Abstract

Protective immune responses against respiratory pathogens, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and influenza virus, are initiated by the mucosal immune system. However, most licensed vaccines are administered parenterally and are largely ineffective at inducing mucosal immunity. The development of safe and effective mucosal vaccines has been hampered by the lack of a suitable mucosal adjuvant. In this study we explore a class of adjuvant that harnesses mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells. We show evidence that intranasal immunization of MAIT cell agonists co-administered with protein, including the spike receptor binding domain from SARS-CoV-2 virus and hemagglutinin from influenza virus, induce protective humoral immunity and immunoglobulin A production. MAIT cell adjuvant activity is mediated by CD40L-dependent activation of dendritic cells and subsequent priming of T follicular helper cells. In summary, we show that MAIT cells are promising vaccine targets that can be utilized as cellular adjuvants in mucosal vaccines.

Keywords: mucosal vaccine, adjuvant, MAIT cell, humoral immunity, IgA, TFH cell, dendritic cell, influenza, SARS-CoV-2

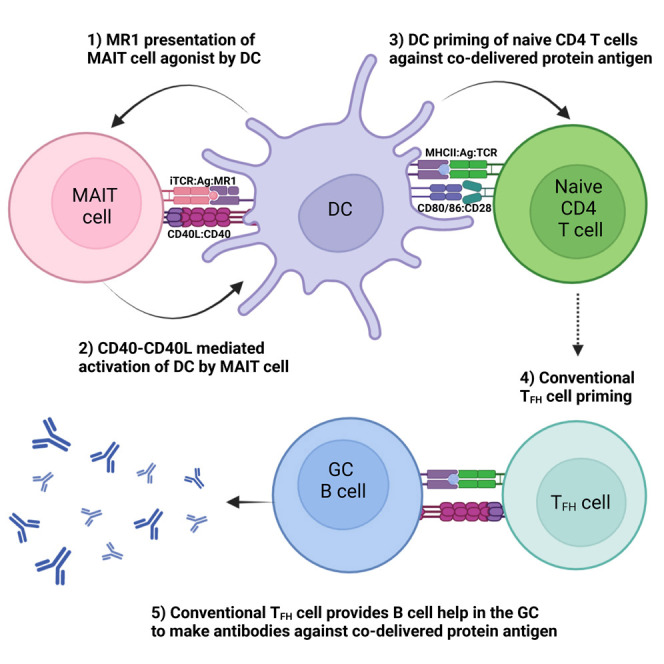

Graphical abstract

Respiratory pathogens remain a major cause of mortality globally, and there is a significant need for mucosal vaccines. Pankhurst et al. show that MAIT cell agonists can function as mucosal adjuvants that promote protective virus-specific immunity against influenza and SARS-CoV-2.

Introduction

Most infectious agents invade the body through the mucosa, yet the anatomic compartmentalization of mucosal immunity is not incorporated into the design of most licensed vaccines, which are typically administered by parenteral routes, commonly by intramuscular (i.m.) or subcutaneous (s.c.) injection. While parenteral vaccination can be efficacious, notably where the infected tissues are permeable to transudation by serum antibodies, immune responses provoked in the mucosal tissue possess additional features, specialized for defense at these local sites.1 Mucosal vaccination, such as via oral and nasal routes, may therefore be more likely to elicit antigen-specific immune responses that home to mucosal tissues to neutralize or eliminate pathogens at the site of infection.1 Such responses will include T cells and B cells that respond initially to vaccine antigens that drain to mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues; these cells then transit via the lymph and circulation to specifically seed mucosal sites as effector and memory cells. Importantly, mucosal delivery is more likely than parenteral administration to lead to mucosal immunoglobulin A (IgA), a key immune factor responsible for preventing pathogen invasion of the host to cause infection.2

Currently the only approved vaccines delivered by the intranasal (i.n.) route (as nasal sprays) are the live attenuated influenza vaccines FluMist3 and Nasovac-S.4 However, owing to inconsistent protective efficacy perhaps reflecting unwanted biasing of the immune response to previously encountered influenza strains, and because of safety concerns regarding the use of live viral strains, new subunit vaccines with refined specificity are needed.5 As subunit vaccines typically require immune adjuvants to achieve efficacious responses, more work is required to develop safe and effective adjuvants that can be used by the nasal route.

Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are unconventional T cells with innate-like effector functions that are abundant in mucosal tissues.6 , 7 While they have been shown to have anti-microbial activity, specifically by recognizing non-protein agonists derived from vitamin B2 riboflavin synthesis pathways in some microbial species,8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 they also have broader immunomodulatory activities that could potentially be exploited in vaccination strategies. An attractive feature in this regard is the limited diversity of the MAIT T cell receptor (TCR), which has been highly conserved throughout mammalian evolution, and the lack of polymorphism of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I)-related molecule (MR1), the non-classical MHC I molecule on which agonists are presented; MAIT cell activation can therefore be achieved in all individuals with the same agonist compounds. Agonists that have been identified include 5-(2-oxoethylideneamino)-6-D-ribitylaminouracil (5-OE-RU) and 5-(2-oxopropylideneamino)-6-D-ribitylaminouracil (5-OP-RU), which are compounds formed naturally through non-enzymatic condensation of the vitamin B pathway derivative 5-amino-6-D-ribitylaminouracil (5-A-RU) with glycolysis by-products glyoxal and methylglyoxal (MG), respectively.9 In animal models, i.n. administration of MAIT cell agonists combined with Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists13 , 14 or interleukin-23 (IL-23) cytokine15 has shown to activate MAIT cells in the lung. Importantly, in vitro studies with human cells have shown that activation of MAIT cells with 5-A-RU/MG can lead to enhanced dendritic cell (DC) function.16 As activation of DCs is necessary for the development and differentiation of effector T cell responses, including the T follicular helper (TFH) cells required for B cell activation, formation of germinal center (GC) reactions, and production of high-affinity antibodies,17 it is possible that agonists such as 5-OP-RU could act as a mucosal adjuvant when delivered with antigen.

In this study we evaluated the capacity of 5-A-RU/MG to enhance immunogenicity of protein antigens when co-administered by i.n. instillation. We show that activation of MAIT cells by this route provides an adjuvant effect, promoting CD40L-dependent activation of lung-associated DCs, expansion of TFH cells, and production of antigen-specific mucosal IgA. When combined with protein antigens from SARS-CoV-2 or influenza, SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization was induced and complete protection from influenza A virus (IAV) challenge was observed, respectively, together highlighting the potential to utilize MAIT cells as “cellular adjuvants” in vaccine design.

Results

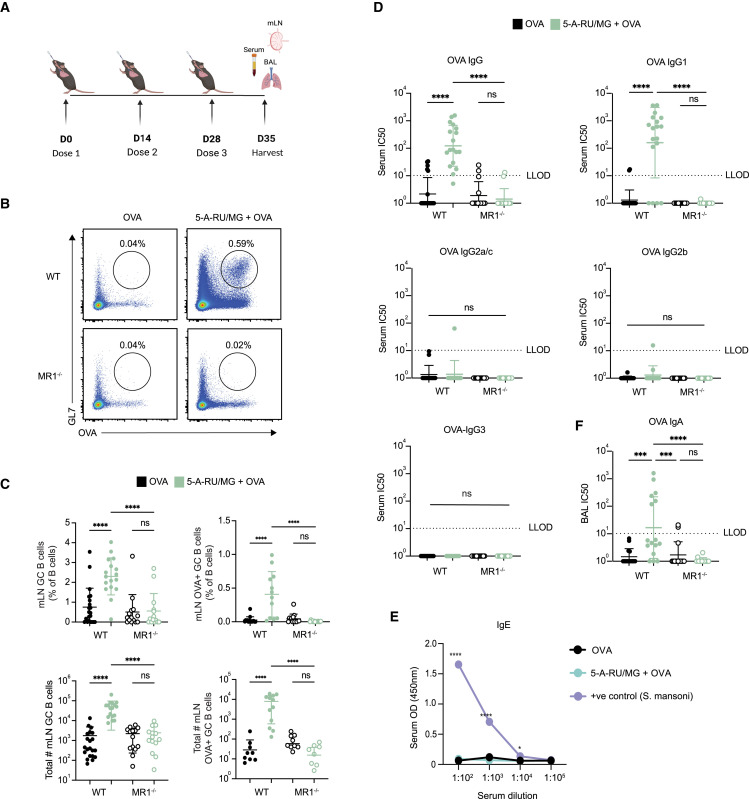

Intranasal co-administration of an MAIT cell agonist with an antigen enhances specific antibody response

Studies conducted in vitro have shown that MAIT cells are able to induce the production of antibodies by B cells;18 however, the extent of their ability to promote such responses in vivo has not yet been investigated. To determine whether the activation of MAIT cells could promote humoral responses toward co-delivered antigen, we established an immunization regimen to measure antigen-specific B cells and antibody responses (Figure 1 A). I.n. administration of 5 nmol EndoGrade ovalbumin (OVA) protein alone, or in combination with 75 nmol freshly prepared 5-OP-RU (a 1:10 ratio of 5-A-RU and MG mixed immediately prior to use, hereafter referred to as “5-A-RU/MG”), was given to mice three times at 2-week intervals. One week following the third dose, the proportions of OVA-specific B cells were determined in the lung-draining mediastinal lymph node (mLN) by flow cytometry using biotinylated OVA protein. The levels of OVA-specific antibodies in the serum, and mucosal antibodies in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), were also assessed by ELISA. As seen in Figures 1B and 1C, the total frequency and number of GC B cells (B220+ GL7+ IgD−) was significantly greater in C57BL/6 (wild-type [WT]) mice treated with 5-A-RU/MG + OVA compared with mice treated with OVA alone, and the proportion of OVA-specific (B220+ GL7+ OVA-biotin+) B cells was significantly enhanced in this group. In contrast, there was no expansion of OVA-specific B cells in MR1−/− mice (which lack MAIT cells) treated with 5-A-RU/MG + OVA, confirming the required role of MAIT cells in this response (Figure 1C). The detection of OVA-specific B cells by flow cytometry correlated with the presence of circulating OVA-specific serum IgG antibodies, which was also dependent on the presence of MR1 (Figure 1D). The antibody responses induced by MAIT cell agonist treatment were dominated by IgG1, whereas minimal levels of IgG2a/c, IgG2b, or IgG3 were detected. Serum IgE was not generated after i.n. 5-A-RU/MG + OVA, whereas serum taken from mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni had high IgE levels, as expected for this positive control (Figure 1E). Given that IgA present in the airway lumen provides neutralizing activity in mucosal sites,19 it was notable that levels of OVA-specific IgA were significantly enhanced in mice treated with 5-A-RU/MG + OVA (Figure 1F). Collectively, these data suggest that MR1-restricted MAIT cells have the capacity to promote mucosa-associated antigen-specific B cells, serum IgG, and mucosal IgA antibodies; agonists for MAIT cells can therefore be considered as mucosal vaccine adjuvants.

Figure 1.

Intranasal co-administration of an MAIT cell agonist with an antigen enhances specific antibody response

(A) WT or MR1−/− mice were treated i.n. with either 5 nmol OVA alone or in combination with 75 nmol 5-A-RU and 750 nmol MG, three times spaced 2 weeks apart. One week after the final booster dose, mLN, serum, and BAL were harvested for analysis.

(B) Representative flow-cytometry plots of mLN OVA-specific GC B cells (TCRβ− B220+ GL7+ OVA-biotin-SAV+). Full gating strategy is detailed in Figure S7.

(C) Frequency and total number of GC B cells and OVA-specific GC B cells in the mLN.

(D) Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) from serum OVA-specific IgG ELISA.

(E) Optical density (OD; 450 nm) from total IgE serum ELISA.

(F) IC50 from OVA-specific BAL IgA ELISA. Lower limit of detection (LLOD) was set at an IC50 of 10; IC50 values below zero were marked as an IC50 of 1 (D and F).

Data represent a combination of n = 3 (B–D) and n = 2 (F) individual experiments, with n = 3–10 mice per group, per experiment. Graphs depicted as mean (E) and mean ± SD (C and D). One-way (C, D, and F) or two-way (E) ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed, with ns (not significant), p ˃ 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001.

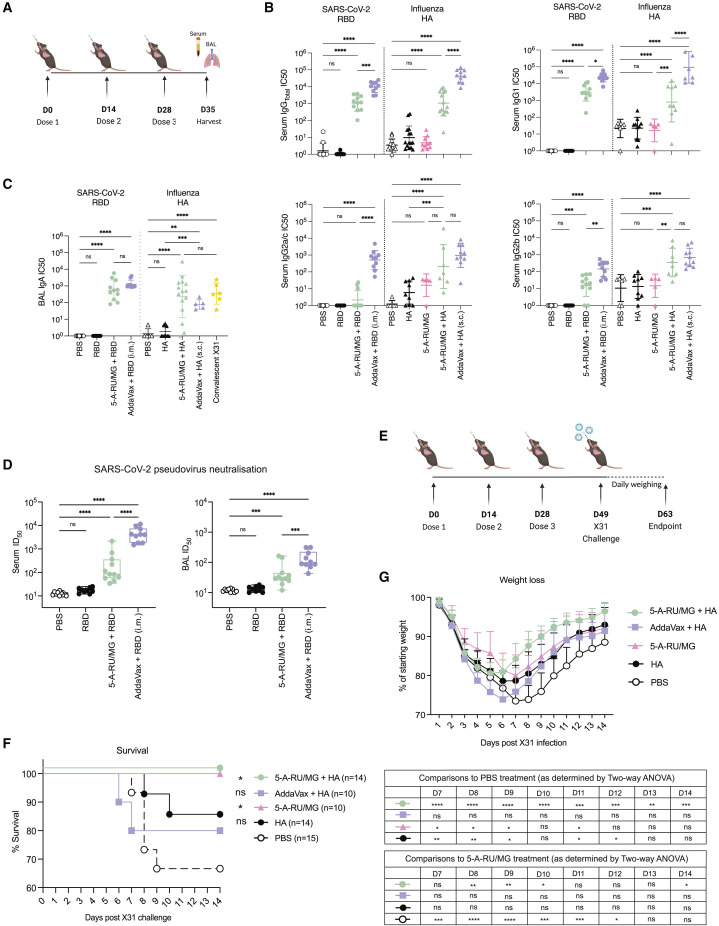

Intranasal co-administration of 5-A-RU/MG with viral antigen induces protective responses

We next determined whether MAIT cell adjuvant activity could promote the development of functional virus-specific antibodies, which provide protection by targeting and neutralizing viral proteins involved in host cell entry.20 , 21 , 22 C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.n. with a tandem dimer of the receptor binding domain (RBD) spike protein from SARS-CoV-2 virus or hemagglutinin (HA) protein from influenza virus, either alone or in combination with 5-A-RU/MG as outlined in Figure 2 A. As a positive control, viral proteins were also adjuvanted with the commercial adjuvant AddaVax and delivered via the parenteral route. One week after the final boost, significantly enhanced levels of anti-RBD and anti-HA IgG were observed in the serum of mice immunized with virus antigen adjuvanted with either 5-A-RU/MG or AddaVax compared with antigen alone (Figure 2B). The antibody response induced by MAIT agonist treatment was similar in magnitude to responses induced by natural killer T (NKT) cell agonist α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer; Figure S1). The IgG1 isotype dominated the response in both adjuvanted groups, with lower titers of virus-specific IgG2a/c and IgG2b (Figure 2B). Titers of virus-specific IgA in the BAL fluid were enhanced with 5-A-RU/MG treatment compared with unadjuvanted groups (Figure 2C) and were comparable with IgA titers measured after i.n. challenge with IAV (X31), known to induce mucosal IgA.23 Interestingly, parenteral immunization of AddaVax + viral antigen generated similar levels of IgA (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Intranasal co-administration of 5-A-RU/MG with a viral antigen induces protective response

(A) WT mice were treated i.n. with 10 μg of HA protein alone, 50 μg of RBD protein alone, or admixed with 5-A-RU/MG. AddaVax + 10 μg HA (s.c.) or 50 μg RBD (i.m.) was delivered at 1:1 (v/v).

(B) IC50 from RBD-specific and HA-specific IgG ELISAs performed on serum.

(C) IC50 from RBD-specific and HA-specific IgA ELISA performed on BAL.

(D) Neutralizing titer 50 (NT50) from pseudovirus neutralization assay.

(E) Schematic of experimental design. Mice were challenged with 2 HAU of X31 IAV.

(F and G) Survival and weight loss.

Data represent a combination of n = 3 (B, F, and G), or n = 2 (C and D) individual experiments, with n = 4–10 mice per group, per experiment. Graphs depicted as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (B–D), Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparison (F), or two-way ANOVA (G) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (B–D and G) and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (F). Comparisons displayed in (F) compare each treatment group with PBS treatment. Comparisons displayed in the tables in (G) compare each treatment group with PBS or 5-A-RU/MG treatment at days 7–14 post X31 challenge. ns, p ˃ 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001. See also Figure S1.

To assess the protective capacity of the antibody response generated by i.n. 5-A-RU/MG and RBD-dimer protein, we measured the neutralizing antibody titers in serum and BAL fluid of immunized mice. Using a pseudotyped lentivirus expressing the spike protein from ancestral SARS-CoV-2, we assessed the ability of antibodies to block infection of cells expressing human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (Figure 2D). While i.n. immunization of RBD alone failed to provide detectable neutralizing activity, the addition of 5-A-RU/MG promoted neutralizing antibodies in both serum and airways, albeit lower than in the AddaVax adjuvanted group (Figure 2D).

A live influenza challenge model was carried out to assess the protective capacity of i.n. immunization of 5-A-RU/MG and HA protein. Three weeks after the last boost, mice were challenged i.n. with 2 hemagglutinating units (HAU) of X31 IAV and monitored for weight loss (Figure 2E). Animals with weight loss exceeding 30% of their initial weight were culled. Because activation of MAIT cells can stimulate a direct antiviral response,24 , 25 , 26 a group of mice that had received 5-A-RU/MG without HA protein (according to the same administration regimen) was included for comparison. Indeed, treatment with the MAIT cell agonist alone proved to be sufficient to confer protection, with all animals surviving virus challenge (Figure 2F). However, it was notable that mice treated with HA together with the MAIT cell agonist gained weight at a faster rate (Figure 2G), likely reflecting the induced HA-specific adaptive response; again, all animals survived infection (Figure 2F). Surprisingly, mice immunized s.c. with HA protein and AddaVax lost weight more rapidly than the other treatment groups, and almost 20% of animals did not survive the infection (Figures 2F and 2G), suggesting that the use of MAIT cell agonists as cellular adjuvants promotes an immune response that limits severity of disease caused by a live influenza infection.

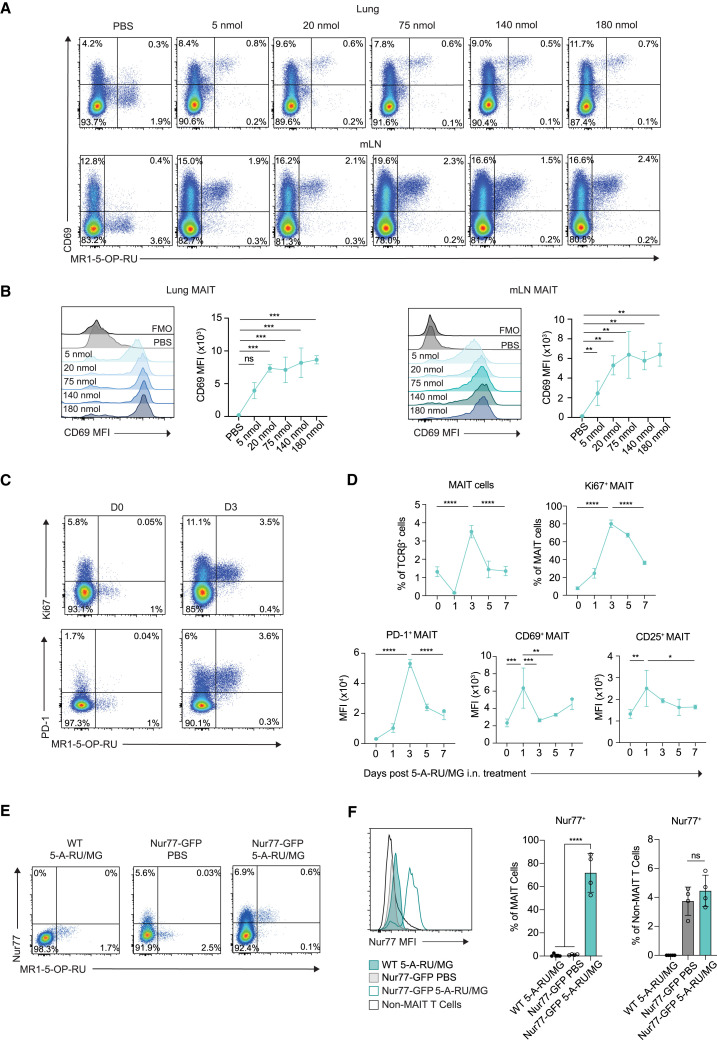

Intranasal administration of 5-A-RU/MG evokes MAIT cell activation and proliferation in the lung

To gain a better understanding of the role for MAIT cells during the i.n. immunization regimen, we examined the response of lung-associated MAIT cells to increasing concentrations of 5-A-RU/MG. Mice were i.n. administered either 5, 20, 75, 140, or 180 nmol 5-A-RU, in each case mixed with 10-fold MG directly before use to form 5-OP-RU. Lungs and mLNs were isolated 24 h later to assess MAIT cells by flow cytometry with fluorescent MR1-5-OP-RU tetramers and antibodies against CD69. All doses induced upregulated expression of CD69, indicative of MAIT cell activation, with the dose response leveling off at 75 nmol in both the lung and mLN (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Intranasal administration of 5-A-RU/MG evokes MAIT cell activation and proliferation in the lung

(A) WT mice were treated i.n. with PBS or increasing doses of 5-A-RU with 10× the corresponding amount of MG. Lung and mLNs were collected 24 h later for flow cytometry. Representative flow plots of CD69+ MAIT cells (TCRβ+ B220− CD64− MR1-5-OP-RU tetramer+).

(B) CD69 expression on MAIT cells.

(C) WT mice were treated with 75 nmol 5-A-RU and 750 nmol MG i.n., and lungs were collected at indicated time points. Naive mice were used as baseline day 0. Representative flow plots of Ki67+ and PD-1+ lung MAIT cells.

(D) Frequency of total and Ki67+ MAIT cells in lung. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1, CD69, and CD25 on lung MAIT cells over time.

(E) WT and Nur77-GFP mice were treated with PBS or 5-A-RU/MG i.n., and mLNs were collected 24 h later. Representative flow plots of Nur77+ MAIT cells (TCRβ+ B220− CD64− MR1-5-OP-RU tetramer+ Nur77+).

(F) MAIT cell (TCRβ+ MR1-5-OP-RU tetramer+) and non-MAIT T cell (TCRβ+ MR1-5-OP-RU tetramer−) Nur77 expression and frequency.

Data are representative of n = 2 individual experiments with n = 2–5 mice per group. Graphs depicted as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed, with ns, p ˃ 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001. See also Figures S2, S3, and S5.

To examine kinetics of the response, mice were treated with 75 nmol 5-A-RU/MG (a dose that led to maximal CD69 upregulation), and MAIT cell phenotype was assessed in the lung tissue over a period of 7 days (Figures 3C and 3D). After 24 h a significant reduction in MAIT cell frequency was observed, consistent with previous reports showing downregulation of the MAIT cell TCR upon initial stimulation.14 Despite this reduced capacity to detect MAIT cells, the cells that could be identified showed clear evidence of activation with significantly enhanced expression of CD69 and CD25, with levels waning over the following days. Expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) also increased but peaked later at day 3 (Figure 3D). The number of MAIT cells detected in the lung peaked at day 3 and reduced to baseline levels by day 5, with peak accumulation coinciding with evidence of proliferation as indicated by Ki67 expression (Figure 3D). MAIT cell frequency and expression of PD-1 and CD69 was similar following three i.n. immunizations of 5-A-RU/MG + OVA protein (Figure S2). Despite MAIT cell activation, there was minimal detection of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interferon-γ [IFN-γ], tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6, IL-12p70, and IL-12p40) in the blood following 5-A-RU/MG treatment (Figure S3).

To confirm that MAIT cells were being stimulated through their invariant TCR via MR1 presentation of agonists, we employed Nur77-GFP mice, which express GFP in response to TCR stimulation in a dose-dependent manner.27 Induced Nur77 expression was detected on 70% of MAIT cells in the mLN at 24 h following i.n. 5-A-RU/MG administration, representing a 60-fold change relative to PBS-treated controls (Figures 3E and 3F). In contrast, there were minimal changes in Nur77 expression of non-MAIT T cells (Figure 3F). Overall, these data show that i.n. 5-A-RU/MG can induce MAIT cell activation, proliferation, and accumulation in the lung and mLN, attributable (at least in part) to direct stimulation via the TCR.

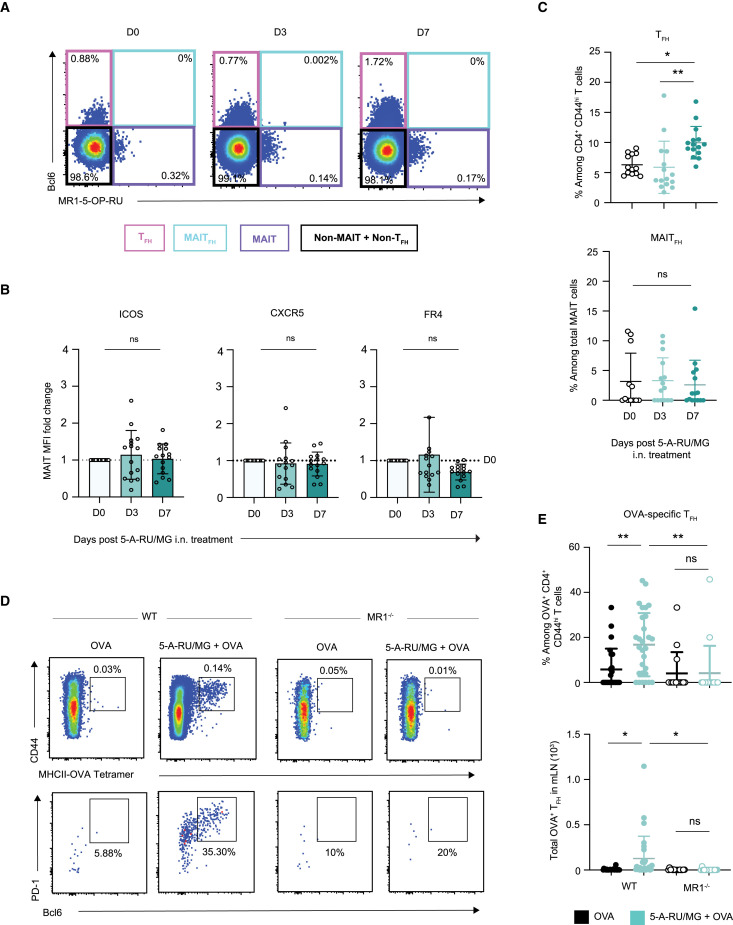

Intranasal co-administration of 5-A-RU/MG + OVA induces OVA-specific TFH cell development

Given the essential role played by TFH cells in humoral immune responses, the induction of this population is an important process in vaccination. To investigate the TFH response induced after i.n. 5-A-RU/MG treatment, expression levels of the TFH-associated molecules B cell lymphoma 6 protein (Bcl6), PD-1, folate receptor 4 (FR4), and C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5) were assessed in the mLN. As MAIT cells share some similarities with NKT cells, and the latter are capable of adopting a TFH-like phenotype and providing direct help to B cells,28 , 29 analysis was conducted on both CD4+ T cell and MAIT cell populations.

As MAIT cell activation and accumulation occurred within the first 3 days following 5-A-RU/MG treatment (Figure 3D) whereas conventional T cell responses typically require more time to achieve a measurable response,30 the expression of TFH-associated molecules was assessed at early (day 3) and later (day 7) time points. The transcription factor Bcl6, which is necessary for TFH differentiation, was only detected within the non-MAIT (negative for MR1-5-OP-RU tetramer) T cell population (Figure 4 A). Furthermore, expression of inducible co-stimulator (ICOS), CXCR5, and FR4 was not upregulated on MAIT cells at day 3 or day 7 after 5-A-RU/MG treatment (Figure 4B). Among conventional CD4+ T cells, expanded populations of Bcl6+ PD-1+ cells were detected in the mLN at day 7 (Figure 4C), suggesting that immunization with 5-A-RU/MG promotes the induction of conventional CD4+ TFH cells. In contrast, Bcl6+PD-1+ MAIT cells did not expand (Figure 4C). To determine whether any of the conventional TFH cells induced were OVA specific, CD4+ T cells with specificity for (one or two) dominant epitopes were identified using a combination of two MHC class II tetramers containing I-A(b)HAAHAEINEA and I-A(b)AAHAEINEA epitopes, respectively (which were labeled with the same fluorophore), then assessed for Bcl6 and PD-1 expression. In vaccinated WT mice, OVA-specific T cells on average represented 0.14% of all CD4+ T cells, and of these an average of 20% expressed a TFH phenotype (Figures 4D and 4E). The development of OVA-specific TFH cells was significantly reduced in unadjuvanted WT mice and in MR1-deficient mice (Figures 4D and 4E), suggesting that mucosal MAIT cell stimulation can drive conventional CD4+ TFH differentiation against co-delivered proteins.

Figure 4.

Intranasal co-administration of 5-A-RU/MG + OVA promotes generation of conventional OVA-specific TFH cells

WT mice were treated i.n. with a single dose of 5-A-RU/MG. Naive (day 0 [D0]) and treated mLN were harvested 3 and 7 days later for flow cytometry. Full gating strategy is detailed in Figure S7.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots of T cells (TCRβ+) expressing MR1-5-OP-RU and Bcl6.

(B) MFI fold change compared with D0 mice of TFH markers ICOS, CXCR5, and FR4 expressed by MAIT cells.

(C) Frequency of conventional TFH (B220− TCRβ+ CD4+ CD44hi Bcl6+ PD-1+) and MAITFH (B220− TCRβ+ CD64− MR1-5-OP-RU+ Bcl6+).

(D) WT and MR1−/− mice were treated i.n. with three doses of either OVA alone or in combination with 5-A-RU/MG, spaced 2 weeks apart. mLNs were harvested 5 days after the final boost for analysis of TFH by flow cytometry. Representative flow plots of OVA-specific CD4+ T cells and OVA-specific TFH cells.

(E) Frequency and total numbers of OVA-specific TFH in the mLN.

Data represent a combination of n = 3 (A–C) or n = 4 (D and E) individual experiments, with n = 3–10 mice per group, per experiment. Graphs depicted as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed, with ns, p ˃ 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

Conventional CD4+ TFH cells are essential for humoral immunity induced by 5-A-RU/MG + OVA

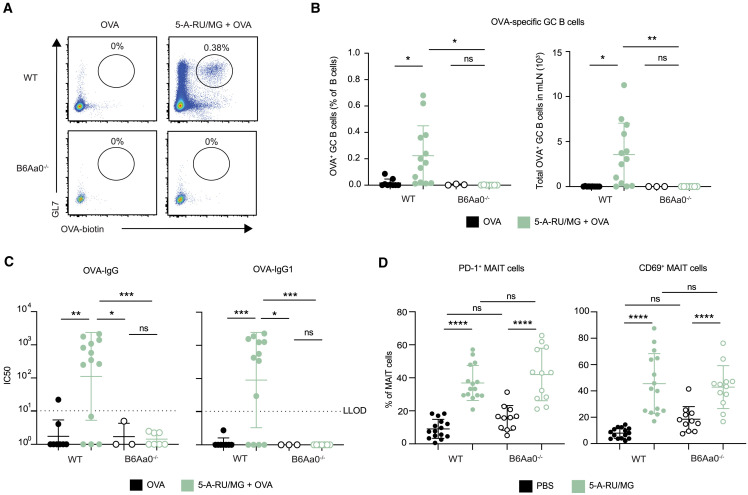

To confirm the role of CD4+ TFH cells in the induction of humoral immunity by treatment with 5-A-RU/MG + OVA, we next assessed the adaptive immune response generated by i.n. immunization in B6Aa0−/− mice, which lack MHC class II molecules and do not produce conventional CD4+ T cells. While B6Aa0−/− mice could raise antibody responses specific for T-independent hapten antigen 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl (Figure S4), they failed to induce OVA-specific GC B cells (Figures 5A and 5B) or OVA-specific serum IgG antibodies (Figure 5C) in response to 5-A-RU/MG + OVA treatment. Importantly, MAIT cell activation remained intact in B6Aa0−/− mice, displaying comparable frequency of MAIT cells expressing CD69 and PD-1 to C57BL/6 (WT) mice (Figure 5D). Taken together, these data show a critical role for conventional TFH cells in the antigen-specific humoral immune response generated by an MAIT cell-based adjuvant mucosal vaccine that activated MAIT cells could not achieve alone.

Figure 5.

Conventional CD4+ TFH cells are essential for humoral immunity induced by 5-A-RU/MG + OVA immunization

WT or B6Aa0−/− mice were treated as in Figure 1A.

(A) Representative flow-cytometry plots of OVA-specific GC B cells (TCRβ− B220+ GL7+ OVA-biotin-SAV+).

(B) Frequencies and total numbers of OVA-specific GC B cells in the mLN.

(C) IC50 from OVA-specific serum IgG ELISA.

(D) WT and B6Aa0−/− mice were treated i.n. with a single dose of PBS or 5-A-RU/MG. After 24 h, lungs were harvested for flow cytometry. Frequency of PD-1 and CD69 expressing MAIT cells (B220− TCRβ+ CD64− MR1-5-OP-RU+). Graphs depicted as mean ± SD.

Data represent a combination of n = 2 (A–C) or n = 3 (D) individual experiments, with n = 3–8 mice per group, per experiment, apart from OVA-only treated B6Aa0−/− mice in (B) and (C), which only had n = 3 mice in total. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed, with ns, p ˃ 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001. See also Figures S4 and S7.

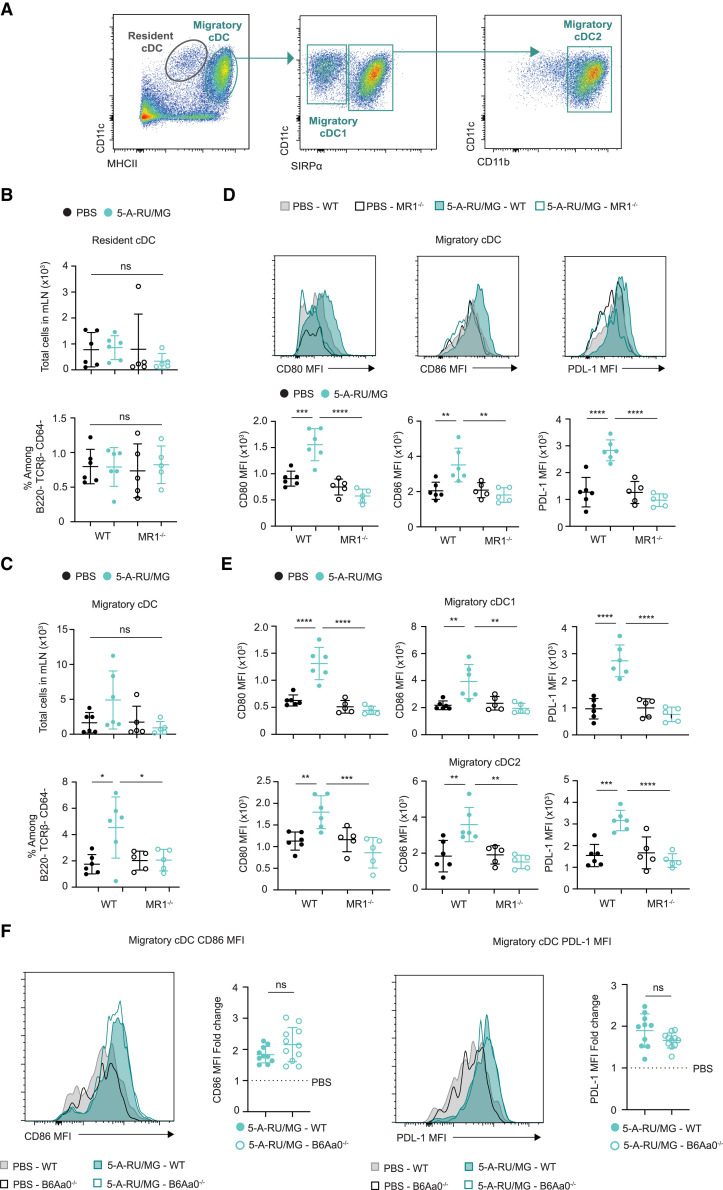

Intranasal administration of 5-A-RU/MG activates migratory DCs

DCs are the vital link between the innate and adaptive immune response and are essential for priming CD4+ TFH cells.31 , 32 , 33 Moreover, a reciprocal relationship between DCs and MAIT cells has been observed in vitro, whereby activated MAIT cells provide stimulating signals to promote maturation of DCs in an MR1-dependent manner.16 The accumulation of the different conventional DC (cDC) subsets was therefore assessed 1 day following i.n. 5-A-RU/MG administration. In the mLN, resident DCs can be identified as MHCIIi ntCD11c+ cells, while migratory DCs can be identified as MHCIIhiCD11c+ cells, the latter representing recent migrants from the lung tissue. Both of these cDC subsets can be further divided into the functionally distinct populations of cDC1 (CD11c+signal regulatory protein α [SIRPα]−) and cDC2 (CD11c+CD11b+SIRPα+) which are responsible for the differentiation of distinct T cell populations.34 , 35 , 36 Using the gating strategy in Figure S5 (and summarized in Figure 6 A), we assessed the impact of i.n. 5-A-RU/MG administration on cell number and phenotype of these different DC populations. No significant changes in cell number or activation status were observed for the resident populations (Figures 6B, S6A, and S6B). In contrast, the frequency of migratory DCs was increased (with a non-significant upward trend in cell number) (Figure 6C), and activation markers CD80, CD86, and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PDL-1) were also upregulated (Figures 6D and S6C) and observed on both cDC1 and cDC2 subsets (Figure 6E). Importantly, no change in activation status of these DCs was seen when 5-A-RU/MG was administered to MR1−/− mice but was observed when administered to B6Aa0−/− mice (Figure 6F), highlighting the important MAIT cell interaction required.

Figure 6.

Intranasal administration of 5-A-RU/MG activates migratory dendritic cells

WT or MR1−/− mice were administered i.n. with PBS or 5-A-RU/MG. After 24 h, mLN were harvested for flow cytometry.

(A) Gating strategy to identify cDC subsets. Full gating strategy is detailed in Figure S5.

(B and C) Frequency and total numbers of resident cDCs (B) and migratory cDCs (C).

(D) Representative histograms and MFI of activation markers expressed by migratory cDCs.

(E) MFI of activation markers expressed by migratory cDC1 and migratory cDC2 subsets.

(F) WT or B6Aa0−/− mice were treated as above. Representative histograms and fold change of CD86 and PDL-1 MFI are expressed by migratory cDCs. Fold change is relative to the average of PBS-treated mice for each mouse strain.

Data are representative (A–E) or a combination (F) of n = 2 independent experiments, with n = 5–6 mice per group, per experiment. Graphs depicted as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (B–E) or unpaired t test (F), with ns, p ˃ 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001. See also Figure S6.

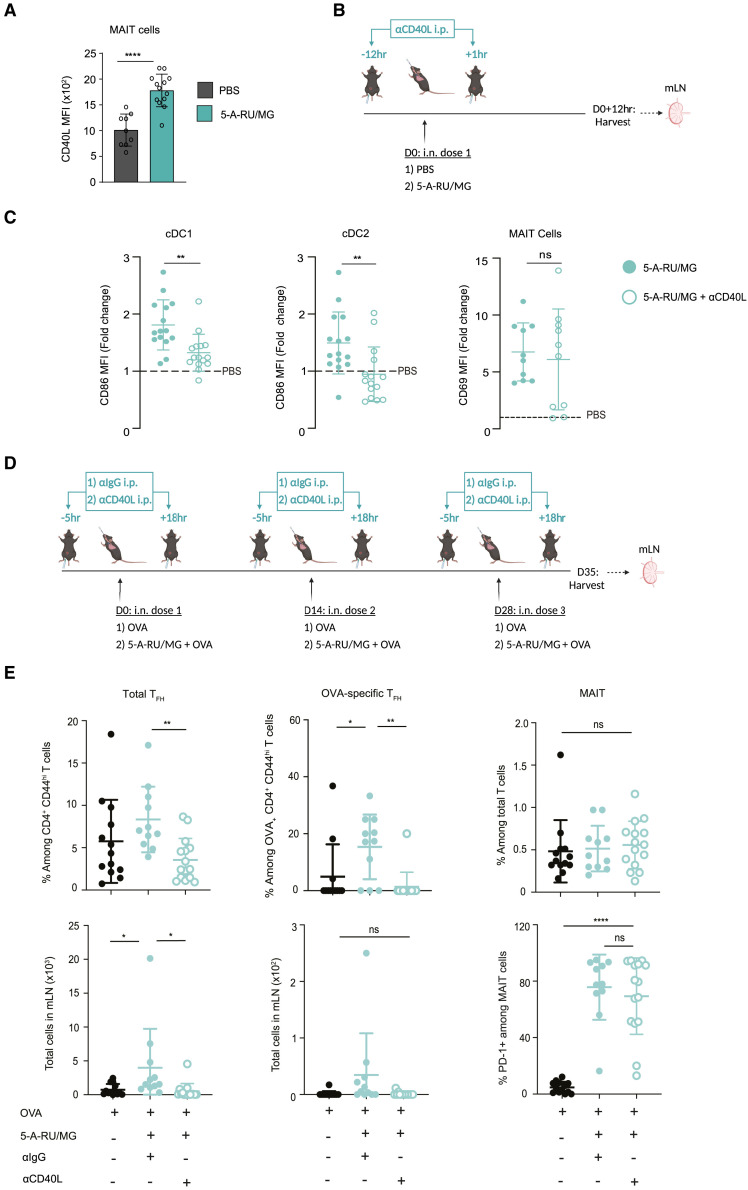

MAIT cell activation of cDCs is dependent on CD40-CD40L interaction

Signaling via CD40 is a well-known pathway of DC activation, resulting in increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules and release of proinflammatory cytokines, ultimately facilitating initiation of T cell immunity to acquired antigens.37 Moreover, CD40-CD40L ligation was shown to be essential for DC activation in vitro following incubation with CD40L-expressing human MAIT cells.16 It is therefore notable that we detected significant upregulation of CD40L on MAIT cells from the lung within 3 h after i.n. 5-A-RU/MG treatment compared with MAIT cells from PBS-treated mice (Figure 7 A). To determine whether CD40 ligation was necessary for MAIT-cell-dependent DC activation, we used an αCD40L monoclonal antibody (mAb) to prevent CD40-CD40L signaling during 5-A-RU/MG treatment and then assessed levels of MAIT cell activation and phenotype of migratory cDCs (Figure 7B). Blocking CD40 signaling did not affect MAIT cell activation, as indicated by CD69 upregulation (Figure 7C). In contrast, upregulation of the co-stimulatory molecule CD86 on migratory cDC1 and cDC2 subsets was inhibited when the blocking antibody was used (Figure 7C), suggesting that CD40L signaling is essential for MAIT cells to activate migratory cDCs.

Figure 7.

CD40L signaling is required for migratory cDC maturation and downstream induction of TFH after intranasal 5-A-RU/MG administration

(A) WT mice were treated i.n. with either PBS or 5-A-RU/MG. Three hours later, lungs were harvested for flow cytometry. MFI of CD40L expression by MAIT cells.

(B) Schematic of experimental design. Twelve hours prior and 1 h after i.n. treatment, mice were given 500 μg of αCD40L intraperitoneally (i.p.).

(C) Fold change MFI of CD86 on migratory cDC1 (B220− TCRβ− CD11c+ MHCIIhi SIRPα−) and cDC2 (B220− TCRβ− CD11c+ MHCIIhi SIRPα+ CD11b+). Fold change of CD69 MFI on MAIT cells (B220− TCRβ+ CD64− MR1-5-OP-RU+). Fold change is relative to the average of PBS-treated mice.

(D) Schematic of experimental design. WT mice were treated i.n. with either 5 nmol OVA alone or in combination with 5-A-RU/MG, three times spaced 2 weeks apart. Five hours prior and 18 h after i.n. treatment, mice were given 500 μg of αCD40L i.p.

(E) Frequency and total number of mLN TFH cells and OVA-specific TFH cells. MAIT cell frequency of total T cells and frequency of PD-1+ MAIT cells.

Graphs depicted as mean ± SD. Data represent a combination of n = 2 (A) or n = 3 (C and E) individual experiments, with n = 3–8 mice per group, per experiment. Unpaired t test (A and C) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (E) were performed, with ns, p ˃ 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001. See also Figure S7.

To establish whether CD40L-dependent activation of migratory cDCs by MAIT cells was important for TFH priming, CD4+ T cell responses were assessed following short-term αCD40L mAb blockade during treatment with 5-A-RU/MG + OVA. The antibody was administered 5 h before and 18 h after each of the three i.n. doses administered; a control group received an αIgG isotype control as outlined in Figure 7D. While blocking CD40 signaling did not alter MAIT cell activation, it did abolish the adjuvant effect of 5-A-RU/MG on TFH development, with antigen-specific TFH frequency and number reduced to levels seen with injection of OVA alone (Figure 7E). Agonists for MAIT cells therefore support humoral responses to mucosally administered antigens by activating migratory cDCs in a CD40-dependent fashion, leading to priming of conventional TFH cells.

Discussion

The results presented here show that activation of lung-associated MAIT cells by i.n. administration of MR1-binding agonists enhances humoral responses to co-administered antigens. This provides the first evidence that MAIT agonists alone (i.e., without the addition of TLR ligands) are capable of adjuvant activity, and importantly achieve this with minimal inflammation, a key consideration for the development of mucosal vaccines. This adjuvant activity involves CD40 signaling between activated MAIT cells and lung-associated migratory DCs promoting CD4+ TFH cell priming and the development of protein-specific antibody responses. Notably, i.n. administration of 5-A-RU/MG with RBD protein from SARS-CoV-2 promoted neutralizing antibody production in a pseudovirus neutralization assay and protected mice from lethal IAV challenge when co-delivered with HA protein, which was on a par with parenteral vaccination with a benchmark oil-in-water adjuvant.

DC licensing was a term first used to describe the action of CD4+ T cells to enhance DC activation, which in turn primed potent, long-lived CD8+ T cell responses.38 Initially, provision of CD40L to activate DCs was thought to be a function primarily reserved for CD4+ T cells.39 , 40 , 41 However, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that innate-like T cell populations including NKT cells,42 , 43 γ/δ T cells,44 and MAIT cells16 can also perform this role. Here we report evidence for MAIT-cell-dependent, CD40-mediated, DC activation in vivo. Like activated CD4+ T cells, we found that MAIT cells also express high levels of CD40L early after activation with 5-A-RU/MG treatment. Importantly, blocking CD40-CD40L interactions resulted in reduced expression of co-stimulatory molecules on DCs and complete ablation of TFH CD4+ differentiation, suggesting a non-redundant role for CD40 signaling in the cellular adjuvant activity of MAIT cells. In DCs, signaling induced by pattern recognition (or via some cytokine receptors) is required to activate canonical nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), which triggers alternative activation pathways such as the IFN response.45 In the absence of these activating signals, the CD40 signaling pathway initiates a separate signaling cascade to activate NF-κB2,46 which is typical of the non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway.47 The induction of MAIT-cell-mediated CD40 signaling in the absence of pattern recognition signals may explain the non-redundant role for CD40 signaling observed in this study.

The subset of DCs presenting antigen to naive CD4+ T cells has been implicated in the instruction of T-helper differentiation including TFH CD4+ differentiation.48 While both migratory cDCs and resident cDCs have been shown to be capable of priming CD4+ TFH cells, our data suggest that the migratory cDCs play a more dominant role after 5-A-RU/MG administration, indicated by the preferential upregulation of co-stimulatory receptors on this population. Thus, the interactions driving DC activation most likely took place in the lung where local MAIT cells are present and capable of interacting with 5-OP-RU-loaded DC patrolling the lung tissue.

Earlier in vitro studies had indicated that MAIT cells can support B cell responses through production of IL-21, leading to preferential production of IgG.18 , 49 Furthermore, cultures containing MAIT cells were also shown to exhibit enhanced memory B cell differentiation.50 In a mouse model of lupus, MAIT cells were shown to directly enhance autoantibody production, GC formation, and TFH cell responses in an MR1-dependent manner.49 While other innate-like T cells such as NKT cells can adopt a TFH phenotype and provide cognate help to B cells,28 , 29 , 51 , 52 , 53 we were unable to identify an MAITFH population in the mLNs after using 5-A-RU/MG as an adjuvant in our study. In addition, MAIT cells were unable to support B cell immunity in B6Aa0−/− mice, which lack conventional CD4+ TFH cells. This contrasts with studies using NKT agonists, where mice lacking conventional CD4+ TFH cells generate comparable antibody responses with WT mice.54 However, a population of MAITFH (CXCR5+) has been identified in vivo following i.n. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium challenge, but not after 5-A-RU/MG stimulation, which was in line with our observations.55 A role for such MAITFH in mice requires further investigation. While Bcl6fl/flCreCD4 mice that are deficient in CD4+ TFH cells have been widely used to assess the role and contribution of conventional TFH, these mice exhibit a deficiency in MAIT cells, which require Bcl6 for their development.56 Nevertheless, our data suggest that MAIT cells contribute to the humoral response through an indirect non-cognate role, involving activation of DCs to prime conventional CD4+ TFH cells. A similar non-cognate role has been described for NKT cells57 (in addition to generation of NKTFH).

While our study has focused on the “cellular adjuvant” properties of MAIT cells, previous research has demonstrated their potential as useful immune effectors in their own right. For example, prophylactic mucosal delivery of 5-OP-RU in mice has been shown to expand MAIT cell populations in the lung, leading to enhanced protection against subsequent pulmonary infection with Legionella 8 as well as improved control and clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis when 5-OP-RU is administered during infection.58 However, co-administration with a TLR agonist was found to be required for MAIT cells to differentiate into effector cells capable of producing IL-17 and IFN-γ.8 , 58 Moreover, intrinsic MR1 ligands present in various bacterial species can stimulate MR1-dependent responses to help B cells and promote production of bacterial-specific IgA and IgM in the mucosal tissue.55 , 59 , 60 In this context, MAIT cells were shown to provide cognate help to B cells,55 although they may also contribute to mounting a humoral response against bacteria in the mucosa in a non-cognate role, as presented here. Additionally, MAIT cell activation can contribute to antiviral responses,24 , 25 , 26 as we observed in mice pretreated with 5-A-RU/MG alone before IAV challenge. Activated MAIT cells can also express CTLA-4,61 suggesting that they may have a protective immunoregulatory role to limit immunopathology following viral infection. Thus, it is possible that immunization with 5-A-RU/MG and HA induces multiple mechanisms to protect mice from severe IAV infection. Importantly, by harnessing the cellular adjuvant activities of MAIT cells to generate virus-specific humoral immunity, we observed a significant improvement in virus clearance compared with protection afforded by MAIT cell activation alone. The duration of protection provided by MAIT cells and the resulting humoral response is yet to be determined. Notably, co-administration of 5-OP-RU and IL-23 prior to infection has been shown to improve immunity against bacterial mucosal challenge.15 , 62 In these studies, protection was observed up to 5 weeks after MAIT cell priming; subsequently, MAIT cells have also been shown to develop stable memory-like populations.62 Therefore, alternative approaches to exploit MAIT cell function for improving vaccine immunogenicity could be explored, such as priming MAIT cell populations prior to immunization.

As the MAIT cell/MR1 axis is also observed in humans, MR1-binding agonists potentially represent a new class of adjuvant to be used in vaccines to initiate humoral immunity in the respiratory mucosa. Compared with mice, humans have a higher frequency of MAIT cells,13 , 63 , 64 which could mean that any roles defined for MAIT cells in mouse models may be more pronounced in humans. However, recent studies have suggested that MAIT cell phenotype and function can differ between species, which may need to be considered when extending our observations to the clinic. For example, while treatment of chronically infected mice with 5-OP-RU (and TLR ligands) enhanced Mycobacterium tuberculosis clearance,58 this was not observed in non-human primates; in fact, treatment rendered these animals more susceptible to infection.65 Probing into the mechanism for this discrepancy revealed that, over time, MAIT cells in non-human primates expressed an exhausted phenotype, with high levels of inhibitory receptor PD-1 expression and reduced levels of IFN-γ, IL-17, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.65 Similarly, transcriptional analysis of MAIT cells isolated from human BAL samples showed that this population is composed of heterogeneous populations that include a subset of anti-inflammatory cells expressing a transcriptional profile associated with wound healing and genes encoding inhibitory receptors (i.e., T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 [TIM-3]).14 Furthermore, in vitro studies show that triggering of MAIT TCRs preferentially induces tissue-repair programs.66 Notably, similar tissue-repair programs have also been detected in mouse-derived MAIT cells.67 In the context of vaccine development, it is promising that activated human MAIT cells can activate DCs, as shown in in vitro studies.16 Recent studies have provided further evidence for the potential role of MAIT cells in vaccine-induced immunity. For example, studies have shown that MAIT cells from healthy donors are positively associated with the immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, including mRNA and viral vector formats.68 , 69 These studies suggest that MAIT cells could play a role in the establishment of adaptive immunity during vaccination in humans.

In summary, this work identifies a role for MAIT cells as a cellular adjuvant to promote activation of local DCs, which ultimately enhance humoral responses in the respiratory tract. The data presented here provide good rationale to explore whether MAIT cells or the factors provided by MAIT cells can be used in a clinical setting to aid in the development of mucosal vaccines.

Limitations of the study

The 5-A-RU/MG preparation method used in this study does not take into account potential by-products that may be produced that do not activate MAIT cells. In an attempt to counteract this, we employed MR1−/− and Nur77-GFP mice to demonstrate the involvement of MAIT cells and direct TCR stimulation following 5-A-RU/MG administration. In addition, the use of i.m. and s.c. delivered adjuvant comparisons in our viral studies aimed to provide positive control sera and a benchmark for our infection assays. However, because of the differing routes of administration, these control groups do not provide an exact comparison with the adjuvant power of i.n. delivered 5-A-RU/MG. Furthermore, we aimed to block CD40 signaling activity during early MAIT cell-DC interactions by restricting αCD40L mAb administration to the priming phase. Nonetheless, the involvement of CD40-CD40L signaling on processes downstream of DC activation cannot be ruled out, such as CD40-CD40L interaction between DCs and naive CD4+ T cells, which has been linked to TFH differentiation31 and direct T cell help to B cells.70 Finally, our experiments performed here in mice may not represent the capacity for MAIT cells in humans to drive protective humoral immunity.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-hm IgG | BioXCell | #BP0091 |

| Anti-ms B220 BUV395, RA3-6B2, 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:563793; RRID:AB_2738427 |

| Anti-ms Bcl6 AF647; K112-91; 1:50 | BD Biosciences | Cat:561525; RRID:AB_10898007 |

| Anti-ms CD4 BV785; GK1.5; 1:1600 | BioLegend | Cat:100453; RRID:AB_2565843 |

| Anti-ms CD11b BUV737; M1/70; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:564443; RRID:AB_2738811 |

| Anti-ms CD11c BV785; N418, 1:200 | BioLegend | Cat:117336; RRID:AB_2565268 |

| Anti-ms CD11c BV786; HL3; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:563735; RRID:AB_2738394 |

| Anti-ms CD25 BV510; PC61; 1:200 | BioLegend | Cat:102042; RRID:AB_2562270 |

| Anti-ms CD40 PE; 3/23; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:561846; RRID:AB_10896482 |

| Anti-ms CD40L PECy7; MR1; 1:50 | BioLegend | Cat:106512; RRID:AB_2563493 |

| Anti-ms CD40L; MR1 | BioXCell | #BP0017-1 |

| Anti-ms CD44 BUV737; IM7; 1:400 | BD Biosciences | Cat:564392; RRID:AB_2738785 |

| Anti-ms CD45.2 BV605; 104; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:563051; RRID:AB_2737974 |

| Anti-ms CD64 AF647; X54-5/7.1; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:558539; RRID:AB_647120 |

| Anti-ms CD64 PECy7; X54-5/7.1; 1:200 | BioLegend | Cat:139314; RRID:AB_2563904 |

| Anti-ms CD69 BV650; H1.2F3; 1:100 | BioLegend | Cat:104541; RRID:AB_2616934 |

| Anti-ms CD69 PE; H1.2F3; 1:100 | BD Biosciences | Cat:553237; RRID:AB_394726 |

| Anti-ms CD80 BV421; 16-10A1; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:562611; RRID:AB_2737675 |

| Anti-ms CD80 BV650; 16-10A1; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:563687; RRID:AB_2738376 |

| Anti-ms CD86 BUV395; GL-1; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:564199; RRID:AB_2738664 |

| Anti-ms CXCR5 Biotin; 2G8; 1:50 | BD Biosciences | Cat:551960; RRID:AB_394301 |

| Anti-ms FR4 BV650; 12A5; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:744122; RRID:AB_2742012 |

| Anti-ms GL7 FITC; GL7; 1:600 | BioLegend | Cat:144603; RRID_2561696 |

| Anti-ms ICOS APC; I5F9; 1:200 | BioLegend | Cat:107712; RRID:AB_2728129 |

| Anti-ms IgD APC H7; 11-26c.2a; 1:200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:565348; RRID:AB_2739201 |

| Anti-ms IgGTOTAL-HRP; G21040 | Life Technologies | Cat:G21040; RRID:AB_2536527 |

| Anti-ms IgG1-HRP; A10551 | Life Technologies | Cat:A10551; RRID:AB_2534048 |

| Anti-ms IgG2a/c-HRP; PA129288 | Life Technologies | Cat:PA129288; RRID:AB_10983148 |

| Anti-ms IgG2b-HRP; M32407 | Life Technologies | Cat:M32407; RRID:AB_2536647 |

| Anti-ms IgG3-HRP; M32707 | Life Technologies | Cat:M32707; RRID:AB_2536652 |

| Anti-ms Ki67 AF594; 11F6; 1:400 | BioLegend | Cat:151214; RRID:AB_2721389 |

| Anti-ms MHCIII-A/I-E AF488; 3JP 1:200 | Lab of Prof. Franca Ronchese | N/A |

| Anti-ms MHCII I-A/I-E FITC; M5/114.15.2; 1:200 | eBioscience | Cat:11532182; RRID:AB_465232 |

| Anti-ms PD-1 PeCy7; 29F.1A12; 1:400 | BioLegend | Cat:135216; RRID:AB_10689635 |

| Anti-ms PDL-1 BV711; MIH5; 1:800 | BD Biosciences | Cat:563369; RRID:AB_2738163 |

| Anti-ms SIRP1a Biotin; P84; 1:500 | BioLegend | Cat:144026; RRID:AB_2721320 |

| Anti-ms TCRb BV605; H57-597; 1:400 | BioLegend | Cat:109241; RRID:AB_2629563 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| A/X-31 (A/HK/8/68) | ATCC | #VR-1679 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| 5-A-RU | Lab of Prof. Gavin Painter | N/A |

| MG | Sigma-Aldrich | #M0252 |

| Endo Grade® OVA protein | Lionex Diagnostics and Therapeutics | #LET0027 |

| HA (A/X-31) protein | Lab of A/Prof. Davide Comoletti | N/A |

| RBD (Dimerised; Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 Spike) protein | Lab of A/Prof. Davide Comoletti | N/A |

| AddaVax | Jomar Bioscience | #vac-adx-10 |

| DNase I | Sigma-Aldrich | #10104159001 |

| Liberase | Sigma-Aldrich | #54010200001 |

| Zombie NIR | BioLegend | #423105 |

| Zombie Aqua | BioLegend | #423102 |

| Fixable Viability Stain 700 | BD Biosciences | #564997 |

| SAV PECF594; 1:1200 | BD Biosciences | Cat:562284; RRID:AB_11154598 |

| Anti-ms MR1-5OPRU PE, 1:200 | NIH Tetramer Core Facility | N/A |

| Anti-ms I-A(b)AAHAEINEA, PE, 1:50 | NIH Tetramer Core Facility | N/A |

| Anti-ms I-A(b)HAAHAEINEA, PE, 1:50 | NIH Tetramer Core Facility | N/A |

| OVA-biotin | Lab of Dr. Lisa Connor | N/A |

| S.mansoni infected sera | Lab of Prof. Anne La Flamme | N/A |

| IMDM | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #31980097 |

| PBS | Life Technologies | #14190250 |

| 10% PBS Tween | Sigma-Aldrich | #P1379 |

| TMB | BD Biosciences | #555214 |

| 2M H2SO4 | Lab of Dr. Lisa Connor | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| FOXP3 Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #00552300 |

| Mouse IgE ELISA kit | BD Biosciences | #555248 |

| Mouse IgA ELISA kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | #885045022 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HEK293S GnTI- | ATCC | CRL-3022 |

| HEK293/ACE2 | Lab of Prof. Miguel Quiñones-Mateu | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6 | The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME | JAX strain number: 000664 |

| Mouse: MR1−/− | Lab of Prof. Vincenzo Cerundolo | N/A |

| Mouse: Nur77-GFP (common name) C57BL/6-Tg(Nr4a1-EGFP/cre)820Khog/J | The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME | JAX strain number: 016617 |

| Mouse: B6Aa0−/− | Biological Research Laboratories Ltd, Wolferstrasse, Switzerland | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo Version 9.6.2 | Tree Star | N/A |

| GraphPad Prism Version 8 | GraphPad, CS,USA | N/A |

| Biorender | Biorender.com | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents may be directed to the corresponding author, Dr. Lisa Connor (lisa.connor@vuw.ac.nz).

Materials availability

No new materials or reagents were generated by this study.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

Mice were bred and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Victoria University of Wellington Small Animal Facility and Malaghan Institute of Medical Research Biomedical Research Unit (Wellington, New Zealand). C57BL/6 (designated WT) mice were originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MR1−/− mice that lack the α1 and α2 domains of the gene encoding MR1, were kindly provided by the late Professor Vincenzo Cerundolo (Weatherall Institute, Oxford, UK). Nur77-GFP transgenic mice exhibit GFP expression under control of Nr4al region within the BAC transgene, consistent with endogenous Nur77 and antigen-receptor stimulation. Nur77-GFP mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). B6Aa0−/− mice were created on a C57BL/6 background by targeting a mutation to the Aa gene encoding MHCII, provided by the Biological Research Laboratories Ltd (Wolferstrasse, Switzerland). Sex-matched male and female mice aged on average 8 to 12 weeks were used in experiments, after approval by the Victoria University of Wellington Animal Ethics Committee. Animals were group housed, and littermates within the same cage were randomly allocated to receive stimuli or control.

Method details

Synthesis of 5-A-RU

Sodium dithionite (nominally 86% by redox titration, 84.0 mg, nominally 6.0 equiv) was added to a suspension of 5-nitroso-6-(D-ribitylamino)uracil (20.4 mg, 0.069 mmol) in sterile water (1.5 mL, Sigma-Aldrich). The mixture was briefly sonicated until the nitrosouracil dissolved and a colourless solution was obtained.71

Preparation of HA and RBD proteins

HEK293S GnTI- cells (ATCC) were transfected using polyethylenimine with the cDNA encoding for influenza A (A/X-31) HA ectodomain, or a tandem dimer of the RBD fused to the Fc region of human IgG as well as an empty vector plasmid (pcDNA3.1) conferring G418 resistance. After 48 hours, cells were selected in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 500 μg/mL G418. Resistant clones were isolated using Pyrex cloning rings (Corning) and levels of expression of the Fc-HA or Fc-RBD proteins were tested via western blot. Best expressing clones were used for large-scale protein production, which was performed in cell culture flasks (Nunc™ TripleFlaskTM) with regular collection and replenishment of cell culture medium, containing 2-5% FBS. Secreted proteins were purified by affinity chromatography, using CaptivA™ PriMAB rProtein A Affinity Resin (Repligen). Resin was washed (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 450 mM NaCl), equilibrated (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM DTT) and the Fc portion was removed from the final product by HRV-3C protease (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 10μg/mL HRV-3C protease) overnight. Purified protein was buffer exchanged into PBS and concentrated using a Vivaspin concentrator (Sartorius-Stedim) to 3-5 mg/mL and flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C.

Immunisations

Intranasal procedures were performed in 30 μL volumes on ketamine/xylazine sedated mice. For single-dose assays, mice received either PBS or 5-A-RU/MG (MG; Sigma-Aldrich). For OVA-specific prime-boost assays, mice received either 5 nmol Endo Grade® Ovalbumin protein (Sigma-Aldrich) alone, or mixed with 5-A-RU/MG (75 nmol 5-A-RU mixed with 750 nmol MG). Three homologous immunisations were performed at two-week intervals. For HA-specific and RBD-specific prime-boost assays, mice received either PBS, 5-A-RU/MG alone, 10 μg of IAV HA (A/X-31) protein alone, 50 μg of SARS-CoV-2 RBD (dimerised, ancestral virus) protein alone, or protein mixed with 5-A-RU/MG. As a benchmark, proteins were mixed with AddaVax (InvivoGen) at 1:1 v/v and delivered either subcutaneously into the right and left flanks (HA vaccination) or intramuscularly into the left and right legs (RBD vaccination) in 50 μL volumes according to the same prime-boost regimen as above.

Tissue preparation and flow cytometry

For DC preparation, mLNs were collected and digested with DNase I and Liberase TL (Sigma-Aldrich) in IMDM for 25 min at 37°C. For lung preparation, lungs were perfused prior to collection and finely chopped before digestion with DNase I and Liberase TL for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer and washed in preparation for staining. Single cell suspensions were stained for viability with Zombie NIR/Aqua™ (BioLegend) or BD Horizon™ Fixable Viability Stain 700 (BD Biosciences), before incubation with anti-mouse CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2), to block any non-specific antibody binding. For labelling OVA-specific TFH cells, prior to surface staining, cells were incubated with two MHCII-OVA tetramers (containing I-A(b)HAAHAEINEA and I-A(b)AAHAEINEA epitopes both labelled with PE; NIH Tetramer Core Facility) for 30 min at RT. For labelling OVA-specific B cells, cells were incubated with biotinylated OVA protein (Lab of Dr. Lisa Connor) for 30 min at 4°C, followed by a 15 min incubation at 4°C with streptavidin. Cells were stained in a separate step for chemokine receptor CXCR5 (2G8) at 37°C for 30 min. For staining of surface molecules, cells were incubated with cocktails of fluorescent antibodies specific for: CD11c (N418, HL3), MHCII (I-A/I-E M5/114.15.2, 3JP), CD86 (GL-1), CD80 (16-10A1), CD64 (X54-5/7.1), CD11b (M1/70), SIRP1α (P84), PDL-1 (MIH5), CD69 (H1.2F3), B220 (RA3-6B2), TCRβ (H57-597), CD4 (GK1.5), CD44 (IM7), ICOS (15F9), FR4 (12A5), CD25 (PC61), CD40 (3/23), PD-1 (29F.1A12), GL7 (GL7), IgD (11-26c.2a), CD40L (MR1), CD45.2 (104), and MR1-5OPRU tetramer (NIH Tetramer Core). For intranuclear transcription factor staining, cells were fixed and permeabilised using the FOXP3 Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (Life Technologies), before staining with Bcl6 (K112-91), or Ki67 (11F6). Data were acquired on a LSRFortessa Flow Cytometer (BD) or Cytek™ Aurora (Cytek Biosciences) and analysed using FlowJo version 9.6.2 (Tree Star).

Detection of serum IgG by ELISA

For detection of antigen-specific serum IgG, microtitre plates (Maxisorp, Nunc) were incubated overnight with either 20 μg/mL Endo Grade® Ovalbumin protein (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg/mL HA protein, or 2 μg/mL RBD protein in bicarbonate buffer. 10% FBS was applied to prevent non-specific binding, prior to application of serially diluted serum samples. A final incubation was performed with a variety of Ig isotypes; IgGTOTAL (G21040), IgG1 (A10551), IgG2a/c (PA129288), IgG2b (M32407), IgG3 (M32707) conjugated to HRP (Life Technologies). Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB; BD Biosciences) and 2M H2SO4 (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to develop and stop reactions, before immediately being read at 450 nm. Wash steps were performed 5x between each incubation with 10% PBS-Tween (Sigma-Aldrich).

Detection of serum IgE by ELISA

Serum IgE antibodies were measured using a mouse IgE ELISA kit (BD Biosciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Serum from S.mansoni infected mice (Lab of Prof. Anne La Flamme) was used as a positive control.

Detection of BALF IgA by ELISA

BALF was collected by inserting a catheter into the trachea. 0.6 mL of 10% FCS PBS was injected and aspirated three times. Approximately 0.5 mL of BALF was recovered from each mouse and supernatant was collected following centrifugation. Aliquots of BALF were stored under -80°C. IgA antibodies in the BALF were measured using a mouse Total IgA ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions with the exception of the coating antigen. For detection of antigen-specific IgA, microtitre plates (Maxisorp, Nunc) were incubated overnight with either 20 μg/mL Endo Grade® Ovalbumin protein (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg/mL HA protein or 2 μg/mL RBD protein in bicarbonate buffer.

Pseudotyped virus neutralisation assay

The ability for mouse serum or BAL samples to neutralise SARS-CoV-2 spike-mediated entry was determined as described by Crawford et al.72 Briefly, HEK293/ACE-2 cells (Lab of Prof. Miguel Quiñones-Mateu) were seeded in poly-D-lysine coated, white-walled, 96-well plates (20,000 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Samples collected from immunised mice were heat-treated at 56°C for 30 min, diluted with cell culture medium (1:10, then 1:5 serial dilutions), mixed with a suspension of the SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped lentiviral particles (enough to generate >1,000-fold signal over background, approximately 3 to 4 x 105 relative light units [RLU]/well) in 96-well plates at a 1:1 ratio (150 μl final volume) and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for one hour. The cell culture media of the HEK293/ACE-2 cells was removed, replaced with the mixture of serially diluted serum with SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped lentiviruses, plus 5 μg/ml of polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich Merck), and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 72 hours. Viral entry was quantified by removing the cell culture supernatant and adding a 1:1 mixture of fresh cell culture media (50 μl) and luciferin reagent (50 μl, Steady-Luc Firefly assay kit, Biotium) to each well. Plates were incubated at room temperature with gentle shaking (300 rpm) for 5 min and luminescence measured using a plate reader (VICTOR Nivo, PerkinElmer). Neutralising antibody titres were calculated by a non-linear regression model (log inhibitor vs. normalised response-variable slope) analysis and expressed as 50% neutralising titre (NT50).

Influenza challenge

Three weeks after the final third boost immunisation, ketamine/xylazine sedated mice were challenged with a 50 μL injection containing LD50 2 HAU A/X-31 (A/HK/8/68; ATCC). Mice were weighed daily for two weeks post-infection. Mice that lost more than 70% of initial body weight were euthanised.

αCD40L monoclonal antibody blockade

Mice were administered 250-500 μg of anti-mouse CD40L (CD154) (clone MR-1; BioXCell) intraperitoneally as indicated in the relevant figure legends. Control mice received 250-500 μg of Armenian Hamster IgG (BioXCell).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (Version 8, GraphPad, CS, USA). Data are represented as mean ± SD. Value of n represents number of animals used or number of individual experiments performed, as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analysis of p<0.05 was considered significant, determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, log-rank (Mantel-cox) test, one and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, as specified in the relevant figure legends.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research Biomedical Research Unit and the Victoria University of Wellington Small Animal Facility for the provision and husbandry of mice. We thank the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research Hugh Green Cytometry Centre for maintenance of flow cytometers. We thank the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (contract no. 75N93020D00005) for providing MR1-5-OP-RU and MHCII-OVA tetramers. We thank Prof. Franca Ronchese for the expert opinion provided on this study as well as Dr. Olivia Burn, Dr. Alissa Cait, and Dr. David O’Sullivan for reviewing our manuscript. This research was funded by a Health Research Council of New Zealand project grant to L.M.C. (grant no. 21/565), Malaghan Institute of Medical Research New Zealand, and Research for Life New Zealand. T.E.P. was supported by a Victoria University of Wellington Doctoral Research Scholarship. K.H.B. was supported by a Victoria University of Wellington Masters by Thesis Scholarship. I.F.H. was supported by the Thompson Family Foundation and Hugh Dudley Morgans Fellowship. L.M.C. was supported by a Sir Charles Hercus Health Research Fellowship (grant no. 18/114) from the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Author contributions

T.E.P., K.H.B., J.L.L., K.R.B., K.J.F., O.R.P., I.M., N.C.M., and J.K. performed experiments. A.J.M., T.W.B., B.J.C., D.C., M.S., M.E.Q.-M., G.F.P., I.F.H., and L.M.C. provided vital materials and expertise. T.E.P., K.H.B., I.F.H., and L.M.C. designed and analyzed experiments, coordinated the study, and wrote the paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Published: March 28, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112310.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

No new code was generated during this study. All data are available upon reasonable request directed to the lead contact. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Li M., Wang Y., Sun Y., Cui H., Zhu S.J., Qiu H.J. Mucosal vaccines: strategies and challenges. Immunol. Lett. 2020;217:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corthésy B. Multi-faceted functions of secretory IgA at mucosal surfaces. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:185. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter N.J., Curran M.P. Live attenuated influenza vaccine (FluMist®; FluenzTM): a review of its use in the prevention of seasonal influenza in children and adults. Drugs. 2011;71:1591–1622. doi: 10.2165/11206860-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindsey B.B., Jagne Y.J., Armitage E.P., Singanayagam A., Sallah H.J., Drammeh S., Senghore E., Mohammed N.I., Jeffries D., Höschler K., et al. Effect of a Russian-backbone live-attenuated influenza vaccine with an updated pandemic H1N1 strain on shedding and immunogenicity among children in the Gambia: an open-label, observational, phase 4 study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019;7:665–676. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calzas C., Chevalier C. Innovative mucosal vaccine formulations against influenza a virus infections. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1605. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treiner E., Duban L., Bahram S., Radosavljevic M., Wanner V., Tilloy F., Affaticati P., Gilfillan S., Lantz O. Selection of evolutionarily conserved mucosal-associated invariant T cells by MR1. Nature. 2003;422:164–169. doi: 10.1038/nature01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahimpour A., Koay H.F., Enders A., Clanchy R., Eckle S.B.G., Meehan B., Chen Z., Whittle B., Liu L., Fairlie D.P., et al. Identification of phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous mouse mucosal-associated invariant T cells using MR1 tetramers. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:1095–1108. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H., D’Souza C., Lim X.Y., Kostenko L., Pediongco T.J., Eckle S.B.G., Meehan B.S., Shi M., Wang N., Li S., et al. MAIT cells protect against pulmonary Legionella longbeachae infection. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3350. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corbett A.J., Eckle S.B.G., Birkinshaw R.W., Liu L., Patel O., Mahony J., Chen Z., Reantragoon R., Meehan B., Cao H., et al. T-cell activation by transitory neo-antigens derived from distinct microbial pathways. Nature. 2014;509:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kjer-Nielsen L., Patel O., Corbett A.J., Le Nours J., Meehan B., Liu L., Bhati M., Chen Z., Kostenko L., Reantragoon R., et al. MR1 presents microbial vitamin B metabolites to MAIT cells. Nature. 2012;491:717–723. doi: 10.1038/nature11605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel O., Kjer-Nielsen L., Le Nours J., Eckle S.B.G., Birkinshaw R., Beddoe T., Corbett A.J., Liu L., Miles J.J., Meehan B., et al. Recognition of vitamin B metabolites by mucosal-associated invariant T cells. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2142. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meierovics A., Yankelevich W.J.C., Cowley S.C. MAIT cells are critical for optimal mucosal immune responses during in vivo pulmonary bacterial infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E3119–E3128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302799110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z., Wang H., D’Souza C., Sun S., Kostenko L., Eckle S.B.G., Meehan B.S., Jackson D.C., Strugnell R.A., Cao H., et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T-cell activation and accumulation after in vivo infection depends on microbial riboflavin synthesis and co-stimulatory signals. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:58–68. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinks T.S.C., Marchi E., Jabeen M., Olshansky M., Kurioka A., Pediongco T.J., Meehan B.S., Kostenko L., Turner S.J., Corbett A.J., et al. Activation and in vivo evolution of the MAIT cell transcriptome in mice and humans reveals tissue repair functionality. Cell Rep. 2019;28:3249–3262.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H., Kjer-Nielsen L., Shi M., D’Souza C., Pediongco T.J., Cao H., Kostenko L., Lim X.Y., Eckle S.B.G., Meehan B.S., et al. IL-23 costimulates antigen-specific MAIT cell activation and enables vaccination against bacterial infection. Sci. Immunol. 2019;4:eaaw0402. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salio M., Gasser O., Gonzalez-lopez C., Martens A., Veerapen N., Gileadi U., Verter J.G., Napolitani G., Anderson R., Painter G., et al. Activation of human mucosal-associated invariant T cells induces CD40L-dependent maturation of monocyte-derived and primary dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2017;199:2631–2638. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crotty S. T follicular helper cell biology: a decade of discovery and diseases. Immunity. 2019;50:1132–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett M.S., Trivedi S., Iyer A.S., Hale J.S., Leung D.T. Human mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells possess capacity for B cell help. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017;102:1261–1269. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A0317-116R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macpherson A.J., McCoy K.D., Johansen F.-E., Brandtzaeg P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:11–22. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Flores D., Zepeda-Cervantes J., Cruz-Reséndiz A., Aguirre-Sampieri S., Sampieri A., Vaca L. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines based on the spike glycoprotein and implications of new viral variants. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:701501. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.701501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell R.J., Kerry P.S., Stevens D.J., Steinhauer D.A., Martin S.R., Gamblin S.J., Skehel J.J. Structure of influenza hemagglutinin in complex with an inhibitor of membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17736–17741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807142105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onodera T., Takahashi Y., Yokoi Y., Ato M., Kodama Y., Hachimura S., Kurosaki T., Kobayashi K. Memory B cells in the lung participate in protective humoral immune responses to pulmonary influenza virus reinfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:2485–2490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115369109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Wilgenburg B., Loh L., Chen Z., Pediongco T.J., Wang H., Shi M., Zhao Z., Koutsakos M., Nüssing S., Sant S., et al. MAIT cells contribute to protection against lethal influenza infection in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4706. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Wilgenburg B., Scherwitzl I., Hutchinson E.C., Leng T., Kurioka A., Kulicke C., De Lara C., Cole S., Vasanawathana S., Limpitikul W., et al. MAIT cells are activated during human viral infections. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11653. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ussher J.E., Bilton M., Attwod E., Shadwell J., Richardson R., de Lara C., Mettke E., Kurioka A., Hansen T.H., Klenerman P., Willberg C.B. CD161++ CD8+ T cells, including the MAIT cell subset, are specifically activated by IL-12+IL-18 in a TCR-independent manner. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:195–203. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran A.E., Holzapfel K.L., Xing Y., Cunningham N.R., Maltzman J.S., Punt J., Hogquist K.A. T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1279–1289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang P.P., Barral P., Fitch J., Pratama A., Ma C.S., Kallies A., Hogan J.J., Cerundolo V., Tangye S.G., Bittman R., et al. Identification of Bcl-6-dependent follicular helper NKT cells that provide cognate help for B cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 2011;13:35–43. doi: 10.1038/ni.2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King I.L., Fortier A., Tighe M., Dibble J., Watts G.F.M., Veerapen N., Haberman A.M., Besra G.S., Mohrs M., Brenner M.B., Leadbetter E.A. Invariant natural killer T cells direct B cell responses to cognate lipid antigen in an IL-21-dependent manner. Nat. Immunol. 2011;13:44–50. doi: 10.1038/ni.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennock N.D., White J.T., Cross E.W., Cheney E.E., Tamburini B.A., Kedl R.M. T cell responses: naïve to memory and everything in between. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2013;37:273–283. doi: 10.1152/advan.00066.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnaswamy J.K., Alsén S., Yrlid U., Eisenbarth S.C., Williams A. Determination of T Follicular helper cell fate by dendritic cells. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2169. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnaswamy J.K., Gowthaman U., Zhang B., Mattsson J., Szeponik L., Liu D., Wu R., White T., Calabro S., Xu L., et al. Migratory CD11b + conventional dendritic cells induce T follicular helper cell-dependent antibody responses. Sci. Immunol. 2017;2:eaam9169. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aam9169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouteau A., Kervevan J., Su Q., Zurawski S.M., Contreras V., Dereuddre-Bosquet N., Le Grand R., Zurawski G., Cardinaud S., Levy Y., Igyártó B.Z. DC subsets regulate humoral immune responses by supporting the differentiation of distinct TFH cells. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1134. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pooley J.L., Heath W.R., Shortman K. Cutting edge: intravenous soluble antigen is presented to CD4 T cells by CD8− dendritic cells, but cross-presented to CD8 T cells by CD8+ dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2001;166:5327–5330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hildner K., Edelson B.T., Purtha W.E., Diamond M., Matsushita H., Kohyama M., Calderon B., Schraml B.U., Unanue E.R., Diamond M.S., et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8α+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durai V., Murphy K.M. Functions of murine dendritic cells. Immunity. 2016;45:719–736. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cella M., Scheidegger D., Palmer-Lehmann K., Lane P., Lanzavecchia A., Alber G. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of interleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T-T help via APC activation. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:747–752. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanzavecchia A. Immunology. Licence to kill. Nature. 1998;393:413–414. doi: 10.1038/30845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett S.R., Carbone F.R., Karamalis F., Miller J.F., Heath W.R. Induction of a CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte response by cross-priming requires cognate CD4+ T cell help. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:65–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridge J.P., Di Rosa F., Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoenberger S.P., Toes R.E., van der Voort E.I., Offringa R., Melief C.J. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40–CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–483. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishimura T., Kitamura H., Iwakabe K., Yahata T., Ohta A., Sato M., Takeda K., Okumura K., Van Kaer L., Kawano T., et al. The interface between innate and acquired immunity: glycolipid antigen presentation by CD1d-expressing dendritic cells to NKT cells induces the differentiation of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 2000;12:987–994. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hermans I.F., Silk J.D., Gileadi U., Salio M., Mathew B., Ritter G., Schmidt R., Harris A.L., Old L., Cerundolo V. NKT cells enhance CD4 + and CD8 + T cell responses to soluble antigen in vivo through direct interaction with dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5140–5147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inoue S.I., Niikura M., Takeo S., Mineo S., Kawakami Y., Uchida A., Kamiya S., Kobayashi F. Enhancement of dendritic cell activation via CD40 ligand-expressing γδ T cells is responsible for protective immunity to Plasmodium parasites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:12129–12134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204480109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerkmann M., Rothenfusser S., Hornung V., Towarowski A., Wagner M., Sarris A., Giese T., Endres S., Hartmann G. Activation with CpG-A and CpG-B oligonucleotides reveals two distinct regulatory pathways of type I IFN synthesis in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4465–4474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lind E.F., Ahonen C.L., Wasiuk A., Kosaka Y., Becher B., Bennett K.A., Noelle R.J. Dendritic cells require the NF-kappaB2 pathway for cross-presentation of soluble antigens. J. Immunol. 2008;181:354–363. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi T., Walsh P.T., Walsh M.C., Speirs K.M., Chiffoleau E., King C.G., Hancock W.W., Caamano J.H., Hunter C.A., Scott P., et al. TRAF6 is a critical factor for dendritic cell maturation and development. Immunity. 2003;19:353–363. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hilligan K.L., Ronchese F. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells and their instruction of CD4+ T helper cell responses. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020;17:587–599. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0465-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murayama G., Chiba A., Suzuki H., Nomura A., Mizuno T., Kuga T., Nakamura S., Amano H., Hirose S., Yamaji K., et al. A critical role for mucosal-associated invariant T cells as regulators and therapeutic targets in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2681. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahman M.A., Ko E.J., Bhuyan F., Enyindah-Asonye G., Hunegnaw R., Helmold Hait S., Hogge C.J., Venzon D.J., Hoang T., Robert-Guroff M. Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells provide B-cell help in vaccinated and subsequently SIV-infected Rhesus Macaques. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:10060. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66964-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galli G., Pittoni P., Tonti E., Malzone C., Uematsu Y., Tortoli M., Maione D., Volpini G., Finco O., Nuti S., et al. Invariant NKT cells sustain specific B cell responses and memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3984–3989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leadbetter E.A., Brigl M., Illarionov P., Cohen N., Luteran M.C., Pillai S., Besra G.S., Brenner M.B. NK T cells provide lipid antigen-specific cognate help for B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8339–8344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801375105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barral P., Eckl-Dorna J., Harwood N.E., De Santo C., Salio M., Illarionov P., Besra G.S., Cerundolo V., Batista F.D. B cell receptor-mediated uptake of CD1d-restricted antigen augments antibody responses by recruiting invariant NKT cell help in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8345–8350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802968105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tonti E., Fedeli M., Napolitano A., Iannacone M., von Andrian U.H., Guidotti L.G., Abrignani S., Casorati G., Dellabona P. Follicular helper NKT cells induce limited B cell responses and germinal center formation in the absence of CD4 + T cell help. J. Immunol. 2012;188:3217–3222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jensen O., Trivedi S., Meier J.D., Fairfax K.C., Hale J.S., Leung D.T. A subset of follicular helper-like MAIT cells can provide B cell help and support antibody production in the mucosa. Sci. Immunol. 2022;7:eabe8931. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]