Abstract

Healthcare-associated infections pose one of the most severe threats to patients’ health and remain a major challenge for healthcare providers globally. Among healthcare-associated infections, surgical site infection is one of the most commonly reported infections. It remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality across the world. The aim of this study was to provide a pooled incidence of surgical site infection among patients on a regional and global scale. This study was conducted under the PRISMA guidelines developed for systematic review and meta-analysis. The studies were searched using electronic databases (SCOPUS, PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Google Scholar, DOAJ, and MedNar) from June 1st, 2022 to August 4th, 2022, using Boolean logic operators (AND, OR, and NOT), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and keywords. The quality of the study was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Assessment tool to determine the relevance of each included article to the study. A comprehensive meta-analysis version 3 was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of surgical site infections among the patients. A total of 2124 articles were retrieved from the included electronic databases. Finally, after applying inclusion criteria, 43 articles conducted in 39 countries were included in the current study. The global pooled incidence of SSI was found to be 2.5% (95% CI: 1.6, 3.7). Based on the subgroup analysis by WHO region and survey period, the incidence of SSI was 2.7% (95% CI: 2.2, 3.3%) and 2.5% (95% CI: 1.8, 3.5%), respectively. The highest incidence was reported in the African Region (7.2% [95% CI: 4.3, 11.8%]) and among studies conducted between 1996 and 2001 (2.9% [95% CI: 0.9%, 8.8%]). This study revealed that the overall pooled incidence of SSI was 2.5%. SSI estimates varied among the WHO regions of the world. However, the highest incidence (2.7%) was observed in the African region. This indicates that there is a need to implement safety measures, including interventions for SSI prevention to reduce SSI and improve patient safety.

Keywords: hospital acquired infection, nosocomial infection, surgical site infection, patient, patient safety, global

What do we already know about this topic?

Surgical site infection (SSI) continues to be a health concern across the world. Until this study, there was no study that provided a global and WHO’s region incidence of SSI.

How does your research contribute to the field?

This study revealed that the overall pooled incidence of surgical site infection was 2.5%. Surgical site infection estimates varied among the WHO regions of the world and were high in the African region, accounting for 7.2%. The incidence of surgical site infection decreased from 2.9% in 1996 to 2.8% in 2022.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

The findings of the current study can be used by national and international concerned agencies or organizations to take appropriate prevention measures and for planning and implementing effective SSI prevention and control programs, which can contribute to better health service provision across the world.

Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections (HAI) pose one of the most severe threats to patients’ health and remain a major challenge for healthcare service providers globally.1 Mainly, these infections are caused by antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms.2 HAI is the major cause of morbidity and mortality3-5 and is associated with clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic procedures.6,7

Although the global burden of HAI remains unknown due to a lack of reliable data, it is estimated that hundreds of millions of patients are affected by HAIs annually. Not only does this result in significant mortality, but it also results in service or financial losses for healthcare systems. Currently, there is no country free from the HAI burden and antimicrobial resistance.2 Furthermore, approximately 3 million healthcare professionals around the world are affected by HAI every year.8

Among HAI, surgical site infection (SSI) is one of the most commonly reported HAI.9 Surgical site infections remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for approximately one-fifth of all HAI.10 More than 30% of the HAI are SSI, defined as infections related to operative procedures that occur at or near surgical incisions (within 30 days of the procedure) or within 90 days (if prosthetic materials are implanted at surgery).11

Surgical site infections have a wide range of consequences for both patients and healthcare systems, including discomfort, extended hospital stays, and missed work.12,13 For example, SSIs approximately increase the length of hospital stays by 10 days.13 Similarly, it increased the cost of therapy and the cost of an operation by 300% to 400%12,13 and increased the rate of hospital readmissions and jeopardized health outcomes.14 However, as a result of poor infection prevention practices, SSI is substantially higher in low-and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries.2,15,16 To reduce this problem, World Health Organization’s (WHO)2 global guideline on preventing surgical site infection should be disseminated and implemented. These guidelines address surgical site infection prevention and risk factors, SSI surveillance, the importance of a clean environment in the operating room, and the decontamination of medical devices and surgical instruments, as well as evidence-based recommendations on measures for the prevention of surgical site infection.2

Besides these problems, there is limited evidence regarding the pooled global and regional incidence of SSI among patients. A few recent studies have been conducted on the specified region or countries, anatomical location, stage of diagnosis, outcome, and types of diagnosis.17-20

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the regional and global incidence of SSI among patients. It can be used by both national and international concerned agencies or organizations for planning and implementing effective SSI prevention and control programs, which can contribute to better health service provision across the world.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline was used to perform this systematic review and meta-analysis.21

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria: The studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis:

Study population: Patients admitted to the health facility were a study population.

Outcomes: The study reported quantitative outcomes (magnitude, frequency, rate, or incidence of surgical site infection). There is no limitation based on the types of surgery.

Language: Articles written in English.

Types of articles: A peer-reviewed full text, original, and published articles.

Publication/survey year: Articles conducted and published at any time (not limited)

Study region or country: Not specified (not limited).

Exclusion criteria:

The study did not report quantitative outcomes, case series, review articles, reports, conference abstracts, opinions, articles with a high risk of bias (low quality), and articles not available in full texts were excluded from the current study.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

The studies were searched using electronic databases (SCOPUS, PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Google Scholar, DOAJ, and MedNar) from June 1 to August 4, 2022. A combination of Boolean logic operators (AND, OR, and NOT), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and keywords (healthcare facility, nosocomial infection, surgical site infection, patients, hospital-acquired infection, healthcare associated infection) were used to retrieve the articles. The search strategies employed in the current study, particularly for PubMed are provided in a Supplemental File (Supplemental File 1). Then, the keywords and index terms were checked across the included databases. The search for the reference list of included articles was conducted to retrieve further articles.

Study Selection

The studies that were included in the current meta-analysis were identified using a PRISMA flow chart that shows the number of articles included and excluded from the study. Duplicate articles were removed using the ENDNOTE software version X5 following the search for articles from selected electronic databases (Thomson Reuters, USA). The authors (DAM, AA, AA, IM, AM, BM, and FA) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies to determine their eligibility by applying the inclusion criteria. The authors further evaluated the full text of the relevant articles independently.

Disagreements between the authors (DAM, AA, AA, IM, AM, BM, and FA) were solved by discussion after repeating the same procedures. Finally, articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in this study.

Data Extraction

The authors (DAM, AA, AA, IM, AM, BM, and FA) independently extracted the data from the included articles. The Microsoft Excel 2016 format was developed by the authors and used to extract the data from the included articles under the following headings: author; publication year; survey year; country where the study was conducted; sample size; and primary outcomes (incidence of surgical site infections) among the patients. Finally, all the data required for the current study were extracted from the eligible studies.

Quality Assessment

The included studies were subjected to quality assessment by the authors (DAM, AA, AA, IM, AM, BM, and FA) using a standardized critical appraisal tool (Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Assessment Tools).22 Then, the articles were evaluated by the authors (DAM, AA, AA, IM, AM, BM, and FA) to confirm their relevance to the study and the quality of the work.

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Assessment Tools used in the current study have the following evaluation criteria, an appropriate sampling frame, proper sampling technique, adequate sample size, description of the study subject and setting description, sufficient data analysis, use of valid methods for the identified conditions, valid measurement for all participants, use of appropriate statistical analysis, and an adequate response rate.

Each parameter was then evaluated as satisfied or not satisfied. If a parameter was not satisfied, it was assigned a value of 0; otherwise, it was assigned a value of 1. Based on the total score, each article was graded as high quality (85% or above), moderate (60%-85% score), or low quality (60% score). Disagreement between the authors was solved by discussion after repeating the same procedures.

Statistical Procedures and Data Analysis

A systematic review and meta-analysis were used to summarize data on SSI by pooling together the findings of studies reporting the incidence of SSI across the world. The pooled incidence of SSI among patients was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.0 statistical software. The pooled incidence of the SSI among patients in the healthcare facility was determined and visualized using a forest plot and a random-effects model.

The I-squared test (I2 statistics) was used to evaluate the heterogeneity between the included articles. The level of heterogeneity was then classified as no heterogeneity (0%), low (25%-50%), moderate (50%-75%), and high heterogeneity (>75%).23 A random-effects model was used to analyze and report the data. Furthermore, subgroup analysis was conducted based on the survey period, WHO region, and study areas/regions. A sensitivity analysis was done to determine differences in pooled effects by dropping studies that were found to influence the summary estimates.

Results

Study Selection

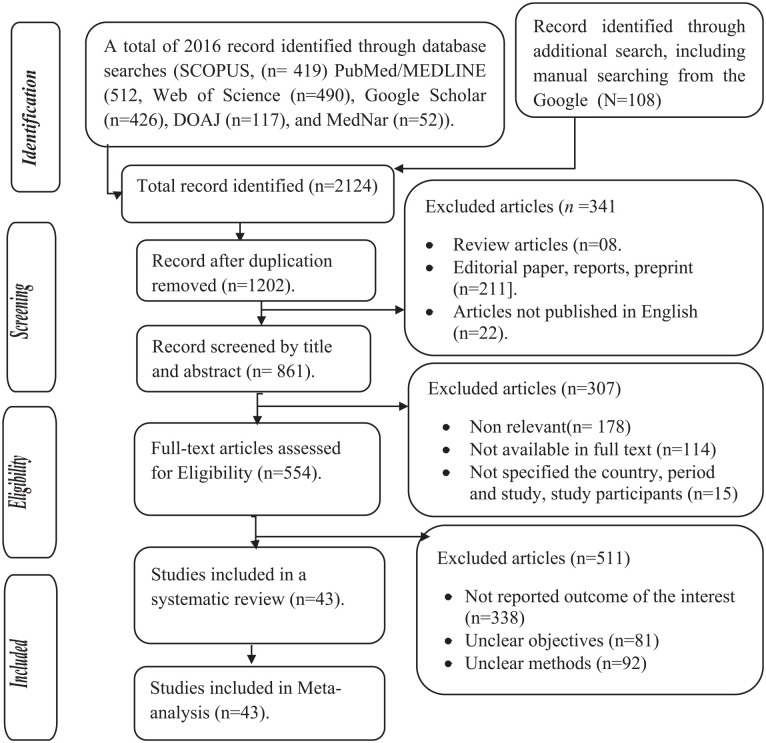

A total of 2124 articles were retrieved from the included electronic databases and manual searches. Then, 1430 duplicate articles were excluded. Of the 1202 articles, 341 were excluded based on their titles and abstracts. Furthermore, 861 full-text studies were further assessed to determine their eligibility, of which 307 were excluded. Furthermore, 554 were evaluated based on the objectives, methods, and outcome of interest by reading all the contents of the articles. Finally, a total of 43 articles were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process of included articles for systematic review and meta-analysis, 2022.

Study Characteristics

This systematic review and meta-analysis included a total of 43 studies conducted on 798 712 patients (ranging from 10524 to 633 99025 study participants). Among the included studies, 5 were conducted in China,25-29 3 in Ethiopia,30-32 3 in the USA,33-35 2 in Switzerland,36,37 2 in Benin,38,39 2 in Germany,40,41 2 in Italy,42,43 2 in Iran,44,45 and 2 in Poland.46,47

One in each of France,48 Turkey,49 Cuba,50 Thailand,51 Albania,52 Malawi,24 Saudi Arabia,53 Ghana,54 Nigeria,55 Argentina,56 Rwanda,57 Tanzania,58 Georgia,59 South Africa,60 Tunisia,61 Nepal,62 Herzegovina,63 Australia,64 India,65 and Cameroon.66 Among the included studies, the highest incidence of SSI was reported in Tanzania,58 which accounted for 26.0%. The lowest incidence of SSI was reported in China27 which accounted for 0.2%, followed by another study conducted in China28 and France,48 which reported 0.22% and 0.3%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overall Characteristics of the Articles Included in the Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, 2022.

| Author | Sample size | Survey year | Publication year | Incidence | Country | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pittet et al36 | 1349 | 1996 | 1999 | 3.93 | Switzerland | Moderate |

| Ahoyo et al38 | 3130 | 2012 | 2014 | 5.96 | Benin | Moderate |

| Girard et al48 | 286 | 2001 | 2006 | 0.3 | France | Moderate |

| Esen and Leblebicioglu49 | 236 | 2004 | 2001 | 8.05 | Turkey | Moderate |

| Izquierdo-Cubas et al50 | 4240 | 2004 | 2008 | 1.9 | Cuba | Moderate |

| Danchaivijitr et al51 | 9865 | 2006 | 2007 | 0.71 | Thailand | Moderate |

| Faria et al52 | 968 | 2003 | 2007 | 4.7 | Albania | Low |

| Nash et al33 | 11 879 | 2006 | 2011 | 4.1 | USA | Low |

| Bunduki et al24 | 105 | 2020 | 2021 | 3.81 | Malawi | Low, not specified |

| Olsen et al34 | 1605 | 1999-2001 | 2008 | 5.047 | USA | Low |

| Huang et al26 | 6717 | 2014-2018 | 2020 | 0.43 | China | Low |

| Balkhy et al53 | 562 | 2003 | 2006 | 2.3 | Saudi Arabia | Low |

| Labi et al54 | 2107 | 2016 | 2019 | 2.85 | Ghana | Low |

| Askarian et al44 | 3450 | 2008-2009 | 2012 | 2.4 | Iran | Low |

| Abubakar55 | 321 | 2019 | 2020 | 5.0 | Nigeria | Low |

| Zotti et al42 | 9467 | 2000 | 2004 | 0.7 | Italy | Moderate |

| Gentili et al43 | 6263 | 2013-2018 | 2020 | 1.42 | Italy | Low |

| Durlach et al56 | 4249 | 2008 | 2012 | 2.9 | Argentina | Low |

| Mukamuhirwa et al57 | 122 | 2017 | 2022 | 8.2 | Rwanda | Moderate |

| Mühlemann et al37 | 520 | 2000 | 2004 | 3.2 | Switzerland | Moderate |

| Ott et al40 | 1047 | 2010 | 2013 | 3.44 | Germany | Moderate |

| Lee et al29 | 1021 | 2005 | 2006 | 1.1 | Hong Kong | Low |

| Mawalla et al58 | 250 | 2009-2010 | 2011 | 26 | Tanzania | Low |

| Dégbey et al39 | 384 | 2019-2020 | 2021 | 7.81 | Benin | Moderate |

| Brown et al59 | 872 | 2000-2002 | 2007 | 16.7 | Georgia | Low |

| Mezemir et al30 | 249 | 2016 | 2020 | 24.6 | Ethiopia | Low |

| Motbainor et al31 | 238 | 2018 | 2020 | 0.84 | Ethiopia | Low |

| Strasheim et al60 | 332 | 2013 | 2015 | 19.6 | South Africa | Low |

| Azeze and Bizuneh32 | 383 | 2016-2017 | 2019 | 7.8 | Ethiopia | Low |

| Kołpa et al46 | 1849 | 2016-2017 | 2018 | 1.8 | Poland | Low |

| Ghali et al61 | 2729 | 2012-2020 | 2021 | 2.34 | Tunisia | Low |

| Shrestha et al62 | 300 | 2016 | 2020 | 4.67 | Nepal | Low |

| Magill et al35 | 851 | 2009 | 2012 | 2.12 | USA | Moderate |

| Arefian et al41 | 62 154 | 2011-2014 | 2019 | 1.73 | Germany | Low |

| Russo et al64 | 2767 | 2018 | 2019 | 3.6 | Australia | Low |

| Zhang et al27 | 4029 | 2012-2014 | 2016 | 0.2 | China | Low |

| Zhang et al25 | 633 990 | 2013-2017 | 2019 | 0.36 | China | Low |

| Custovic et al63 | 834 | 2010 | 2014 | 0.84 | Herzegovina | Moderate |

| Wang et al28 | 1347 | 2013-2015 | 2019 | 0.22 | China | Low |

| Heydarpou et al45 | 6000 | 2011-2014 | 2017 | 1.18 | Iran | Moderate |

| Sahu et al65 | 6864 | 2013-2014 | 2016 | 0.54 | India | Low |

| Nouetchognou et al66 | 307 | 2013-2014 | 2016 | 2.61 | Cameroon | Low |

| Tomczyk-Warunek et al47 | 2474 | 2018-2020 | 2021 | 0.4 | Poland | Low |

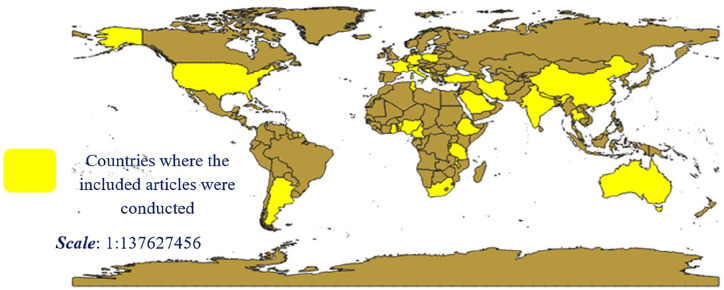

Among the included studies, the majority of the studies were conducted in developing countries. In general, the included articles were conducted in 29 country’s of the world (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Countries of the world where the included articles were conducted.

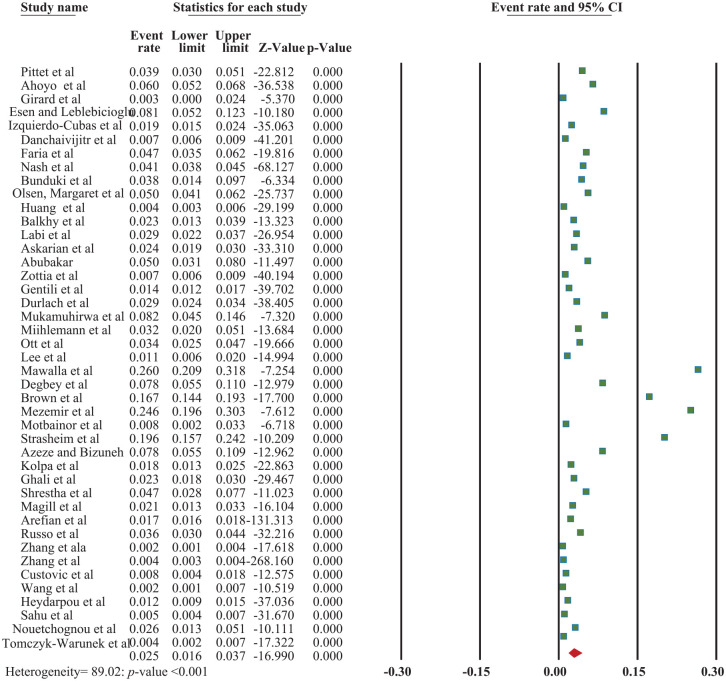

Pooled Incidence of Surgical Site Infection

Regarding the outcome of the studies included in the current study, there was no limitation or exclusion of the studies based on the types of surgery. The worldwide incidence of surgical site infection among patients was found to be 2.5% (95% CI: 1.6, 3.7) with a P-value of <.001; I2 = 89.02 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The forest plot shows an overall pooled incidence of surgical site infections among patients, 2022.

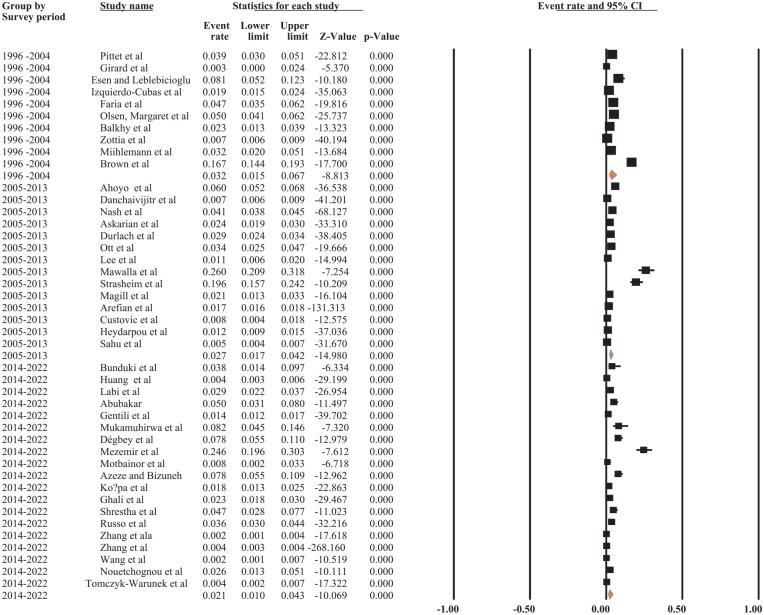

Based on subgroup analysis by survey year, studies conducted between 2014 and 2022 had the lowest pooled incidence of surgical site infections among patients (0.4% [95% CI: 0.2, 0.7%]), while studies conducted between 1996 and 2004 had the highest (3.2% [95% CI: 1.5%, 6.7%]). The results of the current finding indicated that the incidence of SSI was declining from 1996 to 2022 (3.2%-0.4%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The forest plot shows the subgroup analysis of the pooled incidence of SSI among patients based on survey period/year, 2022.

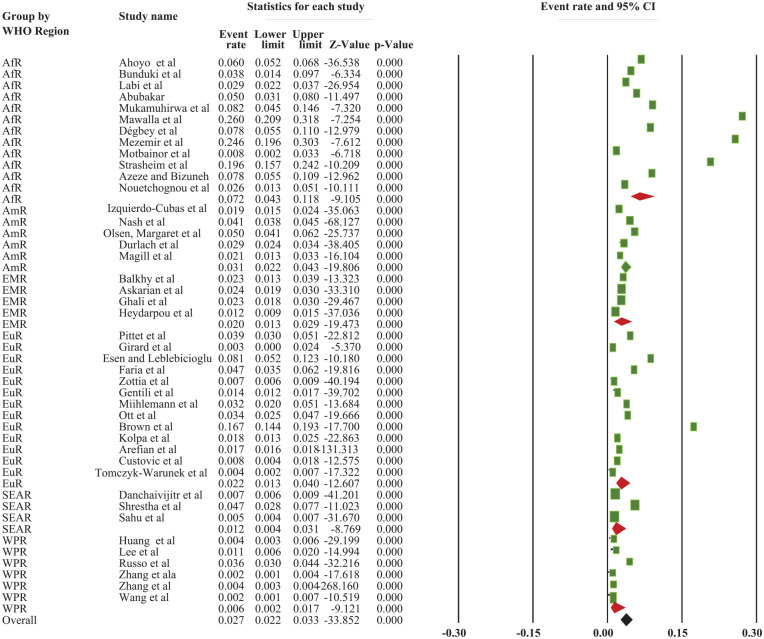

Based on the World Health Organization’s Region, the overall pooled incidence of SSI was 2.7% (95% CI: 2.2, 3.3%). The highest incidence was reported in the African Region, which accounted for 7.2% (95% CI: 4.3, 11.8%), whereas the lowest incidence was reported in the Western Pacific Region, at 0.6% (95% CI: 0.2, 1.7%) (Supplemental File 2; Figure 2) and (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The forest plot shows the subgroup analysis of the pooled incidence of SSI among patients based on WHO Region of the world, 2022.

Keys = ArR = African Region = AmR = American Region = EMR = Eastern Mediterranean Region = SEAR = South East Asian Region; WPR = Western Pacific Region; EuR = European Region.

Sensitivity Analysis Results

The sensitivity analysis was conducted by dropping the outcomes or samples expected to influence the pooled incidence of SSI. However, no substantial difference was observed in the prevalence of SSI among patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity Analysis Based on Sample Size and Study Outcomes Expected to Effect the Pooled Prevalence of SSI.

| Criteria | Pooled prevalence | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| After dropping 3 largest sample size | 2.6 (95% CI: 1.8.3.7%) | <.001 |

| After dropping 4 largest outcomes | 1.9 (95% CI: 1.3, 2.9%) | <.001 |

| After dropping 2 small sample size | 2.4 (95% CI: 1.6, 3.6%) | <.001 |

Discussion

A total of 2124 articles were retrieved from the included electronic databases and manual searches. A total of 43 articles conducted on 798 712 patients (ranging from 105 to 633 990 study participants) in 29 countries were included in the current study.

The current study found that the global pooled incidence of surgical site infection among patients was 2.5% (95% CI: 1.6, 3.7). The current study found a lower pooled incidence of SSI compared to another meta-analysis that reported a 7.0% incidence of SSI18 and 5.6% of pooled incidence of SSI.17 The variation may be attributed to the study population. Because the latter study was conducted on selected health conditions (appendectomy patients18 and a specific region,17 whereas the current study considered any patient and any country or region across the world.

Furthermore, the current study revealed that the highest incidence of SSI was reported among the studies conducted in the African region which accounted for 7.2% (95% CI: 4.3, 11.8%). It was less than the finding of another report that the incidence of SSI accounted for 12.6% in the African Region.18 It was relatively in line with another study conducted in developing countries that reported a 5.6% pooled incidence of SSI among the patients.17 The variation may be attributed to the study population and infection prevention and control practices. The latter study is conducted on selected health conditions (appendectomy patients), whereas the current study considered any patient. Another study conducted in sub-Saharan Africa also reported that the pooled incidence of SSI was 14.8%, which was significantly higher than the current finding.19

The variation may be attributed to the scope of the study and the extreme outcome that may influence the pooled incidence. Because in the current study, the extreme values were removed before analysis in order to make the finding more representative.

Another study, conducted on 6 anatomical locations, also reported that the pooled incidence of SSI was 11%,20 which was higher than the finding of the current study. The variation may be related to the variation in the anatomical locations considered. The former study considered only 6 anatomical locations, while the current study did not limit the infection based on the anatomical locations.

Furthermore, this study revealed that the highest incidence of SSI was reported among the articles conducted between 1996 to 2001 (2.9% [95% CI: 0.9%, 8.8%]) and reduced to 2.2% between 1996 and 2018. This may related to an increase in the implementation of SSI prevention intervention programs as well as increased concern about nosocomial infection.

In general, the current study revealed that there is a need to implement safety measures, particularly in low-and middle-income countries such as the African Region to maintain the health and safety of patients. Furthermore, strengthening the healthcare systems of low-income countries and of the countries in the WHO African region is paramount importance and can be achieved by educating and providing training to healthcare providers to enhance their skills.18 The World Health Organization’s general guideline or recommendations on preventing surgical site infection, which address the major issues, including surgical site infection prevention and reducing potential risk factors, SSI surveillance, the importance of a clean environment in the operating room, and the decontamination of medical devices and surgical instruments should be disseminated and implemented.2

Limitations

There was an unequal distribution of the studies conducted across the world. Furthermore, the incidence of SSI in many countries of the world was not included because of the lack of studies that met the eligibility criteria. We excluded not accessible articles, including the gray literature, which may affect the outcome. The majority of the included articles did not specify the types of surgery procedures employed, which limited us to provide the incidence of SSI based on the types of surgery procedures. Furthermore, the authors excluded articles not written in English and not available in full texts, including the case report, case studies, editorial paper, short communications as well as articles available with poor quality to reduce the bias. This reduced the number of articles included in the current studies.

Conclusions

This study revealed that the overall pooled incidence of SSI was 2.5%. Surgical site infections estimates varied among the WHO regions of the world. However, the highest incidence (2.7%) was observed in the African region. This indicates that there is a need to implement safety measures, including interventions to reduce SSI and improve patient safety.

List of abbreviations

CMA: Comprehensive Meta-Analysis; HAI: Healthcare Associated Infection, JBI: Joanna Briggs Institute; (PRISMA): Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; SSI: Surgical Site Infection; WHO: World Health Organization; MeSH: Medical Subject Heading.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580231162549 for Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Dechasa Adare Mengistu, Addisu Alemu, Abdi Amin Abdukadir, Ahmed Mohammed Husen, Fila Ahmed, Baredin Mohammed and Ibsa Musa in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-inq-10.1177_00469580231162549 for Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Dechasa Adare Mengistu, Addisu Alemu, Abdi Amin Abdukadir, Ahmed Mohammed Husen, Fila Ahmed, Baredin Mohammed and Ibsa Musa in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-inq-10.1177_00469580231162549 for Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Dechasa Adare Mengistu, Addisu Alemu, Abdi Amin Abdukadir, Ahmed Mohammed Husen, Fila Ahmed, Baredin Mohammed and Ibsa Musa in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their deepest thanks to Haramaya University staff for providing their constructive support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: DAM conceived the idea and had a major role in the review, extraction, and analysis of the data, writing, drafting and editing of the manuscript. AA, AA, IM, AM, BM, and FA has contributed to data extraction, analysis, and editing. Finally, the authors (DAM, AA, AA, IM, AM, BM, and FA) read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agreed on all aspects of this work.

Data Availability: Almost all data are included in this study. However, some data may be available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

ORCID iDs: Dechasa Adare Mengistu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0076-5586

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0076-5586

Abdi Amin Abdukadir  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0539-4059

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0539-4059

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-associated Infection Worldwide. World Health Organization; 2011. (accessed January 10, 2021). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/80135/1/9789241501507_eng.pdf

- 2. World Health Organization. Global Guidelines on the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection; 2016. (accessed January 12, 2021). https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CAQQw7AJahcKEwiImdymp9j8AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fapps.who.int%2Firis%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F10665%2F250680%2F9789241549882-eng.pdf&psig=AOvVaw2IMoK7CdSo2PuQMaK6MwIQ&ust=1674378271270106 [PubMed]

- 3. OMS. Prévention des infections nosocomiales. In: Guide pratique. 2èmeéd. OMS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16(3):128-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jarvis WR. Selected aspects of the socioeconomic impact of nosocomial infections: morbidity, mortality, cost, and prevention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996;17(8):552-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Promotion OoDPaH. Why Are Healthcare-Associated Infections Important? 2020. (accessed January 10, 2021). p. 2-3. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/healthcareassociated-infections%0AGoal

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs); 2020. (accessed January 11, 2021). p. 1-5. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/healthcare-associated-infections%0AGoal

- 8. World Health Organization ROfS-EAaR, P.O., Infection Control Practices. SEARO Regional Publication No. 41:10–8; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9. DC. Point prevalence survey of healthcare associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2011–2012). 2013. (accessed January 6, 2022). http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/healthcare-associated-infections-antimicrobial-use-PPS.pdf

- 10. Kitembo SK, Chugulu SG. Incidence of surgical site infections and microbial pattern at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre. Ann Afr Surg. 2013;10(1): 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allegranzi B, Bischoff P, de Jonge S, et al. New WHO recommendations on preoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):e276-e287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, et al. Health care–associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jenks PJ, Laurent M, McQuarry S, Watkins R. Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infection (SSI) and predicted financial consequences of elimination of SSI from an English hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2014;86(1):24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reichman DE, Greenberg JA. Reducing surgical site infections: a review. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(4):212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parienti JJ, Thibon P, Heller R, et al. Hand-rubbing with an aqueous alcoholic solution vs traditional surgical hand-scrubbing and 30-day surgical site infection rates: a randomized equivalence study. JAMA. 2002;288(6):722-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mangram AJ. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practice Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:250-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011;377(9761):228-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Danwang C, Bigna JJ, Tochie JN, et al. Global incidence of surgical site infection after appendectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ngaroua N, Ngah JE, Bénet T, Djibrilla Y. Incidence des infections du site opératoire en Afrique sub-saharienne: revue systématique et méta-analyse. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24(1):171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gillespie BM, Harbeck E, Rattray M, et al. Worldwide incidence of surgical site infections in general surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 488,594 patients. Int J Surg. 2021;95:106136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools for use in the JBI systematic reviews checklist for prevalence studies. The University of Adelaide. 2019. (accessed March 6, 2021). https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_AppraisalChecklist_for_Prevalence_Studies2017_0.pdf

- 23. Ades AE, Lu G, Higgins JP. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Making. 2005;25(6):646-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bunduki GK, Feasey N, Henrion MY, Noah P, Musaya J. Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in surgical wards of a large urban central hospital in Blantyre, Malawi: a point prevalence survey. Infect Prevent Practice. 2021;3(3):100163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang Y, Du M, Johnston JM, et al. Incidence of healthcare-associated infections in a tertiary hospital in Beijing, China: results from a real-time surveillance system. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang G, Huang Q, Zhang G, Jiang H, Lin Z. Point-prevalence surveys of hospital-acquired infections in a Chinese cancer hospital: from 2014 to 2018. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(12):1981-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Y, Zhang J, Wei D, Yang Z, Wang Y, Yao Z. Annual surveys for point-prevalence of healthcare-associated infection in a tertiary hospital in Beijing, China, 2012-2014. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang L, Zhou KH, Chen W, Yu Y, Feng SF. Epidemiology and risk factors for nosocomial infection in the respiratory intensive care unit of a teaching hospital in China: a prospective surveillance during 2013 and 2015. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee MK, Chiu CS, Chow VC, Lam RK, Lai RW. Prevalence of hospital infection and antibiotic use at a university medical center in Hong Kong. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(4):341-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mezemir R, Seid A, Gishu T, Demas T, Gize A. Prevalence and root causes of surgical site infections at an academic trauma and burn center in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Motbainor H, Bereded F, Mulu W. Multi-drug resistance of blood stream, urinary tract and surgical site nosocomial infections of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa among patients hospitalized at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Azeze GG, Bizuneh AD. Surgical site infection and its associated factors following cesarean section in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nash MC, Strom JA, Pathak EB. Prevalence of major infections and adverse outcomes among hospitalized. ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients in Florida, 2006. BMC Cardiovasc Disorders. 2011;11(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olsen MA, Butler AM, Willers DM, Devkota P, Gross GA, Fraser VJ. Risk factors for surgical site infection after low transverse cesarean section. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(6):477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Magill SS, Hellinger W, Cohen J, et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in acute care hospitals in Jacksonville, Florida. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(3):283-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pittet D, Harbarth S, Ruef C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for nosocomial infections in four university hospitals in Switzerland. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(1):37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mühlemann K, Franzini C, Aebi C, et al. Prevalence of nosocomial infections in Swiss children’s hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(9):765-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ahoyo TA, Bankolé HS, Adéoti FM, et al. Prevalence of nosocomial infections and anti-infective therapy in Benin: results of the first nationwide survey in 2012. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3(1):1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dégbey C, Kpozehouen A, Coulibaly D, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with surgical site infections in the university clinics of traumatology and urology of the National University Hospital Centre Hubert Koutoukou Maga in Cotonou. Front Public Health. 2021;9:629351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ott E, Saathoff S, Graf K, Schwab F, Chaberny IF. The prevalence of nosocomial and community acquired infections in a university hospital: an observational study. Deutsch Ärztebl Int. 2013;110(31-32):533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arefian H, Hagel S, Fischer D, et al. Estimating extra length of stay due to healthcare-associated infections before and after implementation of a hospital-wide infection control program. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0217159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zotti CM, Ioli GM, Charrier L, et al. Hospital-acquired infections in Italy: a region wide prevalence study. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56(2):142-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gentili A, Di Pumpo M, La Milia DI, et al. A six-year point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections in an Italian teaching acute care hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Askarian M, Yadollahi M, Assadian O. Point prevalence and risk factors of hospital acquired infections in a cluster of university-affiliated hospitals in Shiraz, Iran. J Infect Public Health. 2012;5(2):169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Heydarpour F, Rahmani Y, Heydarpour B, Asadmobini A. Nosocomial infections and antibiotic resistance pattern in open-heart surgery patients at Imam Ali Hospital in Kermanshah, Iran. GMS Hyg Infect Control. 2017;12:Doc07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kołpa M, Wałaszek M, Gniadek A, Wolak Z, Dobroś W. Incidence, microbiological profile and risk factors of healthcare-associated infections in intensive care units: a 10 year observation in a provincial hospital in Southern Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(1):112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tomczyk-Warunek A, Blicharski T, Blicharski R, et al. Retrospective study of nosocomial infections in the orthopaedic and rehabilitation clinic of the medical university of Lublin in the years 2018–2020. J Clin Med. 2021;10(14):3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Girard R, Mazoyer MA, Plauchu MM, Rode G. High prevalence of nosocomial infections in rehabilitation units accounted for by urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injury. J Hosp Infect. 2006;62(4):473-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Esen S, Leblebicioglu H. Prevalence of nosocomial infections at intensive care units in Turkey: a multicentre 1-day point prevalence study. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36(2):144-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Izquierdo-Cubas F, Zambrano A, Frometa I, et al. National prevalence of nosocomial infections. Cuba 2004. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68(3):234-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Danchaivijitr S, Judaeng T, Sripalakij S, Naksawas K, Plipat T. Prevalence of nosocomial infection in Thailand 2006. J Med Assoc Thailand. 2007;90(8):1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Faria S, Sodano L, Gjata A, et al.; Prevalence Study Group. The first prevalence survey of nosocomial infections in the University Hospital Centre ‘Mother Teresa’ of Tirana, Albania. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(3):244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Balkhy HH, Cunningham G, Chew FK, et al. Hospital-and community-acquired infections: a point prevalence and risk factors survey in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(4):326-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Owusu E, et al. Multi-centre point-prevalence survey of hospital-acquired infections in Ghana. J Hosp Infect. 2019;101(1):60-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Abubakar U. Point-prevalence survey of hospital acquired infections in three acute care hospitals in Northern Nigeria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Durlach R, McIlvenny G, Newcombe RG, et al. Prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections in Argentina; comparison with England, Wales, Northern Ireland and South Africa. J Hosp Infect. 2012;80(3):217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mukamuhirwa D, Lilian O, Baziga V, et al. Prevalence of surgical site infection among adult patients at a rural district hospital in Southern Province, Rwanda. Rwanda J Med Health Sci. 2022;5(1):34-45. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mawalla B, Mshana SE, Chalya PL, Imirzalioglu C, Mahalu W. Predictors of surgical site infections among patients undergoing major surgery at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania. BMC Surg. 2011;11(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brown S, Kurtsikashvili G, Alonso-Echanove J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of surgical site infection in Tbilisi, Republic of Georgia. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(2):160-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Strasheim W, Kock MM, Ueckermann V, Hoosien E, Dreyer AW, Ehlers MM. Surveillance of catheter-related infections: the supplementary role of the microbiology laboratory. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ghali H, Ben Cheikh A, Bhiri S, Khefacha S, Latiri HS, Ben Rejeb M. Trends of healthcare-associated infections in a Tuinisian University Hospital and impact of COVID-19 pandemic. Inquiry: 2021;58:00469580211067930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shrestha SK, Trotter A, Shrestha PK. Epidemiology and risk factors of healthcare-associated infections in critically ill patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal: a prospective cohort study. Infect Dis: Res Treat. 2022;15:11786337211071120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Custovic A, Smajlovic J, Hadzic S, Ahmetagic S, Tihic N, Hadzagic H. Epidemiological surveillance of bacterial nosocomial infections in the surgical intensive care unit. Mater Socio Med. 2014;26(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Russo PL, Stewardson AJ, Cheng AC, Bucknall T, Mitchell BG. The prevalence of healthcare associated infections among adult inpatients at nineteen large Australian acute-care public hospitals: a point prevalence survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sahu MK, Siddharth B, Choudhury A, et al. Incidence, microbiological profile of nosocomial infections, and their antibiotic resistance patterns in a high volume Cardiac Surgical Intensive Care Unit. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016;19(2):281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nouetchognou JS, Ateudjieu J, Jemea B, Mesumbe EN, Mbanya D. Surveillance of nosocomial infections in the Yaounde University Teaching Hospital, Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580231162549 for Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Dechasa Adare Mengistu, Addisu Alemu, Abdi Amin Abdukadir, Ahmed Mohammed Husen, Fila Ahmed, Baredin Mohammed and Ibsa Musa in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-inq-10.1177_00469580231162549 for Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Dechasa Adare Mengistu, Addisu Alemu, Abdi Amin Abdukadir, Ahmed Mohammed Husen, Fila Ahmed, Baredin Mohammed and Ibsa Musa in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-inq-10.1177_00469580231162549 for Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Dechasa Adare Mengistu, Addisu Alemu, Abdi Amin Abdukadir, Ahmed Mohammed Husen, Fila Ahmed, Baredin Mohammed and Ibsa Musa in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing