Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is prevalent among sexual minority women (SMW). However, compared to IPV research with heterosexual women and other LGBTQ+ population groups, SMW are understudied. We conducted a scoping review to examine the current state of knowledge about IPV among SMW, and to identify gaps and directions for future research. A search of Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases returned 1,807 papers published between January 2000 and December 2021. After independent reviewers screened these papers for relevance, 99 were included in the final review. Papers were included if they used quantitative methods and reported IPV data on adult SMW separately from other groups. Findings confirmed high rates of IPV among SMW and highlighted groups with particular vulnerabilities, including non-monosexual women and SMW of color. Risk factors for IPV in this population include prior trauma and victimization, psychological and emotional concerns, substance use, and minority stressors. Outcomes include poor mental and physical health. Findings related to the effects of minority stressors on IPV and comparisons across sexual minority groups were inconsistent. Future research should focus on IPV perpetration; mechanisms underlying risk for IPV, including structural-level risk factors; and understanding differences among SMW subgroups.

Introduction

Rates of intimate partner violence (IPV; physical, sexual, or psychological violence or aggression by a current or former intimate partner) among sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual, queer; women who engage in same-sex sexual behaviors; women who have same-sex attractions) are similar to or greater than those among heterosexual women (Edwards et al., 2015; Kim & Schmuhl, 2019; Walters et al., 2013). Most research on IPV focuses on heterosexual women as victims of IPV; a much smaller body of research focuses on SMW’s IPV experiences. Generally, risk factors among sexual minorities appear to be similar to those of heterosexual individuals, such as alcohol misuse (Klostermann, Kelley, Milletich, & Mignone, 2011), power imbalance, dependency, and jealousy (McClennen, 2009). However, SMW’s risk of IPV is also likely affected by sexual minority-specific factors such as stigma, discrimination, internalized homophobia (IH), and concealment of sexual identities (Edwards et al., 2015; Longobardi & Badenes-Ribera, 2017; Rohrbaugh, 2006), and may vary by subpopulation.

A report from the 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) noted important within-group differences in rates of IPV among SMW, with higher rates of victimization among bisexual women (Walters et al., 2013). Lifetime violence victimization rates among bisexual women ranged from 40% for sexual violence, 55% for physical violence, and 76% for psychological violence (Walters et al., 2013). Recent reviews parsing different types of IPV among lesbian women have also found psychological violence victimization to be the most prevalent type (Badenes-Ribera, Bonilla-Campos, Frias-Navarro, Pons-Salvador, & Monterde, 2016), with a 2015 meta-analysis estimating a 43% lifetime prevalence (Badenes-Ribera, Frias-Navarro, Bonilla-Campos, Pons-Salvador, & Monterde-i-Bort, 2015). Physical and sexual IPV victimization were less common, with lifetime estimates of 18% and 14%, respectively (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2015).

However, methodological limitations in this emerging area of research make it difficult to draw solid conclusions about IPV among SMW (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2016; Badenes-Ribera et al., 2015; Lewis, Milletich, Kelley, & Woody, 2012; Mason et al., 2014; Murray & Mobley, 2009). A common limitation is the infrequent use of probability samples or representative sampling procedures (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2016; Badenes-Ribera et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 2012; Murray & Mobley, 2009). For example, a systematic review of IPV studies conducted among self-identified lesbian women from 1990–2012, found that all included studies used nonprobability samples and that the majority of participants were white and highly educated (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2016). An additional limitation is the wide range of IPV measures used, many of which have not been validated (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2015; Mason et al., 2014). Other important limitations in research on IPV among SMW include inconsistent definitions of sexual minority status, with some researchers combining sexual identity and sexual behavior components of sexual orientation, and others aggregating all SMW, regardless of identity (Bermea, van Eeden-Moorefield, & Khaw, 2018), or combining SMW and sexual minority men (SMM) in analyses. As a result, we know relatively little about some subgroups of SMW, such as bisexual women and women who have sex with women but may not identify as sexual minority (Bermea et al., 2018; Kim & Schmuhl, 2019).

Study Purpose

No prior reviews on IPV have included a broad range of SMW subgroups. Existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses either focus on sexual minority populations as a whole (Kim & Schmuhl, 2019; Kimmes et al., 2019), or specific subgroups of SMW, such as those who identify as lesbian (Badenes-Ribera et al., 2016; Badenes-Ribera et al., 2015), or bisexual (Bermea et al., 2018). The purpose of this scoping review is to (1) describe the state of knowledge of both IPV victimization and perpetration among SMW using a broad definition of sexual minority status, (2) identify gaps in the research, and (3) help inform targeted prevention strategies. Our review includes studies that reported data on women who identified as lesbian, bisexual, queer, or another sexual minority identity; women who have sex with women (WSW), or women who have sex with both women and men (WSWM); and/or women who report same-sex attraction.

Methods

We used scoping review methodology (Peters et al., 2021) to summarize current research on IPV perpetration and victimization among SMW. A scoping review is a type of systematic review that seeks to present the state of knowledge of a topic, rather than answer a specific question (Chang, 2018; Tricco et al., 2018). A scoping review may serve a number of functions, including summarizing existing research, clarifying definitions, revealing key concepts, and identifying knowledge gaps and directions for future research (Peters et al., 2021). Rather than focus on a narrower research question, we sought to synthesize what is known regarding the topic of IPV among SMW, with a major aim of guiding future and more targeted research in this area. We adhered to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2021), pre-registered our protocol on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/), and reported our results in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018).

Inclusion Criteria

We included quantitative or mixed methods studies that were published in peer-reviewed journals between January 2000 and December 2021. We selected studies that reported IPV-related data for adult SMW (ages 18 and older, cisgender or transgender). To be included, studies needed to report data for SMW separately from other groups. Studies that used only qualitative methods and those published in a language other than English were excluded.

Search Strategy

Working with a library informationist we systematically searched four databases to identify relevant studies published between 2000 and 2021: (1) Medline (PubMed); (2) Embase; (3) CINAHL and (4) PsycINFO (Ovid). The year 2000 was selected as a start date for the review because it was one year after the 1999 landmark Institute of Medicine report calling for expanded research on lesbian health (Solarz, 1999). Search terms, developed in collaboration with all authors, are included in Appendix A. In addition to the electronic search, we ensured literature saturation by reviewing the reference lists of each included article for additional studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Data Extraction

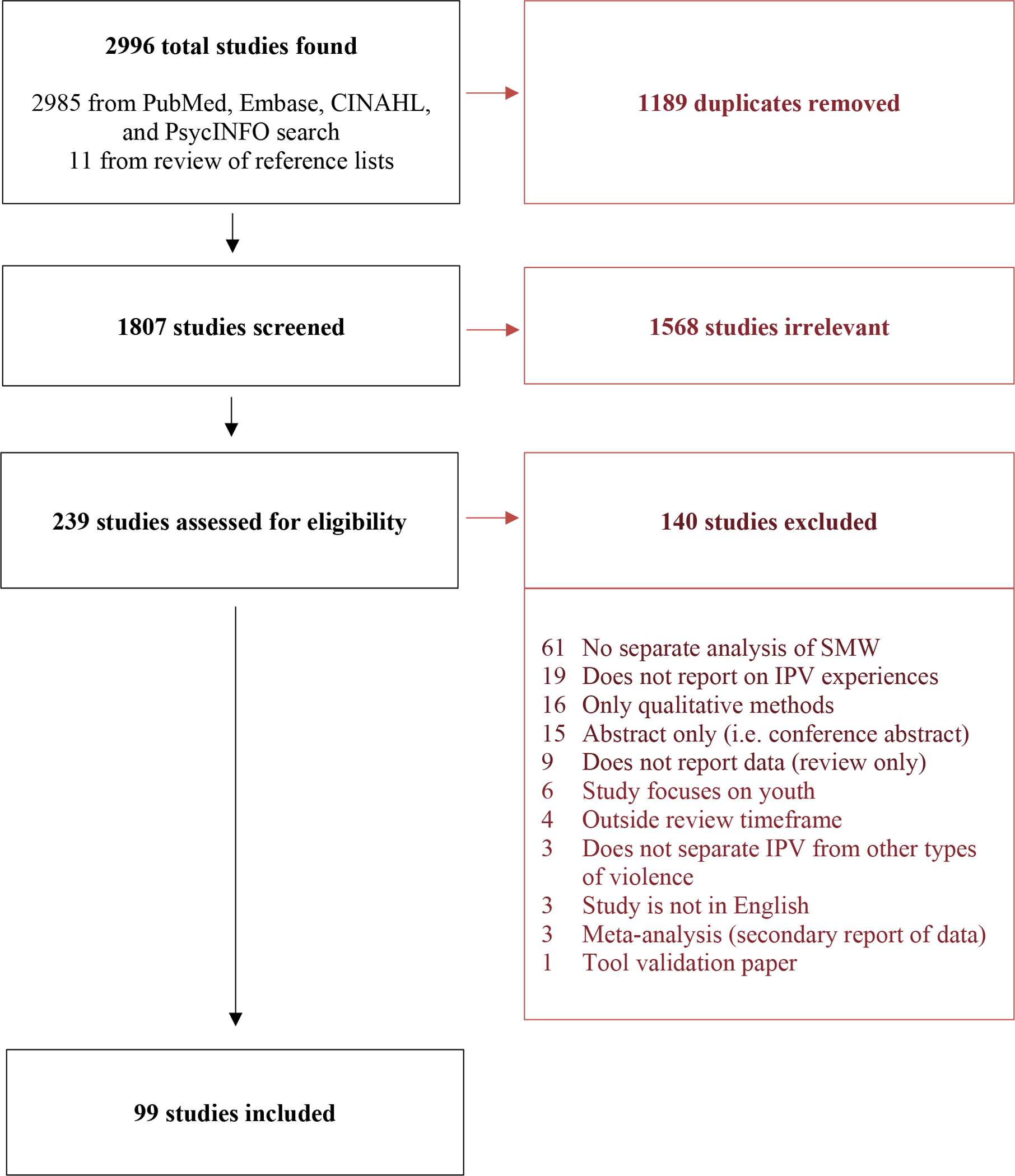

We used Covidence, a web-based software that facilitates the review process in systematic and scoping reviews, to conduct title and abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction. Two independent reviewers completed the title and abstract screening, and met to reconcile any discrepancies. A total of 99 articles were included (see Figure 1). Data on study design and parameters, sample characteristics (including size, geographic location, and key demographic variables), sampling and recruitment methods, and major variables and outcomes were then extracted by five of the authors (see Table 1). Two of the authors independently reviewed the extraction table for accuracy and consistency.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Table of papers reviewed with key study characteristics.

| Study | Study design and data source | Sample | Sampling and recruitment methods | IPV types and measures | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ackerman & Field (2011). The gender asymmetric effect of intimate partner violence on relationship satisfaction. | Cross-sectional secondary data analysis (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health); computer assisted self-administered survey | N = 12,549; U.S. (national); 2.57% women in same sex relationship | Probability sampling; recruited from representative schools in 7th-12th grade | Physical; victimization; 2 items from CTS | Outcome: relationship satisfaction; Independent variables: physical IPV victimization, injury |

| Alexander et al. (2016). Reproductive coercion, sexual risk behaviours and mental health symptoms among young low-income behaviourally bisexual women... | Cross-sectional secondary data analysis (Young Women’s Healthy Relationship Study); self-administered computer survey | N = 129; location not specified; 28% WSWM, 72% WSM | Convenience sampling of clients from six community-based organizations | Sexual (reproductive coercion), physical; victimization; 10 item measure by Miller et al., 2011 | Outcomes: reproductive coercion, physical/sexual violence, sexual risk, PTSD, depression; Independent variable: sexual orientation (behavior) |

| Ayhan Balik & Bilgin (2021). Experiences of minority stress and intimate partner violence among homosexual women in Turkey. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered survey | N = 149; Turkey; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling from Turkish LGBT organizations | Psychological, physical, sexual; perpetration, victimization; Turkish CTS-2 | Outcomes: IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variables: minority stress indicators |

| Baker et al. (2002). Testosterone, alcohol, and civil and rough conflict resolution strategies in lesbian couples. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-report questionnaire and saliva sample | N = 54; location not specified; 100% lesbian | Convenience sampling at a gay pride celebration | Psychological, physical, sexual; perpetration; CTS | Outcomes: civil and rough conflict resolution strategies; Independent variables: testosterone, alcohol consumption |

| Balsam et al. (2005). Victimization over the life span: a comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered mail survey | N = 1,274; U.S.; 10% bisexual women, 27% lesbian women | Convenience sampling using advertisements to LGB organizations | Psychological, physical, sexual; victimization; PMWI-SF, physical subscales of CTS-2 | Outcomes: IPV victimization, childhood psychological, physical, and sexual abuse, adult sexual assault; Independent variables: Sexual identity |

| Balsam & Szymanski (2005). Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online and paper survey | N = 272; U.S. and Canada; 77% lesbian/gay, 18% bisexual, 0.4% heterosexual, 4% other | Convenience sampling from pride events in Vermont and Georgia and SMW listservs | Psychological, physical, sexual; perpetration, victimization; modified CTS-2 and 4 additional investigator-developed questions | Outcomes: Recent and lifetime IPV victimization and perpetration; Independent variables: outness, internalized homophobia, discrimination, sexual identity, butch/femme identity; Mediators: relationship quality |

| Barrett & St. Pierre (2013). Intimate partner violence reported by lesbian-, gay-, and bisexual-identified individuals living in Canada... | Cross-sectional secondary data analysis (General Social Survey of Canada); phone interviews using CATI | N = 372; Canada; 100% lesbian, gay, or bisexual | Random digit dialing | Psychological, physical, sexual; victimization; modified CTS, Johnson & Sacco, 1995 | Outcome: IPV victimization; Independent variables: sexual identity, gender, relationship status, education, physical/mental “limitations” |

| Barrientos et al. (2018). Sociodemographic characteristics of gay and lesbian victims of intimate partner psychological abuse in Spain and Latin America | Cross-sectional primary data analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 640; Spain, Mexico, Venezuela, Chile; 45.2% lesbian | Convenience sampling using social media and through LGBQ organizations | Psychological; victimization; self-designation as a victim; EAPA-P | Outcomes: psychological IPV victimization; Independent variables: demographic variables, suicide ideation, alcohol and drug use |

| Battista et al. (2021). Emotional abuse among lesbian Italian women: Relationship consequences, help-seeking and disclosure behaviors. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 165; Italy; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling from LGBT+ social media groups and organizations | Psychological; victimization; MMEA | Outcomes: psychometric validation of Italian MMEA, dissolution due to IPV, IPV disclosure; Independent variables: frequency of abuse |

| Bimbi et al. (2007). Substance use and domestic violence among urban gays, lesbians and bisexuals. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered survey | N = 1048; U.S. (New York metropolitan area); 37.7% bisexual, lesbian, or queer women | Convenience sampling using a street-intercept survey method with data collected at two large LGB events | Physical and non-physical (psychological); victimization; measure by Greenwood et al., 2002 | Outcome: substance use; Independent variables: physical and non-physical IPV victimization |

| Blosnich & Bossarte (2009). Comparisons of intimate partner violence among partners in same-sex and opposite-sex relationships in the United States. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (2005–2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System); phone interviews | N = 7998; U.S. (national); 1.1% female victims of female perpetrators | Random digit dialing | Psychological, physical, sexual; victimization; optional IPV module from BRFSS | Outcomes: prevalence of IPV, poor mental health, self-perceived health, low satisfaction with life; Independent variables: sexual orientation, gender |

| Brown et al. (2015). Cancer risk factors, diagnosis and sexual identity in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health. | Longitudinal secondary analysis (Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health); self-administered mailed survey | N = 10,451; Australia; 2% SMW | Probability sampling | Physical; victimization; measure not specified | Outcomes: cancer diagnosis, screening, and treatment, behavioral cancer risk factors, physical and mental heath, experiences of violence (including physical IPV); Independent variable: sexual identity |

| Carvalho et al. (2011). Internalized sexual minority stressors and same-sex intimate partner violence. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 565; U.S.; 46% lesbian women | Convenience sampling from gay and lesbian newspapers, list serves, festivals, bookstores, and other organizations | Unspecified type of IPV; victimization, perpetration; 2 items assessing self-designation as victim and as perpetrator | Outcomes: lifetime IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variables: outness, internalized homophobia, stigma consciousness |

| Castro et al. (2020). Assessing intimate partner violence in a control balance theory framework. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 435; Southwest U.S.; 6.7% LGBT women | Convenience sampling from undergraduates in introductory psychology course | Physical; victimization and perpetration; 9 items from CTS | Outcome: physical IPV; Independent variables: control imbalance (between partners), self control |

| Charak et al. (2019). Patterns of childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence, emotion dysregulation, and mental health symptoms among lesbian, gay, and bisexual emerging adults... | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 288; U.S.; 16% lesbian, 41.3% bisexual women | Convenience sampling using Amazon Turk | Physical, psychological, sexual coercion, cybervictimization; victimization; CTS-2 and Cyberaggession in Relationships Scale (CARS) | Outcomes: latent classes of IPV, cybervictimization, and childhood trauma; Independent variables: emotion dysregulation, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, alcohol use |

| Chen et al. (2020). Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (NISVS); interviewer-administered phone survey | N = 32,512; U.S. (national); 1.3% bisexual women, 0.9% lesbian women | Random digit dialing | Physical, sexual; victimization; researcher-developed questions | Outcomes: sexual violence, stalking, physical violence, IPV-related impacts; Independent variable: sexual orientation |

| Conron et al. (2010). A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (Massachusetts Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System); interviewer-administered telephone survey | N = 67,359; U.S. (Massachusetts); 0.1% lesbian; 0.01% bisexual women | Random digit dialing | Physical; victimization; 1 item listing physical IPV behaviors (ever been hit, slapped, pushed, kicked, physically hurt, or threatened) | Outcomes: self-rated health, mental health, BMI, cardiovascular disease risk factors, lifetime physical IPV; Independent variable: sexual identity |

| Coston (2017). Power and inequality: Intimate partner violence against bisexual and non-monosexual women in the United States. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (NISVS); interviewer-administered phone survey | N = 2,657; U.S. (national); 0.08% lesbian women, 18.7% bisexual women | Random digit dialing | Physical, sexual, psychological, control, stalking; victimization; NISVS IPV measures | Outcomes: prevalence of IPV; Independent variables: sexual identity, having a male partner, aggregate social power/inequality |

| Coston (2019). Disability, sexual orientation, and the mental health outcomes of intimate partner violence: A comparative study of women in the U.S. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (NISVS); interviewer-administered phone survey | N = 3,542; U.S. (national); 4.2% bisexual women | Random digit dialing | Physical, sexual, psychological, control, stalking; victimization; NISVS IPV measures | Outcomes: post-IPV mental health outcomes (difficulty sleeping, missing school or work, PTSD symptoms, self-reported wellbeing); Independent variables: disability and sexual orientation |

| Coston (2020). Patterns of post-traumatic health care service need and access among bisexual and non-monosexual women in the U.S. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (NISVS); interviewer-administered phone survey | N not reported; U.S. (national); 5.1% bisexual-identified / 16.1% behaviorally bisexual women | Random digit dialing | Physical, sexual, psychological, control, stalking; victimization; NISVS IPV measures | Outcomes: healthcare-seeking behaviors; Independent variables: bisexual identification, social inequality, age |

| Craft et al. (2008). Stress, attachment style, and partner violence among same-sex couples. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered in-person survey | N = 87; Midwestern U.S.; 47% lesbian women | Convenience sampling: referrals from mental health and community centers; advertisements from lesbian/gay newspapers | Psychological, physical, sexual; perpetration; CTS-2 | Outcomes: IPV perpetration; Independent variable: perceived stress; Mediator: attachment style |

| Daigle & Hawk (2021) Sexual orientation, revictimization, and polyvictimization. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (NISVS); interviewer-administered phone survey | N = 232,458,335; U.S. (national); among women 93.4% heterosexual, 6.6% LGB | Random digit dialing | Psychological, coercive control and entrapment, physical; victimization; NISVS IPV measures | Outcomes: IPV victimization, general sexual violence, polyvictimization; Independent variable: sexual identity |

| Dardis et al. (2017). Intimate partner violence among women veterans by sexual orientation. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (Women Veterans and IPV-related Care Survey); self-administered online survey | N = 411; U.S.; 4.4% lesbian, 3.9% bisexual women, 1.2% not sure, 1% other | Survey panel recruited using probability sampling | Physical, sexual, psychological, stalking; victimization; HARK tool, modified stalking items from NVAW survey | Outcomes: IPV victimization, IPV-related PTSD; Independent variable: sexual orientation |

| Descamps et al. (2000). Mental health impact of child sexual abuse, rape, intimate partner violence, and hate crimes in the National Lesbian Health Care Survey. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (National Lesbian Health Care Survey); self-administered paper survey | N = 1,925; U.S. (national); 100% lesbian | Regional multi-stage distribution | Physical, sexual; victimization; measure not specified | Outcomes: daily stress, anxiety, depression, drug and alcohol abuse; Independent variables: CSA, rape, IPV victimization, hate crimes |

| Dyar et al. (2020). Dimensions of sexual orientation and rates of intimate partner violence among young sexual minority individuals assigned female at birth... | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered survey | N = 368; Chicago, IL, U.S.; 24.7% lesbian/gay, 39.7% bisexual, 10.3% queer, 18.2% pansexual, 7.1% other | Convenience sampling from SGM organizations, health fairs, SGM high school and college groups, social media advertisements | Psychological, physical, sexual; victimization; CTS-2 | Outcomes: IPV victimization; Independent variables: sexual identity, attraction, and behavior; Mediators: perceived partner jealousy |

| Eaton et al. (2008). Examining factors co-existing with interpersonal violence in lesbian relationships. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered in-person survey | N = 226; Atlanta, GA, U.S>; 100% women who had a same-sex partner in last 5 years | Convenience sampling from Atlanta Gay Pride Festival (June 2005) | Physical, psychological; victimization; measure from Burke et al., 2002 | Outcomes: substance use and HVI/STI risk behaviors, reporting IPV, attitudes toward IPV, relationship power dynamics; Independent variable: IPV history |

| Edwards et al. (2015). Physical dating violence, sexual violence, and unwanted pursuit victimization: A comparison of incidence rates among sexual-minority and heterosexual college students. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 6,030; New England, U.S.; 14.4% behaviorally sexual minority women | Convenience sampling from 8 universities | Physical; victimization; 16 item Safe Dates Physical Violence Victimization Scale | Outcomes: physical IPV victimization, sexual assault victimization, unwanted pursuit victimization; Independent variable: sexual orientation (behavior) |

| Flentje et al. (2016). Mental and physical health among homeless sexual and gender minorities in a major urban U.S. city. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (San Francisco 2015 Homeless Survey); interviewer-administered survey | N = 1,027; San Francisco, CA, U.S.; 5.5% lesbian women, 6.4% bisexual women, 2.0% queer or other | Systematic sampling; homeless survey collectors gave the survey to every third eligible person encountered | Unspecified type of IPV (single item assessing general IPV); victimization; 1 item assessing self-designation as victim | Outcomes: chronic health problems, mental health problems, drug/alcohol abuse, IPV; Independent variable: sexual orientation |

| Fortunata & Kohn (2003). Demographic, psychosocial, and personality characteristics of lesbian batterers. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered mail-in survey | N = 92; San Francisco, CA, U.S.; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling through advertisements in gay/lesbian organizations | Physical, psychological; perpetration; 1 item assessing self-designation as perpetrator | Outcomes: IPV perpetration; Independent variable: childhood physical and sexual abuse, alcohol/drug use problems, psychopathology |

| Gabbay & Lafontaine (2017). Understanding the relationship between attachment, caregiving, and same sex intimate partner violence. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 310; Canada and U.S.; 31.0% lesbian women, 18.1% bisexual women, 16.5% other | Convenience sampling through advertisements and recruitment at community events | Physical, psychological, sexual; victimization, perpetration; CTS-2 | Outcomes: IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variables: attachment style, caregiving dimensions |

| Gaman et al. (2017). Understanding patterns of intimate partner abuse in male-male, male–female, and female–female couples. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 214; U.S.; 8.4% female-female couples | Convenience sampling through social media advertisements | Physical, psychological, sexual; victimization; HITS questionnaire, modified Renzetti questionnaire | Outcomes: demographics, clinical characteristics (type of abuse); Independent variables: gender pairings of partners |

| Glick et al. (2020). Structural vulnerabilities and HIV risk among sexual minority female sex workers (SM-FSW) by identity and behavior in Baltimore, MD. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (SAPPHIRE Study); interview-administered CAPI survey | N = 247; Baltimore, MD, U.S.; 25.5% sexual minority-identified women | Targeted time-location sampling from locations selected through mapping of arrest data | Physical, sexual; victimization; CTS-2 | Outcomes: homelessness, arrest, childhood abuse, IPV, HIV, substance use, sex work characteristics; Independent variables: sexual orientation by identity and behavior |

| Goldberg & Meyer (2013). Sexual orientation disparities in history of intimate partner violence: Results from the California Health Interview Survey. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (California Health Interview Survey); interviewer-administered telephone CAPI survey | N = 30,373; California, U.S.; 0.9% lesbian women, 0.8% bisexual women, 0.3% WSW | Random digit dialing | Physical, sexual; victimization; measure not specified | Outcomes: IPV victimization; Independent variables: sexual orientation |

| Graham et al. (2019). Intimate partner violence among same-sex couples in college: A propensity score analysis. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (International Dating Violence Survey); interviewer-administered survey | N = 4,081; U.S.; 1.5% women in same-sex relationships | Convenience sampling from universities | Physical, psychological, sexual; perpetration, victimization; 10 binary variables created from CTS-2 | Outcomes: IPV victimization, injury, any type of violence; Independent variables: mixed- or same-sex relationship |

| Harper et al. (2021) Mental health challenges and needs among sexual and gender minority people in western Kenya. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered paper or online survey | N = 527; Kenya; 24.9% cisgender SMW | Convenience sampling from community venues | Specific types of IPV not reported; victimization; investigator-developed instrument | Outcomes: psychological distress, PTSD, alcohol and substance use, IPV, SGM-based violence; Independent variables: sexual and gender identity |

| Heintz & Melendez (2006). Intimate partner violence and HIV/STD risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; survey administer by counselor | N = 58; New York, NY, U.S.; 19% lesbian-identified WSW | Convenience sampling from community-based organization | Sexual; victimization; measure not specified | Outcomes: sexual IPV victimization, safer sex frequency, condom use, safer sex negotiation; Independent variables: sexual orientation |

| Hellemans et al. (2015). Intimate partner violence victimization among non-heterosexuals: Prevalence and associations with mental and sexual well-being. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered CAPI survey and online survey | Sample 1 N = 1,690, sample 2 N = 2,401; Flanders, Belgium; 5% non-heterosexual women in sample 1, 36% in sample 2 | Probability sampling used for sample 1; convenience sampling from social media, advertisements, and LGB parties used for sample 2 | Physical, psychological; victimization; CTS | Outcomes: physical and psychological IPV, mental health; Independent variables: sexual orientation, gender |

| Hirschel & McCormack (2021) Same-sex couples and the police: A 10-year study of arrest and dual arrest rates in responding to incidents of intimate partner violence. | Secondary analysis of National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS) from 2000–2009 | N = 2,625,753; U.S.; 2.1% female couples | N/A | Physical, intimidation; perpetration, victimization; IPV categories defined by the Uniform Crime Report (aggravated assault, simple assault, intimidation) | Outcomes: Arrest or no arrest, dual arrest or single arrest; Independent variables: sex of couple, most serious offense, location of incident, racial dyad, primary aggressor law, warrantless arrest law |

| Holmes et al. (2020). The association between demographic, mental health, and intimate partner violence victimization variables and undergraduate women’s intimate partner violence perpetration | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 398; Midwestern U.S.; 18.6% women with at least some degree of same-sex attraction | Convenience sampling from undergraduate psychology courses | Physical, sexual, psychological, stalking, cyberstalking; perpetration, victimization; SVAWS, PMWI-SF, Stalking Behavior Checklist, modified Electronic Intrusion Scale | Outcomes: IPV perpetration; Independent variables: demographic variables, mental health, IPV victimization |

| Hughes et al. (2010). Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions); structured diagnostic in-person interviews | N = 34,653; U.S. (national); 0.4% lesbian women, 0.5% bisexual women, 0.3% women who are not sure about sexual identity | Probability sampling | Physical; victimization; 1 item measuring IPV behaviors (ever physically attacked or badly beaten up) | Outcomes: substance use disorder; Independent variables: sexual identity, victimization (including IPV); Moderators: sexual identity and victimization interactions |

| Ireland et al. (2017). Partner abuse and its association with emotional distress: A study exploring LGBTI relationships. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 287; Australia; 84.9% lesbian, gay, or homosexual, 9% bisexual, 6.1% other (full sample) | Convenience sampling through LGBTI communities | Psychological; perpetration, victimization; Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse | Outcomes: emotional distress, anxiety, depression, support seeking; Independent variables: psychological IPV victimization; Moderators: resilience traits, relationship satisfaction |

| Jacobson et al. (2015). Intimate partner violence: Implications for counseling self-identified LGBTQ college students engaged in same-sex relationships. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 278; U.S.; 55.4% LGBTQ-identified women | Convenience sampling through LGBTQ student organizations from 40 universities across U.S. | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; Victimization in Dating Relationships Scale, modified Safe Dates | Outcomes: IPV victimization, attitudinal acceptance of IPV; Independent variable: gender |

| Jones & Raghavan (2012). Sexual orientation, social support networks, and dating violence in an ethnically diverse group of college students. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self report | N = 114; Northeast U.S.; 23.7% LGB women | Convenience sampling from undergraduate courses | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; CTS-2 | Outcomes: dating IPV perpetration and victimization, composition of social support network, social network dating violence; Independent variables: gender, sexual orientation |

| Kelley et al. (2015). Discrepant alcohol use, intimate partner violence, and relationship adjustment among lesbian women and their same-sex intimate partners. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 819; U.S.; 71.1% only lesbian, 26.7% mostly lesbian, 2.2% other, 0.5% prefer not to answer | Convenience sampling from online market research panels | Physical, psychological; victimization; CTS-2, PMWI | Outcome: relationship satisfaction; Independent variables: IPV victimization, relationship length, drinking, alcohol quantity discrepancy (between self and partner) |

| Kelly et al. (2011). The intersection of mutual partner violence and substance use among urban gays, lesbians, and bisexuals. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered in-person paper survey | N = 2,200; New York and Los Angeles, U.S.; 19% lesbian or bisexual women | Convenience sampling using street intercept at four large GLB community events | Physical, nonphysical; perpetration, victimization; measure adapted from Greenwood et al., 2002 | Outcomes: substance use and substance abuse treatment; Independent variables: IPV perpetration or victimization |

| Kimerling et al. (2016). Prevalence of intimate partner violence among women veterans who utilize Veterans Health Administration primary care. | Retrospective cohort study, secondary analysis (Women’s Overall Mental Health Assessment of Needs); interviewer-administered telephone survey | N = 6,287; U.S.; 7% lesbian or bisexual women | Probability sampling | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; HARK tool | Outcome: past year IPV; Independent variables: demographics, sexual identity, military characteristics, primary care characteristics |

| Lehavot et al. (2009). Abuse, mastery, and health among lesbian, bisexual, and two-spirit American Indian and Alaska Native women. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered survey | N = 152; U.S.; 38% lesbian, 45% bisexual women, 17% two-spirit | Random digit dialing | Physical; victimization; Index of Spouse Abuse | Outcomes: mental health, physical health; Independent variables: IPV, physical assault, sexual assault, child sexual contact, childhood trauma; Mediator: mastery (sense of control) |

| Lewis et al. (2014). Sexual minority stressors and psychological aggression in lesbian women’s intimate relationships... | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 220; East, Midwest, South, and West U.S.; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling online using a large market research firm | Psychological; perpetration, victimization; CTS-2 physical subscale | Outcome: composite measure of psychological IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variables: internalized homophobia, social constraints; Mediators: rumination, relationship satisfaction |

| Lewis et al. (2015). Emotional distress, alcohol use, and bidirectional partner violence among lesbian women. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 414; U.S.; 74.9% only lesbian, 23.4% mostly lesbian, 1.7% other | Convenience sampling using online market research panels | Physical; bi-directional (perpetration and victimization); CTS-2 physical subscale | Outcome: bidirectional IPV; Independent variables: emotional distress (negative affect, rumination, and depressive symptoms) |

| Lewis et al. (2017). Empirical investigation of a model of sexual minority specific and general risk factors for intimate partner violence among lesbian women. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 1051; U.S.; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling using online market research panels | Physical, psychological; perpetration, victimization; PMWI, CTS-2 physical subscale | Outcomes: IPV victimization and perpetration; Independent variables: sexual minority stressors (discrimination, internalized homophobia); Mediators: perpetrator anger, alcohol use and problems, relationship satisfaction |

| Lewis et al. (2018). Discrepant drinking and partner violence perpetration over time in lesbians’ relationships. | Longitudinal primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 1052; U.S.; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling using online market research panels | Physical, psychological; perpetration; PMWI, CTS-2 physical subscale | Outcomes: physical and psychological IPV perpetration; Independent variables: discrepant drinking |

| Lin et al. (2020). Female same-sex bidirectional intimate partner violence in China. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 225; China; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling using online advertisements via social media | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; 15-item Chinese CTS-2 | Outcome: bidirectional IPV; Independent variables: IPV justification, endorsement of heterosexual norms, demographics |

| Longares et al. (2016). Collective self-esteem and depressive symptomatology in lesbians and gay men... | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 357; Spain; 42% lesbian women | Convenience sampling | Psychological; victimization; Escala de Abuso Psicológico Aplicado en la Pareja | Outcome: depressive symptoms; Independent variables: self-esteem, self-stigma; Mediator: self-stigma; Moderator: psychological IPV victimization |

| Mak et al. (2010). Prevalence of same-sex intimate partner violence in Hong Kong. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 339; Hong Kong; 64.3% sexual minority women | Convenience sampling from LGB-friendly organizations and online platforms | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; CTS-2 | Outcomes: IPV victimization and perpetration; Independent variable: sexual orientation |

| Mason et al. (2016). Minority stress and intimate partner violence perpetration among lesbians... | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 342; U.S.; 83.3% only lesbian, 16.7% mostly lesbian | Convenience sampling through social media and LGBT organizations | Physical; perpetration; CTS-2 physical subscale | Outcome: physical IPV perpetration; Independent variables: discrimination, minority stress, general life stress |

| McCauley et al. (2015). Sexual and reproductive health indicators and intimate partner violence victimization among female family planning clinic patients who have sex with women and men. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; interviewer-administered in-person survey | N = 3,455; Western PA, U.S.; 9.6% WSWM | Convenience sampling from clinic patients | Physical, sexual; victimization; 3 items from CTS-2, Sexual Experiences Survey | Outcomes: sexual risk behavior, reproductive coercion, STI diagnosis, pregnancy, reasons for seeking care; Independent variables: sexual orientation, IPV |

| McKenry et al. (2006). Perpetration of gay and lesbian partner violence: A disempowerment perspective | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered in-person survey | N = 77; Midwestern U.S.; 48.1% lesbian women | Convenience sampling using clinic and community center referrals, gay/lesbian newspaper ads | Physical; perpetration; CTS-2 | Outcome: physical IPV perpetration; Independent variables: individual, family of origin, and intimate relationship characteristics |

| McNair et al. (2018). Health service use by same-sex attracted Australian women for alcohol and mental health issues: A cross-sectional study. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 521; Australia; 57.0% lesbian, 17.1% bisexual, 18.0% queer/pansexual, 6.9% other | Convenience sampling using social media, community listings | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; 3 items assessing self-designation as victim | Outcomes: treatment utilization for mental health and alcohol use; Independent variables: IPV, sexual identity, social support, LGBT community connectedness, having a general practitioner (GP), disclosed sexuality to GP, discrimination within health services, income, service need |

| Messinger (2011). Invisible victims: Same-sex IPV in the national violence against women survey. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (NISVS); interviewer-administered phone survey | N = 14,182; U.S; 1% sexual minority women | Random digit dialing | Physical, sexual, psychological, control; victimization; NVAWS | Outcome: IPV victimization; Independent variables: sex, sexual orientation |

| Messinger et al. (2019). Sexual and gender minority intimate partner violence and childhood violence exposure. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; computer-assisted self report survey | N = 457; IL, U.S.; 24.1% lesbian, 37.6% bisexual, 12.3% queer, 17.9% pansexual, 8.1% other sexual identity | Convenience sampling from SGM organizations, health fairs, SGM high school and college groups, social media advertisements | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; one 1-item measure for each IPV type | Outcomes: IPV victimization and perpetration; Independent variable: childhood victimization exposure |

| Miller et al. (2001). Domestic violence in lesbian relationships. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered paper survey | N = 284; Southeast U.S.; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling from a women’s music festival | Physical; perpetration, victimization; CTS | Outcomes: IPV victimization and perpetration; Independent variables: fusion, independence, control, self-esteem |

| Milletich et al. (2014). Predictors of women’s same-sex partner violence perpetration. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 209; U.S.; 55.5% lesbian, 30.6% bisexual, 13.9% heterosexual or straight (100% had past-year relationships with women) | Convenience sampling from LGB and women’s issues listservs, websites, and organizations across two universities | Physical, psychological; perpetration, victimization; CTS-2 physical subscale, MMEA for psychological IPV | Outcome: IPV perpetration; Independent variables: sexual identity, internalized homophobia, dominance/accommodation, fusion, history of parent-child aggression and IPV; Mediators: fusion |

| Mize & Shackelford (2008). Intimate partner homicide methods in heterosexual, gay, and lesbian relationships. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (FBI Supplementary Homicide Reports); national crime records | N = 51,007; U.S. (national); 0.3% women with same-sex partners | N/A | Physical (homicide); perpetration; national crime records | Outcome: homicide brutality; Independent variables: sexual orientation, gender |

| Moracco et al. (2007). Women’s experiences with violence: A national study. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered CATI telephone survey | N = 1,800; U.S.; 2.3% lesbian/bisexual women | Random digit dialing | Physical; victimization; researcher-developed questions | Outcomes: IPV victimization, being followed, physical assault, sexual assault; Independent variables: demographics, sexual orientation, married/cohabitation status, receipt of public assistance |

| Muzny et al. (2018). Psychosocial stressors and sexual health among southern African American women who have sex with women. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (Women’s Sexual health Project); interviewer-administered in-person survey | N = 165; Birmingham, AL, U.S.; 100% WSW | Convenience sampling from clinic patients | Physical, sexual; victimization; 1 item assessing self-designation as victim (combined physical and sexual IPV) | Outcomes: alcohol/drug use during sexual encounters, STI history and STI current diagnosis, sex in exchange for money/drugs; Independent variables: depressive symptoms, IPV, incarceration |

| Oginni et al. (2021). Do psychosocial factors mediate sexual minorities’ risky sexual behaviour? A twin study. | Longitudinal secondary analysis (U.K. Twins Early Development study); self-administered mailed or online survey | N = 9697; U.K.; 48.9% exclusively heterosexual female, 9.2% mostly heterosexual female, 1.6% bisexual female, 1.3% mostly gay/lesbian female, 1.3% exclusively gay/lesbian female | Contacted twins and parents in U.K. national registry of twins set up by Office for National Statistics | Psychological, physical; victimization; 6 items adapted from CDC questions | Outcome: risky sexual behavior (number of lifetime sexual partners); Independent variable: sexual orientation; Mediators: psychosocial adversities, substance use problems |

| Owen & Burke (2004). An exploration of prevalence of domestic violence in same-sex relationships. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered mailed survey | N = 66; Virginia, U.S.; 50% SMW | Convenience sampling from a mail marketing company | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; researcher-developed questions adapted from Burke, 1998 | Outcome: IPV victimization; Independent variables: sex, sexual orientation |

| Pepper & Sand (2015). Internalized homophobia and intimate partner violence in young adult women’s same-sex relationships. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered mailed survey | N = 40; location unspecified; 72.5% lesbian, 12.5% bisexual, 10% did not self-identify, 2.5% queer | Convenience sampling from LGBTQ college and university groups | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; CTS-2 | Outcomes: internalized homophobia, psychological maladjustment; Independent variables: IPV perpetration and victimization |

| Pittman et al. (2020). Double jeopardy: Intimate partner violence vulnerability among emerging adult women through lenses of race and sexual orientation. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (National College Health Assessment); self-administered paper or electronic survey | N = 9,435; U.S. (national); 5.1% bisexual, 1.1% lesbian, 7.1% asexual, 1.5% pansexual, 1.5% questioning, 0.4% other | Unspecified sampling/recruitment method; colleges administered survey to their students | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; researcher-developed questions | Outcome: IPV victimization; Independent variables: sexual orientation, race/ethnicity |

| Poorman & Seelau (2001). Lesbians who abuse their partners: Using the FIRO-B to assess interpersonal characteristics. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-report | N = 15; U.S.; 100% lesbian | Convenience sampling from therapy group participants | Unspecified type of IPV; perpetration, victimization; no measure used (participants referred from therapy group) | Outcomes: personality/interpersonal traits measured by FIRO-B measure; Independent variable: group membership (abusive lesbian vs. normative sample) |

| Pyra et al. (2014). Sexual minority status and violence among HIV infected and at-risk women. | Longitudinal secondary analysis (Women Interagency HIV Study); interviewer-administered in-person survey, specimen collection, physical exams | N = 1,743; NYC, Chicago, DC, and San Francisco, U.S.; 7.8% bisexual women, 4.7% lesbian | Convenience sampling from clinical research sites | Psychological; victimization; researcher-developed questions | Outcomes: psychological IPA, general sexual violence, general physical violence; Independent variables: sexual identity, sexual behavior; Mediators: substance abuse, high risk sex |

| Rausch (2016). Systemic acceptance of same-sex relationships and the impact on intimate partner violence among cisgender identified lesbian and queer individuals. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered survey | N = 87; U.S. and Canada; 100% lesbian or queer | Unspecified sampling/recruitment method | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; Abusive Behavior Inventory | Outcomes: perceived level of acceptance of same-sex partnership from family, school, media, lesbian and queer community; Independent variables: childhood abuse, adult IPV victimization |

| Rausch (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence in lesbian and queer relationships. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered survey | N = 87; U.S. and Canada; 100% lesbian or queer | Unspecified sampling/recruitment method | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; Abusive Behavior Inventory | Outcome: coping; Independent variables: adult IPV victimization, adverse childhood experiences |

| Reisner et al. (2013). Sexual orientation disparities in substance misuse: The role of childhood abuse and intimate partner violence among patients in care at an urban community health center. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; self-administered paper survey | N = 2,653; Boston, MA, U.S.; 8.9% lesbian; 2.6% bisexual women, 2.4% other non-heterosexual women | Convenience sampling from clinics | Physical, sexual; victimization; 1 binary item combining physical and sexual abuse | Outcomes: lifetime substance abuse, childhood abuse, IPV victimization; Independent variables: sexual orientation, childhood abuse, IPV victimization; Mediators: childhood abuse, IPV victimization |

| Reuter et al. (2017). Intimate partner violence victimization in LGBT young adults: Demographic differences and associations with health behaviors. | Longitudinal primary analysis; self-report | N = 172; Chicago, IL, U.S.; 29.4% lesbian, 32.9% bisexual, 7.7% questioning/unsure/ other (across all genders) | Convenience sampling from LGBT community centers, neighborhoods, and organizations | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; 1 item each for physical abuse and forced sex, 3 items for psychological abuse | Outcomes: depression and anxiety scores, substance use, sexual risk-taking behaviors; Independent variables: IPV victimization, race/ethnicity, gender |

| Scheer et al. (2020). Gender-based structural stigma and intimate partner violence across 28 countries... | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (Violence Against Women Survey); interviewer-administered in-person survey | N = 42,000; 28 European Union member states; 1.7% sexual minority women | Random probability sampling | Physical, sexual; victimization; Violence Against Women Survey | Outcomes: lifetime substance abuse, childhood abuse, IPV; Independent variables: sexual orientation, childhood abuse, IPV; Mediators: childhood abuse, IPV |

| Scheer & Baams (2021). Help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults exposed to intimate partner violence victimization. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 354; U.S.; 50.8% sexual minority cisgender women | Convenience sampling from LGBTQ- and IPV-related online groups, listservs, and forums | Psychological, physical, identity; victimization; PMWI, CTS-2 physical subscale, Identity Abuse Scale | Outcome: IPV-related help-seeking; Independent variable: gender identity |

| Schwab-Reese et al. (2021) A comparison of violence victimization and polyvictimization experiences among sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents and young adults. | Longitudinal secondary analysis (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health); interviewer-administered survey | N = 9,828; U.S.; 50.0% female; among total sample, 85.5% 100% heterosexual, 9.7% mostly heterosexual, 1.5% bisexual, 0.8% mostly homosexual, 1.3% 100% homosexual | Probability sampling | Physical, threats; victimization; researcher-developed instrument | Outcomes: child maltreatment, general criminal assault, IPV, sexual assault, polyvictimization; Independent variables: sexual orientation |

| Steele et al. (2020). Influence of perceived femininity, masculinity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status on intimate partner violence among sexual-minority women. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered telephone survey | N = 608; Chicago, IL, U.S.; 57.1% exclusively lesbian; 16.1% mostly lesbian, 25.8% bisexual | Convenience sampling using a broad range of recruitment methods | Physical, sexual, psychological; victimization; modified CTS, 1 threat of outing item | Outcome: IPV victimization; Independent variables: perceived femininity and masculinity, race/ethnicity, SES |

| Stevens et al. (2010). A comparison of victimization and perpetration of intimate partner violence among drug abusing heterosexual and lesbian women. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered survey | N = 434; Tucson, AZ, U.S.; 5.5% lesbian | Targeted recruitment (street outreach) and snowball sampling | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; Partner Abuse Scale | Outcomes: IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variable: sexual orientation |

| Sutter et al. (2019). Patterns of intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration among sexual minority women: A latent class analysis. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 150; location not specified; 38.7% lesbian, 32.7% bisexual women, 28.6% queer or other women | Convenience sampling from LGBTQ organizations | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; CTS-2 | Outcome: IPV class (severity/type of IPV from latent class analysis); Independent variable: heterosexism |

| Swann et al. (2020). Longitudinal transitions in intimate partner violence among female assigned at birth sexual and gender minority youth | Longitudinal primary analysis; mode of administration not specified | N = 433; U.S.; 38.1% bisexual, 21.5% lesbian, 17.3% pansexual, 11.8% queer, 3.7% questioning, 3.0% gay, 1.8% asexual, 1.4% straight, 1.4% other | Convenience sampling from SGM organizations, health fairs, SGM high school and college groups, social media advertisements | Physical, sexual, psychological; perpetration, victimization; SGM-CTS2, SGM-Specific IPV Tactics Scale, Cyber Abuse Scale, Coercive Control Scale | Outcome: IPV class (no or low IPV, psychological IPV only, high IPV); Independent variable: longitudinal study wave (time) |

| Swiatlo et al. (2020). Intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization among young adult sexual minorities. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, Wave 4 only); interviewer-administered survey | N = 13,653; U.S. (national); 8.4% mostly heterosexual women, 1.2% bisexual women, 0.9% homosexual women | Probability sampling | Physical, sexual, threats; perpetration, victimization; researcher-developed questions | Outcomes: IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variable: sexual orientation |

| Szalacha et al. (2017). Mental health, sexual identity, and interpersonal violence: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Women’s Health Study. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, Wave 3); self-administered mailed survey | N = 8,850; Australia; 6.4% mainly heterosexual women, 1.1% bisexual women, 1.1% mainly or exclusively lesbian | Random sampling within age groups from database of Medicare Australia | Unspecified type of IPV (single item assessing general IPV); victimization; 1 item selfdesignation as having been in a violent relationship | Outcomes: interpersonal violence, mental health outcomes, life satisfaction; Independent variable: sexual identity |

| Telesco (2003). Sex role identity and jealousy as correlates of abusive behavior in lesbian relationships. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered survey | N = 105; New York, NY, U.S.; 100% lesbian women | Convenience sampling from NYC LGBT Community Center | Physical, psychological; perpetration; Abusive Behavior Inventory | Outcome: IPV perpetration; Independent variables: dependency, jealousy, power imbalance, masculinity, and femininity |

| Trujillo et al. (2020). Unique and cumulative effects of intimate partner cybervictimization types on alcohol use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual emerging adults. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 277; U.S.; 17% lesbian, 43% bisexual women | Convenience sampling; recruitment via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk internet marketplace | Psychological, sexual, stalking, cyber IPV; victimization; Cyberaggression in Relationships Scale | Outcome: alcohol use; Independent variables: cyber IPV |

| Turell (2000). A descriptive analysis of same-sex relationship violence for a diverse sample. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered mail survey | N = 499; Southeast U.S.; 39% lesbian, 11% gay women | Convenience sampling using membership lists of local LGBTQ organizations | Physical, psychological, sexual; victimization; researcher-developed questions | Outcome: IPV victimization; Independent variables: gender, sexual identity |

| Turell et al. (2018). Disproportionately high: An exploration of intimate partner violence prevalence rates for bisexual people. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 439; U.S.; 47% bisexual women | Convenience sampling; recruitment via Facebook and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk internet marketplace | Physical, psychological, sexual; perpetration, victimization; Composite Abuse Scale, Abusive Behavior Inventory | Outcome: lifetime IPV; Independent variables: gender, race, having children, connectedness to bisexual community, age, bi-negativity, perceived/real infidelity |

| Ummak et al. (2021). Untangling the relationship between internalized heterosexism and psychological intimate partner violence perpetration... | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 449; Denmark and Turkey; 54.3% lesbian women, 45.7% bisexual women | Convenience sample from LGBTQ+ organizations | Psychological; perpetration; MMEA | Outcome: psychological IPV perpetration; Independent variables: internalized heterosexism, sexual orientation, country; Moderators: sexual orientation, country |

| Valentine et al. (2015). The predictive syndemic effect of multiple psychosocial problems on health care costs and utilization among sexual minority women. | Longitudinal secondary analysis; self-administered paper survey and community health center records | N = 341; MA, U.S.; 76.5% lesbian, 23.5% bisexual women | Clinic patients receiving medical or mental health care at a community health center over a 12-month period from 2001–2002 | Physical, sexual; victimization; 1 item listing physical and sexual IPV behaviors | Outcomes: Medical and mental health care costs, medical and mental health care utilization; Independent variables: childhood sexual abuse, IPV, problematic substance use, mental health distress |

| Valentine et al. (2017). Disparities in exposure to intimate partner violence among transgender/gender nonconforming and sexual minority primary care patients. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; electronic medical records | N = 7,572; MA, U.S; 5.3% lesbian, 2.4% bisexual women, 3.4% “something else/don’t know” | All clinic patients receiving routine primary care in 2014 | Physical, psychological, sexual; victimization; Abuse Assessment Screen, researcher-developed questions for psychological IPV | Outcome: Past-year IPV; Independent variables: sexual identity, gender identity |

| Velopulos et al. (2019). Comparison of male and female victims of intimate partner homicide and bidirectionality... | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; national surveillance data (National Violent Death Reporting System); government records | N = 6,348; U.S.; 0.7% women in same-sex pairings | Retrospective review of government records from 2003 to 2015 | Physical (homicide); perpetration, victimization; government records (death certificates, coroner records, law enforcement reports) | Outcomes: Victim and perpetrator characteristics, bidirectionality, circumstances of the homicide; Independent variables: Gender of perpetrator and victim, same- vs. different-sex relationship, race, mental illness diagnosis, history of abuse, other crime, preceding argument, etc. |

| Wathen et al. (2018). The impact of intimate partner violence on the health and work of gender and sexual minorities in Canada. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered online survey | N = 7,918; Canada; 2.9% SMW | Convenience sampling using membership lists of labor organizations | Unspecified type of IPV; victimization; 3 items assessing self-designation as victim | Outcomes: lifetime IPV, IPV-related work impacts, physical and mental health, quality of life; Independent variables: gender, sexual identity |

| Whitehead et al. (2020). Same-sex intimate partner violence in Canada: Prevalence, characteristics, and types of incidents reported to police services. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (Statistics Canada Uniform Crime Reporting Surveys); police reports | N = 346,565; Canada; 2% female victim and female accused | N/A | Physical, psychological, sexual; perpetration, victimization; police reports | Outcomes: IPV prevalence, incident variables (i.e. violation type, victim injury, weapon, etc.); Independent variables: N/A (descriptive only) |

| Whitfield et al. (2021) Experiences of intimate partner violence among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender college students: The intersection of gender, race, and sexual orientation. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis (National College Health Assessment—II (NCHA-II) from 2011–2013); paper or web-based self-administered surveys | N = 88,975; U.S.; among cisgender women 91.8% heterosexual, 1.7% lesbian, 4.5% bisexual, 2.1% unsure. | 120 higher education institutions opted into NCHA-II; students were randomly sampled or all students were included in the sample | Psychological, physical, sexual; victimization; researcher-developed instrument | Outcome: past-year IPV victimization; Independent variables: sexual identity, gender, race/ethnicity |

| Whitton et al. (2019). Intimate partner violence experiences of sexual and gender minority adolescents and young adults assigned female at birth. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered | N = 488; Chicago, IL, U.S.; 23.6% lesbian, 37.1% bisexual, 13.1% queer, 16.8% pansexual, 4.3% questioning, 2.5% asexual, 1.4% other | Convenience sampling from SGM organizations, health fairs, SGM high school and college groups, social media advertisements | Physical, psychological, sexual; perpetration, victimization; SGM-CTS2, Coercive Control Scale, SGM-Specific IPV Tactics Scale, Cyber Abuse Scale | Outcomes: IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variables: demographics |

| Whitton et al. (2019). A longitudinal study of IPV victimization among sexual minority youth. | Longitudinal primary analysis; interviewer-administered in-person survey | N = 248; Chicago, IL, U.S.; 34.0% gay male, 27.9% lesbian, 28.7% bisexual, 9.4% questioning (full sample) | Convenience sampling | Physical, sexual; victimization; HIV-Risk Assessment for Sexual Partnerships | Outcome: IPV victimization; Independent variables: demographics, psychological distress, social support |

| Whitton et al. (2021). Exploring mechanisms of racial disparities in intimate partner violence among sexual and gender minorities assigned female at birth. | Cross-sectional primary analysis; interviewer-administered survey | N = 308; U.S.; 27.6% gay/lesbian, 55.5% bisexual/pansexual, 16.9% other AFAB | Convenience sampling from SGM organizations, health fairs, SGM high school and college groups, social media advertisements | Psychological, physical, sexual; perpetration, victimization; SGM-CTS2 | Outcomes: IPV perpetration and victimization; Independent variable: race/ethnicity; Mediators: childhood experiences of violence, discrimination, structural inequalities, sexual minority stressors |

| Wong et al. (2020). The Aloha Study: Intimate partner violence in Hawai’i’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community | Cross-sectional primary analysis; self-administered paper or online survey | N = 477, Hawai’i, U.S.; 54.9% gay, 36.1% lesbian, 16.6% bisexual/pansexual/queer/other (full sample) | Convenience sampling from social media and LGBT-friendly venues | Physical, sexual; victimization; researcher-developed questions | Outcomes: IPV victimization, help-seeking; Independent variables: gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity |

IPV measure names are abbreviated as follows: CTS—Conflict Tactics Scale; CTS-2—Revised Conflict Tactics Scale; PMWI-SF—Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory, Short Form; NISVS—National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey; HARK tool—Humiliate/Afraid/Rape/Kick; HITS questionnaire—pHysical abuse, Insult, Threaten, Scream; SVAWS—Severity of Violence Against Women Scale; EAPA-P—Escala de Abuso Psicológico Aplicado en la Pareja (Scale of Psychological Abuse in Couples); NVAWS—National Violence Against Women Survey; MMEA—Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse

Results

Of the 99 papers included, 48 reported prevalence data of IPV among SMW, 36 examined correlates of IPV among SMW, and 15 examined associations between IPV and health and social outcomes in this population. The majority of studies used validated measures or adaptations of validated measures, such as the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) (Straus, 1979), the Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse (Murphy & Hoover, 1999), or the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (Tolman, 1999) to measure IPV; four studies used law enforcement records, and 30 studies used investigator-developed measures of IPV or did not specify how IPV was measured. Additional key characteristics of the included studies are reported in Table 1. In the following section, results are organized under the following major headings with relevant sub-headings: prevalence of IPV among SMW; correlates of IPV; and physical and mental health, health care, and social outcomes.

Prevalence of IPV among SMW

Findings from studies using large U.S. probability samples suggest that bisexual women are significantly more likely than both heterosexual or lesbian women to report physical, sexual, and/or psychological IPV victimization (Chen, Walters, Gilbert, & Patel, 2020; Conron, Mimiaga, & Landers, 2010; Coston, 2017; Goldberg & Meyer, 2013; Messinger, 2011; Schwab-Reese, Currie, Mishra, & Peek-Asa, 2021). “Mostly heterosexual” women were also at higher risk, with another study using a large probability sample finding that they had 55% and 59% higher odds of experiencing physical and sexual IPV, respectively, compared to exclusively heterosexual women (Swiatlo, Kahn, & Halpern, 2020). In a secondary analysis of U.S. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) data, Daigle and Hawk (2021) found that LGB women were more likely than heterosexual women to experience psychological and physical aggression, coercive control and entrapment, revictimization, and polyvictimization. Only one study using a national probability sample failed to find a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of IPV between SMW and heterosexual women (Moracco, Runyan, Bowling, & Earp, 2007); however, this study combined lesbian and bisexual women in all analyses and asked about physical partner assault only among married or cohabiting women, thereby excluding women who were not living with their partners, or experienced other forms of IPV.

Additional research with smaller or nonprobability samples generally also have found a higher prevalence of IPV among SMW. In a study of IPV among sexual and gender minorities that used electronic medical record data from primary care clinics (N=7,572) in Boston, MA, researchers found that bisexual women had almost four times higher odds of reporting physical or sexual victimization, and over 2 times higher odds of psychological IPV victimization as heterosexual women (Valentine et al., 2017). Two studies of women veterans (N=6287; N=411) found that those who identified as lesbian, bisexual, or queer (combined for analysis) had significantly higher odds than did their heterosexual counterparts of (1) past-year emotional, physical, and sexual IPV victimization (Dardis, Shipherd, & Iverson, 2017; Kimerling et al., 2016), and (2) of lifetime physical and sexual IPV victimization (Dardis et al., 2017). Two additional studies using large community-based convenience samples of SMW (N=1,274; N=6,030) found higher lifetime prevalence (Balsam, Rothblum, & Beauchaine, 2005) and higher past-six month prevalence (Edwards et al., 2015) of physical IPV victimization among SMW than among heterosexual women.

Studies of IPV using behavioral indicators of sexual minority status (e.g., women who have sex with women [WSW], sex with men [WSM], or sex with both men and women [WSWM]) report findings similar to those using identity indicators (Alexander, Volpe, Abboud, & Campbell, 2016; Dyar, Feinstein, Zimmerman, & Newcomb, 2020; Heintz & Melendez, 2006; McCauley et al., 2015). In a study of 3,455 family planning clinic clients in Western Pennsylvania, McCauley et al. (2015) found that WSWM had three times the odds of reporting lifetime IPV as WSM. Further, in a community-based sample of 149 low-income young Black women, Alexander et al. (2016) found that compared to WSM, WSWM were significantly more likely to report lifetime physical IPV and certain types of sexual IPV. Among participants assigned female at birth (AFAB; N=368), Dyar et al. (2020) found that participants who reported both male and female partners in their lifetime were more likely to report having experienced IPV in their current relationships, compared to those with only male or only female partners.

IPV among SMW compared to other sexual and gender minority (SGM) groups.

Thirteen studies compared the IPV prevalence among SMW and other SGM groups; findings from these studies are largely inconsistent. Three studies using convenience samples of sexual minority individuals found no significant gender differences in IPV victimization (Gabbay & Lafontaine, 2017; Owen & Burke, 2004), or IPV perpetration (Craft, Serovich, McKenry, & Ji-Young, 2008; Gabbay & Lafontaine, 2017). However, several convenience sample studies from Southeast Texas (Turell, 2000), the Southwestern U.S. (Castro, Nobles, & Zavala, 2020), Chicago, IL (Reuter, Newcomb, Whitton, & Mustanski, 2017; Whitton, Newcomb, Messinger, Byck, & Mustanski, 2019), Hawaii (Wong, La, Lee, & Raidoo, 2020), and the U.S. as a whole (Gaman, McAfee, Homel, & Jacob, 2017; Jacobson, Daire, & Abel, 2015), found higher rates of physical IPV victimization (Gaman et al., 2017; Reuter et al., 2017; Turell, 2000; Whitton, Newcomb, et al., 2019), physical IPV perpetration (Castro et al., 2020), psychological IPV victimization (Jacobson et al., 2015; Turell, 2000), and sexual IPV victimization (Wong et al., 2020) among SMW compared to SMM. Researchers using a representative sample of college students from 120 schools across the U.S. found that differences in rates of sexual IPV were smaller between sexual minority and heterosexual women than between sexual minority and heterosexual men (Whitfield, Coulter, Langenderfer-Magruder, & Jacobson, 2021). In addition, in two studies using online convenience samples, researchers found that bisexual men had higher overall scores on the Composite Abuse Scale than bisexual women (Turell, Brown, & Herrmann, 2018), and were more likely to report cyber sexual IPV than lesbian and bisexual women (Trujillo, Cantu, & Charak, 2020). Finally, using National Violent Death Reporting System data (N=6,348) Velopulos, Carmichael, Zakrison, and Crandall (2019) found that bidirectional violence was more commonly reported among female and male same-sex couples than among different-sex couples.

IPV among SMW of color.

Few studies examined IPV prevalence among SMW by race/ethnicity. In a cross-sectional study of a community sample of SMW (N=608), Steele, Everett, and Hughes (2020) found that Black and Latina SMW reported higher rates of IPV than White SMW. In addition, in a sample of students from the National College Health Assessment (N=9,435), Pittman and colleagues found that SMW of color were at higher risk of physical IPV than White heterosexual women, White SMW, and heterosexual women of color (Pittman, Riedy Rush, Hurley, & Minges, 2020). In a community-based sample of 488 AFAB sexual minority individuals (including SMW and some non-binary sexual minority individuals), Latinx and Black participants reported two times higher rates of IPV victimization as White participants, and 4.5 to six times higher rates of perpetration as White participants (Whitton, Dyar, Mustanski, & Newcomb, 2019). In another study using a community-based sample of AFAB sexual minority individuals (N=308), researchers found that Black and Latinx participants were more likely to experience multiple types of IPV compared to White participants, and these differences were indirectly associated with higher economic stress, racial/ethnic discrimination, and childhood violence exposures (Whitton, Lawlace, Dyar, & Newcomb, 2021).

Studies of IPV among SMW outside the U.S.

Twelve studies of IPV were conducted outside the US. The methods and foci of these studies were diverse, although most examined prevalence. In a study of self-identified lesbian women in China (N=225), 60% reported bidirectional psychological aggression, and 19% reported more than one type of bidirectional violence (Lin, Hu, Wang, & Xue, 2020). Two studies used data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH). The first found that 27% of SMW, compared to 13% of heterosexual women, reported having ever been in a violent relationship with a partner/spouse (R. Brown, McNair, Szalacha, Livingston, & Hughes, 2015), and another found that “mainly heterosexual,” bisexual, and lesbian women had two to three times the odds of having been in a violent relationship as heterosexual women (Szalacha, Hughes, McNair, & Loxton, 2017). Four studies characterized IPV experiences of SMW in relation to SMM, with inconsistent findings. In convenience sample studies conducted in Kenya (Harper et al., 2021) and Hong Kong (Mak, Chong, & Kwong, 2010), researchers found higher rates of IPV among SMW than SMM, and that SMW were significantly more likely than SMM to question their partner’s sexual orientation as an IPV tactic. However, in a convenience sample of Australian sexual minority individuals (N=287), SMM were more likely to report psychological aggression than SMW (Ireland, Birch, Kolstee, & Ritchie, 2017). Further, in a nationally representative sample from the General Social Survey of Canada, researchers found no significant differences in the proportion of SMW and SMM who reported IPV; however, SMW survivors of IPV reported a significantly higher number of incidents of violence, with bisexual women reporting the highest number (Barrett & St. Pierre, 2013). Finally, researchers in Italy examined the sequelae of emotional abuse among a convenience sample of lesbian women (N=165) and found that most (78%) who reported abuse did not break up with their partners and that frequency of abuse was inversely correlated with likelihood of breaking up (Battista et al., 2021).

IPV among SMW with unique vulnerabilities.

A few studies examined the prevalence of IPV by sexual identity in vulnerable groups of women, such as sex workers, those living with HIV or at high risk for HIV, and those experiencing homelessness or living with substance use disorders. Two studies found no sexual identity differences in rates of IPV, including in a community sample of women with substance use disorders in Tucson, AZ (Stevens, Korchmaros, & Miller, 2010), and among women experiencing homelessness in San Francisco (Flentje, Leon, Carrico, Zheng, & Dilley, 2016). Further, among women living with HIV or at high risk for HIV in four major U.S. cities, Pyra et al. (2014) found that the difference in psychological IPV victimization between bisexual and heterosexual women was fully mediated by high-risk sex and substance use. Among female sex workers in Baltimore, Maryland (N=247), SMW reported greater odds of physical IPV than heterosexual women (Glick et al., 2020), but these differences were no longer statistically significant when the data were analyzed by sexual behavior rather than sexual identity.

Correlates of IPV

Demographic factors.

Differences in rates of IPV among SMW may be explained in part by demographic factors. Hirschel and McCormack (2021) analyzed more than 2.5 million cases of IPV reported to law enforcement in the U.S. and found that female-female couples involved in these incidents were significantly younger than male-male and male-female couples. Steele et al (2020) and others (Barrientos et al., 2018, Descamps, 2000) found that SMW who report IPV tend to have lower income and educational levels. However, Coston (2017) found an association between experiencing violence and greater social power (an aggregate measure of age, race/ethnicity, education, income, immigration status, and indigeneity) among bisexual women. In addition, a Canadian study using police reports found a higher prevalence of IPV among same-sex female couples in rural compared to urban areas (Whitehead, Dawson, & Hotton, 2020), whereas an American study found the opposite (Blosnich & Bossarte, 2009). Differences in how socioeconomic status is operationalized, recruitment and data collection methods, and sample characteristics likely contribute to such discrepancies.

Prior trauma.