Abstract

Black women have always been likened to being a less physically active group compared to women of other races/ethnicity, with reports of a high prevalence of obesity and other cardiometabolic diseases among them. The purpose of this study is to examine the health benefits of physical activity on women of color, as well as barriers that inhibit their participation.

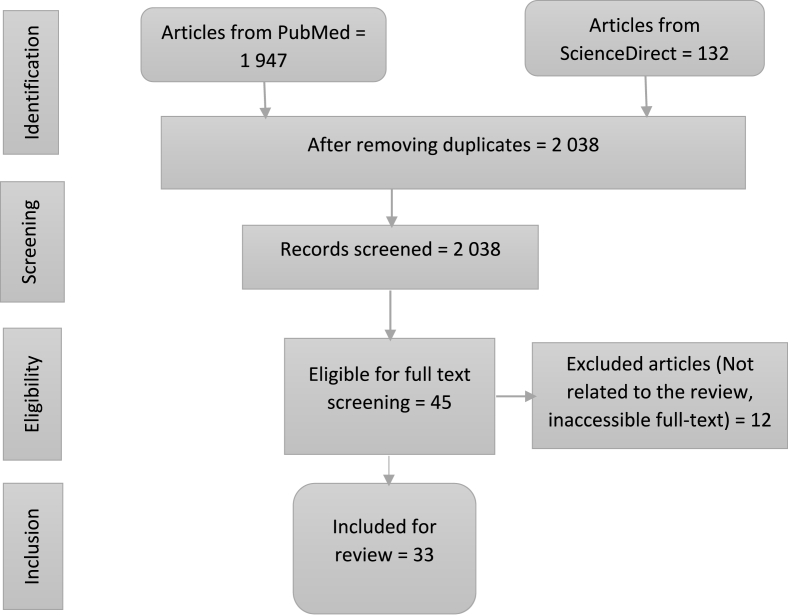

We searched PubMed and Web of Science databases for relevant research articles. Included articles were: Published in the English Language from 2011 to February 2022; conducted predominantly on black women, African women, or African American women. Articles were identified, screened, and data extracted following the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

The electronic search produced 2 043 articles, and 33 articles were reviewed after meeting the inclusion criteria. 13 articles focused on the benefits of physical activity while 20 articles addressed the barriers to physical activity. It was found that physical activity has various benefits for black women participants but they are being hindered from participation by some factors. These factors were grouped into four themes, namely Individual/Intrapersonal barriers, Socio-economic barriers, Social barriers, and Environmental barriers.

Various studies have examined the benefits and barriers of physical activity among women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, but there have been very few studies of African women, with the majority focusing on one geographical area. In addition to exploring these benefits and barriers, this review offers recommendations on the areas researchers should focus on to promote physical activity in this population.

Keywords: Physical activity, Barriers, Benefits, Black women, African women, African American women

List of abbreviations and definitions

- CMDs

Cardiometabolic diseases

- CVDs

Cardiovascular diseases

- QOL

Quality of life

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- HbA1c

Glycosylated Hemoglobin

- SI

Insulin Sensitivity

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HIIT

High Intensity Interval Training

- IL-7

Interleukin-7

- TNF

Tumor Necrotic Factor

- IFN

Interferon

- LDL

Low Density Lipoprotein

- AUC

Area under curve

- HR

Heart Rate

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- CRF

Cardiorespiratory Fitness

- USA

United States of America

- N/A

Not applicable

Introduction

For ages, physical activity has been considered an elixir of life, which is protective of various non-communicable diseases such as cardiometabolic diseases (CMDs) and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and also improves one’s quality of life (QOL). Physical activity is defined as any movement of the body caused by skeletal muscles that necessitate the expenditure of energy,1 and it is distinguished by its modality, frequency, intensity, duration, and practice setting.2

Due to the increasing rate of industrialization and the emergence of sophisticated technology, there is a relative decrease in physical activity and an overwhelming increase in sedentary lifestyle, chronic disease morbidity, and mortality, hence resulting in recommendations and guidelines for intentional participation in physical activities.3,4 People are classified as physically active when they meet the prescribed requirements for intensity and min of physical activity, and as inactive if they do not meet the requirements. Adults aged 18–64, are expected to engage in at least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week.1 Combining moderate- and vigorous-intensity exercise have significant health benefits,1 with men being more likely to follow through than women.5

There are various reports from researchers and international bodies regarding the benefits of physical activity for women.1 Physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum is associated with a reduced risk of pre-eclampsia, hypertension, gestational diabetes, excessive gestational weight gain, and delivery complications, and there are also fewer new-born complications, with no adverse effects on birthweight, and no increase in the risk of stillbirth.1 Interestingly, there is a link between sexual dysfunction, depression, and physical activity in women. Women with depression/anxiety symptoms have a substantially greater incidence of diminished sexual desire and a tendency toward a higher prevalence of dyspareunia than women without anxiety symptoms6 with physical activity having antidepressant-like effects on these depression symptoms7 and also strongly linked to improved overall sexual performance.8 Menopausal women had substantial decreases in menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, sweating, anxiety, sleep difficulties, irritability, and negative moods following a 24-week exercise program.9 Among healthy people, physical activities have also been linked to improved sleep and fewer sleep disruptions by several studies.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Improved sleep quality was highlighted in pregnant women that participated in a randomized clinical trial of physical activity.18 However, in contrasting reports, physical activity was not closely linked with sleep quality and length in pregnant women.19,20

Notwithstanding the enormous benefits of physical activity, Black/African-American women are more likely to be less physically active than their white counterparts. About 38% of non-Hispanic black women against 23% non-Hispanic white women had reported little or no participation in leisure-time physical activity.21 As a consequence, this population is burdened with high risk and prevalence of chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases that are often linked to physical inactivity.22 Considered the fourth leading risk of death worldwide, physical inactivity accounts for 6% of all deaths, and it is thought to be responsible for roughly 21%–25% of breast and colon cancer cases, 27% of diabetes cases, and about 30% of ischemic heart disease cases.23 This shows the need for an intervention that is specifically focused on this population’s needs, and has the potential to effectively reduce these physical activity-related health burdens among black women.

Studies have shown that several barriers, including individual, interpersonal, social, and environmental influences limit women’s participation in physical activity.24, 25, 26 Given these factors, it is not surprising that many past interventions have been unsuccessful and unsustainable in addressing the low prevalence of physical activity. Interventions established with a clear understanding and explanation of these limiting factors and substantial stakeholder involvement in developing solutions are mostly going to be effective.27 It is important to have a comprehensive outlook on the cultural, social, and contextual elements that affect physical activity behavior.26 Our systematic review aims to assess the factors that inhibit Black/African-American women from participating in physical activity and the benefits they derive as regular participants. Identifying these barriers is crucial to developing, not only an effective intervention but also a sustainable one. Also, examining the specific benefits of physical activity and the potential to lessen the burdens of chronic diseases in this population will help to promote the adoption and adherence to health promotion activities.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted. We searched PubMed and Web of Science databases for relevant research articles. Search keywords included physical activity, exercise, barriers, benefits, black women, and African American women.

Included studies were: a) published in the English Language; b) published between 2011 and 2022; c) conducted predominantly on black women or African American women. Studies were excluded if they were: a) Review articles; b) conducted with samples from ethnic groups other than black women or African American women; c) conducted in/with subgroups with special disease conditions which could interfere with or limit engagement in physical activity.

An electronic search was performed by two reviewers. Duplicate articles were removed using the Mendeley reference tool. Title and abstract screening and selection were conducted by all four reviewers independently. Further screening of the full text of selected articles was performed by the same reviewers. The dialogue was used to reach a consensus following any disagreement on article selection and inclusion. A manual search of the reference list of included articles was also conducted by all the reviewers to identify relevant articles not found in the online search.

We used qualitative synthesis to extract data. Articles were grouped into two – barriers and benefits groups. Three reviewers worked independently to synthesize relevant information. The author’s information, year of study, study settings, key findings and other relevant data addressing the research objectives were extracted. We categorized the identified barriers into four groups – Intrapersonal/Individual barriers (such as body image, and hair concerns); Social Barriers (such as lack of role models, and peer pressure); Socio-economic barriers (such as cost, lack of exercise resources); and Environmental barriers (such as weather, neighborhood safety).

The procedures are reported in the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)28 flow chart. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the study selection process.

Results

The initial electronic search produced 2 043 articles and was reduced to 2 038 after duplicates were removed. Following title and abstract screening, 45 articles were selected for full-text screening. After the screening of full-text, 33 articles met all inclusion criteria for this review. 13 articles focused on the benefits of physical activity, while 20 articles addressed the barriers to physical activity.

Among the Benefit studies, 7 were randomized controlled trials, 2 qualitative studies, 2 prospective studies, 1 case-control study, and 1 intervention study without control. The sample size ranges from 15 to 832 and participants were between 18 and 61 years across all studies. Of the 13 studies, 8 were conducted in the United States among African American women, 4 in South Africa among the Black African women, and 1 study did not provide information about the location. Table 1 presents the summary of the studies and the key findings.

Table 1.

Summary of studies characteristics and findings on the benefits of physical activity.

| Study | Study Design | Settings | Sample Size | Mean Age of Participants | Exercise Program | Key Findings. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sealy-Jefferson et al.29 | Retrospective, Prospective Cohort Study | Baltimore, Maryland | 832 | 23 years old | Walking for a purpose or stair climbing for 30 min daily | The rate of preterm delivery (PTD) was 16.7%. A marked decrease in the prevalence of PTD in women who walked for a purpose for more than 30 min. |

| Joseph et al.30 | Intervention study | Arizona State University, USA | 15 | 19–30 years | A 3-month 30–60 min moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity | BMI significantly decreased over the study period (p = 0.034), reflected by a marginal decrease in body weight (p = 0.057). Bone marrow density significantly increased over the 3-month study (p = 0.011), but cortical density remained stable (p = 0.211). Marginal significant increase in muscle density (p = 0.053). |

| Ingram et al.31 | Qualitative Exploratory design | Chicago, USA | 51 | Mean Age = 54 years | A 12-month (6 months adoption, 6 months maintenance) Walking Intervention | Weight loss, Improved body shape, Stress reduction, Avoiding diabetes, Controlling the blood pressure. |

| Gradidge et al.32 | Randomized Controlled Trial | University of Venda, Limpopo province, South Africa. |

115 | ≥18 years | 12-week walking intervention | BMI, waist circumference, and blood pressure were significantly reduced. |

| Hornbuckle et al.33 | Randomized controlled study | Florida State University, USA | 44 | 39–61 years | Lifestyle walking program combined with resistance training for 12 weeks. | Significant reduction in waist circumference, total fat mass, gynoid fat mass, and percent total body fat. Significant decrease in HbA1c and mean blood glucose calculated from HbA1c. Significant increase in fibrinogen level |

| Hornbuckle et al.34 | Randomized controlled (Pilot Intervention) study | Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA | 27 | 20–40 years | 16-week high-intensity interval training (treadmill exercise involving walking and running) | A significant decrease in waist circumference, which is an important cardiometabolic risk factor. A significant time effect for steps where HIIT increased steps/day |

| Wharton et al.35 | Phase 1 Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials | Atlanta, Georgia | 34 | 45+ years/ (59.7 ± 8.13) years | 20 classes of a 12 week Adapted Tango dance session which lasted 1.5 h long | Notable reduction in inflammatory cytokines, including IL-7, TNF-, IFN-y, and MCP-1. Improved cognition, strength, and balance in participants. |

| Sheppard et al.36 | Case-control study | Washington, DC metro area | N/A | 52.42–57.63 years | Walking for exercise and vigorous physical activity (running, aerobics, etc.) | 2 h/week of vigorous physical activity was found to be protective against breast cancer in postmenopausal women. A 64% reduction in risk of breast cancer. |

| Mendham et al.37 | Randomized control trial | N/A | 45 | 20–35 years | 12-weeks, 4 days per week, 40–60 min aerobic and resistance training (dancing, running, skipping, and stepping at a moderate-vigorous intensity, 75%–80% peak heart rate) | A small but considerable reduction in body mass index and increased oxygen consumption The increased mitochondrial function associated with a decrease in body fat, Improved SI with reduced gynoid fat. |

| Evans.38 | Qualitative (Ethnographic) study | Southern rural county | 20 | 40–60 years | N/A | The majority of women believe that exercise keeps blood flow to the heart and makes the heart strong. |

| Mathunjwa et al.39 | Prospective Experimental Study | University of Zululand, South Africa | 60 | Mean Age = (25 ± 5) years | A 10-week exercise program of 30 sessions of Tae-bo, 60 min per day for 3 days a week, moderate intensity for the first five weeks and high intensity for the last five weeks. | Effective reduction in risk factors associated with cardiometabolic disease in the students that are obese or overweight. Improvement in BMI, weight, waist circumference, resting heart rate and resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure, LDL-C, HDL-C, and total cholesterol |

| Fortuin-de Smidt et al.40 | Randomised controlled trial | Cape Town, South Africa | 45 | 20–35 years | 12-weeks of aerobic and resistance training exercises | Improved Cardiorespiratory fitness, total AUC of glucose, and Insulin sensitivity. A small reduction in body weight and gynoid fat. |

| Clamp et al.41 | Randomized Controlled study | Western Cape, South Africa | 35 | 20–35 years | A 12-week exercise session which includes aerobic and resistance training at a vigorous intensity (> 75% peak heart rate, HRmax) advancing from 40 to 60 min per day for 4 day in a week | Relative reduction in gynoid fat mass in response to a 12-week combined aerobic and resistant exercise. There were also improved CRF with higher fat oxidation rate and lower resting carbohydrate oxidation rates in steady-state and baseline respectively. |

aBMI: Body Mass Index; HbA1c: Glycosylated Hemoglobin; SI: Insulin Sensitivity; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HIIT: High Intensity Interval Training; IL-7: Interleukin-7; TNF: Tumor Necrotic Factor; IFN: Interferon; LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein; AUC: Area under curve, HR: Heart Rate; MCP-1: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; CRF: Cardiorespiratory Fitness.

The Barrier studies included 8 cross-sectional studies, 5 qualitative studies, 3 case-control studies, 2 randomized controlled trials, and 2 observational studies. Eighteen of the studies were located in the United States, 1 was done in South Africa, and 1 did not provide location information. The sample size across the studies ranges from 12 to 1 558 and included participants from 13 years and above. The study characteristics and the key findings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of studies characteristics and findings on the barriers to physical activity.

| Study | Study Design | Settings | Sample Size | Mean Age of Participants | Key Findings. | Barrier themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baruth et al.42 | Case-control study | Columbia, South Carolina | 28 | 20–50 years | Injuries and health conditions; Issues related to body size; Competing demands on their time and lack of energy Lack of motivation; Unavailability of exercise partners; Rude and disrespectful comments by people. Lack of access to facilities; High cost of a gym membership. |

Intrapersonal barriers Social barriers Socio-economic barriers |

| Carr et al.43 | Randomized controlled trial | North Carolina | 234 | 50 years and above | Lack of willpower; General sense of role overwhelm; Haircare and maintenance. Cost; Lack of exercise resources. |

Intrapersonal barriers. Socio-economic barriers |

| Mama et al.44 | Case-control | Harris, Houston and Travis Country, Austin, Texas | 164 | 25–60 years | Body composition and body image; Motivational readiness for weight loss Environmental changes. |

Intrapersonal barriers. Environmental barriers |

| Huebschmann et al.45 | Cross-sectional study | Metropolitan Denver area | 51 | 19–73 years | Sweating out my hairstyle; Drying effects on hairstyle; Lack of self-discipline; I am too exhausted at the end of the day Lack of money; Lack of equipment. |

Intrapersonal barriers. Socio-economic barriers. |

| Joseph et al.46 | Case-control | Phoenix, Arizona | 23 | 24–49 years | Perspiration while performing Physical Activity; Maintaining a work-appropriate and socially acceptable hairstyle that is convenient for physical activity; Social comparison to women of other races/ethnicities. | Intrapersonal and Social barriers. |

| Adamus-Leach et al.47 | Cross-sectional study | Houston and Austin, Texas | 388 | 20–65 years | Individual Income status Perception of neighborhood environment |

Socio-economic barrier Environmental barrier |

| Hall et al.48 | Cross-sectional survey study | Winston-Salem, North Carolina | 103 | 21–60 years | Hair concerns and maintenance | Intrapersonal barriers. |

| Gaston et al.49 | Cross-sectional study | Detroit, Michigan | 1 558 | 23–35 years | Hair product use/maintenance | Intrapersonal barriers. |

| Robinson & Wicks50 | Cross-sectional study | Alabama | 19 | 21–60 years | Type of employment and h worked. Religiosity. |

Intrapersonal barriers. Social barrier. |

| Scott et al.51 | Observational study: Use of self-administered questionnaires | Not stated | 113 | Middle-aged. Mean age: 51.3 years | Not enough time; No knowledge of exercise techniques. No one to exercise with me. Lack of access to a gym and childcare Unsafe environment. |

Intrapersonal barriers. Social barrier. Environmental barrier. |

| Gothe & Kendall52 | Qualitative research (with 3 Focus groups) | Detroit metro area and surrounding urban communities | 20 | Between 55 and 75 years, mean age: age = (63.15 ± 4.5) years | Time; physical health and age-related limitations Peer pressure and family responsibilities Weather and poor neighborhood condition |

Intrapersonal barriers Social barriers. Environmental barriers |

| James et al.53 | Cross-sectional survey study | North-central Florida, USA | 413 | Mean age: (35.63 ± 14.72) years | Busy lifestyle and not having enough time; Too much hair care Expensive gym membership; No one to exercise with; Living in an unsafe neighborhood |

Intrapersonal barrier. Socio-economic; Social and Environmental barriers. |

| Ingram et al.31 | Qualitative exploratory design with focus group methodology (4 focus groups) | Chicago | 33 | 44–69 years. Mean age: 54 years | Family and work responsibilities; Musculoskeletal problems and weight issues associated with walking. Lack of role models within the community. Weather; Neighborhood safety. |

Intrapersonal barrier. Social barrier Environmental barrier. |

| Jackson et al.54 | Cross-sectional descriptive study | North Omaha | 47 | 19 years and above | Obesity; Fatigue; Haircare concern; Family and friends; Lack of time. Social support for physical activity. |

Intrapersonal barrier. Social barrier. |

| Zenk et al.55 | Correlational, observational research design | Metropolitan Chicago | 97 | 25–64 years | Affect (feelings). Poor weather. |

Intrapersonal barrier. Environmental barrier. |

| Schoeny et al.56 | Randomized controlled trial | Chicago, Illinois area | 284 | 40–65 years | Physical and psychological health; Pain; BMI; Perceived walkability; Children in the household; Employment. Neighborhood characteristics (Assault/battery rate). |

Intrapersonal barrier. Environmental barrier. |

| Tenfelde et al.57 | Qualitative Research (Focus group) study | The urban Midwest, Chicago, USA | 22 | 18 years and above | Access to Yoga classes within the community; Location of classes; Quality of instruction. The high cost of yoga classes |

Intrapersonal barrier Socio-economic barrier. |

| Kinsman et al.58 | Qualitative focus group study | Agincourt sub-district of rural Mpumalanga province, north-eastern South Africa, |

51 | 13–19 years | Body image ideals. Poverty and associated social stigma; Gender bias in accessing facilities and competitions; Parental interference due to social violence. |

Intrapersonal barrier. Social and Socio-economic barriers. |

| Alvarado et al.59 | Population-based cross-sectional study | Barbados | 17 | 25–35 years | Laidback mentality; Lack of opportunity to walk to jobs, grocery stores, etc. due to a distant residential area. Gender norms; Limited indoor space for home exercise; Limited access to group/gym exercise |

Intrapersonal barrier. Social barriers. |

| Walker.60 | Qualitative Research Design (using grounded theory approach) | Las Vegas, US | 12 (6 mothers, 6 daughters) | Women 42–50 years; Girls 12–17 years | Body image perception; Lack of interest, knowledge, time, and transportation Lack of physical activity history/ motivation; peer pressure; Fear of sexual stereotypes; Racial stereotypes and sports Weather. |

Intrapersonal barriers Social barriers Environmental barrier |

Discussion

Physical activity is an important public health strategy to lower the risk of obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases prevalent in African women. Several studies have highlighted the enormous benefits of being physically active among women. Unfortunately, the majority of these studies are carried out among White women, with limited data on Black women. However, due to barriers that may be categorized into intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, socio-economic, and environmental barriers, black women rarely participate in physical activity. In this systematic review, we examined recent studies on the benefits of physical activity for black women, as well as barriers to engaging in physical activity among this population.

Benefits of physical activity

The current review found that moderate to high-intensity exercise, including walking, running, yoga, weightlifting, and aerobic activities are strongly associated with improved BMI, waist circumference, body weight, body shape, body satisfaction, cardiovascular health, and general well-being. Subjects who participate more often in vigorous physical activity are more likely to feel more confident in their body, increase the number of steps per day and engage in other activities. Studies also show that physical activity has a beneficial effect on insulin sensitivity in Black women who are obese. Although the effect observed in the study is minimal compared to similar previous studies in other populations.

Most of the studies in our review utilized randomized controlled trial study design.32, 33, 34, 37, 40, 41 There is inconsistency in the evidence presented in some of the studies. One study found no association between exercise adherence and change in body composition. This contradicts most studies suggesting beneficial effects on body composition with higher-intensity physical activity over a longer duration of time. However, this study was conducted in a small cohort of African American women with no control group and less adherence rate. These may have introduced bias and also limit its generalization. Hence, to solidify the evidence, there is a need for further investigation with a larger sample size.

A randomized controlled trial is the standard for effective clinical research and outcome measurement61 and should be utilized to generate more evidence in the literature. However, in this understudied population, other study designs such as qualitative studies are needed to better understand the views of black women on the benefits they get from engaging in physical activity other than the effects from objective data. This would serve as a motivating factor to encourage more participation of black women in an exercise program. Also, the majority of the studies were conducted on African American women that are overweight or obese. The few studies conducted in Africa were focused on one location, presenting the need for studies including a more robust representative of black African women.

Studies that examined walking exercise intervention suggest that walking may reduce body mass index, waist circumference, total fat mass, and other cardiovascular disease risk factors.32, 33, 34,31 However, most of the studies were conducted within 8–12 weeks period and with a small sample size. Across all studies, subjects did not achieve the 10 000 steps per day goal. To improve cardiovascular health in obese individuals through a walking program, 10 000 steps per day is usually recommended.62,63 However, most subjects in walking exercise program achieve this goal after a long time of continuous walking exercise.64 This implies that an intervention program targeted at this population should be designed to last for a longer period than the usual 8–12 weeks that most researchers use.

The included studies utilized a small sample size which is a major limitation. To increase the statistical power and generalize findings, future studies should utilize a larger sample size.65 Another limitation found in the studies is a low adherence rate and loss of follow-up. A study had a more than 70% dropout rate in one of the groups of the study despite drawing up measures to control for it.34 On average, around 45% of participants do not adhere to exercise intervention programs, and these large dropout rates have crippled the success of physical activity interventions.66 Therefore, designing studies to examine the reasons for dropout, as well as providing effective measures to encourage adherence would be very helpful.

Barriers to physical activity

The Barrier studies in this review employed different measurement tools in cohorts of Black women to highlight the various barriers preventing women from engaging in physical activity.

The majority of the study was conducted among African women living in the United States of America (USA).42, 45, 46, 54, 56, 60 Studies on black women based in African countries are limited, prompting the need to diversify research in this area to African countries. All study design types examined one or more individual/intrapersonal barriers. However, some inconsistencies were observed among the studies examining all categories of barriers. Two quantitative studies identified a social barrier to a lack of exercise partners. No qualitative study evaluated this barrier to better understand the views and opinions of the subjects. A similar observation was made for Religiosity, Gender norms, and Peer pressure, as well as Musculoskeletal problems and weight issues associated with walking identified in one of the qualitative studies.

While most of these barriers are common among people of all races, intrapersonal and social barriers such as Body image perception, hair care concerns, gender norms, fear of sexual stereotypes, and family responsibilities are peculiar to African women. Black women are often characterized as having thick thighs, wide hips and shapes, broad shoulders, and most times are referred to as fat because of those physical attributes. These women become conscious of their looks and weight due to the cultural and social norms in their countries of residence.42,44 Low–income African Women who are overweight are conscious of their looks and they are sensitive to teasing from people when they exercise in public. This can impede initial attempts at behavior change, thereby short-circuiting progress. However, maintenance enhances self-efficacy that reinforces behavior change over time.44

Hair is considered an essential part of the beauty in African culture, thus priority is given to hair among black women. There seems to be an existing link between African-American women’s experiences, societal expectations about their lifestyles, and physical activity engagement. Black women’s hair is often evaluated against the standard of beauty because of the texture of their hair, thereby influencing their thought processes when trying to adopt a physically active lifestyle,60 therefore, hair maintenance concerns pose as a barrier to participation in physical activity as a result of concerns such as “Sweating out my hairstyle” and “Drying effects on the hairstyle” following a vigorous aerobic exercise. However, introducing styling techniques to minimize the effect of sweating while physically active and empowering women in trying a variety of protective styles will encourage and motivate women to participate more in physical activity.45,46

The prevalent rate of violence in black neighborhoods may explain some of the negative outcomes linked to the environmental barriers impeding black women’s participation in physical activity. It is unclear from the reports of the studies whether these black women enjoy engaging in exercise activities alone, which may raise the risk to personal safety. Group exercise participation may be advised, as participating in group dynamics-based physical activity programs may improve physical activity behavior67 and a sense of safety. Researchers should leverage these specific barriers to provide relevant interventions that will address these cultural related barriers among Africans.68

The present review had several limitations that should be noted. Only studies conducted exclusively on black women were included. This screen out studies with women of other races alongside black Africans, limiting the possibility of comparing the outcomes of interest and identifying those peculiar to African women. We also excluded studies that involved women with chronic diseases, special conditions, and geriatrics. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to such groups. Even though we conducted a manual search, we acknowledge that some studies relating to the benefits and barriers of physical activity in African women may have been unintentionally excluded in both the electronic and manual searches. Also, we utilized two databases to obtain data, possibilities exist that more important information, from other databases, addressing the research questions were omitted.

Despite all these limitations, this review will form the basis for future studies, most importantly, for designing interventions to promote physical activity in women of color. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to systematically review all study designs on the benefits and barriers of physical activity in African women.

Conclusion

There is a substantial amount of research on the benefits and barriers of physical activity among women of diverse races. In black women, only a few studies have been identified, with the majority focused on one geographical zone. While physical activity has defined benefits on obesity, cardiovascular health, hypertension, and other chronic diseases prevalent in black/African-American women, significant barriers such as body image perception, hair care concerns, gender norms, fear of sexual stereotypes, and family responsibilities particularly limit their involvement in physical activity. This comprehensive review highlights these benefits and barriers, as well as provides recommendations on the area researchers need to address to promote physical activity in this population. In designing effective interventions, the identified barriers and the existing gaps in the literature should be taken into consideration. Again, research should be diversified to reach the underserved groups in Africa. There is also a need to incorporate the motivators, predictors and barriers in future interventions to successfully improve the physical activity behavior of African women.

Submission statement

This work has not been published previously or is under consideration for publication in any journal and if accepted, will not be published elsewhere. All authors have read and approved this manuscript for publication.

Authors’ contribution

A.C.N. and O.C.O conceived and designed the review protocol and performed the electronic search. A.C.N., O.C.O., A.O., and O.J.O. performed a manual search, screening, and data extraction; We drew lots to determine the co-first authorship order. Both A.C.N. and O.C.O. contributed equally and have the right to list their name first in their CV. All authors contributed in drafting the manuscript and approved the submitted work.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the Parg Network and its executives for giving us the platform and the opportunity to conduct this research. Special mentions include the Director – Chima Cyril Hampo, and Team leaders of the Health and Nutrition subgroup – Emmanuel Njoku and Kelechi Andrew, who offered a consistent follow-up to ensure the progress of the research.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. World Health Organization; 2020. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128.

- 2.Thivel D, Tremblay A, Genin PM, Panahi S, Rivière D, Duclos M. Physical activity, inactivity, and sedentary behaviors: definitions and implications in occupational health. Front Public Health. 2018;288:6. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jochem C, Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. In: Sedentary Behaviour Epidemiology. Leitzmann MF, Jochem C, Schmid D, editors. Springer; Cham: 2018. Introduction to sedentary behaviour epidemiology; pp. 3–29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine JA. Sick of sitting. Diabetologia. 2015;58(8):1751–1758. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423–1434. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnatz PF, Whitehurst SK, O’Sullivan DM. Sexual dysfunction, depression, and anxiety among patients of an inner-city menopause clinic. J Wom Health. 2010;19(10):1843–1849. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinas PC, Koutedakis Y, Flouris AD. Effects of exercise and physical activity on depression. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180(2):319–325. doi: 10.1007/s11845-010-0633-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maseroli E, Rastrelli G, Di Stasi V, et al. Physical activity and female sexual dysfunction: a lot helps, but not too much. J Sex Med. 2021;18(7):1217–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karacan S. Effects of long-term aerobic exercise on physical fitness and postmenopausal symptoms with menopausal rating scale [Effets à long terme d’exercices de type aérobic sur la condition physique et la symptomatologie post-ménopausique] Sci Sports. 2010;25(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.scispo.2009.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kronholm E, Härmä M, Hublin C, Aro AR, Partonen T. Self-reported sleep duration in Finnish general population. J Sleep Res. 2006;15(3):276–290. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-2869.2006.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youngstedt SD. Effects of exercise on sleep. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24(2):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkinson G, Davenne D. Relationships between sleep, physical activity and human health. Physiol Behav. 2007;90(2–3):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urponen H, Vuori I, Hasan J, Partinen M. Self-evaluations of factors promoting and disturbing sleep: an epidemiological survey in Finland. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26(4):443–450. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King AC, Oman RF, Brassington GS, Bliwise DL, Haskell WL. Moderate-intensity exercise and self-rated quality of sleep in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;277(1):32–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540250040029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan SF, O’Connor GT, Quan JS, et al. Association of physical activity with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2007;11(3):149–157. doi: 10.1007/S11325-006-0095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherrill DL, Kotchou K, Quan SF. Association of physical activity and human sleep disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(17):1894–1898. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fogelholm M, Kronholm E, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Partonen T, Partinen M, Härmä M. Sleep-related disturbances and physical inactivity are independently associated with obesity in adults. Int J Obes. 2007;31(11):1713–1721. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Blanque R, Sánchez-García JC, Sánchez-López AM, Mur-Villar N, Aguilar-Cordero MJ. The influence of physical activity in water on sleep quality in pregnant women: a randomised trial. Women Birth. 2018;31(1):e51–e58. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borodulin K, Evenson KR, Monda K, Wen F, Herring AH, Dole N. Physical activity and sleep among pregnant women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010;24(1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-3016.2009.01081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loprinzi PD, Loprinzi KL, Cardinal BJ. The relationship between physical activity and sleep among pregnant women. Ment Health Phys Act. 2012;5(1):22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2011.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2019-2021. American Cancer Society. Accessed February 4, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2015. Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Heal United States; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2009. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. [Google Scholar]

- 24.James DCS, Pobee JW, Oxidine D, Brown L, Joshi G. Using the health belief model to develop culturally appropriate weight-management materials for african-American women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):664–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wendel-Vos W, Droomers M, Kremers S, Brug J, Van Lenthe F. Potential environmental determinants of physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8(5):425–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleury J, Lee SM. The social ecological model and physical activity in African American women. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;37(1-2):129–140. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly PJ, Lesser J, Cheng AL, et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial of an interpersonal violence prevention program with a Mexican American community. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(3):207–215. doi: 10.1097/fch.0b013e3181e4bc34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sealy-Jefferson S, Hegner K, Misra DP. Linking nontraditional physical activity and preterm delivery in urban african-American women. Wom Health Issues. 2014;24(4):e389–e395. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joseph RP, Casazza K, Durant NH. The effect of a 3-month moderate-intensity physical activity program on body composition in overweight and obese African American college females. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2485–2491. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2825-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingram D, Wilbur J, McDevitt J, Buchholz S. Women’s walking program for African American women: expectations and recommendations from participants as experts. Women Health. 2011;51(6):566–582. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.606357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gradidge PJ-L, Golele PN. Walking as a feasible means of effecting positive changes in BMI, waist, and blood pressure in black South African women. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18(4):917–921. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i4.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hornbuckle LM, Liu P-Y, Ilich JZ, Kim J-S, Arjmandi BH, Panton LB. Effects of resistance training and walking on cardiovascular disease risk in African-American women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(3):525–533. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31822e5a12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hornbuckle LM, McKenzie MJ, Whitt-Glover MC. Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic risk in overweight and obese African-American women: a pilot study. Ethn Health. 2018;23(7):752–766. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2017.1294661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ingram D, Wilbur J, McDevitt J, Buchholz S. Women’s walking program for African American women: expectations and recommendations from participants as experts. Women Health. 2011;51(6):566–582. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.606357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wharton W, Jeong L, Ni L, et al. A Pilot randomized clinical trial of adapted tango to improve cognition and psychosocial function in African American women with family history of Alzheimer’s disease (ACT trial) Cereb Circ - Cogn Behav. 2021;2:100018. doi: 10.1016/j.cccb.2021.100018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendham AE, Larsen S, George C, et al. Exercise training results in depot-specific adaptations to adipose tissue mitochondrial function. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):3785. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60286-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheppard VB, Makambi K, Taylor T, Wallington SF, Sween J, Adams-Campbell L. Physical activity reduces breast cancer risk in African American women. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(4):406–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans LK. Rural Black women’s thoughts about exercise. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(4):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fortuin-de Smidt MC, Mendham AE, Hauksson J, et al. Effect of exercise training on insulin sensitivity, hyperinsulinemia and ectopic fat in black South African women: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183(1):51–61. doi: 10.1530/eje-19-0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clamp LD, Mendham AE, Kroff J, Goedecke JH. Higher baseline fat oxidation promotes gynoid fat mobilization in response to a 12-week exercise intervention in sedentary, obese black South African women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metabol. 2020;45(3):327–335. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2019-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baruth M, Sharpe PA, Parra-Medina D, Wilcox S. Perceived barriers to exercise and healthy eating among women from disadvantaged neighborhoods: results from a focus groups assessment. Women Health. 2014;54(4):336–353. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.896443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathunjwa ML, Semple SJ, du Preez C. A 10-week aerobic exercise program reduces cardiometabolic disease risk in overweight/obese female African university students. Ethn Dis. 2013;23(2):143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mama SK, Diamond PM, McCurdy SA, Evans AE, McNeill LH, Lee RE. Individual, social and environmental correlates of physical activity in overweight and obese African American and Hispanic women: a structural equation model analysis. Prev Med reports. 2015;2:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huebschmann AG, Campbell LJ, Brown CS, Dunn AL. “My hair or my health:” Overcoming barriers to physical activity in African American women with a focus on hairstyle-related factors. Women Health. 2016;56(4):428–447. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2015.1101743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joseph RP, Coe K, Ainsworth BE, Hooker SP, Mathis L, Keller C. Hair as a barrier to physical activity among african American women: a qualitative exploration. Front public Heal. 2017;367:5. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blackman Carr LT, Nezami BT, Leone LA. Perceived benefits and barriers in the mediation of exercise differences in older black women with and without obesity. J racial Ethn Heal disparities. 2020;7(4):807–815. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adamus-Leach HJ, Mama SK, O’Connor DP, Lee RE. Income differences in perceived neighborhood environment characteristics among african american women. Environ Health Insights. 2012;6:33–40. doi: 10.4137/ehi.s10655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, Loftin-Bell K, Swett K, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA dermatology. 2013;149(3):310–314. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaston SA, James-Todd T, Riley NM, et al. Hair maintenance and chemical hair product usage as barriers to physical activity in childhood and adulthood among african American women. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(24):9254. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson BK, Wicks MN. Religiosity, self-efficacy for exercise, and African American women. J Relig Health. 2012;51(3):854–864. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott MS, Oman RF, John R. The Benefits and Barriers Related to Regular Participation in Physical Activity by African-American Women: Implications for Intervention Development. Open J Prev Med. 2015;5(4):169–176. doi: 10.4236/ojpm.2015.54020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gothe NP, Kendall BJ. Barriers, motivations, and preferences for physical activity among female african American older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2016 doi: 10.1177/2333721416677399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jackson H, Yates BC, Blanchard S, Zimmerman LM, Hudson D, Pozehl B. Behavior-specific influences for physical activity among african American women. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38(8):992–1011. doi: 10.1177/0193945916640724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.James DCS, Efunbumi O, Harville C, Sears C. Barriers and motivators to physical activity among african American women. Health Educ. 2014;46(2):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schoeny ME, Fogg L, Buchholz SW, Miller A, Wilbur J. Barriers to physical activity as moderators of intervention effects. Prev Med Reports. 2017;5:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zenk SN, Horoi I, Jones KK, et al. Environmental and personal correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior in African American women: an ecological momentary assessment study. Women Health. 2017;57(4):446–462. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2016.1170093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tenfelde SM, Hatchett L, Saban KL. “Maybe black girls do yoga”: a focus group study with predominantly low-income African-American women. Compl Ther Med. 2018;40:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kinsman J, Norris SA, Kahn K, et al. A model for promoting physical activity among rural South African adolescent girls. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:28790. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.28790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walker SD. University of Nevada; 2012. Perceptions of Barriers that Inhibit African American Women and Adolescent Girls from Participation in Physical Activity. Dissertation. Accessed November 27, 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials – the gold standard for effectiveness research: study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;125(13):1716. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hall KS, Hyde ET, Bassett DR, et al. Systematic review of the prospective association of daily step counts with risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and dysglycemia. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2020;17(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00978-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wattanapisit A, Wattanapisit ST, Thanamee S. Evidence behind 10,000 steps walking. J Heal Res. 2017;31(3):241–248. doi: 10.14456/jhr.2017.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alduhishy A., Baxendale R. 10,000 Step per day programme among Saudi Arabian overweight. Physiotherapy. 2011;97:eS45–eS46. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2011.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boukrina O, Kucukboyaci NE, Dobryakova E. Considerations of power and sample size in rehabilitation research. Int J Psychophysiol. 2020;154:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marcus BH, Williams DM, Dubbert PM, et al. Physical activity intervention studies: what we know and what we need to know. Circulation. 2006;114(24):2739–2752. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.106.179683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harden SM, McEwan D, Sylvester BD, et al. Understanding for whom, under what conditions, and how group-based physical activity interventions are successful: a realist review Health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Publ Health. 2015;15(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/S12889-015-2270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alvarado M, Murphy MM, Guell C. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity amongst overweight and obese women in an Afro-Caribbean population: a qualitative study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2015;97:12. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]