Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Better understanding of predictors of opioid abstinence among patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) may help to inform interventions and personalize treatment plans. This analysis examined patient characteristics associated with opioid abstinence in the X:BOT (Extended-Release Naltrexone versus Buprenorphine for Opioid Treatment) trial.

Methods:

This post-hoc analysis examined factors associated with past-month opioid abstinence at the 36-week follow-up visit among participants in the X:BOT study. 428 participants (75% of original sample) attended the visit at 36 weeks. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the probability of opioid abstinence across various baseline sociodemographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment variables.

Results:

Of the 428 participants, 143 (33%) reported abstinence from non-prescribed opioids at the 36-week follow-up. Participants were more likely to be opioid abstinent if randomized to XR-NTX (compared to BUP-NX), were on XR-NTX at week 36 (compared to those off OUD pharmacotherapy), successfully inducted onto either study medication, had longer time on study medication, reported a greater number of abstinent weeks, or had longer time to relapse during the 24-week treatment trial. Participants were less likely to be abstinent if Hispanic, had a severe baseline Hamilton Depression Rating (HAM-D) score, or had baseline sedative use.

Conclusions:

A substantial proportion of participants were available at follow-up (75%), were on OUD pharmacotherapy (53%), and reported past-month opioid abstinence (33%) at 36 weeks. A minority of patients off medication for OUD reported abstinence and additional research is needed exploring patient characteristics that may be associated with successful treatment outcomes.

1. Introduction

The opioid crisis continues to grip the United States with over 1.6 million people with opioid use disorder (OUD) and over 100,000 drug overdose deaths in the past year (reported in April 2021), the majority related to opioids. This dramatic increase, a nearly 30% increase from the year before, comes amid the rise in highly potent synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and the challenges of the coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic (Ahmad et al., 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019; Volkow, 2020). FDA-approved medications effective in treating OUD include the full opioid agonist methadone, partial agonist buprenorphine, and the antagonist naltrexone in extended-release formulation (Comer et al., 2006; Krupitsky et al., 2011; Mattick et al., 2003, 2004). These treatments are underutilized and most individuals do not receive medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019; Williams et al., 2019). Even after successful initiation of MOUD, many patients are not retained in treatment (Timko et al., 2016). Patients who stop medication are at increased risk for relapse and overdose, although a minority do succeed in remaining abstinent (Williams et al., 2020; Bailey et al., 2013; Binswanger, 2013).

Most studies examining opioid abstinence have included patients on buprenorphine or methadone, and few have looked at injectable naltrexone. Even fewer studies have examined opioid abstinence in the naturalistic treatment setting. A previous secondary analysis by our group examined opioid use outcomes in a naturalistic follow-up after the X:BOT trial and found similar rates of opioid abstinence for participants on MOUD (sublingual buprenorphine, methadone, injectable naltrexone) and those off medication (33% versus 34%) (Greiner et al., 2021). If medication status (on or off MOUD) in the past 30 days is not significant, then this raises the clinical question of whether duration of MOUD treatment or patient characteristics may be associated with opioid abstinence.

Prior studies that have examined correlates of opioid abstinence among individuals with opioid use disorder (on or off MOUD) suggest that it is positively associated with female gender (Darke et al., 2015), older age (Dreifuss et al., 2013; Naji et al., 2016), more social support (Dennis et al., 2007; Flynn et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2018), being employed (Dennis et al., 2007; Flynn et al., 2003; McKenna, 2017; Nosyk et al., 2013), less impulsivity (Zhu et al., 2018), older age at first opioid use (Zhu et al., 2018), fewer lifetime treatment episodes (Darke et al., 2015), and longer duration on MOUD (Nosyk et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2018). Factors negatively associated with abstinence include Hispanic ethnicity (Zhu et al., 2018), substance use among social network (Goehl et al., 1993), criminal and legal involvement (Dennis et al., 2007; Flynn et al., 2003; Nosyk et al., 2013; Scott et al., 2011), IV drug use (Darke et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2018), more frequent baseline opioid use (Darke et al., 2015), cocaine use (Darke et al., 2007; Joe et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 2018), benzodiazepine use (Dreifuss et al., 2013; Naji et al., 2016; Nosyk et al., 2013), heavy alcohol use (Flynn et al., 2003), comorbid substance use disorders (Marsch et al., 2005), and a greater number of prior treatment episodes (Darke et al., 2015; Dreifuss et al., 2013).

This exploratory secondary analysis provides new data on the association between patient characteristics and non-prescribed opioid abstinence 30 days prior to the 36-week follow-up among participants in the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) Extended-Release Naltrexone (XR-NTX) versus Buprenorphine-Naloxone (BUP-NX) for Opioid Treatment trial (X:BOT) (Lee et al., 2018). We hypothesized that baseline characteristics associated with lesser disease severity, less burden of comorbid psychiatric illness and substance use, absence of pain diagnosis, and psychosocial determinants (employment, stable housing, and absence of substance use among social network) would be associated with opioid abstinence. We also hypothesized that participants who had better outcomes during the 24-week treatment trial (successful induction onto study medication, longer time on medication, a greater number of abstinent weeks, and longer time to relapse) would be more likely to be abstinent from non-prescribed opioids at follow-up.

2. Methods

2.1. Design Overview

This exploratory secondary analysis was based on data from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) X:BOT trial (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02032433). The X:BOT trial was a multisite, 24-week, randomized comparative effectiveness trial of buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NX) (N=287) versus extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) (N=283) for prevention of relapse among individuals with OUD. Study design and rationale have been described previously (Lee et al., 2018; Nunes et al., 2016). Briefly, participants were recruited from eight community-based detoxification programs across the United States. Eligible participants were 18 years or older, English-speaking, had non-prescribed opioid use (heroin, codeine, morphine, oxycodone, methadone, or buprenorphine) within the past month, and met criteria for OUD as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Exclusion criteria included serious medical or psychiatric conditions, suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, other severe substance use disorders, elevated liver transaminases (>5 times the upper limit of normal), chronic pain requiring opioids, methadone maintenance ≥30mg per day, legal status precluding study completion, or reported allergy or sensitivity to BUP-NX or XR-NTX. Females planning pregnancy, pregnant, breastfeeding, or not using a birth control method were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of New York University Medical Center, individual sites obtained local Institutional Review Board approval, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were randomized to BUP-NX or XR-NTX during inpatient admission, stratified by site and by severity of opioid use (high severity operationalized as intravenous heroin use ≥6 bags per day). BUP-NX was initiated after participants had withdrawal symptoms and could tolerate an initial dose. Prior to XR-NTX injection, participants had to complete detoxification and remain off opioids for at least 5 to 7 days, provide a negative opioid urine toxicology, and pass a naloxone challenge.

Participants were followed for up to 24 weeks after randomization and provided with assigned study medication in the context of medical management and outpatient counseling, the latter available (but not required) at community treatment programs. Assessments included weekly self-reported non-prescribed opioid and other substance use, urine toxicology, ratings of opioid cravings, and adverse events. BUP-NX dose was adjusted as clinically indicated (ranging from 8mg to 24mg per day) and XR-NTX (380mg) was administered intramuscularly approximately every 28 days.

Study medications were provided until participant dropout, relapse, or upon completion of the 24-week treatment trial. Participants were encouraged to continue OUD pharmacotherapy at the same community-based treatment program or were referred elsewhere in the community. OUD pharmacotherapy and treatment procedures were naturalistic and may have varied across community settings. Referral for MOUD included methadone, buprenorphine, or injectable naltrexone. Follow-up assessments were at 28 and 36 weeks. Assessments at follow-up visits included the same assessments administered in the 24-week trial. In some cases, follow-up assessments were conducted over the phone and urine toxicology samples were not collected in these instances. This sample included participants who completed the 36-week follow-up (n=428). This timepoint was selected to explore outcomes in the naturalistic treatment setting (i.e., study medications no longer provided and patients receiving treatment in the community). The 28-week follow-up sample was not included in this analysis since there were fewer participants (N=368).

2.2. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Variables

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics examined for association with the opioid abstinence outcome are listed in Table 1. In addition to demographics, variables were chosen that were associated with severity or treatment outcome of OUD based on prior literature (Zhu et al., 2018; Dreifuss et al., 2013; Darke et al., 2007; Nunes et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 2006; Goehl et al., 1993). These included severity of opioid use, characteristics of opioid and other substance use, number of family and friends using heroin or other illicit drugs, number of treatment episodes for substance use, self-reported importance of substance use treatment, history of psychiatric disorders, baseline Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score (Hamilton, 1960), pain, and legal status (on parole or probation). Items were drawn from the medical and psychiatric history, Timeline Followback (TLFB) (Sobell & Sobell, 2000), select items from the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992), and EuroQol (EQ-5D-3L) (Rabin & de Charro, 2001). Opioid use severity was classified as low or high with high use defined as ≥6 bags IV heroin per day in the seven days prior to admission. Other substance use 30 days prior to inpatient admission was assessed using TLFB and included stimulants, sedatives, heavy alcohol (≥5 drinks per day for males and ≥4 drinks per day for females), and cannabis.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of participants at week 36.

| Total Sample (n=428) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measure | n | % or Mean (SD) |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years) | 428 | 34.0 (10.1) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 297 | 69.4% |

| Female | 131 | 30.6% |

| Race | ||

| White Only | 308 | 72.0% |

| Black Only | 46 | 10.7% |

| Other | 74 | 17.3% |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 80 | 18.7% |

| Education | ||

| <HS | 94 | 22.0% |

| HS/GED | 144 | 33.6% |

| >HS | 190 | 44.4% |

| Unemployed | 266 | 62.1% |

| Legal Status | ||

| On parole or probation | 57 | 13.3% |

| Living Situation | ||

| Currently Homeless | 114 | 26.6% |

| Number of family/friends using heroin or other illicit drugs | ||

| 0 | 163 | 38.4% |

| 1–2 | 95 | 22.4% |

| 3+ | 167 | 39.3% |

| Opioid Use | ||

| Age of onset opioid use | 428 | 21.2 (7.1) |

| Duration of opioid use (years) | 428 | 12.9 (9.5) |

| Primary opioid use | ||

| Heroin | 356 | 83.4% |

| Opioid analgesics | 71 | 16.6% |

| Route of use | ||

| IV use | 300 | 70.1% |

| No IV use | 128 | 29.9% |

| Severity of opioid use | ||

| Low | 253 | 59.1% |

| High (≥ 6 bags IV heroin daily) | 175 | 40.9% |

| Other Substance Use | ||

| Tobacco smoker | 388 | 90.7% |

| Stimulant use (30 days prior to admission) | 231 | 54.1% |

| Sedative use (30 days prior to admission) | 119 | 27.9% |

| Heavy alcohol use (30 days prior to admission) | 111 | 26.0% |

| Cannabis use (30 days prior to admission) | 197 | 46.1% |

| Treatment History | ||

| Current treatment is first opioid treatment in lifetime | 154 | 36.0% |

| Number of times treated for any substance use | ||

| 0 | 33 | 7.7% |

| 1 | 87 | 20.3% |

| 2–5 | 197 | 46.0% |

| 6+ | 111 | 25.9% |

| Self-reported Importance of Current Treatment | ||

| Not at all | 9 | 2.1% |

| Slightly | 5 | 1.2% |

| Moderately | 8 | 1.9% |

| Considerably | 37 | 8.6% |

| Extremely | 369 | 86.2% |

| Psychiatric Symptoms and History | ||

| History of psychiatric disorder | 289 | 67.5% |

| HAM-D score | ||

| Normal (< 8) | 212 | 49.6% |

| Mild (8–13) | 104 | 24.4% |

| Moderate (14–18) | 70 | 16.4% |

| Severe (> 18) | 41 | 9.6% |

| Pain | ||

| Moderate pain or discomfort | 236 | 55.1% |

| Extreme pain or discomfort | 17 | 4.0% |

Abbreviations: SD=Standard Deviation; HS=High School; GED=General Educational Development; IV=intravenous; HAM-D=Hamilton Rating Depression Scale

2.3. Treatment Variables

Treatment-related variables included randomization assignment (BUP-NX or XR-NTX), successful induction onto study medication (binary: inducted/not inducted), time to relapse (in weeks), time on study medication (in weeks), number of abstinent weeks during the 24-week trial, site (1–8), and medication status at week 36 (BUP-NX, XR-NTX, methadone, or off MOUD).

Randomization assignment

Randomization assignment was defined as randomization to either BUP-NX or XR-NTX in the 24-week treatment phase.

Induction status

Induction status was dichotomous (inducted versus not inducted) onto study medication (BUP-NX or XR-NTX) in the 24-week treatment phase.

Time to relapse

Time to relapse was defined as the use of non-study opioids any time after 20 days post-randomization: at the start of 4 consecutive opioid use weeks or at the start of 7 consecutive days of self-reported opioid use days. A use week was defined as any week during which a participant reported at least one day of nonprescribed opioid use or provided a urine sample positive for non-study opioids. If a urine sample was missing, then relapse was based on the self-report from TLFB since some assessments were done remotely over the phone at week 36. Of the 428 participants who completed week 36 assessments, 49 (11%) had missing urine samples.

Time on study medication

Time on study medication was defined as number of weeks during the 24-week trial that participants reported being on medication (BUP-NX or XR-NTX). Time was computed between induction and the date of the last dose for BUP-NX or 4 weeks after the last XR-NTX injection.

Number of abstinent weeks

Number of abstinent weeks during the 24-week trial was defined using results from weekly urine samples. Abstinence was operationalized as no non-prescribed opioid use in the past week indicated by a negative urine sample for non-prescribed opioids [heroin, codeine, morphine, oxycodone, methadone and buprenorphine (if not on maintenance treatment)].

Medication status at week 36

Medication status at week 36 was determined using the Medical Management Log and self-report by participants on whether or not they had continued to receive treatment in the community as planned (on MOUD versus off MOUD) and which medication (BUP-NX, XR-NTX, or methadone) in the 30 days prior to the 36-week follow-up.

2.4. Outcome Measure

Past-month opioid abstinence

Past-month opioid abstinence reported at week 36 was dichotomous (abstinent versus not abstinent) and operationalized as no non-prescribed opioid use in the past 30 days using self-report with TLFB and a negative (or missing) urine sample for non-prescribed opioids [heroin, codeine, morphine, oxycodone, methadone and buprenorphine (if not on maintenance treatment)]. Unlike in the main study, missing urine samples were not considered to be positive since some follow-up assessments were done remotely over the phone.

2.5. Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported for sample characteristics and by opioid abstinence status; with means and standard deviations (for continuous variables) or frequency and percentages (for categorical variables). To explore potential differences in baseline characteristics between participants available at the 36-week follow-up (N=428) and those missing (N=142), separate logistic regression models were fit to assess whether baseline patient and clinical characteristics were associated with week 36 missingness.

To assess baseline correlates of past-month opioid abstinence at week 36, separate logistic regression models were fit to estimate the probability of opioid abstinence for each baseline and study measure. Model-estimated odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were presented from all logistic regression models.

The interest of this secondary analysis was exploratory, with the goal of generating hypotheses for future work. As such, all tests were two-tailed with alpha level held at 0.05 for statistical significance, and were not corrected for multiple comparisons, in order to identify and investigate associations that may be potentially important. Pairwise comparisons were interpreted only when the omnibus tests were significant to maintain limits on the possibility of Type I error. SAS® version 9.4 was used for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

At week 36, 428 (75%) of 570 participants completed assessments and had TLFB data. This follow-up sample included 225 (78%) of the 287 participants initially randomized to BUP-NX and 203 (72%) of 283 participants randomized to XR-NTX). The majority of participants at 36 weeks (375 (88%)) had successfully inducted onto study medication, and of those about half reported being on medication at week 36. Of the 225 participants on MOUD, 120 (53%) were on BUP-NX, 88 (39%) on XR-NTX (of which 87 were on XR-NTX and 1 participant reported switching to oral naltrexone), and 17 (8%) on methadone. Of the 53 participants at week 36 that failed induction onto study medication, 27 (51%) reported being on MOUD at follow-up.

Baseline demographic and participant characteristics are shown in Table 1 for the total sample available at week 36 (N=428). Most participants were white, in their early 30s, unemployed, and over half had a high school education or less. Thirteen percent of participants were on parole or probation, 27% were homeless, and 62% reported having family or friends using heroin or other illicit drugs. The majority had IV use with primary opioid of heroin (as opposed to opioid analgesics), had low severity of opioid use (<6 bags IV heroin use per day), and first began using opioids at an average age of 21 with an average of 13 years of opioid use. Thirty-six percent of participants reported this being their first opioid treatment episode and 86% reported substance use treatment being extremely important to them. Ninety-one percent were current smokers and many reported other substance use (54% reported stimulants, 28% sedatives, 26% heavy alcohol, and 46% cannabis). Sixty-eight percent had a history of a psychiatric disorder. Half of the participants had normal baseline HAM-D scores, about a quarter had mild, and a quarter had moderate or severe. Over half of participants reported moderate to extreme physical pain on the EQ-5D-3L.

Participants available at week 36 (N=428) significantly differed on three baseline measures compared to those missing (N=142, Supplemental Table 1). Participants whose primary opioid was heroin (77%) (compared to opioid analgesics) (OR [95% CI] = 1.59 [1.00, 2.53]) and with IV use (78%) were more likely to be available at week 36 compared to those with no IV use (69%) (OR [95% CI] = 1.57 [1.06, 2.33]). Participants on probation or parole (62%) were less likely to be available at follow-up compared to those who were not (78%) (OR [95% CI] = 0.47 [0.29, 0.76]). Otherwise, participants evaluated at week 36 did not differ significantly from those who were not available, across demographic and other baseline clinical variables.

3.2. Opioid Abstinence and Baseline Correlates

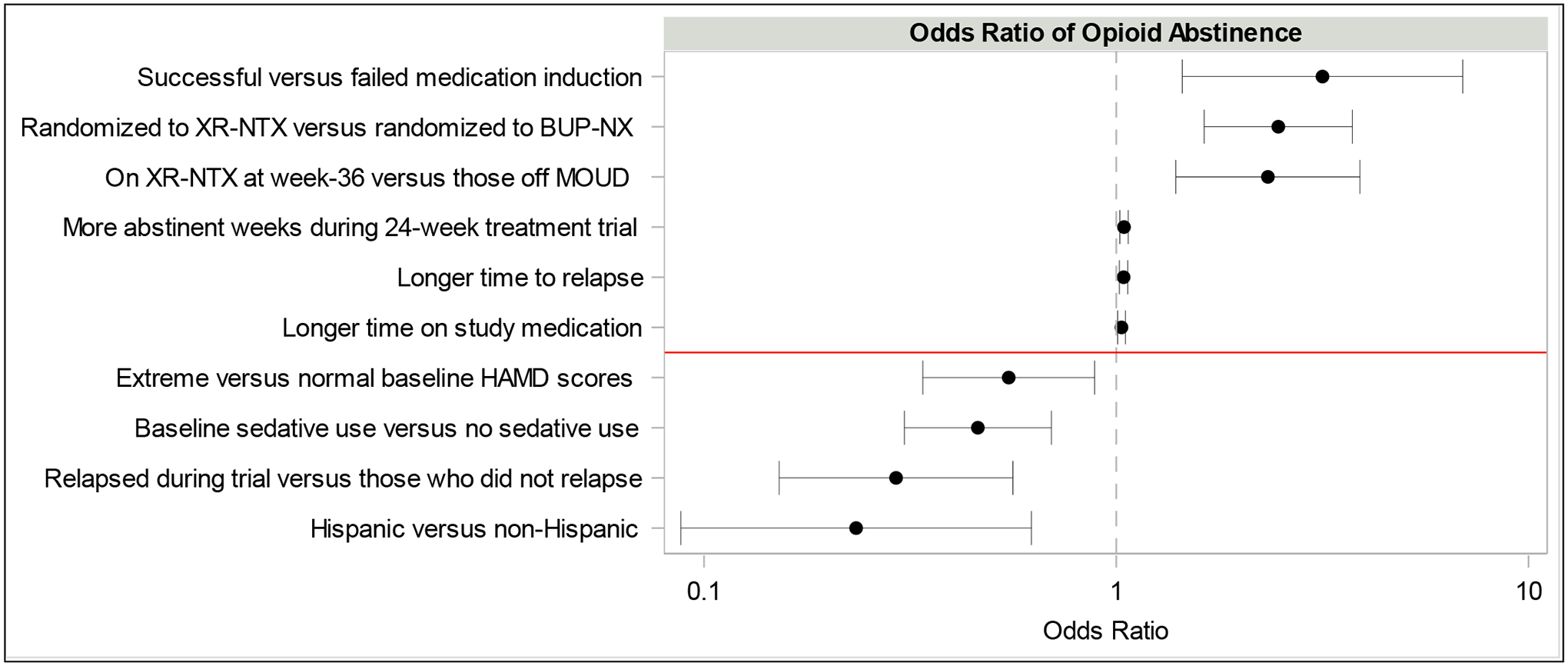

At the 36-week follow-up, 143 (33%) of 428 participants reported past-month abstinence from non-prescribed opioids, and 285 (67%) were not abstinent (Table 2). Among the demographic and baseline clinical characteristics examined, only three were found to be significantly associated with past-month opioid abstinence (Figure 1). Hispanic participants were less likely to be abstinent from non-prescribed opioids (15%) compared to non-Hispanics (38%) (OR [95% CI] = 0.29 [0.15, 0.56]). Participants with severe baseline HAM-D scores (OR [95% CI] = 0.23 [0.09, 0.62]) were less likely to be abstinent from non-prescribed opioids compared to those with normal HAM-D scores. Those with sedative use were less likely to be abstinent at week 36 compared to those with no sedative use (24% versus 37%) (OR [95% CI] = 0.55 [0.34, 0.89]).

Table 2.

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics by week 36 opioid abstinence groups and logistic regression model results.

| Opioid Abstinent (n=143) | Not Opioid Abstinent (n=285) | Model Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | n | Row % or Mean (SD) | n | Row % or Mean (SD) | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 143 | 33.4 (9.7) | 285 | 34.3 (10.3) | 0.99 | (0.97, 1.01) | 0.3810 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 95 | 32.0% | 202 | 68.0% | ref | ||

| Female | 48 | 36.6% | 83 | 63.4% | 1.23 | (0.80, 1.89) | 0.3477 |

| Race | 0.0729 | ||||||

| White | 113 | 36.7% | 195 | 63.3% | ref | ||

| Black | 11 | 23.9% | 35 | 76.1% | 0.54 | (0.26, 1.11) | 0.0947 |

| Other | 19 | 25.7% | 55 | 74.3% | 0.60 | (0.34, 1.06) | 0.0764 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 12 | 15.0% | 68 | 85.0% | 0.29 | (0.15, 0.56) | 0.0002 |

| Non-Hispanic | 131 | 37.6% | 217 | 62.4% | |||

| Education | 0.6446 | ||||||

| <HS | 30 | 31.9% | 64 | 68.1% | ref | ||

| HS/GED | 45 | 31.3% | 99 | 68.8% | 0.97 | (0.55, 1.70) | 0.9141 |

| >HS | 68 | 35.8% | 122 | 64.2% | 1.19 | (0.70, 2.01) | 0.5186 |

| Not employed | 94 | 35.3% | 172 | 64.7% | 1.26 | (0.83, 1.92) | 0.2798 |

| Legal Status | |||||||

| On parole or probation | 23 | 40.4% | 34 | 59.6% | 1.41 | (0.79, 2.50) | 0.2405 |

| Living Situation | |||||||

| Currently homeless | 36 | 31.6% | 78 | 68.4% | 0.89 | (0.56, 1.41) | 0.6286 |

| Number of family/friends using heroin or other illicit drugs | 0.0814 | ||||||

| 0 | 45 | 27.6% | 118 | 72.4% | ref | ||

| 1–2 | 39 | 41.1% | 56 | 58.9% | 1.83 | (1.07, 3.12) | 0.0276* |

| 3+ | 58 | 34.7% | 109 | 65.3% | 1.40 | (0.87, 2.23) | 0.1641 |

| Opioid Use | |||||||

| Age of onset opioid use | 143 | 21.4 (7.4) | 285 | 21.1 (7.0) | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.03) | 0.6707 |

| Duration of opioid use (years) | 143 | 12.0 (8.8) | 285 | 13.3 (9.9) | 0.99 | (0.96, 1.01) | 0.2134 |

| Primary opioid use | |||||||

| Heroin | 114 | 32.0% | 242 | 68.0% | 0.72 | (0.43, 1.23) | 0.2279 |

| Opioid analgesics | 28 | 39.4% | 43 | 60.6% | ref | ||

| Route of use | |||||||

| IV use | 102 | 34.0% | 198 | 66.0% | 1.09 | (0.70, 1.70) | 0.6928 |

| No IV use | 41 | 32.0% | 87 | 68% | |||

| Severity of opioid use | |||||||

| Low | 78 | 30.8% | 175 | 69.2% | ref | ||

| High (≥ 6 bags IV heroin daily) | 65 | 37.1% | 110 | 62.9% | 1.33 | (0.88, 1.99) | 0.1746 |

| Other Substance Use | |||||||

| Tobacco smoker | 130 | 33.5% | 258 | 66.5% | 1.05 | (0.52, 2.10) | 0.8980 |

| Stimulant use (30 days prior to admission) | 86 | 37.2% | 145 | 62.8% | 1.45 | (0.96, 2.18) | 0.0767 |

| Sedative use (30 days prior to admission) | 29 | 24.4% | 90 | 75.6% | 0.55 | (0.34, 0.89) | 0.0142 |

| Heavy alcohol use (30 days prior to admission) | 41 | 36.9% | 70 | 63.1% | 1.23 | (0.78, 1.93) | 0.3719 |

| Cannabis use (30 days prior to admission) | 61 | 31.0% | 136 | 69.0% | 0.81 | (0.54, 1.22) | 0.3071 |

| Treatment History | |||||||

| Current treatment is first opioid treatment in lifetime | 53 | 34.4% | 101 | 65.6% | 1.07 | (0.71, 1.63) | 0.7414 |

| Number of times treated for any substance use | 0.2917 | ||||||

| 0 | 8 | 24.2% | 25 | 75.8% | ref | ||

| 1 | 34 | 39.1% | 53 | 60.9% | 2.00 | (0.81, 4.97) | 0.1328 |

| 2–5 | 69 | 35.0% | 128 | 65.0% | 1.68 | (0.72, 3.94) | 0.2289 |

| 6+ | 32 | 28.8% | 79 | 71.2% | 1.27 | (0.52, 3.11) | 0.6063 |

| Self-reported Importance of Current Treatment | 0.7214 | ||||||

| Not at all | 3 | 33.3% | 6 | 66.7% | ref | ||

| Slightly | 3 | 60.0% | 2 | 40.0% | 3.00 | (0.31, 29.03) | 0.3419 |

| Moderately | 2 | 25.0% | 6 | 75.0% | 0.67 | (0.08, 5.57) | 0.7076 |

| Considerably | 14 | 37.8% | 23 | 62.2% | 1.22 | (0.26, 5.69) | 0.8020 |

| Extremely | 121 | 32.8% | 248 | 67.2% | 0.98 | (0.24, 3.98) | 0.9727 |

| Psychiatric Symptoms and History | |||||||

| History of psychiatric disorder | 92 | 31.8% | 197 | 68.2% | 0.81 | (0.53, 1.23) | 0.3194 |

| HAM-D score | 0.0130 | ||||||

| Normal (< 8) | 79 | 37.3% | 133 | 62.7% | ref | ||

| Mild (8–13) | 40 | 38.5% | 64 | 61.5% | 1.05 | (0.65, 1.71) | 0.8366 |

| Moderate (14–18) | 19 | 27.1% | 51 | 72.9% | 0.63 | (0.35, 1.14) | 0.1257 |

| Severe (> 18) | 5 | 12.2% | 36 | 87.8% | 0.23 | (0.09, 0.62) | 0.0037 |

| Pain | 0.0798 | ||||||

| Moderate pain or discomfort | 68 | 28.8% | 168 | 71.2% | 0.62 | (0.41, 0.94) | 0.0249* |

| Extreme pain or discomfort | 6 | 35.3% | 11 | 64.7% | 0.84 | (0.30, 2.38) | 0.7391 |

Omnibus p-value is not significant.

Abbreviations: SD=Standard Deviation; HS=High School; GED=General Educational Development; IV=intravenous; HAM-D=Hamilton Rating Depression Scale

Figure 1.

Factors significantly associated with past-month opioid abstinence at week 36.*

*Odds ratios are presented on the x-axis with a log scale. 95% confidence intervals are shown for odds ratios.

Abbreviations: XR-NTX=extended-release injectable naltrexone; BUP-NX=buprenorphine-naloxone; MOUD=medication for opioid use disorder; HAM-D=Hamilton Rating Depression Scale

3.3. Treatment Factors Associated with Opioid Abstinence

Several treatment variables were found to be significantly associated with opioid abstinence at week 36 (Table 3; Figure 1). Participants randomized to XR-NTX were more likely to be abstinent from non-prescribed opioids compared to those randomized to BUP-NX (44% versus 24%) (OR [95% CI] = 2.47 [1.63, 3.74]). Participants who successfully inducted onto either study medication were more likely to be abstinent from non-prescribed opioids compared to those not inducted (36% versus 15%) (OR [95% CI] = 3.16 [1.45, 6.92]). Other significant positive correlates of opioid abstinence included: longer time on study medication with an average of 16 weeks (SD 9.0) for those opioid abstinent compared to 14 weeks (SD 9.7) for those not abstinent (OR [95% CI] = 1.03 [1.01, 1.05]), longer time to relapse with an average of 23 weeks (IQR 7.4–23.4) for those opioid abstinent compared to 13 weeks (IQR 3.1–23.4) for those not abstinent (OR [95% CI] = 1.04 [1.02, 1.07]), more abstinent weeks with an average of 15 weeks (SD 8.4) for those opioid abstinent compared to 12 weeks (SD 9.1) for those not opioid abstinent at week 36 (OR [95% CI] = 1.04 [1.02, 1.07]), and those that reported being on XR-NTX at week 36 (53%) compared to those that reported being off medication (34%) (OR [95% CI] = 2.33 [1.40, 3.90]).

Table 3.

Treatment variables by week 36 opioid abstinence groups and logistic regression model results.

| Opioid Abstinent (n=143) | Not Opioid Abstinent (n=285) | Model Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | n | Row % or Mean (SD) | n | Row % or Mean (SD) | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Sites | 0.1757 | ||||||

| Site 1 | 21 | 33.9% | 41 | 66.1% | ref | ||

| Site 2 | 23 | 39.7% | 35 | 60.3% | 1.28 | (0.61, 2.71) | 0.5118 |

| Site 3 | 11 | 26.2% | 31 | 73.8% | 0.69 | (0.29, 1.65) | 0.4066 |

| Site 4 | 25 | 36.8% | 43 | 63.2% | 1.14 | (0.55, 2.34) | 0.7306 |

| Site 5 | 18 | 24.0% | 57 | 76.0% | 0.62 | (0.29, 1.30) | 0.2049 |

| Site 6 | 16 | 32.7% | 33 | 67.3% | 0.95 | (0.43, 2.10) | 0.8926 |

| Site 7 | 22 | 47.8% | 24 | 52.2% | 1.79 | (0.82, 3.92) | 0.1453 |

| Site 8 | 7 | 25.0% | 21 | 75.0% | 0.65 | (0.24, 1.78) | 0.4023 |

| Treatment Assignment | |||||||

| BUP-NX | 54 | 24.0% | 171 | 76.0% | ref | ||

| XR-NTX | 89 | 43.8% | 114 | 56.2% | 2.47 | (1.63, 3.74) | <.0001 |

| Induction Status | |||||||

| Successful induction onto BUP-NX or XR-NTX | 135 | 36.0% | 240 | 64.0% | 3.16 | (1.45, 6.92) | 0.0040 |

| Relapse History | |||||||

| Relapse | 57 | 25.3% | 168 | 74.7% | 0.46 | (0.31, 0.70) | 0.0002 |

| Time to relapse in weeks | 143 | 23.4 (7.4–23.4) | 285 | 13.3 (3.1–23.4) | 1.04 | (1.02, 1.07) | 0.0003 |

| Opioid Abstinence History | |||||||

| Number of abstinent weeks | 142 | 15.2 (8.4) | 277 | 12.0 (9.1) | 1.04 | (1.02, 1.07) | 0.0006 |

| MOUD History | |||||||

| Time on study medication in weeks | 143 | 16.3 (9.0) | 276 | 13.7 (9.7) | 1.03 | (1.01, 1.05) | 0.0092 |

| MOUD status at week 36 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| Off MOUD | 68 | 33.5% | 135 | 66.5% | ref | ||

| BUP-NX | 28 | 23.3% | 92 | 76.7% | 0.60 | (0.36, 1.01) | 0.0546 |

| XR-NTX* | 47 | 53.4% | 41 | 46.6% | 2.28 | (1.37, 3.79) | 0.0016 |

| Methadone | 0 | 0.0% | 17 | 100.0% | 0.00 | -- | 0.8224 |

Abbreviations: SD=Standard Deviation; BUP-NX=buprenorphine-naloxone; XR-NTX=extended-release injectable naltrexone; MOUD=medication for opioid use disorder

1 participant in XR-NTX group on oral naltrexone.

4. Discussion

We evaluated patient characteristics and treatment variables as correlates of non-prescribed opioid abstinence among those available at the 36-week follow-up in the X:BOT study. Most baseline patient characteristics generally considered to be related to greater severity of OUD were not significantly associated with opioid abstinence at follow-up, while success in treatment, in particular earlier treatment during the 24-week trial, was associated with later abstinence. Psychosocial determinants such as employment, stable housing, and absence of substance use among participant’s social network were also found to be nonsignificant. These findings are similar to a follow-up study by Weiss et al (Weiss et al., 2015) that looked at opioid use outcomes at 42 months among a subset of individuals who had participated in a trial of sublingual buprenorphine treatment for different durations, and were randomized to receive or not receive additional drug counseling in conjunction with standard medical management for prescription opioid dependence (Weiss et al., 2011). Engagement in buprenorphine therapy was significantly associated with abstinence at 42-month follow-up, whereas most baseline patient characteristics were not.

Baseline characteristics may be less associated with the outcome in these analyses due to the nature of treatment in the initial randomized-controlled trials (RCTs). Baseline characteristics and psychosocial determinants may influence treatment engagement and outcomes more so in the naturalistic setting, whereas in an RCT, patients are engaging in treatment in a controlled setting. Patients are less likely to encounter barriers to entering and continuing in treatment, accessing medication (when study-provided), or encountering other community-level barriers.

In this report, individuals who had better outcomes during the 24-week treatment trial (longer time on study medication, a greater number of abstinent weeks, and longer time to relapse) were more likely to report opioid abstinence at 36 weeks. Our measure of opioid abstinence was limited to the past month. A few studies have explored longer term opioid use outcomes (Darke et al., 2015; Y. I. Hser et al., 2001; Soyka et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2020). Hser and colleagues found that maintaining opioid abstinence for at least 5 years substantially increases the likelihood of future stable abstinence (Y. I. Hser et al., 2001; Y.-I. Hser, 2007).

Longer time on study medication (BUP-NX or XR-NTX) during the 24-week treatment trial was also positively associated with non-prescribed opioid abstinence at follow up. A retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis of Medicaid claims found that patients were at high risk for relapse and overdose after buprenorphine discontinuation, irrespective of treatment duration (up to 18 months) (Williams et al., 2020). The optimal length of treatment on MOUD continues to be an important clinical question, and more research is needed exploring this in naturalistic treatment settings.

The majority of patients who discontinue medication are at increased risk for relapse and overdose, although a minority do succeed in remaining abstinent (Williams et al., 2020; Bailey et al., 2013; Binswanger, 2013). As seen in a previous secondary analysis by our group, we found similar rates of opioid abstinence in the past month between participants on MOUD and those off medication at week 36, although relapse rates were higher among those off MOUD (Greiner et al., 2021). In one trial performed in Russia (Krupitsky et al., 2011), 30% of patients that received placebo and counseling alone after inpatient detoxification were abstinent throughout the 24-week study compared to the 50% randomized to XR-NTX. Still, more evidence supports better outcomes and abstinence for the majority of patients on MOUD compared to those off medication (Krupitsky et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2019, 2015; Y.-I. Hser et al., 2016; Y.-I. Hser, 2007).

However, in this analysis, only XR-NTX (compared to off MOUD) was found to be significantly associated with opioid abstinence at week 36. In addition, those randomized to XR-NTX (versus BUP-NX) in the main trial were more likely to be abstinent at follow-up. A separate analysis of the X:BOT per-protocol and completers sample also found that compared to XR-NTX, BUP-NX had significantly greater proportions of opioid-positive urine tests (Mitchell et al., 2021). These findings may be related to the different pharmacological profiles of naltrexone and buprenorphine. While patients are within 28 days of their last XR-NTX injection, opioid effects are fully blocked for most patients and there is typically less opioid use (Nunes et al., 2020). Risk of opioid use and relapse increases when patients miss the next injection. In contrast, sublingual BUP-NX depends on daily adherence and patients may be more likely to intermittently miss doses and are more vulnerable to opioid use at those times. Another consideration when comparing these medications is that there was a substantial induction hurdle for injectable naltrexone in the parent study with 28% dropping out of treatment before induction (versus 6% in the buprenorphine group); and nearly all induction failures had early relapse (Lee et al., 2018).

Different measurements provide different views of treatment outcomes. The outcome of opioid abstinence may not be the best indicator of successful treatment. OUD is a chronic condition and improvement in use patterns may facilitate important recovery goals without complete abstinence. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with daily dosing and individuals may be able to use opioids intermittently but not necessarily meet criteria for relapse, while still demonstrating improved clinical and psychosocial outcomes. A recent X:BOT analysis by our group found that more individuals on XR-NTX at 36-week follow-up were abstinent from non-prescribed opioids compared to BUP-NX (53% versus 23%), but did not differ significantly across other opioid and substance use outcomes (Greiner et al., 2021). This study’s finding of greater rates of recent abstinence at 36 weeks in those treated with XR-NTX complements, but does not contradict or reverse the main findings of the parent study that rates of study-defined relapse were greater at 24 weeks in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and no different in the per protocol analysis.

Severe baseline HAM-D scores were negatively associated with opioid abstinence; consistent with many other studies that suggest baseline depressive symptoms and/or a prior diagnosis of depression are linked to more severe opioid use and other substance use disorder outcomes (Hasin et al., 2002; Najt et al., 2011; Nunes et al., 2004; Rounsaville et al., 1986). However, a secondary analysis of a large, multi-site randomized trial of buprenorphine for prescription opioid dependence found that a diagnosis of lifetime major depressive disorder had the strongest association with better outcomes for OUD. This counterintuitive finding may be related to the potential antidepressant properties of buprenorphine (Peciña et al., 2019; Saxena & Bodkin, 2019) or could also be related to a greater motivation to engage in treatment among those with a depression history. A subsequent analysis of these data (Peckham et al., 2020) did not find evidence for buprenorphine treatment leading to a reduction in depressive symptoms. Regardless of medication choice, treatment of OUD and other substance use disorders leads to improvement in depressive symptoms, (Dean et al., 2004; Krupitsky et al., 2016; Latif et al., 2019; Mysels et al., 2011; Romero‐Gonzalez et al., 2017). More research is needed examining the complex interplay between psychiatric and substance use disorders and treatment outcomes.

With regard to other substance use, baseline sedative use was found to be negatively associated with opioid abstinence. Other studies have shown that in addition to sedative use (Dreifuss et al., 2013; Naji et al., 2016; Nosyk et al., 2013), cocaine (Darke et al., 2007; Joe et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 2018) and heavy alcohol (Flynn et al., 2003) use were associated with non-abstinence and worse opioid use outcomes. There is a need for comprehensive and integrated treatment to address comorbid psychiatric and other substance use disorders among individuals with OUD.

Hispanic participants were less likely to be opioid abstinent (compared to non-Hispanic participants), similar to other trials (Alegría et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2018). A previous study found that Hispanic individuals were less likely to be in active treatment (22% versus 38%), more likely to report not receiving the necessary treatment services (27% of Hispanics compared to 13% of whites), more likely to experience delays in care (23% versus 11%), and tended to be less satisfied with substance use disorder treatment compared to white respondents (Wells et al., 2001). In recent years, the opioid epidemic has significantly impacted minorities with a dramatic increase in opioid use and overdose deaths among Hispanic, African American, and American Indian/Alaska Native populations (The Opioid Crisis and the Hispanic/Latino Population: An Urgent Issue., 2020). There is an urgent need to better identify needs, understand cultural contexts of OUD treatments, identify potential barriers to care, and adapt models of care to improve outcomes among minoritized populations.

Strengths of the current analysis include the relatively high follow-up rate at week 36 (75% of the original sample), and the availability of diverse sociodemographic and treatment characteristics. Limitations of this report include that this was a secondary analysis and was not randomized or part of an a priori design. As statistical tests were not corrected for multiple comparisons, it is crucial that all findings are considered preliminary, and need replication and validation in future research. Non-prescribed opioid abstinence was self-reported and may include recall error or other biases; however prior studies have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity of such data in research settings (Carey, 1997; Fals-Stewart et al., 2000). Opioid abstinence was operationalized differently than in the parent study and missing urine samples at follow-up assessments were not considered to be positive since some assessments were conducted by phone at week 36, albeit a small proportion (49 (11%) of participants). Medication status was based on patient report and did not include confirmatory urine screening for opioid agonists (buprenorphine or methadone) or documented administration of XR-NTX. Associations between treatment participation and the outcome of opioid abstinence may not be causal, but rather reflect motivation and thus inherently better outcome at follow-up. Lastly, these results may not be generalizable to individuals with OUD who initiate medication in an outpatient setting. XR-NTX often requires an inpatient treatment admission whereas buprenorphine can be started immediately during an inpatient or outpatient admission; the main study recruited and enrolled participants while they were in an inpatient setting.

5. Conclusions

In summary, a substantial proportion of participants were available at follow-up (75% of the original sample), were on MOUD (53%), and reported past-month abstinence from non-prescribed opioids (33%) at 36 weeks (three months or longer after study-provided treatment ended). A minority of patients off medication reported abstinence from non-prescribed opioids and future research should explore characteristics of patients that may be more successful off medication or after a certain amount of time on medication. More research is needed exploring key sociocultural and contextual considerations such as access to care and cultural responsiveness in the delivery of treatment interventions for Hispanic and other minoritized populations with OUD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the participants, the sites, and the staff involved in this study, including the leadership at the Greater New York Node of NIDA Clinical Trials Network (CTN) and the CTN Data and Statistics Center (CCC).

Funding:

The primary study and secondary data analyses reported here were supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA): UG1 DA013035 and T32 DA007294. For the X:BOT study, Suboxone® was donated by Indivior (formerly Reckitt-Benckiser).

Declarations of Competing Interest:

Dr. Edward V Nunes has been a Principal Investigator or Co-Investigator on studies that received donated or discounted medication from Alkermes PLC, Indivior PLC (formerly Reckitt-Benckiser) and Braeburn-Camurus (CAM-2038), and donated digital therapeutic from Pear Therapeutics, as Co-Investigator on a study funded by Alkermes and Investigator on a study funded by Braeburn-Camurus. Dr. Nunes has served as an uncompensated consultant to Alkermes, Camurus, and Pear Therapeutics. He has no relevant equity, intellectual property, compensated consulting, travel or other arrangements with any of these entities.

Dr. John Rotrosen has been a Principal Investigator or a Co-Investigator on studies for which support in the form of donated or discounted medication and/or funds has been, or will be, provided by Alkermes, PLC. (Vivitrol®, extended-release injectable naltrexone), by Indivior, PLC. (formerly Reckitt-Benckiser; Suboxone®, buprenorphine-naloxone combination), and by Braeburn-Camurus (CAM-2038); and digital therapeutics by Pear Therapeutics, by ACHESS, and by Datacubed. In addition, studies in planning are anticipating support from Alkermes or Indivior. For the X:BOT study, Vivitrol® was purchased and buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone®) was donated by Indivior. Dr. Rotrosen served as an uncompensated member of an Alkermes study Steering Committee. He has no relevant equity, intellectual property, compensated consulting, travel or other arrangements with any of these entities.

Dr. Joshua D Lee is Principal Investigator of multiple NIH-funded studies receiving in-kind study medication from Alkermes and Indivior. He is Co-Investigator of an Investigator Sponsored Study funded by Indivior. He has no relevant equity, intellectual property, compensated consulting, travel or other arrangements with Indivior or Alkermes.

Dr. Marc Fishman has served as a consultant for Alkermes and Drug Delivery LLC, and an investigator on a study funded by Alkermes.

The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ahmad F, Rossen L, & Sutton P (2020). Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Page JB, Hansen H, Cauce AM, Robles R, Blanco C, Cortes DE, Amaro H, Morales A, & Berry P (2006). Improving drug treatment services for Hispanics: Research gaps and scientific opportunities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 84 Suppl 1, S76–84. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey GL, Herman DS, & Stein MD (2013). Perceived Relapse Risk and Desire for Medication Assisted Treatment among Persons Seeking Inpatient Opiate Detoxification. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(3), 302–305. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA (2013). Mortality After Prison Release: Opioid Overdose and Other Causes of Death, Risk Factors, and Time Trends From 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 592. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB (1997). Reliability and validity of the time-line follow-back interview among psychiatric outpatients: A preliminary report. 11(1), 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Yu E, Rothenberg JL, Kleber HD, Kampman K, Dackis C, & O’Brien CP (2006). Injectable, Sustained-Release Naltrexone for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(2), 210. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Marel C, Slade T, Ross J, Mills KL, & Teesson M (2015). Patterns And Correlates Of Sustained Heroin Abstinence: Findings From The 11-Year Follow-Up Of The Australian Treatment Outcome Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(6), 909–915. 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ross J, Mills KL, Williamson A, Havard A, & Teesson M (2007). Patterns of sustained heroin abstinence amongst long-term, dependent heroin users: 36 months findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS). Addictive Behaviors, 32(9), 1897–1906. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AJ, Bell J, Christie MJ, & Mattick RP (2004). Depressive symptoms during buprenorphine vs. methadone maintenance: Findings from a randomised, controlled trial in opioid dependence. European Psychiatry, 19(8), 510–513. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Foss MA, & Scott CK (2007). An eight-year perspective on the relationship between the duration of abstinence and other aspects of recovery. Evaluation Review, 31(6), 585–612. 10.1177/0193841X07307771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreifuss JA, Griffin ML, Frost K, Fitzmaurice GM, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Selzer J, Hatch-Maillette M, Sonne SC, & Weiss RD (2013). Patient characteristics associated with buprenorphine/naloxone treatment outcome for prescription opioid dependence: Results from a multisite study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131(1–2), 112–118. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, & Rutigliano P (2000). The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 134–144. 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Joe GW, Broome KM, Simpson DD, & Brown BS (2003). Recovery from opioid addiction in DATOS. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25(3), 177–186. 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00125-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehl L, Nunes E, Quitkin F, & Hilton I (1993). Social networks and methadone treatment outcome: The costs and benefits of social ties. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 19(3), 251–262. 10.3109/00952999309001617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner MG, Shulman M, Choo T-H, Scodes J, Pavlicova M, Campbell ANC, Novo P, Fishman M, Lee JD, Rotrosen J, & Nunes EV (2021). Naturalistic follow-up after a trial of medications for opioid use disorder: Medication status, opioid use, and relapse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 131, 108447. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M (1960). A RATING SCALE FOR DEPRESSION. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23(1), 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Liu X, Nunes E, McCloud S, Samet S, & Endicott J (2002). Effects of Major Depression on Remission and Relapse of Substance Dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(4), 375. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.4.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, & Anglin MD (2001). A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(5), 503–508. 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y-I (2007). Predicting long-term stable recovery from heroin addiction: Findings from a 33-year follow-up study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 26(1), 51–60. 10.1300/J069v26n01_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y-I, Evans E, Huang D, Weiss R, Saxon A, Carroll KM, Woody G, Liu D, Wakim P, Matthews AG, Hatch-Maillette M, Jelstrom E, Wiest K, McLaughlin P, & Ling W (2016). Long-term outcomes after randomization to buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 111(4), 695–705. 10.1111/add.13238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Simpson DD, & Broome KM (1999). Retention and patient engagement models for different treatment modalities in DATOS. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 57(2), 113–125. 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00088-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, & Silverman BL (2011). Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet (London, England), 377(9776), 1506–1513. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky E, Zvartau E, Blokhina E, Verbitskaya E, Wahlgren V, Tsoy-Podosenin M, Bushara N, Burakov A, Masalov D, Romanova T, Tyurina A, Palatkin V, Yaroslavtseva T, Pecoraro A, & Woody G (2016). Anhedonia, depression, anxiety, and craving in opiate dependent patients stabilized on oral naltrexone or an extended release naltrexone implant. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 42(5), 614–620. 10.1080/00952990.2016.1197231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif Z-H, Šaltyte Benth J, Solli KK, Opheim A, Kunoe N, Krajci P, Sharma-Haase K, & Tanum L (2019). Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia Among Adults With Opioid Dependence Treated With Extended-Release Naltrexone vs Buprenorphine-Naloxone: A Randomized Clinical Trial and Follow-up Study. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(2), 127. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Nunes EV, Novo P, Bachrach K, Bailey GL, Bhatt S, Farkas S, Fishman M, Gauthier P, Hodgkins CC, King J, Lindblad R, Liu D, Matthews AG, May J, Peavy KM, Ross S, Salazar D, Schkolnik P, … Rotrosen J (2018). Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 391(10118), 309–318. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32812-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Stephens MAC, Mudric T, Strain EC, Bigelow GE, & Johnson RE (2005). Predictors of outcome in LAAM, buprenorphine, and methadone treatment for opioid dependence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 13(4), 293–302. 10.1037/1064-1297.13.4.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, & Davoli M (2003). Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD002209. 10.1002/14651858.CD002209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, & Davoli M (2004). Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD002207. 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna RM (2017). Treatment use, sources of payment, and financial barriers to treatment among individuals with opioid use disorder following the national implementation of the ACA. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 179, 87–92. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, & Argeriou M (1992). The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 9(3), 199–213. 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MM, Schwartz RP, Choo T-H, Pavlicova M, O’Grady KE, Gryczynski J, Stitzer ML, Nunes EV, & Rotrosen J (2021). An alternative analysis of illicit opioid use during treatment in a randomized trial of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone: A per-protocol and completers analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 219, 108422. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysels DJ, Cheng WY, Nunes EV, & Sullivan MA (2011). The association between naltrexone treatment and symptoms of depression in opioid-dependent patients. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(1), 22–26. 10.3109/00952990.2010.540281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naji L, Dennis BB, Bawor M, Plater C, Pare G, Worster A, Varenbut M, Daiter J, Marsh DC, Desai D, Thabane L, & Samaan Z (2016). A Prospective Study to Investigate Predictors of Relapse among Patients with Opioid Use Disorder Treated with Methadone: Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 10.4137/SART.S37030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najt P, Fusar-Poli P, & Brambilla P (2011). Co-occurring mental and substance abuse disorders: A review on the potential predictors and clinical outcomes. Psychiatry Research, 186(2), 159–164. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Anglin MD, Brecht M-L, Lima VD, & Hser Y-I (2013). Characterizing durations of heroin abstinence in the California Civil Addict Program: Results from a 33-year observational cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 177(7), 675–682. 10.1093/aje/kws284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Krupitsky E, Nangia N, Silverman BL, Akerman SC, & Sullivan MA (2020). Opioid use and dropout from extended-release naltrexone in a controlled trial: Implications for mechanism. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 115(2), 239–246. 10.1111/add.14735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Lee JD, Sisti D, Segal A, Caplan A, Fishman M, Bailey G, Brigham G, Novo P, Farkas S, & Rotrosen J (2016). Ethical and Clinical Safety Considerations in the Design of an Effectiveness Trial: A Comparison of Buprenorphine versus Naltrexone Treatment for Opioid Dependence. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 51, 34–43. 10.1016/j.cct.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Pavlicova M, Hu M-C, Campbell A, Miele G, Hien D, & Klein DF (2011). Baseline matters: The importance of covariation for baseline severity in the analysis of clinical trials. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(5), 446–452. 10.3109/00952990.2011.596980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Sullivan MA, & Levin FR (2004). Treatment of depression in patients with opiate dependence. Biological Psychiatry, 56(10), 793–802. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peciña M, Karp JF, Mathew S, Todtenkopf MS, Ehrich EW, & Zubieta J-K (2019). Endogenous opioid system dysregulation in depression: Implications for new therapeutic approaches. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(4), 576–587. 10.1038/s41380-018-0117-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham AD, Griffin ML, McHugh RK, & Weiss RD (2020). Depression history as a predictor of outcomes during buprenorphine-naloxone treatment of prescription opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 213, 108122. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin R, & de Charro F (2001). EQ-5D: A measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 337–343. 10.3109/07853890109002087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero‐Gonzalez M, Shahanaghi A, DiGirolamo GJ, & Gonzalez G (2017). Buprenorphine-naloxone treatment responses differ between young adults with heroin and prescription opioid use disorders. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(8), 838–844. 10.1111/ajad.12641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Weissman MM, & Kleber HD (1986). Prognostic Significance of Psychopathology in Treated Opiate Addicts: A 2.5-Year Follow-up Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43(8), 739–745. 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080025004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena PP, & Bodkin JA (2019). Opioidergic Agents as Antidepressants: Rationale and Promise. CNS Drugs, 33(1), 9–16. 10.1007/s40263-018-0584-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Laudet A, Funk RR, & Simeone RS (2011). Surviving Drug Addiction: The Effect of Treatment and Abstinence on Mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 101(4), 737–744. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, & Sobell M (2000). Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB). In Handbook of Psychiatric Measures (pp. 477–479). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M, Strehle J, Rehm J, Bühringer G, & Wittchen H-U (2017). Six-Year Outcome of Opioid Maintenance Treatment in Heroin-Dependent Patients: Results from a Naturalistic Study in a Nationally Representative Sample. European Addiction Research, 23(2), 97–105. 10.1159/000468518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001; NSDUH Series H-55, p. 114). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MA, Rothenberg JL, Vosburg SK, Church SH, Feldman SJ, Epstein EM, Kleber HD, & Nunes EV (2006). Predictors of retention in naltrexone maintenance for opioid dependence: Analysis of a stage I trial. The American Journal on Addictions, 15(2), 150–159. 10.1080/10550490500528464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Opioid Crisis and the Hispanic/Latino Population: An Urgent Issue. (2020). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Behavioral Health Equity. [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, & Garrison-Diehn C (2016). Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 35(1), 22–35. 10.1080/10550887.2016.1100960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND (2020). Collision of the COVID-19 and Addiction Epidemics. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(1), 61–62. 10.7326/M20-1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Marcovitz DE, Hilton BT, Fitzmaurice GM, McHugh RK, & Carroll KM (2019). Correlates of opioid abstinence in a 42-month post-treatment naturalistic follow-up study of prescription opioid dependence. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(2). 10.4088/JCP.18m12292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, Gardin J, Griffin ML, Gourevitch MN, Haller DL, Hasson AL, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Kosinski AS, Lindblad R, McCance-Katz EF, Provost SE, Selzer J, Somoza EC, … Ling W (2011). Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: A 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(12), 1238–1246. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Griffin ML, Provost SE, Fitzmaurice GM, McDermott KA, Srisarajivakul EN, Dodd DR, Dreifuss JA, McHugh RK, & Carroll KM (2015). Long-term outcomes from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 150, 112–119. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, & Sherbourne C (2001). Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(12), 2027–2032. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Levin FR, & Olfson M (2019). Development of a Cascade of Care for responding to the opioid epidemic. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(1), 1–10. 10.1080/00952990.2018.1546862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Samples H, Crystal S, & Olfson M (2020). Acute Care, Prescription Opioid Use, and Overdose Following Discontinuation of Long-Term Buprenorphine Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(2), 117–124. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19060612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Evans E, Mooney LJ, Saxon A, Kelleghan A, Yoo C, & Hser Y-I (2018). Correlates of long-term opioid abstinence after randomization to methadone versus buprenorphine/naloxone in a multi-site trial. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology : The Official Journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology, 13(4), 488–497. 10.1007/s11481-018-9801-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.