Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the postintensive care syndrome in patients who had vs patients who had not resumed driving 1 month after hospitalization for a critical illness.

After critical illness, up to 60% of adults experience persistent problems with cognition, mental health, and/or physical function, a constellation of symptoms known as postintensive care syndrome (PICS).1 These impairments can affect resumption of pre–critical illness activities, including driving. Fitness-to-drive assessments are used after some medical conditions, but little is known about safe return to driving after critical illness.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we analyzed clinical data collected 1 month after hospital discharge of adult patients in a critical illness recovery clinic who had sepsis, respiratory failure, and/or delirium during an intensive care unit (ICU) stay lasting more than 4 days.2 The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the study and waived the HIPAA authorization requirement as data were collected retrospectively. We followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

Driving status before and after critical illness was self-reported by patients, and PICS-related impairments were identified using validated assessments of multiple functional domains. Cognition was assessed with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with scores lower than 26 indicating an abnormal result with possible cognitive impairment. We analyzed associations of clinical, cognitive, and functional measures with resumption of driving using Wilcoxon rank sum and χ2 tests in Stata 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). All statistical tests were 2-sided, and significance was assessed at P < .05. Data were analyzed between June and August 2022.

Results

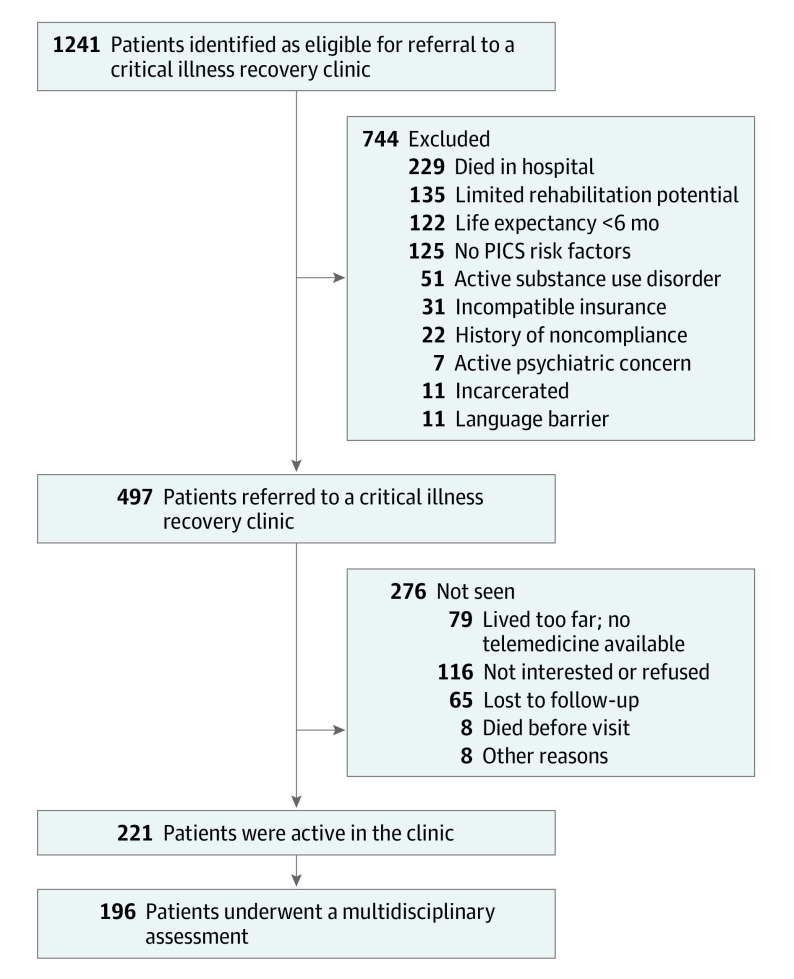

Of 196 consecutive patients seen at the clinic between June 2018 and March 2020 (Figure), 126 (47 females [37%], 79 males [63%]; mean [SD] age, 58 [16] years) reported driving before critical illness (Table). Sixteen of these patients (13%) had resumed driving 1 month after hospital discharge, whereas 110 patients (87%) had not.

Figure. Study Flow Diagram.

The multidisciplinary assessment identified postintensive care syndrome (PICS)–related pharmacy concerns; quality of life; and physical, social health, mental health, and cognitive impairments. It involved pharmacists, respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, physical therapists, dietitians, transition coordinators, and social workers.

Table. Patient Characteristics Stratified by Driving Status 1 Month After Hospital Discharge.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients (n = 126) | Patients who had resumed driving at 1 mo (n = 16) | Patients who had not resumed driving at 1 mo (n = 110) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 61 (46-68) | 59 (53-63.5) | 61 (45-68) | .64 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 47 (37) | 3 (19) | 44 (40) | .10a |

| Male | 79 (63) | 13 (81) | 66 (60) | |

| Highest educational level ≤high school | 77 (61) | 8 (50) | 69 (63) | .37a |

| Working before critical illness hospitalization | 54 (43) | 8 (50) | 46 (42) | .54a |

| Katz total score before critical illness hospitalization, median (IQR) | 6 (6-6) | 6 (6-6) | 6 (6-6) | .78 |

| Clinical Frailty Scale score before critical illness hospitalization, median (IQR) | 2 (2-3) | 2.5 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | .20 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (1-3) | 1 (0-2) | .74 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||||

| Neurological | 32 (25) | 1 (6) | 31 (28) | .19a |

| Sepsis or septic shock | 32 (25) | 6 (38) | 26 (24) | |

| Trauma, burn, or orthopedic injury | 33 (26) | 3 (19) | 30 (27) | |

| Respiratory failure | 12 (10) | 3 (19) | 9 (8) | |

| Otherb | 17 (14 | 3 (18) | 14 (13) | |

| Worst 24-h SOFA score, median (IQR) | 7 (4-10) | 7 (6-9) | 6 (4-10) | .18 |

| ICU length of stay, median (IQR), d | 10.5 (8-17) | 9 (7-11) | 11 (8-18) | .12 |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR), d | 20 (14-31) | 14.5 (12-25) | 21 (14-32) | .13 |

| Delirium in the ICUc | 100 (79) | 12 (75) | 88 (80) | .64a |

| No. of d with delirium, median (IQR) | 5 (3-7.5) | 4.5 (2-6.5) | 5 (3-7.5) | .71 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 108 (86) | 15 (94) | 93 (85) | .36a |

| Days of invasive ventilatory support, median (IQR) | 7 (4-11) | 5 (4-10) | 7 (4-11) | .49 |

| Highest JH-HLM Scale score in ICU, median (IQR) | 4 (3-7) | 7 (4-7) | 4 (3-7) | .05 |

| Discharge location | ||||

| Home or apartment | 40 (32) | 10 (63) | 30 (27) | .04a |

| Skilled nursing facility | 41 (33) | 3 (19) | 38 (35) | |

| Long-term acute care hospital | 7 (6) | 1 (6) | 6 (5) | |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 38 (30) | 2 (13) | 36 (33) | |

| Residence type at 1-mo follow-up | ||||

| Home or apartment | 90 (72) | 16 (100) | 74 (67) | <.01a |

| Skilled nursing facility | 36 (29) | 0 (0) | 36 (33) | |

| If working prior to critical illness, has the patient returned to work? | 16 (13) | 3 (19) | 0 (0) | <.001a |

| Clinical Frailty Score at follow-up, median (IQR) | 5 (4-6) | 3 (3-4) | 5 (4-6) | .001 |

| Katz total score at follow-up, median (IQR) | 1 (1-1) | 6 (5-6) | 5 (2-6) | .03 |

| Lawton IADL score at follow-up, median (IQR) | 8 (7-8) | 6.5 (5-8) | 2 (1-4) | <.001 |

| MoCA score at follow-up, median (IQR) | 23 (19-26) | 26 (24-27) | 23 (19-26) | .03 |

| Abnormal cognition at follow-upd | 82 (65) | 8 (50) | 74 (67) | .18a |

| HADS-Anxiety subscale score at follow-up, median (IQR) | 6 (3-10) | 4 (3-9) | 7 (4-11) | .21 |

| Anxiety at follow-upe | 31 (25) | 3 (19) | 28 (25) | .56 |

| HADS-Depression subscale score at follow-up, median (IQR) | 6 (3-9) | 7.5 (2-10) | 6 (3-9) | .98 |

| Depression at follow-upe | 29 (23) | 4 (25) | 25 (23) | .84 |

| PCL-5 score at follow-up, median (IQR) | 29 (9-99) | 34.5 (5-99) | 27 (9-99) | .96 |

| PTSD at follow-upf | 64 (51) | 9 (56) | 7 (6) | .64 |

| Overall HRQOL at follow-up, median (IQR)g | 70 (49-80) | 70 (50-75) | 69 (48-80) | .91 |

Abbreviations: HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; ICU, intensive care unit; JH-HLM, Johns Hopkins Highest Level of Mobility Scale; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PCL, posttraumatic stress disorder checklist; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Denotes 2-sided significance by χ2 tests of independence. All other comparisons were tested using Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Other diagnoses included gastrointestinal, hepatic, cardiovascular, kidney or urinary, endocrine disorders, and toxic overdose.

Assessed with Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist.

Assessed with MoCA, with a literature-based cutoff score lower than 26 indicating an abnormal result or cognitive impairment.

Assessed with HADS, with a cutoff score of 11 or higher indicating clinically significant anxiety or depression.

Assessed with PCL-5, with a cutoff score of 31 indicating probable PTSD.

Assessed with EuroQol-5 Dimension, with overall health ratings ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health status.

Baseline patient characteristics and critical illness features did not significantly differ between groups, except those who had resumed driving were more mobile in the ICU than those who had not (median [IQR] Johns Hopkins Highest Level of Mobility score, 7 [4-7] vs 4 [3-7]; P = .05). During follow-up, those who had resumed driving were less frail (median [IQR] Clinical Frailty Score, 3 [3-4] vs 5 [4-6]; P = .001), more independent in both basic (median [IQR] Katz Total Score, 6 [5-6] vs 5 [2-6]; P = .03) and instrumental (median [IQR] Lawton score, 6.5 [5-8] vs 2 [1-4]; P < .001) activities of daily living, and less likely to have cognitive impairment (median [IQR] MoCA score, 26 [24-27] vs 23 [19-26]; P = .03). Despite having better 1-month outcomes, 50% of patients who had resumed driving (n = 8) had a MoCA score of less than 26.

Discussion

In this study, few patients had resumed driving within 1 month of discharge. Half of these patients had MoCA scores lower than 26, a finding that has safety implications because such MoCA scores are associated with worse fitness-to-drive test ratings3 and because cognitive screening results are lower in unsafe drivers4 and those who stop driving due to an accident or medical advice.5

Patients who resumed driving while cognitively impaired may place themselves and others at risk, but unnecessarily delaying the return to driving may contribute to isolation and reduced access to health care. While US state laws regulate driver’s license eligibility for people with certain medical conditions (eg, epilepsy) and guidelines exist regarding driving and dementia, the decision to drive after critical illness is made by patients and care partners.6 A systematic, evidence-based approach to evaluating fitness to drive after critical illness is needed.

Study strengths included use of validated assessments for PICS-related impairments and a heterogeneous study population. Limitations included a modest single-site sample of self-selected participants who were assessed only 1 month after discharge. Since recovery is often characterized by impairments that can persist for years after critical illness, future studies should assess resumption of driving in this population over a longer period. The sample, however, was typical of patients receiving care during the early postdischarge period, and data on pre–critical illness driving status guided our interpretations.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Co-occurrence of post-intensive care syndrome problems among 406 survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):1393-1401. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton TL, Scheunemann LP, Butcher BW, Donovan HS, Alexander S, Iwashyna TJ. The prevalence of spiritual and social support needs and their association with postintensive care syndrome symptoms among critical illness survivors seen in a post-ICU follow-up clinic. Crit Care Explor. 2022;4(4):e0676. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandasamy D, Williamson K, Carr D, Abbott D, Betz M. The utility of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in predicting need for fitness to drive evaluations in older adults. J Transp Health. 2019;13:19-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2019.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freund B, Colgrove LA. Error specific restrictions for older drivers: promoting continued independence and public safety. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40(1):97-103. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kokkinakis I, Vaucher P, Cardoso I, Favrat B. Assessment of cognitive screening tests as predictors of driving cessation: a prospective cohort study of a median 4-year follow-up. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer J, Pattison N, Apps C, Gager M, Waldmann C. Driving resumption after critical illness: a survey and framework analysis of patient experience and process. J Intensive Care Soc. 2022. doi: 10.1177/17511437221099118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement