ABSTRACT

Background:

Major depression disorder (MDD) is a mental disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. This disease has negative impacts on quality of life and psychological-related functions. This is a multifactorial disorder; both genetic background and environmental factors have their role. Antidepressants are prescribed as the first line of treatment for patients with depressive disorders. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants are used to treat MDD and anxiety; however, some patients do not respond to them. Regarding that, magnesium plays a major role in mood regulation; therefore, this study aimed to investigate the role of magnesium supplement in patients with MDD and under an SSRI treatment regimen.

Methods:

In this randomized, double-blind controlled trial, 60 patients with major depressive disorders based on the DSM-V diagnosis referred to Golestan Hospital in Ahvaz, Iran, were included. The eligible patients were categorized randomly into two thirty-people groups receiving magnesium (intervention) and placebo (control) along with SSRI for 6 weeks. To evaluate the depression status, the Beck II test was applied. Subjects were examined before and after the intervention.

Results:

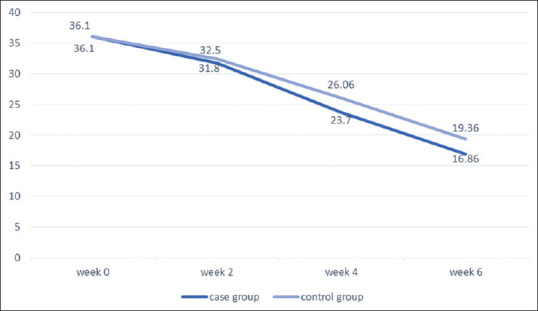

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics (P > 0.05). The mean Beck scores at the beginning of the study and the second week after the intervention were not different between the two groups (P = 0.97, P = 0.56), whereas the mean Beck scores were lower in the intervention group than in the control group in the fourth and sixth weeks after the intervention (P = 0.02 and P = 0.001, respectively).

Conclusion:

Administration of Mg supplement for at least 6 weeks might improve depression symptoms. It can also be considered as a potential adjunct treatment option for MDD patients who are under SSRI treatment.

Keywords: Magnesium supplement, major depression disorder (MDD), multifactorial disorder

Introduction

Major depression disorder (MDD) is considered one of the most common mental illnesses that affect roughly 350 million people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) reports, depression is a prominent cause of disability.[1,2] MDD is either short-term or long-term, and if left untreated, it has negative consequences on affection, mood, cognition, motivation, life quality, and psychological-related functions.[3,4] MDD is thought to be caused by multifactors, including genetic background, environment, and psychological factors, with genetic factors accounting for approximately 40% of the risk. It is noteworthy to mention that family history, chronic health issues, major life changes, and substance use are noted as MDD risk factors.

Antidepressants are prescribed as the first line of treatment for patients with depressive disorders. These antidepressant drugs are classified into four groups: selective serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Fluoxetine, which selectively inhibits serotonin reuptake, is the top in the SSRI category. All medicines in this category need hepatic metabolism and have an 18-to-24-hour half-life. Fluoxetine, on the other hand, has an active metabolite with a few days’ half-lives. Citalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine do not contain active long-acting metabolites. SSRI antidepressants are a subclass of medications used to treat MDD and anxiety. Although the exact mechanisms of these drugs are still to be found, they increase the amount of serotonin available for binding to synaptic receptors by reducing its reabsorption using presynaptic cells and increasing the amount of serotonin in the synaptic cleft. It seems that they also have roles in transporting some monoamines.[5] Considering that 19 − 34% of patients with depression do not respond to antidepressants and 15 − 50% of those who do experience a relapse, additional medicines or micronutrient supplements are increasingly used in addition to antidepressants to boost their therapeutic effectiveness.[6]

Nutrition plays a considerable role in depression’s etiology, progression, and treatment. Magnesium (Mg) is an essential mineral that is the body’s fourth most abundant cation and the second most significant intracellular cation. Magnesium functions as a cofactor in over 350 enzymes, the majority of which are involved in brain function. It plays an important role in mood regulation via modulating enzymes, hormones, and neurotransmitters.[7] Various animal and human studies have emphasized that magnesium supplements have beneficial impacts on depression. It has also been proven that magnesium is associated with the limbic system; therefore, its role in the progression and etiology of depression cannot be ignored.[8] Magnesium insufficiency may play a role in a variety of diseases, including neuromuscular, neurologic, cardiovascular, and electrolyte abnormalities.[9,10] Mg deficiency might be related to insufficient Mg intake, Mg loss in the kidney in several diseases such as diabetes and alcoholism, and taking some medications such as antidiuretics, cisplatin, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones.[11] Meanwhile, magnesium is necessary for energy generation, dysrhythmia prevention, blood pressure stabilization, insulin resistance prevention, and bone homeostasis.[12,13]

Due to the high prevalence of depression in the world and the contradictory results of studies on the role of magnesium in improving depressive symptoms and since limited studies have investigated the role of magnesium in the treatment of depression, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of Mg supplements in patients with MDD.

Material and Methods

Study design and participants

The current study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Sixty patients with major depression who were referred to Golestan Hospital affiliated with the Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences from June 2019 to December 2020 were included in this study. Patients over 18 years old with major depressive disorders based on the DSM-V diagnosed by a psychiatrist were eligible for the study.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: neurological disorders, active suicidal thoughts, consumption of alcohol and drugs during the last 6 months, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors intake during 8 weeks before the start of the study, allergies to antidepressants or magnesium supplements, consumption of medications that interfere with magnesium, pregnancy, suffering from diseases such as uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, mental retardation, history of seizures, liver, and renal failure. The eligible subjects were treated with SSRIs (sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, and fluvoxamine). Then, the selected patients were categorized randomly into two thirty-people groups receiving magnesium (intervention) and placebo (control) using a four-block randomization method both for the magnesium and the placebo group. The intervention group received a 250 mg/day magnesium supplement for 6 weeks. However, the placebo group received similar tablets with magnesium supplementation in terms of shape, color, and size for 6 weeks. Different SSRIs were prescribed to patients in similar and equivalent doses. All patients were followed up by the same psychiatrist at predetermined times: before treatment initiation, subsequently at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 6 weeks after treatment initiation.

Measurements and outcomes

A questionnaire was designed to collect all demographic and clinical data from the patients’ medical records. Information about the patient, including age, sex, marital status, current place of residence, level of education, level of economic income, as well as the duration of the disease, were recorded in the questionnaire. To assess the status of depression, Beck’s depression inventory II (BDI-II) was used. In this study, patients in both groups completed a Beck questionnaire before and after the intervention (at the beginning of the intervention, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 6 weeks after starting treatment). Then, the information of the two groups was compared. The Beck questionnaire has 21 items, and its purpose is to measure the severity of depression from non-depression to severe depression. Each item is scored on a Likert scale from 0 to 3. To obtain the total score of the questionnaire, the total score of all questions is calculated, ranging from 0 to 63. Based on these scores, 0–10 (no depression), 11–16 (mild depression), 16–20 (needs to consult a psychologist or psychiatrist), 21–30 (relatively depressed), 31–40 (severe depression), and 40 above (excessive depression) were defined.[14]

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1398.917), and this trial was registered in the Iranian clinical trial system with the patent number IRCT20200823048493N1. The survey was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In this study, no financial costs were imposed on the patients, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantity values and frequency (percentage) for qualitative values. Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were applied to test for the data normality. Homogeneity of variance was assessed by the Leven test. Independent t-test and Chi-square test were used to compare the means of quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively. P values of 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patients’ demographic features

In the current study, 66 subjects, by considering the inclusion criteria, were categorized into two groups. At the end of the study, six patients were excluded from the study due to diabetes, hypertension, and death caused by COVID-19. Finally, the data from 60 patients were analyzed in two equal groups [Figure 1]. The mean ages of patients in the control and intervention groups were 38.03 ± 9.33 and 38.80 ± 8.91, respectively. No statistically significant difference was found between the ages of patients in the two groups (P = 0.74). The intervention group had fewer females than the control group (60% vs. 70%); there was no significant difference in sex distribution between the two groups (P = 0.41). Based on the analysis, marital status did not differ between the two collection groups (P = 0.51). It was observed that the level of education, economic income, and place of residence were not considerably different between the intervention and control groups (P > 0.05). In terms of the duration of the disease, no statistically significant difference was observed in the two groups (P = 0.5). Detailed demographic characteristics of the studied patients are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studied participants

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics between the two groups

| Variables | Groups | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intervention group (n=30) | Control group (n=30) | ||

| Age, year (Mean±SD) | 38.03±9.33 | 38.80±8.91 | 0.74 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 18 (60) | 21 (70) | 0.41 |

| Male | 12 (40) | 9 (30) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 21 (70) | 24 (80) | 0.51 |

| Single | 9 (30) | 6 (20) | |

| Level of Education, n (%) | |||

| Primary | 6 (20) | 6 (20) | 0.51 |

| Middle school | 6 (20) | 11 (36.7) | |

| High school | 12 (40) | 9 (30) | |

| University | 6 (20) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Economic Income, n (%) | |||

| Low | 9 (30) | 10 (34.5) | 0.91 |

| Average | 16 (53.3) | 15 (51.7) | |

| Good | 5 (16.7) | 4 (13.8) | |

| Place of residence, n (%) | |||

| Urban | 22 (73.3) | 25 (83.30) | 0.34 |

| Rural | 8 (26.7) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Duration of the disease | 5.33±3.12 | 4.86±3.26 | 0.5 |

Beck scores in both groups of the study

According to Table 2, after the fourth week, the mean Beck scores of patients in the intervention group were statistically considerably lower than those in the control group (P = 0.02). Also, the mean Beck scores at the end of the intervention decreased in the magnesium group compared with the placebo group; this difference was significant statistically (P = 0.001). More details are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparing the mean of Beck score between the two groups

| Time | Beck score | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intervention group (n=30) | Control group (n=30) | ||

| Week 0 | 36.10±4.54 | 36.13±4.73 | 0.97 |

| Week 2 | 31.83±4.08 | 32.50±4.76 | 0.56 |

| Week 4 | 23.73±4.09 | 26.06±3.87 | 0.02* |

| Week 6 | 16.86±2.37 | 19.36±2.70 | 0.001* |

As Figure 2 shows, the mean Beck score of patients in each evaluation stage was statistically lower than the previous stage in both groups, but this decrease was statistically markedly higher in patients in the intervention group after the second week. In other words, adding magnesium supplementation to the patients in the intervention group caused this decrease to be statistically significant and enabled further improvement.

Figure 2.

Comparison of changes in Beck scores of the two groups during different weeks of study

Of note, no side effects related to magnesium supplementation were observed in any of the studied patients.

Discussion

Depression is becoming more prevalent. Over 30% of people with depressive symptoms, on the other hand, do not obtain treatment.[15,16] Cost and side effects of antidepressant drugs, fear of addiction and dependence, and stigma connected with mental health therapy are all reasons why patients may not seek treatment.[17,18] Oral magnesium treatment, possibly through dietary supplements, may appeal to many patients more than other currently accessible options. Magnesium supplementation helps to alleviate depressive symptoms.[10,19]

Our results indicated that the mean depression scores of patients in two groups (before intervention and 2 weeks after intervention) were not significantly different. However, in the fourth and sixth weeks of post-intervention, this score was statistically lower compared to the control group. In addition, depression scores in both groups during the second, fourth, and sixth weeks decreased significantly in comparison to the first week of the study; however, this decrease was more considerable in patients who received Mg supplements along with antidepressants rather than the group who were under antidepressants only. Therefore, these findings indicate that although taking SSRIs alone could significantly reduce the depression score, adding magnesium supplements to this treatment significantly reduced and improved the depression score.

Although several studies have shown that magnesium supplements can alleviate depression’s complications and symptoms, some others did not find them useful. In accordance with our findings, Tarleton et al.,[19] in a randomized clinical trial of adults with mild to moderate levels of depression, found that consuming 248 mg/day of magnesium chloride for 6 weeks can reduce the symptoms up to six points. They also mentioned that patients treated with antidepressants would benefit more if they took magnesium supplements. Rajizadeh et al.[14] evaluated the effect of magnesium on depression in a double-blind clinical trial. In this study, the intervention group received 500 mg/day of magnesium for eight consecutive days, and placebo was prescribed for the control group. Although no antidepressant was utilized in this study, magnesium supplements improved not only the depression status but also the status of magnesium storage in the body. Of note, this study has some differences from ours. No SSRI was prescribed in either the intervention or control group, and the dosage of magnesium supplement was twice as much as that in our study. Furthermore, Eby et al.[20] reported that magnesium supplements (125–300 mg) led to rapid improvement in three patients diagnosed with major depression. Similar to our study, the serum magnesium level was not evaluated. Our regimen treatment significantly improved the patients’ Beck score, reflecting that our treatment option might be helpful in patients diagnosed with MDD. Afsharfar et al.[21] in a double-blind, randomized clinical trial, reported that 500 mg/day of magnesium supplementation for 8 weeks improved the Beck test scores and serum magnesium level.

On the other hand, some studies reported contradictory findings. Edalati Fard et al.[22] did not find any correlation between magnesium supplements and postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms in a triple-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial.

This study faced various limitations, including a lack of objective evaluation of depressive symptoms. In this study, only a self-report questionnaire was used to assess the symptoms of depression in patients. Also, different SSRIs were used by patients, and the effect of adding magnesium supplementation to different drugs was not studied separately; Therefore, it is suggested that for less bias in future studies, the effect of magnesium supplementation with various SSRIs on the improvement of depressive symptoms should be determined.

Conclusion

Although taking SSRI antidepressants alone can reduce depressive symptoms, adding Mg supplements to the treatment regimen for at least 6 weeks can significantly improve MDD symptoms. Therefore, Mg supplements can be considered as a treatment option along with the standard regimen, although more investigations are required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all patients who participated in this study. In addition, this study was financially supported by the Ahwaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Depression W. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Other common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trivedi MH. Major depressive disorder in primary care: Strategies for identification. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81 doi: 10.4088/JCP.UT17042BR1C. UT17042BR1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuckerman H, Pan Z, Park C, Brietzke E, Musial N, Shariq AS, et al. Recognition and treatment of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. Frontiers Psychiatry. 2018;9:655. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho AF, Miskowiak KK, Hyphantis TN, Kohler CA, Alves GS, Bortolato B, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in depression–pathophysiology and novel targets. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13:1819–35. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141130203627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter EC. Understanding and treating depersonalisation disorder. In: Kennerley H, Kennedy F, Pearson D, editors. Cognitive Behavioural Approaches to the Understanding and Treatment of Disssociation. London: Routledge Press; 2013. pp. 160–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranjbar E, Kasaei MS, Mohammad-Shirazi M, Nasrollahzadeh J, Rashidkhani B, Shams J, et al. Effects of zinc supplementation in patients with major depression: A randomized clinical trial. Iran J Psychiatry. 2013;8:73–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serefko A, Szopa A, Wlaź P, Nowak G, Radziwoń-Zaleska M, Skalski M, et al. Magnesium in depression. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65:547–54. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Um P, Dickerman BA, Liu J. Zinc, magnesium, selenium and depression: A review of the evidence, potential mechanisms and implications. Nutrients. 2018;10:584. doi: 10.3390/nu10050584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin KJ, González KA, Slatopolsky E. Clinical consequences and management of hypomagnesemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2291–5. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkland AE, Sarlo GL, Holton KF. The role of magnesium in neurological disorders. Nutrients. 2018;10:730. doi: 10.3390/nu10060730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikseresht S, Sahabeh E, Hamid Reza SR, Reza ZM, Morteza KS, Fatemeh NZ. The role of nitrergic system in antidepressant effects of acute administration of zinc, magnesium and thiamine on progesterone induced postpartum depression in mice. Tehran Univ Med J. 2010;68:261–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gröber U, Schmidt J, Kisters K. Magnesium in prevention and therapy. Nutrients. 2015;7:8199–226. doi: 10.3390/nu7095388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosanoff A, Weaver CM, Rude RK. Suboptimal magnesium status in the United States: Are the health consequences underestimated? Nutr Rev. 2012;70:153–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajizadeh A, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Yassini-Ardakani M, Dehghani A. Effect of magnesium supplementation on depression status in depressed patients with magnesium deficiency: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition. 2017;35:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorm AF, Patten SB, Brugha TS, Mojtabai R. Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders?Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:90–9. doi: 10.1002/wps.20388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittayanukorn S, Qian J, Hansen RA. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and predictors of treatment among US adults from 2005 to 2010. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:330–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutting PA, Rost K, Dickinson M, Werner JJ, Dickinson P, Smith JL, et al. Barriers to initiating depression treatment in primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:103–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng CWM, How CH, Ng YP. Managing depression in primary care. Singapore Med J. 2017;58:459–66. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2017080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarleton EK, Littenberg B, MacLean CD, Kennedy AG, Daley C. Role of magnesium supplementation in the treatment of depression: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eby GA, Eby KL. Rapid recovery from major depression using magnesium treatment. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:362–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afsharfar M, Shahraki M, Mostafa Habibi-Khorassani S. The effects of magnesium supplementation on serum level of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and depression status in patients with depression. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;42:381–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fard FE, Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S, Farshbaf-Khalili A, Javadzadeh Y, Asgharian H. Effects of zinc and magnesium supplements on postpartum depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Women Health. 2017;57:1115–28. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2016.1235074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]