Summary

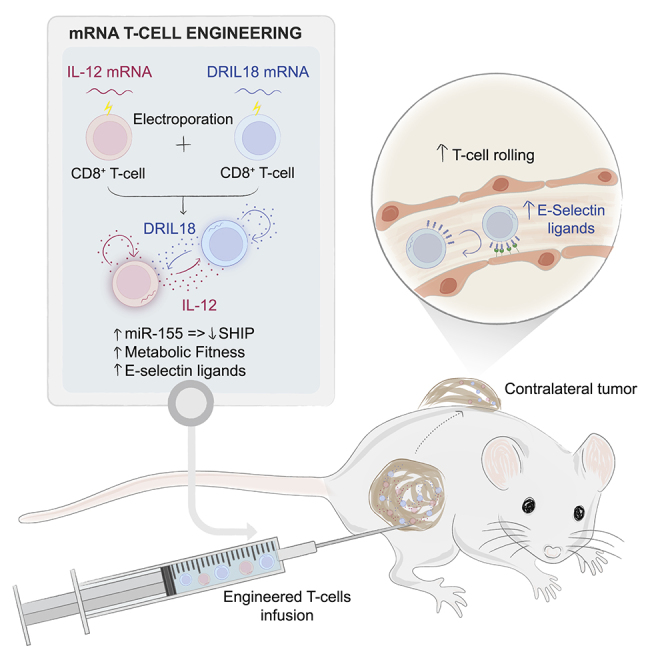

Interleukin-12 (IL-12) gene transfer enhances the therapeutic potency of adoptive T cell therapies. We previously reported that transient engineering of tumor-specific CD8 T cells with IL-12 mRNA enhanced their systemic therapeutic efficacy when delivered intratumorally. Here, we mix T cells engineered with mRNAs to express either single-chain IL-12 (scIL-12) or an IL-18 decoy-resistant variant (DRIL18) that is not functionally hampered by IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP). These mRNA-engineered T cell mixtures are repeatedly injected into mouse tumors. Pmel-1 T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic T cells electroporated with scIL-12 or DRIL18 mRNAs exert powerful therapeutic effects in local and distant melanoma lesions. These effects are associated with T cell metabolic fitness, enhanced miR-155 control on immunosuppressive target genes, enhanced expression of various cytokines, and changes in the glycosylation profile of surface proteins, enabling adhesiveness to E-selectin. Efficacy of this intratumoral immunotherapeutic strategy is recapitulated in cultures of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells on IL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA electroporation.

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

mRNA electroporation engineers T cells to transiently express IL-12 and DRIL18

-

•

Intratumoral delivery of IL-12/DRIL18-engineered T cells eradicates uninjected tumors

-

•

Enhanced efficacy depends on changes in glycosylation, miR-155, and metabolism in T cells

-

•

Engineering TILs or CAR T cells with IL-12/DRIL18 mRNAs enhances antitumor efficacy

Olivera et al. engineer tumor-specific T cells with mRNA to transiently express interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18. Repeated intratumoral injection of IL-12/DRIL18 mRNA-electroporated T cells leads to the rejection of directly treated and distant tumors. Glycosylation changes forming E-selectin ligands, miR-155 upregulation, and improved T cell metabolic fitness underlie efficacy.

Introduction

Adoptive T cell therapy is achieving clinical-practice-changing success for the treatment of B cell malignances in the form of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells.1,2 Adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL)-derived cultures is also showing efficacy against refractory cases of metastatic melanoma3,4 and HPV+ squamous carcinoma.5 Clinical progress is also being made with T cells engineered to express tumor-specific T cell receptors (TCRs).6,7,8 The field of adoptive T cell therapy offers promise to treat other malignant diseases, but results are as yet unsatisfactory against most solid tumors.

One of the main strategies to enhance the performance of adoptive T cell therapies involves the engineering of T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, or macrophages with gene-expression cassettes encoding next generation CARs, cytokines, and/or costimulatory molecules9,10,11,12 to generate the so-called armored CARs.13 Most popular retroviral gene-transfer strategies in lymphocytes have the inherent problem of leaving the inserted exogenous genes in the genome, resulting in long-term side effects potentially caused by the engineered cytokines.14 Even if transcriptionally controlled systems are employed, leakiness of expression might result in serious adverse events,14 and the co-engineering of suicide systems for safety reasons to eliminate transferred cells with drugs is problematic.15

mRNA engineering of T cells by electroporation is relatively simple, is clinically scalable, and can confer transient high expression of the intended exogenous proteins.16 However, expression extinction occurs in a few days, and hence either a reprogramming effect should last longer or repeated administrations would be needed for ultimately efficacious antitumor effects.17

Interleukin-12 (IL-12) is a potent immunotherapeutic cytokine in mouse models whose application as a systemic agent in the clinical setting is hampered by interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-dependent toxicity.18 As a result, many strategies to target or express IL-12 selectively in the tumor tissue are being pursued preclinically, as well as in clinical trials.19 Engineering T cells with IL-12 is highly efficacious in mouse models20 but results in serious adverse events in clinical settings.14 In contrast, IL-18 is a myeloid-derived cytokine that elicits IFN-γ expression on T and NK lymphocytes.21 Notably, it has been reported that retrovirally transfected Pmel-1 T cells to permanently express IL-18 can promote T cell effector function and augment antitumor efficacy.22

IL-12 and IL-18 are known to synergize in terms of eliciting massive IFN-γ production23 leading to severe toxic effects.24 For cancer immunotherapy, IL-18 has the caveat of being down-regulated in its function by a decoy receptor termed IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP),25 which is reportedly abundant in tumor tissues.26,27 Recently, a mutant sequence of mouse IL-18 termed DRIL18 (IL-18 decoy-resistant variant), which preserves its bioactivity but lacks binding to IL-18BP, has been reported to exert T cell-dependent antitumor activity on systemic delivery.26 Interestingly, a similar human mutant is undergoing a phase I clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04787042). In line with this, we have recently observed that mRNAs encoding single-chain IL-12 (scIL-12) and DRIL18, if expressed from the gene-transduced liver of mice, synergize to induce IFN-γ-dependent toxicity, but if delivered intratumorally, they synergize to induce antitumor effects.24 Regarding IL-18 and adoptive T cell therapy, the group of Dr. Carl June has recently reported that anti-CD19 CAR T cells armored in the retroviral construct with a wild type IL-18 proliferate better and exert more powerful antitumor effects on intravenous delivery to mice bearing CD19+ tumors.28

Previous work from our laboratory has shown that engineering of T cells with IL-12 and CD137L mRNAs enhanced their antitumor activity.29 In particular, we designed a strategy based on repeated intratumoral injection into a given lesion, achieving remarkable therapeutic activity against distant non-injected tumors.29 Notably, intratumoral delivery of immunotherapeutic agents is being extensively tested in preclinical models and in the clinic.30 Intratumoral/local immunotherapy at present chiefly involves recombinant viruses, pathogen-associated molecular patterns and nucleic acids encoding immunostimulatory factors. Intratumoral or intracavitary use of adoptive T cell transfer31 is also being actively used to treat primary brain tumors32,33 and pleural malignancies34 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03054298).

In this study, we sought to improve the therapeutic strategy of intratumoral delivery of T cells transiently engineered to express IL-12. We found that IL-18 and, more prominently, DRIL18 markedly increases the efficacy of adoptive T cell immunotherapeutic strategies in a safe fashion. The mechanisms underlying this synergistic effect involved modulation of adhesion molecules, secondary cytokines, metabolic adaptations, and miR-expression regulation. Importantly, our strategy based on mRNA transient engineering and repeated intratumoral administration could be efficaciously applied when using TIL cultures or CAR T cells.

Results

CD8 T cells engineered with IL-12- and DRIL18-encoding mRNAs synergize for intratumoral adoptive therapy

We previously reported the therapeutic benefit of repeated intratumoral injections of tumor-specific T cells transiently engineered with electroporated mRNA to express scIL-12.29 To improve such a strategy, we screened the co-electroporation of several mRNAs of pro-immune genes or siRNAs for immunosuppressive genes. IL-18 mRNA was identified as a strong candidate, and a mutant sequence of mouse IL-18 has been reported to be more bioactive as it loses its repressive binding to IL-18BP,26 which acts as a decoy receptor.

We constructed mRNAs encoding IL-18 and the IL-18 variant (DRIL18), which were electroporated into preactivated CD8+Pmel-1 cells. Forty-eight-hour culture supernatants contained significant amounts of IL-18 or DRIL18 proteins produced by electroporated Pmel-1 T cells, as was also observed with scIL-12 mRNA (Figures S1A–S1C). Expression peaked at 6–12 h following electroporation, as shown in Figures S1A and S1B. Next, we co-electroporated cells with scIL-12- and DRIL18-encoding mRNAs and found that DRIL18 lowered the percentage and intensity of intracellular IL-12 expression (Figure 1A). In these experiments, we could not stain for intracellular DRIL18 because of the lack of suitable reagents. However, we found that the IL-12 released into the supernatant was not reduced if, instead of co-electroporation (IL-12 + DRIL18), single mRNA-electroporated cells were mixed 1:1 after electroporation with either scIL-12 mRNA or DRIL18 mRNA (IL-12/DRIL18), as observed on measuring IL-12 concentrations in 24-h T cell culture supernatants in these conditions (Figure 1B).

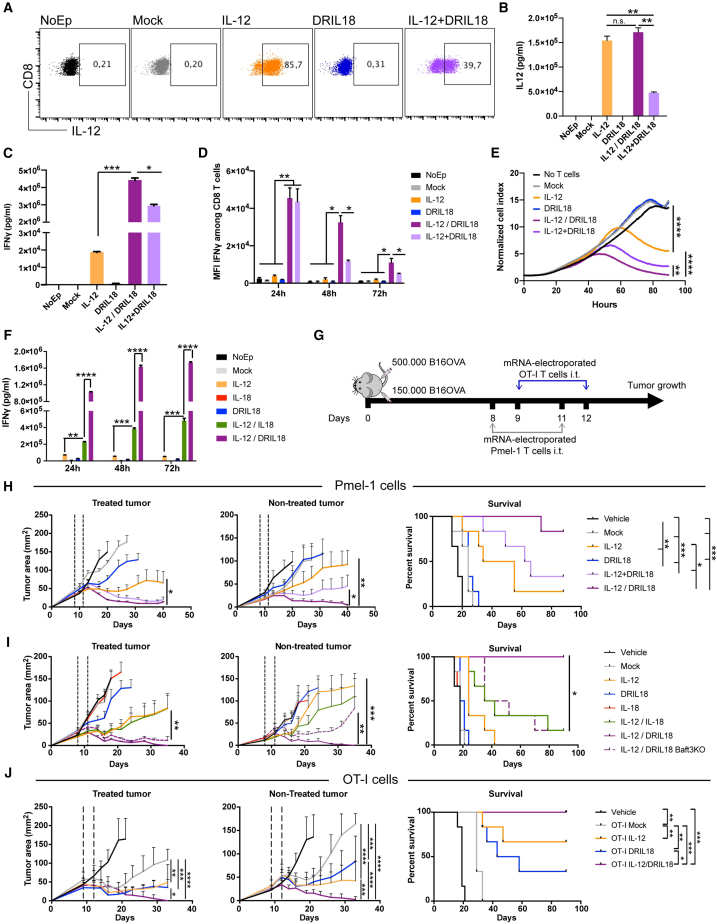

Figure 1.

Mixed Pmel-1 lymphocytes electroporated with scIL-12 or DRIL18 mRNA synergize for intratumoral adoptive T cell therapy

(A) Dot plots showing intensity and percentage of intracellular expression of IL-12 in preactivated Pmel-1 TCR transgenic cells with cognate peptide and electroporated 96 h later with the indicated mRNAs or a combination of scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNAs.

(B) Corresponding concentrations of IL-12 released into the supernatant over 24 h from Pmel-1 cells either co-electroporated (IL-12 + DRIL18) or separately electroporated and subsequently mixing the cells 1:1 (IL-12/DRIL18).

(C) Concentrations of IFN-γ in the same tissue culture supernatants 72 h later.

(D) Intracellular staining to determine IFN-γ abundance by flow cytometry at the indicated time points of culture following mRNA electroporations.

(E) Performance of the electroporated Pmel-1 cells with the indicated transduced mRNAs in xCELLigence cytotoxicity assays against B16-OVA cells at an initial 1:5 ratio.

(F) Concentrations of IFN-γ over time in the different conditions of electroporated mRNA comparing electroporation with IL-12, IL-18, or DRIL18 separate single-mRNA electroporation and a subsequent mix of the cells 1:1.

(G) Experimental design of experiments treating 8-day established subcutaneous bilateral B16-OVA tumors in which only one of the tumors received electroporated Pmel-1 cells.

(H) Tumor size follow-up of injected and non-injected tumors with the indicated mock or mRNA electroporated Pmel-1 cells or vehicle. Survival of the experimental groups of mice is provided.

(I) Similar experiments as in (H) but comparing IL-18 mRNA electroporation with DRIL18 mRNA electroporation. In one condition, intratumorally treated tumor-bearing mice with IL-12/DRIL18 Pmel-1 cells were BAFT-3 knockout.

(J) Similar experiments as in (H) and (I) performed with OT-I TCR transgenic lymphocytes electroporated with the indicated mRNAs.

Experiments are representative of at least two repetitions. Biological duplicates were performed in the in vitro experiments (A–F). For antitumor efficacy experiments (G–J), each experimental group is composed of six mice. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons were made by one-way or two-way ANOVA tests and log rank tests for Kaplan-Meier survival curves. See also Figures S1–S5 and S10.

The significance is represented with asterisks (∗) according to the following values: p<0.05 (∗), p<0.01(∗∗), p<0.001(∗∗∗) and p<0.0001(∗∗∗∗).

Reportedly, IL-12 and IL-18 synergize to induce IFN-γ production from T cells. In keeping with this notion, our co-electroporated (IL-12 + DRIL18) or mixed single electroporated (IL-12/DRIL18) Pmel-1 T cells released larger amounts of IFN-γ to cell culture supernatants (Figure 1C). Notably, mixed single mRNA-electroporated cells resulted in larger amounts of IFN-γ than co-electroporated cells. This was also confirmed by experiments assessing intracellular IFN-γ, whose expression was also longer in the case of the cell mixture as compared with co-electroporation (Figure 1D). More importantly, IL-18 and especially DRIL18 mRNAs enhanced the cytotoxicity of IL-12-engineered Pmel-1 T cells against ovalbumin-expressing B16 melanoma cells (B16-OVA) (Figure S1D). Cytotoxicity was greater in the case of the IL-12/DRIL18 mixtures than in the case of co-electroporated Pmel-1 lymphocytes (Figure 1E). The potentiated effect on IFN-γ production and release was found to be much higher in the case of the DRIL18 as compared with the IL-18 native sequence when combined with scIL-12. Notably, IFN-γ production seemed to last longer, at least during the first 48 h post-mRNA electroporation (Figure 1F).

We chose Pmel-1 TCR-transgenic T cells35 because they have a low-medium avidity TCR recognizing mouse glycoprotein (gp) 100 and are known to have limited efficacy on adoptive therapeutic transfer,36 even if electroporated to express scIL-12 mRNA.29

In mice bearing 8-day established subcutaneous B16-OVA melanomas in both flanks, we intratumorally injected two doses of control or mRNA-engineered Pmel-1 lymphocytes on days +8 and +11 (Figure 1G). The effect of scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA co-electroporation or the combination of equal quantities of both single mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 lymphocyte cultures was tested for antitumor efficacy. Figure 1H shows that mice treated with the mixed single mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 cells (IL-12/DRIL18) exerted better control of the injected lesion and, more importantly, eradicated the distant untreated lesions as well. Notably, unilateral intratumoral delivery attained better efficacy than intravenous delivery on both tumor lesions (Figure S2A) without any analytical or behavioral signs of toxicity (Figures S2B and S2C). In separate experiments, DRIL18 mRNA in the same setting was better than IL-18 mRNA in terms of efficacy (Figure 1I). Moreover, the distant antitumoral effect was at least partially lost in Batf3−/− mice, which specifically lack cDC1 cells,37 indicating a need for antigen cross-presentation (Figure 1I).38 Similar therapeutic effects were observed when mRNA-electroporated OT-I TCR transgenic lymphocytes that recognize ovalbumin residues were used in a similar bilateral B16-OVA experimental setting (Figures 1G and 1J).

Then, in order to assess the phenotype of the intratumorally adoptively transferred cells, we analyzed tumor cell suspensions of the injected and non-injected tumors as schematized in Figure S3A. In this experiment, higher percentages of IL-12/DRIL18 electroporated pmel-1 cells were found to express IFN-γ, granzyme B, Ki67, CD137, and CD25 (Figure S3B). In both the treated and non-injected tumors, there were signs of functional activation, while fewer pmel-1 cells expressed TOX as a consequence of the electroporation of the mRNAs (Figure S3B). Interestingly, when gating in endogenous CD8+ infiltrating tumor cells, a similar tendency to more functional activation was observed using the same markers (Figure S3C).

In mice completely rejecting their bilateral tumors following therapy with the mixtures of IL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA-engineered Pmel-1 T cells, we observed vitiligo in the area of the injected tumor (Figure S4A). Moreover, after at least 90 days, all those mice showed enhanced T cell-dependent immunity against subcutaneous rechallenges with B16-OVA, which progressed in control tumor-naive mice (Figure S4B).

The B16F10 parental cell line tends to be more refractory to immunotherapy, and treating 6-day established bilateral tumors is very challenging for any immunotherapy.39 In the setting described in Figure S5A, increased efficacy of the mixture of DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNA-electroporated T cells was observed, even if tumors were not completely rejected after significant, but transient, control (Figure S5A). Even when the onset of treatment was postponed until day +8, significant bilateral tumor control was achieved against the B16F10 tumors, which was found to be dependent on IFN-γ as shown by systemic in vivo blockade with a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Figure S5B).

Together, these findings highlight the greater antitumor effect of immunotherapeutic strategies involving adoptive transfer of T cells engineered to express mRNAs for IL-12 and an DRIL18.

Differential gene-expression profiles in scIL-12 versus scIL-12/DRIL18 mRNA-transduced CD8 T cells

We sought to identify the mechanisms that would account for the pronounced antitumor efficacy of the scIL-12/DRIL18 combinations. First, we performed bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of antigen preactivated Pmel-1 CD8 T cell cultures transfected with scIL-12, DRIL18, or mixtures of both RNA-transduced lymphocytes in comparison with mock electroporated cells.

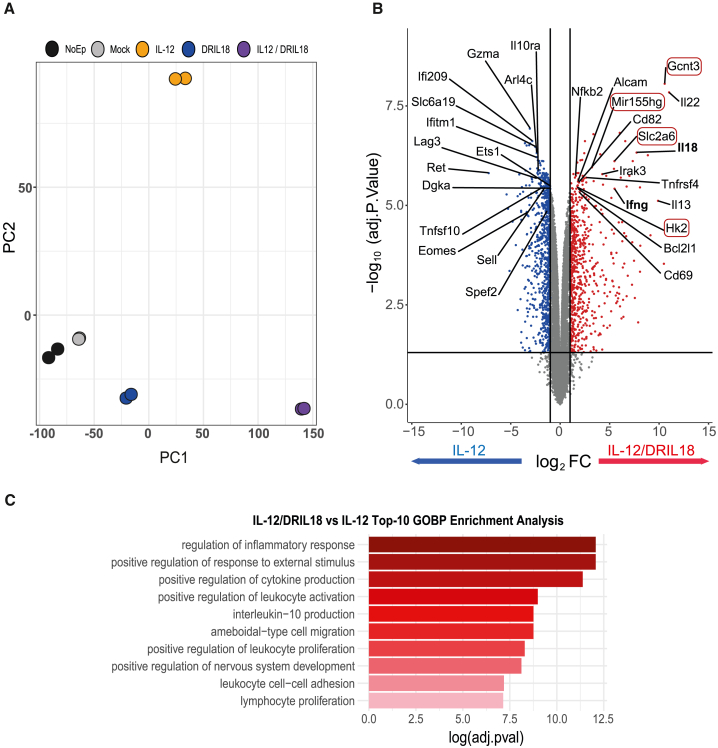

After 24 h of culture, principal component analyses of RNA-seq data indicated that each condition showed a unique transcriptional profile. Importantly, the mix of scIL-12 cells and DRIL18 RNA-transfected cells was particularly different in its transcriptional profile as compared with single transfected Pmel-1 lymphocytes (Figure 2A). Genes whose expression was up- or down-regulated are represented in the volcano plot shown in Figure 2B, when comparing IL-12 single-gene transfer with the one-to-one mixture of Pmel-1 cells transfected with scIL-12 or DRIL18 mRNAs. The rationale was that those genes enhanced by the combination should be important for the improvement in functional performance. Searching the lists of genes, those encoding IL-18 and IFN-γ were found, as expected. We hand-picked several other genes because of their potential function in regulating T cell-dependent responses. These genes are listed in Figure 2B, and the gene ontology functions that were found to be enriched were mostly related to T cell functionality (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

RNA-seq analyses of mRNA electroporated mixed Pmel-1 cells to express scIL-12 or DRIL18

(A) Principal-component analysis of the transcriptomes of 48-h antigen preactivated Pmel-1 cells transfected with the indicated mRNAs. In the case of IL-12/DRIL18, cells were separately electroporated with either single mRNA and mixed together 1:1. RNA-transduced Pmel-1 lymphocytes were cultured for an additional 24 h before retrieving the RNA.

(B) Volcano plot analysis showing genes up-regulated or down-regulated when comparing scIL-12 mRNA with the mixture of Pmel-1 cells electroporated with scIL-12 or DRIL18. Listed genes are those considered of potential functional significance for T cells, and those whose names are surrounded by red rectangles are those that we focused on in subsequent research.

(C) Top 10 biological processes obtained in Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using the up-regulated gene list of IL-12/DRIL18 vs. scIL-12 mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 cells (adjusted P value < 0.05 and Log2FC > 1) against “biological process” ontology. Experiments represent the data of two biological replicates. FC, fold change.

The significance is represented with asterisks (∗) according to the following values: p<0.05 (∗), p<0.01(∗∗), p<0.001(∗∗∗) and p<0.0001(∗∗∗∗).

From the list of up-regulated genes, several caught our attention given their involvement in cytokine physiology (i.e., Il22), metabolic fitness (i.e., Slc2a6, Hk2), surface protein O-glycosylation (Gcnt3), and miR-155hg-mediated gene-expression control.40 With regard to down-regulated genes, Il10ra, Dgka, and Eomes might also have a role because the first two have been involved in attenuating T cell activation,41,42 and Eomes is implicated in the control of differentiation and effector function.43,44

In light of these transcriptional changes, we sought to examine the phenotypic and functional modifications underlying the potent antitumor effect generated by combined scIL-12/DRIL18 mRNAs transfection.

The scIL-12/DRIL18 mRNA combination increases E-selectin adhesion contingent on the differential glycosylation of surface proteins

Among the most prominent genes identified by the RNA-seq of the scIL-12/DRIL18 mRNA combination, our analysis revealed the up-regulated expression of Gcnt3-encoding mucin-type glucosaminyl (N-acetyl) transferase 3, a Golgi glycosyltransferase responsible for the formation of core 2 O-glycans.45 Moreover, additional genes also involved in protein glycosylation were up-regulated (Figure 3A).

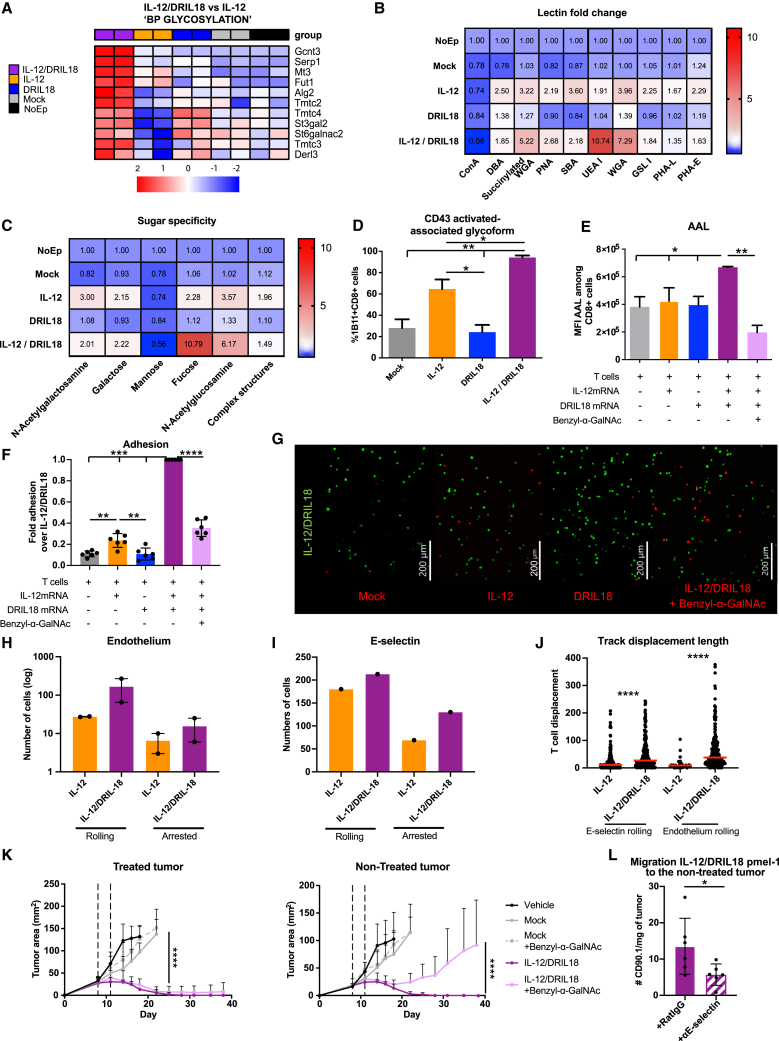

Figure 3.

scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA induce changes in cell-surface glycosylation and generate E-selectin ligands important for efficacy on distant non-injected tumors

(A) Heatmap of the Z-scored log2counts/million (CPM) expression of differentially expressed genes with the indicated mRNAs involved in protein glycosylation showing a prominent enhancement of Gcnt3. “BP GLYCOSILATION” term appears as enriched in the GO analysis (adjusted P value = 0.02180856; q-value = 0.01409151).

(B) Fluorescent-lectin-binding assays represented as a matrix heatmap for binding to Pmel-1 cells transfected with the indicated mRNAs 48 h prior to the assay. Binding is represented as the fold change over non-electroporated counterparts.

(C) Grouping of the lectin-binding assays, according to their primary glycan specificity and the monosaccharide to which they bind. Complex structures indicate N-glycan-linked structures (PHA-L and PHA-E binding).

(D) Immunostaining and flow cytometry analyses of Pmel-1 cells electroporated with the indicated mRNA 48 h prior to the assay to assess the percentage of cells stained with the 1B11 mAb that detects CD43 decorated with core 2 O-glycans.

(E) Flow cytometry for quantification of α(1,3) fucosylated structures by AAL binding and evaluation of fucosylated glycoepitopes in O-glycans by inhibition with benzyl-α-GalNAc.

(F) Comparative E-selectin adhesion assays of IL-12/DRIL18-electroporated cells precultured for 48 h in comparison with the other indicated mRNAs similarly transduced cultured Pmel-1 cells. Comparative results of adhesion in 15-min assays are provided. When indicated, the O-glycosylation inhibitor benzyl-α-GalNAc was added during the 48 h preculture.

(G) Representative images of the endpoint of the adhesion assay with IL-12/DRIL18 cells are in green, while the other transduced and untransduced cells are in red.

(H) Shear stress adhesion assays under flow of the indicated mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 cultures on MS1 mouse endothelium cells preactivated with TNF-α (see also Video S1). The number of Pmel-1 cells rolling or arrested on the endothelium are provided.

(I) Similar experiments as in (H) but performed on recombinant E-selectin attached to the bottom of the chambers.

(J) Length of the tracks of rolling Pmel-1 cells on recombinant E-selectin and endothelial cells in recorded fluorescence microscopy time-lapse videos.

(K) Treatment experiments as in Figure 1H were undertaken on B16-OVA bilateral tumor-bearing mice treated with the indicated mRNA-electroporated pmel-1 cells. In the conditions pointed out, benzyl-α-GalNAc was added during 2-h culture before in vivo transfer to inhibit the O-glycan elongation.

(L) Flow cytometry quantification of CD90.1+ pmel-1 T cells in the contralateral tumor in experiments in which IL-12/DRIL18 mRNA-electroporated pmel-1 cells were injected into the other contralateral tumor. When indicated, mice were given neutralizing anti-E-selectin mAb.

Experiments are representative of at least two repetitions, and one-way ANOVA (D–F and L), two-way ANOVA (K), and Mann–Whitney U (J) tests were used for statistical comparisons. Biological duplicates were performed in experiments (A)–(H). For antitumor efficacy experiments (K and L), we randomly assigned six mice per group. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Con A, Concanavalin A; DBA, Dolichos biflorus lectin; GSL-I, Griffonia simplicifolia lectin I; PHA-E, Phaseolus vulgaris erythroagglutinin; PHA-L, Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin; PNA, peanut agglutinin; SBA, soybean agglutinin; UEA-I, Ulex europaeus agglutinin I; WGA, wheat germ agglutinin.

The significance is represented with asterisks (∗) according to the following values: p<0.05 (∗), p<0.01(∗∗), p<0.001(∗∗∗) and p<0.0001(∗∗∗∗).

Glycophenotyping of RNA-transfected Pmel-1 T cells by flow cytometry using fluorescently labeled plant lectins (Figure 3B) showed considerable changes in the cell-surface glycosylation profile dependent on the introduction of scIL12 and DRIL18 mRNAs. Particularly, Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA-I) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) binding was increased with respect to non-transfected cells, indicating that α(1,2)/α(1,3) fucosylated glycoepitopes (UEA-I) and N-acetylglucosamine-containing structures were increased in these cells (Figure 3C). All together, these results led us to hypothesize that scIL12 and DRIL18 mRNAs transduction increased the expression of core 2 O-glycans with terminal sialyl Lewis X (sLex) structures bearing (1,3) fucose.

Based on these findings, we then evaluated the expression of the activation-associated glycoform of CD43,46 which is highly decorated with core 2 O-glycans, by flow cytometry. Using a specific antibody (1B11),47 we observed that expression of the 1B11 epitope was increased following transfection with IL-12 mRNA and was clearly more prominent when IL-12 mRNA was combined with DRIL18 mRNA (Figure 3D). Furthermore, determination of (1,3) fucosylated glycoepitopes by flow cytometry with Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) showed a clear increase in their exposure on electroporation of the scIL-12/DRIL18 cytokine mRNAs (Figure 3E). Notably, a decrease in AAL staining was observed when we inhibited O-glycan elongation using benzyl-α-GalNAc,48 thus substantiating the increased expression of (1,3) fucosylated O-glycans on the surface of the RNA-transferred T cells.

Given that sLex is a well-known ligand of E-selectin,49 we performed competitive adhesion assays of transfected T cells to plastic-bound recombinant E-selectin. Figure 3F shows the enhanced adhesion of scIL-12/DRIL18 mRNA-transfected Pmel-1 cells to E-selectin. This effect was sensitive to inhibition by pre-exposure to Benzyl-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-α-D-galactopyranoside (benzyl-a-GalNAc), thus verifying the functional relevance of O-glycosylation in this effect. Increased competitive adhesiveness was evidenced by quantifying adhesion in microphotographs of 15-min adhesion assays (Figure 3G).

Given the reported involvement of E-selectin in leukocyte rolling,50,51 we performed shear stress adhesion assays of fluorescently labeled lymphocytes on surface-attached tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-activated MS1 murine microvascular endothelial cells that expressed E-selectin. Figures 3H and 3I and Video S1 show that scIL-12/DRIL18 Pmel-1 cells rolled and arrested more frequently and intensely than scIL-12 single mRNA-transduced Pmel-1 T cell cultures both on microvascular endothelial cells (Figure 3H) and on plate-bound recombinant E-selectin (Figure 3I). As a consequence, the lengths of the tracks of the rolling cells were longer in such time-lapse fluorescence microscopy videos (Figure 3J). Hence the mRNA-transduced cytokines, especially IL-18, contribute to modifying adhesion of T cells to the endothelium, via modulation of their cell-surface O-glycosylation profile.

scIL12/DRIL18 mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 cells are green labeled, whereas scIL-12 single-electroporated Pmel-1 cells are red labeled.

Next, we addressed whether the increased O-glycosylation could have an effect on the therapeutic efficacy. As shown in Figure 3K, preculture of the mRNA-electroporated pmel-1 cells with benzyl-α-GalNAc reduced the abscopal efficacy while preserving the effectiveness on the directly injected tumor. This could be consistent with the less efficient migration into the distant tumor. Indeed, E-selectin in vivo blockade with a neutralizing mAb reduced the amount of adoptively transferred mRNA-electroporated pmel-1 T cells relocated to the distant tumor (Figure 3L).

DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNAs improve CD8 T cell metabolism involving glucose and mitochondrial fitness

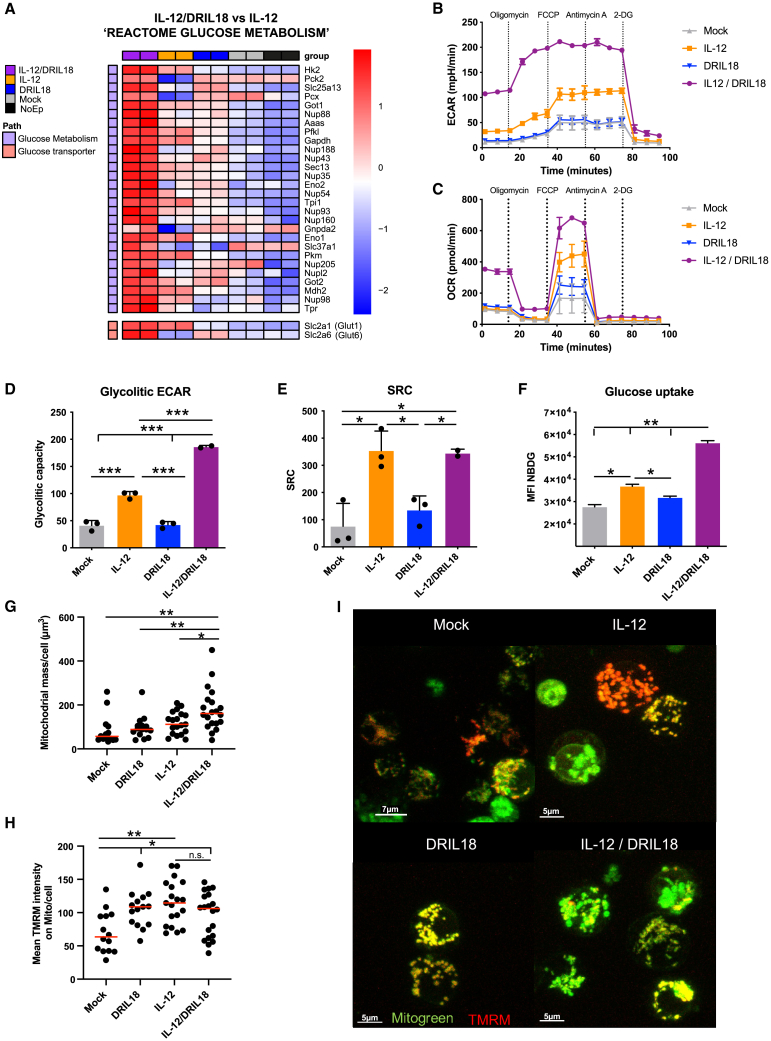

In our search for additional genes that could be up-regulated by DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNAs, we detected several genes encoding enzymes critical for glycolysis and glucose transport (Figure 4A). These include genes encoding hexokinase-2 and glut-6. In comparative Seahorse experiments assessing acidification of the medium, a stronger glycolytic rate was found that remained unaffected by drugs targeting mitochondrial functions but was drastically reduced by the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose (Figure 4B). Moreover, when we monitored the O2 consumption rate, higher levels of baseline and maximal mitochondrial respiration capacity were noted in mixtures of T cells mRNA-engineered to expressed both cytokines (Figure 4C). Such results are interpreted as higher glycolysis rates (Figure 4D) and enhanced spare respiratory capacity (Figure 4E) of the mitochondria, which was mainly stimulated by the scIL-12 mRNA, while the prominent effect on glycolysis was more dependent on the IL-12/DRIL18 combination. Enhanced glucose metabolism needs more efficient glucose uptake mediated by membrane transporters, which was assessed using a fluorescent glucose probe (Figure 4F). The effect on hexokinase-II expression was confirmed by immunostaining and flow cytometry at the protein level (Figure S6A) in pmel-1 cells recovered 24 h following intratumoral delivery. In cell suspensions from individual tumors, positive correlations of average hexokinase-II expression were found with granzyme B and CD25, whereas negative correlations were observed with TOX and active caspase-3 (Figure S6B). Furthermore, we used confocal microscopy to determine variations in mitochondrial mass and transmembrane potential. Although the combination of cytokine mRNAs further enhanced mitochondrial mass (Figures 4G and 4I), transmembrane potential was similarly enhanced by either scIL-12 or DRIL18 (Figures 4H and 4I). Taken together, these results show it is likely that the enhanced glucose metabolism and mitochondrial respiration may underlie the enhanced antitumor effect of T cells driven by scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA.

Figure 4.

DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNAs synergize to enhance glucose and mitochondrial metabolism in CD8 T cells

(A) Heatmap showing the Z-scored log2CPM expression of the differentially expressed genes functionally related to glucose metabolism. The glucose metabolism pathway appears as enriched in the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; p-value = 0.02511886; Normalized enrichment score (NES) = 1.465072). We added two glucose transporters that were differentially expressed (Glut1 and Glut6) because of their relevance.

(B) Extracellular acidification in Seahorse assays over time of Pmel-1 cells electroporated with the indicated mRNAs 24 h prior to the assays. During the time course, the indicated compounds were added.

(C) Oxygen consumption over time of the same lymphocyte cultures.

(D) Assessment of the glycolytic rate based on acidification and the use of 2-deoxyglucose to stop glycolysis.

(E) Ratio between maximal and baseline mitochondrial respiration.

(F) Glucose intake based on internalization of the 2-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-il)amino)-2-desoxiglucose (NBDG) fluorescent probe by flow cytometry and measured with arbitrary units of mean fluorescent intensity (MFI).

(G–I) Pmel-1 cells were stained with probes staining mitochondria and sensitive to mitochondrial transmembrane potential and imaged by confocal fluorescent microscopy. Quantification of mitochondrial mass per cell (G) and an estimate of transmembrane mitochondrial potential (H) are provided. Representative confocal images are shown in (I).

Experiments were repeated at least twice, and statistical comparisons were performed with one-way ANOVA tests. Biological duplicates were performed in experiments (A)–(F). Data are represented as mean ± SD. See also Figure S6.

The significance is represented with asterisks (∗) according to the following values: p<0.05 (∗), p<0.01(∗∗), p<0.001(∗∗∗) and p<0.0001(∗∗∗∗).

DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNA transfer control cytokine production and miR-155

To study whether the combination of Pmel-1 T cells transferred with mRNAs encoding scIL-12 or DRIL18 could up-regulate the cytokines implicated in the antitumor effects, we used commercial multiplex assays to analyze concentrations of several cytokines released into the culture supernatants. As shown earlier, IFN-γ was markedly increased in the 24-h supernatants of T cell mixtures transfected with the IL-12/DRIL18 mRNAs. This was also the case for interleukin-15 (IL-15), CXCL10, CCL3, and TNF-α as measured in the supernatants. Notably, type I IFNs, which are crucial for CD8 T cell responses,52 were also up-regulated in those culture supernatants (Figure S7A).

Interestingly, the combination of scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNAs was also able to up-regulate cytokines whose roles maybe detrimental for antitumor T cell immunity. These include the unexpected RNA-seq hit interleukin-22 (IL-22) (Figure S7B) that reportedly protects malignant epithelial cells,53 as well as interleukin-10 (IL-10)41 and interleukin-6 (IL-6)54 (Figure S7B). However, IL-10 might also induce positive effects on cytotoxic lymphocyte (CTL) activation and differentiation.55,56 In ex vivo cytotoxicity assays, IFN-γ blockade abrogated the cytotoxicity of the DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNA Pmel-1 mixed cultures on B16-OVA targets, whereas IL-22 neutralization had negligible effects (Figure S7C).

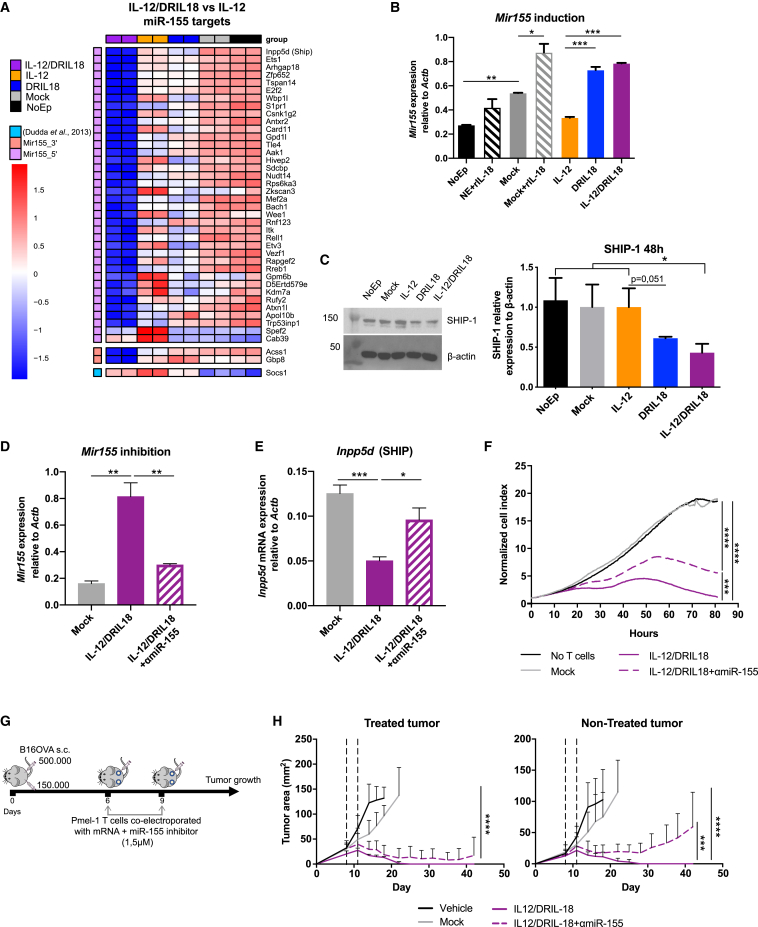

Among the genes that were substantially up-regulated in the RNA-seq studies of the scIL-12/DRIL18 combination, miR-155 emerged as an attractive mediator able to regulate multiple downstream target genes. In fact, co-cultures with scIL-12- and DRIL18-producing cells showed down-regulation of several miR-155 target genes (Figure 5A). Interestingly, increased expression of miR-155 was found to be mainly dependent on IL-18 mRNA, as shown by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Mixed scIL-12/DRIL18 electroporated Pmel-1 cells upregulate functional miR-155 that is involved in the therapeutic efficacy

(A) Heatmap showing down-regulation of the Z score log2CPM of differentially expressed genes reported as miR-155 target genes in the mixes of scIL-12/DRIL18 Pmel-1 cells. GSEA shows enrichment in miR-155-5′ targets gene set (p.val = 0.0009229154; NES = −1.654717). We added more differentially expressed (DE) genes genes that are targets of miR-155-3′ (Acss1 and Gbp8) and Socs1, a well-known target of miR-155-5′ not described in the M3 category.

(B) Confirmation of the up-regulation of Mir155 by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

(C) Immunoblot analysis of SHIP-1 expression in the indicated Pmel-1 mRNA-transfected cells as compared with β-actin. Relative densitometry data are shown in the bar graph.

(D) An antagomir RNA was co-electroporated to induce the degradation of miR-155 (αmiR-155) as compared with the negative control antagomir co-electroporated with IL-12/DRIL18 mRNAs.

(E) The antagomir partially rescued the mRNA expression of Inpp5d (SHIP) in the IL-12/DRIL18 pmel-1 cells as assessed by qRT-PCR.

(F) IL-12/DRIL18 pmel-1 cells co-electroporated with the antagomir degrading miR-155 exhibited less efficacious ex vivo cytotoxicity against B16-OVA as assessed by xCELLigence assays.

(G and H) Efficacy experiments in mice bearing bilateral B16-OVA tumors that show that co-electroporation of the antagomir (αmiR-155) reduced the bilateral efficacy of IL-12/DRIL18 electroporated pmel-1 cells injected to one of the tumors. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA (B–E) or two-way ANOVA tests (H). Experiments were repeated at least twice.

Biological duplicates were performed in experiments (A)–(F). For antitumor efficacy experiments (G and H), we randomly assigned six mice per group. Data are represented as mean ± SD. See also Figures S7 and S8.

The significance is represented with asterisks (∗) according to the following values: p<0.05 (∗), p<0.01(∗∗), p<0.001(∗∗∗) and p<0.0001(∗∗∗∗).

An important miR-155 target gene controlling intracellular signaling in T cells is SHIP-1, which dephosphorylates inositol phosphates and counter-regulates phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activity.57,58 Western blot analysis showed down-regulation of SHIP-1 protein expression following mRNA transfer of both cytokines (Figure 5C). More abundant cytokine production and down-regulation of signal regulators of costimulatory molecules may help explain the positive combined effects of scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA transfer.

Next, an antagomir RNA sequence was used to reduce the expression of miR-155 on co-electroporation in IL-12/DRIL18 pmel-1 cells (Figure 5D). Such procedure also rescued the expression of Inpp5d (SHIP) as substantiated by qRT-PCR 24 h later (Figure 5E). Indeed, the antagomir co-electroporation also led to a decrease of secretion of IFN-γ, IL-15, IFN-α, CXCL10, and TNF-α (Figure S8A), although it did not modify the secretion of IL-6 or IL-22 (Figure S8B).

Notably, the antagomir co-electroporation attenuated the effectiveness of IL-12/DRIL18 pmel-1 lymphocytes to ex vivo kill B16-OVA cells in xCELLigence assays (Figure 5F) and reduced the in vivo therapeutic efficacy in the bilateral B16-OVA tumor model as a result of progression of the contralateral tumor lesions not directly injected with the mRNA-engineered T lymphocytes (Figures 5G and 5H).

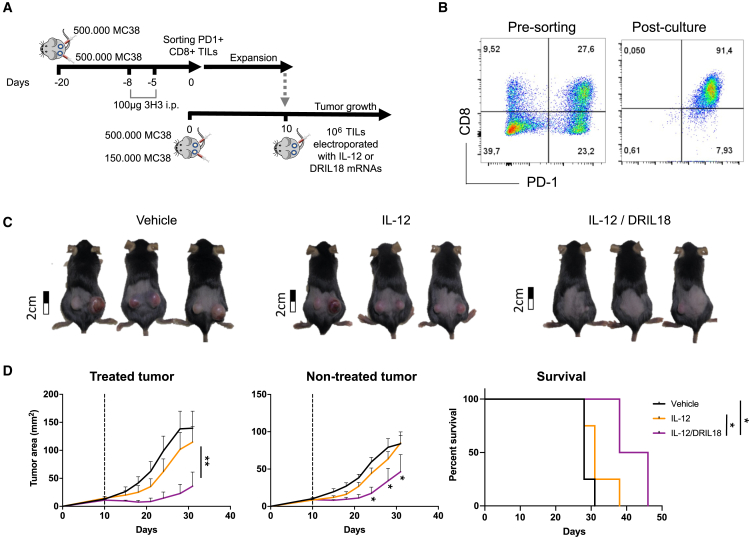

DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNAs synergistically enhance the performance of TILs in adoptive T cell therapy

TILs constitute a modality of adoptive T cell therapy with excellent clinical results in metastatic melanoma patients.59 To model such activity in mice, we have reported a method to raise TIL cultures from sorted PD1+CD8+ TILs.60 Before harvesting TILs, mice bearing MC38-derived tumors were treated with an anti-CD137 mAb to increase the yield of these lymphocytes. We electroporated T cell cultures either with mRNA encoding DRIL18 or scIL-12 and then used them separately or mixed. These TIL-derived cultures were used to intratumorally treat mice bearing bilateral MC38 tumors with one single dose of electroporated T cells or an equal-number mixture of lymphocytes electroporated with each cytokine mRNA (Figure 6A). Cultures were rich in lymphocytes co-expressing PD1 and CD8 (Figure 6B) and induced prominent bilateral therapeutic effects even in mice treated with only one single intratumoral dose given on day +10 after engraftment with tumor cells (Figures 6C and 6D). Such effects were considerably higher than those observed by scIL-12 mRNA single transfection (Figure 6D). Thus, scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA transfection act synergistically to increase the efficacy of adoptive TIL immunotherapy in vivo.

Figure 6.

Mixing tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cultures electroporated with scIL-12 mRNA and DRIL18 mRNA synergize for intratumoral adoptive T cell therapy

(A) Scheme of generation of TIL cultures from MC38 tumors and treatment of mice bearing bilateral MC38 tumors following mRNA electroporation.

(B) Dot plot graphs of cell suspensions derived from tumors and TILs post-culture stained with anti-PD1 and anti-CD8 mAbs.

(C) Representative photographs of treated mice with the indicated mRNA-transfected TILs on day +30.

(D) Tumor size follow-up and survival of the indicated groups of mice.

Log rank tests were used to compare survival curves, and two-way ANOVA tests were used to compare tumor growth. Experiments were repeated three times, and we randomly assigned six mice per group. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

The significance is represented with asterisks (∗) according to the following values: p<0.05 (∗), p<0.01(∗∗), p<0.001(∗∗∗) and p<0.0001(∗∗∗∗).

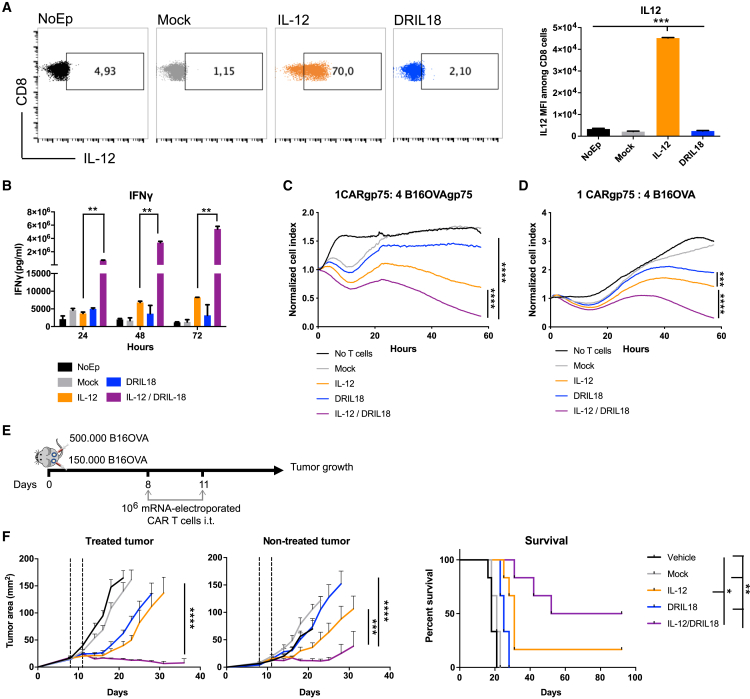

Greater antitumor activity of CAR T cells transduced with scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNAs on intratumoral delivery

CAR T cells recognizing the gp75 mouse melanosomal antigen have been described.61 The CAR construct carries an EGFP reporter gene to monitor the gene transfer of splenocytes that were preactivated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. CAR gene transfer attained over 90% transduction efficiency using a retroviral vector (Figure S9A). Such cultures could be electroporated with mRNAs undergoing only a moderate loss of their viability (Figure S9B). These mRNA-electroporated T cells were able to express scIL-12, which was detected intracellularly at the protein level (Figure 7A). In these CAR T cell cultures, scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNAs also synergized to induce the secretion of high amounts of IFN-γ into the culture supernatants (Figure 7B). Moreover, the combination of IL-12 and DRIL18 mRNA-modified CARs synergized in ex vivo toxicity assays to kill B16-OVA target cells stably transfected to overexpress gp75 (Figure 7C) or even untransfected B16-OVA melanoma cells (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Improved therapeutic efficacy of intratumoral injections with gp75-recognizing CAR T cells following scIL-12/DRIL18 mRNA electroporation

(A) Intracellular IL-12 protein expression following electroporation of the indicated mRNAs into anti-gp75 mouse CAR T cells. MFIs are provided in the bar graph.

(B) IFN-γ concentrations over time in the indicated CAR T cell cultures, including the mixes of DRIL18 and scIL-12 CAR T cells.

(C and D) Ex vivo cytotoxicity performed over time with the indicated mRNA-electroporated CAR T cells at a 1:4 ratio against gp75-transfected B16-OVA (C) and non-transfected B16-OVA (D).

(E) Scheme of the experiments of mice bearing bilaterally B16-OVA tumors and treated intratumorally with the different mRNA-electroporated CAR T cells or the scIL-12/DRIL18 mixture.

(F) Tumor size follow-up of CAR T-injected and contralateral non-injected tumors with the indicated mRNA-electroporated or mock CAR T cells. Survival of the treatment groups of mice is provided.

Experiments were repeated twice, and statistical comparisons were made with one-way ANOVA tests (A and B), two-way ANOVA tests, and log rank tests to compare tumor growth and survival, respectively. Biological duplicates were performed in experiments (B)–(D). For antitumor efficacy experiments (E and F), we randomly assigned six mice per group. Data are represented as mean ± SD. See also Figure S9.

The significance is represented with asterisks (∗) according to the following values: p<0.05 (∗), p<0.01(∗∗), p<0.001(∗∗∗) and p<0.0001(∗∗∗∗).

Using these mRNA-transduced CAR T cell cultures, we set up experiments to treat bilaterally B16-OVA-bearing mice in which only one of the tumors was intratumorally treated on days +8 and +11 (Figure 7E). The mixtures of CAR T cells transfected with either cytokine mRNA showed a synergistic antitumor effect against directly injected and non-injected contralateral tumors (Figure 7F).

Collectively, these data highlight the therapeutic value of mRNA transient cytokine gene transfer, especially in those approaches showing synergistic effects to enhance the functional performance of CAR T cells, at least for local delivery strategies.

Discussion

In previous work, we showed the efficacy of using scIL-12 mRNA-transfected TCR-transgenic CD8 T cells for repeated intratumoral delivery.29 Such efficacy was extended to mouse and human TILs.29 The repeated intralesional strategy is considered feasible in the clinic;62 hence we sought to improve its efficacy with the addition of other transgenes. Our screenings led to the identification of IL-1863 as a suitable synergistic partner for the IL-12 mRNA transgene.

Studies of these synergistic effects using IL-18- and scIL-12-encoding mRNAs revealed that mixing single mRNA-transfected T cells with either DRIL18 or scIL-12 by electroporation was more efficacious than co-electroporating both mRNAs in the same cells. The reason seems to be related to a competitive reduction of mRNA expression of the two optimized mRNAs in the same cell because of as yet poorly understood reasons. The mixtures of T cells with different electroporated mRNAs seem to be advantageous in this system and would permit fine-tuning of the proportions of mixed cells to optimize efficacy and safety.

Using Pmel-1 anti-gp100 and anti-OVA OT-I TCR-transgenic cells35 transduced with DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNAs, we observed unprecedented efficacy not only against the treated tumor but also against distant well-established tumor lesions. The main rationale for using an intratumoral delivery route is to provide immediate antigen contact of all the injected T lymphocytes at the time point when the mRNA-encoded transgenes are most prominently expressed. Killing a fraction of tumor cells in an immunogenic fashion to create an in situ vaccine is also desirable.64,65 Thus, the strategy may be potentiating cross-priming and epitope antigen spreading66 as we have previously shown.29 The importance of recruiting a polyclonal endogenous T cell response is paramount, for instance, to avoid escape of antigen-loss variants. Of important note, IL-12/DRIL18 direct intratumoral delivery of the naked mRNA as recently reported24 was less effective than intratumoral delivery of the electroporated tumor-specific CD8 T cells with the same mRNAs (Figure S10).

From the injection site, T cells would need to reach the circulation in order to gain access to distant metastatic sites. In the case of clinical application, intratumoral delivery and systemic infusion could be combined. Local delivery of adoptive T cell transfer is gaining clinical momentum for brain tumors32,33 and intracavitary malignances34 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03054258) and has shown reasonable safety and efficacy in a number of clinical trials.31 For clinical translation of the intratumoral route, image-guided injection62 or the use of implanted surgical catheters32,33 are feasible options.

One key question was to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the observed remarkable synergy. Notably, we used a mutant form of IL-18 that is not repressible by IL-18BP, thereby bypassing this regulatory barrier to achieve maximal effects.24,26 Indeed, large amounts of IFN-γ were secreted by the mRNA-engineered T cells, and IFN-γ was shown to be essential to attain maximal therapeutic efficacy. Using RNA-seq experiments, we found a number of DRIL18-regulated transcripts potentially underpinning the enhanced functional performance of the engineered CD8 T cells. We interrogated differential glycosylation of cell-surface proteins following discovery of a prominent up-regulation of the Gcnt3 glycosyltransferase. We found considerable remodeling of glycosylation, which enabled expression of E-selectin ligands on the surface of T cells. Given the broad impact of glycosylation on T cell function, including cell adhesion and trafficking,67,68 we examined the biological relevance of scIL-12/DRIL18-driven glycan changes in T cell adhesion assays. Interestingly, changes in the O-glycosylation profile resulted in enhanced adhesion of T cells to microvascular endothelial cells. Moreover, inhibition of O-glycan elongation with benzyl-α-GalNac resulted in less efficacy on in vivo intratumoral treatments observed in the non-injected tumors. This seems to be associated with less efficient migration to the contralateral tumor lesions, as shown on mAb-mediated E-selectin blockade.

In search of the additional mechanisms underlying the potent antitumoral effects of DRIL18- and scIL-12-engineered Pmel-1, we also explored their hierarchical modulation of secondary cytokines. In fact, several cytokines were found to be up-regulated when DRIL18 and scIL-12 acted in concert. These include IL-15 and type I IFNs, both known to regulate the function and survival of cytotoxic T lymphocytes.69,70 These and other induced cytokines probably contribute in a paracrine or autocrine fashion for the overall antitumor efficacy. Notably, up-regulation of miR-155 by scIL-12 and DRIL18 mRNAs successfully reduced SHIP-1 and SOCS-1 expression, potentially enhancing responsiveness to costimulatory molecules engaging PI3K,58 as well as responsiveness to homeostatic and inflammatory cytokines.57,71,72 Indeed, the expression of miR155hg is reportedly associated with better survival in several malignancies and with signs of more prominent infiltration by immune cells.40 Co-electroporation of an antagomir inducing the degradation of miR-155 established the role of miR-155 in the contralateral antitumor effect associated with increased ex vivo cytotoxicity and cytokine production. The connection of miR-155 induction and IL-12/DRIL18 stimulation in terms of mechanism remains elusive but might offer other opportunities for intervention.

Interestingly, we also found that DRIL18 and scIL-12 mRNAs induced changes in the glucose metabolism of T cells, including enhanced glycolysis and mitochondrial function. Indeed, T cell metabolic fitness is considered key for the success of adoptive T cell therapy and the antitumor performance of T cells,73,74,75 especially in the case of hypoxic solid tumors.76 Therefore, we found that IL-18 enhances CTL responses, and that the DRIL18 variant excels at performing such a function.

When envisioning the behavior of mixed T cell populations injected intratumorally, it is expected that they will produce high quantities of the synthetic mRNA-encoded cytokines. Such cytokines would exert autocrine and paracrine effects on injected T cells and presumably also on endogenous T and NK cells, which also express receptors for IL-12 and IL-18. In this context, cytotoxic tumor cell death will take place fostering inflammation and making tumor antigens available for cross-presentation.77 Notably, cDC1-deficient BATF-3 knockout (KO) mice are resistant to the systemic effects of this immunotherapy strategy. The artificial production of IL-12 by the Pmel-1 cells probably bypasses one of the key functions of cDC1, which is IL-12 production, but not cross-presentation itself.78 In addition, high local amounts of IFN-γ are expected to acutely exert antitumor effects79 and foster antigen presentation80 but might also turn on immunosuppressive feedback mechanisms such as Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and Idoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO-1) expression.81

In our previous report with scIL-12 mRNA, we described active T cell trafficking from the injected to the non-injected tumor sites. The induction of E-selectin ligands by the combination of scIL-12/DRIL18 mRNAs should help mediate these processes, at least facilitating rolling and arrest on tumor endothelial cells for extravasation in a concerted function with leukocyte integrins.82 Indeed, changes in O-glycosylation profiles were found to be underpinning the bilateral tumor efficacy.

Our proof-of-concept experiments with TILs and CAR T cells showed remarkable efficacy on single-mRNA electroporation of scIL-12 and DRIL18 and mixing such lymphocyte cultures for subsequent intratumoral delivery. These approaches are clinically feasible. Our current IND-oriented research involves mainly the electroporation of TILs for repeated intratumoral and systemic delivery using frozen batches of the cell therapy products. The strategy can also work with CAR T cells recognizing tumor antigens in solid tumors. The transient expression of the transgenes in the form of mRNAs was well tolerated in mice, and intratumoral release represents an excellent choice to mitigate systemic cytokine-mediated side effects. Repeated injection would be feasible using frozen aliquots, and intratumoral delivery is also feasible and likely to reduce the number of cells in the required lymphocyte doses. In the case of CAR T immunotherapy, repeated local treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in ovarian cancer patients with anti-mesothelin CAR T cells makes sense,83 and using the intratumoral route with anti-mesothelin CAR T cells has been already clinically pioneered by the group of Michael Sadelain34 in the case of malignant mesothelioma. Notably, IL-12 mRNA-engineered OT-I cells have been recently reported to be efficacious for models of peritoneal carcinomatosis when they are intraperitoneally delivered.84 Repeated local treatments with these CAR T cells engineered with cytokine-encoding mRNAs make special sense.

In conclusion, we report on a substantial improvement of an adoptive T cell therapy strategy based on mRNA transient gene transfer and repeated intratumoral delivery. The synergistic immunobiology of IL-12 and IL-18, best represented in the form of DRIL18, holds promise for efficacious outcomes in the treatment of metastatic cancer patients.

Limitations of the study

In spite of the fact that experimental antitumor efficacy has been demonstrated with TILs, CAR T cells, and TCR-transgenic mouse T cells, it is essential to confirm our results in other experimental models of adoptive T cell therapy. The mouse immune system is similar to a certain degree to the human one. However, the results obtained in mice frequently do not reproduce the clinical reality.

Furthermore, our mRNA electroporation strategy has a limitation, which is the inability to productively electroporate multiple mRNAs to the same T cell. The expression of each protein decreased when we tried to co-electroporate. Improvements in the mRNA design or in the electroporation techniques could optimize such results toward clinical development.

Glycosylation changes generating E-selectin ligands, miR155, cytokines, and metabolic improvements are clearly involved mechanisms underlying efficacy, but other yet to be identified factors may contribute.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse CD3 | BioLegend | Clone 17A2; Cat# 100223; RRID: AB_312877 |

| Anti-mouse CD28 | BioLegend | Clone 37.51; Cat# 102112; RRID. AB:389326 |

| Anti-mouse CD8 BV510 | BioLegend | Clone 53–6.7; Cat# 100751; RRID: AB_2561389 |

| Anti-mouse CD8 AF647 | BioLegend | Clone 53–6.7; Cat# 100724; RRID:AB_389326 |

| Rat Anti-CD8 PE-Cy7 | BD Biosciences | Clone:53–6.7; Cat#552877; RRID:AB_394506 |

| Anti-CD137 (3H3) for in vivo use | BioXcell | Clone 3H3; Cat# BE0239; RRID:AB_2687721 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 BV421 | BioLegend | Clone GK1-5; Cat# 100438; RRID: AB_11203718 |

| Anti-mouse IL-12/IL-23 p40 PE | BioLegend | Clon C15.6; Cat# 505204; RRID: AB_315368 |

| Anti-mouse IFNγ for in vivo use | BioXcell | Clone XMG1.2; Cat# E0055; RRID:AB_1107694 |

| Anti-mouse IFNγ AF647 | BioLegend | Clone XMG1.2; Cat# 505814; RRID:AB_493314 |

| Anti-mouse IFN-gamma BV785 | BioLegend | Clone: XMG1.2; Cat#505838; RRID:AB_2629667 |

| Anti-mouse CD279 (PD1) FITC | BioLegend | Clone 29F.1A12; Cat# 135214; RRID:AB_10680238 |

| Anti-SHIP1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Polyclonal; Cat# 2728; RRID:AB_2126244 |

| Anti-βactin | Sigma-Aldrich | Polyclonal; Cat# A2066; RRID:AB_476693 |

| PE anti-mouse CD43 Activation associated glycoform | BioLegend | Clone 1B11; Cat# 121207; RRID:AB_493389 |

| Anti-mouse affinity purified IL-22 | R and D Systems | Polyclonal; Cat# AF582, RRID:AB_355457 |

| InVivoMAb anti-mouse E-selectin (CD62E) | BioXCell | Clone 9A9; Cat#BE0294; RRID:AB_2687816 |

| Rb mAb to Hexokinase II AF647 | abcam | Cat#ab237314 |

| TOX monoclonal antibody, PE, eBioscience | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Clone: TCRX10; Cat#12-6502-80; RRID:AB_10853657 |

| Anti-mouse CD25 APC | BioLegend | Clone: PC61; Cat#102012; RRID: AB_312861 |

| Anti-mouse CD137 BV421 | BD Biosciences | Clone: 1AH2; Cat#740033; RRID:AB_2739805 |

| Granzyme B monoclonal antibody, FITC, eBioscience | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Clone: NGZB; Cat#11-8898-82; RRID:AB_10733414 |

| Anti-mouse Ki-67 Alexa Fluor® 700 | BioLegend | Clone: 16A8; Cat#652420; RRID:AB_2564285 |

| Anti-Rat CD90/mouse CD90.1(Thy-1.1) BV510 | BioLegend | Clone: OX-7; Cat#202535; RRID:AB_2562643 |

| Anti-mouse CD90.2 (Thy1.2) BV605 | BioLegend | Clone: 30-H12; Cat#105343; RRID:AB_2632889 |

| Active Caspase-3 PE | BD Bioscience | Clone: C92-605; Cat#550914; RRID:AB_393957 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| ElectroMAX™ DH10B | Invitrogen | Cat#18290015 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Recombinant human IL-2 (Proleukin) | Novartis | Cat#CN70389 |

| Percoll | GE Healthcare | Cat#17-0891-01 |

| Recombinant mouse IL-7 | Immunotools | Cat#12340075 |

| Recombinant mouse IL-15 | Immunotools | Cat#12340155 |

| Recombinant mouse E-selectin-Fc | BioLegend | Cat#755504 |

| Recombinant human TNFα | Peprotech | Cat#210-TA-020 |

| Cytofix/Cytoperm fixation permeabilization kit | BD Biosciences | Cat#554714 |

| CellTracker Orange CMRA Dye | Invitrogen | Cat#C34551 |

| CellTracker Green CMFDA Dye | Invitrogen | Cat#C7025 |

| 7AAD Viability staining solution | BioLegend | Cat#79993 |

| Zombi NIR Fixable viability Kit | BioLegend | Cat#54-423-106 |

| Mitotracker green | ThermoFisher | Cat#M7514 |

| Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Kit (TMRM) | Merck | Cat#MAK159-1KT |

| hgp100 (25–33) peptide | Genscript | Cat#RP20344 |

| OVA (257–264) peptide | Invivogen | Cat#vac-sin |

| DNAse I | Merck | Cat#1128493001 |

| HindIII digestion enzyme | New England Biolabs | Cat#R0104S |

| Benzyl-α-GalNAc | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#200100 |

| 2-NBDG | Cayman | Cat# 186689-07-6 |

| Collagenase-D | Roche | Cat#11088866001 |

| Ficoll Paque | Fisher Scientific | Cat#17144003 |

| Lectin kit I-Fluorescein | Vector labs | Cat# FLK-2100 |

| Lectin kit II-Biotinylated | Vector labs | Cat# BK-2100 |

| AAL lectin-Biotinylated | Vector labs | Cat# B-1395-1 |

| Protamine-sulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P4020 |

| M-MLV | Invitrogen | Cat#28025-013 |

| iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix | BIO-RAD | Cat#170-8882 |

| Ringer Lactado | Grifols | Cat#637066 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Mouse CD8+ T cell isolation kit | Miltenyi Biotech | Cat#130-104-075 |

| T7 mScript™ Standard mRNA Production System | CellScript | Cat#C-MSC100625 |

| RNeasy Micro Kit | Qiagen | Cat#74004 |

| Endofree plasmid maxi kit | Qiagen | Cat#50912362 |

| mouse IFNγ OptEIA set | BD Biosciences | Cat#551866 |

| Mouse IL-12 (p70) ELISA set | BD Biosciences | Cat#555256 |

| ELISA Mouse Duoset IL22 | R and D Systems | Cat#DY582-05 |

| Mouse ProcartaPlex Mix&Match 13-plex | Thermofisher | Cat#PPX-13MX2W9XU |

| Maxwell RSC simplyRNA tissue | Promega | Cat#AS1340 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNAseq data | This paper | GEO: GSE206195 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Mouse: MC38 | In house | N/A |

| Mouse: B16OVA | In house (Weigelin et al., 2015)85 | N/A |

| Mouse B16F10 | In house (Weigelin et al., 2015)85 | N/A |

| Mouse: B16OVAgp75 | In house (Weigelin et al., 2015)85 | N/A |

| Mouse: MS-1 | ATCC | RRID:CVCL_6502 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6 | Envigo | Strain: C57BL/6JOlaHsd |

| Mouse Pmel1 TCR transgenic | Jackson Laboratory | Strain: 005023 |

| Mouse: BATF3−/− on C57BL/6 background | In house | N/A |

| Mouse: CD45.1 on C57BL/6 background | In house | N/A |

| Mouse: OT-I TCR transgenic | Jackson Laboratory | Strain: 003831 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Mouse single-chain IL-12 mRNA | In house (Etxeberria et al., 2019)29 | N/A |

| Mouse IL-18 mRNA | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse DRIL18 mRNA | (Zhou et al., 2020)26 | N/A |

| Mir155 mouse primers | This paper | N/A |

| Inpp5d (SHIP) mouse primers | This paper | N/A |

| miRCURY LNA™ miRNA Power Inhibitor Control. Negative control A | Qiagen | Cat#339136 YI00199006-DDA |

| miRCURY LNA™ miRNA Power Inhibitor MMU-MIR-155-5P | Qiagen | Cat#339131 YI04101319-DDA |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pRubiC- EGFP-P2A-CAR retroviral vector | In house (Conde et al., 2021)61 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism 8 | GraphPad Prism | https://www.graphpad.com; RRID:SCR_002798 |

| FlowJo V10 | Tree Star Inc. |

https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo; RRID:SCR_008520 |

| CytExpert Software | Beckman Coulter |

https://www.mybeckman.com.br/flow-cytometry/research-flow-cytometers/cytoflex/software RRID:SCR_017217 |

| RTCA Software | ACEA Biosciences Inc. |

https://aceabio.com/product/rtca-dp/; RRID:SCR_014821 |

| Imaris 9 | Bitplane |

http://www.bitplane.com/imaris/imaris; RRID:SCR_007370 |

| R (v4.1.1) | Bioconductor |

https://www.bioconductor.org; RRID:SCR_006442 |

| FastQC tool (v0.11.9) | Babraham Bioinformatics |

http://www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/fastqc; RRID:SCR_014583 |

| Trimmomatic (v.0.39) | (Bolger et al., 2014)86 |

http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic; RRID:SCR_011848 |

| STAR (v. 2.7.9a) | (Dobin et al., 2013)87 |

http://code.google.com/p/rna-star/; RRID:SCR_004463 |

| featureCounts (v.2.0.0) | (Liao et al., 2014)88 |

http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/featureCounts/; RRID:SCR_012919 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Ignacio Melero (imelero@unav.es).

Materials availability

Mouse scIL-12 mRNA and mouse IL-18 mRNA generated in this study will be made available on request, but we may require a payment and/or a completed Materials Transfer Agreement if there is potential for commercial application. The mouse lines generated in this study are available upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

All mouse procedures were approved by the ethics committee for animal experimentation of the regional Government of Navarra under Spanish regulations (study 079/20). Mice were housed at the animal facility of the Center for Applied Medical Research (CIMA, Pamplona, Spain). Six week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Envigo (Barcelona, Spain). Pmel-1,35 OT-I and Batf3−/−gene-modified mice were bred in our facilities (CIMA, Pamplona, Spain). Batf3−/− mice were kindly provided to us by Dr. David Sancho (CNIC, Madrid, Spain).37 Littermates of the same age (7-10-week-old) were randomly assigned to experimental groups.

Tumor cell lines

MC38 cells were a kind gift from Dr. Karl E. Hellström (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) in September 1998. B16-OVA cells were provided by Dr. Lieping Chen (Yale University, New Haven, CT) in November 2001. B16F10 cells were purchased from the ATCC in June 2006. Cell lines were cultured in complete media containing RPMI1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) and 5x10-5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco). B16-OVA cultures were supplemented with 400 mg/mL geneticin (Gibco). B16OVAgp75transfectants were generated by transduction of B16OVA cells with an amphotropic retrovirus coding a mutated gp75 (gp75δ27) lacking the last 27 amino acids necessary for intracellular sorting of gp75 into melanosomes and exhibiting enhanced surface expression.89

All cell lines were grown in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37⁰C for at least 7 days before inoculation to mice. All cell lines were routinely tested every 8 weeks for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza).

Primary cells

All mouse primary lymphocytes were activated/expanded, as described in the method details section, in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37⁰C and cultured at a density of 1.5x106 cells/mL in complete media (RPMI1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100ug/mL streptomycin (Gibco) and 5x10-5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco)).

Method details

Vector constructs, mRNA in vitro transcription and mRNA transduction by electroporation

The mouse scIL-12 mRNA, the mouse IL-18 mRNA and the mouse DRIL18 mRNA encoding cDNA sequences were cloned by GeneScript Inc. in pUC57-Kan vector holding a T7 promotor upstream of the cDNAs and followed by 2 tandem repetitions of the 3′UTR sequence of the human β2-Globin cDNA and a 120 poly A tail. DRIL18-encoding cDNA sequence was recently published.26 The mRNA encoding sequences on the cloning vectors were confirmed by direct sequencing and linearized by HindIII enzyme (New England Biolabs) prior to RNA in vitro synthesis. T7mScript™ Standard mRNA Production System (Cellscript) was used to generate capped IVT RNA from the cloning vectors according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The IVT RNA was purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and the purified mRNA was eluted in RNase-free water at 1–2 mg/mL.

For mRNA electroporation, the stimulated and expanded T cells were washed and resuspended in OPTI-MEM (Gibco) at a final concentration of 100 × 106 cells/mL. Subsequently, the cells were mixed with 10 μg of mRNA IVT per 0.1 mL and electroporated in 2 mm cuvettes (BioRad) using the Gene pulser Mx System (BioRad). T cell viability was checked 30 min after electroporation by flow cytometry using the Zombi NIR Fixable viability kit (BD biosistems).

Mouse lymphocyte isolation, activation and expansion

Pmel-1 and OT-I T cells were obtained from the spleen of Pmel-1 and OT-I mice respectively.29 Pmel-1 splenocytes were activated 48 h with 100 ng/mL of hgp100 peptide (Genscript). For OT-I splenocyte activation, we performed 48h cultures with 1 ng/ml of OVA peptide (Invivogen). Polyclonal CD8+ T cells were isolated with the CD8+ T cell isolation kit (MiltenyiBiotec) by negative selection using manual columns and following the manufacturer’s instructions. CD8+ T cell purity after selection was routinely tested by flow cytometry. Polyclonal CD8+ T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb (2 μg/mL, clone 17A2, Biolegend) and supplemented with soluble anti-CD28 mAb (1 μg/mL, clone 37.51, Biolegend) for 48 h. For expansion, stimulated cells were incubated with 50 IU/mL of human IL-2 (Proleukin) for 48 h.

Retroviral transduction of mouse T cells

Retroviral generation was performed as previously reported.61 Briefly, isolated CD8 T cells from splenocytes were activated in 24-well plates (Cellstar) coated with anti-CD3 mAb (2 μg/mL, clone 17A2, Biolegend) and supplemented with soluble anti-CD28 mAb (1 μg/mL, clone 37.51, Biolegend) for 48 h in complete medium supplemented with human IL-2 (50U/ml) (Proleukin) at 106/mL density. After 48 h later, lymphocytes were resuspended in retrovirus supernatant containing protamine sulfate (10 μg/mL, SIGMA) and human IL-2 and were spin-inoculated at 2000 x g for 90 min at 32°C. This process was repeated again with additional fresh retrovirus supernatant the next day. Then, CAR T cells were cultured at 37°C until day +7, electroporated with the indicated mRNAs to perform experiments. Transduction efficiency was checked by flow cytometry measuring reporter protein (EGFP) expression.

Mouse TIL isolation, sorting and expansion

TIL isolation, sorting and expansion were performed as previously described.60 Briefly, 20-day established bilateral MC38 tumors were excised, minced and digested with 400 U/mL collagenase D and 50 μg/mL DNase-I (Roche). Donor mice had been treated with anti-CD137 (3H3) mAb on days +12 and +15 to enhance T cell infiltration of tumors. Living cells were enriched by Percoll 35% (Merck) gradient centrifugation and cultured overnight in mouse complete media supplemented with 25 ng/mL of recombinant murine IL-7 (Immunotools) and IL-15 (Immunotools). For sorting of CD8+ PD1+ and CD8+ PD1- TILs, cells were stained with 7AAD+ viability-staining solution (BioLegend), CD8-AF467 (Biolegend) and PD-1-FITC (Biolegend) mAbs and run in a FACSAria sorter (BD Biosciences). Sorted CD8+ TILs were activated and expanded in culture with irradiated allosensitized allogeneic lymphocytes (ASAL) and BALB/c-derived allogenic bone marrow-derived DCs. For ASAL generation, C57/BL6 CD45.1 splenocytes were irradiated (4000 Rads) and cocultured with BALB/c splenocytes at a 1:1 ratio for 7 days in complete mouse media supplemented with 100 IU/mL of human recombinant IL-2 (Proleukin). ASALs were enriched by Ficoll Paque™ PLUS (GE Healthcare) centrifugation and were irradiated (4000 Rads) prior to co-culturing with TILs and DCs. For DC generation, BALB/c bone marrow cell suspensions were differentiated during 6 days in mouse complete media supplemented with 20 ng/mL of recombinant murine GM-CSF (Peprotech) and matured overnight with 1 mg/mL of LPS (Invivogen). For sorted TIL activation and expansion, TILs, ASALs, and DCs were cocultured over 10 days at a 1:4:1 ratio in mouse complete media supplemented with 1500 IU/mL of IL-2 (Proleukin) and soluble anti-CD3 (17A2, BioLegend) and anti-CD137 (3H3) mAbs at 100 ng/mL.

In vivo tumor inoculation, adoptive T cell transfer and treatments

For antitumor efficacy experiments, the B16-OVA tumor cell line was injected subcutaneously (0.5 × 106 cells in the right flank and 0.15 × 106 cells in the left flank) in 50 μL saline into 6–10 week old C57BL/6 or Batf3−/− mice on day 0. The resulting right tumors received intratumoral injections. For rechallenge experiments of tumor free surviving mice, 0.5 × 106 B16-OVA cells were injected in upper lateral flanks, distant from the site of the originally rejected tumor, at least 90 days following tumor rejections. For TIL extraction experiments, 0.5x106 MC38 cells were subcutaneously injected bilaterally in 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice.

Adoptive T cell therapy (ACT) experiments were performed in tumor-bearing mice at the indicated time points by intratumoral (i.t.) or intravenous (i.v.) injection of 5 × 106 mRNA- or mock-electroporated Pmel-1 or OT-I, 106 TILs or 106 CAR T cells in 50μL of saline buffer. Vehicle-treated mice were injected intratumorally with 50 μL of saline buffer. For the experiment with “naked” mRNA, 5μg of each mRNA (IL-12 and DRIL18) were injected in 50μL of Ringer’s lactate buffer (Grifols).

In vivo neutralization and inhibition experiments

For IFN-ɣ neutralization, mice were i.p. given 200μg of anti-IFN-ɣ (XMG1.2, BioXcell) or the matched isotype rat IgG1 (BioXcell) one day prior to ACT (corresponding to days +7 and +10), and twice during the following week after the second dose of ACT, days +13 and +16 for maintenance.

For E-selectin blockade, mice were injected i.v. with 90 μg of InViVoMAb anti-mouse E-selectin (9A9, BioXcell) starting the day of ACT until day +10. On day +11, tumors were collected and stained to determine the migration of the Pmel-1 cells to the contralateral tumor.

For the O-glycosylation inhibition, mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 cells were cultured for 2h in the presence of i benzyl- α-GalNAc (2mM) (Sigma-Aldrich) before ACT.

For miR-155 inhibition experiments, Pmel-1 cells were co-electroporated with the corresponding mRNA and the miRCURY LNA miR-155 Inhibitor or negative control (1.5μM) (Qiagen) in the electroporation medium.

Adoptively transfer and endogenous T cell characterization

For lymphocyte characterization after ACT, B16-OVA tumors were collected 72h following one dose of mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 cells and the corresponding cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry.

For hexokinase-II expression analysis, B16-OVA bearing mice were treated with one dose of mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 cells on day+8. 24h later, tumors were collected and assessed individually by flow cytometry. Averages of intensity of fluorence were studied for correlation with other markers.

Flow cytometry

For surface flow cytometry analyses, lymphocytes, CAR or TILs were treated with FcR-Block (anti-CD16/32 clone 2.4G2; BD Biosciences), and then surface stained with the following fluorochrome-labeled antibodies purchased from BioLegend: anti-CD4-BV421 (GK1.5), anti-CD8-BV510, -PE-Cy7 or -AF647 (53–6.7), anti-PD1-FITC (29F.1A12), anti-CD25-APC (PC61), anti-CD137-BV421 (1AH2), anti-CD90.1-BV510 (OX-7), anti-CD90.2-BV605 (30-H12) or/and anti-CD43 activation associated glycoform-PE (1B11). For intracellular staining, cells were permeabilized after surface staining with ice-cold Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD) for 10 min following the manufacturer’s instructions and intracellularly stained with anti-IL12-p40-PE (C15.6), anti-IFN γ-AF647 or BV785 (XMG1.2), anti-hexokinase-II-AF647 and anti-GzmB-FITC (NGZB). For intranuclear staining, cells were permeabilized with True Nuclear Transcription Factor Buffer Set (BioLegend) for 40 min and stained with anti-Ki-67-AF700 (16A8), anti-TOX-PE (TCRX10) and active caspase-3-PE (C92-605).

For lectin staining, 48h-cultured Pmel-1 electroporated T cells were incubated 30 min at 4°C with plant lectins (Lectin kit I and II, Vector labs) and then co-labelled with anti-CD8 BV510 and anti-CD4 BV421.

The Zombi NIR Fixable viability kit (BioLegend) or 7AAD Viability Kit (BioLegend) were used as a live/dead marker. Flow cytometry was performed using CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter) cytometer.

Serum toxicity determination

Serum ALP (alkaline phosphatase), AST (aspartate aminotransferase), CRP (C-reactive protein), LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) and IFNɣ levels were determined in peripheral blood samples of tumor bearing mice 48h after mRNA-electroporated Pmel-1 treatment corresponding to day +10 in the B16-OVA model. ALP, AST, CRP and LDH levels were determined using the Cobas c311 analyzer (Roche) and IFNɣ levels were assessed by mouse IFNγ OptEIA set (BD).

In vitro cytotoxicity assays (xCELLigence)

In vitro real-time killing assays were performed by measuring electric impedance over time in an xCELLigence Real Time Cell Analysis Instrument (ACEA). 5x103 B16OVA cells were seeded onto a 16-well plate (ACEA) and cultured for 4 h prior to the assay thereby allowing tumor cell adhesion. After the 4h-culture, 1x103 Pmel-1 T cells that had received the indicated electroporation conditions with or without miRCURY miR-155 Inhibitor or a similarly synthetized irrelevant negative control (1.5 μM) (Qiagen) were added to the B16-OVA containing wells, in a 1:5 target-effector ratio. When indicated, for IFN-ɣ and IL-22 neutralization we added 2.5 μg/mL of anti-IFN-ɣ (XMG1.2, BioXcell) or anti-IL22 (R&D). Electric impedance was measured every 5 min for 96 h.

Adhesion assays

For the adhesion assays, 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4°C with E-selectin-Fc diluted to 2 μg/mL in 100μL PBS per well. Pmel-1 activated CD8 T cells transfected 48 h prior to the experiment with either scIL-12 mRNA alone or mixed with DRIL18 electroporated cells were pre-stained with either CMRA Orange or CMFDA fluorescent probes and then mixed at 0.5x106/mL in an eppendorf tube just before the experiment. Adhesion was measured following a 15-min incubation at 37⁰C and 5% CO2. After this incubation period, plates were washed with PBS 5 times by inverting the plate. Then, we added 100 μL of 10% PFA to fixate the cells. After 30 min of incubation at 37⁰C, plates were washed twice with PBS and kept at 4⁰C. Differential adhesion was analyzed in confocal microscopy images. Microscopy was performed in an LSM 880 inverted microscope (Zeiss) using a 488 Argon Laser and a 561 nm laser lines and a 10x objective (Plan Neofluar 0.3 N/A). Quantification was carried out by counting differentially colored cells using IMARIS 9 software (Bitplane).

Flow adhesion assays

For the study of adhesion and arrest under flow conditions, IBIDI mSLIDE I (0.2 mm channel height) sticky slides were attached to glass cover glasses. E-selectin-Fc at 2 μg/mL in PBS was used to coat the glass surface for 16 h at RT. In other experiments the chambers were coated with collagen type 1 (1 mg/ml) and then 8x105 endothelial MS1 cells were seeded. Twenty-four h later the endothelial cells were treated with 20 ng/mL TNF-α for an additional 16 h. Pmel-1 activated CD8 T cells mRNA-transduced 48 h earlier with either scIL-12 mRNA alone or in combination with DRIL18 electroporated-cells were pre-stained respectively with CMRA orange and CMFDA green fluorescent probes and then mixed at a density of 0.5x106 cells/ml in DMEM containing HEPES 1 mM. Tubing was connected to the flow chambers establishing a closed circuit using a peristaltic pump (Senchen MC series). The shear flow was set up at 1.4 dyn/cm2 following the manufacturer’s instructions. Live imaging was performed in an LSM880 confocal microscope equipped with a heated staged and T cell media was also kept at 37°C. Single plane images focusing on the endothelial monolayer (or glass surface) were obtained every 500 ms under simultaneous excitation with 488 nm and 543 nm lasers using a 25x LD water immersion objective (N/A: 0.8). Videos were analyzed with IMARIS 9 (Bitplane) using automatic tracking algorithms.

Mitochondria staining

For mitochondria staining, cells were incubated with a mitochondrial transmembrane potential indicator (TMRM; 125 ng/mL, Sigma) and MitoTracker green (5 mmol/L; both from Thermo Fisher Scientific) in complete culture media for 20 min at 37°C and assessed in confocal microscopy images. Microscopy was performed in an LSM 880 inverted microscope (Zeiss) using a 488 Argon Laser and a 543 nm solid state laser and a 63x oil immersion objective (N/A 1.4).

Cytokine measurement in T-cell culture supernatants

For cytokine determination, we used 24 or 48 h-supernatants from Pmel-1 mRNA-electroporated T cells either with scIL-12 or DRIL18 mRNAs and then mixed 1:1 in comparison with single mRNA-transfected T cells. A mouse ProcartaPlex Mix&Match 13-plex (Thermofisher) was used to measure mouse IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-15, IFN-α, IFN-β, CCL3, IL-10, IL-6 and IL-12 cytokines. Additionally, we used mouse IFNγ OptEIA set (BD), mouse IL-12 (p70) ELISA set and ELISA Mouse Duoset IL-22 for single measurements of IFN-γ, IL-12 and IL-22.

Seahorse and glucose uptake assays

For Seahorse assays, we electroporated Pmel-1 cells with scIL-12 or DRIL18 mRNAs and, when indicated, mixed prior to the experiment. Cells were resuspended in the assay medium (Seahorse XF DMEM medium pH 7.4 (Agilent) without phenol red supplemented with 15mM de glucose, 1 mM pyruvate and 2mM glutamine) and added to pre-coated XFs Microplates (Agilent) with Cell-Tak. Then, plates were centrifuged at 300 g for 1 min with no brake and placed in a non-CO2 incubator at 37°C to equilibrate the temperature for 30 min. Microplates were placed into the Agilent Seahorse XF Analyzer (Agilent) to assess glucose metabolism and respiratory capacity by adding to the culture 1 μM oligomycin (Sigma); 2 μM FCCP (Sigma), 1μM Antimycin A/Rotenone (Sigma) and 75 mM 2-DG.