Abstract

Background

The CanMEDS physician competency framework will be updated in 2025. The revision occurs during a time of disruption and transformation to society, healthcare, and medical education caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and growing acknowledgement of the impacts of colonialism, systemic discrimination, climate change, and emerging technologies on healthcare and training. To inform this revision, we sought to identify emerging concepts in the literature related to physician competencies.

Methods

Emerging concepts were defined as ideas discussed in the literature related to the roles and competencies of physicians that are absent or underrepresented in the 2015 CanMEDS framework. We conducted a literature scan, title and abstract review, and thematic analysis to identify emerging concepts. Metadata for all articles published in five medical education journals between October 1, 2018 and October 1, 2021 were extracted. Fifteen authors performed a title and abstract review to identify and label underrepresented concepts. Two authors thematically analyzed the results to identify emerging concepts. A member check was conducted.

Results

1017 of 4973 (20.5%) of the included articles discussed an emerging concept. The thematic analysis identified ten themes: Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Social Justice; Anti-racism; Physician Humanism; Data-Informed Medicine; Complex Adaptive Systems; Clinical Learning Environment; Virtual Care; Clinical Reasoning; Adaptive Expertise; and Planetary Health. All themes were endorsed by the authorship team as emerging concepts.

Conclusion

This literature scan identified ten emerging concepts to inform the 2025 revision of the CanMEDS physician competency framework. Open publication of this work will promote greater transparency in the revision process and support an ongoing dialogue on physician competence. Writing groups have been recruited to elaborate on each of the emerging concepts and how they could be further incorporated into CanMEDS 2025.

Abstract

Contexte

Le référentiel de compétences CanMEDS pour les médecins sera mis à jour en 2025. Cette révision arrive à un moment où la société, les soins de santé et l’enseignement médical sont bouleversés et en pleine mutation à cause de la pandémie de la COVID-19. On est aussi à l’heure où l’on reconnaît de plus en plus les effets du colonialisme, de la discrimination systémique, des changements climatiques et des nouvelles technologies sur les soins de santé et la formation des médecins. Pour effectuer cette révision, nous avons avons extrait de la littérature scientifique les concepts émergents se rapportant aux compétences des médecins.

Méthodes

Les concepts émergents ont été définis comme des idées ayant trait aux rôles et aux compétences des médecins qui sont débattues dans la littérature, mais qui sont absentes ou sous-représentées dans le cadre CanMEDS 2015. Nous avons réalisé une recherche documentaire, un examen des titres et des résumés, et une analyse thématique pour repérer les concepts émergents. Les métadonnées de tous les articles publiés dans cinq revues d’éducation médicale entre le 1er octobre 2018 et le 1er octobre 2021 ont été extraites. Quinze auteurs ont effectué un examen des titres et des résumés pour relever et étiqueter les concepts sous-représentés. Deux auteurs ont procédé à une analyse thématique des résultats pour dégager les concepts émergents. Une vérification a été faite par les membres de l’équipe.

Résultats

Parmi les 4973 articles dépouillés, 1017 (20,5 %) abordaient un concept émergent. Les dix thèmes suivants sont ressortis de l’analyse thématique: l’équité, la diversité, l’inclusion et la justice sociale; l’antiracisme; l’humanité du médecin; la médecine fondée sur les données; les systèmes adaptatifs complexes; l’environnement de l’apprentissage clinique; les soins virtuels; le raisonnement clinique; l’expertise adaptative; et la santé planétaire. L’ensemble de ces thèmes ont été approuvés comme concepts émergents par l’équipe de rédaction.

Conclusion

Cet examen de la littérature a permis de relever dix concepts émergents qui peuvent servir à éclairer la révision du référentiel de compétences CanMEDS pour les médecins qui aura lieu en 2025. La publication en libre accès de ce travail favorisera la transparence du processus de révision et le dialogue continu sur les compétences des médecins. Des groupes de rédaction ont été recrutés pour développer chacun des concepts émergents et pour examiner la façon dont ils pourraient être intégrés dans la version du référentiel CanMEDS de 2025.

Introduction

The CanMEDS competency framework was published in 19961 with updates in 20052 and 2015.3 It has had a major impact on medical education both in Canada4,5 and internationally,6–8 transforming curricular and program design to increase the focus on competencies that were historically not addressed adequately within medical education. Internal tracking by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada estimates that CanMEDS is now used in over 50 jurisdictions around the world by at least 12 professions, impacting millions of trainees and patients.

Given the central role that the CanMEDS physician competency framework plays within medical education, the planned 2025 revision must respond to evolving societal needs through the addition of new competencies and the removal of outdated competencies. This is particularly relevant in the current environment as healthcare and medical education continue to be disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic,9–15 technology is increasingly used to monitor health and behavior,16,17 and the impacts of colonialism,18 systemic discrimination,19 sexism,20 racism,21 and climate change22 on health are increasingly acknowledged.

The 2015 revision of the CanMEDS competency framework3 was informed by a literature scan and thematic analysis performed by a member of our authorship team (Van Melle).23 Their analysis identified and described seven emerging concepts (professional self-identity, emotion as a form of competence, systems-based practice/practice-based learning and improvement, handover, global health, social media, and financial incentives in health care). While focusing on the literature may miss concepts that have not been published,24 we sought to replicate and expand upon this work as part of a broader environmental scan that will inform the revision of the 2025 CanMEDS competency framework.

Using the 2015 methodology as a base,23 we aim to increase the rigor, inclusiveness, and transparency of the search and review process by outlining our methodology in detail, including a broad group of stakeholders in the analysis, and openly publishing our results for review and commentary from the medical education community.

Methodology

We synthesized the literature using a literature scan, title and abstract review, and generic thematic analysis25 to identify emerging concepts related to the CanMEDS roles. Given the broad-based goal of our work to identify concepts that needed to be better represented within CanMEDS, we did not find that any common literature review strategies would meet our goals. Rather, we built upon the pragmatic approach previously used by Van Melle 23 prior to the 2015 CanMEDS revision to determine the literature to be included and inform its analysis.

While the 2015 emerging concepts review was conducted by a single author,23 for this review we created a working group by soliciting nominations for members from the institutions/organizations steering the 2025 CanMEDS revisions: the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Collège des Médecins du Québec, College of Family Physicians of Canada, and Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada. For the purpose of our review, an emerging concept was defined as an idea discussed in the peer reviewed literature related to the role and competencies of physicians that is either absent or underrepresented in the 2015 CanMEDS physician competency framework.3

Article inclusion criteria

Paralleling the methods used by Van Melle in the prior review.23 we selected medical journals that would be likely to discuss emerging concepts related to CanMEDS. They included the three highest impact medical education journals by Journal Impact Factor (Academic Medicine, Medical Education, and Medical Teacher) and journals that publish content specifically related to Canadian (Canadian Medical Education Journal) and postgraduate (Journal of Graduate Medical Education) medical education. This approach differed somewhat from Van Melle’s work which was based specifically on the highest impact medical education journals,23 but we felt it was important to include journals focused specifically on Canadian and postgraduate medical education. All articles published within these journals between October 1st, 2018, and October 1st, 2021 were considered for inclusion. This three-year time period was pragmatically selected to focus on currently relevant concepts while still being feasible.

Data extraction

To facilitate the title and abstract review, metadata including the journal title, article title, and citation data were extracted from PubMed for all articles published within the review period in the selected journals. These data were imported into Zotero26 which added additional metadata including each article’s abstract. The expanded metadata were then exported from Zotero into a Google Sheet. Thoma performed a preliminary review and excluded several article types because they were unlikely to focus on emerging concepts. These articles included institutional reports, artist’s statements, corrections and errata, essay contest articles, letters to the editor, editorials focused on the journal, articles summarizing lists of other articles, and articles focused specifically on thanking reviewers and/or planning committee members. The remaining articles were arranged in a standardized format and assigned for review to individual working group members.

Article review

Each of 15 reviewers was assigned articles for review between October 10, 2021 and November 30, 2021. Thoma oriented each reviewer in a team or individual virtual meeting. Each reviewer responded to the following questions for their articles:

Does this article relate to the CanMEDS roles? (Yes/No/Maybe)

Does this article describe an emerging concept as defined above? (Yes/No/Maybe)

If yes/maybe, what is the primary role that it relates to? (Medical Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Scholar, Health Advocate, Leader, Professional)

Are there any additional CanMEDS roles that it relates to? (Medical Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Scholar, Health Advocate, Leader, Professional)

Please describe the emerging concept as a brief title. (free text)

If necessary, provide a brief description of the emerging concept. (free text)

Is this a concept (a) absent from or (b) underrepresented in the 2015 iteration of CanMEDS? (dropdown with A and B options)

Is this an exemplar article that summarizes the emerging concept well? (Yes, No, Maybe)

If the response to questions 1 or 2 was ‘no,’ questions 3-8 were not answered and these articles were excluded from further review. Articles that the reviewer tagged as ‘maybe’ for question 1 or 2 were reviewed by a second reviewer (Thoma) and included or excluded based upon their responses.

Thematic analysis

After the title and abstract reviews were completed, the remaining articles were amalgamated into a single Google Sheet. Two authors (Thoma and Van Melle) then conducted a thematic analysis25,27 of the reviewers’ responses to question 5, the emerging concept identified by the reviewing author and, when necessary, the article’s metadata. This analysis followed the phases of thematic analysis.28 Following a preliminary review (familiarization), we developed and collaboratively refined a codebook. We then coded all the articles with refinements to the codebook when necessary (coding). Once all articles were coded, Thoma developed and defined a preliminary set of themes incorporating the codes (searching for themes). The resulting thematic framework was reviewed, modified, and endorsed by Van Melle with modifications to clarify and define each theme (defining and naming themes). It was then presented to the full working group for feedback and revision as the first part of the member check (reviewing themes). In follow-up, a survey of the working group members was conducted via a Google Forms survey as the second part of the member check (reviewing themes). The survey requested endorsement for each of the themes from the review team and asked how the themes could be further refined. These suggestions were incorporated into the analysis.

Throughout the analysis, Thoma and Van Melle considered their positionality. Thoma is a practicing emergency and trauma physician who conducts medical education research with a focus on technology-enhanced medical education (simulation, online educational resources, and learning analytics). Van Melle is a PhD education scientist with expertise in program evaluation and change, particularly in competency-based medical education contexts. Both are contracted by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada to provide advice regarding educational developments in the training of specialty physicians across Canada. We attempted to mitigate the biases introduced by their positionality through member checks conducted both in a virtual meeting and a follow-up survey with an authorship group that contained perspectives from a range of medical specialties and CanMEDS stakeholders.

Triangulation

Acknowledging that publication delays and the gatekeeping of medical journals could have prevented some emerging concepts from appearing in the literature24, we cross-referenced our results with the findings of an online search and thematic analysis that was conducted in parallel to our literature scan. While the full methodology and results of this search and analysis have not been reported and were not a formal part of our study, one of our authors (Snell) searched the grey literature using the Google search engine with multiple key words with the goal of identifying and thematically analyzing emerging concepts. We triangulated our results by cross-referencing the findings of this analysis with our own to identify emerging concepts from the grey literature that were not found in our scan.

Expert review

Following the completion of the described analysis, Thoma asked the working group members and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada Clinician Educators to nominate experts for each of the ten emerging concepts. Writing groups were formed, combining members of the authorship team for this manuscript and the experts that were nominated in the survey. Each writing group met 2-4 times from March 2022 through July 2022 with the goal of writing a brief manuscript defining each concept, outlining how it is represented in the 2015 CanMEDS physician competency framework,3 and proposing changes for CanMEDS 2025. The changes proposed by the writing groups to the name of each concept were emailed to the working group for review and approval.

Results

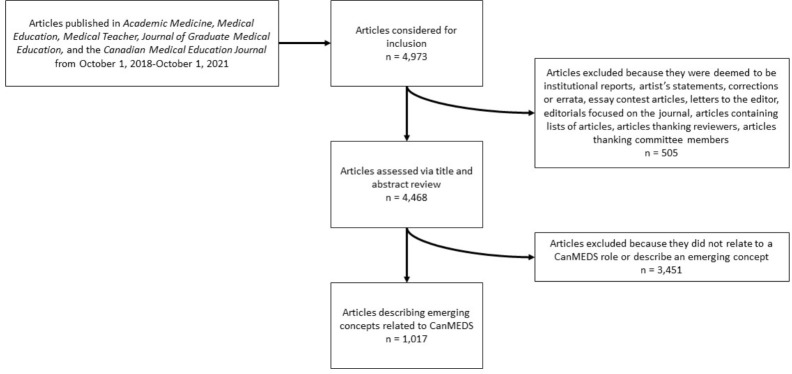

As outlined in Figure 1, 4973 articles were published in the included journals during the period of interest. 505 of these articles were excluded in the preliminary review because they were deemed to be institutional reports, artist’s statements, corrections or errata, essay contest articles, letters to the editor, editorials focused on the journal, articles containing lists of articles, articles thanking reviewers, or articles thanking committee members. 4468 articles underwent title and abstract review. Each of the reviewers reviewed between 142 and 385 articles (mean = 298 articles). Following both rounds of review, 1017 of the remaining 4468 articles (22.8%) were included in the thematic analysis.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram outlining the articles considered within the literature scan and the title/abstract review.

Our qualitative analysis incorporated 81 codes into nine preliminary themes. Based upon feedback at the large group meeting with the author reviewers, one additional theme was created by splitting one of the themes (Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) into two (1. Physician Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and 2. Patient Access, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice). All working group members completed the member check survey. Modifications in wording were made to several of the theme titles based upon survey feedback, but no themes were removed or amalgamated.

Ten working group members and nine clinician educators completed the survey nominating experts to participate in a writing group on each of the emerging concepts. A writing group was formed for each concept and tasked with describing how it could be more effectively integrated into CanMEDS. The two writing groups focused on patient and physician equity, diversity, and inclusion determined that this concept was too broad for a single manuscript. However, rather than splitting it into patient and physician focused manuscripts as was done in the initial analysis, they recommended dividing it into one manuscript focused on anti-racism and a second manuscript focused on equity, diversity, inclusion, and social justice. The writing groups were modified in keeping with this recommendation which was subsequently endorsed by our authorship team. The results of the thematic analysis following modification by the writing groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thematic analysis of emerging concepts in medical education that should be considered for incorporation into CanMEDS 2025.

| # | Theme | Incorporated Codes | Theme Descriptions | Working Group members who endorsed the concept N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | Physician Equity, Diversity, Inclusion29 | Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, Gender, Indigenous, Immigrant, Bias, Microaggressions, Social Accountability | Competencies related to equity, diversity, inclusion within the physician population. | 17/17 (100%) |

| 1* | Patient Access, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice29 | Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, Gender, Indigenous, Immigrant, Incarcerated, Social Determinants of Health, Microaggressions, Bias, Social Accountability | Competencies related to the access, equity, inclusion, and social justice within the care provided to patients | 17/17 (100%) |

| 2 | Anti-racism30 | Anti-racism | Competencies related to recognizing the existence of racism and actively seeking to identify, prevent, reduce, and remove the racially inequitable outcomes and power imbalances between groups and the structures that sustain these inequities. | N/A* |

| 3 | Physician Humanism31 | Physician Wellness, Family, Empathy, Compassion, Arts and Humanities, Professional Identity Formation, Spirituality | Competencies related to the experience of humanism in physician personal identity, activities, and interactions. | 15/17 (88.2%) |

| 4 | Data-Informed Medicine32 | Big Data, Machine Learning, Artificial Intelligence, Electronic Health Record, Technology Literacy, Cybersecurity | Competencies related to the role, collection, and analysis of information in our educational and clinical work. | 15/17 (88.2%) |

| 5 | Complex Adaptive Systems33 | Complex Systems, System Change, Leadership Skills, Co-production, Culture, Design, Health Systems Science, Globalization, Quality Improvement | Competencies related to the navigation of complexity within both patient care and healthcare institutions. | 17/17 (100%) |

| 6 | Clinical Learning Environment34 | Learning Environment, Psychological Safety, Sexual Harassment, Culture, Hidden Curriculum | Competencies related to clinical learning environments including their impact on physicians and how physicians impact them. | 14/17 (82.4%) |

| 7 | Virtual Care35 | Virtual Care, Digital and Online Education, Virtual Assessment, Social Media, Virtual Reality, Apps | Competencies related to teaching, assessing, and providing patient care in virtual environments. | 17/17 (100%) |

| 8 | Clinical Reasoning36 | Medical Error, Values-Based Medicine, Patient-Centered Care, Motivational Interviewing, Medical Decision Making, Efficiency (time and cost), Cognitive Load Theory, Cognitive Flow, Dealing with Uncertainty, Trauma-Informed Care, Humanistic Medicine | Competencies related to how physicians think and function effectively in providing patient care. | 15/17 (88.2%) |

| 9 | Adaptive Expertise37 | Adaptive Expertise, Humility, Growth Mindset, Collective Competence, Coaching, Mentorship and Sponsorship, Continuing Professional Development, App-based Decision Support, Reflective Practice, Transformative Learning, Practical Wisdom | Competencies related to the evolution, refinement, and development of the tools and skills required to practice effectively in a rapidly changing world. | 15/17 (88.2%) |

| 10 | Planetary Health38 | Climate Change, Sustainable Healthcare | Competencies related to the impact of climate and the environment on patients, and of patient care activities on climate and the environment. | 14/17 (82.4%) |

The writing groups proposed the merger of the first two concepts into one titled ‘Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Social Justice’, and the creation of a separate concept focused specifically on anti-racism. This was approved with the unanimous consent, but not formally voted on in the member check.

Table 1 also includes a description of the potential physician competencies discussed within each theme and the proportion of working group members who endorsed each theme as an emerging concept during the first member check. At least fourteen (82.4%) of the 17 working group members endorsed each of the themes as an emerging concept. There were a variety of suggestions provided for why a member did not endorse a theme such as not identifying the theme as novel, not seeing how it could relate to a CanMEDS competency, or preferring themes be split or expanded. The grey literature search did not identify any additional emerging concepts.

Six of the 10 writing groups proposed changes to the title of their concept to describe it more accurately. The changes to the names and definitions of the emerging concepts, as well as the addition of the anti-racism concept, were approved by the authorship group with unanimous consent.

Discussion

Our study identified ten emerging concepts in the medical literature that could be incorporated into the physician competencies described by CanMEDS 2025.29–38 Each of these concepts is quite broad in scope, with most encompassing several trends or issues currently being discussed in the medical education literature. Several themes within our results are notable as they mirror current themes of prominence in the broader social, economic, political, and environmental discourse over the past three years.

Themes relating to access, equity, diversity, inclusion, social justice, and anti-racism29,30 were prevalent in the analysis. This large theme was ultimately separated into two themes, with one focused specifically on anti-racism.30 The prominence of these themes in the medical literature parallels the acknowledgement of the negative impact of systemic discrimination in the public discourse.19 Given the Canadian context of this review, the central importance of Indigenous health in the Canadian healthcare system,39 and the seven calls to action related to health published in the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada,40 it is notable that a separate theme focused on Indigenous health did not emerge independently. We suspect this is due to both the international focus of the included journals (only the Canadian Medical Education Journal focused more closely on Canadian medical education) as well as the frequent coding of many relevant constructs under the themes of equity, diversity, inclusion, social justice,29 and anti-racism.30 Notably, proposed competencies related to Indigenous health are central to both manuscripts further describing these themes.29,30

The presence of the ‘Planetary Health’ theme38 is unsurprising given the scientific consensus building on the drastic impacts of climate change on health.22 Notably, physicians and medical trainees have had a prominent voice in education and advocacy relating to the impacts of climate change on the health and wellbeing of the population.41–43 However, some authors were concerned that it would be challenging to mobilize this construct within a competency framework relevant to individual physicians.

There was broad consensus regarding the need for additional competencies related to the use of data and technology.32,35 Beyond the growing dialogue surrounding precision medicine, the codes consolidated into the ‘Virtual Care’ and ‘Data-Informed Medicine’ themes parallel growing societal awareness of the pervasiveness of emerging technologies16,17 and the need for personal and health data to be used ethically and securely.44

The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic was seen in numerous themes. In particular, the ‘Virtual Care’ theme35 relates strongly to virtual education and virtual healthcare, concepts that were substantially impacted by travel and gathering restrictions during the pandemic.15,45 Other concepts that were likely influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic included ‘Complex Adaptive Systems’33,46 due to its complex ongoing impacts on the healthcare system and ‘Physician Humanism’31,47 due to its strain on physicians and other healthcare providers.

The ‘Adaptive Expertise’37 and ‘Clinical Reasoning’36 themes acknowledge how rapidly changes are occurring within the complex realm of clinical practice.48 While there are competencies that enable physicians to evolve their practices to meet these challenges, it will also be important to consider how evolving physician competencies are integrated into CanMEDS in a timely manner. While performing revisions approximately once per decade has served CanMEDS well in the past, it is conceivable that new competencies will emerge between the publication of this manuscript and the implementation of CanMEDS 2025. Consideration should be given to transitioning CanMEDS from periodic updates to an ongoing iterative process. While this may be logistically challenging for residency training programs, it is in keeping with modern processes for the continuous updating of guidelines by organizations like the American Heart Association and could allow for smaller, more frequent updates.49

Further work has been conducted to describe how each of the emerging concepts can be incorporated into CanMEDS 2025. Writing groups have drafted manuscripts that define each concept, outlined how it was represented in CanMEDS 2015, and proposed how it could be incorporated into CanMEDS 2025.29–38 This work has been published along with this paper in this special issue of the Canadian Medical Education Journal and will inform the CanMEDS 2025 Expert Working Groups responsible for updating the CanMEDS physician competency framework. The open publication of these emerging concepts should provide Canadian and international medical communities with an opportunity to discuss and comment on this work.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this review rests in the detailed, transparent methods and the broad engagement of stakeholder organizations. While a related literature review was conducted prior to the CanMEDS 2015 revision,23 its methodology was not described in detail or peer reviewed. We have improved on this work by publishing a detailed methodology and by putting our work through the peer review process. Additionally, the article review was conducted by a broader group oof stakeholders (including representatives from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Collège des Médecins du Québec, College of Family Physicians of Canada, and Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada). The diversity of our authorship team decreases the chance that important concepts were missed.

This review had several limitations. First, we restricted the scope of our review by limiting the inclusion period to three years, the source to five journals, and specific article types. We see these limitations as intentional, pragmatic decisions that we made to maintain feasibility while identifying emerging concepts. Despite the potential to have missed some themes, it is reassuring that triangulation with the grey literature scan did not identify any additional concepts. Second, with numerous reviewers participating in the literature scan, it was difficult to ensure consistency in emerging concept criteria and labelling. Further, most abstract reviews were done independently unless flagged for additional review. We anticipate that the member checks mitigated the impact of this challenge on the results. Finally, consolidating the numerous identified concepts into themes was difficult. Our analysis could be criticized for aggregating a broad number of codes within some of the themes. Some of the working group participants felt that some themes were either not emerging concepts or were overly broad. This challenge is well-represented by the evolution of the themes related to equity, diversity, and inclusion throughout the phases of the study. This said, a large majority (≥82.4% of working group members) felt that each theme represented an important emerging concept that deserved further exploration.

Conclusion

This review and analysis identified ten emerging concepts that should be considered for incorporation into the 2025 CanMEDS physician competency framework. The results of this work are elaborated upon in this special issue, which contains an expanded article on each concept along with suggestions for how it could be incorporated into CanMEDS 2025.29–38. We hope that in addition to informing the revision of CanMEDS, the open publication of this work will create greater transparency around the revision process while facilitating an early dialogue in the academic literature on physician competence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Megan McComb and Ms. Cynthia Abbott for planning and logistical support.

Funding Statement

Funding: This project was completed with logistical support from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Conflicts of Interest

Thoma, Atkinson, Hall, Frank, Snell, Anderson, and Van Melle have received stipends from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Thoma also reports payments for teaching, research, and administrative work from the University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine and teaching honoraria from various institutions within the past 3 years (Harvard Medical School, the New England Journal of Medicine, the University of Cincinnati Children's Hospital, and NYC Health + Hospitals). Samson receives stipends from the Collège des médecins du Québec and the Université de Montréal. Giuliani has an unrelated conflict-of-interest with AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb. Chan reports honoraria from McMaster University for her education research work with the McMaster Education Research, Innovation, and Theory (MERIT) group and administrative stipend for her role of Associate Dean via the McMaster Faculty of Health Sciences Office of Continuing Professional Development. Chan also reports teaching honoraria from various institutions within the past three years (UBC, UNBC, Baylor College of Medicine, Harvard University, NOSM, Catholic University of Korea, Taiwan Veteran’s General Hospital, Prince of Songkla University). Waters reports honoraria and salary support for academic contributions from McMaster University. Chan and Waters have received educational research grant funding from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Fowler is a paid employee of the College of Family Physicians of Canada. Tourian receives a salary from McGill University for his administrative work as the Assistant Dean of Postgraduate Medical Education. Constantin received a stipend from the Collège des médecins du Québec as an expert advisor; she also receives a salary from McGill University for her administrative and education work within Postgraduate Medical Education as well as within the Office of International Affairs. Karwowska receives a stipend from the Association of Faculties of medicine of Canada.

References

- 1.Frank J. The CanMEDS Project: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada moves medical education into the 21st Century. In Ottawa, ON: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2004; p. 8. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271702100_A_history_of_CanMEDS_-_chapter_from_Royal_College_of_Physicians_of_Canada_75th_Anniversary_history [Accessed Feb 11, 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank J. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework. 2005. Available from: http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/CanMEDS2005/CanMEDS2005_e.pdf [Accessed Feb 1, 2022].

- 3.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J Editors. CanMEDs 2015 Physician Competency Framework. 2015. p. 1-30. Available from: http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/canmeds/resources/publications [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw E, Oandasan I, Fowler N, editors. CanMEDS-FM 2017: A competency framework for family physicians across the continuum. Mississauga, ON: The College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterkin A, Roberts M, Kavanagh L, Havey T. Narrative means to professional ends: new strategies for teaching CanMEDS roles in Canadian medical schools. Can Fam Physician. 2012. Oct 1;58(10):e563-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shadid AM, Bin Abdulrahman AK, Bin Dahmash A, et al. SaudiMEDs and CanMEDs frameworks: similarities and differences. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:273-8. 10.2147/AMEP.S191705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koster AS, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Woerdenbag HJ, et al. Alignment of CanMEDS-based undergraduate and postgraduate pharmacy curricula in The Netherlands. Pharmacy. 2020. Sep;8(3):117. 10.3390/pharmacy8030117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank JR, Langer B. Collaboration, communication, management, and advocacy: teaching surgeons new skills through the CanMEDS Project. World J Surg. 2003. Aug 1;27(8):972-8. 10.1007/s00268-003-7102-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abi-Rafeh J, Safran T, Azzi AJ. COVID-19 pandemic and medical education: a medical student's perspective. Can Med Educ J. 2020. Sep;11(5):e118-20. 10.36834/cmej.70242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown A, Kassam A, Paget M, Blades K, Mercia M, Kachra R. Exploring the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: an international cross-sectional study of medical learners. Can Med Educ J. 2021. Jun;12(3):28-43. 10.36834/cmej.71149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherak SJ, Brown A, Kachra R, et al. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical learner wellness: a needs assessment for the development of learner wellness interventions. Can Med Educ J. 2021. Jun;12(3):54-69. 10.36834/cmej.70995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giuliani M, Samoil D, Agarwal A, et al. Exploring the perceived educational impact of COVID-19 on postgraduate training in oncology: impact of self-determination and resilience. Can Med Educ J. 2021. Feb;12(1):e180-1. 10.36834/cmej.70529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li HOY, Bailey AMJ. Medical education amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: New Perspectives for the Future. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2020. Nov;95(11):e11-2. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thoma B, Monteiro S, Pardhan A, Waters H, Chan T. Replacing high-stakes summative examinations with graduated medical licensure in Canada. CMAJ. 2022. Feb 7;194(5):E168-70. 10.1503/cmaj.211816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall AK, Nousiainen MT, Campisi P, et al. Training disrupted: Practical tips for supporting competency-based medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Teach. 2020. Jul 2;42(7):756-61. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1766669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinh-Le C, Chuang R, Chokshi S, Mann D. Wearable health technology and electronic health record integration: scoping review and future directions. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2019. Sep 11;7(9):e12861. 10.2196/12861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gostin LO, Halabi SF, Wilson K. Health data and privacy in the digital era. JAMA. 2018. Jul 17;320(3):233-4. 10.1001/jama.2018.8374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Social determinants of health inequities in Indigenous Canadians through a life course approach to Colonialism and the residential school system. Health Equity. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/heq.2019.0041 [Accessed on Feb 18, 2022]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Cuevas AG, Ong AD, Carvalho K, et al. Discrimination and systemic inflammation: a critical review and synthesis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020. Oct 1;89:465-79. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Homan P. structural sexism and health in the United States: a new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. Am Sociol Rev. 2019. Jun 1;84(3):486-516. 10.1177/0003122419848723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105-25. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers SS. Planetary health: protecting human health on a rapidly changing planet. The Lancet. 2017. Dec 23;390(10114):2860-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32846-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Melle E. New and emerging concepts as related to the CanMEDS roles: overview. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. Available from: https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/documents/canmeds/emerging-concepts-e.pdf [ Accessed on Feb 1, 2022].

- 24.Pappas C, Williams I. Grey literature: its emerging importance. J Hosp Librariansh. 2011. Jul;11(3):228-34. 10.1080/15323269.2011.587100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maguire M, Delahunt B. Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. Irel J High Educ . 2017. Oct 31;9(3). Available from: https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335 [Accessed on Feb 17, 2022] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zotero . Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media; 2022. Available from: https://www.zotero.org/

- 27.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019. Aug 8;11(4):589-97. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006. Jan 1;3(2):77-101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnabe C, Osei-Tutu K, Maniate JM,et al. Equity, diversity, inclusion, and social justice in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osei-Tutu K, Duchesne N, Barnabe C, et al. Anti-racism in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waters HM, Oswald A, Constantin E, Thoma B, Dagnone JD. Physician humanism in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thoma B, Paprica PA, Kaul P, Cheung WJ, Hall AK, Afflect E. Data-informed medicine in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Aerde J, Gomes MM, Giuliani M, Thoma B, Lieff S. Complex Adaptive systems in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoma B, Paprica PA, Kaul P, Cheung WJ, Hall AK, Affleck E. Data-informed medicine in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Ed J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stovel RG, Dubois D, Chan TM, Snell L, Thoma B, Ho K. Virtual care in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023; 10.36834/cmej.75439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young M, Szulewski A, Anderson R, Thoma B, Monteiro S. Clinical reasoning in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023; 10.36834/cmej.75843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cupido N, Fowler N, Sonnenberg LKet al. Adaptive expertise in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green S, Labine N, Luo OD, et al. Planetary health in CanMEDS 2025. Can Med Educ J. 2023. 10.36834/cmej.75438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenwood M, Leeuw S de, Lindsay N. Challenges in health equity for Indigenous peoples in Canada. The Lancet. 2018. Apr 28;391(10131):1645-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30177-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada . Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Winnipeg, Manitoba; 2015. Available from: https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf [Accessed on Feb 16, 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solomon CG, LaRocque RC. Climate Change-A Health Emergency. N Engl J Med. 2019. Jan 17;380(3):209-11. 10.1056/NEJMp1817067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walpole SC, Barna S, Richardson J, Rother HA. Sustainable healthcare education: integrating planetary health into clinical education. Lancet Planet Health. 2019. Jan;3(1):e6-7. 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30246-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hackett F, Got T, Kitching GT, MacQueen K, Cohen A. Training Canadian doctors for the health challenges of climate change. Lancet Planet Health. 2020. Jan;4(1):e2-3. 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30242-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denecke K, Gabarron E, Petersen C, Merolli M. Defining participatory health informatics-a scoping review. Inform Health Soc Care. 2021. Sep 2;46(3):234-43. 10.1080/17538157.2021.1883028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10231):1180-1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uhl-Bien M. Complexity and COVID-19: leadership and followership in a complex world. J Manag Stud. 2021;58(5):1400-4. 10.1111/joms.12696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, McAlister RP, Duncan J. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS ONE. 2020. Aug 6;15(8):e237301. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mylopoulos M, Kulasegaram K, Woods NN. Developing the experts we need: fostering adaptive expertise through education. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(3):674-7. 10.1111/jep.12905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merchant RM, Topjian AA, Panchal AR, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020. Oct 20;142(16_suppl_2):S337-57. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]