Abstract

Chronic mental health problems are common among military veterans who sustained blast-related traumatic brain injuries. The reasons for this association remain unexplained. Male rats exposed to repetitive low-level blast overpressure (BOP) exposures exhibit chronic cognitive and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-related traits that develop in a delayed fashion. We examined blast-induced alterations on the transcriptome in four brain areas (anterior cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum) across the time frame over which the PTSD-related behavioral phenotype develops. When analyzed at 6 weeks or 12 months after blast exposure, relatively few differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were found. However, longitudinal analysis of amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior cortex between 6 weeks and 12 months revealed blast-specific DEG patterns. Six DEGs (hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 [Hapln1], glutamate metabotropic receptor 2 [Grm2], purinergic receptor P2y12 [P2ry12], C-C chemokine receptor type 5 [Ccr5], phenazine biosynthesis-like protein domain containing 1 [Pbld1], and cadherin related 23 [Cdh23]) were found altered in all three brain regions in blast-exposed animals. Pathway enrichment analysis using all DEGs or those uniquely changed revealed different transcription patterns in blast versus sham. In particular, the amygdala in blast-exposed animals had a unique set of enriched pathways related to stress responses, oxidative phosphorylation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Upstream analysis implicated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α signaling in blast-related effects in amygdala and anterior cortex. Eukaryotic initiating factor eIF4E (EIF4e), an upstream regulator of P2ry12 and Ccr5, was predicted to be activated in the amygdala. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) validated longitudinal changes in two TNFα regulated genes (cathepsin B [Ctsb], Hapln1), P2ry12, and Grm2. These studies have implications for understanding how blast injury damages the brain and implicates inflammation as a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: blast, male rats, neuroinflammation, post-traumatic stress disorder, transcriptome, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is unfortunately common for active-duty service members. Personnel deployed to combat zones are especially prone to such injuries.1 The public's awareness of military-related TBI has increased over the past decade because of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.2 Although military-related TBIs occur through various mechanisms, certain types are relatively unique to military settings, the most prominent being blast-related TBI. Indeed, in Iraq and Afghanistan, exposures to improvised explosive devices (IEDs) constituted the major cause of TBI.2–4

A TBI history is frequent in military veterans seeking treatment at mental health clinics in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).5 TBI has been linked to numerous mental health problems including depression, anxiety, poor impulse control, sleep disorders, and suicide.6,7 A striking feature in the most recent veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan has been the overlap between a history of blast-related mild TBI (mTBI) and concurrent post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).2 Chronic post-concussion syndromes following TBI can persist for years, and in addition to static symptoms, new symptoms may appear or existing ones may worsen.8,9 TBI is also a risk factor for later development of neurodegenerative diseases.2,10–12

Male rats exposed to repetitive low-level blasts develop chronic cognitive and PTSD-related behavioral traits that develop in a delayed fashion, being absent in the first 8 weeks after blast exposure but then being consistently present ≥4 months after exposure.13–16 The traits remain present >1 year after blast exposure. Therefore, these blast-exposed animals mirror the prolonged and sometimes delayed post-concussive syndromes seen in many military veterans.

Transcriptional analysis using RNA sequencing quantitates RNA expression levels on a global scale in tissues or cells. It has become a cornerstone of modern efforts to understand the normal physiology and pathobiology of disease states. Here, we examined how the transcriptome of selected brain regions evolves following repetitive mild blast overpressure (BOP) exposure across the time frame over which the delayed behavioral phenotype develops. We describe progressive transcriptomic changes in the amygdala that implicate delayed inflammation, which may drive the emergence of PTSD-related behavioral traits that appear later. These findings have implications for understanding the pathophysiological basis of how blast injury damages the brain. They also suggest inflammation as a possible therapeutic target for blast-related neurobehavioral syndromes.

Methods

Animals

All studies involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR)/Naval Medical Research Center and the James J. Peters VA Medical Center. Studies were conducted in compliance with Public Health Service policy on the humane care and use of laboratory animals, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of animals in research.

Adult male Long Evans rats (250–350 g, 8 weeks of age) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories International (Wilmington, MA). Blast or sham exposures were delivered at 10 weeks of age. All animals were received from the vendor at the same time; blast and sham exposures were performed at the same time and animals were transported together in a single shipment from the Naval Medical Research Center to the Bronx VA. At the Bronx VA they were single housed in the same room under similar housing conditions, and underwent behavioral testing together, which was previously reported.17 All animals used in this study came from what was referred to as cohort 2 in the study by Perez Garcia and coworkers.17

Exposure to BOP

Anesthetized male rats were exposed to overpressure injury using the WRAIR shock tube, which simulates the effects of air-blast exposure under experimental conditions.18,19 The steel shock tube has a circular diameter of 30.48 cm and a length of 5.94 m. The tube is divided into a 77.4 cm compression chamber separated from the 5.18 m expansion chamber by polyethylene MylarTM sheets (Du Pont, Wilmington, DE, USA) that control the peak pressure generated. The peak pressure at the end of the expansion chamber was determined by piezoresistive gauges specifically designed for pressure-time (impulse) measurements (Model 102M152, PCB, Piezotronics, Depew, NY, USA).

Subjects were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in the shock tube lying prone, with the plane representing a line from the tail to the nose directly in line with the longitudinal axis of the shock tube, and the head placed more upstream. To prevent movement during the blast exposure, 1.5 cm diameter flattened rubber tourniquets were used to restrain the animals. Subjects were randomly assigned to sham or blast conditions and were placed in the shock tube. Additional details of the physical characteristics of the blast wave were previously described.18 Blast-exposed animals received 74.5 kPa exposures (equivalent to 10.8 psi, duration 4.8 ms, impulse 175.8 kPa/ms) delivered once a day for 3 consecutive days. Sham-exposed (control) animals received anesthesia and were placed in the blast tube but did not receive a blast exposure. Within 10 days after the last blast or sham exposure, animals were transported in a climate-controlled van from the WRAIR to the James J. Peters VA Medical Center (Bronx, NY, USA) where all other procedures were performed.

Animal housing

Animals were housed at a constant 70–72oF temperature with rooms on a 12:12 h light cycle with lights on at 7 a.m. All animals were individually housed in standard clear plastic cages equipped with Bed-O'Cobs laboratory animal bedding (The Andersons, Maumee, OH, USA) and EnviroDri nesting paper (Sheppard Specialty Papers, Milford, NJ, USA). Access to food and water was ad libitum.

Tissue collection

Animals were euthanized at 6 weeks and 12 months after the last blast exposure by CO2 inhalation. Prior to tissue collection, the animals were subjected to extensive behavioral testing; the results of this analysis have been published previously.17 After euthanasia, the brain was extracted and regionally dissected as previously described.20 Briefly after the removal of the cerebellum, the brain was placed ventral side up and a coronal cut was made anterior to the optic chiasm and anterior commissure. Cortical tissue surrounding this area (including somatosensory, motor, and frontal cortical regions) was designated as the anterior cortex. The amygdala was obtained by dissecting all tissue lateral to the hypothalamus between its rostral and caudal borders to the rhinal sulcus. The tissue was then placed dorsal side up, the hemisphere reflected out, and the hippocampus dissected based on its typical morphology. The posterior cortex (mainly posterior somatosensory, insular, auditory, and visual cortex) was included in the remainder of the hemispheres after dissection of the thalamus and caudate-putamen. All tissue was flash frozen and maintained at -80°C until processed. Regions from the right and left hemispheres were collected separately, and for this study all tissue analyzed came from the right hemisphere. The amygdala, hippocampus, anterior cortex, and cerebellum regions were analyzed.

RNA isolation, library construction, sequencing, and data analysis

Tissues were homogenized with the Qiazol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and the RNA was further purified with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA quality and integrity was assessed with the RNA Nano 6000 assay kit of the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All RNAs used for library generation had an integrity number (RIN) >8 and an A260/280 ratio ≥2. Library construction and sequencing were performed by Novogene Corporation (Durham, SC, USA). Libraries were constructed from 1 μg of total RNA using the NEBNextUltraRNA Library Prep kit from Illumina (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, sequenced on an Illumina Platform, and 125/150 bp reads were generated. Raw reads were cleaned by removing reads containing adapters, poly-N, and low-quality reads. Paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference rat genome using HISAT2.21 FeatureCounts v1.5.0-p3 was used to count the read number to each gene.22 Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 R package (1.14.1).23 The resulting p values were adjusted with the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control for false discovery rate (FDR) and genes with adjusted p value (padj) < 0.05 were considered to be differentially expressed. Ingenuity pathway (IPA, Qiagen) core analysis was used to search for gene enrichment, canonical pathways, genetic networks, and upstream regulatory genes. Longitudinal comparisons were made between (1) sham at 12 months versus sham at 6 weeks and (2) blast at 12 months versus blast at 6 weeks. There were no cross comparisons between blast and sham animals. In the longitudinal studies, adjusted p values were not further corrected for the independent sham and blast comparisons.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was reverse transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The resulting cDNA was diluted 1:20 and used for qPCR analysis. qPCR was performed using 2 μl of diluted cDNA with the TaqMan Gene Expression mastermix (ThermoFisher) in a 10 μl reaction. The following TaqMan assays (ThermoFisher) were used: Slc1a2 (Rn00691548_m1), P2ry12 (Rn02133262_s1), Ctsb (Rn00575030_m1), Sorbs1 (Rn01538740_m1), Hapln1 (Rn00569884_m1), Sqstm1 (Rn00709977_m1), Gapdh (Rn01775763_g1), GusB (Rn00566655_m1), Ppia (Rn00690933_m1) and Ywhaz (Rn00755072_m1). Relative gene expression was calculated with the 2-△△Ct method using the geometric mean of Gapdh, GusB, Ppia and Ywhaz (housekeeping genes not found to be altered in the RNA-sequencing analysis) to normalize expression. Samples from animals at 6 weeks post-blast exposure were used as the reference condition. Data were analyzed by two-tailed t tests using GraphPad Prism 9.0 with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

We performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) on regionally dissected tissue from four brain areas (the anterior cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum) collected at two time points after blast exposure (6 weeks and 12 months; n = 5 animals/group). These time points span the appearance of the behavioral phenotype.17 The anterior cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus were selected because of their relevance to the pathobiology of PTSD,24,25 and the cerebellum was selected because it is prominently affected by blast injury26 and modulates cognitive and affective functioning.27

Transcriptome changes at 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast injury

At 6 weeks and 12 months after blast exposure, relatively few DEGs passed adjusted p value cutoffs (padj < 0.05, Benjamini–Hochberg) and there was little consistency among DEGs between regions (Table 1). Relative to the sham condition, samples from the blast-exposed group showed that at 6 weeks after exposure in the amygdala there were eight DEGs, four upregulated (collagen alpha-1[V] [Col5a1], FA complementation group E [Fance], ribosomal protein L21 [Rpl21], and complement C3 [C3]) and four downregulated (glutamate decarboxylase 2 [Gad2], tachykinin precursor 1 [Tac1], abelson helper integration site 1 [Ahi1], and neurexophilin 1 [Nxph1]) (Table 1). In the anterior cortex TSC22 domain family member 4 (Tsc22d4) was upregulated and FUN14 domain containing 2 (Fundc2) and AC134224.3 were downregulated (Table 1). No DEGs were identified in hippocampus (Table 1). In the cerebellum, 22 genes in total were differentially regulated (15 up and 7 down, Table 1). In all regions, changes in gene expression levels were relatively small (0.2–0.3-fold).

Table 1.

Summary of Differentially Expressed Genes at 6 Weeks and 12 Months Post-Blast Exposure

| Time post-blast | Area | Total DEGs | DEGs up | DEGs down |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks | Amygdala | 8 | Col5a1, C3, Rpl21, Fance | Gad2, Tac1, Nxph, Ahi1 |

| 6 weeks | Anterior cortex | 3 | Tsc22d4 | Fundc2, AC134224.3 |

| 6 weeks | Hippocampus | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 weeks | Cerebellum | 22 | Wdr66, Ak5, LOC100365697, AABR07053509.2, Chd7, Camk1g, Gria2, Plekha5, Cemip, Pigk, Zfhx2, Kcnb1, Crebbp, Myt1, Per3 | Cam2k, Fundc2, Col9a2, Mras, Rpl12, Comtdi, Prdx2. |

| 12 months | Amygdala | 17 | Hapln4, ATP6v0c |

AABR07015057.1, AABR07063425.2 Mast2, Agpat3, AABR07015079, Chd3, Abcd3, Ttbk1, Mobp, Tmem151b, Cbx6, Csnk1g2 AABR07015081.1, AABR07015081.2, AC134224.1 |

| 12 months | Anterior cortex | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 months | Hippocampus | 1 | 0 | Map3k7 |

| 12 months | Cerebellum | 2 | Aurkb, Mmp14 | 0 |

DEGs, differentially expressed genes; Col5a1, collagen alpha-1(V); Rpl21, ribosomal protein L2; Fance, FA complementation group E; Tsc22d4, TSC22 domain family member 4; Wdr66, WD repeat-containing protein 66; Ak5, adenylate kinase 5; Chd7, chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 7; Camk1g, calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase IG; Gria2, glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 2; Plekha5, pleckstrin homology domain containing A5; Cemip, cell migration inducing hyaluronidase 1; Pigk, phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class K; Zfhx2, zinc finger homeobox 2; Kcnb1, potassium voltage gated channel subfamily b member 1; Crebbp, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein; Myt1, myelin transcription factor 1; Per3, period circadian regulator 3; Hapln4, hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 4; ATP6v0c, ATPase H+ transporting V0 subunit C; Aurkb, aurora kinase B; Mmp14, matrix metallopeptidase 14; Gad2, glutamate decarboxylase 2; Tac1, tachykinin precursor 1; Nxph, neurexophilin 1; Ahi1, abelson helper integration site 1; Fundc2, FUN14 domain containing 2; Cam2k, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II; Col9a2, collagen type IX alpha 2 chain; Mras, muscle RAS oncogene homolog; Rpl12, ribosomal protein L12; Comtd1, catechol-o-methyltransferase domain containing 1; Prdx2; peroxiredoxin 2; Mast2, microtubule associated serine/threonine kinase 2; Agpat3, 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate o-acyltransferase 3; Chd3, chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 3; Abcd3, ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 3; Ttbk1, tau tubulin kinase 1; Mobp, myelin associated oligodendrocyte basic protein; Tmem151b, transmembrane protein 151B; Cbx6, chromobox 6; Csnk1g2, casein kinase 1 gamma 2; Map3k7, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7.

At 12 months after blast exposure (Table 1), in the anterior cortex, no genes passed the adjusted p value cutoff and only one gene (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 [Map3k7]) was downregulated in the hippocampus (Table 1). In the amygdala, we found 17 DEGs, 2 upregulated (hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 4 [Hapln4] and ATPase H+ transporting V0 subunit C [Atp6v0C]) and 15 downregulated of which 9 were annotated genes (microtubule associated serine/threonine kinase 2 [Mast2], 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate o-acyltransferase 3 [Agpat3], chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 3 [Chd3], transmembrane protein 151b [Tmem151b], ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 3 [Abcd3], tau tubulin kinase 1 [Ttbk1], myelin associated oligodendrocyte basic protein [Mobp], chromobox 6 [Cbx6], casein kinase 1 gamma 2 [Csnk1g2]) (Table 1). In cerebellum, only two genes (aurora kinase B [Aurkb] and matrix metallopeptidase 14 [Mmp14]) were upregulated (Table 1). As found at 6 weeks post-blast, changes in gene expression levels were generally modest (0.2–0.3- fold).

Transcriptome changes between 6 weeks and 12 months differ between blast and sham-exposed animals

Collectively, the analysis at individual time points did not uncover any revealing gene expression patterns after blast exposure at either 6 weeks or 12 months. However, as the behavioral phenotype evolves over time after blast exposure,17 we wondered whether the transcriptome evolution might provide a more revealing picture. Therefore, we performed a longitudinal analysis comparing transcriptome evolution in blast- and sham-exposed animals between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast in the amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior cortex, these being the areas most relevant to the PTSD-like phenotype observed in blast-exposed male rats. Longitudinal comparisons were made between (1) sham at 12 months versus sham at 6 weeks and (2) blast-exposed at 12 months versus blast-exposed at 6 weeks. These comparisons yielded much more robust results.

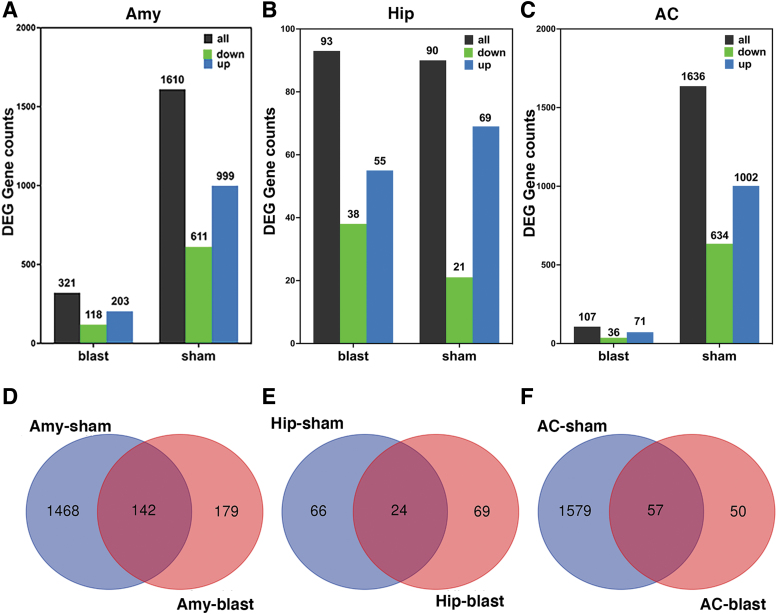

In all three regions, DEGs that changed between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast were very different in blast-exposed than in sham animals. Using 6 weeks post-blast (sham or blast) as the baseline, an adjusted p value of <0.05 and a log2Fc >0.2 as cutoffs, in the amygdala between 6 weeks and 12 months, there were 1610 DEGs in sham samples and 321 DEGs in blast samples (Fig. 1A), of which 142 were changed in both sham- and blast-exposed conditions (Fig. 1D). In the hippocampus, 90 DEGs were found in sham (21 down and 69 up) and 93 DEGs were found in blast-exposed (38 down and 55 up) animals (Fig. 1B) of which only 24 were commonly changed in the two conditions (Fig. 1E). In the anterior cortex, 1636 DEGs were found in sham (634 down and 1002 up) and 107 DEGs were found in blast-exposed (36 down and 71 up) animals (Fig. 1C), with 57 genes shared between sham and blast-exposed animals (Fig. 1F).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of differentially expressed genes in sham and blast-exposed amygdala (A), hippocampus (B), and anterior cortex (C) at 6 weeks and 12 months after blast exposure using 6 weeks as the baseline. The Venn diagrams (D, E) show unique and overlapping changes in sham and blast samples between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast. Amy, amygdala; Hip, hippocampus; AC, anterior cortex.

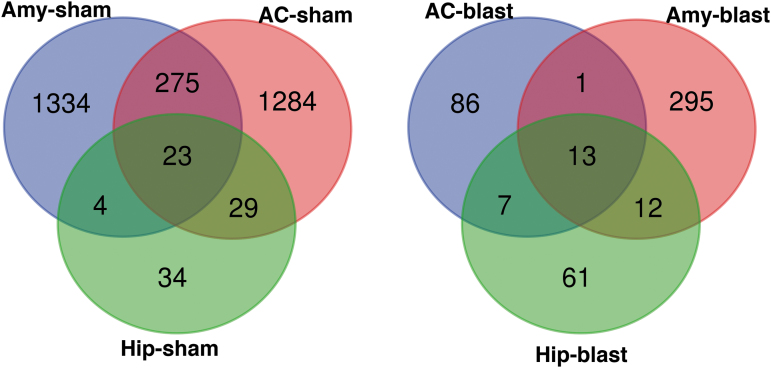

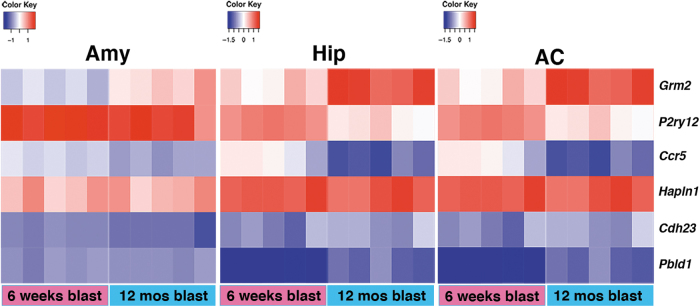

Therefore, there was a modest overlap between DEGs in blast-exposed and sham samples, with most DEGs being unique to a specific condition. Comparison of DEGs in sham samples (Fig. 2) showed that 23 were changed in all three brain areas of which 15 were annotated genes: niban apoptosis regulator 2 (Niban2), complement C3 (C3), mitochondrially encoded ATP synthase membrane subunit 8 (Mt-atp8), NO80 complex subunit E (Ino80e), Tfrc, sulfotransferase family 1A member 1 (Sult1a1), JunD, PNN interacting serine and arginine rich protein (Pnisr), riboflavin kinase (Rfk), alkaline ceramidase 2 (Acer2), UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase 1 like 1 (Uap1l1), Ahnak, small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 116 cluster (Snord116), 5_8S_rRNA and LOC100360413 (elongation factor-1-alpha-1 like) (Table 2). In blast-exposed samples (Fig. 2) we found 13 DEGs changed in the three areas, of which 6 were fully annotated genes, specifically hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (Hapln1), glutamate metabotropic receptor 2 (Grm2), purinergic receptor P2y12 (P2ry12), C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (Ccr5), and Pbdl1 (Table 3 and Fig. 3). In sham samples, hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein (Hapln1) expression was also downregulated in the anterior cortex and hippocampus, but not in the amygdala, whereas cadherin related 23 (Cdh23) was upregulated in the anterior cortex and amygdala, but not in the hippocampus.

FIG. 2.

Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes between 6 weeks and 12 months after blast in all areas broken down by sham and blast. Amy, amygdala; Hip, hippocampus; AC, anterior cortex.

Table 2.

Differentially Expressed Genes Commonly Changed in the Amygdala, Hippocampus, and Anterior Cortex in Sham-Exposed Animals between 6 Weeks and 12 Months after Blast

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Amy log2FC | Hip log2FC | AC log2FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niban2 | Niban apoptosis regulator 2 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| Tfrc | Transferrin receptor | -0.38 | -0.49 | -0.48 |

| Mt-atp8 | ATP synthase 8 mitochondria | 1.24 | 0.93 | 0.82 |

| Ino80e | INO complex subunit e | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| Sult1a1 | Sulfotransferase family 1A member 1 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.55 |

| C3 | Complement C3 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.39 |

| Jund | Jund proto-oncogene | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| Pnsir | PNN interacting serine and arginine rich protein | -0.35 | -0.25 | -0.43 |

| Rfk | Riboflavin kinase | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.55 |

| Acer2 | Alkaline ceramidase 2 | 1.09 | 0.99 | 0.89 |

| Uap1l1 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase 1 like 1 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.41 |

| Ahnak | Ahnak nucleoprotein | 0.91 | 0.99 | 1.04 |

| Snord116 | Small nuclear RNA C/D box 116 cluster | 1.54 | 2.08 | 1.25 |

|

AABR07015057.1 (ENSRNOG00000060518) |

rRNA promoter binding protein | 2.82 | 2.62 | 0.95 |

| LOC100911991( (AABR07042397.1) |

Elongation factor-1-alpha 1 like | 0.89 | 1.14 | 0.95 |

| 5_8S_rRNA | 2.21 | 2.41 | 0.67 | |

| AC127920.1 | Rn50_15_0083.1 | 0.79 | 1.55 | 1.16 |

| AABR07015078.1 | 2.18 | 2.56 | 1.52 | |

| AABR07063425.1 | 3.10 | 2.95 | 1.61 | |

| AABR07015081.1 | 3.26 | 2.80 | 1.95 | |

| AABR07063425.2 | 2.84 | 2.88 | 1.61 | |

| AABR0701A5042.1 | 2.99 | 2.67 | 1.16 | |

| AABR07015081.1 (ENSRNOG00000054945) | 2.07 | 2.8 | 1.89 |

Amy, amygdala; Hip, hippocampus; AC, anterior cortex; FC, fold change.

Table 3.

Differentially Expressed Genes Commonly Changed in the Amygdala, Hippocampus, and Anterior Cortex of Blast-Exposed Animals between 6 Weeks and 12 Months after Blast

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Amy log2FC | Hip log2FC | AC log2FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hapln1 | Hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein | -0.29 | -0.44 | -0.52 |

| Grm2 | Metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 | 0.88 |

0.78 | 1.06 |

| P2Ry12 | Purinergic receptor P2y12 | -0.64 | -0.66 | -0.94 |

| Ccr5 | C-C chemokine receptor 5 | -0.73 | -0.77 | -0.82 |

| Pbld1 | Phenazine biosynthesis-like domain containing protein 1 | 0.97 | 1.61 | 1.44 |

| Cdh23 | Cadherin related gene 23 | 1.26 | 1.21 | 0.99 |

| AABR07015042.1 | 2.51 | 2.86 | 1.42 | |

| AABR07015078.1 | 1.80 | 2.50 | 1.51 | |

| AABR07063425.2 | 2.41 | 3.04 | 1.66 | |

| AABR07015057.1 | 2.52 | 2.83 | 1.94 | |

| AABR07063425.1 | 3.10 | 2.91 | 1.56 | |

| AABR07015081.2 | 1.64 | 2.24 | 1.88 | |

| AABR07015081.1 | 2.61 | 2.83 | 1.89 |

Amy, amygdala; Hip, hippocampus; AC, anterior cortex; FC, fold change.

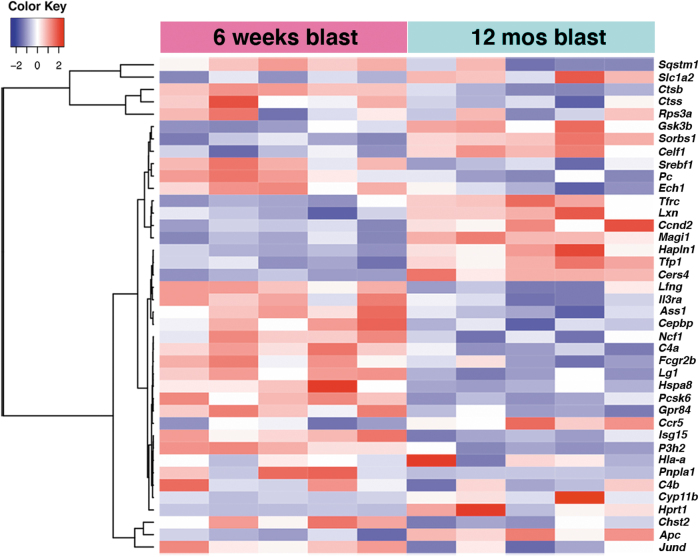

FIG. 3.

Heat map showing the six annotated genes commonly changed in Amy, Hip, and AC between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast. Amy, amygdala; Hip, hippocampus; AC, anterior cortex.

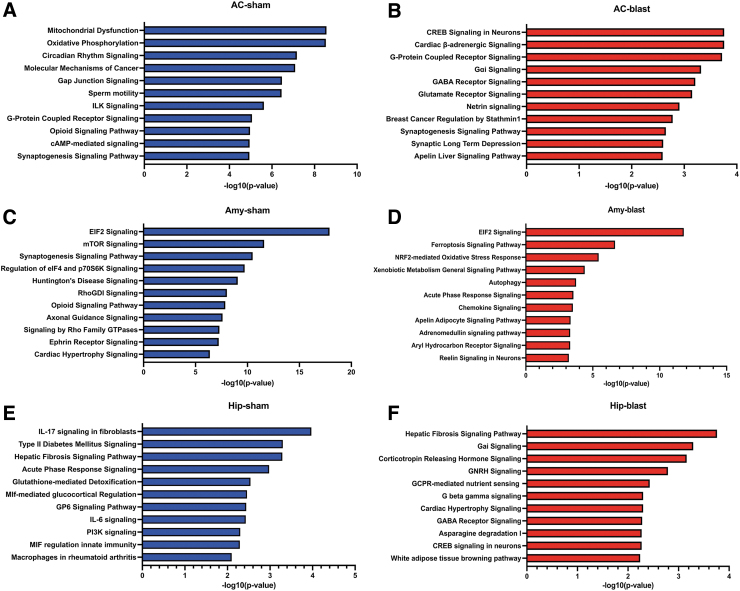

Pathway enrichment analysis reveals different patterns of transcriptome evolution in blast- versus sham-exposed animals

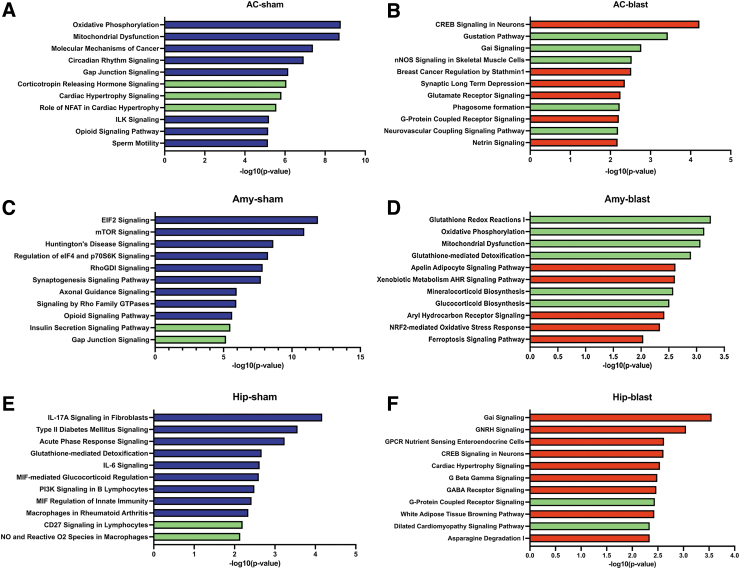

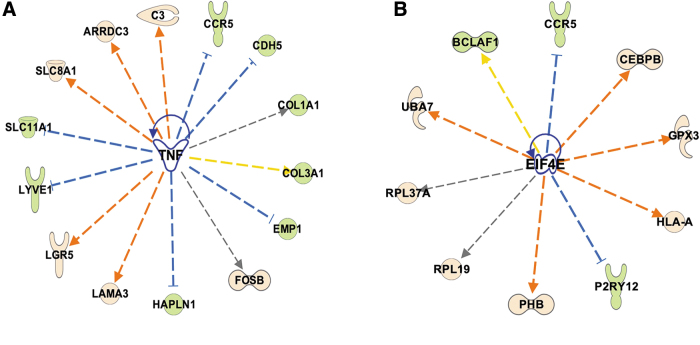

Using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) we determined the main pathways that were enriched in sham and blast samples between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast exposure using all the identified DEGs (Fig. 4). Reflecting the relatively modest overlap in shared DEGs, in each area the most enriched pathways were different in sham and blast samples except for eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2) signaling in the amygdala, which was enriched in both conditions. In the anterior cortex and hippocampus from blast-exposed animals, the most enriched pathways were involved in neuronal functions including cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) signaling, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, Gα1 (G protein-coupled intracellular signaling pathways), synaptogenesis, glutamate receptors, and G protein-coupled receptors (Fig. 4). In contrast, the amygdala had a unique set of enriched pathways related to stress responses (ferroptosis signaling, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 [Nrf2]-mediated oxidative stress response, acute phase response; Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Pathway enrichment using all the genes differentially expressed between 6 weeks and 12 months post-exposure in sham (A, C, E) and blast-exposed (B, D, F) anterior cortex (AC), amygdala (Amy), and hippocampus (Hip). Top 11 categories are listed. The x-axis indicates the -log 10 of overlap function.

As shown in Figure 2, in each brain region, most DEGs were uniquely changed by blast exposure or sham condition. To determine the pathways represented by these unique DEGs, we repeated the enrichment pathway analysis limited to these genes (Fig. 5). In sham-exposed animals, top enriched pathways were not greatly changed in any of the three regions analyzed (Fig. 5; pathways in green are those that were identified in analysis of the uniquely changed genes). In blast-exposed animals, neuronal CREB signaling remained the top enriched pathway in anterior cortex, whereas in the amygdala, EIF2 signaling was no longer the most enriched pathway. Moreover, in this group, genes related to stress responses, oxidative stress responses, oxidative phosphorylation, and mitochondrial dysfunction were mostly represented (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Pathway enrichment in sham (A, C, E) and blast-exposed (B, D, F) anterior cortex (AC), amygdala (Amy), and hippocampus (Hip) using only genes uniquely changed between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast exposure. Top 11 categories are listed. The x-axis indicates the -log 10 of overlap function. The green bars represent pathways that were not in the top enriched categories when all differentially expressed genes were included in the analysis (Fig. 4).

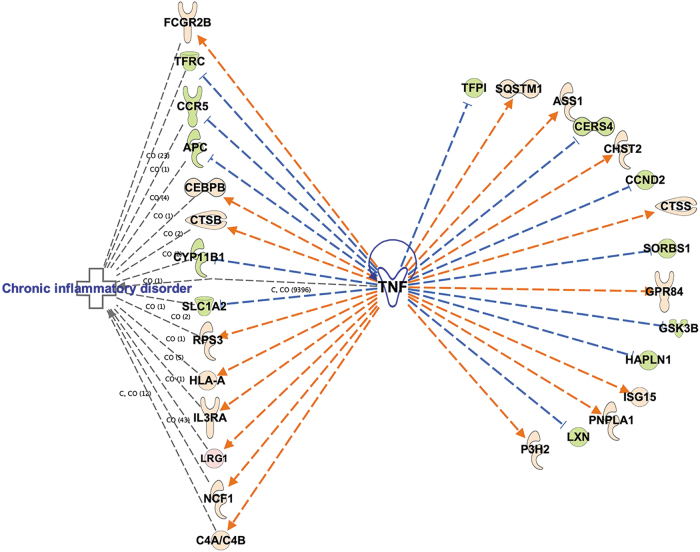

Upstream analysis implicates TNFα signaling in blast-related effects

To further understand the meaning of transcriptional changes found in the longitudinal analysis, we used IPA upstream regulator analysis to identify genes that could be master regulators of the longitudinally dysregulated genes in blast-exposed subjects. The most interesting findings were in the amygdala, where TNFα was predicted to be activated and to regulate 40 DEGs (z-score 2.628, p value overlap 2.35 x 10−4; Table 4). Figure 6 shows a heat map of the TNFα regulated DEGs expressed in the amygdala between 6 weeks and 12 months after blast exposure. Twenty-nine of these genes showed expression changes that were consistent with TNFα activation (Fig. 7). A group of these DEGs is associated with chronic inflammatory disorders (Fig. 7).

Table 4.

TNFα Regulated Genes Differentially Expressed in the Amygdala of Blast-Exposed Animals between 6 Weeks and 12 Months Post-Blast

| Gene | Prediction | Log2FC | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pnpla1 | Activated | 2.58 | Increased |

| Hsp8 | Inhibited | 1.02 | Increaseda |

| Hla-a | Activated | 0.87 | Increased |

| Lrg1 | Activated | 0.83 | Increased |

| P3h2 | Activated | 0.77 | Increased |

| Isg15 | Activated | 0.73 | Increased |

| Fcgr2b | Activated | 0.70 | Increased |

| C4a/C4b | Activated | 0.61 | Increased |

| Ass1 | Activated | 0.53 | Increased |

| Gpr84 | Activated | 0.52 | Increased |

| Ncf1 | Activated | 0.52 | Increased |

| Cebpb | Activated | 0.50 | Increased |

| Ilra | Activated | 0.45 | Increased |

| Srebf1 | Inhibited | 0.42 | Increaseda |

| Jund | Inhibited | 0.38 | Increaseda |

| Lfng | Inhibited | 0.37 | Increaseda |

| Chst2 | Activated | 0.35 | Increased |

| Ctss | Activated | 0.33 | Increased |

| Ech1 | Inhibited | 0.32 | Increaseda |

| Pcsk6 | Inhibited | 0.29 | Increaseda |

| Pc | Inhibited | 0.25 | Increaseda |

| Rps3 | Activated | 0.25 | Increased |

| Ctsb | Activated | 0.23 | Increased |

| Phb | Inhibited | 0.20 | Increaseda |

| Sqstm1 | Activated | 0.16 | Increased |

| Magi1 | Inhibited | -0.25 | Decreaseda |

| Sorbs1 | Activated | -0.28 | Decreased |

| Hapln1 | Activated | -0.29 | Decreased |

| Celf1 | Inhibited | -0.29 | Decreaseda |

| Apc | Activated | -0.29 | Decreased |

| Tfpi | Activated | -0.29 | Decreased |

| Ccnd2 | Activated | -0.37 | Decreased |

| Gsk3b | Activated | -0.39 | Decreased |

| Cers4 | Activated | -0.39 | Decreased |

| Slc1a2 | Activated | -0.39 | Decreased |

| Tfrc | Activated | -0.39 | Decreased |

| Ccr5 | Activated | -0.73 | Decreased |

| Lxn | Activated | -0.49 | Decreased |

| Cyp11b | Activated | -1.28 | Decreased |

| Hprt1 | Inhibited | -4.43 | Decreaseda |

Gene direction change not consistent with TNFα activation.

TNF, tumor necrosis factor; FC, fold change; Pnpla1, patatin like phospholipase domain containing 1; Hsp 8, heat shock 70 kDa protein 8; Hla-a, human leukocyte antigen; Lrg1, leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein 1; P3h2, prolyl 3-hydroxylase 2; Isg1, interferon-stimulated gene 15; Fcgr2b, Fc Gamma Receptor IIb; C4, complement component; Ass1, argininosuccinate synthase 1; Gpr 84, G protein-coupled receptor 84; Ncf1, neutrophil cytosolic factor 1; Cebpb, Ccaat enhancer binding protein beta; Ilra, interleukin 7 receptor; Srebf1, Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1; Jund, Jund proto-oncogene; Lfng O-fucosylpeptide 3-beta-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase; Chst2, carbohydrate sulfotransferase 2; Cs, cathepsin S; Ech1, enoyl-CoA hydratase 1; Pcsk6, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 6; Pc, pyruvate carboxylase; Rps 3, ribosomal protein S3; Ctsb, cathepsin B; Phb, prohibitin; Sqstm1, sequestosome 1; Magi1, membrane associated guanylate kinase; Sorbs1, sorbin and Sh3 domain containing 1; Hpln1, hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein; Celf1, Cugbp elav-like family member 1; Apc, adenomatous polyposis coli; Tfpi, tissue factor pathway inhibitor; Ccnd2, cyclin D2; Gsk3b, glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; Cers4, ceramide synthase 4; Slc1a2, solute carrier family 1 member 2; Tfrc, transferrin receptor; Ccr5, C-C chemokine receptor 5; Lxn, latexin; Cyp11b, cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily B member 1; Hprt1, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1.

FIG. 6.

Heat map of the genes that are differentially expressed in the amygdala between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast predicted by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) upstream analysis to be regulated by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α.

FIG. 7.

Differentially expressed genes in blast-exposed amygdala between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast with expression change direction consistent with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α activation. Green nodes: downregulated genes in the data set; pink nodes: upregulated genes in the data set. Genes associated with chronic inflammatory disorders are grouped on the left of the panel.

Upstream regulator analysis also predicted TNFα activation in the blast-exposed anterior cortex between 6 weeks and 12 months. Fourteen genes regulated by TNFα were found changed (p value overlap 8.42 10−4, activation z-score 3.077) of which 13 were up- or downregulated consistent with TNFα activation (Fig. 8A; p value = 0.0009).

FIG. 8.

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) upstream regulator analysis showing differentially expressed genes in blast-exposed anterior cortex that are predicted to be regulated by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α activation (A) and genes that could be regulated by eukaryotic initiating factor eIF4E (EIF4e) in blast-exposed amygdala (B). Green nodes: downregulated genes in the data set; pink nodes: upregulated genes in the data set.

Another upstream regulator predicted to be activated in the amygdala was eukaryotic initiating factor eIF4E (EIF4e; z-score 2.160, p value overlap 2 x 10−4). EIF4e regulates protein translation and could potentially regulate 10 DEGs affected by blast exposure (Fig. 8B). Among EIF4e-regulated genes are P2ry12 and Ccr5, which were among the DEGs commonly changed in all three brain areas following blast exposure (Table 3).

qPCR confirmation of select genes affected by blast exposure

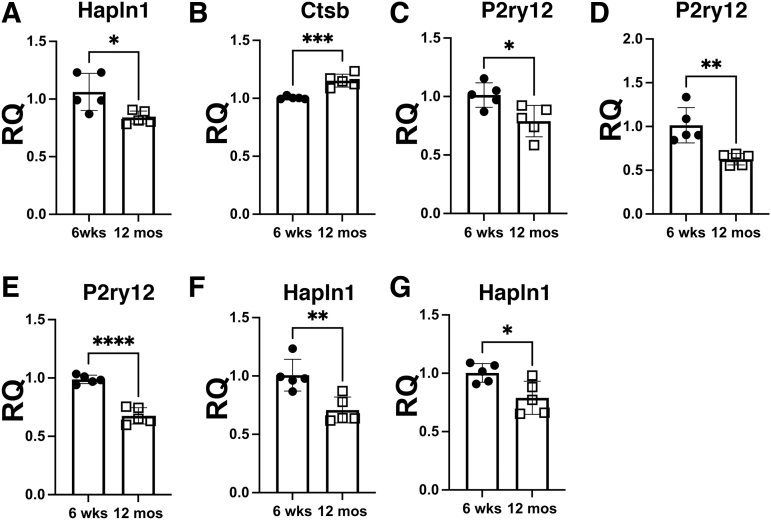

qPCR was used to validate longitudinal gene expression changes identified by RNA-seq analysis in blast-exposed samples between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast. In the amygdala we confirmed expression change of Ctsb (upregulation) and Hapln1 (downregulation), (Fig. 9A and B) which were among those predicted to be affected by TNFα activation (Table 4, Fig. 7). Hapln1 downregulation was also confirmed in the anterior cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 9F and G). In addition, downregulation of the microglial gene P2ry12 was confirmed in all the three brain areas analyzed (Fig. 9C–E). Grm2 upregulation was confirmed in all three regions.

FIG. 9.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis of targets identified by RNA seq analysis in blast samples between 6 weeks and 12 months post-blast. Relative quantification (RQ) was calculated with the 2-ΔΔCt method using the geometric means of Gapdh, GusB, Ppia and Ywhaz to normalize expression with 6-week post blast samples as reference. (A–C) Amy samples, hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (Hapln1) (A); cathepsin B (Ctsb) (B) and P2ry12 (C); (D, E) P2ry12 expression in AC (D) and Hip (E), (F, G) Hapln1 expression in AC (F) and Hip (G). Data were analyzed by two-tailed t tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Amy, amygdala; Hip, hippocampus; AC, anterior cortex.

Discussion

Blast exposures are the major cause of TBI in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3,4,10,28 In addition to in-theater exposures, there are also concerns over the potential adverse effects of subclinical blast exposures.29–31 This type of blast exposure, now being referred to as “military occupational blast exposure,” is common to many service members in combat and non-combat settings.29 Whether occupational repetitive low-level blast exposures could cause health problems later in life is unknown, but is a subject of concern.29,32

This study utilized an animal model proven to mimic blast-related human mTBI or subclinical blast exposure.13–17,20,33–38 It used exposures of 74.5 kPa (equivalent to 10.8 psi), which represent a level of blast that is transmitted to the brain,39 but does not produce major gross neuropathological effects.18 Blast exposures were delivered when the animals were 10 weeks of age, a time reflecting young adulthood in rats. Rats were placed in the shock tube lying prone with the plane representing a line from the tail to the nose directly in line with the longitudinal axis of the shock tube and the head placed more upstream. Therefore, there should be no laterality effects in terms of preferential damage to one side of the brain or the other. In addition, head motion was restricted during the blast exposure to minimize damage from rotational/acceleration injury.40,41 The lack of evidence for gross coup/contrecoup brain injuries supports the relatively mild nature of the injury.13,18 To mimic the multiple blast exposures commonly experienced by veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan,42 our design included three 74.5 kPa exposures delivered once a day for 3 consecutive days. All animals used in this study came from a single cohort of animals previously studied behaviorally and referred to as cohort 2 in the study by Perez Garcia and coworkers.17 Therefore, the only systematic differences between the groups in this study are the condition (blast vs. sham) and the time at which the animals were euthanized.

Male rats subjected to repetitive low-level blast exposure show cognitive and PTSD-related behavioral traits (chronic anxiety, altered fear responses, impaired recognition memory)16,17 that develop in a delayed manner and remain present for >1 year after the blast exposure.13–16,43 PTSD has been common in military veterans who sustained blast-related TBIs in Iraq or Afghanistan.2–4 The relationship between the two disorders and the importance of psychological versus physical injury remains a subject of discussion.2,44 For many military veterans, PTSD is only recognized after they leave active-duty service. Whether this reflects a delayed appearance of symptoms or an ascertainment bias caused by a greater likelihood that symptoms will be recognized after return to civilian life is unclear. However, what is clear is that in many veterans, symptoms once they appear are not static; old symptoms may worsen or new complaints develop.8,9,45 Indeed, one longitudinal study of Afghanistan veterans who sustained blast-related TBIs in theater found that between 1 and 5 years of follow-up, overall global functioning declined in >70%, a decline nearly completely driven by worsening PTSD and depression.9

These animals therefore model the enduring neurobehavioral syndromes that veterans often experience following blast exposure.42 However, although these traits are PTSD-related, this is not a model of PTSD, because the blast exposures occur under general anesthesia and no added psychological stressor is present. Rather, the model suggests that blast exposure alone without a psychological stressor can induce PTSD-related traits16 and sensitize the brain to react abnormally to subsequent psychological stressors.46,47 These observations have implications for how the mental health disorders that follow blast exposure are conceptualized, in particular the role of physical versus psychological trauma in military veterans who carry a diagnosis of PTSD and have a history of blast-related TBI.44

Here we examined how repetitive BOP affects the transcriptome across the time frame over which the delayed behavioral phenotype develops.17 We performed RNA sequencing on regionally dissected tissue from four brain areas collected at two time points after blast exposure. These time points (6 weeks and 12 months) span the appearance of the behavioral phenotype17 and correspond to a time point later in rat young adulthood (6 weeks post-blast, 16 weeks of age) and middle age (12 months post-blast, 14.5 months of age). The anterior cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus were selected because of their relevance to the pathobiology of PTSD,24,25 and the cerebellum was selected because it is prominently affected by blast injury26 and is known to modulate cognitive and affective behaviors.27

Analysis of gene expression patterns at individual 6 week or 12 month time points after blast exposure showed that relatively few DEGs passed the multiple testing correction, and that little consistency was found among DEGs between regions. However, more informative results were obtained by a longitudinal analysis comparing evolution of blast or sham gene expression profiles between 6 weeks and 12 months. Longitudinal comparisons were made between (1) sham at 12 months versus sham at 6 weeks and (2) blast at 12 months versus blast at 6 weeks, in the three regions (amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior cortex) that are relevant to the PTSD-like phenotype. In all three regions, the DEGs identified were different in blast-exposed compared to sham animals. Indeed, only a relatively modest overlap existed between DEGs in blast-exposed and sham animals, with most DEGs being unique to one condition or the other. In blast-exposed animals, six annotated genes were identified that were differentially expressed in all three brain regions (Table 3). Among the genes increased in all regions we found Grm2 (metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 [mGluR2]), a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor found mostly in pre-synaptic nerve terminals.48,49 Grm2's increased expression is notable in that we previously found that blast-related behavioral traits could be rescued by treatment with an mGluR2/3 antagonist.14

Three genes (P2ry12, Hapln1, and Ccr5) were downregulated in all three regions. The purinergic receptor P2ry12 is highly expressed in quiescent non-inflammatory M2 microglia, but its expression is downregulated in activated M1 inflammatory microglia and is associated with neuroinflammation.50 Constitutive or conditional deletion of P2ry12 in mice impairs recognition and social memory, increases anxiety, and alters fear learning.51,52 P2ry12 is of interest in that neuroinflammation was recently identified to be a late feature in this model.36

Hapln1 is a component of perineuronal nets, reticular structures made of extracellular matrix molecules that surround neurons.53 Hapln1 is essential for proper assembly of perineuronal nets,53 and a longitudinal downregulation of this gene could indicate that in blast-exposed brain, perineuronal nets become less stable with time. Ccr5, another DEG decreased in all regions, is expressed in astrocytes, microglia, and neurons.54 Although it is mostly known for its role in mediating human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV1) entry into cells, Ccr5 affects neuroplasticity as well as learning and memory, independent of its role in neuroinflammation.55 Of the other genes found increased in all three brain regions, Cdh23 encodes a member of the cadherin superfamily,56 whereas phenazine biosynthesis-like protein domain containing 1 (Pbld1) is predicted to be a negative regulator of SMAD and transforming growth factor β receptor signaling.57 However, neither gene has well-described roles in central nervous system (CNS) function.

Gene ontology analysis showed that in general, the most enriched pathways in each area were different in sham than in blast. Moreover, whereas in the anterior cortex and hippocampus from blast-exposed subjects the most enriched pathways were largely related to neuronal functions, in the amygdala, the pathways enriched were related to stress responses, oxidative phosphorylation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Therefore, evolution of gene expression over time following blast exposure is different in blast- than in sham-exposed animals, and in blast-exposed subjects, the amygdala shows unique transcriptional changes compared with the hippocampus and anterior cortex. This could be in part explained by the fact that in the amygdala, TNFα is predicted to be activated and to regulate several DEGs that are associated with inflammation.

One curious aspect of the results is that the longitudinal analysis yielded such robust results whereas comparisons at the individual time points did not. The lack of changes at individual time points might even be used to question whether changes found in the longitudinal analysis are in fact driving the appearance of the late behavioral phenotype.17 The reason for this finding is hard to explain, although a transcriptome analysis of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) and basolateral amygdala (BLA) at two time points using this same blast model studied here reported relatively similar findings in that few DEGs passed multiple testing corrections at individual time points, whereas analysis of the transcriptomics evolution over time implicated brain-derived neurotrophic factor-related signaling.58 In this study, TNFα was not identified as a potential regulator of blast-related effects.58 Future studies, perhaps at the single nuclei level, will be needed to explore these differences.

Another interesting aspect of the transcriptome evolution in this study was the increased number of DEGs identified in the control. DEG evolution in the control should reflect the normal transcriptome changes associated with aging. Dynamic changes in RNA expression occur with aging at various genomic levels, including coding and non-coding regions.59–67 Changes are complex and differ across species as well as in males and females.66 Although the patterns are hard to summarize and compare with our own studies, a common theme across many studies is the increased expression in the brain of neuroinflammation-related genes with aging.61–63,66 Our own studies could be seen, therefore, as suggesting that following blast exposure, there is, at least in males, an early aging of the brain transcriptome with increased expression of inflammatory related genes and decreased expression of other genes. Future studies at later time points will be needed to resolve this issue.

Although we cannot show a cause and effect relationship from the present studies, the identification of TNFα as a potential master regulator of a core set of genes affected by blast is an interesting and important finding. TNFα is well known for its role in systemic inflammatory responses.68 In the periphery, TNFα is secreted by activated monocytes and macrophages, as well as B cells, T cells, and fibroblasts. In brain TNFα is produced not only by microglia, but also by astrocytes and certain neurons.69 Within the brain, TNFα signaling has been implicated to be a link between neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity,70 and has also been suggested to affect circadian rhythms71 and auditory processing72 and to modulate neuropathic pain.73

Most relevant to the present study, TNFα has been implicated in PTSD-related hyperarousal states and regulating fear learning.74–77 For example, increased TNFα blocks retrieval and reconsolidation of contextual fear memories,74 whereas intracerebroventricular injection of TNFα impairs fear extinction.76 TNFα signaling in the hippocampus has also been implicated as mediating enhanced fear learning during drug withdrawal,75 and maternal TNFα production is suggested to program innate fear responses in offspring.78 The molecular basis for these effects is unclear, although microglial production of TNFα has been implicated in sustaining fear memories.77 Therefore, a variety of lines of evidence support a potential role for TNFα signaling in the neurobiological basis of blast effects on behavior. Interestingly, TNFα was also identified as a key regulator of several differentially expressed genes involved in inflammatory responses in the hippocampus of male rats injured by a fluid percussion TBI model.79 Studies in experienced breachers exposed to high numbers of career blast exposures also showed dysregulation of genes associated with chronic inflammation and immune response in peripheral blood,80 and elevated TNFα levels in neuronal-derived extracellular vesicles isolated from serum.81

One major limitation of the current studies is the lack of inclusion of female subjects. Sex differences in outcomes after TBI are well known.82 Studies also suggest that female veterans are more likely to report persisting neurobehavioral symptoms and to use more outpatient services than their male counterparts.83 Sex differences in response to blast exposure have been little studied, although two recent reports have suggested that blast responses in female rats may differ.84,85 With the increasing number of female veterans, these studies assume a high importance.

Although not limitations per se, two other factors that may affect the results are the use of single housing and the age at blast exposure. Single housing might affect expression of the behavioral phenotype and response to single housing might differ between blast- and sham- exposed animals. However, the comparable treatment of blast- and sham-exposed animals in this study should limit any effects to at most an interaction effect of condition and housing. Changes in phenotype might also occur if the injury was induced later in adulthood, a significant factor for many active-duty personnel who serve long military careers. Therefore, these results may not be directly translatable to veterans who sustained their TBIs later in their military careers.

Conclusion

We describe progressive transcriptomic changes in the amygdala, which implicate TNFα signaling and, by implication, delayed inflammation as a possible contributing factor to the chronic effects that follow repetitive low-level blast exposure in male rats. These studies have implications for understanding the pathophysiological basis of how blast injury damages the brain. Agents that modulate TNFα signaling are in widespread use in clinical practice.86 These studies identify TNFα signaling as a possible therapeutic target for blast-related injury. Future studies will be needed to explore the cause-and-effect relationship between inflammation and the behavioral phenotype, in particular the role of TNFα signaling. Studies in female rats are needed to examine the generalizability of findings.

Data Availability

Data are available in the GEO repository, accession GSE209992 and GSE205800.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States government. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the WRAIR/Naval Medical Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the James J. Peters Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of animals in research. The experiments reported herein were conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and per the principles set forth in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Laboratory Animals Resources, National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2011. Some of the authors are military service members or federal/contracted employees of the United States government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. § 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. § 101 defines a United States government work as a work prepared by a military service member or an employee of the United States government as part of that person's official duties.

Authors' Contributions

R.D.G., M.A.G.S., G.P.G., R.A., U.K., P.R.H., D.G.C., P.K., S.T.A., and G.A.E. designed the research. S.T.A. designed the blast exposures. R.D.G., G.P.G., G.M.P., R.A., U.K., J.K.S., and J.P. performed the research. R.D.G., P.K., and G.E. analyzed the data. R.D.G., M.A.G.S., P.R.H., D.G.C., S.T.A., and G.A.E. participated in drafting and revising of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding Information

This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service awards 1I01RX002660 (G.E.), 1I01RX003846 (G.E.), and 1I21RX003459 (M.A.G.S.); Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Medical Research Service awards 1I01BX004067 (G.E.) and 1I01BX002311 (D.C.); and Department of Defense work unit number 0000B999.0000.000.A1503 (S.T.A.) and National Institute of Aging P30 AG066514 (P.R.H.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Gubata ME, Packnett ER, Blandford CD, et al. Trends in the epidemiology of disability related to traumatic brain injury in the US Army and Marine Corps: 2005 to 2010. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2014;29(1):65–75; doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318295f590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elder GA, Ehrlich ME, Gandy S.. Relationship of traumatic brain injury to chronic mental health problems and dementia in military veterans. Neurosci Lett 2019; Epub ahead of print; doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med 2008;358(5):453–463; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, (eds.) Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brenner LA, Homaifar BY, Olson-Madden JH, et al. Prevalence and screening of traumatic brain injury among veterans seeking mental health services. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2013;28(1):21–30; doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31827df0b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jorge RE, Arciniegas DB. Mood disorders after TBI. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2014;37(1):13–29; doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dreer LE, Tang X, Nakase-Richardson R, et al. Suicide and traumatic brain injury: a review by clinical researchers from the National Institute for Disability and Independent Living Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) and Veterans Health Administration Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems. Curr Opin Psychol 2018;22:73–78; doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lange RT, Brickell TA, Ivins B, et al. Variable, not always persistent, postconcussion symptoms after mild TBI in U.S. military service members: a five-year cross-sectional outcome study. J Neurotrauma 2013;30(11):958–969; doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mac Donald CL, Barber J, Jordan M, et al. Early clinical predictors of 5-year outcome after concussive blast traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol 2017;74(7):821–829; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elder GA. Update on TBI and cognitive impairment in military veterans. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2015;15(10):68; doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0591-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jafari S, Etminan M, Aminzadeh F, et al. Head injury and risk of Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord 2013;28(9):1222–1229; doi: 10.1002/mds.25458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kalkonde YV, Jawaid A, Qureshi SU, et al. Medical and environmental risk factors associated with frontotemporal dementia: a case-control study in a veteran population. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8(3):204–210; doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elder GA, Dorr NP, De Gasperi R, et al. Blast exposure induces post-traumatic stress disorder-related traits in a rat model of mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2012;29(16):2564–2575; doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perez-Garcia G, De Gasperi R, Gama Sosa MA, et al. PTSD-related behavioral traits in a rat model of blast-induced mTBI are reversed by the mGluR2/3 receptor antagonist BCI-838. eNeuro 2018;5(1): ENEURO.0357-17.2018; doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0357-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perez-Garcia G, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, et al. Chronic post-traumatic stress disorder-related traits in a rat model of low-level blast exposure. Behav Brain Res 2018;340:117–125, doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.09.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perez-Garcia G, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, et al. Blast-induced “PTSD”: evidence from an animal model. Neuropharmacology 2019;145(Pt B):220–229; doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perez Garcia G, Perez GM, De Gasperi R, et al. Progressive cognitive and post-traumatic stress disorder-related behavioral traits in rats exposed to repetitive low-level blast. J Neurotrauma 2021;38(14):2030–2045; doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahlers ST, Vasserman-Stokes E, Shaughness MC, et al. Assessment of the effects of acute and repeated exposure to blast overpressure in rodents: toward a greater understanding of blast and the potential ramifications for injury in humans exposed to blast. Front Neurol 2012;3:32; doi: 10.3389/neur.2012.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yarnell AM, Shaughness MC, Barry ES, et al. Blast traumatic brain injury in the rat using a blast overpressure model. Curr Protoc Neurosci 2013;Chapter 9:Unit 9 41; doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0941s62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dickstein DL, De Gasperi R, Gama Sosa MA, et al. Brain and blood biomarkers of tauopathy and neuronal injury in humans and rats with neurobehavioral syndromes following blast exposure. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26(10):5940–5954; doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0674-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 2015;12(4):357–360; doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014;30(7):923–930; doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15(12):55; doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liberzon I, Abelson JL. Context processing and the neurobiology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuron 2016;92(1):14–30; doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liberzon I, Sripada CS. The functional neuroanatomy of PTSD: a critical review. Prog Brain Res 2008;167:151–169; doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meabon JS, Huber BR, Cross DJ, et al. Repetitive blast exposure in mice and combat veterans causes persistent cerebellar dysfunction. Sci Transl Med 2016;8(321):321ra6; doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa9585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schmahmann JD. The cerebellum and cognition. Neurosci Lett 2019;688:62-75; doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DePalma RG. Combat TBI: History, Epidemiology and Injury Modes. In: Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects. (Kobeissy F. ed.) CRC Press: Boca Raton FL; 2015; pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Engel C, Hoch E, Simmons M.. The Neurological Effects of Repeated Exposure to Military Occupational Blast: Implications for Prevention and Health: Proceedings, Findings, and Expert Recommendations from the Seventh Department of Defense State-of-the-Science Meeting. Rand Corporation: Arlington, VA; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tschiffely AE, Statz JK, Edwards KA, et al. Assessing a blast-related biomarker in an operational community: glial fibrillary acidic protein in experienced breachers. J Neurotrauma 2020;37(8):1091–1096; doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang Z, Wilson CM, Mendelev N, et al. Acute and chronic molecular signatures and associated symptoms of blast exposure in military breachers. J Neurotrauma 2020;37(10):1221–1232; doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pagulayan KF, Rau H, Madathil R, et al. Retrospective and prospective memory among OEF/OIF/OND veterans with a self-reported history of blast-related mTBI. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2018;24(4):324–334; doi: 10.1017/S1355617717001217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Janssen PL, et al. Selective vulnerability of the cerebral vasculature to blast injury in a rat model of mild traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014;2:67; doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Perez Garcia GS, et al. Low-level blast exposure disrupts gliovascular and neurovascular connections and induces a chronic vascular pathology in rat brain. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7(1):6; doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0647-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Perez Garcia GS, et al. Lack of chronic neuroinflammation in the absence of focal hemorrhage in a rat model of low-energy blast-induced TBI. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2017;5(1):80; doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0483-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Pryor D, et al. Low-level blast exposure induces chronic vascular remodeling, perivascular astrocytic degeneration and vascular-associated neuroinflammation. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2021;9(1):167; doi: 10.1186/s40478-021-01269-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perez Garcia G, De Gasperi R, Gama Sosa MA, et al. Laterality and region-specific tau phosphorylation correlate with PTSD-related behavioral traits in rats exposed to repetitive low-level blast. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2021;9(1):33; doi: 10.1186/s40478-021-01128-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Paulino AJ, et al. Blast overpressure induces shear-related injuries in the brain of rats exposed to a mild traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2013;1(1):51; doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chavko M, Koller WA, Prusaczyk WK, et al. Measurement of blast wave by a miniature fiber optic pressure transducer in the rat brain. J Neurosci Methods 2007;159(2):277–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cernak I, Stein DG, Elder GA, et al. Preclinical modelling of militarily relevant traumatic brain injuries: challenges and recommendations for future directions. Brain Inj 2017;31(9):1168–1176, doi: 10.1080/02699052.2016.1274779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Song H, Cui J, Simonyi A, et al. Linking blast physics to biological outcomes in mild traumatic brain injury: Narrative review and preliminary report of an open-field blast model. Behav Brain Res 2018;340:147–158; doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elder GA, Mitsis EM, Ahlers ST, et al. Blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010;33(4):757–781; doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perez Garcia G, De Gasperi R, Tschiffely AE, et al. Repetitive low-level blast exposure improves behavioral deficits and chronically lowers Abeta42 in an Alzheimer disease transgenic mouse model. J Neurotrauma 2021;38(22):3146–3173, doi: 10.1089/neu.2021.0184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Elder GA, Stone JR, Ahlers ST. Effects of low-level blast exposure on the nervous system: is there really a controversy? Front Neurol 2014;5:269; doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mac Donald CL, Barber J, Patterson J, et al. Association between 5-year clinical outcome in patients with nonmedically evacuated mild blast traumatic brain injury and clinical measures collected within 7 days postinjury in combat. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(1):e186676; doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Perez-Garcia G, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, et al. Exposure to a predator scent induces chronic behavioral changes in rats previously exposed to low-level blast: implications for the relationship of blast-related TBI to PTSD. Front Neurol 2016;7:176; doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schindler AG, Terry GE, Wolden-Hanson T, et al. Repetitive blast promotes chronic aversion to neutral cues encountered in the peri-blast environment. J Neurotrauma 2021;38(7):940–948; doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chaki S. mGlu2/3 receptor antagonists. Adv Pharmacol 2019;86:97–120; doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jin LE, Wang M, Galvin VC, et al. mGluR2 versus mGluR3 metabotropic glutamate receptors in primate dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: postsynaptic mGluR3 strengthen working memory networks. Cereb Cortex 2018;28(3):974–987; doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lin SS, Tang Y, Illes P, et al. The safeguarding microglia: central role for P2Y12 receptors. Front Pharmacol 2020;11:627760; doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.627760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Peng J, Liu Y, Umpierre AD, et al. Microglial P2Y12 receptor regulates ventral hippocampal CA1 neuronal excitability and innate fear in mice. Mol Brain 2019;12(1):71; doi: 10.1186/s13041-019-0492-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lowery RL, Mendes MS, Sanders BT, et al. Loss of P2Y12 has behavioral effects in the adult mouse. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22(4):1868; doi: 10.3390/ijms22041868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Oohashi T, Edamatsu M, Bekku Y, et al. The hyaluronan and proteoglycan link proteins: organizers of the brain extracellular matrix and key molecules for neuronal function and plasticity. Exp Neurol 2015;274(Pt B):134–144; doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cartier L, Hartley O, Dubois-Dauphin M, et al. Chemokine receptors in the central nervous system: role in brain inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2005;48(1):16–42; doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhou M, Greenhill S, Huang S, et al. CCR5 is a suppressor for cortical plasticity and hippocampal learning and memory. Elife 2016;5:e20985; doi: 10.7554/eLife.20985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Q, Peng C, Song J, et al. Germline mutations in CDH23, Encoding cadherin-related 23, are associated with both familial and sporadic pituitary adenomas. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100(5):817–823; doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li DM, Zhang J, Li WM, et al. MAWBP and MAWD inhibit proliferation and invasion in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19(18):2781–2792; doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i18.2781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Blaze J, Choi I, Wang Z, et al. Blast-related mild TBI alters anxiety-like behavior and transcriptional signatures in the rat amygdala. Front Behav Neurosci 2020;14:160; doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.00160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wood SH, Craig T, Li Y, et al. Whole transcriptome sequencing of the aging rat brain reveals dynamic RNA changes in the dark matter of the genome. Age (Dordr) 2013;35(3):763–776, doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9410-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shavlakadze T, Morris M, Fang J, et al. Age-related gene expression signature in rats demonstrate early, late, and linear transcriptional changes from multiple tissues. Cell Rep 2019;28(12):3263–3273 e3, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li M, Su S, Cai W, et al. Differentially expressed genes in the brain of aging mice with cognitive alteration and depression- and anxiety-like behaviors. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020;8:814; doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lupo G, Gaetani S, Cacci E, et al. Molecular signatures of the aging brain: finding the links between genes and phenotypes. Neurotherapeutics 2019;16(3):543–553;doi: 10.1007/s13311-019-00743-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ham S, Lee SV. Advances in transcriptome analysis of human brain aging. Exp Mol Med 2020;52(11):1787–1797; doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00522-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Naumova OY, Palejev D, Vlasova NV, et al. Age-related changes of gene expression in the neocortex: preliminary data on RNA-Seq of the transcriptome in three functionally distinct cortical areas. Dev Psychopathol 2012;24(4):1427–1442; doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Loerch PM, Lu T, Dakin KA, et al. Evolution of the aging brain transcriptome and synaptic regulation. PLoS One 2008;3(10):e3329; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Berchtold NC, Cribbs DH, Coleman PD, et al. Gene expression changes in the course of normal brain aging are sexually dimorphic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(40):15,605–15,610; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806883105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Isildak U, Somel M, Thornton JM, et al. Temporal changes in the gene expression heterogeneity during brain development and aging. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):4080; doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60998-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bradley JR. TNF-mediated inflammatory disease. J Pathol 2008;214(2):149–160; doi: 10.1002/path.2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Park KM, Bowers WJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediated signaling in neuronal homeostasis and dysfunction. Cell Signal 2010;22(7):977–983; doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Olmos G, Llado J. Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a link between neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity. Mediators Inflamm 2014;2014:861231; doi: 10.1155/2014/861231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ertosun MG, Kocak G, Ozes ON. The regulation of circadian clock by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2019;46:10–16; doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Deng D, Wang W, Bao S. Diffusible tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) promotes noise-induced parvalbumin-positive (PV+) neuron loss and auditory processing impairments. Front Neurosci 2020;14:573047; doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.573047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Leung L, Cahill CM. TNF-alpha and neuropathic pain—a review. J Neuroinflammation 2010;7:27; doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Takahashi S, Fukushima H, Yu Z, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha negatively regulates the retrieval and reconsolidation of hippocampus-dependent memory. Brain Behav Immun 2021;94:79–88; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Parekh SV, Paniccia JE, Adams LO, et al. Hippocampal TNF-alpha signaling mediates heroin withdrawal-enhanced fear learning and withdrawal-induced weight loss. Mol Neurobiol 2021;58(6):2963–2973; doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02322-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang Z, Song Z, Shen F, et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 prevents PTSD-like behaviors in mice through promoting synaptic proteins, reducing Kir4.1 and TNF-alpha in the hippocampus. Mol Neurobiol 2021;58(4):1550–1563, doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02213-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yu Z, Fukushima H, Ono C, et al. Microglial production of TNF-alpha is a key element of sustained fear memory. Brain Behavior Immunity 2017;59:313–321; doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zupan B, Liu B, Taki F, et al. Maternal brain TNF-alpha programs innate fear in the offspring. Curr Biol 2017;27(24):3859–3863 e3; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Boone DR, Weisz HA, Willey HE, et al. Traumatic brain injury induces long-lasting changes in immune and regenerative signaling. PLoS One 2019;14(4):e0214741; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Vorn R, Edwards KA, Hentig J, et al. A pilot study of whole-blood transcriptomic analysis to identify genes associated with repetitive low-level blast exposure in career breachers. Biomedicines 2022;10(3):690; doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10030690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Edwards KA, Leete JJ, Smith EG, et al. Elevations in tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 6 from neuronal-derived extracellular vesicles in repeated low-level blast exposed personnel. Front Neurol 2022;13:723923; doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.723923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gupte R, Brooks W, Vukas R, et al. Sex differences in traumatic brain injury: what we know and what we should know. J Neurotrauma 2019;36(22):3063–3091; doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cogan AM, McCaughey VK, Scholten J. Gender differences in outcomes after traumatic brain injury among service members and veterans. PM R 2020;12: 301–31; doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hubbard WB, Velmurugan GV, Brown EP, et al. Resilience of females to acute blood-brain barrier damage and anxiety behavior following mild blast traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2022;10(1):93; doi: 10.1186/s40478-022-01395-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. McNamara EH, Tucker LB, Liu J, et al. Limbic responses following shock wave exposure in male and female mice. Front Behav Neurosci 2022;16:863195; doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.863195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S. TNF-alpha as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases, ischemia-reperfusion injury and trauma. Curr Med Chem 2009;16(24):3152–3167; doi: 10.2174/092986709788803024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in the GEO repository, accession GSE209992 and GSE205800.