Abstract

Background

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed and treated psychiatric disorders in childhood. Typically, children and adolescents with ADHD find it difficult to pay attention and they are hyperactive and impulsive. Methylphenidate is the psychostimulant most often prescribed, but the evidence on benefits and harms is uncertain. This is an update of our comprehensive systematic review on benefits and harms published in 2015.

Objectives

To assess the beneficial and harmful effects of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with ADHD.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, three other databases and two trials registers up to March 2022. In addition, we checked reference lists and requested published and unpublished data from manufacturers of methylphenidate.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised clinical trials (RCTs) comparing methylphenidate versus placebo or no intervention in children and adolescents aged 18 years and younger with a diagnosis of ADHD. The search was not limited by publication year or language, but trial inclusion required that 75% or more of participants had a normal intellectual quotient (IQ > 70). We assessed two primary outcomes, ADHD symptoms and serious adverse events, and three secondary outcomes, adverse events considered non‐serious, general behaviour, and quality of life.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently conducted data extraction and risk of bias assessment for each trial. Six review authors including two review authors from the original publication participated in the update in 2022. We used standard Cochrane methodological procedures. Data from parallel‐group trials and first‐period data from cross‐over trials formed the basis of our primary analyses. We undertook separate analyses using end‐of‐last period data from cross‐over trials. We used Trial Sequential Analyses (TSA) to control for type I (5%) and type II (20%) errors, and we assessed and downgraded evidence according to the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 212 trials (16,302 participants randomised); 55 parallel‐group trials (8104 participants randomised), and 156 cross‐over trials (8033 participants randomised) as well as one trial with a parallel phase (114 participants randomised) and a cross‐over phase (165 participants randomised). The mean age of participants was 9.8 years ranging from 3 to 18 years (two trials from 3 to 21 years). The male‐female ratio was 3:1. Most trials were carried out in high‐income countries, and 86/212 included trials (41%) were funded or partly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Methylphenidate treatment duration ranged from 1 to 425 days, with a mean duration of 28.8 days. Trials compared methylphenidate with placebo (200 trials) and with no intervention (12 trials). Only 165/212 trials included usable data on one or more outcomes from 14,271 participants.

Of the 212 trials, we assessed 191 at high risk of bias and 21 at low risk of bias. If, however, deblinding of methylphenidate due to typical adverse events is considered, then all 212 trials were at high risk of bias.

Primary outcomes: methylphenidate versus placebo or no intervention may improve teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.88 to −0.61; I² = 38%; 21 trials; 1728 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). This corresponds to a mean difference (MD) of −10.58 (95% CI −12.58 to −8.72) on the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD‐RS; range 0 to 72 points). The minimal clinically relevant difference is considered to be a change of 6.6 points on the ADHD‐RS. Methylphenidate may not affect serious adverse events (risk ratio (RR) 0.80, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.67; I² = 0%; 26 trials, 3673 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The TSA‐adjusted intervention effect was RR 0.91 (CI 0.31 to 2.68).

Secondary outcomes: methylphenidate may cause more adverse events considered non‐serious versus placebo or no intervention (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.37; I² = 72%; 35 trials 5342 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The TSA‐adjusted intervention effect was RR 1.22 (CI 1.08 to 1.43). Methylphenidate may improve teacher‐rated general behaviour versus placebo (SMD −0.62, 95% CI −0.91 to −0.33; I² = 68%; 7 trials 792 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), but may not affect quality of life (SMD 0.40, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.83; I² = 81%; 4 trials, 608 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

The majority of our conclusions from the 2015 version of this review still apply. Our updated meta‐analyses suggest that methylphenidate versus placebo or no‐intervention may improve teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms and general behaviour in children and adolescents with ADHD. There may be no effects on serious adverse events and quality of life. Methylphenidate may be associated with an increased risk of adverse events considered non‐serious, such as sleep problems and decreased appetite. However, the certainty of the evidence for all outcomes is very low and therefore the true magnitude of effects remain unclear.

Due to the frequency of non‐serious adverse events associated with methylphenidate, the blinding of participants and outcome assessors is particularly challenging. To accommodate this challenge, an active placebo should be sought and utilised. It may be difficult to find such a drug, but identifying a substance that could mimic the easily recognised adverse effects of methylphenidate would avert the unblinding that detrimentally affects current randomised trials.

Future systematic reviews should investigate the subgroups of patients with ADHD that may benefit most and least from methylphenidate. This could be done with individual participant data to investigate predictors and modifiers like age, comorbidity, and ADHD subtypes.

Plain language summary

Is methylphenidate an effective treatment for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and does it cause unwanted effects?

Key messages

‐ Methylphenidate might reduce hyperactivity and impulsivity and might help children to concentrate. Methylphenidate might also help to improve general behaviour, but does not seem to affect quality of life.

‐ Methylphenidate does not seem to increase the risk of serious (life‐threatening) unwanted effects when used for periods of up to six months. However, it is associated with an increased risk of non‐serious unwanted effects like sleeping problems and decreased appetite.

‐ Future studies should focus more on reporting unwanted effects and should take place over longer periods of time.

What is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)?

ADHD is one of the most commonly diagnosed and treated childhood psychiatric disorders. Children with ADHD find it hard to concentrate. They are often hyperactive (fidgety, unable to sit still for long periods) and impulsive (doing things without stopping to think). ADHD can make it difficult for children to do well at school, because they find it hard to follow instructions and to concentrate. Their behavioural problems can interfere with their ability to get on well with family and friends, and they often get into more trouble than other children.

How is ADHD treated?

Methylphenidate (for example, Ritalin) is the medication most often prescribed to children and adolescents with ADHD. Methylphenidate is a stimulant that helps to increase activity in parts of the brain, such as those involved with concentration. Methylphenidate can be taken as a tablet or given as a skin patch. It can be formulated to have an immediate effect, or be delivered slowly, over a period of hours. Methylphenidate may cause unwanted effects, such as headaches, stomachaches and problems sleeping. It sometimes causes serious unwanted effects like heart problems, hallucinations, or facial 'tics' (twitches).

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out if methylphenidate improves children's ADHD symptoms (attention, hyperactivity) based mainly on teachers' ratings using various scales, and whether it causes serious unwanted effects, like death, hospitalisation, or disability. We were also interested in less serious unwanted effects like sleep problems and loss of appetite, and its effects on children's general behaviour and quality of life.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that investigated the use of methylphenidate in children and adolescents with ADHD. Participants in the studies had to be aged 18 years or younger and have a diagnosis of ADHD. They could have other disorders or illnesses and be taking other medication or undergoing behavioural treatments. They had to have a normal IQ (intelligence quotient). Studies could compare methylphenidate with placebo (something designed to look and taste the same as methylphenidate but with no active ingredient) or no treatment. Participants had to be randomly chosen to receive methylphenidate or not. We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 212 studies with 16,302 children or adolescents with ADHD. Most of the trials compared methylphenidate with placebo. Most studies were small with around 70 children, with an average age of 10 years (ages ranged from 3 to 18 years). Most studies were short, lasting an average of around a month; the shortest study lasted just one day and the longest 425 days. Most studies were in the USA.

Based on teachers' ratings, compared with placebo or no treatment, methylphenidate:

‐ may improve ADHD symptoms (21 studies, 1728 children)

‐ may make no difference to serious unwanted effects (26 studies, 3673 participants)

‐ may cause more non‐serious unwanted effects (35 studies, 5342 participants)

‐ may improve general behaviour (7 trials 792 participants)

‐ may not affect quality of life (4 trials, 608 participants)

Limitations of the evidence

Our confidence in the results of the review is limited for several reasons. It was often possible for people in the studies to know which treatment the children were taking, which could influence the results. The reporting of the results was not complete in many studies and for some outcomes the results varied across studies. Studies were small and they used different scales for measuring symptoms. And most of the studies only lasted for a short period of time, making it impossible to assess the long‐term effects of methylphenidate. Around 41% of studies were funded or partly funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

How up to date is this evidence?

This is an update of a review conducted in 2015. The evidence is current to March 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Methylphenidate compared with placebo or no intervention for children and adolescents with ADHD.

| Methylphenidate compared with placebo or no intervention for ADHD | ||||||

| Patient or population: children and adolescents (up to and including 18 years of age) with ADHD Settings: outpatient clinic, inpatient hospital ward and summer school Intervention: methylphenidate Comparison: placebo or no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or no intervention | Methylphenidate | |||||

|

ADHD symptoms: all parallel‐group trials and first‐period cross‐over trials

ADHD Rating Scale (teacher‐rated) Average trial duration: 68.7 days |

Mean ADHD symptom score in the intervention groups corresponds to a mean difference of −10.58 (95% CI −12.58 to −8.72) on ADHD Rating Scale |

SMD −0.74 (−0.88 to −0.61) |

1728 (21 trials) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | The analysis was conducted on a standardised scale with data from studies that used different teacher‐rated scales of symptoms (Conners' Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS), Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behaviour (SWAN) Scale, The Swanson, Nolan and Pelham (SNAP) Scale ‐ Teacher, Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Hyperkinetische Störungen (FBB‐HKS)). We translated the effect size on to the ADHD Rating Scale from the SMD. | |

| Proportion of participants with one or more serious adverse events | Trial population | RR 0.80 (0.39 to 1.67) | 3673 (26 trials) |

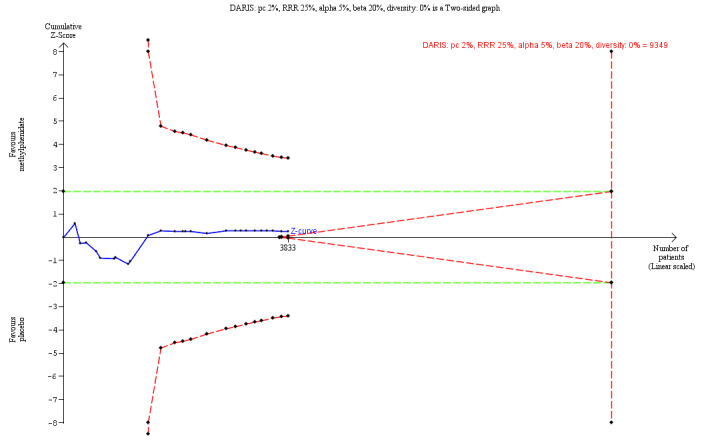

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowa,c | TSA RIS = 9349 TSA showed a RR of 0.91 (TSA‐adjusted Cl 0.31 to 2.68) |

|

| 8 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (5 less to 5 more) | |||||

| Proportion of participants with one or more adverse events considered non‐serious | Trial population |

RR 1.23 (1.11 to 1.37) |

5342 (35 trials) |

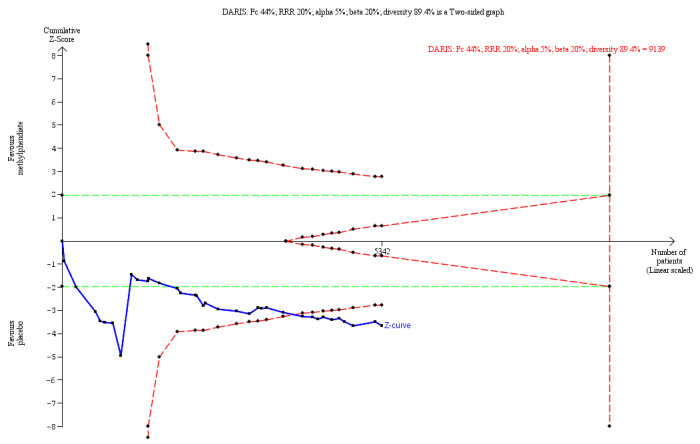

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowa,b | TSA RIS = 9139 TSA showed a RR of 1.22 (TSA‐adjusted Cl 1.08 to 1.43) | |

| 437 per 1000 | 538 per 1000 (348 less to 162 more) | |||||

| General behaviour: all parallel‐group trials and first‐period cross‐over trials General behaviour rating scales (teacher‐rated) | Mean general behaviour score in the intervention groups was 0.62 standard mean deviations lower (95% CI 0.91 lower to 0.33 lower) |

SMD −0.62 (−0.91 to −0.33) |

792 (7 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,d | ||

|

Quality of life (parent‐rated) |

Mean quality‐of‐life score in the intervention groups corresponds to a mean difference of 4.94 (95% CI −0.37 to 10.25) on the Child Health Questionnaire |

SMD 0.40 (−0.03 to 0.83) |

608 (4 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowa,b,c,e | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CI: confidence interval; RIS: required information size; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; TSA: Trial Sequential Analysis | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to high risk of bias (systematic errors causing overestimation of benefits and underestimation of harms) in several risk of bias domains, including lack of sufficient blinding and selective outcome reporting (many of the included trials did not report on this outcome). bDowngraded one level due to inconsistency: moderate statistical heterogeneity. cDowngraded two levels due to imprecision: wide confidence intervals and/or the accrued number of participants was below 50% of the diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) in Trial Sequential Analysis. dDowngraded one level due to indirectness: children's general behaviour was assessed by different types of rating scales with different focus on behaviour. e Downgraded one level due to indirectness: children's quality of life was assessed by their parents.

Background

Description of the condition

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed and treated developmental psychiatric disorders (Scahill 2000). It is acknowledged to be a complex heterogenous neurodevelopmental condition with no known cure (Buitelaar 2022). Many clinicians and academics see pharmacological treatments as being effective and safe but there is “considerable individual variability” of treatment response, dose needed, and tolerability (Buitelaar 2022).

The prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents is estimated to be 3% to 5% (Polanczyk 2007), depending on the classification system used, with boys two to four times more likely to be diagnosed than girls (Schmidt 2009). Individuals with ADHD exhibit difficulties with attentional and cognitive functions including problem‐solving, planning, maintaining flexibility and orientation, sustaining attention, inhibiting responses, and sustaining working memory (Pasini 2007; Sergeant 2003). They also experience difficulties in managing affects, for example, motivational delay and mood dysregulation (Castellanos 2006; Nigg 2005; Schmidt 2009). The diagnosis of ADHD has become more aligned between the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5; APA 2013), and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 11th Edition (ICD‐11; WHO 2019). The ICD‐11 was adopted in 2019, and came into effect in January 2022.

Both the DSM‐5 and the ICD‐11 base diagnoses on several inattentive and hyperactive‐impulsive symptoms being present before the age of 12 years, and causing impairment of functioning in several settings. There are also 'predominantly inattentive', 'predominantly hyperactive/impulsive' and 'combined' presentations in both systems (APA 2013; WHO 2019).

ADHD is increasingly recognised as a psychiatric disorder that extends into adulthood and occurs with high heterogeneity and comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders (Schmidt 2009). The Multimodal Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA) trial identified one or more co‐occurring conditions in almost 40% of participants (MTA 1999a). These included oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, depression, anxiety, tics, learning difficulties and cognitive deficits (Jensen 2001; Kadesjö 2001). Some argue that ADHD should be “considered not only a neurodevelopmental disorder, but also a persistent and complex condition, with detrimental consequences for quality of life in adulthood” (Di Lorenzo 2021, p. 283).

Rising rates of ADHD diagnoses, possible harm to children resulting from drug treatment (Zito 2000), and variation in prevalence estimates are matters of increasing concern (Moffit 2007; Polanczyk 2014). The need for a validated diagnostic test to confirm the clinical diagnosis of ADHD has given rise to a debate about its validity as a diagnosis (Timimi 2004). Professional and national bodies have developed guidelines on assessment, diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in an attempt to ensure that high standards are maintained in diagnostic and therapeutic practice (American Academy of Pediatrics 2011; CADDRA 2011; NICE 2018; Pliszka 2007a; SIGN 2009). Psychosocial interventions, such as parent management training, are recommended in the first instance for younger children and for those with mild to moderate symptoms (American Academy of Pediatrics 2011; NICE 2018; Pliszka 2007a), whereas stimulants (given alone or in combination with psychosocial interventions) are recommended for children with more severe ADHD (American Academy of Pediatrics 2011; CADDRA 2011; NICE 2018).

Description of the intervention

Methylphenidate, lisdexamphetamine/dexamphetamine, atomoxetine (a non‐stimulant selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor) and guanfacine (an alpha‐2 agonist) are recommended medical treatments for children, aged five years and above, and adolescents with ADHD, when psychoeducation and environmental modification have been implemented and reviewed, according to the NICE guidelines 2018 (NICE 2018). Furthermore, research suggests that the combination of behaviour therapy (e.g. behavioural parent training, school consultation, direct contingency management) and pharmacotherapy might benefit children with ADHD (Gilmore 2001; MTA 1999a).

Globally, methylphenidate has been used for longer than 50 years for the treatment of children with ADHD (Kadesjö 2002; NICE 2018). It has been part of driving innovation in controlled‐release technologies and new formulations. However, it has also contributed to concerns of pharmaceutical cognitive enhancement as well as created debate on pharmaceutical sales techniques in medicine, driven by high and possibly still increasing prescription rates (Wenthur 2016). In Europe, around 3% to 5% of children and adolescents have a prescription for methylphenidate (Bachmann 2017; Hodgkins 2013; Schubert 2010; Trecenõ 2012; Zoëga 2011) and in the USA approximately 8% of children and adolescents under 15 years of age have a prescription of methylphenidate (Akinbami 2011). However, USA statistics reported a trend of reduction in 2019 (Drug Usage Statistics 2013‐2019).

Pharmacological treatment with methylphenidate of children and adolescents with ADHD is reported to have a beneficial effect of reducing the major symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention. It is licensed for the treatment of children aged six years and older with ADHD (Kanjwal 2012), but is recommended by the NICE guideline as off‐label use from the age of five years (NICE 2018). Before starting medication for ADHD, a baseline assessment is necessary; the ADHD criteria must be reviewed, mental health and social circumstances considered and a review of physical health including a cardiovascular assessment with cardiological history, heart rate, and blood pressure should be conducted. If positive cardiovascular history or a co‐existing condition is being treated with a medicine that may pose an increased cardiac risk, electrocardiogram (ECG) is recommended (NICE 2018). Individual parent‐training programmes for parents and carers of children and young people with ADHD and symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder must likewise be considered (NICE 2018).

Different releases (immediate, sustained, or extended‐release) and formulations (oral or transdermal) of methylphenidate are available and it is important to individualise the treatment to optimise effect and minimise adverse events (Childress 2019). Response of treatment is individual and intervention dose can vary significantly between children with some responding to relatively low dosages while others require larger doses to achieve the same effect (Stevenson 1989). Therefore, it is important that the dose of methylphenidate is titrated to an optimal level that maximises therapeutic benefits while producing minimal adverse events. Immediate‐release formulations of methylphenidate are usually initiated at 5 mg once or twice daily then titrated weekly by 5 mg to 10 mg daily, divided into two or three doses until effects are noted and adverse effects are tolerable. The dose can range from 5 mg to 60 mg methylphenidate, 1.4 mg/kg daily administered in two to three doses (BNF 2020; Pliszka 2007a). Under specialist supervision, the dose may be increased to 2.1 mg/kg daily in two to three doses (maximum 90 mg daily). Modified‐release formulations are initiated with 18 mg once daily and increased up to a maximum of 54 mg.

Immediate‐release methylphenidate has a bioavailability of 11% to 53% and an approximate duration of two to four hours with a peak blood concentration after two hours and a half‐life of two hours. Sustained‐release and extended‐release formulations of methylphenidate have a duration of action of three to eight hours and eight to 12 hours, respectively (Kimko 1999; NICE 2018).

Studies have indicated impairments in children's height and weight during treatment with methylphenidate (Schachar 1997a; Swanson 2004b; Swanson 2009). McCarthy and colleagues' study using the ‘German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents’ (KiGGS) database found that methylphenidate use in boys with ADHD was associated with low body mass index (BMI) but were “unable to confirm that methylphenidate use is also associated with low height (≤3rd percentile) and changes in blood pressure” (McCarthy 2018).

Monitoring of height, weight, heart rate, blood pressure, and adverse events, as well as encouraging adherence for effective treatment, are suggested. Medication‐free periods are recommended to reassess the treatment efficacy on ADHD symptoms (Kidd 2000; NICE 2018). Adverse effects of methylphenidate are common and dose‐dependent (Rossi 2010; Storebø 2018b). In a large Cochrane Review of observational studies, more than half (51.3%) of participants being treated with methylphenidate experienced one or more adverse events considered non‐serious such as headache, sleep difficulties, abdominal pain, decreased appetite, anxiety, and sadness (Storebø 2018b). Furthermore, 16% discontinued methylphenidate due to ‘unknown’ reasons and another 6% due to adverse events considered non‐serious (Storebø 2018b).

Serious adverse events such as psychosis, mood disorders (Block 1998; Cherland 1999; MTA 1999a), serious cardiovascular events, and sudden unexplained death have also been reported (Cooper 2011; Habel 2011), but methylphenidate does not seem to increase serious adverse events in randomised clinical trials (Storebø 2015a). It must however be taken into consideration that this meta‐analysis was considerably underpowered and not able to draw firm conclusions (Storebø 2015a).

As a stimulant, methylphenidate carries the risk of addiction, and the nonmedical use has been reported to vary from 5% to 35% (Clemow 2014), with a peak risk at ages estimated to be between 16 and 19 years, and a new user rate of 0.7% to 0.8% per year (Austic 2015). Conversely, methylphenidate has been correlated with the reduction of harmful outcomes such as reducing emergency department visits (Dalsgaard 2015), reducing criminality (Lichtenstein 2012), reducing transport accidents (Chang 2017), and having a protective effect on abuse of other substances (Chang 2014).

How the intervention might work

The pharmacodynamics of methylphenidate have been extensively investigated in animal and human studies with brain imaging and chemistry studies, yet they remain uncertain. It is presumed that the effects of methylphenidate on ADHD symptoms are related to its effects on dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurotransmissions within the central nervous system (Engert 2008). Methylphenidate is assumed to act by inhibiting catecholamine reuptake, primarily as a dopamine‐norepinephrine re‐uptake inhibitor, modulating levels of dopamine and, to a lesser extent, levels of norepinephrine (Heal 2006; Iversen 2006).

Methylphenidate binds to and blocks dopamine and norepinephrine transporters (Heal 2006; Iversen 2006), and increased concentrations of dopamine and norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft lead to escalated neurotransmission. On average, methylphenidate elicits a 3 to 4 times increase in dopamine and norepinephrine in the striatum and prefrontal cortex (Hodgkins 2013), which is responsible for executive functions and produces effects such as increased alertness, reduced fatigue, and improved attention.

Methylphenidate is thought to activate self‐regulated control processes to ameliorate what are believed to be the core neurofunctional problems of ADHD (Barkley 1977a; Schulz 2012; Solanto 1998). Evidence suggests that symptom control is strongly related to functional improvement (Biederman 2003a; Cox 2004a; Swanson 2004a).

Studies indicate that methylphenidate is effective for treating both the core symptoms of ADHD (inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity) and aggression (Connor 2002), since children can manage their impulsivity better (Barkley 1981; Barkley 1989a; Shaw 2012). Barkley noted differences in response to methylphenidate between ADHD inattentive and combined subtypes: children with the inattentive subtype were judged to have a less favourable response to methylphenidate than those diagnosed with the combined presentation (Barkley 1991b). Some children and adolescents may become less responsive to methylphenidate treatment over time (Molina 2009). However, magnetic resonance imaging studies suggest that long‐term treatment with ADHD stimulants may decrease abnormalities in the brain structure and function found in patients with ADHD (Frodl 2012; Spencer 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

During the past 20 years, several systematic reviews and narrative reviews have investigated the efficacy of methylphenidate for ADHD (with or without meta‐analysis). Fifteen reviews have pooled results on methylphenidate treatment for children and adolescents with ADHD (Bloch 2009; Charach 2011; Charach 2013; Faraone 2002; Faraone 2006; Faraone 2009; Faraone 2010; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; King 2006; Maia 2014; Punja 2013; Reichow 2013; Schachter 2001; Van der Oord 2008). However, none of these were conducted as Cochrane systematic reviews. Most of them did not adhere to the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022a), nor the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati 2009; Moher 2015). None of these reviews had a peer‐reviewed protocol published before the analyses were conducted. Thirteen did not undertake subgroup analyses examining the effects of comorbidity on treatment effects (Bloch 2009; Charach 2011; Charach 2013; Faraone 2002; Faraone 2006; Faraone 2009; Faraone 2010; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; Maia 2014; Punja 2013; Schachter 2001; Van der Oord 2008). Some did not control for treatment effects by ADHD subtype (Bloch 2009; Charach 2013; Faraone 2002; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; King 2006; Maia 2014; Punja 2013; Schachter 2001; Van der Oord 2008). Others did not consider effects according to the dose of methylphenidate (Charach 2011; Charach 2013; Faraone 2006; Faraone 2009; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; Maia 2014; Punja 2013; Reichow 2013; Van der Oord 2008). As for the outcomes, most meta‐analyses pooled data from parents, teachers and independent assessors (Bloch 2009; Charach 2011; Charach 2013; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; King 2006; Reichow 2013), and did not separate outcome measures for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (Bloch 2009; Charach 2013; Faraone 2002; Faraone 2006; Faraone 2009; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; Van der Oord 2008). Moreover, most previous reviews only investigated the effects of methylphenidate on symptoms of ADHD; review authors did not present data on spontaneous adverse events (Charach 2013; Faraone 2002; Faraone 2006; Faraone 2009; Faraone 2010; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; Maia 2014; Van der Oord 2008), nor on adverse events, as measured by rating scales (Bloch 2009; Charach 2013; Faraone 2002; Faraone 2006; Faraone 2009; Faraone 2010; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; King 2006; Maia 2014; Punja 2013; Reichow 2013; Schachter 2001; Van der Oord 2008), and they did not try to explain why such information was not provided. Finally, these reviews did not systematically assess the risk of random errors, risk of bias, or trial quality (Bloch 2009; Charach 2011; Charach 2013; Faraone 2002; Faraone 2006; Faraone 2009; Faraone 2010; Hanwella 2011; Kambeitz 2014; King 2006; Van der Oord 2008). These shortcomings plus other methodological limitations including potential bias in excluding non‐English language publications (Charach 2013; Faraone 2010; Punja 2013; Van der Oord 2008), and not searching the principal major international databases nor reporting search terms clearly (Bloch 2009; Faraone 2002; Kambeitz 2014; Reichow 2013), may have compromised data collection, consequently calling the results of these previous meta‐analyses into question.

The first version of this systematic review was published in 2015 (Storebø 2015a). In this version, we reported that methylphenidate may improve teacher‐reported ADHD symptoms, teacher‐reported general behaviour, and parent‐reported quality of life among children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD. We also underlined that the low quality of the evidence meant that we could not be certain of the magnitude of the effects. There was evidence that methylphenidate is associated with an increased risk of adverse events considered non‐serious, such as sleep problems and decreased appetite. We did not have evidence that methylphenidate increased the risk of serious adverse events, but this was unclear due to underreporting of serious adverse events (Storebø 2015a). We received many critical responses which were published as articles and letters to editors as well as blog comments. Six comments were received on the BMJ version of this review (Storebø 2015b). An editorial by Mina Fazel commenting on the article in the BMJ was also published alongside the review article (Fazel 2015). Mina Fazel recognised that our review was a comprehensive and rigorous Cochrane systematic review and meta‐analysis of the use of methylphenidate in young people with ADHD. She underlined the need for more research as she concluded: "The slow progress of ADHD research and limited evidence base for treatments are in stark contrast with the hallmarks of the disorder itself, with its high prevalence and broad symptomology" (Fazel 2015). A short version of the review was also published in JAMA in 2016 (Storebø 2016b), followed by a commenting editorial by Philip Shaw who concluded: "Sometimes in medicine, the best available data are imperfect. Such imperfections do not render the data unusable; rather, the limitations can be weighed by physicians and other health care professionals, and by families as they decide how best to help a child struggling with ADHD. Psychostimulants improve ADHD symptoms and quality of life. This meta‐analysis highlights the complexities in quantifying this benefit." (Shaw 2016 p. 1954). Philip Shaw wrote that in a meta‐analysis of methylphenidate for adults with ADHD (Epstein 2014), the trial biases were similar to those in our review and that the bias assessment seemed to be very subjective (Shaw 2016). The review by Epstein and colleagues (Epstein 2016), was withdrawn from the Cochrane Library on 26 May 2016 due to several methodological problems including erroneous risk of bias assessment (Boesen 2017; Storebø 2015b [pers comm]).

Several critical comments on our 2015 review from different authors were published in blog posts, articles and letters to editors (Hollis 2016; Banaschewski 2016a; Banaschewski 2016b; Hoekstra 2016; Romanos 2016). All these comments and our responses are listed with references in the 2015 published version of this review (Storebø 2015a). The critical points raised focused on our certainty assessment, including our use of the vested interest risk of bias domain, concerns that blinding may be affected by easily recognisable adverse events, concerns that we erroneously included too many non‐eligible trials (such as cross‐over trials and trials with add‐on treatment to methylphenidate), and that we had errors in the data extracted. We showed in several response articles and letters to editors that our trial selection was not flawed and that our data collection and interpretation of data in most aspects was systematic and sound (Storebø 2016a; Storebø 2016c; Storebø 2016d; Storebø 2016e; Storebø 2016f; Storebø 2018a). We answered all criticism, but in one case our response to a critical editorial (Gerlach 2017), in the Journal ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders was declined by the editor. In addition, we have argued that our assessment of quality and our conclusion were not misleading (Storebø 2016c; Storebø 2016d; Storebø 2016e; Storebø 2016f; Storebø 2018a). We agreed that minor errors were present in the review, yet we were still able to show that the effects were negligible and that these minor errors did not affect our conclusions (Storebø 2016c; Storebø 2016d; Storebø 2016e; Storebø 2016f; Storebø 2018a). We stated that the evidence for the use of methylphenidate in children and adolescents with ADHD was flawed (Storebø 2016c; Storebø 2016d; Storebø 2016e; Storebø 2016f; Storebø 2018a).

In 2018 an application for including methylphenidate on the 21st update of the WHO's List of Essential Medicines was rejected due to concerns regarding the quality of the evidence for benefits and harms (Storebø 2021). An extended research team made a comparable application in 2020 for the 22nd update of the list. The decision of the committee was — for the second time — not to include methylphenidate on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines due to low quality of evidence, lack of data after 12 weeks, and adverse effects of concern (Pereira Ribeiro 2022). The committee also stressed that "evidence of the effectiveness and safety of methylphenidate in the treatment of ADHD of at least 52 weeks duration, outcomes of the revision of the of the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) Guideline for Mental, Neurological and Substance use Disorders, and evaluation of health system capacity to provide appropriate diagnostic, non‐pharmacological and pharmacological treatment and monitoring in low‐resource settings would be informative for any future consideration for inclusion of methylphenidate on the Model Lists" (WHO 2021 p. 538).

We have published an overview article where we found 24 eligible systematic reviews and meta‐analyses published after the 2015 version of the current review (Ribeiro 2021). The results showed that the evidence was uncertain due to the low quality of evidence. There was also an underreporting of adverse events in randomised clinical trials. We concluded that there is uncertain evidence to support that methylphenidate is beneficial in treating children and adolescents with ADHD. (Ribeiro 2021).

In October 2021 the European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG) published an overview article summarising the current evidence and identified methodological issues and gaps in the current evidence (Coghill 2021). The authors of this article were mostly the same authors that had published the many critical comments to our 2015 version of this review. They wrote in this article: "We have summarized the current evidence and identified several methodological issues and gaps in the current evidence that we believe are important for clinicians to consider when evaluating the evidence and making treatment decisions. These include understanding potential impact of bias such as inadequate blinding and selection bias on study outcomes; the relative lack of high‐quality data comparing different treatments and assessing long‐term effectiveness, adverse effects and safety for both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological treatments; and the problems associated with observational studies, including those based on large national registries and comparing treatments with each other" (Coghill 2021).

Combined, this indicates a need to update this systematic review on the benefits and harms of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with ADHD and that this should continue to be done until more solid evidence for the recommendation about the use of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with ADHD can be established. Given the mounting concerns regarding the increasing use of methylphenidate in children younger than six years, it is vital that researchers explore the risks versus benefits of treatment in this younger population (US FDA 2011). Although stimulant medications may have a favourable risk‐benefit profile, they might carry potential risks of both serious and non‐serious adverse events.

To expand our understanding of adverse events, particularly where these are rare or take time to become apparent, we felt it necessary to bolster the limited data from randomised clinical trials (RCTs) by including data from non‐randomised studies (Storebø 2015a). Our Cochrane systematic review from 2018 focused on the harms of methylphenidate treatment in children and adolescents with ADHD (Storebø 2018b). This review included 260 non‐randomised studies: four patient‐controlled studies, seven comparative cohort studies, 177 cohort studies, two cross‐sectional studies, and 70 patient reports, including over 2.2 million participants. In contrast to our 2015 review based on RCTs (Storebø 2015a), methylphenidate compared to no intervention significantly increased the risk of serious adverse events in comparative studies (risk ratio (RR) 1.36, 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.17 to 1.58; 2 trials; 72,005 participants). Serious adverse events included psychotic disorders, arrhythmia, seizures, and hypertension. Approximately half (51.2%) of participants experienced one or more non‐serious adverse event (95% CI 41.2 to 61.1%; 49 trials; 13,978 participants). These were sleep difficulties (17.9%), decreased appetite (31.1%), and abdominal pain (10.7%). Furthermore, 16.2% (95% CI 13.0 to 19.9%; 57 trials, 8340 participants) discontinued methylphenidate because of 'unknown' reasons and 6.20% (95% CI 4.90 to 8.00%; 37 trials; 7142 participants) because of non‐serious adverse events. We assessed most included studies as having critical risk of bias. The GRADE quality rating of the certainty of evidence was very low. Some studies indicated that methylphenidate can decrease children's normal growth rate (Schachar 1997b; Swanson 2004a; Swanson 2009). Given the unclear evidence in this field and the need for better data, we, therefore, conducted the present update of this systematic review of the benefits and harms of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with ADHD in RCTs while adhering to the Cochrane guidance (Higgins 2022a), and to the PRISMA guidelines (Liberati 2009; Moher 2015).

Objectives

To assess the beneficial and harmful effects of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with ADHD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs of methylphenidate for the treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD. We included trials irrespective of language, publication year, publication type or publication status.

Types of participants

Children and adolescents aged 18 years and younger with a diagnosis of ADHD, according to the DSM‐III (APA 1980), DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 1994), and DSM‐5 (APA 2013), or with a diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorders according to the ICD‐9, ICD‐10 (WHO 1992), and ICD‐11 (WHO 2019) . We included participants with ADHD with or without comorbid conditions such as conduct or oppositional disorders, tics, depression, attachment disorders or anxiety disorders. Trials eligible for inclusion were those in which at least 75% of participants were aged 18 years or younger, and the mean age of the trial population was 18 years or younger. We also required that at least 75% of participants had a normal intellectual quotient (IQ > 70).

Types of interventions

Methylphenidate, administered at any dosage or in any formulation, versus placebo or no intervention.

We permitted co‐interventions if the experimental and control intervention groups received the co‐interventions similarly. In some trials that included co‐interventions in both groups, such as a behavioral intervention combined with methylphenidate versus a behavioral intervention, we considered these as methylphenidate versus no intervention. We did not permit polypharmacy as a co‐intervention in only one of the intervention groups.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

ADHD symptoms (attention, hyperactivity and impulsivity), measured over the short term (within six months) and over the long term (longer than six months) by psychometric instruments or by observations of behaviour, using, for example, Conners' Teacher Rating Scales (Conners 1998a; Conners 2008). Raters could be teachers, independent assessors, or parents. We chose to report the results of teacher‐rated outcomes as the primary outcome (see Results).

Number of serious adverse events. We defined a serious adverse event as any event that led to death, was life‐threatening, required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability, or as any important medical event that may have jeopardised the patient's life or that required intervention for prevention. We considered all other adverse events to be considered non‐serious (ICH 1996).

Secondary outcomes

Non‐serious adverse events. We assessed all adverse events, including, for example, growth retardation and cardiological, neurological and gastrointestinal events, as described in ICH (International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use) Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1) (ICH 1996).

General behaviour in school and at home, as rated by psychometric instruments such as the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991), measured over the short term (within six months) and over the long term (longer than six months). Raters could be teachers, independent assessors, or parents. We chose to report the results of teacher‐rated outcomes as primary outcomes (see Results).

Quality of life, as measured by psychometric instruments such as the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ; Landgraf 1998). Raters could be teachers, the children, independent assessors, or parents.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We ran the first literature searches in October 2011 and updated them in November 2012, March 2014, between 26 February and 10 March 2015 and most recently 11 January 2021 and 25 March 2022. We searched the following sources.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 1; part of the Cochrane Library, which includes the Specialised Register of the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group), searched 25 March 2022

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to current), searched 25 March 2022

Embase Ovid (1980 to current), searched 25 March 2022

CINAHL EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1980 to current), searched 25 March 2022

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to current), searched 25 March 2022

Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org/) searched 25 March 2022

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (CPCI‐S) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Science & Humanities (CPCI‐SS&H) (Web of Science; 1990 to 25 March 2022)

ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov ), searched 25 March 2022

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; who.int/ictrp/en), searched 25 March 2022

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD; ndltd.org), searched 29 November 2022)

DART Europe E‐Theses Portal (www.dart-europe.eu/basic-search.php), searched 28 November 2022)

Theses Canada (library-archives.canada.ca/eng/services/services-libraries/theses/Pages/theses-canada.aspx), searched 29 November 2022

Worldcat (worldcat.org), searched 28 November 2022

The search strategy for each database is shown in Appendix 1. We used a broad strategy to capture trials on efficacy and trials on adverse events. To overcome poor indexing and abstracting, we listed individual brand names within the search strategies. We did not limit searches by language, year of publication or type or status of the publication. We sought translation of relevant sections of non‐English language articles.

Searching other resources

To find additional relevant trials not identified by electronic searches, we checked the bibliographic references of identified review articles, meta‐analyses and a selection of included trials. Furthermore, we requested published and unpublished data from pharmaceutical companies manufacturing methylphenidate, including Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Medice (represented in Denmark by HB Pharma), Janssen‐Cilag, Novartis, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Ironshore Pharmaceuticals and Pfiizer (Appendix 2). We also requested data from unpublished trials from experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted this review according to the recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022a), and performed analyses using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5; Review Manager 2020).

Selection of studies

In this update of the Storebø 2015a review, seven review authors (OJS, HEC, JPS, JPR, MROS, PDR, CMLH) worked together in groups of two and independently screened titles and abstracts of all publications obtained from the literature searches. We obtained full‐text papers for any abstract/title that might match our inclusion criteria and assessed them against our listed inclusion criteria. We discussed disagreements, and if we were unable to reach agreement or consensus, we consulted a third review author (OJS).

Data extraction and management

In this update of the Storebø 2015a review, working together in groups of two, six review authors extracted data (MROS, CMLH, JPR, JPS, MS, OJS). We resolved disagreements by discussion and we used an arbiter if required. When data were incomplete, or when data provided in published trial reports were unclear, we contacted trial authors to ask for clarification of missing information. We contacted the authors of all cross‐over trials to obtain first‐period data on ADHD symptoms.

We developed data extraction forms a priori. After performing data extraction pilots, we updated these forms to accommodate the extraction of more detailed data and to facilitate standardised approaches to data extraction among review authors. All data extractors used these extraction forms (see Appendix 3; Appendix 4).

Six review authors (MS, HEC, JPR, JPS, MROS and OJS) entered data into RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2020).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included trial, data extractors (MROS, CMLH, JPR, JPS, MS, OJS) independently evaluated risk of bias domains (listed below), resolving disagreements by discussion. For each domain, we assigned each trial to one of the following three categories: low risk of bias, unclear (uncertain) risk of bias or high risk of bias, according to guidelines provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Given the risk of overestimation of beneficial intervention effects and underestimation of harmful intervention effects in RCTs with unclear or inadequate methodological quality (Kjaergard 2001; Lundh 2012; Lundh 2018; Moher 1998; Savović 2012a; Savović 2012b; Savovic 2018; Schulz 1995; Wood 2008), we assessed the influence of risk of bias on our results (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). Risk of bias components were as follows: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and other potential sources of bias. We defined low risk of bias trials as trials that had low risk of bias in all domains. We considered trials with one or more unclear or high risk of bias domains as trials with high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We defined the treatment effect as an improvement in ADHD symptoms, general behaviour and quality of life.

Dichotomous data

We summarised dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We calculated the risk difference (RD).

Continuous data

If all trials used the same measure of a given continuous outcome in a meta‐analysis, we calculated mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs. If trials used different measures, we calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs. If trials did not report means and standard deviations but did report other values (e.g. t‐tests, P values), we transformed these into standard deviations.

For primary analyses of teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms, teacher‐rated general behaviour and quality of life, we transformed SMDs into MDs on the following scales to assess whether results exceeded the minimal clinically relevant difference: ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD‐RS; DuPaul 1991a), Conners' Global Index (CGI; Conners 1998a), and Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ; Landgraf 1998). We transformed SMDs into MDs on the ADHD‐RS by using the SD 14.3 from Riggs 2011, on the CGI by using the SD 5.79 from Greenhill 2002, and on the CHQ by using the SD 12.35 from Newcorn 2008. We identified a minimal clinically relevant difference (MIREDIF) of 6.6 points on the ADHD‐RS, ranging from 0 to 72 points, based on a trial by Zhang 2005, and a MIREDIF of 7.0 points on the CHQ, ranging from 0 to 100 points, based on a trial by Rentz 2005. We could find no references describing a MIREDIF on the CGI (range 0 to 30 points).

Unit of analysis issues

Many ADHD trials use cross‐over methods. We aimed to obtain data from the first period of these trials and to pool these data with data from parallel‐group trials, as they are similar (Curtin 2002). We requested these data from trial authors if they were not available in the published report. When we were not able to obtain first‐period data from cross‐over trials, we established another group comprising only end‐of‐last‐period data. Our original intention was to adjust for the effect of the unit of analysis error in cross‐over trials by conducting a covariate analysis, but data were insufficient for this. As cross‐over trials are more prone to bias from carry‐over effects, period effects and unit of analysis errors (Curtin 2002), we conducted a subgroup analysis to compare these two groups. We tested for the possibility of a carry‐over effect and a period effect (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). We found similar treatment effects in the two groups and no significant subgroup differences. However, we noted considerable heterogeneity, and so we presented the results of the analyses separately (Effects of interventions). In a methods article, we investigated the risk of carry‐over effect and unit of analysis error due to period effects comparing parallel‐group trials, the first period of cross‐over trials and the end of the last period of cross‐over trials and found no signs of period effects or carry‐over effects in cross‐over trials assessing methylphenidate for children and adolescents with ADHD (Krogh 2019).

For dichotomous outcomes in cross‐over trials, we were unable to adjust the variance to account for the correlation coefficient as advised by Elbourne 2002 due to insufficient information or to estimate the RR using the marginal probabilities as recommended by Becker 1993. Consequently, we used end‐of‐last‐period data for estimating RRs. As these effect estimates are prone to potential bias, we performed a sensitivity analysis by removing these trials to assess the robustness of the pooled results.

We used endpoint data when these were reported or could be obtained from trial authors. However, when RCTs reported only 'change scores', we pooled these with scores from the end of intervention (da Costa 2013). We used only endpoint standard deviations in the trials with 'change scores'. We explored whether inclusion of change data affected the outcomes by performing a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis).

Dealing with missing data

We obtained missing data by contacting trial authors. When we were not able to obtain missing data, we conducted analyses using available (incomplete) data. Although some trials reported that they used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses, data were missing for many primary outcomes (Hollis 1999). We could not use 'best‐case scenario' and 'worst‐case scenario' analyses on our assessment of benefit as there were no dichotomous outcomes. Also, we decided not to use 'best‐case scenario' and 'worst‐case scenario' analyses in our assessment of adverse events because we evaluated these analyses to be imprecise due to the high number of trials not reporting adverse events, and due to the high number of dropouts in the trials reporting adverse events.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We identified three types of heterogeneity: clinical, methodological and statistical. Clinical heterogeneity reflects variability among participants, interventions and outcomes of trials; methodological heterogeneity reflects variability in the trial designs; and statistical heterogeneity reflects differences in effect estimates between trials. We assessed clinical heterogeneity by comparing differences in trial populations, interventions and outcomes, and we evaluated methodological heterogeneity by comparing the trial designs. We identified potential reasons for clinical and methodological heterogeneity by examining individual trial characteristics and subgroups. Furthermore, we observed statistical heterogeneity in trials both by visual inspection of a forest plot and by use of a standard Chi² test value with a significance level of α (alpha) = 0.1. We examined the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). We judged values between 0% and 40% to indicate little heterogeneity, between 30% and 60% to indicate moderate heterogeneity, between 50% and 90% to indicate substantial heterogeneity, and between 75% and 100% to indicate considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2022).

Assessment of reporting biases

We followed the recommendations for reporting bias, including publication bias and outcome reporting bias, provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Page 2022). We drew funnel plots (estimated differences in treatment effects against their standard error) and performed Egger's statistical test for small‐study effects; asymmetry could be due to publication bias or could indicate genuine heterogeneity between small and large trials (Page 2022). We did not visually inspect the funnel plot if fewer than 10 trials were included in the meta‐analysis, in accordance with the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Page 2022). We compared results extracted from published journal reports to results obtained from other sources (including correspondence) as a direct test for publication bias.

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2022). We synthesised data statistically when clinical heterogeneity was not excessive (e.g. variability in participant characteristics was minimal). Furthermore, we included and analysed trials undertaken in any configuration or setting (e.g. in groups, at home, or at a centre).

We used the inverse variance method, which gives greater weight to larger trials, to generate more precise estimates. For some adverse events we combined dichotomous and continuous data using the generic inverse variance method. We synthesised data using change‐from‐baseline scores or endpoint data. If data were available for several intervals, we used the longest period assessed. We used the fixed‐effect and random‐effects models in all meta‐analyses, however, we reported the results of the random‐effects model when we included more than one trial in the meta‐analysis. This approach gives greater weight to smaller trials. Statistical significance did not change when we applied a fixed‐effect model (Jakobsen 2014). We performed separate meta‐analyses for three types of raters (teachers, independent assessors, and parents) for data from parallel‐group trials combined with data from the first period of cross‐over trials and data from the end of the last period from cross‐over trials.

ADHD symptom scales describe the severity of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity at home and at school; high scores indicate severe ADHD. We judged that, in spite of the diversity of psychometric instruments, they could be used for our outcomes, and we integrated different types of scales into the analyses. We used MDs if all trials used the same measure and SMDs when different trials used different outcome measures for the same construct.

When separate measures of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention were available, we used combined scores. When symptoms were measured and reported at different time points during the day (after ingestion of medication or placebo), we used the time point closest to noon.

Three types of raters, teachers, independent assessors and parents measured two outcomes — ADHD symptoms and general behaviour. We considered these data as showing different outcomes. We presented the results of teacher‐rated measures as the primary outcome because symptoms of ADHD are more readily detectable in the school setting (Hartman 2007).

For children weighing 25 kg or less, the maximum recommended dose of methylphenidate is 30 mg/day compared to 60 mg/day for children weighing more than 25 kg. After careful consideration, we renamed the high‐dose group as 'moderate/high' dose because doses are not always 'high' in heavier children. When trials reported data for different doses, we used data for the dose that we defined as moderate/high (> 20 mg/day) in our primary analyses.

We summarised adverse event data as RRs with 95% CIs for dichotomous outcomes. For the purposes of this review, we used only dichotomous outcomes that reflected the number of participants affected by the event per the total number of participants.

Diversity‐adjusted required information size and Trial Sequential Analysis

Trial Sequential Analysis is a method that combines the required information size (RIS) for a meta‐analysis with the threshold for statistical significance to quantify the statistical reliability of data in a cumulative meta‐analysis, with P value thresholds controlled for sparse data and repetitive testing of accumulating data (Brok 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008; Wetterslev 2017).

Comparable to the a priori sample size estimation provided in a single RCT, a meta‐analysis should include a RIS at least as large as the sample size of an adequately powered single trial to reduce the risk of random error. A Trial Sequential Analysis calculates the RIS in a meta‐analysis and provides trial sequential monitoring boundaries with an adjusted P value.

When new trials emerge, multiple analyses of accumulating data lead to repeated significance testing and hence introduce multiplicity. Use of conventional P values exacerbates the risk of random error (Berkey 1996; Lau 1995; Wetterslev 2017). Meta‐analyses not reaching the RIS are analysed with trial sequential monitoring boundaries analogous to interim monitoring boundaries in a single trial (Wetterslev 2008; Wetterslev 2017).

If a Trial Sequential Analysis does not result in significant findings (no Z‐curve crossing the trial sequential monitoring boundaries) before the RIS has been reached, the conclusion should be that more trials are needed to reject or accept an intervention effect that was used to calculate the required sample size, or when the cumulated Z‐curve enters the futility area, the anticipated intervention effect should be rejected.

For calculations with the Trial Sequential Analysis programme, we included trials with zero events by substituting 0.25 for zero (CTU 2022; Thorlund 2011).

For the outcomes 'total serious adverse events' and 'total non‐serious adverse events', we calculated the a priori diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS; i.e. number of participants in the meta‐analysis required to detect or reject a specific intervention effect) and performed a Trial Sequential Analysis for these outcomes based on the following assumptions (Brok 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008; Wetterslev 2009).

Proportion of participants in the control group with adverse events

Relative risk reduction of 20% (25% on 'total serious adverse events')

Type I error of 5%

Type II error of 20%

Observed diversity of the meta‐analysis

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed the following subgroup analyses of teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms (primary outcome) to test the robustness of this estimate.

Age of participants (trials with participants aged 2 to 6 years compared to trials with participants aged 7 to 11 years compared to trials with participants aged 12 to 18 years)

Sex (boys compared to girls)

Comorbidity (children with comorbid disorders compared to children without comorbid disorders)

Type of ADHD (participants with predominantly inattentive subtype compared to participants with predominantly combined subtype)

After learning about other factors that may affect the effects of methylphenidate, we performed the following additional post hoc subgroup analyses on teacher‐rated ADHD symptoms to test the robustness of the estimate.

Types of scales (e.g. Conners' Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS; Conners 1998a), compared to Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behavior (SWAN) Scale (Swanson 2006)

Dose of methylphenidate (low dose (≤ 20 mg/day or ≤ 0.6 mg/kg/day) compared to moderate or high dose (> 20 mg/day or > 0.6 mg/kg/day)).

Duration of treatment (short‐term trials (≤ 6 months) compared to long‐term trials (> 6 months))

Trial design (parallel‐group trials compared to cross‐over trials (first‐period data and end‐of‐last‐period data))

Medication status before randomisation (medication naive (> 80% of included participants were medication naive) compared to not medication naive (< 20% of included participants were medication naive))

Risk of bias (trials at low risk of bias compared to trials at high risk of bias)

Enrichment trials. Enrichment trials (trials that excluded methylphenidate non‐responders, placebo responders, and/or participants who had adverse events due to the medication before randomisation) compared to trials without enrichment

Vested interest ((conflict of interest regarding funding) trials at either high or unclear risk of vested interest compared to trials at low risk of vested interest). Our assessment of vested interest for the individual studies can be seen in Table 2.

Type of control group (trials with placebo control group compared to trials with no‐intervention control group)

1. Vested interest of included studies.

| Study | Vested interest | Support for judgement |

| Abikoff 2009 | High | Funding: investigator‐initiated trial funded by a grant from Ortho‐McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs to Dr Abikoffx Conflicts of interest: Drs Abikoff and Gallagher have a contract with Multi‐Health Systems to further develop the Children’s Organizational Skills Scale (COSS) used in this trial. Dr Abikoff has served on the ADHD Advisory Board of Shire Pharmaceuticals and of Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Dr Boorady has served on the ADHD Advisory Board and Speakers’ Bureau of Shire Pharmaceuticals. Other trial authors report no conflicts of interest |

| Ahmann 1993 | Low | Funding: trial was funded by Marshfield Clinic grants Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Arnold 2004 | High | Funding: trial was supported by the Celgene Corporation Conflicts of interest: Drs Arnold, Wigal and Bohan received research Funding from Celgene for the trial reported. Dr Wigal and Dr West are on the Advisory Panel and Speakers' Bureau for Novartis. Dr Arnold and Dr Bohan are on the Speakers' Bureau for Novartis. Dr Zeldis is Chief Medical Officer and Vice President of Medical Affairs at the Celgene Corporation. |

| Barkley 1989b | Low | Funding: trial was internally funded by the medical school Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Barkley 1991 | Low | Funding: research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Barkley 2000 | Low | Funding: University of Massachusetts Medical School Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Barragán 2017 | High | Funding: trial was funded by Vifor Pharma Conflict of interest: trial authors affiliated with the medical industry |

| Bedard 2008 | Low | Funding: funding and operating grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research and Funding from the Canada Research Chairs Programme Conflicts of interest: none |

| Bhat 2020 | High | Funding: this work was supported in part by a grant from the Fond de Recherche du Québec and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Weam Fageera is a recipient of a PhD scholarship from the Ministry of Education of Saudi Arabia. Conflicts of interest: authors affiliated with medical industry |

| Biederman 2003b | High | Funding: received from Novartis Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Bliznakova 2007 | Unclear | Funding: not declared Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Blum 2011 | High | Funding: trial was supported by an investigator‐initiated grant from Ortho McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, the manufacturer of OROS methylphenidate (Concerta) Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Borcherding 1990 | Unclear | Funding: not declared Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Brams 2008 | High | Funding: sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation Conflicts of interest: first trial author has been a speaker, consultant and advisory board member for Novartis and Shire |

| Brams 2012 | High | Funding: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, with the following involvement reported: design and conduct of the trial; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; and preparation, review and approval of the manuscript. All trial authors are employees or consultants or have received research grants from pharmaceutical companies. Conflicts of interest: all trial authors are employees or consultants or have received research grants from pharmaceutical companies. |

| Brown 1984a | Unclear | Funding: funded by National institute of Mental Health and National institutes of Health. Placebo and methylphenidate were supplied by CIBA‐GEIGY Corporation, Summit, New Jersey Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Brown 1985 | Unclear | Funding: research supported by US Public Health Services Grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and by the Biomedical Research Award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Methylphenidate provided by CIBA‐GEIGY Corporation, Summit, New Jersey Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Brown 1988 | Low | Funding: Biomedical Research Support Grant Program, Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health and Emory University Research Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Brown 1991 | Unclear | Funding: Biomedical Research Support Grant Program, Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, and by the Emory University Research Fund Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Buitelaar 1995 | Unclear | Funding: not declared Conflicts of interest: no affiliations with pharmaceutical companies were declared |

| Bukstein 1998 | Unclear | Funding: no Funding declared Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Butter 1983 | Low | Funding: the Scientific Development Group, Organon International BV, Oss, the Netherlands Conflicts of interest: none |

| Carlson 1995 | Unclear | Funding: not declared Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Carlson 2007 | High | Funding: research was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Indiana Conflicts of interest: Dr Carlson has received research support or has consulted with the following companies: Abbott Laboratories, Cephalon, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, McNeil, Otsuka and Shire Pharmaceuticals. Dr Dunn has received research support or has served on Speakers' Bureaus of the following companies: AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, National Institues of Health, Otsuka and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. Drs Kelsey, Ruff, Ball and Allen and Ms Ahrbecker are employees and/or shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. |

| Castellanos 1997 | Unclear | Funding: unclear Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Chacko 2005 | High | Funding: during the conduct of this research, Dr Pelham was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (MH48157, MH47390, MH45576, MH50467, MH53554, MH62946), NIAAA (AA06267, AA11873), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (DA05605, DA12414), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (NS39087), National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) (ES05015) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHHD) (HD42080) Conflicts of interest: several trial authors have affiliations with medical companies |

| Childress 2009 | High | Funding: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Novartis Pharma has been helping with development of the manuscript. Conflicts of interest: several trial authors have received research support from, are speakers for, are consultants of, are on the Advisory Board, have served on the Speakers' Bureaus of or are employees of several pharmaceutical companies |

| Childress 2017 | High | Funding: this trial was supported by funds from Neos Therapeutics, Inc, PI. Conflicts of interest: Carolyn R Sikes is affiliated with Neos Therapeutics, Inc. |

| Childress 2020a | High | Funding: trial was funded by Purdue Pharma Conflict of interest: trial authors affiliated with medical industry |

| Childress 2020b | High | Funding: trial funded by Ironshore Pharmaceuticals Conflict of interest: trial authors affiliated with the medical industry |

| Childress 2020c | High | Funding: trial funded by Rhodes Pharmaceuticals LP. Conflict of interest: authors affiliated with medical industry |

| Chronis 2003 | High | Funding: supported by a grant from Shire‐Richwood Pharmaceuticals, Incorporated ‐ manufacturer of Adderall ‐ and from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Conflict of interest: not declared |

| Coghill 2007 | High | Funding: this work was supported by a local trust through a Tenovus Scotland initiative. Conflicts of interest: some trial authors have affiliations with different pharmaceutical companies |

| Coghill 2013 | High | Funding: Shire Development LLC Conflicts of interest: C Anderson, R Civil, N Higgins, A Lyne and L Squires are employees of Shire and own stock/stock options. Some trial authors have received compensation for serving as consultants or speakers, or they or the institutions they work for have received research support or royalties from different companies or organisations. |

| Connor 2000 | Low | Funding: supported by a UMMS (University of Massachusetts Medical School) Small Grants Project Award Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Cook 1993 | Low | Funding: supported by the Medical Center Rehabilitation Hospital Foundation and the School of Medicine, University North Dakota; the Veterans Hospital; the Dakota Clinic; and The Neuropsychiatric Institute, Fargo, North Dakota Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Corkum 2008 | Low | Funding: research was supported by a grant from the Izaak Walton Killam IWK Health Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia Conflicts of interest: "none declared" |

| Corkum 2020 | Low | Funding: the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Conflicts of interest: there were no conflicts of interest of any trial investigator with the pharmaceutical or equipment manufacturers. |

| Cox 2006 | High | Funding: trial was supported by Funding from McNeil Pediatrics, a division of McNeil‐PPC Incorporated Conflicts of interest: none declared |

| CRIT124US02 | High | Funding: trial by Novartis Conflicts of interest: no information on investigators |

| Döpfner 2004 | High | Funding: trial was conducted and sponsored by MEDICE Arzneimittel Pütter GmbH & Co. KG as part of the drug approval process for Medikinet‐Retard Conflicts of interest: some trial authors have affiliations with medical companies |

| Douglas 1986 | Low | Funding: research was supported by Grant Number MA 6913, from the Medical Research Council of Canada Conflicts of interest: not declared |

| Douglas 1995 | Low | Funding: grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada and by William T Grant Foundation Faculty Scholar Program Conflicts of interest: none |

| DuPaul 1996 | Unclear | Funding: unclear Conflict of interest: no conflicts of interest declared |

| Duric 2012 | Low | Funding: the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department of Helse Fonna Hospital Haugesund, Helse Fonna Trust Haugesund, Norway Conflicts of interest: trial authors declare no potential conflicts of interests with regard to authorship or publication of this article. |

| Epstein 2011 | Low | Funding: National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Conflicts of interest: no evidence of conflicts of interest |

| Fabiano 2007 | Low | Funding: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant MH62946 Conflicts of interest: supported only by National Institutes |

| Findling 2006 | High | Funding: provided by Celltech Americas Incorporated, currently part of UCB (Union Chimique Belge) Conflicts of interest: Drs Hatch and DeCory and Miss Cameron were employees of Celltech at the time of this trial. Dr Findling received research support, acted as a consultant and/or served on a Speakers' Bureau for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celltech‐Medeva, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, New River, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi‐Synthelabo, Shire, Solvay and Wyeth. Dr Quinn claims no competitive interests. Dr McDowell has consulted for Janssen‐Cilag and Lilly. |

| Findling 2007 | High | Funding: the Stanley Medical Research Institute Conflicts of interest: some trial authors have affiliations with pharmaceutical companies |

| Findling 2008 | High | Funding: Shire Development Incorporated, Wayne, Pennsylvania Conflicts of interest: some trial authors received research support, acted as consultants and/or served on a Speakers' Bureau for several pharmaceutical companies. |