Summary

In the era of histopathology-based diagnosis, the discrimination between multiple lung cancers (MLCs) poses significant uncertainties and has thus become a clinical dilemma. However, recent significant advances and increased application of molecular technologies in clonal relatedness assessment have led to more precision in distinguishing between multiple primary lung cancers (MPLCs) and intrapulmonary metastasis (IPMs). This review summarizes recent advances in the molecular identification of MLCs and compares various methods based on somatic mutations, chromosome alterations, microRNAs, and tumor microenvironment markers. The paper also discusses current challenges at the forefront of genomics-based discrimination, including the selection of detection technology, application of next-generation sequencing, and intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH). In summary, this paper highlights an entrance into the primary stage of molecule-based diagnostics.

Keywords: Multiple primary lung cancers, Intrapulmonary metastasis, Differential diagnosis, Molecule, Genetics

Introduction

The popularity of low-dose CT (LDCT) serves as an effective weapon against lung cancer.1 However, the increasing incidence of multiple lung cancers (MLCs) presents a significant challenge, with the striking prevalence of multiple nodules being 19.7%–50.6% in screening trials.2,3 MLCs account for approximately 4.5–15.8 percent of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs).1,4,5 Fortunately, the presence of MLCs does not necessarily imply high-stage diseases. This patient population can be categorized as having either polyclonal multiple primary lung cancers (MPLCs) or monoclonal intrapulmonary metastasis (IPMs). Marked variations in prognosis have been observed between them, leading to disparate tumor staging and treatment strategies.6, 7, 8 In contrast to IPM patients, MPLC patients typically achieve a favorable outcome after curative surgery, without suffering from the toxicity and side effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy.8 These distinctions emphasize the importance of accurately identifying MLCs. Although histopathology has provided the foundation for identification, accumulating evidence suggests undiagnosed cases still exist, especially when there are similar pathological findings or a lack of experienced pathologists. Due to this inconclusiveness, molecular science is emerging as a means to provide definitive diagnoses.6,9,10 Theoretically, the pathogenesis of lung cancer is intricately linked to molecular variations that give rise to diverse tumors types and distinct hallmarks.11 Thus, the discrimination hinges on the molecular heterogeneity within MPLCs and the homogeneity within IPMs. The increasing availability of molecular detection in clinical settings will reliably assist the clonality assessment of MLCs (Fig. 1) and usher in the era of molecular-based diagnostics. However, current diagnostic criteria for MLCs do suffer from the paucity of robust molecular evidence. Although genetic features have been included in the ACCP guidelines, the specific detection techniques or contents remain undefined.12 The IASLC proposals consist primarily of recommendations with some uncertainties, limiting their usefulness.7 Moreover, the appropriate selection, application, and interpretation of molecular testing for MLCs are still unclear. Therefore, we attempt to provide a comprehensive review of cutting-edge research on the discrimination of MLCs, with a focus on molecule-based diagnostics, to address several critical questions: What is the current status of the differential diagnosis of MLCs? How do various existing methods achieve conclusive discrimination at different levels? What are the merits and limitations of various molecule-based methods? Which method is more effective between histopathological and molecular discrimination? What challenges should future research in this field seek to overcome?

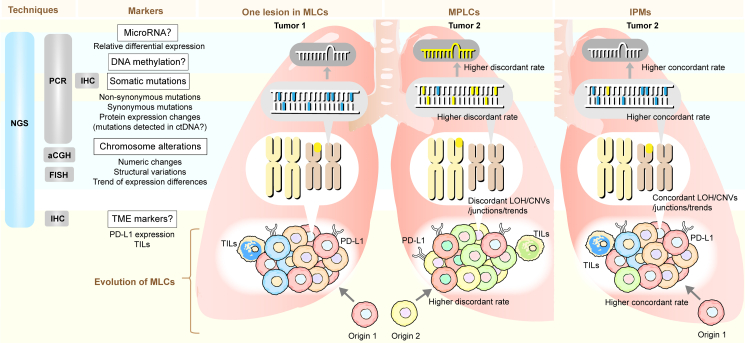

Fig. 1.

Overview of molecule-based methods for discriminating MLCs. This figure illustrates details of molecule-based discrimination. The rows are color-coded to represent different levels of molecular diagnostics, roughly in the order of macroscopic to microscopic from bottom to top. The columns are separated by white lines, and the Technique column refers to technologies applied to detect corresponding markers. Gray stands for traditional techniques, while NGS is highlighted in blue, representing more advanced methods that can cover almost all levels of markers. The Markers column displays molecular markers with their indicators for discrimination. A question mark is added at the end of the marker name when there are few relevant studies at present and the accuracy of this marker needs further determination. The remaining three columns show the specific discriminating points, namely the differences between MPLCs and IPMs. Tumor 1 represents one arbitrary tumor in MLCs, while Tumor 2 represents other lesions in MPLCs or IPMs except Tumor 1. Tumor cells of different colors correspond to different clones or subclones. MPLCs: multiple primary lung cancers. MLCs: multiple lung cancers. IPMs: intrapulmonary metastasis. NGS: next-generation sequencing. PCR: polymerase chain reaction. FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization. aCGH: array-based comparative genomic hybridization. IHC: immunohistochemistry. LOH: loss of heterozygosity. CNVs: copy number variations. TME: tumor microenvironment. TMB: tumor mutation burden. TILs: tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

Discriminating MLCs based on histopathology

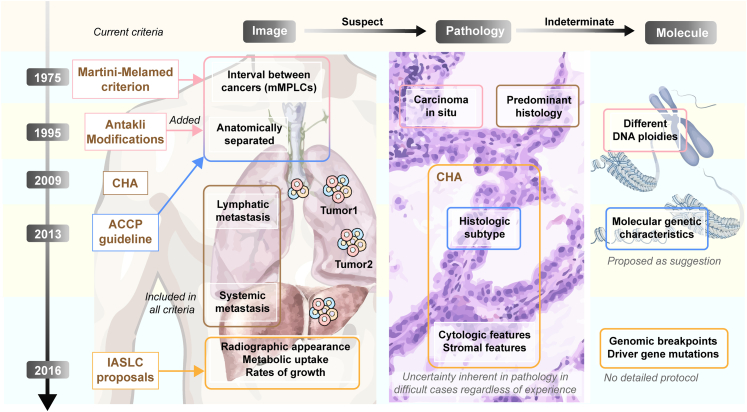

To date, histopathology remains the cornerstone of differentiating MLCs, with diagnostic criteria evolving since 1975.7,12,13 (Fig. 2). The proposal of comprehensive histopathology assessment (CHA) in 2009 made a qualitative leap in accuracy.13,14 The pathological team compares the proportions of different histological subtypes semi quantitatively, along with cytologic features and stromal characteristics.13 CHA is adequate in most clinical situations given its high consistency with molecular analysis and distinguishable survival curves.13,15 Several organizations have been recommended its use.7,12,16 Nonetheless, even experienced pathologists do suffer from the inherent uncertainty of histopathology when handling dilemmas such as the histologic dissimilarity in IPMs and morphologic similarity in MPLCs.14,17 A meta-analysis of twenty studies showed that the pooled sensitivity and specificity of CHA were approximately 0.76 and 0.74, respectively.9 In terms of lung squamous cell carcinomas (SqCCs), their more homogeneous architectures impede morphology-based discrimination. However, SqCCs usually harbor a higher tumor mutation burden (TMB) and distinct mutation spectrum compared with lung ADCs, indicating the feasibility of molecule-based discrimination.18,19 In summary, the insufficiency of histopathology is inevitable in complex situations. With the growing popularity of sequencing, discriminating methods based on the intrinsic characteristics of tumors are becoming more accurate and are gradually gaining prominence.

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic criteria of MLCs. This figure illustrates the key points of existing criteria from three dimensions (image, pathology, and molecule). Each row with different colors represents a diagnostic criterion, arranged in chronological order from top to bottom. The proposed diagnostic points for each criterion are indicated by rounded squares of different colors. Inadequacies of the current criteria are highlighted in gray text with italicized formatting. CHA: comprehensive histopathology assessment. MPLCs: multiple primary lung cancers.

Genomics-based methods for discriminating MLCs

Somatic mutations

Sequencing-based

Molecule-based methods mainly discriminate MLCs based on the heterogeneous profiles within MPLCs against relative homogeneity of IPMs and have been explored since the late 20th century (Table 1). These methods began with sequencing few somatic mutations, such as TP53,20,21,25 EGFR,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 and KRAS,23,24,26 which are representative driver events with high frequencies in NSCLC. Thus, they have been adopted to discriminate MLCs in a single or combined assay. However, despite improving the discriminating accuracy, these detections have obvious limitations, especially the high proportions of undetermined cases due to the narrow sequencing range. As more mutations are proven valuable, the combined analysis of more genes demonstrates higher accuracy than analyzing only one or two mutations.21,28,34,55 In the era of targeted therapy, there is much more to consider when dealing with MLCs.56 Inconsistencies of driver mutations could hinder the effectiveness of a single targeted drug, calling for testing for all tumors. Detecting a small number of hot spots cannot adequately elucidate actionable mutations. However, when testing more genes of multiple lesions, traditional techniques such as Sanger sequencing are usually time-consuming and labor-intensive. Fortunately, wider detection coverage plus satisfactory efficiency is feasible now with next-generation sequencing (NGS), facilitating further optimization.57 NGS-based diagnostics of MLCs are reputed for a lower inconclusive rate and better discrimination for prognosis (detailed in later section and Table 2 about the comparison and integrative application of NGS and histopathology).

Table 1.

Molecule-based methods for discriminating MLCs.

| Molecular levels | Techniques | Relevant studies | Performances |

Advantages | Disadvantages | Dilemmas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inconclusive cases | Diagnoses different from clinicopathology | |||||||

| Somatic mutations | 1 to 3 gene PCR | Van Rens [2002]20 Chang [2007]21 Chung [2009]22 Girard [2010]23 Takamochi [2012]24 Wu [2014]25 Sun [2018]26 Jia [2018]27 |

26% (8/31) 14% (8/58) 25% (6/24) 0% 17% (6/36) 23% (22/97) 30% (6/20 pairs) 7% (4/55) |

13% (3/23) 42% (21/50) 0% 14% (1/7) 30% (9/30) 67% (50/75) 57% (8/14 pairs) 8% (4/51) |

Proven accuracy of discrimination; Simple operation; High cost-performance ratio. | Low throughput; Limited sequencing range; Relatively high inconclusive rate; Cannot measure emerging biomarkers such as TMB and MSI | One high-frequency mutation could occur in two independent tumors. Empirical interpretation of sequencing results is relatively unreliable. Customized panels for MLCs sequencing are controversial. Intratumor heterogeneity confuse the discrimination. | |

| 2 to 4 gene PCR + 1 to 3 gene FISH | Schneider [2016]28 Asmar [2017]29 |

43% (26/60) 16% (11/69) |

18% (6/34) 31% (18/58) |

|||||

| 9 or 10 gene PCR | Zhu [2021]30 Xu [2022]31 |

38% (8/21) 14% (7/50) |

23% (3/13) 23% (10/43) |

|||||

| NGS | See Table 2 | Proven accuracy of discrimination; High throughput; Wide sequencing range; Low inconclusive rate; Measure emerging biomarkers simultaneously | Relatively high cost; Complicated operation | |||||

| IHC | p53 p53, p16, p27, c-erbB2 p53 |

Hiroshima [1998]32 Ono [2009]33 Roepman [2018]34 |

63% (12/19) 0% 45% (24/53 pairs) |

Discordant with sequencing: 20% (1/5) 19% (13/70) 31% (9/29) |

Low cost; Simple interpretation; Detection of immune markers; Assist pathological grading | Relatively high inconclusive rate; Accuracy to be investigated. | Discordance with detected mutations. The expression level is influenced by many factors. | |

| Chromosome alterations | PCR for LOH at 6–15 loci of polymorphic microsatellite markers | Shimizu [2000]35 Huang [2001]36 Dacic [2005]37 Wang [2009]38 Warth [2012]39 Shen [2013]40 Shen [2015]41 |

29% (4/14) 11% (1/9) 10% (2/20) 13% (4/30) 3% (2/78) 0% 0% |

40% (4/10) 63% (5/8) NA NA 29% (22/76) 25% (2/8) 9% (1/11) |

Acceptable accuracy of discrimination; Simple operation. | Low throughput; Limited detection range; | Hard to interpret when different and same LOHs occur at the same time. CNVs and mutation analysis are contradictory in some cases. | |

| aCGH for CNVs | Girard [2009]42 Arai [2012]43 Liu [2016]44 Sun [2018]26 Vincenten [2019]45 |

Noise: 8% (2/24 pairs); Equivocal calculation: 18% (4/22 pairs) 0% 33% (2/6) 0% 17% (7/41 pairs) |

22% (4/18 pairs) 17% (2/12) 25% (1/4) 35% (7/20 pairs) 38% (13/34 pairs) |

Acceptable accuracy of discrimination; Wide detection range. | Low throughput | |||

| WES for CNVs | Zhou [2022]46 | 63% (12/19) | NA | Acceptable accuracy of discrimination; High throughput; Wide detection range. | ||||

| Mate-pair NGS for rearrangements | Murphy [2014]47 Murphy [2019]48 |

0% 0% |

27% (3/11) 24% (9/37) |

Complex bioinformatic analysis | ||||

| MicroRNA | qRT-PCR for 5 miRNAs | Zhou [2016]49 | 0% | 25% (6/24) | Simple operation; Help reveal the post-transcriptional regulation in MLCs | Unproven accuracy | Dynamic change of miRNA and overlap between individuals doubt the reliability. | |

| TME markers | IHC for PD-L1 ssGSEA TILs score IHC for TILs |

Mansfield [2016]50 Jia [2018]27 Haratake [2018]51 Hu [2021]52 Izumi [2021]53 Yang [2021]54 Izumi [2021]53 Hu [2021]52 |

Concordant rate in histopathology-diagnosed MPLCs Kappa tests in MPLCs |

41% (13/32) 22% (12/55) 54% (32/59) 92% (69/75) 75% (24/32) 45% (5/11) CD3+ 56% (18/32), FOXP3+ 44% (14/32) CD3+TILs and CD163+TAMs: heterogeneity. CD8 +TILs: homogeneity |

Guiding the selection of immunotherapy; Help reveal the biological behaviors of MLCs; | Unproven accuracy; Lack of unified techniques. | High negative rate of PD-L1 in MPLCs (75–96%) limits the reliability. High proportion of discordance against clinicopathological methods. | |

MLCs: multiple lung cancers. MPLCs: multiple primary lung cancers. IPMs: intrapulmonary metastasis. PCR: polymerase chain reaction. NGS: next-generation sequencing. LOH: loss of heterozygosity. aCGH: array-based comparative genomic hybridization. CNVs: copy number variations. WES: whole exome sequencing. miRNA: microRNA. TME: tumor immune microenvironment. IHC: immunohistochemistry. TILs: tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. TAMs: tumor-associated macrophages.

Table 2.

Comparison of NGS and histopathology in discriminating MLCs.

| First author [Year] | Sample (patients/tumors) | NGS panel (genes) | Clonality analysis |

Clinic-pathology methodsc | Inconclusive cases |

Changed diagnosis by NGS | Survival analysisd |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretationa | Special in defining MPLCsb | NGS | Clinic-pathology | NGS | Clinic-pathology | |||||

| Zheng [2020]58 | 18/41 | 4 | Empirical | – | HPE | 17% (3/18) | 6% (1/18) | 53% (8/15) | NA | |

| Donfrancesco [2020]59 | 24/50 | 14 | Empirical | – | CHA + IHC | 13% (3/24) | 0% | 38% (9/24) | PFS: p = 0.054 | PFS: p = 0.60 |

| Takahashi [2018]60 | 37/82 | 20 | Empirical | – | HPE | 0% | 46% (17/37) | 59% (22/37) | OS: p = 0.21 | OS: p = 0.70 |

| Mansuet-Lupo [2019]61 | 120/240 | 22 | Empirical | Sharing one frequent mutation plus MPLCs histology | CHA | 9% (11/120) | 0% | 27% (30/109) | OS: p = 0.5 | OS: p = 0.9 |

| Qiu [2020]62 | 44/88 | 22 | Empirical | – | CHA | 23% (10/44) | 0% | 9% (3/34) | NA | |

| Belardinilli [2021]63 | 10/24 | 22 | Empirical | Sharing one high-frequency driver mutation plus different mutation(s) | CHA + IHC | 10% (1/10) | 0% | 22% (2/9) | NA | |

| Goodwin [2021]10 | 40/80 | 24 | Bio-informatic | Clonality package | HPE | 0% | 0% | 18% (7/40) | OS: p < 0.05 | OS: p = 0.1 |

| Bruehl [2022]64 | 32/64 | 35 | Empirical | Sharing high-frequency driver mutation (s) | HPE | 25% (8/32) | NA | 17% (4/24) | OS: p = 0.78 | NA |

| Patel [2017]65 | 11/31 | 50 | Empirical | Using distant metastasis to establish the reference concordant rate | CHA | 0% | 27% (3/11) | 27% (3/11) | OS: p = 0.09 | NA |

| Saab [2017]66 | 18/52 | 50 | Empirical | – | HPE + IHC | 6% (1/18) | 33% (6/18) | 6% (1/17) | NA | |

| Roepman [2018]34 | 50/111 | 50 | Empirical | Sharing high-frequency driver mutation (s) | CHA + IHC | 4% (2/53 pairs) | 0% | 37% (19/51 pairs) | OS: p = 0.061 | OS: p = 0.644 |

| Ezer [2021]67 | 61/131 | 52 | Bio-informatic | Self-proposed algorithm | CHA | 13% (8/61) | 13% (8/61) | 23% (12/53) | NA | |

| Goto [2017]68 | 12/25 | 53 | Empirical | – | HPE | 0% | 0% | 25% (3/12) | NA | |

| Higuchi [2020]55 | 37/76 | 53 | Empirical | – | HPE | 0% | 0% | 30% (11/37) | NA | |

| Chang [2019]18 | 60/128 | 341–468 | Empirical | Manual review of low-VAF and synonymous mutations when sharing a single hotspot mutation | CHA | 0% | 30% (23/76) | 22% (17/76 pairs) | PFS: p = 0.197 | NA |

| Yang [2021]69 | 24/48 | 410–468 | Empirical | Probabilities of chance co-occurrence of mutations as supplement | HPE (all being invasive mucinous) | 0% | 0% | 4% (1/24) | NA | |

| Liu [2020]70 | 16/40 | 464 | Empirical | – | HPE | 0% | 6% (1/16) | 14% (2/14) | NA | |

| Duan [2020]71 | 16/36 | 520 | Empirical | – | CHA | 0% | 0% | 12% (3/25 pairs) | NA | |

| Wang [2021]72 | 51/116 | 605 | Empirical | Sharing one high-frequency driver mutation ± one low-frequency mutation | HPE | 0% | 0% exclude all IPMs | 0% | NA | |

| Pei [2021]73 | 30/67 | 808 | Empirical | Sharing only EGFR L858R | MM | 0% | 0% | 47% (14/30) | NA | |

MLCs: multiple lung cancers. CHA: comprehensive histology assessment. IHC: immunohistochemistry. NGS: next-generation sequencing. HPE: histopathology examination. MM: Martini-Melamed criterion. OS: overall survival. PFS: progression-free survival. NA: not available or not applicable. VAF: variant allele frequency.

The “Bioinformatic” analysis means that the probability of clonal correlation between lesions was calculated while the “Empirical” interpretation did not.

In empirical analysis, MPLCs were usually defined as cases with different mutations or as cases where one tumor had a mutation and the other tumor was wild-type. Here “Special” refers to the definition which was supplemented by the original literature aside from the above-mentioned definition.

HPE refers to a pathological assessment method that evaluates the main pathological types and subtypes but does not belong to CHA.

Compare the prognosis of MPLCs and IPMs discriminated according to NGS or clinic-pathology.

Regarding the sampling of MLCs, tissue sequencing has dominated current research on MLCs discrimination, while liquid biopsy is still in its early stage. However, liquid biopsy has fabulous potential, especially in capturing of the heterogenous molecular alterations shed by spatially distinct tumors in a non-invasive manner.74 In the case of staged surgeries, the detection of discordant mutations in the circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) prior to the first resection compared to those in tissue provide clues to the presence of MPLCs.75 On the other hand, the sharp decrease in ctDNA concentration of the resected tumor76 suggests that differences in the mutational profiles between the pre- and post-operative blood tests may reflect the characteristics of unresected lesions. However, differences or concordance in mutations present in plasma and/or tissue alone are insufficient for discriminating MLCs. Incorporating signatures to identify the tissue origin could facilitate more credible diagnoses, such as methylation profiles and nucleosome positioning.77 As for further management, apart from the promising implications in efficacy prediction and recurrence monitoring,78 ctDNA allows the identification of more aggressive tumor in MLCs, which contains outgrowing subclones with greater shedding, and inform different treatments.74 Further studies are required to understand the roles of other types of liquid biopsy such as circulating tumor cells, exosomes, and circulating RNA 78 in discriminating MLCs.

Immunohistochemistry-based

The approach of discriminating MLCs with expression profiles examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) is conceptually similar to the discrimination based on somatic mutations17,32,34 (Table 1). In the early years with only few gene being tested, p53 staining was used to help discriminate additional cases.32 However, the discrepancy between protein expression and mutations may cause misdiagnoses. Take p53 as an example, a weak p53 staining usually implies a wild-type, whereas strong expression indicates missense mutations and absence corresponds to truncating stop-gain mutations.34 Alarming rate of inconsistency, ranging from 23% to 47%, have been reported about the above matching relationships, leading to confusion in discrimination.21,34 Combining IHC panels and transcription factors and other detection can relieve this confusion.59 Ono et al. successfully discriminated 70 cases of MLCs utilizing the sum value of the expression differences of p53, p16, p27, and c-erbB2.33 IHC markers of immunology (discussed later) are also of diagnostic interest.

Chromosome variations

Chromosomal variations have long been used in discriminating MLCs (Table 1 and Fig. 1). A lower agreement in copy number variations (CNVs) across chromosomes was observed in MPLCs (19.6%) compared to IPMs (55.5%).43 Matching amplifications and losses between paired tumors usually indicate the same origin. Murphy et al. developed an algorithm for lineage analysis by scoring the concordance of CNVs.48 The uniqueness of CNV patterns also ensures specificity.11,79 The chromosomal rearrangement breakpoint in MLCs is also a definitive marker for clonality analysis, as discordant mapping junctions detected by mate-pair sequencing point to MPLCs.47,48 Slippage during DNA replication in microsatellites (MSTs) can lead to loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and CNVs.80 Thus, polymorphic MST markers were used in early studies to detect these variations35, 36, 37, 38, 39 (Table 1). The targeted chromosomal loci usually contained hotspot genes, including 17p13.1 (TP53), 13q14 (Rb), or even general chromosomal arms.35, 36, 37,81 However, a substantial number of cases remain with no LOH when the loci were limited. This could be difficult to interpret since different and identical LOHs can appear together, which may hinder conclusive evidence. To overcome such limitations, interpretation based on changing trends of LOHs is a valuable alternative, as it is theoretically rooted in the allelic deletion during cancer evolution. The interpretation of this approach commences with the assumption of the same origin, followed by recognizing differentially expressed MST markers between two lesions. If these markers display consistent strength in lesion 1 and weakness in lesion 2, it is reasonable to assert that lesion 2 developed from lesion 1. In contrast, when the evolutionary sequence suggested by the trends is contradictory within the tumor pair, the hypothesis is overthrown, and MPLCs are diagnosed.40,41 However, current studies did not compare prognoses, so reliability cannot be confirmed. Notably, the proportion of polymorphic loci for MST in the human genome surpasses that of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) with minimal diversity,80 holding the potential for information that somatic mutations may fail to provide.

Potential molecule-based methods for discriminating MLCs

DNA methylation

DNA methylation, a ubiquitous epigenetic silencing mechanism, exhibits a greater level of universality than somatic mutations,82 tissue-specificity, and relative stability,83 rendering it an attractive avenue to discriminate MLCs. Despite a lack of comprehensive research on MLCs, DNA methylation profiles have been leveraged to identify the tissue origin of unknown primary malignancies based on mapping to a comprehensive atlas,77 intra-sample methylation orderings of the CpG sites,84 similarity of regional patterns to a specific cancer type,82 tightly coupled CpG sites termed methylation haplotypes85 and so on. These mechanisms have demonstrated promise for molecular analysis of clonal relatedness. However, methylation profiles in lung adenocarcinomas bear even greater intratumor heterogeneity than inter-tumor,86 which might impede the use of methylation profile in dissimilarity-based discriminations.

MicroRNA

MicroRNA (miRNA) has emerged as a promising biomarker for discriminating MLCs due to its close association with tumor behaviors, stability in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE), and simplicity of extraction facilitate. Zhou et al.49 detected five lung cancer-related miRNAs and calculated the fold changes of their expression compared to the internal control, which were summed up afterwards for each tumor. The differences in the sum values between matched tumors were utilized to assess clonality, based on a cut-off determined by the primary-metastatic lymph node pairs. Although miRNA analysis drew different diagnoses from histology in 25% (6/24) of cases (Table 1), the overall survival of MPLCs and IPMs stratified by miRNA appeared similar. While this does not necessarily imply inaccuracy, the feasibility of miRNA-based identification warrants reconsideration. This is because the miRNA profiles of lung cancer specimens from different patients overlap to some extent,87 indicating the divergent or similar expression of several selected miRNAs may be insufficient to identify MLCs. Therefore, further studies involving a more comprehensive miRNA spectrum are required to evaluate the discriminating efficacy.

Tumor microenvironment (TME) markers

The variations in routinely tested TME markers among tumors also provide a potential perspective to identify the clonal relatedness of MLCs (Fig. 1). PD-L1 expression exhibit a higher concordance between IPM lesions compared to MPLC lesions,50 however, the gap is insufficient to discriminate MLCs, which is approximately 88.9% in IPMs and 52.2%–75% in MPLCs50,53 (Table 1). The geographical heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression50,51 and the low positive expression rate of PD-L1 in MPLCs impede the classification accuracy, as only 4–25% of tumors show positive expression of PD-L1 in MPLCs.27,50, 51, 52, 53 Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) could serve as a potential marker for discriminating MLCs, depending on the resemblance of their residentiary profiles theoretically, which are usually derived from staining of specific membrane molecules52,53 or deconvolution of RNA sequencing data54 (Table 1). However, a purely holistic comparison is unlikely to succeed in discrimination as 75% of IPMs bear heterogeneous immune statuses and 29% of MPLCs present with homogeneity.54 In contrast, analysis of specific subpopulations may be useful, for instance, CD3+TILs and CD163+tumor-associated macrophages display significant heterogeneity within MPLCs while CD8+TILs do not.52 Another marker, tumor mutation burden (TMB), is probably not qualified for differential diagnosis owing to the hurdle to establish a reliable cut-off value or range from current studies, where the measured TMBs vary significantly from each other and large overlaps exist between MPLCs and IPMs.18,52,53,88 TME features are indispensable in future multiomic discrimination in the context of precision therapy but still demand further verification. Notably, TME markers may not apply to the discrimination of all MLCs, particularly those with indolent microenvironment such as multiple ground-glass nodules (GGNs). In most circumstance, they are considered as MPLCs,7 however, differential diagnosis is still in need since some appear to be IPMs based on genomic profiles.46,70,71,89,90 Moreover, patients with multiple GGNs have been found to exhibit no-response to PD-1 inhibitors, negative PD-L1 expression, downregulation of HLA-related genes, and defective T-cell functions.91 In these patients, testing negative or low-level TME markers would hardly benefit the differential diagnosis.

Challenges in genomics-based discrimination of MLCs

Detection technology selection

Various conventional technologies have been employed to detect genetic alterations, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH),7 and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (Fig. 1).92 However, there is no consensus established on which technique is more effective, while certain clinical laboratories lack the capabilities required for their implementation. Meanwhile, the results obtained from different methods might contradict one another.35,92 In the case of FISH, most available samples are FFPE specimens rather than fresh sections, which may lead to the false-negative results due to the biochemical contamination in the preparation.92 These classic technologies only provided limited evidence over the past decade. Thankfully, the emergence of NGS has increased the promise of more effective approaches than the traditional Sanger PCR.10,57 With the aid of bioinformatic tools, NGS has the potential to mine the sequencing data beyond somatic mutations, grabbing information at the chromosomal level or beyond. However, the vast amount of more macroscopic genomic information from NGS is still underutilized in previous studies, encouraging the exploration of their combined application with somatic mutations.44 The advantages and disadvantages of the main techniques are summarized in Table 1. Moreover, beyond the conventional techniques, the cutting-edge innovations, such as plus subclone reconstruction,90,93 metabolomics,94 and multiomics,91 hold tremendous potential to aid scientists in unraveling the intricate complexities of MLC. Nevertheless, the clinical implementation of these techniques remains impossible as they may be deemed too “extravagant” despite their ability to effectively distinguish MLCs.

Issues related to NGS applications

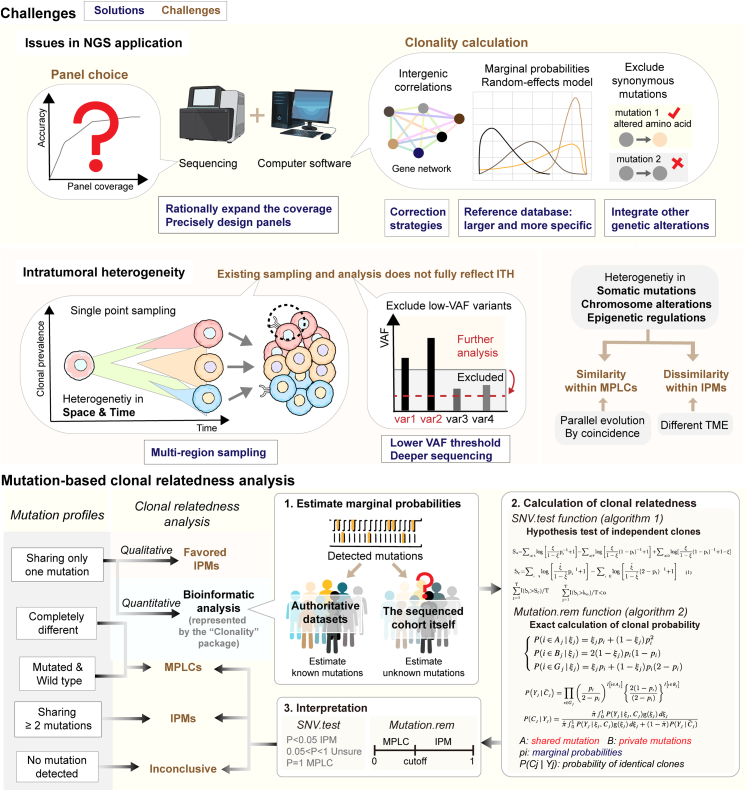

Panel choice

Currently, the optimal scope of NGS panels has been a topic of debate in the field (Fig. 3). In general, the use of wider panels for clonality assessment yields higher accuracy owing to larger-scale capture of mutations.18,60 Begg et al. suggested that to achieve a promising level of accuracy, the number of candidate genes in a panel should be more than twenty.95 Furthermore, the proportion of indeterminate IPMs increases more rapidly than that of MPLCs as the panel size decreases, indicating the use of large panels in suspected IPM patients.18 Nevertheless, a larger panel does not necessarily translate to the higher probability of benefit. Zheng and his colleagues58 obtained similar results with a 48-genes test and a panel that only cover 4 driver genes. Higuchi et al.55 managed to classify all tumor pairs with an elaborately designed panel covering 53 genes, achieving similar efficiency to the panels covering over 300 genes. Notably, some tumors had no detectable mutations even with the application of 808-gene panel.73 In other words, a targeted and precise design of a panel with a few genes covered is more sensible than a blind expansion of gene coverage.

Fig. 3.

Challenges in genomics-based discrimination of MLCs and clonal relatedness analysis. The upper part of this figure illustrates the main challenges faced by genomics-based discrimination, except for the choice of detection technology. Specific problems are highlighted in bold brown text, and possible solutions or research directions are presented in bold dark blue text within a box. Tumor cells of different colors represent different subclones. The lower part of this figure shows the common clonality analysis process based on somatic mutations in five different categories. The three-step calculation process for quantitative interpretation using software is depicted in detail. ITH: intratumoral heterogeneity. VAF: variant allele frequency. MPLCs: multiple primary lung cancers. IPMs: intrapulmonary metastasis. TME: tumor microenvironment. NGS: next-generation sequencing. GGNs: ground-glass nodules. P: probability.

Clonality analysis

The interpretation of sequencing results is quite empirical in most previous studies, typically defining MPLCs as two tumors with different mutations or one mutated plus the other wild type, and IPMs as two tumors with the same mutations29,34,60,65(Fig. 3). However, the probability of the same hotspot mutation occurring randomly in two independent tumors is not negligible, making it difficult to distinguish between IPMs and MPLCs.96 To address this, bioinformatic analyses have been developed for estimating the lineage of tumor pairs using bulk DNA sequencing.97 For instance, the widely used “Clonality” package estimates the marginal probabilities of detected mutations, and calculates a parameter to evaluate the clonal correlation using algorithms such as the random-effect model96,98,99 (Fig. 3). As presented in Table 2, only the study using bioinformatic analysis that discriminated MPLCs from IPMs with a significantly better prognosis.10 Another study using the same program to validate the proposed strategy did not achieve a significant difference, but more than half of the molecularly diagnosed IPM patients experienced relapse during follow-up, which was much worse than that of MPLC patients.18

Although bioinformatic analysis appears to be more reliable than empirical interpretation, new challenges arise in the following aspects (Fig. 3). First, the probabilities of frequently detected mutations are routinely estimated by reference to external authoritative datasets, whereas the reference when encountering rarely detected or unknown mutations is often the sequencing cohort itself.99 However, demographic distinctions have been revealed in the genomic landscape,100 underscoring the need for larger and population-specific datasets as references to avoid bias. Second, synonymous mutations, which are typically excluded, can provide additional information for discriminating inconclusive cases. For example, Bruin et al. confirmed a case of MPLCs after analyzing silent mutations, even if the tumors puzzlingly shared EGFR L858R.101 Notably, Chang et al. reported a median of 16 synonymous somatic alterations harbored by MLCs,18 suggesting that incorporating such additional markers could be useful in clonality assessment. Third, intergenic correlations might complicate the discrimination. Mutual exclusivity occurs among driver mutations with equivalent functions in tumorigenesis,5,18,61 while positive correlation leads to the cooccurrence of certain mutations,96 both of which cause bias in clonality analysis and require corresponding correction strategies. Additionally, it is also stimulating to creating alternative programs that integrate genomic variations of different levels to evaluate clonal relatedness.97

Intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH)

Cancers feature the accumulation of genetic abnormalities and dynamic development of subclones with distinct molecular variations.102 Somatic mutations are typically classified into trunk mutations, which arise ubiquitously as early events, and branch mutations within specific subclones.11 This model points out spatial and temporal heterogeneity inside tumors (Fig. 3), which can also involve other molecule alterations, such as epigenetics and some chromosome aberrations.102 In the case of discriminating MLCs, the presence of ITH presents challenges in sampling, testing, and interpretation, as massive subclonal events only appear in one specific region. Multipoint sampling can aid in quantifying ITH by enabling phylogenetic reconstructions and identification of clonal origin.11,97 However, routine exclusion of mutations with low variant allele frequency (VAF) results in an incomplete overview of ITH, as up to 30% of mutations have a VAF below 5%. Some of these mutations may be valuable for recognizing clonality.55,70 An appropriately lowered VAF threshold plus deeper sequencing seems feasible to deploy these scarce alterations in subclones and maintain detection accuracy.

The molecular congruence of IPMs and incongruence of MPLCs is well understood. However, MPLCs may also display molecular similarities due to parallel evolution from sharing carcinogen exposures93 or just by coincidence. Conversely, IPMs could be molecularly divergent due to the formation of ITH, different tumor microenvironments, and expression modifications. These phenomena are especially pronounced in downstream molecular markers, such as PD-L1 and microRNAs, probably due to the greater impact of extrinsic factors.49,50,53

Combining molecular approaches with histopathology

Comparison of histopathology and NGS

As the understanding of histopathological limitations deepens, researchers are exploring whether genetic methods can be more powerful. In recent years, NGS has advanced and found applications in various fields of genomic research.57 Dozens of studies have compared the efficacy of NGS-based methods in discriminating MLCs with that of histopathology (Table 2), suggesting the superiority of NGS to traditional histopathological methods. In general, the proportion of indeterminate cases by CHA range from 0 to 46%,58,60,65,67,70 while equivocal results by NGS account for 0–25% of all cases.34,58,59,63,64,67 Meanwhile, NGS leads to the correction of around 0–59% of pathological diagnoses, allowing for the correction of errors or inconclusive cases. Most importantly, NGS-based methods exhibit a more significant link to overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) than CHA, with the latter having higher p values.

Combining strategies and future perspectives

Histopathology-based approaches have demonstrated considerable advancements in discriminating MLCs but have now encountered an impasse. However, this does not imply that the established methods should be discarded. Rather, we aim to draw attention to the forthcoming epoch that integrates molecular analyses into traditional diagnostics. Genomic identification was routinely conducted in parallel with clinicopathology in most studies. As summarized in Table 1, Table 2, the discordance rate fluctuated from 0% to 63%, partially revealing the histopathological misdiagnoses where the molecular approaches could be complementary.17 But not all patients require both methods given the moderate accuracy of histopathology and the expense of molecular tests. Consequently, some researchers have investigated combining strategies. In all these studies, CHA and low-grade lepidic components were set as evidence for MPLCs with slight revisions. However, the indications, interpretation, testing platforms, and sequential relationship to histopathology of molecular methods vary from study to study (see Supplementary Table S1 for details). Xiao et al.103 adopted a protocol of “CHA-EGFR testing-50 genes NGS”, while Chang's18 strategy worked following “histology subtyping-driver genes testing-broad panel NGS” and was validated by bioinformatic analysis. Both Mansuet-Lupo61 and Shao6 additionally integrated tumor-free intervals in their algorithms. Shao6 first incorporated CT features such as GGNs or spiculation/lobulation of MPLCs. The performances of these algorithms were also various in terms of prognostic differentiation and inconclusive rates (Supplementary Table S1). There is apparent heterogeneity among the proposed combining algorithms. To date, it is still unclear which features of clinic-pathology-molecule should be incorporated and in what order these features should be arranged. Additionally, the situation where neither histopathology nor molecular methods lead to a definite diagnosis has yet to be resolved. To answer these questions, direct comparisons between molecular approaches are needed, such as simulating different panels by gene subsampling for the same study population while simultaneously carrying out empirical interpretation and bioinformatic analysis. To establish the in-process procedure of molecular-pathological and even clinical features, parallel comparisons of different workflows within the same study are also needed. Our team is also actively researching this field (NCT04326751) and hopes to provide reliable integrated strategies in the future. Along the same lines, we contend that it would be would be prudent to concurrently compare and combine potential markers, such as miRNA and TME, with the histological-genetic methods to better clarify their discriminating power and optimize protocols. In summary, despite the current lack of consensus on specific algorithms, combining diagnosis to confirm clonal relatedness is presently trending.

Conclusions

The far more satisfying prognosis of MPLCs compared to IPMs underscores the necessity of rigorous differentiation. With progressively advanced techniques and accumulating evidence, molecule-based strategies offer unprecedented opportunities to enhance the precision of discriminating MLCs. Genomics-based methods appear to be more mature and proven diagnostics, while molecular methods at other levels require further exploration and validation. Despite several challenges that still hamper the booming strategies, it is expected that these issues will be resolved in the future. More studies are necessary to authenticate, standardize, and further optimize molecule-based discrimination. In-depth research on MLCs will not only improve differential diagnosis but also guide the application of chemo-targeted-immune therapy for tumors with divergent characteristics.

Outstanding questions

Despite the significant advancements in molecule-based methods for discriminating multiple lung cancers (MLCs), there exist critical challenges surrounding the optimal selection, application, and interpretation of such testing. More critically, clinicians lack the access to explicit protocols for these molecular diagnostic methods now, and unsettled issues persist with regards to sequencing platform choice and postsequencing clonality analysis. The absence of direct comparative studies between molecular methods hinders the proposal of detailed recommendations. In addition, the lack of prognostic validation for certain molecular approaches, particularly nongenomic markers, makes it difficult to evaluate these potential markers' effectiveness. It's also a must-solved question about how to integrate molecular approaches with histopathology and maximize the accuracy and economy. To date, no international guidelines have provided specific responses to these issues. Consequently, a more precise, detailed, feasible, and authoritative operational consensus or guideline on molecular and integrated discrimination is needed.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

Data for this Review were identified by searches of PubMed between 2000 and 2022 (latest search date: 15th of Oct 2022) and cross-references from relevant articles, using the search terms “multiple lung cancers”, “MLCs”, “multiple primary lung cancers”, “MPLC”, “intrapulmonary metastasis”, and “IPM” in combination with “molecular”, “mutation”, “identify”, “differential diagnosis”, and “discriminate”. Only articles published in English were included. The final reference list was generated after screening the abstracts and reviewing in-depth the relevance to this Review. Most articles published within the last 5 years were used.

Contributors

Z.W. contributed to conceptualization, software, data curation, and manuscript drafting. X.Y. contributed to conceptualization, figure realization, manuscript drafting and revision. G.J. contributed to literature search, conceptualization, and manuscript revision. Y.L. offered critical suggestions to this article. F.Y. and J.W. contributed to supervision of this manuscript. K.C. reviewed the manuscript and provided critical feedback. All authors made substantial, direct, and intellectual contributions to the review. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82072566), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) 2022-I2M-C&T-B-120, National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.92059203), Research Unit of Intelligence Diagnosis and Treatment in Early Non-small Cell Lung Cancer, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences(2021RU002) and Peking University People's Hospital Research and Development Funds (RZ2022-03). The funders had no role in paper design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation and writing of the paper. The authors would also like to thank Yichen Jin (Peking University Health Science Center), Yuntao Nie, MD (China-Japan Friendship Hospital), Bengang Hui, MD (Tangdu Hospital, The Fourth Military Medical University) for their help in literature research and discussion of conception.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104508.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Horeweg N., Scholten E.T., de Jong P.A., et al. Detection of lung cancer through low-dose CT screening (NELSON): a prespecified analysis of screening test performance and interval cancers. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1342–1350. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen J.H., Ashraf H., Dirksen A., et al. The Danish randomized lung cancer ct screening trial- overall design and results of the prevalence round. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):608–614. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a0d98f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heuvelmans M.A., Walter J.E., Peters R.B., et al. Relationship between nodule count and lung cancer probability in baseline CT lung cancer screening: the NELSON study. Lung Cancer. 2017;113:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shintani Y., Okami J., Ito H., et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with stage I multiple primary lung cancers. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(5):1924–1935. doi: 10.1111/cas.14748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mascalchi M., Comin C.E., Bertelli E., et al. Screen-detected multiple primary lung cancers in the ITALUNG trial. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(2):1058–1066. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shao J., Wang C., Li J., et al. A comprehensive algorithm to distinguish between MPLC and IPM in multiple lung tumors patients. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(18):1137. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detterbeck F.C., Nicholson A.G., Franklin W.A., et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: summary of proposals for revisions of the classification of lung cancers with multiple pulmonary sites of involvement in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(5):639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang L., He J., Shi X., et al. Prognosis of synchronous and metachronous multiple primary lung cancers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2015;87(3):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian S., Li F., Pu J., et al. Differential diagnostic value of histology in MPLC and IPM: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.871827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin D., Rathi V., Conron M., Wright G.M. Genomic and clinical significance of multiple primary lung cancers as determined by next-generation sequencing. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(7):1166–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamal-Hanjani M., Wilson G.A., McGranahan N., et al. Tracking the evolution of non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2109–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozower B.D., Larner J.M., Detterbeck F.C., Jones D.R. Special treatment issues in non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 SUPPL):e369S–e399S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girard N., Deshpande C., Lau C., et al. Comprehensive histologic assessment helps to differentiate multiple lung primary nonsmall cell carcinomas from metastases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(12):1752–1764. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b8cf03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson A.G., Torkko K., Viola P., et al. Interobserver variation among pathologists and refinement of criteria in distinguishing separate primary tumors from intrapulmonary metastases in lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(2):205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng H., Feng L.B., Peng P.J., Lin Y.J., Wang X.J. Histologic lung cancer subtype differentiates synchronous multiple primary lung adenocarcinomas from intrapulmonary metastases. J Surg Res. 2017;211:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson A.G., Tsao M.S., Beasley M.B., et al. The 2021 WHO classification of lung tumors: impact of advances since 2015. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(3):362–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voulaz E., Novellis P., Rossetti F., et al. Distinguishing multiple lung primaries from intra-pulmonary metastases and treatment implications. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2020;20(11):985–995. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2020.1823223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang J.C., Alex D., Bott M., et al. Comprehensive next-generation sequencing unambiguously distinguishes separate primary lung carcinomas from intrapulmonary metastases: comparison with standard histopathologic approach. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(23):7113–7125. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell J.D., Alexandrov A., Kim J., et al. Distinct patterns of somatic genome alterations in lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2016;48(6):607–616. doi: 10.1038/ng.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Rens M.T.M., Eijken E.J.E., Elbers J.R.J., Lammers J.W.J., Tilanus M.G.J., Slootweg P.J. P53 mutation analysis for definite diagnosis of multiple primary lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94(1):188–196. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang Y.L., Wu C.T., Lin S.C., Hsiao C.F., Jou Y.S., Lee Y.C. Clonality and prognostic implications of p53 and epidermal growth factor receptor somatic aberrations in multiple primary lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(1):52–58. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung J.H., Choe G., Jheon S., et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation and pathologic-radiologic correlation between multiple lung nodules with ground-glass opacity differentiates multicentric origin from intrapulmonary spread. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(12):1490–1495. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181bc9731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girard N., Deshpande C., Azzoli C.G., et al. Use of epidermal growth factor receptor/kirsten rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog mutation testing to define clonal relationships among multiple lung adenocarcinomas: comparison with clinical guidelines. Chest. 2010;137(1):46–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takamochi K., Oh S., Matsuoka J., Suzuki K. Clonality status of multifocal lung adenocarcinomas based on the mutation patterns of EGFR and K-ras. Lung Cancer. 2012;75(3):313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C.T., Lin M.W., Hsieh M.S., Kuo S.W., Chang Y.L. New aspects of the clinicopathology and genetic profile of metachronous multiple lung cancers. Ann Surg. 2014;259(5):1018–1024. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun W., Feng L., Yang X., et al. Clonality assessment of multifocal lung adenocarcinoma by pathology evaluation and molecular analysis. Hum Pathol. 2018;81:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia X., Zhang L., Wu W., Zhang W., Wu C. Driver mutation analysis and PD-L1 expression in synchronous double primary lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018;26(4):246–253. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider F., Derrick V., Davison J.M., Strollo D., Incharoen P., Dacic S. Morphological and molecular approach to synchronous non-small cell lung carcinomas: impact on staging. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(7):735–742. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asmar R., Sonett J.R., Singh G., Mansukhani M.M., Borczuk A.C. Use of oncogenic driver mutations in staging of multiple primary lung carcinomas: a single-center experience. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(10):1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu D., Cao D., Shen M., Lv J. Morphological and genetic heterogeneity of synchronous multifocal lung adenocarcinoma in a Chinese cohort. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-07892-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu L., Chen J., Zeng Y., Li X., Zhang Z. Differential diagnosis of multiple primary lung cancers and intra-lung metastasis of lung cancer by multiple gene detection. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135(1):86–88. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiroshima K., Toyozaki T., Kohno H., Ohwada H., Fujisawa T. Synchronous and metachronous lung carcinomas: molecular evidence for multicentricity. Pathol Int. 1998;48(11):869–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ono K., Sugio K., Uramoto H., et al. Discrimination of multiple primary lung cancers from intrapulmonary metastasis based on the expression of four cancer-related proteins. Cancer. 2009;115(15):3489–3500. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roepman P., ten Heuvel A., Scheidel K.C., et al. Added value of 50-gene panel sequencing to distinguish multiple primary lung cancers from pulmonary metastases: a systematic investigation. J Mol Diagn. 2018;20(4):436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu S., Yatabe Y., Koshikawa T., et al. High frequency of clonally related tumors in cases of multiple synchronous lung cancers as revealed by molecular diagnosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(10):3994–3999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang J., Behrens C., Wistuba I., Gazdar A.F., Jagirdar J. Molecular analysis of synchronous and metachronous tumors of the lung: impact on management and prognosis. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5(6):321–329. doi: 10.1053/adpa.2001.29338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dacic S., Ionescu D.N., Finkelstein S., Yousem S.A. Patterns of allelic loss of synchronous adenocarcinomas of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(7):897–902. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000164367.96379.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X., Wang M., MacLennan G.T., et al. Evidence for common clonal origin of multifocal lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(8):560–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warth A., Macher-Goeppinger S., Muley T., et al. Clonality of multifocal nonsmall cell lung cancer: implications for staging and therapy. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(6):1437–1442. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00105911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen C., Xu H., Liu L., et al. ‘Unique trend’ and ‘contradictory trend’ in discrimination of primary synchronous lung cancer and metastatic lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen C., Wang X., Tian L., et al. ‘Different trend’ in multiple primary lung cancer and intrapulmonary metastasis. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40001-015-0109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Girard N., Ostrovnaya I., Lau C., et al. Genomic and mutational profiling to assess clonal relationships between multiple non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(16):5184–5190. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arai J., Tsuchiya T., Oikawa M., et al. Clinical and molecular analysis of synchronous double lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(2):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y., Zhang J., Li L., et al. Genomic heterogeneity of multiple synchronous lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincenten J.P.L., van Essen H.F., Lissenberg-Witte B.I., et al. Clonality analysis of pulmonary tumors by genome-wide copy number profiling. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou D., Liu Q.X., Yuan L.M., et al. Utility of whole exome sequencing analysis in differentiating intrapulmonary metastatic multiple ground-glass nodules (GGNs) from multiple primary GGNs. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27(5):871–881. doi: 10.1007/s10147-022-02134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy S.J., Aubry M.C., Harris F.R., et al. Identification of independent primary tumors and intrapulmonary metastases using DNA rearrangements in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4050–4058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.7644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy S.J., Harris F.R., Kosari F., et al. Using genomics to differentiate multiple primaries from metastatic lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(9):1567–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou X., Tian L., Fan J., et al. Method for discriminating synchronous multiple lung cancers of the same histological type: MiRNA expression analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(31):1–8. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mansfield A.S., Murphy S.J., Peikert T., et al. Heterogeneity of programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in multifocal lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(9):2177–2182. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haratake N., Toyokawa G., Takada K., et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression and EGFR mutations in multifocal lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu C., Zhao L., Liu W., et al. Genomic profiles and their associations with TMB, PD-L1 expression, and immune cell infiltration landscapes in synchronous multiple primary lung cancers. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(12):1–15. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Izumi M., Sawa K., Oyanagi J., et al. Tumor microenvironment disparity in multiple primary lung cancers: impact of non-intrinsic factors, histological subtypes, and genetic aberrations. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(7) doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang R., Li P., Wang D., et al. Genetic and immune characteristics of multiple primary lung cancers and lung metastases. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:2544–2550. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.14134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higuchi R., Nakagomi T., Goto T., et al. Identification of clonality through genomic profile analysis in multiple lung cancers. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):573. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ettinger D.S., Wood D.E., Aisner D.L., et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(5):497–530. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cainap C., Balacescu O., Cainap S.S., Pop L.A. Next generation sequencing technology in lung cancer diagnosis. Biology (Basel) 2021;10(9):1–15. doi: 10.3390/biology10090864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng R., Shen Q., Mardekian S., Solomides C., Wang Z.X., Evans N.R. Molecular profiling of key driver genes improves staging accuracy in multifocal non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160(2):e71–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.11.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donfrancesco E., Yvorel V., Casteillo F., et al. Histopathological and molecular study for synchronous lung adenocarcinoma staging. Virchows Arch. 2020;476(6):835–842. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02736-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi Y., Shien K., Tomida S., et al. Comparative mutational evaluation of multiple lung cancers by multiplex oncogene mutation analysis. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(11):3634–3642. doi: 10.1111/cas.13797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mansuet-Lupo A., Barritault M., Alifano M., et al. Proposal for a combined histomolecular algorithm to distinguish multiple primary adenocarcinomas from intrapulmonary metastasis in patients with multiple lung tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(5):844–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qiu T., Li W., Zhang F., Wang B., Ying J. Major challenges in accurate mutation detection of multifocal lung adenocarcinoma by next-generation sequencing. Cancer Biol Ther. 2020;21(2):170–177. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2019.1674070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Belardinilli F., Pernazza A., Mahdavian Y., et al. A multidisciplinary approach for the differential diagnosis between multiple primary lung adenocarcinomas and intrapulmonary metastases. Pathol Res Pract. 2021;220 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2021.153387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bruehl F.K., Doxtader E.E., Cheng Y.W., Farkas D.H., Farver C., Mukhopadhyay S. Does histological assessment accurately distinguish separate primary lung adenocarcinomas from intrapulmonary metastases? A study of paired resected lung nodules in 32 patients using a routine next-generation sequencing panel for driver mutations. J Clin Pathol. 2022;75(6):390–396. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2021-207421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel S.B., Kadi W., Walts A.E., et al. Next-generation sequencing: a novel approach to distinguish multifocal primary lung adenocarcinomas from intrapulmonary metastases. J Mol Diagn. 2017;19(6):870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saab J., Zia H., Mathew S., Kluk M., Narula N., Fernandes H. Utility of genomic analysis in differentiating synchronous and metachronous lung adenocarcinomas from primary adenocarcinomas with intrapulmonary metastasis. Transl Oncol. 2017;10(3):442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ezer N., Wang H., Corredor A.G., et al. Integrating NGS-derived mutational profiling in the diagnosis of multiple lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021;29 doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Mochizuki H., et al. Mutational analysis of multiple lung cancers: discrimination between primary and metastatic lung cancers by genomic profile. Oncotarget. 2017;8(19):31133–31143. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang S.R., Chang J.C., Leduc C., et al. Invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas with spatially separate lung lesions: analysis of clonal relationship by comparative molecular profiling. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(7):1188–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu J., Mao G., Li Y., et al. Targeted deep sequencing helps distinguish independent primary tumors from intrapulmonary metastasis for lung cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(9):2359–2367. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03227-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duan J., Ge M., Peng J., et al. Application of large-scale targeted sequencing to distinguish multiple lung primary tumors from intrapulmonary metastases. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75935-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang X., Gong Y., Yao J., et al. Establishment of criteria for molecular differential diagnosis of MPLC and IPM. Front Oncol. 2021;10:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.614430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 73.Pei G., Li M., Min X., et al. Molecular identification and genetic characterization of early-stage multiple primary lung cancer by large-panel next-generation sequencing analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.653988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gilson P., Merlin J.L., Harlé A. Deciphering tumour heterogeneity: from tissue to liquid biopsy. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:1384. doi: 10.3390/cancers14061384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen K., Zhang J., Chen W., et al. Identifying genomic alteration and inter-tumor heterogeneity of multiple primary lung cancers by targeted NGS of tumor tissue and ctDNA. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(1):S442–S443. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen K., Zhao H., Shi Y., et al. Perioperative dynamic changes in circulating tumor DNA in patients with lung cancer (Dynamic) Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(23):7058–7067. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moss J., Magenheim J., Neiman D., et al. Comprehensive human cell-type methylation atlas reveals origins of circulating cell-free DNA in health and disease. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5068. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07466-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shen H., Jin Y., Zhao H., et al. Potential clinical utility of liquid biopsy in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02681-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ren Y., Huang S., Dai C., et al. Germline predisposition and copy number alteration in pre-stage lung adenocarcinomas presenting as ground-glass nodules. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Payseur B.A., Jing P., Haasl R.J. A genomic portrait of human microsatellite variation. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(1):303–312. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leong P.P., Rezai B., Koch W.M., et al. Distinguishing second primary tumors from lung metastases in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(13):972–977. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.13.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu M.C., Oxnard G.R., Klein E.A., et al. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(6):745–759. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carter B., Zhao K. The epigenetic basis of cellular heterogeneity. Nat Rev Genet. 2021;22(4):235–250. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00300-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu H., Chen J., Chen H., et al. Identification of the origin of brain metastases based on the relative methylation orderings of CpG sites. Epigenetics. 2021;16(8):908–916. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2020.1827720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guo S., Diep D., Plongthongkum N., Fung H.L., Zhang K., Zhang K. Identification of methylation haplotype blocks AIDS in deconvolution of heterogeneous tissue samples and tumor tissue-of-origin mapping from plasma DNA. Nat Genet. 2017;49(4):635–642. doi: 10.1038/ng.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dietz S., Lifshitz A., Kazdal D., et al. Global DNA methylation reflects spatial heterogeneity and molecular evolution of lung adenocarcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(5):1061–1072. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guarize J., Bianchi F., Marino E., et al. MicroRNA expression profile in primary lung cancer cells lines obtained by endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(1):408–415. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.12.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liang N., Bing Z., Wang Y., et al. Clinical implications of EGFR-associated MAPK/ERK pathway in multiple primary lung cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(5):1–5. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen K., Chen W., Cai J., et al. Favorable prognosis and high discrepancy of genetic features in surgical patients with multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(1):371–379.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ren Y., Song M., She Y., et al. Deconstructing the intra-tumor subclonal heterogeneity of lung synchronous ground-glass nodules using whole-genome sequencing. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):2021–2023. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang C., Yin K., Liu S.Y., et al. Multiomics analysis reveals a distinct response mechanism in multiple primary lung adenocarcinoma after neoadjuvant immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(4):1–6. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Letovanec I., Finn S., Zygoura P., et al. Evaluation of NGS and RT-PCR methods for ALK rearrangement in European NSCLC patients: results from the European Thoracic Oncology platform lungscape project. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(3):413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.11.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ma P., Fu Y., Cai M.C., et al. Simultaneous evolutionary expansion and constraint of genomic heterogeneity in multifocal lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):823. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00963-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aredo J.v., Purington N., Su L., et al. Metabolomic profiling for second primary lung cancer: a pilot case-control study. Lung Cancer. 2021;155:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Begg C.B., Eng K.H., Hummer A.J. Statistical tests for clonality. Biometrics. 2007;63(2):522–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ostrovnaya I., Seshan V.E., Begg C.B. Using somatic mutation data to test tumors for clonal relatedness. Ann Appl Stat. 2015;9(3):1533–1548. doi: 10.1214/15-AOAS836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kader T., Zethoven M., Gorringe K.L. Evaluating statistical approaches to define clonal origin of tumours using bulk DNA sequencing: context is everything. Genome Biol. 2022;23(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s13059-022-02600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mauguen A., Seshan V.E., Begg C.B., Ostrovnaya I. Testing clonal relatedness of two tumors from the same patient based on their mutational profiles: update of the Clonality R package. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(22):4776–4778. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mauguen A., Seshan V.E., Ostrovnaya I., Begg C.B. Estimating the probability of clonal relatedness of pairs of tumors in cancer patients. Biometrics. 2018;74(1):321–330. doi: 10.1111/biom.12710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen J., Yang H., Teo A.S.M., et al. Genomic landscape of lung adenocarcinoma in East Asians. Nat Genet. 2020;52(2):177–186. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.de Bruin E.C., McGranahan N., Mitter R., et al. Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science. 2014;346(6206):251–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1253462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McGranahan N., Swanton C. Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell. 2017;168(4):613–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xiao F., Zhang Z.R., Wang X.W., et al. Applying comprehensive histologic assessment and genetic testing to synchronous multifocal lung adenocarcinomas and further survival analysis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2019;132(2):227–231. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.