ABSTRACT

Introduction:

India accounts for approximately half of the worldwide snakebite deaths. It is often a neglected public health problem and particularly in Jharkhand region where medical facilities are limited. Epidemiological and clinical profile-related studies are scarce. The present study aims to assess the epidemiological profile and clinical features of snakebites encountered in a tertiary-care teaching hospital at Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India.

Aims and Objective:

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical profile, outcome and epidemiological factors of snakebite cases, admitted to a tertiary care hospital in Jamshedpur.

Material and Methods:

This was a retrospective study from 2014 to 2021 wherein a total of 427 snakebite patients were admitted and had received treatment for snakebite at a tertiary-care teaching hospital at Jamshedpur, Jharkhand. All patients who reported with a history of snakebite were included in this study. The demographic and clinical details of each case were obtained and analysed.

Result:

A total of 427 snakebite cases were admitted to the hospital during the study period. The victims were predominantly males. Majority of the bite cases encountered were from rural areas and were in the second quarter of the year. The site of the bite was largely on the lower limb and the upper limb had fewer bites. The Glasgow Coma Scale was normal in those who presented early. Acute kidney injury, neutrophilic leucocytosis and deranged liver enzymes were associated with bad prognosis. Timely intervention with anti-snake venom offered good result.

Conclusion:

We had more male patients (69.55%), belonging to rural areas (67.91%), more bites in lower limbs and more cases in the second quarter of the year. Mortality rate was 0.7%.

Keywords: Anti snake venom (ASV), clinical features, epidemiology, snakebite

Introduction

Snakebite is a neglected public health issue throughout the world, especially in a country like India and in particular the state of Jharkhand where there is paucity of data related to snakebite and its related complications. Caduceus, the symbol of two snakes coiled around a rod with wings on the top, symbolizes medicine in general.[1]

All venomous species of the world are grouped in five families[2] : Colubridae, Elapidae, Atractaspididae, Viperidae and Hydrophidae.

World Health Organization (WHO) classifies commonly encountered medically important snakes in three categories found in South Eastern Asia.[3]

Category 1: Very commonly causes death or may lead to serious disabilities and complications.

Category 2: Bites may be rare but may cause serious effects (death or local necrosis).

Category 3: Bites are common but serious effects are very less.

As per the WHO, approximately 5.4 million people are bitten each year with up to 2.7 million envenoming. Around 81,000–138,000 people die each year because of snakebites, and around three times as many amputations and other permanent disabilities are caused by snakebites annually.[4]

In India the annual snakebite mortality ranges from 1300 to 50,000 and such variations can be attributed to inadequate/under-reporting.[5,6] Hence, India has been nicknamed ‘Snakebite capital of the world’.[7]

To corroborate the facts regarding snakebite cases, the epidemiological aspects and clinical profile, this study was planned, which would help to understand the clinical, therapeutic process and also adopt adequate preventive and control measures.

Aims and Objectives

The aim of this study was to review the demographic, clinical and laboratory findings in patients admitted with snakebite and to study the epidemiology of snakebite poisoning in and around East Singbhum, Jharkhand, incidence among various sex and age groups, the incidence, time and site of bite, seasonal variations, immediate manifestations, treatment received and the final outcome.

Materials and Methods

Setting and study design

This was a retrospective study of 427 patients admitted in a tertiary-care teaching hospital at Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, over a period of 7 years (2014–2021) with a history of snakebite. All patients who were above the age of 18 years age and of either sex, and who reported with alleged history of snakebite, were included in our study. Ethics committe approval has been taken, Approval date 15th February 2022.

Data collection

The study group included 427 patients who reported to the hospital with alleged history of snakebite and were followed up till the final outcome. Patients with history of bite other than snakebites were carefully excluded. At the time of admission preliminary data of each case, such as age, domicile and other demographic details were entered in a proforma. Further details such as the time and site of bite, the symptoms and signs noticed on hospital admission, seasonal variation, immediate manifestations, hospital stay, treatment received and final outcome were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as frequency percentages. Descriptive analysis of the collected data was done and the clinical and demographical profile of the subjects with snakebite was compared.

Results

Demographic details

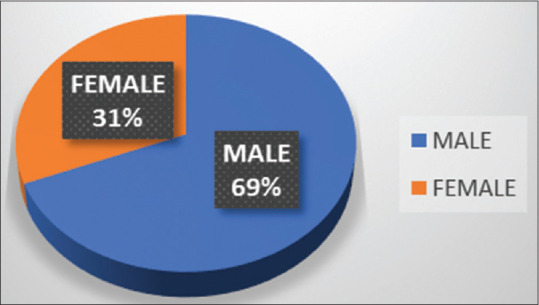

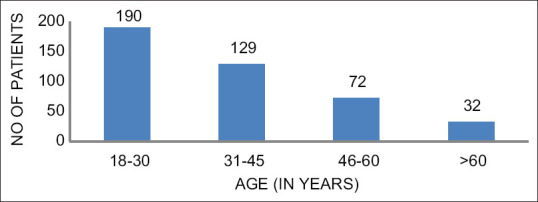

A total of 427 cases of snakebite cases were admitted during our study. Gender wise, male comprised 297 cases (69.55%) while female constituted 130 cases (30.44%) [Figure 1]. Age-wise distribution revealed that maximum number of cases was seen in the age group of 18–30 years (n = 190; 44.49%) with mean age 33.53 years and standard deviation being 15.8 years. In the age group of 31–45 years, the number of cases were n = 129, that is 30.21%, whereas in the age group of 46–60 years, number of cases were n = 72, that is 16.86%. Amongst the age group of more than 60 years, the number of cases were n = 32, that is 7.4% [Figure 2, Table 1].

Figure 1.

Graph depicting gender-wise distribution in snakebite cases

Figure 2.

Bar graph depicting age distribution of snakebite case

Table 1.

Table depicting demographic and clinical distribution in snakebite cases

| Variables | Category | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18-30 | 190 | 44.49 |

| 31-45 | 129 | 30.21 | |

| 46-60 | 72 | 16.86 | |

| >60 | 32 | 7.4 | |

| Site of bite | Upper limb | 95 | 22.24 |

| lower limb, back | 283 | 66.27 | |

| Non-specific | 49 | 11.47 | |

| Symptoms | Systemic | 81 | 18.96 |

| Local + systemic | 84 | 19.67 | |

| No symptoms | 262 | 61.35 | |

| Time | Day | 176 | 41.21 |

| Night | 251 | 58.78 | |

| Glasgow coma scale | 15 | 329 | 77.04 |

| >7 | 79 | 18.50 | |

| <7 | 19 | 4.44 |

Clinical presentation

A total of 262 patients (61.35%) had no clinical signs and symptoms. Eighty-one patients developed local symptoms initially and gradually developed systemic manifestations in the course of treatment. Eighty-four patients developed local manifestations only.

Alleged snake species

Incidence of neurotoxic bites was more as compared to hematotoxic ones.

Time of presentation

A total of 314 (73.53%) patients presented within 6 h and 113 (26.46%) patients presented after 6 h to our emergency department [Table 2].

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of parameters

| Category | Male (%) | Female (%) | Chi-square | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 35 | 28 | 1.7818 | 0.182 |

| Rural | 65 | 72 | ||

| Poisonous | 57 | 26 | 0.2543 | 0.614 |

| Non-poisonous | 76 | 74 | ||

| <6 h | 80 | 66 | 7.5349 | 0.0061* |

| >6 h | 20 | 34 |

* indicates statistical significance

Site of bite

The most common site of bite was the lower limbs and the back region, that is in 283 (66.27%) victims, followed by the upper limbs, that is in 95 (22.24%) patients. Others, that is 49 (11.47%) victims, sustained bite in the remaining areas of the body.

Blood investigations

Routine investigation was asked for in all the cases. A total of 254 patients showed neutrophils more than 60%. Liver function test revealed increased bilirubin (more than 2 mg/dl) in 18 patients. Forty-two patients had increased aspartate transaminase (more than 45 IU/l) and 40 patients had increased alkaline phosphatase but alanine transaminase levels were normal. Nine patients had creatinine level more than 1.5 mg/dl and four patients had urea levels more than 40 mg/dl.

Anti-snake venom treatment

Based on the clinical features, sign and symptoms, 165 (38.64%) patients were treated with anti-snake venom (ASV) and the remaining 262 patients were managed on supportive and conservative therapy. In total, 424 patients survived (99.29%). Three patients (0.7%) died during treatment due to secondary complications. Thirteen patients needed intensive care support. Two patients had cardiac arrest at emergency, revived and sent to critical care. One patient died of respiratory failure and two patients died secondary to multi-organ failure.

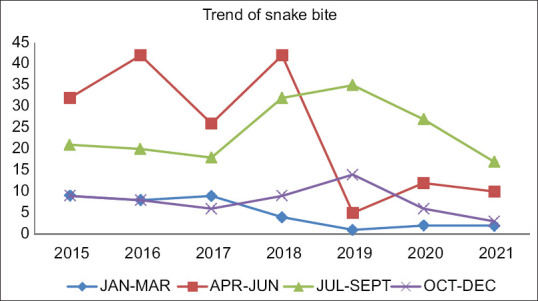

Period of bite

Most bites occurred between April and September in all 7 years and were more in 2018 [Table 3 and Figure 3].

Table 3.

Period-wise distribution of snakebite cases

| Period | 2015 | Percentages | 2016 | Percentages | 2017 | Percentages | 2018 | Percentages | 2019 | Percentages | 2020 | Percentages | 2021 | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan-Mar | 9 | 13% | 8 | 10% | 9 | 15% | 4 | 5% | 1 | 2% | 2 | 4% | 2 | 6% |

| Apr-Jun | 32 | 45% | 42 | 54% | 26 | 44% | 42 | 48% | 5 | 9% | 12 | 26% | 10 | 31% |

| Jul-Sept | 21 | 30% | 20 | 26% | 18 | 31% | 32 | 37% | 35 | 64% | 27 | 60% | 17 | 53% |

| Oct-Dec | 9 | 13% | 8 | 10% | 6 | 10% | 9 | 10% | 14 | 25% | 6 | 13% | 3 | 9% |

| Total | 71 | 78 | 59 | 87 | 55 | 45 | 32 |

Figure 3.

Period-wise distribution of snakebite cases

Discussion

The present study highlights certain facts:

-

(1)

Age and sex distribution

The majority of the victims belonged to 18–30 years of age (n = 190; 44.49%) and were male (297 cases: 69.55%). This attributes to the fact that younger age group males are more active members and are found more indulgent in outdoor activities. This study is in comparison to other studies done by various authors.[8]

-

(2)

Rural–urban distribution

Rural population constituted the chunk of casualties, that is 290 patients (67.91%), while 138 (32.31%) patients were from urban area. This corroborates with a similar study done in the North Indian population.[9]

-

(3)

Identification of snake

Based on the fact that envenoming occurs in about one in every four snakebites, between 1.2 million and 5.5 million snakebites could occur annually.[10] Based on the history and clinical presentation, the cases were mostly neurotoxic.[11] Patients presented with mostly bilateral ptosis, quadriparesis and bulbar palsy.

-

(4)

Time interval between bite and admission to the hospital

Nearly 73.53% of the patients reported to the hospital within 6 h of the bite. Early admission and prompt action had a better outcome. Time interval between bite and admission to the hospital was one of the key parameters in patients developing complications such as acute kidney injury (AKI) as evident from various other studies. Those who presented late sometime even if they survived may have long-lasting complications or disabilities. Mode of transport and location of hospital were the other limiting factors.[11,12]

-

(5)

Site of bite

Lower extremity was the most common site (66.27%) for snakebite and has been observed in various similar other studies. One reason that can be attributed to this is accidental stepping on the snake. Foot and toe were the most affected regions in the right lower limb followed by right hand and fingers in right upper limb [Table 4].

-

(6)

Lab parameters

Majority of the patients had leucocytosis, which was initially observed in most bite. The incidence of AKI was very low (n = 9; 3.3%). Acute renal failure is mostly observed in viper bite and less in sea snakebite and colubridae.[13-15] Also, studies have suggested that the incidence of AKI was less in patients who present early in the hospital, as compared to those reaching hospital late.[16,17] In our study, the incidence of AKI was less, which can be attributed to the fact that nearly 70% of the patients reported to the hospital were within 6 h of bite. Also, majority of the bites were neurotoxic and hence the kidneys were spared. One patient had rising creatinine levels with urine output around 350 ml; hemodialysis was planned with nephrology reference but patient’s relatives took discharge against medical advice. Chest radiographs were normal in most of the cases wherever needed, except in three patients who died with multi-organ failure. Electrocardiography also revealed sinus tachycardia in most of the cases. Prothrombin time remained normal in most of our patients.

ASV treatment and outcome: High survival rate (99.29%) was encountered with prompt treatment and administration of ASV. Most of the cases were successfully managed with low dose of ASV and prophylactic pheniramine and hydrocortisone administration.

Table 4.

Segregation of snakebites based on the site of bite

| Site of bite | Percentage | Number of cases |

|---|---|---|

| Lower limb (LL) | ||

| Left foot + toe | 18 | 99 |

| Right foot + toe | 26 | 144 |

| Rest right LL | 3 | 18 |

| Rest left LL | 1 | 6 |

| 48 | 267 | |

| Upper limb (UL) | ||

| Right hand and finger | 13 | 72 |

| Left hand and finger | 4 | 22 |

| Rest right UL | 4 | 22 |

| Rest left UL | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | 116 | |

| 383 | ||

| Unknown | 8 | 44 |

In our study, when rural and urban and poisonous and non-poisonous bites were sex-matched, results were not statistically significant but presentation of a bite within 6 h and after 6 h were statistically significant [Table 2], which means that males presented earlier (within 6 h) while females presented late. Most bites occurred between April and September in all 7 years and maximum in 2018.

In a study by Suraweera et al.,[18] snakebites were more common in males (59%), at ages 30–69 years (57%), from June to September (48%), and occurring outdoors (64%). These results match the relevant results for the Million Death Study (MDS). However, MDS snakebite deaths were equal in males and females. The leg was the dominant site of bite (77%), and the time of reported bite was throughout the day. Of the treated cases, nearly two-thirds (66%) were seen within 1–6 h, with the remainder seen after 6 h and a crude case-fatality rate of 3.2% for in-hospital cases.

In a study by Gajbhiye et al.,[19] venomous snakebites were 76% and non-venomous snakebites were 24%. Snakebites were more in males (52.4%) than females (47.6%). Most of the snakebites (66%) were in the age group of 18–45 years. Highest snakebites were in monsoon (58%). Lower extremities were the most commonly affected (63%). Neurotoxic and vasculotoxic envenomation were reported in 19% and 27% of snakebite cases, respectively. ASV was administered at an average dose of 7.5 ± 0.63 vials (range 2–40, median 6).

In a study by Chaaithanya et al.,[20] the application of a harmful method (Tourniquet) was practised by the tribal community. They preferred herbal medicines and visited the traditional faith healers before consulting government health facility. The knowledge to identify venomous snakebites and anti-venom was significantly higher amongst nurses and accredited social health activists than auxiliary nurse midwives and multi-purpose workers (P < 0.05). None of the traditional faith healers; but nearly 60% of snake rescuers were aware of anti-venom. Fifty per cent of the medical officers did not have correct knowledge about the Krait bite symptoms, and renal complications due to the Russell viper bite.

In our study, mortality rate observed was 0.7% and average length of stay was 2.55 days.

Conclusion

The WHO’s call to halve global snakebite deaths by 2030 will require substantial progress in India.[19] Snakebite is an important cause of accidental death in modern India, and its public health importance has been systematically underestimated. Reporting of envenomation is generally poor in our country with lack of awareness amongst health workers and general masses. Majority of cases are encountered in rural areas and are initially managed by the traditional healers, and if the situation worsens, then it is taken up by primary health care. This practice overall leads to underestimation of various other epidemiological parameters like incidence, mortality, morbidity, disability and so on.

Majority of the cases encountered in the region are amongst young males and cases are frequently encountered during the monsoon season. Nocturnal habitat of snakes corresponds to maximum bites during the night and lower limbs are the more frequent sites. Forty-two patients had mild transamnitis and nine patients had mildly raised creatinine levels. Neurotoxic snakebites were more common than vasculotoxic bites.

Protective footwear, proper illumination in dark areas and rodent control are effective means to prevent snakebite.

First aid, immobilization of bite area and early transportation to a tertiary care centre are the most effective methods in combating such situations. Differentiating venomous bite and dry bites is one area of importance and often requires clinical acumen. Early admission of the cases to tertiary centre, clinical diagnosis, lab investigations and treatment with ASV is the key to the overall recovery and prognosis of cases. ASV is the only effective specific treatment of envenomation.[20]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Prakash M, Johnny JC. Things you don't learn in medical school:Caduceus. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7((Suppl 1)):S49–50. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.155794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hati AK, Mandal M, De MK, Mukherjee H, Hati RN. Epidemiology of snakebite in the district of Burdwan, West Bengal. J Indian Med Assoc. 1992;90:145–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed SM, Ahmed M, Nadeem A, Mahajan J, Choudhary A, Pal J. Emergency treatment of a snake bite:Pearls from literature. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2018;1:97–105. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.43190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggrawal A. 1st ed. Avichal Publishing Company; New Delhi: 2016. Textbook of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology; p. 639. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World health organization (WHO). Annex 5. Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964. WHO Technical Report Series. 2017;96:197–388. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Snakebite envenoming WHO. [[Last accessed on 2019 Nov 08]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/snakebite-envenoming .

- 7.Mohapatra B, Warrell DA, Suraweera W, Bhatia P, Dhingra N, Jotkar RM, et al. Snakebite mortality in India:A nationally representative mortality survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chugh KS, Pal Y, Chakravarty RN, Datta BN, Mehta R, Sakhuja V, et al. Acute renal failure following poisonous snake bite. Am J Kidney Dis. 1984;4:30–8. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(84)80023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerjee RN. Poisonous snakes in India, their venom, symptomatology and treatment of envenomation. In: Ahuja MMS, editor. Progress in Clinical Medicine in India. 1st ed. New Delhi: Arnold Heinman Publishers; 1978. pp. 86–179. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N, Gunawardena NK, Pathmeswaran A, Premaratna R, et al. The global burden of snakebite:A literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalantri S, Singh A, Joshi R, Malamba S, Ho C, Ezoua J, et al. Clinical predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with snake bite:A retrospective study from a rural hospital in central India. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:22–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitra S, Agarwal A, Shubhankar BU, Masih S, Krothapalli V, Lee BM, et al. Clinico-epidemiological profile of snake bites over 6-year period from a rural secondary care centre of northern India:A descriptive study. Toxicol Int. 2015;22:77–82. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.172263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anjum A, Husain M, Hanif SA, Ali SM, Beg M, Sardha M. Epidemiological profile of snake bite at tertiary care hospital, North India. J Forensic Res. 2012;3:146. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawai Y, Honma M. Snake bites in India. The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, England OX5 1Gb:Pergamon-Elsevier Science Ltd. In Toxicon. 1975;13:120–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mittal BV. Acute renal failure following poisonous snake bite. J Postgrad Med. 1994;40:123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varuganam T, Panaboke RG. Bilateral cortical necrosis of the kidneys following snakebite. Postgrad Med J. 1970;46:449–51. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.46.537.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Athappan G, Balaji MV, Navaneethan U, Thirumalikolundusubramaniam P. Acute renal failure in snake envenomation:A large prospective study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2008;19:404–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suraweera W, Warrell D, Whitaker R, Menon G, Rodrigues R, Fu SH, et al. Trends in snakebite deaths in India from 2000 to 2019 in a nationally representative mortality study. Elife. 2020;9:e54076. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gajbhiye R, Khan S, Kokate P, Mashal I, Kharat S, Bodade S, et al. Incidence &management practices of snakebite:A retrospective study at Sub-District Hospital, Dahanu, Maharashtra, India. Indian J Med Res. 2019;150:412–6. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1148_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaaithanya IK, Abnave D, Bawaskar H, Pachalkar U, Tarukar S, Salvi N, et al. Perceptions, awareness on snakebite envenoming among the tribal community and health care providers of Dahanu block, Palghar District in Maharashtra, India. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]