TO THE EDITOR:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released updated official mortality data that showed 45,222 firearm-related deaths in the United States in 2020 — a new peak.1 Although previous analyses have shown increases in firearm-related mortality in recent years (2015 to 2019), as compared with the relatively stable rates from earlier years (1999 to 2014),2,3 these new data show a sharp 13.5% increase in the crude rate of firearm-related death from 2019 to 2020.1 This change was driven largely by firearm homicides, which saw a 33.4% increase in the crude rate from 2019 to 2020, whereas the crude rate of firearm suicides increased by 1.1%.1 Given that firearm homicides disproportionately affect younger people in the United States,3 these data call for an update to the findings of Cunningham et al. regarding the leading causes of death among U.S. children and adolescents.4

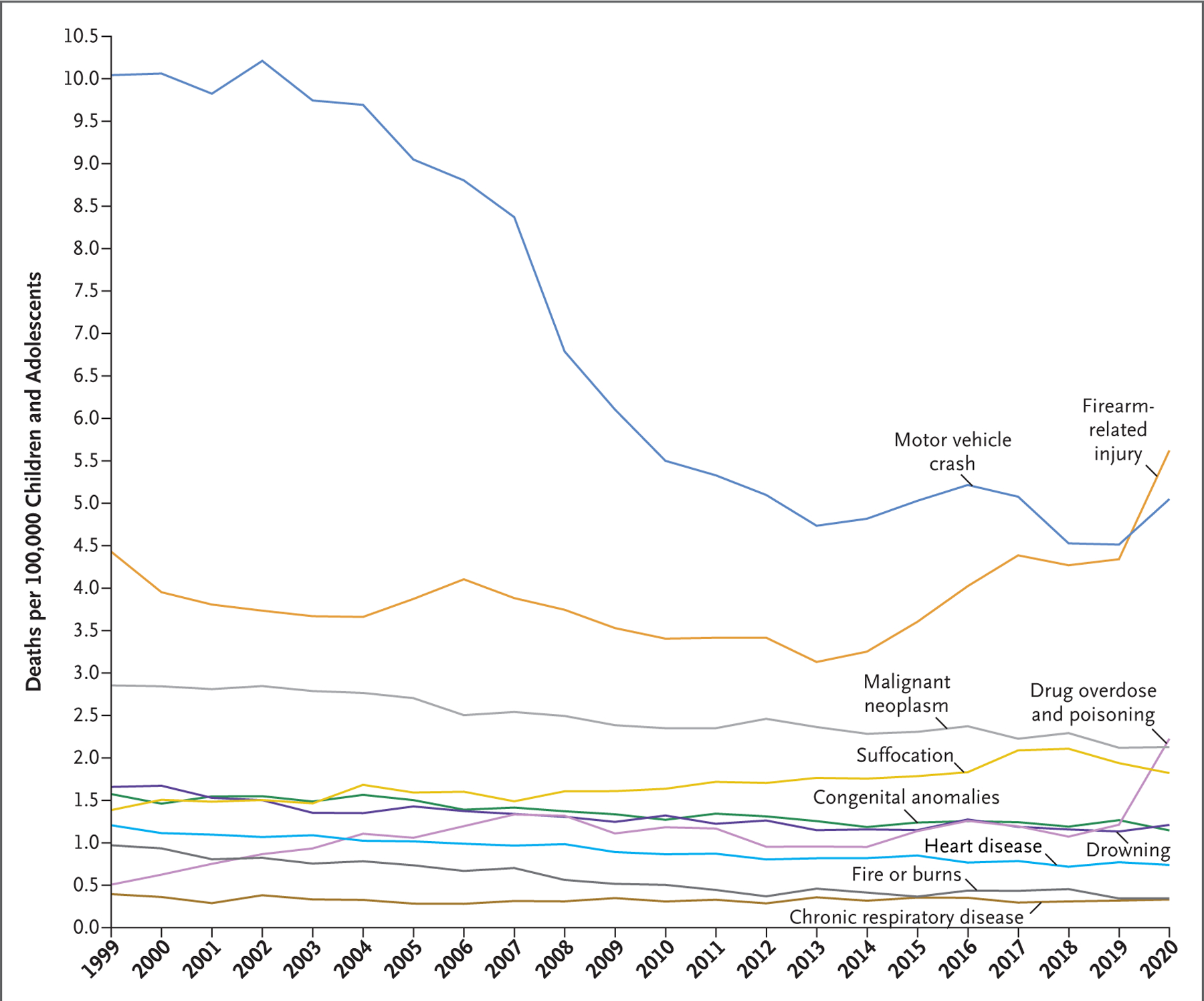

The previous analysis, which examined data through 2016, showed that firearm-related injuries were second only to motor vehicle crashes (both traffic-related and nontraffic-related) as the leading cause of death among children and adolescents, defined as persons 1 to 19 years of age.4 Since 2016, that gap has narrowed, and in 2020, firearm-related injuries became the leading cause of death in that age group (Fig. 1). From 2019 to 2020, the relative increase in the rate of firearm-related deaths of all types (suicide, homicide, unintentional, and undetermined) among children and adolescents was 29.5% — more than twice as high as the relative increase in the general population. The increase was seen across most demographic characteristics and types of firearm-related death (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org).

Figure 1. Leading Causes of Death among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1999 through 2020.

Children and adolescents are defined as persons 1 to 19 years of age.

In addition, drug overdose and poisoning increased by 83.6% from 2019 to 2020 among children and adolescents, becoming the third leading cause of death in that age group. This change is largely explained by the 110.6% increase in unintentional poisonings from 2019 to 2020. The rates for other leading causes of death have remained relatively stable since the previous analysis, which suggests that changes in mortality trends among children and adolescents during the early Covid-19 pandemic were specific to firearm-related injuries and drug poisoning; Covid-19 itself resulted in 0.2 deaths per 100,000 children and adolescents in 2020.1

Although the new data are consistent with other evidence that firearm violence has increased during the Covid-19 pandemic,5 the reasons for the increase are unclear, and it cannot be assumed that firearm-related mortality will later revert to prepandemic levels. Regardless, the increasing firearm-related mortality reflects a longer-term trend and shows that we continue to fail to protect our youth from a preventable cause of death. Generational investments are being made in the prevention of firearm violence, including new funding opportunities from the CDC and the National Institutes of Health, and funding for the prevention of community violence has been proposed in federal infrastructure legislation. This funding momentum must be maintained.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Wonder. 2021. (https://wonder.cdc.gov/). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstick JE, Zeoli A, Mair C, Cunningham RM. US firearm-related mortality: national, state, and population trends, 1999–2017. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:1646–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstick JE, Carter PM, Cunningham RM. Current epidemiological trends in firearm mortality in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:241–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2468–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schleimer JP, McCort CD, Shev AB, et al. Firearm purchasing and firearm violence during the coronavirus pandemic in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Inj Epidemiol 2021;8:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.