Abstract

Relative to the general population, Native Americans (NA) bear a disproportionate burden of suicide-related mortality rates. NA males and females aged 15 to 24 years experience suicide rates nearly 3 times than the U.S. all races rates in this age group. Although efforts have been made to understand and reduce suicide in tribal communities, a large portion has focused on individual characteristics with less attention given to social factors that may also inform suicide. This article aims to build on a local conceptual model of NA youth suicide by examining additional potential social factors through qualitative interviews. Findings from the thematic analysis resulted in the identification of seven perceived social influences: contagion, violence and abuse, discrimination and bullying, negative expectations, spirituality, social support, and cultural strengths. Public health approaches to reduce suicide should consider local social factors that resonate with tribal communities to build resilience.

Keywords: suicide, adolescents, youth, young adults, psychology, psychological issues, qualitative research, Southwestern US

Suicide is a complex problem of increasing public health importance, recognized as the second leading cause of death in those aged 10 to 34 years within the United States in 2017 (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2020). Adding to the complexity of the burden of suicide within the United States is the longitudinal consistency that it poses with age-adjusted rates of suicide increasing 35% from 1999 to 2018 (10.5 per 100,000 to 14.2 per 100,000, respectively; Hedegaard, H., Curtin, S. C., & Warner, M. (2020)). Remarkably, there is also a striking variability in suicide rates by age, gender, racial, and ethnic background. Most critically, Native Americans (NA) experience the highest burden of suicide relative to any other racial or ethnic group in the United States. (NIMH, n.d.). Suicide rates within the NA communities have seen increases since 2009, with age-adjusted rates of 15.4 per 100,000 in 2009 to 22.1 per 100,000 in 2018 (Suicide Prevention Resource Center, n.d.). One of the most at-risk age groups are NAs aged 15 to 24 years, with suicide mortality rates nearly 4 times that of White and U.S. all races (United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2012). More than one-third (36%) of suicides occur among NAs (Leavitt, 2018).

As a caution against the generalization of this complicated issue, rates of suicide differ quite significantly between the 574 federally recognized tribes, making prevention and one-size-fits-all approaches in the way of “evidence-based practices” largely unsuccessful (Livingston et al., 2019). As such, it becomes particularly important to recognize the etiology and multiple, unique risk factors—including social determinants of health—when identifying opportunities to employ prevention and intervention efforts at community levels and to collect specific, context-rich, local data. There are many studies of cultural strengths, wellness, and resilience among Indigenous youth (Brendtro et al., 2005; Brokenleg, 2005, 2012; Chandler & Lalonde, 2008; Hatala et al., 2017; Kirmayer, 2014; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Liebenberg et al., 2015; Njeze et al., 2020; Shaffer et al., 1996; Wexler, 2014; Wexler et al., 2009). Our work builds upon this foundation by examining these themes through the lens of one community’s experience. The variation in suicide rates across indigenous communities and the persistently high rates in this specific community warrant deeper investigation into the perceived risk and protective factors within this specific community.

Youth with suicidal ideation frequently report friendship problems, social isolation, conflict with romantic partners, peer stressors, and victimization from peers as antecedents to suicidal behavior (Bearman & Moody, 2004; Davies & Cunningham, 1999; Hawton et al., 1996; Pavkov et al., 2010). We also know that suicide clusters are common among youth in schools or small communities. Youth in suicide clusters often knew each other before the suicides occurred (Bechtold, 1988; M. Cwik et al., 2015; Wissow et al., 2001). For example, evaluation of one cluster in the participating community—a southwestern NA reservation—found the youth were socially connected, and 50% had alcohol in their bloodstream at the time of death (and presumably had recently been using alcohol with peers) but lacked other known risk factors (Wissow et al., 2001). Although interpersonal factors often precipitate suicidal behavior and play a key role in suicide clusters, the effects of social influences at the level of larger community networks are not well studied in suicide research (Neeleman, 2002). Therefore, where risk factors often coincide with interpersonal conflict within NA communities, there is an important distinction to be recognized regarding the protective function of cultural identity, cultural continuity, engagement in traditional activities and spirituality, often referred to as cultural connectedness (Gray & Cote, 2019; Snowshoe et al., 2017). Connection to culture, spirituality, land, and traditional lifeways is particularly important in Native communities in helping to ameliorate the impact of social determinants of health and combat enduring impacts of historical loss or intergenerational trauma (Gone & Trimble, 2012; Gray & Cote, 2019). Finally, cultural connectedness and engagement in traditional lifeways are rooted in relational concepts of being and existence, as well as healing and well-being, reflecting the importance of Indigenous worldviews and culture in examining the impact of risk or conflict while also attending to strengths and resilience (Collins et al., 2017; Goodkind et al., 2015).

The southwestern reservation-based community participating in this study has fewer than 20,000 enrolled members, many of whom live nearby one another in localized areas on the reservation; thus, suicidal behavior in this community can be both geographically and socially proximal. Prior research found that more than half of NA youth who had engaged in suicidal behavior had exposure to a close other, such as an intimate partner, friend, or immediate family member who had recently engaged in suicidal behavior (M. Cwik et al., 2015). Fifteen percent of NA youth in this same community who engaged in suicidal behavior report that the exposure to another person’s suicide was a precipitating factor of their suicidal behavior (Mullany et al., 2009). These local findings are congruent with national data on Native youth, such as a recent study of the National Violence Death Reporting System that found Native youth who died by suicide had significantly higher odds of a suicide of a friend or family member affecting their death.

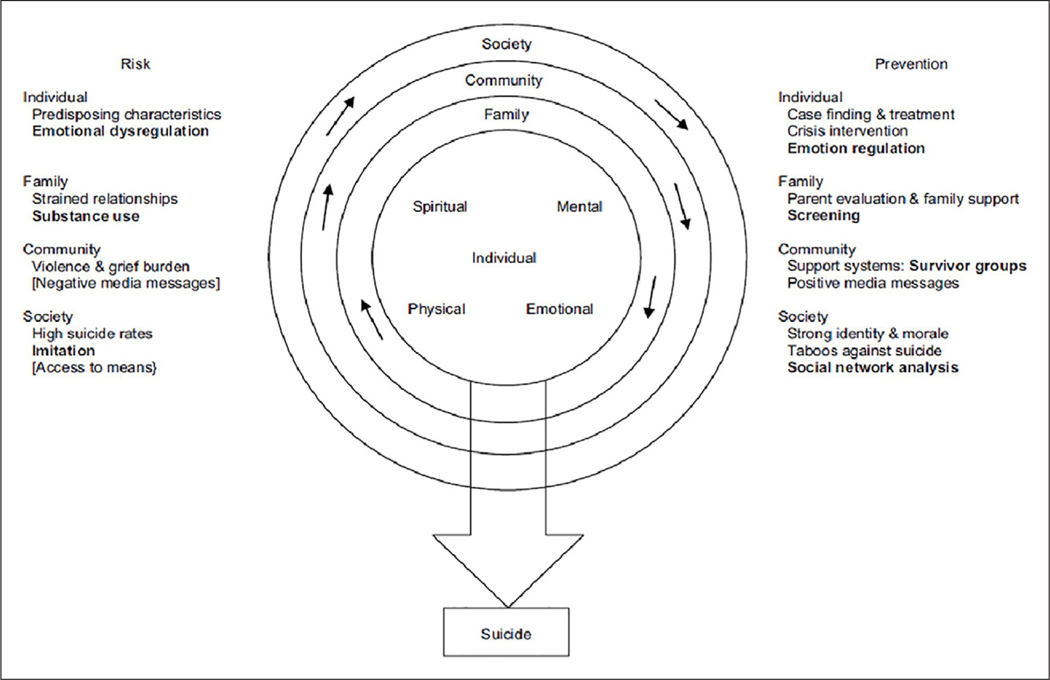

The body of quantitative and qualitative research from this southwestern community on NA youth suicide has contributed to a Native-specific and community-based conceptual model of suicide risk (Figure 1). The model features four categories of potential risk and prevention factors—individual, family, community, and society—that affect youth suicide. Various themes and constructs are listed under each level. The model was constructed based on mixed-methods data from the participating community, including cross-sectional data on risk and protective factors (M. Cwik et al., 2015) and qualitative data from NA youth on their perceptions (Tingey et al., 2014). The purpose of this model is to guide prevention efforts and intervention designs in this community that may also be able to inform other NA populations with similar health disparities and strengths. Interventions designed around this model and implemented in the southwestern community have resulted in a 38% decrease in suicide deaths (Cwik et al., 2016); however, youth suicide rates in the community remain high (13 times higher than the national rate and 25 times higher than the rate targeted by the Healthy People 2020 objective).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of Native American youth suicide.

This conceptual model was developed with the intention to continually refine it as we learn more about the risk and protective factors influencing NA youth suicide in this community through further quantitative analysis and by gathering local knowledge and perceptions. The current form of the model primarily accounts for factors at specific levels (Tingey et al., 2014). Given that prior research also points to the potential salience of group norms and related social influences in driving youth suicide (Brendtro et al., 2005; Brokenleg, 2005, 2012; Chandler & Lalonde, 2008; Hatala et al., 2017; Kirmayer, 2014; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Liebenberg et al., 2015; Njeze et al., 2020; Shaffer et al., 1996; Wexler, 2014; Wexler et al., 2009), there is a need for an increased understanding of these factors and how they are perceived to transcend or influence factors at the specific levels of the model. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to further inform the model by contributing local perspectives about the broad social influences that may contribute to NA youth suicide in this specific context. Improved understanding of such influences from the community perspective may yield new insights and hypotheses about NA youth suicide in this and potentially other communities and thereby generate new opportunities for confirmatory quantitative analysis, as well as potential intervention and prevention targets (Bantjes & Swartz, 2020).

Method

Community-Based Participatory Research Approach

This qualitative study is built on a long-standing partnership between the local Native community and an academic center, whose mission is to work with Native communities to “improve the health status, self-sufficiency, and health leadership of Native people.” This study was developed through a Community-Based Participatory Research Approach (CBPR) process with Native and non-Native researchers, community leaders, members of an Elders Council, key stakeholders, and a Community Advisory Board involved in defining the study population, developing topics for exploration, designating the data collection methods, interpreting findings, and disseminating results. Acknowledging a history of exploitation of Indigenous communities vis-à-vis health research approaches and methodologies, CBPR provides an important and necessary opportunity to collaborate with tribal communities in support of local efforts to deploy health interventions. Furthermore, in keeping with prevailing standards of CBPR and community-based approaches, principles of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession of both data and methodological process become especially critical when undergoing health research on suicide within Indigenous communities. Therefore, centering efforts and resources within the community-based conceptualization of suicide, sequelae, and related phenomena represents an ethical imperative, particularly in this study (Mashford-Pringle & Pavagadhi, 2020).

The authors of this study work in the fields of suicidology and mental health research and have diverse Native (J.I., K.H., and N.G.) as well as non-Native (M.C., B.D., and A.M.) backgrounds. Authors KH, JI, MC, and AM have previously worked in this local Native community as well as in other Native communities in the United States and Canada (ranging from 5 to 20 years); author N.G. has worked for the academic center for more than 20 years and—as a member and resident of the local community—is a liaison to the local Tribal Council. This was author B.D.’s first study based in a Native community. The authors have clinical (K.H., M.C., and N.G.) and public health (A.M., B.D., J.I., K.H., M.C., and N.G.) training or professional experience. Recognizing the potential influences of our own cultural and professional orientations and in keeping with the CBPR approach, we sought contributions from a wide range of stakeholders and gave equal consideration for all views expressed. We approached this study not on behalf of the local community but as collaborators in knowledge production to address the problem of youth suicide in the community

The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB), local Tribal Council, and Health Advisory Board approved the study. The local Tribal Council and Health Advisory Board approved this article.

Community and Sample

The participating community has less than 20,000 enrolled tribal members and is geographically isolated, spanning over a million acres with a spectrum of traditional and mainstream cultures. We utilized convenience and snowball sampling to recruit N = 32 participants through referrals from community partners, the Community Advisory Board, the Tribal Council, and the Health Board. We emphasized referrals from the following groups: young adults, Elders, and local health professionals. A study research assistant contacted the potential participant to assess their willingness to participate, verified eligibility, and scheduled an initial meeting to go over the study purpose, procedures, and informed consent. Given the exploratory nature of this research, inclusion criteria were broad: aged 18+ and either working/residing on the Southwestern reservation or being from the participating tribe. With respect to demographics, both youth and Elder roundtable comprised Native community members from this Southwest Tribal community, whereas community stakeholders represented a diverse group of community members, Native and non-Native, who work in professional settings with the Tribal community, for example, social service agencies, hospital, and schools.

Data Collection

Between March and May 2015, we collected data from four roundtables (i.e., focus groups; young adults: n = 2; professionals: n = 1; and Elders: n = 1), each lasting 60 to 90 minutes. Roundtable discussions were held in a meeting space at the local research offices or community centers on the tribe’s lands. Each roundtable comprised 6 to 11 participants as well as one facilitator and one notetaker. Participants were provided a meal as compensation for their time. All roundtables were recorded using a hand-held digital audio recorder. The young adults’ and professionals’ roundtables were conducted in English, and the Elders’ roundtable was conducted in both English and the local Native language. The recordings in the local language were transcribed after data collection by two NA study team members, and the deidentified recordings in English were sent to a transcription service.

A semi-structured interview guide was used to ensure coverage of the same central topics across groups (see Supplemental Materials). Native and non-Native members of the research team and tribal community collaborated to create the interview guide, which emphasized experiential and generative questions—that is, nondirective questions designed to encourage discussion and the sharing of stories and perspectives. Native community partners on the project ensured the guide was culturally relevant and appropriate in language and tone. The guide contained 11 general questions with one to three probes per question (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) about specific influences on youth suicide across different levels of the social ecology. We asked about (a) individual factors (e.g., emotional state, spirituality, and personal beliefs about suicide); (b) interpersonal factors (e.g., relationships with parents and friends); (c) institutional factors (e.g., the role of schools); and (d) broad societal factors (e.g., mass media, contagion, and intergenerational transfers of cultural knowledge). In the latter portion of each roundtable, facilitators asked participants to identify and share about other influences they perceived to be important but had not yet been mentioned during the discussion.

Data Management and Quality Assurance

We labeled study audio recordings, interview transcripts, and files with unique participant IDs and removed identifying information from transcripts. All computers were password-protected, and copies of interviews were stored in locked cabinets accessible only by the study team. We took several steps to ensure the quality of data and participants’ confidentiality. Before data collection, research assistants received a day-long training in qualitative data collection, including a didactic portion with slides and handouts as well as practice (e.g., role-playing) conducting roundtables. A masters-level study team member with extensive qualitative experience led the training. The study team held weekly conference calls to discuss study progress and provide additional training and supervision for research assistants as needed.

Data Analysis

We took an iterative analysis approach. We developed our codes and understanding of the data by alternating between emic readings of the transcripts and descriptions of the local conceptual model. Following Srivastava and Hopwood (Srivastava & Hopwood, 2009; Tingey et al., 2014), we used a reflexive process, wherein each transcript was visited on multiple occasions and connected to emerging insights from repeated contact with the data over time. Our aim in taking this analytic approach—as opposed to a strictly directive approach—was to develop new ideas and meanings to enhance our understanding of suicide in this Southwestern community, in particular, social influences.

One analyst did a preliminary thematic analysis of the transcripts and presented the preliminary findings to the tribal community to get their initial feedback. Subsequently, between November 2016 and April 2017, two analysts carried out the main analysis, with periodic consultation from the co-authors and key informants from the community. The analysis process began with a data immersion phase, wherein the analysts read each transcript twice. The analysts then read the data a third time, independently generating initial descriptive codes through a primary cycle of coding (Saldaña, 2015). Coding was done lineby-line. The same statement could have multiple codes (Mohatt et al., 2004). The analysts met to review their codes, note overlap and distinctions, and record all the codes in an initial codebook, which was formatted as a matrix and included key codes, abbreviated and detailed code descriptions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the analysts’ documentation of coding decisions. The analysts jointly reviewed the transcript text on which codes were based to ensure fit with the data. Duplicative codes were collapsed, and ambiguous codes were clarified or dropped. This process of primary-cycle, descriptive coding was repeated, allowing coding to be as inclusive as possible until additional readings produced no new codes and coding definitions and inclusion/exclusion criteria were clear. An example of a descriptive code is “bullying.” The analysts then began a similar iterative process of secondary-cycle coding to organize and synthesize the descriptive codes into thematic concepts, which included—for the purpose of this study—determining which, if any, codes were related to social influences. The final codebook incorporated 32 descriptive codes, and we identified seven of these as social influences.

We relied on constant comparative procedures and team review and consensus to arrive at the final list (Gibbs, 2007; Glaser, 1965; Thorne, 2000).

We took several steps to maintain the validity of the data, including team-based analysis of all transcripts and the use of in vivo codes whenever possible to ensure concepts stayed as close as possible to the participants’ own words. The team periodically reviewed all codes and the coding system to identify problems and discrepancies. The team discussed any instances in which the analysts differentially coded the same statements; all resolutions were made by consensus.

Results were triangulated and compared across roundtables (Patton, 1999), and local NA experts reviewed the codes and themes to strengthen the integrity of the findings.

Results

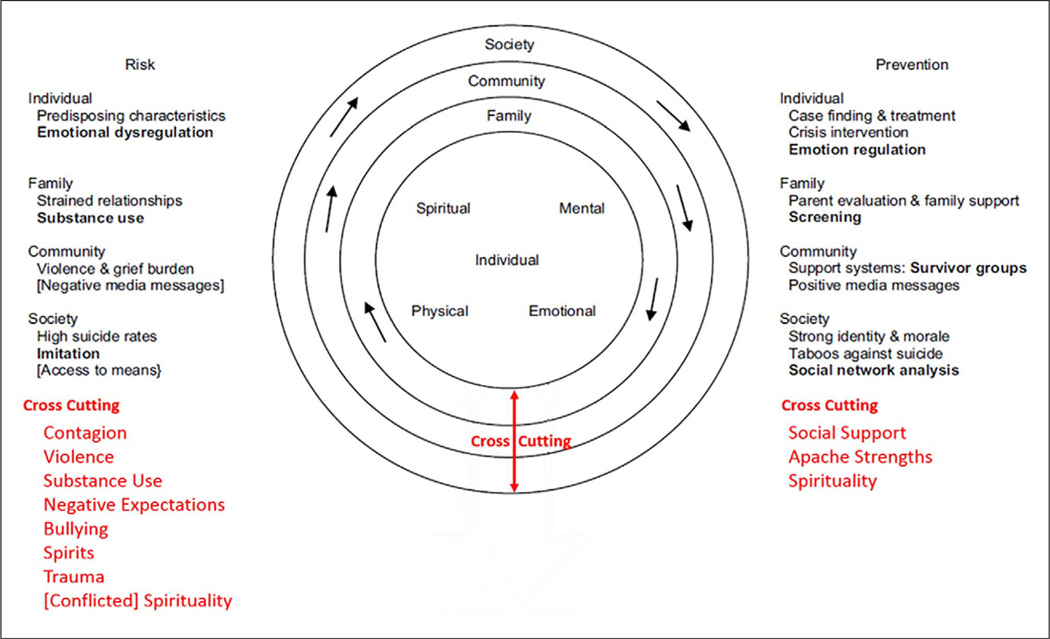

This study was conducted with a sample of N = 32 participants (75% female), all of whom were local stake-holders, the majority of whom were Native (others had experience working and/or living in the participating community). Participants included youth, clinical providers, Elders, parent advocates, and representatives of local agencies in frequent contact with youth who have engaged in the spectrum of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Participants may or may not have personally engaged in suicidal behavior; however, due to the high rates of suicide in the participating community, most individuals have had someone close to them (e.g., friend, family, and intimate partner) engage in suicidal thoughts or behaviors, or die from suicide. Furthermore, due to the size of the community and the cultural importance of youth wellbeing as a source of continuity, this community is particularly sensitive to any youth suicide. Finally, it is important to recognize that this study and the associated data collection have followed the implementation of comprehensive surveillance programming across the reservation community (M. F. Cwik et al., 2014). The roundtable results are presented as a descriptive summary organized by social influences that cut across the four risk and prevention categories of the model (i.e., individual, family, community, and society). The social influences were contagion, violence and abuse, bullying, negative expectations, spirituality, social support, and cultural strengths (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Revised conceptual model of Native American youth suicide.

Social Influences

Contagion.

We defined contagion as the direct influence of hearing about, observing, or knowing firsthand about suicide (including others’ reactions to these events). Participants described several perceived mechanisms for contagion within the community, including suicide deaths of family members or friends, imitating observed behavior for attention, and suicide pacts or games.

Proximity to suicide deaths, especially familial.

Participants used the phrase “jumps from person to person” to describe the contagion of suicidal behaviors. Some also described how frequent exposure to suicide could change one’s perception of suicide, making it an available coping strategy or solution for painful experiences:

I think whether it is close to them or not, in their family or not, it is prevalent enough in the community that it plays a significant influence like it becomes an option. It is something that they see as either a way out or a way to get back at somebody. It is something that they probably, if they had not learned that, would not have normally thought that themselves . . . they think oh, that is something that I can do if I feel that way. (Professional)

Attention-seeking.

Participants discussed how they felt that youth are affected by observing how others threaten or engage in suicidal behaviors to gain attention. We found, however, this effort at attention-seeking does not necessarily belie a real risk of suicide. An unmet need to belong could be lethal, as one youth observed:

My little cousin was saying “oh when so and so killed themselves. They were finally considered a family member at the awake. At the funeral, they finally had a family.” When they were alive no one bothered to. No one gave them the time of day. But it took them having to kill themselves for them to finally have family, relatives, relationships? And so she said I want that too. (Young adult)

We found attention-seeking is not limited to suicidal behavior but also occurs in the context of other behaviors that are associated with suicide among NA youth, such as drug and alcohol use. One young adult observed that “Kids are getting this idea that oh so and so did it, and they called all this attention, so let me go ahead and give it a try too.” Members of the professionals’ roundtable attributed attention-seeking online to a potentially contagious type of attention-seeking, as youth were often looking for—and sometimes getting—reassurance that people (e.g., peers and parents) care about them. While the platform for online sharing may vary (e.g., Facebook and Twitter), professionals observed that the content of a youth’s online comments or posts might not align with how a youth presents themselves “off-line,” highlighting the potential incongruence between virtual and off-line behaviors. For these reasons, professionals identified attention-seeking behavior online as a potential risk factor for NA youth suicide.

Pacts or games.

Others described a specific type of peer pressure involving high-risk and suicidal behaviors in the context of a “game” or “pact” that could be planned days or weeks in advance by youth and, as described during the professionals’ roundtable, sometimes involved suggestive behavior (“be gay day” and “go after older men day”) or drug use in a group setting:

Kids are doing things together, either taking a whole bunch of pills together and some of them I don’t think understand that concept, that if you take all these pills there is a possibility that you can die, because their friends are doing it. (Professional)

Although one professional felt making these types of pacts is a trend among current youth, others recalled pact-making behavior occurring in prior generations of youth, suggesting these behaviors persist across generations, perhaps surreptitiously.

Violence and abuse.

During all the roundtables, violence and abuse were mentioned as believed to be influencing suicidal ideation and behavior among local NA youth. “Violence and abuse” reflect participants’ frequent mention of interpersonal forms of violence and abuse, including physical violence, familial physical/verbal abuse, neglect, and controlling behaviors by youth’s close others, including parents, friends, and intimate partners. This category did not include other forms of violence, such as historical violence, bullying, or racism.

Unhealthy intimate relationships.

Participants noted that many youths have intimate partner relationships and described how emotional manipulation and the dissolution of these relationships can lead to suicidal ideation. The adults perceived the youth as unprepared to manage such relationships and regulate their emotions concerning dating and break-ups:

Kids are getting into really serious relationships when they are really young, you know they’re emotion-based and really into that relationship, but they don’t know what to do with it. (Professional)

Relationships have a heightened sense of dependency, I think in youth, especially with boyfriends and girlfriends, I think even more with family dysfunction . . .when the kids get to the point where, if that person doesn’t want me then I will die, that heightened dependency in any relationship really correlates with the suicide rates. (Professional)

Physical and verbal abuse within families.

Some participants told personal stories wherein they attributed their suicidal behaviors to physical and verbal abuse in their homes. Physical violence appeared to be fueled by substance use. “My mom does get violent when she comes home drunk . . . every time she comes home drunk, my little brother and I would have to clean up, and the way I dealt with it was by cutting myself” (young adult). Verbal abuse was described as depleting youth’s self-esteem: “When she is drunk she would say like ‘you’re a mistake’ or something, and I just feel like I wasn’t good enough.” Children’s self-esteem and mental health seemed to be heavily influenced by the messages they heard from loved ones:

Your mouth is a very powerful weapon, you have to be very selective about the words that you use, especially nowadays because these kids are really, really emotional, I mean, being told “grow a spine” . . . “this isn’t how we used to do it back when I was young, we had to do it like this and like that, and you’re just spoiled,” I mean, when a child hears that, quite often enough, they just start building this low self-esteem of themselves. (Professional)

Parentified children.

Parental absence and accompanying neglect, whether it be due to substance use or for employment, were perceived as frequently resulting in older children feeling obliged to take on parenting duties for younger siblings:

My mom would be out and she would be at the casino, or she would be out drunk and I would have to come home, and I would have to take care of my siblings. I would have to make sure they were fed and they were taken care of—that my brother had his homework done, sister had her homework done, and so I think all of that stress, I’m like I’m too young you know thinking back, I’m too young to have been dealing with all of that stuff, and when I moved away my sister assumed that responsibility, and so she dropped out of high school to take care of my siblings. (Young adult)

Discrimination and bullying.

Many study participants mentioned problems of discrimination and bullying in this Southwestern tribal community. Due to the distinct features of these problems and the frequency with which participants emphasized them, in our analysis we retained “discrimination and bullying” as a separate category. Youth participants described aggressive and racially charged bullying in particular. One youth described the name-calling he endured:

They would just like call me like “the nigger” or . . . “the burnt bread” or things like that . . . . I reported it to teachers and counselors but was told “Oh, it’s okay, they’re fine. You know it’s high school. Deal with it.” (Young adult)

Participants’ comments on discrimination and bullying suggest these problems are not limited to a certain venue but rather occur in numerous settings—in person and online—where youth spend their time or socialize. For example, one young adult shared her experience of bullying at a sporting event:

I was walking towards the locker rooms at halftime, they’d be like She’s too good for the “rez” [reservation]. They said so many hurtful things . . . . People used to spit on us . . . . People would like throw stuff at me, and I was just like, how can my own people talk about me or how can they put down a child when all they want to do is just play basketball. (Young adult)

Young adults comments’ highlighted the salience of technology to the problem of bullying in virtual locations and noted how online disinhibition escalates bullying:

Nowadays you’re bullied 24/7 because social media is available. Whereas before we were all picked on and bullied and jumped at school, but nowadays we are at home on Facebook and called fat on Facebook, you’re called ugly. (Young adult)

You know, you’re saying, “kill yourself,” you know, nobody says that in the real world, but on the Internet they’re saying such hard things. (Young adult)

Similar to the finding that discrimination and bullying were not limited to certain venues, we also found that these behaviors were also not limited to youth. While some participants noted that teachers can be a resource or positive influence on youth, other participants observed that bullying by some teachers contributes to the problem locally:

I had an English teacher, and she said “You’re just an uneducated Indian” and I was the only Native girl in the school, and we only had like 3 black kids and then the rest were white and then several were Mexican . . . I went to the office, and like that hurt me. (Young adult)

Discrimination and bullying may also precipitate suicidal behavior among NA youth. As one Elder’s story conveys, the bullying of one boy led to an attempted suicide:

It happened because they were laughing about [him], they were calling [him] a faggot. I guess he was gay, and they were making fun of him. And then that’s when I told him there is nothing wrong with that, and that is how you were born. He attempted, as you know. He called me from [city name] and I [asked] him, “Why are you doing this? So you are going to go to hell if you kill yourself, you are not going to heaven.” And he said it was for that reason, and I told him, “That it is okay. Because God made you the way you are and who you are. Accept yourself, and love yourself. Nobody loves you but you, yourself have to do it, you are not in pain being that way. It’s just God made you that way, so accept yourself and continue.” I told him to come back, and to this day he is back and he is working good. I spoke in the right way, and after that he had said that: “That person spoke to me real good and that’s why to this day I am still here and that’s what he said.” (Elder)

Negative expectations.

A large proportion of the roundtables was spent discussing negative expectations of others or “negativity,” referring to undesirable attitudes or behaviors that the participants felt in the community. Participants perceived that youth themselves may exhibit negativity but also said that these attitudes or behaviors could be “learned” by observing the behavior of adults in one’s family, as well as of adults in the broader community:

As a community, and even as a tribe, we have this, I don’t want to say toxic, this mindset, we seem to dwell on the bad, we seem to be pessimistic, we seem to love when someone is down. It’s like this poison mindset. Not everyone has it, but I’ve noticed it coming, living on the reservation, then living off the reservation, then coming back. (Young adult)

Other young adults shared this perception, stating “our community needs to stop being so negative . . and be more positive,” and “I think that if our community ever knew this positivity [referring to some adults who “cheer for” and set positive expectations of youth], then they [the community] could really bring out a young person with a smile on their face at the end of the day.” Another young adult conveyed his perception that negative expectations of others were pervasive in the community:

It affects everything we do, everything we say . . . We can never be happy for so-and-so because they got their degree. We can never be happy for so-and-so because they’re sober for a month. If someone is sober for a month, we’re like, “Oh, they’re going to fall, next week, next week, I can guarantee it by next week, Friday, they’re going to be at the casino drunk or they’re going to be staggering.” We can’t, we don’t seem to celebrate the successes. We don’t seem to celebrate the happiness of other people, we only look for them to fall, to fail, to be hurt. I think it’s because we’re all hurting. We just don’t know how to communicate it. We just don’t know how to deal with it . . . It affects every single one of us, indirectly or directly, whether we’re perpetrating this toxic mindset or we’re feeling the ramifications of it, whether someone’s talking about us, whether we’re being cut down or whether we see someone else drunk, whether we see someone else being hurt, we all feel it. (Young adult)

Participants described how the negativity can hold youth back from reaching their full potential:

There are some kids who haven’t heard the word—that you’re . . . loved, or haven’t been given a hug, and just doing that to one child makes a big difference, letting them know not to set themselves at a low level and see themselves coming back to the reservation and having to do something here, but to encourage them to fly higher and have bigger goals and bigger dreams. I think that’s what the kids need to hear these days, because a lot of kids, they’re used to all this negativity around us they just feel that . . .they don’t have too far to go, too far to aim for. In actuality, we take off all the blinds from them, and they can soar, and they just don’t realize that. (Professional)

Although these and other participants’ comments emphasized the problem of negativity, participants also pointed out that the problem is mutable. For example, a young adult suggested the community could “teach” positivity and that “the community needs to stick up for the community.” In the Elder roundtable, participants noted that schools can be a venue for encouraging positivity:

Every time I go to the classroom, what I aim for is that self-esteem. That is what I aim for, every time I go, my first unit is . . . self-esteem. How to love yourself, love yourself first, before you love somebody. That’s what I do first, I open with that when I am going to speak. So that’s why. Because we have a high rate of suicide here on the reservation. (Elder)

Spirituality

Spirituality and religion.

Many participants across the roundtables discussed spirituality and religion dually as a potential protective factor against suicidal behavior as well as a potential stressor. Some participants described finding support in church groups as well as in scripture and prayer, as one young adult’s account illustrates:

Like do you think the Creator would bring us here for a purpose, he had the desire to make me, if he had the desire to make me something other than [specific tribe] then he would have made me so in the first place but he put in my heart and desire to be here apart of this bloodline and my religion is just to help me live a better life with keeping commandments or just having a closer relationship to my heavenly father, but spiritually I felt the presence of all the hardships we have as Native American people really helped me . . . (Young adult)

However, not all individuals found support in spirituality or followed a single belief system. Participants noted that youth may struggle with this aspect of their life and—as they age—may even transition between following a Western religion (e.g., Christianity) and following traditional tribal beliefs:

Young girls participate in sunrise dances, but as they get older they turn to religion. They go back and forth between and don’t know what’s right and wrong. (Young adult)

Another young adult participant echoed this ideological conflict:

Being Indigenous people we have a bunch of bigger factors, and I think, um, like religion, it’s confusing here, what’s right what’s wrong. I think if I die where do I go? You know, that’s a scary thing. Am I living the right way, or am I living the wrong way? There is a lot of judgment on both sides of the religion, the traditional and then there are a lot of different religions here too. I think there is a lot of different pressures kids are going through . . . affecting the kids in a negative way. (Young adult)

Spirits.

Participants across the roundtable groups shared personal stories about their beliefs that spirits contributed to their own or a close relative’s suicidal ideation or behavior. “I personally believe that suicide is a spirit” (young adult). Some participants described spirits as a feeling or a shadow, while others described interactions with the spirits (e.g., seeing the spirit as a person standing next to them, hearing it tell them to hurt themselves, and sometimes having physical altercations with it). Although some study participants attributed these experiences to drug use, others recalled vivid encounters with spirits during childhood and in the absence of drug use. A mental health professional commented on the challenge of addressing this issue:

I know that some people who have experienced suicide very close, either they walked in, or saw it, or anything like that, they have reported feeling people, feeling like a dark spirit next to them. I don’t know how far that goes, how much that affects them, I know I hear about it and I, umm, I can’t imagine what they experience. And they’ll not just see it, but hear it, hear it speaking to them, and that’s very powerful. It’s something that I wouldn’t know how to handle. (Professional)

Participants mentioned a local taboo about speaking of suicide and how this is thought to be a mechanism for spirits to move from person to person, thereby spreading suicidal behaviors. There is a belief that some Elders know which people are at risk and can help them by praying for them. One person explained, “There’s people who are out there who have already been shown which life is going to be taken by suicide. That person doesn’t say anything, but that person goes into prayer for this child, that child, that older adult.” As this quote illustrates, several participants observed that spirituality may be a resource for addressing the concern of spirits as contributing to suicidal ideation or behavior among youth.

Social support.

Youth and professionals alike described the importance of a strong social support network as a potential protective factor against suicide. A number of sources of social support were identified during the roundtables, including family, friends/peers, church, or spiritual group. One young adult participant described how her family and people at her church, in particular, rallied around her while she was being bullied:

When it came to other people that came to my defense, I just thought there are so many people that care about me. Why should I do something petty over one person, why should I give that one person pleasure? (Young adult)

Elders, professionals, and young adult participants all emphasized letting youth know that they are important, loved, and supported:

See, our life is precious. Because it was not a mistake that I was born. Because it’s not a mistake that I am here, and that is what they are thinking also. But one thing, love your kids. Love them, hug them every morning, and pray with them. (Elder)

I think just having someone who cares for them at home, and isn’t abusing drugs and alcohol, but is actually there, present, mentally and physically for the child. I think that helps. (Professional)

If there is no food at home, they’re going to go somewhere where there is food. If there is no support at home, then they will seek support elsewhere . . . whether it’s in gangs, or whether it’s at a church group . . . they’ll seek that sense of belonging elsewhere. (Young adult)

Elder roundtable participants shared their perspective on the importance of providing moral guidance for youth experiencing or acting on suicidal thoughts:

The ones [people] that taught about morals in the old days . . . Someone who thinks of you in a good way, like your god-family. When you hang out with them, they watch over you. Your true friend, your good friend, or your god-family. They are the ones that’s not going to push you to do wrong. They are the ones that are like your guardian angels, in a sense. (Elder)

In instances when a suicidal youth may reject such moral guidance, Elders reflected on how they had turned to prayer as an alternative way of providing support. As one Elder commented in regard to a suicidal young adult they knew who would not heed the Elder’s guidance, “ . . . all you can do is pray for them, that’s the only way. Just put it all in God’s hands.”

Cultural strengths.

Many participants identified the potential role of their tribal culture in protecting youth from suicidal behaviors. Elders perceived how influential early childhood can be in protecting youth from suicidal behaviors as they grow older:

When we were children, when we’re in the cradleboard, the kids don’t talk yet, but when they begin to see, they focus on everything that is going on. That’s part of their learning time. Up until six years old, and they pick up a lot. That’s a fast learning time . . . So, when the children are there, for that reason you should watch how you talk. From there, the morals that you were taught, that is what you should be like, which is good . . . When they begin to talk, they’ll learn the words that you use . . . It’s good to talk to them whenever. In front of them, about family behavior, be careful of your behavior . . . That is a precious life, from the day you were born, until the day you pass on. All those years, and that is how you learn. (Elder)

Elders also stressed the importance of ensuring youth hear and speak their tribe’s language as their first language and begin learning their specific tribe’s traditions and way of life from birth. Young adults also talked about engaging youth in learning their Native culture, specifically history, language, and traditional clothing:

That’s why I say culture because to me, culture is our language. It’s the camp dresses, the burden baskets. That’s why I try to differentiate between culture and tradition. Tradition to me is the sunrise dance. I grew up in a family where that was all bad. That’s me personally, because I grew up in a family where that was all bad and church was all good. Trying to be sensitive to both sides and say “culture.” They can learn how to create a camp dress. They can learn how to make moccasins. They could learn the clan system. Learn the names of the mountains in [tribe’s language]. “River” in [tribe’s language]. “Animals” in [tribe’s language]. They could sing Christian songs in [tribe’s language]. I just think we need to have some sort of cultural awareness, some sort of [name of participating tribe] pride. Doesn’t have to be sunrise dances. Doesn’t have to be church. Elders come in. There’s Storytelling. I just think some sort of culture awareness. (Young adult)

Young adult participants noted the benefits cultural engagement could have for the youth and offered some specific ideas as to how it could be achieved:

Restoring some sense of pride in themselves, restoring pride to our people. For me personally, I can see Elders playing a big role in that . . . They have such a wealth of information but no one ever utilizes them because they’re too old or they don’t know it. I guess I’m thinking of the concept “(word in tribe’s language),” don’t know how to explain that in English, but it’s like building them up, I guess, really encouraging them. One of the strengths that we have, as [name of group of similar tribes], as [name of specific tribe] in particular, is our language. Just the language itself conveys such strong emotions. And it’s unfortunate that we’re losing it, but I just think we should do more in that area. And another thing that I think would be so good, so great, so awesome would be a culture camp, a culture enrichment camp. (Young adult)

Participants also noted the importance of embracing Native culture, highlighting that traditionally the participating tribe had a strong family support network:

I think this all goes back to what is like my favorite part of Native culture. Native culture is so relation-based, relational, and you know we see it with our kids. They’re going to take care of each other, and, you know, we have grandparents that are involved, and we have that family culture, and that’s something that like, middle-class White culture doesn’t have as much, and so I think “What is the basis for how this community can decrease suicide is by bettering that family structure.” (Professional)

Discussion

Addressing youth suicide in NA communities—as in all communities—requires careful consideration of the full context of the problem. Using qualitative data from young adults, Elders, and health professionals from a Southwestern tribe in the United States, we aimed to inform an existing, culturally grounded, and community-based conceptual model of Native youth suicide by exploring local perspectives on the influences of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in this population. Specifically, we aimed to elicit influences from community members that transcend individuals and their immediate social networks. In total, our analysis resulted in the identification of seven influences that could not fit singly into the existing categories of potential risk and protective factors in the conceptual model of youth suicide risk: contagion, violence and abuse, discrimination and bullying, negative expectations, spirituality, social support, and tribal cultural strengths. Some key findings are worthy of discussion as they relate to the NA research literature and our group’s prior work with this southwestern tribe.

Contagion has been studied intensively in the field of suicide prevention. Many suicide prevention researchers and practitioners view contagion as the cause of suicide clusters (Haw et al., 2013). A growing body of research from diverse samples reveals these clusters may form through various mechanisms, including imitation, social learning, complicated grief, and normalization (Gould et al., 1990; Tingey et al., 2014). Our findings on contagion among youth from this community generate potential hypotheses about the mechanisms of social learning and imitation in particular. Indeed, our group’s prior qualitative work with this Southwestern tribe highlighted the role of imitation in the context of peer relations (Tingey et al., 2014). The current study suggests, however, that the influence of imitation is viewed locally more broadly, reaching beyond one’s immediate familial and social circles. Based on these perspectives, the current conceptual model should consider contagion has a pervasive effect beyond one’s immediate peer and family relationships. Also, we contend that this hypothesis and that social learning and imitation—are potentially powerful mechanisms contagion in this Southwestern tribe—deserve continued quantitative study. Contagion may relate to social isolation/interconnection, the high rates of NA youth’s exposure to suicidal behavior, and the close affiliations among youth who are most vulnerable to suicidal behaviors.

Although bullying and discrimination are documented risk factors for suicide by young adults in NA and other populations (Assari et al., 2017; Freedenthal & Stiffman, 2004; Hertz et al., 2013; Yoder et al., 2006), our analysis revealed how strongly discrimination and bullying are considered to be intertwined by local stakeholders. Participants described feeling bullied and discriminated against in various settings, including at school, at sporting events, and on social media. Participants indicated that even some teachers engage in bullying behavior and that schools did not address this problem. Participants’ discussions revealed that bullying that starts at school may transition into bullying on social media. Furthermore, while affecting the youth directly, these problems also affect youth’s parents and community Elders. Other authors have discussed marginality having an effect on suicidality for sexual minority women documented with photovoice methods (Creighton et al., 2019). Given bullying and discriminatory behavior occurs across various settings and affects the youth as well as their caretakers, the existing conceptual model could include bullying/discrimination as a joint influence cutting across the risk and protective factor categories in the model.

We were also able to more thoroughly understand local perceptions on spirituality, religion, and traditional values, including the importance of connectedness to their tribal lands. Research from other NA communities has called attention to the importance of these cultural efforts in contributing to lower suicide rates among NA youth (Chandler & Lalonde, 1998; Garroutte et al., 2003; Wexler & Gone, 2012). In our study, youth described positive experiences with both Western religion and traditional beliefs or teachings and perceived that spirituality may be a potential protective factor against youth suicide. This finding is consistent with research from other Native communities showing that spirituality is important to overall health (Peters et al., 2019) and “resilience” (Long & Nelson, 1999) and may be associated with reduced suicide-related outcomes (Garroutte et al., 2003; Peters et al., 2019). However, some participants expressed feeling confusion or external pressure (e.g., judgment from others in the community) to choose between Western religion and traditional beliefs or teachings, and some youth may transition between belief systems as they age.

Youth and adults alike spoke of the benefits of reconnecting youth with the tribal language and land through culture camps, hunting, fishing, and storytelling to convey the cultural significance of their tribal lands. The importance of land and place has been found in other qualitative research examining culturally competent approaches to American Indian healing and well-being (Goodkind et al., 2015). We call attention to the participants’ robust endorsement of spirituality and other cultural efforts as tribal strengths. Participants discussed these strengths as being important not only to individuals but also to families and the tribal community as a whole. For this reason, the conceptual model should consider reflecting the importance of these influences across the social ecology—individual, family, community, and society. We were also able to gain insights into local beliefs surrounding spirits and suicide, something our team has heard about over the years from staff and local stakeholders.

This study had several limitations. First and foremost, we cannot make claims about the causes of suicide or suicidal behavior based on the current data. The model is conceptual rather than causal in nature, and the perceived potential risk and protective factors should be studied further in this community. Narrative accounts or perceptions of nonfatal suicidal behavior are created within a very particular context and influenced by a host of factors including our perceptions and memory processes (Bantjes & Swartz, 2019, 2020). Second, we caution that the experiences of the participants in the study might differ from those who declined participation. Our sample potentially reflected individuals’ perspectives who are more willing to participate in a research study and/or share their experiences in public. Third, due to the sensitive nature of the topic and the risk of identification, we could not examine thematic differences by gender, age, or other sociodemographic factors; accounting for these differences would be an area for future research. The results presented here reflect the local understanding of potential suicide risk and protective factors for one tribal community and may not generalize to other tribal communities. The new social influences identified in this study should be examined and confirmed in future quantitative research in this and other communities. Finally, the use of snowball sampling methods may have biased the sampling process by only providing access to certain portions of the community.

A major strength of this study included extending our group’s previous qualitative work to incorporate the perspectives of professionals and Elders as well as the perspectives of the youth. Furthermore, we had previously solicited the perspectives only of suicidal youth; this study augments the youth perspective on suicide by also including youth from the local community who had not previously engaged in suicidal behavior. The inclusion of multiple viewpoints may serve to illuminate our understanding of Native youth suicide and the critical effort to prevent tragic outcomes.

Conclusion

Although there are similarities to other established models of suicide risk (Brendtro et al., 2005; Brokenleg, 2005, 2012; Chandler & Lalonde, 2008; Hatala et al., 2017; Kirmayer, 2014; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Liebenberg et al., 2015; Njeze et al., 2020; Shaffer et al., 1996; Wexler, 2014; Wexler et al., 2009), this model includes features that are more prevalent in the experience of Native individuals, including the impact of overcrowded households and family composition, significant grief burden due to premature deaths, the stigma surrounding treatment-seeking, and contagion. Our model of NA youth suicide is the first of its kind to be informed by decades of qualitative and quantitative research, including recognizing the importance of giving voice to local stakeholders and community members. This study aimed to address gaps in the research and further develop this model by investigating the perceptions of social influences at the level of larger community networks. A better understanding of the social, cultural, and organizational assets of the community can promote resilience. Intervention development could engage in protective social network factors, such as youth’s family and tribal connectedness consistent with NA traditional values.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The authors disclosed the receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research is supported by the Native American Research Centers for Health for funding this research (U261IHS0093).

Author Biographies

Mary Cwik, PhD, is an Associate Director at the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health, and Associate Scientist in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She was the PI on this research project.

Benjamin Doty, PhD, is a researcher affiliated with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Alexandra Hinton, MPH, is a researcher affiliated with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Novalene Goklish is a member of the White Mountain Apache Tribe and has worked to implement behavioral health programs for over 20 years including suicide prevention for 10+ of those years.

Jerreed D. Ivanich, Ph.D., is a member of the Metlakatla Indian Community and is an Assistant Professor at the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Anschutz. His work meets at the intersection of social network analysis, prevention science, and Indigenous health.

Kyle Hill, PhD (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa/Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate), is a researcher affiliated with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Angelita Lee, member of the White Mountain Apache Tribe of Arizona has been with the Center for 14 years. Ms. Lee has worked on the Celebrating Life Suicide Prevention program, Arrowhead Business Group, Respecting the Circle of Life program, a teen pregnancy prevention program and the Protecting our Future Generation program which is an STI prevention program.

Lauren Tingey, PhD, MPH, MSW, is an Associate Director at the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health, and Associate Scientist in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her research and service portfolio focuses on the development and evaluation of public health interventions to address behavioral health disparities among Native American youth and families.

Mariddie Craig, member of the White Mountain Apache Tribe of Arizona, was the PI of the main grant that funded this project and several others.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr. Please enter the article’s DOI, located at the top right hand corner of this article in the search bar, and click on the file folder icon to view.

References

- Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M, & Caldwell CH (2017). Discrimination increases suicidal ideation in black adolescents regardless of ethnicity and gender. Behavioral Sciences, 74), Article 75. https://doi.org/10/gf44dv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantjes J, & Swartz L (2019). “What can we learn from firstperson narratives?” The case of nonfatal suicidal behavior. Qualitative Health Research, 29(10), 1497–1507. https://doi.org/10/ggk556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantjes J, & Swartz L (2020). The benefits of robust debate about the place of qualitative research in suicide prevention. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 944–946. https://doi.org/10/gg7s73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, & Moody J (2004). Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 94(1), 89–95. 10.2105/AJPH.94.1.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold DW (1988). Cluster suicide in American Indian adolescents. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 1(3), 26–35. https://doi.org/10/cnf29n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendtro LK, Brokenleg M, & Van Bockern S (2005). The circle of courage and positive psychology. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 14, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Brokenleg M (2005). Raising respectful children. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 14, 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brokenleg M (2012). Transforming cultural trauma into resilience. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 21(3), 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, & Lalonde C (2008). Cultural continuity as a moderator of suicide risk among Canada’s first nations. In Kirmayer L & Valaskakis G (Eds.), Healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada (pp. 221–248). University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, & Lalonde C (1998). Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s first nations. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35(2), 191–219. https://doi.org/10/cg5ttz [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Delgado RA, Pringle BA, Roca C, & Phillips A (2017). Suicide prevention in Arctic Indigenous communities. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2), 92–94. https://doi.org/10/gg7s8n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton GM, Oliffe JL, Broom A, Rossnagel E, Ferlatte O, & Darroch F (2019). “I Never Saw a future”: Childhood trauma and suicidality among sexual minority women. Qualitative Health Research, 29(14), 2035–2047. https://doi.org/10/gg7s8r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik M, Barlow A, Tingey L, Goklish N, LarzelereHinton F, Craig M, & Walkup JT (2015). Exploring risk and protective factors with a community sample of American Indian adolescents who attempted suicide. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 19(2), 172–189. 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik MF, Barlow A, Goklish N, Larzelere-Hinton F, Tingey L, Craig M, Lupe R, & Walkup J (2014). Community-based surveillance and case management for suicide prevention: An American Indian tribally initiated system. American Journal of Public Health, 104(Suppl. 3), e18–e23. https://doi.org/10/gg7s8w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik M, Tingey L, Maschino A, Goklish N, LarzelereHinton F, Walkup J, & Barlow A (2016). Decreases in suicide deaths and attempts linked to the white mountain apache suicide surveillance and prevention system, 2001–2012. American Journal of Public Health, 106(12), 2183–2189. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M, & Cunningham G (1999). Adolescent parasuicide in the Foyle area. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 16(1), 9–12. 10.1017/S079096670000495X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freedenthal S, & Stiffman AR (2004). Suicidal behavior in urban American Indian adolescents: A comparison with reservation youth in a southwestern state. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(2), 160–171. 10.1521/suli.34.2.160.32789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte EM, Goldberg J, Beals J, Herrell R, Manson SM, & Team A-S (2003). Spirituality and attempted suicide among American Indians. Social Science & Medicine, 56(7), 1571–1579. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00157-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs G (2007). The nature of qualitative analysis. In Analyzing qualitative data (pp. 1–10). SAGE. 10.4135/9781849208574.n1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. 10.2307/798843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Trimble JE (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 131–160. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Gorman B, Hess JM, Parker DP, & Hough RL (2015). Reconsidering culturally competent approaches to American Indian healing and well-being. Qualitative Health Research, 25(4), 486–499. 10.1177/1049732314551056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Wallenstein S, Kleinman MH, O’Carroll P, & Mercy J (1990). Suicide clusters: An examination of age-specific effects. American Journal of Public Health, 80(2), 211–212. 10.2105/ajph.80.2.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray AP, & Cote W (2019). Cultural connectedness protects mental health against the effect of historical trauma among Anishinabe young adults. Public Health, 176, 77–81. 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatala AR, Bird-Naytowhow K, Pearl T, Judge A, Sjoblom E, & Liebenberg L (2017). “I have strong hope for the future”: Time orientations and resilience among Canadian Indigenous youth. Qualitative Health Research, 27(9), 1330–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haw C, Hawton K, Niedzwiedz C, & Platt S (2013). Suicide clusters: A review of risk factors and mechanisms. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 43(1), 97–108. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Fagg J, & Simkin S (1996). Deliberate self-poisoning and self-injury in children and adolescents under 16 years of age in Oxford, 1976–1993. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 169(2), 202–208. 10.1192/bjp.169.2.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, & Warner M (2020). Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 362, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz MF, Donato I, & Wright J (2013). Bullying and suicide: A public health approach. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(Suppl. 1), S1–S3. https://doi.org/10/gd8ccz [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10/bhp2s9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L (2014). The health and well-being of Indigenous youth. Acta Paediatrica, 104, 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, & Williamson KJ (2011). Rethinking resilience from Indigenous perspectives. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt RA (2018). Suicides among American Indian/Alaska natives—National violent death reporting system, 18 states, 2003–2014. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(8), 237–242. https://doi.org/10/gdh9pz [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebenberg L, Ikeda J, & Wood M (2015). “It’s just part of my culture”: Understanding language and land in the resilience processes of Aboriginal youth. In Theron L, Liebenberg L, & Ungar M (Eds.), Youth resilience and culture: Commonalities and complexities (pp. 105–116). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston R, Daily RS, Guerrero AP, Walkup JT, & Novins DK (2019). No Indians to spare: Depression and suicide in Indigenous American children and youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 28(3), 497–507. https://doi.org/10/gg7tbp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long CR, & Nelson K (1999). Honoring diversity: The reliability, validity, and utility of a scale to measure native American resiliency. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 2(1/2), 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Mashford-Pringle A, & Pavagadhi K (2020). State of the art and science: Using OCAP and IQ as frameworks to address a history of trauma in indigenous health research. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(10), E868–E873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen J, Stachelrodt M, Hensel C, & Fath R (2004). Unheard Alaska: Culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(3–4), 263–273. https://doi.org/10/bwj5tj [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullany B, Barlow A, Goklish N, Larzelere-Hinton F, Cwik M, Craig M, & Walkup JT (2009). Toward understanding suicide among youths: Results From the White Mountain Apache tribally mandated suicide surveillance system, 2001–2006. American Journal of Public Health, 99(10), 1840–1848. https://doi.org/10/dm9×9j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman J (2002). Beyond risk theory: Suicidal behavior in its social and epidemiological context. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 23(3), 114–120. https://doi.org/10/b5sjft [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml

- Njeze C, Bird-Naytowhow K, Pearl T, & Hatala AR (2020). Intersectionality of Resilience: Case study explorations of Indigenous youth resilience and wellness in an urban Canadian context. Qualitative Health Research, 30(13), 2001–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIMH. (2020). Suicide. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml

- Patton MQ (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5Part2), 1189–1208. https://doi.org/10591279 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavkov TW, Travis L, Fox KA, King CB, & Cross TL (2010). Tribal youth victimization and delinquency: Analysis of youth risk behavior surveillance survey data. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(2), 123–134. 10.1037/a0018664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters HJ, Peterson TR, & Dakota Wicohan Community. (2019). Developing an indigenous measure of overall health and well-being: The Wicozani instrument. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 26(2), 96–122. 10.5820/aian.2602.2019.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, & Flory M (1996). Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53(4), 339–348. https://doi.org/10/dbsvmv [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowshoe A, Crooks CV, Tremblay PF, & Hinson RE (2017). Cultural connectedness and its relation to mental wellness for first nations youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 38(1–2), 67–86. https://doi.org/10/f9vj8t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P, & Hopwood N (2009). A practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10/gcd5hh [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (n.d.). Racial and ethnic disparities. https://www.sprc.org/scope/racial-ethnic-disparities

- Thorne S (2000). Data analysis in qualitative research. Evidence-based Nursing, 3, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tingey L, Cwik MF, Goklish N, Larzelere-Hinton F, Lee A, Suttle R, Walkup JT, & Barlow A (2014). Risk pathways for suicide among native American adolescents. Qualitative Health Research, 24(11), 1518–1526. https://doi.org/10/f6m88t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2012). National survey on drug use and health, 2011: Version 1. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NAHDAP/studies/34481

- Wexler LM (2014). Looking across three generations of Alaska natives to explore how culture fosters indigenous resilience. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51, 73–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler LM, DiFluvio G, & Burke T (2009). Resilience and marginalized youth: Making a case for personal and collective meaning-making as part of resilience research in public health. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler LM, & Gone JP (2012). Culturally responsive suicide prevention in indigenous communities: Unexamined assumptions and new possibilities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 800–806. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissow LS, Walkup J, Barlow A, Reid R, & Kane S (2001). Cluster and regional influences on suicide in a Southwestern American Indian tribe. Social Science & Medicine, 53(9), 1115–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, & LaFromboise T (2006). Suicidal ideation among American Indian youths. Archives of Suicide Research, 10(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10/b7jdb5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.