Significance

Using a murine papillomavirus as a model for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, this report reveals that two host factors, estrogen and stress keratin 17, cooperatively support viral persistence and disease progression in papillomavirus-induced cervicovaginal lesions at least in part by modulating distinct populations of immune cells. This study provides insight into underlying mechanisms of papillomavirus-induced cervical carcinogenesis and reveals two different host persistence factors that may potentially serve as new or complementary therapeutic targets in the treatment of cervical neoplastic disease and cancer.

Keywords: papillomavirus, estrogen, cervical cancer

Abstract

A murine papillomavirus, MmuPV1, infects both cutaneous and mucosal epithelia of laboratory mice and can be used to model high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV-associated disease. We have shown that estrogen exacerbates papillomavirus-induced cervical disease in HPV-transgenic mice. We have also previously identified stress keratin 17 (K17) as a host factor that supports MmuPV1-induced cutaneous disease. Here, we sought to test the role of estrogen and K17 in MmuPV1 infection and associated disease in the female reproductive tract. We experimentally infected wild-type and K17 knockout (K17KO) mice with MmuPV1 in the female reproductive tract in the presence or absence of exogenous estrogen for 6 mon. We observed that a significantly higher percentage of K17KO mice cleared the virus as opposed to wild-type mice. In estrogen-treated wild-type mice, the MmuPV1 viral copy number was significantly higher compared to untreated mice by as early as 2 wk postinfection, suggesting that estrogen may help facilitate MmuPV1 infection and/or establishment. Consistent with this, viral clearance was not observed in either wild-type or K17KO mice when treated with estrogen. Furthermore, neoplastic disease progression and cervical carcinogenesis were supported by the presence of K17 and exacerbated by estrogen treatment. Subsequent analyses indicated that estrogen treatment induces a systemic immunosuppressive state in MmuPV1-infected animals and that both estrogen and K17 modulate the local intratumoral immune microenvironment within MmuPV1-induced neoplastic lesions. Collectively, these findings suggest that estrogen and K17 act at multiple stages of papillomavirus-induced disease at least in part via immunomodulatory mechanisms.

Nearly all human cervical cancers are associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) (1). A murine papillomavirus, MmuPV1, was discovered a decade ago (2) and is revolutionizing our ability to model HPV-associated cutaneous and mucosal disease in laboratory mice (3). MmuPV1 infection-based models are facilitating long-sought studies of host factors and host immune responses that contribute to papillomavirus infection and virus-induced disease progression (4–16). One host factor studied in the context of cervical carcinogenesis is the female hormone estrogen. In HPV16 transgenic mice, we and others have shown that estrogen is required for the onset, maintenance, and progression of papillomavirus-induced neoplastic disease (17–20) and treatment with estrogen receptor α (ERα) inhibitors promotes regression of cervical cancer (21). We have also found that estrogen treatment exacerbates the incidence and severity of disease in MmuPV1 cervicovaginal infection models (7, 16).

Estrogen is a well-established risk factor for certain types of human cancer, such as breast cancer. Upon binding to the hormone ligand, estrogen receptors translocate to the nucleus and drive transcription of genes that promote cell cycle and cell proliferation (22–27). Estrogen can also induce DNA damage and suppress DNA repair pathways to drive cellular transformation in breast cancer (28–30). In vitro, estrogen can induce HPV oncogene expression and suppress apoptosis in HPV-infected epithelial cells (31–34). In other studies, in contrast, estrogen can inhibit HPV oncogene expression and induce apoptosis (35, 36). There is now accumulating evidence supporting nonautonomous effects of estrogen on immune cells and the tumor microenvironment (37). However, the exact molecular mechanisms by which estrogen contributes to cervical carcinogenesis are less clear. In human cervical cancers, ERα expression is often lost in epithelial cells yet is maintained in the underlying stroma (38). Using genetically engineered mice to generate tissue-specific deletion of the Esr1 gene encoding ERα, Chung and colleagues have established that stromal ERα expression in the cervix is both required and sufficient for HPV-mediated disease in HPV16 transgenic mice (39, 40). We previously reported that estrogen induces significant gene expression changes in the underlying stroma, including an upregulation in the expression of inflammatory chemokines critical for neutrophil recruitment in estrogen-induced disease sites in HPV transgenic mice (41). Estrogen can induce myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) expansion in murine cancer models independently of tumor cell ERα signaling but dependent on immune cell functions (42–46). MDSCs mainly include immature neutrophils that act through suppressing the function of antitumor T cells in cancers (47–49). Considering this collection of evidence, we hypothesize that estrogen supports persistent viral infection and exacerbates papillomavirus-induced cervical disease at least in part through immune suppression.

We have previously identified stress keratin 17 (K17) as a host factor that mediates local immunosuppression in papillomavirus-induced cutaneous disease (11). K17 expression is often absent in normal healthy interfollicular epithelial tissues and is restricted to hair follicles and sebaceous glands (50). Its expression can be induced by wounding or an inflammatory microenvironment (51–53). We have shown that MmuPV1 infection induces K17 expression in the skin, which is required to prevent T cell infiltration in MmuPV1-induced papillomas by downregulating expression of chemokines that recruit CXCR3+ T cells (11). In this report, we sought to test whether K17 expression and/or estrogen are required for persistent MmuPV1 mucosal infection and whether they cooperate to exacerbate cervicovaginal disease progression through suppression of the host immune response.

Results

K17 and Estrogen Cooperate to Promote Viral Persistence and Disease Progression in MmuPV1-Infected Reproductive Tract Lesions.

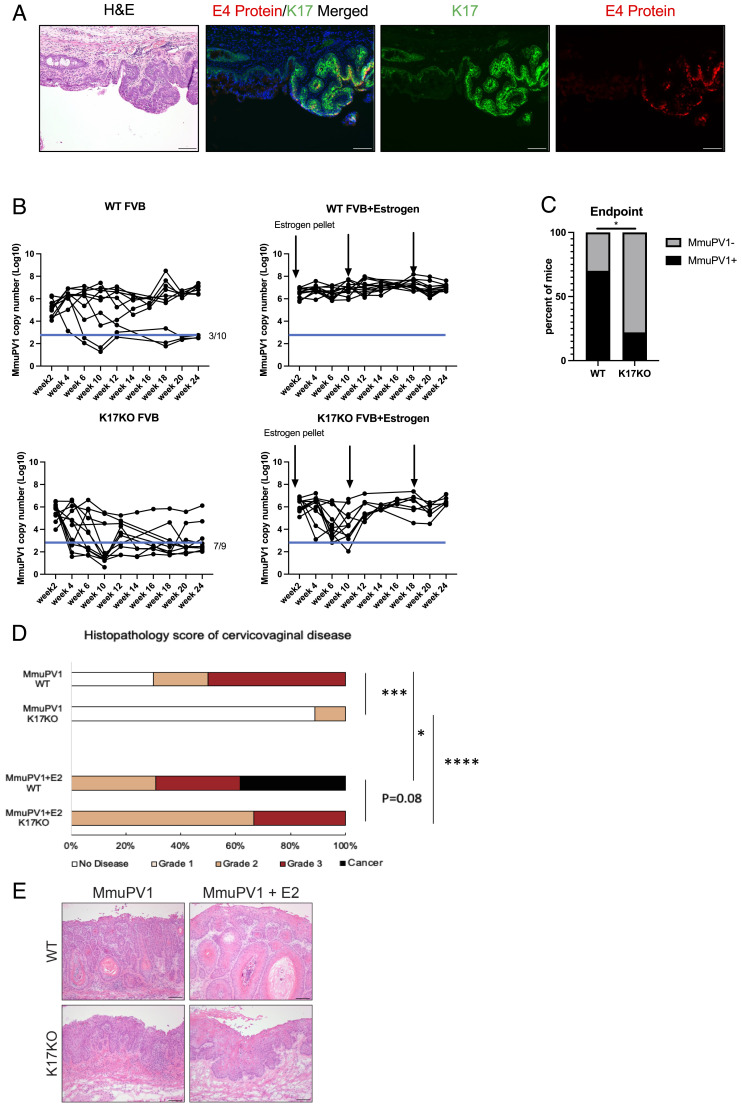

We previously reported that MmuPV1 is sexually transmitted and can naturally infect the reproductive tract of female ‘recipient’ mice (8). We performed immunofluorescence for K17 on the reproductive tracts of female recipient mice from this study, which are female mice that naturally acquired MmuPV1 from male mice via sexual transmission. Using immunofluorescence analysis, we costained for K17 protein and the MmuPV1 E4 protein on the same tissue section (Fig. 1A). We observed overexpression of K17 in focal areas of the mucosal epithelia corresponding to MmuPV1-infected regions within the female reproductive tract. These results are consistent with results obtained using in situ RNA hybridization (RNAscope) for MmuPV1 E4 transcripts and K17 immunofluorescence on separate, adjacent tissue sections (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), in which we also observed K17 protein overexpression in regions of tissue expressing MmuPV1 E4 transcripts. These findings indicate that natural MmuPV1 infection of mucosal epithelia induces K17 expression consistent with our earlier findings that MmuPV1 induces K17 expression in cutaneous epithelia (11).

Fig. 1.

K17 and estrogen cooperate to promote viral persistence and disease progression in MmuPV1-infected reproductive tract tissues. (A) K17 expression is increased in MmuPV1-infected epithelia of the female reproductive tract. K17 and MmuPV1 E4 are costained on the same slide for immunofluorescence detection. Green: K17, Red: MmuPV1 E4 protein, Blue: Hoescht (nuclei). (B) qPCR analysis of MmuPV1 viral copy number per 5 ng vaginal lavage DNA across 24 wk postinfection. Black arrows indicate estrogen pellet insertion. Blue line indicates level of background signal detected in mock-infected animals. WT FVB: n = 10, WT FVB+Estrogen: n = 13, K17KO FVB: n = 9, K17KO FVB+Estrogen: n = 6. (C) The chi-square test of WT mice that cleared infection at the end point (3 out of 10) vs. K17KO mice that cleared infection at the end point (7 out of 9). (D) Histopathology analysis of cervicovaginal disease severity. WT FVB: n = 10, WT FVB+Estrogen: n = 13, K17KO FVB: n = 9, K17KO FVB+Estrogen: n = 6. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare disease severity between groups. (E) Representative H&E images of MmuPV1-infected reproductive tract tissue from each group. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.005 ****P < 0.001 ns=not significant. Error bars indicate (SEM). All (Scale bars = 100 μm.)

To test whether K17 is required for persistent MmuPV1 infections, we experimentally infected the reproductive tracts of wild-type (WT) and germline K17 knock-out (K17KO) female mice, both on the FVB/N genetic background, with 108 viral genome equivalents (VGE) and performed vaginal lavages every 2 wk over a 6-mon time course to track MmuPV1 copy number using qPCR. We observed that approximately 30% (n = 3/10) of WT mice spontaneously cleared MmuPV1 infection, based upon qPCR cycle threshold values that were comparable to mock-infected animals. The incidence of spontaneous viral clearance in WT animals is similar to our previous results (7), and we speculate that the strength of an individual’s immune response may contribute to viral clearance or persistence. In contrast, 78% (n = 7/9) of the K17KO mice spontaneously cleared their infections (Fig. 1B), resulting in a significantly lower number of K17KO mice with persistent MmuPV1 infections at the 6-mon endpoint (Fig. 1C, P < 0.05). Mice that cleared their infection did not develop neoplastic disease (Fig. 1D) and animals with persistent MmuPV1 infections developed various grades of cervicovaginal disease with disease severity being significantly worse in the WT mice compared to K17KO mice (Fig. 1 D and E).

To assess the effect of estrogen on viral clearance and disease progression in the presence or absence of K17 expression, we treated MmuPV1-infected wild-type and K17KO mice with exogenous estrogen by subcutaneous implantation of a continuous-release pellet that delivers 0.05 mg of 17β-estradiol over a 60-d period. This dose of estrogen induces a physiological level of estrogen that mimics persistent estrus in female mice (54). We have previously shown that extended treatment with estrogen alone was sufficient to drive carcinogenesis in MmuPV1-infected mice without inducing immunosuppression by UV treatment (7); therefore, no UV treatment was given to these animals. All estrogen-treated mice (n = 13/13 WT, n = 6/6 K17KO) developed persistent MmuPV1 infections that failed to clear over 6 mon (Fig. 1B). The viral copy number in some estrogen-treated K17KO (K17KO+E2) mice declined to near mock-infected levels by 10 wk postinfection, but in all cases rebounded thereafter such that all K17KO+E2 mice retained persistent infections and developed cervicovaginal disease by the endpoint (Fig. 1 B, D, and E). Estrogen-treated wild-type animals (WT+E2), unlike K17KO+E2 mice, maintained high MmuPV1 copy numbers throughout the course of the study (Fig. 1B). At the endpoint, disease severity in the WT+E2 mice trended toward being more severe than in K17KO+E2 mice (P = 0.08), with approximately 40% (n = 5/13) of WT+E2 mice developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), compared to 0% (0/6) in K17KO+E2 animals (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these data indicate that cervicovaginal carcinogenesis requires persistent MmuPV1 infections, similar to the natural history of high-risk HPV infections and human cervical disease (55). Our data also indicate that estrogen and K17 expression, together, can potentiate persistent MmuPV1 cervicovaginal infections, reduce spontaneous viral clearance, and exacerbate neoplastic disease including progression to SCC.

Estrogen, but Not K17, Increases MmuPV1 Viral Copy Number at Early Times Postinfection in the Reproductive Tract of Immunocompetent Mice.

We detected MmuPV1 in vaginal lavages at 2 wk postinfection (Fig. 1B), which was the earliest timepoint we performed lavages to avoid potential disruption to viral establishment. While MmuPV1 established infections in all animals (Fig. 1B), we consistently observed significantly higher MmuPV1 copy numbers in estrogen-treated animals at 2 wk postinfection irrespective of the K17 status (Fig. 2A). These findings suggest that estrogen, but not K17, increases viral copy number at early times postinfection. The estrogen-induced increase in MmuPV1 copy number correlated with lower circulating CD4 and CD8 T cell counts in the blood of estrogen-treated animals (Fig. 2B). By 5 mon postinfection, the difference in the number of circulating CD8+ T cells between untreated WT and estrogen-treated WT animals infected with MmuPV1 was not significant (Fig. 2B), likely due to a smaller sample size. The estrogen-mediated suppression of circulating T cell count was also observed in mock-infected mice, indicating the immunosuppressive effect of estrogen was independent of MmuPV1 infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). These findings demonstrate that estrogen led to a systemic suppression of immune cells. The data in Fig. 2B also indicate that in K17KO mice not treated with estrogen, there is a substantial increase in levels of all circulating immune cell types with the exception of CD4+ T cells at 5 mon postinfection.

Fig. 2.

Estrogen but not K17 promotes early establishment of MmuPV1 infection in the female reproductive tract of immunocompetent mice. (A) Mouse reproductive tracts were infected with 108 VGE MmuPV1. MmuPV1 viral copy number per 5ng vaginal lavage DNA at 2 wk postinfection was measured using quantitative PCR. WT FVB: n = 9, WT FVB+Estrogen: n = 9, K17KO FVB: n = 5, K17KO FVB+Estrogen: n = 5. A Student's t test was used to compare MmuPV1 copy numbers between groups. (B) Total white blood cell counts (WBC) were obtained by a complete blood count (CBC) automatic counter. Specific cell-type percentages were determined by flow cytometry and were multiplied by the total WBC count to determine cell count per type. Three mice were included per group. (C) Reproductive tracts of WT FVB mice were infected with 106 VGE, 107 VGE, or 108 VGE MmuPV1 and left untreated or treated with exogenous estrogen. N = 6 to 9 mice per group. MmuPV1 copy number at 2 wk postinfection were compared using Student's t test within each infection dose. (D) Reproductive tracts of NSG mice were infected with 106 VGE, 107 VGE, or 108 VGE MmuPV1 and left untreated or treated with exogenous estrogen. N = 6 to 9 mice per group. MmuPV1 copy number values at 2 wk postinfection were compared using Student's t test within each infection dose. (E) Histopathology score of cervicovaginal disease in WT reproductive tracts collected at 6 mon postinfection. 106 VGE n = 1 mouse, 106 VGE+Estrogen n = 5 mice, 107 VGE n = 3 mice, 107 VGE+Estrogen n = 6 mice, 108 VGE n = 4 mice, 108 VGE+Estrogen n = 3 mice. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare disease severity between groups. (F) Histopathology score of cervicovaginal disease of NSG mouse reproductive tracts collected at 10 wk postinfection. 106 VGE n = 6 mouse, 106 VGE+Estrogen n = 5 mice, 107 VGE n = 6 mice, 107 VGE+Estrogen n = 6 mice, 108 VGE n = 4 mice, 108 VGE+Estrogen n = 4 mice. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare disease severity between groups. (G) Representative H&E images of MmuPV1-infected reproductive tract tissues from mice infected with 108 VGE MmuPV1. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.005 ****P < 0.001 ns=not significant. Error bars indicate (SEM). All (Scale bars = 100 μm.)

To test whether estrogen-mediated immunosuppression was responsible for the enhanced viral copy number and disease progression we observed in estrogen-treated WT mice (Fig. 1), we infected groups of immunocompetent WT (FVB/N) mice and immunodeficient NOD-scid IL2Rgnull (NSG) mice with or without exogenous estrogen treatment and measured MmuPV1 copy number at 2 wk postinfection. In addition to our standard dosage (108 VGE), we also used lower virus doses (106 and 107 VGE) to avoid saturating epithelia with infection in the highly susceptible NSG mice. We again observed significantly or trending toward significantly higher MmuPV1 copy number in estrogen-treated immunocompetent WT mice at all three doses (Fig. 2C). In contrast, estrogen did not increase MmuPV1 copy number in NSG mice (Fig. 2D). Consistent with our prior observations (Fig. 1D), estrogen increased overall disease severity in WT mice across all virus doses and SCC only developed in estrogen-treated animals infected with 108 and 107 VGE (Fig. 2E). However, due to the small group sizes that remained at the endpoint of this study (a consequence of animal housing issues and not morbidity), these differences did not reach statistical significance. In our previous work, we found that immunodeficient mice (FoxN1nu/nu) developed SCC by 4 mon postinfection in the absence of estrogen treatment (7). Therefore, we collected tissues from NSG mice at an earlier time point (2 mon postinfection) to evaluate the influence of estrogen on disease progression in immunodeficient mice. Estrogen did not exacerbate disease progression in the NSG mice (Fig. 2 F and G), though in one group (107 VGE), there were two SCC scored at the 2-mon endpoint, which was somewhat unexpected for such an early timepoint postinfection. Overall, we conclude that the effect of estrogen on early MmuPV1 viral copy number and neoplastic disease progression in the female reproductive tract is based, at least in part, on estrogen’s suppression of the host immune system in immunocompetent mice.

Estrogen and K17 Modulate Local Immune Cell Infiltration in MmuPV1-Infected Cervical Tissues.

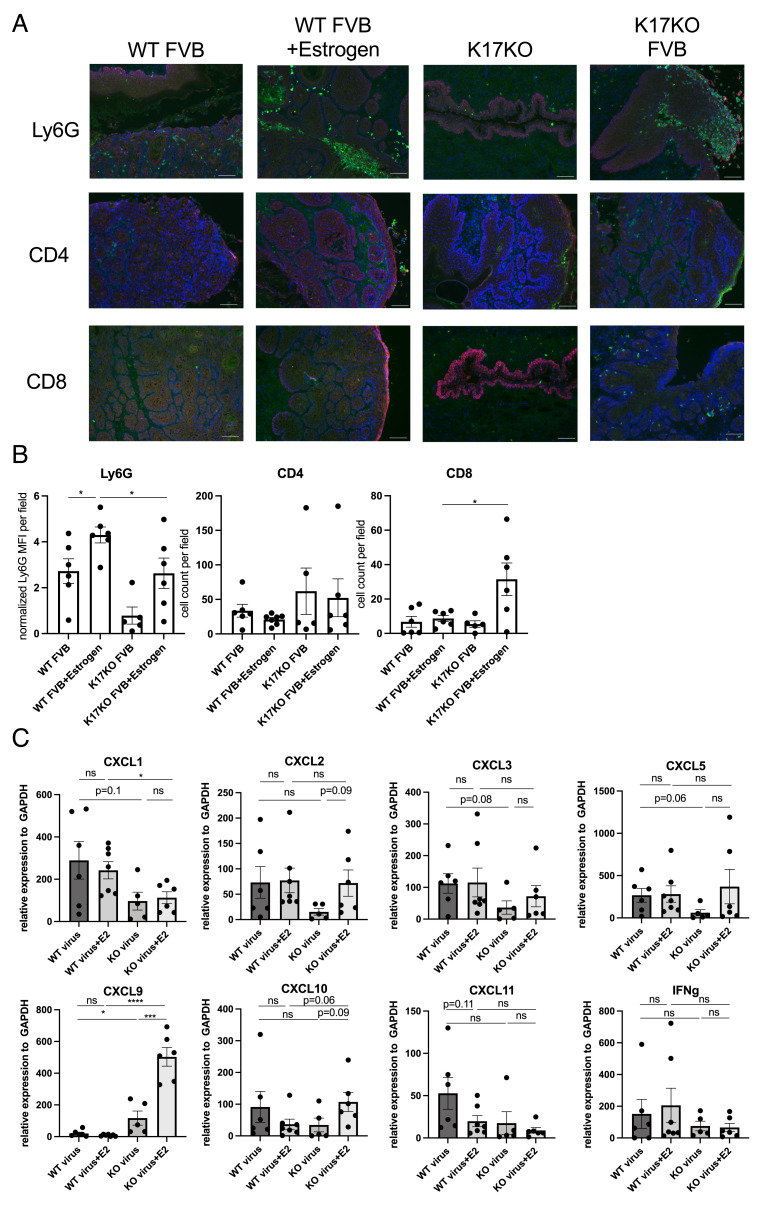

Our analyses of blood from MmuPV1-infected animals (Fig. 2B) demonstrated that exogenous estrogen treatment caused a reduction in circulating immune cells, consistent with systemic immune suppression and, conversely, that in the absence of K17, there were enhanced levels of circulating immune cells at 5 mon postinfection. This prompted us to ask if exogenous estrogen treatment and/or K17 gene status also modulate the local immune microenvironment in the context of MmuPV1-infected cervicovaginal tissues. We collected MmuPV1-infected reproductive tissues at 6 mon postinfection (endpoint of Fig. 1 B and D) and performed immunofluorescence for Ly6G (neutrophil marker) and CD4/CD8 (T cell markers) (Fig. 3A). Corresponding H&E-stained tissue sections for each field within the reproductive tract are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3. We quantified immune cell infiltration by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for Ly6G and counting the number of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in tissues from the four cohorts of mice. Overall, the number of intraepithelial neutrophils was significantly higher than intraepithelial T cells. In K17KO mice, we observed minimal infiltration of immune cells in tissues collected at the endpoint (6 mon postinfection), including in tissues of mice that cleared infection and did not have disease at the endpoint (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3), suggesting a dampened immune response correlating with less detectable immune infiltration in tissues cleared of infection (Fig. 1 B and D). In estrogen-treated K17KO tissues, all animals developed low- to high-grade disease (Fig. 1D) with a significantly higher infiltration of CD8+ T cells and lower infiltration of neutrophils than estrogen-treated wild-type animals (Fig. 3 A and B), suggesting that K17 expression suppressed T cell infiltration and enhanced neutrophil infiltration. When comparing wild-type animals with or without an estrogen supplement, neutrophil infiltration was increased by estrogen treatment (Fig. 3 A and B). Taken together, these data suggest that K17 downregulates T cell infiltration and cooperates with estrogen to upregulate neutrophil infiltration in the tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 3.

Estrogen and K17 modulate immune cell infiltration in MmuPV1-infected cervical tissues. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images (10×) of reproductive tract tissues analyzed for Ly6G (Top; green), CD4 (Middle; green), and CD8 (Bottom; green) expression. Red: K14, Blue: Hoescht (nuclei). (B) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for Ly6G staining normalized to background per field (Left), and intraepithelial number of CD4+ (Middle) and CD8+ (Right) cells. N = 4 to 6 mice per group were included for analysis. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR of gene expression normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) from bulk RNA extracted from whole reproductive tissues. N = 4 to 6 mice per group were included for analysis. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *P < 0.05 ***P < 0.005 ****P < 0.001 ns = not significant. The error bar indicates (SEM). All (Scale bars = 100 μm.)

To determine which chemokines and cytokines may be responsible for T cell and neutrophil infiltration, we extracted RNA from whole reproductive tract tissue sections and performed quantitative RT-PCR for neutrophil chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, and CXCL5) and T cell chemokines (CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11), as well as the T cell activation marker IFNgamma. Among the four neutrophil chemokines that we analyzed, only CXCL1 levels were significantly higher in WT+E2 animals compared to K17KO+E2 animals (Fig. 3C), correlating with the increased neutrophil infiltration observed in wild-type animals (Fig. 3B). CXCL1 protein levels were confirmed by immunofluorescence staining on a subset of tissues included for qRT-PCR analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). However, there was no difference in chemokine expression between untreated and estrogen-treated wild-type animals (Fig. 3C), suggesting that other mechanisms must be involved in the estrogen-dependent upregulation of neutrophil recruitment to MmuPV1-infected lesions. Among the three T cell chemokines examined, we found CXCL9 expression correlated with higher CD8+ T cell infiltration in K17KO+E2 tissues (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). There were no differences in expression of innate immunity-related cytokines (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

The T cell activation marker, IFNgamma, was not significantly expressed in the total RNA extracted from the whole tissue sections (Fig. 3C), where T cell numbers were relatively low. Therefore, we collected the spleen from mice from these four groups and stimulated splenic cells ex vivo with PMA and Ionomycin to measure IFNgamma+-activated T cells. Interestingly, we observed accumulation of both granulocytic MDSC (CD11b+Gr1 high, mostly neutrophils) and monocytic MDSC (CD11b+Gr1 low) in the spleen of estrogen-treated mice compared to untreated mice (WT+E vs. WT, K17KO+E vs. K17KO, SI Appendix, Fig. S7). This accumulation correlated with lower numbers of activated CD4 and CD8 T cells in wild-type animals (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). However, the accumulation of these myeloid cells in estrogen-treated K17KO mice did not suppress T cell activation ex vivo, suggesting that these myeloid cells, including neutrophils, may not possess immunosuppressive and protumoral functions. Thus, K17 and estrogen seem to exert effects on different populations of immune cells to synergistically prevent T cell infiltration and activation, leading to viral persistence and disease progression to SCC.

Neutrophil Depletion Promotes Disease Progression in Estrogen-Treated K17KO Mice, but Not Estrogen-Treated WT Mice.

In cancer patients, the neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio in circulating blood correlates with the prognosis of various cancers, including cervical cancer (56–64). Using the quantitative results from the neutrophil and T cell marker immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 3B), we evaluated whether the level of neutrophil or T cell infiltration was associated with disease severity in sites of MmuPV1-induced cervicovaginal disease. Indeed, there was a significant (P = 0.0002) positive correlation between neutrophil infiltration and disease severity (Fig. 4A), similar to what is observed in cancer patients (59, 62, 65). Neither CD4 (P = 0.72) nor CD8 (P = 0.46) infiltration levels correlated with disease severity (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Fig. 4.

Neutrophil depletion promotes disease progression in estrogen-treated K17KO mice but not in estrogen-treated WT mice. (A) Spearman correlation analysis between disease severity and normalized Ly6G mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) per field. N=4–6 mice per group were included for analysis. (B) MmuPV1-infected and estrogen-treated WT and K17KO animals were intraperitoneally injected with anti-Ly6G depletion antibody (Dep) or isotype control antibody (ISO) starting at 7 wk postinfection, three times per week, until 12 wk postinfection. Blood from n = 3 mice per group was analyzed to count the number of cells positive for Gr1, Ly6C, CD4, and CD8. (C) Vaginal lavages were performed every 2 wk to quantify MmuPV1 viral copy number per 5 ng DNA. N = 9 to 14 mice per group were included for analysis. (D) Reproductive tracts were collected at 12 wk postinfection, immediately after completion of the final antibody injection, and subsequent histopathology of cervicovaginal disease was analyzed. WT+E2 ISO: n = 9, WT+E2 Ly6G-Dep: n = 13, K17KO+E2 ISO: n = 9, K17KO+E2 Ly6G-Dep: n = 8. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare disease severity between groups. (E) A proposed mechanism of action by K17 and estrogen in modulating the cervicovaginal microenvironment in MmuPV1-infected tissue.

Whether neutrophils contribute directly to disease progression or are simply a biomarker for disease severity remains unclear. To begin to address this question, we depleted neutrophils using anti-Ly6G antibody for a time period between 7 wk and 11 wk postinfection in estrogen-treated wild-type and K17KO animals. We monitored MmuPV1 copy number via vaginal lavage and evaluated disease severity at the end of 11 wk. Treatment with anti-Ly6G antibody depleted over 90% circulating neutrophils compared to isotype control-treated mice (Fig. 4B). The average MmuPV1 copy number over time was not affected by neutrophil depletion (Fig. 4C). Moreover, disease severity was not significantly different when neutrophils were depleted in WT+E2 mice (P = 0.41) (Fig. 4 D and E), suggesting that neutrophil depletion in wild-type animals was not sufficient to overcome the immunosuppressive environment induced by estrogen, despite increased neutrophil infiltration observed as a marker for aggressive disease. Interestingly, K17KO+E2 animals developed more severe disease when neutrophils were depleted that trended toward statistical significance (P = 0.061) (Fig. 4 D and E). These data are consistent with our observation that the increased MDSC counts in the spleen of estrogen-treated K17KO mice did not suppress T cell activation (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), suggesting that neutrophils recruited to MmuPV1-infected K17KO tissues have antitumoral rather than protumoral functions.

Discussion

In this report, we have identified two host factors, K17 and estrogen, that cooperate to support persistent MmuPV1 infection and neoplastic disease progression in the murine female reproductive tract through modulation of the host immune environment. Our studies revealed that K17 is overexpressed in MmuPV1-infected mucosal cervicovaginal epithelia and is required for persistent infections and the subsequent development of dysplastic disease (Fig. 1). We also found that estrogen significantly increases viral load at early points after infection (Fig. 2) and exacerbates viral persistence and disease severity (Fig. 1), effects that are largely lost in immunodeficient NSG mice (Fig. 2). These results prompted us to interrogate the role of estrogen and K17 in regulating the immune response during MmuPV1-induced cervicovaginal disease. We found that estrogen-treated animals develop systemic immunosuppression (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2) and yet have significantly higher local infiltration of neutrophils in MmuPV1-infected lesions (Fig. 3 A and B). Except CXCL1, which was increased in WT+E2 tissues compared to KO+E2 tissues, we did not see significant differences in many well-known neutrophil chemoattracting chemokines across treatment groups (Fig. 3C), nor did we see substantial differences among innate immunity-related cytokines (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Although CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, and CXCL5 are all known to mediate neutrophil migration, they can have distinct cellular sources and nonredundant functions in different disease settings. One recent study has shown two different cell types are responsible for CXCL1 and CXCL2 production, respectively, in neutrophil emigration in mouse cremaster muscles, and they work on different stages of neutrophil migration (66). Mast cell and macrophage-derived CXCL1/CXCL2 have distinct effects on neutrophil migration at early stages (67). CXCL5 attracts not only neutrophils but also innate and adaptive leukocytes (68). Our results indicate that K17 may affect a particular cell type in the stroma that produces CXCL1 in MmuPV1-infected tissues.

Like our observations in cutaneous disease (11), we found that CD8+ T cell infiltration is increased in the absence of K17 in MmuPV1-infected cervicovaginal epithelia and correlates with an increase in expression of the T cell chemoattractant chemokine CXCL9, although these T cells do not appear to be activated (Fig. 3). This observation is consistent with our published data in a MmuPV1 infection model (11) and HPV negative head and neck cancer model (69) although we did not observe a difference in CXCL10 or CXCL11 mRNA levels. Despite binding to the same CXCR3 receptor, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 are induced by different cytokine stimulations (70) and have distinct functions in T cell migration under different settings (71–74). The fact that K17 affects only CXCL9 in MmuPV1-infected cervicovaginal tissues may provide insight into which cell types are regulated by K17 and responsible for K17-mediated immunosuppression. Interestingly, staining for CXCL1 and CXCL9 proteins revealed that the major source of these two chemokines was the stromal compartment of the tissue (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). These results indicate that estrogen and K17 modulate the microenvironment in infected tissues, potentially through regulation of tissue-infiltrating immune cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells in the stroma.

We also found evidence that K17 cooperates with estrogen to regulate neutrophil recruitment (Fig. 3), the level of which positively correlated with disease severity (Fig. 4A). Neutrophil depletion in MmuPV1-infected animals did not affect MmuPV1 viral copy numbers and only exacerbated disease severity in K17KO+E2 mice (Fig. 4 C and D), suggesting the presence of neutrophils with antitumoral functions in tumor microenvironment of K17KO neoplastic tissues. Collectively, the results presented here reveal that estrogen and K17 have distinct, yet some complementary, roles in regulating systemic and local immune environments during MmuPV1 infection and disease progression in the female reproductive tract of mice.

Our lab and others have established several lines of evidence, mostly using HPV16 transgenic mouse models, that estrogen contributes to HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis, although some reports dispute the role of this hormone. The conflicting data likely stem from highly variable experimental conditions, study designs, and patient populations (75, 76). In HPV16 transgenic mice, estrogen and its receptor ERα are necessary for the onset, maintenance, and progression of cervical cancer (17–19, 39, 54). FDA-approved antiestrogen drugs such as fulvestrant and raloxifene prevent and cause regression of HPV-mediated cervical cancers in mice (21). Stromal ERα and signaling in the microenvironment are necessary and sufficient for cervical carcinogenesis (40) and we have reported that both the HPV oncogenes and estrogen significantly affect the expression of genes and paracrine-acting factors in the stroma (38, 41). Together, the evidence from HPV transgenic mice suggest that estrogen is necessary for cervical carcinogenesis, but epithelial ERα is dispensable for such progression in HPV transgenic mice.

Interestingly, a recent report indicated that estrogen limits the growth of HPV+ epithelial cells in vitro by reducing HPV early gene transcription (35). Because epithelial ERα is dispensable for cervical carcinogenesis in HPV transgenic mice (40) and ERα expression is frequently lost in cervical cancer epithelial cells (38), it is postulated that estrogen may enhance cervical carcinogenesis through extrinsic mechanisms in the stromal compartment rather than intrinsic regulation in epithelial cells. Several recent studies have indicated that, in other tumor models and clinical settings, estrogen induces MDSC immobilization through STAT3 activation and inducing JAK2 and SRC activity in myeloid cells, thus enhancing immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs in cancer (42–46). More importantly, estrogen-induced immunosuppression is independent of epithelial estrogen signaling in these models (42, 45, 46). In our current study, we observe strong estrogen-mediated effects on MmuPV1 viral copy number and persistence, which is largely lost in NSG mice. Our data provide additional evidence to suggest that estrogen acts to regulate T cell-suppressing immune populations to exacerbate cervicovaginal disease.

Recently, Hu and colleagues published results showing that estrogen treatment had no effect on MmuPV1 viral copy number in the murine anogenital tract, including the female reproductive tract, in heterozygous FoxN1nu/+ mice (77). These disparate findings can perhaps be explained by the genetic background of mice used in MmuPV1 in vivo studies, particularly if the effects are immune-mediated. There is ample evidence that different genetic backgrounds exhibit differential susceptibility to MmuPV1 infection and subsequent disease (3). Nevertheless, our current results showing that estrogen induces a significant increase in early viral load and subsequent persistence is consistent with human epidemiological data that cites high viral load as one of the strongest predictors of and factors associated with HPV-persistent infections (78–81). High viral load has also been associated with more severe histological disease and cancer (82–84). Our current results suggest that estrogen significantly impacts each stage across the spectrum of MmuPV1-induced neoplastic disease, from infection to carcinogenesis, at least in part by modulating the host immune environment.

Our results show that K17, often in concert with estrogen, also plays a role in MmuPV1 persistence and disease in the female reproductive tract. K17 is overexpressed in many cancers and is required for cervicovaginal disease in HPV transgenic mice (85–92) and cutaneous disease in MmuPV1-infected skin (11). However, the exact mechanisms and pathways leading to K17 expression during papillomavirus infection remain unknown. Here, we provide evidence that K17 is overexpressed in MmuPV1-infected mucosal epithelia tissues (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). K17 expression in infected epithelia led to decreased spontaneous viral clearance (Fig. 1 B and C), likely due to suppressed CD8+ T cell infiltration, which resulted in moderate to severe dysplasia (Fig. 1D). Despite the K17-mediated immunosuppression, few mice progressed to SCC within 6 mon. However, estrogen greatly accelerated this process (Fig. 1D). Our current data suggest that estrogen systemically reduces circulating immune cells (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2) and may locally increase neutrophil recruitment to disease sites (Fig. 3), which is a biomarker for worse prognosis in human cancers (59, 62, 65, 93). Neutrophils present in cancers are often considered immunosuppressive and protumoral (47–49, 94, 95). Arginase-1 secreted by neutrophils can deplete L-arginine, an amino acid needed for T cell receptor ζ chain expression, which is a part of the T cell activation pathway (49, 96–102). In addition, reactive oxygen species produced by neutrophils are also capable of inhibiting T cell activation (103). Neutrophils may also interact with and induce other immunosuppressive cells like Tregs to mediate immunosuppression (104, 105). A human patient study observed a significant number of neutrophils infiltrating human cervical neoplastic lesions, and they have shown the infiltrating neutrophils in lesions express the CD16highCD62Ldim immunosuppressive phenotype markers (106). In our current study, we have seen an accumulation of neutrophils in disease lesions as well as the spleen of estrogen-treated animals (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). We have also observed an inverse correlation of neutrophil number with activated T cell numbers in the spleen of wild-type mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), suggesting an immunosuppressive status of the neutrophils in estrogen-treated wild-type mice. However, depleting neutrophils from K17-expressing animals was not sufficient to affect viral copy number or disease progression. One possible explanation is that eliminating neutrophils, which are considered protumoral in wild-type animals, is not enough to overcome the immunosuppressive microenvironment when K17 overexpression can still prevent CD8+ T cell infiltration (Fig. 4E). Besides protumoral neutrophils, heterogeneity studies in neutrophils have uncovered antitumoral neutrophil subsets that can mediate cytotoxicity or apoptosis of tumor cells (107–113). In the absence of K17, the neutrophils seemingly switch from a protumoral to an antitumoral subtype based on the observation that depletion of neutrophils in K17KO mice exacerbated cervicovaginal disease (Fig. 4D) and that splenic neutrophil accumulation correlated with higher activated CD8+ T cell number (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), opposite to what is observed in wild-type mice. These data are consistent with our prior observations in another tumor model (69), that K17 not only prevents T cell infiltration but also modulates the landscape of myeloid cells in the head and neck tumor microenvironment. Our current study suggests that K17 may modulate the plasticity of neutrophils in addition to other myeloid cells. Further studies are required to identify antitumoral neutrophil markers present in K17KO animals as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms by which K17 and estrogen modulate the microenvironment and neutrophil polarization.

Despite the convenience of using MmuPV1 as a preclinical model to study the immune response to and role of estrogen in papillomavirus infection-mediated neoplastic progression, there are also limitations. Unlike mucosal high-risk HPVs, MmuPV1 is classified in the genus Pipapillomavirus (114) and lacks the HPV oncoprotein E5 (13) and the MmuPV1 E6 and E7 proteins lack many conventional HPV oncoprotein binding motifs (114, 115). Although MmuPV1 is clearly pathogenic at several of the anatomical sites targeted by HPVs, the molecular functions of MmuPV1 oncoproteins and how they induce K17 expression remain the focus of ongoing studies. Hormone-mediated mechanisms involved in human disease, such as those involving estrogen, can also be difficult to accurately replicate in preclinical models. While the estrogen dose administered in our study has been shown to induce conditions consistent with persistent estrus in mice (54) models that rely upon endogenous physiological estrogen levels warrant investigation in our studies. Epidemiological studies have identified associations between several conditions that elevate estradiol levels in humans with increased risk for HPV persistence and subsequent neoplastic progression in the female reproductive tract, such as long-term oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, and multiparity (75, 116–122). Given that estradiol levels also increase during the murine gestational period (123), future studies could explore the effect of pregnancy and/or multiparity on MmuPV1 viral persistence, clearance, and malignant progression under conditions where estrogen levels are naturally increased as opposed to exogenous treatment.

Our study provides evidence that estrogen and K17 cooperate to promote disease progression and do so by acting on different aspects of the host immune response in order to exert immunosuppressive effects in MmuPV1-infected cervicovaginal mucosal tissue (Fig. 4E). These findings provide new insight into how estrogen and K17 contribute to viral persistence and cervical carcinogenesis. Future studies targeting K17-mediated immunosuppression with antiestrogen drugs may benefit from such synergistic mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Animals, Treatment, and Tissue Processing.

Wild-type FVB/N mice were obtained from Taconic and bred for this study as wild-type controls. K17 knockout (K17KO) mice on the FVB/N genetic background were provided by Pierre A Coulombe (Johns Hopkins University) and have been described previously (124). Immunodeficient NOD-scid IL2Rgnull (NSG) mice (Jackson Laboratory; Stock #005557) were bred and provided by the UW-Madison Biomedical Research Models Services Laboratory. Six- to eight-wk-old female mice were used for all infection experiments. FVB/N, K17KO, and NSG female mice were either untreated or treated with exogenous estrogen (17β-estradiol). Reproductive tracts were sectioned and used for histopathological analysis to assign disease severity. Mice were housed in strict accordance with guidelines approved by the Association for Assessment of Laboratory Animal Care, at the University of Wisconsin Medical School. All protocols for animal work were approved by the University of Wisconsin Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number M005871).

MmuPV1 Infection and MmuPV1 Copy Number Quantification.

Crude preparations of MmuPV1 were generated by isolating virions from cutaneous papillomas collected from FoxN1nu/nu mice and quantified for VGE (viral genome equivalents) using the protocol described previously (10). MmuPV1 infection of the female reproductive tract was performed using methods described previously (7, 125). To quantify MmuPV1 viral copy number, vaginal lavages were performed and total DNA extracted from collected material was analyzed for the MmuPV1 E2 gene by qPCR as described previously (5, 7, 126).

Blood Cell Count and Flow Cytometry Analysis.

Mice underwent submandibular bleeding, and blood samples were counted by Hemavet for a complete blood count. Then, 15 μL of blood per mouse was lysed for red blood cells (Tonbo Biosciences RBC lysis buffer) and stained with conjugated antibodies for flow cytometry analysis using FisherThermo Attune. The following antibodies were used for staining: anti-CD45 APC-Cy7 (BioLegend, clone 30-F11), anti-CD4 PE (BioLegend, clone RM4-5), anti-CD8a FITC (BioLegend, clone 53 to 6.7), anti-Gr1 PE-Cy5 (BioLegend, clone RB6-8C5), anti-CD11b BV605 (BioLegend, clone M1/70), and anti-Ly6C APCeFluor780 (BioLegend, clone HK1.4). Data were analyzed in FlowJo.

Neutrophil Depletion.

For neutrophil depletion experiment, 250 μg of anti-Ly6G (BioXCell, clone 1A8) or 250 μg of isotype control (BioXCell, rat IgG2a) was delivered by intraperitoneal injection three times per week, starting at 7 wk post-MmuPV1 infection until 11 wk postinfection. To assess neutrophil depletion, anti-Gr1 PE-Cy5 (BioLegend, clone RB6-8C5), anti-CD11b BV605 (BioLegend, clone M1/70), and anti-CD45 APC-Cy7 (BioLegend, clone 30-F11) were used for flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence Analysis and RNA In Situ Hybridization.

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on sections collected as unfixed frozen tissues. Tissue sections were fixed in cold methanol in –20 °C for 10 min, washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) +0.01% Triton X-100, followed by a PBS wash, blocked with 5% goat serum at room temperature for 1 h, and stained with purified primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. Tissues were then washed with PBS three times, stained with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h, and counterstained with Hoechst Dye and mounted in Prolong mounting media (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To perform MmuPV1 E4-K17, CXCL1-K14, and CXCL9-K14 dual fluorescence, we employed a tyramide-based signal amplification (TSA) method (127). A detailed method is described online (https://www.protocols.io/view/untitled-protocol-5qpvo7o7g4o1/v1) and has been described previously (16, 128). Briefly, TSA was used to detect MmuPV1 E4, CXCL1, or CXCL9. For tissues stained with E4, immunofluorescence was then performed for K17. For tissues stained with CXCL1 or CXCL9, immunofluorescence was then performed for K14. The following antibodies were used for detecting mouse antigens by immunofluorescent staining: CD4 (eBioscience, clone RM4-5), CD8 (eBioscience, clone 53-6.7), K14 (eBioscience, polyclonal Cat#PA5-16722), K17 (Abcam Catalog #109725), CXCL1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Catalog #PA5-115-328), CXCL9 (BioLegend, Cat#5156001), MmuPV1 E4 rabbit antibody (gift from John Doorbar, University of Cambridge), Goat anti-rat AlexaFluor 488 (Molecular Probes), Goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594, Goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 647 (Molecular Probes), anti-streptavidin AlexaFluor 594 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and anti-streptavidin AlexaFluor 647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

MmuPV1 viral transcripts were detected using RNAscope 2.5 HD Assay-Brown (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with probes specific for MmuPV1 E1^E4 (catalog no. 473281) as described previously (7, 13). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin before mounting and cover slipping.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the 2020 AACR-Genentech Immuno-oncology Research Fellowship, Grant Number 20-40-18-WANG, to W.W., a University of Wisconsin-Madison Carbone Cancer Center Transdisciplinary Cancer Immunology-Immunotherapy Pilot Grant, and grants from the NIH (R50 CA211246 to M.E.S. and P01 CA022443, R35 CA210807 to P.F.L.).

Author contributions

W.W., M.E.S., and P.F.L. designed research; W.W., M.E.S., A.P., S.M., E.W.-S., and E.G. performed research; W.W. and M.E.S. analyzed data; and W.W., M.E.S., and P.F.L. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors have patent filings to disclose, as indicated, W.W. and P.F.L. are inventors on a patent that is submitted by the University of Wisconsin that is relevant to this study.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.A.G. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Alani R. M., Munger K., Human papillomaviruses and associated malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 16, 330–337 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingle A., et al. , Novel laboratory mouse papillomavirus (MusPV) infection. Veterinary Pathol. 48, 500–505 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spurgeon M. E., Lambert P. F., Mus musculus Papillomavirus 1: A new frontier in animal models of papillomavirus pathogenesis. J. Virol. 94, e00002-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handisurya A., et al. , Strain-specific properties and T cells regulate the susceptibility to papilloma induction by Mus musculus papillomavirus 1. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004314 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu J., et al. , Tracking vaginal, anal and oral infection in a mouse papillomavirus infection model. J. General Virol. 96, 3554–3565 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyers J. M., Grace M., Lambert P. F., Munger K., Cutaneous HPV8 and MmuPV1 E6 proteins target the NOTCH and TGF-β tumor suppressors to inhibit differentiation and sustain keratinocyte proliferation. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006171 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spurgeon M. E., A novel in vivo infection model to study papillomavirus-mediated disease of the female reproductive tract. mBio 10, e00180-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spurgeon M. E., Lambert P. F., Sexual transmission of murine papillomavirus (MmuPV1) in Mus musculus. Elife 8, e50056 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundberg J. P., Immune status, straiimmune status, strain background, and anatomic site of inoculation affect mousepapillomavirus (MmuPV1) induction of exophytic papillomas or endophytic trichoblastomasn. PLOS One 9, e113582 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uberoi A., Yoshida S., Frazer I. H., Pitot H. C., Lambert P. F., Role of ultraviolet radiation in papillomavirus-induced disease. PLOS Pathog. 12, e1005664 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W., et al. , Stress keratin 17 enhances papillomavirus infection-induced disease by downregulating T cell recruitment. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008206 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei T., Buehler D., Ward-Shaw E., Lambert P. F., An infection-based murine model for papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer. mBio 11, e00908-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue X. Y., et al. , The full transcription map of mouse papillomavirus type 1 (MmuPV1) in mouse wart tissues. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006715 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilger A., et al. , A mouse model of oropharyngeal papillomavirus-induced neoplasia using novel tools for infection and nasal anesthesia. Viruses 12, 450 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King R. E., et al. , A novel in vivo model of laryngeal papillomavirus-associated disease using mus musculus papillomavirus. Viruses 14, 1000 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres A. D., et al. , The human papillomavirus 16 E5 gene potentiates MmuPV1-dependent pathogenesis. Virology 541, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arbeit J. M., Howley P. M., Hanahan D., Chronic estrogen-induced cervical and vaginal squamous carcinogenesis in human papillomavirus type 16 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2930–2935 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brake T., Lambert P. F., Estrogen contributes to the onset, persistence, and malignant progression of cervical cancer in a human papillomavirus-transgenic mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2490–2495 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung S. H., Wiedmeyer K., Shai A., Korach K. S., Lambert P. F., Requirement for estrogen receptor alpha in a mouse model for human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 68, 9928–9934 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley R. R., et al. , Dissection of human papillomavirus E6 and E7 function in transgenic mouse models of cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 63, 4862–4871 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung S. H., Lambert P. F., Prevention and treatment of cervical cancer in mice using estrogen receptor antagonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19467–19472 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caldon C. E., Sutherland R. L., Musgrove E., Cell cycle proteins in epithelial cell differentiation: Implications for breast cancer. Cell Cycle 9, 1918–1928 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carascossa S., Dudek P., Cenni B., Briand P. A., Picard D., CARM1 mediates the ligand-independent and tamoxifen-resistant activation of the estrogen receptor alpha by cAMP. Genes Dev. 24, 708–719 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster J. S., Henley D. C., Bukovsky A., Seth P., Wimalasena J., Multifaceted regulation of cell cycle progression by estrogen: Regulation of Cdk inhibitors and Cdc25A independent of cyclin D1-Cdk4 function. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 794–810 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan H., Zhong Y., Pan Z., Autocrine regulation of cell proliferation by estrogen receptor-alpha in estrogen receptor-alpha-positive breast cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer 9, 31 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C., et al. , Estrogen induces c-myc gene expression via an upstream enhancer activated by the estrogen receptor and the AP-1 transcription factor. Mol. Endocrinol. 25, 1527–1538 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster J. S., Henley D. C., Ahamed S., Wimalasena J., Estrogens and cell-cycle regulation in breast cancer. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 12, 320–327 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J. J., et al. , Estrogen mediates Aurora-A overexpression, centrosome amplification, chromosomal instability, and breast cancer in female ACI rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101, 18123–18128 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nemec A. A., et al. , estrogen drives cellular transformation and mutagenesis in cells expressing the breast cancer-associated R438W DNA polymerase lambda protein. Mol. Cancer Res. 14, 1068–1077 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson L. M., Lees-Miller S. P., Estrogen receptor alpha-mediated transcription induces cell cycle-dependent DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis 32, 279–285 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y. H., Huang L. H., Chen T. M., Differential effects of progestins and estrogens on long control regions of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224, 651–659 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim C. J., et al. , Regulation of cell growth and HPV genes by exogenous estrogen in cervical cancer cells. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 10, 157–164 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitrani-Rosenbaum S., Tsvieli R., Tur-Kaspa R., Oestrogen stimulates differential transcription of human papillomavirus type 16 in SiHa cervical carcinoma cells. J. Gen. Virol. 70, 2227–2232 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruutu M., Wahlroos N., Syrjanen K., Johansson B., Syrjanen S., Effects of 17beta-estradiol and progesterone on transcription of human papillomavirus 16 E6/E7 oncogenes in CaSki and SiHa cell lines. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 16, 1261–1268 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bristol M. L., James C. D., Wang X., Fontan C. T., Morgan I. M., Estrogen attenuates the growth of human papillomavirus-positive epithelial cells. mSphere 5, e00049-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li D., et al. , Estrogen-related hormones induce apoptosis by stabilizing schlafen-12 protein turnover. Mol. Cell 75, 1103–1116.e9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayshree R. S., The immune microenvironment in human papilloma virus-induced cervical lesions-evidence for estrogen as an immunomodulator. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 649815(2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.den Boon J. A., et al. , Molecular transitions from papillomavirus infection to cervical precancer and cancer: Role of stromal estrogen receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E3255–64 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung S. H., Shin M. K., Korach K. S., Lambert P. F., Requirement for stromal estrogen receptor alpha in cervical neoplasia. Horm. Cancer 4, 50–59 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Son J., Park Y., Chung S. H., Epithelial oestrogen receptor alpha is dispensable for the development of oestrogen-induced cervical neoplastic diseases. J. Pathol. 245, 147–152 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spurgeon M. E., et al. , Human papillomavirus oncogenes reprogram the cervical cancer microenvironment independently of and synergistically with estrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E9076–E9085 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakraborty B., et al. , Inhibition of estrogen signaling in myeloid cells increases tumor immunity in melanoma. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e151347 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conejo-Garcia J. R., Payne K. K., Svoronos N., Estrogens drive myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation. Oncoscience 4, 5–6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu C., Zhen Y., Pang B., Lin X., Yi H., Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are regulated by estradiol and are a predictive marker for IVF outcome. Front. Endocrinol. Lausanne 10, 521 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozerova M., Nefedova Y., Estrogen promotes multiple myeloma through enhancing the immunosuppressive activity of MDSC. Leuk Lymphoma 60, 1557–1562 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Svoronos N., et al. , Tumor cell-independent estrogen signaling drives disease progression through mobilization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Discov. 7, 72–85 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aarts C. E. M., et al. , Activated neutrophils exert myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity damaging T cells beyond repair. Blood Adv. 3, 3562–3574 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aarts C. E. M., Kuijpers T. W., Neutrophils as myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 48, e12989 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munder M., et al. , Suppression of T-cell functions by human granulocyte arginase. Blood 108, 1627–1634 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGowan K. M., Coulombe P. A., Onset of keratin 17 expression coincides with the definition of major epithelial lineages during skin development. J. Cell Biol. 143, 469–486 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komine M., Freedberg I. M., Blumenberg M., Regulation of epidermal expression of keratin K17 in inflammatory skin diseases. J. Invest. Dermatol. 107, 569–575 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGowan K. M., Coulombe P. A., Keratin 17 expression in the hard epithelial context of the hair and nail, and its relevance for the pachyonychia congenita phenotype. J. Invest. Dermatol. 114, 1101–1107 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paladini R. D., Takahashi K., Bravo N. S., Coulombe P. A., Onset of re-epithelialization after skin injury correlates with a reorganization of keratin filaments in wound edge keratinocytes: Defining a potential role for keratin 16. J. Cell Biol. 132, 381 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elson D. A., et al. , Sensitivity of the cervical transformation zone to estrogen-induced squamous carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 60, 1267–1275 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moscicki A. B., et al. , Updating the natural history of human papillomavirus and anogenital cancers. Vaccine 30, F24–33 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gago-Dominguez M., et al. , Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and breast cancer risk: analysis by subtype and potential interactions. Sci. Rep. 10, 13203 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasegawa T., et al. , Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio associated with poor prognosis in oral cancer: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer 20, 568 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ittiamornlert P., Ruengkhachorn I., Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of oncologic outcomes in stage IVB, persistent, or recurrent cervical cancer patients treated by chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 19, 51 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsumoto Y., et al. , The significance of tumor-associated neutrophil density in uterine cervical cancer treated with definitive radiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 145, 469–75 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phulari R. G. S., Rathore R. S., Shah A. K., Agnani S. S., Neutrophil: Lymphocyte ratio and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A preliminary study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 23, 78–81 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh S., et al. , Diagnostic efficacy of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in oral potentially malignant disorders and oral cancer. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 64, 243–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang N., et al. , Neutrophils infiltration in the tongue squamous cell carcinoma and its correlation with CEACAM1 expression on tumor cells. PLoS One 9, e89991 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu L., Song J., Elevated neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio can be a biomarker for predicting the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Medicine (Baltimore) 100, e26335 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zou P., Yang E., Li Z., Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent predictor for survival outcomes in cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 21917 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lau D., Lechermann L. M., Gallagher F. A., Clinical translation of neutrophil imaging and its role in cancer. Mol. Imaging Biol. 24, 221–234 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Girbl T., et al. , Distinct compartmentalization of the chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2 and the atypical receptor ACKR1 determine discrete stages of neutrophil diapedesis. Immunity 49, 1062–1076.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De Filippo K., et al. , Mast cell and macrophage chemokines CXCL1/CXCL2 control the early stage of neutrophil recruitment during tissue inflammation. Blood 121, 4930–4937 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo L., et al. , Role of CXCL5 in regulating chemotaxis of innate and adaptive leukocytes in infected lungs upon pulmonary influenza infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 785457 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang W., et al. , Stress keratin 17 expression in head and neck cancer contributes to immune evasion and resistance to immune-checkpoint blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 2953–2968 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith J. S., et al. , Biased agonists of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 differentially control chemotaxis and inflammation. Sci. Signal. 6, 555 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guirnalda P., Wood L., Goenka R., Crespo J., Paterson Y., Interferon γ-induced intratumoral expression of CXCL9 alters the local distribution of T cells following immunotherapy with listeria monocytogenes. Oncoimmunology 2, e25752 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Menke J., et al. , CXCL9, but not CXCL10, promotes CXCR3-dependent immune-mediated kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 1177–1189 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thapa M., Welner R. S., Pelayo R., Carr D. J. J., CXCL9 and CXCL10 expression are critical for control of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection through mobilization of HSV specific CTL and NK cells to the nervous system. J. Immunol. 180, 1098–1096 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Metzemaekers M., Vanheule V., Janssens R., Struyf S., Proost P., Overview of the mechanisms that may contribute to the non-redundant activities of interferon-inducible CXC chemokine receptor 3 ligands. Front. Immunol. 8, 1970 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chung S. H., Franceschi S., Lambert P. F., Estrogen and ERalpha: Culprits in cervical cancer? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21, 504–511 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.James C. D., Morgan I. M., Bristol M. L., The relationship between estrogen-related signaling and human papillomavirus positive cancers. Pathogens 9, 403 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu J., et al. , Depo medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) promotes papillomavirus infections but does not accelerate disease progression in the anogenital tract of a mouse model. Viruses 14, 980 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xi L. F., et al. , Viral load in the natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 infection: A nested case-control study. J. Infect. Dis. 203, 1425–1433 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trevisan A., Schlecht N. F., Ramanakumar A. V., Villa L. L., Franco E. L., The Ludwig-McGill study G. Human papillomavirus type 16 viral load measurement as a predictor of infection clearance. J. Gen. Virol. 94, 1850–1857 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oyervides-Munoz M. A., et al. , Multiple HPV infections and viral load association in persistent cervical lesions in mexican women. Viruses 12, 380 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moscicki A. B., et al. , The natural history of human papillomavirus infection as measured by repeated DNA testing in adolescent and young women. J. Pediatr. 132, 277–284 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luo H., et al. , Evaluation of viral load as a triage strategy with primary high-risk human papillomavirus cervical cancer screening. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 21, 12–16 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lu X., Wang T., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Analysis of influencing factors of viral load in patients with high-risk human papillomavirus. Virol. J. 18, 6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dong L., et al. , Human papillomavirus viral load as a useful triage tool for non-16/18 high-risk human papillomavirus positive women: A prospective screening cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 148, 103–110 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Escobar-Hoyos L. F., et al. , Keratin 17 in premalignant and malignant squamous lesions of the cervix: Proteomic discovery and immunohistochemical validation as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker. Mod. Pathol. 27, 621–630 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hobbs R. P., Batazzi A. S., Han M. C., Coulombe P. A., Loss of keratin 17 induces tissue-specific cytokine polarization and cellular differentiation in HPV16-driven cervical tumorigenesis in vivo. Oncogene 35, 5653–5662 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khanom R., Keratin 17 is induced in oral cancer and facilitates tumor growth. PLOS One 11, e0161163 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang Y. F., et al. , Overexpression of keratin 17 is associated with poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour. Biol. 34, 1685–1689 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Regenbogen E., et al. , Elevated expression of keratin 17 in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma is associated with decreased survival. Head Neck 40, 1788–1798 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Merkin R. D., et al. , Keratin 17 is overexpressed and predicts poor survival in estrogen receptor–negative/human epidermal growth factor receptor-2–negative breast cancer. Hum. Pathol. 62, 23–32 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bai J. D. K., et al. , Keratin 17 is a negative prognostic biomarker in high-grade endometrial carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 94, 40–50 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roa-Pena L., et al. , Keratin 17 identifies the most lethal molecular subtype of pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 9, 11239 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McFarlane A. J., Fercoq F., Coffelt S. B., Carlin L. M., Neutrophil dynamics in the tumor microenvironment. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e143759 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Veglia F., Sanseviero E., Gabrilovich D. I., Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 485–498 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gabrilovich D. I., Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 5, 3–8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sippel T. R., et al. , Neutrophil degranulation and immunosuppression in patients with GBM: Restoration of cellular immune function by targeting arginase I. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 6992–7002 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rodriguez P. C., Quiceno D. G., Ochoa A. C., L-arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood 109, 1568–1573 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ochoa A. C., Zea A. H., Hernandez C., Rodriguez P. C., Arginase, prostaglandins, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 721s–726s (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Makarenkova V. P., Bansal V., Matta B. M., Perez L. A., Ochoa J. B., CD11b+/Gr-1+ myeloid suppressor cells cause T cell dysfunction after traumatic stress. J. Immunol. 176, 2085–2094 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jacobsen L. C., Theilgaard-Monch K., Christensen E. I., Borregaard N., Arginase 1 is expressed in myelocytes/metamyelocytes and localized in gelatinase granules of human neutrophils. Blood 109, 3084–3087 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Feldmeyer N., et al. , Arginine deficiency leads to impaired cofilin dephosphorylation in activated human T lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 24, 303–313 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zea A. H., et al. , L-Arginine modulates CD3zeta expression and T cell function in activated human T lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 232, 21–31 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schmielau J., Finn O. J., Activated granulocytes and granulocyte-derived hydrogen peroxide are the underlying mechanism of suppression of t-cell function in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Res. 61, 4756–4760 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lewkowicz N., Klink M., Mycko M. P., Lewkowicz P., Neutrophil–CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cell interactions: a possible new mechanism of infectious tolerance. Immunobiology 218, 455–464 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Eruslanov E., et al. , Circulating and tumor-infiltrating myeloid cell subsets in patients with bladder cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 130, 1109–1119 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Alvarez K. L. F., et al. , Local and systemic immunomodulatory mechanisms triggered by human papillomavirus transformed cells: a potential role for G-CSF and neutrophils. Sci. Rep. 7, 9002 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sun B., et al. , Neutrophil suppresses tumor cell proliferation via Fas /Fas ligand pathway mediated cell cycle arrested. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 14, 2103–2113 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Siders W. M., et al. , Involvement of neutrophils and natural killer cells in the anti-tumor activity of alemtuzumab in xenograft tumor models. Leuk Lymphoma 51, 1293–1304 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gale R. P., Zighelboim J., Polymorphonuclear leukocytes in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 114, 1047–1051 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Barker E., et al. , Effect of a chimeric anti-ganglioside GD2 antibody on cell-mediated lysis of human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 51, 144–149 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Albanesi M., et al. , Neutrophils mediate antibody-induced antitumor effects in mice. Blood 122, 3160–3164 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Furumaya C., Martinez-Sanz P., Bouti P., Kuijpers T. W., Matlung H. L., Plasticity in Pro- and anti-tumor activity of neutrophils: Shifting the balance. Front. Immunol. 11, 2100 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Evrard M., et al. , Developmental analysis of bone marrow neutrophils reveals populations specialized in expansion, trafficking, and effector functions. Immunity 48, 364–379.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Joh J., et al. , Genomic analysis of the first laboratory-mouse papillomavirus. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 692–698 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Romero-Masters J. C., Lambert P. F., Munger K., Molecular mechanisms of MmuPV1 E6 and E7 and implications for human disease. Viruses 14, 2138 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fischer S., et al. , Endogenous oestradiol and progesterone as predictors of oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) persistence. BMC Cancer 22, 145 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer, Cervical carcinoma and reproductive factors: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 16,563 women with cervical carcinoma and 33,542 women without cervical carcinoma from 25 epidemiological studies. Int. J. Cancer 119, 1108–1124 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer, Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet 370, 1609–1621 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jensen K. E., et al. , Parity as a cofactor for high-grade cervical disease among women with persistent human papillomavirus infection: A 13-year follow-up. Br. J. Cancer 108, 234–239 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Marks M., et al. , The association of hormonal contraceptive use and HPV prevalence. Int. J. Cancer 128, 2962–2970 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Marks M., et al. , Combined oral contraceptive use increases HPV persistence but not new HPV detection in a cohort of women from Thailand. J. Infect Dis. 204, 1505–1513 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Robinson D. P., Klein S. L., Pregnancy and pregnancy-associated hormones alter immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Horm. Behav. 62, 263–271 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Barkley M. S., Geschwind I. I., Bradford G. E., The gestational pattern of estradiol, testosterone and progesterone secretion in selected strains of mice. Biol. Reprod. 20, 733–738 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McGowan K. M., Colucci-Guyon E., Langa F., Babinet C., Coulombe P. A., Keratin 17 null mice exhibit age- and strain-dependent alopecia. Genes. Dev. 16, 1412–1422 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Roberts J. N., et al. , Genital transmission of HPV in a mouse model is potentiated by nonoxynol-9 and inhibited by carrageenan. Nat. Med. 13, 857–861 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cladel N. M., et al. , Mouse papillomavirus infection persists in mucosal tissues of an immunocompetant mouse strain and progress to cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 16932 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hopman A. H., Ramaekers F. C., Speel E. J., Rapid synthesis of biotin-, digoxigenin-, trinitrophenyl-, and fluorochrome-labeled tyramides and their application for In situ hybridization using CARD amplification. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 46, 771–777 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schindelin J., et al. , Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.