Abstract

Background

The use of spinal instrumentation is an established risk factor for postoperative infection. To address this problem, we prepared silver‐containing hydroxyapatite coating, consisting of highly osteoconductive hydroxyapatite interfused with silver. The technology has been adopted for total hip arthroplasty. Silver‐containing hydroxyapatite coating has been reported to have good biocompatibility and low toxicity. However, no studies about applying this coating in spinal surgery have addressed the osteoconductivity and direct neurotoxicity to the spinal cord of silver‐containing hydroxyapatite cages in spinal interbody fusion.

Aim

In this study, we evaluated the osteoconductivity and neurotoxicity of silver‐containing hydroxyapatite‐coated implants in rats.

Materials & Methods

Titanium (non‐coated, hydroxyapatite‐coated, and silver‐containing hydroxyapatite‐coated) interbody cages were inserted into the spine for anterior lumbar fusion. At 8 weeks postoperatively, micro‐computed tomography and histology were performed to evaluate the osteoconductivity of the cage. Inclined plane test and toe pinch test were performed postoperatively to assess neurotoxicity.

Results

Micro‐computed tomography data indicated no significant difference in bone volume/total volume among the three groups. Histologically, the hydroxyapatite‐coated and silver‐containing hydroxyapatite‐coated groups showed significantly higher bone contact rate than that of the titanium group. In contrast, there was no significant difference in bone formation rate among the three groups. Data of inclined plane and toe pinch test showed no significant loss of motor and sensory function in the three groups. Furthermore, there was no degeneration, necrosis, or accumulation of silver in the spinal cord on histology.

Conclusions

This study suggests that silver‐hydroxyapatite‐coated interbody cages produce good osteoconductivity and are not associated with direct neurotoxicity.

Keywords: hydroxyapatite, lumbar spinal interbody fusion, neurotoxicity, osteoconductivity, silver

Silver‐containing hydroxyapatite‐coated interbody cages demonstrated biological safety and high osteoconductivity. They may be useful for preventing infections related to spinal instrumentation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Lumbar interbody fusion (LIF) is a well‐established treatment for various spinal conditions such as degenerative diseases, trauma, infections, and tumors. 1 The number of elective lumbar fusion operations for degenerative diseases has increased by 62.3% from 122 679 in 2004 to 199 140 in 2015. 2 Consequently, several types of interbody cages have been developed and shown to be useful in circumferential fusion to improve segmental stability, spinal alignment, and interbody fusion. 3

Surgical site infection remains one of the most complicated problems in spinal surgery. 4 The postoperative infection rates for LIF range from 1.5% to 7.2%. 5 , 6 , 7 As the population ages, the number of spinal surgeries and associated infections is expected to increase. Infections related to spinal instrumentation increase patient morbidity and mortality and influence the quality of life after surgery, often resulting in long‐term disability and reoperations. 8 Therefore, all efforts should be directed at creating a favorable surgical environment that reduces the likelihood of harmful microorganism growth. 9

In the search for preventative measures against postoperative infections, silver‐containing hydroxyapatite (Ag‐HA) implant for total hip arthroplasty (THA) was developed and utilized. First, we focused on silver, which has a broad antibacterial spectrum and exhibits potent antibacterial activity. 10 Nonetheless, silver has been shown to exert cytotoxic effects on osteoblasts. 11 To overcome this problem, Noda et al. previously reported on the biocompatible and osteoconductive properties of hydroxyapatite (HA) and prepared Ag‐HA, which consists of highly osteoconductive HA interfused with silver using the thermal‐spray method. 12 Furthermore, the osteoconductivity of an Ag‐HA‐coated implant was investigated in rat tibia, and it was found that 3% Ag‐HA was appropriate and did not inhibit bone conduction. 13 The Ag‐HA coating markedly inhibited the adherence and proliferation of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and methicillin‐resistant S. aureus on the surface of implant materials in vitro and in vivo. 10 , 14 , 15 Moreover, Ag‐HA coating has good biocompatibility and low toxicity in vitro and in vivo. 14 , 16 , 17 After THA with the Ag‐HA‐coated implants, patients' activities of daily living improved significantly without any postoperative infections. 18

Based on these results, we decided to apply Ag‐HA coating to spinal instrumentation because of the higher infection rate and annual cost of treatment for postoperative infections compared to THA. 19 It is hypothesized that the use of Ag‐HA coating may aid in preventing instrumentation‐related postoperative spinal infections. To clarify its potential, several points require investigation. First, the osteoconductivity of the Ag‐HA coating cage should be assessed as a spinal interbody fusion implant. As the intervertebral space has less blood flow than the femoral marrow, 20 it is necessary to determine whether osteoinduction and osteoconduction around the Ag‐HA coating cage can be achieved between vertebral bodies. 18 , 21 Second, upon placing the Ag‐HA‐coated implants in the spine, the potential neurotoxicity of silver to the spinal cord is an important issue, 22 because some studies have shown that silver damages the brain and peripheral nerves. 23 A previous study examined the distribution of silver in organs and proved that there is no acute or subacute toxicity caused by silver. 17 However, there are no published studies that have examined the direct effects of implanting silver near the spinal cord.

We hypothesized that Ag‐HA coating cage will show osteoconductivity in the intervertebral space as described in a previous study 13 and not have association with direct neurotoxicity to the spinal cord in rats. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the osteoconductivity and direct neurotoxicity to the spinal cord of Ag‐HA coating on titanium (Ti) cages using the rat anterior LIF model.

2. METHODS

In this study, we used 48 10‐week‐old male Sprague–Dawley rats, weighing an average of 410.4 ± 19.8 g (range 368–464 g) (Kyudo Corp., Kumamoto, Japan). All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee at Saga University (approval numbers A2019‐058‐0 and A2019‐059‐0).

2.1. Coating and implants

Pure Ti pieces (length: 3 mm; width: 1.5 mm; height: 1.5 mm) were used as substrates for coating deposition. The surface was roughened using a sandblasting machine (TKX Corp., Osaka, Japan) with a 180‐grit aluminum oxide medium (Showa Denko K.K., Tokyo, Japan). Next, the pieces underwent 3‐min ultrasonication in ethanol. For the Ag‐HA group, powdered silver oxide (Kanto Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) was added to powdered HA (Kyocera Corporation, Shiga, Japan) to prepare 3% Ag‐HA, and the mixtures were stirred for 5 min in plastic bags. The HA powders, with or without silver oxide, were thermally sprayed onto the sandblasted surface using a flame‐spraying system (Oerlikon Metco Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to coat the surface. For the Ag‐HA group, the amount of silver on the surface of the cage was 0.009 mg. The temperature of the flame was approximately 2700°C. Each powder type was carried into the flame by a dry air carrier gas during spraying, melted, and then sprayed onto the piece. The coating process was conducted under normal atmospheric pressure. The cages were individually packaged and sterilized using a gamma sterilizer (JS‐8500, MDS Nordion, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

2.2. Animals

The rats were housed in standard cages (one rat per cage) in a temperature‐controlled room (20–25°C) with 12‐h light–dark cycles and acclimated for 7 days prior to use in a room in which a suitable environment was maintained. Standard rodent chow and water were used. Rats were randomly divided into the Ti group (n = 16), HA group (n = 16), and 3% Ag‐HA group (n = 16).

2.3. Surgical technique

Surgery was performed under intraperitoneal anesthesia using a mixture of anesthetic agents (0.375 mg/kg medetomidine, 2 mg/kg midazolam, and 2.5 mg/kg butorphanol), and 30 mg/kg cefazolin sodium (Fujita Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) was given intramuscularly. 24 The abdomen of each rat was cleaned with povidone‐iodine and dried. A midline longitudinal skin incision was made (Figure 1A). The iliolumbar vein was ligated (Figure 1B) and resected to retract the intestine to the right side of the rat to approach the iliopsoas muscle. To avoid bleeding from the iliopsoas muscle, a safe interval between the bilateral iliopsoas was used for anterior access to L3‐L4 or L4‐L5 (Figure 1C). The surgical site (L3‐L4 or L4‐L5) was selected based on intraoperative judgment of which was easier to fix. The dissection from L3‐L4 or L4‐L5 was performed only on the anterior side of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral disc to avoid lower‐limb paralysis from stimulation or nerve injury. The intervertebral disc and adjacent endplates of L3‐L4 or L4‐L5 were evacuated with diamond burrs. A Ti cage was inserted into the intervertebral space and fixed with a three‐hole microstraight plate with two cortical screws (JEIL Medical, Seoul, Korea) (Figure 1D). After confirming hemostasis, the peritoneum and skin were sutured. At 4–8 weeks postoperatively, the rats were euthanized, and the spinal segment was harvested.

FIGURE 1.

The surgical procedure of interbody fusion. (A) Median abdominal incision and transperitoneal approach. (B) Ligation of the left iliolumbar vein (white arrow). (C) Anterior access to L3–L4 (white arrow) through the safe interval between the bilateral iliopsoas muscles. (D) Fusion with a titanium piece and a plate with screws.

2.4. Functional assessment

The neurotoxicity of silver was assessed at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after surgery. One investigator evaluated all rats for sensory and motor nerve disturbances.

2.4.1. Inclined plane test

An inclined plane test was performed preoperatively and at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks postoperatively. The rats were placed on a flat plane in a horizontal position, with their heads facing the raised side of the board. 25 The angle of the inclined plane was increased at a rate of 2°/s. The test ended when the rats began to slide backward and the angle of the board was recorded. The performance was measured to the nearest 5° using a standard protractor. For analysis, the results of the three trials were averaged. 26

2.4.2. Toe pinch test

The toe pinch test was performed preoperatively and at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks postoperatively using a modified version of a previously described protocol. 27 , 28 Briefly, awake rats were gently restrained, and the volar aspect of their fifth toe was gently pinched with a pair of eye‐dressing forceps. Normal reactions to the toe pinch test included avoidance and attempts to bite the forceps. 29 The pain perception response to the pinch was scored based on the extent of hind limb withdrawal using the following three‐tier scoring system: 0, no response; 1, decreased response compared with normal (as indicated by a score of 2); 2, strong and prompt withdrawal of the hind limb that was indistinguishable from the response of the counterpart on the contralateral normal side. The assessment was repeated three times on each foot, and the highest score was selected to represent the response level. 30

2.5. Histological examination

Pathological examinations included evaluation of bone formation around the cage and the neurotoxicity of silver. For the assessment of bone formation, three samples from each group harvested together with the neighboring vertebral bone were demineralized with formic acid, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in resin. Sections (thickness, 5 μm) were cut, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined under a light microscope. Bone formation and contact were evaluated according to the method described by Yonekura et al. The bone formation index was calculated as the length of bone formation on the surface of the cage divided by the total length of the surface then multiplied by 100. 13 The bone contact index was calculated as the length of bone in direct contact with the surface of the implant divided by the total length of the implant, multiplied by 100. 13

Quantitative analysis of neurotoxicity was performed by examining one cross‐section per rat spinal cord in three harvested samples from the Ag‐HA group. It was performed only in the Ag‐HA group to examine the pathological changes caused by silver implantation near the spinal cord. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and observed for histological and morphological changes under an upright fluorescence microscope. Specifically, the presence of spinal cord degeneration, necrosis, and silver deposition were evaluated. 31

2.6. Radiographic examination

Three rats in each group were euthanized at 4 weeks postoperatively. The remaining rats were euthanized at 8 weeks postoperatively and the spinal segments were harvested. All harvested tissues were fixed with 3.6% neutral formalin and subsequently radiographed using a microfocus computed tomography (CT) (CT Lab GX130, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) scanning apparatus. The CT scan parameters were 70 kV, 228 μA, and 72 μm. Quantitative measures of the graft window included bone volume (BV), total volume (TV), and BV/TV (BV/TV expressed as a percentage [%]). Using a modified version of a previously described protocol, the region of interest was set to 0.24 mm around the cage, equally spaced from the cage's medial‐lateral, anterior–posterior, and cranial‐caudal boundaries. 3 Morphometric indices were calculated using software (VGSTUDIO MAX, Volume Graphics, Nagoya, Japan). Imaging evaluation was performed to determine whether osseointegration was achieved around the cage. Osseointegration was defined by the presence of lamellar bone formed as a result of bone remodeling around the implant and in close contact with the implant without any gaps. 32

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro software version 13.2.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The Ti, HA, and Ag‐HA groups were compared in terms of body weight, BV/TV, affinity index, inclined plane test, and toe pinch test using one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The normality distribution was evaluated with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. When the ANOVA results were significant, Tukey's honest significant difference was applied as a post hoc test. All numerical data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. General and skin condition after implantation

None of the animals showed signs of surgical site infections, skin disorders, or poor wound healing. The mean increases in body weight at 8 weeks were 175.9 ± 21.8 g, 186.6 ± 30.1 g, and 161.5 ± 33.7 g in the Ti, HA, and Ag‐HA groups, respectively. No significant differences in preoperative weight, weight at 8 weeks postoperatively, or weight change were identified among the three groups.

3.2. Functional assessment

3.2.1. Inclined plane test

The data for the inclined plane test are presented in Figure 2A. Comparison among the three groups indicated significant differences at 2 weeks postoperatively between the Ti and HA groups and between the Ti and Ag‐HA groups. There were no significant differences among the three groups at 1, 4, 6, or 8 weeks, postoperatively.

FIGURE 2.

(A)) Evaluation of inclined plane test at each observation point. “*” Significant difference at 2 weeks postoperatively between the titanium (Ti) and hydroxyapatite (HA) groups (p = 0.012). “†” Significant difference at 2 weeks postoperatively between the Ti and Ag‐HA groups (p = 0.008). (B) Evaluation of toe pinch test at each observation point.

3.2.2. Toe pinch test

The data for the toe pinch test are shown in Figure 2B. At 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks postoperatively, most of the rats showed normal responses, with no significant differences among the three groups. No rats exhibited motor or sensory changes or any behavioral changes such as aggressive behavior or squeaking.

3.3. Microfocus CT evaluation

Representative micro‐CT images in the sagittal plane view of the interbody device at 8 weeks postoperatively are shown in Figure 3. In the operated spinal segment, the newly formed bone tissue was observed in the discectomy space. There was no significant difference in the BV/TV among the three groups at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively (p = 0.941 and p = 0.258, Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Example of microcomputed tomography in the sagittal planes of the interbody fusion at 8 weeks. (A) Titanium (Ti) group, (B) hydroxyapatite (HA) group, (C) silver‐containing hydroxyapatite (Ag‐HA) group. Area within the yellow outlines indicates the region of interest in which bone morphometry on this plane is shown.

FIGURE 4.

Evaluation of microcomputed tomography assessment of spinal fusion. Bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) at 4 and 8 weeks, postoperatively.

3.4. Histology

Images of a tissue section around the cage taken in the sagittal plane are shown in Figures 5 and 6. The bone formation around the cage in the Ag‐HA group was at the same level as that in the Ti and HA groups. The mean affinity indices of bone formation in the Ti, HA, and Ag‐HA groups were 46.3%, 67.4%, and 73.4%, respectively. There was no significant difference among the groups (p = 0.163, Figure 7A). The mean affinity indices of bone contact in the Ti, HA, and Ag‐HA groups were 30.3%, 65.4%, and 69.0%, respectively. The bone contact rate around the cage in the Ag‐HA group and HA group was significantly higher than that in the Ti group (p = 0.018 and p = 0.009, Figure 7B).

FIGURE 5.

Photomicrographs taken in the sagittal plane of rat intervertebral disc stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at 8 weeks postoperatively. (A) titanium (Ti) group, (B) hydroxyapatite (HA) group, (C) silver‐containing hydroxyapatite (Ag‐HA) group (scale bar = 500 μm)

FIGURE 6.

Photomicrographs taken in the sagittal plane depicting an expanded field of view corresponding to Figure 5. Best, intermediate, and worst images of (A) titanium (Ti) group, (B) hydroxyapatite (HA) group, (C) silver‐containing hydroxyapatite (Ag‐HA) group (scale bar = 500 μm).

FIGURE 7.

(A) Evaluation of histology assessment of mean affinity index of bone formation. (B) Evaluation of histology assessment of mean affinity index of bone contact. “*” Significant difference between the titanium (Ti) and hydroxyapatite (HA) groups (p = 0.009). “†” Significant difference between the Ti and Ag‐HA groups (p = 0.018)

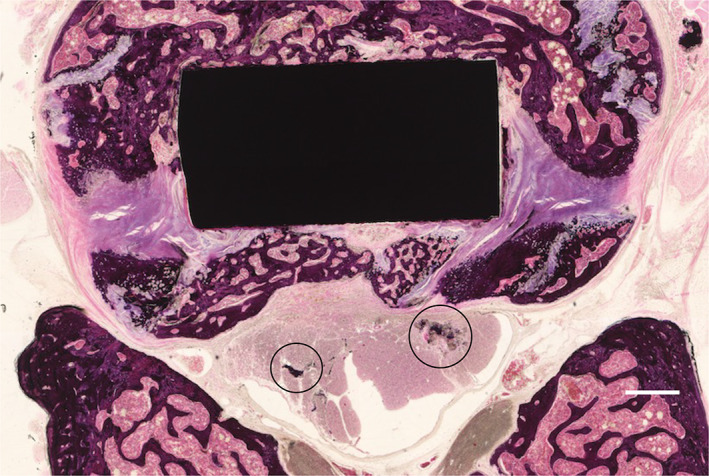

Images of the axial sections of the Ag‐HA group are shown in Figure 8. There was no obvious degeneration, necrosis, and accumulation of silver in the spinal cord of any of the three samples. Dark stained regions within the spinal cord appeared to be bone fragments that resulted from the sectioning process.

FIGURE 8.

Histologic section taken in the axial plane through the silver‐containing hydroxyapatite (Ag‐HA) coated cage. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain was used (scale bar = 500 μm). Dark stain regions are bone fragments that result from the sectioning process (black circles).

4. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate the osteoconductivity and neurotoxicity of Ag‐HA coating on Ti cages using the rat anterior LIF model. At 8 weeks after implantation into the lumbar intervertebral space, the Ag‐HA‐coated Ti cage showed osteoconductivity and bone formation as much as the uncoated Ti cage according to micro‐CT examination. In terms of pathological examination, the Ag‐HA coated cage and HA‐coated cage showed significantly higher bone contact rate than the Ti cage. As for direct neurotoxicity to the spinal cord, it was demonstrated that there were no neurotoxic effects caused by the Ag‐HA coating according to pathological and behavioral examination.

4.1. Osteoconductivity

The 3% Ag‐HA coating was prepared to combine antibacterial properties with good biocompatibility and osteoconductivity. 12 , 13 This coating has the properties of HA, induces the release of Ag ions, and has high antibacterial activity with inhibition of bacterial adhesion and low cytotoxicity in vitro. 12 , 14 In previous studies, 3% Ag‐HA implants placed in the intramedullary region of the lower limbs showed good osteogenesis and osseointegration in rats and humans. 13 , 16 , 21

With respect to interbody cages, McGilvray et al. investigated bone ingrowth of 3D‐porous Ti cages and polyetheretherketone cages. 3 However, the osteoconductivity of Ag‐HA‐coated cages in the intervertebral space has not yet been described. This is the first study to evaluate the osteoconductivity of Ag‐HA cages using a rat anterior LIF model.

There are important differences in the conditions for bone fusion between the lower extremities and the spine. Fusion procedures require physical manipulation of the intended site utilizing principles of vascularization, osteoinduction, and osteoconduction to maximize osteogenic potential 33 since the disc has few blood vessels and the cartilage endplate has no blood vessels of its own. 20 Moreover, there are fewer sources of osteoblasts for bone fusion in the intervertebral space than in the long bones. 33 Therefore, intervertebral body fixation involves heterotopic osteosynthesis in the disc space, which is a different mechanism from the healing process in fractures. 33 Interbody fusion requires the removal of disc tissue and cartilage endplates in the disc cavity to create access to the blood supply. 34 Thus, bone fusion in the intervertebral space is more difficult than in the long bones because of less ideal conditions.

In the past, there have been reports in rat tibia or canine pedicle of the lumbar spine that upon histological evaluation, HA has a higher bone contact rate around the implant than Ti. 13 , 35 However, no similar studies have compared the bone contact of Ti and HA coated implants in the intervertebral space. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that HA and Ag‐HA coated‐implants showed good osteoconductivity based on bone contact in the intervertebral space. In the present study, there was a significant difference in osteoconductivity between Ti and HA, Ti and Ag‐HA coated cage on pathological examination. The affinity indices of bone formation in the Ag‐HA group were the same as those in the HA group and Ti group. Also, the affinity indices of bone contact in the Ag‐HA group and HA group were significantly higher than that in the Ti group. Yonekura et al. reported that the 3% Ag‐HA coating was shown to have good osteoconductivity based on the affinity indices in the rat tibia, 13 a similar finding to that of the present study. It was observed that the Ag‐HA coated implant showed good osteoconductivity in the intervertebral space as well as in the long bone.

4.2. Neurotoxicity

It has been demonstrated previously that silver causes neurotoxic effects. 36 , 37 , 38 Westhofen et al. reported on an individual with skin discoloration, progressive dizziness, and decreased sensation after prolonged oral administration of silver nitrate (0.53 g/day for 9 years) to treat oral fungal infections and confirmed silver deposition on peripheral nerves by light and electron microscopy. 37 The Westhofen et al. study was conducted over 9 years, whereas the current study lasted only 8 weeks. Therefore, this study confirmed only the short‐term effects, and did not verify the long‐term effects in the past study. 37 Horner et al. also reported that silver compounds administered to mice caused toxicity resulting in increased excitability and ataxia. 38 Hardes et al. observed that the cytotoxic effect of silver appears to be dose‐dependent in humans. 39 However, no consistent data have been reported concerning the amount of silver associated with neurotoxicity.

Small amounts of orally ingested silver are absorbed by the intestine and transported as a complex formed by plasma proteins. Eventually, most of the silver is excreted by the liver and eliminated via feces. 36 However, silver also accumulates intracellularly in the brain as well as in the kidney, spleen, and liver. 17 Tsukamoto et al. evaluated silver concentrations in the serum, brain, liver, kidneys, and spleen in which 2% Ag‐HA coating implants were inserted into the rat tibia. No acute or subacute toxicity of silver was shown. 17 Also, in a clinical study of Ag‐HA coated implant for THA, no adverse reaction to silver was noted. 18

In this study, there was no obvious loss of movement or sensation in the lower limbs of rats at 8 weeks postoperatively, and no degeneration of the spinal cord was confirmed by histology. Therefore, the amount of silver in the cage, 0.009 mg, seems to be low enough to avoid evidence of direct neurotoxicity to the spinal cord. Based on the average body weight of the rats used in this study, the equivalent amount in humans would be approximately 1.096 g of silver per 50 kg of body weight for the silver volume in the interbody cage. According to Eto et al., the maximum amount of silver contained in the Ag‐HA implant for THA was 2.9 mg, and no adverse reactions were attributable to silver. 18 This study suggests that Ag‐HA coated cage is safe to use in rats, but further research is necessary to evaluate its safety in humans.

4.3. Experimental approach in rats

In this study, we used a transperitoneal approach for the rat lumbar anterior fusion. In basic research on lumbar spinal interbody cages, using small animals is technically difficult because of their size. In this study, we tried a rat lumbar anterior fusion approach based on previous reports. 40 , 41 Several small animal studies have examined lumbar posterolateral fusion 42 , 43 and coccygeal interbody fusion, 44 , 45 but the former was not LIF using lumbar spinal interbody cages and the latter demonstrated different biomechanics of LIF. In basic research on lumbar spinal interbody cages, pigs (Danish Landrace), sheep (Merinolandschaf), and dogs are commonly used; however, keeping these animals is complex and subject to legal restrictions. 46 , 47 , 48 The rat model is economical, with fewer ethical issues than medium‐ and large‐size models. Therefore, we believe that it can also be used for basic research using an anterior intervertebral approach. The use of rat models for the study of spinal fusion may provide measurable biological and mechanical outcomes to promote new technology for bone formation and predict the human response to treatment.

4.4. Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the surgical procedure in this model was different from LIF in humans because the bony endplates were destroyed to insert the interbody cage into the rats' narrow disc space. Destroying the endplates may improve the blood supply as well as osteogenic cells, potentially improving the fusion rate 44 ; further studies are warranted to clarify this association. In this study, the Ag‐HA cage could not be made any smaller due to the technology of thermal spraying, so the endplates had to be destroyed and inserted to fit the cage. Second, there are technical problems with the usage of CT imaging and histological evaluation to measure bone growth at the implant interface. Due to dissimilar stiffness of the metal and tissue, CT imaging is subject to a metal artifact and histology is subject to artifacts at the metal/tissue interface. Considering these issues, it appears that the osteoconductivity of Ag‐HA is similar to that of HA alone, though the evidence is weak due to these limitations. Third, the neurotoxicity of silver has been evaluated only at low concentrations. In this study, owing to the small size of the interbody cages, the amount of silver that could be sprayed was limited. However, since the antimicrobial properties and safety of 3% Ag‐HA have been evaluated in previous studies, 10 , 13 , 15 we decided to evaluate the safety of 3% Ag‐HA in the spine as well. Fourth, the neurotoxicity of silver was evaluated only in functional assessment and histological analysis of one cross‐section. Since the silver can accumulate in the brain and other organs, 17 the accumulation of silver should be investigated in the future. Fifth, the antibacterial activity of Ag‐HA coating in the intervertebral space is yet to be assessed. Although the antibacterial activity of 3% Ag‐HA coating in rat subcutaneous and tibia has been shown in the past, 10 , 15 it will be necessary to assess the antibacterial activity in the intervertebral space in the future.

4.5. Conclusion

This study suggests that the 3% Ag‐HA‐coated interbody cage produces good osteoconductivity and is not associated with direct neurotoxicity to the spinal cord in rats. The 3% Ag‐HA‐coated interbody cage is a biologically safe technology that may be useful for preventing postoperative infections related to spinal instrumentation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Takema Nakashima, Akira Hashimoto, and Sakumo Kii made substantial contributions to the research design or to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. Tadatsugu Morimoto, Masatsugu Tsukamoto, and Mitsugu Todo drafted the manuscript and/or critically revised it. Hiroshi Miyamoto, Motoki Sonohata, and Masaaki Mawatari provided approval for the submitted and final versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI number 19K12786. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party directly or indirectly related to the subject of this article. The funding source had no role in the design of the study, in the analysis and interpretation of the results, or in the writing and submission of the manuscript for publication.

Nakashima, T. , Morimoto, T. , Hashimoto, A. , Kii, S. , Tsukamoto, M. , Miyamoto, H. , Todo, M. , Sonohata, M. , & Mawatari, M. (2023). Osteoconductivity and neurotoxicity of silver‐containing hydroxyapatite coating cage for spinal interbody fusion in rats. JOR Spine, 6(1), e1236. 10.1002/jsp2.1236

Funding information Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant/Award Number: 19K12786

REFERENCES

- 1. Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Malham G, et al. Lumbar interbody fusion: techniques, indications and comparison of interbody fusion options including PLIF, TLIF, MI‐TLIF, OLIF/ATP, LLIF and ALIF. J Spine Surg. 2015;1(1):2‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martino ADI, Papalia R, Albo E, et al. Infection after spinal surgery and procedures. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(2):173‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGilvray KC, Easley J, Seim HB, et al. Bony ingrowth potential of 3D‐printed porous titanium alloy: a direct comparison of interbody cage materials in an in vivo ovine lumbar fusion model. Spine J. 2018;18(7):1250‐1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yin D, Liu B, Chang Y, Gu H, Zheng X. Management of late‐onset deep surgical site infection after instrumented spinal surgery. BMC Surg. 2018;18(1):4‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pappou IP, Papadopoulos EC, Sama AA, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP. Postoperative infections in interbody fusion for degenerative spinal disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:120‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JS, Ahn DK, Chang BK, Il LJ. Treatment of surgical site infection in posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Asian Spine J. 2015;9(6):841‐848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mirovsky Y, Floman Y, Smorgick Y, et al. Management of deep wound infection after posterior lumbar interbody fusion with cages. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20(2):127‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Margaryan D, Renz N, Bervar M, et al. International journal of antimicrobial agents spinal implant‐associated infections: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(4):106116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Romanò CL, Tsuchiya H, Morelli I, Battaglia AG, Drago L. Antibacterial coating of implants: are we missing something? Bone Jt Res. 2019;8(5):199‐206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shimazaki T, Miyamoto H, Ando Y, et al. In vivo antibacterial and silver‐releasing properties of novel thermal sprayed silver‐containing hydroxyapatite coating. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010;92(2):386‐389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Albers CE, Hofstetter W, Siebenrock KA, Landmann R, Klenke FM. In vitro cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on osteoblasts and osteoclasts at antibacterial concentrations. Nanotoxicology. 2013;7(1):30‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noda I, Miyaji F, Ando Y, et al. Development of novel thermal sprayed antibacterial coating and evaluation of release properties of silver ions. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;89(2):456‐465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yonekura Y, Miyamoto H, Shimazaki T, et al. Osteoconductivity of thermal‐sprayed silver‐containing hydroxyapatite coating in the rat tibia. J Bone Jt Surg Ser B. 2011;93(5):644‐649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ando Y, Miyamoto H, Noda I, et al. Calcium phosphate coating containing silver shows high antibacterial activity and low cytotoxicity and inhibits bacterial adhesion. Mater Sci Eng C. 2010;30(1):175‐180. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akiyama T, Miyamoto H, Yonekura Y, et al. Silver oxide‐containing hydroxyapatite coating has in vivo antibacterial activity in the rat tibia. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(8):1195‐1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eto S, Miyamoto H, Shobuike T, et al. Silver oxide‐containing hydroxyapatite coating supports osteoblast function and enhances implant anchorage strength in rat femur. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(9):1391‐1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsukamoto M, Miyamoto H, Ando Y, et al. Acute and subacute toxicity in vivo of thermal‐sprayed silver containing hydroxyapatite coating in rat tibia. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:902343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eto S, Kawano S, Someya S, Miyamoto H, Sonohata M, Mawatari M. First clinical experience with thermal‐sprayed silver oxide‐containing hydroxyapatite coating implant. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(7):1498‐1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schwarz EM, Parvizi J, Gehrke T, et al. 2018 international consensus meeting on musculoskeletal infection: research priorities from the general assembly questions. J Orthop Res. 2019;37(5):997‐1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raj PP. Intervertebral disc: anatomy‐physiology‐pathophysiology‐treatment. Pain Pract. 2008;8(1):18‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawano S, Sonohata M, Eto S, Kitajima M, Mawatari M. Bone ongrowth of a cementless silver oxide‐containing hydroxyapatite‐coated antibacterial acetabular socket. J Orthop Sci. 2019;24(4):658‐662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lansdown ABG. Critical observations on the neurotoxicity of silver. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2007;37(3):237‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gonzalez‐Carter DA, Leo BF, Ruenraroengsak P, et al. Silver nanoparticles reduce brain inflammation and related neurotoxicity through induction of H 2 S‐synthesizing enzymes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(3):1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oksuz E, Deniz FE, Gunal O, et al. Which method is the most effective for preventing postoperative infection in spinal surgery? Eur Spine J. 2016;25(4):1006‐1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abou‐Donia MB, Goldstein LB, Bullman S, et al. Imidacloprid induces neurobehavioral deficits and increases expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the motor cortex and hippocampus in offspring rats following in utero exposure. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71(2):119‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dhouib IB, Annabi A, Doghri R, et al. Neuroprotective effects of curcumin against acetamiprid‐induced neurotoxicity and oxidative stress in the developing male rat cerebellum: biochemical, histological, and behavioral changes. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24(35):27515‐27524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kovačič U, Žele T, Osredkar J, Sketelj J, Bajrović FF. Sex‐related differences in the regeneration of sensory axons and recovery of nociception after peripheral nerve crush in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2004;189(1):94‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ma H, Xu T, Xiong X, et al. Effects of glucose administered with lidocaine solution on spinal neurotoxicity in rats. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(11):20638‐20644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee JR, Lee PB, Choe G, et al. Evaluation of the neurological safety of epidurallyadministered pregabalin in rats. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;62(1):57‐65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang XS, Chen X, Gu TW, Wang YX, Mi DG, Hu W. Axonotmesis‐evoked plantar vasodilatation as a novel assessment of C‐fiber afferent function after sciatic nerve injury in rats. Neural Regen Res. 2019;14(12):2164‐2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kishimoto T, Bollen AW, Drasner K. Comparative spinal neurotoxicity of prilocaine and lidocaine. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(5):1250‐1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brånemark R, Öhrnell LO, Nilsson P, Thomsen P. Biomechanical characterization of osseointegration during healing: an experimental in vivo study in the rat. Biomaterials. 1997;18(14):969‐978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reid JJ, Johnson JS, Wang JC. Challenges to bone formation in spinal fusion. J Biomech. 2011;44(2):213‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Giannicola G, Ferrari E, Citro G, et al. Graft vascularization is a critical rate‐limiting step in skeletal stem cell‐mediated posterolateral spinal fusion. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4:273‐283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hasegawa T, Inufusa A, Imai Y, Mikawa Y, Lim TH, An HS. Hydroxyapatite‐coating of pedicle screws improves resistance against pull‐out force in the osteoporotic canine lumbar spine model: a pilot study. Spine J. 2005;5(3):239‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skalska J, Struzyńska L. Toxic effects of silver nanoparticles in mammals ‐ does a risk of neurotoxicity exist? Folia Neuropathol. 2015;53(4):281‐300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Westhofen MI, Schäfer H. Generalizedargyrosis in man: neurotological, ultrastructural and X‐ray microanalytical findings. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1986;243(1986):260‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Horner HC, Roebuck BD, Smith RP. Acute toxicity of some silver salts of sulfonamides in mice and the efficacy of penicillamine in silver poisoning. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1983;6(3):267‐277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hardes J, Ahrens H, Gebert C, et al. Lack of toxicological side‐effects in silver‐coated megaprostheses in humans. Biomaterials. 2007;28(18):2869‐2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marc‐Antonie R, Elisa CB, Jeffrey CL. Ventral approach to the lumbar spine of the Sprague‐Dawley rat. Lab Anim. 2004;33:43‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kang Y, Liu C, Wang M, Wang C, Yan YG, Wang WJ. A novel rat model of interbody fusion based on anterior lumbar corpectomy and fusion (ALCF). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Son S, Yoon SH, Kim MH, Yun X. Activin a and BMP chimera (AB204) induced bone fusion in osteoporotic spine using an ovariectomized rat model. Spine J. 2020;20(5):809‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rodríguez‐Vázquez M, Ramos‐Zúñiga R. Chitosan‐hydroxyapatite scaffold for tissue engineering in experimental lumbar laminectomy and posterolateral spinal fusion in wistar rats. Asian Spine J. 2020;14(2):139‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Okada R, Kaito T, Ishiguro H, et al. Assessment of effects of rhBMP‐2 on interbody fusion with a novel rat model. Spine J. 2020;20(5):821‐829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yeh YC, Yang CC, Tai CL, et al. Characterization of a novel caudal vertebral interbody fusion in a rat tail model: an implication for future material and mechanical testing. Biom J. 2017;40(1):62‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kroeze RJ, Smit TH, Vergroesen PP, et al. Spinal fusion using adipose stem cells seeded on a radiolucent cage filler: a feasibility study of a single surgical procedure in goats. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(5):1031‐1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grgurevic L, Erjavec I, Gupta M, et al. Autologous blood coagulum containing rhBMP6 induces new bone formation to promote anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) and posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF) of spine in sheep. Bone. 2020;138(4):115448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kaito T, Mukai Y, Nishikawa M, et al. Dual hydroxyapatite composite with porous and solid parts: experimental study using canine lumbar interbody fusion model. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006;78(2):378‐384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]