PURPOSE

Multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by copy number abnormalities (CNAs), some of which influence patient outcomes and are sometimes observed only at relapse(s), suggesting their acquisition during tumor evolution. However, the presence of micro-subclones may be missed in bulk analyses. Here, we use single-cell genomics to determine how often these high-risk events are missed at diagnosis and selected at relapse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

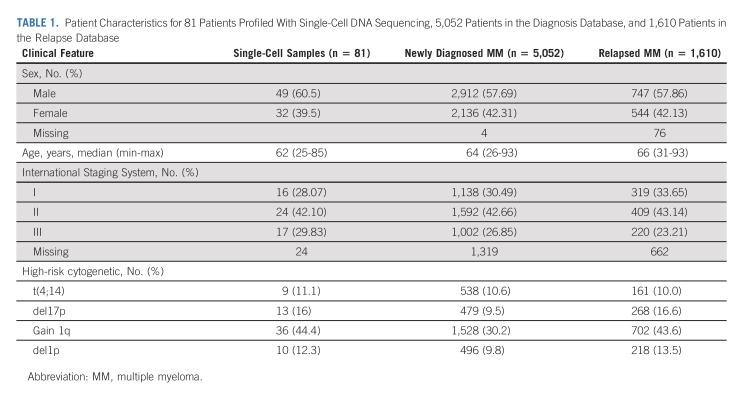

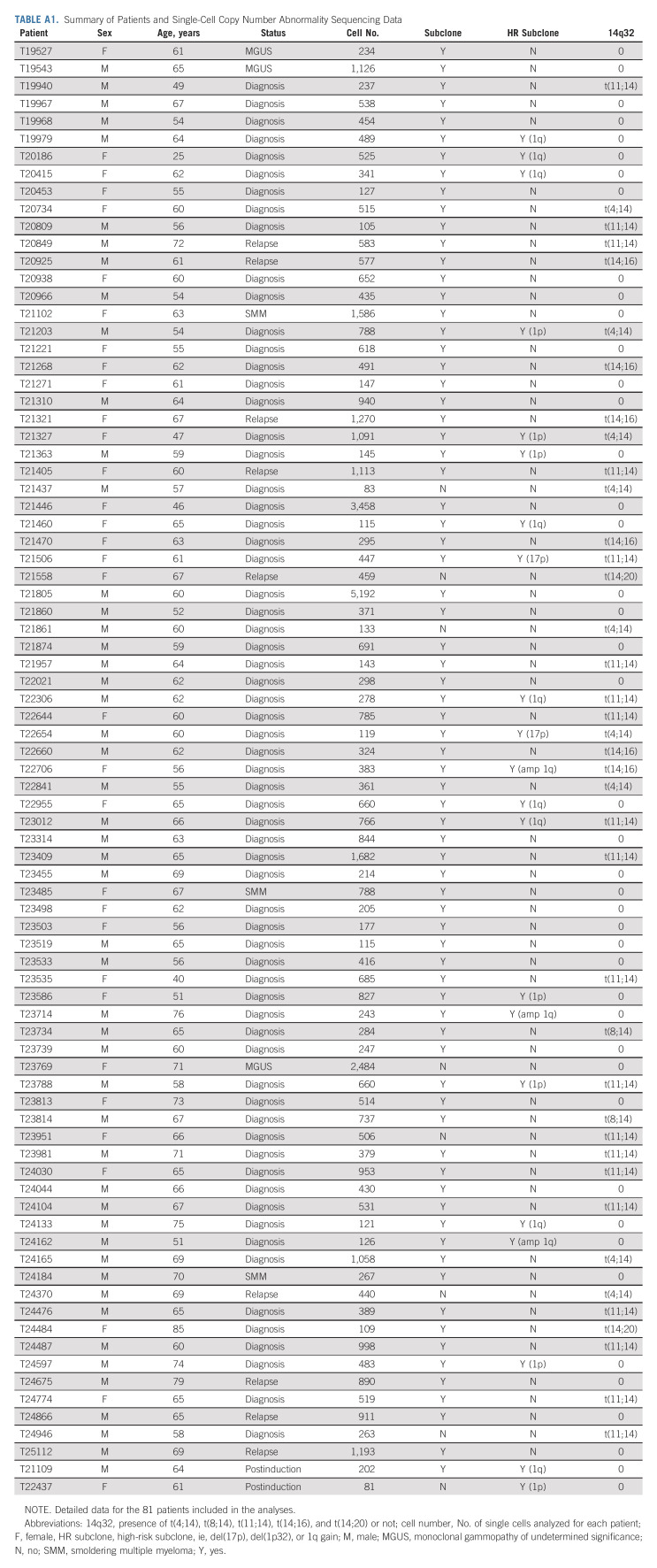

We analyzed 81 patients with plasma cell dyscrasias using single-cell CNA sequencing. Sixty-six patients were selected at diagnosis, nine at first relapse, and six in presymptomatic stages. A total of 956 newly diagnosed patients with MM and patients with first relapse MM have been identified retrospectively with required cytogenetic data to evaluate enrichment of CNA risk events and survival impact.

RESULTS

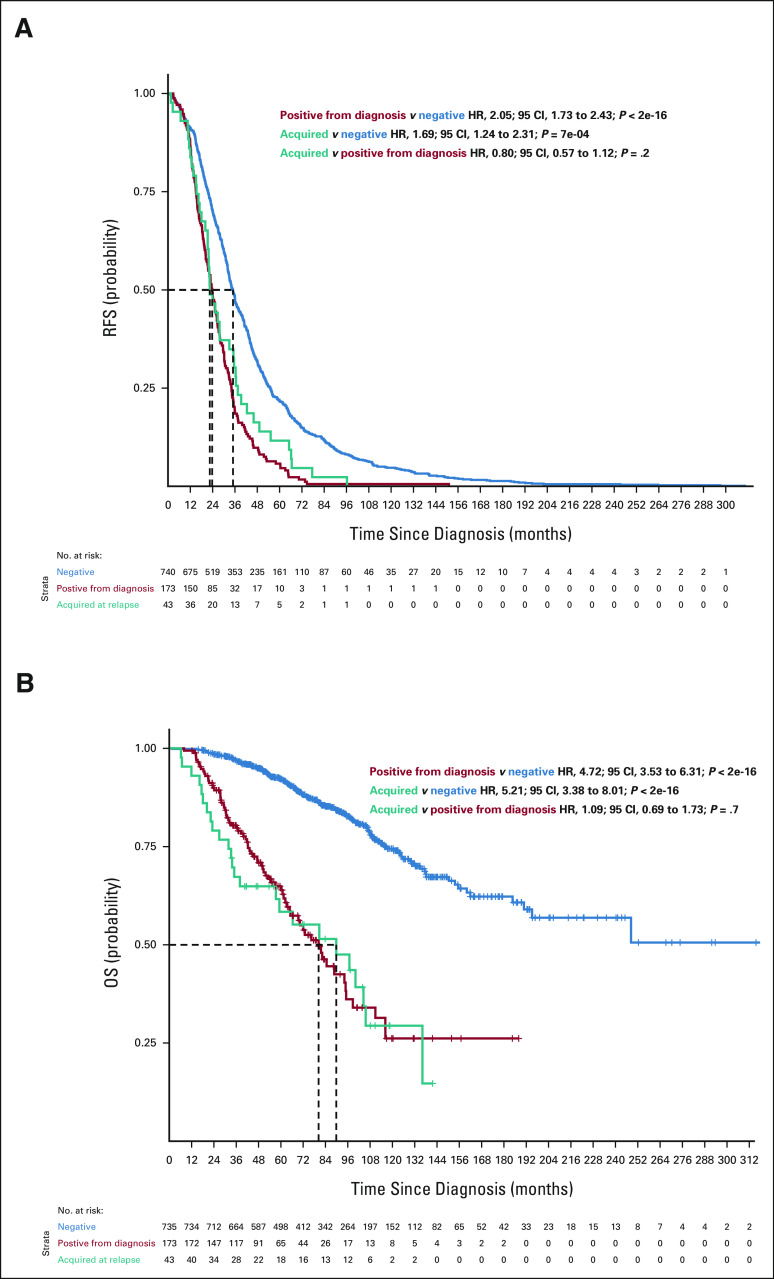

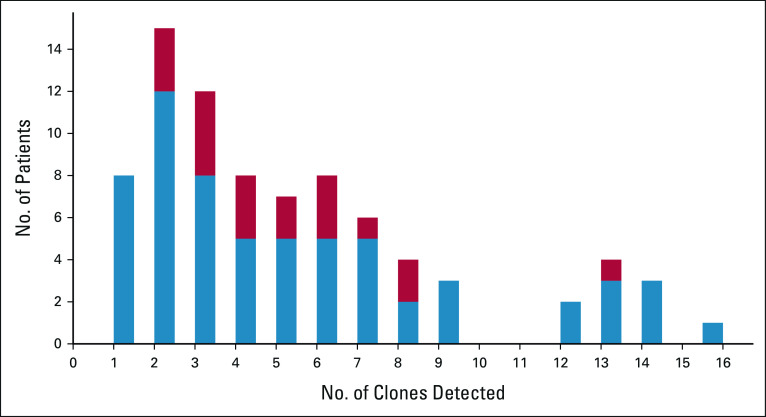

A total of 52,176 MM cells were analyzed. Seventy-four patients (91%) had 2-16 subclones. Among these patients, 28.7% had a subclone with high-risk features (del(17p), del(1p32), and 1q gain) at diagnosis. In a patient with a subclonal 1q gain at diagnosis, we analyzed the diagnosis, postinduction, and first relapse samples, which showed a rise of the high-risk 1q gain subclone (16%, 70%, and 92%, respectively). In our clinical database, we found that the 1q gain frequency increased from 30.2% at diagnosis to 43.6% at relapse (odds ratio, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.58 to 2.00). We subsequently performed survival analyses, which showed that the progression-free and overall survival curves were superimposable between patients who had the 1q gain from diagnosis and those who seemingly acquired it at relapse. This strongly suggests that many patients had 1q gains at diagnosis in microclones that were missed by bulk analyses.

CONCLUSION

These data suggest that identifying these scarce aggressive cells may necessitate more aggressive treatment as early as diagnosis to prevent them from becoming the dominant clone.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by the accumulation of tumor plasma cells (MM cells), usually within the bone marrow. Although we have achieved impressive survival improvements in the past 20 years thanks to novel therapies, the course of the disease is marked by successive relapses, unfortunately leading to death in 5-10 years.1 However, these medians of survival hide a profound heterogeneity; some patients may be considered cured, whereas others die within 2-3 years. The main predictive parameter of the evolution of patients lies in the huge heterogeneity of the genetic abnormalities observed within tumor cells. Numerous chromosomal abnormalities have been associated with prognosis, but very few (apart from trisomies 52 and 93) have a favorable outcome. The loss of chromosomal regions 17p134 and 1p325 and the gain of the long arm of chromosome 1 (1q gain)6 are among the copy number abnormalities (CNAs) associated with shorter survival. Chromosome 1q amplifications (amp1q, more than three copies) may induce an even worse prognosis than a gain (three copies).7 Many of these abnormalities are considered secondary and thus acquired during the course of the disease. Although they can be observed at diagnosis, sometimes, they are only detected at relapse(s), but this may be influenced by our ability to sensitively detect their existence. MM is a molecular subclonal disease, made up of different subclones of varying cell population sizes.8-10 As in other cancers, these different subclones can vary in proportion among the different stages, suggesting that an unnoticed minor subclone at diagnosis could become the dominant clone at the time of relapse. However, current technologies are not able to detect these micro-subclones at the bulk level.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Our main objective is to investigate how often so-called secondary chromosomal abnormalities are present at diagnosis and missed by conventional testing methods.

Knowledge Generated

Using single-cell technology, we show that many high-risk abnormalities are actually detectable in micro-subclonal populations at diagnosis. We then confirmed that, at least for 1q gains, the presence of a high-risk subclone affects prognosis at a similar magnitude as clonal 1q gains at diagnosis.

Relevance (S. Lentzsch)

-

Detecting micro-subclonal populations, including high-risk subclones at diagnosis, warrants adequate and novel approaches for upfront treatment.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Suzanne Lentzsch, MD, PhD.

Although clonal heterogeneity has been largely reported at the mutational level,11-13 little is known about this phenomenon at the CNA level. Since certain CNAs are associated with a poor outcome, and assuming that they affect disease course, it would be clinically important to track the presence of these abnormalities in minor subclones from the time of diagnosis. Here, to our knowledge, we report the first analysis at the single-cell level of CNA in tumor cells from 81 patients with MM analyzed at diagnosis, relapse, or presymptomatic stages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients in Single-Cell Study

Patients were enrolled on the basis of the availability of viable frozen MM cells. All patients signed an informed consent form, allowing research on their samples, and the study has been accepted by the Toulouse Ethics committee. Eighty-one patients were enrolled (32 females and 49 males). Sixty-six patients had samples taken at the time of diagnosis of symptomatic MM, nine were at relapse, and six were in presymptomatic stages, namely, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) or smoldering MM (SMM; Appendix Table A1, online only). In addition, two patients who had diagnostic samples available had additional samples available at the end of induction therapy and one patient had a third sample taken at relapse. Patient characteristics are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics for 81 Patients Profiled With Single-Cell DNA Sequencing, 5,052 Patients in the Diagnosis Database, and 1,610 Patients in the Relapse Database

Cell Sorting

Plasma cells were sorted from bone marrow with automated magnetic sorting targeting CD138+ cells (autoMACS and anti-CD138 beads from Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Supernatants were removed, and pellets were frozen at –80°C before DNA isolation. DNA was then isolated with a NucleoSpin Tissue, Mini kit for DNA from cells and tissue (Macherey Nagel, Duren, Germany), and up to 200 ng of DNA was used for library preparation with the SureSelect XT Low Input kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Custom baits were used for the hybridization (3.3 Mb), and then targeted libraries were pooled at equimolar concentrations and sequenced on a NextSeq500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

For single-cell analyses, cells were either frozen in dimethyl sulfoxide 10% solution and stored at –80°C or washed and immediately used. For postinduction analyses, whole fresh bone marrow was stained with three fluorescent mouse antibodies: CD138-V450 (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), CD38F2-FITC (CliniSciences, Nanterre, France), and Fixable Viability Stain-780 (Becton Dickinson). After red blood cell lysis (BD FACs Lysing solution-1X, Becton Dickinson), cells were washed with a Cell Wash Buffer (Becton Dickinson), gently homogenized, and centrifuged (300g speed). Cell pellets were then resuspended in dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline 1× at approximately 5 million cells/mL, and viability was assessed with Trypan Blue 0.4%. Cells were then sorted using a Melody FACS sorter (Becton Dickinson). After doublet exclusion, the CD38+/CD138+ population was sorted from dead cells (FVS-780–positive) into a well containing approximately 70 µL of dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline 1× bovine serum albumin 0.04% buffer.

Single-Cell DNA Sequencing

A median of 6,000 cells per sample (range, 1,176-9,996) were encapsulated using the 10× Chromium controller (10× Genomics, Pleasanton, CA), according to the Chromium Single-Cell DNA User Guide (10× Genomics). After barcoding, Illumina adapters were added during ligation, and a final sample index polymerase chain reaction was performed. The libraries' quality was assessed using a TapeStation 2200 (Agilent), and they were frozen before quantitation and sequencing. Overall, barcoding was performed on two levels: cell barcodes to allow attribution of each sequence read to its cell of origin and indexing to allow pooling of different samples. Single-cell DNA-seq libraries were quantified with HSD1000 reagents on the TapeStation 2200 system (Agilent) and pooled at equimolar concentrations within 200-700 bp. For samples taken at the time of diagnosis, presymptomatic stages, or relapse, library pools were quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction with the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina and loaded at 300 pM plus 1% phiX on a NovaSeqS4 6000's lane. For samples taken at the time of induction, library pools were sequenced at 1.7 pM plus 1% phiX using a NextSeq 500 sequencer. Sequencing was configured to the paired end at 2 × 150 cycles plus eight cycles for a single index. A sequencing depth of 750,000-1,500,000 reads per cell was expected to reach a resolution of 2 Mb (in many samples, InDels shorter than 2 Mb were successfully detected). Data were demultiplexed using the Cell Ranger DNA mkfastq command. Reads were aligned to human reference genome hg38. Cells were called, and copy numbers were estimated using the Cell Ranger DNA cnv command with default options. Cells marked as noisy were discarded. Cells with gain 1q were split and clustered apart. Cells were clustered using the hierarchical clustering function from the SciPy14 python library with Canberra distance and average linkage. CNA figures were created using matplotlib.15 We arbitrarily defined a subclone as at least 10 cells having the same CNA to avoid patients with possible false-positive results.

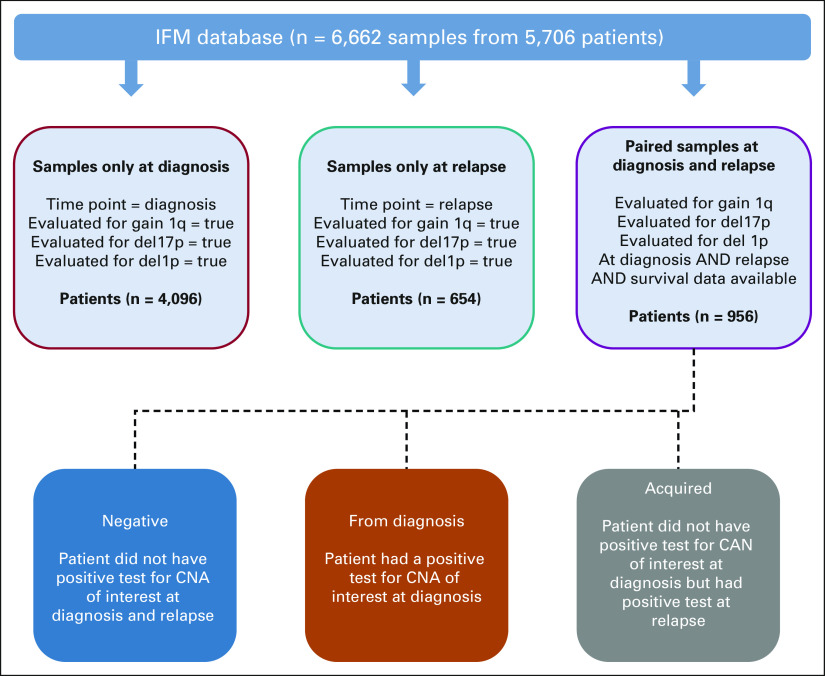

Patient Database and Survival Analyses

We used the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) patient database for outcome analysis. Patients with MM diagnosed and treated within the IFM network in France and profiled with either targeted sequencing or fluorescence in situ hybridization test for translocations and copy number abnormalities between 1990 and 2021 are recorded in this database. A total of 5,052 newly diagnosed patients with MM and 1,610 patients with first relapse have been identified with required cytogenetic data (tested for chr1q gain, del(17p), and del(1p)). Clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. For the acquired genomic abnormalities, we used data from 956 patients who had been tested for high-risk CNA events at diagnosis and first relapse (gain1q, del17p, and del1p) and whose survival data were available (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Five patients were excluded from overall survival (OS) because of missing data. Patients who did not have CNA information available at both time points or who had not had a relapse at the time of study were excluded from survival analysis. Patients who had a CNA of interest (eg, gain 1q) at diagnosis and relapse were included in the from diagnosis group, and patients with a CNA only detected at relapse were included in the acquired group. All other patients who were negative for the CNA of interest at diagnosis and relapse were in the negative group. Survival analyses were performed using the R survival and survminer packages, and Kaplan-Meier plots were created using the ggsurvplot function. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI were calculated with the coxph function, and P values were calculated using a log-rank test. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to the earliest disease relapse as determined by clinicians (events). Because only patients who had data available at diagnosis and relapse were evaluated, no censoring occurred for RFS. OS was computed as the time from diagnosis to death or censored at the last news.

RESULTS

A total of 52,176 single MM cells from 81 patients were analyzed. The number of analyzed tumor cells varied from patient to patient because of heterogeneity in the sample cellularity and variability in the cell capture rate, but the mean number of analyzable cells was 656 per patient (range, 83-5,192). In these 81 patients, at least one subclone was detected in 74 of them (91%; Fig 1), with the remaining patients likely having too few analyzed cells to detect a subclone, given their homogeneity (mean = 624 cells).

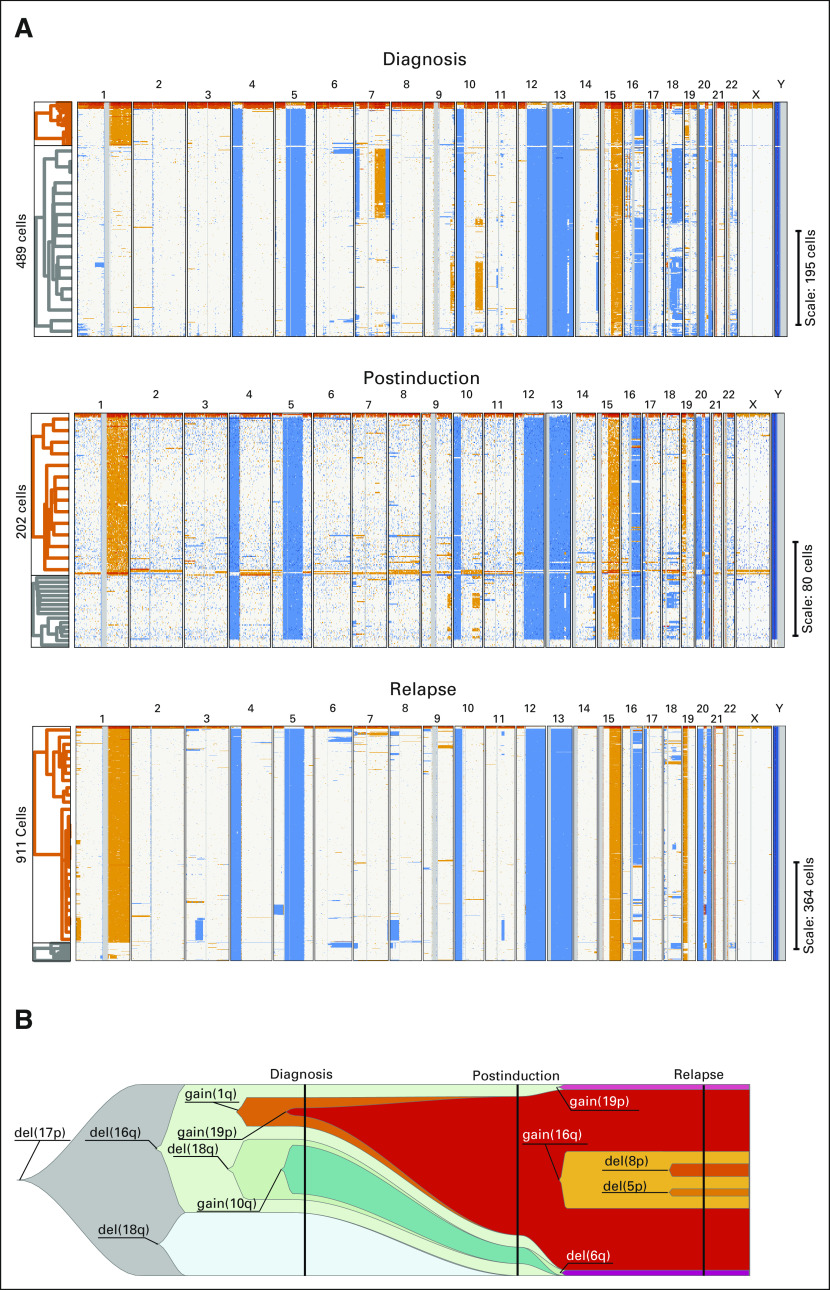

FIG 1.

(A) Single-cell CNA plots for patient #T19979. Each line represents CNA for a single cell. Blue represents losses, and orange represents gains. The samples at diagnosis, after induction, and at relapse are shown from top to bottom, respectively. Hierarchical clustering is shown to the left of each panel. Orange represents 1q gain cells, and gray represents other cells. At diagnosis, 1q gain was observed in 16% of the single plasma cells versus 70% after induction chemotherapy and 92% at relapse. (B) Fish plot of the inferred clonal evolution on the basis of single-cell CNA data (clonal evolution). A fish plot is a schematic of tumor evolution along the horizontal axis, where a clone is represented by a specific colored shape and nested clones indicate a descent relationship. For each clone, one anomaly that differentiates it from its precursor is displayed. For clarity, only a subset of clones is included. The vertical line highlights sampling points at diagnosis, postinduction, and relapse. At diagnosis, the diploid CNA profile was undetectable, and all cells have a del(17p); thus, this anomaly was inferred as an early event. 1q gain was present in subclones representing 9% of the cells, hence not detectable by standard diagnostic methods. After induction, 1q gain subclones represented the majority of cells and, at relapse, most of the cells. Clones were manually curated. The fish plot figure was created using the fishplot package for R.16 CNA, copy number abnormality.

High-Risk Subclones May Be Missed by Routine Testing

We focused our analysis on the established high-risk CNAs that predict survival, namely, losses of the 17p13 region (ie, del(17p13)), losses of the 1p32 region (ie, del(1p32)), and gains of the long arm of chromosome 1 (1q gains). In this cohort, we found a subclonal high-risk CNA that was not detected in the routine assessment in 19 patients (23.5%): eight (9.9%) patients with a 1q gain subclone, three patients with an amp1q subclone (3.7%), six (7.4%) patients with a del(1p32) subclone, and two patients (2.5%) with a del(17p13) subclone. We observed these high-risk subclones only in patients at diagnosis of symptomatic MM (not in presymptomatic or relapsed patients), which means that 28.7% (95% CI, 18.3 to 41.25) of patients with newly diagnosed MM harbored a high-risk subclone not detectable by routine assessment (Appendix Fig A2, online only). Of note, the amp1q subclones occurred only in patients who already had 1q gain, suggesting a two-step process.

In addition, we analyzed additional samples from two patients at the end of induction therapy (four bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone courses). One patient had no high-risk subclones at diagnosis or postinduction (patient with clonal hyperdiploidy, data not shown). The second patient had a 1q gain subclone at diagnosis (16% of the analyzed cells) that was not detected in the routine assessment. At postinduction (thus before high-dose melphalan and autologous stem-cell transplantation), 70% of the 202 analyzable tumor cells had this high-risk feature, and at relapse (18 months after diagnosis), 92% of the cells harbored the 1q gain (Fig 1).

Survival Impact of CNA Risk Events Not Detected at Diagnosis

To investigate whether the presence of these high-risk subclones at diagnosis affects patient outcomes, we used the IFM patient database (paired newly diagnosed and first relapse samples from 956 patients), which records information on both high-risk genotypes and patient survival. First, we found that 1q gains are observed in 18.09% of patients (173 of 956) at the time of diagnosis, using routine assessments, but are present in 22.6% of patients at relapse (216 of 956, McNemar's test P value < .001), which is a difference of 4.5% and of a similar magnitude of patients we found who had subclonal 1q gains. Similarly, deletions of 17p13 (observed in > 55% of the malignant plasma cells and observed in > 55% of the malignant plasma cells) were observed in 5.3% of patients at diagnosis but in 9.3% of the patients at relapse (McNemar's test P value < .001). Finally, deletion of 1p32 was observed in 5.4% of the patients at diagnosis but in 7.3% of the patients at relapse (McNemar's test P value < .001). These increasing frequencies from diagnosis to relapse combined with our single-cell data suggest that clonal selection occurs on minor subclones already present at diagnosis, rather than de novo gain of high-risk subclones after diagnosis.

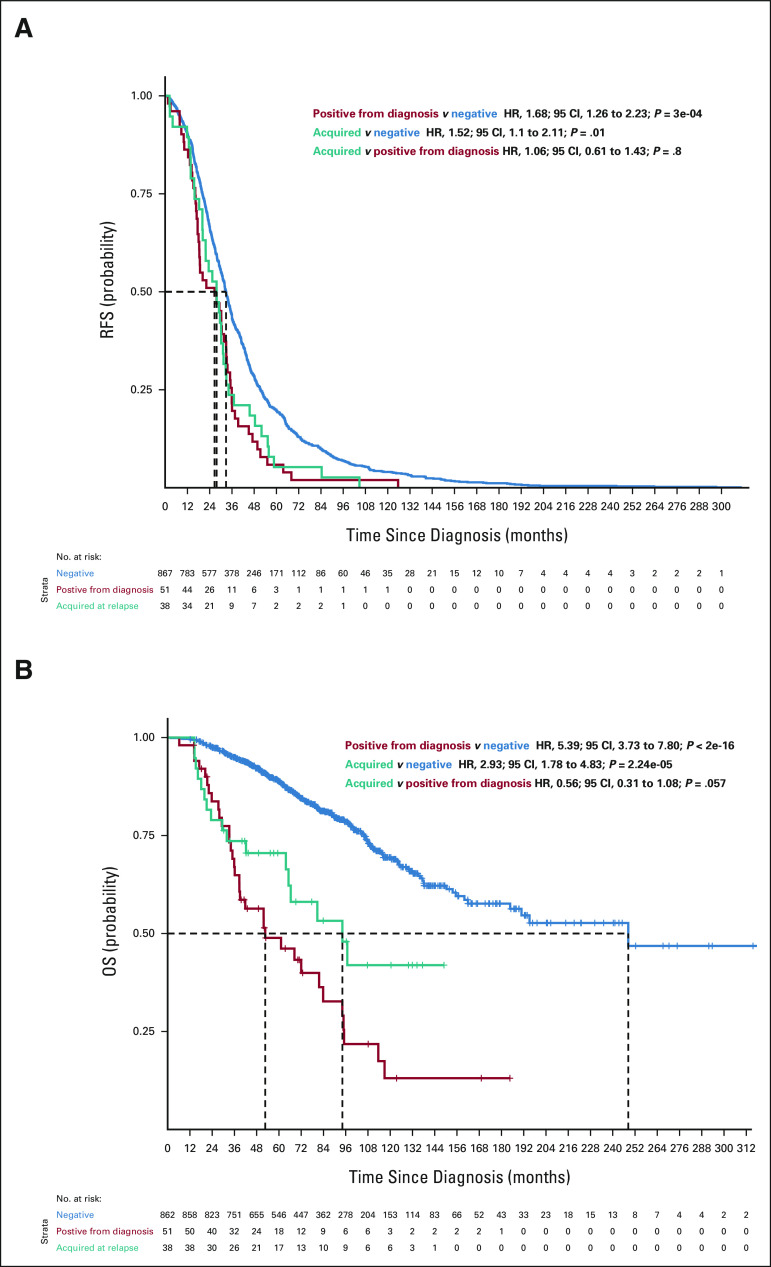

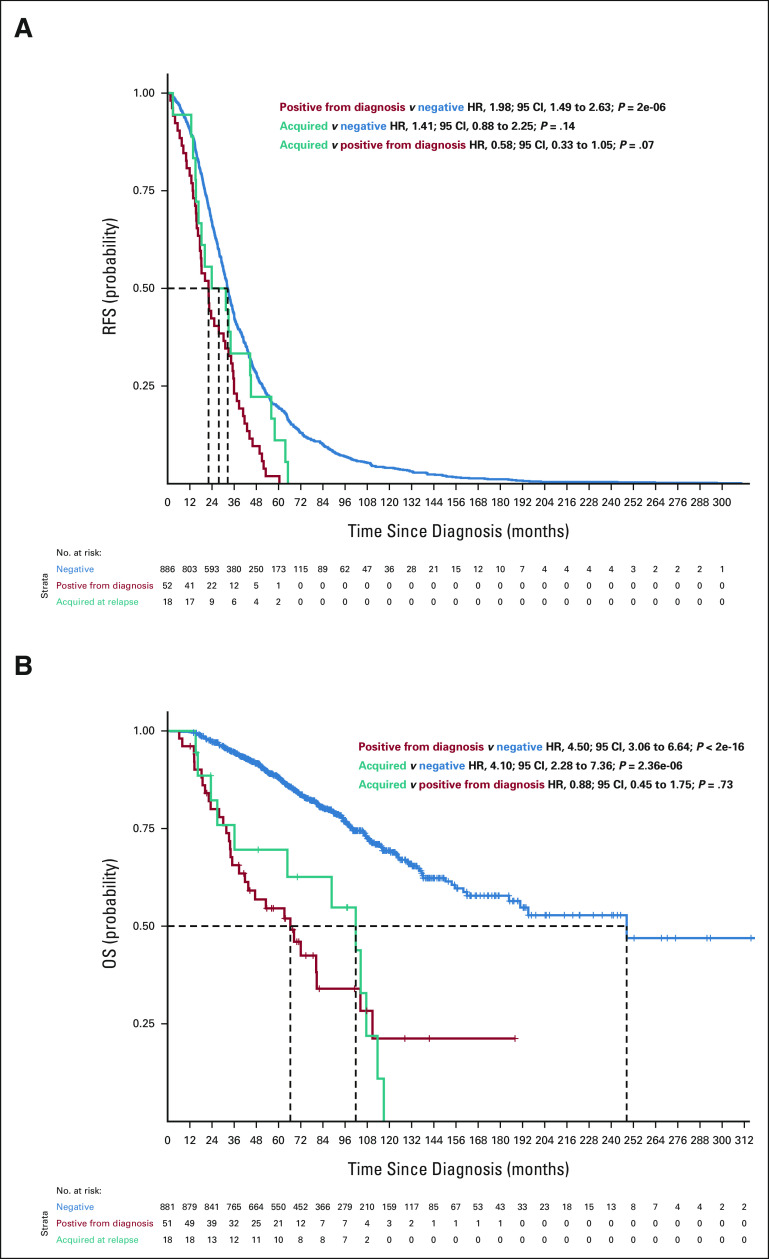

To further investigate this, we compared the survival of patients who had a high-risk subclone detectable by routine assessment at diagnosis with those who only had it in the first relapse and who did not have it at any time point. For 1q gain, the RFS and OS curves were superimposable between patients who had 1q gain from diagnosis and those who acquired it at relapse (RFS: acquired v positive from diagnosis HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.12; P = .2 and OS: acquired v positive from diagnosis HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.73; P = .7), suggesting that the high-risk subclone was present at diagnosis and likely expanded to detectable levels before relapse (Fig 2). For del(17p), the OS curves between these patient groups were not superimposable. Furthermore, having this CNA only detectable at relapse had an intermediate effect (Appendix Fig A3, online only; RFS: acquired v positive from diagnosis HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.61 to 1.43; P = .8 and OS: acquired v positive from diagnosis HR, 0.56; 95 CI, 0.31 to 1.08; P = .057), indicating that the size of the clonal population may influence the outcome for del17p. For patients with del(1p32), only 18 patients had it at the time of relapse, and the results were similar to the other two high-risk categories (Appendix Fig A4, online only).

FIG 2.

(A) RFS (n = 956) and (B) OS (n = 951) curves for patients according to 1q gains detected in the bulk analysis (chr1q gain). Blue curves show survival probability (y-axis) for patients with no 1q gain detected at diagnosis or at relapse. The red curve represents survival probability for patients with 1q gain detected at diagnosis, and the teal curve shows survival probability for patients with 1q gain detected only at relapse but not at diagnosis. HR, 95% CIs, and P values for group comparisons are given at the top right. The number of patients at risk for a given month since diagnosis (x-axis) is shown at the bottom. HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing patients with MM at the single-cell level for copy number abnormalities. In MM, the current oncogenetic model is based on two different genetic abnormalities: hyperdiploidy (observed in 55% of patients) and 14q32 translocations involving the IGH gene (found in about 45% of the patients). All other genetic changes, such as del(13q), 1q gains, del(17p), or del(1p32), are considered secondary events that occur during the course of the disease. However, MM is a heterogeneous malignancy, with some of the genetic/molecular changes (including some driver events such as KRAS or NRAS) being observed only in a subclonal fraction of the MM cells. This has also been demonstrated at the CNA level, but in smaller cohorts and not directly at the single-cell level. Furthermore, the major clone(s) observed at the time of relapse(s) can be different from the one(s) observed at diagnosis because of clonal selection. In the current study, we evaluated CNA clonal heterogeneity to investigate whether high-risk CNA features are acquired during the evolution of the disease or are present at diagnosis in micro-subpopulations and selected by or during treatment.

Using single-cell analyses, we showed that CNA subclonality is a general process in MM, observed in 91% of the 81 patients, including the six presymptomatic individuals. In the seven patients lacking detectable heterogeneity in CNA, six had a 14q32 translocation (three t(4;14), two t(11;14), and one t(14;20)) and a single patient had hyperdiploidy. The analysis of a larger number of single cells might have identified subclonality; however, further studies are required to decipher the clonal structure in these subgroups.

Among patients with subclonal CNAs, a high-risk CNA subclone (defined by the presence of del(17p), del(1p32), and 1q gain or amplification) was identified in 28.7% of them, two with del(17p), six with del(1p32), and 11 with 1q gain or amplification at diagnosis. None of the six patients in presymptomatic stages had a high-risk subclone, but further studies are needed on larger cohorts to confirm an association. In one of the two patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic MM with longitudinal data taken at diagnosis, after four cycles of induction therapy and at relapse, we observed a 1q gain subclone at diagnosis (16% of the MM cells) with a significant increase in the frequency of this subclone after induction (70% of the analyzed MM cells). This patient then presented an early relapse, 18 months after diagnosis, with a further increase in the frequency of the 1q gain subclone (92% of the MM cells). This single example favors the hypothesis of an early clonal selection of the high-risk subclone conferring resistance to therapy.

To validate this hypothesis, we interrogated a pre-existing IFM patient database for the frequency of high-risk features at diagnosis and at relapse, obtained by routine assessment. For 1q gains, we observed a significant increase in the frequency between diagnosis and relapse. In our single-cell data, 1q subclones (not detectable in bulk analyses) were observed in 12% of the patients with newly diagnosed MM. These concordant data favor the hypothesis that the clone existed at diagnosis and was clonally selected to detectable levels, rather than a true acquisition during the course of the disease. To validate our hypothesis, we looked for patients who would have been analyzed for 1q at diagnosis and at relapse and who displayed a normal 1q at diagnosis and a 1q gain at relapse. When compared with patients with 1q gain at diagnosis and treated with similar schemas, we observed overlapping RFS and OS curves. This observation supports an early impact of 1q gains on the course of the disease, probably through an early increase of the 1q gain subclone. The deleterious prognostic impact of acquired 1q gain has been confirmed in a recent paper from the UK group.17 Importantly, among newly diagnosed patients for whom we detected the 1q gain subclone, half of them were stratified as low risk in routine assessment. These discrepancies could partially explain why some patients without known high-risk features at diagnosis relapse and die early.18

We had similar observations for del(17p) and del(1p) patients as well. Patients displaying del17p only at relapse had an intermediate outcome (Appendix Fig A3). This result agrees with our previous observation that del(17p) displays a prognostic impact only when present in the major cell clonal fraction (> 55%),4 and a recent study showed that patients with acquired del17p have similar outcomes as patients with del17p at diagnosis.19 However, given the recent data about the prognostic impact of biallelic inactivation of TP53,7,20 we believe that without TP53 mutational status, the interpretation of the data is uncertain.

In conclusion, our study suggests that high-risk CNAs are not acquired after diagnosis but are present at diagnosis and selected by the treatment. The definitive demonstration of the impact of these high-risk subclones on disease evolution will come from the analysis of relapse samples. These findings might have implications in the definition of high-risk patients and patient management by informing the first-line therapeutic strategy to prevent the clonal selection of these aggressive subclones. More studies are needed to explore this phenomenon in other malignant diseases or premalignant stages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We especially thank Antoine GRAFFEUIL and Corentin Pignon for excellent technical expertise.

APPENDIX

FIG A1.

A workflow for the IFM patient database investigation. Five thousand fifty-two patients at diagnosis fulfilling the criteria listed in the red box and 1,610 patients fulfilling the criteria listed in the teal box were selected from the IFM database. Nine hundred fifty-six patients who had data at diagnosis and relapse and who fulfilled the criteria listed in the purple box were divided into three groups, given at the bottom, on the basis of the criteria listed in each box. IFM, Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome.

FIG A2.

Distribution of the number of subclones for the 81 patients (the x axis represents the subclone numbers, and the y axis the number of patients). In blue, patients with no high-risk subclones are given, and in red, patients with at least one high-risk subclone are given.

FIG A3.

(A) RFS and (B) OS curves for patients according to del(17p) detected in the bulk analysis. Blue curves show survival probability (y-axis) for patients with no del(17p) detected at diagnosis or at relapse. The red curve represents survival probability for patients with del(17p) detected at diagnosis, and the teal curve shows survival probability for patients with del(17p) detected only at relapse but not at diagnosis. HR, 95% CIs, and P values for group comparisons are given at the top right. The number of patients at risk for a given month since diagnosis (x-axis) is shown at the bottom. HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

FIG A4.

(A) RFS and (B) OS curves for patients according to del(1p) detected in the bulk analysis. Blue curves show survival probability (y-axis) for patients with no del(1p) detected at diagnosis or at relapse. The red curve represents survival probability for patients with del(1p) detected at diagnosis, and the teal curve shows survival probability for patients with del(1p) detected only at relapse but not at diagnosis. HR, 95% CIs, and P values for group comparisons are given at the top right. The number of patients at risk for a given month since diagnosis (x-axis) is shown at the bottom. HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

TABLE A1.

Summary of Patients and Single-Cell Copy Number Abnormality Sequencing Data

Aurore Perrot

Honoraria: Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi, Amgen, Janssen, Takeda, Celgene

Marion Divoux

Employment: Takeda, Pfizer

Xavier Leleu

Honoraria: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda, Sanofi, AbbVie, Merck, Roche, Karyopharm Therapeutics, CARsgen Therapeutics, Oncopeptides, GlaxoSmithKline

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, Takeda, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Roche, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Oncopeptides, CARsgen Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Takeda

Salomon Manier

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Adaptive Biotechnologies (Inst), Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst)

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst)

Didier Adiko

Honoraria: IQVIA

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen

Frederique Orsini-Piocelle

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene

Margaret Macro

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Amgen, Takeda

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst), Janssen Medical Affairs (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Takeda, Janssen Oncology, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag

Mohamad Mohty

Honoraria: Celgene, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Takeda, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, MaaT Pharma, Novartis, Xenikos, Adaptive Biotechnologies, GlaxoSmithKline

Speakers' Bureau: Janssen, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Sanofi (Inst), Roche (Inst), Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Nikhil Munshi

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoPep, C4 Therapeutics, Raqia

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, Janssen, OncoPep, AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, BeiGene, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Legend Biotech, Novartis, Sebia, Raqia

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: OncoPep

Jill Corre

Honoraria: Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi, Takeda

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Sanofi

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by a grant from the Riney Foundation, a NIH PO1 grant (NCI P01-155258), a NIH SPORE grant (NCI 5P50CA100707), and the Fondation ARC.

R.L. and M.S. are cofirst authors. J.C. and H.A.-L. are colast authors.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

All deidentified single-cell CNA data are accessible from https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FT1ZGK

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Celine Mazzotti, Titouan Cazaubiel, Xavier Leleu, Mohamad Mohty, Nikhil Munshi, Jill Corre, Hervé Avet-Loiseau

Financial support: Nikhil Munshi, Hervé Avet-Loiseau

Administrative support: Nikhil Munshi, Hervé Avet-Loiseau

Provision of study materials or patients: Aurore Perrot, Marion Divoux, Xavier Leleu, Didier Adiko, François Lifermann, Sabine Brechignac, Didier Bouscary, Margaret Macro, Mohamad Mohty, Hervé Avet-Loiseau

Collection and assembly of data: Aurore Perrot, Celine Mazzotti, Marion Divoux, Xavier Leleu, Marie-Lorraine Chretien, Didier Adiko, Frederique Orsini-Piocelle, François Lifermann, Sabine Brechignac, Lauris Gastaud, Didier Bouscary, Margaret Macro, Jill Corre

Data analysis and interpretation: Romain Lannes, Mehmet Samur, Aurore Perrot, Xavier Leleu, Anaïs Schavgoulidze, Salomon Manier, Alice Cleynen, Nikhil Munshi, Jill Corre

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

In Multiple Myeloma, High-Risk Secondary Genetic Events Observed at Relapse are Present From Diagnosis in Tiny, Undetectable Subclonal Populations

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Aurore Perrot

Honoraria: Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi, Amgen, Janssen, Takeda, Celgene

Marion Divoux

Employment: Takeda, Pfizer

Xavier Leleu

Honoraria: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda, Sanofi, AbbVie, Merck, Roche, Karyopharm Therapeutics, CARsgen Therapeutics, Oncopeptides, GlaxoSmithKline

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, Takeda, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Roche, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Oncopeptides, CARsgen Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Takeda

Salomon Manier

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Adaptive Biotechnologies (Inst), Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst)

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst)

Didier Adiko

Honoraria: IQVIA

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen

Frederique Orsini-Piocelle

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene

Margaret Macro

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Amgen, Takeda

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst), Janssen Medical Affairs (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Takeda, Janssen Oncology, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag

Mohamad Mohty

Honoraria: Celgene, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Takeda, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, MaaT Pharma, Novartis, Xenikos, Adaptive Biotechnologies, GlaxoSmithKline

Speakers' Bureau: Janssen, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Sanofi (Inst), Roche (Inst), Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Nikhil Munshi

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: OncoPep, C4 Therapeutics, Raqia

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, Janssen, OncoPep, AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, BeiGene, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Legend Biotech, Novartis, Sebia, Raqia

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: OncoPep

Jill Corre

Honoraria: Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi, Takeda

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Sanofi

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palumbo A, Anderson K: Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 364:1046-1060, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perrot A, Lauwers-Cances V, Tournay E, et al. : Development and validation of a cytogenetic prognostic index predicting survival in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 37:1657-1665, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samur MK, Aktas Samur A, Fulciniti M, et al. : Genome-wide somatic alterations in multiple myeloma reveal a superior outcome group. J Clin Oncol 38:3107-3118, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakurta A, Ortiz M, Blecua P, et al. : High subclonal fraction of 17p deletion is associated with poor prognosis in multiple myeloma. Blood 133:1217-1221, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebraud B, Leleu X, Lauwers-Cances V, et al. : Deletion of the 1p32 region is a major independent prognostic factor in young patients with myeloma: The IFM experience on 1195 patients. Leukemia 28:675-679, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt TM, Fonseca R, Usmani SZ: Chromosome 1q21 abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J 11:83-90, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker BA, Mavrommatis K, Wardell CP, et al. : A high-risk, Double-Hit, group of newly diagnosed myeloma identified by genomic analysis. Leukemia 33:159-170, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan GJ, Walker BA, Davies FE: The genetic architecture of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Cancer 12:335-348, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egan JB, Shi CX, Tembe W, et al. : Whole-genome sequencing of multiple myeloma from diagnosis to plasma cell leukemia reveals genomic initiating events, evolution, and clonal tides. Blood 120:1060-1066, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magrangeas F, Lode L, Wuillleme S, et al. : Genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 19:191-194, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, et al. : Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature 471:467-472, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolli N, Avet-Loiseau H, Wedge DC, et al. : Heterogeneity of genomic evolution and mutational profiles in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun 5:2997-3007, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Carter SL, et al. : Widespread genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma: Implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Cell 25:91-101, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, et al. : SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods 17:261-272, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter JD: Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput Sci Eng 9:90-95, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller CA, McMichael J, Ha XD, et al. : Visualizing tumor evolution with the fishplot package for R. BMC Genomics 17:1-3, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croft J, Ellis S, Sherborne AL, et al. : Copy number evolution and its relationship with patient outcome—an analysis of 178 matched presentation-relapse tumor pairs from the Myeloma XI trial. Leukemia 35:2043-2053, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corre J, Montes L, Martin E, et al. : Early relapse after autologous transplant for myeloma is associated with poor survival regardless of cytogenetic risk. Haematologica 105:480-483, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakshman A, Painuly U, Rajkumar SV, et al. : Impact of acquired del(17p) in multiple myeloma. Blood Adv 3:1930-1938, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corre J, Perrot A, Caillot D, et al. : Del17p without TP53 mutation confers poor prognosis in intensively treated newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Blood 137:1192-1195, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All deidentified single-cell CNA data are accessible from https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FT1ZGK