Abstract

Spirituality and religiousness are important factors for adolescents wellbeing. Little is known about the mechanisms underlying the positive relationship between spirituality as well as religiousness and subjective wellbeing. This study aimed to verify, whether, in a sample of Chilean students, religiousness is indirectly related to hope through spiritual experiences, and whether spiritual experiences are indirectly related to subjective wellbeing via hope. The sample consisted of 177 Chilean students and the following measures were applied: the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale, the Herth Hope Index, the Satisfaction With Life Scale, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, and one item measuring the frequencies of prayer and Mass attendance. According to obtained results religiousness was indirectly, positively related to hope through spiritual experiences. In turn spiritual experiences were indirectly, positively related to subjective wellbeing through hope. Conducted research confirmed the beneficial role of religious practices, spiritual experiences, and hope for Chilean students' subjective wellbeing and the presence of mechanisms underlying the relationships between religiousness as well as spirituality and subjective wellbeing.

Keywords: Spirituality, Religiousness, Religious practices, Hope, Subjective wellbeing

Introduction

In recent years, a growing body of research has focused on the religious and spiritual factors that influence health and wellbeing (Cohen & Koenig, 2003; Hill & Pargament, 2008; Jordan et al., 2014; Park, 2007; Seybold & Hill, 2001; Siegel et al., 2001) in an attempt to explain both the positive and negative impacts of religiousness and spirituality on physical, social, and psychological functioning (Chatters, 2000; Weber & Pargament, 2014). Researchers have attempted to identify and describe the mechanisms underlying the relationship between spirituality/religiousness and wellbeing by examining genetic, biological, social, and psychological factors (Baetz & Toews, 2009). Mostly in the role of potential mediators of spirituality/religiousness and wellbeing relationships have verified psychosocial variables, such as purpose and meaning in life (Aghababaei & Błachnio, 2014; Chamberlain & Zika, 1988; Park et al., 2008; Steger & Frazier, 2005; Vilchensky & Kravetz, 2005; Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014; Yoon et al., 2015), social support (Holt et al., 2005; Nooney & Woodrum, 2002; Prado et al., 2004), coping (Canada et al., 2006; Holt et al., 2005; Prado et al., 2004), religious coping (Fabricatore et al., 2004; Nooney & Woodrum, 2002; Schaefer & Gorsuch, 1991; Watlington & Murphy, 2006), optimism (Aglozo et al., 2021; Cheadle & Schetter, 2018; Kvande et al., 2015; Warren et al., 2015), and forgiveness (Lawler-Row, 2010).

Relatively, less is known about the role of hope in the relationship between religious or spiritual involvement, and subjective wellbeing. Various studies conducted upon students in different countries have indicated that spirituality and religiousness can indirectly improve wellbeing through hope (Chang et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2013; Nell & Rothmann, 2018; Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014). The aim of the study was to verify, whether in a sample of Chilean students religiousness is indirectly related to hope through spiritual experiences, and, whether spiritual experiences is indirectly related to subjective wellbeing through hope.

Chile is a historically Catholic country. At present, the majority of Chileans self-identify as Roman Catholic. Furthermore, 70% of Chileans self-identify as being “highly religious,” meaning that religion plays a significant role in their lives (Vázquez & Páez, 2011).

Relationships between religiousness and spirituality as well as subjective wellbeing depend not only on the measures used to verify them (Poloma & Pendleton, 1990), but also on socioeconomic and cultural factors (Diener et al., 2011; Lun & Bond, 2013). For example, in religious nations, religious individuals have higher rates of subjective wellbeing, although, non-religious people have higher rates of subjective wellbeing in non-religious nations (Diener et al., 2011; Graham & Crown, 2014; Stavrova et al., 2013). Also, in national cultures where socialization of religious faith is more common, spiritual practices are positively related to subjective wellbeing, whereas, in cultures where religious socialization is less prevalent, the relationship between spiritual practices and subjective wellbeing is reversed (Lun & Bond, 2013). According to research conducted on the national level among individuals from 154 nations by Diener et al. (2011), the relationship between religiousness and the measures of subjective wellbeing are mediated by the resources provided by religion including social support and life purpose/meaning. Another function of religion is to deliver hope, which can be related to the indirect impact of religiousness on wellbeing.

Numerous studies have confirmed that spirituality and religiousness are important sources of hope (Conco, 1995; Coyle, 2002; Hong et al., 2015; Pargament, 2013). Considering that Chile is a very religious nation and the level of support for religious socialization is relatively high (Lun & Bond, 2013), it can be expected that, among Chilean students, religious practices are positively correlated with spiritual experiences, which in turn are indirectly related to subjective wellbeing through hope.

Practicing-religious people differ from non-religious people and non-practicing religious people with regard to hope as a strength of character. Compared with members of two other groups, practicing-religious individuals scored higher in hope (Berthold & Ruch, 2014). According to Ivtzan et al. (2013), people can have a high level of religious involvement and spirituality (1), a low level of religious involvement with a high level of spirituality (2), a high level of religious involvement with a low level of spirituality (3), or a low level of religious involvement and spirituality (4). Aside from a few exceptions, participants from groups one and two had higher levels of psychological wellbeing, measured self-actualization, meaning in life, and personal growth initiative (Ivtzan et al., 2013). In the line with these results, Chilean students with declared religious affiliations can be expected to have spiritual experiences because of their religious practices but non-affiliated, agnostic, and atheist students may also achieve spiritual experiences through the use of secular practices such as meditation, contemplation, and mindfulness (Cobb et al., 2015; Labelle et al., 2015; Wachholtz & Pargament, 2005). Additionally, prayer can be used as a coping resource among non-believers in difficult life situations and times of crisis.

Religiousness, and Spirituality Similarities and Differences; Their Role in Explaining Hope

Religiousness and spirituality is an area of research explored in many academic and scientific disciplines including sociology, psychology, ethics, medicine, nursing, anthropology, etc. Many researchers have explored the functions of religion and spirituality in the daily lives of individuals, along with the impact of religion and spirituality on health and wellbeing (Sawatzky et al., 2005; Koenig, 2001; Park, 2007; Seybold & Hill, 2001).

Both religiousness and spirituality are multidimensional and multifaceted constructs (Hill et al., 2000; Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging, 1999; Demmrich & Huber, 2019; Saucier & Skrzypińska, 2006) and well-established discussions comparing their similarities and differences are lacking in the literature reviewed in this study (Gall et al., 2011; George et al., 2000; Hodge & McGrew, 2005). Historically, spirituality has its own roots in religion and remains an element of religiousness (Wulff, 1991). Consequently, spirituality's increase in popularity has come at the expense of religiousness (Ribaudo & Takahashi, 2008). The best indicator of this process is the data that shows between 1965 and 2000, there was a significant increase in health-related articles dealing with spirituality and a corresponding decrease in health-related articles addressing religion (Weaver et al., 2006).

According to Pargament (1999), religion currently has a negative connotation and is associated with institutional, ritual-based, and ideological practices, in contrast to spirituality, which is defined as a non-static entity and a dynamic, positive process that focuses on individual and personal feelings, experiences, and thoughts.

In the literature examined in this study, there is no coherent or straightforward approach to analyzing the similarities and differences of both concepts although some general findings are available. First, regardless of the research samples, participants view religiousness and spirituality as separate but overlapping constructs more than the same or completely different phenomena (Baumsteiger & Chenneville, 2015; Hodge & McGrew, 2005; Hyman & Handal, 2006). For example, in a study by Zinnbauer et al. (1997), self-rated spirituality correlated positively with self-rated religiousness. In another study, 60% of research students confirmed that a relationship exists between spirituality and religion (Hodge & McGrew, 2005). While spirituality is a broader concept than religion, religiousness is a form of spirituality and spirituality includes religion (Baumsteiger & Chenneville, 2015; Hyman & Handal, 2006). In the surveyed research, participants more often identified with a definition of spirituality as internal, individual, and subjective (Baumsteiger & Chenneville, 2015; Hyman & Handal, 2006) as opposed to religion as external, collective, and objective (Baumsteiger & Chenneville, 2015; Hyman & Handal, 2006).

Additionally, compared to spirituality, religion is more frequently indicated as a theistic practice (Schlehofer et al., 2008), one connected with organized spiritual practices like rituals, worship, etc. (Baumsteiger & Chenneville, 2015; Hodge & McGrew, 2005; Hyman & Handal, 2006) that possesses negative connotations (Baumsteiger & Chenneville, 2015; Schlehofer et al., 2008).

Religion, whether in traditional or non-traditional forms, provides a supportive context for spiritual growth (Hill & Pargament, 2003; Davis et al., 2015). Recent studies have confirmed that most aspects of religiousness are related to spirituality (Heintz & Baruss, 2001). In a study by Zinnbauer et al. (1997), participants' self-rated spirituality was positively related to respondents' frequency of prayer and church attendance.

Religious practices are positively correlated with spiritual experiences. For example, in a study conducted by Park et al. (2012) on a representative sample of American adults, a four-class model was identified based on spiritual and religious involvement: highly religious, moderately religious, somewhat religious, and minimally religious or non-religious. Compared with members of other groups, highly religious individuals scored higher in prayer, attending religious services, positive religious coping, and daily spiritual experiences. Johnson et al. (2008) conducted a factor analysis using different measures of spirituality and religiousness and observed that spiritual experiences strongly correlate with religious practices such as prayer and church attendance. American adults with organized and private religious practices had positive relations with spiritual experiences (Yoon et al., 2015). In a sample of Salvadoran youth, religiousness (consisting of inter alia religious event participation) positively predicted spirituality (King et al., 2020), which, in turn, improved hope. Religious practices indirectly influenced hope through spiritual experiences among Polish, codependent, female members of Al-Anon (Wnuk, 2015) as well as in a sample of members of Alcoholics Anonymous in Poland (Wnuk, 2021).

Hypothesis 1

In a sample of Chilean students, religious practices are indirectly related to hope through spiritual experiences.

Hope

In psychology, hope is considered to be a strength of character that is part of transcendence virtue (Seligman, Peterson, & Park, 2004a; Seligman, Peterson, & Park, 2004b), trait or state (Snyder, 2002), as well as emotion (Lazarus, 1999). Despite their differing approaches, researchers underline the multidimensional character of hope (Scioli et al., 2011). The subject of hope is of importance and value to the individual. Hope is reflected in one's thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and relations with other people; it consists of an element of prediction, making it future-oriented but rooted in the present and connected to the past (Stephenson, 1991).

According to Kozielecki (2006), hope consists of cognitive, emotional, affiliative, temporal, and causative factors. The cognitive dimension of hope relates to convictions about goal-reaching, obtaining a significant result, and/or value realizations. These convictions are “saturated with emotions and feelings that influence the perception of the attractiveness of the subject of hope, thus constituting its emotional aspect. The affiliative factor of hope is concerned with people who, through their behavior, help to create or maintain hope for reaching their desired goal. Temporal aspect of hope is defined as a “concentrating on future but based on experiences from the past and present” (Stephenson, 1991).

The causative dimension of hope has a motivational role in maintaining activity and behaviors directed at reaching the desired goal. Kozielecki (2006) divides hope into four types based on two main dimensions. On one end of the continuum, he places “particular hope,” with “generalized hope” on the opposite end. Hope may have an active or passive character. “Generalized hope” does not concern any concrete goal. “Particular hope” is focused on a specific result. Hope with a passive character activates assumptions that no engagement is happening in any activity, adhering to an assumption that even though there is no activity toward reaching the goal, the goal will be reached. Hope leads to actions that are focused on achieving a goal. The main strategies that help maintain hope are the presence of significant relationships with other people and the ability to experience ease. Possessing attributes like determination, courage and serenity, clear goals, spiritual faith, the ability to summon positive memories, and having respect for and acceptation of others' individuality all facilitate the hope-maintaining and developing process (Herth, 1990). This study adopts the definition of hope as a trait of character. According to this definition, “hope is a multidimensional, dynamic life force that can be characterized as a certainty that reaching “good” is possible and that a personally valuable and significant goal is achievable” (Dufault & Martochio, 1985).

The Indirect Relationship Between Religiousness/Spirituality and Subjective Wellbeing Through Hope

The positive impact that religiousness/spirituality has on shaping hope has been confirmed in studies of oncology patients (Bowes et al., 2002; Fehring et al., 1997; Herth, 1989), family members looking after their terminally-ill relatives (Herth, 1993), terminally-ill patients (Buckley & Herth, 2004), codependent individuals participating in self-help groups (Wnuk, 2015), as well as students (Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014). Many more studies have confirmed the positive relationship between hope and subjective wellbeing. Subjective wellbeing refers to one's satisfaction with life and the extent to which one experiences positive feelings and/or general happiness (Diener, 2009). It is characterized by low levels of neuroticism or negative affect and concomitant high levels of positive affect (Diener, 2009). In a study by Proyer et al. (2011), among all strengths of character, hope had the strongest correlation to present and future life satisfaction. The same result was achieved in three internet samples of adults (Park et al., 2004a, 2004b). Similarly, Peterson et al. (2007) found that among both American and Swiss adults, the strength most highly linked to life satisfaction was hope. A longitudinal study by Ciarrochi et al. (2015) confirmed that hope is an antecedent to the positive as well as negative affect of adolescents.

Recent studies conducted among adolescents and students from different countries have emphasized that religious and spiritual variables are indirectly related to different wellbeing indicators through hope.

In a longitudinal study conducted on Portuguese adolescents, Marques et al. (2013) confirmed the mediating role of hope between religious practices and life satisfaction. According to a recent study of college students from USA, spirituality and religiosity indirectly influenced depressive symptoms through hope (Chang et al., 2016). The same effect was noticed in a study of students in Poland (Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014). In this research, more frequent spiritual experiences were correlated with a higher level of hope, which in turn was related to increased intensity of positive affect and life satisfaction.

There is no existing research about the spiritual/religious sphere of life and hope as it relates to Chilean students and its potential influence on their wellbeing. Recent studies conducted on a sample of Chilean adults have confirmed the positive role of spirituality and religiousness in wellbeing (Gallardo-Peralta, 2017; Fernández, Lorca & Valenzuel, 2020). This study has a purpose to fill this gap examining the mechanisms undelaying the relationship between religiousness as well as spirituality and subjective wellbeing.

Hypothesis 2

In a sample of Chilean students, spiritual experiences are indirectly related to subjective wellbeing through hope.

Method

Participants

The research sample within this study consisted of university students from Chile. Questionnaires in Spanish language were given to students after classes and, upon completion, were collected by an overseas student with Polish grant funding. Among 180 distributed questionnaires, two students did not consent to participate in research and one student did not completely fill the questionnaires. Finally in research remainded 177 students. Due to the potential lack of harmful effect of participation in research agreement of ethical committee was not required. Descriptive statistics of socio-demographics variables were presented in Table 1. All participants had a secondary education and used Spanish language. From the religious affiliation sample was heterogeneous.

Table 1.

Demographics variables in Chilean students sample (n = 177).

(Source: author’s research)

| Classification | Percentage or Mean | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 62% |

| Women | 38% | |

| Age | 21.35 years | |

| Education | Secondary | 100% |

| Languages | Spanish | 100% |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic church | 55,37% |

| Evangelicalism | 10.96% | |

| Seventh-day Adventists | 8.3% | |

| Jehovah's witness | 2.2% | |

| Mormons | 1.1% | |

| Tribal religions | 0.6% | |

| Atheists | 6.7% | |

| Agnostics, | 7.57% | |

| Non-affiliated | 7.2% |

Measure

The Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) consists of 16 questions, each with six points ranging from 1 (never or almost never) to 6 (many times daily). The Spanish language version of this tool was used (Mayoral et al., 2013). The more points scored, the greater the respondent's level of spirituality. Depending on population, the scale’s reliability ranges from α = 0.86 to 0.95 (Underwood, 2011). The short version of this measure was used, which consists of six items.

Two measurement scales concerning religious practices were used. The first measurement was based on a five-point scale and measured how frequently participants attended Mass. The options on this scale consisted of never with the exception of baptisms, marriages, or funerals (1), a few times a year (2), 1–2 times monthly (3), 2–3 times monthly (4), and once per week or more (5). The second scale measures respondents' frequency of prayer. Participants reported how often they prayed, with response options ranging from never, to sometimes, once monthly, once weekly, or every day.

The Positive and Negative Affects Schedule (PANAS) consists of ten statements related to positive emotional states and another ten concerning negative ones. Each question is graded from 1 = a little or none to 5 = very frequently. The more points scored, the greater a person’s negative as well as positive affect. Participants were asked to assess their emotional state based on how often they related to particular questions up to the weekend before the survey. The Spanish language version of this measure was used (Ortuño-Sierra et al., 2015). According to studies, the reliability scale varied from α = 0.86 to 0.89 for the positive affect and α = 0.84 to 0.85 for the negative affect (Crawford & Henry, 2004).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a universally-recognized tool used to measure one's mental wellbeing based on an operational concept of satisfaction with life, defined by a conscious assessment/judgment of one’s life compared to self-imposed standards (Diener et al., 1985). The Spanish language version of this measure was used (Vázquez et al., 2013). This measure consists of five statements that are graded according to a seven-point scale. According to this measure, the greater the points, the more satisfied the respondent is with life. This scale possesses satisfactory psychometric properties in this study. Its reliability is 0.83, as determined by the test–retest method after a two-week repeated study, which rose to 0.84 after a month but then ranged between 0.64 and 0.82 after two months (Pavot & Diener, 1993). The more points scored, the greater the respondent's life satisfaction. The method’s unequivocal nature has been confirmed by various studies (Diener et al., 1985; Pavot et al., 1991; Shevlin & Bunting, 1994).

The Hope Herth Index (HHI) is a scale used for the measurement of hope based on a particular definition of hope. The Spanish language version of this measure was used (Arnau, et al., 2010). Participants answered 12 questions expressed on the four-step Likert scale (1–4) ranging from 1 (I strongly disagree) to 4 (I strongly agree) (Herth, 1992). The reliability of this scale has satisfactory psychometrical features. In reference to patients' scores, α = 0.97 (Herth, 1992) were evaluated with the test–retest method score of 0.91 (Herth, 1992).

Statistical Analysis

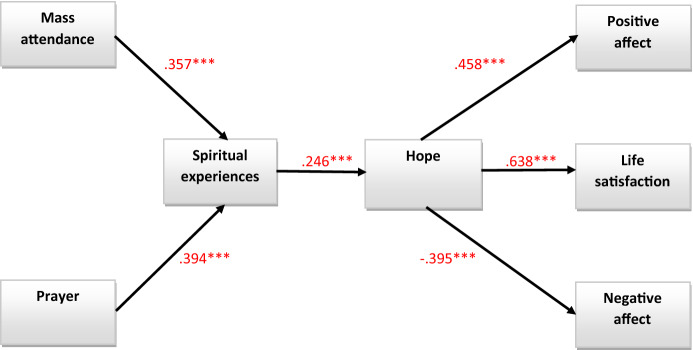

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 27.0). To verify potential multicollinearity problem values of Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for research variables were computed. Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypothesis. A tested model reflecting the research hypotheses is shown in Fig. 1. The following model of fit indices was used: normed fit index (NFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Critical values for good model fit have been recommended for the CFI to be acceptable above the 0 90 level and RMSEA should be 0 05 or less and should not exceed 0 08 (Wang & Wang, 2012). The level of NFI should exceed 0.90, as should the levels of GFI (0.90) and CFI (0.93) (Steiger, 1990). Also, based on the chi-square statistic, the values of CMIN/df statistics should be lower than the required standard, 2 or 3 (Byrne, 1994).

Figure 1.

Model of research. Note. The standardized regression coefficients are presented. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. For the sake of legibility, the correlations between the residuals were omitted in Fig. 1. (

Source: author’s research)

Results

The descriptive statistics and reliability of the measurements used are presented in Table 2. The values of the r-Pearson correlation coefficients are presented in Table 3. There were no values of VIF exceeding 5 (see Table 2), thus, the multicollinearity problem was not likely to exist (Menard, 2001). The values of RMSEA = 0.000 (90% CI [0.000, 0.0039]), NFI = 0.982, GFI = 0.989, AGFI = 0.975, CFI = 1, chi2 = 6.73, df = 12, p = 0.895 (CMIN/df = 0.561) indicated that the fit between the measurement model and the data were acceptable. Due to the relatively small sample size, the Bollen–Stine bootstrapping method was used to increase the likelihood of veracity of the obtained results and verified direct and indirect effects. The Bollen–Stine bootstrapping method (p = 0.881) performed on 5,000 samples confirmed the good fit of the tested model.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and reliability of scales in Chilean students sample (n = 177). (

Source: author’s research)

| Measures | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Minimum | Maximum | VIF | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prayer | 2.84 | 1.47 | 0.298 | − 1.413 | 1 | 5 | 1.85 | |

| Mass attendance | 2.81 | 1.90 | 0.980 | − 0.192 | 1 | 5 | 1.80 | |

| DSES | 18.22 | 6.74 | 0.074 | − 0.907 | 6 | 35 | 1.06 | 0.85 |

| PANAS | ||||||||

| Positive affect | 16.47 | 3.51 | 0.169 | 0.242 | 6 | 25 | 0.72 | |

| Negative affect | 14.06 | 4.22 | 0.685 | 0.260 | 5 | 25 | 0.82 | |

| SWLS | 27.04 | 5.41 | − 1.188 | 1.147 | 6 | 35 | 0.83 | |

| HHI | 36.76 | 4.62 | − 0.240 | 1.122 | 24 | 55 | 1.88 | 0.77 |

DSES—Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale; PANAS—Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; SWLS—Satisfaction with Life Scale; HHI—Herth Hope Index, VIF—Variance inflation factor

Table 3.

Correlation matrix in Chilean students sample (n = 177). (

Source: author’s research)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Life satisfaction | ||||||

| 2. Positive affect | 0.47** | |||||

| 3. Negative affect | − 0.38** | − 0.15 | ||||

| 4. Spiritual experiences | 0.24** | 0.14 | − 0.10 | |||

| 5. Hope | 0.64** | 0.46** | 0.39** | 0.25** | ||

| 6. Prayer | 0.13 | 0.01 | − 0.05 | 0.61** | 0.16* | |

| 7. Mass attendance | 0.16* | 0.01 | − 0.04 | 0.59** | 0.17* | 0.60** |

*p ≤ 0,05

**p ≤ 0,01

The standardized direct effects of prayer on spiritual experiences and Mass attendance on spiritual experiences were statistically significant, respectively, (CI 95% [0.257; 0.519], β = 0.394, p = 0.000) and (CI 95% [0.219; 0.485], β = 0.357, p = 0.000). The standardized direct effects of spiritual experiences on hope was statistically significant (CI 95% [0.106; 0.385], β = 0.246, p = 0.001) and hope in turn were statistically significantly related to life satisfaction (CI 95% [0.539; 0.716], β = 0.638, p = 0.000), positive affect (CI 95% [0.322; 0.569], β = 0.458, p = 0.001), and negative affect (CI 95% [ − 0.515; − 0.263], β = − 0.395, p = 0.000).

The indirect effects of prayer through spiritual experiences on hope was statistically significant 0.10, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.040; 0.169],), the same as indirect effect of prayer on life satisfaction 0.06, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.26; 0.113]), indirect effect of prayer on positive affect 0.04, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.181; 0.84]) as well as indirect effect of prayer on negative affect -0.04, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [ − 0.76; − 0.16]).

Also noticed statistically significant indirect effects of Mass attendance on spiritual experiences through hope 0.09, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.037; 0.163]), the same as indirect effect of Mass attendance on satisfaction with life 0.06, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.023; 0.106]), indirect effect of Mass attendance on positive affect 0.04, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.16; 0.78]), as well as indirect effect of Mass attendance on negative affect − 0.3, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [ − 0.065; − 0.017]).

Additionally spiritual experiences were statistically significantly, indirectly through hope related to life satisfaction 0.16, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.066; 0.256]), as well as positive and negative affect, respectively, 0.11, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [0.048; 0.194]) and − 0.10, p = 0.001 (CI 95% [ − 0.041; − 0.173]).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine two indirect mechanisms in the relationship between religious practices and hope through spiritual experiences and in the relationship between spiritual experiences and subjective wellbeing through hope. According to obtained results, the relationship between spiritual experiences and subjective wellbeing of the Chilean students is indirect, and the variable being underlying this relation is hope. This means that, for Chilean students, spiritual experiences are a positive predictor of their level of hope, which in turn is related to increased life satisfaction and positive affect and decreased negative affect. These results are largely consistent with the recent studies conducted among youth and their family members from Republic of South Africa (Nell & Rothmann, 2018), as well as students from Poland (Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014), students from USA (Chang et al., 2016), adults from the USA (Chang et al., 2013), members of Alcoholics Anonymous from Poland (Wnuk, 2021) and oncology patients (Zarzycka et al., 2019). These findings suggest that the mechanism of spirituality's indirect relationship with subjective wellbeing through hope can be universal, independent of the conceptualization of these constructs, the measures used, cultural contexts, and research sample populations.

In explanation of the observed mechanism is worth focusing on youth individuals and students as a comparable sample. In comparison with the study by Wnuk and Marcinkowski (2014), another measure of life satisfaction was used, short instead of normal versions of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale was applied, sample was heterogeneous regarding religious denominations and it was preserved balance between men and women. Among the students surveyed from Poland, all were Roman Catholic. Regardless of the noticed differences in both samples, spiritual experiences were indirectly related to subjective wellbeing via hope. Although among Polish students, spiritual experiences were not indirectly related to negative affect, this discrepancy could be explained using another older and not as reliable verification method of indirect effect (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

It is worth noting that there was no statistically significant correlation between spiritual experiences and negative affect in Chilean students (see Table 3), and the use of structural equation modeling revealed that this relationship is indirect. In a Wnuk and Marcinkowski study (2014), the strength of the r-Pearson correlation between spiritual experiences and negative affect was not statistically significant but it was twice as large as the correlation for Chilean students, meaning that the use of SEM instead of multiple regression analysis could confirm that this association is indirect.

Also, a sample of students from Republic of South Africa that used another measure of hope and religiousness confirmed that religious involvement leads to hope, which in turn is positively correlated with life satisfaction as well as positive affect and negatively related to negative affect (Nell & Rothmann, 2018).

In every analyzed group of research participants (Chang et al., 2016; Nell & Rothmann, 2018; Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014), religious socialization was rather prevalent and on a comparable level (Lun & Bond, 2013) to the level of religiousness (Diener et al., 2011; Graham & Crown, 2014; Stavrova et al., 2013) as a potential source of differences in results. This means that this cultural factor was not significant from the perspective of potential differences in research results.

The hypothesis that religious practices are indirectly related to hope via spiritual experiences was fully confirmed. This means that in the sample of Chilean students, prayer and Mass attendance are correlated with spiritual experiences, which in turn are related to hope. The results of this study are consistent with recent research (Wnuk, 2015; King et al., 2020) that confirmed an indirect relationship between different facets of religiousness and hope via spiritual experiences. In Wnuk's study (2015), in a sample of codependent individuals participating in Al-Anon, apart from private and public indicators of religiosity such as prayer and Mass attendance, other religious facets such as strength of faith and religious coping were indirectly related to hope through spiritual experiences. It is important to note that in comparison to the Wnuk study (2015), the same measures of hope, religiousness, and spiritual experiences were used in this study. There was only one difference regarding the use of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale's short form.

Consistent with data from another research, religious practices are probably significant ways lead to spiritual growth (Johnson et al., 2008; Yoon et al., 2015; Zinnbauer et al., 1997). Among Chilean students, prayer and Mass attendance were positively associated with spiritual experiences. The obtained results show that religiousness, measured by religious practices, and spirituality, measured by spiritual experiences, are rather separate but overlapping constructs (Baumsteiger & Chenneville, 2015; Hodge & McGrew, 2005; Hyman & Handal, 2006). The strength of relationships between prayer and spiritual experiences as well as Mass attendance and spiritual experiences were moderate. Spiritual experiences were directly related to hope but religious practices were only indirectly related to hope via spiritual experiences.

Additionally, spirituality, operationalized as a spiritual experiences, seems to be a wider concept than religiousness, understood as a religious practices. Chilean students may be using other secular practices that can lead to spiritual experiences such as meditation, contemplation, and mindfulness (Cobb et al., 2015; Labelle et al., 2015; Wachholtz & Pargament, 2005). Considering that many Chilean students declared themselves to be atheists and agnostics does not mean that religious-affiliated students cannot use secular practices and exercises to spiritual growth. Further research examining not only religious but additionally secular practices could verify this assumption.

It is important to emphasize that the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale used to examine spiritual experiences is the measure that reflects the approach to religiousness and spirituality as overlapping constructs, independent from religious denominations. Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale contains items that are more specifically theistic in nature but also remains appropriate for those who are not comfortable with theistic language (Underwood, 2011).

For Chilean students, prayer and Mass attendance are connected with feeling God’s presence, finding strength in religion or spirituality, feeling deep inner peace or harmony, feeling God’s love through others, feeling spiritually touched by the beauty of creation, and a desire to be closer to God or in union with the divine. These spiritual experiences are probably the source of their hope and are reflected through their positive outlook toward life, their capability to recall happy/joyful times, feelings that life has value and worth, maintaining a sense of direction, lacking fear of the future, not feeling alone, having a deep inner strength, and believing that each day has potential. In turn, hope is for them a condition for living a satisfied and happy life. For Chilean adolescents, hope as a result of spiritual experiences is an important mental and emotional force in everyday life that aids them in their struggles with emerging adulthood goals, conflicts, problems, and difficulties connected with this period of life.

The conducted research yields some theoretical and practical implications. In a sample of Chilean students, religious practices were indirectly related to hope through spiritual experiences, and subjective wellbeing via the path of spiritual experiences and hope. Also, spiritual experiences indirect effect on subjective wellbeing through hope was recognized.

This predictive role of hope for Chilean students' subjective wellbeing indicates a need to implement hope-based interventions and programs for this population. It is a practical incentive for therapists and counselors to engage in preparing and implementing these kinds of intervention tools. Some studies have confirmed the efficiency of hope-based intervention programs for different facets of wellbeing, especially depression (Chan et al., 2019; Cheavens et al., 2006; Retnowati et al., 2015; Shekarabi-Ahari et al., 2012). The finding that religious practices probably indirectly influence subjective wellbeing can be of practical use to therapists and counselors working with religious students or within pastoral contexts. This means that religious-affiliated students can be encouraged by therapists and counselors to become involved in religious practices to improve their subjective wellbeing. Tailoring spiritual intervention focus on spiritual growth can lead to enhance students' wellbeing via hope. Recent research has indicated that religious and spiritual interventions in randomized, controlled clinical trials lead to positive outcomes such as decrease stress, alcoholism, and depression (Gonçalves et al., 2015).

Limitations and Future Research

This Study has Several Limitations

First, this study was based on students (i.e., young adults), which means that the generalizability of the findings is limited compared to the general student population of Chile. It is important to verify if similar or different findings can be revealed among diverse racial/ethnic groups (Gillum & Griffith, 2010) or in different cultural (Chang et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2013; Nell & Rothmann, 2018; Wnuk & Marcinkowski, 2014) and socio-economical (Diener et al., 2011; Lun & Bond, 2013) contexts. Recent studies have indicated that religion can play a positive role in wellbeing among populations that present high levels of religiousness (Diener et al., 2011; Graham & Crown, 2014; Stavrova et al., 2013) with relatively bad social conditions (Diener et al., 2011), where religious socialization is more prevalent and, unexpectedly, where social hostility toward religious groups is more intense (Lun & Bond, 2013). It is also important to verify if the present findings can be generalized across respondents from specific religious denominations (i.e., Catholics, Buddhists, Jews, and Muslims). In a study conducted on individuals affiliated with one of the four major religions (Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam), Diener, Tay, and Myers found that the relational patterns within the religiousness–wellbeing relationship are more similar than distinct (2011).

Because these findings must be interpreted as mainly applying to young adults, additional research is necessary to investigate the strength and nature of these relationships in samples among children, older adults, and geriatric populations. Considering that the SEM requires a large sample of participants, this research group was relatively small but the use of the bootstrapping method balanced this disproportion. This research was cross sectional, not longitudinal, which is why the described relationships cannot be analyzed from the cause-and-effect perspective. Another direction in the relationships between spiritual experiences, hope, and subjective wellbeing cannot be eliminated. It is possible that spiritual experiences is also positively correlated with subjective wellbeing, which in turn is positively connected with hope.

It would be interesting to verify the indirect impact of spirituality on wellbeing using hope as a bi-dimensional (Snyder, 2002) construct. An investigation of this nature could be especially important considering that the results of recent studies in this area remain inconsistent. For example, Nell and Rothmann (2018) found that both pathway and agency hope mediate the relationships between religiosity and life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. The same pattern was revealed in a study by Chang et al. (2013) that used depressive symptoms as a dependent variable and spirituality as well as religiosity as independent variables. In another study conducted by Chang et al. (2016) on a different sample, only hope agency was found to be a mediator between ritualistic, theistic, and existential spirituality and depressive symptoms. This study was also limited by its use of a uni-dimensional measure of spirituality. Future research should focus on using another measures of spirituality, especially multidimensional measures, to examine if every facet of spirituality indirectly influences subjective wellbeing via hope.

In this study, only two indicators of religiousness were used (prayer and Mass attendance) as potential sources of spiritual experiences. It would be interesting to explore another religious practice like reading the Bible, or another religious indicators such as religious orientation, religious faith, or religious coping as antecedents of spirituality. Also examining additional non-religious, secular sources of potential spiritual experiences such as meditation, and contemplation (Davis et al., 2015) could provide interesting results.

Funding

This study was funded by author sources.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Author of this publication declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aghababaei N, Błachnio A. Purpose in life mediates the relationship between religiosity and happiness: Evidence from Poland. Mental Health, Religion and Culture. 2014;17(8):827–831. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2014.928850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aglozo EY, Akotia CS, Osei-Tutu A, Annor F. Spirituality and subjective well-being among Ghanaian older adults: Optimism and meaning in life as mediators. Aging and Mental Health. 2021;25(2):306–315. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1697203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnau RC, Martinez P, Niño de Guzmán I, Herth K, Yoshiyuki Konishi C. A spanish-language version of the Herth Hope Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation in a peruvian sample. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2010;70(5):808–824. doi: 10.1177/0013164409355701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baetz M, Toews J. CIinical implications of research on religion, spirituality, and mental health. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie. 2009;54(5):292–301. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumsteiger R, Chenneville T. Challenges to the conceptualization and measurement of religiosity and spirituality in mental health research. Journal of Religion and Health. 2015;54(6):2344–2354. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold A, Ruch W. Satisfaction with life and character strengths of non-religious and religious people: It’s practicing one’s religion that makes the difference. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes DE, Tamlyn D, Butler LJ. Women living with ovarian cancer: Dealing with an early death. Health Care for Women International. 2002;23:135–148. doi: 10.1080/073993302753429013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, J., & Herth, K. (2004). Fostering hope in terminally ill patients. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987), 19(10), 33–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01740.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows. SAGE Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Canada AL, Parker PA, de Moor JS, Basen-Engquist K, Ramondetta LM, Cohen L. Active coping mediates the association between religion/spirituality and quality of life in ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2006;101(1):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain K, Zika S. Religiosity, life meaning and well-being: Some relationship in a sample of women. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1988;27:411–420. doi: 10.2307/1387379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K, Wong FKY, Lee PH. A brief hope intervention to increase hope level and improve well-being in rehabilitating cancer patients: A feasibility test. SAGE Open Nursing. 2019 doi: 10.1177/2377960819844381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Jilani Z, Fowler EE, Yu T, Chia SW, Yu EA, McCabe HK, Hirsch JK. The relationship between multidimensional spirituality and depressive symptoms in college students: Examining hope agency and pathways as potential mediators. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2016;11(2):189–198. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1037859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Kahle ER, Yu EA, Lee JY, Kupfermann Y, Hirsch JK. Relations of religiosity and spirituality with depressive symptoms in primary care adults: Evidence for hope agency and pathway as mediators. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2013;8(4):314–321. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.800905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM. Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle ACD, Dunkel Schetter CD. Mastery, self-esteem, and optimism mediate the link between religiousness and spirituality and postpartum depression. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2018;41(5):711–721. doi: 10.1007/s10865-018-9941-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheavens JS, Feldman DB, Gum A, Michael ST, Snyder CR. Hope therapy in a community sample: A pilot investigation. Social Indicators Research. 2006;77:61–78. doi: 10.1007/s11205-005-5553-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Parker P, Kashdan TB, Heaven PCL, Barkus E. Hope and emotional well-being: A six-year study to distinguish antecedents, correlates, and consequences. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2015;10(6):520–532. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1015154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb E, Kor A, Miller L. Support for adolescent spirituality: Contributions of religious practice and trait mindfulness. Journal of Religion and Health. 2015;54(3):862–870. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AB, Koenig HG. Religion, religiosity and spirituality in the biopsychos cial model of health and ageing. Ageing International. 2003;28(3):215–241. doi: 10.1007/s12126-002-1005-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conco D. Christian patients' views of spiritual care. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1995;17(3):266–276. doi: 10.1177/019394599501700303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle J. Spirituality and health: Towards a framework for exploring the relationship between spirituality and health. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;37(6):589–597. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-CIinical sample. British Journal of CIinical Psychology. 2004;43:245–265. doi: 10.1348/0144665031752934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DE, Rice K, Hook JN, Van Tongeren DR, DeBlaere C, Choe E, Worthington EL., Jr Development of the Sources of Spirituality Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62(3):503–513. doi: 10.1037/cou0000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmrich S, Huber S. Multidimensionality of spirituality: A qualitative study among secular individuals. Religions. 2019;10(11):613. doi: 10.3390/rel10110613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. In: Diener E, editor. The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. Springer; 2009. pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Tay L, Myers D. The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:1278–1290. doi: 10.1037/a0024402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufault K, Martocchio B. Hope: Its spheres and dimensions. Nursing CIinics of North America. 1985;20:379–391. doi: 10.1037/a0020903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricatore AN, Handal PJ, Rubio DM, Gilner FH. Stress, religion and mental health: Religious coping in mediating and moderating roles. International Journal of the Study of Psychology and Religion. 2004;14:91–108. doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr1402_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring RJ, Miller JF, Shaw C. Spiritual well-being, religiosity, hope, depression, and other mood states in elderly people coping with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1997;24(4):663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging working group. Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute.

- Gall TL, Malette J, Guirguis-Younger M. Spirituality and religiousness: A diversity of definitions. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. 2011;13(3):158–181. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2011.593404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Peralta LP. The relationship between religiosity/spirituality, social support, and quality of life among elderly Chilean people. International Social Work. 2017;60(6):1498–1511. doi: 10.1177/0020872817702433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Larson DB, Koenig HG, McCullough ME. Spirituality and health: What we know, what we need to know. Journal of Social and CIinical Psychology. 2000;19(1):102–116. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum F, Griffith DM. Prayer and spiritual practices for health reasons among American adults: The role of race and ethnicity. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;49(3):283–295. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves JP, Lucchetti G, Menezes PR, Vallada H. Religious and spiritual interventions in mental health care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled CIinical trials. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(14):2937–2949. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C, Crown S. Religion and wellbeing around the world: Social purpose, social time, or social insurance? International Journal of Wellbeing. 2014;4:1–27. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v4i1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz LM, Baruss I. Spirituality in late adulthood. Psychological Reports. 2001;88(3):651–654. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herth KA. he relationship between level of hope and level of coping response and other variables in patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1989;16(1):67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herth K. Fostering hope in terminally-ill people. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1990;15(11):1250–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1992;17:1251–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herth K. Hope in the family caregiver of terminally ill people. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18(4):538–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18040538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. merican Psychologist. 2003 doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2008 doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament K, II, Hood RW, McCullough JME, Swyers JP, Larson DB, Zinnbauer BJ. Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 2008 doi: 10.1111/1468-5914.00119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge D, Mcgrew CC. CIarifying the distinctions and connections between spirituality and religion. Social Work and Christianity. 2005;32(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Lewellyn LA, Rathweg MJ. Exploring Religion-Health Mediators among African American Parishioners. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10(4):511–527. doi: 10.1177/1359105305053416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong PYP, Hodge DR, Choi A. Spirituality, hope, and self-sufficiency among low-income job seekers. Social Work. 2015;60(2):155–164. doi: 10.1093/sw/swu059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman C, Handal PJ. Definitions and evaluation of religion and spirituality items by religious professionals: A pilot study. Journal of Religion and Health. 2006;45:264–282. doi: 10.1007/s10943-006-9015-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivtzan I, Chan CP, Gardner HE, Prashar K. Linking religion and spirituality with psychological well-being: Examining self-actualisation, meaning in life, and personal growth initiative. Journal of Religion and Health. 2013;52(3):915–929. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9540-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Sheets VL, Kristeller JL. Empirical identification of dimensions of religiousness and spirituality. Mental Health, Religion and Culture. 2008;11(8):745–767. doi: 10.1080/13674670701561209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KD, Masters KS, Hooker SA, Ruiz JM, Smith TW. An interpersonal approach to religiousness and spirituality: Implications for health and well-being. Journal of Personality. 2014;82(5):418–431. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King PE, Vaughn JM, Yoo Y, Tirrell JM, Dowling EM, Lerner RM, Geldhof GJ, Lerner JV, Iraheta G, Williams K, Sim ATR. Exploring religiousness and hope: Examining the roles of spirituality and social connections among Salvadoran youth. Religions. 2020;11(2):75. doi: 10.3390/rel11020075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Larson DB. Religion and mental health: Evidence for an association. International Review of Psychiatry. 2001;13(2):67–78. doi: 10.1080/09540260124661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozielecki J. Psychology of hope. Zak Academic Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kvande MN, Klöckner ChA, Moksnes UK, Espnes GA. Do optimism and pessimism mediate the relationship between religious coping and existential well-being? Examining mechanisms in a norwegian population sample. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2015;25(2):130–151. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2014.892350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labelle LE, Lawlor-Savage L, Campbell TS, Faris P, Carlson LE. Does self-report Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on spirituality and posttraumatic growth in cancer patients? The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2015;10(2):153–166. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.927902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler-Row KA. Forgiveness as a mediator of the religiosity—health relationship. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2010;2(1):1–16. doi: 10.1037/a0017584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Hope: An emotion and vital coping resource against despair. Social Research. 1999;66(2):653–678. [Google Scholar]

- Lorca MBF, Valenzuela E. (2020) Religiosity and subjective wellbeing of the elderly in Chile: A mediation analysis. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging. 2020 doi: 10.1080/15528030.2020.1839624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lun VMC, Bond MH. Examining the relation of religion and spirituality to subjective well-being across national cultures. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2013;5(4):304–315. doi: 10.1037/a0033641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marques SC, Lopez SJ, Mitchell J. The role of hope, spirituality and religious practice in adolescents’ life satisfaction: Longitudinal findings. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being. 2013;14(1):251–261. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9329-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayoral EG, Underwood LG, Laca FA, Mejía JC. Validation of the Spanish version of Underwood’s Daily Spiritual Experience Scale in Mexico. International Journal of Hispanic Psychology. 2013;6(2):191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Menard S. Applied logistic regression analysis. 2. Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nell W, Rothmann S. Hope, religiosity, and subjective well-being. Journal of Psychology in Africa. 2018;28(4):253–260. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2018.1505239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nooney J, Woodrum E. Religious coping and church-based social support effects on mental health. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:359–368. doi: 10.1111/1468-5906.00122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortuño-Sierra J, Santarén-Rosell M, Albéniz AP, Fonseca-Pedrero E. Dimensional structure of the Spanish version of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) in adolescents and young adults. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27(3):e1–e9. doi: 10.1037/pas0000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and no. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 1999;9(1):3–16. doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr0901_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. Conversations with Eeyore: Spirituality and the generation of hope among mental health providers. Bulletin of the Menninger CIinic. 2013;77(4):395–412. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2013.77.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Religiousness/spirituality and health: A meaning systems perspective. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30(4):319–328. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Malone MR, Suresh DP, Bliss D, Rosen RI. Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2008;17(1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Roh S, Yeo Y. Religiosity, social support, and life satisfaction among elderly Korean immigrants. The Gerontologist. 2012;52(5):641–649. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Reply: Strengths of character and well-being: A CIoser look at hope and modesty. Journal of Social and CIinical Psychology. 2004;23(5):628–634. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.5.628.50749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and CIinical Psychology. 2004;23(5):603–619. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychological Asessment. 1993;5:164–172. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot WG, Diener E, Colvin CR, Sandvik E. Further validation of the Satisfaction With Life Scale: Evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;57(1):149–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Ruch W, Beermann U, Park N, Seligman MEP. Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2007;2(3):149–156. doi: 10.1080/17439760701228938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poloma MM, Pendleton BF. Religious domains and general well-being. Social Indicators Research. 1990;22:255–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00301101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Feaster DJ, Schwartz SJ, Pratt IA, Smith L, Szapocznik J. Religious involvement, coping, social support, and psychological distress in HIV-seropositive African American mothers. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8(3):221–235. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000044071.27130.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proyer RT, Gander F, Wyss T, Ruch W. The relation of character strengths to past, present, and future life satisfaction among German-speaking women. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2011;3(3):370–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01060.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Retnowati S, Ramadiyanti DW, Suciati AA, Sokang YA, Viola H. Hope intervention against depres-sion in the survivors of cold lava flood from Merapi Mount. Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015;165:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ribaudo A, Takahashi M. Temporal trends in spirituality research: A meta-analysis of journal abstracts between 1944 and 2003. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging. 2008;20(1–2):16–28. doi: 10.1080/15528030801921972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G, Skrzypińska K. Spiritual but not religious? Evidence for two independent dispositions. Journal of Personality. 2006;74(5):1257–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky R, Ratner PA, Chiu L. A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicators Research. 2005;72(2):153–188. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-5577-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer CHA, Gorsuch RL. Psychological adjustment and religiousness: The multivariate belief-motivation theory of religiousness. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1991;30:448–461. doi: 10.2307/1387279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlehofer MM, Omoto AM, Adelman JR. How do "religion" and "spirituality" differ? Lay definitions among older adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2008;47(3):411–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00418.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scioli A, Ricci M, Nyugen T, Scioli ER. Hope: Its nature and measurement. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2011;3(2):78–97. doi: 10.1037/a0020903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seybold KS, Hill PC. The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(1):21–24. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shekarabi-Ahari G, Younesi J, Borjali A, Ansari-Damavandi S. The effectiveness of group hope therapy on hope and depression of mothers with children suffering from cancer in tehran. Iranian Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012;5(4):183–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin ME, Bunting PB. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1994;79:1316–1318. doi: 10.2466/pms.1995.80.1.304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Anderman SJ, Schrimshaw EW. Religion and coping with health-related stress. Psychology and Health. 2001;16(6):631–653. doi: 10.1080/08870440108405864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR. Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(4):249–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrova O, Fetchenhauer D, Schlösser T. Why are religious people happy? The effect of the social norm of religiosity across countries. Social Science Research. 2013;42(1):90–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Frazier P. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:574–582. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson C. The concept of hope revisited for nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1991;16(12):1456–1461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood LG. The daily spiritual experience scale: Overview and results. Religions. 2011;2(1):29–50. doi: 10.3390/rel2010029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez C, Duque A, Hervás G. Satisfaction with life scale in a representative sample of Spanish adults: Validation and normative data. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2013;16:E82. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2013.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez C, Páez D. Post-traumatic Growth in Spain. In: Weiss T, Berger R, editors. Posttraumatic Growth and Culturally Competent Practice. Wiley; 2011. pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Vilchensky N, Kravetz S. How are religious belief and behavior good for you? An investigation of mediators religion to mental health in a sample of Israeli Jewish students. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44:459–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2005.00297.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wachholtz AB, Pargament KI. Is spirituality a critical ingredient of meditation? Comparing the effects of spiritual meditation, secular meditation, and relaxation on spiritual, psychological, cardiac, and pain outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28(4):369–384. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang X. Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. Wiley; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Warren P, Van Eck K, Townley G, Kloos B. Relationships among religious coping, optimism, and outcomes for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2015;7(2):91–99. doi: 10.1037/a0038346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watlington CG, Murphy CM. The roles of religion and spirituality among African American survivors of domestic violence. Journal of CIinical Psychology. 2006;62(7):837–857. doi: 10.1002/jCIp.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A, Pargament K, Flannelly K, Oppenheimer J. Trends in the Scientific Study of Religion, Spirituality, and Health: 1965–2000. Journal of Religion and Health. 2006;45(2):208–214. doi: 10.1007/s10943-006-9011-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber SR, Pargament KI. The role of religion and spirituality in mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2014;27(5):358–363. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wnuk, M. (2021). Indirect relationships between spiritual experiences and life satisfaction among Alcoholics Anonymous from Poland. Mediating role of hope, optimism and abstinence. Journal of Religion and Health (in review).

- Wnuk M. Determining the influence religious-spiritual values on levels of hope and the meaning of life in alcohol co-dependent subjects receiving support in self-help groups. Journal of Substance Use. 2015;20(3):194–199. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2014.896954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wnuk M, Marcinkowski JT. Do existential variables mediate between religious-spiritual facets of functionality and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53(1):56–67. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9597-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff DM. Psychology of religion: CIassic and contemporary views. Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E, Chang CCT, Clawson A, Knoll M, Aydin F, Barsigian L, Hughes K. Religiousness, spirituality, and eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2015;28(2):132–149. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2014.968528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka B, Śliwak J, Krok D, Ciszek P. Religious comfort and anxiety in women with cancer: The mediating role of hope and moderating role of religious struggle. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28(9):1829–1835. doi: 10.1002/pon.5155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer B, Pargament K, Cole B, Rye M, Butter E, Belavich T, Hipp K, Scott AB, Kadar J. Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997;36(4):549–564. doi: 10.2307/1387689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]