Abstract

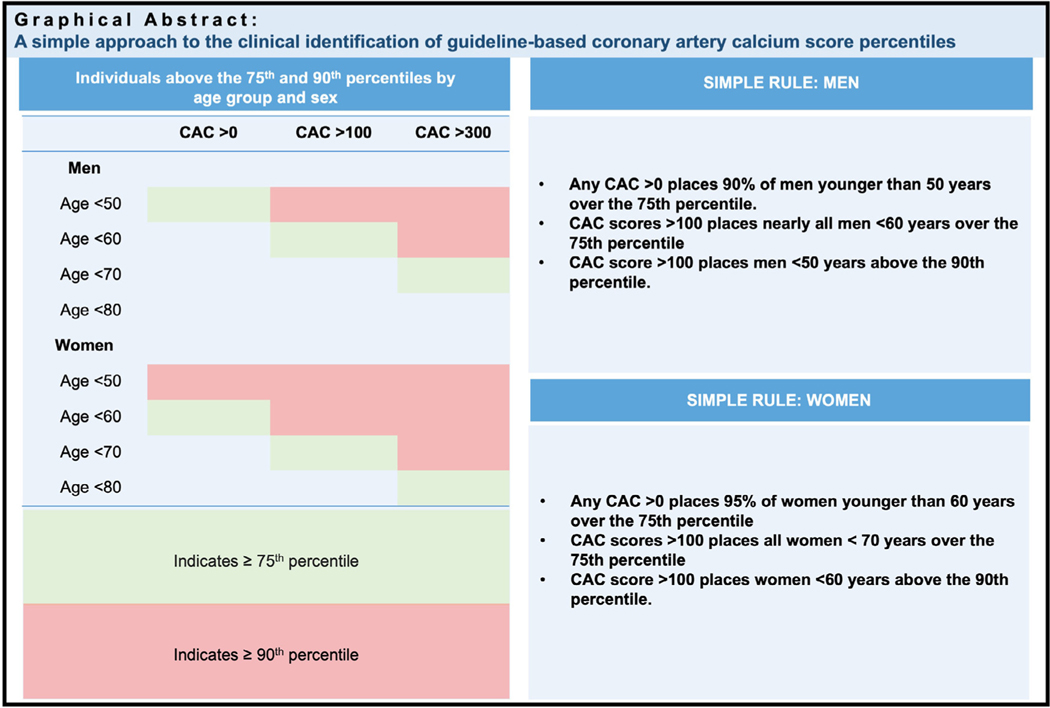

Absolute coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and CAC percentiles can identify different patient groups, which could be confusing in clinical practice. We aimed to create a simple “rule of thumb” for identifying the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association endorsed 75th CAC percentile based on age, gender, and the absolute CAC score. Using the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, we calculated the age and gender-specific percent likelihood that a guideline-based absolute CAC score group (1 to 100, 100 to 300, >300) will place a patient above the 75th percentile. Also, we derived gender-specific age cutoffs by which 95% of participants with any (>0), moderate (≥100), or severe (≥300) CAC score would be over the 75th percentile. We repeated the analysis using the 90th percentile threshold and also conducted sensitivity analyses stratified by race. Any CAC >0 places 95% of women younger than 60 years and over 90% of men younger than 50 years over the 75th percentile. Moderate absolute CAC scores (>100) place nearly all men <60 years and all women <70 years over the 75th percentile. Confirmatory analysis for age cutoffs was consistent with primary analysis, with cutoffs of 48 years for men and 59 years for women indicating a 95% likelihood that any CAC would place patients over the 75th percentile. In conclusion, our study provides a simple rule of thumb (men <50 years and women <60 years with any CAC, men <60 years and women <70 years with CAC >100) for identifying CAC >75th percentile that might be readily adopted in clinical practice.

The 2018 American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol and the 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease assigned coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring a Class IIa recommendation for use as part of a clinician-patient risk discussion to guide preventive pharmacotherapy in patients with “uncertain” risk.1,2 Guidelines commonly use both absolute CAC score and CAC score percentiles in the recommendations for statin therapy initiation. For example, the 2018 and 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend initiating statin therapy for (1) patients with CAC score ≥100 Agatston units; (2) patients ≥55 years with any CAC; and (3) patients with CAC ≥75th percentile for age, gender, and race/ethnicity.1,2 In 2017, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography provided treatment recommendations using absolute CAC thresholds (0, 1 to 99, 100 to 299, and ≥300), recommending a 75th percentile cut point only in the CAC 1 to 99 group.3 Because absolute CAC scores and CAC percentile cutoffs identify different groups of patients; clinicians have expressed some confusion regarding best practice, followed by a call for more clarity and simplicity.4 Specifically, it becomes most important for clinicians to quickly identify young patients who have CAC <100 yet are >75th percentile for their age, gender, and race/ethnicity and thus potential candidates for statin therapy.

Methods

To address this clinical question, we leveraged the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), aiming to create a potential simple “rule of thumb” for identifying the ACC/AHA-endorsed 75th percentile based on age, gender, and the absolute CAC score. Details of MESA study recruitment and CAC scoring have been described previously.5 The study population comprised 6,783 MESA participants with full demographics and baseline CAC score. Participants self-reported their race/ethnicity as African American, Chinese American, Hispanic, or White. All MESA participants provided written informed consent at study entry, and the study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees at each study site. The age and gender-specific CAC score percentiles were calculated according to McClelland et al.6

Our goal was to create, in tabular form, a simple rule-based approach to identifying the 75th percentile by age decile (10-year groups), gender, and the absolute CAC score. To accomplish this, we first calculated the age and gender-specific percent likelihood that a given guideline-based absolute CAC score group (1 to 100, 100 to 300, >300) will place a patient above the 75th percentile. In addition, as a confirmatory analysis, we derived gender-specific age cutoffs by which 95% of participants with any (>0), moderate (≥100), or severe (≥300) CAC score would be over the 75th percentile, checking for agreement between the previously mentioned 2 analyses.

Given the emerging data on using CAC to guide the intensity of therapy at “very high CAC,” defined as >90th percentile, we repeated the analysis substituting this threshold. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses stratified by race.

Results

The results of the primary analysis are listed in Table 1. Any CAC >0 places 95% of women younger than 60 years and over 90% of men younger than 50 years over the 75th percentile. Moderate absolute CAC scores (>100) place nearly all men <60 years and all women <70 years over the 75th percentile. Confirmatory analysis for age cutoffs was consistent with primary analysis, with cutoffs of 48 years for men and 59 years for women indicating a 95% likelihood that any CAC would place patients over the 75th percentile. (Tables 2 and 3)

Table 1.

Percentage of patients above the 75th and 90th percentiles by age group and gender, MESA (2000 to 2002)

| Age group/Sex | Coronary Artery Calcium Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Men | >0 | >100 | >300 |

| Age <50 years | 90% | 100% | 100% |

| Age <60 years | 98% | 100% | |

| Age <70 years | 93% | ||

| Age <80 years | |||

| Women | |||

| Age <50 years | 83% | 100% | 100% |

| Age <60 years | 95% | 100% | 100% |

| Age <70 years | 100% | 100% | |

| Age <80 years | 100% | ||

Italicized: Indicates >75th percentile (number in cells represent the percentage of participants over the 75th percentile).

Bold: Indicates >90th percentile (number in cells represent the percentage of participants over the 90th percentile [100% of participants over the 75th percentile]).

Table 2.

The 95% lower bound cut points of ages by >75th and >90th CAC percentile, CAC group, and gender

| 95% Lower Bound Age Cut Point | CAC 1–100 | CAC 101–300 | CAC >300 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Men | |||

| 75th Percentile | 48* | 63 | 70 |

| 90th Percentile | - | 53 | 63 |

| Women | |||

| 75th Percentile | 59 | 74 | All |

| 90th Percentile | 50 | 63 | 72 |

Interpretation: 95% of men who are above the 75th CAC percentile and have a CAC score of 1 to 100 have an age that falls at 48 or below.

Table 3.

The 95% lower bound cut points of calcium score by >75th and >90th CAC percentile, age, and gender

| 95% Lower Bound CAC Cut Point | Age <50 | Age <60 | Age <70 | Age <80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Men | ||||

| 75th Percentile | 3* | 63 | 373 | 544 |

| 90th Percentile | 48 | 259 | 679 | 1983 |

| Women | ||||

| 75th Percentile | CAC>0 | CAC>0 | 42 | 170 |

| 90th Percentile | 5 | 52 | 219 | 543 |

Interpretation: 95% of men who are above the 75th CAC percentile and are aged < 50 years have a CAC score that falls above 3.

The absolute CAC score indicating the 90th percentile for each age group is generally one CAC category higher than the absolute CAC score placing patients above the 75th percentile. For example, in men <50 years and women <60 years, a moderate absolute CAC score >100 is required to place patients above the 90th percentile (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CAC scores and corresponding percentiles by age group and gender

The primary pattern that emerged can be summarized as follows. First, beginning at age 50 years in men and age 60 years in women, for each 10-year increase in age group (i.e., <50 to <60 years), one group increase in absolute CAC score category (i.e., from mild >0 to moderate >100 or moderate >100 to severe >300) is needed to identify patients above the 75th percentile. For example, men <50, <60, and <70 years old are extremely likely to be over the 75th percentile if they have mild, moderate, and severe CAC scores, respectively (<100, 100 to 300, >300).

Second, all women and nearly all men <70 years old with CAC scores >300 are above the 75th percentile. This supports the decreased emphasis placed on the absolute score cut-point of 300 in previous ACC/AHA guidelines, as it is redundant with the 75th percentile, and because many men >70 years old who may fall below the 75th percentile with CAC >300 are already outside the age range of primary prevention treatment guidelines. In sensitivity analyses stratified by race, the relative differences were not significant enough to derive a rule of thumb specifically for race (Supplementary Table 1). For example, because other races/ethnicity have lower CAC than White patients, participants with CAC >0 at age <50 years and similarly with CAC >100 at age <60 years are likely to be over the 75th percentile. This emphasizes the specificity of our “rule of thumb” across race/ethnicity.

Discussion

A detailed study deriving CAC score percentiles and an online calculator from MESA data has been previously published.6 Using data in patients 30 to 45 years from 3 harmonized datasets, Javaid et al7 recently created an interactive webpage tool to obtain corresponding estimated percentiles using age, gender, race, and CAC score. The authors use a simple rule of thumb that will place young people with any CAC at >75th percentile.

In our study, we extend previous work by emphasizing the 75th percentile, which has gained new relevance since its inclusion in multiple clinical guidelines. These findings will be useful for clinicians who may want easy ways to identify patients likely to benefit from statin therapy. In addition, it provides clinicians with a simple approach to understanding the relation between absolute CAC scores and percentiles. According to the 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines, starting statins is reasonable in those with CAC >100 Agatston units or >75th age/gender/race percentile. Our rule of thumb makes it easier for clinicians to identify patients whose CAC score places them in this percentile category and thus would benefit from lipid-lowering therapies in addition to lifestyle modification. It will also help clinicians identify select groups to initiate discussions on aspirin therapy, weighing potential benefits versus risk of bleeding.

Our study had some limitations. First, we chose to include those with diabetes mellitus, as this remains a population where risk stratification is still relevant, although the original MESA study deriving CAC percentiles excluded those with diabetes mellitus. For simplicity, we did not try to account for race/ethnicity differences. Although percentiles vary subtly by race, our sensitivity testing suggested that race does not produce a clinically significant change to the overall conclusions. Another limitation is the use of age deciles to derive our rule of thumb may make it less useful in certain age groups, such as when the age is 51 or 61 years. However, our approach is still highly valuable to busy clinicians and could be supplemented using an online calculator.

In conclusion, this study provides a simple rule of thumb (men <50 years and women <60 years with any CAC, men <60 years and women <70 years with CAC >100) for identifying CAC >75th percentile that might be readily adopted in practice for implementing clinical guidelines and identifying those at intermediate risk who are likely to benefit from statins per guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, United States and by grants UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, UL1-TR-001420 and UL1-TR-001881 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, United States.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.06.006.

References

- 1.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, Michos ED, Miedema MD, Muñoz D, Smith SC Jr, Virani SS, Williams KA Sr, Yeboah J, Ziaeian B. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e596–e646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones D, Lopez-Pajares N, Ndumele CE, Orringer CE, Peralta CA, Saseen JJ, Smith SC, Sperling L, Virani SS, Yeboah J. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:3168–3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hecht H, Blaha MJ, Berman DS, Nasir K, Budoff M, Leipsic J, Blankstein R, Narula J, Rumberger J, Shaw LJ. Clinical indications for coronary artery calcium scoring in asymptomatic patients: expert consensus statement from the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017;11:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaha MJ, Matsushita K. Coronary artery calcium: need for more clarity in guidelines. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Roux AV Diez, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClelland RL, Chung H, Detrano R, Post W, Kronmal RA. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by race, gender, and age: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2006;113:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javaid A, Dardari ZA, Mitchell JD, Whelton SP, Dzaye O, Lima JoaoAC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Budoff M, Nasir K, Berman DS, Rumberger J, Miedema MD, Villines TC, Blaha MJ. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by age, sex, and race among patients 30−45 years old. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:1873–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.