Abstract

In a study of 17,000 Medicare beneficiaries with mild cognitive impairment or dementia, non-Hispanic white older adults were more likely than Asian, Black or Hispanic older adults to have elevated cortical amyloid, as measured by PET. The findings have important implications for the use of amyloid-targeting therapies.

Racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer disease and related dementia (ADRD) have been consistently documented, with Black and Hispanic older adults having greater rates of clinically defined dementia than non-Hispanic white older adults. One of the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, is the aggregation of amyloid-β (amyloid)-containing extracellular plaques in the brain. Amyloid accumulation is believed by many to precede the spreading of tau-containing intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), the second hallmark of AD. Although the prevalence of clinically defined ADRD is consistently higher among Black and Hispanic older adults than white older adults1, whether the prevalence of pathologically defined AD (defined by the presence of amyloid plaques and tau NFTs) differs across racial and ethnic groups remains unknown. This question has come under renewed focus in light of the recent and likely forthcoming FDA accelerated approvals of disease modifying therapies that remove amyloid from the brains of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD. Understanding the prevalence of elevated brain amyloid levels suggestive of AD neuropathological changes (i.e., amyloid positivity) in diverse clinical samples with cognitive impairment will provide some understanding of the potential effectiveness of anti-amyloid therapies for treating AD across distinct racial and ethnic groups.

Using a large clinical sample of participants with MCI and dementia, Wilkins and colleagues2 recently published evidence that non-Hispanic white older adults are more likely than Asian, Black or Hispanic older adults to have elevated cortical Aβ, as measured by PET neuroimaging. This analysis used data from the Imaging Dementia-Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS)3 study, which was designed to determine whether receiving amyloid PET scans lead to changes in patient management and patient outcomes in over 20,000 Medicare beneficiaries age 65 or older with MCI or dementia. Wilkins and colleagues2 used two approaches to compare amyloid PET positivity between racial and ethnic groups. First, they used a 1:1 matching approach that matched participants on the basis of factors that may influence amyloid-positive status, including age, sex, education, the presence of cardiometabolic conditions, dementia family history, and level of cognitive impairment. This approach optimized the comparability of the samples across racial and ethnic groups, but used only 18% of the available sample. Thus, the researchers used all available data in a follow-up analysis that examined the likelihood of amyloid PET positivity across the different racial and ethnic groups after adjusting for the same social, demographic and clinical factors that were used in the 1:1 matching approach.

In the matched analysis the researchers found that the proportion of non-Hispanic white older adults with a positive amyloid PET scan was increased when compared with Asian and Hispanic, but not Black, older adults. However, when the researchers examined the relationship between race and ethnicity and Aβ positivity using the full sample, Asian (odds ratio (OR), 0.47), Hispanic (OR, 0.68), and Black (OR, 0.71) participants all had significantly lower odds of amyloid positivity than white participants, after adjusting for demographic, social, and clinical variables. Notably, greater age, female sex, and higher educational attainment were each associated with greater odds of amyloid positivity in this analysis.

Previous studies examining racial and ethnic differences in cortical amyloid using PET neuroimaging have yielded mixed results. For example, one community-based study of cognitively healthy participants and participants with MCI identified a greater likelihood of amyloid positivity in Black participants than in white participants4, whereas another community-based study of cognitively healthy participants found no differences in amyloid levels between Black and white participants5. However, in a study that used screening data from the Anti-Amyloid in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) clinical trial, non-Hispanic Black participants had lower rates of amyloid positivity than non-Hispanic white participants6. The conflicting findings from different studies might result in part from differences in study design and strategies for participant recruitment. Particularly for Asian, Black or Hispanic participants, who tend to interface less with the healthcare system, the differences between participants enrolled into a community-based study and participants selected from a clinical sample can be stark. Although Asian, Black and Hispanic participants were underrepresented in the study by Wilkens and colleagues2 — they comprised approximately 10% of the 17,000 participants — the study is one of the largest to date to examine amyloid PET imaging in individuals with cognitive impairment from minoritized racial and ethnic groups.

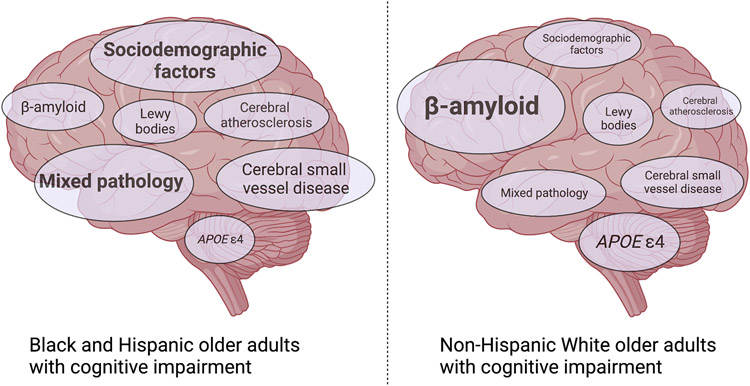

Although the presence of cortical amyloid plaques represents a core feature of AD, the findings from Wilkens and colleagues2 suggest that the aetiology of cognitive impairment for Asian, Black or Hispanic older adults who present with cognitive impairment is different in many instances from that of cognitively impaired non-Hispanic white older adults. These findings are consistent with a landmark autopsy study that identified a greater likelihood of isolated AD pathology in white older adults who met clinical criteria for AD dementia than in Black older adults who met the same clinical criteria; Black older adults were more likely to have cerebrovascular and mixed pathology7. For Asian, Black or Hispanic older adults amyloid might, therefore, have a smaller role in determining cognitive impairment than other factors such as co-occurring chronic medical conditions (for example, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes) and sociodemographic and systemic factors, each of which has been found to contribute to the racial and ethnic disparities in dementia diagnoses5,8 (Fig. 1). For instance, factors such as access to healthcare, quality of education, housing, and neighborhood characteristics are consistently shown to be associated with dementia risk in minoritized racial and ethnic groups8,9. Although some of these risk factors have been associated with brain amyloid levels10, many of the variables that account for a disproportionate share of dementia risk in Black and Hispanic older adults likely affect brain health through non-amyloidogenic or non-Alzheimer pathways.

Figure 1 ∣. The relative contribution of sociodemographic, clinical, and biological factors to cognitive impairment across racial and ethnic groups.

The size of the text represents the estimated relative contribution of different sociodemographic, clinical, and biological factors to cognitive impairment in Black and Hispanic older adults (part a) and non-Hispanic white older adults (part b).

Importantly, the recent study by Wilkens and colleagues2 was not designed to estimate the prevalence of elevated cortical amyloid across racial and ethnic groups in the US population. Nevertheless, this study does provide some understanding of the extent to which amyloid might be a determinant of cognitive impairment in patients who present to the clinic; therefore, the findings have several noteworthy implications. First, the study suggests that compared with white individuals, Asian, Black and Hispanic individuals might benefit less from disease modifying therapies that target cortical amyloid, underscoring the need to examine non-amyloid treatment targets while continuing to focus on addressing the race disparities in dementia through policy or community intervention to improve cardiovascular and metabolic health. Second, these results illustrate the importance of ensuring representative recruitment to clinical trials to ensure that approved interventions are efficacious for individuals from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, for whom the burden of dementia is the greatest. Last, these findings highlight the importance of identifying novel (non-amyloid, non-tau) biomarkers of dementia risk and dementia aetiology in older adults from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. Large-scale genome-wide and proteome-wide association studies in diverse cohorts will be valuable in identifying novel blood and CSF biomarkers for dementia risk while also advancing our understanding of the underlying biology of dementia in those participants at greatest risk.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chen C & Zissimopoulos JM Racial and ethnic differences in trends in dementia prevalence and risk factors in the United States. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv 4, 510–520 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkins CH et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Amyloid PET Positivity in Individuals With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Secondary Analysis of the Imaging Dementia-Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) Cohort Study. JAMA Neurol. 10.1001/JAMANEUROL.2022.3157 (2022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinovici GD et al. Association of Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography with Subsequent Change in Clinical Management among Medicare Beneficiaries with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc 321, 1286–1294 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesman RF et al. The ARIC-PET amyloid imaging study: Brain amyloid differences by age, race, sex, and APOE. Neurology 87, 473–480 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meeker KL et al. Socioeconomic Status Mediates Racial Differences Seen Using the AT(N) Framework. Ann. Neurol 89, 254–265 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deters KD et al. Amyloid PET Imaging in Self-Identified Non-Hispanic Black Participants of the Anti-Amyloid in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) Study. Neurology 96, e1491–e1500 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes LL et al. Mixed pathology is more likely in black than white decedents with Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 85, 528–534 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleason CE et al. Association between enrollment factors and incident cognitive impairment in Blacks and Whites: Data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Center. Alzheimers. Dement 15, 1533–1545 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell WR et al. Association of Neighborhood-Level Disadvantage with Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology. JAMA Netw. Open 3, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottesman RF et al. Association between midlife vascular risk factors and estimated brain amyloid deposition. JAMA 317, 1443 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]