Abstract

Background

Both behavioural support (including brief advice and counselling) and pharmacotherapies (including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline and bupropion) are effective in helping people to stop smoking. Combining both treatment approaches is recommended where possible, but the size of the treatment effect with different combinations and in different settings and populations is unclear.

Objectives

To assess the effect of combining behavioural support and medication to aid smoking cessation, compared to a minimal intervention or usual care, and to identify whether there are different effects depending on characteristics of the treatment setting, intervention, population treated, or take‐up of treatment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register in July 2015 for records with any mention of pharmacotherapy, including any type of NRT, bupropion, nortriptyline or varenicline.

Selection criteria

Randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trials evaluating combinations of pharmacotherapy and behavioural support for smoking cessation, compared to a control receiving usual care or brief advice or less intensive behavioural support. We excluded trials recruiting only pregnant women, trials recruiting only adolescents, and trials with less than six months follow‐up.

Data collection and analysis

Search results were prescreened by one author and inclusion or exclusion of potentially relevant trials was agreed by two authors. Data was extracted by one author and checked by another.

The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months of follow‐up. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence for each trial, and biochemically validated rates if available. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each study. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model.

Main results

Fifty‐three studies with a total of more than 25,000 participants met the inclusion criteria. A large proportion of studies recruited people in healthcare settings or with specific health needs. Most studies provided NRT. Behavioural support was typically provided by specialists in cessation counselling, who offered between four and eight contact sessions. The planned maximum duration of contact was typically more than 30 minutes but less than 300 minutes. Overall, studies were at low or unclear risk of bias, and findings were not sensitive to the exclusion of any of the six studies rated at high risk of bias in one domain. One large study (the Lung Health Study) contributed heterogeneity due to a substantially larger treatment effect than seen in other studies (RR 3.88, 95% CI 3.35 to 4.50). Since this study used a particularly intensive intervention which included extended availability of nicotine gum, multiple group sessions and long term maintenance and recycling contacts, the results may not be comparable with the interventions used in other studies, and hence it was not pooled in other analyses. Based on the remaining 52 studies (19,488 participants) there was high quality evidence (using GRADE) for a benefit of combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural treatment compared to usual care, brief advice or less intensive behavioural support (RR 1.83, 95% CI 1.68 to 1.98) with moderate statistical heterogeneity (I² = 36%).

The pooled estimate for 43 trials that recruited participants in healthcare settings (RR 1.97, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.18) was higher than for eight trials with community‐based recruitment (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.76). Compared to the first version of the review, previous weak evidence of differences in other subgroup analyses has disappeared. We did not detect differences between subgroups defined by motivation to quit, treatment provider, number or duration of support sessions, or take‐up of treatment.

Authors' conclusions

Interventions that combine pharmacotherapy and behavioural support increase smoking cessation success compared to a minimal intervention or usual care. Updating this review with an additional 12 studies (5,000 participants) did not materially change the effect estimate. Although trials differed in the details of their populations and interventions, we did not detect any factors that modified treatment effects apart from the recruitment setting. We did not find evidence from indirect comparisons that offering more intensive behavioural support was associated with larger treatment effects.

Keywords: Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Behavior Therapy, Behavior Therapy/methods, Combined Modality Therapy, Combined Modality Therapy/methods, Counseling, Counseling/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Smoking, Smoking/therapy, Smoking Cessation, Smoking Cessation/methods, Tobacco Use Cessation Devices

Plain language summary

Does a combination of stop smoking medication and behavioural support help smokers to stop?

Background

Behavioural support (such as brief advice and counselling) and medications (including varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine replacement therapies like patches or gum) help people quit smoking. Many guidelines recommend combining medication and behavioural support to help people stop smoking, but it is unclear if some combinations are more effective than others, or if the combination of medication and behavioural support works better in some settings or groups than in others.

Study Characteristics

In July 2015 we searched for studies which tested combinations of behavioural support and medication to help smokers to stop compared to usual care or brief behavioural support. People who smoked were recruited mainly in health care settings. Some trials only enrolled people who said they wanted to try to quit at that time, but some included people who weren't planning to quit. Studies had to report how many people had stopped smoking after at least six months.

Results

We found 53 studies with a total of over 25,000 participants. One very large study found a large benefit. It gave intensive support including nicotine gum, multiple group sessions, and long term contact to help people stay quit or encourage additional quit attempts. Because it was not typical of most treatment programmes, it was not included when we estimated the likely benefit, although it shows that such intensive support can be very effective. Based on the remaining 52 studies, we found high quality evidence that using a combination of behavioural support and medication increases the chances of successfully quitting after at least six months. Combining the results suggests that the chance of success is increased by 70 to 100 percent compared to just brief advice or support. There was some evidence that the effect tended to be larger when participants were recruited in healthcare settings. There was no clear evidence that providing more contact increased the number of people who quit smoking at six months or longer. .

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation.

| Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People who smoke Settings: Community and healthcare settings Intervention: Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions, compared to brief advice or usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions | |||||

|

Cessation at longest follow‐up (all but Lung Health Study) Follow‐up: 6 months+ |

86 per 10001 | 157 per 1000 (144 to 170) | RR 1.83 (1.68 to 1.98) | 19488 (52 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2 | |

| Cessation at longest follow‐up (Lung Health Study only) Follow‐up: mean 12 months | 90 per 1000 | 350 per 1000 (302 to 406) | RR 3.88 (3.35 to 4.5) | 5887 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | Substantially larger treatment effect than seen in other studies. Particularly intensive intervention, hence not included in main analysis. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Baseline risk calculated as mean control group risk for both comparisons 2 Some evidence of asymmetry in a funnel plot; excess of small trials detecting larger effects. However, in a sensitivity analysis, removing smaller studies did not markedly decrease the pooled estimate. 3 Downgraded due to indirectness. As this study had a particularly intensive intervention, the results may not be generalisable to real world treatment programmes.

Background

Giving up smoking is the most effective way for people who smoke to reduce their risk of smoking related disease and premature death. Behavioural support and pharmacotherapies help people to stop smoking. Behavioural support interventions include written materials containing advice on quitting, multisession group therapy programmes or individual counselling sessions in person or by telephone. Providing standard self‐help materials alone seems to have a small effect on success, but there is evidence of a benefit of individually tailored self‐help materials or more intensive advice or counselling (Lancaster 2005; Hartmann‐Boyce 2014). Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline, bupropion, cytisine and nortriptyline all increase the long‐term success of quit attempts (Cahill 2013). Many clinical practice guidelines recommend that healthcare providers offer people who are prepared to make a quit attempt both classes of intervention on the basis that they may have an additive or even multiplicative effect. This approach assumes that the two types of treatment have complementary modes of action, and may independently improve the chances of maintaining long‐term abstinence. However, it is recognised that many people who use pharmacotherapy will not take up the offer of intensive behavioural support. NRT products are available over the counter (OTC) without a prescription in many countries, and people who purchase them may not access any specific behavioural support. People who obtain prescriptions for pharmacotherapies are more likely to receive some support, but this may be focused on explaining proper use of the drug rather than on behavioural counselling. Surveys suggest that the proportion of people who use both types of treatment when attempting to stop smoking is low (Shiffman 2008; Kotz 2009b). The aim of this review is to assess the the effect of the combined intervention of pharmacotherapy and behavioural support, compared to using neither type of treatment, or receiving only brief advice or behavioural support.

Other Cochrane Tobacco Addiction reviews have evaluated the separate effects of behavioural and pharmaceutical interventions. In order to quantify these individual effects, these reviews restrict inclusion to trials where the intervention under investigation is unconfounded. By unconfounded, we mean that trials of pharmacotherapies had to provide the same amount of behavioural support (materials, advice, counselling contacts) to all participants whether they receive active treatment or a placebo or no medication. Likewise, when behavioural interventions are evaluated there must be no systematic difference in the offer of medications between the active and control arms of the trial.

The findings from reviews of unconfounded trials support the use of combined pharmacological and behavioural therapy, but do not provide a direct estimate of the size of the benefit to be expected from combining the two types of treatment. The aim of this review is to synthesize the evidence from trials that directly evaluate the use of an intervention combining pharmacotherapy and behavioural support, where the control condition includes neither pharmacotherapy nor the same intensity of behavioural support. The control will involve either usual care, or brief advice. If the pharmacotherapy and the behavioural support components exert independent effects on successful cessation, these trials might be expected to give considerably larger treatment effects than would be achieved from either the behavioural or the medication component alone. However, other factors may affect the size of this effect. In particular, pragmatic trials of interventions in healthcare settings may find smaller effects than placebo‐controlled pharmacotherapy studies in research settings, as delivery of the intervention components may be lower. To address this, we set out to identify moderators that might lead to heterogeneity in effects of combined treatment, including the motivation of participants, the nature of the treatment setting, and the type of therapist. We also aimed to categorize by the intensity of behavioural support, based on number and duration of contacts, in order to evaluate whether the intensity of the behavioural support affected treatment success. Previous meta‐analyses have suggested that there is a dose response, with more contacts improving outcomes amongst people receiving pharmacotherapy (Fiore 2008 table 6.23). We also considered the degree to which participants used both medication and behavioural components as a possible explanation for any heterogeneity.

For this review we identified trials of interventions that combined pharmacotherapies (including NRT, varenicline, bupropion, cytisine, or nortriptyline) with behavioural support (tailored materials, brief advice, in person or telephone counselling) and that compared outcomes against a control group that received either usual care or a brief cessation component (i.e. advice to quit but no other behavioural support or medication common to the intervention). A companion review will evaluate whether more intensive behavioural support improves cessation outcomes for people using pharmacotherapy, using the direct evidence from trials that compare different levels of behavioural support for people receiving any type of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation (Stead 2015).

Objectives

To assess the effect of combining behavioural support and medication to aid smoking cessation, compared to using neither, and to identify whether there are different effects depending on characteristics of the treatment setting, intervention, population treated, or take‐up of treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trials. We did not exclude studies on the basis of publication status or language of publication.

Types of participants

We included trials that recruited people who smoke in any setting, with the exception of trials which only recruit pregnant women or adolescents. These populations are considered in specific reviews. Trial participants did not need to be selected according to their interest in quitting or their suitability for pharmacotherapy.

Types of interventions

We included interventions for increasing smoking cessation that included behavioural support and the availability of pharmacotherapy, regardless of type of pharmacotherapy. We excluded trials where fewer than 20% of participants were eligible for or used pharmacotherapy. The provision of written information or brief instructions on correct use of the pharmacotherapy was not regarded as behavioural support. The control group should not have been systematically offered pharmacotherapy but we did not exclude studies where some control group participants obtained medication from other sources. Control group participants could be offered usual care, self‐help materials or brief advice on quitting, but support had to have been of a lower intensity than that given to intervention participants.

Types of outcome measures

Following the standard methodology of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, the primary outcome is smoking cessation at the longest follow‐up using the strictest definition of abstinence, that is, preferring sustained over point prevalence abstinence and using biochemically validated rates where available. We also noted any other abstinence outcomes reported and conducted sensitivity analyses to test if the choice of outcome affected the results of meta‐analysis. We excluded trials reporting less than six months follow‐up from the start of intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified trials from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Specialised Register (the Register). This is generated from regular searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO for trials of smoking cessation or prevention interventions. The most recent search of the Register was in July 2015. At the time of the search the Register included the results of searches of the CENTRAL to issue 4, 2015; MEDLINE (via OVID) from 1946 to update 20150501; EMBASE (via OVID) from 1974 to week 201519 and PsycINFO (via OVID) from 1967 to update 20150506. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched.

We searched the Register for records with any mention of pharmacotherapy in title, abstract or indexing terms (see Appendix 1 for the final search strategy). We checked titles and abstracts to identify trials of interventions for smoking cessation that combined pharmacotherapy with behavioural support. We also checked the excluded study lists of reviews of behavioural therapies and pharmacotherapy for trials excluded because pharmacotherapy was confounded with additional behavioural support compared to the control group. Trials with a factorial design that varied both pharmacotherapy and behavioural conditions were also considered for inclusion. We also tested an additional MEDLINE search using the smoking related terms and design limits used in the standard register search and the MeSH terms ‘combined modality therapy’ or (Drug Therapy and (exp Behavior therapy or exp Counseling)). This search retrieved a subset of records already screened for the inclusion in the Register and was used to assess whether it might retrieve studies where there was no mention of a specific cessation pharmacotherapy in the title, abstract or indexing. We did not find any additional studies from this.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

LS identified potentially relevant trial reports according to the criteria above. Areas of uncertainty were discussed with PK and TL. LS and either TL or PK extracted data.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following information from trial reports:

Country and setting of trial

Method of recruitment, including any selection by motivation to quit

Method of sequence generation

Method of allocation concealment

Characteristics of participants including gender, age, smoking rate

Characteristics of intervention deliverer

Intervention components: type, dose and duration of pharmacotherapy, type and duration of behavioural support

Control group components

Outcomes: primary outcome length of follow‐up and definition of abstinence; other follow‐ups and abstinence definitions; use of biochemical validation; loss to follow‐up.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Studies were evaluated on the basis of the randomization procedure and allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data assessment and any other bias (Schulz 2002a; Schulz 2002b; Higgins 2011). Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot.

Measures of treatment effect

Trial effects were expressed as a relative risk (RR): (quitters in treatment group/total randomized to treatment group)/ (quitters in control group/total randomized to control group).

Dealing with missing data

Numbers lost to follow‐up were reported by group where available. Following standard Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group methods, people lost to follow‐up were assumed to be smoking and included in the denominators for calculating the RR. Any deaths during follow‐up were reported separately and excluded from denominators.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered pooling all trials comparing combined therapy to usual care/minimal intervention control if heterogeneity as assessed by the I² statistic (Higgins 2003) was less than 50%.

Data synthesis

For groups of trials where meta‐analysis was judged appropriate, relative risks were pooled using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model, and a pooled estimate with 95% confidence intervals reported.

If trials had more than one intervention condition we compared the most intensive combination of behavioural support and pharmacotherapy to the control in the main analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We undertook planned subgroup analyses by setting, participant selection, intervention provider, number of sessions, total duration of contact, and take‐up of treatment. The subgroups are listed below.

Setting

Recruited in healthcare settings

Recruited as community volunteers

Participant selection

Selected for willingness to make a quit attempt/ high take‐up of pharmacotherapy

Not selected for interest in quitting/ low take‐up of pharmacotherapy

Not explicitly selected but study procedures and participant characteristics suggested that most participants were willing to make a quit attempt

Provider

Usual care provider

Specialist in smoking cessation

Peer group counsellor (ex‐smoker)

Intensity

We conducted alternative analyses of intensity adapted from two of the categories used in the US Guidelines (Fiore 2008). We used planned contact time and number of sessions where possible. If this was variable or unclear we used any report of actual delivery.

We categorised total amount of contact time as zero (if the only support was sent by mail), 1 to 30 minutes (collapsing one to three and 4 to 30 US guideline categories), 31 to 90, 91 to 300, and over 300 minutes.

Number of person‐to‐person sessions was categorised as zero, one to three (instead of zero to one and two to three as used in US guidelines), four to eight and over eight sessions.

Treatment take‐up (compliance with medication and behavioural support)

We expected this group of trials to include some pragmatic studies where participants are offered treatment but did not use all the components offered. After pilot testing, we categorised studies into three groups:

High – over 70% starting pharmacotherapy and receiving at least one session of support (where applicable)

Moderate – Over 30% starting pharmacotherapy and over 50% receiving at least one session of support

Low – less than 30% starting pharmacotherapy or less than 50% receive at least one session of support

We did not separate trials using different pharmacotherapies in initial analyses but we considered the type of pharmacotherapy as an explanation for remaining heterogeneity.

Where there was evidence from subgroup analyses of clinically relevant differences between categories in any of the subgroups above, we used meta regression (Stata) to explore whether any of the characteristics were effect modifiers, including each of the characteristics as categorical (dummy) variables. To assess possible effect modification according to the intensity of intervention received, we also included number of sessions, amount of contact time and take‐up together in a single meta‐regression analysis. Since these analyses were not pre‐specified they are hypothesis generating only.

Sensitivity analysis

We considered the sensitivity of the results to changes in the cut‐off range for categories outlined above. If data for multiple outcomes were provided, we conducted sensitivity analyses to test if the choice of outcome affected the results. We also conducted sensitivity analyses removing smaller studies to assess possible impact of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The original register search retrieved approximately 2200 records, approximately 400 additional records were screened for this update. Most of the records that did report trials of interventions for smoking cessation were not relevant because they were placebo‐controlled trials of pharmacotherapies, in which the behavioural support was the same for intervention and control conditions. We identified 41 studies for inclusion in the original review and a further 12 for the update. Many included studies were identified via more than one study report. All reports related to a study are listed in the reference section with the primary report used for data extraction identified. Trials are identified by the first author and year of publication of the main study report. A further 90 studies are listed as excluded.

Included studies

We identified 53 studies that met all inclusion criteria with a total of more than 25,000 participants. Most have been published since 2000, with the earliest published in 1988. One trial had almost 6000 participants (Lung Health Study) and one over 2000 (Hollis 2007). Thirty‐one trials had more than 100 participants in the intervention arm and most of the remainder had more than 50 in the intervention arm. Twelve trials are new for this update (Murray 2013; Prochaska 2014; Rigotti 2014; Stockings 2014; Winhusen 2014; Bernstein 2015; Haas 2015; Hickman 2015; Lee 2015; Peckham 2015; Perez‐Tortosa 2015)

About half the studies were conducted in the USA. Of the others there were five from Canada (Wilson 1988; Reid 2003; Ratner 2004; Chouinard 2005; Lee 2015), four from Australia (Vial 2002; Wakefield 2004; Baker 2006; Stockings 2014), three from Denmark (Tonnesen 2006; Villebro 2008; Thomsen 2010), three from Spain (Juarranz Sanz 1998; Rodriguez 2003; Perez‐Tortosa 2015), four from the UK (Molyneux 2003; Binnie 2007; Murray 2013; Peckham 2015) and one each from Brazil (Otero 2006), Italy (Segnan 1991), the Netherlands (Kotz 2009), Sweden (Sadr Azodi 2009), Japan (Hanioka 2010) and Hong Kong (Chan 2010).

Details of can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table. Appendix 2 tabulates the following study characteristics: setting and provider; selection by motivation; number and total duration of contact categories; and level of take‐up of treatment.

Trial setting and recruitment

A high proportion of trials were conducted in healthcare settings and/or recruited people with specific health needs. These included ten trials in general (non psychiatric) hospital inpatients (Simon 1997; Lewis 1998; Vial 2002; Molyneux 2003; Reid 2003; Chouinard 2005; Mohiuddin 2007; Brandstein 2011; Murray 2013; Rigotti 2014), one in emergency room patients (Bernstein 2015), five in patients awaiting admission for surgery (Ratner 2004; Villebro 2008; Sadr Azodi 2009; Thomsen 2010; Lee 2015), three in psychiatric hospital inpatients (Stockings 2014; Prochaska 2014; Hickman 2015), three for other mental health patients (Baker 2006; Hall 2006; Peckham 2015), four in outpatient substance abuse treatment programmes (Cooney 2007; Reid 2008; Carmody 2012; Winhusen 2014), one in an AIDS clinic (Wewers 2000), two for people with cancer (Wakefield 2004; Duffy 2006), and one for cancer survivors (Emmons 2005). Eight trials recruited patients of primary care clinics (Wilson 1988; Ockene 1991; Segnan 1991; Juarranz Sanz 1998; Katz 2004; Perez‐Tortosa 2015 (diabetic patients); Haas 2015) or primary care and women's health clinics (Wewers 2009), and two recruited dental clinic patients (Binnie 2007; Hanioka 2010). One recruited Chinese men with erectile dysfunction (Chan 2010). Three recruited people identified as having mild airway obstruction (Lung Health Study; Kotz 2009) or COPD (Tonnesen 2006). One recruited employees at annual occupational health checks (Rodriguez 2003). Okuyemi 2007 recruited residents of low‐income public housing departments. Schauffler 2001 recruited members of health maintenance organisations and Velicer 2006 recruited Veterans Administration medical centre patients, in both cases using proactive telephone contact. An 2006 recruited Veterans Administration medical centre patients by mail. Hall 2002, Otero 2006 and McCarthy 2008 recruited community volunteers motivated to quit and Hollis 2007 recruited callers to a quitline seeking cessation assistance.

Selection by motivation to quit

We tried to classify trials according to whether or not willingness to make a quit attempt was required for study eligibility. In some studies motivation was an explicit requirement, including four trials that enrolled motivated volunteers for pharmacotherapy trials involving placebos (Hall 2002; Tonnesen 2006; McCarthy 2008; Kotz 2009). In some study reports there was no mention of motivation as a requirement for inclusion. Some of these trials did recruit some people with no plans to quit smoking. In others, the method of recruitment or the requirement to adhere to a protocol made it seem likely that only people interested in attempting to quit would enrol. We grouped the studies as follows:

Motivation required (22 trials, 42%): Simon 1997; Lewis 1998; Wewers 2000; Hall 2002; Vial 2002; Reid 2003; Rodriguez 2003; An 2006; Baker 2006; Otero 2006; Tonnesen 2006; Cooney 2007; Hollis 2007; McCarthy 2008; Reid 2008; Kotz 2009: Chan 2010; Hanioka 2010; Carmody 2012; Rigotti 2014; Winhusen 2014; Peckham 2015.

Motivation not required but participants likely to have been interested in quitting (10 trials, 19%): Juarranz Sanz 1998; Molyneux 2003; Wakefield 2004; Mohiuddin 2007; Okuyemi 2007; Villebro 2008; Sadr Azodi 2009, Wewers 2009; Brandstein 2011; Haas 2015.

Not selected by motivation (21 trials, 40%): Wilson 1988; Ockene 1991; Segnan 1991; Lung Health Study; Schauffler 2001; Katz 2004; Ratner 2004; Chouinard 2005; Emmons 2005; Duffy 2006; Hall 2006; Velicer 2006; Binnie 2007; Thomsen 2010; Hickman 2015; Lee 2015; Murray 2013; Bernstein 2015; Perez‐Tortosa 2015, Prochaska 2014; Stockings 2014.

Participant characteristics

Trials typically had between 35 to 65% female participants. Two trials recruited only women (Wewers 2009; Thomsen 2010) and one only men (Chan 2010). Five trials in the US Veterans Administration medical system had higher proportions of men (Simon 1997; An 2006; Velicer 2006; Cooney 2007; Carmody 2012) as did a Spanish workplace trial (Rodriguez 2003). The average age typically ranged from low 40's to mid 50's. The age was younger in a trial amongst survivors of childhood cancer (Emmons 2005).

Provider characteristics

Most counselling and support was provided by specialist cessation counsellors or trained trial personnel. In a small subgroup the intervention was largely given by usual care providers including general practitioners/family physicians (Ockene 1991; Segnan 1991; Juarranz Sanz 1998; Perez‐Tortosa 2015), dental hygienists (Binnie 2007), dentists and dental hygienist (Hanioka 2010) or occupational physicians (Rodriguez 2003). Two studies used peer group counsellors (Emmons 2005;Wewers 2000) and one used trained lay advisers (Wewers 2009).

Intervention characteristics

The typical intervention involved multiple contacts with a specialist cessation adviser or counsellor, with most participants using some pharmacotherapy and receiving multiple contacts. However, there was a great deal of variation, including some interventions which involved making pharmacotherapy and behavioural components available to a large population in which take‐up of treatment was low (Schauffler 2001), or providing a brief intervention to all participants and offering stepped care for those willing to set a quit date (Reid 2003; Katz 2004). One intervention was delivered entirely by mail or prerecorded phone messages, using an expert system for tailoring contact (Velicer 2006) and two by telephone counselling alone (Hollis 2007; Haas 2015). All others included some face‐to‐face contact but additional sessions was sometimes provided by telephone. More than half the trials (n = 28, 53%) offered between four and eight sessions and a quarter (n = 13) over eight sessions. The modal category for contact time was 91 to 300 minutes (n = 22, 42%), with 17 (32%) offering between 31 and 90 minutes and eight (15%) over 300 minutes. We categorised interventions according to the maximum planned contact unless session duration was not described, so the typical time per participant would have been smaller, even in studies where the take‐up of treatment was high.

The treatment offered to the control group typically involved brief advice and self‐help materials.

Excluded studies

We list 90 studies as excluded. In most of these there was no difference between treatment conditions in the use of pharmacotherapy, and the trial tested different types or amounts of adjunct behavioural support. Trials of this type contribute to a separate review (Stead 2015). A small number of studies did not report six month or longer follow‐up. Reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

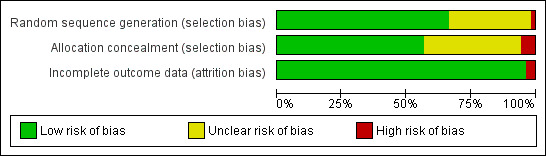

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 1 presents review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item as percentages across all included studies. We did not judge any studies to be at risk of 'other' bias.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

All studies reported that treatment allocation was random, with more than half explicitly describing an adequate method of generating the randomization schedule. One cluster randomized study was judged at high risk of bias because the unit of assignment was the ward, and an imbalance in the type of ward assigned to each condition lead to an imbalance in participant characteristics (Murray 2013). Thirty (57%) reported a procedure for allocation concealment that we judged to be at a low risk of bias. Three studies were judged at high risk of selection bias (Wilson 1988; Duffy 2006; Perez‐Tortosa 2015), two of which were cluster randomized. The participants in Wilson 1988 were recruited by receptionists who could not be blind to practice condition, and there were baseline differences in consent rate and in motivation to quit between conditions. Some participants in Perez‐Tortosa 2015 were recruited in health centres after allocation. Duffy 2006 recruited cancer patients with either smoking, alcohol or depression problems, and had more smokers in the intervention group suggesting possible recruitment bias. The other 20 (38%) trial reports gave too little information about allocation procedures to be certain that the risk of bias was low, and were hence judged to be at unclear risk of bias in this domain.

Blinding

We did not formally evaluate blinding of participants, providers or other personnel. It was almost always unclear whether or not participants would have known that they were in a control condition, but most controls did include advice and support for smoking cessation. Providers could not have been blind to treatment condition. Self‐reported smoking status was biochemically validated at longest follow‐up in 35 studies, with twelve of these measuring cotinine and the remainder carbon monoxide (CO). Seven studies either did not collect samples at final follow‐up (Sadr Azodi 2009; Bernstein 2015; Lee 2015) or did not obtain samples from enough participants and did not report validated quit rates (Reid 2003; Katz 2004; Villebro 2008; Hickman 2015). Eleven studies did not attempt any type of validation (Ockene 1991; Schauffler 2001; Emmons 2005; An 2006; Duffy 2006; Otero 2006; Velicer 2006; Hollis 2007; Thomsen 2010; Brandstein 2011; Haas 2015).

Incomplete outcome data

We classified two studies at high risk of attrition bias. In Hanioka 2010 a number of control participants declined consent once told their treatment group. In Perez‐Tortosa 2015 a number of participants were excluded from analyses because of a lack of baseline data, and losses to follow‐up were also excluded from reported analyses. In other studies, later dropouts were counted as continuing smokers, and all other trials were classified as low risk of bias due to loss to follow‐up. Most trials lost less than 20% of each condition. There were a small number of trials in which the proportion lost to follow‐up was over 20% and also differed between groups. Of the trials at potential risk of bias, Binnie 2007 and Villebro 2008 had high and differential losses, but since both were small trials any effect on the meta‐analysis of different assumptions would be small. Hall 2006 and Hollis 2007 both had relatively high losses but both reported that different assumptions about the smoking status of those lost to follow‐up would not be likely to alter their relative effects.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

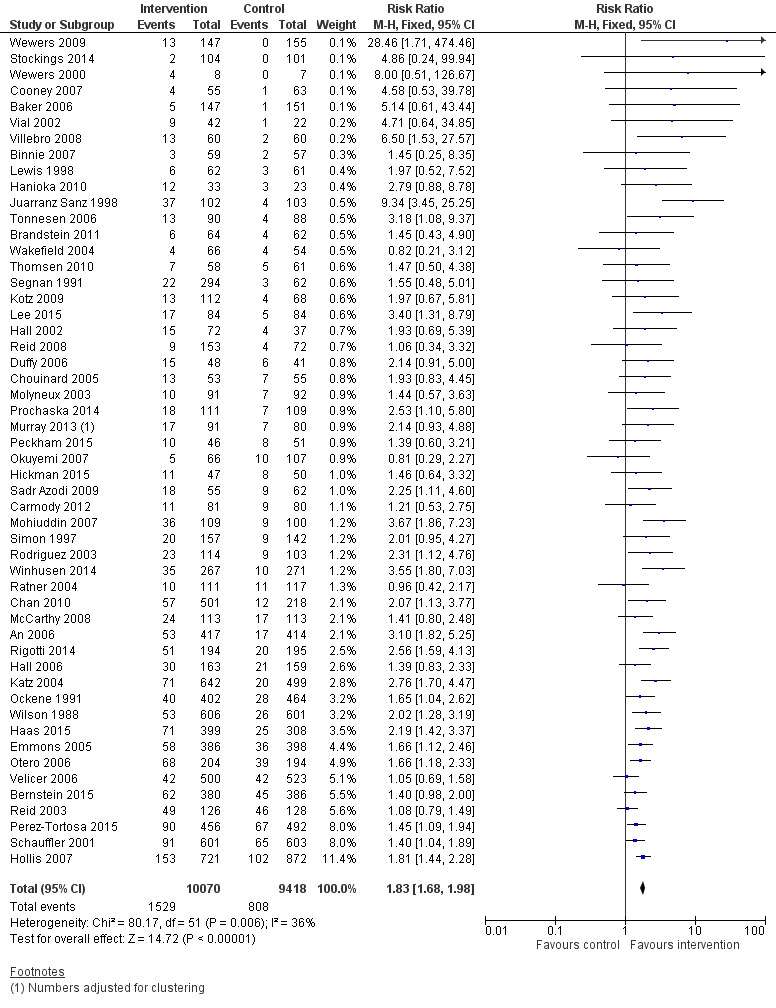

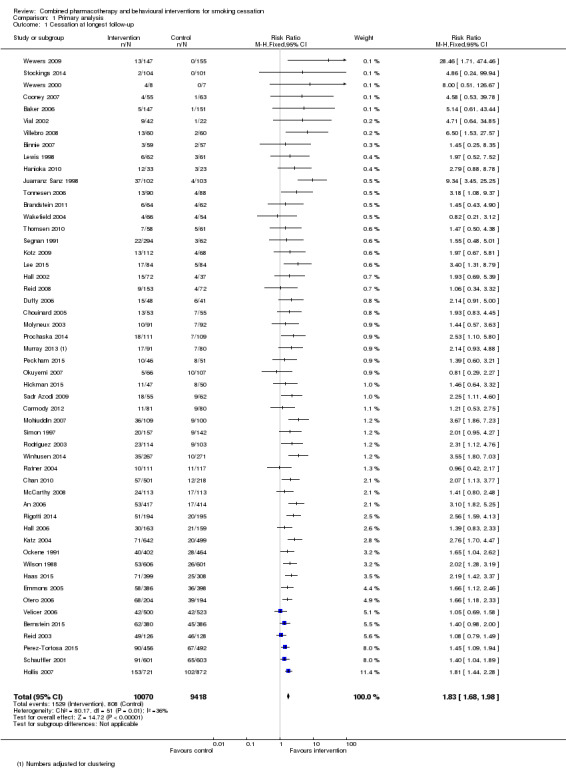

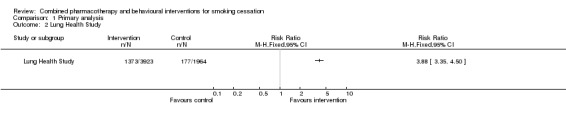

A pooled estimate combining all 53 included studies using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model had a very high level of heterogeneity (I² = 70%, data not shown). This heterogeneity was attributable to the Lung Health Study which showed a very strong intervention effect (relative risk [RR] 3.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.35 to 4.50). This study had a particularly intensive intervention; the behavioural component was a group‐based 12 session course, and nicotine gum was available without charge for six months. Removing this study from the meta‐analysis reduced heterogeneity (I² = 36%), and a benefit of intervention was still detected (RR 1.83, 95% CI 1.68 to 1.98, 19319 participants, Figure 2, Analysis 1.1, Table 1). Only three trials (Wakefield 2004; Ratner 2004; Okuyemi 2007) had lower quit rates in the intervention than the control group and all had wide confidence intervals.

2.

Combined intervention versus control. Cessation at longest follow‐up.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Primary analysis, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

There was some evidence of asymmetry in a funnel plot; there was an excess of small trials detecting larger effects, suggesting the possibility of publication or other bias. In a sensitivity analysis, removing smaller studies did not markedly decrease the pooled estimate.

Subgroup analyses

Appendix 2 lists study characteristics used for subgroup analyses for each included study. All the subgroup analyses reported below exclude the Lung Health Study.

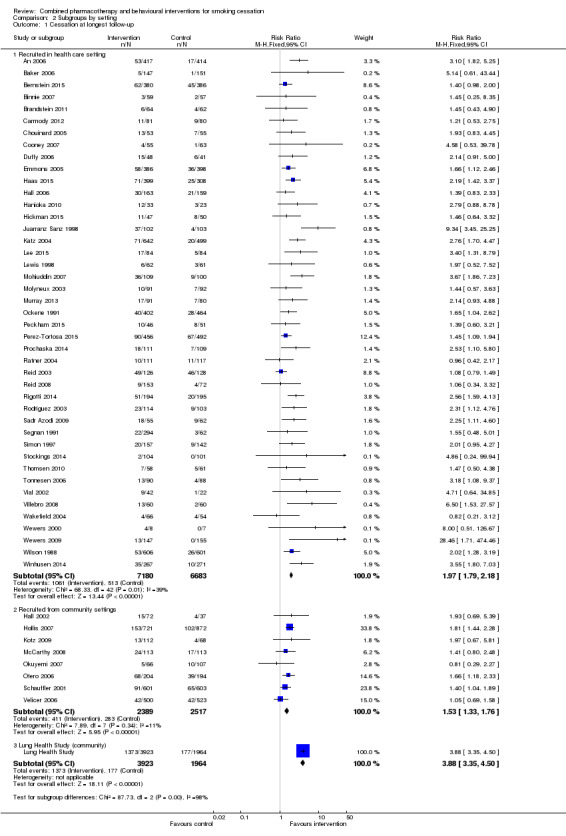

Effect of setting

The pooled estimate for trials that recruited participants in healthcare settings (RR 1.97, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.18, 43 trials, 13863 participants) was significantly higher than that for trials that recruited volunteers in other settings (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.76, 8 trials, 4906 participants) (Analysis 2.1). There were more small trials with large and significant effects in the healthcare subgroup, and a number of these had notably low quit rates in the control arms.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroups by setting, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

Effect of selection by motivation to quit

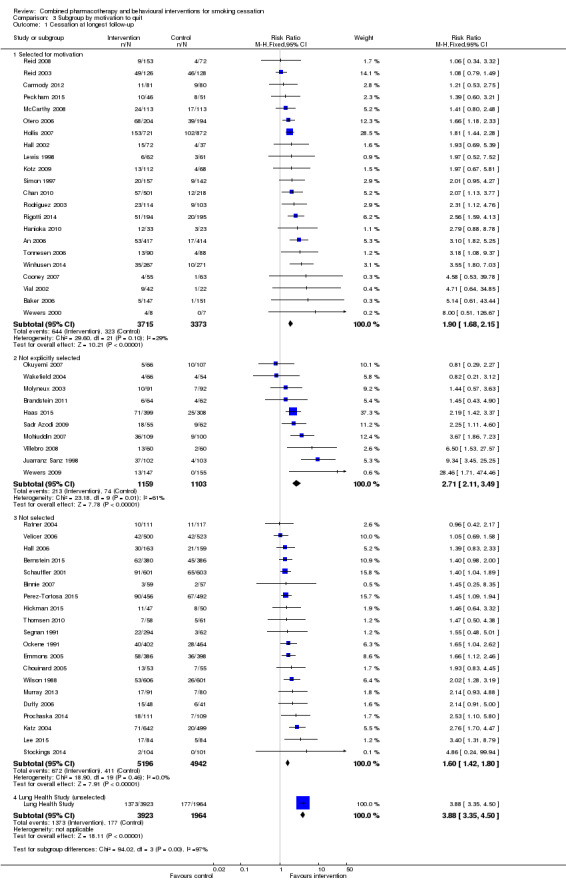

We did not detect evidence that the relative effect of the intervention differed according to whether participants were prepared to make a quit attempt or not (Analysis 3.1). The subgroup of participants selected for motivation had a slightly larger estimated effect (RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.68 to 2.15, 22 trials, 7088 participants) than the 'Not selected' subgroup (RR 1.60, 95% CI 1.42 to 1.80, 20 trials, 10138 participants); the largest effect estimate was in the subgroup of 10 trials that did not explicitly select for motivation, but that seemed unlikely to recruit unmotivated participants (RR 2.71, 95% CI 2.11 to 3.49, 2262 participants). There was also considerable heterogeneity in this subgroup (I² = 61%), for which there was no obvious explanation. In a meta‐regression, motivation to quit was not found to be an effect modifier (p = 0.09). In this update there was no longer any sign that average control group quit rates were higher in the more motivated populations.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup by motivation to quit, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

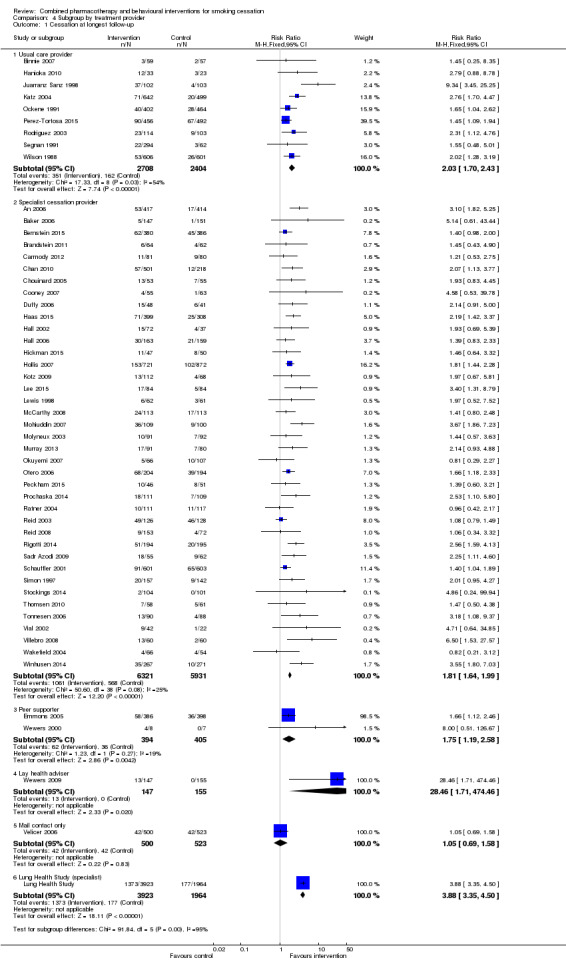

Effect of provider

The behavioural intervention was provided by specialists in cessation counselling in 39 of the trials. In nine trials, the support/counselling was given by a non specialist healthcare professional involved in usual care. In a further two trials behavioural support was provided by a peer counsellor, one of which was a very small pilot (Wewers 2000). One trial used trained lay advisers (Wewers 2009). One trial (Velicer 2006) had no person‐to‐person contact and behavioural support was provided by an 'expert system' generating individualised written materials and prerecorded telephone messages. There was no important difference between the specialist care subgroup (RR 1.81, 95% CI 1.64 to 1.99, I² = 25%, 39 trials, 12252 participants) and the subgroup where counselling was linked to usual care (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.70 to 2.43, I² = 54%, 9 trials, 5112 participants) (Analysis 4.1). In the previous version of the review there was a difference by provider that might have been attributable to confounding with take‐up of treatment and duration of contact. For this update, we did three separate exploratory meta‐regressions controlling for type of provider, take‐up of treatment and duration of contact; none was an effect modifier (p‐values 0.37, 0.08 and 0.46 respectively).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup by treatment provider, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

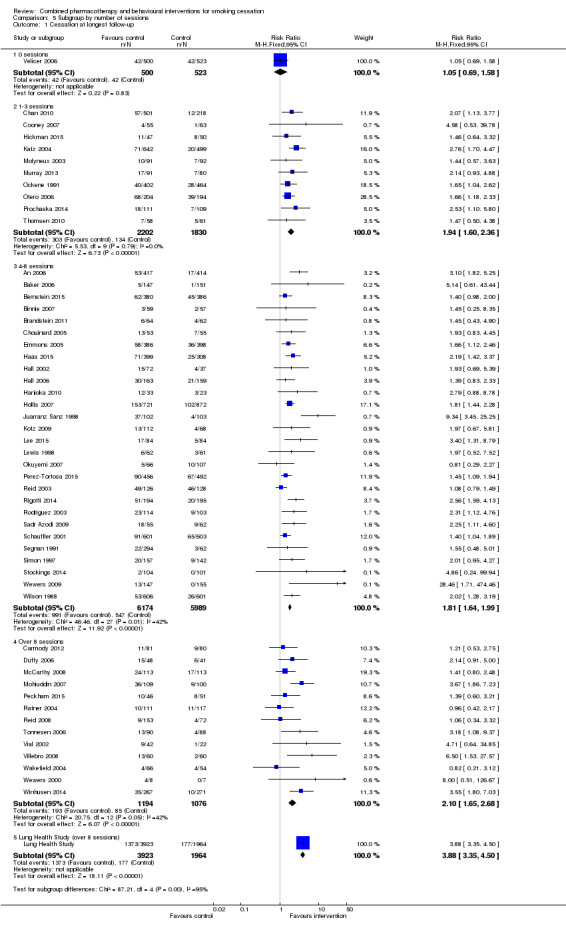

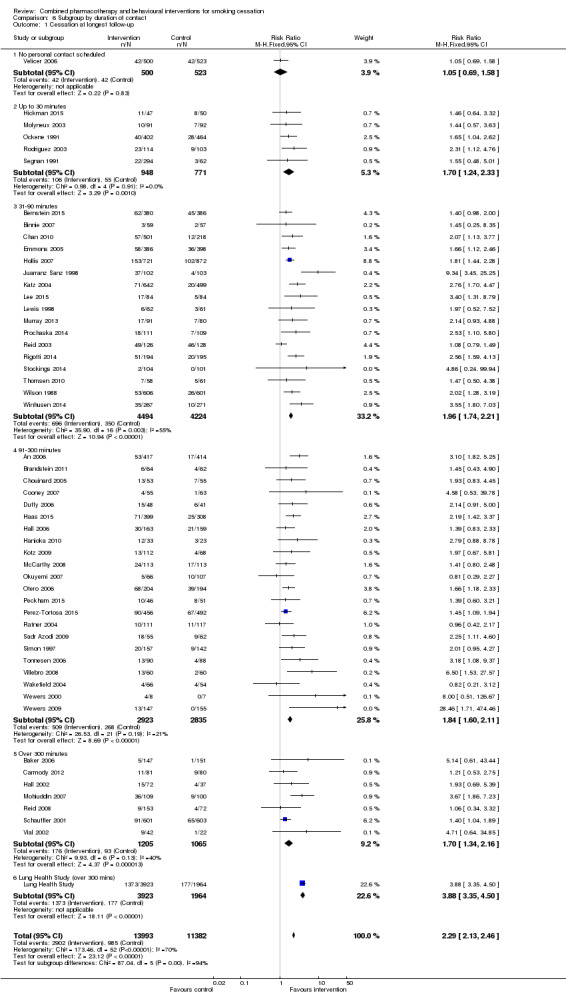

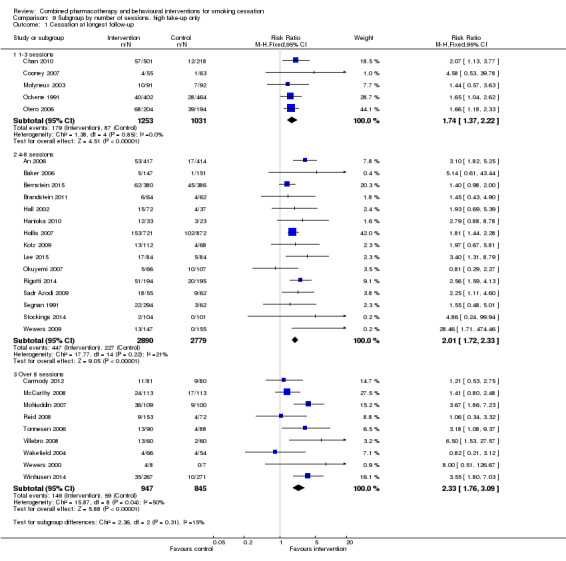

Effect of intensity

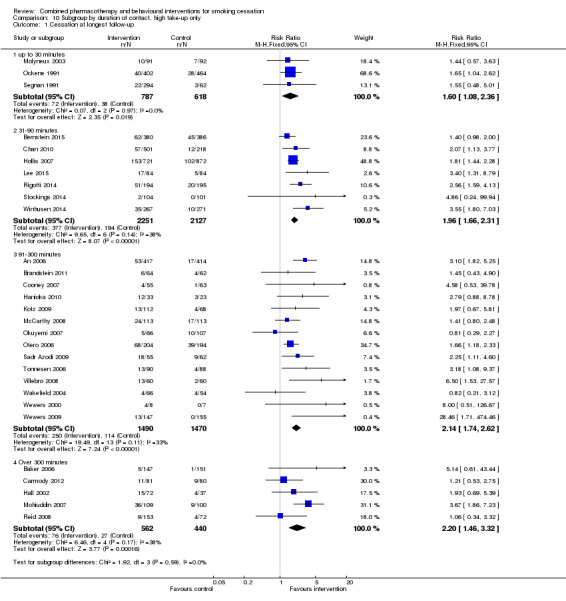

We categorised trials by intended number of sessions and planned total duration of contact. Not all interventions prescribed a fixed number or standardised length of sessions, and not all participants received all planned contacts. Unsurprisingly there was some correlation between number of sessions and duration of contact; for example, all interventions that intended to provide at least 300 minutes of contact had at least four sessions scheduled. Where there was personal contact, there was only weak evidence that studies offering more sessions had larger effects (Analysis 5.1); the subgroup of trials offering eight or more sessions had the largest estimate (RR 2.10, 95% CI 1.65 to 2.68, 13 trials, 2270 participants) but CIs overlapped. One to three and four to eight session categories had almost the same effects. There was no clear evidence that increasing the duration of personal contact increased the effect either (Analysis 6.1). Estimates for each subgroup overlapped. There was more heterogeneity in the 31 to 90 minute category (I² = 55%), partially attributable to Juarranz Sanz 1998, (RR 9.34). In an exploratory meta‐regression neither number (p = 0.85) nor duration (p = 0.46) alone or in combination (p = 0.73) were effect modifiers, nor was take‐up in combination with these (p = 0.36).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Subgroup by number of sessions, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Subgroup by duration of contact, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

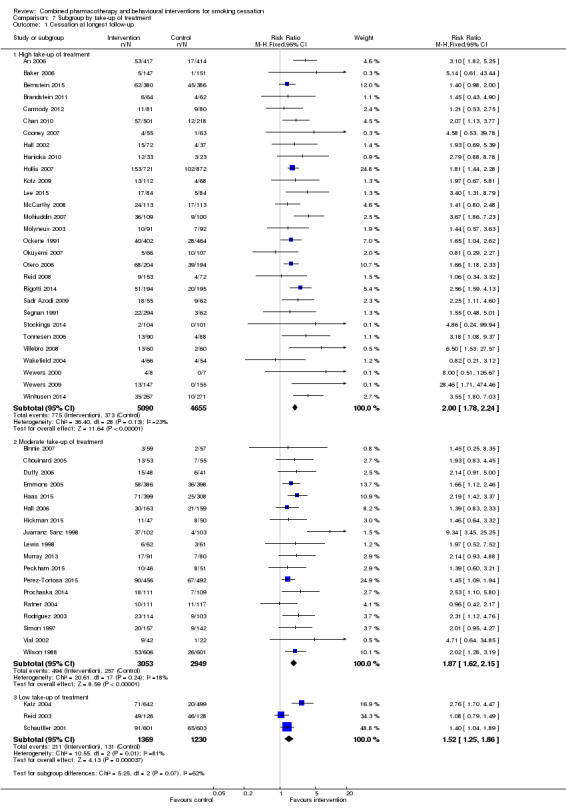

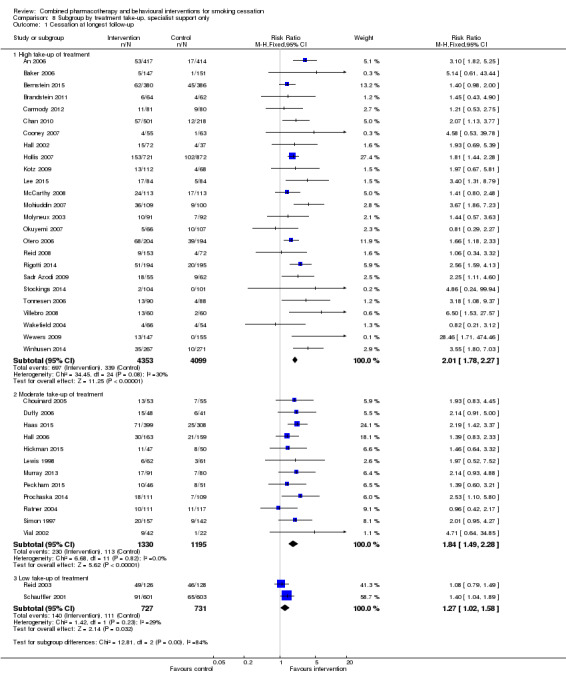

Effect of differences in treatment take‐up

Only three trials were classified as 'low take‐up of treatment' (Katz 2004; Reid 2003; Schauffler 2001), and in these the estimated effect was smaller, whilst there was little difference between the 18 that were moderate and 29 that were high (Analysis 7.1). As noted above in the analyses of intensity, there was no longer any evidence from meta‐regression of an effect of intensity even in the subgroup of 'high take‐up' trials.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Subgroup by take‐up of treatment, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

Direct tests of intensity of support

Two trials compared multiple intensities of support. In both cases the more intensive condition was compared to the control in the primary analysis. Hollis 2007 offered up to four additional telephone calls in the intensive counselling condition compared to a 30 to 40 minute motivational interview and a single follow‐up call in the moderate condition but this did not significantly increase quit rates. Higher intensity participants had on average only about 14 minutes more contact. Otero 2006 randomized to one, two, three or four weekly hour‐long sessions but pooled reported outcomes for one to two and three to four sessions. Direct comparisons of different intensities of behavioural therapy as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy are covered in a separate review (Stead 2015).

Discussion

Behavioural support and certain pharmacotherapies increase the chance of successful cessation for people trying to quit. These effects have been confirmed by reviews of trials that synthesise the results of trials of both modalities of treatment. Nicotine replacement therapy (Stead 2012), bupropion and nortriptyline (Hughes 2014) and varenicline and cytisine (Cahill 2012) increase quit rates. Group therapy (Stead 2005), individual counselling (Lancaster 2005) and telephone counselling (Stead 2013) have all been shown to be successful ways of delivering behavioural support for cessation with some support for individually tailored written self‐help materials (Hartmann‐Boyce 2014). The effects of the two treatment modalities are largely assumed to be independent, although behavioural support may influence correct use of medication. Although guidelines support combining approaches where possible, the size of effect that might be expected when both therapies are combined has not been clear.

Summary of main results

In this review of 53 trials evaluating interventions that combine pharmacotherapy with behavioural support, we found, unsurprisingly, that the combination improves quit rates compared to no treatment or a minimum intervention (see Table 1). This finding is in accord with the evidence that each type of intervention is effective when evaluated independently. A strength of the evidence from these trials is that the results are largely consistent, with little evidence of clinically important heterogeneity even though they use a wide range of approaches in many different populations and settings.

One trial demonstrated a large benefit of a multimodal therapy. The Lung Health Study, conducted in the early 1990s, achieved a cessation rate of 35% at one year in the intervention group, compared with 9% for the control. The investigators also reported sustained benefits after five years, and demonstrated reduced mortality in the intervention group. As noted above, this was a particularly intensive intervention. Participants were offered maintenance sessions, and repeat treatment was available for those failing to quit. In addition, all participants had mild airway impairment, and intervention group participants were further randomized to use a bronchodilator or placebo inhaler. This component might have increased motivation for quitting, and the relatively high rates of cessation in the control group would support this.

The pooled estimate for the remaining 52 trials (RR 1.83, 95% CI 1. 68 to 1.98) suggests that a combined intervention might typically increase cessation success by 70 to 100%. Most of the trials in this review offered one or more types of NRT, or bupropion. Based on estimates from Cochrane reviews of the effects for NRT alone (pooled estimate from 117 trials RR 1.60, 95% CI 1.53 to 1.68, Stead 2012) and bupropion alone (pooled estimate from 44 trials, RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.49 to 1.76, Hughes 2014), the additional benefit from the behavioural component might seem small. However it may be misleading to directly compare these estimates, and we did not attempt any formal statistical comparison.

There are important differences between the trials included in this review and typical pharmacotherapy studies that should be noted. Pharmacotherapy trials included in meta‐analyses typically have a placebo control, but the control group also receives identical behavioural support to the active therapy group. The intensity may vary from brief advice on correct use of pharmacotherapy and provision of self‐help materials, to multiple counselling sessions. The trial protocol may call for frequent contact with a clinical research centre, even if counselling contact is limited. Participants may have high expectations for the effect of treatment, but also the knowledge that they could be receiving placebo. In contrast, in the studies included in this review the control groups had limited support, but this typically involved advice that could be classified as a cessation intervention in other contexts. Additionally, it was generally unclear whether controls would have known the components of the active intervention and we did not attempt to assess the risk of bias from lack of blinding. In almost all the trials, intervention group participants would have known they were receiving active medication, but without the connotations of receiving a 'new' drug. Apart from the small number of included trials that were placebo‐controlled factorial studies of medication and behavioural components (Hall 2006; Tonnesen 2006; McCarthy 2008), trials in this review had pragmatic designs and the intervention typically involved an offer of treatment. Actual use of medication and take‐up of a full programme of behavioural support was not uniform across trials.

We had previously detected weak evidence for possible effect modifiers using subgroup analyses and meta‐regression. For most of the subgroups, any differential effects have become smaller and were no longer evident in meta‐regressions. We did find evidence of larger effects when trials recruited participants in health care settings. We did not find evidence that the type of provider, the motivation of the participants, the intensity of behavioural support or the amount of support taken up by participants affected the estimates of relative effects. Almost all of the interventions in this review involved multiple sessions, with some studies providing or offering more than eight sessions and as much as eight hours of contact, although the typical intensity was much lower. We no longer detected evidence from indirect comparisons that increasing contact increased quit success in the trials with the highest take‐up of treatment. Stronger evidence for a dose‐response trend might have been obscured by the multiple differences between trials. We used meta‐regression for exploratory analyses of some potential effect modifiers but the relatively small number of trials and large number of variables reduces the power of this approach. We might not have been able to identify or quantify possible moderators. For example, more intensive support might have been tested in 'hard to treat' populations but it is not clear how this might be characterised. It seems unlikely that the number of supportive contacts and their length would have absolutely no effect on outcome, but our findings suggest that the added benefit from offering more intensive support may be small. One possible explanation is that the use of pharmacotherapy attenuates the importance of the behavioural support. Healthcare providers have an important role in convincing smokers of the importance of attempting to quit and making pharmacotherapy and behavioural support available. We did not find evidence from indirect comparison that counselling by trained specialists was critical for success; in fact the estimated treatment effect was higher in the smaller group of trials where the behavioural support was provided by non specialists, although we do not think great importance should be attached to this finding.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

These trials have been undertaken in a very wide range of settings using different providers of care and amongst different populations. The populations include people with mental illness and smoking related diseases. The relative homogeneity of their results therefore supports the general applicability of the evidence. Although most of the trials provided one or more types of NRT, and a small number offered bupropion, there is no reason to suppose that the results would not apply to interventions that offered varenicline.

Using a pharmacotherapy and accessing behavioural support will increase the chance of giving up smoking, but people who smoke are unlikely to use this combination when making a quit attempt. A US survey in 2003 found that only 5.9% of those making a quit attempt in the previous year had used combined behavioural and pharmacologic treatment (Shiffman 2008). An English survey of smokers between 2006 and 2012 found that 4.8% of people attempting to quit smoking had used both a prescription pharmacotherapy and specialist behavioural support (Kotz 2014).

Quality of the evidence

The majority of studies were judged to be at low or unclear risk of bias, and only five of the included studies were judged to be at high risk of bias in one or more domains. The results of the meta‐analysis were not sensitive to the exclusion of any single trial. Excluding studies that did not use biochemical validation did not reduce the effect size. The largest study, Hollis 2007, was atypical in that all contact was telephone‐based, via a quitline (most other studies included some face‐to‐face contact); it also had a potential methodological weakness due to losses to follow‐up and lack of biochemical validation, although we did not judge these to put it at a high risk of bias. Excluding this study did not alter the effect estimate.

Potential biases in the review process

We used the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Specialised Register to identify studies. The Register includes reports of trials identified from the major bibliographic databases. There is no straightforward term for the type of intervention we were interested in, but we screened any trial report that mentioned a pharmacotherapy. It is possible that the Register does not include all relevant trial reports or that we failed to identify some. Our methods for data extraction and analysis are those used for other Cochrane reviews. The practice of imputing missing data as smoking is standard practice for primary and secondary research in smoking cessation and has the advantage that absolute cessation rates are not inflated by ignoring loss to follow‐up. Bias in the relative effect will only be introduced if misclassification differs for people who are lost from the intervention condition compared to the control. If proportionately more of those who are lost in the control group are assumed to be smokers but have in fact quit then the treatment effect would be overestimated.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this review are broadly in agreement with other reviews and guidelines (Hughes 1995; Reus 2008). US Guidelines (Fiore 2008) endorse a dose‐response relationship for total amount of contact time (up to 300 minutes) and number of sessions, as well as session length. Their meta‐analyses suggest clear trends although there were not necessarily significant differences between adjacent categories. There were however clear differences between for example 4 to 30 minutes of contact time (odds ratio (OR) 1.9, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.3) and 91 to 300 minutes (OR 3.2, 95% CI 2.3 to 4.6) (Fiore 2008 table 6.9) and between two to three treatment sessions (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.7) and over eight sessions (OR 2.3, 95% CI 2.1 to 3.0) (Fiore 2008 table 6.10). Our estimates comparing subgroups of trials classified by within trial differences in intensity show less clear evidence of a dose‐response effect, although they do not exclude there being one.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Interventions that combine pharmacotherapy and behavioural support increase smoking cessation success in a wide range of settings and populations, compared to a minimal intervention or usual care. This suggests that clinicians should encourage smokers to use both types of aid. Offering more intensive behavioural support was not shown to be associated with larger treatment effects; this may be because intensive interventions are more difficult to deliver consistently to participants.

Implications for research.

It is unlikely that further trials will alter the main findings of this review, although they may contribute to further understanding about the effects of treatment in particular settings or in populations of smokers.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 February 2016 | New search has been performed | Searches updated; twelve new studies included. |

| 16 February 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Two additional authors. No material change to pooled estimates. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2010 Review first published: Issue 10, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 November 2012 | Amended | Contact details updated. Reference to companion review 'Behavioural interventions as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation' updated to reflect publication in issue 12, 2012. |

Appendices

Appendix 1. Register Search

Version of the search used in the Cochrane Register of Studies:

1 NRT:TI,AB,KW 679

2 (nicotine NEAR (replacement OR patch* OR transdermal OR gum OR lozenge* OR sublingual OR inhaler* OR inhalator* OR oral OR nasal OR spray)):TI,AB,KW 1796

3 (Bupropion OR zyban OR wellbutrin):TI,AB,KW,MH,EMT 546

4 (varenicline OR champix OR chantix):TI,AB,KW,MH,EMT 278

5 combined modality therapy:MH,KW 213

6 ((behavio?r therapy) AND (drug therapy)):KW,MH,EMT,TI,AB 62

7 ((counsel*) AND (*drug therapy)):KW,MH,EMT,TI,AB 185

8 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 2454

9 #6 OR #7 OR #8 2509

10 #9 AND INREGISTER 2200

Appendix 2. Summary of included study characteristics

| Study | Recruitment setting/ Provider |

Selected for motivation to quit |

Sessions/ Duration |

Take‐up |

| An 2006 | Veterans Administration medical centres/ Cessation specialist (telephone counsellor) |

Selected | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Baker 2006 | Community Health Agencies (mental health patients)/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | 4‐8 / >300 mins | High |

| Bernstein 2015 | Emergency department/ Specialist (trained research assistant) |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | High |

| Binnie 2007 | Periodontology clinic/ Dental Hygienist (UC) |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | Moderate |

| Brandstein 2011 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialist (telephone counsellor) |

Not explicit | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Carmody 2012 | Alcohol treatment patients/ Cessation specialists |

Selected | >8 / >300 mins | High |

| Chan 2010 | Clinic patients and volunteers/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | 1‐3 / 31‐90 mins | High |

| Chouinard 2005 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialist (reseach nurse) |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Cooney 2007 | Substance abuse programmes/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | 1‐3 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Duffy 2006 | ENT clinic cancer patients/ Cessation specialist |

Not selected | >8 / 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Emmons 2005 | Childhood cancer survivors study/ Peer counsellor |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | Moderate |

| Haas 2015 | Primary care patients/ Cessation specialist |

Not explicit | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Hall 2002 | Community/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | 4‐8 />300 mins | High |

| Hall 2006 | Mental health clinics/ Cessation specialist |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Hanioka 2010 | Dental clinics/ Dentists and dental hygienists (UC) |

Selected | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Hickman 2015 | Psychiatric inpatients/ Cessation specialist (study staff) |

Not selected | 1‐3 / 4‐30 mins | Moderate |

| Hollis 2007 | Community/ Cessation specialist (telephone counsellor) |

Selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | High |

| Juarranz Sanz 1998 | Primary Care Clinic/ General practitioner (UC) |

Not explicit | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | Moderate |

| Katz 2004 | Primary Care Clinic/ UC (low take‐up of specialist referral) |

Not selected | 1‐3 / 31‐90 mins | Low |

| Kotz 2009 | Community/ Cessation specialist (respiratory nurse) |

Selected | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Lee 2015 | Presurgical clinic/ Nurse & specialist (telephone counsellor) |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | Moderate |

| Lewis 1998 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialist (research nurse) |

Selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | Moderate |

| Lung Health Study | Community/ Cessation specialist |

Not selected | >8 / >300 mins | High |

| McCarthy 2008 | Community/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | >8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Mohiuddin 2007 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialist |

Not explicit | >8 / >300 mins | High |

| Molyneux 2003 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialist |

Not explicit | 1‐3 / up to 30 mins | High |

| Murray 2013 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialists |

Not selected | 1‐3 31‐90 minutes | Moderate |

| Ockene 1991 | Primary Care Clinic/ Physician resident (UC) |

Not selected | 1‐3 / up to 30 mins | High |

| Okuyemi 2007 | Community/ Cessation specialist |

Not explicit | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Otero 2006 | Community/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | 1‐3 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Peckham 2015 | Mental Health Services/ Trained mental health professional |

Selected | >8 / 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Perez‐Tortosa 2015 | Primary care (diabetic patients)/ Primary care teams |

Not selected | 4‐8/ 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Prochaska 2014 | Psychiatric inpatients/ Cessation specialist |

Not selected | 1‐3/ 31‐90 mins | Moderate |

| Ratner 2004 | Preadmission clinic/ Specialist (Trained nurse) |

Not selected | >8 / 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Reid 2003 | Hospital inpatients/ Specialist (nurse counsellor) |

Selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | Low |

| Reid 2008 | Drug & alcohol dependence treatment/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | >8 / >300 mins | High |

| Rigotti 2014 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | 4‐8/ 31‐90 mins | High |

| Rodriguez 2003 | Worksite occupation health/ Occupational physician (UC) |

Selected | 4‐8 / up to 30 mins | Moderate |

| Sadr Azodi 2009 | Presurgical clinics/ Cessation specialist |

Not explicit | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Schauffler 2001 | Community/ Cessation specialist |

Not selected | 4‐8 / >300 mins | Low |

| Segnan 1991 | Primary Care Clinics/ GP (UC) |

Not selected | 4‐8 / up to 30 mins | High |

| Simon 1997 | Hospital inpatients/ Cessation specialist |

Selected | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | Moderate |

| Stockings 2014 | Psychiatric inpatients/ Cessation specialist |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | High |

| Thomsen 2010 | Surgical clinics/ Cessation specialist |

Not selected | 1‐3 / 31‐90 mins | Unclear |

| Tonnesen 2006 | Outpatient chest clinic/ Specialist (trained nurse) |

Selected | >8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Velicer 2006 | Community/ Expert system, no provider |

Not selected | No personal contact | N/A |

| Vial 2002 | Hospital inpatients/ Specialist (Pharmacist) |

Selected | >8 / >300 mins | Moderate |

| Villebro 2008 | Presurgical clinic/ Specialist (trial nurse) |

Not explicit | >8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Wakefield 2004 | Cancer treatment units/ Specialist (trial co‐ordinator) |

Not explicit | >8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Wewers 2000 | AIDS clinical trial unit/ Peer counsellor |

Selected | >8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Wewers 2009 | Primary Care Clinics/ Lay health adviser |

Not explicit | 4‐8 / 91‐300 mins | High |

| Wilson 1988 | Primary Care Clinics/ Family physician (UC) |

Not selected | 4‐8 / 31‐90 mins | Moderate |

| Winhusen 2014 | Substance use disorder clinics Cessation specialist |

Selected | >8 / 31‐90 mins | High |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Primary analysis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 52 | 19488 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.83 [1.68, 1.98] |

| 2 Lung Health Study | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Primary analysis, Outcome 2 Lung Health Study.

Comparison 2. Subgroups by setting.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Recruited in health care setting | 43 | 13863 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.97 [1.79, 2.18] |

| 1.2 Recruited from community settings | 8 | 4906 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.53 [1.33, 1.76] |

| 1.3 Lung Health Study (community) | 1 | 5887 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.88 [3.35, 4.50] |

Comparison 3. Subgroup by motivation to quit.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Selected for motivation | 22 | 7088 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.90 [1.68, 2.15] |

| 1.2 Not explicitly selected | 10 | 2262 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.71 [2.11, 3.49] |

| 1.3 Not selected | 20 | 10138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [1.42, 1.80] |

| 1.4 Lung Health Study (unselected) | 1 | 5887 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.88 [3.35, 4.50] |

Comparison 4. Subgroup by treatment provider.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Usual care provider | 9 | 5112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.70, 2.43] |

| 1.2 Specialist cessation provider | 39 | 12252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [1.64, 1.99] |

| 1.3 Peer supporter | 2 | 799 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.75 [1.19, 2.58] |

| 1.4 Lay health adviser | 1 | 302 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 28.46 [1.71, 474.46] |

| 1.5 Mail contact only | 1 | 1023 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.69, 1.58] |

| 1.6 Lung Health Study (specialist) | 1 | 5887 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.88 [3.35, 4.50] |

Comparison 5. Subgroup by number of sessions.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 0 sessions | 1 | 1023 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.69, 1.58] |

| 1.2 1‐3 sessions | 10 | 4032 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.94 [1.60, 2.36] |

| 1.3 4‐8 sessions | 28 | 12163 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [1.64, 1.99] |

| 1.4 Over 8 sessions | 13 | 2270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.10 [1.65, 2.68] |

| 1.5 Lung Health Study (over 8 sessions) | 1 | 5887 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.88 [3.35, 4.50] |

Comparison 6. Subgroup by duration of contact.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 53 | 25375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.29 [2.13, 2.46] |

| 1.1 No personal contact scheduled | 1 | 1023 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.69, 1.58] |

| 1.2 Up to 30 minutes | 5 | 1719 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.70 [1.24, 2.33] |

| 1.3 31‐90 minutes | 17 | 8718 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.96 [1.74, 2.21] |

| 1.4 91‐300 minutes | 22 | 5758 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.84 [1.60, 2.11] |

| 1.5 Over 300 minutes | 7 | 2270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.70 [1.34, 2.16] |

| 1.6 Lung Health Study (over 300 mins) | 1 | 5887 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.88 [3.35, 4.50] |

Comparison 7. Subgroup by take‐up of treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 High take‐up of treatment | 29 | 9745 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.00 [1.78, 2.24] |

| 1.2 Moderate take‐up of treatment | 18 | 6002 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.87 [1.62, 2.15] |

| 1.3 Low take‐up of treatment | 3 | 2599 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [1.25, 1.86] |

Comparison 8. Subgroup by treatment take‐up, specialist support only.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 39 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 High take‐up of treatment | 25 | 8452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [1.78, 2.27] |

| 1.2 Moderate take‐up of treatment | 12 | 2525 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.84 [1.49, 2.28] |

| 1.3 Low take‐up of treatment | 2 | 1458 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.02, 1.58] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Subgroup by treatment take‐up, specialist support only, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

Comparison 9. Subgroup by number of sessions, high take‐up only.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 1‐3 sessions | 5 | 2284 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.74 [1.37, 2.22] |

| 1.2 4‐8 sessions | 15 | 5669 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [1.72, 2.33] |

| 1.3 Over 8 sessions | 9 | 1792 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.33 [1.76, 3.09] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Subgroup by number of sessions, high take‐up only, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

Comparison 10. Subgroup by duration of contact, high take‐up only.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 up to 30 minutes | 3 | 1405 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [1.08, 2.36] |

| 1.2 31‐90 minutes | 7 | 4378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.96 [1.66, 2.31] |

| 1.3 91‐300 minutes | 14 | 2960 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.74, 2.62] |

| 1.4 Over 300 minutes | 5 | 1002 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.20 [1.46, 3.32] |

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Subgroup by duration of contact, high take‐up only, Outcome 1 Cessation at longest follow‐up.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

An 2006.

| Methods | Setting: 5 Veterans Administration medical centres, USA Recruitment: by mail, prepared to quit in next 30 days | |

| Participants | 821 smokers interested in quitting (excludes 16 deaths, 1 withdrawal); 91% M, av. age 57, av. cpd 26. 26% had > 7d abstinence in previous year, 44% ever use of bupropion, 82% ever use NRT Provider: Specialist, telephone counsellors |

|

| Interventions | 1. Mailed S‐H and standard care; opportunity for intervention during routine care and referral to individual or group cessation programmes. NRT & bupropion avail on formulary 2. As 1, plus proactive TC, modified California helpline protocol, 7 calls over 2m, relapse sensitive schedule additional calls possible, multiple quit attempts. NRT & bupropion available, could be mailed directly after screening & primary provider approval for bupropion | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12m (sustained from 6m, 7‐day PP also reported) Validation: none | |

| Notes | Pharmacotherapy was available to control group, but intervention substantially increased use; 86% vs 30% reported use at 3m. Treatment effect greater for sustained quitting than PP. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 16 deaths (10 I; 6 C) & 1 withdrawal excluded from denominators. Other losses assumed smoking |

Baker 2006.

| Methods | Setting: research clinics, Sydney & Newcastle, Australia Recruitment: referrals, mainly from community health agencies, interested in quitting | |

| Participants | 298 smokers with non acute psychotic disorder; 48% F, av. age 37, av. cpd 30, 57% schizophrenia or schizo‐affective disorder Provider: Trained cessation therapist | |

| Interventions | 1. Treatment as usual: Assessment interview & S‐H books for patient & supporter 2. As 1 plus 8 x 1‐hour sessions (weekly x 6, 8 & 10wks), motivational interviewing & CBT & nicotine patch (21 mg for 8wks incl tapering) | |

| Outcomes | Continuous abstinence at 12m (PP also reported) Validation: CO < 10 ppm | |

| Notes | One participant claiming abstinence at 12m had CO >10 ppm attributable to continued cannabis use and was classified as abstinent. Unclear if this person in the continuously abstinent or PP category | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Participants were informed that they would be randomly assigned to one of two conditions at the end of the initial assessment interview, which was achieved simply by asking them to draw a sealed envelope from a set of envelopes in which there was initially an equal distribution of treatment/control allocations at each site.' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear if envelopes were opaque and if participants kept to allocated condition |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 17% lost to follow‐up at 12m, no significant difference between groups |

Bernstein 2015.

| Methods | Setting: emergency department (ED), USA Recruitment: ED patients (both admitted and released), not selected for motivation |

|

| Participants | 778 smokers (averaging ≥ 5 cpd); 48% M, av. age 40, av. cpd 11 Provider: research assistant trained in motivational techniques & specialist counsellor |

|

| Interventions | 1. Control: self‐help brochure with quitline contact details 2. As 1 plus 10‐15 min motivational interview delivered by a research assistant trained in motivational techniques, 6 week supply of nicotine patches and gum, faxed referral to state quitline for proactive counselling, call from nurse 3 days after ED visit |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence: 7 day PP at 12 months Validation: CO only at 3 months |

|

| Notes | New for 2015 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | random plan generator |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | blinded staff member prepared opaque consecutively numbered envelopes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up 21.5% (82) I , 22% (82) C. Denominators exclude 6 deaths in I, 2 deaths & 2 duplicate enrolments in C |

Binnie 2007.

| Methods | Setting: Periodontology clinic in dental hospital, Scotland Recruitment: Patients attending for treatment invited to enrol, not selected for motivation | |

| Participants | 116 smokers (excludes 1 death, 1 withdrawal), 13% pre‐contemplators, 45% contemplators at baseline; 71% F, av. age ˜42, median 20 cpd Provider: Trained dental hygienist | |

| Interventions | 1. Usual care 2. 5As based intervention from hygienist at visits for periodontal treatment. Median visits 6‐7. Duration not specified. Free NRT (patch or gum) available, number using not specified | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 12 months (abstinent at 3, 6, 12m) Validation: Saliva cotinine < 20 ng/ml, CO at 3m & 6m. | |

| Notes | Intervention did not define number and duration of sessions; classified as 4‐8 sessions, 31‐90 minutes. Number of people who received NRT not specified. Classifed as Moderate for treatment take‐up; subgroup results not sensitive to recoding as High. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomized using minimisation method |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'The randomisation process was set up by the project statistician and was implemented independently from the recruitment process.' |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 1 death, 1 withdrawal before treatment excluded from C denominator. Lost to follow‐up: 26/59 (44%) I, 34/57 (60%) C. Losses included as smokers; exclusion would reduce point estimate, but CIs wide. |

Brandstein 2011.