Abstract

DYT1 dystonia is a debilitating neurological movement disorder arising from mutation in the AAA+ ATPase TorsinA. The hallmark of Torsin dysfunction is nuclear envelope blebbing resulting from defects in nuclear pore complex biogenesis. Whether blebs actively contribute to disease manifestation is unknown. We report that FG-nucleoporins (FG-Nups) in the bleb lumen form aberrant condensates and contribute to DYT1 dystonia by provoking two proteotoxic insults. Short-lived ubiquitylated proteins that are normally rapidly degraded partition into the bleb lumen and become stabilized. Additionally, blebs selectively sequester a specific HSP40/HSP70 chaperone network that is modulated by the bleb component MLF2. MLF2 suppresses the ectopic accumulation of FG-Nups and modulates the selective properties and size of condensates in vitro. Our studies identify dual mechanisms of proteotoxicity in the context of condensate formation and establish FG-Nup-directed activities for a nuclear chaperone network.

Introduction

Torsin ATPases (Torsins) are the only members of the AAA+ protein superfamily that localize within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and nuclear envelope (NE) [1, 2]. TorsinA is essential for viability [3] and strictly requires regulatory cofactors to hydrolyze ATP[4]. A mutation in TorsinA that disrupts the interactions with its cofactors results in a loss of ATPase activity [5, 6] and is responsible for a debilitating neurological movement disorder called DYT1 dystonia [7]. Mutations in the Torsin activator LAP1 also give rise to dystonia and myopathies [8–10]. Thus, the Torsin system is critical for neurological function [9, 11].

While the molecular targets of Torsins and the mechanism of DYT1 dystonia onset are not understood, the hallmark phenotype observed across diverse animal and cell-based models of DYT1 dystonia is NE blebbing [3, 12–21]. NE blebs in the context of Torsin disruption are omega-shaped herniations of the inner nuclear membrane that are constricted at their base by a nuclear pore complex (NPC)-like structure and stem from defective NPC assembly [18, 22] (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Blebs are observed via distinct mechanisms of Torsin perturbation, i.e., dominant-negative alleles, Torsin-null alleles, siRNA, and in yeast harboring mutations of NPC-related proteins [23, 24]. As a consequence of NE blebbing, nuclear transport defects have been observed in models of compromised Torsin function including patient-derived iPSC neurons [12, 20, 21].

NPCs are composed of nucleoporins (Nups), several of which contain disordered phenylalanine-glycine (FG)-rich domains, which form a dense hydrogel and establish the permeability barrier characteristic of NPCs [25–28]. While small (<30 kDa) molecules can passively diffuse through this barrier [29], larger molecules require facilitated passage via nuclear transport receptors (NTRs) [30].

NE blebs arising from Torsin deficiency are enriched for FG-Nups but do not contain NTRs or bulk nuclear export cargo [18, 22]. Moreover, the poorly characterized protein myeloid leukemia factor 2 (MLF2) and K48-linked ubiquitin (Ub) chains are diagnostic constituents of the bleb lumen [18, 20, 22] (Extended Data Fig. 1a). While Ub accumulation and defects in the ubiquitin/proteasome system have been implicated in many other neurological disorders including Huntington’s and Parkinson’s disease [31–33], it is unknown whether or how NE blebs contribute to DYT1 dystonia onset. Both the lack of suitable readouts and our incomplete understanding of the molecular composition of blebs represent major obstacles towards identifying their functional consequences.

In this study, we develop a virally-derived model substrate to define the bleb proteome and probe the significance of ubiquitin accumulation for DYT1 dystonia development. We find that normally short-lived proteins evade degradation once they are trapped inside blebs. Along with stabilized ubiquitylated proteins, blebs sequester a highly specific chaperone network composed of HSP40s and HSP70s. The FG-Nup Nup98 is required for blebs to form, and we demonstrate that blebs harbor an FG-rich condensate. We combine cellular and in vitro approaches to assign an FG-directed activity to MLF2 in complex with HSP70 and DNAJB6. Together, our results advance our understanding of cellular phase separation and define a link between PQC defects and disease etiology via pathological NE-associated condensates.

Results

Torsin deficiency stabilizes rapidly degraded proteins.

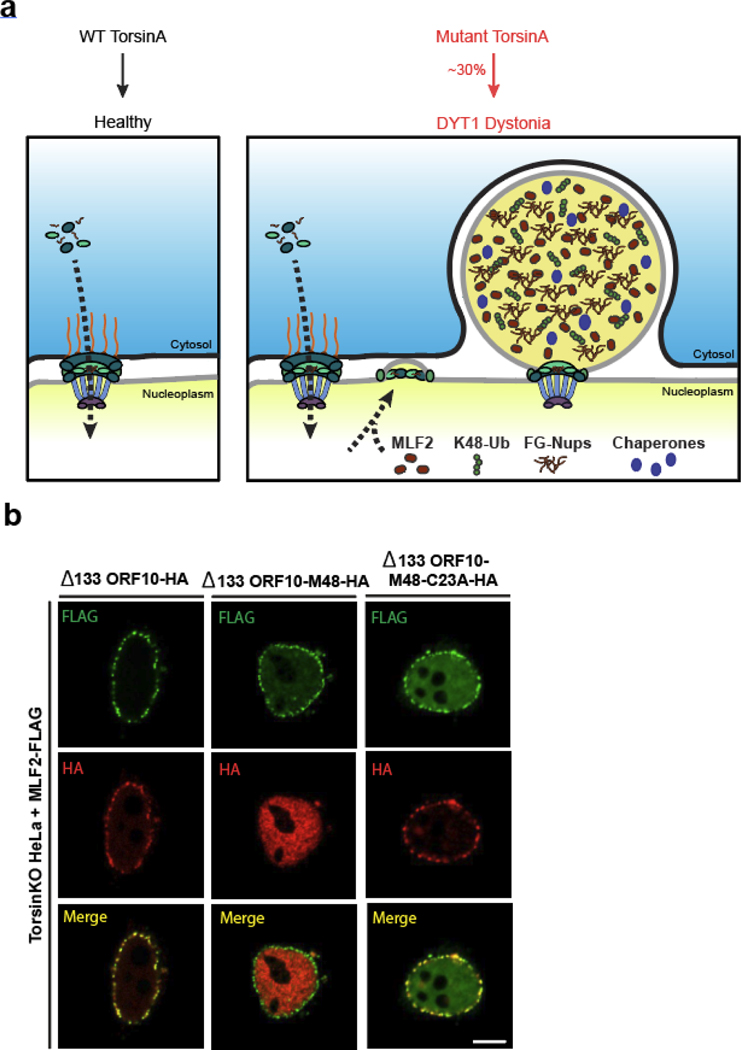

To develop approaches for probing the consequences of sequestering protein into NE blebs, we examined viral proteins that have been functionally tied to nuclear transport. ORF10 from Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is produced as a full length 418-residue protein and a shorter 286-residue protein (Δ133 ORF10) via an alternative translation initiation (Fig. 1a,b). The full-length protein [34] localizes diffusely within the nucleoplasm in wild type (WT) and TorsinKO HeLa cells (Fig. 1c). However, Δ133 ORF10 becomes tightly sequestered into NE foci that strictly co-localize with K48-Ub in TorsinKO cells (Fig. 1c). Recruitment to these foci strictly depends on ubiquitylation as fusing a deubiquitylating (DUB) domain [35] to Δ133 ORF10 prevents NE sequestration (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Because Δ133 ORF10 remains diffusely nucleoplasmic in WT cells (Fig. 1c) and associates with more K48-Ub in TorsinKO compared to WT cells (Fig. 1d), we establish Δ133 ORF10 as the only known protein that localizes to blebs in a ubiquitin-dependent manner.

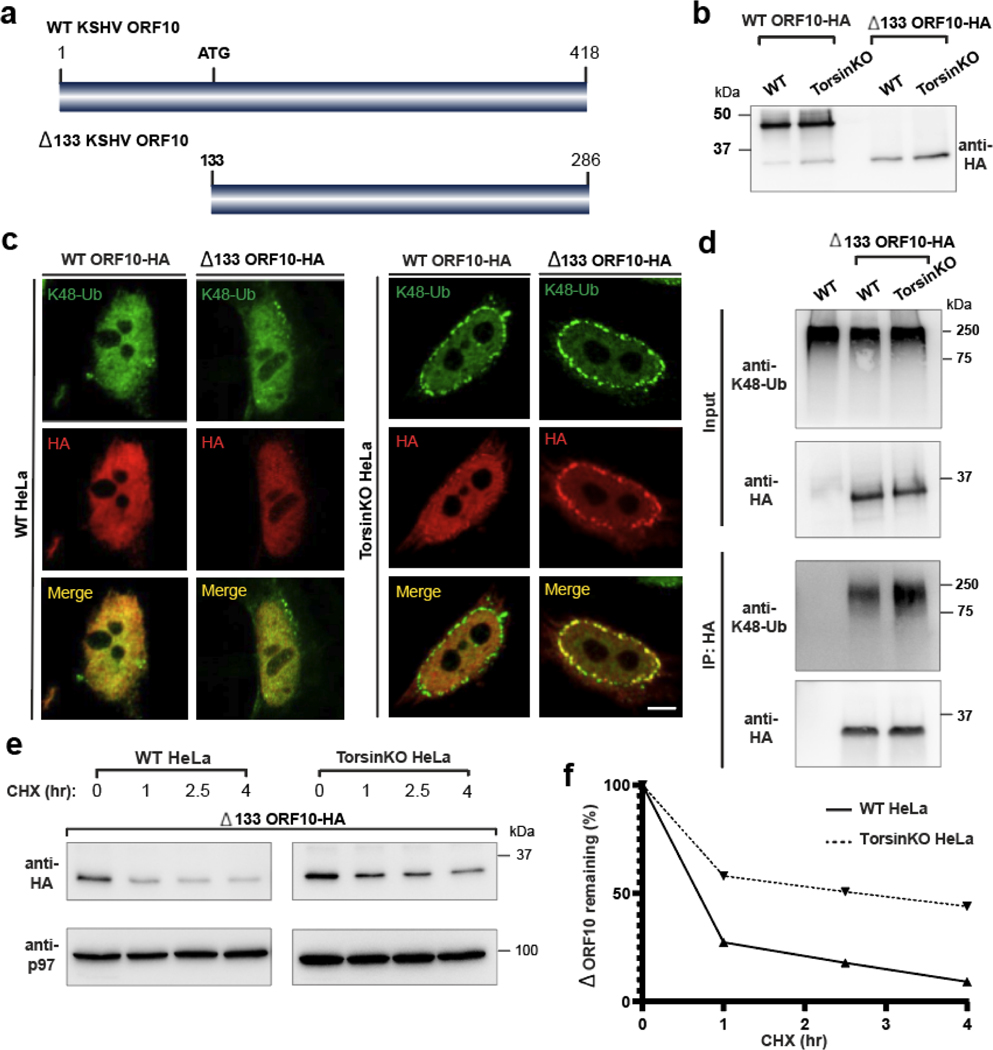

Figure 1. NE herniations arising from Torsin ATPase deficiency sequester and stabilize short-lived protein.

a, Schematic model of the ORF10 protein from KSHV. KSHV ORF10 contains an internal start codon at residue 133 that produces Δ133 ORF10. b, Immunoblot demonstrating expression of Δ133 ORF10-HA in WT and TorsinKO HeLa cells 24 hours post transfection. Note that ORF10-HA is produced as a major full-length protein a lower abundance Δ133 product. c, Representative IF images of full length and Δ133 ORF10-HA in WT and TorsinKO cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. d, Anti-HA immunoprecipitation (IP) from WT or TorsinKO cells expressing Δ133 ORF10-HA. The IP was probed with antibodies against K48-Ub and HA. Note that Δ133 ORF10-HA is associated with more K48-Ub in TorsinKO than WT cells. e, A cycloheximide (CHX) chase over four hours in WT and TorsinKO cells expressing Δ133 ORF10-HA. Cells were treated with 100 μg/mL of CHX at 37°C for the indicated timepoints. p97 serves as a loading control. f, Relative percentage of Δ133 ORF10-HA obtained in (e) was determined via densitometry by comparing to the abundance at time = 0. All data were standardized to p97 levels. Source numerical data and unprocessed blots are available in source data.

As Δ133 ORF10 is less abundant and associated with lower levels of K48-Ub in WT cells compared to TorsinKO cells (Fig. 1d), we hypothesized that Δ133 ORF10 is normally a short-lived protein. Indeed, we observed its half-life in WT cells to be approximately 45 minutes (Fig. 1e,f). In TorsinKO cells, Δ133 ORF10 is stabilized and exists with a half-life of four hours (Fig. 1e,f). This reveals an unexpected proteotoxic property of NE blebs.

Blebs are enriched for a specific chaperone network.

The absence of a comprehensive, bleb-specific proteome is a major limitation in understanding the molecular underpinnings of NE bleb formation. We fused the engineered ascorbate peroxidase APEX2 [36, 37] to MLF2-HA and performed a biotin-based proximity labeling reaction (Fig. 2a). To control the MLF2-APEX2-HA protein level, we placed its expression under a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible promoter (Fig. 2b). The presence of biotin conjugates within blebs after the APEX reaction was verified by immunofluorescence (IF) (Fig. 2c). The biotin-conjugating activity of APEX2 was confirmed via immunoblotting (Fig. 2d). After performing the APEX2 reaction, NE fractions were biochemically separated from WT and TorsinKO cells. Biotinylated proteins were enriched via streptavidin-coated beads and identified by mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Fig. 2e, Supplemental Table 1). In parallel, we performed an immunoprecipitation (IP) using Δ133 ORF10-HA followed by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 2e, Supplemental Table 2). This allowed for a direct comparison of the bleb proteome from two independent approaches with our previously published dataset of immunoprecipitated K48-Ub from NE fractions [22]. From these three datasets, we considered proteins with a ≥1.5-fold enrichment of spectral counts in TorsinKO samples compared to WT (Fig. 2e).

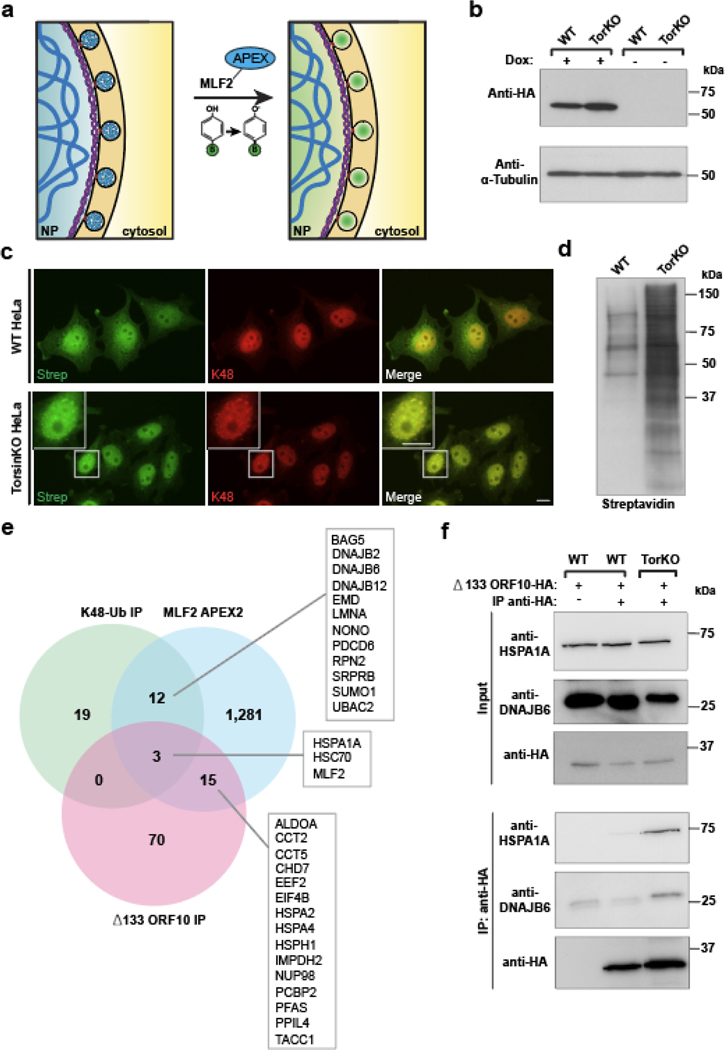

Figure 2. A comparative proteomics approach reveals NE blebs in Torsin-deficient cells are enriched for a highly specific chaperone network.

a, A schematic illustration of the APEX2 reaction strategy to identify bleb protein contents. Left panel, the MLF2-APEX2-HA fusion protein (blue) localizes within the bleb lumen. Right panel, after incubation with 500 μM of biotin-phenol, cells were treated with 1 mM H2O2. Upon exposure to H2O2, APEX2 oxidizes biotin phenol to form highly reactive biotin radicals that covalently label protein within a ~20 nm radius (ref. [74]) (green cloud). NP, nucleoplasm. b, The expression of MLF2-APEX2-HA was engineered in WT and TorsinKO cells to be under doxycycline (Dox) induction. Cells were treated with Dox for 24 hours before immunoblotting. c, Representative IF images of WT and TorsinKO cells after the APEX2 reaction. Note the enrichment of biotin conjugates in blebs of TorsinKO cells compared to the diffuse nuclear signal in WT cells. Strep (green) indicates fluorescently conjugated streptavidin signal and K48-Ub (red) indicate NE blebs. Scale bar, 10 μm. d, Immunoblot of biochemically enriched NE fractions from WT and TorsinKO cells after the MLF2-APEX2 reaction as described in (c). e, Candidate proteins potentially enriched in blebs were identified by mass spectrometry (MS). These were defined as proteins with spectral counts ≥1.5-fold enriched in APEX2 reactions carried out in TorsinKO cells compared to WT. The number of candidates identified for each of the three MS datasets are displayed as numbers within the Venn diagram. Hits overlapping between datasets are listed in alphabetical order. See Supplemental Tables 1,2 for complete datasets. f, To validate MS findings, the stable interaction between Δ133 ORF10-HA and HSPA1A or DNAJB6 was interrogated by co-IP. These interactions are unique to TorsinKO cells, consistent with the findings by comparative MS in panel (e). Unprocessed blots are available in source data.

Only three proteins were consistently enriched across all datasets in samples from TorsinKO cells—MLF2, HSPA1A, and HSC70 (Fig. 2e). HSPA1A and HSC70 are the canonical HSP70 members in mammalian cells, mediating a range of essential processes [38]. This functional diversity is achieved, at least in part, by interactions with J-domain proteins (HSP40s) [39]. Thus, we asked whether the HSP40s identified in the MLF2-APEX2 and K48-Ub datasets may also be enriched in blebs.

HSP70s and HSP40s are sequestered into NE blebs.

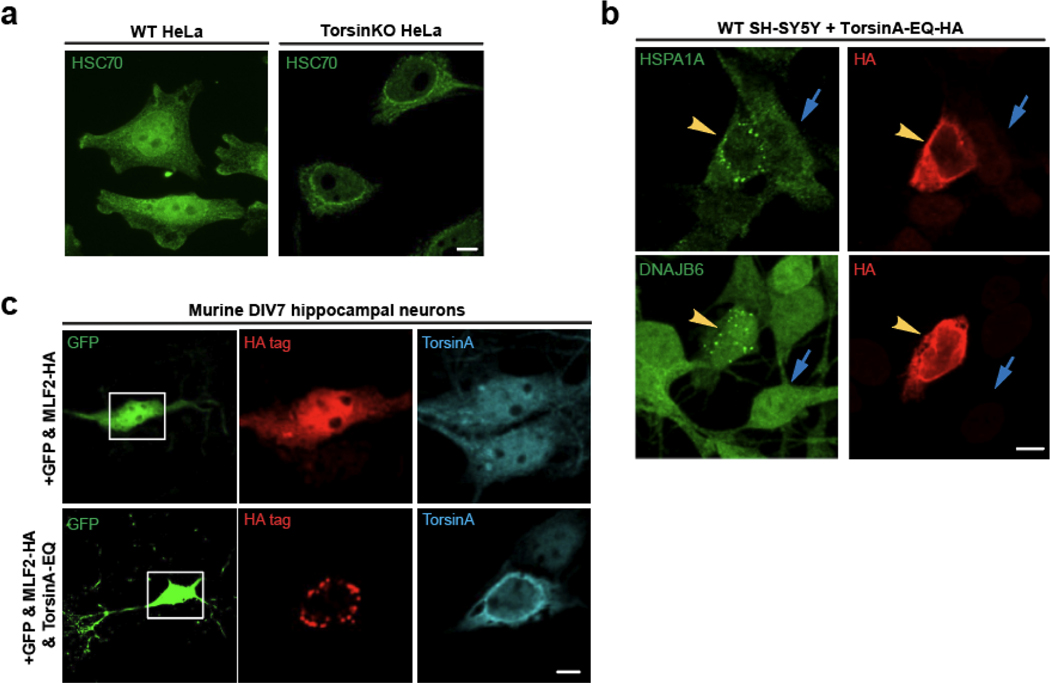

We performed a co-IP with Δ133 ORF10 and found it to stably interact with DNAJB6 exclusively in TorsinKO cells (Fig. 2f). Next, we determined whether HSPA1A, HSC70, DNAJB6, and DNAJB2 localized to blebs at endogenous expression levels. In TorsinKO cells, these chaperones redistribute from diffuse cytosolic/nucleoplasmic distributions to foci that decorate the nuclear rim (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 2a). By overexpressing a dominant-negative TorsinA-EQ construct, we also found that chaperones localize to blebs in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (Extended Data Fig. 2b).

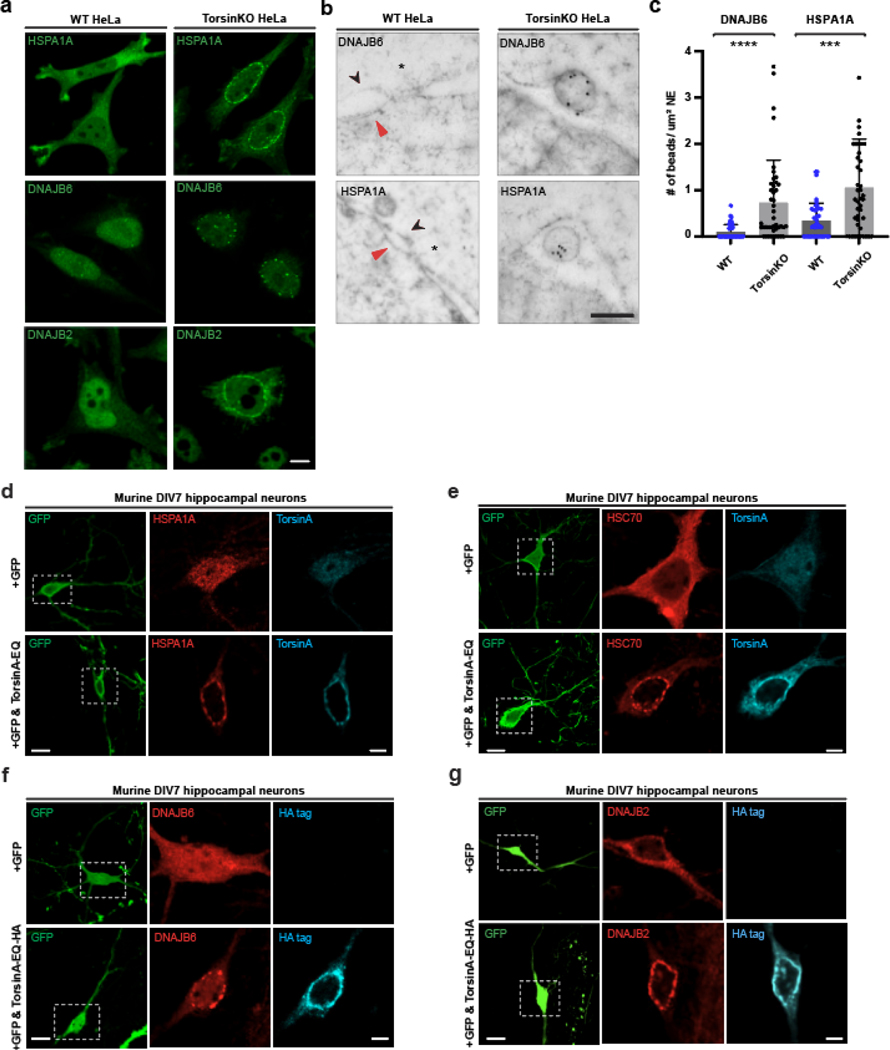

Figure 3. Highly abundant molecular chaperones are sequestered into NE blebs of tissue culture cells and primary mouse neurons with compromised TorsinA function.

a, Antibodies against endogenous HSPA1A, DNAJB6, and DNAJB2 (green) reveal that chaperones from the HSP70 and HSP40 families become tightly sequestered into NE blebs upon Torsin deficiency. Scale bar, 5 μm. b, EM ultrastructure of the NE from WT or TorsinKO cells labeled with immunogold beads conjugated to anti-DNAJB6 (top) or anti-HSPA1A (bottom). Black arrowhead, outer nuclear membrane. Red arrowhead, inner nuclear membrane. Asterisk, NPC. Scale bar, 250 nm. c, The number of DNAJB6 or HSPA1A immunogold beads per μm2 centered around the NE (DNAJB6, WT n=50 micrographs, TorsinKO n=43 micrographs. HSPA1A, WT n=45 micrographs, TorsinKO n=43 micrographs. 400 μm2 of NE was quantified/condition). Error bars, SD. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test where **** indicates p < 0.0001 and *** p = 0.0002. d-g, Murine DIV4 hippocampal neurons were transfected with GFP and empty vector (top row of all panels) or a dominant-negative TorsinA-EQ construct (bottom row of all panels). Constructs were allowed to express for 72 hours before processing the DIV7 cultures for IF. GFP expression was used to distinguish neurons from other cell types in the heterogeneous primary cell culture. Localization of the chaperones shown in panels (d-g) was probed using antibodies against the indicated endogenous chaperone (red). Untagged TorsinA-EQ was transfected in panels (d) and (e) and detected with a TorsinA antibody (cyan). TorsinA-EQ-HA was transfected in panels (f) and (g) and detected with an anti-HA antibody (cyan). Scale bar, 20 μm for unmagnified images, 5 μm for magnified images. Source numerical data are available in source data.

We additionally performed immunogold labeling and examined the ultrastructure of the NE with electron microscopy (EM) (Fig. 3b,c). While we did not detect DNAJB6 or HSPA1A at mature NPCs, DNAJB6 and HSPA1A localize within the bleb lumen (Fig. 3b,c). Thus, we conclude that multiple members of the HSP70 and HSP40 families become tightly sequestered into the bleb lumen in Torsin-deficient cells.

Neurons lacking TorsinA function sequester chaperones.

As DYT1 dystonia is a neurological disease, we investigated whether the sequestration of chaperones occurs in neurons with compromised Torsin function. In mouse models of DYT1 dystonia, ≥80% of central nervous system nuclei exhibit NE blebs in eight-day-old mice [16]. This number decreases when expression of TorsinB begins after about 14 days [16]. We therefore cultured primary murine hippocampal neurons and transfected GFP with or without the dominant-negative TorsinA-EQ construct after four days in vitro (DIV4). Cells were processed for IF on DIV7 to recapitulate the peak blebbing phenotype reported in conditional TorsinKO mice [16]. GFP was used to distinguish neurons from other cell types in the primary cultures.

In neurons with functional Torsins, the chaperones are diffuse throughout the cytosol/nucleoplasm (Fig. 3d–g). Upon expression of TorsinA-EQ, these chaperones become sequestered into blebs (Fig. 3d–g). MLF2-HA is also sequestered into blebs in Torsin-deficient neurons when overexpressed (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Thus, the sequestration of highly abundant and essential molecular chaperones into blebs is a conserved and general consequence of Torsin dysfunction.

MLF2 recruits DNAJB6 to blebs.

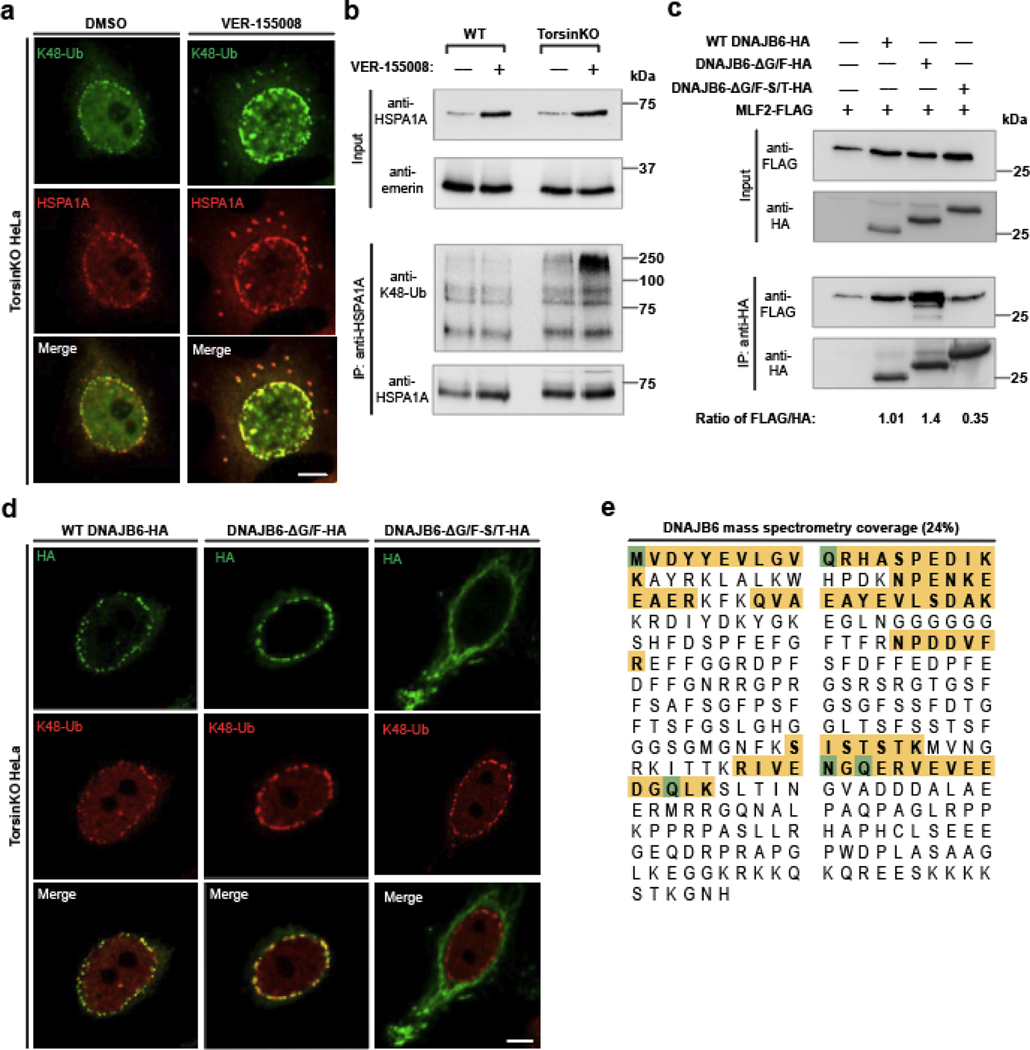

To understand the relationship between MLF2 and chaperones, we depleted MLF2 from TorsinKO cells. Upon MLF2 knockdown, K48-Ub and HSPA1A remained efficiently sequestered into NE foci but DNAJB6 was no longer recruited to blebs (Fig. 4a). While the recruitment of HSPA1A to blebs was independent of MLF2, the small molecule VER-155008, which approximates the ADP-bound state of HSP70 [40], strongly promoted the recruitment of K48-Ub to blebs (Extended data 3a,b).

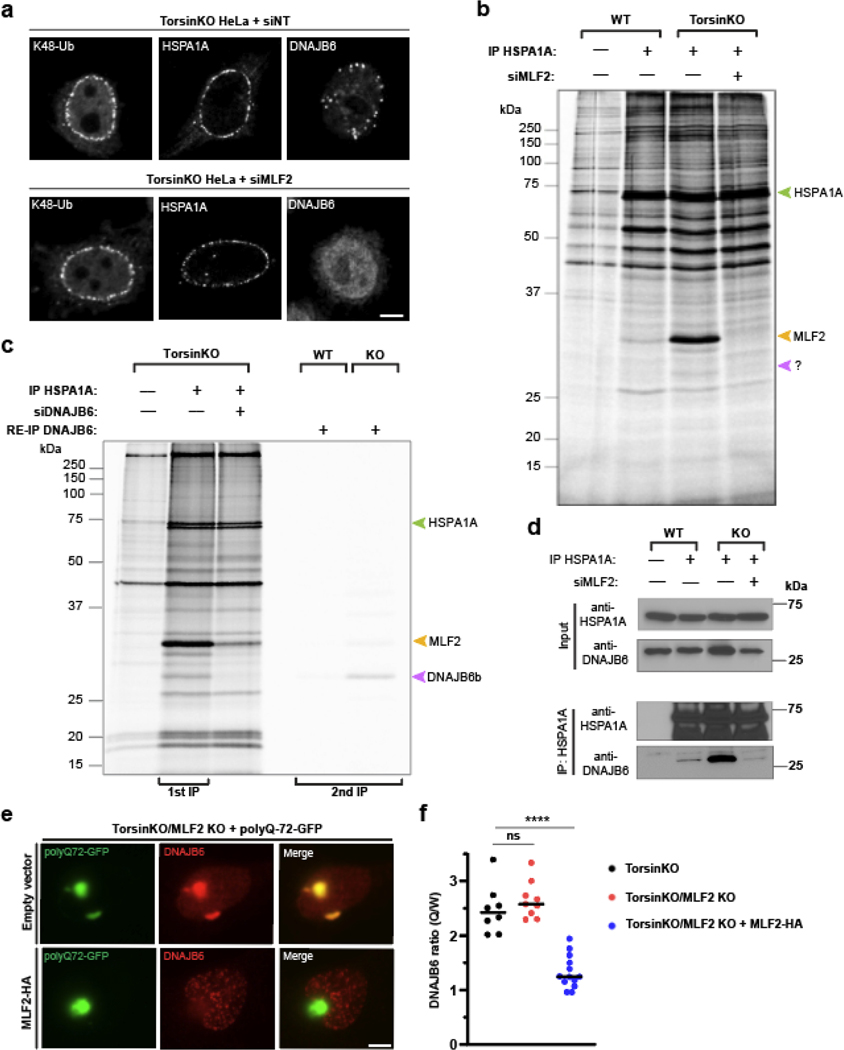

Figure 4. MLF2 is required for DNAJB6 to localize to NE blebs in Torsin-deficient cells.

a, Representative IF images of chaperone localization upon knocking down MLF2 for 48 hours. Scale bar, 5 μm. b, WT and TorsinKO cells were metabolically labeled overnight with 150 μCi/mL 35S-Cys/Met and treated with a nontargeting or MLF2-targetting siRNA for 48 hours. HSPA1A was immunoprecipitated and stably associated proteins were detected by autoradiography. Green arrowhead, HSPA1A. Yellow arrowhead, MLF2. Purple arrowhead, unknown protein. c, Lanes 1–3, metabolically labeled TorsinKO cells were treated with a nontargeting or siRNA targeting DNAJB6 for 48 hours. HSPA1A was immunoprecipitated and co-eluting proteins were visualized by autoradiography. Lanes 4–5, metabolically labeled WT or TorsinKO cells under nontargeting siRNA were subjected to an HSPA1A IP, then disassociated and subjected to a second IP against DNAJB6 (RE-IP). d, HSPA1A was immunoprecipitated from TorsinKO and WT HeLa cells under siNT or siMLF2 conditions. e, A “tug of war” IF experiment showing that overexpression of MLF2-HA in TorsinKO/MLF2 KO cells titrates DNAJB6 out of polyQ72-GFP aggregates and into blebs. Representative IF images of TorsinKO/MLF2KO cells transfected with polyQ72-GFP alone (left column) or in combination with MLF2-HA (right column). Note that the HA channel is not shown. Scale bar, 5 μm. f, The ratio of DNAJB6 fluorescence signal inside polyQ72-GFP foci (Q) compared to whole cell (W) was calculated for at least eight cells/condition. Bars over datapoints indicate the mean ratio. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test where **** indicates p < 0.0001. ns, not significant. Source numerical data and unprocessed blots are available in source data.

Next, we performed a radioimmunoprecipitation of endogenous HSPA1A from WT and TorsinKO cells under non-targeting or siMLF2 conditions (Fig. 4b). Two major co-immunoprecipitating bands were highly enriched in the TorsinKO siNT condition (Fig. 4b). The most prominent band around 28 kDa disappeared when MLF2 was knocked down, suggesting that HSPA1A interacts with significantly more MLF2 in TorsinKO cells than in WT (Fig. 4b). Another band unique to the TorsinKO siNT condition migrated at the expected molecular mass of DNAJB6 (27 kDa) and co-immunoprecipitates with HSPA1A exclusively in TorsinKO cells in an MLF2-dependent manner (Fig. 4b).

To test if this protein was DNAJB6, we performed both a DNAJB6 knockdown and a RE-IP wherein the HSPA1A co-immunoprecipitating proteins were dissociated and subjected to another IP using an antibody against DNAJB6 (Fig. 4c). When DNAJB6 was depleted by RNAi, the band migrating around 27 kDa no longer co-immunoprecipitated with HSPA1A (Fig. 4c). Unexpectedly, less MLF2 co-immunoprecipitated with HSPA1A when DNAJB6 was depleted (Fig. 4c). Upon RE-IP, a single band migrating around 27 kDa was clearly detectable from TorsinKO cells (Fig.4c). We further confirmed this interaction by traditional co-IP (Fig. 4d). The recruitment of DNAJB6 to blebs strongly depended on the S/T-rich region within DNJAB6 and not the G/F-rich region (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Lastly, we confirmed the identity of the 27 kDa band by mass spectrometry as DNAJB6 (Extended Data Fig. 3e). We conclude that MLF2 recruits DNAJB6 to blebs where these proteins stably interact with HSPA1A.

Sequestering chaperones may contribute to proteotoxicity.

DNAJB6 prevents the formation of toxic inclusions including polyglutamine (poly-Q) expansions [41–43]. Thus, we determined if this funciton is affected by sequestering DNAJB6 into blebs. In TorsinKO/MLF2 KO cells, DNAJB6 is recruited to poly-Q aggregates (Fig. 4e,f). However, upon re-introducing MLF2-HA via transient transfection, DNAJB6 is sequestered into blebs and away from the poly-Q aggregate (Fig. 4e,f). This titration of DNAJB6 out of an aggregate-prone client underscores the pronounced proteotoxic potential of NE blebs with MLF2 being a critical modulator of this property.

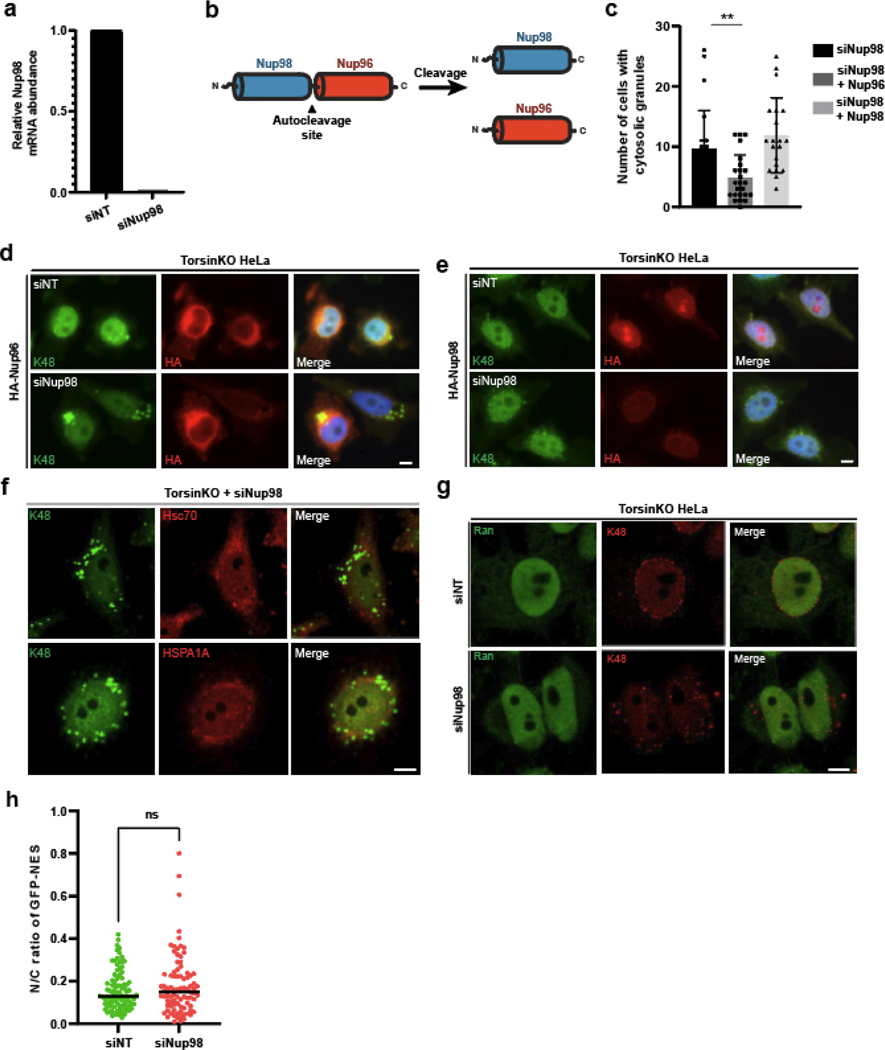

Sequestering protein into NE blebs requires Nup98.

While analyzing the MLF2-APEX2 MS datasets, we noticed that specific Nups including Nup98 were enriched in samples from TorsinKO cells (Fig. 5a) [44]. Since the only protein known to localize to blebs in a K48-Ub-dependent manner is KSHV ORF10 (Fig. 1), which interacts with Nup98 [34], we prioritized our analysis on Nup98.

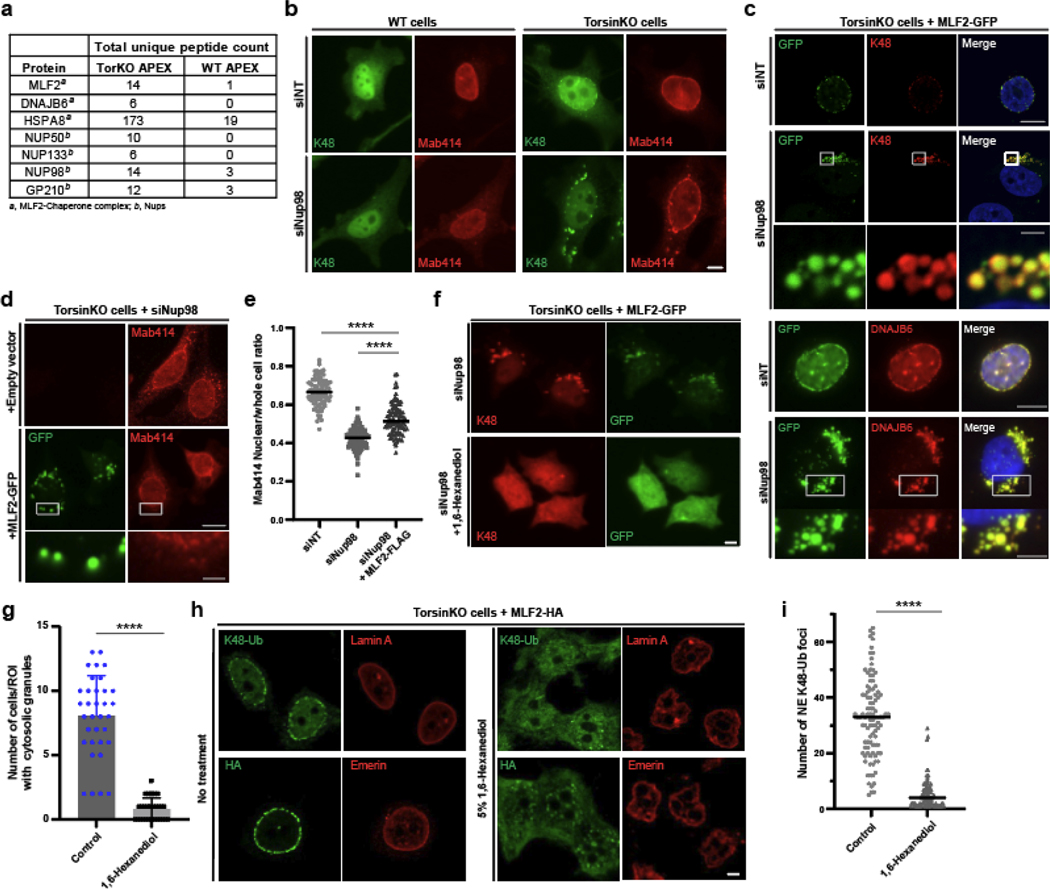

Figure 5. Nup98 is required for the sequestration into NE blebs harboring condensates composed of K48-Ub, FG-nucleoporins, MLF2, and chaperones.

a, The APEX2 MS strategy described in (figure 2a) reveals an enrichment of chaperones and nucleoporins interacting with MLF2 in TorsinKO cells. b, Representative IF images of WT and TorsinKO cells under siNup98 conditions. In TorsinKO cells, cytosolic granules enriched for K48-Ub and FG-Nups (Mab414, red) form upon siNup98. Note the normal NE accumulation of K48-Ub in TorsinKO cells is abolished under siNup98. Scale bar, 5 μm. c, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells expressing MLF2-GFP under siNup98 conditions. MLF2-GFP (top panels) localizes to the cytosolic granules containing K48-Ub that arise upon Nup98 depletion in TorsinKO cells. DNAJB6 (bottom panels) is also recruited to the cytosolic granules. 1x images scale bar, 10 μm. 8x magnification scale bar, 1.25 μm. d, Representative IF images of the effect on the FG-Nup accumulation in cytosolic granules upon overexpression of MLF2-GFP under siNup98 conditions. 1x images scale bar, 10 μm. 8x magnification scale bar, 1.25 μm. e, The ratio of nuclear to whole cell nucleoporin (Mab414) signal was determined for 94 cells/condition. Bars over datapoints indicate the mean ratio. Expressing MLF2-FLAG significantly decreases the amount of cytosolic FG-Nup mislocalization upon siNup98. f, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells expressing MLF2-GFP under siNup98 conditions in the absence or presence of 5% 1,6-hexanediol for five minutes. Scale bar, 5 μm. g, The presence of cytosolic K48-Ub granules upon Nup98 depletion was assessed for 300 cells/condition (≥35 regions of interest (ROI) quantified/condition). Error bar, SD. h, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells expressing MLF2-HA in the absence (left columns) or presence (right columns) of 5% 1,6-hexanediol for five minutes. The intact NE is indicated by laminA (top panels) and emerin (bottom panels). Scale bar, 5 μm. i, The number of K48-Ub foci around the NE rim was determined for 100 cells/condition. Bars over datapoints indicate the mean number of K48-Ub foci. For all panels, statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test. **** indicates p < 0.0001. Source numerical data are available in source data.

Depleting Nup98 provoked the formation of cytosolic granules composed of K48-Ub and FG-Nups to form in TorsinKO cells (Fig. 5b, Extended Data Fig. 4a). This phenotype can be rescued by an siRNA-resistant Nup98 construct but not by Nup96, which is derived from a Nup98–96 precursor protein through proteolytic cleavage [45] (Extended Data Fig. 4b–e). We also examined whether other bleb components became incorporated into these cytosolic granules. Both MLF2-GFP and DNAJB6 also localize to these cytosolic puncta (Fig. 5c) while HSPA1A and HSC70 did not (Extended Data Fig. 4f). While we cannot rule out all possibilities of non-specific effects, knockdown of Nup98 did not significantly perturb nucleo/cytosolic transport (Extended Data Fig. 4g,h) Together, we conclude that the FG-Nup Nup98 is required for the NE bleb sequestration of granules composed of K48-Ub, MLF2, FG-Nups, and chaperones.

Overexpressing MLF2 decreases FG-Nup mislocalization.

When MLF2-GFP was overexpressed in Nup98-depleted TorsinKO cells, we noticed a significant decrease in the amount of FG-Nup incorporation into the cytosolic granule (Fig. 5d,e). We calculated the nuclear/whole cell ratio of nucleoporins in TorsinKO cells under siNT, siNup98, or siNup98 + MLF2-FLAG (Fig. 5e). When Nup98 is depleted, significant FG-Nup mislocalization occurs and the nuclear/whole cell nucleoporin ratio decreases (Fig. 5e). However, when MLF2-FLAG is overexpressed in Nup98-depleted cells, the nuclear/whole cell nucleoporin ratio significantly increases (Fig. 5e). Thus, MLF2 may possess an FG-Nup directed activity.

Blebs share properties with condensates.

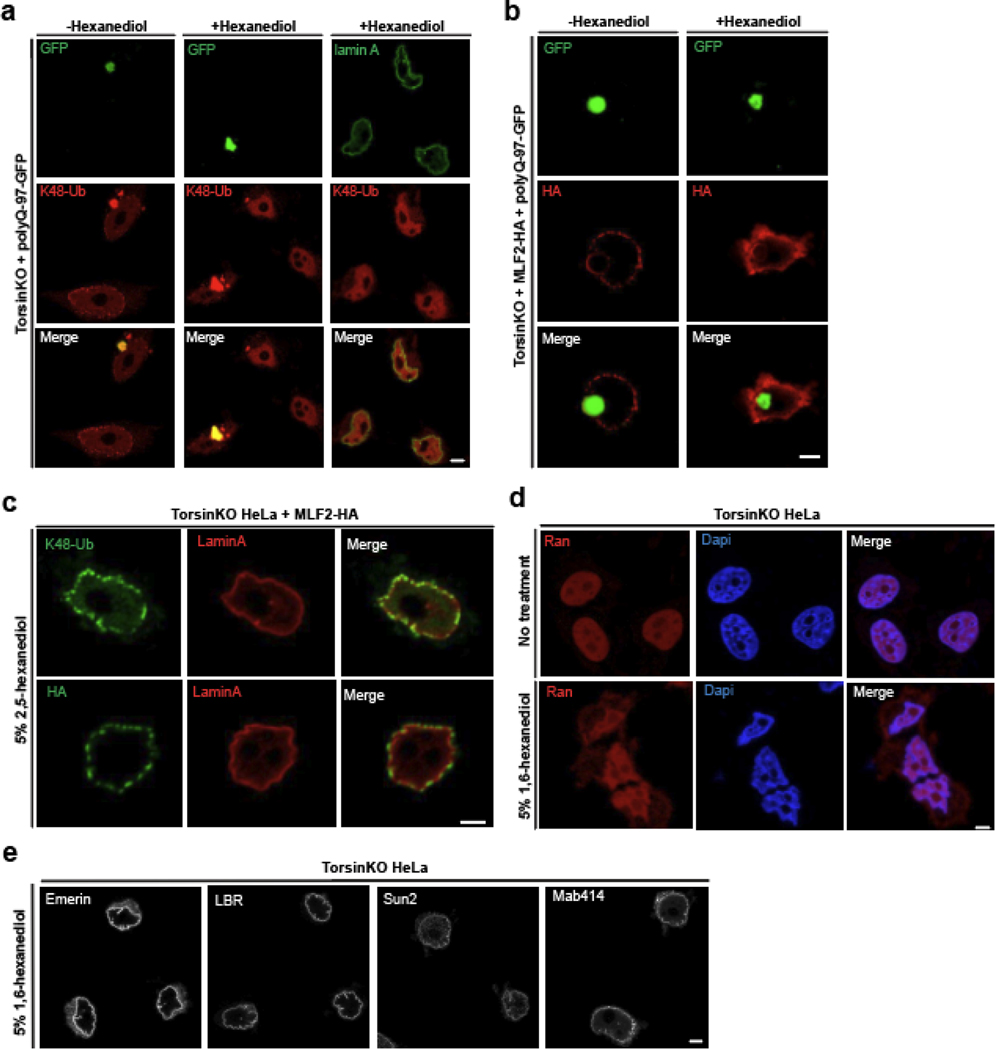

The cytosolic granules that form upon siNup98 in TorsinKO cells were often spherical (Fig. 5b–d), prompting us to ask whether they may represent condensates. One strategy to probe the nature of such structures is to determine their sensitivity to 1,6-hexanediol, an alcohol that interrupts weak hydrophobic contacts and dissolves many phase separated condensates while preserving the integrity of the nuclear membrane (Extended Data Fig. 5e) [46, 47]. When exposed to 5% 1,6-hexanediol, the K48-Ub and MLF2-GFP granules typically observed in TorsinKO cells under siNup98 conditions were dissolved (Fig. 5f,g). This suggests that these cytosolic granules are indeed condensates potentially driven by FG-Nups.

The functional yeast ortholog of Nup98, Nup116, serves as “Velcro” to recruit other FG-Nups during NPC assembly [48]. We hypothesized that Nup98 may direct FG-Nups to blebs. When we treat TorsinKO cells with 1,6-hexanediol, K48-Ub and MLF2-HA are released from blebs despite the NE remaining intact (Fig. 5h,i). To rule out that blebs contain terminally aggregated protein, we overexpressed polyQ-97-GFP and found the aggregates to be resistant to 1,6-hexanediol treatment (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Furthermore, the K48-Ub and MLF2 sequestered inside blebs was not dissociated by 2,5-hexanediol (Extended Data Fig. 5c) [49]. We note that the NPC permeability barrier established by FG-Nups was, as expected [46], partially broken down by 1,6-hexanediol (Extended Data Fig. 5d).

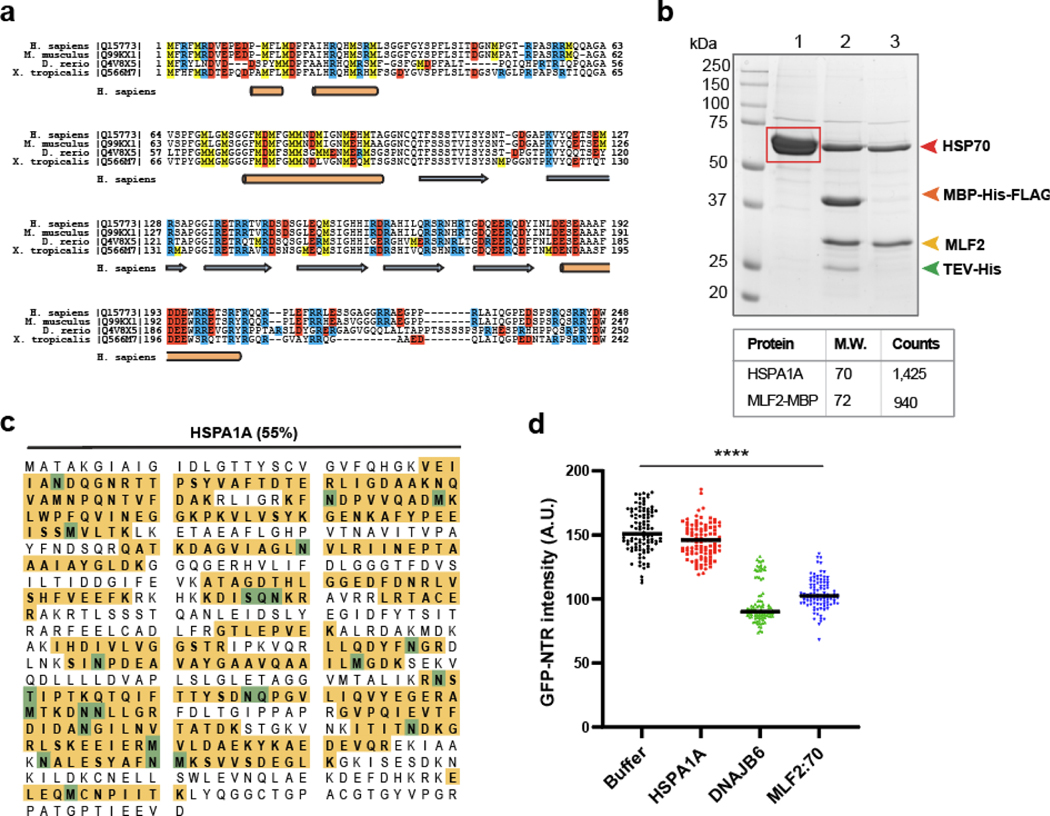

MLF2 and DNAJB6b immerse into FG-rich phases in vitro.

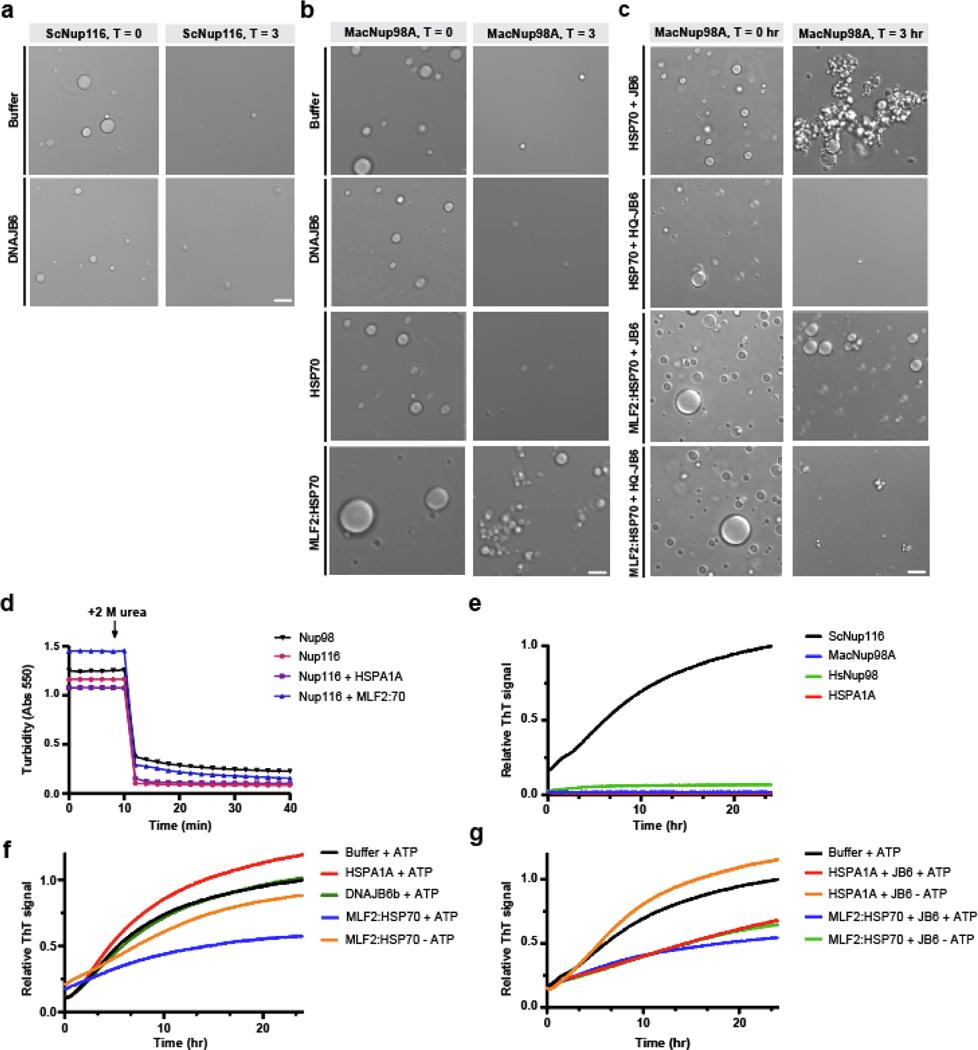

MLF2 has a strikingly high methionine and arginine content (Extended Data Fig. 6a), two residues that specifically facilitate interactions with FG-domains [50]. Thus, the recruitment of MLF2 to blebs could rely on an FG-driven condensate. To address this, we purified FG-domains from the Homo sapiens Nup98, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Nup116, and Tetrahymena thermophila MacNup98A. Under denaturing conditions, these FG-domains do not phase separate [51]. However, upon dilution into buffer without denaturants, these FG-domains form condensates exhibiting selective permeability [50, 51] (Fig. 6a). We formed FG-rich phases and validated their selectivity with purified GFP derivatives 3B7C-GFP and sinGFP4a [50] (Fig. 6a). 3B7C-GFP behaves like an NTR while sinGFP4a is excluded from the phases [50] (Fig. 6a).

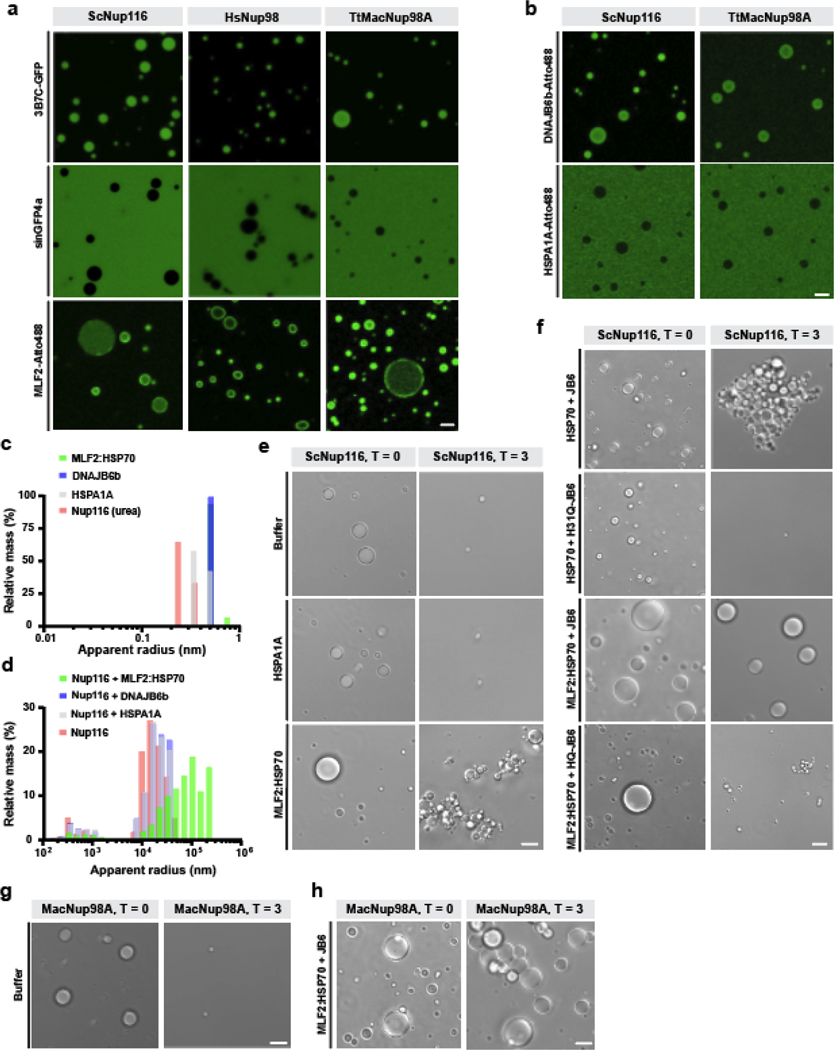

Figure 6. MLF2 interacts with FG-rich phases and preserves condensate integrity over time with HSP70 and DNAJB6.

a, Atto488-tagged MLF2 interacts with phylogenetically diverse FG-Nups. Purified, label-free ScNup116, HsNup98, or TtMacNup98A FG-domains were diluted from 500 μM stocks in 2 M urea to 10 μM in tris-buffered saline (TBS) to form condensates. Condensates were formed at room temperature in TBS containing 5 μM 3B7C-GFP, sinGFP4a, or MLF2-Atto488. b, HSPA1A-Atto488 is excluded from ScNup116 and TtMacNup98A condensates while DNAJB6b-Atto488 readily immerses into FG-rich phases. c, Solutions of 5 μM MLF2:HSP70, DNAJB6b, HSPA1A, or urea-denatured ScNup116 were analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Datasets of 100 reads with five-second acquisition times were collected for each condition. d, Solutions of 10 μM ScNup116 were formed in TBS with no additional protein (pink), 5 μM DNAJB6b (blue), 5 μM HSPA1A (grey), or 5 μM MLF2:HSP70 (green). Condensate size distributions were analyzed by DLS as described above. e, Phase contrast images of 10 μM ScNup116 condensates formed in the presence of 5 μM HSPA1A or 5 μM MLF2:HSP70. Images were taken immediately after condensates formation (T = 0) or after three hours of incubation at 30ºC (T = 3) in the presence of ATP. Note that the buffer condition is also shown in Extended Data Fig. 7a. f, Phase contrast images of 10 μM ScNup116 condensates formed in the presence of 5 μM HSPA1A or 5 μM of MLF2:HSP70 and 2.5 μM DNAJB6b constructs. Note the H31Q-DNAJB6b mutant cannot interact with HSP70. Images were taken at timepoints described in panel (e). g, Phase contrast images of 10 μM ThMacNup98A condensates immediately following formation or after three hours of incubation as described above. Note that the buffer condition is also shown in Extended Data Fig. 7b. h, Images of 10 μM ThMacNup98A condensates formed in the presence of 5 μM MLF2:HSP70 and 2.5 μM DNAJB6b at the zero timepoint or after three hours of incubation. Note that this condition is also shown in Extended Data Fig. 7c. Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels. Source numerical data are available in source data.

In Torsin-deficient cells, MLF2 localizes to FG-rich blebs where it interacts with chaperones (Fig. 4b–d). HSP70s represent the most abundant of these (Fig. 4b,c). Thus, to recapitulate the bleb lumen environment in vitro, we purified the MLF2:HSP70 complex from mammalian cells (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c) and tested the ability for MLF2 to immerse into FG-rich condensates (Fig. 6a). We tagged MLF2 with a C-terminal Atto488 label and found it immersed into ScNup116 and TtMacNup98A phases but remained mostly at the surface of HsNup98 condensates (Fig. 6a). To exclude the possibility that HSP70 brings MLF2:HSP70 into the phase, we purified and Atto488 tagged HSPA1A (Fig. 6b). Unlike DNAJB6b-Atto488, which we find to immerse into FG condensates, HSPA1A-Atto488 is nearly completely excluded (Fig. 6b). Thus, HSP70 is unlikely to be the major factor driving MLF2:HSP70 into Nup phases. Taken together, we conclude that MLF2 and DNAJB6b interact with phylogenetically diverse FG-domains.

Condensates have distinct properties when formed with MLF2.

FG-rich condensates formed in the presence of MLF2:HSP70 were significantly larger compared to other conditions (Fig. 6a). To quantify this effect, we performed dynamic light scattering (DLS) to obtain the distribution of apparent radii for ScNup116 condensates under different conditions. When solutions containing MLF2:HSP70, DNAJB6b, or denatured Nup116 were analyzed by DLS, small condensates (<10 nm radius) corresponding to protein monomers were detected (Fig. 6c). Diluting ScNup116 into non-denaturing buffer caused significantly larger condensates (≥1,000 nm radius) to be detected as condensation occurred (Fig. 6d).

When ScNup116 condensates were formed in the presence of DNAJB6b or HSPA1A, we observed condensates with a similar size distribution compared to ScNup116 alone (Fig. 6d). However, when the ScNup116 condensates were formed in the presence of MLF2:HSP70, a pronounced shift towards larger condensate sizes occurred (Fig. 6d). This suggests that MLF2:HSP70 possesses an FG-Nup directed activity.

DNAJB6b and MLF2:HSP70 compete with an NTR-like molecule.

An important consequence of DNAJB6b or MLF2:HSP70 interacting with FG-rich condensates is that they prevent the full partition of 3B7C-GFP into the phase (Extended Data Fig. 6d). This is not the case when condensates are formed in the presence of HSPA1A, which is excluded from the phase (Fig. 6b, Extended Data Fig. 6d). While this may result from an excluded volume effect or from competition for binding sites in FG domains, this observation may explain why blebs are completely devoid of NTRs despite harboring FG-Nups (Supplemental Tables 1,2) [18, 22].

Chaperones preserve FG-Nup condensate integrity over time.

After three hours in solution, ScNup116 and TtMacNup98A condensates largely disassociate (Fig. 6e,g, Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). In the presence of MLF2:HSP70, however, the condensates shrink but remain intact (Fig. 6e, Extended Data Fig. 7b). When WT DNAJB6b is included with MLF2:HSP70, ScNup116 and TtMacNup98A condensates remain largely unchanged after three hours (Fig. 6e,h). In contrast, when the H31Q-DNAJB6b mutant is included, which cannot interact with HSP70, the FG-rich condensates are strongly disassociated (Fig. 6f, Extended Data Fig. 7c). This illustrates a dominant-negative FG-directed activity for H31Q-DNAJB6b (Fig. 6e,f). While the WT DNAJB6b:HSP70 complex preserves small clusters of condensates, this was not as uniform or penetrant as the effect by the complete MLF2:HSP70:DNAJB6b complex (Fig. 6f–h, Extended Data Fig. 7c). Taken together, these data suggest that the MLF2:HSP70 complex maintains FG-rich condensates over time, an activity that is enhanced by DNAJB6b.

The MLF2:HSP70 complex reduces FG-Nup amyloid formation.

The ScNup116 FG domain is known to form cross-β amyloid-like structures [51, 52]. Initially, ScNup116 does not form amyloids as the condensates are readily reversable (Extended Data Fig. 7d). The transition to amyloids is detectable by the dye Thioflavin-T (ThT), which fluoresces upon interacting with amyloids (Extended Data Fig. 7e). We monitored ThT fluorescence of solutions containing ScNup116 plus HSPA1A, DNAJB6b, or MLF2:HSP70 (Extended Data Fig. 7f,g). While neither HSPA1A nor DNAJB6b affected ScNup116 amyloid formation, MLF2:HSP70 reduced it by approximately half in an ATP-dependent manner even at a sub-stoichiometric concentration (Extended Data Fig. 7f). We found that the DNAJB6b-HSP70 complex has a similar ATP-dependent, sub-stoichiometric ability to reduce amyloid formation (Extended Data Fig. 7g). Amyloid formation was most potently suppressed in the presence of ATP upon inclusion of MLF2, HSPA1A, and DNAJB6 (Extended Data Fig. 7g). These data reveal an additional FG-Nup directed activity of the chaperone network identified herein.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a virally-derived model substrate (Δ133 ORF10, Fig. 1) to explore the molecular composition and cellular consequences of NE herniations that arise in disease models of primary dystonia. While NE blebs are striking morphological features in dystonia model systems and found in other experimental settings [53], it has generally been unclear whether NE blebs contribute to disease development. Using Δ133 ORF10 and the APEX-derivatized MLF2 in a comparative proteomics approach, we found that blebs are highly enriched for the FG-Nup Nup98 and specific members of the HSP40 and HSP70 chaperone family (Fig. 2). In cells with perturbed Torsin function, these chaperones become tightly sequestered within the lumen of NE blebs and are titrated away from their normal subcellular localization (Fig. 3). Importantly, this sequestration also occurs in primary neurons with perturbed Torsin function (Fig. 3). This raises the question of what mechanisms are at work to cause this unusual sequestration.

We demonstrate that NE blebs contain FG-rich condensates (Fig. 5) that impose two proteotoxic challenges: an unprecedented degree of chaperone sequestration that is typically only observed upon overexpression of disease alleles, and a profound stabilization of normally short-lived proteins (Fig. 1e,f). We furthermore find that MLF2 affects FG-domain condensation (Fig. 5d,f, Fig. 6, Extended Data Fig. 7). Our observation that MLF2 expression results in a near-complete re-distribution of DNAJB6–a critical factor for suppressing proteotoxic aggregation [41, 43] – from poly-Q inclusions to NE blebs (Fig. 4e,f) establishes MLF2 as an important player in protein homeostasis. Taken together, we uncover a direct proteotoxic contribution of blebs to DYT1 dystonia pathology and a role for MLF2, HSPA1A, and DNAJB6 in the formation and maintenance of FG-rich phases.

While NTRs function as FG-Nup-directed chaperones during postmitotic NPC assembly [54], interphase NPC biogenesis follows a distinct insertion pathway [55]. We demonstrate that MLF2 overexpression prevents the ectopic accumulation of FG-Nups upon Nup98 depletion (Fig. 5d,e). It is therefore tempting to speculate that non-NTR chaperones like MLF2 and DNAJB6 function during interphase NPC biogenesis to prevent premature FG-Nup assembly. Indeed, Kuiper et al. have independently assigned DNAJB6 to a role in NPC biogenesis [56]. In vitro, we find that MLF2:HSP70 and DNAJB6 prevent the full partition of NTR-like molecules into FG-Nup phases (Extended Data Fig. 6d). While this may be explained by excluded volume effects or a competition mechanism, either scenario would result in fewer NTR-FG domain interactions, consistent with our observation that bulk nuclear transport cargo is excluded from FG-rich NE blebs [18, 22].

We previously reported that MLF2-GFP accumulates at sites of NE developing membrane curvature in Torsin-deficient cells [22]. This clustering of MLF2 juxtaposed against the curved NE may represent nucleation events of FG-Nups undergoing condensation at sites of de novo interphase NPC assembly. This in vivo role for MLF2 would reflect the activity we report in vitro (Fig. 6c–h, Extended Data Fig. 7).

Our proteomic experiments reveal a specific enrichment of class B HSP40s inside blebs. While future work will be required to understand whether an active exclusion of other HSP40 classes exists, we propose that DNAJB2 and DNAJB6 are recruited by the specific properties of these HSP40s. Future studies are warranted to understand whether MLF2 interacts with other HSP40 classes, and if other HSP40s can immerse into condensates as exemplified here for DNAJB6 (Fig. 6b).

The observation that mutations in ER/NE-luminal Torsin ATPases give rise to an indirect proteotoxic mechanism across compartmental borders is unexpected. This feature adds a unique disease mechanism to the growing list of movement disorders with functional ties between liquid-liquid phase separation, nuclear transport machinery, and proteotoxicity [57–59]. Our finding that NE blebs exert a twofold proteotoxicity also represents a distinct pathological mechanism from the documented nuclear transport defects that arise in Torsin-deficient cells due to compromised NPC assembly [12, 20–22] (Extended Data Fig. 8).

We propose that this dual proteotoxicity mechanism contributes to DYT1 dystonia’s unusual disease manifestation. Unlike other congenital movement disorders, DYT1 dystonia is characterized by a limited window of onset. After the age of 30, carriers of the DYT1 mutation will never develop the disease [60]. Furthermore, the disease displays a reduced penetration as only one third of all mutation carriers develop DYT1 dystonia [11]. These features may be explained by the fact that blebs are transient structures that resolve in model organisms after TorsinB is upregulated [16, 61]. Thus, the proteotoxicity imposed by blebs is confined to a specific window in life—likely closing before the age of 30. We propose that sequestered chaperones and accumulated short-lived proteins confer this window of vulnerability and generate a high but potentially manageable degree of proteotoxic stress. Further insult on the PQC machinery that may normally be inconsequential could cause severe problems in these pre-sensitized cells. This model describes a stochastic and previously underappreciated influence on disease manifestation (Extended Data Fig. 8). While additional studies will be required to test these ideas, our data provide a strong motivation to investigate pharmacological modulators of the cellular PQC system for DYT1 dystonia prevention and management.

Methods

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. All experiments using animal models were approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee as described in protocol 2022–07912.

Antibodies and reagents

All cell lines, bacterial strains, antibodies, reagents, and oligonucleotides used in this study can be found in Supplemental tables 5–8.

Cell culture and cell lines

HeLa, SH-SY5Y, and HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% v/v FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100 U/mL of penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were routinely checked for mycoplasma and determined to be free of contamination through the absence of extranuclear Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) staining.

Expi293 suspension cells were cultured at 37ºC in flat-bottom shaking flasks in preformulated Expi293 Expression Media (Gibco, A1435102) in an 8% CO2 atmosphere.

To generate stable HeLa cell lines expressing MLF2-APEX2-HA, 6 μg was transiently transfected into HEK293T cells along with 2 μg of MMLV gag/pol and 1 μg of the viral envelope protein VSV-G. After 72 hours of expression, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter before storage at −80°C. HeLa cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transduced with 100 μL viral supernatant plus 4 μg/mL polybrene reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). After 24 hours, media was switched to contain 1 μg/mL of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Antibiotic selection was performed for 7 days before the dox-inducible MLF2-APEX2-HA expression was verified.

Plasmids, transient RNAi knockdowns, and transient transfections

KSHV ORF10-HA was synthesized by Genscript into the pcDNA3.1 vector. Δ133 ORF10-HA was cloned from the full lenth cDNA into pcDNA3.1. Plasmids containing the deubiquitylating enzyme M48 [35] were a gift from Hidde L. Ploegh (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA). MLF2-HA and MLF2-GFP were cloned into pcDNA3.1 or pEGFP-N1 using standard molecular cloning techniques. polyQ-72-GFP and polyQ-97-GFP were a gift from Susan Lindquist (Addgene plasmid # 1179; http://n2t.net/addgene:1179; RRID:Addgene_1179, Addgene plasmid # 1180; http://n2t.net/addgene:1180; RRID:Addgene_1180) [62]. These polyQ constructs were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 using standard cloning techniques.

MLF2-APEX2-HA was cloned into the pRetroX-Tight-Pur vector from pcDNA3.1 using standard cloning techniques. mito-V5-APEX2 was a gift from Alice Ting (Addgene plasmid # 72480; http://n2t.net/addgene:72480; RRID:Addgene_72480) [36].

DNAJB6b-ΔG/F-HA and DNAJB6b-ΔG/F-S/T-HA were synthesized by Genscript into the pcDNA3.1 vector. The G/F-rich region was defined as G72-G131 and the S/T-rich region as S132-T195. All phenylalanine residues within these regions were mutated to alanine to generate the DNAJB6b mutants.

pCMV-PV-NES-GFP was a gift from Anton Bennett (Addgene plasmid # 17301; http://n2t.net/addgene:17301; RRID:Addgene_17301) [63].

The plasmids containing His-tagged 3B7C-GFP, sinGFP4a, HsNup98, TtMacNup98A, and ScNup116 FG domains were gifts from Dirk Görlich (Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen, Germany) [50, 51].

MLF2-LPEXTG-Tev-MBP-His-FLAG, DNAJB6b-LPETG-His and HSPA1A-LPETG-His were synthesized by Genscript into pcDNA3.1 (for the MLF2 construct) or pET11a (DNAJB6b and HSPA1A constructs). The LPETG motif was included as a sortase enzyme recognition motif for tagging with the Atto488 dye.

Nontargeting RNAi and RNAi targeting MLF2, DNAJB6, and Nup98 were performed with SMARTpool oligos from Horizon Discovery. Knockdown efficiency was validated by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using iQ SYBR Green mix with a CFX Real-Time PCR 639 Detection System (Bio-Rad). For each knockdown, we employed the comparative Ct method using the internal control transcript RPL32 [22]. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies.

All plasmid transfections were performed with Lipfectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions and allowed to express for 24 hours prior to analyses. All RNAi knockdowns were performed with Lipfectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions and allowed to incubate for 48 hours before analyses.

CRISPR/Cas9 generation of MLF2 knockout

To generate MLF2 KO HeLa cells, we employed the CRISPR/Cas9 system [64] as previously implemented [65]. Briefly, a guide RNA targeting MLF2 was cloned into the px459 vector and transfected into HeLa cells. pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (px459) V2.0 was a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid # 62988; http://n2t.net/addgene:62988; RRID:Addgene_62988) [66]. The transfected cells underwent antibiotic selection for 48 hours via treatment with 0.4 μg/mL puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After selection, cells were seeded at a low density such that single-cell colonies could be isolated after 10 days in culture. These colonies were expanded and screened for MLF2 knockout by genotyping PCR [65].

Hippocampal cultures, transfection, and immunofluorescence

Hippocampal cultures were performed using seven mixed sex BALB/c P0 pups in accordance with IACUC protocol number 2022–07912 (Yale University School of Medicine IACUC). Hypothermia was induced in pups, followed by decapitation and hippocampal dissection. Hippocampi were dissociated using 200 units Papain (Worthington LS003124, 200 U) and were plated on 14 mm poly-D-lysine coated coverslips in a 24 well dish at a density of 150,000 cells/well. Neurons were transfected at DIV 4 with 1 μL per reaction of Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a concentration of 0.6 μg per plasmid, for a total of 1.8 μg of DNA. Neurons were fixed at DIV 7 with 4% v/v paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS at room temperature for 15 minutes, permeabilized with 0.1% v/v Triton-X for 15 minutes, blocked with 1% w/v BSA for one hour, and stained with primary antibodies in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C (1:1000 rat HA, 1:200 rabbit TorsinA). Following the primary stain, coverslips were washed with PBST three times for 5 minutes, followed by a secondary antibody stain in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature (1:1000 rat Alexa 568 and rabbit 633). Coverslips were washed with PBST three times for 5 minutes, stained with DAPI for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed with PBST three times for 5 minutes, and mounted in Aqua-Mount (Lerner Laboratories).

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

HeLa and SH-SY5Y cells were grown on coverslips and prepared for IF by fixing in 4% v/v PFA (Thermo Fisher Scientific), permeabilized in 0.1% v/v Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes, then blocked in 4% w/v bovine serum albumin (BSA). Primary antibodies were diluted into 4% w/v BSA and incubated with coverslips for 45 minutes at RT. After extensive washing with PBS, fluorescent secondary antibodies were diluted in 4% w/v BSA and incubated with coverslips for 45 minutes. Cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) before mounting onto slides with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech).

For hexanediol experiments, cells were incubated for five minutes with complete DMEM containing 5% w/v hexanediol (Millipore) before fixing in 4% v/v PFA and processing for IF as described above. VER-155008 was dissolved in DMSO at a stock concentration of 10 mM and used at a final concentration of 20 μM for 24 hours prior to fixation for IF.

Phase separated condensates were imaged by spotting a 10 μL volume of the indicated conditions onto a glass bottom dish (WillCo Wells). To visualize effects of protein on Nups after three hours, FG phases were formed in supplemented TBS (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM Mg(CH3COO)2, 10 mM K(CH3COO)2, 4 mM creatine phosphate, 0.25 μL creatine kinase, 2 mM ATP). Where indicated, ATP was omitted from the supplemented TBS (the ATP regenerating system remained). Incubation took place at 30ºC.

All images were collected on an LSM 880 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss) with a C Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 oil DIC M27 objective using ZEN v2.1 & v3.4 software (Zeiss).

Spectroscopic measurements of Nup solutions

Turbidity of Nup solutions was measured at an excitation and emission wavelength of 550 nm (Synergy Mx, BioTek Instruments, Inc).

To monitor ScNup116 amyloid formation, Nups were diluted into supplemented TBS with the indicated proteins. Solutions were brought to 2 μM ThT. Bottom reads of ThT fluorescence (excitation 440 nm, emission 480 nm) were captured every two minutes at 30ºC for 24 hours (Synergy Mx, BioTek Instruments, Inc).

Cycloheximide chase

WT and TorsinKO cells were plated in a 10 cm dish and transfected with Δ133 ORF10-HA. After 24 hours of expression, each cell line was trypsinized and split into two tubes. Tubes were incubated at 37°C with gentle shaking and treated with either DMSO or 100 μg/mL CHX and aliquots were taken at 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 hours post treatment. Cells were collected via centrifugation and subjected to immunoblot for analyses.

Immunoprecipitation, mass spectrometry preparation, and immunoblot analysis

For native IP experiments, cells were transfected with the indicated constructs 24 hours before harvesting. Cells were lysed in NET buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.5% v/v NP-40) supplemented with EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 5 mM NEM (Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoprecipitation was conducted with pre-cleared lysates on anti-HA affinity matrix (Roche), magnetic beads conjugated to streptavidin, or magnetic protein G beads (Pierce) non-covalently coupled to anti-HSPA1A. Stable interactions were eluted for immunoblot analyses in 30 μL of 2x SDS reducing buffer and heated at 70°C for five minutes. For mass spectrometry applications, protein complexes were briefly run into SDS-PAGE gels, stained with SimplyBlue Safe Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before bands of 2–4 mm were extracted. Gel bands were submitted to the MS & Proteomics Resource at the Yale University Keck Biotechnology Laboratory.

Radioimmunoprecipitations were carried out in as described previously [4, 67]. Briefly, metabolically labeled cells were grown in complete DMEM containing 150 μCi/mL 35S-Cys/Met labeling mix (PerkinElmer) for 16 hours prior to lysis in NET buffer. Co-eluting protein were detected by autoradiography and imaged on a Typhoon laser-scanning platform (Cytiva).

Immunoblotting was carried out with IP eluates or cell lysates in supplemented NET buffer. Equal micrograms of protein were resolved in SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in 5% w/v milk in PBS + 0.1% v/v Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich). Primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer. Blots were visualized by chemiluminescence on a ChemiDoc Gel Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

APEX2 reaction and NE enrichment

To induce the expression of MLF2-APEX2-HA, cells were treated with 500 μg/mL dox for 24 hours. After 24 hours, cells were incubated for 30 minutes with complete DMEM containing 500 μM biotin phenol. For the APEX2 reaction, cells were treated with 1 mM H2O2 for one minute before quenching by washing the plates three times with quenching buffer (PBS, pH 7.4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Trolox, 10 mM sodium ascorbate, 10 mM sodium azide). Cells were collected and enriched for NE fractions as described previously [22, 68]. Briefly, cells were gently pelleted in buffer containing 250 mM sucrose and homogenized via trituration through a 25-guage needle. The homogenates were layered onto a 0.9 M sucrose buffer and spun down. The pellets (membrane fractions and nuclei) were solubilized overnight in buffer without sucrose containing benzonase, heparin, NEM, and protease inhibitors. The solubilized nuclei were spun at 15,000 x g for 45 minutes and the supernatant was collected as the nucleoplasm and pellet as the NE/ER enriched fraction. The ER/NE fraction was solubilized in 8 M urea and equal amounts of protein were loaded onto streptavidin beads for capture of biotinylated protein, which were analyzed by immunoblot or mass spectrometry.

Transmission electron microscopy and immunogold labeling

Electron microscopy (EM) and immunogold labeling was performed as previously described [18, 22] at the Yale School of Medicine’s Center for Cellular and Molecular Imaging. Briefly, cells were fixed by high-pressure freezing (Leica EM HPM100) and freeze substitution (Leica AFS) was carried out at 2,000 pounds/square inch in 0.1% w/v uranyl acetate/acetone. Samples were infiltrated into Lowicryl HM20 resin (Electron Microscopy Science) and sectioned onto Formvar/carbon-coated nickel grids for immunolabeling.

Samples were blocked in 1% w/v fish skin gelatin, then incubated with primary antibodies diluted 1:50 in blocking buffer. 10 nm protein A-gold particles (Utrecht Medical Center) were used to detect the primary antibodies and grids were stained with 2% w/v uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Images were captured with an FEI Tecnai Biotwin TEM at 80Kv equipped with a Morada CCD and iTEM (Olympus) software.

Recombinant protein expression and purification

HsNup98, TtMacNup98A, and ScNup116 [50, 51] were purified from BL21(DE3) E. coli strains under denaturing conditions by virtue of an N-terminal His18 tag. Cell pellets containing the FG domains were resuspended in denaturing lysis buffer (8 M urea, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 20 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-me, 2 mM PMSF). Solubilized His-tagged Nups were complexed with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) at 4ºC for 16 hours before the columns were extensively washed at room temperature (6 M urea, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 25 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-me). Protein was eluted in room temperature elution buffer (6 M urea, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 400 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-me) and dialyzed overnight at 4°C into UTS buffer (2 M urea, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4)). Finally, the dialyzed Nup was concentrated to 500 μM using a Macrosep 10,000 MWCO centrifugation unit (Pall Corporation).

Phase separated condensates were formed by diluting 500 μM Nup stock solutions in denaturing UTS buffer into tris-buffered saline (TBS; 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl) to a final concentration of 10 μM [51].

His-tagged GFP variants were purified as previously described [50]. BL21(DE3) [50, 69] cell pellets containing His-Brachypodium distachyon (bd)-SUMO-sinGFP4a or His-bdSUMO-3B7C-GFP[50, 69] were resuspended in resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-Me, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF) and passed through the French Press. His-tagged proteins were bound to Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) for 1 hour at 4°C before washing in resuspension buffer. GFP constructs were eluted in resuspension buffer containing 400 mM imidazole, then concentrated with a Macrosep 10,000 MWCO centrifugation unit (Pall Corporation). Final concentrates were buffer-exchanged into TBS.

DNAJB6b-LPETG-His10 was purified as previously described [70]. BL21(DE3) cell pellets were resuspended in resuspension buffer (100 mM Tris (pH 8), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM β-Me, 1 mM PMSF) and were passed through the French Press DNAJB6b-LPETG-His10 was solubilized from inclusion bodies in pellet buffer (100 mM Tris (pH 8), 8 M urea, 150 mM KCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-Me, 1 mM PMSF). DNAJB6b-LPETG-His10 was allowed to bind Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) for 1 hour at 4°C. The matrix was washed (100 mM Tris (pH 8), 8 M urea, 150 mM KCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-Me) and DNAJB6-LPETG-His10 was eluted in elution buffer (100 mM Tris (pH 8), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM β-Me, 350 mM imidazole). The protein was dialyzed overnight into final buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl) and concentrated with a Macrosep 10,000 MWCO centrifugation unit (Pall Corporation).

HSPA1A-LPETG-His10-FLAG was purified from BL21(DE3) cells resuspended in resuspension buffer (100 mM HEPES (pH 8), 500 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 10 mM β-Me, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF) and passed through the French Press The supernatant was applied to Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) for 1 hour at 4ºC. The matrix was washed (30 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 20 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-Me) and protein was eluted in wash buffer with 400 mM imidazole. Protein was dialyzed overnight into TBS and concentrated as described above.

The MLF2-LPETG-TEV-MBP-His-FLAG:HSP70 complex was purified from a mammalian Expi293 suspension system. Cells were harvested after 72 hours of expression and pellets were lysed in ice cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% w/v DDM, 10% v/v glycerol, protease inhibitor tablet (Roche)). Clarified supernatant was applied to anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma-Aldrich) and allowed to bind overnight at 4°C. The matrix was washed (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% w/v DDM), then washed with buffer minus detergent. Protein was eluted in final buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.3 mg/mL FLAG peptide) for 1 hour at 4°C. TEV enzyme (New England BioLabs) was added to the elution and the mixture was dialyzed overnight into TBS. The resulting MLF2:HSP70 complex was concentrated as described above.

Atto-tagging via the sortase reaction

To produce Atto488-tagged MLF2, DNAJB6b, and HSPA1A, constructs were purified with an LPETG sortase recognition sequence between the C-terminal end and the downstream purification tag. This motif is recognized by the transpeptidase sortase, which catalyzes a reaction wherein a molecule harboring a poly-glycine label is attached to the LPETG sequence [71]. Reactions were carried out using purified MLF2-LPETG, DNAJB6b-LPETG, or HSPA1A-LPETG and the Sortag-IT™ ATTO 488 Labeling Kit (Active Motif) according to manufacturer’s instructions. After the sortase reaction, free dye was removed from the Atto-tagged proteins by washing extensively with TBS in Amicon Ultra-0.5 mL Centrifugal Filters (MilliporeSigma), then running through a PD MiniTrap desalting column (Cytiva).

Dynamic light scattering

DLS was used to assess the size distribution of FG-rich condensates forming the in presence or absence of MLF2:HSP70. Measurements were taken on a DynaPro Titan DLS instrument (Wyatt Technologies) at 25°C and data were analyzed using DYNAMICS software (Wyatt Technologies). 10 μL reactions of 10 μM ScNup116 in TBS containing no additional protein, 5 μM MLF2:HSP70, 5 μM HSPA1A, or 5 μM DNAJB6b were allowed to form for one minute before diluting 1:10 in TBS. 30 μL of this dilution was transferred to a quartz cuvette and datasets of 100 measurements of five-second acquisition times were collected.

Image processing

The number of immunogold beads against HSPA1A or DNAJB6 was manually counted for 400 μm2 centered around the NE from WT or TorsinKO cells (Fig. 3c). The number of immunogold beads was quantified for a square of 2 μm by 2 μm with the NE in the middle. This value was obtained for 100 2×2 μm squares centered around the NE.

The ratio of DNAJB6 within polyQ aggregates compared to the whole cell was calculated using Fiji Software [72] (Fig. 4f). The DNAJB6 antibody signal intensity was obtained by defining a region of interest (ROI) within the polyQ aggregate (Q), then of the whole cell (W). The ratio of Q/W was calculated for at least eight cells/condition.

The rescue effect of MLF2 on FG-Nup mislocalization (Fig. 5e) was determined for 94 cells/condition. The nucleoporin (Mab414 antibody) signal intensity in the whole cell and the nucleus was quantified using Fiji by selecting these as ROIs. From these values, the ratio of nuclear Mab414 intensity to whole cell intensity was calculated.

The presence of cytosolic granules under siNup98 conditions (Fig. 5g, Extended Data Fig. 4c) was determined by visualizing the presence or absence of cytosolic K48-Ub deposits for 300 cells/condition.

To quantify the number of NE-associated K48-Ub foci in TorsinKO cells treated with 1,6-hexanediol (Fig. 5i), the nucleus was selected in Fiji as the region of interest (ROI) and the number of foci was quantified as previously performed [18, 22]. The “Find Maxima” function was employed with a noise tolerance of 10. Foci were quantified for 100 cells/condition.

The nuclear to cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio of the Ran GTPase under siNT or siNup98 was quantified using CellProfiler software [73] (Extended Data Fig. 4h). Briefly, the Ran IF signal was quantified within cell regions co-localizing or not co-localizing with DAPI stain to define the nuclear and cytoplasmic regions, respectively. These values were used to calculate the N/C ratio for 85 cells/condition.

The 3B7C-GFP signal intensity was determined in Fiji using the measure function (Extended Data Fig. 6d). The center of Nup condensates was selected as an ROI, then the average GFP signal intensity was measured for 100 condensates/condition.

Statistics and reproducibility

All data were considered representative by repeating experiments at least three times with similar results or using three independent samples for analysis. Datasets were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. If found to be normally distributed, datasets were analyzed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Datasets not normally distributed were analyzed with a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test. GraphPad Prism 9.4.0 was used for all statistical analyses. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Data are displayed with the mean value indicated and error bars showing the standard deviation (SD). No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. The experiments were not randomized.

Data availability statement

Mass spectrometry datasets are uploaded to the massIVE database (Supplemental Table 1 accession MSV000090177. Supplemental Table 2 accession number MSV000090186. Supplemental Table 3 accession number MSV000090187. Supplemental Table 4 accession number MSV000090188). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the following accession numbers: Supplemental Table 1, PXD036262. Supplemental Table 2, PXD036264. Supplemental Table 3, PXD036266. Supplemental Table 4, PXD036267. Source data for all graphical representations and unprocessed blot images are provided. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended data 1. NE blebs recruit Δ133 ORF10 in a ubiquitin-dependent manner.

a, Schematic illustration of the NE blebs that form upon Torsin deficiency. In cells with mutant TorsinA, NPC biogenesis is compromised and a subset of nascent NPCs are arrested (ref. [22]). These arrested NPCs form blebs that are enriched for K48-linked ubiquitin (K48-Ub), FG-nucleoporins (FG-Nups), myeloid leukemia factor 2 (MLF2), and a specific chaperone network. The inner nuclear membrane (INM) is depicted in gray, outer nuclear membrane in black. b, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells expressing MLF2-FLAG and Δ133 ORF10-HA fusion constructs. Δ133 ORF10 was fused to the cytomegalovirus deubiquitinase (DUB) domain, M48 (ref. [75]). M48 is a highly active DUB domain that efficiently removes ubiquitin conjugates (ref. [22, 35]). A C23A mutation renders the DUB domain catalytically inactive (ref. [75]). Scale bar, 5 μm.

Extended data 2. Additional abundant molecular chaperones are sequestered into NE blebs of tissue culture cells and primary mouse neurons.

a, Representative image of endogenous HSC70 in WT and TorsinKO HeLa cells. Note that HSC70 re-localizes from diffusely throughout the cell to nuclear rim foci in TorsinKO cells. b, SH-SY5Y cells expressing a dominant-negative TorsinA construct, TorsinA-EQ-HA, sequester HSPA1A and DNAJB6 into NE blebs. Yellow arrowhead, transfected cell. Blue arrow, untransfected cell. Endogenous chaperones (green) form foci around the nuclear rim upon TorsinA-EQ-HA (red) expression. c, Murine DIV4 hippocampal neurons were transfected with GFP and either MLF2-HA alone or in combination with a dominant-negative TorsinA-EQ construct. Constructs were allowed to express for 72 hours before processing the DIV7 cultures for IF. Note that GFP expression was used to distinguish neurons from other cell types in the heterogeneous primary cell culture. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Extended data 3. Chaperones are recruited to blebs by different mechanisms.

a, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells treated with DMSO or VER-155008 for 24 hours. VER-155008 is a small molecule inhibitor of HSP70 ATPase activity, which targets the HSP70 ATP binding pocket and approximates an ADP-bound state (ref. [40]). This compound causes elevated HSPA1A expression and more K48-Ub to accumulate in blebs. Scale bar, 5 μm. b, An IP of HSPA1A from biochemically enriched ER/NE fractions from WT or TorsinKO cells treated with DMSO or VER-155008. c, A co-IP of MLF2-FLAG with HA-tagged DNAJB6 constructs lacking functional G/F-rich or S/T-rich regions in TorsinKO cells. ΔG/F indicates all phenylalanine residues have been mutated to alanine within the G/F-rich region, and ΔG/F-S/T indicates the mutation of the phenylalanine residues within the G/F- and S/T-rich regions. Note that DNAJB6-ΔG/F-S/T-HA retrieves significantly less MLF2-FLAG, suggesting that the S/T-rich region strongly promotes its interaction with MLF2 and recruitment to blebs. d, Representative IF images of the DNAJB6 constructs described in panel (c) in TorsinKO cells. Note that interfering with the S/T-rich region, but not the G/F-rich region, prevents DNAJB6 from reaching the bleb. Scale bar, 5 μm. e, DNAJB6 peptides identified by mass spectrometry from an IP of HSPA1A from TorsinKO cells (see figure 4b–d). Peptides identified by mass spectrometry are highlighted in yellow and post-translationally modified residues are rendered in green. While an IP of HSPA1A from TorsinKO cells identified DNAJB6 with 24% coverage, no DNAJB6 peptides were identified in the HSPA1A IP from WT HeLa cells. See Supplemental Table 3 for complete dataset. Unprocessed blots are available in source data.

Extended data 4. Validation of Nup98 knockdown and effect on nuclear transport.

a, qPCR validation of Nup98 depletion upon 48 hours of 50 nM siRNA treatment. Relative Nup98 transcript levels are normalized to RPL32. b, Nup98 and Nup96 are translated as a single precursor protein that undergoes an autocleavage event to produce the two individual proteins (ref. [45]). Thus, RNAi knockdown of Nup98 results in the simultaneous depletion of Nup96. c-e, To distinguish which protein knockdown produces the cytosolic granules in TorsinKO cells, HA-tagged Nup98 or Nup96 was assessed for the ability to rescue the phenotype under knockdown conditions. c, Quantification of the rescue affect when HA-Nup96 or HA-Nup98 are expressed. The presence of cytosolic inclusions was assessed for 300 cells/condition in ≥20 ROIs. Error bar, SD. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test. ** indicates p = 0.0013. d, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells expressing HA-Nup96 or HA-Nup98 (e) under nontargeting or siNup98–96 conditions. Results are quantified in panel (c). f, Representative IF images of endogenous Hsc70 and HSPA1A in TorsinKO cells upon Nup98 depletion. Note that these HSP70 members are not recruited to the cytosolic granules. g, Representative IF images of the Ran GTPase in TorsinKO cells under 48 hours of siNT or siNup98 conditions. h, The nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio was calculated for GFP-NES in TorsinKO cells under siNT (n = 94) or siNup98 (n = 87) conditions. The ratio was calculated using CellProfiler software (ref. [73]). Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test. Ns, not significant. Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels. Source numerical data are available in source data.

Extended data 5. The effects of 5% 1,6-hexanediol on NE integrity and bleb sensitivity to 2,5-hexanediol.

a, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells expressing polyQ-97-GFP under normal IF conditions or exposed to 5% 1,6-hexanediol for five minutes prior to fixation. Note that the K48-Ub inside polyQ aggregates is not dissolved by 1,6-hexanediol but the K48-Ub inside blebs is sensitive to this alcohol. Lamin A staining demonstrates this 5% 1,6-hexanediol treatment does not break down NE membranes (see also panel (e)). b, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells expressing polyQ-97-GFP and MLF2-HA treated with 5% 1,6-hexanediol for five minutes. A five-minute treatment with 5% 1,6-hexanediol does not dissolve polyQ aggregates but can selectively dissolve the contents of blebs. c, Treatment with the related alcohol 5% w/v 2,5-hexanediol for five minutes does not dissolve the K48-Ub or MLF2-HA sequestered inside blebs. d, Representative IF images of Ran in TorsinKO cells under normal IF conditions or after treatment with 5% 1,6-hexanediol for five minutes. Although the NE membranes are not disassembled by a 5% 1,6-hexanediol, the permeability barrier established by NPCs is lost. 1,6-hexanediol is known to disrupt the hydrophobic contacts required for the cohesion of FG-Nups within the central channel of the NPC (ref. [51]). e, Representative IF images of TorsinKO cells treated with 5% w/v 1,6-hexanediol for five minutes prior to fixation. This treatment does not compromise the integrity of the NE as determined by staining for multiple inner nuclear membrane proteins. Scale bar, 5 μm for all panels.

Extended data 6. MLF2 is a methionine/arginine rich protein and associates with HSPA1A.

a, Multiple sequence alignment of MLF2 homologs from Xenopus tropicalis, Danio rerio, Mus musculus, and Homo sapiens. MLF2 is a methionine- and arginine-rich protein with a high degree of conservation. Methionine residues are highlighted in yellow boxes, arginine in blue, and positively charged residues in red. Orange cylinders indicate alpha helices predicted by AlphaFold [76] and blue arrows represent predicted beta sheets. b, MLF2 purified from Expi293F cells associates with HSPA1A. MLF2 was expressed as a maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion and affinity purified by virtue of FLAG- and His-tags. Lane 1, anti-FLAG resin elution composed of MLF2-Tev-MBP-His-FLAG and associating protein. Red box, gel section analyzed by mass spectrometry. Lane 2, incubation with Tev-His cleaved MBP-His from MLF2. Lane 3, Ni-NTA flowthrough in which MBP-His and Tev-His are removed. Mass spectrometry of the gel segment indicated in lane 1 confirmed the identity of the associating protein as HSPA1A. c, Mass spectrometry analysis of the co-purifying protein from panel (b) revealed 55% coverage of HSPA1A. Identified peptides mapping to HSPA1A are in yellow, post-translationally modified residues in green. See Supplemental Table 4 for complete dataset. d, 10 μM TtMacNup98A condensates were formed in the presence of 5 μM 3B7C-GFP plus 10 μM HSPA1A, DNAJB6Bb, or MLF2:HSP70. 3B7C-GFP signal intensity was measured in the center of 100 condensates/condition. Bars over datapoints indicate the mean intensity value. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney test comparing buffer or HSPA1A conditions to DNAJB6b or MLF2:HSP70. **** indicates p < 0.0001. Source numerical data and unprocessed blots are available in source data.

Extended data 7. MLF2 in complex with HSP70 and DNAJB6 preserves FG-rich condensate integrity over time.

a, Phase contrast images of 10 μM ScNup116 condensates formed in the presence of 2.5 μM DNAJB6b. Images were taken immediately after condensate formation (T = 0) or after three hours of incubation at 30ºC (T = 3) in the presence of ATP. Note the buffer condition is also shown in Fig. 6e. b, Phase contrast images of 10 μM TtMacNup98A condensates formed in the presence of 2.5 μM DNAJB6b, 5 μM HSPA1A, or 5 μM MLF2:HSP70. Images were taken at the timepoints described in panel (a). c, Images of 10 μM TtMacNup98A condensates formed in the presence of 5 μM HSPA1A plus 2.5 μM of the indicated DNAJB6b construct or 5 μM of the MLF2:HSP70 complex with 2.5 μM H31Q-DNAJB6b. Images were taken at the timepoints described in panel (a). Note the buffer condition is also shown in Fig. 6g. d, The turbidity of 10 μM ScNup116 or HsNup98 solutions in the absence or presence of 5 μM HSPA1A or the MLF2:HSP70 complex. Upon addition of 2 M urea, the condensates fully reverse and the solution loses turbidity as assessed by monitoring absorbance at 550 nm. e, 10 μM of ScNup116, TtMacNup98A, HsNup98, or 5 μM HSPA1A was incubated with 5 μM Thioflavin T (ThT) for 24 hours at 30ºC. ThT fluorescence (excitation 440 nm, emission 480 nm) was monitored to detect amyloid formation. All reactions contained 2 mM ATP and an ATP regenerating system. ThT signals for all conditions were normalized to the ScNup116 maximum value. f, 10 μM of ScNup116 was monitored for amyloid formation as described above in buffer containing 5 μM HSPA1A, 2.5 μM DNAJB6b, or 5 μM of the MLF2:HSP70 complex. Where indicated, 2 mM ATP was included or omitted. g, ScNup116 amyloid formation was observed under conditions with 5 μM HSP70 or the MLF2:HSP70 complex plus 2.5 μM DNAJB6b. Where indicated, 2 mM ATP was included or omitted. ThT conditions were as described for panel (e). Scale bar 5 μM for all panels. Source numerical data are available in source data.

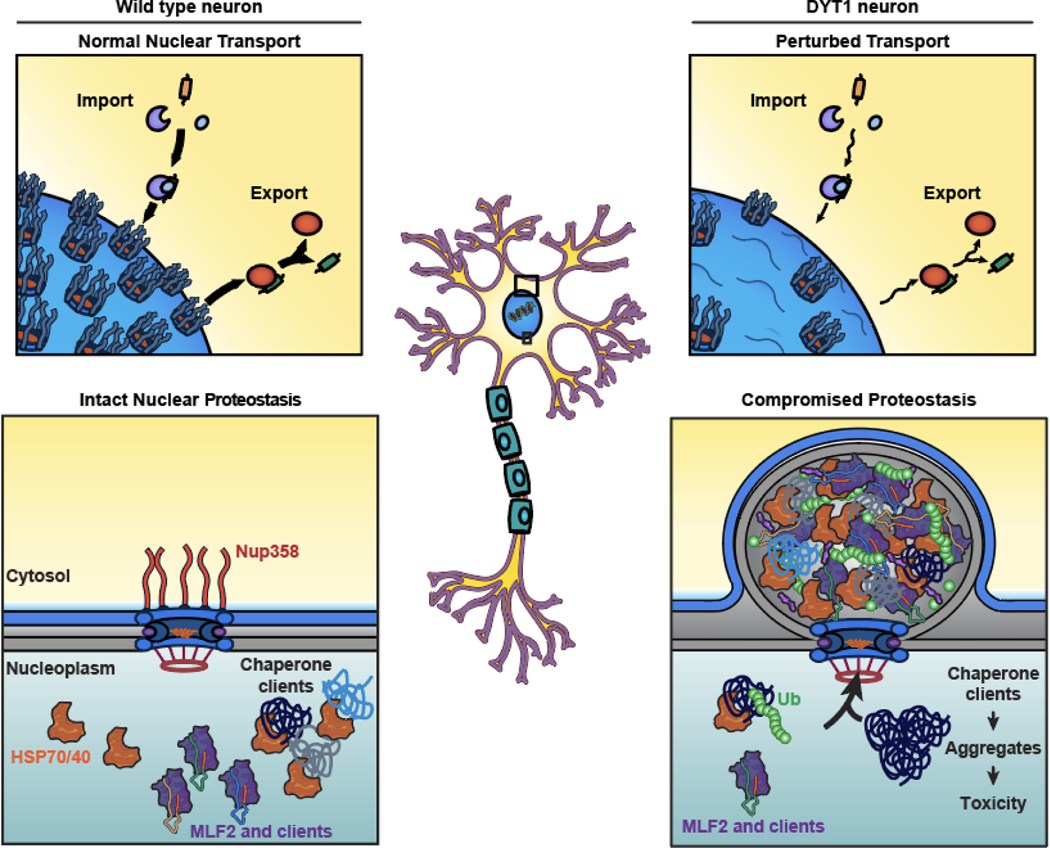

Extended data 8. A dual proteotoxicity mechanism contributes to DYT1 Dystonia onset.

Schematic model for how proteotoxicity may accumulate in Torsin-deficient cells. In wild type neurons, NPC biogenesis is unperturbed and chaperones are free to interact with clients. In DYT1 dystonia neurons, nuclear transport is perturbed due to defective NPC biogenesis. As FG-Nup containing blebs form instead of mature NPCs, they sequester proteins normally destined for degradation, chaperones, and MLF2. When essential chaperones are sequestered away from clients in Torsin-deficient cells, proteotoxic species may be allowed to form and persist to a greater extent than in cells with normal chaperone availability, sensitizing cellular proteostasis towards additional insults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH R01GM114401 (CS), DOD PR200788 (CS), NIH 5T32GM007223-44 (SMP), NIH F31NS120528 (SMP), NIH R56MH122449 (AJK), NIH R01MH115939 (AJK), NIH NS105640 (AJK), NIH F31MH116571 (JEG) and the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation (CS and AJR). The mass spectrometers and accompanying biotechnology tools at the Keck MS & Proteomics Resource at Yale University were funded in part by the Yale School of Medicine and by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (S10OD02365101A1, S10OD019967, and S10OD018034). We thank Dirk Görlich and members of his laboratory for sharing reagents. We thank the Yale Keck Biophysical Resource Center, Morven Graham, and the Yale Center for Cellular and Molecular Imaging. We also thank the MS & Proteomics Resource at Yale University for providing the necessary mass spectrometers and the accompany biotechnology tools funded in part by the Yale School of Medicine and by the Office of The Director, National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Khan YA, White KI, and Brunger AT, The AAA+ superfamily: a review of the structural and mechanistic principles of these molecular machines. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 2021: p. 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose AE, Brown RS, and Schlieker C, Torsins: not your typical AAA+ ATPases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 2015. 50(6): p. 532–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodchild RE, Kim CE, and Dauer WT, Loss of the dystonia-associated protein torsinA selectively disrupts the neuronal nuclear envelope. Neuron, 2005. 48(6): p. 923–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao C, et al. , Regulation of Torsin ATPases by LAP1 and LULL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(17): p. E1545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demircioglu FE, et al. , Structures of TorsinA and its disease-mutant complexed with an activator reveal the molecular basis for primary dystonia. Elife, 2016. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RS, et al. , The mechanism of Torsin ATPase activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(45): p. E4822–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozelius LJ, et al. , The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat Genet, 1997. 17(1): p. 40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fichtman B, et al. , Combined loss of LAP1B and LAP1C results in an early onset multisystemic nuclear envelopathy. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rampello AJ, Prophet SM, and Schlieker C, The Role of Torsin AAA+ Proteins in Preserving Nuclear Envelope Integrity and Safeguarding Against Disease. Biomolecules, 2020. 10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin JY and Worman HJ, Molecular Pathology of Laminopathies. Annu Rev Pathol, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Alegre P, Advances in molecular and cell biology of dystonia: Focus on torsinA. Neurobiol Dis, 2019. 127: p. 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.VanGompel MJ, et al. , A novel function for the Caenorhabditis elegans torsin OOC-5 in nucleoporin localization and nuclear import. Mol Biol Cell, 2015. 26(9): p. 1752–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jokhi V, et al. , Torsin mediates primary envelopment of large ribonucleoprotein granules at the nuclear envelope. Cell Rep, 2013. 3(4): p. 988–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim CE, et al. , A molecular mechanism underlying the neural-specific defect in torsinA mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(21): p. 9861–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang CC, et al. , TorsinA hypofunction causes abnormal twisting movements and sensorimotor circuit neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest, 2014. 124(7): p. 3080–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanabe LM, Liang CC, and Dauer WT, Neuronal Nuclear Membrane Budding Occurs during a Developmental Window Modulated by Torsin Paralogs. Cell Rep, 2016. 16(12): p. 3322–3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naismith TV, et al. , TorsinA in the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(20): p. 7612–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laudermilch E, et al. , Dissecting Torsin/cofactor function at the nuclear envelope: a genetic study. Mol Biol Cell, 2016. 27(25): p. 3964–3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacquemyn J, et al. , Torsin and NEP1R1-CTDNEP1 phosphatase affect interphase nuclear pore complex insertion by lipid-dependent and lipid-independent mechanisms. EMBO J, 2021. 40(17): p. e106914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pappas SS, et al. , TorsinA dysfunction causes persistent neuronal nuclear pore defects. Hum Mol Genet, 2018. 27(3): p. 407–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding B, et al. , Disease Modeling with Human Neurons Reveals LMNB1 Dysregulation Underlying DYT1 Dystonia. J Neurosci, 2021. 41(9): p. 2024–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rampello AJ, et al. , Torsin ATPase deficiency leads to defects in nuclear pore biogenesis and sequestration of MLF2. The Journal of Cell Biology, 2020. 219(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]