Summary

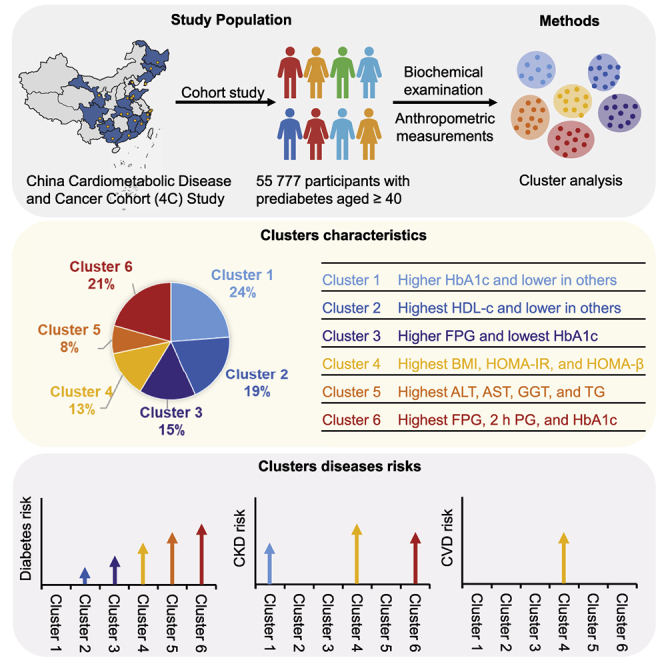

Prediabetes and its pathophysiology remain important issues. We aimed to examine the cluster characteristics of prediabetes and explore their associations with developing diabetes and its complications based on 12 variables representing body fat, glycemic measures, pancreatic β cell function, insulin resistance, blood lipids, and liver enzymes. A total of 55,777 individuals with prediabetes from the China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort (4C) were classified at baseline into six clusters. During a median of 3.1 years of follow-up, significant differences in the risks of diabetes and its complications between clusters were observed. The odds ratios of diabetes stepwisely increase from cluster 1 to cluster 6. Clusters 1, 4, and 6 have increased chronic kidney diseases risks, while the prediabetes in cluster 4, characterized by obesity and insulin resistance, confers higher risks of cardiovascular diseases compared with others. This subcategorization has potential value in developing more precise strategies for targeted prediabetes prevention and treatment.

Keywords: prediabetes, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, cluster analysis

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Individuals with prediabetes have heterogeneity in metabolic features

-

•

Prediabetes can be classified into six subgroups with different disease risks

-

•

Prediabetes with obesity and insulin resistance has the highest CVD risk

-

•

There are specific trends of transition from prediabetes clusters to diabetes clusters

Zheng et al. use data-driven clustering approaches to confirm the heterogeneity in individuals with prediabetes and explore their associations with major diseases. Individuals with prediabetes differ in metabolic features and risks of disease progression, raising the possibility of a practical, stratified approach for the prevention of diabetes and related diseases.

Introduction

Prediabetes is a high-risk state for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), defined as levels of fasting plasma glucose (FPG), 2-h post-load plasma glucose (PG), or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) above their normal ranges but below diagnostic thresholds for diabetes.1 Almost one-third of the Chinese population has prediabetes; similar numbers were reported worldwide, including in the United States.2,3 Approximately, 5% to 10% of individuals with prediabetes will progress to diabetes per year.4 Much emphasis has been placed on finding an effective method to delay or prevent incident T2DM among those with prediabetes. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study5 and the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study6 provided strong evidence that a combination of diet and exercise interventions was the most important factor that could halt the progression to T2DM and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in patients with prediabetes. However, the questions surrounding prediabetes and its management have brought debate and remain important issues that warrant further investigation.7 For example, the high-risk population is extremely large and the costs of prevention are substantial and rising. The term “prediabetes” has also been criticized because a substantial proportion of people with prediabetes regress to normoglycemia without treatment.8 In such circumstances, it might imply that intervention is not necessary because no disease is present.

The dilemma between health benefits from the intervention and economic consideration in terms of cost-effectiveness calls for re-classification of prediabetes to enable precise and effective intervention in those at the greatest risk of T2DM and other complications. Wagner et al. used clustering analysis to classify Caucasian individuals at elevated risk for T2DM into six clusters with different metabolic features and disease risks.9 Their results demonstrated that pathophysiological heterogeneity exists before the diagnosis of T2DM and highlighted groups differing in the risk for T2DM and its complications.9 However, physiological features are different between Asian and Caucasian individuals. The Chinese population is more likely to have an impaired β-cell function and is more susceptible to the effects of overall obesity on metabolic factors.10,11 It is unknown whether Chinese people with prediabetes can be classified into different subphenotypes.

We aimed to examine and validate whether measurements of metabolic parameters endorse the prediabetes clusters, and whether there are differences in disease risks between clusters. We postulated that specific cluster-based subphenotypes of prediabetes correlate with T2DM and complications differently, therefore individualized intervention is required.

Results

Study population

A total of 193,846 adults aged 40 years or older were recruited from the China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort (4C) study at baseline, and 170,240 (87.8%) participants attended an in-person follow-up visit.10,12 Among them, 105,590 participants were excluded because they had a major disease or did not have prediabetes at baseline; 7,416 participants were excluded because of missing data of baseline biochemical measurements and physical examination; and 1,457 participants were further excluded for having outlier values of the cluster variables. Finally, 55,777 participants with prediabetes were included in the analysis (Figure S1), and the total person-years of follow-up were 212,827 person-years.

Determination of cluster number

By visualizing the matrix heatmaps of the pairwise consensus for each cluster size (Figures S2A–S2G), the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) (Figure S2H), and the proportion increase of the area under the CDFs (Figure S2I), the consensus clustering algorithm identified that K = 6 was the largest number of clusters best representing the data pattern of participants with prediabetes. For K = 6, the mean consensus scores were greater than 0.75 for all clusters, with a larger value indicating better stability of cluster membership (Figure S2J). The characteristics of participants in the six clusters are shown in Figure S3.

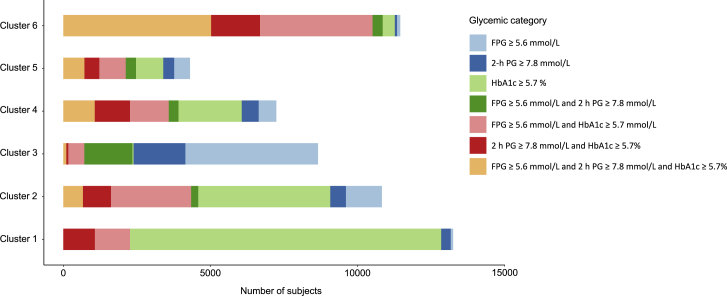

Distributions of glycemic status by clusters

We used K-means to cluster the overall prediabetes participants, and cluster stability was estimated as Jaccard means, which were greater than 0.77 for all clusters. As shown in Figure 1, the crosstabs of the participant`s number between clusters and prediabetes definitions shows that most participants with prediabetes in cluster 1 and cluster 2 were diagnosed by HbA1c ≥5.7% only. Almost half of the participants in cluster 3 only had FPG ≥5.6 mmol/L; in cluster 4 and cluster 5, the participants with more than one abnormal glycemic criterion outweighed those with only one abnormal criterion; and almost 50% of those with prediabetes in cluster 6 had abnormal FPG, 2 h PG, and HbA1c, simultaneously.

Figure 1.

The number of participants in each group of glycemic status by clusters

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; 2 h PG, 2 h post-load plasma glucose.

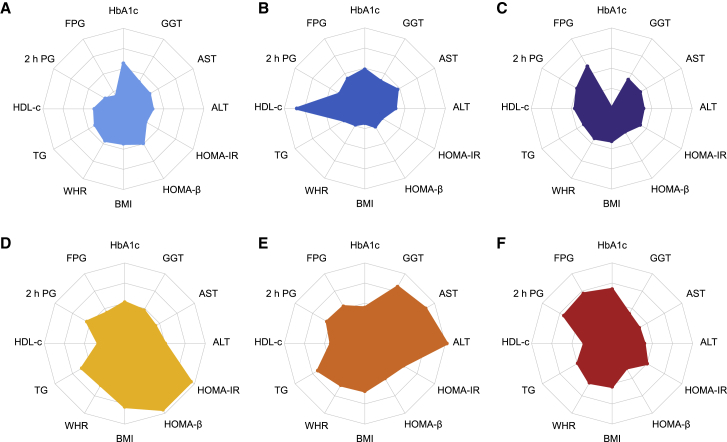

Distribution of the clinical features by clusters

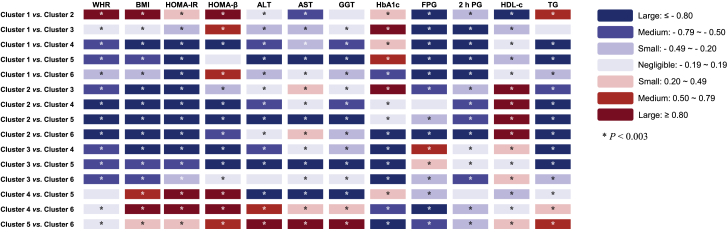

Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical data for the six clusters are shown in Table 1. The six clusters showed distinctive patterns displayed by standardized means of cluster variables (Figure 2, Table S1). Cluster 1, including 13,258 (23.8%) participants, was marked by relatively higher levels of HbA1c but lower levels of other features. Cluster 2 comprised 10,836 (19.4%) participants. These individuals had the highest levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) than the other clusters and similar HbA1c levels as cluster 1. Cluster 3 constituted 8,664 (15.5%) participants. This group was characterized by higher levels of FPG and the lowest HbA1c level than the other clusters. Cluster 4, including 7,246 (13.0%) participants, was marked by the highest levels of body mass index (BMI), homoeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and homoeostasis model assessment β of cell function (HOMA-β). Cluster 5 comprised 4,310 (7.7%) participants with the highest levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), glutamyl transferase (GGT), and triglyceride (TG). Cluster 6, including 11,463 (20.6%) participants, was characterized by the highest levels of FPG, 2 h PG, and HbA1c. The pairwise comparisons of the clustering variables between clusters are shown in Figure 3. Most differences achieved Bonferroni adjusted statistical significance (p < 0.003), and half of them showed small or negligible differences tested by using Cohen’s d value (Table S2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants in six clusters

| Cluster 1 (n = 13,258, 23.8%) | Cluster 2 (n = 10,836, 19.4%) | Cluster 3 (n = 8664, 15.5%) | Cluster 4 (n = 7246, 13.0%) | Cluster 5 (n = 4310, 7.7%) | Cluster 6 (n = 11,463, 20.6%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 8923 (67.3%) | 7825 (72.2%) | 5399 (62.3%) | 5279 (72.9%) | 2094 (48.6%) | 7495 (65.4%) |

| Age (y) | 56.08 ± 8.35 | 56.59 ± 8.45 | 54.42 ± 8.78 | 56.12 ± 8.56 | 54.75 ± 7.90 | 58.19 ± 8.23 |

| High school or higher education | 5032 (38.0%) | 3611 (33.3%) | 2731 (31.5%) | 2722 (37.6%) | 1531 (35.5%) | 3987 (34.8%) |

| Married | 12,096 (91.2%) | 9812 (90.6%) | 8036 (92.8%) | 6616 (91.3%) | 4004 (92.9%) | 10,407 (90.8%) |

| Current smoking | 2200 (16.6%) | 1511 (13.9%) | 1256 (14.5%) | 760 (10.5%) | 1033 (24.0%) | 1525 (13.3%) |

| Current drinking | 1046 (7.9%) | 1244 (11.5%) | 1161 (13.4%) | 441 (6.1%) | 869 (20.2%) | 1155 (10.1%) |

| Moderate and vigorous physical activity | 2156 (16.3%) | 1546 (14.3%) | 1118 (12.9%) | 981 (13.5%) | 540 (12.5%) | 1820 (15.9%) |

| Current drinking tea | 3350 (25.3%) | 2313 (21.3%) | 1894 (21.9%) | 1755 (24.2%) | 1291 (30.0%) | 2957 (25.8%) |

| Healthy diet | 5904 (44.5%) | 4192 (38.7%) | 3437 (39.7%) | 3136 (43.3%) | 1787 (41.5%) | 5255 (45.8%) |

| Nighttime sleep duration (h) | 7.75 ± 1.25 | 7.95 ± 1.38 | 8.00 ± 1.32 | 7.75 ± 1.26 | 7.85 ± 1.28 | 7.77 ± 1.26 |

| Family history of diabetes | 1426 (10.8%) | 976 (9.0%) | 768 (8.9%) | 942 (13.0%) | 515 (11.9%) | 1416 (12.4%) |

| Taking antihypertensive medicine | 1057 (8.0%) | 529 (4.9%) | 640 (7.4%) | 970 (13.4%) | 461 (10.7%) | 1465 (12.8%) |

| Taking lipid-lowering medicine | 55 (0.4%) | 34 (0.3%) | 18 (0.2%) | 58 (0.8%) | 38 (0.9%) | 76 (0.7%) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.12 ± 2.66 | 21.55 ± 2.36 | 23.88 ± 2.63 | 27.80 ± 3.17 | 25.79 ± 2.95 | 25.22 ± 2.72 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 127.52 ± 19.04 | 128.00 ± 19.98 | 132.35 ± 19.61 | 135.70 ± 19.06 | 134.11 ± 19.10 | 133.28 ± 19.19 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 76.25 ± 10.48 | 75.36 ± 10.83 | 79.15 ± 10.66 | 81.49 ± 10.64 | 81.58 ± 10.83 | 79.29 ± 10.31 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.12 ± 0.37 | 5.51 ± 0.46 | 5.79 ± 0.40 | 5.53 ± 0.49 | 5.67 ± 0.49 | 5.97 ± 0.42 |

| 2 h PG (mmol/L) | 6.09 ± 1.32 | 6.61 ± 1.53 | 7.28 ± 1.56 | 7.52 ± 1.58 | 7.52 ± 1.68 | 8.27 ± 1.44 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.90 ± 0.20 | 5.82 ± 0.25 | 5.34 ± 0.27 | 5.85 ± 0.29 | 5.78 ± 0.31 | 6.01 ± 0.22 |

| HOMA-β | 76.83 (58.25, 98.80) | 46.99 (34.62, 61.88) | 56.87 (42.42, 73.88) | 132.00 (112.03, 162.86) | 78.18 (58.10, 100.00) | 61.85 (47.58, 76.97) |

| HOMA-IR | 1.40 (1.06, 1.77) | 1.13 (0.82, 1.49) | 1.65 (1.23, 2.13) | 3.27 (2.69, 4.02) | 2.08 (1.55, 2.68) | 1.96 (1.52, 2.45) |

| HDL-c (mmol/L) | 1.24 ± 0.26 | 1.75 ± 0.31 | 1.34 ± 0.29 | 1.20 ± 0.28 | 1.30 ± 0.30 | 1.22 ± 0.28 |

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.83 ± 0.84 | 2.96 ± 0.82 | 2.79 ± 0.80 | 3.03 ± 0.87 | 3.05 ± 0.90 | 2.92 ± 0.86 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.74 ± 1.07 | 5.30 ± 0.98 | 4.80 ± 1.01 | 5.13 ± 1.08 | 5.31 ± 1.08 | 4.93 ± 1.11 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.25 (0.92, 1.69) | 0.95 (0.75, 1.24) | 1.22 (0.90, 1.66) | 1.84 (1.35, 2.58) | 1.96 (1.37, 2.88) | 1.49 (1.10, 2.06) |

| ALT (U/L) | 12.10 (9.00, 17.00) | 13.00 (10.00, 17.00) | 14.00 (10.00, 18.00) | 17.65 (13.00, 23.00) | 36.00 (29.00, 45.00) | 14.00 (11.00, 19.00) |

| AST (U/L) | 19.37 ± 5.23 | 22.47 ± 6.08 | 20.52 ± 5.55 | 21.49 ± 6.02 | 35.76 ± 10.52 | 19.81 ± 5.10 |

| GGT (U/L) | 17.00 (13.00, 24.00) | 17.00 (13.00, 24.00) | 19.00 (14.00, 28.00) | 25.00 (19.00, 36.00) | 53.00 (33.00, 88.00) | 20.00 (15.00, 29.00) |

| ACR mg/g | 5.28 (3.44, 8.48) | 5.82 (3.79, 9.50) | 5.47 (3.45, 9.03) | 5.87 (3.63, 10.11) | 5.53 (3.52, 9.43) | 5.66 (3.49, 9.41) |

| eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2 | 97.45 (89.60, 103.60) | 95.91 (88.33, 101.81) | 97.93 (90.04, 104.58) | 94.98 (86.10, 101.96) | 95.71 (87.23, 102.05) | 94.88 (86.46, 101.25) |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD, number (percentage), or median (interquartile range).

ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting glucose; GGT, glutamyl transferase; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-β, homoeostasis model assessment β of cell function; HOMA-IR, homoeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL-c, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TG, triglyceride; 2 h PG, 2-h post-load plasma glucose.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the cluster feature variables by clusters

All the values of cluster features were centered to a mean value of 0 and an SD of 1. All the negative values were converted to positive values by adding a fixed value to yield polygon areas related to adverse variable effects. (A) Cluster 1; (B) Cluster 2; (C) Cluster 3; (D) Cluster 4; (E) Cluster 5; (F) Cluster 6. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-β, homoeostasis model assessment β of cell function; HOMA-IR, homoeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; TG, triglyceride; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; 2 h PG, 2-h post-load plasma glucose.

See also Table S1.

Figure 3.

Pairwise comparisons of the cluster feature variables

Bonferroni correction was applied with p < 0.003 (0.05/15) as statistical significance. The blue or red color presented the Cohen’s d values that indicated the standardized difference between the two means. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; 2 h PG, 2-h post-load plasma glucose; TG, triglyceride; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; BMI, body mass index; HOMA-β, homoeostasis model assessment β of cell function; HOMA-IR, homoeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.

See also Table S2.

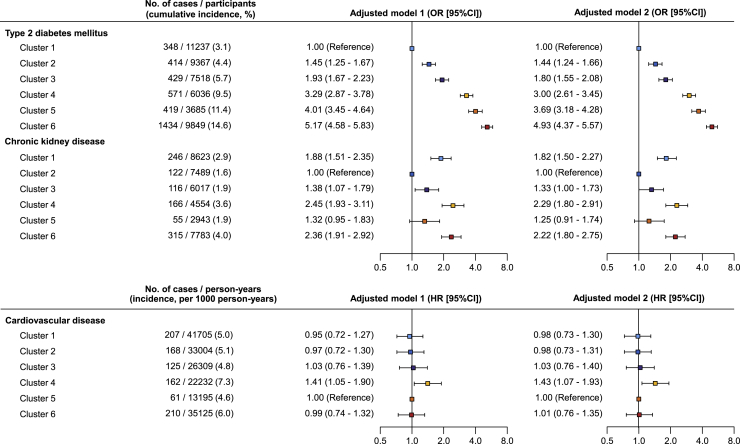

Associations of prediabetes clusters with major diseases

During a median of 3.1 years of follow-up, 3,615 and 1,020 participants with prediabetes developed T2DM and chronic kidney disease (CKD), respectively. We found significant differences in T2DM incidence between clusters and the risks of T2DM were stepwisely increased from cluster 1 to cluster 6 (Figure 4, Table S3). Compared with cluster 1, which had the lowest incidence of T2DM, the odds ratios (ORs) for developing T2DM in cluster 2 to cluster 6 were 1.44 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24–1.66), 1.80 (95% CI, 1.55–2.08), 3.00 (95% CI, 2.61–3.45), 3.69 (95% CI, 3.18–4.28), and 4.93 (95% CI, 4.37–5.57) in adjusted model 2, respectively. The incidence of CKD between clusters was also different, and cluster 2 had the lowest incidence of CKD (Figure 4). Compared with cluster 2, cluster 1 (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.50–2.27), cluster 4 (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.80–2.91), and cluster 6 (OR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.80–2.75) were at significantly higher risk for developing CKD. A total of 933 participants with prediabetes at baseline had incident CVD events during the follow-up. After adjusting for other covariates, cluster 4 had a significantly higher risk of incident CVD events compared with cluster 5 (Figure 4) and also other clusters (Table S3).

Figure 4.

Comparisons of disease risks by clusters

The cumulative incidences of type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease were calculated by using the number of incident cases divided by the number of participants at risk in each cluster, the incidence of cardiovascular disease using the number of incident cases divided by the total observation duration (person-years) in each cluster. Incident type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney diseases between clusters were compared by logistic regression models and cardiovascular disease between clusters by Cox proportional hazards models. For each outcome, the cluster with the lowest incidence was used as the reference group. Model 1 was adjusted for age and gender. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, drinking tea, healthy diet score, physical activity, family history of diabetes, nighttime sleep duration, systolic blood pressure, currently taking antihypertensive medication, and taking lipid-lowering agents.

See also Table S3.

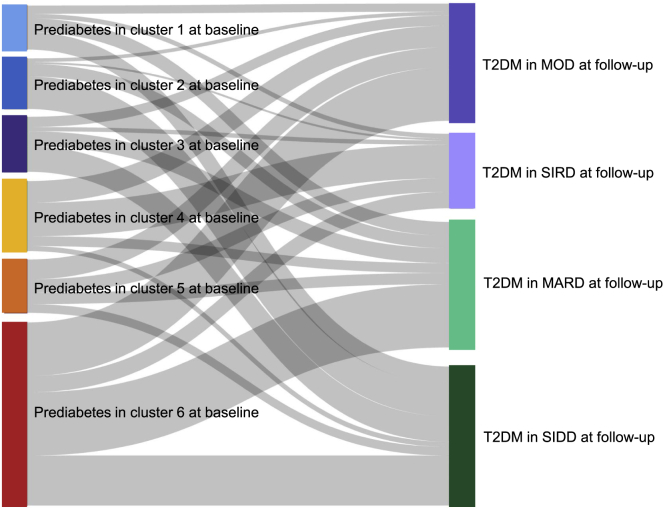

Cluster migration patterns from prediabetes clusters at baseline to normal glucose regulation, prediabetes clusters, and T2DM clusters at follow-up

We also performed clustering analysis using the same variables collected at the follow-up examination among the participants diagnosed as prediabetes at follow-up, and similar cluster features were observed (Figure S4). We found that, among the participants who had taken follow-up examination, there were 40.7%, 37.5%, 39.3%, 24.2%, 24.4%, and 13.3% of the participants with prediabetes in clusters 1 to 6 who regressed to normal glucose regulation (NGR), respectively. Among the participants who had migrated from prediabetes clusters at baseline to NGR, prediabetes clusters and T2DM at follow-up, 22.4%, 33.6%, 28.3%, 31.4%, 20.1%, and 25.7% of those with prediabetes in clusters 1 to 6 at baseline still maintained the original cluster type at follow-up (Figure S4, Table S4). We applied K-means clustering analysis among the participants with prediabetes at baseline and progression to T2DM at the follow-up visit using five variables collected at the follow-up, including age at diagnosis, BMI, FPG, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-β. Every patient with T2DM at follow-up was assigned to a predefined cluster named by Ahlqvist and colleagues, including mild age-related diabetes (MARD), mild obesity-related diabetes (MOD), severe insulin-resistant diabetes (SIRD), or severe insulin-deficient diabetes (SIDD) (Figure S5, Tables S4–S6). The Sankey diagram shows the patterns of cluster redistributions and migrations from prediabetes clusters at baseline to diabetes clusters at follow-up (Figure 5). We found a clear pattern of differences between clusters in clinical characteristics and were able to assign the same cluster as Ahlqvist and colleagues did (Table S4). In prediabetes cluster 1 who developed T2DM at follow-up, 99 (31.4%) and 124 (39.4%) of the participants progressed to T2DM MARD cluster and SIDD cluster, respectively. In cluster 2, 232 (64.3%) transformed into the T2DM SIDD cluster; 182 (46.3%) of individuals in prediabetes cluster 3 were assigned to the T2DM SIDD cluster. In individuals with prediabetes of cluster 4, 30.9% and 47.9% were transitioned to the T2DM MOD cluster and SIRD cluster, respectively; 37.3% of the participants in cluster 5 developed into the T2DM MOD cluster; and 34.5% of cluster 6 developed into the T2DM MARD cluster (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cluster migration pattern from prediabetes clusters at baseline to those who developed type 2 diabetes of Ahlqvist-diabetes-classes at follow-up

MARD, mild age-related diabetes; MOD, mild obesity-related diabetes; SIDD, severe insulin-deficient diabetes; SIRD, severe insulin-resistant diabetes;.

See also Figure S5, Tables S4–S6.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was performed by conducting clustering analysis using the same variables among the participants with normoglycemia and those with prediabetes at baseline. The cluster features in each cluster and the differences in disease risks were similar to those only conducted in prediabetes (Figure S6).

Discussion

In this Chinese population with prediabetes, we discovered that the data-driven clusters were reproducible and could be classified into six clusters of distinct metabolic profiles. Future risks of diabetes varied between clusters. Three of the identified subphenotypes had increased CKD risk, including cluster 1 characterized by a single high level of HbA1c, cluster 4 characterized by obesity and insulin resistance, and cluster 6 characterized by high glycemic levels. But only prediabetes in cluster 4 conferred a higher risk of CVD compared with others. Nearly 40% of those with prediabetes in clusters 1, 2, and 3; 24% of those with prediabetes in clusters 4 and 5; and 13% of those with prediabetes in cluster 6 would reverse to NGR. Approximately 20%–30% of each prediabetes cluster would maintain the original prediabetes status during 3 years of follow-up. Finally, for participants with prediabetes who had developed T2DM during follow-up, there were apparent and specific trends of transitions from different clusters of prediabetes into the Ahlqvist classification of diabetes. Those with prediabetes in clusters 1, 2, and 3 mostly progressed to the T2DM MARD cluster and SIDD cluster, while cluster 4 and cluster 5 progressed to the T2DM MOD cluster and SIRD cluster.

The glucose tolerance test was reported to be more sensitive in identifying individuals who were at high risk for prediabetes and diabetes in Asian individuals.13 Therefore, despite having a relatively higher level of HbA1c in those with prediabetes of cluster 1, the lowest levels of both FPG and 2 h PG might contribute to the lowest incidence of T2DM in cluster 1. Even though T2DM incidence was slightly higher in cluster 2 compared with cluster 1, the CKD risk was substantially lower in cluster 2. A high level of HDL-c might exert the protective effects of preventing CKD in cluster 2. Normal HDL-c is involved in maintaining endothelial function and nitric oxide production, which is critical in preserving tissue perfusion and preventing leukocyte adhesion and infiltration, while deficiency and dysfunction of HDL-c contribute to the severity of oxidative stress and inflammation and promote the progression of CKD.14 Cluster 3 also had an increased incidence of T2DM compared with cluster 1 due to a higher level of FPG and 2 h PG, and the risk of incident CKD was significantly lower than that in cluster 1. The findings implied that the high HbA1c level was more closely associated with incident CKD than high levels of FPG and 2 h PG.

Previous studies have suggested individuals at the highest risk of developing diabetes are those with FPG of 6.1–6.9 mmol/L or HbA1c of 6.0%–6.4%, or women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus.15 Our study made further progress in identifying the individuals with a higher risk of T2DM who were not only with high glycemia levels (cluster 6) but also prediabetes with obesity and insulin resistance (cluster 4), and prediabetes with elevated liver enzymes and hypertriglyceridemia (cluster 5). Glucose does not seem to be the major driver of CKD and CVD in cluster 4. Prediabetes in cluster 4 represented an insulin-resistant phenotype, in which participants had obesity, and higher levels of HOMA-IR and HOMA-β. It may imply that there is a compensation for insulin resistance through elevated β-cell function in secreting insulin. Previous studies have suggested that even without the well-known risk factors of hypertension or diabetes, obesity per se might be harmful to the kidney by causing hyperfiltration.16 Insulin resistance also deteriorates kidney function through alterations in hemodynamics, and podocyte and tubular function.17 Cluster 4 had lower glycemia parameter levels than cluster 6, but presented a higher risk of incident CVD than cluster 6. This result highlighted the effects of insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and attendant lipid disorders on promoting CVD.18 Prediabetes in cluster 5 was associated with significantly worse liver function. Even though cluster 5 did not present a very high level of blood glucose, it was associated with a higher risk of diabetes. Roy Taylor proposed that T2DM was a result of excess liver fat causing an excess supply of fat to the pancreas with resulting dysfunction of both organs, and leading to diabetes.19 Although we did not measure the liver fat in our study, the higher BMI and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) might reveal the higher levels of visceral fat accumulation possessed by the participants in cluster 5.

Similar to previous study,20,21 we also found a substantial number of individuals reverting from prediabetes to NGR. The Whitehall II study reported that most people with HbA1c-defined prediabetes had persistent prediabetes during 5 years of follow-up.20 By contrast, reversion to NGR was frequent among people with FPG- or 2 h PG-defined prediabetes.20 In the present study, we found different proportions of reversion by prediabetes clusters. Approximately 40% of those with prediabetes in clusters 1, 2, and 3 regressed to NGR, whereas the proportions were lower in clusters 4, 5, and 6, which might be because those with prediabetes in clusters 4, 5, and 6 were mostly diagnosed by more than one abnormal glycemic index that indicated worse glycemia metabolism. By performing re-clustering analysis among prediabetes at follow-up, we demonstrated that the prediabetes clusters were not stable, only 20%–30% of the prediabetes would keep the original prediabetes cluster types. The changes of cardiometabolic risk factors during follow-up may have had great impact on the re-classification of prediabetes clusters. In the current study, the data were collected at two time points, making it difficult to observe trends of cluster changes. Temporal trajectory data were needed to further explore the patterns of the cluster changes and the disease risk related to cluster changes.

We found specific trends of transitions from baseline prediabetes clusters to the incident T2DM of Ahlqvist classification. The strong connection between the prediabetes cluster and T2DM cluster, and risk of diabetes complications may suggest the potential value of targeted primary prevention in the management of subphenotypes of prediabetes. For example, a faster progression of renal disease and coronary events was also observed in T2DM clusters of SIRD and MARD in diabetes cluster studies.22,23 In our study, more than 60% of individuals with prediabetes in cluster 4 who had developed T2DM transitioned to T2DM clusters of SIRD and MARD. Correspondingly, prediabetes in cluster 4 was also associated with a higher risk of incident CKD and CVD.

Prediabetes has been defined by international medical organizations for more than 10 years; however, there was still controversy about defining it as a distinct pathological condition. Prediabetes is characterized by a variety of pathophysiological abnormalities,24 and the metabolic environments could lead to a broad range of glycemic fluctuations over a continuum with normoglycemia on one side and diabetes mellitus on the other, depending on the stage of process. In the present study, we only analyzed those with prediabetes in view of the priority of diabetes prevention in prediabetes. The early stages of metabolic prototypes could be excluded if only prediabetes was selected. Therefore, we also performed a sensitivity analysis by conducting the clustering analysis among the participants with normoglycemia and those with prediabetes, and similar results were observed to the findings in prediabetes alone.

Several landmark trials had proved that treating prediabetes with effective interventions could significantly alter the progression of T2DM. However, the effort to implement diabetes prevention in clinical practice has encountered some difficulties. The intervention is always resource intensive, reluctant, and declined if prediabetic individuals are unaware of their hyperglycemia condition or the effects are subtle.25,26 Our new classification of prediabetes might be useful in identifying the metabolic heterogeneity prior to the onset of T2DM and offering hints for the potential therapeutic implications. For instance, prediabetes in cluster 4 and cluster 6 should be treated with priority due to high risks of T2DM and diabetes complications. The importance of diabetes prevention might be neglected for prediabetes in cluster 5 when risk-stratification concentrated on diabetes-related glycemic cutoffs. In addition, it should be noted that while the method based on widely accessible clinical variables may be informative, it may not be sufficiently precise. Prediabetes could shift from one cluster to another over time. To advance precision medicine for preventing T2DM, the factors associated with subphenotypes shifting should be explored by integrating multidimensional data, such as genetic and omics data, sensor-based behavioral monitoring, and phenomics.27 Future studies may examine the types of intervention, such as aerobic exercise and dietary caloric restriction, that provide the greatest health advantages for people with prediabetes in various clusters.

Our study has several strengths. Our research with Chinese participants supports the novel prediabetes subgroups proposed by previous study,9 suggesting a possible generalizability of this European-oriented metabolic classification to various ethnicities and populations. We used data from a large and nationwide prospective cohort of community adults selected from 20 study sites across mainland China, including both urban and rural areas. The large sample size has enabled adequate sample size in each prediabetes cluster. We used a two-step strategy of clustering approach to ensure the stability of the discovered cluster membership and validated the results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the subphenotypes of prediabetes exhibited unique metabolic traits and were associated with different risks of developing diabetes and its complications. In particular, diabetes risks were significantly different from each other and stepwisely increased from cluster 1 to cluster 6. Three of the identified subphenotypes, including those with a single high HbA1c (cluster 1), obesity and insulin resistance (cluster 4), and high glycemic levels (cluster 6), had increased risks of developing CKD, but only the prediabetes in cluster 4 conferred a higher risk of CVD compared with others. This substratification of prediabetes might help to tailor and target those who would benefit most from early intervention on the risk factors, thereby providing the next step toward precision intervention.

Limitations of the study

Our study has several limitations. First, due to the relatively short period of follow-up duration, the risks of individual CVD components could not be estimated due to the small number of cases of each CVD component. Second, Wagner et al. used insulin secretion calculated by insulin or C-peptide level at 120 min after an oral glucose tolerance test as clustering variables.9 However, they were not measured in our study. Third, due to a lack of follow-up measurements of the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), the incidence of CKD was only determined by the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and medical history. Fourth, the clustering analysis was based on well-known biomarkers associated with T2DM. Other risk factors such as behavioral factors (smoking status, healthy diet score, and physical activity), genetic factors (polygenic risk score for T2DM), or family history of diabetes were not considered. Finally, the generalizability of our findings was limited to Chinese adults older than 40. The prevalence of prediabetes was also high in children and adolescents28; future research may explore the subphenotypes of prediabetes among them to identify the differences from adults.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Software and algorithms | ||

| R version 4.0.3 | R-Project | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| STAR Methods. Consensus clustering analysis: R package ConsensusClusterPlus version 1.62.0 | Bioconductor | https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ConsensusClusterPlus.html |

| STAR Methods. K-means cluster analysis: R package fpc version 2.2-9 | R Cran | http://mirrors.ustc.edu.cn/CRAN/ |

| Biological samples | ||

| Serum and urinary samples of the participants | 4C BioBank | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yufang Bi (byf10784@rjh.com.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Study design

The 4C study was a nationwide, multicenter, prospective, population-based study which was designed to examine the relationship between glycemic parameters and clinical outcomes, including diabetes, CVD, and cancer. The study design of the 4C Study has been described in detail previously.12 From 2011 to 2012, a total of 193,846 adults aged over 40 were recruited from 20 communities located at different geographical regions in mainland China. A comprehensive set of questionnaires, clinical measurements, and laboratory examinations were carried out at the baseline visit. During 2014–2016, all participants were invited to attend an in-person follow-up visit and the same protocol for investigation was used. The study protocol and informed consent were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital affiliated to the Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. All participants signed the written informed consent.

Data collection

Data were collected from the local hospitals or community clinics at the baseline visit. Trained technicians used a standardized questionnaire to collect participantsˈ demographic characteristics (age, gender, and education), dietary and lifestyle risk factors (including smoking status, alcohol drinking status, physical activity level, healthy diet score, and nighttime sleep duration), and medical history by personal interview. Body weight, height, and waist circumference, and blood pressure were measured by the trained staff. Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast of at least 10 h and the morning urine was also collected. The participants undertook a standard 75 g oral glucose tolerance test and post-load blood samples were collected at 2 h. All participants underwent measurements for FPG, 2 h PG, and HbA1c, TG, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-c), HDL-c, AST, ALT, GGT, urinary albumin, and urinary creatinine. The HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, and urine ACR were calculated. At the follow-up visit, the information on incident diseases and blood samples were collected, the FPG, 2 h PG, HbA1c, and serum creatinine were tested using the same protocol. Details of specimen processing and data collection were described in Methods S1.

Method details

Definitions of prediabetes

Prediabetes was defined according to the American Diabetes Association 2010 criteria,1 i.e. in participants without diabetes, FPG between 5.6 mmol/L to 6.9 mmol/L, or 2 h PG between 7.8 mmol/L to 11.0 mmol/L, or HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4%.

Ascertainment of incident outcomes

Information on the incident diabetes, CKD, and CVD was collected at the follow-up visit. Diabetes was defined as FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L, 2 h PG after a 75g glucose load ≥11.1 mmol/L, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or clinically ascertained diabetes (from a diagnosed history, or taking antidiabetic medications).1 The eGFR was calculated using the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.29 The composite outcome of CKD included incident kidney failure requiring dialysis or replacement therapy, death due to renal causes, decline in eGFR defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at follow-up or a certain drop in eGFR category (from eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline to eGFR in 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2 at follow-up) accompanied by a 25% or greater reduction in eGFR from baseline.30,31 Decline in eGFR was calculated as (eGFR at baseline - eGFR follow-up)/eGFR at baseline×100%. Major CVD events in the present study included the first nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalization or treatment for heart failure that occurred during follow-up, and cardiovascular death. The occurrence of nonfatal CVD events was recorded and supporting medical documents were collected. Information on vital status and clinical outcomes was also collected from the local death and disease registries of the National Disease Surveillance Point System and the National Health Insurance System. Two members of the 4C Morbidity and Mortality Adjudication Committee independently adjudicated each clinical event.

Quantification and statistical analysis

We used a forward stepwise logistic regression model to select the set of most important biomarkers that were independently associated with T2DM based on the collected anthropometric measurements and biochemical detection. The remaining variables with all p < 0.05 were used as clustering variables, including BMI, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), FPG, 2 h PG, HbA1c, HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, TG, HDL-c, ALT, AST, and GGT. Clustering analysis was done on values centered to a mean value of 0 and an SD of 1. Participants with outlier variables (absolute standardized levels >5) were excluded from the clustering procedure.

We applied a two-step clustering strategy, in which the first step estimated the optimal number of clusters by using consensus clustering analysis (Methods S2).32 In the second step, we applied K-means clustering specifying six clusters to the overall participants, and each participant was assigned to a unique cluster. K-means clustering was done with a K value of 6 using the kmeansruns function (runs = 100) in the ‘fpc’ package in R (version 4.0.3). To assess the cluster stability, we used bootstrap to perform 500 times random resampling of the overall data and the Jaccard similarities of the original clusters to the most similar clusters in the resampled data are computed. The computation was conducted with the clusterboot function from the ‘fpc’ package.33 Generally, stable clusters should yield a Jaccard similarity of greater than 0.75.33 According to the cluster methods published by Ahlqvist et al.23 and Zou et al.,34 we applied the gender-specific cluster analysis among participants with prediabetes at baseline and progression to T2DM at follow-up based on five variables collected at follow-up, including age at diagnosis, BMI, FPG, HOMA-IR and HOMA-β.

Data are presented as the mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or proportion (%). The comparison of mean values between clusters used ANOVA analysis. Skewed data were log-transformed before analysis. There were 15 times pairwise comparisons among 6 clusters and to account for multiple group comparisons, Bonferroni correction was applied with p < 0.003 (0.05/15) as statistical significance. We also calculated the Cohenˈs effect size (d) to indicate the standardised difference between the two means by removing any influence from the study sample size.35 The magnitude of the size effect was evaluated using the following cut-off points for classification: small: d = 0.20–0.49; medium: d = 0.50–0.79; large: d ≥ 0.80. The cohenˈs d was obtained using the cohen.d function from the ‘effsize’ package in R (version 4.0.3).

The diagnoses of most T2DM and CKD cases were based on the blood glucose and serum creatinine testing at the same time during the baseline and follow-up visits, the exact time of the incident T2DM and CKD was not available. The cumulative incidences of T2DM and CKD using the number of incident cases divided by the number of participants at risk. We compared the incidence of T2DM and CKD at follow-up between baseline clusters using logistic regression. The frequencies of endpoints related to CVD were calculated as the number of events divided by person-years of observation censored at the date of event occurrence, death, or follow-up visit, whichever came first. Adjusted Cox proportional hazard models were used and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the risks for incident CVD by clusters. Odds ratios (ORs) (95%CI) and HRs (95%CI) of model 1 were adjusted for age and gender, and model 2 were adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, drinking tea, healthy diet score, physical activity, family history of diabetes, nighttime sleep duration, systolic blood pressure, currently taking antihypertensive medication, and taking lipid-lowering agents. To validate the reliability of the analysis, we also performed clustering analysis using the same method and variables collected at the follow-up examination among the participants diagnosed as prediabetes at follow-up. Another sensitivity analyses were performed by conducting a K-means clustering analysis among the baseline participants with normoglycemia and those with prediabetes, and the risks of diseases were also compared by clusters. All analyses were done using R (version 4.0.3).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81970728, 81970691, 91857205, 82088102, 81930021, 81900741, and 82170819), the Shanghai Medical and Health Development Foundation (grant no. DMRFP_I_01), the Shanghai Outstanding Academic Leaders Plan (grant no. 20XD1422800), the Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (grant no. SHDC2020CR3064B, SHDC2020CR1001A), National Top Young Talents' program (Dr. Yu Xu) Innovative research team of high-level local universities in Shanghai, and the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (Grant Nos. 20Y11905100 and 19MC1910100).

Author contributions

R.Z., J.L., M.L., Y.X., Y.B., and W.W. conceived and designed the study. R.Z., J.L., M.L., and Y.X. analyzed the data. R.Z. and J.L. drafted the manuscript. M.L., Y.X., and Y.B. revised the manuscript. T.W., Z.Z., M.X., Y.C., M.D., D.Z., X.H., T.Z., X.G., L.C., Y.H., G.Q., Y.L., Q.W., L.C., L.S., R.H., X.T., Q.S., X.Y., Y.Q., G.C., Z.G., G.W., F.S., Z.L., Y.C., Y.Z., C.L., Y.W., S.W., T.Y., Q.L., Y.M., and J.Z. collected the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors agreed to be held accountable for all aspects of this work and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 1, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.100958.

Contributor Information

Weiqing Wang, Email: wqingw61@163.com.

Jieli Lu, Email: jielilu@hotmail.com.

Yufang Bi, Email: byf10784@rjh.com.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The patient-level data reported in this study cannot be deposited in a public repository. No new code was generated in this study. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:S62–S69. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menke A., Casagrande S., Geiss L., Cowie C.C. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1021–1029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y., Teng D., Shi X., Qin G., Qin Y., Quan H., Shi B., Sun H., Ba J., Chen B., et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m997. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabák A.G., Herder C., Rathmann W., Brunner E.J., Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379:2279–2290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindström J., Louheranta A., Mannelin M., Rastas M., Salminen V., Eriksson J., Uusitupa M., Tuomilehto J., Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3230–3236. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong Q., Zhang P., Wang J., Ma J., An Y., Chen Y., Zhang B., Feng X., Li H., Chen X., et al. Morbidity and mortality after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance: 30-year results of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:452–461. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30093-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piller C. Dubious diagnosis. Science. 2019;363:1026–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.363.6431.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerstein H.C., Santaguida P., Raina P., Morrison K.M., Balion C., Hunt D., Yazdi H., Booker L. Annual incidence and relative risk of diabetes in people with various categories of dysglycemia: a systematic overview and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007;78:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner R., Heni M., Tabák A.G., Machann J., Schick F., Randrianarisoa E., Hrabě de Angelis M., Birkenfeld A.L., Stefan N., Peter A., et al. Pathophysiology-based subphenotyping of individuals at elevated risk for type 2 diabetes. Nat. Med. 2021;27:49–57. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang T., Lu J., Shi L., Chen G., Xu M., Xu Y., Su Q., Mu Y., Chen L., Hu R., et al. China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort Study Group China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort Study Group. Association of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction with incident diabetes among adults in China: a nationwide, population-based, prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng R., Li M., Xu M., Lu J., Wang T., Dai M., Zhang D., Chen Y., Zhao Z., Wang S., et al. Chinese adults are more susceptible to effects of overall obesity and fat distribution on cardiometabolic risk factors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;106:e2775–e2788. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu J., He J., Li M., Tang X., Hu R., Shi L., Su Q., Peng K., Xu M., Xu Y., et al. Predictive value of fasting glucose, postload glucose, and hemoglobin A1c on risk of diabetes and complications in Chinese adults. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1539–1548. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiao Q., Nakagami T., Tuomilehto J., Borch-Johnsen K., Balkau B., Iwamoto Y., Tajima N., International Diabetes Epidemiology Group. DECODA Study Group Comparison of the fasting and the 2-h glucose criteria for diabetes in different Asian cohorts. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1470–1475. doi: 10.1007/s001250051557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaziri N.D. HDL abnormalities in nephrotic syndrome and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016;12:37–47. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson M.B. Metformin should not be used to treat prediabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1983–1987. doi: 10.2337/dc19-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandie Shaw P.K., Berger S.P., Mallat M., Frölich M., Dekker F.W., Rabelink T.J. Central obesity is an independent risk factor for albuminuria in nondiabetic South Asian subjects. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1840–1844. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Artunc F., Schleicher E., Weigert C., Fritsche A., Stefan N., Häring H.U. The impact of insulin resistance on the kidney and vasculature. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016;12:721–737. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill M.A., Yang Y., Zhang L., Sun Z., Jia G., Parrish A.R., Sowers J.R. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. 2021;119:154766. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor R. Type 2 diabetes and remission: practical management guided by pathophysiology. J. Intern. Med. 2021;289:754–770. doi: 10.1111/joim.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vistisen D., Kivimäki M., Perreault L., Hulman A., Witte D.R., Brunner E.J., Tabák A., Jørgensen M.E., Færch K. Reversion from prediabetes to normoglycaemia and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: the Whitehall II cohort study. Diabetologia. 2019;62:1385–1390. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4895-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallar A., Dagogo-Jack S. Regression from prediabetes to normal glucose regulation: state of the science. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020;245:889–896. doi: 10.1177/1535370220915644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis J.M., Shields B.M., Henley W.E., Jones A.G., Hattersley A.T. Disease progression and treatment response in data-driven subgroups of type 2 diabetes compared with models based on simple clinical features: an analysis using clinical trial data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:442–451. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahlqvist E., Storm P., Käräjämäki A., Martinell M., Dorkhan M., Carlsson A., Vikman P., Prasad R.B., Aly D.M., Almgren P., et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:361–369. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B., Kengne A.P., Ali M.K. Issues in defining the burden of prediabetes globally. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2018;18:105. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1089-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman W.H., Hoerger T.J., Brandle M., Hicks K., Sorensen S., Zhang P., Hamman R.F., Ackermann R.T., Engelgau M.M., Ratner R.E., et al. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005;142:323–332. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B., Selvin E. Prediabetes and what it means: the epidemiological evidence. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2021;42:59–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Prato S. Heterogeneity of diabetes: heralding the era of precision medicine. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:659–661. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han C., Song Q., Ren Y., Chen X., Jiang X., Hu D. Global prevalence of prediabetes in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes. 2022;14:434–441. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H., Zhang Y.L., Castro A.F., 3rd, Feldman H.I., Kusek J.W., Eggers P., Van Lente F., Greene T., et al. CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2013;3:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundqvist H., Heikkala E., Jokelainen J., Russo G., Mikkola I., Hagnäs M. Association of renal function screening frequency with renal function decline in patients with type 2 diabetes: a real-world study in primary health care. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23:356. doi: 10.1186/s12882-022-02979-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monti S., Tamayo P., Mesirov J., Golub T. Consensus clustering: a resampling-based method for class discovery and visualization of gene expression microarray data. Mach. Learn. 2003;52:91–118. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hennig C. Cluster-wise assessment of cluster stability. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007;52:258–271. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou X., Zhou X., Zhu Z., Ji L. Novel subgroups of patients with adult-onset diabetes in Chinese and US populations. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:9–11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenthal J.A. Qualitative descriptors of strength of association and effect size. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1996;21:37–59. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The patient-level data reported in this study cannot be deposited in a public repository. No new code was generated in this study. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.