Abstract

Hybrid or recombinant protein-polymers, peptide-based biomaterials, and antibody-targeted therapeutics are widely explored for various ocular conditions and vision correction. They have been noted for their potential biocompatibility, potency, adaptability, and opportunities for sustained drug delivery. Unique to peptide and protein therapeutics, their production by cellular translation allows their precise modification through genetic engineering. To a greater extent than drug delivery to other systems, delivery to the eye can benefit from the combination of locally-targeted administration and protein-based specificity. Consequently, a range of delivery platforms and administration methods have been exploited to address the ocular delivery of peptide and protein biomaterials. This review discusses a sample of pre-clinical and clinical opportunities for peptide-based drug delivery to the eye.

Keywords: Ocular, Barriers, Elastin-like polypeptides, Protein, Antibody, Lacrimal gland, Vitreous, Cornea, Subconjunctiva

1. Introduction

1.1. Ocular biology and barriers

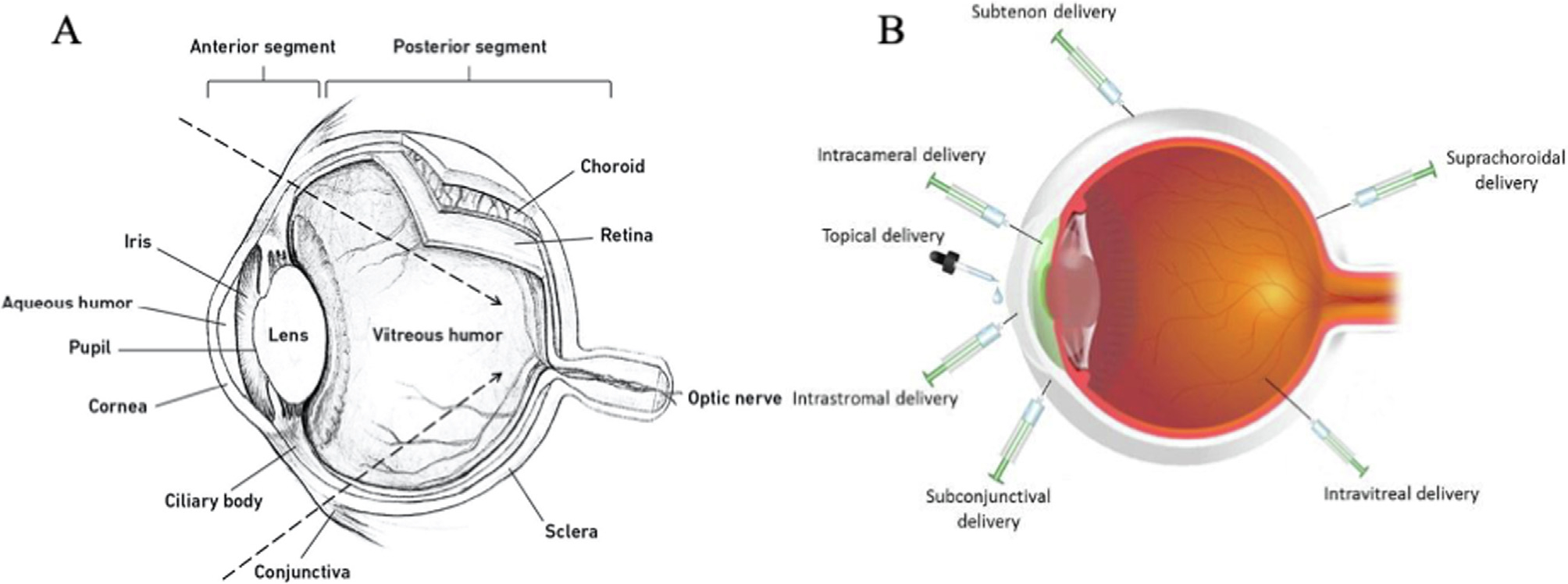

The eye is among the most multiplex sensory organs. It is composed of an intricate assembly of physiological and anatomical structures that connect, regulate, and coordinate visual function. The eye is broadly segmented into two portions: the anterior and posterior segments (Fig. 1A), which differ in their accessibility to peptide-based formulations. The anterior ocular segment is the front one-third, located between the cornea and lens. This comprises the iris, aqueous humor, pupil, lens, cornea, ciliary body, and conjunctiva. Meanwhile, the posterior segment or cavity, the grail-shaped portion, accounts for the back two-thirds of the eye. This starts behind the lens, extends to the optic nerve, and includes the sclera, choroid, retina, vitreous humor, and optic nerve [1–3]. This complex structure has multiple protective layers that act as barriers at a static, dynamic, and metabolic level to hinder harmful molecules and microorganisms. Although these barriers preserve the eye and maintain vision quality, they are a challenge to localized and effective therapeutic delivery to the eye [4,5].

Fig. 1.

A) Schematic of the ocular anatomy representing the anterior and posterior segments, adapted with permission from [1]. B) Emerging methods for ocular delivery, adapted with permission from [51].

Regarding the anterior segment, static barriers or boundaries include the cornea and blood-aqueous barrier. Additionally, there are dynamic barriers that impede drug penetration to the anterior chamber including the conjunctival lymphatic network, tear turnover, and nasolacrimal drainage [6,7]. Along with being the first defensive barrier against foreign substances from the environment, the cornea hinders the ocular diffusion of most drug molecules, which limits their bioavailability within many targets within the eye. The cornea consists of the following layers: i) epithelium; ii) Bowman’s membrane; iii) stroma; iv) Descemet’s membrane; and v) endothelium. Each layer possesses variable degrees of polarity that can affect drug transport. In particular, the epithelium and stroma represent the major barriers for trans-corneal diffusion and permeability. Corneal epithelium is the outermost layer, lipoidal in nature, and composed of 5–7 layers of packed cells. They have a network of tight junctions, which are located laterally between the cellular membranes of outermost, apical layer of epithelium. Characterized by scaffolding proteins, such as ZO-1, the tight junctions provide majority of resistance to paracellular transport across the cornea. Characterized by E. Cadherin, adherens junctions provide cell-to-cell linkage to intracellular actin filaments across most of the corneal epithelium. Desmosomes, form cell-to-cell attachments between the membranes of most epithelial cells. At the basolateral side of the corneal epithelium, gap junctions are characterized by connexin proteins, which promote cell-to-cell communication. These junctions provide anchoring functions and structural integrity that act as a diffusional barrier for uptake of hydrophilic drugs and large molecules such as proteins and many peptides [8–12]. Despite this, peptides have differential abilities to cross the corneal epithelium. For example, Guo and coworkers [13] explored the influence of the HIV-derived trans-acting transcriptional activator linked to a reporter enzyme (TAT-β-gal) on penetration through excised rat corneas. The group showed that the TAT fusion protein only reached the first or superficial layers of epithelium. In contrast, following corneal wounding, the protein penetrated the corneal epithelium and the next layer of stromal cells. Thus, they concluded that disruption of the outermost corneal epithelium may be a route to enhance corneal transport of macromolecules, such as proteins. In another study from Chen and collaborators [14], a hydrophilic peptide, CC12, was developed using phage-display to select for trans-scleral-retinal transport. In permeability studies across the rabbit cornea, this peptide enhanced the transport of an anti-angiogenic peptide called KV11. The corneal stroma is predominantly made up of water (78%) and collagenous protein (15%). This layer accounts for about 90% of the corneal mass. It is characterized by a gellike structure of hydrophilic nature that is a formidable challenge for lipophilic drugs [15]. The blood-aqueous humor barrier is an additional physical barrier of note, created by epithelial and endothelial cells. It separates distinct environments before and after the iris and restricts permeability based on the osmotic pressure and physio-chemical properties of drugs [16,17]. Liu and coworkers [18] conducted a proteomic analysis of the permeability profiles of 15N-labeled serum proteins as traces through the blood-aqueous barrier in C57B/6J mice. Mass spectrometry demonstrated that the injured eyes were permeable to more proteins than the healthy controls, suggesting less barrier restriction following injury. Overall, the group suggested that the distribution of specific proteins through the aqueous barrier is driven by time-dependent gradients, environmental homeostasis, and other transporter-related factors.

Along with the static barriers of the anterior segment, dynamic physiological barriers, such as lymphatic vessel drainage and lacrimation, also protect the eye from environmental stressors by modulating deposition, interaction, and absorption [16,17]. Due to their defensive role, these processes are barriers to drug absorption and accessibility to ocular tissues. Lymphatic vessels are unidirectional capillaries with inter-endothelial gaps and no tight junctions [19]. Immuno-histological studies have revealed their role in maintaining fluid homeostasis, aqueous humor drainage, immunosurveillance, and intraocular pressure, which consequently accelerates protein/peptide elimination [20–23]. Lee and coworkers [23] explored the transscleral delivery and elimination of a fluorescently-labeled IgG antibody following the subconjunctival administration using Long Evans female rats. The immunohistochemical visualization revealed that conjunctival circulation and lymphatics limited IgG outflow from the conjunctiva to retina. In addition to the interstitial flow towards the lymph, tear turnover and reflex blinking act as main impediments to topically-administered drugs. Once a topical dose is administered, the volume of the cul-de-sac increases, leading to blinking, tear production, and typical elimination of 95% of the dose. Aqueous production of tears, which includes most proteins and electrolytes, occurs in the superior and inferior lacrimal glands (LGs) located above the eye. These drain through ducts located beneath the eyelid, to the tear film on the side opposite to the nose. While most of the volume of the tear film is produced in the LG, the meibomian glands located along the superior and inferior eyelids produce most lipids in the tears, which reduce evaporative loss of tears. Blockage or dysfunction of these glands can lead to dry eyes, which reduces the rate of tear turnover; however, patients with epiphora can suffer from excessive tear production [24–27]. Nasolacrimal drainage is a conduit system of tear flow from the eye adjacent to the nose into the nasal passage. The tear drainage starts with puncta, upper and lower canaliculi, lacrimal sac, and ends in the nasal cavity [7,28]. Overcoming this obstacle, mucoadhesive formulations, hydrogels, hybrid approaches, surfactants, and viscous materials are potential enhancers of topical treatments with proteins [29–31].

On the other hand, topical treatment of the posterior segment is restricted by the barriers of the anterior segment as well as many other anatomical and physiological barriers to drug bioavailability. The back of the eye, which includes the retina, may often require treatment from systemic therapies or direct injection. Additional barriers in the posterior segment include static barriers, such as the sclera, Bruch’s membrane, and the limited permeability of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB). The posterior segment is also protected by dynamic barriers, which include phagocytosis of vitreous debris by retinal pigment epithelium, energy-dependent efflux pumps, choroidal blood flow, and lymphatic drainage. The sclera is a hydrated porous tissue of collagen and proteoglycan embedded in an extracellular matrix, which is covered by a thin episcleral layer. Permeability through sclera is determined by the characteristic parameters of the permeating molecules [32–34]. Wen and coworkers [35] investigated the influence of molecular structure and conformation on the scleral permeation and uptake of bevacizumab, ranibizumab, FITC-BSA, FITC-ficoll, and FITC-dextran. It was observed that the molecules with higher molecular weight showed lower diffusion and longer transport lag time, suggesting that the porous membrane of sclera has a size-exclusion effect. Compared to polysaccharides, the compact or less flexible structure of bevacizumab and ranibizumab was associated with lower uptake during the permeation process. Overcoming permeability barriers, ultrasound-guided drug delivery and Iontophoresis have promise [36–38]; however, their transport then depends on the surface charge of the drug molecules. Srikantha and coworkers [39] reported that negatively charged proteoglycan matrix binds to positively charged molecules during its intracellular transport, leading to altered diffusion. Bruch’s membrane, a highly vascularized barrier, separates the choroidal blood circulation from the retina and distinctly coordinates biomolecular exchange between these two layers, including metabolites, nutrients, and waste products. It is continuously renewed; however, its thickness increases with age. Increased thickness decreases the permeability of drug molecules, clearance of cellular debris, and secondary metabolic stressors, thus promoting age-related vision impairment [4,32,33,40]. The BRB is formed of retinal capillary endothelial cells and retinal pigment epithelial cells, which lie in the inner and outer region of the eye, respectively. These layers possess tight junctions, which represent a functional barrier for molecular permeability and bioavailability. In addition, they are equipped with influx and efflux transporters, which determine the pharmacokinetic profiles of administered drugs and thereby the pharmacological effect [41]. For example, P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an efflux transporter of adenosine triphosphate–binding cassette (ABC) subfamily, is expressed in both layers of BRB and represents one of the principal barriers to substrate penetration and disposition. Several studies ruled out the use of P-gp selective inhibitors to overcome the blood-ocular barriers by enhancing the P-gp substrate transport, which might possibly enhance treatment of retinal diseases [42,43]. Choroid lies external to BRB and internal to sclera and consists of a vascular endothelial, pigmented connective structure whose main function is to nourish the outer retina, modulate sclera growth, and regulate intraocular pressure by regulating lymphatic drainage [44–46]. Pitkänen and coworkers [47] used isolated RPE-choroid specimens from bovine eyes for studying permeability as a function of molecular size and lipophilicity. It was thought that the choroid is a rate-limiting obstacle for hydrophilic compounds and macromolecules. Addressing the kinetics of this barrier through pharmaceutical engineering studies might provide insight into limitations to ocular drug delivery. In addition, pigment-generating cells in RPE and choroid contain melanin, which further hinder permeability of some drugs. Melanin is a macromolecule with saturable binding capacity, through which drugs must pass on a journey to target ocular tissues [48]. Rimpelä and coworkers [49] explored the effect of melanin binding on intracellular delivery of five model drugs using in vitro models of pigmented retinal epithelial cells and non-pigmented cells. The group reported decreased unbound drug concentrations and considerable cellular uptake of melanin-binding drugs in pigmented cells, compared to non-pigmented cell lines. Melanin may act as a drug-binding reservoir, which remains a potential limitation to mass transfer. However, other factors might affect the drug transport past melanin, for example intracellular pH gradients.

On the other hand, proteolytic enzymes act as a challenging obstacle in the intraocular environment for protein or peptide delivery. For example, enzymes like peptidases, reductases, and esterases pose a metabolic challenge for peptides and proteins during their transport to the intended target, leading to poor bioavailability and undesirable metabolites, which may lead to side effects or toxicity [50,51]. Understanding the location of enzymatic activity within healthy or diseased tissues, the substrate specificity, and pharmacokinetic parameters is crucial for site-specific bioactivation [52,53]. For example, the esterase level at the corneal epithelium is 2.5x the esterase level at the stromal endothelium [54]. Thus, ester-prodrugs enable protective delivery of the parent protein, while boosting drug levels at the corneal epithelium. Alternatively, peptidases attack peptide substrates by removing the amino acid from the N-terminus. Overcoming proteolytic obstacles can be achieved by: i) N-terminal peptide acetylation; ii) peptides based on D-handed chiral amino acids; iii) cyclic peptides; and iv) encapsulation within a carrier [55–59]. Regardless of the promising insights of these structural modifications, engineering new biomaterials with optimal stability and intrinsic activity remains a major limitation to the ocular application of peptides [51].

To safely overcome the complexity of delivery to the eye remains a challenge. Consequently, numerous formulations and methods of administration have emerged for optimal and selective delivery to the anterior and posterior segments (Fig. 1B). Recombinant protein-polymers, peptide therapeutics, and antibodies are among the emerging strategies. In general, they have the potential to enhance performance, stability, specificity, and duration of therapy. Using these agents, many routes of administration have been explored, including topical, intralacrimal, intrastromal, subconjunctival, intravitreal, suprachoroidal, sub-tenon, and intracameral [51,60,61]. Topical administration, such as eye drops, is the most common, convenient, and preferred route to reach the anterior segment. However, more so than small molecule therapies, their rate of absorption and relative bioavailability is limited because of epithelial tight junctions, reflex blinking, nasolacrimal drainage, and tear turnover, which lead to sub-therapeutic effects. Overcoming these delivery limitations can in some cases be achieved through repeated administration at high doses [7]. One alternative is intralacrimal injection, which is performed under the upper eyelid and through the conjunctiva where clinicians directly visualize and inject the palpebral lobe of the LG. This has been highly effective to deliver formulations of botulinum toxin to reduce epiphora [24]. Subconjunctival delivery in the form of injection or implantation is an accessible, effective, and potentially less frequent way of delivering therapeutic molecules. This route of administration may be useful if the drug cannot penetrate the anterior segment via topical administration [62,63]. The intrastromal route is a highly selective and efficient method for treating infections that are poorly responsive to topical and subconjunctival administration [64,65]. Moreso than these other routes, intravitreal administration revolutionized the delivery of multiple therapeutics, many of which inhibit angiogenesis and are now the standard of care for wet macular degeneration. Intravitreal administration is relatively safe, overcomes both corneal as well as blood-retinal barriers, and offers prolonged therapeutic benefits. However, unlike topical or oral administration, the intravitreal procedure is moderately invasive, which causes patient discomfort and risks infectious complications [66–68]. Similarly, suprachoroidal delivery has demonstrated promise as a future method of administration. This method directly delivers therapeutic candidates into the suprachoroidal space, which lies between the sclera and external choroid tissue layers. This space fills a region of an approximate thickness of 30 μm, which can hold up to 200 μl of fluid per eye and is considered a reservoir for prolonged drug delivery. Suprachoroidal delivery has been enabled by transformative applications of needles with different dimensions. Suprachoroidal administration shows unique advantages, whereby it promotes sustained delivery, while maintaining intraocular pressure. It has been evaluated for delivering ophthalmic agents the posterior segment, where they can reach the retina, sclera, and choroid [69–72]. Tyagi and coworkers [73] performed a comparative study for delivering sodium fluorescein (NaF) into the choroid-retina region using suprachoroidal, intravitreal, and posterior subconjunctival injections. Compared with the subconjunctival and intravitreal injections, the histological analysis demonstrated that NaF delivered at the choroid-retina region by suprachoroidal administration showed 6 times and 4 times higher concentration, respectively. Suprachoroidal administration offers unique promise for overcoming challenges to ocular delivery in the posterior segment. Alternatively, the sub-tenon injection has been evaluated in transscleral delivery. It produces high relative bioavailability in the neighboring sclera. It is also a reasonably accessible and reliable route of administration, which allows faster drug diffusion, higher drug concentrations, slower clearance from the site, and minimal incidence of serious complications [66,74]. Intracameral administration targets the anterior chamber, which is routinely used for topical medications in managing the postoperative inflammation after cataract surgery. Shen et al. [75] evaluated the distribution of 14C-Latanoprost, a prostaglandin analogue, following a single intracameral dose and repeated topical administration into beagle dogs and cynomolgus monkeys. The intracameral dosing has demonstrated more selective penetration to intraocular tissues, while the topical dosing was limited by anatomical and precorneal barriers. Intracameral approach confers direct delivery, highly targeted drug concentrations, effective therapeutic activity, reduced systemic side effects, and patient compliance [76].

1.2. Recombinant protein-polymers and peptide therapeutics

Biopharmaceutical proteins and peptides have yielded break-throughs to prevent and treat many ocular disorders. By leveraging innovative peptide-based assembly, protein-polymer and peptide-based therapeutics have created new opportunities for controlling drug delivery and maximizing clinical success in the eye. Like some conventional polymeric formulations, these macromolecules have the potential to significantly extend release kinetics. Unlike many polymeric formulations, peptides are tailored by genetic engineering with sequence-level precision, making them intriguing alternatives to traditional formulations. While there are many possible technologies under development for ocular therapies, elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) and silk fibroin are among the state-of-the-art protein-polymers that promise to improve ocular drug delivery in unique ways. Moreover, since recombinant polypeptides can be produced at high yield and with specific, immune-tolerant sequences, they lend themselves to comparative optimization of peptide architectures [77–87].

ELPs are an artificial, bioengineered class of protein-polymer, bioinspired from human tropoelastin. This protein is a soluble precursor of extracellular matrix (ECM) and connective tissues, composed of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic motifs that get enzymatically crosslinked via lysine residues in the ECM space. The final elastin fibrils are insoluble and durable enough to last a lifetime. In contrast, the canonical ELP unit consists of only a short pentapeptide sequence, (VPGXG)n, in which n specifies the molecular weight and the guest residue, X, determines the polymeric solubility. Among the most interesting properties of ELP, are their inverse phase separation properties, akin to a polymeric lower critical solution temperature (LCST). Taking the advantage of this unique property, certain ELPs demonstrate thermal responsiveness like an on/ off switch. In aqueous solvents below its formulation transition temperature (Tt), ELP is highly soluble. In contrast, when the temperature is raised just a few degrees above Tt, ELPs collapse into a liquid phase ‘coacervate.’ In a clear solution, this can be easily visualized as turbidity since the refractive index of ELP coacervate differs from that of water. This thermodynamically reversible phase transition is explained by the Gibbs free energy, (ΔGmix = ΔHmix – TΔSmix), whereby above the temperature where DG equals zero, the Tt ~ ΔHmix/ΔSmix. Because of its rapid assem bly of large, viscous microparticles upon heating to body temperature, this phase transition has a viable role in prolonged release for fusion peptides and proteins [77,79,88–91]. A broad range of studies have been reported by our group and others to assess the structure–function relationships between ELP architecture and biotechnological/pharmaceutical applications in the eye (Table 1). Extensive efforts have been utilized to develop these diverse structures with favorable properties and potential biomedical activity [88].

Table 1.

Architectures of applied ELP- functionalized systems with applications to ocular drug delivery.

| platform | amino-acid sequence | potential application | ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| cry-SI | MGDRFSVNLDVKHFSPEELKVK G(VPGSG)48(VPGIG)48Y | Intravitreal retention of alphaB crystallin derived peptide, relevant to age-related macular degeneration | [82,96,97] |

| HN-S96 HN-V96 |

MGMAPRGFSCLLLLTSEIDLPVKRRA G(VPGSG)96Y MGMAPRGFSCLLLLTSEIDLPVKRRA G(VPGVG)96Y |

Solubilization of mitochondrial humanin peptide relevant to protection of retinal pigment epithelial cells against oxidative stress | [98] |

| FAF FSI |

M-*FKBP-G(VPGAG)192-FKBP M–FKBP-G(VPGSG)48(VPGIG)48Y |

Systemic administration of rapamycin to treat autoimmune dacryoadenitis, relevant to Sjögren’s Syndrome | [99] [100] |

| FKBP-V48 | FKBP-G(VPGVG)48Y | ||

| IBPAF | MFEGFSFLAFEDFVSSI G(VPGAG)192-FKBP | ICAM-1 targeting of rapamycin to autoimmune dacryoadenitis, relevant to Sjögren’s Syndrome | [81] |

| 5FV 5FA |

M-[FKBP-(VPGVG)24]4-FKBP M–[FKBP-(VPGAG)24]4-FKBP |

Intralacrimal delivery of rapamycin for treating Sjögren’s Syndrome-related autoimmune dacryoadenitis | [101] |

| CA192 | M-**CypA-G(VPGAG)192Y | Systemic administration of cyclosporine to improve tear production, relevant to Sjögren’s Syndrome | [80] |

| CVC CAC |

M–CypA-(VPGVG)96-CypA M–CypA-(VPGAG)96-CypA |

Supra-lacrimal administration of cyclosporine A for reducing Th-17 cells and enhancing tear production, relevant to Sjögren’s Syndrome | [102] |

| V96 S96 |

MG(VPGVG)96Y MG(VPGSG)96Y |

Temperature-dependent loading and release from contact lenses | [103] |

| LSI LS96 |

M-***LACRT-G(VPGSG)48-(VPGIG)48Y M–LACRT-G(VPGSG)96Y |

Regeneration of the corneal epithelium following topical administration, relevant to corneal wound healing | [104] |

| LP-A96 | MGKQFIENGSEFAQKLLKKFSLWA G(VPGAG)96Y | Solubilization of lacritin-derived peptide activates exosome production in Human Corneal Epithelial Cells | [105] |

| LV96 | M–LACRT–G(VPGVG)96Y | Intralacrimal retention of lacritin enhances tear production, relevant to dry eye disease | [106] |

FKBP amino acid sequence, derived from human FKBP12: GVQVETISPGDGRTFPKRGQTCVVHYTGMLEDGKKFDSSRDRNKPFKFMLGKQEVIRGWEEGVAQMSVGQRAKLTISPDYAYGATGHPGIIPPHATLVFDVELLKLE.

CypA amino acid sequence, derived from human cyclophilin A: VNPTVFFDIAVDGEPLGRVSFELFADKVPKTAENFRALSTGEKGFGYKGSCFHRIIPGFMCQGGDFTRHNGTGGKSIYGEKFEDENFILKHTGPGILSMANAGPNTNGSQFFICTAKTEWLKHVVFGKVKEGMNIVEAMERFGSRNGKTSKKITIADCGQLE.

LACRT - amino acid sequence, derived from human lacritin: GEDASSDSTGADPAQEAGTSKPNEEISGPAEPASPPETTTTAQETSAAAVQGTAKVTSSRQELNPKSIVEKSILLTEQALAKAGKGMHGGVPGGKQFIENGSEFAQKLLKKFSLLKPWAGLVPRGS.

Silk-like polypeptides (SLPs), represent a viable alternative to deposit peptides in the ocular space. Silk is a fibrous protein, generated by silkworms. It is mainly formed from two proteins, sericin and silk fibroin. Sericin exists in hydrophilic, amorphous form and accounts for 25 % of raw silk. In contrast, fibroin consists of subunits of light and heavy chains, bound covalently via disulfide linkages [40,59]. Bioinspired from repetitive sequences found in silk fibroin, SLPs consist of a short repetitive sequence encoding (GAGAGS)n. Unlike the ELPs, the SLPs are kinetically trapped into intermolecular beta-sheet structures, which may play a role in their incomplete proteolysis; however, this does facilitate longer-term release of entrapped cargo [77,92]. To mix the physical properties of SLPs and ELPs, additional studies have explored silk-elastin-like proteins (SELPs) for various delivery purposes. Their primary structure consists of alternating silk and elastin entities that display dual features of crystallinity and elastomerity, thereby giving them unique mechanical and stimuli-responsive properties [93–95].

The focus of this review is the emerging role of peptide-based biomaterials in ocular drug delivery, which has been a major focus of our group. To put into context how peptide biomaterials might overcome additional barriers to ocular drug delivery, this review next explores one of the most clinically-widespread strategies for protein administration to the eye. Afterwards, this manuscript focuses on pre-clinical examples showing how peptides and proteins have been used in preclinical studies through different routes of administration. Where appropriate to develop more effective treatments, emerging uses for ELPs and SLPs will be identified.

2. Clinical status of direct peptide administration in ophthalmology

2.1. Intravitreal administration of anti-VEGF protein therapy

Over the last 20 years, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy has revolutionized the treatment of various ocular pathologies including proliferative diabetic retinopathy, neovascular retinal disease, macular edema, vein occlusion, and age-related degeneration disorders. VEGF, a 40 kDa dimeric glycoprotein, is a critical regulator of angiogenesis, signaling factor of endothelial cell mitogen, and prime inducer of vascular permeability, which plays an important role in both normal and disease physiology. VEGF expression is upregulated under hypoxic conditions. In the normal physiological context, it promotes the angiogenic development of new blood vessels and regulates cellular proliferation, migration, and adhesion, which are required for wound healing. Excessive VEGF promotes the formation of abnormal, leaky blood vessels and capillaries, which contributes to vision impairment disorders. Moreover, blocking the biological effect of VEGF molecules using anti-VEGF therapeutics like ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept have all validated the drug-ability of VEGF in the clinic [107–110].

Lucentis is a prescribed brand name for a humanized IgG1 kappa isotype monoclonal antibody, called ranibizumab. Intact IgG antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that have been subjected to extensive engineering and modification. Their structure consists of a variable domain (Fv) and crystallizable domain (Fc). The Fv region is adaptable to bind many antigens, some of which may include surface receptors or soluble growth factors. The function of the Fc region is to improve the pharmacodynamic responses to antigens through the recruitment of additional immune effectors. IgGs are bivalent immunoglobulin molecules of an approximate molecular weight, 150 kDa. Total IgG in humans is composed of four subclasses known as IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4. Each subclass possesses unique structural and functional characteristics. It is composed of two identical copies of heavy and light chains, of which the light chains are linked by non-covalent interactions to heavy chains. Unlike anti-angiogenic IgG antibodies, ranibizumab was engineered without its Fc domain. Lacking the glycosylated Fc region, this antibody therapeutic lacks immune effector functions. This property made it safer for introduction into the vitreous capsule. Furthermore, it has a reduced molecular weight, compared to the full-size antibody. The smaller size has been associated with easier penetration into the retina as well as faster ocular clearance [111–114].

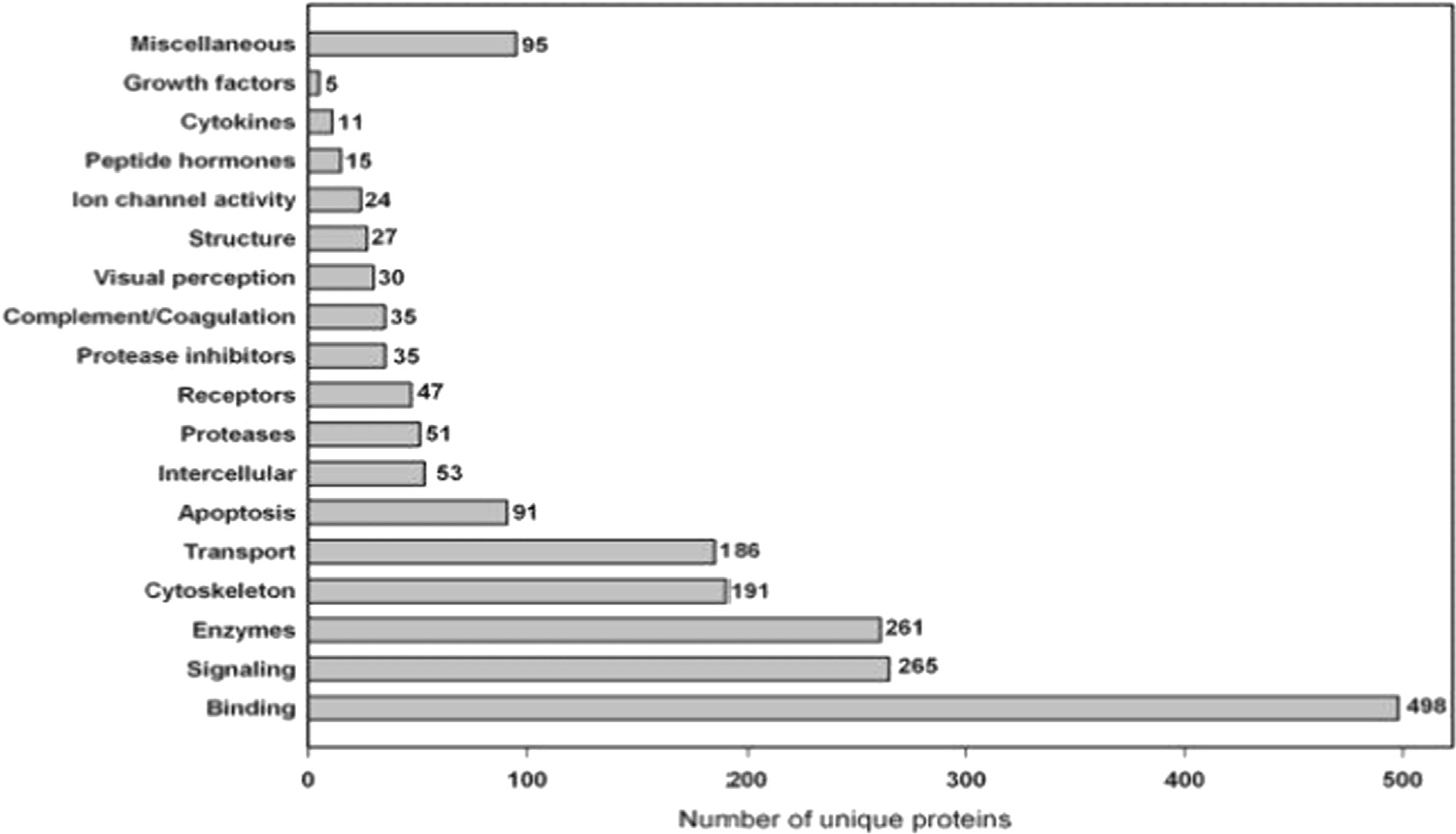

Regarding sites of administration proven effective for reaching the posterior segment, the intravitreal site is the most common. The vitreous humor is a gel-like extracellular, transparent, and highly hydrated mass of mainly water. It occupies the posterior segment and fills about two-thirds of the eye globe. It is particularly important for maintaining the eyeball shape, the refractive properties of the optical pathway to the retina, and the stability of proteins within the visual field. It is also important in coordinating the eye growth and the metabolic respiratory rate of the retina [73,74]. While optically clear, the vitreous is filled with numerous distinct proteins. Many efforts have been employed for cataloging the proteomics of the vitreous. For example, the Nakanishi group [115] identified 51 proteins from the vitreous humor of patients with a diabetic retinopathy using 2-D gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. In more recent studies, Gao and coworkers [116] evaluated vitreous tissues from individuals with diabetes and performed proteomic analysis. The data identified 252 different proteins, using one-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and nano-LC/MS/MS. In a subsequent study, Aretz and collaborators [117] applied deep prefractionation screening technologies, SDS-PAGE, and liquid-phase isoelectric focusing, which successfully detected 1,111 unique proteins of the vitreous (Fig. 2). These proteins likely perform various functions to maintain ocular homeostasis. In addition to understanding the microenvironment relevant to intravitreal administration, a subset of these proteins may be useful as disease biomarkers or as potential therapeutics.

Fig. 2.

Functional annotation of the unique proteins identified in the vitreous humor, adapted with permission from the Aretz group [117].

These proteins include the vascular endothelial growth factor A inhibitor (VEGF-A). The antibody ranibizumab antagonizes VEGF-A protein, which blocks its binding to (VEGFR1 and VEGFR2) receptors, interferes with vascular angiogenesis, reduces microvascular endothelial hyperpermeability to plasma proteins, and slows neovascular degeneration of the retina. Based on its relative safety and efficacy, intraocular ranibizumab is used for a variety of indications, including diabetic retinopathy and neovascularization. Ranibizumab has been marketed globally; furthermore, its widespread acceptance by patients and ophthalmologists demonstrates the feasibility of intravitreal therapies. Thus, the landscape of intravitreal drugs may extend to other biological entities of differing molecular weight, mechanisms of action, therapeutic modality, ocular residence time, and indications [51,111].

Using proteomics analysis to study the effect of ranibizumab on patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), Zou and the coworkers [118] introduced this anti-VEGF treatment for 5–7 days. The research study compared treated PDR patients, nontreated PDR patients, and non-diabetic patients. In addition to the suppression of VEGF, it has been revealed that the anti-VEGF treatment had a noticeable effect on the vitreous protein profiles, at which these proteins modulate signaling pathways of inflammation, tissue integrity, immune response, angiogenesis, cellular growth, complement activation, etc. This effect was significantly greater compared to an untreated group and was compared to a healthy group.

In a preclinical study, Ghosh et al. [119] innovated a platform containing ranibizumab linked with a 97 amino acid peptide that binds hyaluronan, one of the major components of the vitreous. They tested its efficacy following intravitreal administration to rabbit and monkey models with a neovascular retinal disease. The study showed a notable attenuation of VEGF-induced retinal changes, thereby enhancing the retinal neovascularization. The incorporation of the peptide in the delivery platform played a critical role in attaining a longer retention by 3 to 4-fold, compared to the non-modified anti-VEGF molecules, making it a beneficial approach for reducing the dosing frequency through the extended-release formulation.

Generic biosimilars of ranibizumab have faced complications, which include structural differences compared to the ranibizumab, quality validation of safety and efficacy studies, costs of manufacturing, and survey reports. For example, survey reports or questionnaires ascertain the patient’s treatment expectations [120]. Along with ranibizumab, bevacizumab (Avastin) and aflibercept (Eylea) are the most comparable anti-VEGF biologics (Table 2). Bevacizumab, a full-length humanized monoclonal antibody, is recognized by its binding affinity to all VEGF-A isoforms, resulting in altering the recognition of VEGF-1 and VEGF-2 cognate receptors expressed on the vascular endothelial cells’ surface, which blocks signal transductions of VEGF/VEGFRs. While it has been used to block cancer metastasis, it has also been used off-label as an alternative to ranibizumab [121,122]. In contrast, aflibercept is an IgG1chimeric protein, constructed from the fusion of Fc regions to two domains of VEGFR, making it a dummy receptor for VEGF. Many comparative studies have evaluated the doses, effectiveness, safety, half-life times, and visual outcomes for these intravitreal therapies [123–127].

Table 2.

Properties and parameters of the anti-VEGF protein-based intra-vitreal therapies.

| Drug | Structure | Binding target | Mwt (kDa) | KD for VEGF165 (pM) | Estimated intra-vitreal half-life (t1/2) | FDA-approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Ranibizumab | Antibody fragment | VEGF-A | 48 | 46 | 3.2 days | Approved in 2006 |

| Bevacizumab | Full-sized monoclonal antibody | VEGF-A | 149 | 58 | 5.6 days | Off-label for ophthalmic purposes |

| Aflibercept | Fusion protein | VEGF-A/B, PIGF | 115 | 0.49 | 4.8 days | Approved in 2011 |

In a trial reported by Son and coworkers [123], they evaluated functional and anatomical disorders for macular edema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and assessed the retrospective efficacy and safety profile of ranibizumab and bevacizumab. They administered intravitreal injections of 0.5 mg and 1.25 mg of ranibizumab and bevacizumab, respectively. The group started with initial three-monthly doses, after which the treatment plan was evaluated monthly. Both therapies provided relatively equal vision improvement, as well as a significant reduction in the central foveal thickness, a biomarker for the macular edema measured by Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT). Surprisingly, there was no significant difference between treatments. While this study has limitations, such as the short duration of treatment and modest sample sizes, both therapies are recommended as sufficient for patients with macular edema associated with BRVO.

Another long-term comparative trial on these materials was published by the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Treatments Trials (CATT) research group; (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00593450) [132]. They established a phase 3 randomized, multicenter study of a one-year follow-up. The patients received intraocular injections of either ranibizumab or bevacizumab either monthly or as needed. OCT revealed a significantly greater reduction in the fovea thickness of the retina in the monthly ranibizumab group compared to the other groups. Comparing the serious side effects in both groups, ranibizumab showed lesser toxic effects and risk ratios. Overall, the analysis concluded that both ranibizumab and bevacizumab in their visual acuity effects and the adverse effects need further detailed studies.

Having demonstrated similar efficacy between the intravitreal administration of both anti-VEGF antibodies, another one-year retrospective study was recently reported comparing ranibizumab and aflibercept for diabetic macular edema. Bandari and coworkers [133] tracked the statistical changes of visual acuity changes and foveal central subfield thickness. The median injections of eyes receiving aflibercept received about two more injections than ranibizumab. Despite this difference in the number of injections, it wasn’t counted as a significant consideration. Despite starting with thicker fovea at the start of the study, aflibercept treatment groups showed a significantly greater reduction in the central subfield thickness as well as a greater increase in visual acuity compared to ranibizumab. Aflibercept was proposed as a treatment plan when the measurement of visual sharpness is 20/50 and worse.

While all three VEGF treatment modalities are effective, Heier and coworkers [134] evaluated a comparative 2-year clinical study from the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network of ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept in patients with diabetic macular edema and visual acuity impairment. They applied these three anti-VEGF therapies at variable doses and analyzed the mean improvement of the visual acuity. While their analysis confirms a slightly more positive response to aflibercept, they suggested that the significantly cheaper option, bevacizumab, would allow treatment of at-risk patients before they experience more significant vision loss.

To examine potential differences in intravitreal toxicity using an in vitro correlate, Malik and coworkers [126] employed a human retinal pigment epithelium cell culture model (ARPE-19). They compared ranibizumab, bevacizumab, aflibercept, and zivaflibercept, which is a hyperosmolar, lower-pH, lower-dose formulation of aflibercept. Following exposure to these anti-VEGF agents for one day over a range of concentrations, they compared cell viability, cell death, and mitochondrial membrane potential, which is a sensitive indicator of apoptotic cell death. Ranibizumab demonstrated a significantly lower potential for toxicity than the other three formulations. Even at 10x the recommended dose, ranibizumab showed only a minor reduction in membrane potential. In contrast, both ziv-aflibercept formulations and the full-length monoclonal bevacizumab decreased mitochondrial membrane even at clinical dosing concentrations. That might be attributed to a combination of greater binding affinity of aflibercept than ranibizumab, the effect of introducing a hyperosmolar diluent, as well Fc-mediated signaling prevalent in either aflibercept or bevacizumab.

2.2. Intra-lacrimal administration of botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxin (BoNTA) is the first applied neurotoxin in ophthalmology. Since 1970 s, several clinical trials have been exploring its role in treating various ophthalmic disorders. This protein is produced by clostridium botulinum bacteria and characterized by its potential of inhibiting muscular contractions and drainage disorders by interfering with the release of acetylcholine from the presynaptic neurons. Owing to this property, it has emerged for correcting disorders of muscle tone and involuntary excessive secretions [135–137].

For example, Montoya et al. [138] applied BoNTA injection for hyperlacrimation management in four patients. They administered 10 units of BoNTA into the affected lacrimal gland as an initial dose and one week later, the second dose was injected. The cases were followed up for 6 months. Following the first week, all patients noted symptomatic improvement. Following the second dose, they reported a complete resolution. After 3.5 months of these initial injections, 2 patients complained about symptoms relapse, and they were given a third dose that showed a lasting effect until a 6-month visit. Overall, the patients experienced a favorable outcome in life quality with minor complications or easily controllable side effects like dryness or stinging.

Later, Ziahosseini et al. [139] performed a clinical study using (BoNTA) for treating lacrimal outflow obstruction. BoNTA has been shown to inhibit the acetylcholine release from the nerves ending of LG. The researchers injected BoNTA at the palpebral lobe of the LG with a mean interval of 3.9 months between injections. Significantly, the data showed that 70% of patients had a > 60% relief in their symptoms in 10 weeks with an improvement in Munk score from 3.4 to 1.6. These studies illustrate the long-standing clinical feasibility of intralacrimal injection of peptide/protein therapeutics. Provided it addresses a significant problem, and the interval of dosing can be minimized, intralacrimal injection appears well-suited to address issues of lacrimation, which may extend to dry eye disease.

3. Early-stage research in intraocular delivery

3.1. Lacrimal gland

The lacrimal gland (LG) is a main functional source of the aqueous components of the tear film. It secretes proteins, electrolytes, mucins, and water, which nourish and protect the ocular surface as well as provide its smooth optical surface. When combined with secretions of the meibomian glands, it produces tears that support homeostasis on the ocular surface. LG dysfunction is characterized by eye dryness, ocular discomfort, visual disturbance, and in severe cases can result in vision loss. The LG anatomy consists of acinar, ductal, and myoepithelial cells. The ductal cells have a primary function on modifying the fluid secreted by the acinar cells and to act as a conduit for water and electrolytes. While, the myoepithelial cells are characterized by alpha-smooth muscle actin, which contracts to move fluid toward the ocular surface [25,140–142].

In an application of ELP-based delivery to the inflamed lacrimal gland (LG), Lee et al. [99] investigated a polypeptide fusion as an option for drug delivery. Rapamycin (Rapa) has been widely used in organ transplantation and with other rare diseases. However, it has poor bioavailability, unpredictable pharmacokinetics, and a narrow therapeutic index that may require therapeutic drug monitoring. As an alternative strategy to deliver Rapa, they introduced the 97 kDa ‘Berunda’ (two-headed) fusion carrier called FAF (Table 1), which is composed of human FKBP12 binding protein fused to both the N and C termini of a humanized ELP called A192. When complexed with Rapa, this formulation provides high drug solubilization, slow absorption, intracellular release, and biodegradable potential. In detail, FAF bound to Rapa was used to study immunomodulatory effects in non-obese diabetic mice (NOD). The experimental results revealed the knockdown of the MHC II, IL-12a, and IFN-c cytokines proteins that are involved in autoimmunity. A pharmacokinetic study revealed that SC FAF had about 66% bioavailability without a noticeable loss of Rapa from the carrier during absorption. Compared to free Rapa, Rapa delivered by this two-headed polypeptide system fostered an 8-fold increase in the plasma concentration.

In a related study, this team [81] developed an A192 ELP FKBP12 fusion as a molecularly targeted carrier for Rapa. This system (IBPAF) possesses a peptide ligand that binds ICAM-1 (Table 1), which is specifically expressed in the inflamed LG for Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) patients. By recruiting lymphocytes from the plasma, ICAM-1 contributes to autoimmune inflammation of the LG, called dacryoadenitis. In SS, this leads to a loss of normal secretory activity that is responsible for the production of the aqueous component of healthy tears. In the absence of normal tears, these patients develop severe dye eye disease. The pharmacokinetic studies following IV injection revealed that IBPAF bound Rapa elicited targeted accumulation with longer plasma retention and residency in systemic circulation, lower side effects, and more potent accumulation, compared to free Rapa delivery. In addition to the targeting property of this system, it allowed Rapa release for up to (5–9) h and exhibited a volume of distribution comparable to the mouse plasma volume.

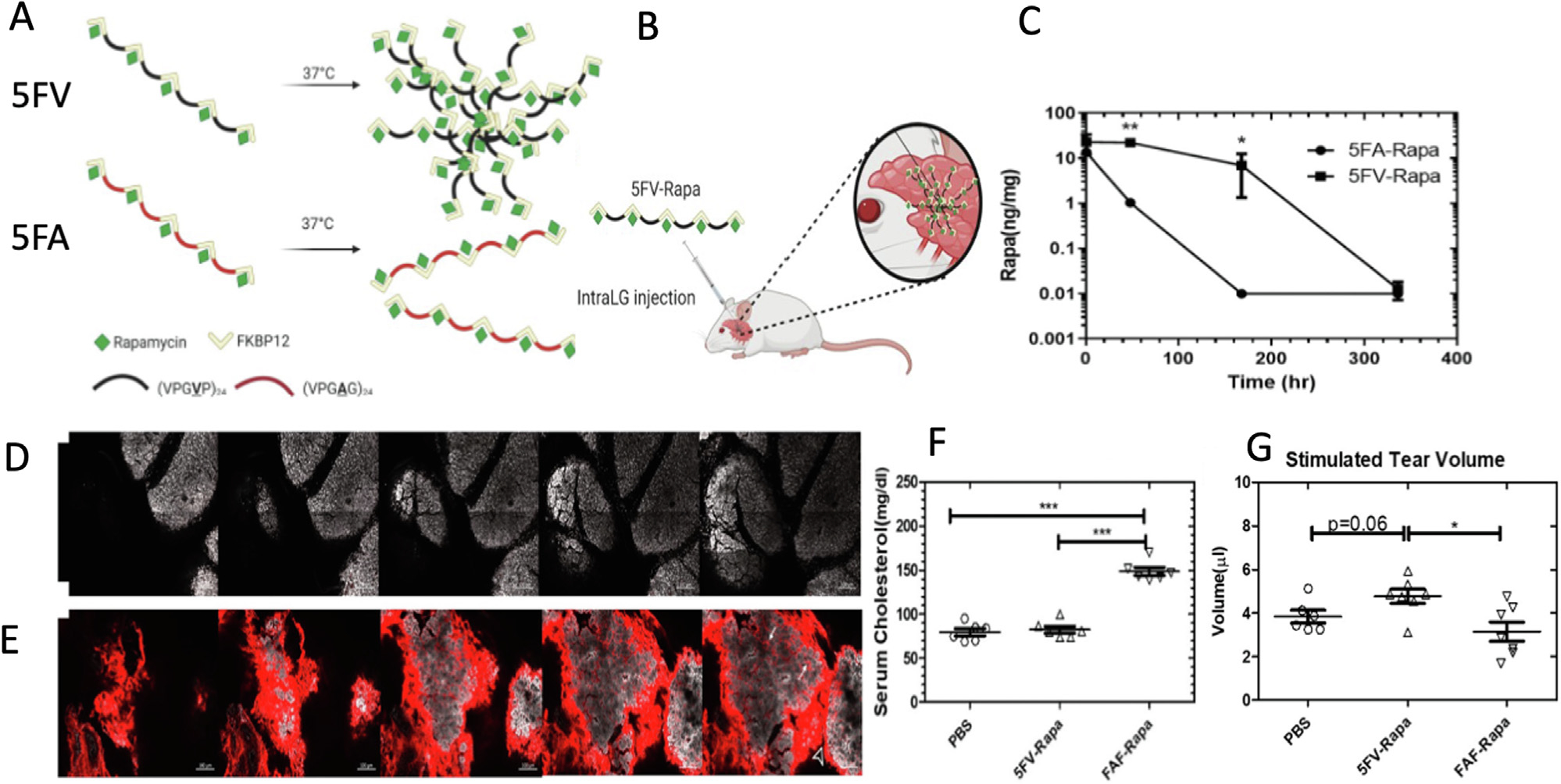

A variety of ELP rapamycin formulations have now been evaluated by our team in the NOD mouse model of autoimmune dacryoadenitis described above. For example, Shah and collaborators [100] first explored the delivery efficiency of Rapa in two different fusions, which were lower MW compared to FAF or IBPAF. They initially compared FKBP-V48 and FSI as delivery carriers and investigated their efficacy also in the NOD mouse model of SS (Table 1). FSI was designed to form a Rapa-binding nanoparticle, while FKBP-V48 remains freely soluble at body temperature. A dialysis-based drug release study revealed loss of rapamycin with terminal half-lives of 63, 13 h for FSI, FKBP-V48 respectively, both of which were consistent with sustained release. These formulations were compared for pharmacokinetic influence on rapamycin, whereby FSI-Rapa followed a bi-exponential decay with a distribution half-life of 0.36 hr and a terminal half-life of 8.8 hrs. In contrast, FKBP-V48 followed a single exponential decay with a terminal half-life of 5.6 hrs, which was close to that observed for free Rapa. FSI-Rapa not only reduces histological signs of nephrotoxicity compared to the free drug, but also caused a greater reduction in a cathepsin S (CATS) biomarker, which is a lysosomal peptidase implicated in autoimmune disorders including Sjögren’s Syndrome. Most recently, our team [101] has developed a sustained release formulation for rapamycin, which contains 5 copies of the FKBP protein linked by an ELP that phase separates at physiological temperatures, which is called 5FV (Fig. 3A,B). Valine was incorporated in 5FV as a guest residue (Table 1), which enabled drug retention within the LG for one week following injection (Fig. 3C). When alanine was chosen as a soluble guest residue, 5FA was quickly absorbed from the LG as visualized by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3D, E). Interestingly, intra-LG treatment with 5FV-Rapa prevented hypercholesteremia, which is a side-effect for systemic FAF-Rapa given by subcutaneous administration (Fig. 3F). Intra-LG 5FV-Rapa also significantly enhanced tear production in comparison to systemic FAF-Rapa (Fig. 3G). These findings demonstrate the versatility of structures achievable by using different ELP-mediated strategies to carry FKBP rapamycin complexes to the eye.

Fig. 3.

The reversible phase separation of ELP sustains the retention of rapamycin within the lacrimal gland (LG) of NOD mice. These 12–14 week old male NOD mice have lymphocytic infiltrates in their LGs, dacryoadenitis, and can model dry eye disease characteristic of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Shown here is an example from Ju and colleagues of an ELP fused with FKBP, the cognate binding partner for rapamycin (Rapa). (A) A version called 5FV was developed that forms a depot at body temperature, which is contrasted with a soluble control called 5FA. 5FV contains the more hydrophobic amino acid, valine, in place of alanine residues used in 5FA. Both have similar MW and the capacity to bind 5 Rapa per fusion protein. (B) Following injection into the LG, only 5FV coacervates, which (C) causes long-term drug retention for at least a week after intra-LG injection. (D) As imaged by confocal microscopy of a sectioned LG, the soluble 5FA carrier (red) was cleared from the gland (white) within one day, while (E) the 5FV formulation (red) was retained at high levels. F) A systemic dose of a positive control (FAF-Rapa, Table 1) induced hypercholesteremia in NOD mice, whereas local administration of 5FV-Rapa did not. G) Local 5FV-Rapa increased tear production of the NOD LGs, while systemic FAF-Rapa control could not. The study is adapted with permission from [101]. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In a related application [80] exploring tear flow in the NOD mouse model of autoimmune SS, an ELP fusion protein was developed to deliver Cyclosporine A (CsA). This powerful immunosuppressant was bound to its cognate human receptor, cyclophilin A (CypA), which was linked to the high molecular weight ELP, termed A192. The goal of this formulation was to deliver CsA with minimal systemic toxicity, longer administration intervals, and enhanced production of tears. When bound to CA192, the CsA was released with a half-life of 54 hrs under sink-dialysis conditions, which demonstrated its power to retain the drug in solution. Using cellular uptake studies, an NHS-rhodamine labeled formulation exhibited notable fluorescence accumulation, which colocalized in lysosomes following the endocytic uptake into Jurkat cells. This formulation successfully inhibited calcineurin-dependent phosphorylation of NFAT and secretion of IL-2 as well. In mice, the formulation had a subcutaneous bioavailability of 31% with a terminal half-life of 22 hrs. This formulation enhanced the safety profile of CsA as indicated by a reduction in blood urea nitrogen compared to a formulation of the free drug; furthermore, it significantly improved tear flow after seven injections given over two weeks. In a more recent study, a second generation of ELP-CypA constructs were developed that only require a single dose. Similar to FAF-Rapa, they developed [102] a bi-headed fusion with cyclophilin at both the amino and carboxy termini, but linked these together A96 and V96 ELPs into Th17-like cells as well as the NOD mouse. An advantage over the CA192 formulation (a maximum 1.3% CsA by mass), these CAC and CVC platforms have higher loading capacity (a maximum 3.0% CsA by mass). Only the CVC formulation formed a depot with at least a two-week release. In the NOD mouse model, this improved tear flow and reduced abundance of Th-17 cells after a single dose. Both above examples of 5FV-Rapa and CVC-CsA demonstrate the potential advantages for ELP-based fusion proteins to provide extended, local release of macrocyclic immunosuppressants. As shown for the 5FV-Rapa and CVC-CsA above, the temperature-dependent association of ELPs is an appealing strategy for retaining biologically active peptides within the eye. Both approaches now require more advanced preclinical studies, including toxicology and immunological assessments.

3.2. Vitreous

Among the characteristics of the vitreous humor described above, it is a transparent hydrogel network of collagen and hyaluronan, filling the eye between lens and retina, possessing an antioxidant role, participating in eye growth and development, serving as a mechanical damper, and maintaining the globe’s shape [143–145]. As noted by the clinical success of anti-VEGF therapies, intravitreal delivery is efficient in retinal and posterior eye disorders. However, the negatively charged carbohydrate hyaluronan stands as a critical challenge in delivery. For nano-systems containing positive charges, such as those used to condense oligonucleotides, the positively charged surface interacts with networks of hyaluronic acids, resulting in immobilization, immunogenicity, and toxicity [66,146].

To control this ‘vitreous anchoring’, Li and coworkers [147,148] fabricated a sustained delivery system composed of a colloidal nanocarrier of dextran as a natural polysaccharide core, covalently linked with L-Arg peptides through carbamate bonds. They tested their effect upon the intravitreal administration into the eyes of adult rats. As intended, the degree of positively charged amino acids per nanoparticles modulated the zeta potential. Fluorescence imaging and histological evaluations showed that peptide-modification with different numbers of cationic groups increased surface ionization, which consequently slowed the apparent diffusion rates and half-lives in the vitreous. The increase in zeta potential was inversely correlated with the binding strength to hyaluronic acid and the diffusion of the delivery system. Optimizing the ratio of injected volume to vitreous viscosity and hyaluronic acid composition is a rate-limiting step for achieving the desirable diffusion rates and ocular half-lives. The authors concluded that the ionic binding of these peptide-modified nanoparticles to hyaluronic acid had a promising effect on their mean residence time and potency without significant adverse effects on the ocular integrity.

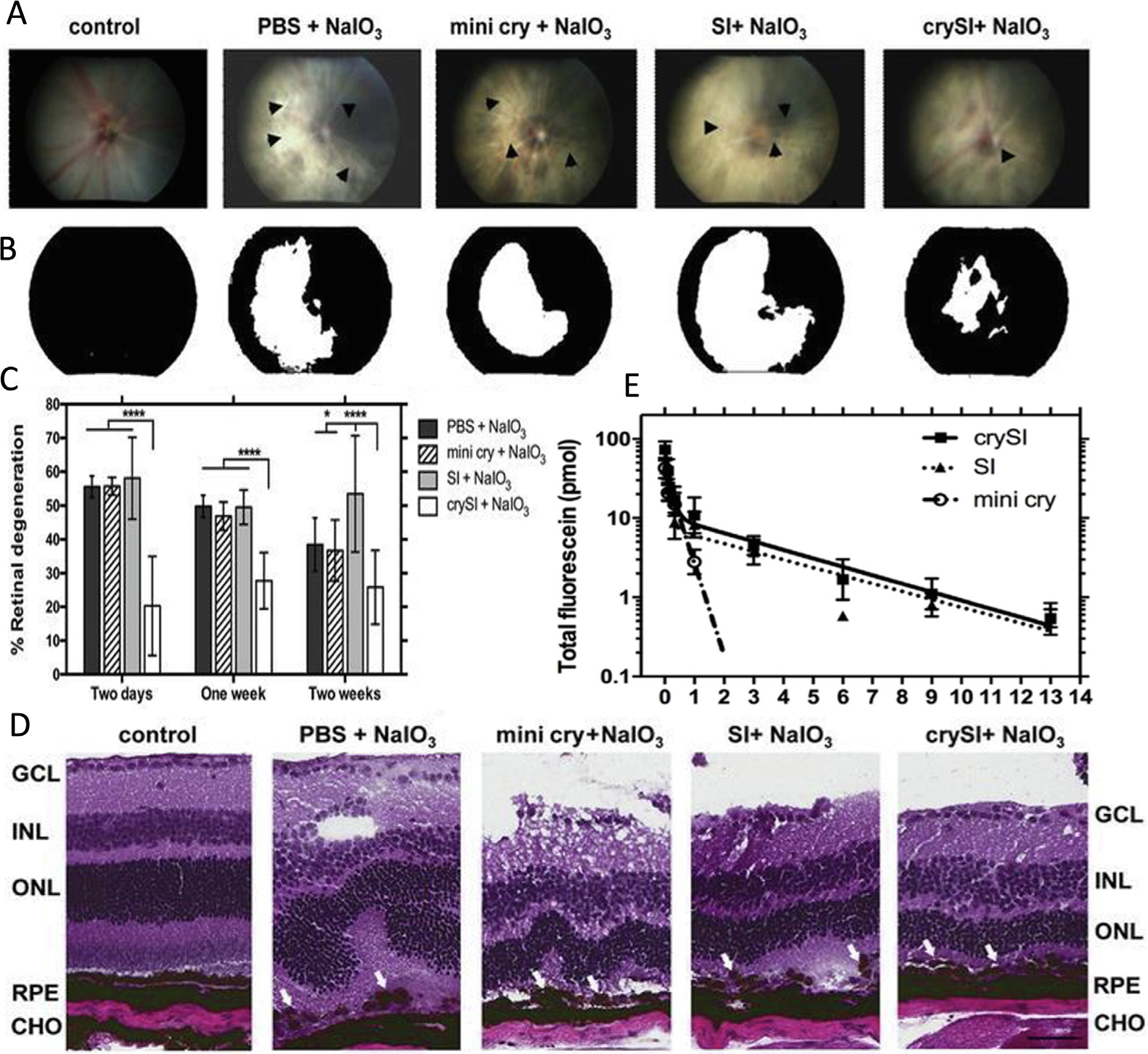

With potential applications to dry AMD, Sreekumar and coworkers [96] adapted this idea to extend the neuroprotective potential of a short peptide sequence derived from human AlphaB Crystallin, called ‘mini cry.’ Wet AMD is characterized by the angiogenesis and vascular leakage around the retina. While less prevalent, dry AMD lacks this vascular leakage and is unresponsive to anti-angiogenic therapies. Thus, alternative therapies are needed to prevent progression of dry AMD. Abundant in the cornea, this small heat shock protein and mini cry both have chaperone and cell regulatory activity in ocular tissues. In vitro, mini cry protects human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells against oxidative stress. In vivo using a mouse model, the free peptide has too short a retention time in the eye to provide protection. To enhance the retention and efficacy after an intra-vitreal dose, mini cry was linked to an ELP called SI, forming crySI. This formulation was evaluated in a 129S6/SvEvTac mouse model with a chemically-induced (NaIO3) model of geographic atrophy, which has been used to model the dry form of AMD. In vivo studies verified the superior effectiveness of crySI compared to mini cry alone. crySI was cleared from the vitreous with a mean residence of 3.0 days, which was approximately 7.5x longer than that observed for the mini cry peptide (Fig. 4). It was found to be protective against retinal degeneration for at least two weeks before the chemical challenge. Compared to the free mini cry peptide, intravitreal crySI increases the relative bioavailability, prolongs the ocular pharmacokinetics, and retains more normal histological features of the retina.

Fig. 4.

Retina-protective potential of a neuroprotective peptide ‘mini cry’ from the AlphaB crystallin protein fused to an ELP called SI. 129S6/SvEvTac mice were pretreated intravitreally with crySI (Table 1) and the other controls prior to chemical challenge with sodium iodate, NaIO3. (A) Color fundus images of mouse retinas were obtained one week after the challenge. The arrowheads point to the sites of retinal damage, where the scattering of white light enhanced significantly. (B) Image analysis of fundus photography was performed using a white mask, which estimated the percentage of the retinal damage over the entire field (black). (C) Statistical analysis of the retinal degeneration in pretreated mice, by two days, one week, and two weeks, prior to iodate challenge. For all the treatment controls and periods, only crySI showed significant protection of the retina (****p < 0.0001). (D) Histological analysis demonstrated epithelial monolayer disruption in all groups, except in the crySI pretreated groups. Pretreatment with crySI significantly protected the retinal pigment epithelium and neighboring photoreceptors. (E) The pharmacokinetic data showed that the fluorescently labeled crySI and SI had a sustained retention up to 14 days, while mini cry exhibited fast clearance in 3 days. Adapted with permission from [96].

Following this above study, this same team [98] suggested an alternative approach of using a mitochondrial-derived peptide with a cytoprotective activity termed humanin (HN) (Table 1). Interestingly, HN has the potential to protect the retinal cells from oxidative stress and neurodegenerative through STAT3 activation. Activated STAT3 upregulates pro-survival genes, innate immune signaling pathways, vision cycle quality, and other integrated biological activities. HN peptide was fused onto two ELPs of different solubility termed V96 and S96. At low temperatures, both fusions sterically stabilized this hydrophobic peptide as a soluble colloid; furthermore, they both gained temperature-induced phase separation. ELP V96 formed a coacervate above a temperature below 37 °C and thus may be an option for prolonged release, whereas ELP S96 fusions maintained low optical density and high solubility until well above 37 °C. These in vitro studies suggest that both HN polypeptide fusions had a similar degree of anti-apoptotic activity, suggesting they are candidates for ophthalmological applications; however, it is possible that HN-V96 may benefit from extended retention. As above, this work is in early stages requires future studies to evaluate their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties using appropriate models of retinal disease.

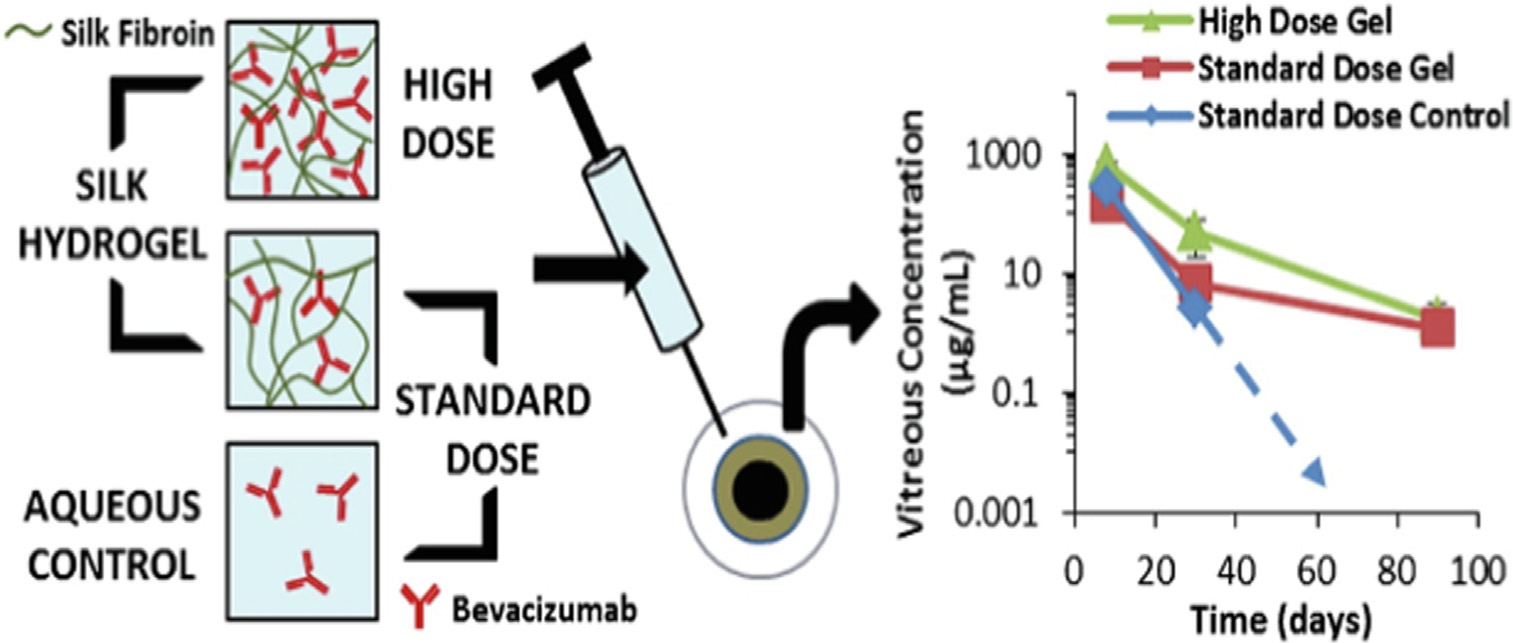

To explore a silk-based system with reduced dose frequency, non-inflammatory effects, and targeted bioactivity, Lovett and coworkers [149] developed well-tolerated injectable hydrogel of silk fibroin for targeted delivery of bevacizumab. The primary structure of this fibroin-derived polypeptide consists of alternating blocks of 12 hydrophobic motifs, largely glycine and alanine, and 11 hydrophilic blocks. They loaded the formulation by mixing the silk fibroin to bevacizumab at different concentration ratios and investigated efficacy using in vitro and in vivo studies. The results revealed that the bioactivity of bevacizumab was maintained, and the formulation efficiently performed sustained release kinetics for up to 90 days which accounts for approximate 3-fold increase in timespan, compared to the positive control. The ratio of silk to drug in the formulation modulated the rate of degradation. Related strategies may permit broader applicability for developing sustained treatments (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation showing the organization and kinetics profile of drug-loaded silk hydrogels at a standard and high drug dose. As shown, both standard and high dose of bevacizumab achieved equivalent or greater concentrations within the vitreous humor up to three months, compared to the positive control that fell below the quantification after 1 month, adapted with permission from [149].

3.3. Cornea

Corneal drug delivery is among the emerging delivery approaches that are directly accessible to peptide-modified carriers. As mentioned above, the normal cornea is transparent and rigid in structure with barrier functions and refractive power. Corneal epithelium injury or damage is one of the most common causes of visual dysfunction. Corneal transplantation is a sight-threatening resource because of its delayed recovery time and response. The bioengineering protein delivery approaches have been showing attractive means for corneal regeneration and enhanced healing effects [104].

Wang and coworkers [103] reported that contact lenses offer a unique approach to deliver two types of ELPs; V96 and S96 (Table 1). They tested the detachment and release of ELPs, and transfer to a transformed human corneal epithelial cell line (HCE-T). While observed above the ELP phase transition temperature, ELPs associate strongly with at least one commercially-available contact lens. Intriguingly, even below their transition temperature, ELPs adsorbed to lenses weakly through non-specific interactions. These interactions were dramatically strengthened upon coacervation in the presence of the contact lens. During release studies, 80% of the polypeptide is retained after an initial burst. That strategy provides an avenue to potentially load therapeutic peptides directly upon contact lenses and elutes them above the ocular surface for extended periods.

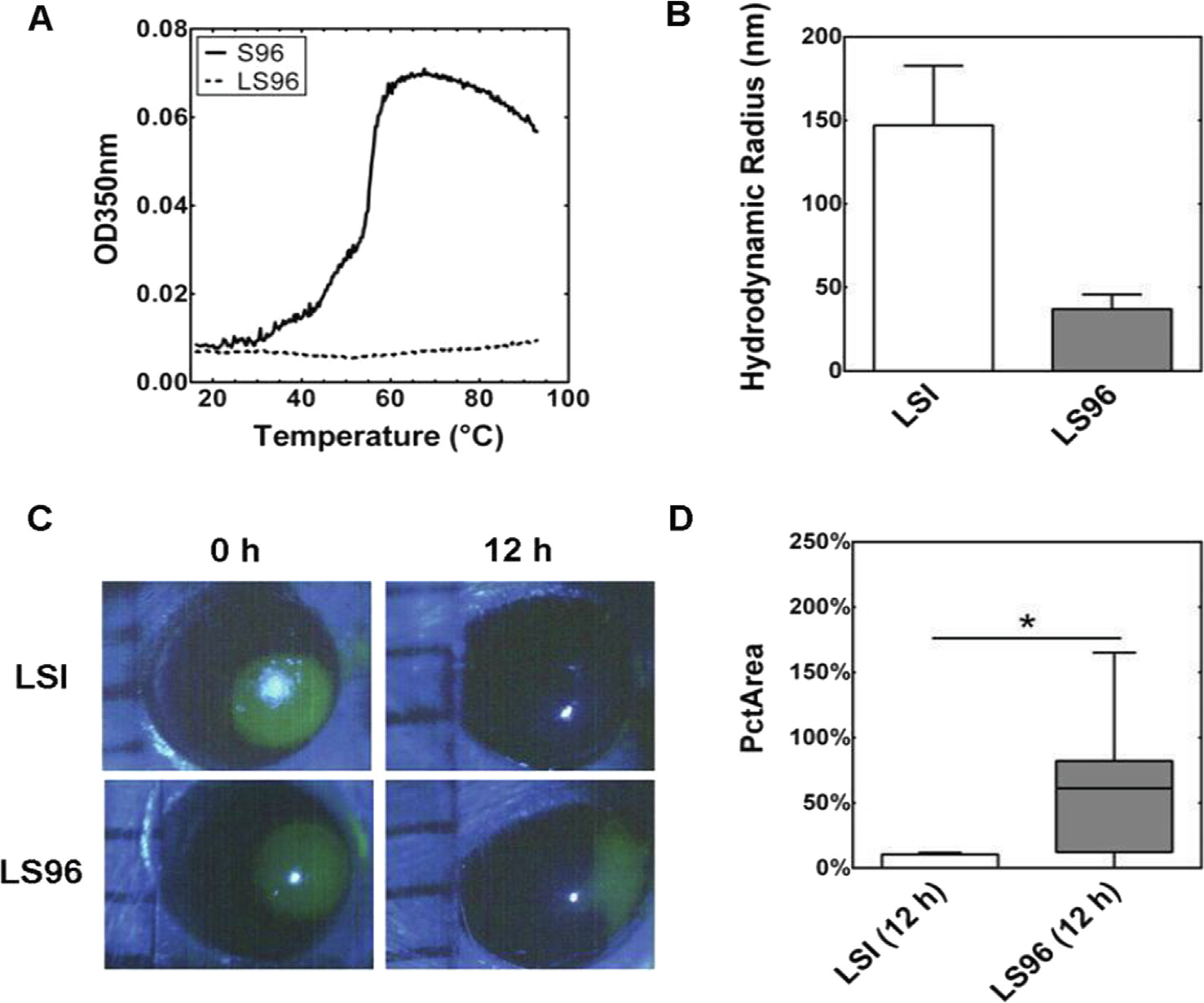

The MacKay group [104,150] also evaluated temperature-responsive ELP-based nanoparticles in both human corneal epithelial cell models (HCE-Ts) and NOD mice with corneal abrasions. They evaluated an ELP diblock copolymer-lacritin fusion (LSI), which was compared to either the ELP alone or a thermally-insensitive control, LS96. Lacritin is an 119 amino acid peptide, which is selectively expressed in tears. It is both prosecretory towards tear production and has growth-factor-like mitogenic activity. It binds to syndecan-1 cell surface receptors, restoring basal tearing and promoting corneal epithelial renewal. LSI formed a temperature-dependent nanoparticle, which was evaluated in interactions with contact lenses that might serve as a depot for extended delivery. Kinetic release studies quantified by fluorescence showed that release to the corneal epithelium depended strongly upon ELP-mediated phase behavior. Unlike LSI, LS96 lacks ELP-mediated assembly at physiological temperature, which is revealed by its reduced hydrodynamic radius at 37 °C. In comparing the two fusion proteins, LS96 was significantly less efficient at promoting closure of the in vivo defect in the corneal epithelium. Compared to unmodified ELP (SI) (Fig. 6), LSI had a significant effect on shortening the time required to restore epithelial integrity, which agreed with histological observations that regenerated corneal epithelium arising from LSI was almost indistinguishable from normal histology. In addition, the relative bioactivity of free lacritin and LSI was compared via lacritin-mediated Ca2 + signaling, cellular internalization using confocal microscopy, and HCE-T monolayer scratch recovery assays. More recently, a lacritin-derived peptide, called lacripep (GKQFIENGSEFAQKLLKKFSLWA), was fused to an ELP that remains soluble at 37 °C, LP-A96 (Table 1) [105]. This report showed two surprising findings. First, even without the apparent induction of ELP-mediated phase separation, this short peptide was sufficient to induce formation of a small nanoparticle. Second, this formulation enhances the cellular functions in a human corneal epithelial cell line dramatically compared to the free lacripep, most notably exosome production. Since both lacritin and ELP peptide sequences are humanized and the application to the cornea leaves them external to the body, their use on the cornea has a lower potential risk for immunological consequences. Thus, in the vitreous, the LG, and above the tear film, it may be possible to leverage ELP-mediated strategies to prolong the delivery of bioactive molecules. Future studies are required to quantify the topical pharmacokinetics of lacritin-ELP based therapeutics in preclinical models relevant to humans, and to determine if their therapies at the cornea benefit from combination with contact lenses [103].

Fig. 6.

ELP-mediated assembly enhances lacritin-mediated closure of a defect in the corneal endothelium. (A) Optical density (OD) demonstrates that LS96 lacks a detectable phase separation across a wide range of temperatures, in contrast to S96 ELP alone (shown) and LSI, which assembles larger nanostructures above ~ 19 °C (data not shown). (B) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) confirms that LSI forms nanoparticles with a larger hydrodynamic radius, Rh, compared to LS96 at 37 °C. (C) A 2 mm corneal abrasion was created on the NOD mouse eye, treated with either LSI or LS96, imaged by fluorescein staining, and quantified by a blinded reviewer. LSI treated corneas had almost undetectable defects by 12 h. (D) While both LSI and LS96 contained the lacritin protein fused to a similar MW ELP, the ELP-mediated assembly of LSI nanoparticles significantly decreased the area of the defect at 12 hrs (PcTArea) (p < 0.05, n = 8). This data is adapted by permission from [104].

Pescina and coworkers [151,152] synthesized a library of fluorescently labeled analogue of a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) known as penetratin (RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK) and its reversed sequence by a ‘mimotopic’ approach. CPPs have been highlighted for unusual effects on permeability, cellular internalization, targeting localization, and overcoming lipophilic barriers. Their potential enhancement was explored using an ex vivo porcine corneal penetration. Interestingly, the analytical and experimental analysis revealed that both the amino acid sequence of the parent peptide and its reversed isomer shared physicochemical properties, trans corneal permeability, and effective penetration activity. However, it was mentioned that the parent penetratin showed superior and preferential behavior in permeation and distribution through the corneal layers. The parent CPP followed the intracellular pathway, while the reversed penetratin analogues were dominated by paracellular transport, which was attributed to differential lipid/peptide interactions. This interesting difference illustrates complications that arise when converting natural peptides to unnatural mimotopic, D-backbone chirality, or other peptidomimetic analogues. While they may share some physicochemical properties their natural peptide counterparts, they can lack target-specific biological interactions.

To overcome limitations of conventional antifungals at the cornea, Amit and coworkers [153] used a subtractive proteomic approach to identify natural cornea-specific CPPs shared between ocular samples and the fungus Fusarium solani. Fungal keratitis is the main cause of one-third of cases of corneal blindness. As the cornea represents a protectant barrier against pathogens, ocular abrasions directly promote microbial invasion that contribute to corneal morbidity. Under the assumption that fungal species already produce peptides capable of corneal penetration, a computational approach was used to identify two candidates. They identified two corneal-specific CPPs, VRF005 (KKKWFETWFTEWPKKKK) and VRF007 (KDRPIFQLNTSYWEMGA), which were formulated within a gelatin hydrogel for delivery to primary corneal epithelial cells. They characterized the formulation and validated its cellular targeting and antifungal activity against C. albicans and F. solani. VRF007 sustained an antifungal effect for 24 h, while VRF005 lost activity after four hours. The lower zeta potential for VRF007 was consistent with its lower net charge peptide and extent of aggregation, which were associated with enhanced antimicrobial activity. For VRF005, entrapment within the gelatin-based hydrogel provided better attachment with the corneal epithelial cells and enhanced measures of antifungal effect. It remains to be seen if these proteomics-identified peptides have other applications in their ability to overcome trans-corneal transport; furthermore, future studies should directly compare these to better characterized CPPs, such as penetratin or the TAT peptide as mentioned above.

Under the scope of healing trauma to the corneal surface, Abdel-Naby and coworkers evaluated silk-derived protein (SDP) using a human corneal limbal-epithelial (hCLE) cell model [154]. Different SDP concentrations, 0.2%, 0.4%, and 0.5% were assessed using a cellular scratch closure and flow cytometry assays. While there was not a clear dose–response relationship, 0.4% SDP significantly enhanced the cellular proliferation, migration, and adhesion by 60%, 50%, and 95%, respectively compared to a control. Based on a scratch closure assay, there was a nearly 30% enhancement in the wound healing following 10 h of treatment. While preliminary, this suggests bioactive sequences within SDPs may have applications as topical ophthalmological treatments for corneal injury. Based on past reports of SDPs, the authors suggested their applications arise from thermal/mechanical stability, controlled release, relative biocompatibility, and non-immunogenicity. It remains to be seen which peptides from SDPs are mechanistically responsible for this bioactivity; furthermore, their application to more advanced pre-clinical models will be an important place to assess the immunological effects of topical administration of an insect-derived peptide.

3.4. Subconjunctival

Subconjunctival administration is a depot delivery method for maintaining long residence time. Conjunctiva is a semitransparent membrane that occupies much of the ocular surface. Formed by epithelium, it is primarily distinguished into three parts: the palpebral, bulbar, and fornix. It plays a role in eye lubrication via tear film and mucin production, preventing microorganism permeability, maintaining immune surveillance, and facilitating ocular and systemic drug absorption. The subconjunctival injection forms an in-situ reservoir that can distribute to deeper eye tissues for relatively large volumes up to 0.5 mL. These depots are proposed to favor patient compliance by providing longer residence time, lower frequency administration, and therapeutically effective concentrations. However, the conjunctival blood flow, lymphatic drainage, and porosity of the sclera matrix are among the restrictive barriers that affect the permeation and accelerate the clearance of administrated therapeutics [51,155,156].

Resende’s group [157,158] explored subconjunctival injection of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO), an USFDA-approved growth factor that has neuroprotective effects. This delivery strategy enabled the cargo to target the retinal ganglion cell layer in Wistar Hannover albino rat model with induced unilateral glaucoma. Compared to negative control mice, which received saline injections, the immunostaining signal of EPO protein was still positively identified in the treated group until day 14 following the administration. Thus, even in the absence of a sustained release formulation, subconjunctival administration provides a promising opportunity for retaining protein therapeutics with activity in glaucomatous conditions.

In separate studies, Liang and colleagues [159] developed a self-assembled 3D hydrogel for delivering RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) peptides with hydrophobic N-fluorenyl-9-methoxycarbonyl (FMOC) tails. Interestingly, the FMOC tail configured the RGD peptide into a supramolecular 3D structure that formed a hydrogel. Hydrogels are hydrated networks of cross-linked hydrophilic polymers, which can entrap and release peptides and proteins. However, this hydrogel was directly composed of bioactive amphiphilic peptide-conjugates, without the need for other polymeric matrices. This was administered either to the subconjunctiva, or the anterior chambers into a Japanese rabbit model of anterior ocular disease. Depending on the diffusion coefficient within the hydrogel, the loading and release rates of drug molecules differ. The injection of this hydrogel system denoted rapid response behavior, minimal immunological reactions, favorable biocompatibility, and biodegradation. RGD peptide, a regulating peptide motif that mainly affects cell morphology and survival, displayed selective binding activity and affinity pattern to integrin receptors on the ocular surfaces. Histological analysis showed a satisfactory tissue architecture consistent with inflammation, which disappeared within 7 days of the first injection. These findings demonstrate how supramolecular assembly can be used to generate bioactive materials with durable mean residence times relevant to ocular disease [159–163].

In another study, Rieke and coworkers [164,165] explored the efficacy of the subconjunctival delivery of a fluorescently labeled ovalbumin, a key reference member of the serpin protein family, via a thermosetting gel. This gel has the potential influence on the drug’s miscibility, solubility, efficacy, and safe delivery. This was monitored through release experiments in in vitro models and Brown Norway rats over 14 days. The fluorescence imaging and the spectrofluorimetric assays manifested the ovalbumin content at decreasing levels following the first burst from sclera to choroid and then to retina. The data also revealed no difference in release rates between in vitro and in vivo models, as well as no evidence of infection or adverse reactions. As a strategy for controlled subconjunctival administration, this gel system was proposed to provide a convenient, adjustable, and sustained trans-scleral delivery of proteins to the retina.

Zhou and coworkers [166–168] investigated the local subconjunctival administration of a TNF-α monoclonal antibody, infliximab, in rabbit models with corneal alkali burn. Corneal alkali damage is regarded as a model for serious chemical burns, which are associated with TNF-α cytokine levels, inflammation, neovascularization, delayed healing, optic nerve degeneration, corneal opacification, loss of immune privilege, anatomical defects, and sometimes blindness. Infliximab was loaded in a porous polydimethylsiloxane/polyvinyl alcohol composite delivery system. In humans as well as in vivo models, infliximab binding can downregulate TNF-α-mediated signaling, prevent the progression of immunological complications, and accelerate wound healing. The polymeric delivery formulation of encapsulated infliximab was assessed for stability, safety, and release even after γ radiation sterilization and storage for one year at room temperature. Following 3 months of treatment with an infliximab-loaded and unloaded control, ocular pathology confirmed that the loaded system suppressed early proinflammatory factors, reduced signs of pathological damage, attained neuroprotection, and minimized complications that would require a corneal transplant. Another related study from the same group [169], they evaluated an implanted subconjunctival system for delivering bevacizumab in rabbits with acute alkali injury. Following a 3-month treatment, this microporous delivery system loaded with bevacizumab reversed the burn implications. By the second month, the treatment achieved VEGF neutralization, reduced infiltration of immune cells, and promoted corneal reepithelialization. The microporous delivery platform had the advantage of allowing the well-controlled, consistent daily release of bevacizumab, while its subconjunctival route was effective at targeting the retina and blocking signs of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis.

4. Conclusion and future directions

Clinical successes in ocular drug delivery, such as with the intravitreal administration of anti-VEGF isoforms, demonstrate that localized disease pathology in the eye can be treated with the controlled release of proteins. This opens the door to a broad range of candidate peptide/protein cargoes, which might treat an array of conditions, some of which have been discussed above. To achieve clinically-relevant pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic measures, these strategies require optimization of the therapeutic cargo, the route of administration, and the formulation. In addition to systemic administration, ocular diseases are accessible through extraocular, periocular, and intraocular routes; however, these routes of administration will require a controlled release to reduce the frequency of administration and maintain therapy efficacy. Protein-based delivery systems (elastin-like polypeptides, silk-derived protein systems) are among the cutting-edge formulations useful to optimize ocular pharmaceutics. Their ability to be either fused directly with or associated indirectly with peptide/protein cargoes demonstrates their malleability in the design of drug carriers that overcome barriers to effective therapy. The proper combination of carrier architecture coupled with the correct route of administration is poised to offer viable solutions to challenging conditions of the eye, including macular degeneration, wound healing, dry eye disease, and others. As mentioned above, unmodified biologics have already received USFDA approval, which supports further innovation using their proven routes of administration (intra-vitreal, intra-lacrimal). Bringing new ocular biopharmaceutics to clinical practice will require better formulations that address stability, sustained release, molecular targeting, drug release, biodegradation, immunogenicity, and biocompatibility. Development of these tools has the potential to address unique mechanisms of disease throughout the eye.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by University of Southern California (USC), the Gavin S. Herbert Professorship, National Institutes of Health R01 GM114839, R01 EY026635, and R01 EY030141A1 to JAM, and P30 EY029220 to the USC Ophthalmology Center Core Grant for Vision Research.

Abbreviations:

- LG

Lacrimal gland

- BRB

Blood-retinal barrier

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ELP

Elastin-like polypeptide

- SLP

Silk-like polypeptide

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- PDR

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- BRVO

Branch retinal vein occlusion

- OCT

Optical coherence tomography

- ARPE

Retinal pigment epithelium

- BoNTA

Botulinum toxin

- SS

Sjögren’s syndrome

- CsA

Cyclosporine A

- CypA

Cyclophilin A

- AMD

Age-related macular degeneration

- HN

Humanin

- HCE-T

Human corneal epithelial cell line

- NOD

Non-obese diabetic mice

- CPP

Cell-penetrating peptide

- SDP

Silk-derived protein

- hCLE

Human corneal limbal-epithelial

- rHuEPO

Recombinant human erythropoietin

- RGD

Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid

- FMOC

N-Fluorenyl-9-methoxycarbonyl

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest