Abstract

Age is the key risk factor for diseases and disabilities of the elderly. Efforts to tackle age-related diseases and increase healthspan have suggested targeting the ageing process itself to ‘rejuvenate’ physiological functioning. However, achieving this aim requires measures of biological age and rates of ageing at the molecular level. Spurred by recent advances in high-throughput omics technologies, a new generation of tools to measure biological ageing now enables the quantitative characterization of ageing at molecular resolution. Epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic data can be harnessed with machine learning to build ‘ageing clocks’ with demonstrated capacity to identify new biomarkers of biological ageing.

Globally, the human population is rapidly ageing but our healthspan — the period of life free from disease — has not increased in kind1. Ageing contributes to many diseases that affect all organ systems and is the greatest risk factor for heart disease, neurodegeneration and cancer2. These age-associated diseases have largely been treated as unique pathologies separate from the ageing process. Only recently have scientists begun to ask whether ageing itself could be addressed as a shared root cause of disease3,4. Several breakthrough studies in the past decades have, for the first time, raised the realistic possibility to extend lifespan and healthspan5. Genes that regulate lifespan in animal models6–9 and human studies10–14 as well as multiple experimental paradigms, such as caloric restriction, heterochronic parabiosis and partial epigenetic reprogramming, have demonstrated that it is possible to manipulate ageing biology to ‘rejuvenate’ physiological functioning in complex model organisms15–28. However, translating the aforementioned interventions to the clinic requires the measurement of an individual’s biological age and rates of biological ageing. As such, molecular biomarkers that reflect the biological age of a cell type, tissue, organ (such as the heart or brain) or whole organism are needed to develop drugs that target ageing.

Biological ageing is enormously complex and is thought to be driven by the interaction of multiple dysregulated cellular and biochemical processes3,4. Nearly every biological process is affected by ageing, and countless biomarkers have been proposed to try and measure it29–38 (FIG. 1). These range from obvious physical features, such as greying hair39, to molecular changes such as leukocyte telomere length40. In the past decade, the advent of omics approaches has made it possible for the field to begin tackling the full molecular complexity of ageing biology (FIG. 1). High-throughput genomic, proteomic and metabolomic methods are enabling the characterization and quantification of thousands of epigenetic marks, transcripts, proteins and metabolites, and are beginning to reveal how complex organisms change globally with age at the molecular level41,42. However, the availability of large-scale omics data has posed new challenges for the analysis and interpretation of molecular ageing. Increasingly, the field has turned to machine learning techniques to distil omics data into composite ageing biomarkers that help interpret the complex biology of ageing and guide clinical decision-making (BOX 1 and FIG. 2).

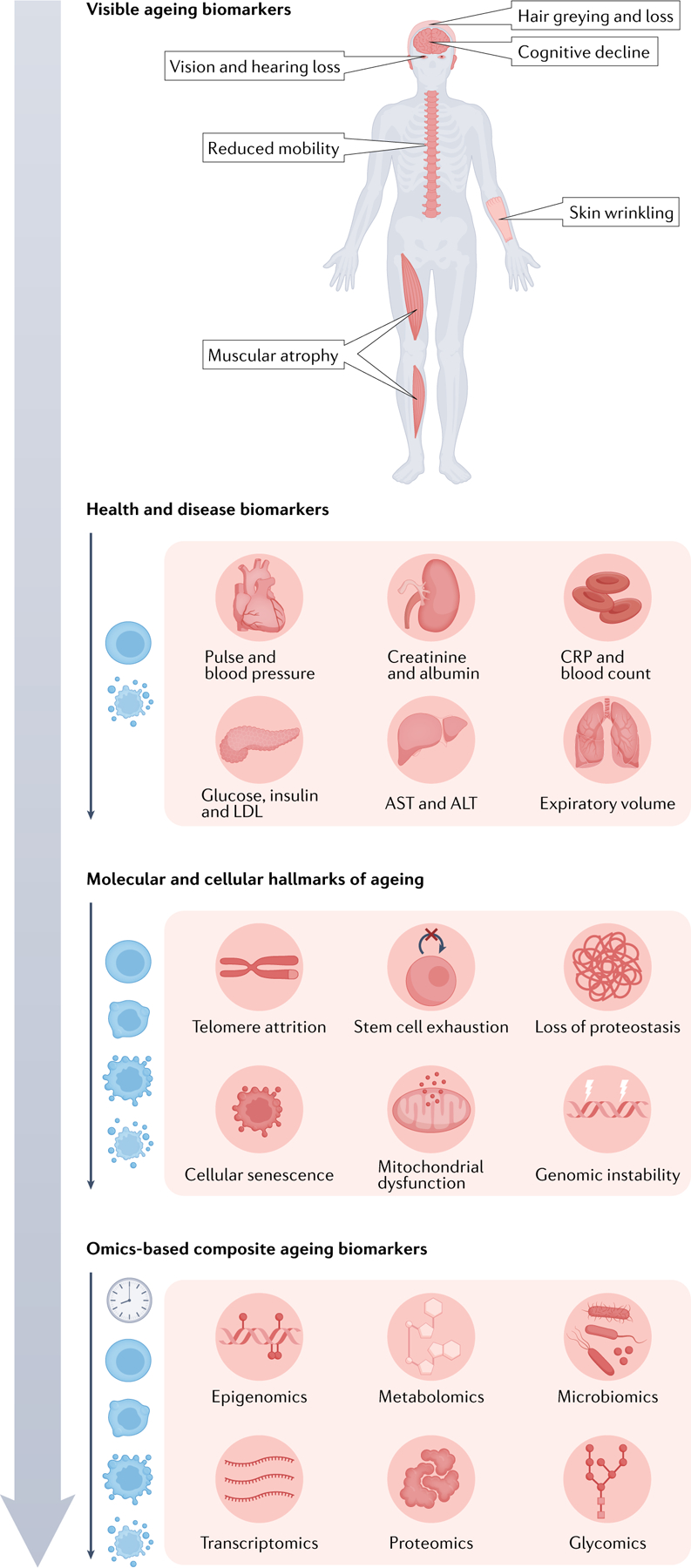

Fig. 1 |. Classes of ageing biomarkers.

Obvious features of ageing (top), such as muscular frailty and greying hair, have been used since ancient times to assess an individual’s biological age. However, with the advent of modern biomedicine, the diagnosis of health versus disease using physical and molecular readouts of organ function (second from top), such as blood pressure, inflammatory markers and metabolic markers, became the primary focus. Only recently have we turned our attention to assessing biological age by leveraging advances in cellular and molecular biology. Hallmarks of ageing (third from top), such as telomere shortening and cellular senescence, became the modern scientific framework for understanding ageing that has guided investigation of ageing at the molecular level. This has led, in part, to the development of omics-based ageing clock biomarkers of ageing (bottom), which attempt to integrate the entire breadth of molecular changes that occur with ageing into composite measures of biological age.

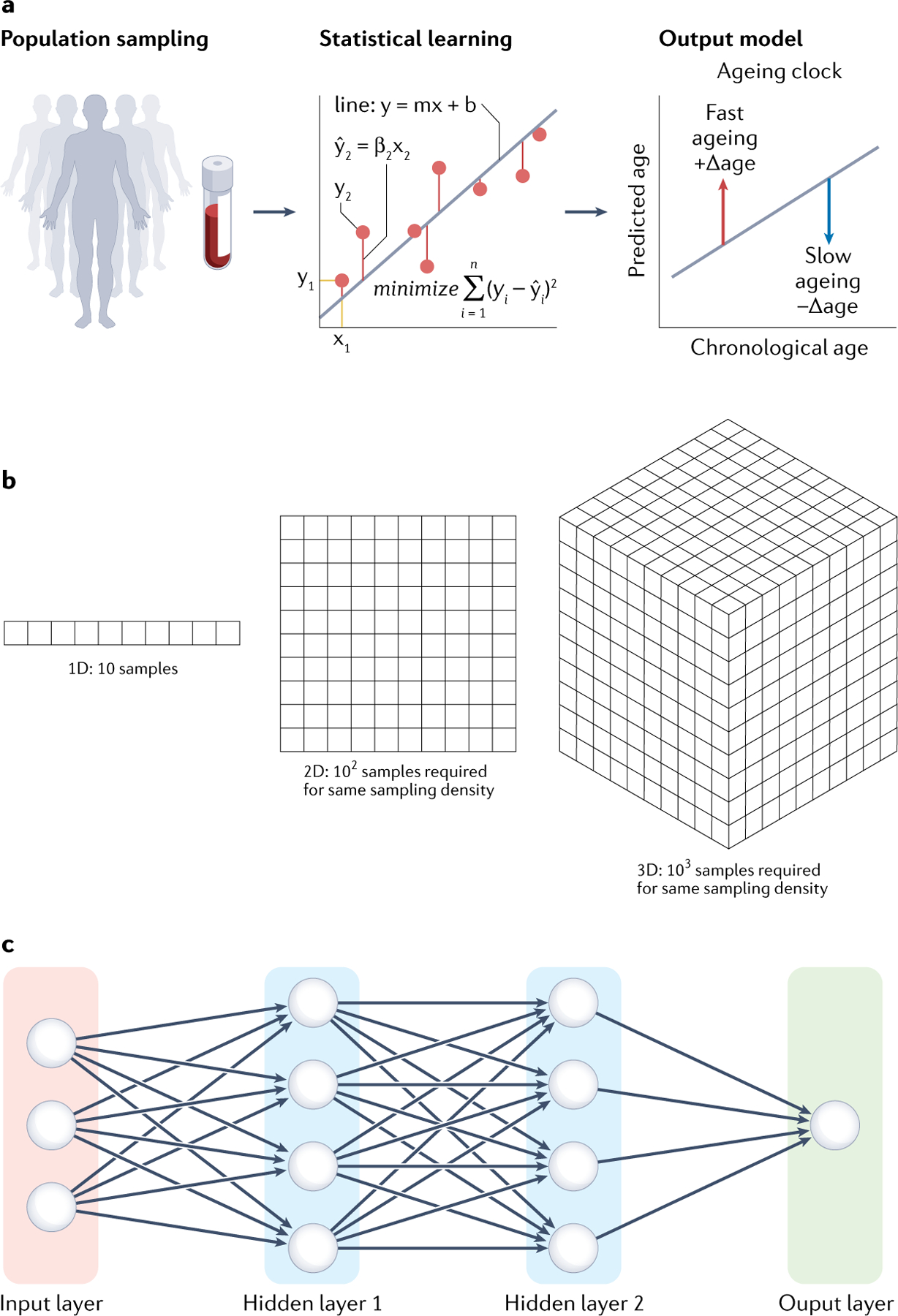

Box 1 |. Machine learning models for building ageing clocks.

Ageing clocks are machine learning models that learn mathematical formulas to estimate an individual’s age from features that vary with age across the lifespan (such as gene expression levels). The most prevalent models are linear regression-based models, where a line of best fit — or plane of best fit in multidimensional data — is calculated through the feature and age data. More specifically, ‘best fit’ is determined as the plane that minimizes a cost function, typically the residual squared error of all predictions (FIG. 2a). What results is an equation that predicts age with a linear combination of weighted features (, where Xi is the vector of values of feature i and βi is the corresponding weight that minimizes the cost function), which can be applied to other datasets. These models are advantageous because of their interpretability — if a feature is assigned a positive weight, then a higher value of that feature directly corresponds to a higher predicted age and the more positive the stronger the effect of that feature. However, standard linear models are often problematic when applied to omics data. If there are more molecular features than samples (that is, 20,000 genes and 4,000 samples), it becomes very difficult to learn correct relationships in the data. One reason is the curse of dimensionality (FIG. 2b): the number of samples needed to obtain the full distribution of data grows exponentially with the number of variables measured in each sample. Another reason is the complex correlation structure of omics data, which linear regression cannot deal with well.

Therefore, penalized linear regression models, namely lasso193, ridge194 and elastic net195 regression, are widely used to reduce the number of features (create sparsity) in linear models and to account for strong correlations between features. The vast majority of omics ageing clocks have been built with variations of these methods (or, occasionally, other sparse linear regression methods). These models work by imposing a penalty for adding more features. The exact form of the penalty varies but they all have the effect of reducing the weights of highly correlated or less informative features, sometimes down to zero, such that only a subset of important features is selected. Although similar in concept, each of these regression approaches is subtly different and may measure different ageing signals. One study showed that both ridge and elastic net clocks could detect decelerated ageing in calorie-restricted mice but only the ridge clock could detect the decelerated ageing of long-living dwarf mice196, suggesting that model selection may be important, depending on the dataset.

Other machine learning models commonly used for ageing clocks include support vector machines197, decision trees198 and neural networks199. Deep neural networks are an especially exciting approach that has shown promise in several different fields when applied to large-scale data200. There are several types of neural networks but the basic principle is to connect a large number of simple nodes (‘neurons’) to learn more complex non-linear relationships from data (FIG. 2c). Neural networks do not perform well with small datasets but they tend to vastly outperform other models if they can be trained on large datasets of tens to hundreds of thousands of samples. As the scale of omics data grows, neural networks are being increasingly used to build ageing clocks of various omic types and have demonstrated some measurements of biological age84,137,171,201. However, given their complexity, neural networks are more difficult to interpret than other models because it is not usually possible to infer the biological relationships in the data the network has learned. Nevertheless, there is progress in designing interpretable neural networks by explicitly encoding specific biological pathways into their structure202 or back-propagating information to input features203; these exciting approaches may better capture the complexity of ageing.

Fig. 2 |. Select machine learning concepts important in the field of omics ageing clocks.

a | Basic concept of an ageing clock illustrated for a simple linear regression model. Population sampling is used to learn a relationship between a molecular feature (such as the expression level of a protein) and a dependent variable (age) that minimizes a cost function (graph). The learned relationship is then used to predict age, and the residual between chronological and predicted age is used as a measure of biological age (output model). b | The curse of dimensionality is a challenge for omics machine learning. The number of samples required to sample a distribution at a given density increases exponentially with the number of features measured in each sample. It is effectively impossible to densely sample high-dimensional omics distributions, which motivates the use of additional methods to reduce the feature space. c | The general architecture of a simple deep neural network. Features are taken as inputs and passed to a set of nodes (hidden layer 1), which transform the inputs with a mathematical function (typically a linear combination with a set of learned weights) and then pass the values to the next layer. The model gains additional expressive power by chaining together many simple functions with learnable weights over multiple hidden layers. The weights for each node can be jointly optimized by minimizing a cost function similar to the linear regression case.

Chronological age predictors, which the field has colloquially termed ageing clocks43,44, are one framework to interpret omics data in the context of ageing and has shown considerable promise45. Ageing clocks are machine learning models that learn patterns in molecular features in large numbers of samples, such as CpG methylation levels at specific genomic sites in blood cells or protein concentrations in plasma, which can be used to estimate the age of the sample source (FIG. 2). It has been widely hypothesized that this estimated age can serve as a measure of an individual’s biological age, and that the difference between estimated and actual chronological age, called ‘Δ age’ or ‘age gap’, reflects variation in their past rate of ageing43,44 (FIG. 2). These hypotheses have been supported by observations that individuals with positive age gaps, termed age acceleration, are at greater risk of mortality and some diseases of ageing such as heart disease, metabolic syndrome and certain cancers46–50.

In this Review, we critically examine the current state of research into ageing clocks built using omics data. Along the way, we attempt to clarify what ageing clocks can actually measure, how to improve ageing clocks to advance our understanding of ageing biology, and reflect on promising areas of future research in biomarkers of ageing enabled by omics technologies.

Omic clocks

Ageing clocks have been built from many different types of omics data using a variety of machine learning models (BOX 1 and FIG. 2). Each omics layer has certain intrinsic advantages and disadvantages for measuring different aspects of ageing. Here, we survey the major developments in the field thus far (FIG. 3), with particular attention to what phenotypes, and thus what ageing biology, age gaps from different omics layers have been able to accurately measure.

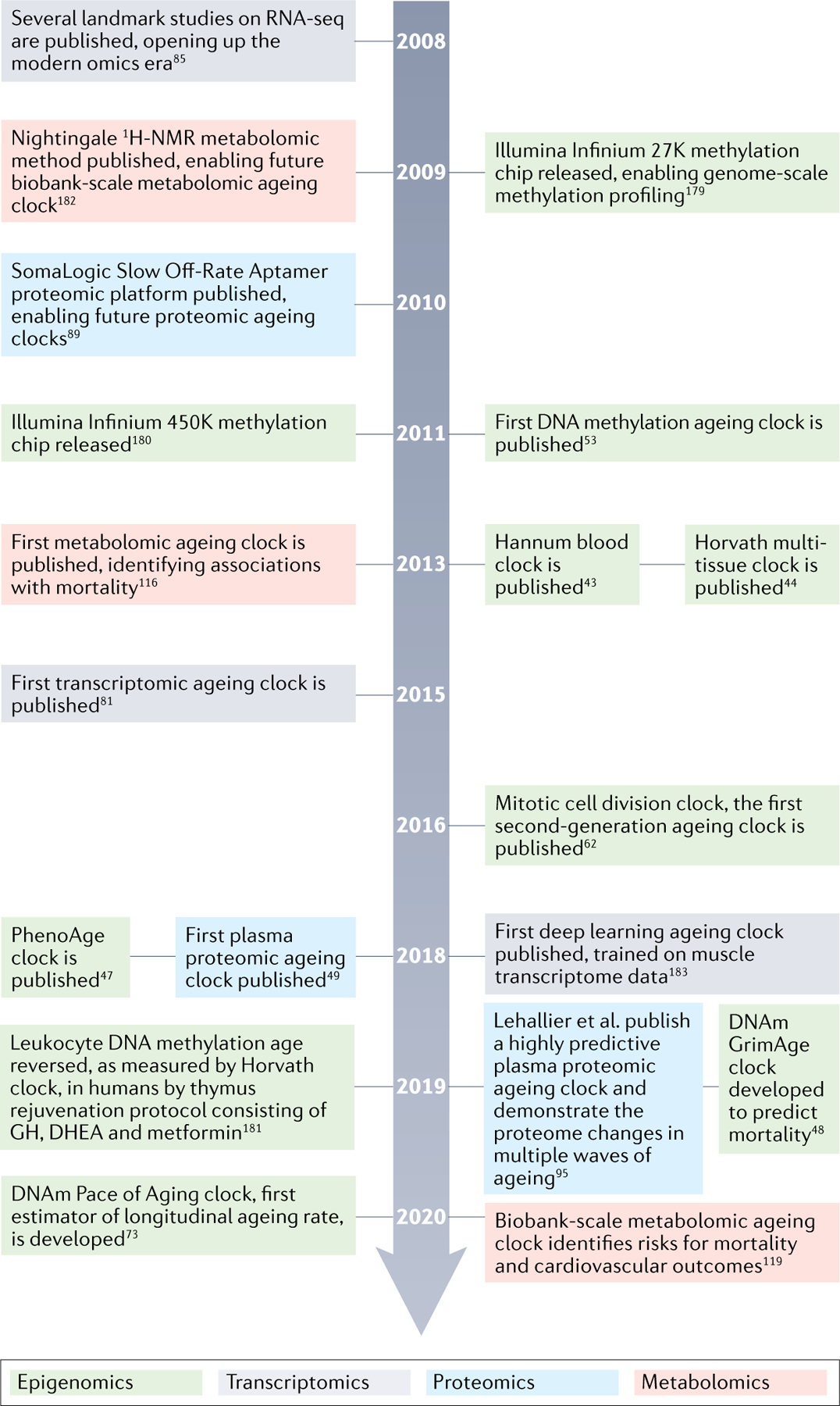

Fig. 3 |. Timeline of major advances and studies in ageing clocks research between 2008 and 2021.

Timeline of enabling technologies for omics ageing clocks and select studies that have moved the field forward between 2008 and 2021. Notably, this is not a complete list of important studies or technologies. Timeline refers to publication dates according to PubMed43,44,47–49,53,62,73,81,85,89,95,116,119,179–183. GH, growth hormone; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DNAm, DNA methylation; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing.

DNA methylation

Epigenetic alteration is a hallmark of ageing4, and recent studies have demonstrated cellular and functional rejuvenation by transient epigenetic reprogramming17,51,52. The field has largely focused on a particular epigenetic mark: cytosine methylation in CpG dinucleotides (CpG methylation), which changes with age. The first DNA methylation clock was an elastic net model (BOX 1) built in 2011 by Bocklandt et al.53, who demonstrated highly accurate chronological age prediction (within ~5 years) using only about 100 saliva samples. In 2013, this concept of the ‘epigenetic ageing clock’ was explicitly termed and popularized, first by Hannum et al.43, who built the Hannum clock (71-CpG clock) using 656 whole-blood samples, and then further by Horvath44, who built the pan-tissue Horvath clock (353-CpG clock) using 8,000 samples encompassing 51 different tissue and cell types. Since these landmark studies in 2013, several other epigenetic clocks have been built, including those by Weidner et al.54 (3-CpG clock), Lin et al.55 (99-CpG clock) and Vidal-Bralo et al.56 (8-CpG clock). All these clocks, as well as the majority of clocks discussed in future sections, were built using sparse linear regression methods which have become the standard in the field for interpretable models (BOX 1).

One especially interesting aspect of DNA methylation clocks is their ability to accurately predict age across a wide range of different tissue types, regardless of the tissue type they were trained on, suggesting that they measure ageing signals that are shared between cell types43,44. Moreover, across many cancers and in multiple cohorts, cancer tissues showed marked age acceleration on the Horvath clock44,57, suggesting it measures epigenetic dysregulation that is shared between ageing and many cancers.

However, mortality risk, which is widely used as a measure of ‘global’ biological age, has shown an overall weak and variable association with these clocks46,58, which raises questions as to what biology they actually measure. One known confounder is blood cell composition, which also changes with age and impairs health59. However, attempts to both remove and exploit the confounding by cell composition changes have not altered the weak associations with mortality and other health outcomes60.

Considering the methods from first principles, it is not obvious that naively selecting CpG sites that change the most with chronological age out of the many hundreds of thousands (methylation array) to millions (bisulfite sequencing) of possible sites measured would best capture the relevant functional ageing biology. In support of this notion, a large meta-analysis in 14 cohorts demonstrated that, taken to the extreme, improving a methylation clock’s accuracy to extremely high levels actually reduced its associations with mortality risk61. It seems possible to ‘overfit’ these models on molecular ageing ‘noise’ that is unrelated to ageing phenotypes, suggesting that training on chronological age alone may be a suboptimal approach.

These limitations have led to the development of second-generation epigenetic clocks that aim to identify more functionally relevant molecular changes in ageing by developing methods to link model training more directly with important features of biological ageing. In 2016, Yang et al.62 built an epigenetic clock associated with the number of cell divisions by pre-selecting CpG sites that had low levels of methylation in fetal tissue and increased methylation levels throughout adulthood and that mapped to Polycomb group target (PCGT) promoters, before training a sparse linear model. The authors used prior biological knowledge that hypermethylation of PCGT complex promoters is associated with stem cell proliferation63 to build a clock focused on just this aspect of ageing biology. Strikingly, this clock uniquely detected precancerous tissue samples to be age accelerated.

The field also developed a series of second-generation clocks specifically designed to associate with mortality risk47,48,50. Zhang et al.50 used LASSO Cox regression to identify 10 CpG sites that were highly correlated with mortality risk. Levine et al.47 built the DNAm PhenoAge clock, which uses standard methods but predicts a composite biological age score31 based on a linear combination of chronological age and nine clinical parameters associated with mortality risk. Lu et al.48 built the DNAm GrimAge clock, which predicts biological age in a two-stage process by first building models to predict smoking pack-years and the concentrations of seven plasma proteins with known associations with mortality risk and then combining the outputs of these models into a clock to predict time to death. By design, all these clocks have robust associations with mortality risk, and some show associations with heart disease risk, physical functioning (balance, grip strength, walking speed) and several blood chemistry markers of health. The DNAm GrimAge clock shows consistently stronger associations with various measures of age-related dysfunction, including heart disease, frailty, and cognitive and physical decline, compared to other clocks47,48,50,64–72.

More recently, Belsky et al.73 built the DunedinPoAm DNAm clock, an exciting development that, unlike many previous clocks that were trained to predict an individual’s current ageing state from cross-sectional data, was trained to more directly predict an individual’s ageing rate using longitudinal data. The study utilized a 1-year birth cohort (n = 810) that tracked changes in 18 clinical chemistry and physiological biomarkers of organ function collected at ages 26, 32 and 38 years to quantify a composite rate of biological ageing74. The DunedinPoAm DNAm clock was then trained with standard methods to estimate this rate with CpG methylation. This clock had stronger, more significant associations with age-related phenotypes, including physical functioning, cognition, self-rated health and mortality, than the DNAm PhenoAge clock.

The rate of innovation in the epigenetic clock field is promising, and the ability to use epigenetic blood ageing as a proxy for the physiological ageing of other organ systems highlights their potential use as clinical biomarkers. However, as tissues age at different rates41,42,75,76, there is likely a limit to how well ageing of blood cells can measure and explain mechanisms of ageing of the rest of the body; perhaps this is evidenced by the small (albeit statistically significant) associations between second-generation ageing clocks and organ-specific measures of age-related dysfunction. This idea is further supported by studies that show that epigenetic clocks trained in specific tissues have stronger associations with the functional states of those tissues77–80. Additionally, while epigenetic clocks have been shown to be highly reproducible, the general lack of understanding of the molecular and cellular causes and consequences of genomic CpG methylation remains a barrier to realizing the potential of these models.

Transcriptomics

Using RNA gene expression levels to develop ageing clocks links ageing more directly to genes, increasing both the interpretability and experimental testability of these models. The first major attempt at a transcriptomic clock came from a 2015 study by Peters et al.81, who used standard methods to train a transcriptomic ageing clock using peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression data from multiple large cohorts. The transcriptomic clock had highly variable age prediction accuracy across cohorts and was significantly less accurate in chronological age prediction than epigenetic clocks in all tested cohorts. This is perhaps in part because microarray and sequencing data from multiple platforms were used jointly, adding technical noise to the data. However, the transcriptomic clock was found to have associations with some biomarkers and risk factors, including smoking status, and a unique association with systolic blood pressure that was not detected by the Horvath and Hannum clocks. Although noisy, this may suggest the potential added value of using different clocks to measure different aspects of biological ageing.

In 2018, Fleischer et al.82 derived a clock using human dermal fibroblast transcriptomic data. This study used an ensemble method to combine multiple linear discriminant analysis classifiers to reduce the noisiness of transcriptomic data. The method outperformed standard penalized linear regression-based clocks at chronological age prediction and uniquely detected accelerated ageing in progeria samples, suggesting that methods designed to be robust to transcriptional noise improve performance. However, the model was not evaluated on an independent test dataset, so it remains to be seen whether the method was a true improvement.

An intriguing advance came in 2021 from Meyer et al.83, who demonstrated that a simple binarization and relative age scaling of transcriptomic data denoised the data and improved age prediction in Caenorhabditis elegans to the theoretical upper limit of accuracy (as accurately as the ages of the worms were tracked in increments of 1 day). Moreover, this clock could detect expected changes in biological age for long-lived daf2 mutants as well as irradiation and caloric restriction and performed well on diverse lifespan-affecting treatments in independent datasets. The authors showed that, in C. elegans, it is indeed possible to generate an accurate and biologically meaningful transcriptomic ageing clock. Additionally, they demonstrated, using human fibroblast data from Fleischer et al.82, that an elastic net-based clock derived from binarized transcriptomic data improved chronological age prediction to an r2 of 0.92 and mean error of 6.63 years and could detect accelerated ageing in progeria samples. However, it remains to be seen whether these methods can produce models that generalize well across human cohorts.

Holzscheck et al.84 used an alternative modelling framework that is growing in popularity owing to strong performance in other domains: deep neural networks (BOX 1). They implemented an artificial neural network that restricts neuron inputs and connectivity to known biological pathways. This enabled the researchers to extract an importance score for each pathway represented in the clock, increasing the interpretability of what is otherwise a black-box model. They reported that their clock was associated with multiple measures of biological skin ageing and that their model responded in expected ways to known perturbations of biological age in silico.

Although the field of transcriptomic clocks has developed several methods to overcome noise in transcriptomic data, it is still unclear how accurate and reproducible these clocks can be in large human cohorts. Most studies have been conducted on small sample sizes and not tested on independent cohorts, or used older microarray technology, which is less accurate and reproducible than modern RNA sequencing85,86. Moreover, their ability to reproducibly measure various aspects of biological ageing in humans, such as mortality risk, heart disease, physical functioning and cognition, largely remains to be determined.

Proteomics

Major developments in mass spectrometry-based, antibody-based and aptamer-based proteomics over the past decade have enabled the robust quantification of thousands of proteins in single samples87–90. Studies using multiple proteomic technologies have shown that thousands of proteins change with age in human plasma91–93 and cerebrospinal fluid94, which has recently led to the development of multiple proteomic ageing clocks. Pioneering studies by Baird et al.94 and Menni et al.91 developed the first ageing clock models based on the SomaLogic aptamer-based proteomic platform using human cerebrospinal fluid and plasma samples, respectively, although associations with any ageing phenotypes or organ function were not examined.

In 2018, Tanaka et al.49 described the first plasma protein-based ageing clock, which investigated the relationship between proteomic age gap and biological ageing. Lehallier et al.95 further demonstrated robust and highly accurate chronological age prediction across multiple independent cohorts. Both studies built proteomic clocks with standard methods and observed associations with many physiological and clinical ageing phenotypes, including physical functioning, cognitive test scores and clinical chemistry markers of health. In a follow-up study, Tanaka et al. showed associations with mortality, multi-morbidity, healthspan and lifespan96. These studies implicated immune and neuronal pathways as important ageing processes. Lehallier et al. also demonstrated that many proteins in the plasma ageing clock were modulated by parabiosis in mice and exercise in humans97, two rejuvenation paradigms.

Follow-up studies have shown that dozens of proteins identified in plasma proteomic ageing clocks directly regulate lifespan, and hundreds have biological connections to the health status of different organs98,99. Indeed, the direct links to organ function represent a considerable advantage of plasma proteomics to investigate how ageing may differ across tissues and cell types. Blood plasma contains proteins from nearly all organs and cell types, making it feasible to develop clocks focused on the ageing biology of specific tissues. Additionally, loss of proteostasis is a hallmark of ageing4,100, and other hallmarks of ageing, such as dysregulated nutrient sensing, altered intercellular communication and cellular senescence, also imply alterations in the proteome such as differential levels of insulin and peptide hormones, signalling proteins, and inflammatory cytokines. These direct mechanistic connections to ageing biology make proteomics a particularly good platform for the development of biologically interpretable ageing clocks.

Despite many theoretical advantages of plasma proteomics for ageing biomarker discovery, there remain limitations. Kidney function has an effect on plasma protein concentrations that is not fully understood but can confound ageing analysis101,102. Indeed, the function of many organs likely has an impact on plasma proteome composition — this can be a useful feature but needs to be considered for analysis. Additionally, proteomic technologies are newer and less developed than DNA quantification technologies and therefore proteomic clocks have been less extensively validated than methylation clocks. Although the SomaLogic aptamer-based platform is especially powerful and can reliably quantify over 7,000 proteins in a variety of biofluids and cellular extracts103–106, it is not yet possible to reliably quantify the entire proteome. Additional and larger studies of proteomic ageing will likely lead to more insights as proteomic technologies progress.

Similar to DNA methylation and transcriptomic clocks, it is not clear to what extent changes in the proteome represent all ageing processes across the body, although there is more evidence in proteomics to be optimistic than in other omics layers. Studies on heterochronic parabiosis and plasma exchange in animals have demonstrated that circulating proteins can have a causal influence on ageing phenotypes across the body, including in skeletal muscle107,108, heart109 and brain15,110–112. Future experimental studies on proteins identified by ageing clocks will be valuable for a deeper understanding of the biology of ageing and how it relates to omics signatures of ageing.

Metabolomics

State-of-the-art mass spectrometry and NMR methods can identify hundreds to thousands of metabolites in human plasma, and multiple studies have attempted to understand how they interact with ageing113–116. A large-scale biobank study used 1H-NMR of blood plasma to identify metabolites predictive of mortality risk in an Estonian and Finnish cohort117,118. The authors identified well-studied metabolites, such as albumin, very low-density lipoprotein particles and amino acids, that were associated with mortality due to multiple causes. Another large 1H-NMR biobank study subsequently developed a metabolomic clock from 56 reliably measurable metabolites in plasma and evaluated relationships between the metabolomic age gap, cardiovascular phenotypes and mortality119. In independent prospective cohorts, accelerated metabolomic age was found to be associated with cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease risk and all-cause mortality risk.

Additional studies have used multiple targeted and untargeted mass spectrometry and NMR methods to generate metabolomic clocks from plasma and urine metabolites120,121. These clocks were tested for associations with disease risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, smoking, alcohol use, physical inactivity), income and psychological risk factors (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder). Metabolomic age acceleration correlated with triglyceride levels, obesity, heavy drinking, diabetes mellitus, depressive symptoms, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Robinson et al.120 additionally assessed mass spectrometry metabolomic ageing clocks for the enrichment of biological pathways and identified enrichments for the metabolism of several vitamins, amino acids and xenobiotics.

The low cost of NMR-based metabolomics has enabled the quantification of biobank-scale cohorts and is a particularly exciting advantage for the application of metabolomic clocks to population health. However, performing and interpreting metabolomic experiments remains challenging. Untargeted metabolomics methods have the advantage of being able to detect many thousands of metabolite features; however, most compounds detected via mass spectrometry and NMR are orphan compounds, that is, their structure has not been identified122–124. Sensitivity is another challenge in untargeted methods, and many metabolites are detected in some but not other samples122–124, which limits the utility of many analytes for modelling. Targeted methods have better sensitivity but are limited by predefining a set of metabolites to look for in the experiment, greatly reducing the number of features detected and precluding the discovery of new metabolites122–124. In both targeted and untargeted methods, even for confidently identified compounds, the biological processes that generated them are often poorly understood122–125. Furthermore, metabolomic clocks have demonstrated lower age prediction accuracy than other omics data types despite training on extremely large sample sizes, and effect sizes for ageing traits have been modest113,116–121. Noise in metabolomic data may thus limit their current utility for ageing research.

Despite these challenges, the strong links between metabolism and ageing126 provide justification for further pursuing metabolomic clocks. Similar to plasma proteomics, plasma and urine metabolomics also carry information from multiple tissues across the body, increasing the potential ageing information of metabolomics relative to methylation and transcriptomic clocks of blood cells.

Other omics

Additional emerging technologies have begun to enable the construction of ageing clocks from glycans, microbiome composition and chromatin states, to name a few. While these data types have been less thoroughly explored, they are an exciting area for future research.

Glycomics.

Glycans are a large and diverse class of biomolecules that play essential roles in metabolism, cell signalling, protein and RNA function, and as structural components of many niches in the body127. Globally identifying and quantifying the various glycan structures in the body remains extremely challenging but there is evidence for broad changes in the glycome with age128, suggesting that alterations in the glycome could be an underappreciated player in ageing processes. Although it is not yet possible to comprehensively survey the glycome, recent mass spectrometry studies examining the concentrations of just a few well-studied glycans have been able to accurately predict chronological age and ageing phenotypes. Krištić et al.129 observed changes in the N-glycosylation pattern of serum IgG protein, which predicted age in multiple European cohorts. Moreover, IgG glycan age correlated with clinical markers of metabolic health129. IgG N-glycosylation has been further associated with metabolic indicators of health, including insulin levels, body mass index, triglyceride levels and type 2 diabetes mellitus, in additional studies. Merleev et al.130 used mass spectrometry methods to examine the concentration of 159 glycans on 17 common glycoproteins in plasma, which also showed promise as an ageing clock, although results were not validated in an independent cohort nor associated with any ageing phenotypes.

Microbiome composition.

Studies in the past decade have demonstrated that gut microbiome composition changes with age, that exceptionally long-lived individuals have a different microbiome composition from average older adults131–133, and that certain microorganisms131,134,135 and the metabolites they produce132,134,136 are beneficial to human health. Despite the strong links to health and longevity, it has been challenging to build microbiome-based ageing clocks. Galkin et al.137 predicted chronological age from gut microbiome taxonomic composition using deep neural network models. Their clock had similar accuracy and variance to clocks trained on other omics modalities, and in a separate cohort, the microbiome clock predicted individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus to be significantly older. They also observed that the abundance of certain well-studied beneficial microorganisms, such as Akkermansia muciniphila, had a larger impact on the model age predictions than the majority of other microorganisms detected.

Chromatin marks and chromatin state.

While CpG methylation has been studied extensively, other epigenetic changes in chromatin structure, state or conformation with age have not been thoroughly profiled. This may, in large part, be due to the complexity and noise in bulk chromatin accessibility and chromatin conformation capture assays, which are strongly affected by cell composition differences between samples and other batch effects138–141. Nonetheless, changes in chromatin state have been strongly implicated in ageing by progeroid syndromes, which disrupt the nuclear lamina and its associated regulation of heterochromatin structure142,143. These changes have been hypothesized to be a significant driver of normal ageing, making this an interesting area for future research. Chromatin accessibility studies in ageing immune cells have demonstrated shifts in chromatin accessibility with age in CD8+ T cells144–147. Indeed, these shifts may contribute to changes in immune cell composition with age, leading to a loss of naive T cells and transcriptional shifts towards more differentiated and dysfunctional cell states. Advances in chromatin accessibility assays should enable future studies in bulk samples, purified cell populations and single cells, which will shed additional light on the role of the chromatin state in ageing.

The link between CpG methylation and chromatin state is particularly underexplored in the field of ageing clocks given the prominence of methylation clocks. Methylation levels in blood cells have been observed to correlate strongly with cell composition, which may be a result of changes in chromatin state with age148. Additionally, studies have suggested that alterations in CpG methylation status that selectively alter heterochromatin associations with the nuclear lamina could be a driver of ageing149,150. Multi-omic ageing clocks that can dissect this relationship further are an exciting area for future research.

Comparing different clocks

Given the ever-growing number of clocks built on diverse molecular data types with a multitude of machine learning models, it is becoming increasingly important for the field to understand how different clocks relate to each other to truly dissect the ageing signals they capture. There are few meta-analyses that compare biological age estimates between different clocks but the few comparisons that do exist show a general lack of concordance both within and across omics layers.

Despite all being modelled and trained on the chronological age of individuals, mostly from blood cells, age gaps from first-generation epigenetic clocks (Hannum, Horvath, Lin, Weidner, Vidal-Bralo) seem to only mildly correlate with each other (r = 0.1–0.5)69,151. This could be due to the large degree of technical noise in DNA methylation arrays152–154, which limits the robustness of applying these models across datasets. Supporting noise as a large factor in these models, a recent analysis showed that training first-generation methylation clocks on increasing sample sizes can increase the age prediction accuracy to virtually perfect, which in turn erases the associations between age gap and biological ageing61. This finding suggests that age gaps in these clocks are not strongly driven by biological ageing signals. Age gaps in second-generation mortality-optimized clocks (Zhang, PhenoAge, GrimAge) also correlate only mildly with each other69,151. However, they generally show more robust associations with physiological ageing and mortality across cohorts, and more work needs to be done to understand what specific features of ageing biology they capture.

When comparing different types of omics ageing clocks, again many clocks are unique. Peters et al.’s transcriptomic age gap correlated with different biological ageing measures to those of the Horvath and Hannum clocks81; Tanaka et al.’s plasma proteomic age gap had no correlation with the Horvath clock and low correlation with the GrimAge and PhenoAge clocks96; and Robinson et al.’s metabolomic age gap had no correlation with the Horvath, Hannum and PhenoAge clocks in the same cohort, yet there was some overlap in the correlation between age gap and phenotypes tested120. One multi-omics study wherein the authors built their own telomere, epigenetic, proteomic and metabolomics clocks within a single cohort found mild correlations between epigenetic and transcriptomic clock age gaps and between proteomic and metabolomic clock age gaps155. Interestingly, epigenetic age gaps showed no correlations with proteomic and metabolomic age gaps, emphasizing that different omics technologies may capture different ageing signals. In the future, assessing the biological mechanisms that drive the clocks will be paramount to evaluating their relative utility. Multi-omic ageing clocks incorporating multiple omics layers into composite models will also help to understand which molecular ageing signatures are shared between omics layers or carry distinct phenotypic information.

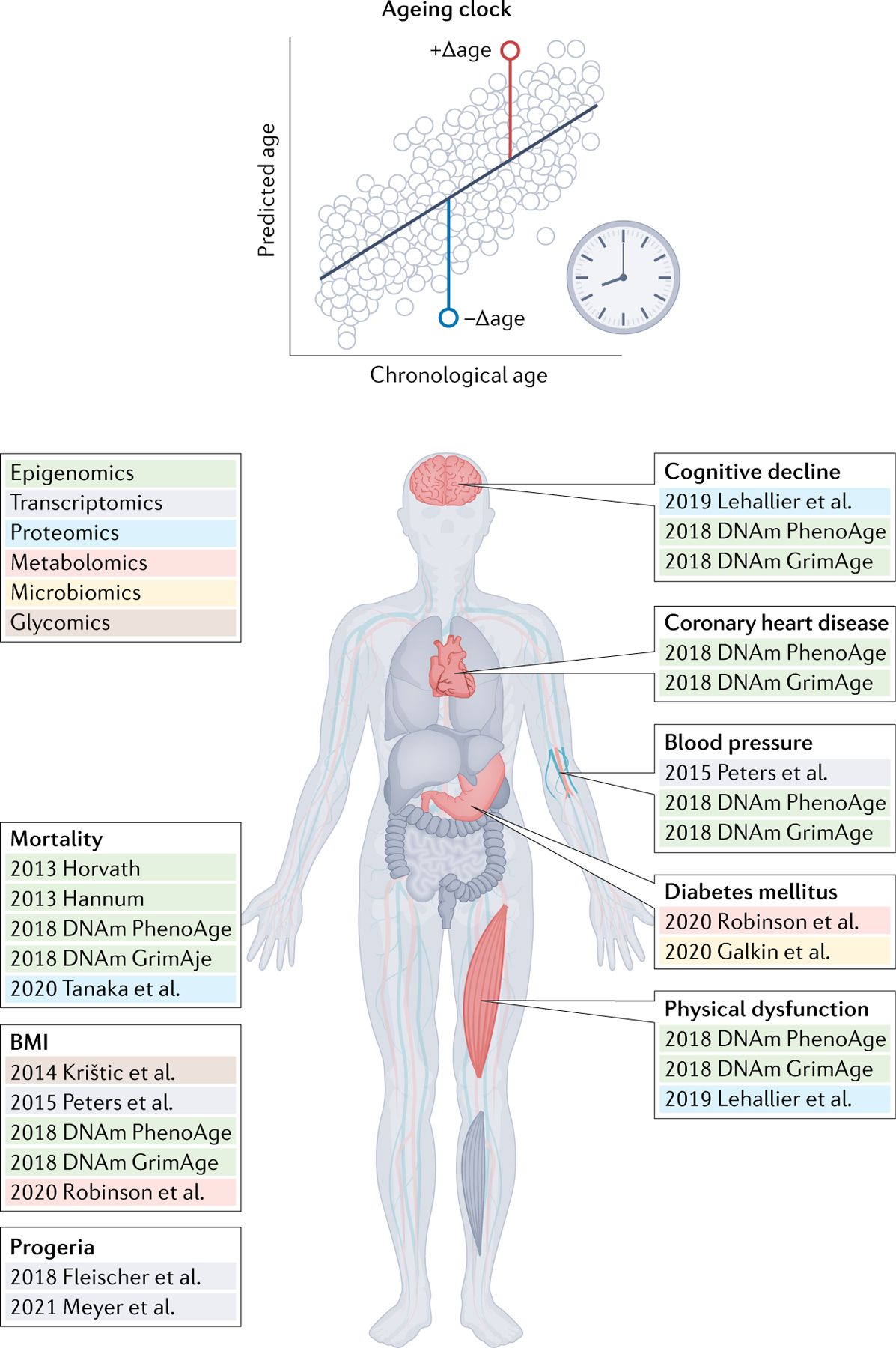

Overall, it is clear from the above studies that first-generation epigenetic clocks seem to capture signals mostly related to chronological time, whereas second-generation epigenetic clocks and other omics ageing clocks capture more physiologically relevant ageing signals. Still, the correlations between clocks based on different molecular features are fairly low, and differences are further emphasized by varying sensitivities to aspects of biological ageing (FIG. 4).

Fig. 4 |. Associations between clock age gaps and ageing phenotypes.

The age gap (top) is the primary measure of biological ageing for most ageing clocks. Age gaps for different ageing clocks have shown different sensitivities to various ageing phenotypes, suggesting they may measure different aspects of ageing biology to various extents. Methylation clocks are quite sensitive to mortality, whereas transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic clocks have shown increased sensitivity to disease-of-ageing phenotypes.

Future perspectives

Ageing clocks hold great promise to provide insight into the biological processes that underlie ageing as well as becoming potential clinical tools to guide the application of future treatments of ageing. To make progress on these fronts, we believe four concepts need to be further considered and refined. First, clocks need to be tailored to what they are meant to measure (for example, cellular, tissue, or organismal age and function); second, to obtain optimal clock performance and biological relevance, multiple molecular modalities and functional data may have to be used; third, we need progress in understanding to what degree clocks measure correlative or causative ageing processes; and fourth, the role of time and chronological age in modelling will have to be better understood.

Defining the application of ageing clocks

Most ageing clocks are developed with molecular features of blood and skin cells to then make estimates of the biological age of the entire organism. While this has often led to surprising insights into tissue and organismal function or mortality, clocks tailored to model specific cell or tissue functions may be more powerful in measuring ageing and revealing biology.

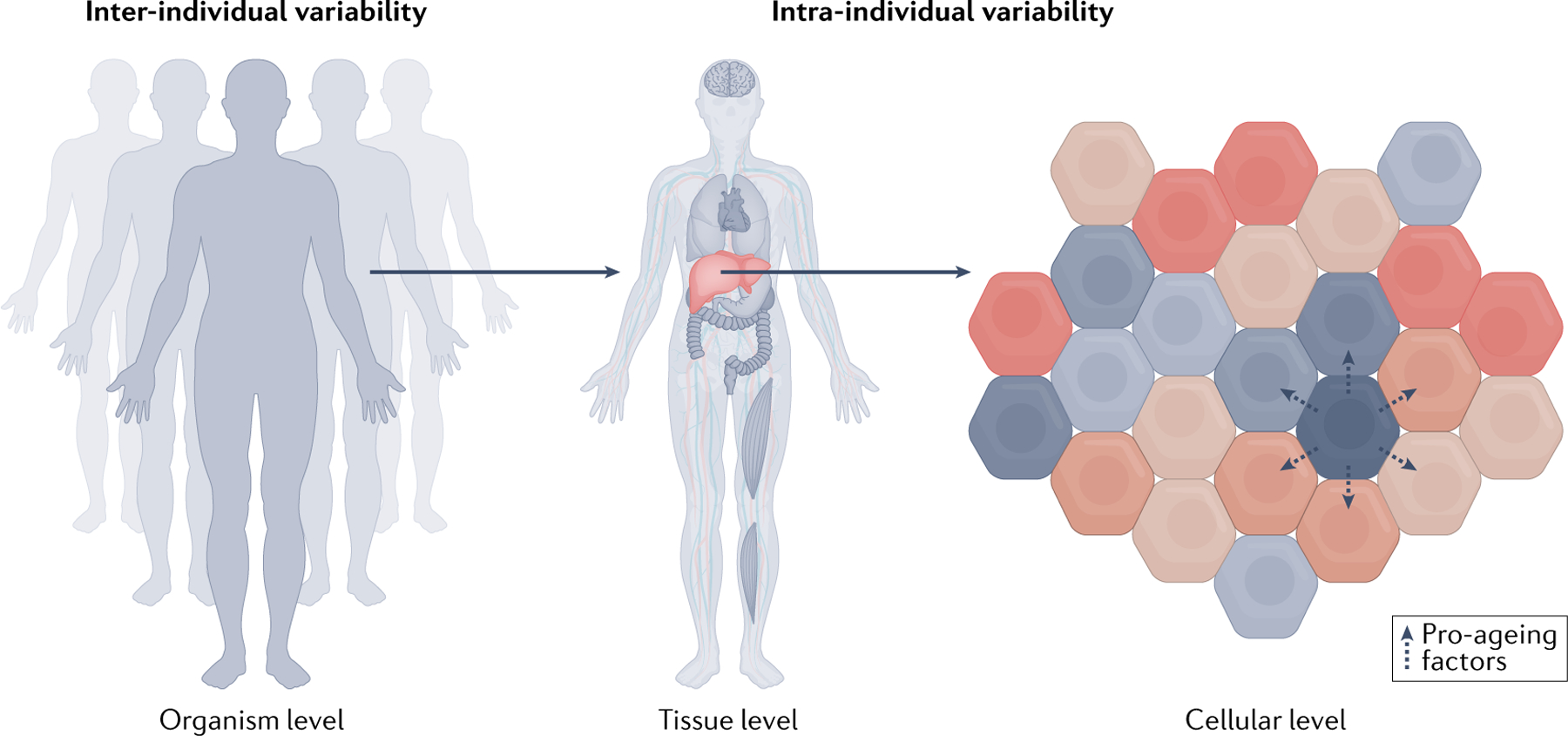

In this regard, it has become increasingly clear that there is considerable complexity and variation in ageing both between individuals and within a single individual (FIG. 5). A recent longitudinal multi-omics study in humans identified four population-level ageing pathways seen across individuals who were enriched for biological pathways related to liver, kidney, metabolic and immune dysfunction76. The authors also observed considerable individual deviation from population-level ageing trends and suggest the results imply individuals are ageing at different rates and through different mechanisms. Large mouse studies have observed that the transcriptomes of different organs and cell types have starkly different ageing trajectories41,42,156. Ultrastructural studies of human tissues157 have shown similar results, and even different human brain regions exhibit different gene expression trajectories with age158. At the cellular level, the study of cellular senescence has shown that some cells in a tissue age and senesce long before others, and their secreted factors may even spur the ageing of other cells locally or in other tissues through blood-mediated communication159. Together, these observations support the notion that ageing clocks need to be more targeted to harness the organismal complexity of ageing.

Fig. 5 |. Measuring ageing across the body.

Biological ageing varies between individuals (left) and across the body within a single individual (middle). Different tissues age at different rates and through different mechanisms. The heart, brain, immune or metabolic tissues may experience ageing to a greater or lesser degree in different individuals, who may then develop diseases of ageing afflicting these tissues in particular but have otherwise better function elsewhere in the body. Even within a single tissue, different cells age at different rates75 (right). Senescent cells are one example of a cellular ageing phenotype, which has an impact on different organs and cell types, such as macrophages, endothelia and glia, to varying extents and rates41,184–190. Aged cells may accelerate ageing of other cells through secretion of pro-ageing factors191,192, and certain cell types may be more susceptible to pro-ageing factors in their environment186,189,190.

Ideal molecular features to measure ageing

As ageing clocks based on different omics modalities do not typically agree and there are no clear ground-truth metrics of biological ageing to evaluate them by, it is too early to say which molecular category is likely to produce the best predictor of biological age and rate of ageing. Clearly, knowing the biological properties of individual features in a clock has an advantage in rationalizing the validity of ageing measurements and, in this regard, transcripts and proteins are likely the most useful and testable. Proteins have several additional advantages as they are most often the direct mediators of biological processes and form the vast majority of currently druggable targets in disease160. Additionally, they have shown great clinical utility and promise as prognostic biomarkers in many settings relevant to ageing, prominently in heart, kidney, liver, metabolic, inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease risk101,161,162. As such, proteins have been overwhelmingly favoured as clinical biomarkers compared with other molecular features such as chromatin marks and RNA transcripts. The primacy of disrupted proteostasis in neurodegenerative disease pathology additionally suggests that proteomic ageing clocks may offer unique insights into brain ageing100, for example.

Understanding correlation and causation

Ultimately, current ageing clocks are all correlative statistical models. They do not provide causal insights into ageing but can illuminate testable hypotheses and support or contradict other observations in molecular geroscience. However, even in correlation, we must be careful when evaluating ageing clocks because it is insufficient to merely assess how accurately they can predict chronological age. In fact, using chronological age as the only guide can be quite misleading as highlighted in the methylation clocks section. Therefore, we have chosen not to focus herein on chronological age prediction accuracy, and instead focus on assessing what biological ageing phenotypes of interest can be measured by age gaps from clocks.

To move beyond correlation, the field needs to make further progress in experimentally testing the molecular mechanisms underlying ageing clocks. For epigenetic clocks especially, very little is known about how alterations in clock CpG sites affect downstream changes in gene expression and age-related physiology. Emerging evidence in epigenetic reprogramming suggests that CpG methylation may play a causal role17,150; Lu et al.17 found that DNA methylation enzymes were required for epigenetic reprogramming of mouse retinal cells but much more work is needed. Here, transcriptomic and proteomic clocks have a potential advantage because they are more amenable to genetic screening methods and some causal paths are known. Modern human genetics methods, such as genetic colocalization163 and Mendelian randomization164, can also be used to test causality in ageing clock models. As quantitative trait loci studies of molecular traits and genome-wide association studies of ageing clocks165,166 in large cohorts become more robust, we expect the application of these methods to further elucidate the molecular gears that make the hands of ageing clocks tick.

Moving beyond chronological age

While many ageing clocks developed thus far have used only chronological age to train models, the field is increasingly moving beyond by incorporating additional, specific ageing phenotypes or ageing biology into feature selection and model training. This is most prominent with the success of second-generation methylation clocks, which have combined chronological age with a variety of biological features to improve their predictive power in specific contexts. The PhenoAge clock47 trained on a clinical chemistry panel of mortality risk factors and age. The GrimAge clock48 took a similar approach but trained methylation clocks directly on clinical protein markers and smoking pack-years, whose outputs were then combined into a Cox proportional hazards model with age and sex to predict mortality. Interestingly, both models trained estimators of plasma proteins and metabolites with known disease biology, again pointing to the plasma as fertile ground for future study. Yang et al.62 and Lu et al.167 took a different approach and trained clocks on cellular features — mitotic cell division and telomere length, respectively — to develop models with specific sensitivity for these aspects of cellular ageing.

A recent simulation study by Nelson et al.168 bolsters the rationale for training these composite models, showing that first-generation methylation ageing clocks do worse than random chance at identifying causal ageing loci due to cohort selection effects that occur in cross-sectional ageing cohorts169,170. Further, they show that causal ageing features tend to become less represented with increased age as unhealthy agers become less likely to be included in studies due to death or health challenges that preclude participation in research. However, methods that incorporate additional biological information on mortality, as in the PhenoAge clock approach, are able to correct for this effect and select causal loci with much greater frequency.

Modelling approaches that incorporate specific aspects of ageing biology either through purposeful feature selection or through the development of composite training metrics should help improve the interpretability of models and guide them to identify causal ageing features. A recent set of publications did this by profiling immune cell and inflammatory markers to develop an immune ageing clock that predicted mortality, cardiovascular outcomes and immunosenescence171,172. The authors used information from the clock to identify CXCL9 as a potential causal regulator of immune ageing and validated this result through functional follow-up in cellular models, which further supports the ability of these hybrid approaches to discover causal regulators of ageing.

Perhaps an even bolder approach to move closer to measuring ageing biology is to exclude chronological age in the training of clocks. In fact, chronological age is one of the largest sources of biological variability and, therefore, models that unbiasedly capture variation in the data will most likely capture ageing signals. This concept has been demonstrated by principal component analysis-based biological age estimators, which involve unsupervised dimensionality reduction to unbiasedly identify ageing signals, seemingly even better than clocks that train on chronological age173–175. Advanced machine learning models, such as neural networks, may be especially powerful tools for dimensionality reduction176 when it comes to discovering evolutionarily conserved ageing signatures from large datasets with depth and breadth in features, sample numbers and species. Indeed, it could be argued that, as much of the basic biology of ageing seems largely conserved among many species with very different lifespans3,4,8, clocks that measure a universal cause or rate of ageing should function ubiquitously. Further, because these models would no longer be encumbered by time, they may reveal novel principles to ageing biology undiscoverable using traditional clocks. Thus, maybe rather than ‘clocks’, which by definition measure time, these new models could instead be called ‘ageometers’.

Lastly, it is important to note that the vast majority of ageing clocks built so far are not trained on longitudinal data and do not directly predict future rates of ageing — a shortcoming that may limit their current clinical utility and explanatory power. Clocks designed to specifically estimate rates of ageing using longitudinal measurements are especially promising73, and this remains a heavily underexplored frontier.

Conclusions

The omics revolution has illuminated the sheer complexity of ageing biology by showing that many tens of thousands of molecular features change with age. Ageing clocks are an exciting frontier for leveraging the full breadth of omics data that has widened the scope of ageing biomarkers research by several orders of magnitude. The field has shown that it is possible to develop robust estimators of age from multiple kinds of omics data, which has prompted biological insights and raised hopes of developing precision diagnostics and surrogate end points to test the effectiveness of anti-ageing interventions.

Ageing clocks built from DNA methylation data, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics have all demonstrated a capacity to identify new biomarkers of biological ageing, and additional omics modalities are likely to do the same in the near future. Increasingly, cohorts are being profiled with multi-omics technologies, and future efforts to incorporate multi-omics into ageing clocks will further expand our knowledge of the molecular signatures of ageing and are likely to expand the predictive power of these models. Approaches to directly incorporate physiology and tissue function into ageing clock models have also proven fruitful, and expanding this approach is likely to yield more interpretable and actionable insights in the future.

Continued advances in machine learning tools will increase the sophistication with which we can identify relevant ageing signatures in omics data. Models that can tease apart more complex, non-linear ageing processes are an exciting area of future research. For example, Lehallier et al.95 demonstrated that plasma proteins change in three non-linear ‘waves’ of ageing; similarly, epigenetic and other molecular features in blood cells177 or skin178 change in distinct undulating patterns across the lifespan. Equally important, cells and tissues age at different rates and future clocks could benefit from honing in on what aspects of ageing they intend to measure: the overall, organismal age of an individual to predict, for example, mortality, or the age of the heart, lung or brain to gain deeper insight into specific diseases of ageing. Given the large disease burden of ageing, it is clear that ageing clocks will have an important role to play in advancing ageing science and personalized medicine.

Heterochronic parabiosis

An experimental paradigm where the circulatory systems of a young and old animal are surgically joined together.

Partial epigenetic reprogramming

Delivery of factors that can de-differentiate cells into induced pluripotent stem cells, typically short term, to de-age the epigenetic state of cells.

Biological age

The level of biological functioning of an organism, organ or cell as assessed in comparison to an expected level of function for a given chronological age.

Chronological age

The amount of time an organism has been alive for, typically measured in years for humans and tracked by birthdays.

Age gap

The difference between a biological age measurement and the expectation of that measurement for a given chronological age.

Overfit

When a machine learning model learns patterns that are actually the result of random noise in a dataset and which do not reflect the underlying distribution of the data.

LASSO

A ‘regularized’ linear regression algorithm that enforces an L1 norm penalty on regression parameters.

Linear discriminant analysis

A machine learning method used on categorical data that identifies linear hyperplanes in a dataset that can best split data into different groups, similar to the more commonly used logistic regression method.

r2

A metric that measures the amount of variance in the data that can be explained by a statistical model, ranging from cannot explain anything (r2 = 0) to perfect explanation (r2 = 1).

Black-box model

A model with parameters that cannot be easily interpreted or understood.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Stanford Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers (AG047366), the National Institute on Ageing (AG072255), the Milky Way Research Foundation, the Stanford Graduate Fellowship (H.O. and J.R.), and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (H.O.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

T.W.-C. is a co-founder and scientific adviser of Alkahest and Qinotto. T.W.-C., J.R. and H.O. are co-founders and scientific advisers of Teal Omics.

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Genetics thanks Luigi Ferrucci, Paolo Vineis, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Beard JR et al. The World report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 387, 2145–2154 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niccoli T & Partridge L Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr. Biol 22, R741–R752 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy BK et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell 159, 709–713 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M & Kroemer G The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013). This landmark review organized a framework to think about ageing through the lens of multiple conserved cellular and molecular processes and has become highly influential in the field of ageing research.

- 5.Partridge L, Deelen J & Slagboom PE Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature 561, 45–56 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijg J & Suh Y Genetics of longevity and aging. Annu. Rev. Med 56, 193–212 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helfand SL & Rogina B Genetics of aging in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Genet 37, 329–348 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh PP, Demmitt BA, Nath RD & Brunet A The genetics of aging: a vertebrate perspective. Cell 177, 200–220 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A & Tabtiang R A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 366, 461–464 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplanis J et al. Quantitative analysis of population-scale family trees with millions of relatives. Science 10.1126/science.aam9309 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Zenin A et al. Identification of 12 genetic loci associated with human healthspan. Commun. Biol 2, 41 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deelen J et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies multiple longevity genes. Nat. Commun 10, 3669 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan SS et al. A null mutation in SERPINE1 protects against biological aging in humans. Sci. Adv 10.1126/sciadv.aao1617 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Martin GM, Bergman A & Barzilai N Genetic determinants of human health span and life span: progress and new opportunities. PLoS Genet 3, e125 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villeda SA et al. Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat. Med 20, 659–663 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth GS et al. Biomarkers of caloric restriction may predict longevity in humans. Science 10.1126/science.1071851 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17. Lu Y et al. Reprogramming to recover youthful epigenetic information and restore vision. Nature 588, 124–129 (2020). This study experimentally demonstrated a direct link between alterations in DNA methylation in epigenetic injury response and regeneration, and a potential causal role for DNA demethylation enzymes in cellular ageing.

- 18.Rando TA & Chang HY Aging, rejuvenation, and epigenetic reprogramming: resetting the aging clock. Cell 148, 46–57 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu M et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med 24, 1246–1256 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baur JA et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature 444, 337–342 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Miguel Z et al. Exercise plasma boosts memory and dampens brain inflammation via clusterin. Nature 600, 494–499 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison DE et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 460, 392–395 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousefzadeh MJ et al. Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan. EBioMedicine 36, 18–28 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Jesus BB et al. Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. EMBO Mol. Med 4, 691–704 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anisimov VN Metformin: do we finally have an anti-aging drug? Cell Cycle 12, 3483–3489 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin-Montalvo A et al. Metformin improves healthspan and lifespan in mice. Nat. Commun 4, 2192 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alavez S, Vantipalli MC, Zucker DJS, Klang IM & Lithgow GJ Amyloid-binding compounds maintain protein homeostasis during ageing and extend lifespan. Nature 472, 226–229 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rebo J et al. A single heterochronic blood exchange reveals rapid inhibition of multiple tissues by old blood. Nat. Commun 7, 13363 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anstey KJ, Lord SR & Smith GA Measuring human functional age: a review of empirical findings. Exp. Aging Res 22, 245–266 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howlett SE, Rutenberg AD & Rockwood K The degree of frailty as a translational measure of health in aging. Nat. Aging 1, 651–665 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine ME Modeling the rate of senescence: can estimated biological age predict mortality more accurately than chronological age? J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 68, 667–674 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia X, Chen W, McDermott J & Han J-DJ Molecular and phenotypic biomarkers of aging. F1000Research 6, 860 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludwig FC & Smoke ME The measurement of biological age. Exp. Aging Res 6, 497–522 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen W et al. Three-dimensional human facial morphologies as robust aging markers. Cell Res 25, 574–587 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebastiani P et al. Biomarker signatures of aging. Aging Cell 16, 329–338 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima G, Iliffe S & Walters K Frailty index as a predictor of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 47, 193–200 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Comfort A Test-battery to measure ageing-rate in man. Lancet 294, 1411–1415 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baker GT & Sprott RL Biomarkers of aging. Exp. Gerontol 23, 223–239 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bobrov E et al. PhotoAgeClock: deep learning algorithms for development of non-invasive visual biomarkers of aging. Aging 10, 3249–3259 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders JL & Newman AB Telomere length in epidemiology: a biomarker of aging, age-related disease, both, or neither? Epidemiol. Rev 35, 112–131 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Almanzar N et al. A single-cell transcriptomic atlas characterizes ageing tissues in the mouse. Nature 583, 590–595 (2020). This study demonstrates that, in mice, different organs experience different patterns and rates of molecular and cellular ageing, which highlights the need for more sophisticated ageing clocks to account for intra-individual ageing variation.

- 42.Schaum N et al. Ageing hallmarks exhibit organ-specific temporal signatures. Nature 583, 596–602 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hannum G et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 49, 359–367 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Horvath S DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 14, 3156 (2013). This study comprehensively investigated CpG methylation ageing clocks across multiple human tissues and cell lines and discovered that there are some widely conserved methylation changes that occur throughout the body with ageing, which may be related to cancer and other diseases of ageing.

- 45.Galkin F et al. Biohorology and biomarkers of aging: current state-of-the-art, challenges and opportunities. Ageing Res. Rev 60, 101050 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen BH et al. DNA methylation-based measures of biological age: meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging 8, 1844–1865 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levine ME et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 10, 573–591 (2018). This study developed an innovative composite ageing score that incorporated chronological and biomarker measurements of age to train an improved second-generation DNA methylation ageing clock. The method has been influential in improving the performance and biological relevance of ageing clock models.

- 48.Lu AT et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 11, 303–327 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka T et al. Plasma proteomic signature of age in healthy humans. Aging Cell 17, e12799 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y et al. DNA methylation signatures in peripheral blood strongly predict all-cause mortality. Nat. Commun 8, 14617 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ocampo A et al. In vivo amelioration of age-associated hallmarks by partial reprogramming. Cell 167, 1719–1733.e12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkar TJ et al. Transient non-integrative expression of nuclear reprogramming factors promotes multifaceted amelioration of aging in human cells. Nat. Commun 11, 1545 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bocklandt S et al. Epigenetic predictor of age. PLoS One 6, e14821 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weidner CI et al. Aging of blood can be tracked by DNA methylation changes at just three CpG sites. Genome Biol 15, R24 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin Q et al. DNA methylation levels at individual age-associated CpG sites can be indicative for life expectancy. Aging 8, 394–401 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vidal-Bralo L, Lopez-Golan Y & Gonzalez A Simplified assay for epigenetic age estimation in whole blood of adults. Front. Genet 7, 126 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perna L et al. Epigenetic age acceleration predicts cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in a German case cohort. Clin. Epigenetics 8, 64 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fransquet PD, Wrigglesworth J, Woods RL, Ernst ME & Ryan J The epigenetic clock as a predictor of disease and mortality risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Epigenetics 11, 62 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fagnoni FF et al. Shortage of circulating naive CD8+ T cells provides new insights on immunodeficiency in aging. Blood 95, 2860–2868 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horvath S et al. Decreased epigenetic age of PBMCs from Italian semi-supercentenarians and their offspring. Aging 7, 1159–1170 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang Q et al. Improved precision of epigenetic clock estimates across tissues and its implication for biological ageing. Genome Med 11, 54 (2019). This study demonstrates an important paradox in the training of first-generation ageing clocks: increasingly perfect prediction of chronological age by a clock trained only on chronological age reduces its ability to discover drivers of variation in biological ageing between people.

- 62.Yang Z et al. Correlation of an epigenetic mitotic clock with cancer risk. Genome Biol 17, 205 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beerman I et al. Proliferation-dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Stem Cell 12, 413–425 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verschoor CP et al. Epigenetic age is associated with baseline and 3-year change in frailty in the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. Clin. Epigenetics 13, 163 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maddock J et al. DNA methylation age and physical and cognitive aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 75, 504–511 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sibbett RA et al. DNA methylation-based measures of accelerated biological ageing and the risk of dementia in the oldest-old: a study of the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921. BMC Psychiatry 20, 91 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuo P-L, Moore AZ, Lin FR & Ferrucci L Epigenetic age acceleration and hearing: observations from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Front. Aging Neurosci 13, 790926 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCrory C et al. GrimAge outperforms other epigenetic clocks in the prediction of age-related clinical phenotypes and all-cause mortality. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 76, 741–749 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crimmins EM, Thyagarajan B, Levine ME, Weir DR & Faul J Associations of age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education with 13 epigenetic clocks in a nationally representative U.S. sample: the health and retirement study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 76, 1117–1123 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hillary RF et al. An epigenetic predictor of death captures multi-modal measures of brain health. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 3806–3816 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joyce BT et al. Epigenetic age acceleration reflects long-term cardiovascular health. Circ. Res 129, 770–781 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shiau S et al. Epigenetic aging biomarkers associated with cognitive impairment in older African American adults with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Clin. Infect. Dis 73, 1982–1991 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Belsky DW et al. Quantification of the pace of biological aging in humans through a blood test, the DunedinPoAm DNA methylation algorithm. eLife 9, e54870 (2020). Here, the authors developed a DNA methylation clock surrogate for longitudinal health and biomarker measurements to more directly predict an individual’s ageing rate instead of relying on cross-sectional measures of relative biological age.

- 74.Belsky DW et al. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E4104–E4110 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rando TA & Wyss-Coray T Asynchronous, contagious and digital aging. Nat. Aging 1, 29–35 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahadi S et al. Personal aging markers and ageotypes revealed by deep longitudinal profiling. Nat. Med 26, 83–90 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levine ME, Lu AT, Bennett DA & Horvath S Epigenetic age of the pre-frontal cortex is associated with neuritic plaques, amyloid load, and Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive functioning. Aging 7, 1198–1211 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horvath S et al. Epigenetic clock for skin and blood cells applied to Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome and ex vivo studies. Aging 10, 1758–1775 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choukrallah M-A, Hoeng J, Peitsch MC & Martin F Lung transcriptomic clock predicts premature aging in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. BMC Genomics 21, 291 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sillanpää E et al. Blood and skeletal muscle ageing determined by epigenetic clocks and their associations with physical activity and functioning. Clin. Epigenetics 13, 110 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peters MJ et al. The transcriptional landscape of age in human peripheral blood. Nat. Commun 6, 8570 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fleischer JG et al. Predicting age from the transcriptome of human dermal fibroblasts. Genome Biol 19, 221 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Meyer DH & Schumacher B BiT age: a transcriptome-based aging clock near the theoretical limit of accuracy. Aging Cell 20, e13320 (2021). This study developed multiple methodological innovations for training accurate and reproducible transcriptomic ageing clocks, and developed clocks with striking generalizable performance across multiple ageing treatment conditions in worms.

- 84. Holzscheck N et al. Modeling transcriptomic age using knowledge-primed artificial neural networks. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis 7, 15 (2021). This study aimed to design a more transparent and biologically interpretable neural network ageing clock, showcasing some of the methods available to make inferences about ageing with these more complex models.

- 85.Wang Z, Gerstein M & Snyder M RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet 10, 57–63 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang W et al. Comparison of RNA-seq and microarray-based models for clinical endpoint prediction. Genome Biol 16, 133 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pappireddi N, Martin L & Wühr M A review on quantitative multiplexed proteomics. ChemBioChem 20, 1210–1224 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Suhre K, McCarthy MI & Schwenk JM Genetics meets proteomics: perspectives for large population-based studies. Nat. Rev. Genet 22, 19–37 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gold L et al. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS One 5, e15004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lundberg M, Eriksson A, Tran B, Assarsson E & Fredriksson S Homogeneous antibody-based proximity extension assays provide sensitive and specific detection of low-abundant proteins in human blood. Nucleic Acids Res 39, e102 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Menni C et al. Circulating proteomic signatures of chronological. Age. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 70, 809–816 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ignjatovic V et al. Age-related differences in plasma proteins: how plasma proteins change from neonates to adults. PLoS One 6, e17213 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lu J et al. Profiling plasma peptides for the identification of potential ageing biomarkers in Chinese Han adults. PLoS One 7, e39726 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baird GS et al. Age-dependent changes in the cerebrospinal fluid proteome by slow off-rate modified aptamer array. Am. J. Pathol 180, 446–456 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lehallier B et al. Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Nat. Med 25, 1843–1850 (2019). This study developed a highly predictive plasma proteomic ageing clock and showed relationships between the proteomic age gap and many ageing traits such as cognitive function and motor function. It also describes the non-linear patterns of proteomic ageing, which have implications for future ageing clock models.

- 96.Tanaka T et al. Plasma proteomic biomarker signature of age predicts health and life span. eLife 9, e61073 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lehallier B, Shokhirev MN, Wyss‐Coray T & Johnson AA Data mining of human plasma proteins generates a multitude of highly predictive aging clocks that reflect different aspects of aging. Aging Cell 19, e13256 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Johnson AA, Shokhirev MN, Wyss-Coray T & Lehallier B Systematic review and analysis of human proteomics aging studies unveils a novel proteomic aging clock and identifies key processes that change with age. Ageing Res. Rev 60, 101070 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Johnson AA, Shokhirev MN & Lehallier B The protein inputs of an ultra-predictive aging clock represent viable anti-aging drug targets. Ageing Res. Rev 70, 101404 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hipp MS, Kasturi P & Hartl FU The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 20, 421–435 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Williams SA et al. Plasma protein patterns as comprehensive indicators of health. Nat. Med 25, 1851–1857 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tryggvason K & Wartiovaara J How does the kidney filter plasma? Physiology 20, 96–101 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ferkingstad E et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet 53, 1712–1721 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Md Dom ZI et al. Effect of TNFα stimulation on expression of kidney risk inflammatory proteins in human umbilical vein endothelial cells cultured in hyperglycemia. Sci. Rep 11, 11133 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thanasupawat T et al. Slow off-rate modified aptamer (SOMAmer) proteomic analysis of patient-derived malignant glioma identifies distinct cellular proteomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci 22, 9566 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang C et al. Genomic atlas of the proteome from brain, CSF and plasma prioritizes proteins implicated in neurological disorders. Nat. Neurosci 24, 1302–1312 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Conboy IM et al. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433, 760–764 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sinha M et al. Restoring systemic GDF11 levels reverses age-related dysfunction in mouse skeletal muscle. Science 344, 649–652 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Loffredo FS et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 153, 828–839 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]