1 |. INTRODUCTION

Promoting healing of damaged tissues via organs with living cells and growth factors has progressively raised a great deal of interest within the scientific community.1–3 At the same time, the perspective of receiving advanced and minimally invasive regenerative treatment for severe or chronic conditions has also been promising for patients.4,5 Tissue engineering is the interdisciplinary combination of the principles of engineering to life sciences for the development or biological substitutes that can restore, maintain, or improve lost or damaged biological tissues and organs.6,7 The progressive scientific advances in biomaterials, cell therapy, and growth factors in recent decades have brought new therapeutic options for injured tissues/organs with limited healing potential.8–11 Nowadays, several tissue-engineered organs—including, but not limited to, blood vessels, skin grafts, tracheas, and esophagus—have been successfully utilized in a clinical setting and may become the standard of care in the future, overcoming the disadvantages of transplantation.12–20

In the oral cavity, a large variety of soft- and/or hard-tissue deformities potentially impairing periodontal and peri-implant health, as well as a patient’s quality of life, are commonly observed.10,21–26 Pathologies, traumas, and congenital conditions can result in severe defects requiring challenging and “invasive” bone and/or soft-tissue reconstruction procedures.3,24,27–29 Tissue engineering strategies involve the enrichment of scaffolds with living cells or growth factors, aiming at mimicking the cascades of wound healing events and the clinical outcomes of conventional autogenous grafts, but in a minimally invasive manner.1,10 Indeed, the recent decades have witnessed an increased attention on patient perspective, quality of life, and satisfaction related to the treatment, at a point that patient-reported outcome measures have become as important as clinical outcomes, limiting the use of autogenous grafts.22,25,30–35 Several studies have shown that patient preference was seldom in line with the clinical—and professional—outcome, and more often towards the less invasive procedure.36–40 Tissue engineering strategies also have the potential of promoting an accelerated healing and recovery, together with periodontal regeneration, owing to the beneficial effect of these living cells and growth factors/biologic agents.41–45

1.1 |. Limitations of conventional techniques

Tissue engineering would probably not be an emerging field if the conventional techniques for periodontal and peri-implant reconstruction were flawless. The main drawback of conventional treatment with autogenous grafts is patient morbidity,3 which largely depends on the size of the defect, and therefore the amount of graft harvested. Intraoral autogenous bone harvesting is often insufficient to completely occupy the defect in presence of severe atrophies.3,24,26 Utilizing autogenous grafts also increases the surgical time, which can exacerbate postoperative swelling and pain. Owing to the second surgical site required for autogenous tissue harvesting, the risk for intra- and postoperative complications is also higher. Major complications described following intraoral bone harvesting include temporary and permanent neurosensory disturbances, altered sensation, loss of tooth vitality, soft-tissue dehiscence, and infection have been described as common complications after autogenous bone harvesting from the mandibular ramus and the chin.46,47 Similarly, bone harvesting from the iliac crest can result in minor complications, such as superficial infections or hematomas, or more serious adverse events, including vascular injuries, neurological injuries, iliac spine fracture, deep infection, and deep hematoma formation requiring surgical intervention, among others.48,49

On the other hand, complications of autogenous soft tissue grafting—which is still the gold standard and most commonly performed procedure around natural teeth and dental implants22,50—mainly include injuries to the greater palatine artery, prolonged intra- and postoperative bleeding, patient morbidity, change of feeding habits, impairment of the patient’s quality of life within the first 1–2 weeks, and sensory disfunction.51–55

Therefore, the rationale of tissue engineering strategies in periodontal and peri-implant reconstruction is to search for a viable and minimally invasive alternative to conventional autogenous graft-based procedures that can enhance the healing potential of the defect, promoting regeneration of the lost tissues. Tissue engineering strategies may also have the potential of enhance the outcomes of current biomaterials, which are often characterized by early resorption or persistence, limited capacity to reconstruct severe defects, and which usually provide inferior outcomes compared with the gold standard autogenous grafts.56,57

2 |. PRINCIPLES OF TISSUE ENGINEERING IN PERIODONTAL AND PERI-IMPLANT RECONSTRUCTION

Tissue engineering approaches involve the combination of cells, signaling molecules, and scaffolds together with a vascular supply from the surgical site (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The critical components of tissue engineering

2.1 |. Cells

Cell therapy aims to enhance the regenerative potential of conventional approaches by bringing living cells to the surgical area that can orchestrate the release of several growth factors crucial for the healing process.3,24,58 Cell therapy can overcome the limitations of autogenous graft substitutes by providing a source of living autogenous cells in the defect for regeneration3,24 (Figure 2). Somatic cells are characterized by lack of self-renewal capability and limited potency, as opposed to stem cells that can perpetuate through mitotic cell division and which can differentiate into several cell populations.10,24 Fibroblasts and keratinocytes are the somatic cells that have been employed for oral soft-tissue reconstruction.24,38,50,59–61 These cells are usually obtained from neonatal foreskin or from the actual patients with a punch biopsy. Autogenous cultured and expanded fibroblasts have also been used for root coverage procedures, widening of attached gingiva, and papilla augmentation.60,62–65

FIGURE 2.

The cell-based therapy workflow, from initiation at harvesting to its clinical implementation

Stem cells retain the ability to renew themselves through cell division and differentiate into a variety of specialized cell types.24 The bone marrow stroma contains hematopoietic stem cells, which can differentiate into blood cells of all lineages, and mesenchymal stem cells, which can give rise to osteoblasts, chondroblasts, adipocytes, myocytes, and fibroblasts, depending on the cell-to-cell interaction at the defect site.10,24 Historically, mesenchymal stem cells were first isolated and expanded from bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest,66,67 but other sites can also be used to obtain them, including gingival tissue and periodontal ligament.24,68–75 A common method for increasing the concentration of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow aspirate is based on density gradient separation utilizing centrifuge-based systems.2,76–78 This approach is simple, fast, and cost-effective,79–81 and it is performed when fresh uncultured (“minimally manipulated”) stem cells are applied right after the bone marrow aspirate, without undergoing cell expansion.68,79,81–83 Nevertheless, this method does not distinguish between peripheral blood cells and stem cells, and therefore it may only increase the concentration of peripheral blood cells rather than stem cells.2 On the other hand, cell cultivation and expansion have allowed billions of stem cells to be obtained from just 1 mL of bone marrow aspirate.83,84 This process has been shown to be an effective method to highly characterize and enrich (up to 100-fold) specific cell populations67 (Figure 3). However, the main drawback of mesenchymal stem cells expansion is the waiting period (up to 2 weeks) between the harvesting from the bone marrow aspirate and their clinical application, together with the risk of contamination and the costs associated with this procedure.79,83,85 It has been advocated that mesenchymal stem cells can also be obtained from allograft tissues.86–89 Advancements in processing techniques have allowed mesenchymal stem cells to be obtained from allograft tissue, by selectively depleting immunogenetic cells while retaining native mesenchymal stem cells and osteoprogenitors.86,87,89

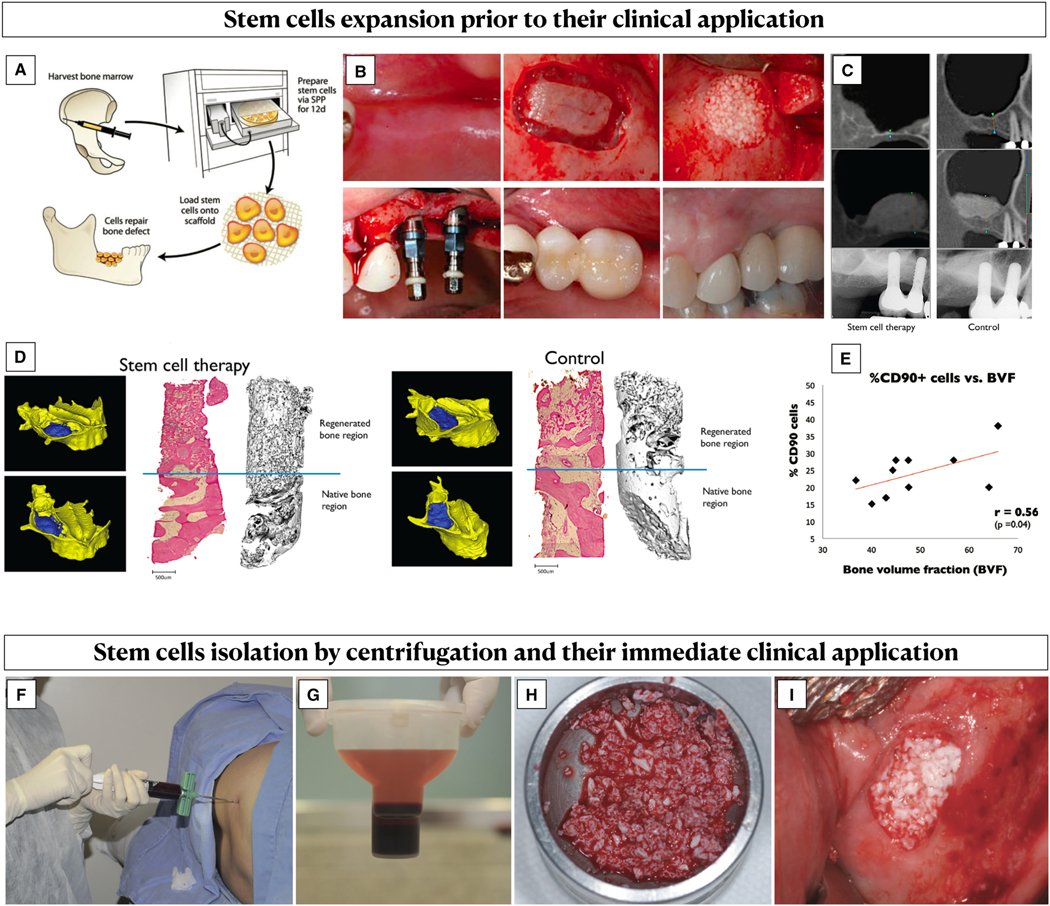

FIGURE 3.

Expanded vs “minimally manipulated” stem cells. A-E, Stem cell expansion involved their harvesting from a donor source, which is usually the iliac crest bone marrow, and their cultivation and expansion using bioreactors. A, After their expansion, the cells are loaded into a scaffold and clinically apply on the target defect (reproduced with permission from SAGE journals26). B, Example of clinical application of bone marrow–derived expanded stem cells into a bone scaffold for sinus floor augmentation. C, Radiographic imaging showing bone gain following sinus floor elevation with and without stem cell therapy. D, Three-dimensional reconstruction from the cone-beam computed tomography, histological and microcomputed tomography analysis of bone biopsies in two samples representing the two groups. A significantly higher bone volume fraction was found in sinus augmented with cell therapy compared with the control group. E, A positive correlation between the degree of CD90+ stem cell enrichment and bone volume fraction was observed (Reproduced with permission from CCSE67). F-I, Clinical application of “minimally manipulated” stem cells from the iliac crest bone marrow. F, Bone marrow aspiration. G, Anticoagulant added to the syringe containing bone marrow, which was then placed in a centrifuge system for 14 minutes. Two phases were obtained, with the plasma that was removed, and the cell concentrate resuspended. H, Enrichment of a xenograft scaffold with the bone marrow concentrate. I, Clinical application for sinus floor augmentation (reproduced with permission from Hindawi Publishing Corporation79)

2.2 |. Signaling molecules

Growth factors are a collective group of highly active signaling molecules able to promote cell chemotaxis, proliferation, and differentiation.41,84,90 These biological mediators have the potential to induce intracellular signaling pathways, activating genes that change the activity and the phenotype of the targeted cell.90,91 Advancements in cellular and molecular biology have allowed for a better understanding of the role of the different growth factors and cytokines on the wound healing dynamics (Figure 4), which is the basis of tissue engineering strategies utilizing recombinant human growth factors or biologic agents.90,92,93 The goal of growth factor therapy is regenerating damaged tissue by mimicking the processes occurring during embryonic and postnatal development.90,94 Although several signal molecules play a role during wound healing, it may be assumed that using a single recombinant growth factor can induce molecular and biochemical cascades that will eventually promote regeneration.90,93,95 Recombinant human platelet–derived growth factor-BB, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2, -4, -7, and -12, recombinant human growth and differentiation factor, and recombinant human fibroblast–growth factor are among the most investigated growth factors for oral regeneration. Enamel matrix derivative is an alternative signal molecule that has been largely used in periodontal regeneration and in several other scenarios as a wound healing enhancer.41,96–101

FIGURE 4.

Cell populations involved in the different phases of wound healing. Four different and partially overlapping wound healing phases have been identified: coagulation, inflammatory, proliferation, and maturation/resolution. Following blood clot formation, degranulating platelets release platelet-derived growth factor that is responsible for stimulating chemotaxis and/or mitogenicity of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts, which play a key role on the initiation of the inflammatory response. Macrophages are the main actors of the subsequent wound healing phases, contributing to the wound debridement and secreting several growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor beta, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor. The phase of proliferation and maturation involves several cell populations, based on the injured tissue. At later stages, platelet-derived growth factor stimulates mesenchymal progenitor cell migration and, together with transforming growth factor beta, promotes fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts, which is a crucial step for wound healing contraction and closure. The apoptosis of endothelial cells and fibroblasts is orchestrated by transforming growth factor beta, whereas vascular endothelial growth factor promotes angiogenesis and anti-apoptotic effects on other cells

2.3 |. Scaffolds

Scaffolds utilized for tissue engineering strategies can be classified based on their origin (natural vs organic), source (autogenous, allogeneic, xenogeneic, or alloplastic) or main therapeutic goal (promoting bone and/or periodontal regeneration or soft-tissue reconstruction).

2.3.1 |. Scaffolds for bone and periodontal reconstruction

Allogeneic, xenogeneic, and alloplastic bone substitutes are the most widely adopted scaffolds for oral bone regeneration.24,26,56 Though the primary function of bone grafts is promoting new bone regeneration within the bony defects through osteogenesis and osteoinduction, they also play a significant role also as scaffolds by preventing the collapse of the flap/membrane into the defect, therefore maintaining the biologic space necessary for the regeneration (osteoconduction).102 Osteogenesis involves the osteodifferentiation and new bone formation by donor cells from the host or graft, and it is a prerogative of autogenous bone graft only. The osteoinduction capacity of allograft and xenograft largely depends on the processing methods for eliminating antigenic components and preventing disease transmission. Owing to their osteoinductive and osteoconductive properties, allogeneic, xenogeneic, and alloplastic bone grafts have often been combined with growth factors or living cells for enhancing new bone formation.8,83,90

Nevertheless, limitations of these naturally derived scaffolds include the inability to tailor their degradation time, poor processability into porous structure, and inability to maintain the desired volume under mechanical stimuli.24,103 In order to overcome these drawbacks, several natural and synthetic polymers have been evaluated as a scaffold for tissue engineering strategies, including cellulose, chitosan, collagen, hyaluronic acid, polylactic acid, polylacticpolycaprolactone, and so on.24,103 At the same time, advances in technologies have oriented researchers towards the development of customized, image-based, three-dimensional scaffolds.56,104 Additive manufacturing allows production of multilayer scaffolds, with a different array of materials, and with a specific surface topography that can facilitate cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation.56,104 The concept of a fiber-guiding scaffold has been extensively evaluated for periodontal regeneration, with the goal of promoting the growth of periodontal ligament cells and Sharpey fibers in the desired, oriented, direction104,105 (Figures 5 and 6). In 2015, Rasperini et al described the first clinical application of a three-dimensional printed bioresorbable scaffold for periodontal regeneration106 (Figure 6).

FIGURE 5.

Three-dimensional customized printed scaffolds with multi-tissue interfaces. A, Three-dimensional designed hybrid scaffold with perpendicularly oriented internal channel-structures within the periodontal ligament (PDL) portion and a bone-specific compartment (reproduced with permission from Elsevier265). B, Planification of a customized multicompartments scaffold from the microcomputed tomography scan (reproduced with permission from Sage Publications106)

FIGURE 6.

A, Baseline peri-apical X-ray. B, C, Clinical view of the tooth with periodontal infrabony defect. D, Flap elevation. E, Application of 24% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 2 minutes. F, Polycaprolactone scaffold. G, Scaffold soaked with recombinant human platelet–derived growth factor-BB (GEM21; Lynch Biologics, Franklin, TN, USA). H, Scaffold fixation to the alveolar bone. I, Flap closure. J, Healing after 2 weeks. K, One year post-op (reproduced with permission from Sage Publications106)

2.3.2 |. Scaffolds for soft-tissue reconstruction

Scaffolds for soft-tissue reconstructions are usually dermal or collagen matrices that act as “empty” structures promoting the migration and colonization of host cells from the adjacent sites.24,42,107

Human allogeneic acellular dermal matrix was one of the first extracellular matrices to be utilized for the treatment of chronic and burn cutaneous wounds, as well as in periodontal soft-tissue augmentation.107–110 Acellular dermal matrix mimics the extracellular matrix of human dermis, with preserved natural porosity, vessel channels, and basement membrane, which makes the scaffold suitable for epithelial cells and fibroblasts42,111 (Figure 7). After removal of the epidermis, the graft undergoes a decellularization process to make it immunologically inert. Interestingly, it has been shown that the method of decellularization and processing of the acellular dermal matrix has an impact on the characteristics of the matrix, with consequences also on cells migration and proliferation.42,112,113

FIGURE 7.

Human and porcine-derived acellular dermal matrices before and after rehydration. The drawing illustrates the structure of these matrices, with the presence of fibrillar collagen and collagen VI that provide stability to the scaffold and of elastin fibers that contribute to the elasticity of the matrix. Other components of these scaffolds include hyaluronan, proteoglycans, fibronectin, and vascular channels, which play a crucial role for the revascularization of the graft. BM: basement membrane; DM: dermal side of the acellular dermal matrix. The solvent-dehydrated matrix is Puros Dermis (Zimmer Dental, Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA), the freeze-dried matrix is AlloDerm (BioHorizons, Birmingham, AL, USA), and the porcine-derived matrix is NovoMatrix (BioHorizons, USA)

Overall, acellular dermal matrix is a popular matrix for tissue engineering strategies given its preserved extracellular properties, good durability, and reduced antigenicity.114,115 In the periodontal field, different types of acellular dermal matrices have been introduced and utilized in a clinical setting, mainly derived from human skin—and therefore not available in several countries—or obtained from a porcine source.34,109,110,116

The first generation of xenogeneic collagen matrix involves a non-cross-linked bilayered porcine-derived collagen matrix, mainly composed of collagen types I and III42,117,118 (Figure 8). Collagen type I is more resistant and may have angiogenic potential, whereas collagen type III contributes to the mechanical stability of the matrix but degrades quickly. This xenogeneic collagen matrix is composed of a thin (0.4 mm in thickness) occlusive compact layer (derived from peritoneum) that acts as a barrier while providing mechanical stability to the scaffold and by a thicker (1.3 mm) occlusive compact layer that promotes blood clot stabilization and promotion of cells ingrowth.42,117 A second generation of xenogeneic collagen matrix has been more recently introduced.119–123 This novel matrix undergoes a cross-linking process, aiming for a slow degradation process and volume stability of the matrix;42,124 it is characterized by a single porous layer, made of type I and type III collagen and a small amount of elastin fibers.42,120,124

FIGURE 8.

Different types of xenogeneic collagen matrix before and after hydration. The bilayered xenogeneic collagen matrix is Mucograft (Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland); CL: compact layer; SL: spongy layer. The porous cross-linked xenogeneic collagen matrix is Fibrogide (Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland). The multilayered cross-linked xenogeneic collagen matrix is Ossix Volumax (Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA)

Dermal and collagen matrices—as scaffolds alone—have often been compared in clinical trials with autogenous grafts, in an attempt to minimize patient morbidity.125–130 Nevertheless, an autogenous graft is still the optimal approach for periodontal and peri-implant reconstruction.35,131,132 Therefore, it is not surprising that these scaffolds have been enriched with signaling molecules, or living cells, to further enhance their properties and outcomes, with the hope to find a patient-oriented, minimally invasive, approach able to mimic the characteristics of autogenous grafts.50,60,65,133–135

2.4 |. Tissue engineering strategies

Tissue engineering strategies can be classified as follows:

cell-based tissue engineering strategies, involving living cells (eg, mesenchymal cells from bone marrow, somatic cells, cells from the periodontal ligament) seeded in a scaffold material (Figure 9); or

signaling molecule–based tissue engineering strategies, involving the application of scaffolds loaded/soaked with signaling molecules (Figures 10–12).

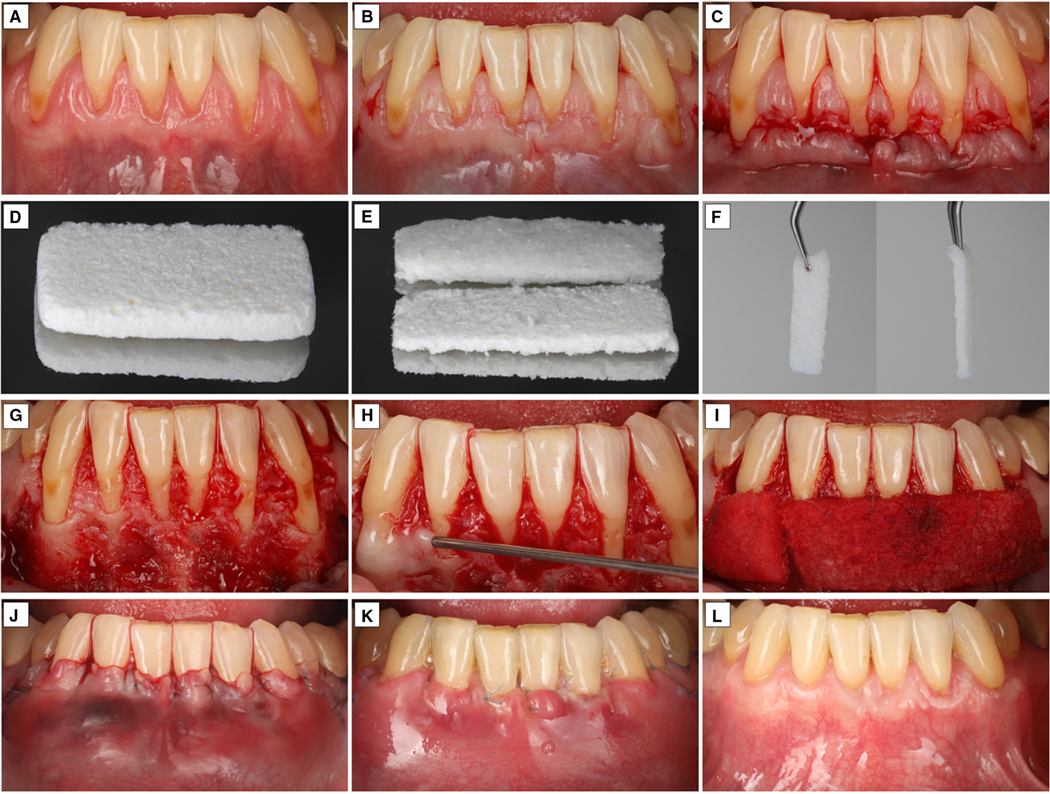

FIGURE 9.

Non–root coverage gingiva augmentation using a cell-based tissue engineering strategy. A living cellular construct, characterized by allogeneic keratinocytes and fibroblasts from newborn foreskin seeded into a collagen membrane (Apligraft; Organogenesis Inc., Canton, MA, USA), was used in this case that was part of a previously published clinical trial.38 A, Baseline. B, Flap elevation. C, Living cellular construct stabilized apically to the canine and premolars. D, An additional layer of the living cellular construct was applied over the graft. E, One week post-op. F, One month post-op. G, Six-month follow-up. H, Outcome after 13 years. Note that Lugol’s solution was used to discriminate the alveolar mucosa from the gingiva

FIGURE 10.

Periodontal regeneration using a signaling molecule–based tissue engineering strategy, involving the use of enamel matrix derivative (Straumann, Basel, Switzerland), in combination with a xenogeneic bone graft scaffold (Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland). A, Baseline peri-apical X-ray. B, Baseline clinical presentation. C-E, A minimally invasive flap preserving the integrity of the papilla was elevated. After the debridement of the infrabony defect, mechanical and chemical root planing was performed. F, Enamel matrix derivative extraorally combined with demineralized bovine bone matrix. G, H, Application of the tissue engineering strategy into the defect. Note that the suture was already prepared but not tightened. I, J, Flap closure. K, L, Clinical and radiographic outcomes at the 11-year follow-up

FIGURE 12.

Tissue engineering strategy for soft tissue reconstruction at a dental implant previously treated with a resective approach for peri-implantitis. (A) Clinical view of the dental implant at baseline. (B) Flap design. A trapezoidal coronally advanced flap was performed. (C) Split thickness flap elevation. Note that the healthy connective tissue that was adherent to the implant surface was left in place to facilitate the adaptation and nutrition of the soft tissue graft. (D) The level of the buccal bone – underneath the connective tissue – is identified with a periodontal probe. (E-F) Tissue engineering graft consisting of a xenogeneic collagen scaffold (Fibrogide, Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) loaded with rhPDGF-BB (GEM21, Lynch Biologics, Franklin, TN, USA). (G) Stabilization of the tissue engineering graft to the de-epitheliliazed anatomical papillae and to the periosteum. (H) Flap advancement and closure. (I) Ultrasonographic (US) scan of the midfacial aspect of the dental implant at baseline (BL). Note that the implant-supported crown is identified as “Cr”, “St” pinpoints the soft tissue component, which is also highlighted in blue and the implant fixture is shown as “Impl”. The scan on the left area of the panel is showing a frame of the blood flow cine loop when recorded as color velocity. (J) Clinical view of the implant at baseline, with the dotted white line showing the region of interest where the ultrasound scan was taken. (K) Clinical view of the implant at 1 year, with the dotted white line showing the region of interest where the ultrasound scan was obtained. (L) Ultrasonographic scan of the midfacial aspect of the dental implant 1 year after the soft tissue augmentation procedure. The ultrasonographic scan on the right area of the panel is showing a frame from the cine loop recording of the tissue perfusion around the dental implant in terms of color velocity. It is possible to appreciate a consistent gain in mucosal thickness compared to baseline and a reduction in the amount of color velocity, that may be interpreted as a resolution of the subclinical inflammation observed prior to the augmentation procedure

For both cell-based and signaling molecule–based tissue engineering strategies, the goal is mimicking the healing events promoted by autogenous grafts and cells of the hosts. Though it can be speculated that cell-based tissue engineering strategies can better simulate the healing cascade typical of autogenous grafts, there are no doubts that signaling molecule–tissue engineering strategies incorporating commercially available biologic agents are easier, less expensive, and more time-efficient procedures.

2.5 |. Aim of the search strategy

The goal of this review was the appraisal of the different tissue engineering strategies utilized for periodontal and peri-implant reconstruction, together with the evaluation of their safety, invasiveness, efficacy, and patient-reported outcomes.

3 |. SYSTEMATIC SEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

3.1 |. Protocol registration and reporting format

The protocol of this study was prepared and registered prior to it starting and allocated the identification number CRD42022309170 on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic reviews database.136 This review has been prepared following the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines137 and is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (Figure 13).

FIGURE 13.

The PRISMA flowchart illustrating the process of the studies selected

3.2 |. Focus questions

The focused questions of this review can be summarized as follows:

What are the tissue engineering strategies that have been performed for periodontal and peri-implant reconstruction and implant site development? Are tissue engineering strategies safe, minimally invasive, and predictable alternative options to conventional treatments?

3.3 |. Population, intervention, comparison, outcome, time questions

The following population, intervention, comparison, outcome, time framework was used to guide the inclusion and exclusion of studies for our focused questions138:

Population (P):

Patients undergoing surgical intervention for periodontal or peri-implant reconstruction or implant site development.

Intervention (I):

Surgical treatment for infrabony/furcation defects, root coverage procedures, non–root coverage gingival phenotype modification, alveolar ridge preservation, ridge augmentation, sinus floor augmentation, or peri-implant reconstruction utilizing tissue engineering strategies.

Comparison (C):

All possible comparisons among the interventions included were explored, including nonintervention or treatment with the use of a scaffold alone/placebo.

Outcome (O):

Clinical, radiographic, patient-reported outcome measures (including discomfort, painkillers intake, satisfaction, preference and esthetic assessment, invasiveness-related surgical outcomes), chair time, complications, and costs.

Time (T):

Any study duration or follow-up after the surgical intervention of at least 6 months for root coverage, gingival phenotype modification, periodontal regeneration, ridge augmentation, and sinus floor augmentation and 3 months for alveolar ridge preservation. Data at every follow-up time point were recorded.

3.4 |. Eligibility criteria, search strategy, and study selection

Only randomized controlled trials with a well-defined clinical protocol were considered for this study. A detailed computerized systematic search was conducted in the literature to identify eligible randomized controlled trials, followed by additional manual searching in relevant journals, past reviews,1,3,8,11,56,83,131–133,139–145 and cross-reference checks in the articles retrieved. The search strategies were entered and modeled for MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science (Appendix S1).

Two pre-calibrated review authors (LT, SB) performed the selection process of the randomized controlled trials, first by titles and abstracts and then followed by a full read through of the studies that remained for careful assessment and alignment with the set inclusion criteria.

3.5 |. Quality assessment and risk of bias

All the studies included were evaluated according to the Cochrane collaboration group146 independently and in duplicate by two examiners (LT, SB).

4 |. RESULTS FROM THE SYSTEMATIC SEARCH

The PRISMA flowchart is shown in Figure 13. Following the removal of duplicates, 1875 records were identified based on titles and abstracts. A full-text assessment was performed for 283 articles. Based on our predetermined inclusion criteria, 128 randomized controlled trials utilizing tissue engineering strategies were included in the qualitative assessment36,38,71,72,79,82,87,101,135,147–253,31–33,59–61,63–65,67–69 (Tables 1–14). Among them, 59 trials evaluated the efficacy of tissue engineering strategies for periodontal regeneration in infrabony and furcation defects71,72,148,49,158,159,162,165,167,177,178,193,198,223,224,227,229,240,242,245,247,248,251,151–155,169–172,180–182,184–187,201–206,212–216,220–223,234–238 (Tables 1 and 2), 16 randomized controlled trials focused on tissue engineering strategies for root coverage procedures43,44,60,61,64,65,135,157,163,168,222,228,238,241,249,250 (Tables 3 and 4), and four trials assessed the outcomes of tissue engineering strategies for non–root coverage gingival phenotype modification therapies36,38,59,63 (Tables 5 and 6). Forty-five randomized controlled trials had utilized tissue engineering strategies for implant site development, with 14 studies evaluating the outcomes of tissue engineering strategies for alveolar ridge preservation160,173,176,183,188,191,196,199,200,208,209,215,217,237 (Tables 7 and 8), eight trials on the outcomes of tissue engineering strategies for staged bone augmentation procedures164,207,216,230,243,31–33 (Tables 9 and 10), and 22 randomized controlled trial tissue engineering strategies for sinus floor augmentation79,82,87,101,156,161,166,174,175,179,192,194,195,197,225,226,239,244,246,67–69 (Tables 11 and 12). Tissue engineering strategies for peri-implant bone reconstruction were described in five randomized controlled trials147,150,189,190,231 (Tables 13 and 14).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the assessed clinical trials utilizing tissue engineering strategies for periodontal regeneration

| Cell-based tissue engineering | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Reference | Study design | Cell type | Origin | Cells culture medium | Scaffold | Control group |

| Abdal-Wahab et al148 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous fibroblasts | Gingiva or retromolar pad | α-Minimum essential medium with antibiotics | β-Tricalcium phosphate (covered with a collagen membrane) | Guided tissue regeneration (β-tricalcium phosphate + collagen membrane) |

| Apatzidou et al152 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous mesenchymal stem cells | Alveolar bone marrow | α-Minimum essential medium with antimicrobial/antifungal agents | Collagen scaffold enriched with autologous fibrin | Group 1: collagen scaffold enriched with autologous fibrin Group 2: flap alone |

| Chen et al158 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous mesenchymal stem cells | Periodontal ligament | α-Miαα-Minimum essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum with antibiotics | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Guided tissue regeneration (demineralized bovine bone matrix + collagen membrane) |

| Dhote et al170 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells | Umbilical cord | Serum-free medium specifically formulated for mesenchymal stem cells | β-Tricalcium phosphate (+ recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB) | Flap alone |

| Ferrarotti et al71 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous mesenchymal stem cells | Dental pulp | Cells not expanded | Collagen sponge | Collagen sponge |

| Sánchez et al72 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous mesenchymal stem cells | Periodontal ligament | Serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with antibiotics | Xenogeneic bone substitute containing hydroxyapati and collagen | Xenogeneic bone substitute containing hydroxyapatite and collagen |

| Shalini and Vandana236 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous mesenchymal stem cells | Periodontal ligament | Cells not expanded | Gelatin sponge | Flap alone |

| Yamamiya et al248 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous mesenchymal stem cells | Periosteum | Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics | Hydroxyapatite | Platelet-rich plasma + hydroxyapatite |

| Signaling molecule-based tissue engineering | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Reference | Study design | Biologic | Scaffold | Combination biologic and scaffold | Control group |

| Abu-Ta’a149 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft | Not reported | Enamel matrix derivative + demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft |

| Aoki et al151 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant fibroblast-human fibroblast-growth factor-2 | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Extraoral | Recombinant human fibroblast-growth factor-2 |

| Aslan et al153 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Not reported | Flap alone |

| Asprìello et al154 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft | Intraoral | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft |

| Bokan et al155 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Not reported | Group 1: enamel matrix derivative Group 2: flap alone |

| Cochran et al159 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human fibroblast-growth factor-2 | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate |

| Cortei lini and Tonetti162 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Not reported | Group 1: enamel matrix derivative Group 2: flap alone |

| De Leonardis and Paolantonio165 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate | Intraoral | Group 1: enamel matrix derivative Group 2: flap alone |

| Barcellos de Santana and Miller Mattos de Santana167 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human fibroblast-growth factor-2 | Hyaluronic acid | Extraoral | Flap alone |

| Devi and Dixit169 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor + recombinant human insulin growth factor-1 | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Not reported | Guided tissue regeneration (β-tricalcium phosphate + collagen membrane) |

| Recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Not reported | Guided tissue regeneration (β-tricalcium phosphate + collagen membrane) | ||

| Recombinant human insulin growth factor-1 | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Not reported | Guided tissue regeneration (β-tricalcium phosphate + collagen membrane) | ||

| Dori et al172 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative (+ platelet-rich plasma) | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Intraoral | Enamel matrix derivative + demineralized bovine bone matrix |

| Dori et al171 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative (+ platelet-rich plasma) | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Intraoral | Enamel matrix derivative + demineralized bovine bone matrix |

| Ghezzi et al177 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Not reported | Guided tissue regeneration (demineralized bovine bone matrix + collagen membrane) |

| Gurinsky et al178 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Hoffmann et al180 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Biphasic calcium phosphate | Intraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Hoidal et al181 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft | Intraoral | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft |

| Howell et al 1997182 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | 50μg/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + recombinant human insulin growth factor-1 | Gel vehicle | Extraoral | Flap alone |

| 150μg/mL recombinant human pi ate let-de rived growth factor-BB + recombinant human insulin growth factor-1 | Gel vehicle | Extraoral | Flap alone | ||

| Iorio-Siciliano et al184 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Extraoral | Guided tissue regeneration (demineralized bovine bone matrix + collagen membrane) |

| Jaiswal and Deo185,a | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft | Intraoral | Group 1: guided tissue regeneration (demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft + bioresorbable membrane containing polyglycolide and poly-L-lactide) |

| Group 2: flap alone | |||||

| Jayakumar et al186 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate |

| Jepsen et al187 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Biphasic calcium phosphate | Intraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Kavyamala et al193 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate |

| Kuru et al198 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Bioactive glass | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Lee et al202 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + equine-derived bone matrix |

| Lee et al201 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized porcine bone matrix | Extraoral | Demineralized porcine bone matrix |

| Lekovic et al203 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Intraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Lekovic et al204 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Intraoral | Autologous fibrinogen/fibronectin system + demineralized bovine bone matrix |

| Losada et al205 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Biphasic calcium phosphate | Intraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Maroo and Murthy206 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate |

| Meyle et al210 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Biphasic calcium phosphate | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Mishra et al 211 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Hyaluronic acid | Extraoral | Flap alone |

| Moreno Rodriguez and Ortiz Ruiz212 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Natural bovine bone substitute | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Nevins et al 213 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | 0.3 mg/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate |

| 1 mg/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate | ||

| Nevins et al214 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | 0.3 mg/mL recombinant human pi ate let-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate |

| 1 mg/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | β-Tricalcium phosphate | ||

| Ogihara and Wang219 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft | Extraoral | Orthodontic therapy + enamel matrix derivative + demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft |

| Ogihara and Tarnow218 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative Enamel matrix derivative | Freeze-dried bone allograft Demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft | Extraoral Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative Enamel matrix derivative |

| Peres et al220,a | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate |

| Pietruska et al221 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Biphasic calcium phosphate | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Queiroz et al223,a | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | Group 1: enamel matrix derivative Group 2: hydroxyapatite/β-tricaldum phosphate |

| Raslan et al224 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | Group 1: platelet-rich fibrin Group 2: flap alone |

| Ridgway et al227 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | 0.3mg/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB vs 1 mg/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | No control group |

| Saito et al229 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human fibroblast-growth factor-2 | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Extraoral mixing recombinant human fibroblast-growth factor-2 and demineralized bovine bone matrix | Recombinant human fibroblast-growth factor-2 |

| Scheyer et al232 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Extraoral | Demineralized bovine bone matrix |

| Schincaglia et al233 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB with single flap approach or double flap approach | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | No control group |

| Sculean et al234 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Bioactive glass | Extraoral | Bioactive glass |

| Sculean et al235 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Bioactive glass | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Stavropoulos et al240 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human growth and differentiation factor-5 | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | Flap alone |

| Thakare and Deo242 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | Hydroxyapatite + β-tricalcium phosphate |

| Velasquez-Plata et al245 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

| Windisch et al247 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human growth and differentiation factor-5 | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Extraoral | Flap alone |

| Zucchelli et al251 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Extraoral | Enamel matrix derivative |

Trials investigating the outcomes of furcation defects.

TABLE 14.

Safety, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical and histomorphometric results of the clinical trials utilizing tissue-engineering strategies for peri-implant bone augmentation

| Reference | Comparison | Safety | Complications | Patient-reported outcome measures | Clinical and histomorphometric outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amorfini et al150 | Tissue engineering strategy vs guided bone regeneration | Yes | 2 patients with early exposure of the membrane in the control group (no statistically significant difference, P > 0.05) | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: higher bone volume preservation*

Not reported |

| Santana et al231 | Immediate implant placement + tissue engineering strategy vs conventional implant placement | Yes | No | Not reported | Immediate implant placement + guided bone regeneration with tissue engineering strategy showed outcomes similar to conventional implant placement Not reported |

| Jung et al 2003189 | Tissue engineering strategy vs guided bone regeneration | Yes | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Not reported | Not statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: higher fraction of lamellar bone, higher surface of bone substitute particles in direct contact with the newly formed bone (statistically significantly different, P < 0.05)) |

| Jung et al 2009190 | Tissue engineering strategy vs guided bone regeneration | Yes | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) Not reported |

| Jung et al 2022147 | Tissue engineering strategy vs guided bone regeneration | Yes | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) Not reported |

P-value of 0.05.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the clinical and radiographic outcomes of tissue engineering strategies vs conventional approaches for the treatment of infrabony defects

| Comparison | Outcome favors tissue engineering strategies | Similar outcomes | Outcome favors conventional therapies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue engineering strategies vs bone graft scaffold alone | Aspriello et al 2011, Cochran et al 2016, Jayakumar et al 2011, Kavyamala et al 2019, Maroo and Murthy 2014, Nevins et al 2005, Nevins et al 2013, Thakare and Deo, Yamamiya et al 2008154,159,186,193,206,213,214,242,248 | Hoidal et al 2008, Lee et al 2020, Lekovic et al 2001, Sánchez et al 2020, Scheyer et al 2002, Sculean et al 200272,181,202,204,232,234 | None |

| Tissue engineering strategies vs guided tissue regeneration | AbdalAbdal-Wahab et al 2020, Devi and Dixit 2016148,169 | Chen et al 2016, Ghezzi et al 2016, lorio-Siciliano et al 2014158,177,184 | None |

| Tissue engineering strategies vs flap alone | Apatzidou et al 2021, Bokan et al 2006, De Leonardis and Paolantonio 2013, de Santana and de Santana 2015, Dhote et al 2015, Ferrarotti et al 2018, Howell et al 1997, Shalini and Vandana 201 871,152,155,165,167,170,182,236 | Aslan et al 2020, Cortellini and Tonetti 2011, Mishra et al 2013, Raslan et al 2021, Stavropoulos et al 2011153,162,211,224,240 | None |

| Tissue engineering strategies vs biologic agent alone | Aoki et al 2021, De Leonardis and Paolantonio 2013, Gurinsky et al 2004, Kuru et al 2006, Lekovic et al 2000, Ogihara and Tarnow 2014, Saito et al 2019, Velasquez-Plata, et al 2002, Zucchelli et al 200 3151,165,178,198,203,218,229,245,251 | Bokan et al 2006, Cortellini and Tonetti 2011, Hoffmann et al 2016, Jepsen et al 2008, Losada et al 2017, Meyle et al 2011, Moreno Rodriguez and Ortiz Ruiz, Pietruska et al 2012, Sculean et al 2005155,162,180,187,205,210,212,221,235 | None |

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of the clinical trials utilizing tissue-engineering strategies for root coverage procedures

| Cell-based tissue engineering | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Reference | Study design | Cell type | Origin | Cells culture medium | Scaffold | Control group |

| Jhaveri et al64 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous fibroblasts | Attached gingiva | α-Minimum essential medium containing fetal bovine serum and antibiotics | Acellular dermal matrix | Connective tissue graft |

| Koseglu et al60 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous fibroblasts | Palatal mucosa | DulDuDulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing fetal bovine serum and antibiotics | Collagen membrane | Collagen membrane alone |

| Milinkovic et al65 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Human autogenous fibroblasts | Palatal mucosa | Nutritional medium | Collagen membrane | Connective tissue graft |

| Wilson et al61 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Human allogeneic fibroblast | Newborn foreskin | Not reported | Bioabsorbable polyglactin mesh |

Connective tissue graft |

| Zanwar et al250 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells | Umbilical cord | Serum-free medium specifically formulated for mesenchymal stem cells | Polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid | Connective tissue graft |

| Zanwar et al249 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Human allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells | Umbilical cord | Serum-free medium specifically formulated for mesenchymal stem cells | Polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid | Polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid alone |

| Signaling molecule–based tissue engineering | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Reference | Study design | Biologic | Scaffold | ComCombination biologic and scaffold | Control group |

| Carney et al157 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Acellular dermal matrix | Acellular dermal matrix trimmed and then extraorally hydrated in 2 mL of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor for at least 3 min | Acellular dermal matrix alone |

| Dandu and Murthy163 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Xenogeneic collagen matrix | Xenogeneic collagen matrix trimmed and then extraorally saturated with 0.3mg/mL recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB for at least 10 min | Periosteal pedicle graft |

| Deshpande et al168 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | β-Tricalcium phosphate extraorally saturated with recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Flap alone, connective tissue graft |

| McGuire et al43 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | β-Tricalcium phosphate extraorally saturated with recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Connective tissue graft |

| McGuire et al44 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricalcium phosphate | β-Tricalcium phosphate extraorally saturated with recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Connective tissue graft |

| Pourabbas et al222 |

Split-mouth/parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Acellular dermal matrix | Intraorally combination of acellular dermal matrix with enamel matrix derivative | Acellular dermal matrix alone |

| Rocha Dos Santos et al228 and Sangiorgio et aI135 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Xenogeneic collagen matrix | IntrazIntraorally combination of xenogeneic collagen matrix with enamel matrix derivative | Flap alone, xenogeneic collagen matrix alone, enamel matrix derivative alone |

| Shin et al238 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Enamel matrix derivative | Acellular dermal matrix | Intraorally combination of acellular dermal matrix with enamel matrix derivative | Acellular dermal matrix alone |

| Tavelli et al241 | Parallel-arm randomized controlled trial | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | XenoXenogeneic cross-linked collagen matrix | Xenogeneic collagen matrix trimmed and then saturated with recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB for at least 15min | Xenogeneic collagen matrix alone |

TABLE 4.

Safety, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical results of the clinical trials utilizing tissue engineering strategies for root coverage procedures

| Reference | ComComparison | Safety; complications | Patient-reported outcome measures | CliniClinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carney et al157 | TissuTissue engineering strategy vs scaffold alone | Yes; not reported | Not reported | No stNo statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) |

| Dandu and Murthy163 | TissuTissue engineering strategy vs periosteal pedicle graft | Yes; no | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for pain | TissuTissue engineering strategy: higher mean root coverage, keratinized tissue width gain, and clinical attachment level gain* |

| Deshpande et al168 | TissuTissue engineering strategy vs connective tissue graft vs coronally advanced flap alone | Yes; no | Not reported | Mean root coverage not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05) between tissue engineering strategy and connective tissue graft Tissue engineering strategy: higher mean root coverage than coronally advanced flap alone* Greater keratinized tissue width gain in connective tissue graft group than tissue engineering strategy* |

| Jhaveri et al64 | Tissue engineering strategy vs connective tissue graft | Yes; not reported | Not reported | No stNo statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) |

| Koseglu et al60 | Tissue engineering strategy vs scaffold alone | Yes; no | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: greater mean root coverage No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for the other clinical parameters |

| McGuire et al43 | Tissue engineering strategy vs connective tissue graft | Yes; no | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for pain and satisfaction/esthetics. Tissue engineering strategy had higher patient preference in case of retreatment | Tissue engineering strategy: lower recession reduction, mean root coverage than connective tissue graft* Tissue engineering strategy: higher probing depth reduction than connective tissue graft* No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for the other clinical outcomes |

| McGuire et al44 | Tissue engineering strategy vs connective tissue graft | Yes; no | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for satisfaction/esthetics | Tissue engineering strategy: lower recession reduction, mean root coverage, keratinized tissue width gain, and clinical attachment level gain than connective tissue graft* EstheEsthetics outcomes not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05) |

| Milinkovic et al65 | Tissue engineering strategy vs connective tissue graft | Yes; not reported | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for mean root coverage, clinical attachment level, and professional esthetic outcomes (root coverage esthetic score) TissuTissue engineering strategy: less keratinized tissue width gain than connective tissue graft* |

| Pourabbas et al222 | Tissue engineering strategy vs scaffold alone | Yes; no | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) |

| Rocha Dos Santos et al228 and Sangiorgio et al135 | Tissue engineering strategy vs scaffold alone vs coronally advanced flap vs coronally advanced flap + enamel matrix derivative | Yes; not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in reduction of hypersensitivity and esthetic outcomes Tissue engineering strategy: better impact on oral health-related quality of life than coronally advanced flap,* but not statistically significantly different (P > 0.05) with scaffold alone and coronally advanced flap + enamel matrix derivative |

TissuTissue engineering strategy: higher mean root coverage than coronally advanced flap*

No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) mean non-root coverage soft tissue augmentation engineering strategy and scaffold alone No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in esthetic outcomes Tissue engineering strategy: higher keratinized tissue width gain than coronally advanced flap and coronally advanced flap + enamel matrix derivative* Not statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) keratinized tissue width gain between tissue engineering strategy and scaffold alone |

| Shin et al238 | Tissue engineering strategy vs scaffold alone | Yes; no | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for pain | Tissue engineering strategy: higher keratinized tissue width gain than scaffold alone*

No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for the other clinical outcomes |

| Tavelli et al241 | Tissue engineering strategy vs scaffold alone | Yes; no | Tissue engineering strategy: lower morbidity and time to recovery than scaffold alone No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for esthetic outcomes, satisfaction, and reduction of hypersensitivity |

Tissue engineering strategy: higher mean root coverage, complete root coverage, gingival thickness gain than scaffold alone and professional esthetic outcomes (root coverage esthetic score) than scaffold alone* |

| Wilson et al61 | Tissue engineering strategy vs connective tissue graft | Yes; not reported | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between tissue engineering strategy and connective tissue graft |

| Zanwar et al250 | Tissue engineering strategy vs connective tissue graft | Yes; no | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between tissue engineering strategy and connective tissue graft for mean root coverage and complete root coverage Tissue engineering strategy: lower keratinized tissue width gain* |

| Zanwar et al249 | Tissue engineering strategy vs scaffold alone | Yes; no | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: higher mean root coverage than scaffold alone*

No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for the other clinical outcomes |

Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

TABLE 5.

Characteristics of the clinical trials utilizing (cell-based) tissue engineering strategies for non-root coverage soft-tissue augmentation

| Reference | Study design | Cell type | Origin | Cells culture medium | Scaffold | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGuire and Nunn59 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Allogeneic fibroblast | Newborn foreskin | Not reported | Bioabsorbable Polyglactin mesh | Free gingival graft |

| McGuire et al36 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Allogeneic fibroblast and keratinocytes | Newborn foreskin | Not reported | Collagen membrane | Free gingival graft |

| McGuire et al38 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Allogeneic fibroblast and keratinocytes | Newborn foreskin | Agarose-rich nutrient medium | Collagen membrane | Free gingival graft |

| Mohammadi et al63 | Split-mouth randomized controlled trial | Autogenous fibroblasts | Attached gingiva | NutritNutritional medium containing AB human serum and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) | Collagen scaffold | Periosteal fenestration technique |

TABLE 6.

Safety, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical results of the clinical trials utilizing tissue engineering strategies for non-root coverage soft-tissue augmentation

| Reference | Comparison | Safety; complications | Patient-reported outcome measures | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGuire and Nunn59 | Free gingival graft | Yes; no | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Tissue engineering strategy: lower keratinized tissue width gain than free gingival graft* Tissue engineering strategy: better color match and tissue texture* |

| McGuire et al36 | Free gingival graft | Yes; no | Tissue engineering strategy: less pain and sensitivity of treatment than free gingival graft* Tissue engineering strategy: higher patient preference than free gingival graft* |

Tissue engineering strategy: lower keratinized tissue width gain than free gingival graft* Tissue engineering strategy: better color match and tissue texture* |

| McGuire et al38 | Free gingival graft | Yes; no | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for pain Tissue engineering strategy: higher patient preference and esthetic outcomes than free gingival graft* |

Tissue engineering strategy: lower keratinized tissue width gain than free gingival graft* Tissue engineering strategy: better color match and tissue texture* |

| Mohammadi et al63 | Periosteal fenestration technique | Yes; no | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: higher keratinized tissue width gain* |

Statistically significantly difference (P < 0.05).

TABLE 7.

Characteristics of the clinical trials utilizing tissue-engineering strategies for alveolar ridge preservation

| Cell-based tissue engineering | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Reference | Defect type | Cell type | Origin | Scaffold | Control group | Flap, complete closure |

| Kaigler et al191 | Not reported | Autogenous stem and progenitor cells | Bone marrow from iliac crest | Gelatin sponge (+ collagen membrane) | Gelatin sponge (+ collagen membrane) | Flaps raised, primary closure |

| Signaling molecule-based tissue engineering | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Reference | Defect type | Biologic | Scaffold | Membrane | Control group | Flap, complete closure |

| Coomes et al160 | Buccal bone dehiscence ≥50% | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Collagen sponge | No | Collagen sponge | FlaplFlapless, no primary closure |

| Fiorellini et al173 | Buccal bone dehiscence ≥50% | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Collagen sponge | No | Group 1: collagen sponge Group 2: spontaneous healing |

Flaps raised, primary closure |

| Geurs et al176 and Ntounis et al217 | Not reported | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Freeze-dried bone allograft/β-tricalcium phosphate | No | Group 1: collagen plug Group 2: freeze-dried bone allograft/β-tricalcium phosphate + collagen plug Group 3: freeze-dried bone allograft/β-tricalcium phosphate + platelet-rich plasma + collagen plug | FlaplFlapless, no primary closure |

| Huh et al183 | Teeth to be extracted with <50% alveolar vertical bone loss | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate | No | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate | Not reported, not reported |

| Jo et al188 | Teeth to be extracted with >50% alveolar bone height | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Collagen sponge | Bioabsorbable collagen membrane | No control group | FlapsFlaps raised, no primary closure |

| Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate | Bioabsorbable collagen membrane | No control group | |||

| Kim et al196 | Residual socket with <50% bone loss | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Demineralized bone matrix gel | Bioabsorbable collagen membrane | Demineralized bone matrix gel | FlapsFlaps raised, no primary closure |

| Lee and Jeong199 | Residual socket with <50% bone loss | Enamel matrix derivative | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | Bioabsorbable collagen membrane | Group 1: demineralized bovine bone matrix + bioabsorbable collagen membrane Group 2: spontaneous healing | FlaplFFlapless, no primary closure |

| Lee et al200 | Buccal bone dehiscence ≥50% | Enamel matrix derivative | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | Bioabsorbable collagen membrane | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen + bioabsorbable collagen membrane | Flapless, primary closure |

| McAllister et al208 | Not reported | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | No | No control group | Flaps raised, pediculated palatal connective tissue graft used for primary closure |

| Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | β-Tricβ-Tricalcium phosphate | No | No control group | |||

| Mercado et al209 | Buccal bone dehiscence ≤1 mm at the time of extraction, no palatal defect | Enamel matrix derivative | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | No | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | Flapless, free gingival graft used for primary closure |

| Nevins et al215 | Not reported | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | No | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | Flaps Flaps raised, primary closure |

| Enamel matrix derivative | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | No | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | |||

| Enamel matrix derivative | BoneBone ceramic | No | Xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | |||

| Shim et al237 | Not reported | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | HydroHydroxyapatite | No | Demineralized bovine bone matrix | FlapsFlaps raised, primary closure |

TABLE 8.

Safety, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical, radiographic, and histomorphometric results of the clinical trials utilizing tissue engineering strategies for alveolar ridge preservation

| Reference | Comparison | Safety; complications | Patient-reported outcome measures | Clinical, radiographic, and histomorphometric outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coomes et al160 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 + collagen sponge vs collagen sponge | Yes; mild erythema and localized swelling in the tissue engineering strategy group | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: higher buccal plate regeneration, clinical ridge width, and radiographic ridge width (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: less buccal bone dehiscence (statistically significant difference, P <0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: less implants needed additional bone augmentation (statistically significant difference, P <0.05) |

| Fiorellini et al173 | 0.75 or 1.5mg/mL recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 + collagen sponge vs collagen sponge vs spontaneous healing | Yes; more cases with edema and erythema in the tissue engineering strategy groups | Pain, no statistically significant different (P > 0.05) | Tissue engineering strategy: greater bone augmentation than control groups (statistically significant difference, P <0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: less sites requiring augmentation than control (statistically significant difference, P <0.05) No evidence of inflammation or residual collagen matrix from the absorbable sponge carrier |

| Geurs et al176 and Ntounis et al217 | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + freeze-dried bone allograft/β-tricalcium phosphate vs freeze-dried bone allograft/β-tricalcium phosphate vs freeze-dried bone allograft/β-tricalcium phosphate + platelet-rich plasma vs collagen plug | Yes, not reported | Not reported | Not reported Tissue engineering strategy showed the least amount of residual bone particles (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: more organic matrix than bone graft alone (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) |

| Huh et al183 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 + hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate vs hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate | Yes; not reported | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: less bone remodeling (height and width) than control (statistically significant difference, P <0.05) |

| Jo et l188 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 + collagen sponge + bioabsorbable collagen membrane vs recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 + hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate + bioabsorbable collagen membrane |

Yes; no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Pain, no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | No statistically significant difference (P >0.05) |

| Kaigler et al191 | Autogenous mesenchymal stem cells + gelatin sponge + bioabsorbable collagen membrane vs gelatin sponge + bioabsorbable collagen membrane | Yes; no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: greater radiographic bone fill at 6weeks (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: sixfold decrease in implant bony dehiscence (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) and less sites needed additional bone grafting at implant placement (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: higher vascularity. No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for bone volume fraction and bone mineral density |

| Kim et al196 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 + demineralized bone matrix gel + bioabsorbable collagen membrane vs demineralized bone matrix gel | Yes; no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in terms of radiographic outcomes |

| Lee and Jeong199 | enamel matrix derivative + demineralized bovine bone matrix vs demineralized bovine bone matrix + bioabsorbable collagen membrane vs spontaneous healing |

Yes; no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Pain, no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in tissue engineering strategy and bone graft groups |

| Lee et al200 | Enamel matrix derivative + xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen + bioabsorbable collagen membrane vs xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen + bioabsorbable collagen membrane | Yes; not reported | Pain, no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: lower duration of pain and swelling (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) |

No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in clinical and radiographic outcomes |

| McAllister et al208 | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen vs recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB +β-tricalcium phosphate | Not reported | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) |

| Mercado et al209 | Enamel matrix derivative + xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen vs xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | Yes; no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for clinical and radiographic outcomes Tissue engineering strategy: higher new bone formation and lower residual graft particles than control group (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) Control group showed higher soft tissue and marrow space than tissue engineering strategy (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) |

| Nevins et al215 | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen vs enamel matrix derivative + xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen vs enamel matrix derivative + bone ceramic vs xenogeneic bone mineral containing collagen | Yes; no | Not reported | Not reported Tissue engineering strategy: highest amount of new bone formation but no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) |

| Shim et al237 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 + hydroxyapatite vs demineralized bovine bone matrix |

Yes; no | Not reported | Tissue engineering strategy: superior outcomes in alveolar bone width changes (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: higher percentage of new bone formation (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) |

TABLE 9.

Characteristics of the clinical trials utilizing tissue engineering strategies for staged bone augmentation

| Cell-based tissue engineering | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Reference | Ridge Defect type | Cell type | Origin | Cells culture medium | Scaffold | Control group |

| Bajestan et al31 | Horizontal | Autogenous stem cells | Bone marrow from iliac crest | Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, and hydrocortisone | β-Tricalcium phosphate | Autogenous block graft from ramus or symphysis |

| Signaling molecule-based tissue engineering | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Reference | Ridge Defect | Biologic | Scaffold | Combination biologic and scaffold | Control group |

| De Freitas et al32 De Freitas et al164 | Horizontal | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Absorbable collagen sponge (+ titanium mesh) | Extraorally | Particulated autogenous bone (+ titanium mesh) |

| Marx et al207 | Horizontal and vertical | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Absorbable collagen sponge + freeze-dried bone allograft + platelet-rich plasma (+ titanium mesh) | Extraorally | Autogenous bone graft (+ titanium mesh) |

| Nevins et al216 | Horizontal and vertical | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Demineralized bovine bone matrix (+ bioabsorbable collagen membrane) | Extraorally | No control group |

| Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Equine bone matrix (+ bioabsorbable collagen membrane) | Extraorally | |||

| Santana and Santana230 | Horizontal | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB | Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate (+ nonresorbable membrane) | Extraorally | Autogenous bone block |

| Thoma et al 33 Thoma et al243 |

Horizontal | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 | Xenogeneic bone block (+ bioabsorbable collagen membrane) | Extraorally | Autogenous bone block + demineralized bovine bone matrix (+ bioabsorbable collagen membrane) |

TABLE 10.

Safety, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical and histomorphometric results of the clinical trials utilizing tissue engineering strategies for staged bone augmentation

| Reference | Comparison | Safety; complications | Patient-reported outcome measures | Clinical and histomorphometric outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajestan et al31 | Stem cells + β-tricalcium phosphate vs autogenous block graft | Yes; similar | Two patients of each group reported significant discomfort and other two from both groups reported interference with their daily activities* Similar satisfaction and willingness of retreatment* |

Tissue engineering strategy: lower bone width gain*

and less sites allowing for implant placement compared with control group* Not reported |

| De Freitas et al32 De Freitas et al164 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2/acellular collagen sponge vs autogenous bone graft | Yes; more swelling and erythema in the tissue engineering strategy group (no statistically significant difference, P > 0.05) | Temporary discomfort and pain from the donor site (control group) | Tissue engineering strategy: higher radiographic horizontal bone gain, not statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in the other clinical and radiographic parameters Tissue engineering strategy: bone marrow rich in capillaries, undifferentiated cells and bone lining cells (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05). Control group showed higher amount of non-vital bone particles trapped in lamellar vital bone (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) |

| Marx et al207 | Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2/acellular collagen sponge + freeze-dried bone allograft + platelet-rich plasma vs autogenous bone graft |

Yes; similar | Tissue engineering strategy: lower days of analgesics (P = 0.05), higher post-op edema at days 3, 8, and 15 (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) Tissue engineering strategy: less operative time (statistically significant difference, P < 0.05) |

No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in terms of presence of adequate bone for implant placement and percentage of implant osseointegration Tissue engineering strategy: higher vascular density blood vessels than autogenous graft (P = 0.05) No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) for the other outcomes |

| Nevins et al216 | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + demineralized bovine bone matrix + collagen membrane vs recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + EBM + collagen membrane | Yes; no | Not reported | Not reported New bone formation in close association with graft particles. No signs of inflammatory cell infiltration or foreign body reaction |

| Santana and Santana230 | Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB + hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate + nonresorbable membrane vs autogenous block graft | Yes; similar | Not reported | No statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) Not reported |