Gershon and Fridman (1) argue that when group members face a trade-off between net-negative options—either harming the in-group or benefiting the out-group—they rather choose to harm the in-group to avoid even minimal support for the out-group. Five experiments provide evidence for this claim: Participants from different groups (e.g., Democrats vs. Republicans) predominantly chose to reduce donations to organizations that support the in-group’s values rather than to increase donations to organizations that support the out-group’s values (e.g., pro-choice vs. pro-life).

We are not questioning these findings but rather their generalizability. All five studies involved donations to organizations. In contrast, in previous studies investigating distributional preferences in intergroup settings (2–6) as well as in many real-world interactions, decisions have direct consequences for individual in-group and out-group members. There are several reasons why individuals may be less willing to support out-group organizations than individual out-group members. First, attitudes toward organizations are typically more polarized than attitudes toward individual members of these organizations (7). Second, donations to an organization likely have stronger signaling effects (e.g., regarding reputation or self-image) than donations to individuals.

We conducted a preregistered replication study in a setting where allocations affect individual in-group and out-group members, rather than organizations. N = 1,048 US participants (group context: Democrats and Republicans) chose between benefiting an in-group member (+$1) and harming an out-group member (−$1) in the win-win condition (n = 350) or between harming an in-group member (−$1) and benefiting an out-group member (+$1) in the lose-lose condition (n = 698).

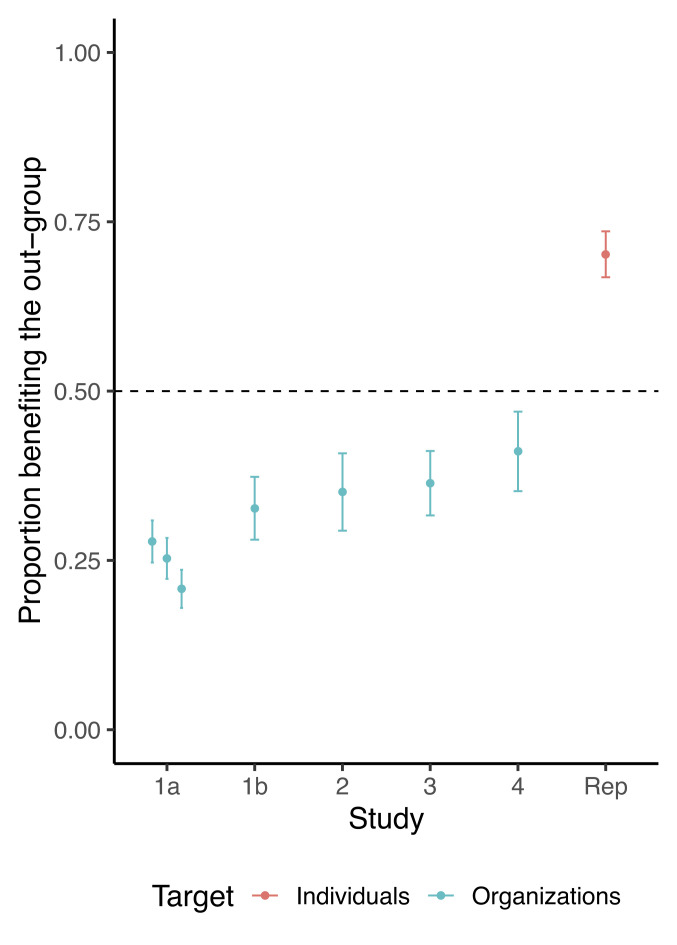

In the win-win condition, the vast majority of participants (91.7%) benefited an in-group member rather than choosing to harm an out-group member, (1) = 241.95 (against 50%), P < 0.001, 95% CI = [88.2, 94.3]. However, in contrast to Gershon and Fridman’s findings and in line with our hypothesis, in the lose-lose condition, most individuals (70.1%) chose to benefit an out-group member rather than to harm an in-group member, (1) = 113.12, P < 0.001, 95% CI = [66.6%, 73.5%]. This proportion was significantly larger than the largest corresponding proportion reported by Gershon and Fridman (study 4, 41.1%), (1) = 68.76, P < 0.001 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of participants benefiting the out-group in the lose-lose condition. Values for studies 1 to 4 are from Gershon and Fridman (1) with in-group and out-group organizations as targets, Rep indicates our replication study with individual in-group and out-group members as targets. Dots show mean values; error bars represent 95% CIs.

Gershon and Fridman conclude that “individuals are so averse to supporting opposing groups that they prefer equivalent or greater harm to their own group instead” (p. 1). We show that this claim does not hold for individual group members: Most people would rather benefit an out-group member than choose to harm an in-group member. We consider the inconsistency between preferences for harming in-group organizations vs. individual in-group members a fruitful avenue for future research.

Ethics and Open Science Statement

This research obtained ethical clearance from the review board of the Department of Occupational, Economic, and Social Psychology (#2023_W_003A). All participants provided informed consent prior to data collection. The study was preregistered at https://osf.io/rc6ab. Study materials, data, and code of the reported and further analyses are available at https://osf.io/h43mc/.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

M.K., R.B., Q.X., and S.C. designed research; M.K., R.B., Q.X., and S.C. performed research; S.C. analyzed data; and M.K., R.B., Q.X., and S.C. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- 1.Gershon R., Fridman A., Individuals prefer to harm their own group rather than help an opposing group. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2215633119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halevy N., Bornstein G., Sagiv L., “In-group love” and “out-group hate” as motives for individual participation in intergroup conflict: A new game paradigm: Research article. Psychol. Sci. 19, 405–411 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halevy N., Weisel O., Bornstein G., “In-Group Love” and “Out-Group Hate” in repeated interaction between groups. J. Behav. Decis. Making 25, 188–195 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisel O., Böhm R., “Ingroup love” and “outgroup hate” in intergroup conflict between natural groups. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 60, 110–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Böhm R., Halevy N., Kugler T., The power of defaults in intergroup conflict. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 168, 104105 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aaldering H., Böhm R., Parochial vs. universal cooperation: Introducing a novel economic game of within- and between-group interaction. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 36–45 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Druckman J. N., Levendusky M. S., What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opin. Q. 83, 114–122 (2019). [Google Scholar]