=6.77 | 0.009 | 97.39% |

I2JWR=Jackson-White-Riley multivariate heterogeneity statistic

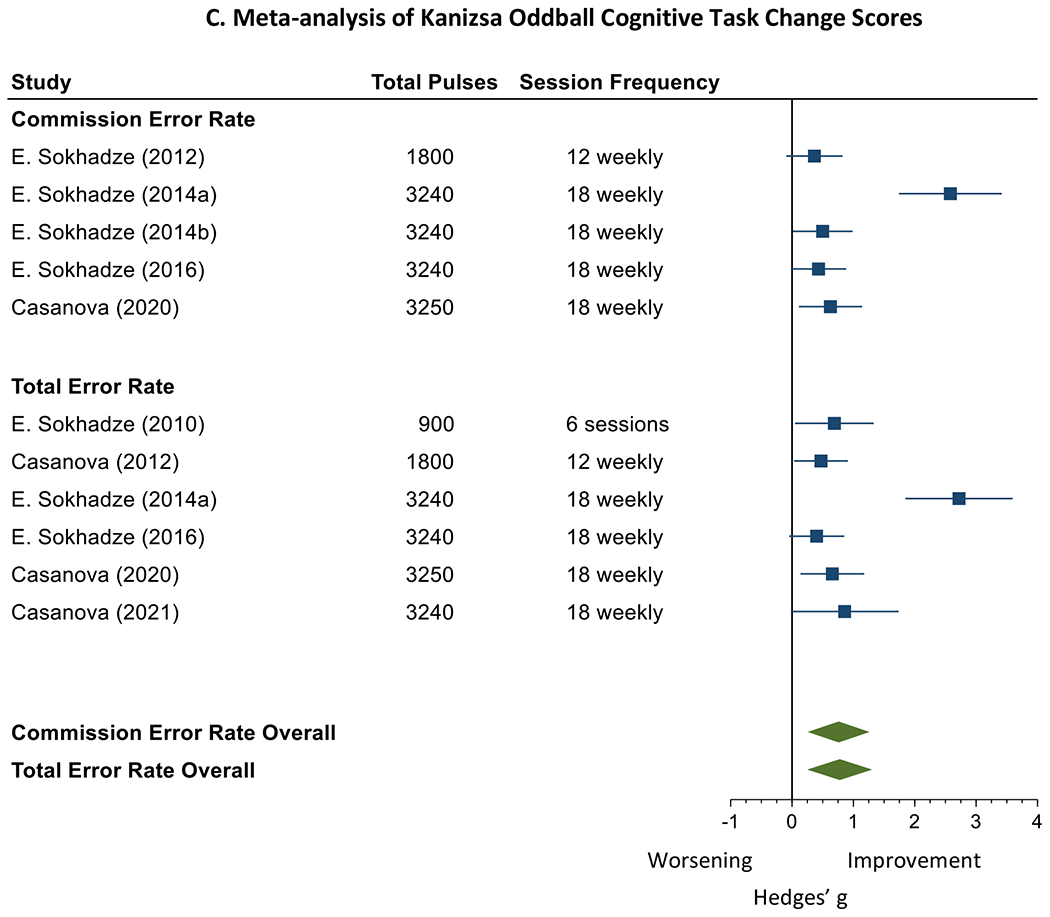

Figure 2.

Meta-analyses of Behavioral Scale and Cognitive Task Change Scores in ASD Patients Administered TMS Treatment

Stratified multivariate analyses by behavioral scale showed similar patterns (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, and Figures 2A & 2B). For all seven scales (ABC Hyperactivity, Irritability, and Lethargy/Social Withdrawal; RBS-R Compulsive Behavior, Ritualistic/Sameness Behavior, Stereotypic Behavior, and Total), the pooled Hedges’ g effect sizes, while small to moderate in size, indicated significant improvement with TMS treatment (all p<0.001) and ranged from 0.297 for ABC Hyperactivity to 0.638 for RBS-R Total. Heterogeneity was low for the all three ABC scales and the RBS-R Compulsive Behavior and Ritualistic/Sameness Behavior with I2JWR statistics ranging from 0.00% to 5.42% (Table 3). Heterogeneity for the remaining two RBS-R scales was considerably higher with I2JWR=37.14% for Stereotypic Behavior and I2JWR=69.89% for Total. Furthermore, when we included total pulses in the model there was a significant association between total pulses and the effect of TMS when looking at the ABC Hyperactivity scale (p=0.02). The effect of TMS on ABC Hyperactivity significantly increased as total pulses increased. There was no association between total pulses and the effect of TMS for any of the other scales.

Cognitive Outcomes:

Eleven cognitive measures from eight studies were included in the meta-analysis of cognitive outcomes and the results are reported in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, and Figure 2C. The multivariate meta-analysis with robust variance estimation showed an overall significant improvement in cognitive outcomes after treatment with TMS (pooled Hedges’ g=0.735, 95% CI=0.242, 1.228; p=0.009). The Q-test was significant (p<0.001) and the joint I2JWR was 97.39%, indicating high heterogeneity and suggesting the outcomes were not estimating a common Hedges’ g. There was significant evidence of small-study effects as determined by Egger’s test in Stata (p<0.001) and publication bias as determined by selection modeling in JASP (p<0.001). Selection modeling indicated that the pooled effect size after adjusting for publication bias was 1.671 (95% CI: 1.334, 2.009; p<0.001). However, this result should be interpreted with caution because there was no way to account for dependencies among effect sizes.

Stratified multivariate analyses by cognitive task showed similar patterns (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, and Figure 2C). The pooled Hedges’ g effect sizes for Commission Error Rate (0.759; p=0.007) and Total Error Rate (0.777; p=0.008) indicated significant improvement with TMS treatment. Heterogeneity was high for both scales with I2JWR=78.37% for Commission Error Rate and I2JWR=80.16% for Total Error Rate. When we included total pulses in the model there was no significant association between total pulses and the effect of TMS for either of the tasks (both p>0.05).

Discussion:

Our review and meta-analysis found some consistencies within current TMS research for the treatment of IC-ASD in this patient population. Regarding TMS parameters, inhibitory TMS dosing was used in 14/16 studies, (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) with studies by Ameis and Ni being the only excitatory TMS treatments.(Ameis et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2021) In recent work on TMS in ASD, LF-rTMS is more often researched compared to HF-rTMS or iTBS based on the neurobiological hypothesis of parvalbumin (PV) deficiency attributed to ASD. (Hashemi et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017; Steullet et al., 2017) PV containing cells are susceptible to oxidative injury and make up the largest subgroup of cortical inhibitory interneurons. Reduced numbers of PV-expressing cells have been reported in human postmortem brain samples (Hashemi et al., 2017) and animal models of ASD. (Lee et al., 2017) Additionally, reduced levels of PV expression are associated with ASD-like behavioral deficits and sensory-motor symptoms associated with ASD. In animal models, long term reversal of PV deficits by pharmacologic or cell type specific gene rescue normalizing or diminishes these symptoms.(Lee et al., 2017; Mukherjee et al., 2019; Selimbeyoglu et al., 2017) Thus, researchers have identified a possible excitatory:inhibitory (E/I) imbalance in IC-ASD, also termed “electrophysiological endophenotype” as a target of intervention in the treatment of ASD. (Rojas & Wilson, 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009; Steullet et al., 2017) The E/I imbalance may represent glutaminergic cortical excitotoxicity, (Rojas, 2014) hyperplasticity due to dysfunction of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor mediated long-term depression and potentiation-like plasticity mechanisms, and/or inhibitory GABAnergic dysfunction; all of which may be modulated by specific TMS protocols and monitored via electroencephalogram (EEG) guided ERP. (Buzsáki & Wang, 2012; Jeste & Nelson, 2009) Abnormal oscillations in high gamma band have been observed in this patient population, as well as changes in TMS derived biomarkers of cortical inhibition in response to the inhibitory cTBS; (Casanova et al., 2020, 2021; Jannati et al., 2020; Kirkovski et al., 2022; Oberman et al., 2016; Oberman, Rotenberg, et al., 2014) adding further evidence of an abnormal E/I balance in IC-ASD which may be modified by inhibitory TMS protocols. (Buzsáki & Wang, 2012; Casanova et al., 2020; Jeste & Nelson, 2009) Encouragingly, multiple studies have reported normalization of gamma wave activity with use of LF-rTMS in IC-ASD persons. (Brown et al., 2005; Casanova et al., 2020; Floris et al., 2016; Rippon et al., 2007; Snijders et al., 2013; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2016)

Regarding the two studies with excitatory TMS dosing, Ameis and colleagues utilized 20 Hz HF-rTMS in an effort to improve EF in IC-ASD individuals. (Ameis et al., 2020) Their rationale was driven by previous rTMS research in schizophrenia which used similar rTMS parameters and demonstrated improvements in cognitive and functional impairments in schizophrenia comparable to those observed in IC-ASD. (Maxwell et al., 2015) While improvements across the entire group were negligible in their study, individuals with significant adaptive functional impairment demonstrated robust EF improvements compared to sham. (Ameis et al., 2020) This is of clinical interest given that, based on the excitotoxic PV hypothesis of ASD, it may be assumed that HF-rTMS would have minimal clinical effect. However, these findings by Ameis and colleagues suggest that phenotypic expression of low adaptive functioning abilities in IC-ASD may be an indicator of clinical response in the realm of EF to HF-rTMS compared to IC-ASD individuals with higher adaptative functioning. Furthermore, guided by previous neuroimaging research demonstrating pSTS hypofunction in ASD, (Yang et al., 2015) Ni and colleagues utilized the iTBS protocol in their work. They found that significant clinical response was more likely for individuals with baseline higher intellectual functioning, better social cognitive performance, and less attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptomology, and when treatment occurred over the course of 8 weeks rather than 4 weeks. (Ni et al., 2021) The direct correlation between time in treatment and clinical response was observed by Sokhadze in 2018 as well. (E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2018) Thus, future research is warranted regarding greater clarification and identification of possible ASD subtypes, their neurobiologic underpinnings, outcome measures specific to a site of TMS modulation, (Cole et al., 2019) as well as the possible correlation between clinical response and time in TMS treatment.

TMS coil placement technique was investigated as well. 14/16 studies targeted the DLPFC (Ameis et al., 2020; Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) with 13/14 using the traditional “5 cm rule” of coil placement at 5 cm anterior, and in the parasagittal plane, to the site of FDI maximal stimulation. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) Current TMS literature suggests that when the “5 cm rule” is used, the DLPFC is not accurately targeted in 33% (George, 2010) to 68% of individuals, (Herwig et al., 2001) leading

In our review, Ameis and Ni conducted the only two studies to incorporate use MRI guided TMS targeting. (Ameis et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2021) In light of this information and regular use neuronavigation in other TMS research areas, (Cole et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020) consideration of either MRI guided or Beam F3 targeting in future research is warranted.

The results of our meta-analysis were divided into two sections, behavioral and cognitive. In the behavioral realm, the ABC and RBS-R results were indicative of mild to moderate clinical improvements. Cognitively, the Kanizsa oddball task was used most often. (Kanizsa, 1976) The results of our meta-analysis indicate large and significant improvements in rates of total errors and commission errors with LF-rTMS treatment. However, our study was limited quantitatively as we were able to retrieve only published and statistically significant data which primarily characterized criterion B symptoms of ASD. Additionally, only 12/16 studies were able to be included in the meta-analysis due to availability of data, TMS protocols, and target of treatment. However, reported improvements in RRB via this treatment modality is encouraging in light of the fewer pharmacological options in treatment of criterion B symptoms. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Zhou et al., 2021)

Limitations:

Our study has several limitations. In controlled studies, blinding was done inconsistently, randomization did not occur in 2/9 studies due to feasibility concerns, (E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009) and waitlist controls were often utilized over sham TMS. Waitlist controls demonstrate IC-ASD symptom stability over time rather than fully investigating for a placebo response as would be observed with sham controls. 4/16 (E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2010, 2016; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) studies had no control group and 3/16 incorporated NT individuals as controls only for baseline data. (Casanova et al., 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2016) Thus, only 2/16 studies in our systematic review were randomized control trials, (Ameis et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2021) and all studies included in the meta-analysis were open label in design. This is of significant importance in pediatric TMS research design as recent literature reports a lack of separation from sham TMS when investigating the use of TMS in the treatment of adolescent refractory MDD. (Croarkin et al., 2021) In our review, Ameis and colleagues conducted the only double blinded, sham controlled, and parallel study; a design urgently needed in future research. (Ameis et al., 2020) We were also limited in our investigation into the core social features of IC-ASD. The RBS-R well characterizes a wide breath of Criterion B symptomology (Lam & Aman, 2007) and was measured in all reviewed behavioral studies. Significant improvements in the ABC subscales of hyperactivity and irritability were also frequently reported, though are likely influenced primarily by Criterion B symptomology. In contrast, improvements in socially mediated symptoms were not as well characterized. Significant improvements in the ABC subdomain of lethargy/social withdrawal were reported in 5/13 behavioral studies. (Casanova et al., 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017) The SRS-2 well characterizes social symptom burden, (Constantino & Gruber, 2012) but was only used in 6/16 behavioral studies (Casanova et al., 2012; Ni et al., 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017) and results were reported in 4/6. (Casanova et al., 2012; Ni et al., 2021; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2010; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017) Moreover, 2/4 found no statistically significant improvement in SRS-2 scores. (Casanova et al., 2012; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009) Additionally, because we relied on data reported by authors, we were restricted by what investigators chose to present. There are also very few studies with small sample sizes that could lead to inflated estimates of effect sizes due to a publication bias which favors the publication of positive over negative studies. While attempts were made to adjust for publication bias using selection models, the results need to be interpreted with caution given there was not a way to correct for dependencies among effect sizes. Likewise, the small number of studies and lack of control for dependencies among effect sizes also limits the confidence we can place on Egger’s test for small-study effects.

Other limitations include a lack of reporting on patient sociodemographic factors, an absence of multi-center trials, limited involvement of other research groups as M. F. Casanova or E.M. Sokhadze were authors on 13/16 studies. (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) Moreover, as observed in other areas of IC-ASD research, biologically female IC-ASD patients were underrepresented. (Mo et al., 2021) In studies investigated, the ratio of male to female was nearly 4.5:1 rather than 3:1 as reported in recent literature. (Loomes et al., 2017) In addition, while the average age of the study by Ameis and colleagues was 22, their maximum age was 35; serving as an outlier in our systematic review. (Ameis et al., 2020) Lastly, results from behavioral measures may be limited by informant- vs self-reporting. Close family members are often used as informants. However, many family members of individuals with ASD carry the diagnosis or demonstrate autistic traits without meeting criteria of the disorder (Rubenstein et al., 2019) and often under report symptoms in others which they experience. (De la Marche et al., 2015) Additionally, due to interpersonal and social deficits observed in ASD, self-appraisal of social/emotional symptoms can be uniquely challenging. (Rankin et al., 2016)

Conclusions:

Overall, the results of our review and meta-analysis indicate that TMS and TBS may be a safe therapeutic option for pediatric and young adult individuals with IC-ASD. Additionally, that RRBs as well as cognitive and EF deficits may be therapeutically targeted via TMS pulses to the DLPFC. Notably, the study by Ni and colleagues shows promise for improvement in social symptoms via targeted TBS pulses to the pSTS. (Ni et al., 2021) However, the results of our study are limited by a lack of randomized sham-controlled trials, an inability to include randomized control trials in our meta-analysis, likely TMS pulse underdosing, inconsistent use of neuronavigation, and under-representation of biologically female individuals. Regardless, given current limitations and side effect profiles associated with psychopharmacologic treatment of ASD, (Alfageh et al., 2019; Hutton, 2008; J. R. Smith & Pierce, 2022; Zhou et al., 2021) continued research into TMS as a therapeutic option in IC-ASD is warranted. Moreover, it is possible that future research investigating modulation of other neural networks and cortical regions may result in improvement to other IC-ASD symptom domains. (Guo et al., 2019; Joshi et al., 2019; Williams, 2016) Specifically, attempts to target the default mode, salience, and affective networks may be of benefit as they are commonly associated with complex cognitive and emotional tasks which may be challenging for individuals with ASD. (Lavin et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2020; R. Smith et al., 2019; Williams, 2016) Given the high prevalence of suicidality, mood and anxiety disorders in autistic youth, future research should also consider targeting these co-morbidities via TMS. (Hollocks et al., 2019; O’Halloran et al., 2022; Schwartzman et al., 2021) Lastly, relative to current TMS research on other neuropsychiatric conditions, the number of TMS pulses administered in 14/16 IC-ASD TMS studies were significantly lower; (Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) raising concern for underdosing. (Carmi et al., 2019; Cole et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020)

Regarding use of specific TMS modalities, 15/16 studies in our review utilized rTMS. (Ameis et al., 2020; Casanova et al., 2012, 2014, 2020, 2021; Enticott, 2012; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Sears, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze, El-Baz, Tasman, et al., 2014; E. M. Sokhadze et al., 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018; G. E. Sokhadze et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016) However, given the promising work from Ni and colleagues (Ni et al., 2021) and that TBS has been safely used in similar patient populations, (Elmaghraby et al., 2021) can be rapidly administered in accelerated protocols, has been researched as a diagnostic tool to detect IC-ASD in pediatric patients, (Cole et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2005; Jannati et al., 2020; Pedapati et al., 2016) use of TBS should be strongly considered in future work. Moreover, given the absence of seizure activity uncovered in our review and very low frequency reported in others, (Elmaghraby et al., 2021) further research into TBS and dTMS as a therapeutic option in IC-ASD is warranted. (Cole et al., 2020) Although, known ethical considerations must be taken into account. (Davis, 2014; Maslen et al., 2014)

In summary, the field of IC-ASD TMS research would undoubtably benefit from greater use of neuronavigation software, (Herwig et al., 2001; Nauczyciel et al., 2011) robust study design, (Croarkin et al., 2021) gender matching, use of agreed upon and consistent TMS protocols, as well as increased reporting of sociodemographic factors. Additionally, incorporation, focus, and reporting on outcomes measures related to criterion A of IC-ASD as well as adaptive functioning is needed to obtain a greater understanding of phenotypic expression of IC-ASD and response to treatment. Based on our review, meta-analysis, and previous meta-analysis work, (Barahona-Correa, 2018) further investigation into the use of TMS targeting various networks and cortical regions for the treatment of ASD related social impairments and RRBs, cognitive deficits, common psychopathologic co-morbidities, and executive functioning deficits is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work is funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers T32HD007475 in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, K23MH100450, and the Alan and Lorraine Bressler Clinical and Research Program for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dr. Joshi is specifically supported by the NIMH of the NIH under Award Number K23MH100450. Dr. Anteraper receives grant support from NIMH of the NIH under award number 1R03MH121879-01A1. Dr. Croarkin receives funding from the NIH under grants R01 MH113700 and R01 MH124655. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIMH or the NIH.

Competing Interests:

JRS is employed by Vanderbilt University Medical Center as a child and adolescent psychiatrist with no other financial relationships to disclose. AG and MD do not have financial relationships to disclose. AC reports personal fees from Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, non-financial support from NIH, personal fees from Pamlab, Inc., personal fees from US Department of Defense, non-financial support from Neurocentria, Inc., personal fees from Food and Drug Administration, non-financial support from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., non-financial support from Roche TCRC, Inc. SA is employed by the Carle Foundation Hospital in Urbana, Illinois with no other financial relationships to disclose. PC has received research support from Pfizer, Inc. and equipment support from Neuronetics, Inc. and MagVenture, Inc. He has received grant in kind support from AssureRX for supplies and genotyping. He has been the primary investigator for a multicenter study funded by Neuronetics, Inc. and a site primary investigator for a study funded by NeoSync, Inc. He has served as a paid consultant for Engrail Therapeutics, Myriad Neuroscience, Procter and Gamble Company, and Sunovion. In the last year, GJ has received research support from the Demarest Lloyd, Jr. Foundation as a primary investigator (PI) for investigator-initiated studies. Additionally, GJ receives research support F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. as a site PI for multi-site trials. In the past three years, GJ has received research support from Pfizer and the Simons Center for the Social Brain. In addition, GJ has received honorarium from the Governor’s Council for Medical Research and Treatment of Autism in New Jersey and from NIMH for grant review activities. Finally, he received speaker’s honorariums from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, The Israeli Society of ADHD, the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the University of Jülich.

Abbreviations:

- rTMS

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- HF-rTMS

high frequency rTMS

- LtDLPFC

left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- TMS

transcranial magnetic stimulation

- LF-rTMS

low frequency rTMS

- RtDLPFC

right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- TBS

theta burst stimulation

- cTBS

continuous theta burst stimulation

- iTBS

inhibitory theta burst stimulation

- dTMS

deep TMS

- OCD

obsessive compulsive disorder

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- ACC

anterior cingulate cortex

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- RRB

restricted/repetitive behaviors

- EF

executive functioning

- IC-ASD

autism spectrum disorder in intellectually capable persons

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SMD

standardized mean differences

- REML

restricted maximum likelihood

- I2JWR

Jackson-White-Riley I2 index

- NT

neurotypical

- ADI-R

autism diagnostic interview-revised

- ADOS

autism diagnostic observation schedule

- SCL

skin conductance level

- HRV

heart rate variability

- BiDLPFC

bilateral DLPFC

- M1

primary motor cortex

- SMA

supplemental motor area

- pSTS

posterior superior temporal sulcus

- FDI

first dorsal interossei muscle

- SRS-2

social responsiveness scale

- RBS-R

repetitive behavioral scale-revised

- ABC

aberrant behavioral checklist

- ERP

event related potentials

- BRIEF

Behavioral Rating Inventory for Executive Function

- SR

Self-Report

- VABS-II

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale–II

- MRCP

movement-related cortical potentials

- PV

parvalbumin

- E/I

excitation-to-inhibition

- EEG

electroencephalogram

Footnotes

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

Not applicable

Consent for publication:

All authors provide consent for publication.

Availability of data and materials:

Data regarding systematic review is attached to the submission. Further meta-analytic data than presented in this manuscript is available upon request.

References:

- Alfageh BH, Wang Z, Mongkhon P, Besag FMC, Alhawassi TM, Brauer R, & Wong ICK (2019). Safety and Tolerability of Antipsychotic Medication in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatric Drugs, 21(3), 153–167. 10.1007/s40272-019-00333-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CH, Kluger BM, & Buard I (2017). Safety of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Children: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pediatric Neurology, 68, 3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, & Field CJ (1985). The aberrant behavior checklist: A behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 89(5), 485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameis SH, Blumberger DM, Croarkin PE, Mabbott DJ, Lai M-C, Desarkar P, Szatmari P, & Daskalakis ZJ (2020). Treatment of Executive Function Deficits in autism spectrum disorder with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: A double-blind, sham-controlled, pilot trial. Brain Stimulation, 13(3), 539–547. 10.1016/j.brs.2020.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing Arlington. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barahona-Correa JB (2018). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Integr Neurosci, 12, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JE, Smith JR, & Hazen EP (2020). Pediatric Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry: An Update and Review. Psychosomatics, 61(5), 467–480. 10.1016/j.psym.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlim MT, Van den Eynde F, Tovar-Perdomo S, Chachamovich E, Zangen A, & Turecki G (2014). Augmenting antidepressants with deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (DTMS) in treatment-resistant major depression. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry: The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, 15(7), 570–578. 10.3109/15622975.2014.925141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomstedt P, Sjöberg RL, Hansson M, Bodlund O, & Hariz MI (2013). Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. World Neurosurgery, 80(6), e245–e253. 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M (2009). Effect Sizes for Continuous Data. In Cooper H, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (Eds.), The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis (2nd ed.). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Gruber T, Boucher J, Rippon G, & Brock J (2005). Gamma abnormalities during perception of illusory figures in autism. Cortex; a Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 41(3), 364–376. 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70273-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, & Wang X-J (2012). Mechanisms of Gamma Oscillations. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35(1), 203–225. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANTAB Cognitive Research Software. (n.d.). Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://www.cambridgecognition.com/cantab/

- Carmi L, Alyagon U, Barnea-Ygael N, Zohar J, Dar R, & Zangen A (2018). Clinical and electrophysiological outcomes of deep TMS over the medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices in OCD patients. Brain Stimulation, 11(1), 158–165. 10.1016/j.brs.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmi L, Tendler A, Bystritsky A, Hollander E, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis J, Ward H, Lapidus K, Goodman W, Casuto L, Feifel D, Barnea-Ygael N, Roth Y, Zangen A, & Zohar J (2019). Efficacy and Safety of Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 176(11), 931–938. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova MF, Baruth JM, El-Baz AS, Tasman A, Sears LL, & Sokhadze EM (2012). Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) Modulates Event-Related Potential (ERP) Indices of Attention in Autism. Translational Neuroscience, 3(2), 170–180. 10.2478/s13380-012-0022-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova MF, Hensley MK, Sokhadze EM, El-Baz AS, Wang Y, Li X, & Sears LL (2014). Effects of weekly low-frequency rTMS on autonomic measures in children with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 851. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova MF, Shaban M, Ghazal M, El-Baz AS, Casanova EL, Opris I, & Sokhadze EM (2020). Effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapy on Evoked and Induced Gamma Oscillations in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences, 10(7), 423. 10.3390/brainsci10070423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova MF, Shaban M, Ghazal M, El-Baz AS, Casanova EL, & Sokhadze EM (2021). Ringing Decay of Gamma Oscillations and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapy in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46(2), 161–173. 10.1007/s10484-021-09509-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SW, Hoy KE, & Fitzgerald PB (2015). Theta-burst stimulation: A new form of TMS treatment for depression? Depression and Anxiety, 32(3), 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole EJ, Enticott PG, Oberman LM, Gwynette MF, Casanova MF, Jackson SLJ, Jannati A, McPartland JC, Naples AJ, & Puts NAJ (2019). The Potential of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Consensus Statement. Biological Psychiatry, 85(4), e21–e22. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, Gulser M, Cherian K, Tischler C, Nejad R, Pankow H, Choi E, Aaron H, Espil FM, Pannu J, Xiao X, Duvio D, Solvason HB, Hawkins J, Guerra A, Jo B, Raj KS, … Williams NR (2020). Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(8), 716–726. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19070720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly KR (2012). Effectiveness of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice post-FDA approval in the United States: Results observed with the first 100 consecutive cases of depression at an academic medical center. J Clin Psychiatry, 73(4), 567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, & Gruber CP (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-2): Manual (2nd ed.). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Croarkin PE, Elmaadawi AZ, Aaronson ST, Schrodt GR, Holbert RC, Verdoliva S, Heart KL, Demitrack MA, & Strawn JR (2021). Left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression in adolescents: A double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 46(2), 462–469. 10.1038/s41386-020-00829-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damji O, Roe J, Shinde S, Kotsovsky O, & Kirton A (2013). Effects of paired associative stimulation on developmental motor plasticity in children. Clinical Neurophysiology, 124(10), e147–e148. 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.04.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NJ (2014). Transcranial stimulation of the developing brain: A plea for extreme caution. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 600. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Marche W, Noens I, Kuppens S, Spilt JL, Boets B, & Steyaert J (2015). Measuring quantitative autism traits in families: Informant effect or intergenerational transmission? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(4), 385–395. 10.1007/s00787-014-0586-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmaghraby R, Sun Q, Ozger C, Shekunov J, Romanowicz M, & Croarkin PE (2021). A Systematic Review of the Safety and Tolerability of Theta Burst Stimulation in Children and Adolescents. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, ner.13455. 10.1111/ner.13455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enticott PG (2012). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves movement-related cortical potentials in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Stimul, 5(1), 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floris DL, Barber AD, Nebel MB, Martinelli M, Lai M-C, Crocetti D, Baron-Cohen S, Suckling J, Pekar JJ, & Mostofsky SH (2016). Atypical lateralization of motor circuit functional connectivity in children with autism is associated with motor deficits. Molecular Autism, 7, 35. 10.1186/s13229-016-0096-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MS (1995). Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. Neuroreport: An International Journal for the Rapid Communication of Research in Neuroscience. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MS (2010). Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: A sham-controlled randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(5), 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Chen J, Chen Q, Ren K, Feng D, Mao H, Yao H, Yang J, Liu H, Liu Y, Jia F, Qi C, Lynn-Jones T, Hu H, Fu Z, Feng G, Wang W, & Wu S (2019). Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction underlies social deficits in Shank3 mutant mice. Nature Neuroscience, 22(8), 1223–1234. 10.1038/s41593-019-0445-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi E, Ariza J, Rogers H, Noctor SC, & Martínez-Cerdeño V (2017). The Number of Parvalbumin-Expressing Interneurons Is Decreased in the Prefrontal Cortex in Autism. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991), 27(3), 1931–1943. 10.1093/cercor/bhw021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Tipton E, & Johnson MC (2010). Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(1), 39–65. 10.1002/jrsm.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig U, Padberg F, Unger J, Spitzer M, & Schönfeldt-Lecuona C (2001). Transcranial magnetic stimulation in therapy studies: Examination of the reliability of “standard” coil positioning by neuronavigation. Biological Psychiatry, 50(1), 58–61. 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01153-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollocks MJ, Lerh JW, Magiati I, Meiser-Stedman R, & Brugha TS (2019). Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 559–572. 10.1017/S0033291718002283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, & Rutter M (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 45(2), 212–229. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, MJ E, E R, KP B, & JC R (2005). Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron, 45, 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton J (2008). New-onset psychiatric disorders in individuals with autism. Autism, 12(4), 373–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S, & Greenhouse JB (1988). Selection Models and the File Drawer Problem. Statistical Science, 3(1), 109–117. 10.1214/ss/1177013012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, & Riley RD (2014). A refined method for multivariate meta-analysis and meta-regression. Statistics in Medicine, 33(4), 541–554. 10.1002/sim.5957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, White IR, & Riley RD (2012). Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Statistics in Medicine, 31(29), 3805–3820. 10.1002/sim.5453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannati A, Block G, Ryan MA, Kaye HL, Kayarian FB, Bashir S, Oberman LM, Pascual-Leone A, & Rotenberg A (2020). Continuous Theta-Burst Stimulation in Children With High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typically Developing Children. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 14, 13. 10.3389/fnint.2020.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannati A, Ryan MA, Kaye HL, Tsuboyama M, & Rotenberg A (2021). Biomarkers Obtained by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, Publish Ahead of Print. 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JASP Team. (n.d.). JASP (0.16.3) [Computer software].

- Jeste SS, & Nelson CA (2009). Event Related Potentials in the Understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorders: An Analytical Review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(3), 495. 10.1007/s10803-008-0652-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Gönenç A, Lukas S, Wozniak J, Dallenbach N, Hoskova B, Castle R, & Biederman J (2019). Anterior Cingulate Cortex Glutamate Activity in Autism Spectrum Disorder with and without Emotional Dysregulation (S19.008). Neurology, 92(15 Supplement). https://n.neurology.org/content/92/15_Supplement/S19.008 [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Petty C, Wozniak J, Henin A, Fried R, Galdo M, Kotarski M, Walls S, & Biederman J (2010). The Heavy Burden of Psychiatric Comorbidity in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Large Comparative Study of a Psychiatrically Referred Population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(11), 1361–1370. 10.1007/s10803-010-0996-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanizsa G (1976). Subjective contours. Scientific American, 234(4), 48–52. 10.1038/scientificamerican0476-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghi A, Zarafshan H, Vand SR, & Mohammadi MR (2020). Effects of Non-invasive Neurostimulation on Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 18(4), 527–552. 10.9758/cpn.2020.18.4.527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkovski M, Hill AT, Rogasch NC, Saeki T, Fitzgibbon BM, Yang J, Do M, Donaldson PH, Albein-Urios N, Fitzgerald PB, & Enticott PG (2022). A single- and paired-pulse TMS-EEG investigation of the N100 and long interval cortical inhibition in autism spectrum disorder. Brain Stimulation, 15(1), 229–232. 10.1016/j.brs.2021.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]