Highlights

-

•

Sustainable emerging sonication processing is used for chlorothalonil fungicide reduction in spinach juice.

-

•

Results indicated that sonication treatments significantly reduced the chlorothalonil fungicide concentration.

-

•

Also described chlorothalonil proposed degradation pathway after sonication treatment along with intermediate products.

-

•

It also significantly improved the availability of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities.

Keywords: Sonication, Chlorothalonil, Degradation pathway, Spinach juice, Bioactive compounds

Abstract

Among different novel technologies, sonochemistry is a sustainable emerging technology for food processing, preservation, and pesticide removal. The study aimed to probe the impact of high-intensity ultrasonication on chlorothalonil fungicide degradation, reduction pathway, and bioactive availability of spinach juice. The chlorothalonil fungicide-immersed spinach juice was treated with sonication at 360 W, 480 W, and 600 W, 40 kHz, for 30 and 40 min at 30 ± 1 °C. The highest reduction of chlorothalonil fungicide residues was observed at 40 min sonication at 600 W. HPLC-MS (high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy) analysis revealed the degradation pathway of chlorothalonil and the formation of m-phthalonitrile, 3-cyno-2,4,5,6-tetrachlorobenamide, 4-dichloroisophthalonitrile, trichloroisophtalonitrile, 4-hydoxychlorothalonil, and 2,3,4,6-tetrachlorochlorobenzonitrile as degradation products. High-intensity sonication treatments also significantly increased the bioavailability of phenolic, chlorophyll, and anthocyanins and the antioxidant activity of spinach juice. Our results proposed that sonication technology has excellent potential in degrading pesticides through free radical reactions formation and pyrolysis. Considering future perspectives, ultrasonication could be employed industrially to reduce pesticide residues from agricultural products and enhance the quality of spinach juice.

1. Introduction

Pesticides are agrochemicals used to control pests, fungi, rodents, or diseases and enhance the production of crops [1], [2]. The excessive use of agrochemicals is a high risk to human wellness [2]. Various studies proved that agrochemicals and other toxic chemicals are present over maximum residual limits (MRL) set by the drug regulatory authorities in agricultural and livestock products [3], [4]. According to the environmental protection agency (EPA), it was estimated that nearly 3 × 109 kg of pesticides are used worldwide, and it is projected that 20 % of the pesticides are eaten in developing countries. In comparison, 80 % of pesticides are estimated to be eaten in developed countries [5].

Fresh agricultural products such as spinach (Spinacia oleracea) are essential to the human diet because they provide us with vitamins, minerals, glucosinolates, carotenoids, and bioactive compounds [6]. Studies reported that fresh agricultural products transported into the market were detected with high MRL of pesticides [7]. Among the pesticides, chlorothalonil is one of the most commonly used fungicides for spinach [8]. It is an alarming issue for the consumer's health, as it causes cancer, skin issues, cardiovascular diseases, and damages the nervous system [9]. Recently, researchers have been focussing on safely removing pesticide residues from fresh agricultural products. However, different physical, chemical, and biological processes have been adopted to remove pesticides.

Among novel technologies, sonication, a sustainable emerging technology for pesticide removal or degradation in aqueous conditions, has recently drawn researchers' attention. Sonication processing produces cavitation that helps with pesticide reduction [8], [10], [11]. Based on sonication intensity, there are two kinds of cavitations: transient and stable. As transient cavitation, in a short time under high sonication intensity, bubbles gain the required size quickly and burst, which would induce high temperature (>5000 K) and pressure (>100 MPa) [12], [13]. It provokes pesticide pyrolysis and cell breakdown to stimulate reactions between pesticide residues and reactive specie. Moreover, the sonication cavitation phenomenon also induces free radicals, which react with pesticides in the liquid medium [12], [14]. During sonication, pesticide reduction might be associated with an increased OH* radical, which helps break down the pesticide's mother compound [15]. Lozowicka, Jankowska, Hrynko and Kaczynski [16] reported that sonication cleaning significantly removed the pesticide residues from strawberry fruits, ranging from 19.8 % to 91.2 %. Moreover, the effectiveness of sonication processing for pesticide removal or degradation depends on sonication treatment time, frequency, acoustic power, intensity, environmental conditions, and the pesticide's molecular properties [17]. The novelty of the current study is to find out the effect of different power with various sonication treatments time to enhance residual degradation of fungicide. Furthermore, this study aimed to investigate the possible reduction pathways of chlorothalonil fungicide and possible by-products. We used HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography) and HPLC-MS (high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy) to estimate the residual degradation of pesticides.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Juice extraction and sonication treatment

Fresh spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves were obtained from the local market. Spinach leaves (1 Kg) without the stem were washed to remove dust before the experiments. Spinach leaves juice was extracted using a manual juice extractor (Wuhan Acme Agro-Tech Co., ltd. Hubei, China), and chlorothalonil solution (5 mg/L) was added to the spinach juice and later processed with sonication. Sonication water (JP-031S, Shenzhen, China) cleaner was employed to treat juice samples. A 100 mL spinach juice was treated for 0, 30, and 40 min at a frequency of 40 kHz and 360, 480, and 600 W. The temperature was kept at 40 °C throughout the treatment period using a water circulation flow rate kept at 0.5 L/min. The sonication parameters (treatment time, temperature, frequency, and power) were selected based on the extensive literature study and initial trials.

2.2. Determination of chlorothalonil fungicide

The fungicide residues in the treated samples were extracted using QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe). Briefly, 10 mL of a well-homogenized treated sample was transferred in a 50 mL centrifuge tube, followed by 10 mL of acetonitrile, 4 g of magnesium sulfate, and 1 g of NaCl. The resultant mixture was thoroughly mixed and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 min. Three milliliters of supernatant were transferred to a 10 mL tube containing 60 mg of PSA, and the mixture was centrifuged again at 400 rpm for 2 min. Finally, 1 mL of the sample was filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe. The filtered sample was passed through an HPLC system (AcQuity® Arc™, MA, USA) to measure chlorothalonil degradation. The HPLC system was equipped with a 2998 PDA detector at 227 nm and a C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm) with a particle size of 2.5 μm and a detection limit of 0.005 mg/L. The HPLC conditions were as follows: inject volume = 20 μL, flow rate = 1 mL/min, column temperature = 40 ◦C, and mobile phase = 70 % methanol plus 30 % water.

2.3. Degradation rate

The following equation was used to calculate chlorothalonil residue degradation (%):

| (1) |

C0 and Cf is the initial and final concentration (mg/kg) of residues before and after treatment, respectively.

2.4. HPLC-MS analysis

The investigation of the chlorothalonil fungicide by-products was done with HPLC-MS. The LC-MS (Thermo Scientific™ System, Bremen, Germany) furnished with C-18 column (1.9 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm) was used to determine the degradation product by taking 1 mL of treated samples filtered with 0.2 µm syringe before analysis. The mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany) was performed with positive and negative ion modes with heated electrospray ions source at a gas temperature of 350 ℃ with a flow rate of 15 mL/min, VCap of 3500 V and 3.50 kV voltage of spray. Further, the mobile phase A was 0.1 % formic acid with water, B was with acetonitrile, and the injection time was 10 µL. The mobile phase was calibrated with 2 % acetonitrile for two minutes, then increased to 100 % for 24 min at the flow rate of 0.24 mL/min. The compound discovered software version 2.1 was used to identify the degradation products.

2.5. Determination of total phenolics (TPC), chlorophyll, and anthocyanins

The TPC of the spinach juice was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method [18]. For this, spinach juice samples (1 mL), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1 mL), and 75 % (w/v) sodium carbonate solution (3 mL) were mixed, and the volume of the mixture was adjusted to 10 mL with distilled water. The reaction was allowed to complete in a dark environment for 15 min, and then the absorbance was measured at 760 nm by spectrophotometer (TU-1810, Beijing, China). TPC results were described as GAE µg/g. A pH differential method was adopted to estimate total anthocyanin, as reported by Aadil et al. [19].

The chlorophyll contents were measured using a previously established method [20]. Three milliliters of spinach juice were mixed with 3 mL of acetone (80 % v/v) and filtered through Whatman filter paper three times. The absorbance of the filtered solution was measured at 645 and 663 nm. The total chlorophyll contents were calculated according to the following formula:

| (2) |

2.6. Antioxidant activity

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the samples was measured using the method proposed by Manzoor et al. [21]. Equal amounts of spinach juice and DPPH solution (0.2 mM) were mixed and incubated for 30 min at 25 ± 1 °C in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm, and DPPH activity was estimated as equation (3);

| (3) |

2.7. Statistical analysis

The samples were analyzed in triplicates for each experiment. The final results were analyzed using SPSS statistics 18.0 (IBM 24, USA) through one-way ANOVA, and the results were presented as mean ± SD. Duncan Multiple Range tests were used to compare means using a significance level at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Impact of ultrasonication on the chlorothalonil degradation rate

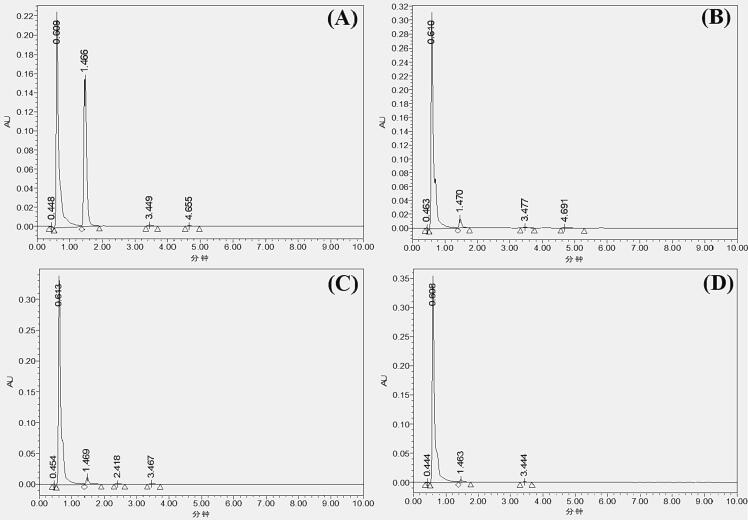

The presence of organic compounds such as pesticides greatly concerns the adverse health effects. The conventional methods are ineffective in achieving the desired residual removal goal; they also affect the products' physicochemical and nutritional values. So, novel sonication technology was adopted to degrade chlorothalonil from spinach juice. The different sonication times and acoustic powers were applied to achieve a maximum degradation of chlorothalonil, as presented in Fig. 1. The results revealed that the chlorothalonil degradation rate was significantly affected (p < 0.05) by increasing sonication time and powers power at a constant frequency of 40 kHz. The HPLC chromatograph for chlorothalonil residues showed a single peak at a retention time (RT) of 1.469 min, indicating the quantity of remaining chlorothalonil residues after different sonication treatments in each sample (Fig. 2). The exhibited peak was specified as chlorothalonil by comparing the chromatogram with the standard chromatogram peak.

Fig. 1.

Impact of different sonication treatments on the degradation of chlorothalonil. UT: untreated juice, S1: sonication at 40 kHz, 360 W for 30 mint, S2: sonication at 40 kHz and 360 W for 40 mint, S3: sonication at 40 kHz and 480 W for 30 mint, S4: sonication at 40 kHz and 480 W for 40 mint, S5: sonication at 40 kHz and 600 W for 30 mint, and S6: sonication at 40 kHz and 600 W for 40 mint.

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatograph for chlorothalonil in different samples. untreated juice, (B) sonication at 40 kHz and 360 W for 40 mint, (C) sonication at 40 kHz and 480 W for 40 mint, and (D) sonication at 40 kHz and 600 W for 40 mint.

Firstly, sonication frequency has a notable impact on the degradation or removal of pesticides; it might be associated with rates of hydroxyl radical formation depending on the sonication frequency. Moreover, sonication frequency influences are based on the molecule's nature and reaction localization. Many authors, Weavers, Malmstadt and Hoffmann [22], Kida, Ziembowicz and Koszelnik [23], Debabrata and Sivakumar [24], and Golash and Gogate [25] reported that the degradation of pesticide minimum at lower sonication frequencies (20 kHz) and reported degradation increased by increasing sonication frequency up to 40 kHz.

Secondly, acoustic power plays a significant part in the removal or degradation of pesticides during sonication. The literature stated that sonication reactivity improves proportionately with increased acoustic power. Our results exhibited that the degradation rate of increasing acoustic power from 360 to 600 W significantly increased (p < 0.05). The finding clearly stated that an increase in power leads to increased cavitation bubbles and OH* radicals concentration. In addition, an increase in acoustic power also enhances the bubbles' size, leading to higher collapse temperatures [26]. Schramm and Hua [27] studied the impact of different acoustic power (86–161 W) on dichlorvos degradation and documented that the increasing acoustic power rate of degradation constantly increased. Similar outcomes were declared by Zhang, Zhang, Liao, Zhang, Hou, Xiao, Chen and Hu [28], Golash and Gogate [25], Shayeghi, Dehghani and Fadaei [29], and Agarwal, Tyagi, Gupta, Dehghani, Bagheri, Yetilmezsoy, Amrane, Heibati and Rodriguez-Couto [30]. Debabrata and Sivakumar [24] studied the dicofol degradation under sonolysis in an aqueous medium and recorded an increase in acoustic power up to 375 W increasing the degradation rate. They possibly demonstrated their outcomes by extreme heat formation during sonication, directing to a less damaging bubble collapse.

Thirdly, the efficiency of sonochemical pesticide degradation is based on time, and degradation rises with time. Our results showed that the degradation rate significantly increased (p < 0.05) by increasing sonication time from 30 to 40 min. It might be the opportunity for the pesticide residues and cavitation process for reaction to be improved by extending the degradation time. The standard scope of required degradation times for the sonication treatment ranges from 5 to 60 min. Earlier, a study reported degradation of azinphos-methyl at a sonication time of 20 to 60 min. The authors observed that the degradation of azinphos-methyl increased by increasing time from 20 to 60 min [30]. Overall, two types of mechanisms are involved in pesticide degradation during sonication. The first is pyrolysis inside the cavitation bubbles, the main reaction route for degrading or removing hydrophobic and more volatile compounds. The second is hydroxyl radicals forming in cavitation bubbles oxidize the organic compounds, which are hydrophilic and nonvolatile after the bubbles collapse [26], [31], [32].

So, our results align with Lozowicka, Jankowska, Hrynko and Kaczynski [16], who reported that ultrasonic cleaning reduced the pesticide residues by 45 to 89 % from strawberry fruit and revealed that the effectiveness of the reduction depends on the nature of the compound. Kidak and Dogan [33] reported that pesticide (alachlor) reduction depends on acoustic power and frequency; the highest reduction was observed at 575 kHz and 90 W.

3.2. Chlorothalonil by-products and proposed reduction pathway

To explore the pesticide degradation mechanism, 100 mL (1 g/L) aqueous chlorothalonil was treated with sonication at 600 W for 40 min; the degradation by-products were investigated using HPLC-MS. The outcomes described based on the molecular weight, RT, and ion number (m/z), six intermediate products such as m-phthalonitrile, trichloroisophtalonitrile, 4-dichloroisophthalonitrile, 4-hydoxychlorothalonil, 2,3,4,6-tetrachlorochlorobenzonitrile, and 3-cyno-2,4,5,6-tetrachlorobenamide were identified as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intermediate products after LC-MS analysis.

| Intermediate product | MW (g) | Ions (m/z) | RT (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trichloroisophtalonitrile | 231.9 | 232.9 | 0.96 |

| 4-dichloroisophthalonitrile | 162.02 | 163.02 | 18.87 |

| m-phthalonitrile | 128.05 | 129.03 | 1.94 |

| 2,3,4,6-tetrachlorochlorobenzonitrile | 240.9 | 241.0 | 6.36 |

| 4-hydoxychlorothalonil | 247.5 | 248.01 | 14.37 |

| 3-cyno-2,4,5,6-tetrachlorobenamide | 265.50 | 266.03 | 18.48 |

Based on HPLC-MS examination and the determined intermediate products, the proposed degradation path of chlorothalonil through sonication treatment was presented in Fig. 3. The degradation pathway of chlorothalonil is usually based on the different treatment parameters. Various mechanisms were observed: (a) addition of the hydroxyl group in chlorothalonil, (b) 4-chlorine atoms were displaced through hydrolytic dechlorination to form trichloroisophtalonitrile to m-phthalonitrile, (c) oxidative dechlorination formed the 4-hydoxychlorothalonil, (d) base hydrolysis formed 3-cyno-2,4,5,6-tetrachlorobenamide, (e) 4-hydoxychlorothalonil formed might also be possible by hydrolysis, and (f) reductive decyanation formed 2,3,4,6-tetrachlorochlorobenzonitrile under the aerobic condition. Chlorothalonil degradation is normally initiated by substituting chlorine with a hydroxyl group or hydrogen [34]. Lv, Zhang, Shi, Dai, Li, Wu, Li, Tang, Wang and Li [35] reported that the chlorothalonil bonds (C N and C-Cl) were broken by the act of OH radicals, which have been documented to remove organics through radical reactions. The other pesticide reduction has also been documented by Sajjadi, Khataee, Bagheri, Kobya, Şenocak, Demirbas and Karaoğlu [36], Agarwal, Tyagi, Gupta, Dehghani, Bagheri, Yetilmezsoy, Amrane, Heibati and Rodriguez-Couto [30], Liu, Jin, Lu and Han [37] and Bagal and Gogate [38] to be associated with OH and O groups generated during sonication, and their results were consistent with our findings.

Fig. 3.

Proposed degradation pathway of chlorothalonil after sonication treatment.

Overall the pesticide degradation phenomena occur inside cavitation bubbles during sonication; oxygen molecules and water vapor go through thermal separation to generate various highly reactive radicals (HO*2, HO*, and H*). These sonolysis radicals react with dissolved inorganic and organic compounds directing to oxidation and hydroxylation reactions [22], [39]. During sonolysis, an uncomplicated mechanism for the radical generation from water is defined below [40];

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

OH*radical is one of the most potent oxidants that can react non-selectively with all kinds of inorganic and organic compounds, and the confined organic compounds in the bubble react with the OH* radical or go through pyrolysis [41]. A high-temperature rise at the interface of gas–liquid bubbles directs to locally condensed hydroxyl radicals, and a degradation reaction ensues in the aqueous medium. Although this region's temperature is lower than the bubble core, there is enough temperature (high) for the thermal disintegration of the substrate. Besides, H2O2 can be induced by an association of OH* radicals during sonolysis, which play a vital part in oxidizing organic species (reactions equations (7), (8)).

| (9) |

| (10) |

Lv, Zhang, Shi, Dai, Li, Wu, Li, Tang, Wang and Li [35] also reported chlorothalonil photodegradation in water due to the break of C–Cl bonds and proposed that the generation of H2O2 and *OH removed or degraded the pesticide through free radical reactions.

3.3. Impact of sonication of bioactive compounds

Bioactive compounds such as TPC, anthocyanin, and total chlorophyll play an essential role in human wellness by inhibiting the threat of diseases and enhancing food quality like color and taste [42], [43], [44]. The TPC, anthocyanin, and total chlorophyll content of the sonicated spinach juice compared to untreated juice is presented in Table 2. The results revealed that the TPC, chlorophyll, and total anthocyanin contents were significantly (p < 0.05) increased to 725.23 µg/g, 57.19 µg/mL, and 42.90 µg/mL compared to untreated, 664.34 µg/g, 44.12 µg/mL and 33.3 µg/mL, respectively. The results also indicated that an increase in ultrasonic power and treatment time positively impacted bioactive compounds. The increment in bioactive compounds might be linked with the release of the bound phenolics through the cavitation process by cell rapturing or enhancing the mass transfer rate through micro-cavities production [45], [46], [47].

Table 2.

Impact of sonication on bioactive compounds of spinach juice.

| Treatments | TPC (GAE µg/g) | Anthocyanins (µg/ml) | Total chlorophyll (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UT | 664.34 ± 0.12f | 33.3 ± 0.07d | 44.12 ± 0.08d |

| S1 | 694.54 ± 0.16e | 38.6 ± 0.09c | 47.43 ± 0.05c |

| S2 | 710.76 ± 0.19c | 39.2 ± 0.05bc | 49.62 ± 0.11c |

| S3 | 718.81 ± 0.09b | 40.8 ± 0.11b | 53.71 ± 0.13b |

| S4 | 725.23 ± 0.14a | 42.9 ± 0.13a | 56.82 ± 0.09a |

| S5 | 716.12 ± 0.08b | 40.2 ± 0.08b | 57.19 ± 0.07a |

| S6 | 704.91 ± 0.11d | 37.4 ± 0.06c | 52.11 ± 0.08b |

Different letters within the same column are significant (p < 0.05). All values are presented as mean ± SD.

UT: untreated juice, S1: sonication at 40 kHz, 360 W for 30 mint, S2: sonication at 40 kHz and 360 W for 40 mint, S3: sonication at 40 kHz and 480 W for 30 mint, S4: sonication at 40 kHz and 480 W for 40 mint, S5: sonication at 40 kHz and 600 W for 30 mint, and S6: sonication at 40 kHz and 600 W for 40 mint.

Moreover, the increase in bioactive compounds is linked with the highest antioxidant activity in the final product [19]. Recently some studies revealed that the sonication process increased the bioactive compounds in strawberries [48] and carrot juice [49] and stated that the relationship between bioactive compound enhancement is due to the microstructural changes in fruit juice through sonication. The sonication treatment causes the sequence of structural modifications, which involves unbroken tissue to cell breakdown. It can cause two main things: nutrients and bioactive compounds may be degraded during sonication or more accessible when exposed [50]. Our study observed a similar trend at a higher intensity and longer sonication time. Overall, the application of sonication could enhance the quality of fruit juice.

3.4. Impact of sonication of antioxidant activity

The results of the DPPH activity percent retention of spinach juice are depicted in Fig. 4. Results indicated that high-intensity sonicated treatments significantly improve (p < 0.05) the percent retention of DPPH compared to the untreated sample. The percent retention of DPPH significantly improved by increasing the acoustic power and time, but a significant decline in antioxidant activity was observed at the highest acoustic power (600 W) and sonication time. The peak value of antioxidant retention (82.3 %) was observed at 480 W and 40 min of sonication. Our results reveal that sonication processing improves bioactive compounds' extraction rate, which is directly related to antioxidant activities. The increase in antioxidant activity is linked with the highest amount of polyphenols induced through high-power sonication generated by the cavitation process, which enhanced the extractability of bioactive compounds [51], [52], [53]. Some researchers associated the increase in antioxidant ability with the minimized formation of free hydroxyl radicals during sonication [54], [55], [56]. In contrast, at high acoustic power and extended time, a maximum level of free hydroxyl radicals was generated, which has been reported as harming the antioxidant activities [57], [58]. Similar outcomes have been reported in sonicated strawberry juice [48], Kasturi lime [59], and orange and carrot juice [60].

Fig. 4.

Impact of high-intensity sonication on DPPH assay and results are presented in % retention. UT: untreated juice, S1: sonication at 40 kHz, 360 W for 30 mint, S2: sonication at 40 kHz and 360 W for 40 mint, S3: sonication at 40 kHz and 480 W for 30 mint, S4: sonication at 40 kHz and 480 W for 40 mint, S5: sonication at 40 kHz and 600 W for 30 mint, and S6: sonication at 40 kHz and 600 W for 40 mint.

4. Conclusion

Research demonstrated that emerging sonication technology effectively degraded the chlorothalonil fungicide by up to 73.3 % at an extended time and higher acoustic power. Our results proposed that sonication technology has excellent potential in degrading pesticides through free radical reactions formation and pyrolysis. The degradation rate depends on sonochemical time, frequency and power. Moreover, the results revealed a significant increase in bioactive compounds (TPC, anthocyanins, and chlorophyll) and the DPPH activity of spinach juice. Moreover, the results revealed a significant increase in bioactive compounds (TPC, anthocyanins, and chlorophyll) and the DPPH activity of spinach juice. But a decrease in bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity was observed at an extended time and acoustic power.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Murtaza Ali: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Muhammad Faisal Manzoor: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Gulden Goksen: Writing – original draft, Software, Data curation. Rana Muhammad Aadil: Writing – original draft, Software, Data curation. Xin-An Zeng: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Muhammad Waheed Iqbal: Writing – original draft, Software, Data curation. Jose Manuel Lorenzo: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The authors want to acknowledge the support of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Intelligent Food Manufacturing, Foshan University, Foshan 528225, China (Project ID:2022B1212010015).

Funding for open access charges Universidade de Vigo/CISUG.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Faisal Manzoor, Email: faisaluos26@gmail.com.

Xin-An Zeng, Email: xazeng@scut.edu.cn.

Jose Manuel Lorenzo, Email: jmlorenzo@ceteca.net.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.M.A. Dar, G. Kaushik, J.F.V. Chiu, Pollution status and biodegradation of organophosphate pesticides in the environment, in: Abatement of environmental pollutants, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 25–66.

- 2.Lan T., Cao F., Cao L., Wang T., Yu C., Wang F. A comparative study on the adsorption behavior and mechanism of pesticides on agricultural film microplastics and straw degradation products. Chemosphere. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135058. 135058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ping H., Wang B., Li C., Li Y., Ha X., Jia W., Li B., Ma Z. Potential health risk of pesticide residues in greenhouse vegetables under modern urban agriculture: A case study in Beijing, China. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2022;105 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubey J., Sharma A. Sustainable Management of Potato Pests and Diseases. Springer; 2022. Pesticide residues and international regulations; pp. 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alshemmari H., Al-Shareedah A.E., Rajagopalan S., Talebi L.A., Hajeyah M. Pesticides driven pollution in Kuwait: the first evidence of environmental exposure to pesticides in soils and human health risk assessment. Chemosphere. 2021;273 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manzoor M.F., Ahmed Z., Ahmad N., Aadil R.M., Rahaman A., Roobab U., Rehman A., Siddique R., Zeng X.A., Siddeeg A. Novel processing techniques and spinach juice: quality and safety improvements. J. Food Sci. 2020;85:1018–1026. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nisha U.S., Khan M.S.I., Prodhan M.D.H., Meftaul I.M., Begum N., Parven A., Shahriar S., Juraimi A.S., Hakim M.A. Quantification of pesticide residues in fresh vegetables available in local markets for human consumption and the associated health risks. Agronomy. 2021;11:1804. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali M., Sun D.-W., Cheng J.-H., Esua O.J. Effects of combined treatment of plasma activated liquid and ultrasound for degradation of chlorothalonil fungicide residues in tomato. Food Chem. 2022;371 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali M., Cheng J.-H., Sun D.-W. Effect of plasma activated water and buffer solution on fungicide degradation from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit. Food Chem. 2021;350 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan S., Li C., Zhang Y., Yu H., Xie Y., Guo Y., Yao W. Ultrasound as an emerging technology for the elimination of chemical contaminants in food: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;109:374–385. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yıkmış S. Sensory, physicochemical, microbiological and bioactive properties of red watermelon juice and yellow watermelon juice after ultrasound treatment. J. Food Measure. Characteriz. 2020;14:1417–1426. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang A.-A., Sutar P.P., Bian Q., Fang X.-M., Ni J.-B., Xiao H.-W. Pesticide residue elimination for fruits and vegetables: the mechanisms, applications, and future trends of thermal and non-thermal technologies. J. Future Foods. 2022;2:223–240. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yıkmış S., Bozgeyik E., Şimşek M.A. Ultrasound processing of verjuice (unripe grape juice) vinegar: effect on bioactive compounds, sensory properties, microbiological quality and anticarcinogenic activity. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;57:3445–3456. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04379-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yıkmış S., Aksu H., Çöl B.G., Alpaslan M. Thermosonication processing of quince (Cydonia Oblonga) juice: effects on total phenolics, ascorbic acid, antioxidant capacity, color and sensory properties. Ciência e Agrotecnol. 2019;43 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshmukh N.S., Deosarkar M.P. A review on ultrasound and photocatalysis-based combined treatment processes for pesticide degradation. Proc. Mater. Today. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lozowicka B., Jankowska M., Hrynko I., Kaczynski P. Removal of 16 pesticide residues from strawberries by washing with tap and ozone water, ultrasonic cleaning and boiling. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016;188:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4850-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y., Zhang T., Xu D., Wang S., Yuan Y., He S., Cao Y. The removal of pesticide residues from pakchoi (Brassica rape L. ssp. chinensis) by ultrasonic treatment. Food Control. 2019;95:176–180. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navajas-Porras B., Pérez-Burillo S., Morales-Pérez J., Rufián-Henares J., Pastoriza S. Relationship of quality parameters, antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content of EVOO with ripening state and olive variety. Food Chem. 2020;325 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aadil R.M., Zeng X.A., Wang M.S., Liu Z.W., Han Z., Zhang Z.H., Hong J., Jabbar S. A potential of ultrasound on minerals, micro-organisms, phenolic compounds and colouring pigments of grapefruit juice. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015;50:1144–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao L., Wang S., Liu F., Dong P., Huang W., Xiong L., Liao X. Comparing the effects of high hydrostatic pressure and thermal pasteurization combined with nisin on the quality of cucumber juice drinks. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013;17:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzoor M.F., Ahmad N., Aadil R.M., Rahaman A., Ahmed Z., Rehman A., Siddeeg A., Zeng X.A., Manzoor A. Impact of pulsed electric field on rheological, structural, and physicochemical properties of almond milk. J. Food Process Eng. 2019;42:e13299. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weavers L.K., Malmstadt N., Hoffmann M.R. Kinetics and mechanism of pentachlorophenol degradation by sonication, ozonation, and sonolytic ozonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000;34:1280–1285. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kida M., Ziembowicz S., Koszelnik P. Removal of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) from aqueous solutions using hydrogen peroxide, ultrasonic waves, and a hybrid process. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2018;192:457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Debabrata P., Sivakumar M. Sonochemical degradation of endocrine-disrupting organochlorine pesticide Dicofol: Investigations on the transformation pathways of dechlorination and the influencing operating parameters. Chemosphere. 2018;204:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golash N., Gogate P.R. Degradation of dichlorvos containing wastewaters using sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012;19:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pirsaheb M., Moradi N. Sonochemical degradation of pesticides in aqueous solution: investigation on the influence of operating parameters and degradation pathway–a systematic review. RSC Adv. 2020;10:7396–7423. doi: 10.1039/c9ra11025a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schramm J.D., Hua I. Ultrasonic irradiation of dichlorvos: decomposition mechanism. Water Res. 2001;35:665–674. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(00)00304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y., Zhang W., Liao X., Zhang J., Hou Y., Xiao Z., Chen F., Hu X. Degradation of diazinon in apple juice by ultrasonic treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010;17:662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shayeghi M., Dehghani M., Fadaei A. Removal of malathion insecticide from water by employing acoustical wave technology. Iran. J. Public Health. 2011;40:122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal S., Tyagi I., Gupta V.K., Dehghani M.H., Bagheri A., Yetilmezsoy K., Amrane A., Heibati B., Rodriguez-Couto S. Degradation of azinphos-methyl and chlorpyrifos from aqueous solutions by ultrasound treatment. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;221:1237–1242. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekiguchi K., Sasaki C., Sakamoto K. Synergistic effects of high-frequency ultrasound on photocatalytic degradation of aldehydes and their intermediates using TiO2 suspension in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Y.L., Li J.T., Chen H. Degradation of CI Acid Red 88 aqueous solution by combination of Fenton's reagent and ultrasound irradiation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol.: Int. Res. Process, Environ. Clean Technol. 2009;84:578–583. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kidak R., Dogan S. Degradation of trace concentrations of alachlor by medium frequency ultrasound. Chem. Eng. Process.: Process Intensif. 2015;89:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katayama A., Itou T., Ukai T. Ubiquitous capability to substitute chlorine atoms of chlorothalonil in bacteria. J. Pestic. Sci. 1997;22:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lv P., Zhang J., Shi T., Dai L., Li X., Wu X., Li X., Tang J., Wang Y., Li Q.X. Procyanidolic oligomers enhance photodegradation of chlorothalonil in water via reductive dechlorination. Appl. Catal. B. 2017;217:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sajjadi S., Khataee A., Bagheri N., Kobya M., Şenocak A., Demirbas E., Karaoğlu A.G. Degradation of diazinon pesticide using catalyzed persulfate with Fe3O4@ MOF-2 nanocomposite under ultrasound irradiation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019;77:280–290. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y.-N., Jin D., Lu X.-P., Han P.-F. Study on degradation of dimethoate solution in ultrasonic airlift loop reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagal M.V., Gogate P.R. Sonochemical degradation of alachlor in the presence of process intensifying additives. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2012;90:92–100. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghodbane H., Hamdaoui O. Degradation of Acid Blue 25 in aqueous media using 1700 kHz ultrasonic irradiation: ultrasound/Fe (II) and ultrasound/H2O2 combinations. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009;16:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chitra S., Paramasivan K., Sinha P., Lal K. Ultrasonic treatment of liquid waste containing EDTA. J. Clean. Prod. 2004;12:429–435. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chowdhury P., Viraraghavan T. Sonochemical degradation of chlorinated organic compounds, phenolic compounds and organic dyes–a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2009;407:2474–2492. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yikmiş S. Effect of ultrasound on different quality parameters of functional sirkencubin syrup. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;40:258–265. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doguer C., Yıkmış S., Levent O., Turkol M. Anticancer effects of enrichment in the bioactive components of the functional beverage of Turkish gastronomy by supplementation with purple basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and the ultrasound treatment. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021;45:e15436. [Google Scholar]

- 44.N.T. Demirok, S. Yıkmış, Combined effect of ultrasound and microwave power in tangerine juice processing: bioactive compounds, amino acids, minerals, and pathogens, processes, 10 (2022) 2100.

- 45.Costa M.G.M., Fonteles T.V., de Jesus A.L.T., Almeida F.D.L., de Miranda M.R.A., Fernandes F.A.N., Rodrigues S. High-intensity ultrasound processing of pineapple juice. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013;6:997–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X., Zhang L., Peng Z., Zhao Y., Wu K., Zhou N., Yan Y., Ramaswamy H.S., Sun J., Bai W. The impact of ultrasonic treatment on blueberry wine anthocyanin color and its In-vitro anti-oxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2020;333 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yikmiş S. Investigation of the effects of non-thermal, combined and thermal treatments on the physicochemical parameters of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) juice. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2019;25:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J., Wang J., Ye J., Vanga S.K., Raghavan V. Influence of high-intensity ultrasound on bioactive compounds of strawberry juice: profiles of ascorbic acid, phenolics, antioxidant activity and microstructure. Food Control. 2019;96:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasheminya S.M., Dehghannya J. Non-thermal processing of black carrot juice using ultrasound: intensification of bioactive compounds and microbiological quality. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022;57:5848–5858. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rojas M.L., Kubo M.T., Caetano-Silva M.E., Augusto P.E. Ultrasound processing of fruits and vegetables, structural modification and impact on nutrient and bioactive compounds: a review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;56:4376–4395. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manzoor M.F., Xu B., Khan S., Shukat R., Ahmad N., Imran M., Rehman A., Karrar E., Aadil R.M., Korma S.A. Impact of high-intensity thermosonication treatment on spinach juice: bioactive compounds, rheological, microbial, and enzymatic activities. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manzoor M.F., Hussain A., Goksen G., Ali M., Khalil A.A., Zeng X.-A., Jambrak A.R., Lorenzo J.M. Probing the impact of sustainable emerging sonication and DBD plasma technologies on the quality of wheat sprouts juice. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manzoor M.F., Hussain A., Naumovski N., Ranjha M.M.A.N., Ahmad N., Karrar E., Xu B., Ibrahim S.A. A narrative review of recent advances in rapid assessment of anthocyanins in agricultural and food products. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.901342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yıkmış S., Aksu H. Effects of natamycin and ultrasound treatments on red grape juice. Fresen. Environ. Bull. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manzoor M.F., Siddique R., Hussain A., Ahmad N., Rehman A., Siddeeg A., Alfarga A., Alshammari G.M., Yahya M.A. Thermosonication effect on bioactive compounds, enzymes activity, particle size, microbial load, and sensory properties of almond (Prunus dulcis) milk. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manzoor M.F., Hussain A., Sameen A., Sahar A., Khan S., Siddique R., Aadil R.M., Xu B. Novel extraction, rapid assessment and bioavailability improvement of quercetin: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qureshi T.M., Nadeem M., Maken F., Tayyaba A., Majeed H., Munir M. Influence of ultrasound on the functional characteristics of indigenous varieties of mango (Mangifera indica L.) Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.104987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed Z., Manzoor M.F., Hussain A., Hanif M., Zeng X.-A. Study the impact of ultra-sonication and pulsed electric field on the quality of wheat plantlet juice through FTIR and SERS. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;76 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhat R., Kamaruddin N.S.B.C., Min-Tze L., Karim A. Sonication improves kasturi lime (Citrus microcarpa) juice quality. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18:1295–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khandpur P., Gogate P.R. Effect of novel ultrasound based processing on the nutrition quality of different fruit and vegetable juices. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;27:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.