Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 and its variants have been investigated using a variety of mathematical models. In contrast to multi-strain models, SARS-CoV-2 models exhibit a memory effect that is often overlooked and more realistic. Atangana-Baleanu’s fractional-order operator is discussed in this manuscript for the analysis of the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2. We investigated the transmission mechanism of the SARS-CoV-2 virus using the non-local Atangana-Baleanu fractional-order approach taking into account the different phases of infection and transmission routes. Using conventional ordinary derivative operators, our first step will be to develop a model for the proposed study. As part of the extension, we will incorporate fractional order derivatives into the model where the used operator is the fractional order operator of order . Additionally, some basic aspects of the proposed model are examined in addition to calculating the reproduction number and determining the possible equilibrium. Stability analysis of the model is conducted to determine the necessary equilibrium conditions as they are also required in developing a numerical setup. Utilizing the theory of nonlinear functional analysis, for the model, Ulam-Hyers’ stability is established. We present a numerical scheme based on Newton’s polynomial in order to set up an iterative algorithm for the proposed ABC system. The application of this scheme to a variety of values of indicates that there is a relationship between infection dynamics and the derivative’s order. We present further simulations which demonstrate the importance and cruciality of different parameters, as well as their effect on the dynamics and administer the disease. Furthermore, this study will provide a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying contagious diseases, thus supporting the development of policies to control them.

Keywords: Asymptotic behavior, SARS-CoV-2, Dual variants, Newton’s polynomial, Fractional model

1. Introduction

In Wuhan, China, the first case of SARS-CoV-2, which is the cause of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), was reported in 2019. As a single-stranded RNA virus, SARS-CoV-2 has genetic material that mutates rapidly [1]. It has been shown in several patterns that only a few mutations may cause more severe diseases with increased transmissibility and infectiousness [2]. Over the last two years, different variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been reported. Among these variants, B.1.1.7 (alpha) was detected in the United Kingdom, in December 2020, B.1.617.2 (delta), the ”highly transmissible” variant, in India [1], and recently in South Africa, the B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant is seen. Found in almost every country around the globe, the World Health Organization has classified these variants as ”VOC, i.e, variants of concern”. There has been a rise in COVID-19 cases where variants such as Delta and Omicron have been identified in large numbers, and a further spread of Omicron is expected in many countries. It has been reported, however, that Omicron-caused disease may not be as severe as the other VOC [2]. Although several control measures have been deployed for stopping COVID-19, vaccination has proven high efficacy against severe illnesses caused by any of mentioned variants. As examples of modern vaccines include the BNT162b2 Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, J & J vaccine, and Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine (Thomson, Dagan), among others. There is strong evidence that these vaccines are effective against the variants of SARS-CoV-2, including the Omicron and Delta variants [3]. The effectiveness of available vaccines against these VOCs has been investigated in epidemiological studies, cited in [4], [5].

Two or more strains of the same virus can infect an individual simultaneously, which is known as a dual infection. An increase in viral populations can result from the virus disrupting the host’s immune response. According to reports [6], [8], it is possible to contract dual variants of COVID-19 simultaneously. Two cases of COVID-19 infection simultaneously were discovered by Brazilian researchers [7]. The study involved two young women with flu-like symptoms usually associated with mild-to-moderate illness. There was no need for hospitalization for either patient as they are not severely ill. Both variants of the virus identified so far have been circulating in Brazil since the outbreak was first reported. In Rio de Janeiro, also the old strain as well as the new strain P.2 were detected in a single person. Additionally, in Belgium, an elderly unvaccinated woman has been confirmed to be infected by the two variants, alpha and beta, of COVID-19 [7]. Tested positive and infected with both of these strains on the same day, her respiratory symptoms rapidly worsened and shortly resulted in her death thereafter. Cases of dual infections with Omicron and Delta have been reported in several immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients residing in areas that differ by geography [9], [10], [11]. In the last decade, numerous cases of acquiring more than one strain of HIV have been reported [12], [13], [14]. Several viruses have been reported to cause dual infection, including influenza [15], Epstein-Barr [16] viruses and many others. A case of double-strained COVID-19 has been reported in March 2020 by Liu et al. [17] while a patient was hospitalized in Iceland. It appears that the previous strain of the virus is very contentious and dangerous, however, the latter has been found to be a mutated form of the virus that originated in Wuhan. The study by Hashim et al. [18] examined 19 patients and found that all of them are diagnosed with the dual infection. Additionally, they are found to be genetically interconnected mutations. They speculated in their study that strains co-infected with the truncated spike protein might counteract its negative effects. Based on an analysis of the differences between the dual strains, researchers as in [6] noted that these strains are replaceable by one another in a short time period.

Generalizing the ordinary derivatives leads to their fractional counterpart. Fractional calculus essentially encompasses classical calculus. To understand real-world phenomena in more depth, mathematical models with non-integer order operators can be helpful. As a result, models with fractional order derivatives are able to capture inversion behavior and disintegration memory more precisely. Fractional derivative-based models are useful and provide insight in more depth about a disease [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. There have been several fractional operators with nonsingular and singular kernels proposed in the literature, i.e., Baleanu et al. [24] considered planar system masses in an equilateral triangle and numerical Study within fractional calculus. Jajarmi et al. in [25] used the fractional optimal control problems with a general derivative operator. Mohammadi et al. [26] studied hybrid functions numerical scheme for fractional optimal control problems. Srivastava et al. [27] studied the fractional-order biological population model with carrying capacity. The results are produced by the authors by using the Schauder fixed point theorem, semigroup operator theory, and the theory of fractional calculus. Ndolane Sene [28], [29] used fractional derivative with Mittag–Leffler for the SIR epidemic model. Jagdev et al. [30] discussed the existence results for the fractional fish farm model associated with the Mittag–Leffler type kernel. The study [31] was carried out to implement the concept of fractional operators and investigate the key findings of a co-infected model for cancer and hepatitis.

Recent contributions to fractional calculus were made by Atangana and Baleanu. They formulated non-integer order operators to handle the fractional integrals and derivatives using the Mittag–Leffler function [32]. According to the above authors, Mittag–Leffler’s functions are more appropriate than power ones for understanding natural phenomena. An important fact to remember is that specifically the Mittag–Leffler function was introduced to represent the process of analytical continuation of power law series outside the convergence disc. Research in fractional calculus has surged since the Atangana-Baleanu operators were introduced in 2016. This work is expanding rapidly in mathematics, engineering, and science. Atangana-Baleanu derivatives are non-local fractional derivatives with non-singular kernels with a wide range of applications.

In this study, we want to systematically evaluate the dynamical elements of the SARS-CoV-2 deterministic epidemic model, taking into account the Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo Operator in order to get a deeper understanding of the pandemic. This research is motivated by the aforementioned literature. The fractional order SARS-CoV-2 pandemic model is provided with a thorough theoretical analysis. Furthermore, for the model, the basic reproductive number is computed with the help of the next-generation matrix technique. The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 contains the fundamental definitions for fractional calculus. Section 3 presents the model formulation for the disease followed by the deterministic analysis in Section 4. In Section 6, the existence and uniqueness of the non-negative solution in the fraction sense, sufficient conditions for the extinction of both strains, asymptotic analysis, and the existence of the unique stationary distribution of the underlying model are presented. For validation of the analytical work, numerical schemes and simulations are presented in Section 8. At the end conclusion of the study and future work is presented in Section 9.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we will revisit the differential and integral operators, beginning with the Caputo fractional derivative [39]:

| (1) |

Caputo-Fabrizio fractional derivative [39]:

| (2) |

Where , is a function called normalization function. The fractional derivative by Atangana and Baleanu [39]:

| (3) |

With the power-law kernel, exponential decay, and Mittag–Leffler kernel, the fractal-fractional derivative are defined as [39]:

| (4) |

where [40]:

| (5) |

Similarly, with the power-law kernel, exponential decay, and Mittag–Leffler kernel, the fractal-fractional integrals are given by [39]:

| (6) |

Theorem 2.1

Schauder’s fixed point theorem[41]: “Let X be a Banach space and is compact and continuous, if the set

is bounded, then has a unique fixed point”.

3. Mathematical model

Mathematical modeling of infectious diseases is a crucial tool used to understand the spread and dynamics of diseases in populations. By using mathematical equations and simulations, researchers can make predictions about the potential impact of diseases and evaluate the effectiveness of different control and prevention strategies [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55]. This can be especially important in outbreaks, where quick decision-making is crucial to prevent the spread of the disease. There are many different types of models that can be used, ranging from simple models that focus on a single aspect of the disease, to complex models that take into account multiple factors such as demographics, behavior, and interventions. In order to make accurate predictions, it is important to have accurate data on the disease in question, as well as a good understanding of the underlying biology and epidemiology [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61]. However, even with the best data and models, there is always uncertainty in predictions about infectious diseases, as the dynamics of disease spread can be unpredictable and influenced by many factors.

In this section, we introduce the concept of fractional calculus and revisit the system model studied in [33]. The community’s entire population is divided into six compartments as susceptible (or vulnerable) denoted by , exposed to strain 1 SARS-CoV-2 and strain 2 SARS-CoV-2 respectively denoted by and , infected by strain 1 SARS-CoV-2 and strain 2 SARS-CoV-2 respectively denoted as and , and survived from either or both strains denoted by . As we go further, we will refer to strain 1 as the original while strain 2 as the other variants such as Omicron and delta which are more infectious than the former SARS-CoV-2 strain and hence are the variants of concern (VoCs). The readers are asked to refer to Table 1 for the description of the parameters of the proposed model. We propose the following system of equations as our model:

| (7) |

Table 1.

Model parameters and their values.

| Parameter | Description | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment rate | 1930 | [33] | |

| Natural death rate | [33] | ||

| Transmission rate by | [33] | ||

| Transmission rate by | [33] | ||

| Transmission rate by | [33] | ||

| Transmission rate by | [33] | ||

| Progression rate from to | 0.0784 | [33] | |

| Progression rate from to | 0.0564 | [33] | |

| Death rate due to strain 1 | 0.015 | [33] | |

| Death rate due to strain 2 | 0.0143 | [33] | |

| Recovery rate of infected with strain 1 | 0.13978 | [33] | |

| Recovery rate of infected with strain 2 | 0.1 | [33] |

3.1. Model in Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo sense

Recently, it has been argued that the theory of fractional calculus has a wide range of applications and that modeling identical issues using fractional systems yielded more accurate results than modeling them with the ordinary derivatives approach [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]. As a result, we will adapt model (7) to the new framework by using the generalized Mittag–Leffler kernel and fractional derivative:

| (8) |

Under the starting approximation

4. Model equilibrium and the basic reproduction number

There are three equilibria for the double strain COVID-19 model namely the disease-free (DFE), endemic for strains 1, and endemic for strain 2, respectively denoted by , and 2. The first among the row, i.e. (DFE) is given by:

| (9) |

In addition, for the double strain COVID-19 model above, (basic reproductive number) is given by

| (10) |

where

| (11) |

It’s important to note that in the formula above for and are the contributions from strain 1 and strain 2, respectively. Further, since depends on transmission rates and other model parameters and is necessary to induce an average infection in a susceptible population, it, therefore, serves as a crucial transmissibility parameter.

5. Sensitivity analysis

To ascertain the factors that affect the spread of the disease the most, sensitivity analysis is required. Table 1 lists the parameter values that were utilized for the sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity analysis seeks to identify the factors that significantly affect a model [35]. This may be determined by examining each parameter’s sensitivity index expressed as an index (ind and is given by

where m needs to be analyzed as a parameter. In this work, is used as follows:

| (12) |

Table 2 shows the results of the parameter sensitivity index computation. It is clear from Table 2 that the parameters have positive indices, demonstrating that grows with the parameters. Observe that sensitivity indices for the other parameters are negative, indicating that when these parameters are increased, and drop. For instance, the parameter has a sensitivity index of , which means that a change in the parameter results in a change in in the same direction. On the other hand, changing the value of the parameter will result in a change in the value of but in the opposite direction. Similar behavior for the rest of the parameters can be interpreted easily.

Table 2.

Sensitivity index of model parameters.

| Parameter | Sensitivity Index | Parameter | Sensitivity Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9999 | 1 | ||

| −1 | −1 | ||

| 0.0031 | 0.0041 | ||

| 0.9969 | 0.9959 | ||

| −0.0026 | −0.0034 | ||

| −0.0966 | −0.1245 | ||

| −0.9 | −0.871 |

6. Existence results

In this section, for the existence of the solution of model (8), we use Schauder’s fixed point Theorem 2.1. Suppose that to be a continuous and real-valued function that contains the supremum norm space property, is a Banach Space on and with norm , where . The following system is obtained by applying the fractional integral operator to both sides of Eq. (8)

| (13) |

Using the 3 definition as a guide, we can write

| (14) |

where

| (15) |

If , and have the same upper largest value or bound, then , and must satisfy the Lipschitzian condition. Further assume that and are two non-identical functions, therefore, we have the following

| (16) |

Taking into account

one reaches

| (17) |

Similarly, we can obtain the following

| (18) |

The Lipschitzian condition, which has been true for all mappings, is represented by the last equation above. Now Eq. (14) can take the form

| (19) |

together with and . When repeated terms in discernment are taken into account, we obtain

| (20) |

It is critical to note that

Furthermore, considering (17), (18) and letting

we reach

| (21) |

Theorem 6.1

Note that if the following conditions hold

(22) (8) possesses a unique solution for .

Proof: We saw that the mappings , and have upper bounds. Additionally, if we look at Eqs. (17), (18), the abbreviations , and hold for Lipchitzian conditions. Thus, with the help of repeating hypothesis, Eq. (21) yields the following

| (23) |

Therefore, it implies for , all mapping exists and fulfill

Moreover, using triangular inequality for any k, Eq. (19) yields the following

| (24) |

with by supposition. It may be observed that and , in the Banach space , forms a Cauchy sequences, which implies the uniform convergence of all these quantities. Eq. (20) with limiting theorem as implies the uniqueness of root of Eq. (8). Thus it shows that with the condition given in (22), Eq. (8) has unique existence.

7. Hyers-Ulam Stability

Definition 7.1

. The AB arbitrary order integration problem as in Eqs. (14) is called H-U stable [34] if there exist fixed fulfilling: For all, for

(25) one can find satisfying

(26) Such that

Theorem 7.1

Under the condition J, the considered model of arbitrary order (8) is H-U stable.

Proof: According to theorem (6.1), fulfilling equations of of model (14), is a unique root of the AB fractional problem given in (8). Thus we have the following:

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

| (30) |

| (31) |

| (32) |

Taking, , this implies

| (33) |

Similarly,

| (34) |

thus completing the derivation.

8. Iterative solution by Newton polynomial

Based on the Newton polynomial [36], a numerical scheme for the underlying model is presented in this section. Novel COVID-19 deterministic models were proposed and solved by Atangana and Seda as can be seen in [37], [38]. Numerical analysis and image processing both are based on Newton’s interpolation is a traditional polynomial interpolation method. The interpolation functions used in classical methods are generally specific to the known data. Newton’s polynomial interpolation was chosen to be the primary focus of this study because they are advantageous to other polynomial interpolation methods. Furthermore, interpolation like this provides a rapid rate of convergence, is easily implemented, is mathematically safe, and is effective in many aspects, including integration and differentiation. In addition to all of these, one can easily compute derivatives of polynomials of any order. In the interpolant region, the Newton-type polynomial interpolant function can be modified by selecting the appropriate parameter values. Curves or surfaces that are interpolated may also be modified to meet the real geometric design requirements. (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Sensitivity analysis of different parameters versus and .

Starting with the Mittag–Leffler kernel,

| (35) |

In a more simply way, one can write the following:

| (36) |

Together with the fractional integral with Mittag–Leffler kernel and incorporating the Newton polynomial, our model takes the form given below:

Where

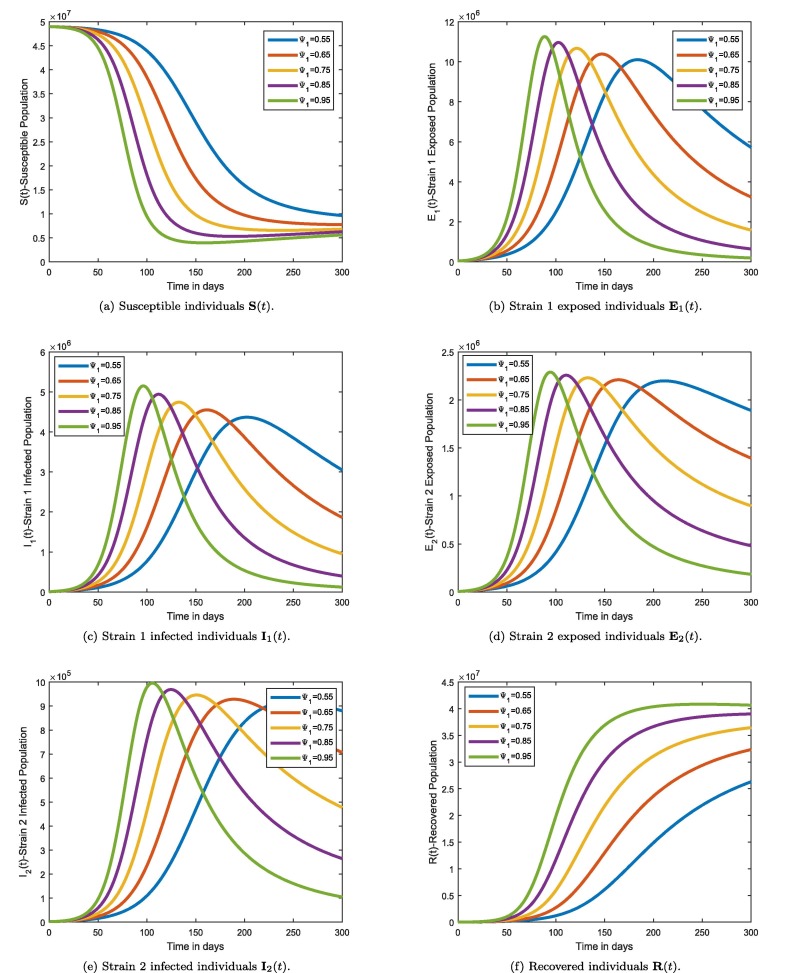

8.1. Graphical Results

In this section, the graphical results for the fractional order model (8) are presented. Based on the method given in [37], [38] and reading the information from Table 1, we numerically solve the fractional model. In Fig. 2 a susceptible individuals are characterized as their fractional-order derivatives creep between and 1. This can be seen from the figure that as time progresses, susceptible individuals decrease in number. This behaviour is natural as several weeks after the outbreak, the number of infected individuals is raised and thus leaving the class. The same behaviour can be found in a number of epidemiological models. Individuals exposed to strain 1 virus are depicted in Fig. 2b. As the fractional-order derivative approaches the classical counterpart, the population of increases steadily and becomes rapid near the order 1, the increase is rapid. This is expected as within a few weeks after the outbreak, more susceptible individuals encounter the disease and join the exposed class. Changes in the number of infected individuals by strain 1 are illustrated in 2c. As the fractional order moves toward 1, the count of individuals infected with strain 1 increases. This infection is driven by the fractional order, which is very sensitive. It becomes increasingly rapid as the fractional order approaches the value 1. The reason for this is that most individuals who are exposed move to the symptomatic and infectious stages of the infection within a few weeks of being exposed. The dynamics of the individuals exposed to double-strain viruses are presented in Fig. 2d. One can see a similar behaviour as above, i.e., the population exposed to the double strain increases as the fractional order of the derivative approaches integer order. According to this result, regardless of the strain of infection that is exposed to the population during the time of infection, The exposed population is affected in the same way by the fractional order as was found in 2b. The similarity between Fig. 2, Fig. 2e can be explained in the same manner. Fig. 2f depicts how the fractional order affects the counts of recovered persons from strain 1 and strain 2 infections. As the fractional-order derivative approaches the classical value, the number of recovered individuals grows. Since the infected individuals from both strains are recovering, this is the main reason for the steady growth. Infected people are typically urged to recover in order to aid in disease containment. This suggests raising the fractional order because, as the graph shows, a high fractional order causes the population of the class to grow considerably more quickly. (see Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 2.

Mittag–Leffler Generalized Function numerical simulation for the COVID-19 epidemic model (8) for days at .

Fig. 3.

Mittag–Leffler Generalized Function numerical simulation for the COVID-19 epidemic model (8) for days at .

The changes in class that take place when the infection rates vary are shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 c. With an increasing rate due to strain 1 infection, a steady raise in the counts in class can be observed. This rise is anticipated because more vulnerable people are exposed to strain 1 infectious persons and become infected. Increasing the strain 2 infection rate, on the other hand, has the opposite effect. The fact that the number of people in class has been steadily declining as the strain 2 infection rate has gone up is only evidence that raising the strain 2 infection rate while maintaining the strain 1 infection rate resulting a rise in the strain 2 infectious population, which gives time to strain 1 infectious population to decline. Fig. 4, Fig. 5c, on the other hand, depict the consequences of recovery rate variations in the class population. Fig. 5c shows that there is a constant rise in the patients of class when there is a fall from to in the recovery rate from the strain 1 infection. The population of class , however, explodes when the recovery rate from strain 1 infection drops from to . This may be explained by the fact that the frequency of infectious people and, thus, the likelihood of disease transmission will rise when there is a very low recovery rate from the disease. On the contrary, increasing the recovery rate from strain 2 infections leads to an increase in the population in class . The results in Fig. 5 can be interpreted in similarly.

Fig. 4.

The plots represents the impact of parameter on each state variable when .

Fig. 5.

The plots represents the impact of parameter on each state variable when .

9. Conclusion

In this paper, we provide a novel mathematical model for dual SARS-CoV-2 variants with vaccination effects using the ABC fractional derivative. According to the literature, the arbitrary operator analysis is the most effective technique for assessing the infection’s dynamic spread. The other parameters were assumed to be consistent in terms of dimension under the fractionalization order. It should be observed that the non-integer order type of the infection problem under consideration better captures the dynamics of the infection than does the variance of the natural order. Calculations are carried out for equilibrium of the underlying system, time dependency, and fundamental results. To demonstrate the existence of the solution, the fixed point theory approach is used. Numerical simulations were performed in order to validate theoretical conclusions on the extinction and survivability of SARS-CoV-2 variants in the population. For various arbitrary parameter counts, the results of approximate solutions are found. Specific vaccine techniques and treatments for contagious diseases are critical since vaccination is regarded as an effective weapon for eliminating SARS-CoV-2 in the human community. As a result, the general public and public health sectors must pay particular attention to this issue in order to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Government organizations should also provide vaccinations, and appropriate treatment in hospitals, schools, and colleges, as well as new, privatized healthcare facilities, to residents in every location. Because it will employ the asymptomatic carriers and immunize with ABC generalized operators, this discussion will be more relevant and valuable than the pre-related research. According to our investigation, the model’s conclusions and results utilizing generalized derivatives are significantly more exact and properly explain real-world situations.

The fractional model suggested in this study is based on the dynamics of distinct SARS-CoV-2 variants in the presence of vaccination. The cross-immunity between the variations was not considered in our model. This might be a model extension with more realistic assumptions on emergent variations of concern. Furthermore, the advent of new SARS-CoV-2 variations necessitates additional research into their co-infections with other diseases such as Hepatitis B virus, TB, influenza, Malaria, and others. Research in this area is still in its infancy. Furthermore, a lack of accurate information and data on developing VOC prevented us from fitting our model to actual SARS-CoV-2 data. It is our expectation that this will be accomplished with a more accurate and trustworthy understanding of many types of concerns.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by the Guangzhou Government Project under Grant No. 62216235, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 622260-1).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University.

References

- 1.Hu B., Guo H., Zhou P., Shi Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:141–154. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahimi Farid, Abadi Amin Talebi Bezmin. Is Omicron the last SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern? Arch. Med. Res. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized in the United States, 2021.

- 4.Tang P., Hasan M.R., Chemaitelly H., Yassine H.M., Benslimane F.M., Al Khatib H.A., AlMukdad S., Coyle P., Ayoub H.H., Al Kanaani Z., Al Kuwari E., Jeremijenko A., Kaleeckal A.H., Latif A.N., Shaik R.M., Abdul Rahim H.F., Nasrallah G.K., Al Kuwari M.G., Al Romaihi H.E., Butt A.A., Al-Thani M.H., Al Khal A., Bertollini R., Abu-Raddad L.J. BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in Qatar. Nat Med. 2021 2 doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01583-4. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34728831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasreen S., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against variants of concern. Canada. Preprint at medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.06.28.21259420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samoilov A.E., Kaptelova V.V., Bukharina A.Y., et al. Case report: change of dominant strain during dual SARS-CoV-2 infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:959. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06664-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.https://edition.cnn.com/2021/03/11/americas/brazil-variants-simultaneous-infection-intl/index.html.

- 8.https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/12/belgian-woman-infected-with-two-covid-variants-at-the-same-time.html.

- 9.P. Combes, M. Bisseux, A. Bal, et al. Evidence of co-infection during delta and omicron variants of concern co-circulation, weeks 49–2021 to 02–2022, France. medRxiv 2022; published online March 3. doi: 10.1101/2022.03.02.22271694 (preprint).

- 10.Zarin R., Haider N. Numerical solution of COVID-19 pandemic model via finite difference and meshless techniques. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2023;147:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.enganabound.2022.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vatteroni M.L., Capria A.-L., Spezia P.G., Frateschi S., Pistello M. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.1 and BA.2 subvariants in a nonvaccinated woman. The Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00119-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottlieb G.S., Nickle D.C., Jensen M.A., Wong K.G., Grobler J., Li F., et al. Dual HIV-1 infection associated with rapid disease progression. Lancet. 2004;363:619–622. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Kuyl A.C., Cornelissen M. Identifying HIV-1 dual infections. Retrovirology. 2007;4:67. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekouevi D.K., Eholie S.P. Encyclopedia of AIDS. Springer; New York: New York, NY: 2013. Update on HIV-1 and HIV-2 dual infection; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan A., Zarin R., Khan S., Saeed A., Gul T., Humphries U.W. Fractional dynamics and stability analysis of COVID-19 pandemic model under the harmonic mean type incidence rate. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2021:1–22. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2021.1972096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberg A., Bloch K.C., Li S., Tang Y., Palmer M., Tyler K.L. Dual infections of the central nervous system with Epstein-Barr virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;191:234–237. doi: 10.1086/426402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.S. Liu, J. Shen, S. Fang, K. Li, J. Liu, L. Yang, et al. Genetic spectrum and distinct evolution patterns of SARS-CoV-2, Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:2390. https:// doi. org/ 10. 3389/ fmicb. 2020. 593548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Hashim H., Mohammed M., Mousa M., Abdulameer H., Alhassnawi A., Hassan S., et al. Infection with different strains of SARS-COV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2020;72:575–585. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baleanu D., Ghassabzade F.A., Nieto J.J., Jajarmi A. On a new and generalized fractional model for a real cholera outbreak. Alexandria Eng. J. 2022;61(11):9175–9186. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan A., Zarin R., Hussain G., Ahmad N.A., Mohd M.H., Yusuf A. Stability analysis and optimal control of COVID-19 with Convex Incidence Rate in Khyber Pakhtunkhawa (Pakistan) Results Phys. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jajarmi A., Baleanu D., Sajjadi S.S., Nieto J.J. Analysis and some applications of a regularized ψ-Hilfer fractional derivative. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022;415:114476. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarin R., Khaliq H., Khan A., Khan D., Akgul A., Humphries U.W. Deterministic and fractional modeling of a computer virus propagation. Results Phys. 2022:105130. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarin R., Khan A., Banerjee R. Qualitative analysis and numerical simulation of fractal-fractional COVID-19 epidemic model with real data from Pakistan. Waves Random Complex Media. 2022;12:1–28. Nov. [Google Scholar]

- 24.D. Baleanu, B. Ghanbari, J.H. Asad, A. Jajarmi, H.M. Pirouz, Planar system-masses in an equilateral triangle: numerical study within fractional calculus, CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci., 124(3) (2020) 953–968, 2020.

- 25.Jajarmi A., Baleanu D. On the fractional optimal control problems with a general derivative operator. Asian J. Control. 2021;23(2):1062–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammadi F., Moradi L., Baleanu D., Jajarmi A. A hybrid functions numerical scheme for fractional optimal control problems: Application to nonanalytic dynamic systems. J. Vib. Control. 2018;24(21):5030–5043. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivastava H.M., Dubey V.P., Kumar R., Singh J., Kumar D., Baleanu D. An efficient computational approach for a fractional-order biological population model with carrying capacity, Chaos. Solitons & Fractals, Elsevier. 2020;vol. 138(C) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sene Ndolane. SIR epidemic model with Mittag-Leffler fractional derivative. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 2020;137:109833. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sene Ndolane. Analysis of the stochastic model for predicting the novel coronavirus disease. Adv. Diff. Eqs. 2020;2020(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s13662-020-03025-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jagdev S., Devendra K. Baleanu D.A new analysis of fractional fish farm model associated with Mittag-Leffler type kernel. Int. J. Biomath. 2020 doi: 10.1142/S1793524520500102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.E. Bonyah, R. Zarin, Fatmawati, Mathematical modeling of Cancer and Hepatitis co-dynamics with non-local and non-singular kernal, 2020, 2052–2541.https://doi.org/10.28919/cmbn/5029.

- 32.A. Abdon, D. Baleanu, New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel: theory and application to heat transfer model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.03408, 2016.

- 33.Yuliani E, Alfiniyah C, Juga ML, Chukwu CW. On the Modeling of COVID-19 Transmission Dynamics with Two Strains: Insight through Caputo Fractional Derivative. Fractal and Fractional. 2022 Jun 21;6(7):346.

- 34.Zarin R., Khan A., Inc M., Humphries U.W., Karite T. Dynamics of five grade leishmania epidemic model using fractional operator with Mittag-Leffler kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;147:110985. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chitnis N., Hyman J.M., Cushing J.M. Determining important parameters in the spread of malaria through the sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model. Bull. Math. Biol. 2008;70:1272–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11538-008-9299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atangana Abdon, Araz Seda Igret. Academic Press; 2021. New numerical scheme with Newton polynomial: theory, methods, and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atangana Abdon, Araz Seda Igret. Mathematical model of COVID-19 spread in Turkey and South Africa: theory, methods, and applications. Adv. Diff. Eqs. 2020;2020(1):1–89. doi: 10.1186/s13662-020-03095-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Araz Seda Igret. Analysis of a Covid-19 model: optimal control, stability and simulations. Alexandria Eng. J. 2021;60(1):647–658. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atangana Abdon. A novel Covid-19 model with fractional differential operators with singular and non-singular kernels: analysis and numerical scheme based on Newton polynomial. Alexandria Eng. J. 2021;60(4):3781–3806. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atangana Abdon, Goufo Emile Franc Doungmo. Some misinterpretations and lack of understanding in differential operators with no singular kernels. Open Phys. 2020;18(1):594–612. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Granas A., Dugundji J. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2003. Fixed point theory. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shagolshem Sumanta, Bira B., Zeidan D. Optimal subalgebras and conservation laws with exact solutions for biological population model. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 2023;166:112985. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zarin Rahat, Khan Amir, Kumar Pushpendra. Fractional-order dynamics of Chagas-HIV epidemic model with different fractional operators. AIMS Math. 2022;7(10):18897–18924. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar Sachin, Zeidan Dia. Numerical study of Zika model as a mosquito-borne virus with non-singular fractional derivative. Int. J. Biomath. 2022;15(05):2250018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeidan Dia, Chau Chi Kin, Tzon-Tzer Lu. On the characteristic Adomian decomposition method for the Riemann problem. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2021;44(10):8097–8112. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar Sachin, Zeidan Dia. An efficient Mittag-Leffler kernel approach for time-fractional advection-reaction-diffusion equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 2021;170:190–207. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zarin R. Numerical study of a nonlinear COVID-19 pandemic model by finite difference and meshless methods. Partial Diff. Eqs. Appl. Math. 2022;6:100460. doi: 10.1016/j.padiff.2022.100460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sultana Farheen, Singh Deeksha, Pandey Rajesh K., Zeidan Dia. Numerical schemes for a class of tempered fractional integro-differential equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 2020;157:110–134. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mishra A.M., Purohit S.D., Owolabi K.M., Sharma Y.D. A nonlinear epidemiological model considering asymptotic and quarantine classes for SARS CoV-2 virus. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 2020;138:109953. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owolabi Kolade M., Pindza Edson. A nonlinear epidemic model for tuberculosis with Caputo operator and fixed point theory. Healthcare Anal. 2022;2:100111. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu P., Din A., Zarin R. Numerical dynamics and fractional modeling of hepatitis B virus model with non-singular and non-local kernels. Results Phys. 2022;39:105757. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karaagac Berat, Owolabi Kolade M. Numerical analysis of polio model: A mathematical approach to epidemiological model using derivative with Mittag-Leffler Kernel. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zarin R., Khaliq H., Khan A., Ahmed I., Humphries U.W. A numerical study based on haar wavelet collocation methods of fractional-order antidotal computer virus model. Symmetry. 2023;15(3):621. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karaagac Berat, Owolabi Kolade Matthew, Nisar Kottakkaran Sooppy. Analysis and dynamics of illicit drug use described by fractional derivative with Mittag-Leffler kernel. CMC-Comput. Mater. Cont. 2020;65(3):1905–1924. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naik Parvaiz Ahmad, Owolabi Kolade M., Yavuz Mehmet, Jian Zu. Chaotic dynamics of a fractional order HIV-1 model involving AIDS-related cancer cells. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 2020;140:110272. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sulaiman Tukur Abdulkadir, Yavuz Mehmet, Bulut Hasan, Baskonus Haci Mehmet. Investigation of the fractional coupled viscous Burgers equation involving Mittag-Leffler kernel. Physica A. 2019;527:121126. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yavuz Mehmet, Sulaiman Tukur Abdulkadir, Yusuf Abdullahi, Abdeljawad Thabet. The Schrodinger-KdV equation of fractional order with Mittag-Leffler nonsingular kernel. Alexandria Eng. J. 2021;60(2):2715–2724. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu Yu, Khan Mohabat, Zarin Rahat, Khan Amir, Yusuf Abdullahi, Usa Wannasingha Humphries Mathematical analysis of a new nonlinear dengue epidemic model via deterministic and fractional approach. Alexandria Eng. J. 2023;67:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Musa Salihu S., Baba Isa A., Yusuf Abdullahi, Sulaiman Tukur A., Aliyu Aliyu I., Zhao Shi, He Daihai. Transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2: A modeling analysis with high-and-moderate risk populations. Results Phys. 2021;26:104290. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yi Zhao, Amir Khan, USA Wannasingha Humphries, Rahat Zarin, Majid Khan, Abdullahi Yusuf, Dynamics of visceral leishmania epidemic model with non-singular kernel. Fractals 30, no. 05 (2022): 2240135.

- 61.Kumar Pushpendra, Erturk Vedat Suat, Yusuf Abdullahi, Sulaiman Tukur Abdulkadir. Lassa hemorrhagic fever model using new generalized Caputo-type fractional derivative operator. Int. J. Model., Simul., Scient. Comput. 2021;12(06):2150055. [Google Scholar]