Abstract

Previous studies have shown that fully vaccinated patients with SARS-CoV-2 Delta variants has shorter viable viral shedding period compared to unvaccinated or partially vaccinated patients. However, data about effects of vaccination against the viable viral shedding period in patients with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants were limited. We compared the viable viral shedding period of SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant regard to vaccination status. Saliva samples were obtained daily from patients with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant, and genomic assessments and virus culture was performed to those samples. We found no difference in viable viral shedding period between fully vaccinated and not or partially vaccinated, nor between 1st boostered vs non-boostered patients with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Infection dynamics, Virus shedding

1. Introduction

Since the rollout of vaccines against coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), several studies have demonstrated that COVID-19 vaccines significantly reduce the disease severity and mortality [1]. However, due to the emergence of variants, waning vaccine-induced immunity, and lack of mucosal immunity after vaccination, breakthrough infections frequently occur [2]. Despite these breakthrough infections, COVID-19 vaccination consistently reduced secondary attack rates and the viable viral shedding period before the omicron dominant era [3].

The omicron variant has a shorter incubation period and higher transmissibility than the prior dominant variants, such as delta [4], [5]. In addition, the omicron variant evades immunity from previous vaccination against COVID-19 and prior SARS-CoV-2 infection [4]. Therefore, it is still unsettled question about whether COVID-19 vaccination may affect the viable viral shedding kinetics. We thus compared the viral shedding period through longitudinal sampling of dense respiratory samples from healthcare workers (HCW) and hospitalized patients with omicron variants to evaluate the effect of vaccination on the viral kinetics of the omicron variant.

2. Methods

We prospectively enrolled HCW and hospitalized patients who were confirmed to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 February 1, 2021 to May 31, 2022. Patients with known prior history of COVID-19 infection was excluded. During the study period, the participants were instructed to submit daily saliva samples. Culture-based virus isolation, genomic- and subgenomic RNA RT-PCR were performed on the samples. Among them, participants confirmed to be infected with omicron variants were included in this analysis. Survival analysis with log-rank tests and stratified Cox’s proportional hazard models were used to compare the viral shedding period. Variable selection in multivariable model were based on known risk factors from past studies: vaccination status, immune status and disease severity [6]. The details of the patient selection, sample collection, definitions of vaccination status, sample handling, identification of variants, and statistical analysis can be found in the Supplemental material.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1 . A total of 75 patients were confirmed to have omicron infection. Among these, 15 patients were not or partially vaccinated, and the remaining 60 patients were fully vaccinated. There was statistically significant heterogeneity between the two groups, especially for age and disease severity. Fully vaccinated groups tended to be younger (median 63 years, IQR [52, 73] vs. 35 years, IQR [27, 67], p = 0.03), and did not suffer from severe disease (p = 0.001). The underlying comorbidities were comparable between the two groups, except for hypertension (6/15 [40%] vs. 6/60 [10%], p = 0.02) and Charlson’s comorbidity index (4, IQR [2], [7] vs. 0, IQR [0, 4], p = 0.005). The median duration from the last vaccination in the fully vaccinated group was 97 days (IQR 82, 119).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristics |

Not or Partially vaccinated (N = 15) |

Fully vaccinated (N = 60) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (IQR) | 63 (52, 73) | 35 (27, 67) | 0.03 |

| Male sex | 11 (73) | 27 (45) | 0.09 |

| Occupation | 0.001 | ||

| Inpatient | 15 (1 0 0) | 28 (53) | |

| Healthcare worker | 0 | 32 (58) | |

| Severity | 0.001 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 4 (27) | 25 (46) | |

| Mild | 5 (33) | 31 (52) | |

| Moderate | 2 (13) | 4 (7) | |

| Severe | 3 (20) | 0 | |

| Critical | 1 (7) | 0 | |

| Vaccination Status | <0.001 | ||

| No | 13 (87) | 0 | |

| Partially vaccinated | 2 (13) | 0 | |

| Fully vaccinated | 0 | 23 (38) | |

| 1st boosted | 0 | 37 (62) | |

| Duration from last vaccination, median days (IQR) | 99 (5, 193) | 97 (82, 122) | |

| Underlying illness | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (33) | 9 (15) | 0.21 |

| Hypertension | 6 (40) | 6 (10) | 0.02 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (27) | 7 (12) | 0.29 |

| Chronic liver disease | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 0.88 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 3 (20) | 1 (2) | 0.03 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 2 (3) | >0.99 |

| Immunocompromised | 3 (20) | 5 (8) | 0.40 |

| Solid cancer | 4 (27) | 11 (18) | 0.72 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (IQR) | 4 (2, 7) | 0 (0, 4) | 0.005 |

| Duration from symptom onset to first sampling, median days (IQR) |

3 (1.5, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | 0.91 |

NOTE. Data are presented as number of patients (%) unless otherwise indicated.

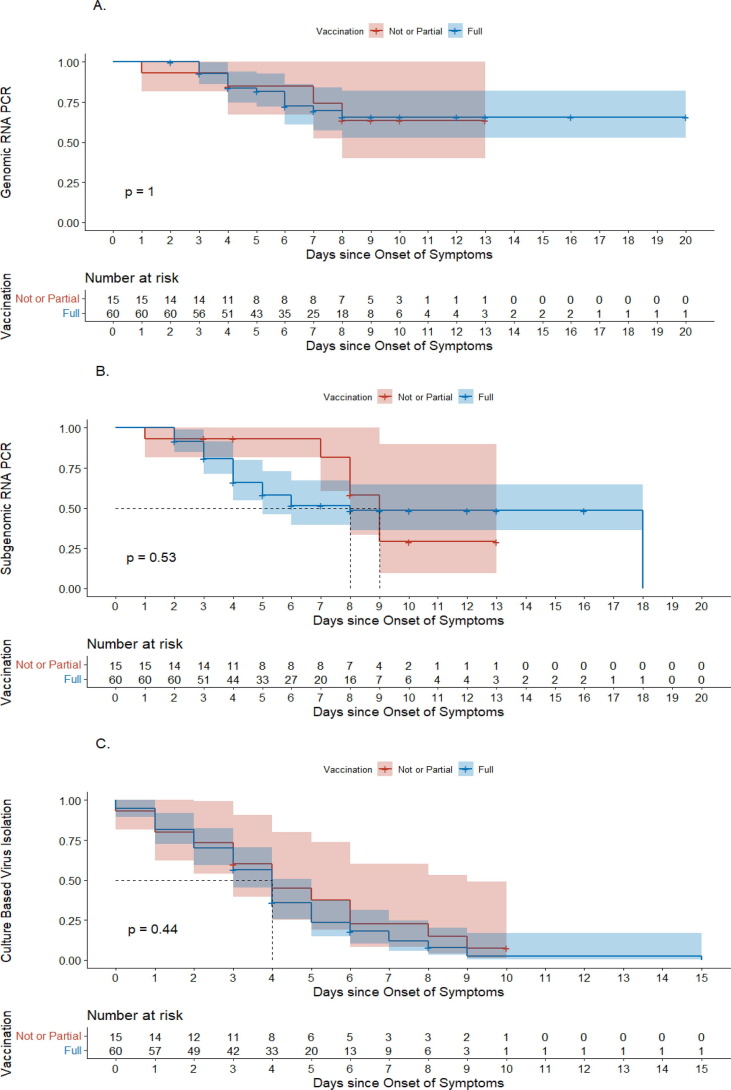

3.2. Viral shedding periods

Overall viral copy number and culture positivity of the two groups are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. In the fully vaccinated group, no samples were culture-positive after day 8, whereas it was non-culturable after day 10 in the not or partially vaccinated group. Survival analysis of the shedding period of viruses is shown in Fig. 1 . The viral shedding periods between fully vaccinated and partially or not vaccinated patients were comparable among the three different assessment methods: genomic RNA PCR (median NA, IQR [7, NA] vs. median NA, IQR [6, NA], p > 0.99: Fig. 1A), subgenomic RNA PCR, (median 9 days, IQR [8, NA] vs. median 8 days, IQR [4, 18], p = 0.53: Fig. 1B) and culture-based virus isolation (median 4 days, IQR [2], [6] vs 4 days, IQR [2], [5], p = 0.44: Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the viral shedding period between fully vaccinated and not or partially vaccinated patients with the omicron variant. (A) Genomic RNA PCR. (B) Subgenomic RNA PCR. (C) Culture-based virus isolation. The red line indicates the delta group, whereas the blue line indicates the omicron group. The P-values in the figures were calculated with the log-rank test.

In univariate and multivariate analysis comparing the viable viral shedding period of breakthrough infections and non-breakthrough infections of the omicron variant, vaccination status including a booster dose does not appear to shorten the period (HR 0.48, 95% CI [0.05–4.76], p = 0.54: Supplemental Table 1). Other variables previously known to affect the viable shedding period of COVID-19, such as immunocompromised status (HR 3.33, 95% CI [0.36–33.33], p = 0.29) and disease severity (HR 3.03, 95% CI [0.29–33.33], p = 0.35), were not associated with the virus shedding period in patients with the omicron variant. Adjusted survival curves were plotted (Supplementary Figure 2), which demonstrated no influence of vaccination status on the viral shedding period (p = 0.30 by the stratified log-rank test). However, when comparing the group with completion of initial vaccine series and 1st boostered group, latter group shows significantly shorter genomic RNA viral PCR shedding period, but not in subgenomic RNA PCR and culture-based virus isolation (median days were not reached in both groups, p = 0.043: Supplementary Figure 3).

4. Discussion

Our previous studies conducted before the omicron-dominant era revealed that full COVID-19 vaccination significantly shortened the viable virus shedding period [3], and this result was consistent with another study [7]. Nevertheless, unlike the previous studies conducted with earlier VOCs, the present study in the omicron-dominant era showed that viable virus shedding periods were comparable between vaccinated and unvaccinated or partially vaccinated patients, even after adjusting for the known risk factors for viable viral shedding. Actually, the study conducted during Omicron BA.1 era reported no difference in the medial duration of viral shedding between unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals [5]. Another study also showed that viable viral shedding was shortened in boosted patients than in un-boosted fully vaccinated or unvaccinated patients with Delta variant infection, while viable viral shedding was not affected by vaccination during Omicron-dominant period [8]. The other study revealed that only boosted vaccinated patients but not fully vaccinated patients who had Omicron BA.1 infection had reduced infectious compared to unvaccinated individuals [9]. In addition, the previous study from Hong Kong found that BNT162b2 vaccination status was not associated with the decline of Ct value during the Omicron dominant period [10]. These findings warrant the current trend toward less emphasis on immune passports, such as vaccine passes, in the omicron dominant era.

Our counter-intuitive findings might be explained by several reasons. First, the omicron variant may have a shorter incubation period and viable viral shedding than previous variants [5]. So, the period during which COVID-19 vaccination could reduce viable viral shedding might be too small. Second, a neutralizing antibody titer against the omicron variant that can be achieved by 2-dose or booster dose vaccination might not be high enough to reduce viable viral shedding. A previous study on the neutralizing antibody titer against omicron after a booster dose [11] supports this hypothesis. Third, the omicron variant is more likely to be confined to the upper respiratory tract [12], and a higher plasma neutralizing antibody titer might be needed to reduce viable viral shedding. Further studies, including animal models, are needed to confirm these hypotheses.

One may argue that previous asymptomatic infection may alter the viral shedding periods and thus act as a confounding factor in present study. However, at the beginning of study period (February 1, 2022), the number of cumulative cases of SARS-CoV-2 was 860,042 (1,661 per 100,000 persons) in South Korea [13]. Therefore, re-infection issue may not substantially affect our main findings.

Our study has several limitations. First, the relatively small number of enrolled patients, especially unvaccinated or partially vaccinated individuals, may have low power to find a statistical significance. In addition, it is difficult to draw a firm conclusion because there are the large heterogeneity between groups in terms of the dominancy of healthcare workers in fully vaccinated group and more severe illness in unvaccinated group, although we adjusted the risk factors for viable viral shedding including disease severity and immunocompromised status. However, there were limited data about vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants, thus the results of present study can be a starting point for further studies. Second, there might be unmeasured confounders in unvaccinated or partially vaccinated individuals that could affect viable viral shedding, although we adjusted for possible confounders affecting viral shedding kinetics. Third, viable viral shedding does not necessarily mean a transmissible period. So, cautious interpretation is needed. Fourth, we did not performed whole genome sequencing, thus we did not know which subvariants was dominant among patients. Also, all patients were vaccinated against wild type strain of SARS-CoV-2; thus, further studies on the efficacy of bivalent vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 are needed. Fifth, the lack of data about the humoral or cell-mediated immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 makes it difficult to understand the underlying mechanism of our observed findings. There are limited data on the effect of antibody levels and cell-mediated immune responses in certain time point on viable viral shedding between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Further studies are needed on this issue. Despite these limitations, our study did not find that COVID-19 vaccination substantially decreased viable viral shedding in omicron variant infection as shown for previous immune-evasive variants such as the delta variant.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), which is funded by the National Institute of Health (Grant No. HD22C2045), and from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (NRF-2022M3A9I2017241).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.03.044.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Chagla Z. The BNT162b2 (BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccine had 95% efficacy against COVID-19 ≥7 days after the 2nd dose. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2):JC15. doi: 10.7326/ACPJ202102160-015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.E.G. Levin, Y. Lustig, C. Cohen, R. Fluss, V. Indenbaum, S. Amit, R. Doolman, K. Asraf, E. Mendelson, A. Ziv, C. Rubin, L. Freedman, Y. Kreiss, G. Regev-Yochay, Waning Immune Humoral Response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine over 6 Months, N Engl J Med 385(24) (2021) e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Jung J., Kim J.Y., Park H., Park S., Lim J.S., Lim S.Y., et al. Transmission and Infectious SARS-CoV-2 Shedding Kinetics in Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Individuals. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2213606. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung C., Kmiec D., Koepke L., Zech F., Jacob T., Sparrer K.M.J., et al. Omicron: What Makes the Latest SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern So Concerning? J Virol. 2022;96(6):e0207721. doi: 10.1128/jvi.02077-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boucau J., Marino C., Regan J., Uddin R., Choudhary M.C., Flynn J.P., et al. Duration of Shedding of Culturable Virus in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (BA.1) Infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):275–277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2202092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang S.W., Park H., Kim J.Y., Park S., Lim S.Y., Lee S., et al. Clinical scoring system to predict viable viral shedding in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2022;157 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.R. Ke, P.P. Martinez, R.L. Smith, L.L. Gibson, C.J. Achenbach, S. McFall, C. Qi, J. Jacob, E. Dembele, C. Bundy, L.M. Simons, E.A. Ozer, J.F. Hultquist, R. Lorenzo-Redondo, A.K. Opdycke, C. Hawkins, R.L. Murphy, A. Mirza, M. Conte, N. Gallagher, C.H. Luo, J. Jarrett, A. Conte, R. Zhou, M. Farjo, G. Rendon, C.J. Fields, L. Wang, R. Fredrickson, M.E. Baughman, K.K. Chiu, H. Choi, K.R. Scardina, A.N. Owens, J. Broach, B. Barton, P. Lazar, M.L. Robinson, H.H. Mostafa, Y.C. Manabe, A. Pekosz, D.D. McManus, C.B. Brooke, Longitudinal Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Breakthrough Infections Reveals Limited Infectious Virus Shedding and Restricted Tissue Distribution, Open Forum Infectious Diseases 9(7) (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Fall A., Eldesouki R.E., Sachithanandham J., Morris C.P., Norton J.M., Gaston D.C., et al. The displacement of the SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta with Omicron: An investigation of hospital admissions and upper respiratory viral loads. EBioMedicine. 2022;79 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhach O., Adea K., Hulo N., Sattonnet P., Genecand C., Iten A., et al. Infectious viral load in unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals infected with ancestral, Delta or Omicron SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01816-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Tam A.R., Chu W.-M., Chan W.-M., Ip J.D., Chu A.-H., et al. Risk Factors for Slow Viral Decline in COVID-19 Patients during the 2022 Omicron Wave. Viruses. 2022;14(8):1714. doi: 10.3390/v14081714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews N., Stowe J., Kirsebom F., Toffa S., Rickeard T., Gallagher E., et al. Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1532–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui K.P.Y., Ho J.C.W., Cheung M.C., Ng K.C., Ching R.H.H., Lai K.L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature. 2022;603(7902):715–720. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.K.D.C.a.P. Agency, Corona 19 vaccinations and domestic outbreaks (2.1.). <https://ncov.kdca.go.kr/tcmBoardView.do?brdId=3&brdGubun=31&dataGubun=&ncvContSeq=6339&contSeq=6339&board_id=312&gubun=ALL>, 2022 (accessed September 1st.2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.