Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based computer-aided detection and diagnosis (CAD) is an important research area in radiology. However, only two narrative reviews about general uses of AI in pediatric radiology and AI-based CAD in pediatric chest imaging have been published yet. The purpose of this systematic review is to investigate the AI-based CAD applications in pediatric radiology, their diagnostic performances and methods for their performance evaluation. A literature search with the use of electronic databases was conducted on 11 January 2023. Twenty-three articles that met the selection criteria were included. This review shows that the AI-based CAD could be applied in pediatric brain, respiratory, musculoskeletal, urologic and cardiac imaging, and especially for pneumonia detection. Most of the studies (93.3%, 14/15; 77.8%, 14/18; 73.3%, 11/15; 80.0%, 8/10; 66.6%, 2/3; 84.2%, 16/19; 80.0%, 8/10) reported model performances of at least 0.83 (area under receiver operating characteristic curve), 0.84 (sensitivity), 0.80 (specificity), 0.89 (positive predictive value), 0.63 (negative predictive value), 0.87 (accuracy), and 0.82 (F1 score), respectively. However, a range of methodological weaknesses (especially a lack of model external validation) are found in the included studies. In the future, more AI-based CAD studies in pediatric radiology with robust methodology should be conducted for convincing clinical centers to adopt CAD and realizing its benefits in a wider context.

Keywords: children, confusion matrix, convolutional neural network, deep learning, diagnostic accuracy, disease identification, image interpretation, machine learning, medical imaging, pneumonia

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an active research area in radiology [1,2,3,4]. However, the investigation of use of AI for computer-aided detection and diagnosis (CAD) in radiology started in 1955. Any CAD systems are AI applications and can be subdivided into two types: computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) [5,6,7]. The former focuses on the automatic detection of anomalies (e.g., tumor, etc.) on medical images, while the latter is capable of automatically characterizing anomaly types such as benign and malignant [7]. Since the 1980s, more researchers have become interested in the CAD system development due to availabilities of digital medical imaging and powerful computers. The first CAD system approved by The United States of America Food and Drug Administration was commercially available in 1998 for breast cancer detection [6].

Early AI-based CAD systems in radiology were entirely rule based, and their algorithms could not improve automatically. In contrast, machine learning (ML)-based and deep learning (DL)-based CAD systems can automatically improve their performances through training, and hence, they have become dominant. DL is a subset of ML, and its models have more layers than those of ML. The DL algorithms are capable of modeling high-level abstractions in medical images without predetermined inputs [5,8,9].

A recent systematic review has shown that the DL-based CAD systems in radiology have been developed for a range of areas including breast, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hepatological, neurological, respiratory, rheumatic, thyroid and urologic diseases, and trauma. The performances of these CAD systems matched expert readers’ capabilities (pooled sensitivity and specificity: 87.0% vs. 86.4% and 92.5% vs. 90.5%), respectively [10]. Apparently, the current AI-based CAD systems might help to address radiologist shortage problems [9,10,11]. Nevertheless, various systematic reviews have criticized that the diagnostic performance figures reported in many AI-based CAD studies were not trustworthy because of their methodological weaknesses [10,12,13].

Pediatric radiology is a subset of radiology [14,15,16,17]. The aforementioned systematic review findings may not be applicable to the pediatric radiology [10,12,13,16,17]. For example, the AI-based CAD systems for breast and prostate cancer detections seem not relevant to children [10,12,13,17]. Although the AI-based CAD is an important topic area in radiology [10,12,13], apparently, only two narrative reviews about various uses of AI in pediatric radiology (e.g., examination booking, image acquisition and post-processing, CAD, etc.) [17] and AI-based CAD in pediatric chest imaging have been published to date [16]. Hence, it is timely to conduct a systematic review about the diagnostic performance of AI-based CAD in pediatric radiology. The purpose of this article is to systematically review the original studies to answer the question: “What are the AI-based CAD applications in pediatric radiology, their diagnostic performances and methods for their performance evaluation?”

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review of the diagnostic performance of the AI-based CAD in pediatric radiology was conducted as per the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and patient/population, intervention, comparison, and outcome model. This involved a literature search, article selection, and data extraction and synthesis [10,12,13,14,18].

2.1. Literature Search

The literature search with the use of electronic scholarly publication databases, including EBSCOhost/Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature Ultimate, Ovid/Embase, PubMed/Medline, ScienceDirect, Scopus, SpringerLink, Web of Science, and Wiley Online Library was conducted on 11 January 2023 to identify articles investigating the diagnostic performance of the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology with no publication year restriction [12,19,20]. The search statement used was (“Artificial Intelligence” OR “Machine Learning” OR “Deep Learning”) AND (“Computer-Aided Diagnosis” OR “Computer-Aided Detection”) AND (“Pediatric” OR “Children”) AND (“Radiology” OR “Medical Imaging”). The keywords used in the search were based on the review focus and systematic reviews on the diagnostic performance of the AI-based CAD in radiology [19,20,21,22,23].

2.2. Article Selection

A reviewer with more than 20 years of experience in conducting literature reviews was involved in the article selection process [14,24]. Only peer-reviewed original research articles that were written in English and focused on the AI-based CAD in pediatric radiology with the diagnostic accuracy measures were included. Gray literature, conference proceedings, editorials, review, perspective, opinion, commentary, and non-peer-reviewed (e.g., those published via the arXiv research-sharing platform, etc.) articles were excluded because this systematic review focused on the diagnostic performance of the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology and appraisal of the associated methodology reported in the refereed original articles. Papers mainly about image segmentation or clinical prediction instead of disease identification or classification were also excluded [12].

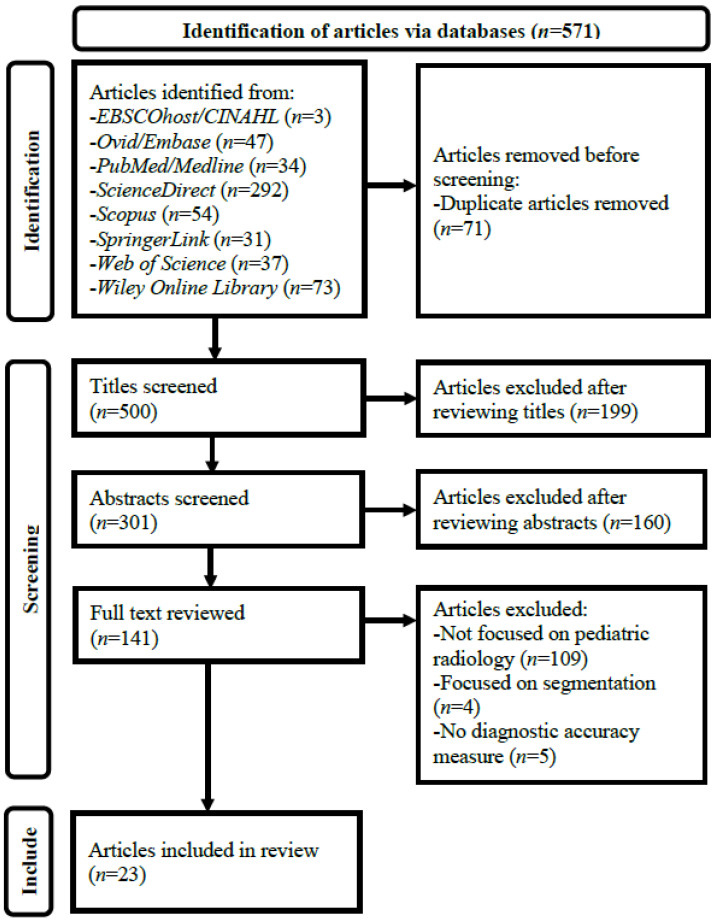

Figure 1 illustrates the details of the article selection process. A three-stage screening process through assessing (1) article titles, (2) abstracts, and (3) full texts against the selection criteria was employed after duplicate article removal from the results of the database search. Every non-duplicate article within the search results was retained until its exclusion could be decided [14,25,26].

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram for systematic review of diagnostic performance of artificial intelligence-based computer-aided detection and diagnosis in pediatric radiology. CINAHL, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two data extraction forms (Table 1 and Table 2) were developed based on a recent systematic review on the diagnostic performance of AI-based CAD in radiology [12]. The data, including author name and country, publication year, imaging modality, diagnosis, diagnostic performance of AI-based CAD system (area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy and F1 score), AI type (such as ML and DL) and model (e.g., support vector machine, convolutional neural network (CNN), etc.) for developing the CAD system, study design (either prospective or retrospective), source (such as public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China) and size (e.g., 5858 images, etc.) of dataset for testing the CAD system, patient/population (such as 1–5-year-old children), any sample size calculation, model internal validation type (e.g., 10-fold cross-validation, etc.), any model external validation (i.e., any model testing with use of dataset not involved in internal validation and acquired from different setting), reference standard for ground truth establishment (such as histology and expert consensus), any model performance comparison with clinician and model commercial availability were extracted from each included paper. When diagnostic performance findings were reported for multiple AI-based CAD models in a study, only the values of the best performing model were presented [27]. Meta-analysis was not conducted because this systematic review covered a range of imaging modalities and pathologies, and hence, high study heterogeneity was expected, affecting its usefulness [12,13,28]. The Revised Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool was used to assess the quality of all included studies [9,12,13,19,23,27,29].

3. Results

Twenty-three articles met the selection criteria and were included in this review [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Table 1 shows their AI-based CAD application areas in the pediatric radiology and the diagnostic performances. These studies covered brain (n = 9) [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], respiratory (n = 9) [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], musculoskeletal (n = 2) [40,41], urologic (n = 2) [51,52] and cardiac imaging (n = 1) [39]. The commonest AI-based CAD application area (30.4%, 7/23) was pediatric pneumonia [43,45,46,47,48,49,50]. No study reported all seven diagnostic accuracy measures [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Most commonly, the papers (30.4%, 7/23) reported four metrics [30,32,35,42,44,45,52]. Accuracy (n = 19) and sensitivity (n = 18) were the two most frequently used evaluation metrics [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. One study only used one measure, AUC [40]. Most of the articles (93.3%, 14/15; 77.8%, 14/18; 73.3%, 11/15; 80.0%, 8/10; 66.6%, 2/3; 84.2%, 16/19; 80.0%, 8/10) reported AI-based CAD model performances of at least 0.83 (AUC), 0.84 (sensitivity), 0.80 (specificity), 0.89 (PPV), 0.63 (NPV), 0.87 (accuracy), and 0.82 (F1 score), respectively. The ranges of the reported performance values were 0.698–0.999 (AUC), 0.420–0.987 (sensitivity), 0.585–1.000 (specificity), 0.600–1.000 (PPV), 0.260–0.971 (NPV), 0.643–0.986 (accuracy), and 0.626–0.983 (F1 score) [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. For the seven studies about AI-based CAD for pneumonia, their model performances were at least 0.850 (AUC), 0.760 (sensitivity), 0.800 (specificity), 0.891 (PPV), 0.905 (accuracy) and 0.903 (F1 score).

Table 1.

Artificial intelligence-based computer-aided detection and diagnosis application areas in pediatric radiology and their diagnostic performances.

| Author, Year and Country | Modality | Diagnosis | Diagnostic Performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | F1 Score | |||

| Brain Imaging | |||||||||

| Dou et al. (2022)—China [30] | MRI | Bipolar disorder | 0.830 | 0.909 | 0.769 | NR | NR | 0.854 | NR |

| Kuttala et al. (2022)—Australia, India & United Arab Emirates [31] | MRI | ADHD and ASD | 0.850 (ADHA); 0.910 (ASD) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.854 (ADHA); 0.978 (ASD) | NR |

| Li et al. (2020)—China [32] | MRI | Posterior fossa tumors | 0.865 | 0.929 | 0.800 | NR | NR | 0.878 | NR |

| Peruzzo et al. (2016)—Italy [33] | MRI | Malformations of corpus callosum | 0.953 | 0.923 | 0.904 | 0.906 | NR | 0.914 | NR |

| Prince et al. (2020)—USA [34] | CT & MRI | ACP | 0.978 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.979 | NR |

| Tan et al. (2013)—USA [35] | MRI | Congenital sensori-neural hearing loss | 0.900 | 0.890 | 0.860 | NR | NR | 0.870 | NR |

| Xiao et al. (2019)—China [36] | MRI | ASD | NR | 0.980 | 0.936 | 0.959 | 0.971 | 0.963 | NR |

| Zahia et al. (2020)—Spain [37] | MRI | Dyslexia | NR | 0.750 | 0.714 | 0.600 | NR | 0.727 | 0.670 |

| Zhou et al. (2021)—China [38] | MRI | ADHD | 0.698 | 0.609 | 0.676 | NR | NR | 0.643 | 0.626 |

| Cardiac Imaging | |||||||||

| Lee et al. (2022)—South Korea [39] | US | Kawasaki disease | NR | 0.841 | 0.585 | 0.811 | 0.633 | 0.759 | 0.826 |

| Musculoskeletal Imaging | |||||||||

| Petibon et al. (2021)—Canada, Israel and USA [40] | SPECT | Low back pain | 0.830 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sezer and Sezer (2020)—France and Turkey [41] | US | DDH | NR | 0.962 | 0.980 | NR | NR | 0.977 | NR |

| Respiratory Imaging | |||||||||

| Behzadi—Khormouji et al. (2020)—Iran and USA [42] | X-ray | Pulmonary consolidation | 0.995 | 0.987 | 0.864 | NR | NR | 0.945 | NR |

| Bodapati and Rohith (2022)—India [43] | X-ray | Pneumonia | 0.939 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.948 | 0.959 |

| Helm et al. (2009)—Canada, UK and USA [44] | CT | Pulmonary nodules | NR | 0.420 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.260 | NR | NR |

| Jiang and Chen (2022)-China [45] | X-ray | Pneumonia | NR | 0.894 | NR | 0.918 | NR | 0.912 | 0.903 |

| Liang and Zheng (2020)-China [46] | X-ray | Pneumonia | 0.953 | 0.967 | NR | 0.891 | NR | 0.905 | 0.927 |

| Mahomed et al. (2020)-Netherlands and South Africa [47] | X-ray | Primary-endpoint pneumonia | 0.850 | 0.760 | 0.800 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Shouman et al. (2022)-Egypt and Saudi Arabia [48] | X-ray | Bacterial and viral pneumonia | 0.999 | 0.987 | 0.987 | 0.979 | NR | 0.986 | 0.983 |

| Silva et al. (2022)-Brazil [49] | X-ray | Pneumonia | NR | 0.945 | NR | 0.957 | NR | NR | 0.951 |

| Vrbančič and Podgorelec (2022)-Slovenia [50] | X-ray | Pneumonia | 0.952 | 0.976 | 0.927 | 0.973 | NR | 0.963 | 0.974 |

| Urologic Imaging | |||||||||

| Guan et al. (2022)-China [51] | US | Hydronephrosis | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.891 | 0.895 |

| Zheng et al. (2019)-China and USA [52] | US | CAKUT | 0.920 | 0.86 | 0.880 | NR | NR | 0.870 | NR |

ACP, adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AUC, area under receiver operating characteristic curve; CAKUT, congenital abnormalities of kidney and urinary tract; CT, computed tomography; DDH, developmental dysplasia of hip; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; PPV, positive predictive value; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; UK, United Kingdom; US, ultrasound; USA, United States of America.

Table 2 presents the included study characteristics. Overall, 18 out of 23 (78.3%) studies were published in the last three years [30,31,32,34,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Most of them (72.7%, 16/22) developed the DL-based CAD systems [31,34,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,48,49,50,51,52]. Of these 16 DL-based systems, 75% (n = 12) used the CNN model [34,37,39,40,41,42,43,46,48,49,50,51]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (n = 9) [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] and X-ray (n = 8) [42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50] were most frequently used by the AI-based CAD models for the brain and respiratory disease diagnoses, respectively. The majority of studies (69.6%, 16/23) collected the datasets retrospectively [31,33,34,36,38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,52]. Of these 16 retrospective studies, about one-third (n = 11) relied on the public datasets [31,34,36,38,42,43,45,46,48,49,50]; most of them (n = 7) used the chest X-ray dataset consisting of 1741 normal and 4346 pneumonia images of 6087 1–5-year-old children collected from the Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China [42,43,45,46,48,49,50]. No study calculated the sample size for the data collection [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Most of the studies (60.9%, 14/23) collected less than 233 cases [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,44,52], and about one-third (n = 7) collected data of less than 87 patients for testing their systems [30,32,34,35,37,40,44]. Hence, for the model internal validation, more than half of the studies (n = 13) used the cross-validation to address the small test set issue [30,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,47,50,51,52]. However, all but one did not conduct the external validation [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. The only exception conducted external validation for a commercial AI-based CAD system evaluation [44]. Less than one-fifth of the included studies (n = 4) used the consensus diagnosis as the reference standard (ground truth) for the model training and performance evaluation [33,42,44,47], and one-quarter (n = 6) did not report the reference standard [31,43,45,46,48,49]. Only about one-fifth (n = 5) compared their model performances with those of clinicians [33,34,40,44,47], and most of these (60%, 3/5) were the studies using the consensus diagnosis as the reference standard [33,44,47].

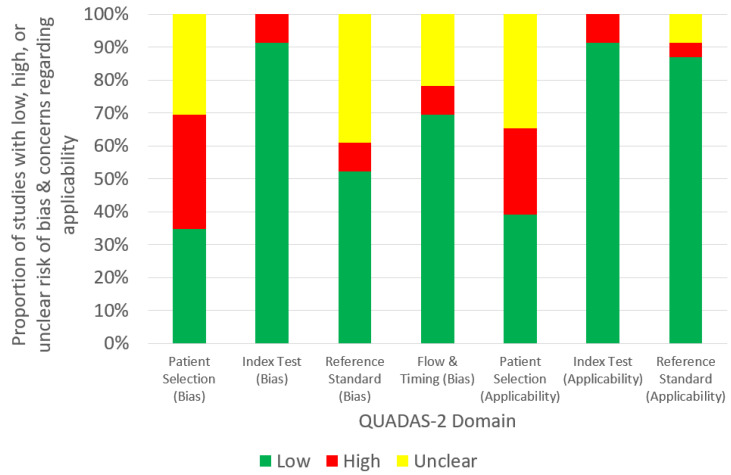

Figure 2 shows the quality assessment summary of all (23) studies based on the QUADAS-2 tool. Only around one-third of the studies had a low risk of bias [34,35,36,37,38,41,44,52] and concern regarding applicability for the patient selection category [30,34,35,36,37,38,41,44,52]. The low risk of bias of the reference standard was only noted in about half of them [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,42,47,50,52].

Table 2.

Study characteristics of artificial intelligence-based computer-aided detection and diagnosis in pediatric radiology.

| Author, Year and Country | Modality | Diagnosis | AI Type and Model | Study Design | Dataset Source | Test Set Size | Patient/Population | Sample Size Calculation | Internal Validation Type | External Validation | Reference Standard | AI vs. Clinician |

Commercial Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Imaging | |||||||||||||

| Dou et al. (2022)—China [30] | MRI | Bipolar disorder | ML-LR | Prospective | Private dataset by Second Xiangya Hospital, China | 52 scans | 12–18-year-old children | No | 2-fold cross-validation | No | Clinical diagnosis | No | No |

| Kuttala et al. (2022)—Australia, India and United Arab Emirates [31] | MRI | ADHD and ASD | DL-GAN and softmax | Retrospective | Public datasets (ADHD-200 and Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange II) | 217 scans | Children (median ages for baseline and follow-up scans: 12 and 15 years, respectively) | No | NR | No | NR | No | No |

| Li et al. (2020)—China [32] | MRI | Posterior fossa tumors | ML-SVM | Prospective | Private dataset by Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China | 45 scans | 0–14-year-old children | No | Repeated hold-out with 70:30 random split | No | Histology | No | No |

| Peruzzo et al. (2016)—Italy [33] | MRI | Malformations of corpus callosum | ML-SVM | Retrospective | Private dataset by Scientific Institute “Eugenio Medea”, Italy | 104 scans | 2–12-year-old children | No | Leave-one-out cross validation | No | Expert consensus | Yes | No |

| Prince et al. (2020)—USA [34] | CT and MRI | ACP | DL-CNN | Retrospective | Public dataset (ATPC Consortium) and private datasets by Children’s Hospital Colorado and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, USA | 86 CT-MRI scans | Children | No | 60:40 random split and 5-fold cross validation | No | Histology | Yes | No |

| Tan et al. (2013)—USA [35] | MRI | Congenital sensori-neural hearing loss | ML-SVM | Prospective | Private dataset by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, USA | 39 scans | 8–24-month-old children | No | Leave-one-out cross-validation | No | Follow-up | No | No |

| Xiao et al. (2019)—China [36] | MRI | ASD | DL-SAE and softmax | Retrospective | Public dataset (Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange II) | 198 scans | 5–12-year-old children | No | 11-, 33-, 66-, 99- and 198-fold cross-validation | No | Clinical diagnosis | No | No |

| Zahia et al. (2020)—Spain [37] | MRI | Dyslexia | DL-CNN | Prospective | Private dataset by University Hospital of Cruces, Spain | 55 scans | 9–12-year-old children | No | 4-fold cross validation | No | Clinical diagnosis | No | No |

| Zhou et al. (2021)—China [38] | MRI | ADHD | ML-SVM | Retrospective | Public dataset (Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Data Repository) | 232 scans | 9–10-year-old children | No | 10-fold cross-validation | No | Clinical diagnosis | No | No |

| Cardiac Imaging | |||||||||||||

| Lee et al. (2022)—South Korea [39] | US | Kawasaki disease | DL-CNN | Retrospective | Private dataset by Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital, South Korea | 203 scans | Children | No | 10-fold cross-validation | No | Single expert reader | No | No |

| Musculoskeletal Imaging | |||||||||||||

| Petibon et al. (2021)—Canada, Israel and USA [40] | SPECT | Low back pain | DL-CNN | Retrospective | Private dataset by Boston Children’s Hospital, USA | 65 scans | 10–17 years old children | No | 3-fold cross-validation | No | Other-ground truth established by artificial lesion insertion | Yes | No |

| Sezer and Sezer (2020)—France and Turkey [41] | US | DDH | DL-CNN | Prospective | Private dataset | 203 scans | 0–6-month-old children | No | 70:30 random split | No | Single expert reader | No | No |

| Respiratory Imaging | |||||||||||||

| Behzadi—Khormouji et al. (2020)—Iran and USA [42] | X-ray | Pulmonary consolidation | DL-CNN | Retrospective | Public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China | 582 images | 1–5-year-old children | No | 90:10 random split | No | Expert consensus | No | No |

| Bodapati and Rohith (2022)—India [43] | X-ray | Pneumonia | DL-CNN and CapsNet | Retrospective | Public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China | 640 images | 1–5-year-old children | No | NR | No | NR | No | No |

| Helm et al. (2009)—Canada, UK and USA [44] | CT | Pulmonary nodules | NR | Retrospective | Private dataset by a tertiary pediatric hospital | 29 scans | 3 years and 11 months to 18-year-old children | No | NR | Yes | Expert and reader consensus | Yes | Yes |

| Jiang and Chen (2022)—China [45] | X-ray | Pneumonia | DL-ViT | Retrospective | Public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China | 624 images | 1–5-year-old children | No | NR | No | NR | No | No |

| Liang and Zheng (2020)—China [46] | X-ray | Pneumonia | DL-CNN | Retrospective | Public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China | 624 images | 1–5-year-old children | No | 90:10 random split | No | NR | No | No |

| Mahomed et al. (2020)—Netherlands and South Africa [47] | X-ray | Primary-endpoint pneumonia | ML-SVM | Prospective | Private dataset by Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, South Africa | 858 digitized images | 1–59-month-old children | No | 10-fold cross-validation | No | Reader consensus | Yes | No |

| Shouman et al. (2022)—Egypt and Saudi Arabia [48] | X-ray | Bacterial and viral pneumonia | DL-CNN and LSTM | Retrospective | Public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China | 586 images | 1–5-year-old children | No | 90:10 random split | No | NR | No | No |

| Silva et al. (2022)—Brazil [49] | X-ray | Pneumonia | DL-CNN | Retrospective | Public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China | 1172 images | 1–5-year-old children | No | NR | No | NR | No | No |

| Vrbančič and Podgorelec (2022)—Slovenia [50] | X-ray | Pneumonia | DL-CNN and SGD | Retrospective | Public dataset by Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China | 5858 images | 1–5-year-old children | No | 10-fold cross-validation | No | Expert readers | No | No |

| Urologic Imaging | |||||||||||||

| Guan et al. (2022)—China [51] | US | Hydronephrosis | DL-CNN | Prospective | Private dataset by Beijing Children’s Hospital, China | 3257 images | Children | No | 10-fold cross-validation | No | Readers and experts without consensus | No | No |

| Zheng et al. (2019)—China and USA [52] | US | CAKUT | DL-SVM | Retrospective | Private dataset by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, USA | 100 scans | Children with mean age of 111 days (SD: 262) | No | 10-fold cross-validation | No | Clinical diagnosis | No | No |

ACP, adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AI, artificial intelligence; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ATPC, Advancing Treatment for Pediatric Craniopharyngioma; CAKUT, congenital abnormalities of kidney and urinary tract; CapsNet, capsule network; CNN, convolutional neural network; CT, computed tomography; DDH, developmental dysplasia of hip; DL, deep learning; GAN, generative adversarial network; LR, logistic regression; LSTM, long short-term memory; ML, machine learning; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NR, not reported; SAE, stacked auto-encoder; SD, standard deviation; SGD, stochastic gradient descent; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; SVM, support vector machine; UK, United Kingdom; US, ultrasound; USA, United States of America; ViT, vision transformer.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment summary of all (23) included studies based on Revised Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool.

4. Discussion

This article is the first systematic review on the diagnostic performance of the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology covering the brain [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], respiratory [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], musculoskeletal [40,41], urologic [51,52] and cardiac imaging [39]. Hence, it advances the previous two narrative reviews about various uses of AI in the pediatric radiology [17] and the AI-based CAD in the pediatric chest imaging [16] published in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Most of the included studies reported AI-based CAD model performances of at least 0.83 (AUC), 0.84 (sensitivity), 0.80 (specificity), 0.89 (PPV), 0.63 (NPV), 0.87 (accuracy), and 0.82 (F1 score) [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. However, the diagnostic performances of these CAD systems appeared a bit lower than those reported in the systematic review of the AI-based CAD in the radiology (pooled sensitivity and specificity: 0.87 and 0.93, respectively) [10]. In addition, the pediatric pneumonia was the only disease that was investigated by more than two studies [43,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Although these studies reported that their CAD performances for the pneumonia diagnosis were at least 0.850 (AUC), 0.760 (sensitivity), 0.800 (specificity), 0.891 (PPV), 0.905 (accuracy) and 0.903 (F1 score), which would be sufficient to support less experienced pediatric radiologists in image interpretation, all but one were the retrospective studies and relied on the chest X-ray dataset consisting of 1741 normal and 4346 pneumonia images of 6087 1–5-year-old children collected from the Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, China [13,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. It is noted that the use of the public dataset could facilitate AI-based CAD model performance comparison with other similar studies [43]. On the other hand, this approach would affect the model generalization ability (i.e., unable to maintain the performance when applying to different settings), causing the model to be unfit for real clinical situations [10,46]. Although techniques such as the cross-validation can be used to improve the AI-based CAD model generalization ability [37], only one of these studies used the cross-validation approach [50], while half of them did not report the internal validation type [43,45,49]. In addition, some ground truths given in the public datasets might be inaccurate, indicating potential reference standard issues [10,42]. These studies did not calculate the required sample size; perform the external validation; and compare their model performances with radiologists, but they are essential for the demonstration of the trustworthiness of study findings [43,45,46,48,49,50]. As per Table 2, the aforementioned methodological issues were also common for other included studies. These issues are found in many studies about the AI-based CAD in the radiology as well [10,12,13].

Table 2 reveals that the DL and its model, CNN, were commonly used for the development of the AI-based CAD systems in the pediatric radiology similar to the situation in the radiology [13]. According to the recent narrative review about the AI-based CAD in the pediatric chest imaging published in 2022, 144 Conformité Européenne-marked AI-based CAD systems for brain (35%), respiratory, (27%), musculoskeletal (11%), breast (11%), other (7%), abdominal (6%) and cardiac (4%) imaging were commercially available in the radiology [16]. The proportions of these systems are comparable to the findings of this systematic review that the brain, respiratory and musculoskeletal imaging were the three most popular application areas of the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology and the cardiac imaging was the least (Table 1). However, except for Helm et al.’s retrospective study about the detection of pediatric pulmonary nodules in 29 3–18-year-old patients with the use of the AI-based CAD system developed for adults [44], no commercial system was involved in the included studies (Table 2) [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Helm et al.’s study [44] was the only one that performed the external validation of the CAD system with the reference standard established by the consensus of six radiologists, and one of the few compared the CAD performance with the clinicians. However, that study only used four evaluation measures: sensitivity (0.42), specificity (1.00), PPV (1.00) and NPV (0.26), and the other metrics commonly used in more clinically focused studies, AUC and accuracy, were not reported [10,12,44,53]. This highlights that even for a more clinically focused AI-based CAD study in the pediatric radiology with the better design, the common methodological weaknesses such as the retrospective data collection with limited information of patient characteristics reported and cases included, and no sample size calculation, were still prevalent (Table 2) [44,54,55]. Hence, these explain the findings in Figure 2 that the concern regarding applicability was found in the patient selection, and the risk of bias was noted in both patient selection and reference standard categories, although similar results were also reported in the systematic reviews of the AI-based CAD in the radiology [10,12].

Apparently, the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology is less developed when compared to its adult counterpart. For example, not many studies were published before 2020 [33,35,36,44,52,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], and the studies mainly focused on the MRI and X-ray and particular patient cohorts [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] (Table 2). Although Schalekamp et al.’s [16] narrative review published in 2022 suggested the use of the AI-based CAD designed for the adult population in children, Helm et al.’s [44] study demonstrated that this approach yielded low sensitivity (0.42) and NPV (0.26) in detecting pediatric pulmonary nodules because of the smaller nodule sizes in children. Hence, AI-based CAD systems specifically designed/finetuned for the pediatric radiology by researchers and/or commercial companies seem necessary in the future. In addition, for further research, more robust study designs that can address the aforementioned methodological issues (especially the lack of the external validation) are essential for providing trustworthy findings to convince clinical centers to adopt the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology. In this way, the potential benefits of the CAD could be realized in a wider context [5,10,12,13].

This systematic review has two major limitations. The article selection, data extraction, and synthesis were performed by a single author, albeit one with more than 20 years of experience in conducting the literature reviews [14]. According to a recent methodological systematic review, this is an appropriate arrangement provided that the single reviewer is experienced [14,24,77,78,79]. Additionally, through adherence to the PRISMA guidelines and the use of the data extraction forms (Table 1 and Table 2) devised based on the recent systematic review on the diagnostic performance of the AI-based CAD in the radiology and the QUADAS-2 tool, the potential bias should be addressed to a certain extent [12,14,26,29]. In addition, only articles in English identified via databases were included, potentially affecting the comprehensiveness of this systematic review [9,21,26,27,80]. Nevertheless, this review still has a wider coverage about the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology than the previous two narrative reviews [16,17].

5. Conclusions

This systematic review shows that the AI-based CAD for the pediatric radiology could be applied in the brain, respiratory, musculoskeletal, urologic and cardiac imaging. Most of the studies (93.3%, 14/15; 77.8%, 14/18; 73.3%, 11/15; 80.0%, 8/10; 66.6%, 2/3; 84.2%, 16/19; 80.0%, 8/10) reported AI-based CAD model performances of at least 0.83 (AUC), 0.84 (sensitivity), 0.80 (specificity), 0.89 (PPV), 0.63 (NPV), 0.87 (accuracy), and 0.82 (F1 score), respectively. The pediatric pneumonia was the most common pathology covered in the included studies. They reported that their CAD performances for pneumonia diagnosis were at least 0.850 (AUC), 0.760 (sensitivity), 0.800 (specificity), 0.891 (PPV), 0.905 (accuracy) and 0.903 (F1 score). Although these diagnostic performances appear sufficient to support the less experienced pediatric radiologists in the image interpretation, a range of methodological weaknesses such as the retrospective data collection, no sample size calculation, overreliance on public dataset, small test set size, limited patient cohort coverage, use of diagnostic accuracy measures and cross-validation, lack of model external validation and model performance comparison with clinicians, and risk of bias of reference standard are found in the included studies. Hence, their AI-based CAD systems might be unfit for the real clinical situations due to a lack of generalization ability. In the future, more AI-based CAD systems specifically designed/fine-tuned for a wider range of imaging modalities and pathologies in the pediatric radiology should be developed. In addition, more robust study designs should be used in further research to address the aforementioned methodological issues for providing the trustworthy findings to convince the clinical centers to adopt the AI-based CAD in the pediatric radiology. In this way, the potential benefits of the CAD could be realized in a wider context.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Lu Y., Zheng N., Ye M., Zhu Y., Zhang G., Nazemi E., He J. Proposing intelligent approach to predicting air kerma within radiation beams of medical x-ray imaging systems. Diagnostics. 2023;13:190. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun Z., Ng C.K.C. Artificial intelligence (enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial network) for calcium deblooming in coronary computed tomography angiography: A feasibility study. Diagnostics. 2022;12:991. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12040991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun Z., Ng C.K.C. Finetuned super-resolution generative adversarial network (artificial intelligence) model for calcium deblooming in coronary computed tomography angiography. J. Pers. Med. 2022;12:1354. doi: 10.3390/jpm12091354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng C.K.C., Leung V.W.S., Hung R.H.M. Clinical evaluation of deep learning and atlas-based auto-contouring for head and neck radiation therapy. Appl. Sci. 2022;12:11681. doi: 10.3390/app122211681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choy G., Khalilzadeh O., Michalski M., Do S., Samir A.E., Pianykh O.S., Geis J.R., Pandharipande P.V., Brink J.A., Dreyer K.J. Current applications and future impact of machine learning in radiology. Radiology. 2018;288:318–328. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018171820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan H.P., Hadjiiski L.M., Samala R.K. Computer-aided diagnosis in the era of deep learning. Med. Phys. 2020;47:e218–e227. doi: 10.1002/mp.13764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki K. A review of computer-aided diagnosis in thoracic and colonic imaging. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2012;2:163–176. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2012.09.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wardlaw J.M., Mair G., von Kummer R., Williams M.C., Li W., Storkey A.J., Trucco E., Liebeskind D.S., Farrall A., Bath P.M., et al. Accuracy of automated computer-aided diagnosis for stroke imaging: A critical evaluation of current evidence. Stroke. 2022;53:2393–2403. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris M., Qi A., Jeagal L., Torabi N., Menzies D., Korobitsyn A., Pai M., Nathavitharana R.R., Ahmad Khan F. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence-based computer programs to analyze chest x-rays for pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0221339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X., Faes L., Kale A.U., Wagner S.K., Fu D.J., Bruynseels A., Mahendiran T., Moraes G., Shamdas M., Kern C., et al. A comparison of deep learning performance against health-care professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Heal. 2019;1:e271–e297. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masud R., Al-Rei M., Lokker C. Computer-aided detection for breast cancer screening in clinical settings: Scoping review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2019;7:e12660. doi: 10.2196/12660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggarwal R., Sounderajah V., Martin G., Ting D.S.W., Karthikesalingam A., King D., Ashrafian H., Darzi A. Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning in medical imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021;4:65. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasey B., Ursprung S., Beddoe B., Taylor E.H., Marlow N., Bilbro N., Watkinson P., McCulloch P. Association of clinician diagnostic performance with machine learning-based decision support systems: A systematic review. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e211276. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng C.K.C. Artificial intelligence for radiation dose optimization in pediatric radiology: A systematic review. Children. 2022;9:1044. doi: 10.3390/children9071044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Mahrooqi K.M.S., Ng C.K.C., Sun Z. Pediatric computed tomography dose optimization strategies: A literature review. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2015;46:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schalekamp S., Klein W.M., van Leeuwen K.G. Current and emerging artificial intelligence applications in chest imaging: A pediatric perspective. Pediatr. Radiol. 2022;52:2120–2130. doi: 10.1007/s00247-021-05146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davendralingam N., Sebire N.J., Arthurs O.J., Shelmerdine S.C. Artificial intelligence in paediatric radiology: Future opportunities. Br. J. Radiol. 2021;94:20200975. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20200975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K.W., Lee J., Choi S.H., Huh J., Park S.H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating diagnostic test accuracy: A practical review for clinical researchers-Part I. general guidance and tips. Korean J. Radiol. 2015;16:1175–1187. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.6.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao W.J., Fu L.R., Huang Z.M., Zhu J.Q., Ma B.Y. Effectiveness evaluation of computer-aided diagnosis system for the diagnosis of thyroid nodules on ultrasound: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98:e16379. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devnath L., Summons P., Luo S., Wang D., Shaukat K., Hameed I.A., Aljuaid H. Computer-aided diagnosis of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis in chest x-ray radiographs using machine learning: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:6439. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groen A.M., Kraan R., Amirkhan S.F., Daams J.G., Maas M. A systematic review on the use of explainability in deep learning systems for computer aided diagnosis in radiology: Limited use of explainable AI? Eur. J. Radiol. 2022;157:110592. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2022.110592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriksen E.L., Carlsen J.F., Vejborg I.M., Nielsen M.B., Lauridsen C.A. The efficacy of using computer-aided detection (CAD) for detection of breast cancer in mammography screening: A systematic review. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:13–18. doi: 10.1177/0284185118770917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gundry M., Knapp K., Meertens R., Meakin J.R. Computer-aided detection in musculoskeletal projection radiography: A systematic review. Radiography. 2018;24:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waffenschmidt S., Knelangen M., Sieben W., Bühn S., Pieper D. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: A methodological systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019;19:132. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0782-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng C.K.C. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pre-registration medical radiation science education. Radiography. 2022;28:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2021.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.PRISMA: Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. [(accessed on 25 January 2023)]. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org.

- 27.Xu L., Gao J., Wang Q., Yin J., Yu P., Bai B., Pei R., Chen D., Yang G., Wang S., et al. Computer-aided diagnosis systems in diagnosing malignant thyroid nodules on ultrasonography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Thyroid J. 2020;9:186–193. doi: 10.1159/000504390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imrey P.B. Limitations of meta-analyses of studies with high heterogeneity. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3:e1919325. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whiting P.F., Rutjes A.W., Westwood M.E., Mallett S., Deeks J.J., Reitsma J.B., Leeflang M.M., Sterne J.A., Bossuyt P.M., QUADAS-2 Group QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dou R., Gao W., Meng Q., Zhang X., Cao W., Kuang L., Niu J., Guo Y., Cui D., Jiao Q., et al. Machine learning algorithm performance evaluation in structural magnetic resonance imaging-based classification of pediatric bipolar disorders type I patients. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2022;16:915477. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2022.915477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuttala D., Mahapatra D., Subramanian R., Oruganti V.R.M. Dense attentive GAN-based one-class model for detection of autism and ADHD. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022;34:10444–10458. doi: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2022.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M., Wang H., Shang Z., Yang Z., Zhang Y., Wan H. Ependymoma and pilocytic astrocytoma: Differentiation using radiomics approach based on machine learning. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020;78:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peruzzo D., Arrigoni F., Triulzi F., Righini A., Parazzini C., Castellani U. A framework for the automatic detection and characterization of brain malformations: Validation on the corpus callosum. Med. Image Anal. 2016;32:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prince E.W., Whelan R., Mirsky D.M., Stence N., Staulcup S., Klimo P., Anderson R.C.E., Niazi T.N., Grant G., Souweidane M., et al. Robust deep learning classification of adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma from limited preoperative radiographic images. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16885. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan L., Chen Y., Maloney T.C., Caré M.M., Holland S.K., Lu L.J. Combined analysis of sMRI and fMRI imaging data provides accurate disease markers for hearing impairment. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;3:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao Z., Wu J., Wang C., Jia N., Yang X. Computer-aided diagnosis of school-aged children with ASD using full frequency bands and enhanced SAE: A multi-institution study. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019;17:4055–4063. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zahia S., Garcia-Zapirain B., Saralegui I., Fernandez-Ruanova B. Dyslexia detection using 3D convolutional neural networks and functional magnetic resonance imaging. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;197:105726. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou X., Lin Q., Gui Y., Wang Z., Liu M., Lu H. Multimodal MR images-based diagnosis of early adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using multiple kernel learning. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15:710133. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.710133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H., Eun Y., Hwang J.Y., Eun L.Y. Explainable deep learning algorithm for distinguishing incomplete Kawasaki disease by coronary artery lesions on echocardiographic imaging. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;223:106970. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.106970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petibon Y., Fahey F., Cao X., Levin Z., Sexton-Stallone B., Falone A., Zukotynski K., Kwatra N., Lim R., Bar-Sever Z., et al. Detecting lumbar lesions in 99m Tc-MDP SPECT by deep learning: Comparison with physicians. Med. Phys. 2021;48:4249–4261. doi: 10.1002/mp.15033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sezer A., Sezer H.B. Deep convolutional neural network-based automatic classification of neonatal hip ultrasound images: A novel data augmentation approach with speckle noise reduction. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020;46:735–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Behzadi-Khormouji H., Rostami H., Salehi S., Derakhshande-Rishehri T., Masoumi M., Salemi S., Keshavarz A., Gholamrezanezhad A., Assadi M., Batouli A. Deep learning, reusable and problem-based architectures for detection of consolidation on chest x-ray images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;185:105162. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bodapati J.D., Rohith V.N. ChxCapsNet: Deep capsule network with transfer learning for evaluating pneumonia in paediatric chest radiographs. Measurement. 2022;188:110491. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2021.110491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helm E.J., Silva C.T., Roberts H.C., Manson D., Seed M.T., Amaral J.G., Babyn P.S. Computer-aided detection for the identification of pulmonary nodules in pediatric oncology patients: Initial experience. Pediatr. Radiol. 2009;39:685–693. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang Z., Chen L. Multisemantic level patch merger vision transformer for diagnosis of pneumonia. Comput. Math. Method Med. 2022;2022:7852958. doi: 10.1155/2022/7852958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang G., Zheng L. A transfer learning method with deep residual network for pediatric pneumonia diagnosis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;187:104964. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahomed N., van Ginneken B., Philipsen R.H.H.M., Melendez J., Moore D.P., Moodley H., Sewchuran T., Mathew D., Madhi S.A. Computer-aided diagnosis for World Health Organization-defined chest radiograph primary-endpoint pneumonia in children. Pediatr. Radiol. 2020;50:482–491. doi: 10.1007/s00247-019-04593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shouman M.A., El-Fiky A., Hamada S., El-Sayed A., Karar M.E. Computer-assisted lung diseases detection from pediatric chest radiography using long short-term memory networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022;103:108402. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva L., Araújo L., Ferreira V., Neto R., Santos A. Convolutional neural networks applied in the detection of pneumonia by x-ray images. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Appl. 2022;13:187–197. doi: 10.1504/IJICA.2022.125655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vrbančič G., Podgorelec V. Efficient ensemble for image-based identification of pneumonia utilizing deep CNN and SGD with warm restarts. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022;187:115834. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guan Y., Peng H., Li J., Wang Q. A mutual promotion encoder-decoder method for ultrasonic hydronephrosis diagnosis. Methods. 2022;203:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2022.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng Q., Furth S.L., Tasian G.E., Fan Y. Computer-aided diagnosis of congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract in children based on ultrasound imaging data by integrating texture image features and deep transfer learning image features. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2019;15:75.e1–75.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kleinfelder T.R., Ng C.K.C. Effects of image postprocessing in digital radiography to detect wooden, soft tissue foreign bodies. [(accessed on 30 January 2023)];Radiol. Technol. 2022 93:544–554. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35790309/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun Z., Ng C.K.C., Wong Y.H., Yeong C.H. 3D-printed coronary plaques to simulate high calcification in the coronary arteries for investigation of blooming artifacts. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1307. doi: 10.3390/biom11091307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng C.K.C., Sun Z. Development of an online automatic computed radiography dose data mining program: A preliminary study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;97:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christe A., Peters A.A., Drakopoulos D., Heverhagen J.T., Geiser T., Stathopoulou T., Christodoulidis S., Anthimopoulos M., Mougiakakou S.G., Ebner L. Computer-aided diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis using deep learning and CT images. Investig. Radiol. 2019;54:627–632. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka H., Chiu S.W., Watanabe T., Kaoku S., Yamaguchi T. Computer-aided diagnosis system for breast ultrasound images using deep learning. Phys. Med. Biol. 2019;64:235013. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab5093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim H.L., Ha E.J., Han M. Real-world performance of computer-aided diagnosis system for thyroid nodules using ultrasonography. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2019;45:2672–2678. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeongy E.Y., Kim H.L., Ha E.J., Park S.Y., Cho Y.J., Han M. Computer-aided diagnosis system for thyroid nodules on ultrasonography: Diagnostic performance and reproducibility based on the experience level of operators. Eur. Radiol. 2019;29:1978–1985. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park H.J., Kim S.M., La Yun B., Jang M., Kim B., Jang J.Y., Lee J.Y., Lee S.H. A computer-aided diagnosis system using artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and characterization of breast masses on ultrasound: Added value for the inexperienced breast radiologist. Medicine. 2019;98:e14146. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang S., Sun F., Wang N., Zhang C., Yu Q., Zhang M., Babyn P., Zhong H. Computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) of pulmonary nodule of thoracic CT image using transfer learning. J. Digit. Imaging. 2019;32:995–1007. doi: 10.1007/s10278-019-00204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei R., Lin K., Yan W., Guo Y., Wang Y., Li J., Zhu J. Computer-aided diagnosis of pancreas serous cystic neoplasms: A radiomics method on preoperative MDCT images. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019;18:1533033818824339. doi: 10.1177/1533033818824339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen C.H., Lee Y.W., Huang Y.S., Lan W.R., Chang R.F., Tu C.Y., Chen C.Y., Liao W.C. Computer-aided diagnosis of endobronchial ultrasound images using convolutional neural network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2019;177:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gong J., Liu J., Hao W., Nie S., Wang S., Peng W. Computer-aided diagnosis of ground-glass opacity pulmonary nodules using radiomic features analysis. Phys. Med. Biol. 2019;64:135015. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li L., Liu Z., Huang H., Lin M., Luo D. Evaluating the performance of a deep learning-based computer-aided diagnosis (DL-CAD) system for detecting and characterizing lung nodules: Comparison with the performance of double reading by radiologists. Thorac. Cancer. 2019;10:183–192. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bajaj V., Pawar M., Meena V.K., Kumar M., Sengur A., Guo Y. Computer-aided diagnosis of breast cancer using bi-dimensional empirical mode decomposition. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019;31:3307–3315. doi: 10.1007/s00521-017-3282-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nayak A., Baidya Kayal E., Arya M., Culli J., Krishan S., Agarwal S., Mehndiratta A. Computer-aided diagnosis of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma using multi-phase abdomen CT. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2019;14:1341–1352. doi: 10.1007/s11548-019-01991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Greer M.D., Lay N., Shih J.H., Barrett T., Bittencourt L.K., Borofsky S., Kabakus I., Law Y.M., Marko J., Shebel H., et al. Computer-aided diagnosis prior to conventional interpretation of prostate mpMRI: An international multi-reader study. Eur. Radiol. 2018;28:4407–4417. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5374-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ishioka J., Matsuoka Y., Uehara S., Yasuda Y., Kijima T., Yoshida S., Yokoyama M., Saito K., Kihara K., Numao N., et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of prostate cancer on magnetic resonance imaging using a convolutional neural network algorithm. BJU Int. 2018;122:411–417. doi: 10.1111/bju.14397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song Y., Zhang Y.D., Yan X., Liu H., Zhou M., Hu B., Yang G. Computer-aided diagnosis of prostate cancer using a deep convolutional neural network from multiparametric MRI. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging. 2018;48:1570–1577. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoo Y.J., Ha E.J., Cho Y.J., Kim H.L., Han M., Kang S.Y. Computer-aided diagnosis of thyroid nodules via ultrasonography: Initial clinical experience. Korean J. Radiol. 2018;19:665–672. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.4.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Al-Antari M.A., Al-Masni M.A., Choi M.T., Han S.M., Kim T.S. A fully integrated computer-aided diagnosis system for digital x-ray mammograms via deep learning detection, segmentation, and classification. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018;117:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi Y.J., Baek J.H., Park H.S., Shim W.H., Kim T.Y., Shong Y.K., Lee J.H. A computer-aided diagnosis system using artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and characterization of thyroid nodules on ultrasound: Initial clinical assessment. Thyroid. 2017;27:546–552. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li S., Jiang H., Wang Z., Zhang G., Yao Y.D. An effective computer aided diagnosis model for pancreas cancer on PET/CT images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018;165:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang C.C., Chen H.H., Chang Y.C., Yang M.Y., Lo C.M., Ko W.C., Lee Y.F., Liu K.L., Chang R.F. Computer-aided diagnosis of liver tumors on computed tomography images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2017;145:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cho E., Kim E.K., Song M.K., Yoon J.H. Application of computer-aided diagnosis on breast ultrasonography: Evaluation of diagnostic performances and agreement of radiologists according to different levels of experience. J. Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:209–216. doi: 10.1002/jum.14332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun Z., Ng C.K.C., Sá Dos Reis C. Synchrotron radiation computed tomography versus conventional computed tomography for assessment of four types of stent grafts used for endovascular treatment of thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2018;8:609–620. doi: 10.21037/qims.2018.07.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Almutairi A.M., Sun Z., Ng C., Al-Safran Z.A., Al-Mulla A.A., Al-Jamaan A.I. Optimal scanning protocols of 64-slice CT angiography in coronary artery stents: An in vitro phantom study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2010;74:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun Z., Ng C.K.C. Use of synchrotron radiation to accurately assess cross-sectional area reduction of the aortic branch ostia caused by suprarenal stent wires. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2017;24:870–879. doi: 10.1177/1526602817732315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zebari D.A., Ibrahim D.A., Zeebaree D.Q., Haron H., Salih M.S., Damaševičius R., Mohammed M.A. Systematic review of computing approaches for breast cancer detection based computer aided diagnosis using mammogram images. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021;35:2157–2203. doi: 10.1080/08839514.2021.2001177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.