Abstract

Introduction:

Vitamin D is involved in the activation of innate and adaptive immunity. In the epidermis, vitamin D is involved in the differentiation and maturation of keratinocytes. A fall in the vitamin D levels can activate auto-immunity.

Aims and Objectives:

This study was aimed at correlating the serum vitamin D level of psoriasis patients with disease severity.

Materials and Methods:

This case-control study included 50 newly diagnosed cases of psoriasis (group A) and 50 controls (group B). Serum vitamin D levels were assessed in both groups. The levels were correlated with the duration of disease, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) level.

Results:

Psoriasis patients had significantly lower vitamin D levels than controls. There was a significant negative correlation between serum vitamin D level and disease duration, PASI score, and ESR level (p-value <0.001). Rising age and female gender were also associated with significantly lower vitamin D.

Conclusion:

We found a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in psoriatic patients. The level is strongly associated with every aspect of disease severity. Its level can predict the course of disease and prognosis.

Keywords: Disease severity, PASI, psoriasis, vitamin D level

Introduction

Psoriasis is an auto-inflammatory papulosquamous dermatosis with auto-inflammatory pathogenesis. The disease is characterised by dysregulation in innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and keratinocyte differentiation.[1]

Traditionally, vitamin D was considered to be responsible for just the metabolism of calcium and phosphorus. However, lately, its role has been realised as a multi-dimensional key player in the immune regulation throughout our body. Several tissues possess receptors for vitamin D and CYP271B (the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of 25-hydroxyvitamin D).[2,3]

Of late, vitamin D deficiency has been noted in several dermatological disorders including, but not limited to, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and connective tissue disorders.[4,5] Because vitamin D receptors are also present on the inflammatory infiltrates such as T-cells, B-cells and NK cells, vitamin D deficiency could be responsible for the unchecked upregulation of these cells in inflammatory disorders.

In the epidermis, vitamin D is responsible for increased differentiation and reduced proliferation of keratinocytes. Vitamin D also balances the secretion of cytokines. The role of vitamin D as a therapeutic agent in psoriasis is also based on its above-mentioned properties. However, it is still not clear whether vitamin D deficiency is an etiological factor of psoriasis or a consequence of unchecked disease activity. In this study, we aimed to investigate the association between vitamin D levels and psoriasis disease activity.

Materials and Methods

This case-control study included 100 subjects divided into 2 groups. Only immuno-competent subjects over the age of 18 years were included. Group A included patients with psoriasis, and group B included healthy volunteers (control group). Subjects for group A were recruited from the dermatology in-patient or out-patient department. Subjects from group B were healthy volunteers, who were attendants or relatives of patients admitted to our dermatology in-patient department for any other dermatosis. The controls were age- and sex-matched with the cases.

Detailed demographic and clinical data of cases were recorded in a pre-structured proforma. Special emphasis was given to the patient's job (indoor/outdoor) and the menopausal status as both parameters may influence the level of vitamin D.

In group A, the duration of psoriasis, disease severity according to psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), the nail psoriasis severity index (NAPSI), and treatment history were also recorded. PASI scores were graded as mild (PASI <7), moderate (PASI 7–12), and severe (PASI >12).

Patients having any concomitant infection, chronic inflammatory disease, primary or iatrogenic immuno-suppression, or malignancy were excluded. Additionally, patients receiving any medication which could influence the level of vitamin D in the body, namely, systemic steroids, bisphosphonates, systemic corticosteroids, calcium supplements, or vitamin D3 supplements were excluded. We also excluded psoriasis patients from treatment with phototherapy and/or topical vitamin D analogues. In order to avoid any differences in sun exposure and oral vitamin D intake in the diet, all study participants were from the same topographic region. Cases were subjected to routine investigations including haemogram, renal and liver profile, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) level.

These measurements included height, weight, and waist size. Body mass index (BMI) calculation was performed. An average of the two readings of blood pressure taken 5 minutes apart was noted. Fasting blood sugar (FBS), triglycerides (TAGs), and high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) were measured.

Serum vitamin D level

The serum 25(OH) vitamin D level was assessed using the electro-chemiluminescence assay technique from vitamin D kits. The level of vitamin D was graded as normal (>30 ng/dl), insufficient (20–30 ng/dl), and deficient (<20 ng/dl).

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Office Excel and SPSS version 23 were used to examine the data. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers, proportions, and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as ranges, means, and standard deviations. The distribution of the variables was evaluated using the Ladder of Powers test. The Chi-square test was used to compare how the category variables were distributed between the two groups. Unpaired T test was employed to compare quantitative continuous variables. Ethical approval obtained on 26 May 2021.

Results

Of the 50 subjects in group A, 21 had chronic plaque psoriasis, 17 had psoriatic arthritis, 9 had erythroderma, and 3 had pustular psoriasis. In group B there were 50 healthy controls. The clinic-epidemiological data in patients are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiological profile of patients

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age±SD (in years) | 44.3±12.6 | 46.8±12.3 |

| Male | 38 | 36 |

| Females | 12 | 14 |

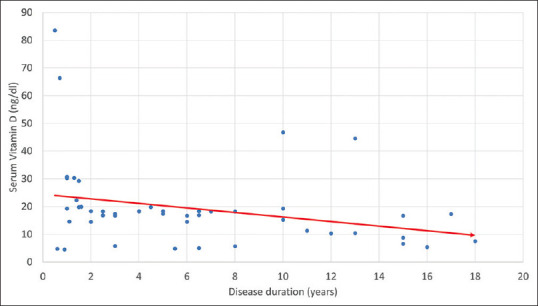

We found that serum vitamin D levels varied significantly among the two groups of subjects [Table 2]. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly lower vitamin D level than healthy controls (T score 6.557; P value <0.0001). Twenty-one (42%) of psoriasis patients were vitamin D-deficient, and 19 (38%) were vitamin D-insufficient [Table 2]. On the other hand, only 4 (8%) subjects from the control group were vitamin D-insufficient, whereas 3 (6%) were vitamin D-deficient. The value of relative risk was 5.7. This meant that psoriatic cases in our study were 5.7 times more likely to have a low vitamin D level than healthy controls. We also found a highly significant negative correlation between the duration of psoriasis and serum vitamin D level (r = -0.49, P value <0.001) [Figure 1].

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of serum vitamin D level between the two groups

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| Serum vitamin D level (in ng/ml) | 19.4±9.3 | 33.9±11.2 |

| Range | 4.8-83.6 | 10.6-91.8 |

P<0.0001

Figure 1.

Correlation of serum vitamin D level and disease duration

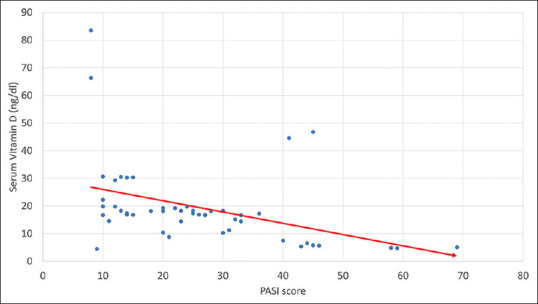

PASI score was used to grade the disease severity in group A. The mean PASI score of study participants was 25.09 ± 8.34. According to the PASI score, 16 (32%) cases had mild psoriasis, 22 (44%) had moderate psoriasis, and 12 (24%) had severe psoriasis. When we compared the disease activity with serum vitamin D levels, we observed that out of 22 cases with moderate disease, 20 had serum vitamin D3 levels lower than 20 ng/dl. However, all 12 cases with high disease activity had vitamin D levels less than 20 ng/dl. There was a significant association between low vitamin D levels and high disease activity (p-value was <0.00001) [Table 2]. We also correlated PASI with serum vitamin D level and found a highly significant negative correlation between PASI score and serum vitamin D level (r = -0.641; P value <0.0001) [Figure 2 and Table 3].

Figure 2.

Correlation of serum vitamin D level and PASI score

Table 3.

Correlation between serum vitamin D level and PASI score

| Disease Activity (according to PASI) | Serum Vitamin D (ng/dl) level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| <20 | 20-30 | >30 | |

| Mild (n=16) | 2 (4%) | 7 (14%) | 9 (18%) |

| Moderate (n=22) | 20 (40%) | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| High (n=12) | 12 (24%) | 0 | 0 |

Freeman–Halton extension of Fisher’s exact test. P<0.00001

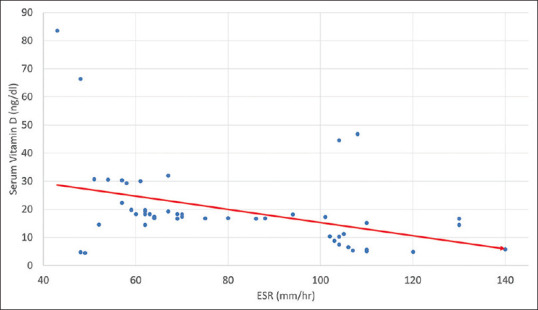

An analysis of ESR levels in group A revealed that 28 (56%) cases had raised ESR levels between 60 and 100 mm/hr (an indicator of inflammatory state), and 19 (38%) patients had even higher levels with ESR >100 mm/hr, whereas the remaining 7 (14%) cases had ESR below 60 mm/hr. There was a significant negative correlation between serum vitamin D level and ESR level (coefficient = -0.5859; P value is <.00001) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Correlation of serum vitamin D level and ESR level

We also divided the cases into two groups on the basis of co-morbidities. Cases fulfilling the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) criteria for metabolic syndrome were included in ‘group A1’, and those who did not have metabolic syndrome were included in ‘group A2’. A total of 17 (34%) cases belonged to group A1, and the remaining 33 (66%) belonged to group A2. We found that the serum vitamin D level was significantly lower in group A1 (15.8 ± 5.3 ng/ml) than in group B (21.3 ± 5.9 ng/ml) (p value 0.002).

The linear multiple regression model for our study participants revealed that serum vitamin D3 levels were influenced by age and gender (P value 0.001 and 0.04, respectively). In simpler terms, rising age and female gender were associated with significantly lower vitamin D values.

Discussion

To date, literature studies regarding the association between vitamin D status and psoriasis is still controversial. The initial observations by Orgaz-Molina et al. and Gisondi et al. showed that psoriasis patients have significantly lower vitamin D levels than healthy controls.[6,7] However, the studies that followed did not find any association.[8,9,10]

Multiple factors can influence the level of vitamin D including genetics, race, age, sun exposure, and dietary intake.[11] It is therefore imperative to tread on the side of caution while interpreting the data of different studies. In this study, the linear multiple regression analysis revealed that patient's advancing age and female gender were significant risk factors for lower serum vitamin D levels. The correlation coefficient also identified that there was a significant correlation between low serum vitamin D level and longer disease duration. A significant impact of disease duration on low vitamin D was also noted by Bergler-Czop et al.[12]

Multiple factors could be responsible for these findings. As a matter of fact, a low vitamin D level could be both a consequence or a cause of psoriasis, secondary to reduced sun exposure, anti-psoriatic drugs interfering with vitamin D metabolism (systemic steroids and immuno-suppressants), and low dietary absorption because of dermatogenic enteropathy.[13] Regardless of the cause, we found that psoriatic patients were 5.7 times more likely to have low vitamin D levels than healthy controls in our study.

Psoriasis patients tend to have a significantly lower ultra-violet exposure unless they are being treated with phototherapy. Often psoriasis patients tend to keep their skin covered because of the psychological distress associated with the disease. Over the course of years, this habit may significantly contribute to low vitamin D levels. Additionally, vitamin D is intrinsically involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Vitamin D levels have also been known to be reduced in Th-1- and Th-17-mediated pro-inflammatory conditions. Vitamin D poses an inhibitory or suppressive effect in various auto-immune diseases by means of receptors present on T-lymphocytes.[14] In fact, low vitamin D levels also make an individual susceptible to developing Th-1-driven auto-immune dermatosis. The role has been firmly established in rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, and multiple sclerosis.[14]

In the case of skin diseases, vitamin D is a key player in keratinocyte differentiation. Vitamin D promotes the growth of keratinocytes and prevents their pre-mature apoptosis. As far as the keratin fibres are concerned, Vitamin D modulates the expression of K1/K10 within the stratum spinosum. The expression of these two fibres is altered in psoriasis.[15,16] Vitamin D also normalises the distribution of integrin like CD26 and ICAM-1 over the dermo-epidermal junction, which get disrupted in psoriasis. To date, the relation between psoriasis disease duration and vitamin D level has not been studied extensively. In fact, ours is one of the very few studies to have found a significantly negative correlation between the two variables.

Metabolic syndrome is avidly associated with psoriasis. It may be responsible for high-fat deposits in the body, which can harbour the fat-soluble vitamin D, making it unavailable for the rest of the body. This could lead to poor bioavailability of vitamin D, thereby causing its deficiency.[17,18,19]

We also found a highly significant correlation between high ESR levels and low serum vitamin D levels in this study (p-value <0.001). ESR is one of the oldest acute phase reactants. A high ESR is attributed to an increase in the viscosity of blood and concentration of red blood cells. In psoriasis, just like most other inflammatory disorders, the albumin/globulin ratio gets tipped. This is also responsible for high plasma viscosity.

PASI is a tool that is used to measure the extent and severity of disease in psoriasis. We found an extremely significant correlation between PASI and serum vitamin D levels. The fact that these two parameters are so strongly associated further reinforces the fact that serum vitamin D deficiency is a key marker of disease activity in psoriasis. These findings also suggest that low-serum vitamin D also predicts a poor prognosis and a lack of response to treatment in psoriatic patients.

This study is perhaps one of its kind to successfully explore the association between low vitamin D levels and multiple markers of disease activity in psoriasis including the duration of disease, PASI, ESR, and increasing age. Although our study had a few limitations, namely, a small sample size and a lack of follow-up post-treatment, our findings strongly favour the utilisation of serum vitamin D3 levels as both a diagnostic and prognostic marker for psoriasis disease progression.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found a high prevalence of serum vitamin D deficiency in psoriatic patients. The levels of vitamin D are very strongly related to every aspect of psoriatic disease severity. Vitamin D supplements should be prescribed to every psoriasis patient. The administration of vitamin D early during the course of the disease can also aid in the prevention of skeletal involvement in psoriasis patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1475. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick MF. Vitamin D and bone health. J Nutr. 1996;126:1159S–64S. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.suppl_4.1159S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LoPiccolo MC, Lim HW. Vitamin D in health and disease. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2010;26:224–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2010.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solak B, Dikicier BS, Celik HD, Erdem T. Bone mineral density, 25-OH vitamin D and inflammation in patients with psoriasis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2016;32:153–60. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hambly R, Kirby B. The relevance of serum vitamin D in psoriasis: A review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:499–517. doi: 10.1007/s00403-017-1751-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisondi P, Rossini M, Di Cesare A, Idolazzi L, Farina S, Beltrami G, et al. Vitamin D status in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:505–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orgaz-Molina J, Buendía-Eisman A, Arrabal-Polo MA, Ruiz JC, Arias-Santiago S. Deficiency of serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in psoriatic patients: A case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:931–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson PB. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status in individuals with psoriasis in the general population. Endocrine. 2013;44:537–9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuchi MF, Azevedo Pde O, Tanaka AA, Schmitt JV, Martins LE. Serum levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in psoriatic patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:430–2. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maleki M, Nahidi Y, Azizahari S, Meibodi NT, Hadianfar A. Serum 25-OH vitamin D level in psoriatic patients and comparison with control subjects. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:207–10. doi: 10.1177/1203475415622207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertrand KA, Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Malspeis S, Eliassen AH, Wu K, et al. Determinants of plasma 25- hydroxyvitamin D and development of prediction models in three US cohorts. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:1889–96. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511007409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergler-Czop B, Brzezinska-Wcislo L. Serum vitamin D level—the effect on the clinical course of psoriasis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:445–9. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.63883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai Y, Fleming C, Yan J. New insights of T cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:302–9. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantorna MT. Vitamin D and autoimmunity: Is vitamin D status an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence? Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;223:230–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bikle DD. Vitamin D regulated keratinocyte differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:436–44. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bikle DD. Vitamin D metabolism and function in the skin. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;347:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arias-Santiago S, Orgaz-Molina J, Castellote-Caballero L, Arrabal-Polo MÁ, García-Rodriguez S, Perandrés-López R, et al. Atheroma plaque, metabolic syndrome and inflammation in patients with psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:337–44. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Worstman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, Lu Z, Holick MF. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:690–3. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ybarra J, Sanchez-Hernandez J, Perez A. Hypovitaminosis D and morbid obesity. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]