Abstract

Background

Diabetic retinopathy is a common complication of diabetes and a leading cause of visual impairment and blindness. Research has established the importance of blood glucose control to prevent development and progression of the ocular complications of diabetes. Concurrent blood pressure control has been advocated for this purpose, but individual studies have reported varying conclusions regarding the effects of this intervention.

Objectives

To summarize the existing evidence regarding the effect of interventions to control blood pressure levels among diabetics on incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy, preservation of visual acuity, adverse events, quality of life, and costs.

Search methods

We searched several electronic databases, including CENTRAL, and trial registries. We last searched the electronic databases on 3 September 2021. We also reviewed the reference lists of review articles and trial reports selected for inclusion.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which either type 1 or type 2 diabetic participants, with or without hypertension, were assigned randomly to more intense versus less intense blood pressure control; to blood pressure control versus usual care or no intervention on blood pressure (placebo); or to one class of antihypertensive medication versus another or placebo.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of review authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of records identified by the electronic and manual searches and the full‐text reports of any records identified as potentially relevant. The included trials were independently assessed for risk of bias with respect to outcomes reported in this review.

Main results

We included 29 RCTs conducted in North America, Europe, Australia, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East that had enrolled a total of 4620 type 1 and 22,565 type 2 diabetic participants (sample sizes from 16 to 4477 participants). In all 7 RCTs for normotensive type 1 diabetic participants, 8 of 12 RCTs with normotensive type 2 diabetic participants, and 5 of 10 RCTs with hypertensive type 2 diabetic participants, one group was assigned to one or more antihypertensive agents and the control group to placebo. In the remaining 4 RCTs for normotensive participants with type 2 diabetes and 5 RCTs for hypertensive type 2 diabetic participants, methods of intense blood pressure control were compared to usual care. Eight trials were sponsored entirely and 10 trials partially by pharmaceutical companies; nine studies received support from other sources; and two studies did not report funding source.

Study designs, populations, interventions, lengths of follow‐up (range less than one year to nine years), and blood pressure targets varied among the included trials.

For primary review outcomes after five years of treatment and follow‐up, one of the seven trials for type 1 diabetics reported incidence of retinopathy and one trial reported progression of retinopathy; one trial reported a combined outcome of incidence and progression (as defined by study authors). Among normotensive type 2 diabetics, four of 12 trials reported incidence of diabetic retinopathy and two trials reported progression of retinopathy; two trials reported combined incidence and progression. Among hypertensive type 2 diabetics, six of the 10 trials reported incidence of diabetic retinopathy and two trials reported progression of retinopathy; five of the 10 trials reported combined incidence and progression.

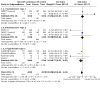

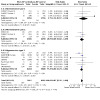

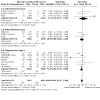

The evidence supports an overall benefit of more intensive blood pressure intervention for five‐year incidence of diabetic retinopathy (11 studies; 4940 participants; risk ratio (RR) 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.73 to 0.92; I2 = 15%; moderate certainty evidence) and the combined outcome of incidence and progression (8 studies; 6212 participants; RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.89; I2 = 42%; low certainty evidence). The available evidence did not support a benefit regarding five‐year progression of diabetic retinopathy (5 studies; 5144 participants; RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.12; I2 = 57%; moderate certainty evidence), incidence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, clinically significant macular edema, or vitreous hemorrhage (9 studies; 8237 participants; RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.04; I2 = 31%; low certainty evidence), or loss of 3 or more lines on a visual acuity chart with a logMAR scale (2 studies; 2326 participants; RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.63 to 2.08; I2 = 90%; very low certainty evidence). Hypertensive type 2 diabetic participants realized more benefit from intense blood pressure control for three of the four outcomes concerning incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy.

The adverse event reported most often (13 of 29 trials) was death, yielding an estimated RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.00; 13 studies; 13,979 participants; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). Hypotension was reported in two trials, with an RR of 2.04 (95% CI 1.63 to 2.55; 2 studies; 3323 participants; I2 = 37%; low certainty evidence), indicating an excess of hypotensive events among participants assigned to more intervention on blood pressure.

Authors' conclusions

Hypertension is a well‐known risk factor for several chronic conditions for which lowering blood pressure has proven to be beneficial. The available evidence supports a modest beneficial effect of intervention to reduce blood pressure with respect to preventing diabetic retinopathy for up to five years, particularly for hypertensive type 2 diabetics. However, there was a paucity of evidence to support such intervention to slow progression of diabetic retinopathy or to affect other outcomes considered in this review among normotensive diabetics. This weakens any conclusion regarding an overall benefit of intervening on blood pressure in diabetic patients without hypertension for the sole purpose of preventing diabetic retinopathy or avoiding the need for treatment for advanced stages of diabetic retinopathy.

Keywords: Humans; Antihypertensive Agents; Antihypertensive Agents/therapeutic use; Blood Pressure; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/complications; Diabetic Retinopathy; Diabetic Retinopathy/complications; Diabetic Retinopathy/epidemiology; Diabetic Retinopathy/prevention & control; Hypertension; Hypertension/complications; Hypertension/drug therapy; Macular Edema; Macular Edema/etiology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Blood pressure control for diabetic retinopathy

Review question

Does blood pressure control prevent diabetic retinopathy or slow its progression?

Background

Diabetes is characterized by high levels of blood glucose (sugar circulating in the blood) and is classified as either type 1 or type 2, depending on the underlying cause of increased blood glucose. A common complication in people with diabetes is diabetic retinopathy, often called 'diabetic eye disease,' which affects the blood vessels in the back of the eye. Diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of poor vision and blindness worldwide among adults of working age. Control of blood glucose reduces the risk of diabetic retinopathy and prevents worsening of the condition once it develops. Simultaneous treatment to reduce blood pressure among diabetics has been suggested as another approach to reduce the risks of development and worsening of diabetic retinopathy below the risks achieved by blood glucose control.

Study characteristics

We found 29 randomized controlled trials (a type of study where participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more treatment groups), conducted primarily in North America and Europe, looking at the effects of several methods to lower blood pressure in 4620 type 1 and 22,565 type 2 diabetics, with 16 to 4477 participants in individual trials. The treatment and follow‐up periods in these trials ranged from less than one year to nine years. Eight trials were funded in full by one or more drug companies. Ten other trials had received drug company support, usually in the form of study medications. The remaining 11 studies were conducted with support from government‐sponsored grants and institutional support or did not report funding source. The evidence is current to September 2021.

Key results

Overall, the evidence from 19 trials in which participants were treated for 5 years or longer provided modest support for lowering blood pressure to prevent diabetic retinopathy. However, lowering blood pressure did not keep diabetic retinopathy from worsening once it had developed, or prevent advanced stages of diabetic retinopathy that required treatment of the affected eyes. The evidence favored control of blood pressure for hypertensive type 2 diabetics for more outcomes than favored blood pressure lowering among participants with normal blood pressure. Treatment to reduce the blood pressure of people with diabetes is warranted for other health reasons, but the available evidence does not justify reduction of blood pressure in diabetics with normal blood pressures solely to prevent or slow diabetic retinopathy.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence was low to moderate based on the reported information because some studies did not report all of their prespecified outcomes, and results from different studies were not always consistent.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Blood pressure intervention/intensive blood pressure intervention compared with placebo/standard blood pressure intervention for diabetic retinopathy.

| Blood pressure intervention/intensive blood pressure intervention compared with placebo/standard blood pressure intervention for diabetic retinopathy | |||||

|

Patient or population: type 1 or type 2 diabetics Settings: diabetes and ophthalmology clinics Intervention: blood pressure intervention/intensive blood pressure intervention (antihypertensive medication or intense antihypertensive medication, or intense lifestyle intervention and medication) Comparison: placebo/standard blood pressure intervention (antihypertensive medication) | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with no (or less) control by type of diabetes | Risk with blood pressure intervention/intensive blood pressure intervention | ||||

| Incidence of retinopathy by 5 years | Type 1 normotensive | ||||

| 306 per 1000 | 251 per 1000 (173 to 243) | RR 0.82 (0.69 to 0.97) | 1421 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Type 2 normotensive | |||||

| 290 per 1000 | 252 per 1000 (189 to 257) | RR 0.87 (0.75 to 1.02) | 1545 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Type 2 hypertensive | |||||

| 209 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (89 to 154) | RR 0.75 (0.57 to 0.98) | 1974 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Overall | |||||

| 264 per 1000 | 216 per 1000 (193 to 243) | RR 0.82 (0.73 to 0.92) | 4940 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Progression of retinopathy by 5 years | Type 1 normotensive | ||||

| 130 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (110 to 173) | RR 1.03 (0.82 to 1.29) | 1905 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Type 2 normotensive | |||||

| 237 per 1000 | 239 per 1000 (187 to 311) | RR 1.01 (0.78 to 1.30) | 2460 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Type 2 hypertensive | |||||

| 192 per 1000 | 140 per 1000 (71 to 148) | RR 0.73 (0.51 to 1.06) | 779 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Overall | |||||

| 191 per 1000 | 179 per 1000 (149 to 214) | RR 0.94 (0.78 to 1.12) | 5144 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Combined incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy by 5 years | Type 1 normotensive | ||||

| 378 per 1000 | 227 per 1000 (91 to 207) | RR 0.60 (0.40 to 0.91) | 223 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 | |

| Type 2 normotensive | |||||

| 191 per 1000 | 174 per 1000 (101 to 251) | RR 0.91 (0.58 to 1.44) | 1743 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 | |

| Type 2 hypertensive | |||||

| 202 per 1000 | 156 per 1000 (104 to 139) | RR 0.77 (0.67 to 0.89) | 4246 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Overall | |||||

| 203 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (138 to 181) | RR 0.78 (0.68 to 0.89) | 6212 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 | |

| Incidence of PDR/CSME/VH by 5 years | Type 1 normotensive | ||||

| 105 per 1000 | 109 per 1000 (85 to 139) | RR 1.04 (0.81 to 1.33) | 2054 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,3 | |

| Type 2 normotensive | |||||

| 165 per 1000 | 164 per 1000 (137 to 194) | RR 0.99 (0.83 to 1.18) | 2460 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,3 | |

| Type 2 hypertensive | |||||

| 95 per 1000 | 73 per 1000 (73 to 90) | RR 0.77 (0.62 to 0.95) | 3723(4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,3 | |

| Overall | |||||

| 82 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (67 to 85) | RR 0.92 (0.82 to 1.04) | 8237 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,3 | |

| Visual acuity (loss of 3 lines or more) by 5 years | 184 per 1000 | 211 per 1000 (116 to 382) | RR 1.15 (0.63 to 2.08) | 2326 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2,4 |

| Adverse events—all‐cause mortality | Type 1 normotensive | ||||

| 8 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (6 to 25) | RR 1.16 (0.57 to 2.36) | 3608 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Type 2 normotensive | |||||

| 57 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (29 to 58) | RR 0.86 (0.62 to 1.19) | 2599 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Type 2 hypertensive | |||||

| 76 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (56 to 76) | RR 0.86 (0.74 to 1.01) | 7772 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Overall | |||||

| 54 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (39 to 53) | RR 0.87 (0.76 to 1.00) | 13,979 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | |

| Adverse events—hypotension | 63 per 1000 | 130 per 1000 (103 to 162) | RR 2.04 (1.63 to 2.55) | 3323 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CSME: clinically significant macular edema; PDR: proliferative diabetic retinopathy; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; VH: vitreous hemorrhage | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Downgraded for risk of bias (−1). 2Downgraded for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals (−1). 3Downgraded for heterogeneity (−1). 4Downgraded for inconsistency (−1).

Background

Description of the condition

Introduction and epidemiology

Diabetic retinopathy is a complex disorder of the retinal vasculature that is characterized by increased vascular permeability, retinal ischemia and edema, and new blood vessel formation. The National Eye Institute has reported age‐related macular degeneration, cataracts, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy to be the leading causes of visual impairment and blindness among Americans older than 40 years (EDPRG 2004a). Similar findings have been reported for older Americans over the age of 75 years (Desai 2001), and from other epidemiologic studies from Western Europe (Buch 2004; Grey 1989; Krumpaszky 1999; Rosenberg 1996).

Globally, diabetes mellitus is a significant public health problem. Some predictions estimate that the worldwide prevalence of diabetes will exceed 366 million people by 2030 (Wild 2004). Diabetic retinopathy is a common complication among individuals with diabetes and an important cause of loss of vision (Sivaprasad 2012). A diabetic individual has a three‐fold increased risk of blindness compared with the general population (Hayward 2002). The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 25.8 million people in the US were living with diabetes in 2010 (CDC 2011). In the US alone, it is estimated that 4.1 million adults over the age of 40 have diabetic retinopathy (any level of severity), and that 899,000 adults have vision‐threatening diabetic retinopathy (EDPRG 2004b). Among Americans with type 1 diabetes, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy of any severity is 74.9% and 82.3% in black and white persons respectively; the prevalence of vision‐threatening (severe non‐proliferative and proliferative) retinopathy is 30% and 32.2% (EDPRG 2004c). The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among type 1 and type 2 diabetics in Wales was recently reported as 56% and 30.3%, respectively (Thomas 2014). People with impaired visual acuity or legal blindness secondary to diabetic retinopathy face enormous challenges in pursuing activities of daily life. Visual impairment is defined as best‐corrected visual acuity worse than 20/40 in the better‐seeing eye; blindness is defined as best‐corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or worse in the better‐seeing eye as measured on the original Bailey‐Lovie or modified Bailey‐Lovie (also known as the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS)) visual acuity chart or other charts that use a logMAR scale.

The duration of diabetes and the severity of hyperglycemia are major risk factors associated with the development (incidence) and progression of diabetic retinopathy (DCCT 1993; DRS10 1985; ETDRS18 1998; Harris 1998; Klein 1984a; Klein 1984b; Klein 1988; Krakoff 2003; Kullberg 2002; Leske 2003; Porta 2001; UKPDS33 1998; van Leiden 2003; Zhang 2001). After retinopathy develops, persistent hyperglycemia has been reported to be a more important factor than duration of diabetes for progression of the disease (ETDRS18 1998; Giuffre 2004).

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, DCCT, and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) demonstrated lower incidence and slower progression of diabetic retinopathy with tight blood glucose control (DCCT 1993; UKPDS33 1998). The Diabetic Retinopathy Study, DRS2 1978; DRS5 1981; DRS8 1981, and the ETDRS, ETDRS1 1985; ETDRS9 1991, demonstrated a decrease in the progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema with more than 1200 applications of 'pan‐retinal' (for proliferative retinopathy) or with 'focal' (for macular edema) laser photocoagulation. However, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy observed in recent epidemiologic studies conducted after the DCCT and UKPDS continued to be high (EDPRG 2004b; EDPRG 2004c). Recently, investigators participating in trials conducted by the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCRnet) have reported that other treatments, either alone or in combination with laser treatment, can slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy (DRCR.net 2010). These studies strongly support treatment of diabetic retinopathy to reduce loss of vision. Nevertheless, findings from all studies reinforce the need to evaluate the role of risk factors and to intervene on those that are modifiable in order to decrease the prevalence and severity of diabetic retinopathy.

Risk factors that have been reported for diabetic retinopathy include hypertension (Klein 1989a; Klein 1989b; Leske 2003; Tapp 2003; UKPDS38 1998), hypercholesterolemia (Chew 1996; Klein 2002b; van Leiden 2002), abdominal obesity and elevated body mass index (van Leiden 2002; van Leiden 2003; Zhang 2001), alcohol intake (Giuffre 2004), younger age at onset (Krakoff 2003; Kullberg 2002; Porta 2001), smoking, and ancestry (Keen 2001; Moss 1996). Age and ancestry are not modifiable, but other risk factors suggest possible interventions.

Presentation and diagnosis

Diabetic retinopathy progresses sequentially from a mild non‐proliferative stage to a severe proliferative disorder. Increased retinal vascular permeability occurs early, at the stage of mild non‐proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR). Moderate and severe NPDR are characterized by vascular closure, which results in impaired retinal perfusion (ischemia).

Diabetic retinopathy is typically diagnosed during ophthalmoscopy. Fundus photographs and fluorescein angiograms may be used to monitor progression. Signs of NPDR include microaneurysms, intraretinal hemorrhages, and occasional 'cotton wool spots' caused by closure of small retinal arterioles, resulting in localized ischemia and edema, with consequent damage to nerve fibers leading to reduced axonal transport. Signs of increasing ischemia include extensive intraretinal hemorrhages, venous abnormalities such as wide variations in caliber ('beading') and looping ('reduplication'), capillary non‐perfusion, and intraretinal microvascular abnormalities. Severe NPDR, also known as pre‐proliferative retinopathy, is diagnosed when these changes progress to predefined thresholds.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is characterized by neovascularization, which is the growth of abnormal blood vessels in response to severe ischemia. The new vessels grow into the vitreous and are often seen at the optic disc (NVD) and elsewhere in the retina (NVE); they are prone to bleeding, which results in vitreous hemorrhage (VH) and vision loss. Furthermore, these vessels may undergo fibrosis and contraction and, along with other fibrous proliferation, may lead to epiretinal membrane formation, vitreoretinal traction bands, retinal tears, and either tractional or rhegmatogenous retinal detachments (i.e. those due to a retinal hole or tear). It is said that PDR is at the high‐risk stage when NVE that occupy a total area of 0.5 optic disc area or more in size throughout the retina are accompanied by pre‐retinal or vitreous hemorrhage, or when NVD occupy an area greater than or equal to about one‐third disc area, even in the absence of VH, or when NVD of any size are accompanied by VH. People in the 'high risk' stage of PDR who do not receive prompt pan‐retinal laser treatment have a 30% to 50% probability of progressing to severe visual acuity loss and blindness (less than 5/200 best‐corrected visual acuity) in three years (DRS8 1981; ETDRS10 1991; ETDRS12 1991).

Increased retinal vascular permeability, which can occur at any stage of diabetic retinopathy, may result in retinal thickening (edema) and lipid deposits (hard exudates). Retinal thickening, hard exudates, or both that occur at or within 500 microns (approximately one‐third an optic disc diameter) of the center of the macula, and which therefore threaten, or actually cause, loss of central visual acuity, are referred to as clinically significant macular edema.

The major reasons for vision loss in diabetic retinopathy include macular edema, macular capillary non‐perfusion (which can be demonstrated by fluorescein angiography), VH, distortion or tractional detachment of the retina (PPP 2019), and neovascular glaucoma (new blood vessels in the iris), which is usually associated with very late‐stage PDR (Fong 2004).

Pathogenesis

Several biochemical pathways have been investigated for the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Apart from the well‐documented role of chronic hyperglycemia, none of the other biochemical pathways has been shown conclusively to be relevant (Frank 2004).

Although the exact mechanism for the pathogenesis of hypertensive damage in eyes with diabetic retinopathy is unknown, scientists have hypothesized that an increase in blood pressure damages the retinal capillary endothelial cells (Klein 2002a). In eyes with diabetic retinopathy, chronic hyperglycemia leads to endothelial cell damage, pericyte loss, and breakdown of the blood‐retinal barrier. Such changes to the structure of the microvasculature lead to dysregulation of retinal perfusion, thereby making eyes with diabetic retinopathy more susceptible to hyperperfusion damage from hypertension (Gillow 1999).

Description of the intervention

The current standard of care for the prevention and treatment of diabetic retinopathy consists of strict glycemic control and regular ophthalmologic screening for diabetic retinopathy among diabetics, the use of focal laser treatment or intravitreal anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor injections for diabetic macular edema, and the use of pan‐retinal scatter laser photocoagulation for PDR (Smith 2011; Virgili 2014). Strict blood pressure control has been recommended as part of the standard of care for diabetics, because of its known beneficial effect on the prevention of cardiovascular events, stroke, and nephropathy rather than for its effect on diabetic retinopathy (Hansson 1998; HOPESI 2000).

How the intervention might work

Blood pressure control may be beneficial in preventing the development or slowing the progression of diabetic retinopathy by reducing the damage to endothelial cells, blood vessels, and surrounding tissues from hyperperfusion. Diabetic retinopathy leads to endothelial cell dysfunction, loss of pericytes, and breakdown of the blood‐retinal barrier. Hypertension may cause additional vascular damage because of shearing that occurs with hyperperfusion. Blood pressure control may prevent hyperperfusion and decrease the likelihood of shearing damage to the blood vessels from hypertension.

Why it is important to do this review

Diabetic retinopathy remains an important cause of vision loss even with good blood glucose control (ADA 1998; Ferris 1993). At the end of the DCCT, with participant follow‐up of 6.5 ± 1.6 years (mean ± standard error), 10% of type 1 diabetic patients in the intensive glycemic control group had developed diabetic retinopathy despite strict glycemic control (Zhang 2001). Similarly, in the UKPDS, tight blood glucose control decreased but did not eliminate the risk of diabetic retinopathy (UKPDS33 1998). Diabetic retinopathy is a substantial public health problem (Zhang 2010). Because studies of retinal physiology suggest a role for blood pressure in pathological changes in diabetic retinopathy (Sjølie 2011), a systematic review of the effectiveness of blood pressure control with respect to diabetic retinopathy was proposed (Sleilati 2009).

The beneficial health effects on multiple organ systems of control of blood pressure among people with hypertension, including those with diabetes mellitus, has been well‐established during decades of randomized trials. The effects regarding diabetic retinopathy and complications were addressed in the original version of this review (Do 2015a); however, there was limited evidence of effects from randomized trials in which participants had been followed for five years or longer. This update includes several studies that published findings after the original systematic review was completed. The effects of interventions to lower blood pressure among individuals who already have normal or near normal blood pressure and diabetes mellitus were certain. It was thus important to re‐examine the evidence of the effects of interventions to control blood pressure on diabetic retinopathy that has accrued to date.

Objectives

The primary aim of this review was to summarize the existing evidence regarding the effect of interventions to control blood pressure levels among diabetics on incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy, preservation of visual acuity, adverse events, quality of life, and costs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included RCTs in which participants had a diagnosis of either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, irrespective of age, gender, ethnicity, ancestry, status regarding blood pressure or its treatment, or diabetic retinopathy status.

Types of interventions

We included trials in which:

participants assigned to more intense blood pressure control, alone or in combination with other interventions, were compared with participants assigned to less intense blood pressure control;

participants assigned to blood pressure control were compared with participants assigned to usual care or no intervention on blood pressure (placebo);

participants assigned to antihypertensive agents versus placebo;

participants assigned to treatment with one class of antihypertensive agent were compared with participants assigned to another class of antihypertensive agent.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of retinopathy, defined as mild non‐proliferative or more severe diabetic retinopathy, i.e. a retinopathy score on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) final scale of 35 or greater based on evaluation of stereoscopic color fundus photographs of eyes of participants who did not have retinopathy at baseline (ETDRS10 1991).

Progression of retinopathy, defined as a two‐step or greater progression from baseline on the ETDRS final scale based on evaluation of stereoscopic color fundus photographs of eyes of participants who had diabetic retinopathy at baseline (ETDRS10 1991).

We post hoc added a composite outcome of incidence or progression of retinopathy as reported by several included studies. Some trials used other methods or scales to define retinopathy and its progression; we assessed comparability of other scales with the ETDRS scale and classified changes similar to those measured on the ETDS scale with those given above.

We placed no restrictions on study selection based on the length of follow‐up of participants for primary or secondary outcomes. However, we judged follow‐up for less than one year to be inadequate for the outcomes relevant to this review because of the rate of development and progression of diabetic retinopathy and the time required for antihypertensive agents to affect the microvasculature.

We specified five years as the primary outcome period of interest in the protocol for this review; however, few trials reported outcomes for this exact time interval. We thus analyzed and reported the primary outcomes reported for mean participant follow‐up of four to six years after enrollment to estimate five‐year outcomes. We also analyzed incidence and progression of retinopathy reported at shorter (less than three years) and longer (seven or more years) follow‐up times from a few trials.

Secondary outcomes

We assessed the secondary outcomes at follow‐up times as reported above.

Post hoc: incidence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), clinically significant macular edema (CSME), or vitreous hemorrhage (VH) using the criteria described in the included trials.

Decrease in visual acuity by 3 or more lines in both eyes on a logMAR chart. A 3‐line decrease corresponds to a doubling of the minimum angle of resolution.

We also compared classes of antihypertensive medications with respect to these same primary and secondary outcomes.

Adverse effects

We summarized adverse effects related to blood pressure control as reported by the included studies, with a focus on death, systemic effects such as hypotension or hyperkalemia, and adverse ocular events. We did not conduct a search for adverse events reported in RCTs that did not report retinopathy outcomes or in non‐randomized studies (not included in this review).

Quality of life

We summarized vision‐related quality of life data reported by the included studies, as measured using the National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire 25, Mangione 2001, or another validated vision‐related scale. When sufficient data become available, comparisons of scores between treatment groups may be of interest.

Economic data

We summarized cost or cost‐effectiveness data reported by the included trials. When sufficient data become available, there may be interest in comparisons of costs of different treatment strategies that yield similar benefits with respect to retinopathy outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

To identify potentially eligible studies for the current version of this review, the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist searched the following electronic databases for RCTs. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The electronic databases were last searched on 3 September 2021.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 9) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 3 September 2021) (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 3 September 2021) (Appendix 2).

Embase.com (1947 to 3 September 2021) (Appendix 3).

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature database (LILACS) (1982 to 3 September 2021) (Appendix 4).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/; searched 3 September 2021) (Appendix 5).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform; searched 3 September 2021) (Appendix 6).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of reports from the included trials and related reviews to find additional potentially eligible studies. We did not conduct manual searches of conference abstracts for this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all records identified by the electronic and manual searches. We classified each record as 'definitely relevant,' 'possibly relevant,' or 'definitely not relevant.' We obtained the full‐text reports corresponding to records classified as 'definitely relevant' or 'possibly relevant' by at least one review author. Two review authors independently classified studies based on descriptions in the full‐text reports as 'include,' 'exclude,' 'uncertain,' or 'ongoing.' Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. For reports classified as 'uncertain' or 'ongoing,' that is those where information was unclear or insufficient to permit classification, we contacted the trial investigators for additional information or for clarification. We documented studies labeled as 'exclude' and the reasons for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table; studies labeled as 'ongoing' in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table; and studies with insufficient publicly available information in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. For reports in languages not read by the review authors, we consulted with translators to assist with screening for eligibility; no full‐text translations were required.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data describing study and participant characteristics, data sufficient to judge risk of bias, and data needed to record outcomes from the included trials onto data collection forms developed by Cochrane Eyes and Vision. We extracted details of study methods, participants, interventions, and outcomes from all included trials. We recorded cost, quality of life, and adverse outcome data when reported. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or through consultation with a third review author when members of a pair disagreed. We contacted primary investigators to obtain outcome data not reported. One review author entered data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020); a second review author verified the entries. We followed the same procedures when we updated the review.

One review author made a final check of the review in June 2014 to confirm that all extracted data had been entered into Review Manager 5 and that entries agreed with the full‐text reports and supplemental information provided by study investigators. During that process, we found additional data regarding outcomes for a few studies. The review author extracted the newly found data; a second review author confirmed all data extracted, entered the data into Review Manager 5, and updated the analyses with the added data included in the original review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Pairs of review authors independently assessed the included trials for risk of bias according to methods described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed risk of bias for the following domains.

Generation of allocation sequence

Allocation concealment before randomization

Masking of caregivers, participants, and outcome assessors, separately for primary and secondary outcomes of this review

Methods used to address incomplete or missing outcome data, separately for primary and secondary outcomes of this review

Selective outcome reporting

Other sources of bias

We classified each trial as having 'low,' 'high,' or 'unclear' risk of bias with respect to each domain.

We contacted trial investigators for clarification whenever information relevant to the risk of bias domains was reported unclearly or was missing from the published reports. We attempted to assess evidence of reporting bias by comparing protocols and publications on trial design, where available, with publications of results. We were able to access protocols for only a few of the trials included in the review. For trials without a publicly available protocol, we assessed reporting bias by comparing the results section and the methods sections of published trial reports. Again, any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

Because all outcomes considered for this review were dichotomous, we estimated and reported risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for primary and secondary outcomes (incidence of retinopathy, progression of retinopathy, combined incidence and progression of retinopathy, visual acuity decrease by 3 or more lines, and progression to PDR, CSME, or VH) and for adverse events. Whenever the 95% CI for an RR did not include 1, we interpreted the comparison as yielding a statistically significant result despite the many comparisons reported in this review. We did not estimate treatment effects for quality of life outcomes or costs, but rather summarized these data by study and treatment group as reported by the trial investigators.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual trial participant.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study investigators for missing information or for clarification as needed. When there was no response, we used the available data. We did not include studies that had reported no data for diabetic retinopathy outcomes. We did not impute data for the purposes of this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity across included trials using participant characteristics, details of interventions, duration of follow‐up, risk of bias, and definitions of outcomes. We examined statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test and I2 values; we considered an I2 greater than 50% as indicative of substantial statistical heterogeneity. We also considered consistency among estimates with respect to direction and magnitude and the extent of overlap among confidence intervals from individual studies.

Assessment of reporting biases

For selective outcome reporting, we compared the protocols of studies, when available, with the primary published report. We compared the outcomes specified in the methods section and the outcomes reported in the results section of published reports when a protocol was not available. We planned to use asymmetry of funnel plots as an indicator of potential publication bias; however, fewer than 10 studies reported most individual outcomes, thereby reducing the utility of this approach. In future updates when meta‐analyses include 10 or more studies, we plan to assess potential publication bias by examining funnel plots.

Data synthesis

Due to methodological, clinical, and statistical heterogeneity among included trials, we used a random‐effects model in meta‐analyses to estimate five‐year outcomes. We based meta‐analyses of outcomes on a fixed‐effect model whenever data were available from only two studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses according to baseline level of metabolic control, as determined using glycated hemoglobin, and baseline severity of diabetic retinopathy whenever sufficient data were available. However, none of the publications from the trials reported outcomes by baseline glycated hemoglobin levels or baseline retinopathy. Post hoc, but before retrieval of full‐text reports of studies identified as 'include' or 'uncertain,' we agreed to present outcomes separately for trials that enrolled participants with type 1 and type 2 diabetes because of the different etiologies and characteristics of patients with these conditions. We also decided to present outcomes separately for participants who were hypertensive at baseline for comparison with those who were normotensive or whose hypertension was controlled by treatment at baseline because of potential differences in benefits versus risks of intervention on blood pressure in these subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of exclusion of studies with high risk of attrition bias, unpublished studies, and industry‐funded studies. We did not conduct any of the prespecified sensitivity analyses as it was not possible to assess attrition in all included studies; many studies had industry support; and no data were included from unpublished studies.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We prepared a summary of findings table and assessed the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE approach, which considers five factors (study limitations, indirectness of evidence, inconsistency of results, imprecision, and publication bias). We included the following outcomes at five years in the summary of findings table.

Incidence of retinopathy, defined as mild non‐proliferative or more severe diabetic retinopathy, i.e. a retinopathy score on the ETDRS final scale of 35 or greater based on evaluation of stereoscopic color fundus photographs of eyes of participants who did not have retinopathy at baseline (ETDRS10 1991). Otherwise, we incorporated data based on the methods used by study investigators.

Progression of retinopathy, defined as a two‐step or greater progression from baseline on the ETDRS final scale based on evaluation of stereoscopic color fundus photographs of eyes of participants who had diabetic retinopathy at baseline (ETDRS10 1991).

Combined incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy based on reports from individual studies, many of which did not report separately on incidence and progression.

Decrease in visual acuity by 3 or more lines in both eyes on a logMAR chart or as reported. A 3‐line decrease (logMAR change of 0.3) corresponds to a doubling of the minimum angle of resolution.

Incidence of PDR, CSME, or VH using the criteria described in the included trials.

Adverse effects: death.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The electronic database searches for the previous version of the review as of 25 April 2014 yielded 15 included RCTs (62 reports), three ongoing studies, and three studies awaiting classification (Do 2015a). We performed three updated searches on 7 June 2019, 21 May 2020, and 3 September 2021; we retrieved a total of 8222 records after removal of duplicates. In total, we screened 8222 records of which 8187 were excluded. We screened 35 full‐text reports of which 21 were excluded; the reasons for exclusion of full‐text reports are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

In this update, we included four trials that had been excluded from the original review, and two more trials that were awaiting assessment at the time of the original review and from which outcomes subsequently had been published (Figure 1). Overall, we included 85 reports (29 RCTs) and excluded 25 reports. We continue to await classification of one trial from the previous version of the review pending receipt of information from a study investigator (ABCD‐2V (2)).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

A detailed description of each individual included trial is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table. To facilitate comparisons of trials, we subgrouped them into those that enrolled only participants who had type 1 diabetes mellitus; those that enrolled only participants who had type 2 diabetes mellitus and were defined by the study investigators either as normotensive or blood pressure controlled by medication; or those that enrolled only participants who had type 2 diabetes mellitus and were defined as hypertensive by the study investigators. The characteristics of study participants and the design features of individual studies within these subgroups are summarized for comparison in Table 2 and Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, and Table 6 and Table 7, respectively, with studies in each subgroup ordered by year of initiation or year of the earliest report from the trial.

1. Baseline characteristics of type 1 diabetic participants, by date trial was initiated.

| Characteristic | Larsen | Chase | EUCLID | DIRECT | RASS* | AdDIT | |

| DIRECT Prevent 1 | DIRECT Protect 1 | ||||||

| Number randomized | 20 | 16 | 530 | 1421 | 1905 | 285 | 443 |

| Age, years (mean) | 30 | 21 | 34 | 30 | 32 | 30 | 12.4 |

| Women, % | 20 | 25 | 35 | 43 | 42 | 54 | 46 |

| White, % | na | na | na | 97 | 98 | 98 | na |

| Diabetes duration, years (mean) | 18 | 14.1 | 14.5 | 6.7 | 11.0 | 11.2 | 5 |

| Current smoker, % | na | na | na | 26 | 26 | na | 0.7 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg (mean) | 127 | 115 | 123 | 116 | 117 | 120 | 116 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg (mean) | 79 | 78 | 81 | 72 | 74 | 70 | 66 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (mean) | 9.2 | 8.4 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.4 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (mean) | na | na | 24.7 | 24.0 | 24.6 | 25.7 | 21.3 |

| Number assessed for diabetic retinopathy | 20 | 16 | 354 | 1421 | 1905 | 223 | 443 |

| ≤ 20/20 or microaneurysms only, % | 100 | 44 | 38 | 100 | 49 | 34 | 100 |

| 31 to 37, mild NPDR, % | 0 | 25 | 41 | 0 | 42 | 58 | 0 |

| 41 to 53, moderate/severe NPDR, % | 0 | 25 | 11 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| > 53, PDR or PRP, % | 0 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*Data shown for RASS are for participants analyzed for retinopathy outcomes.

na, information not found in study publications NPDR, non‐proliferative diabetic retinopathy PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy PRP, panretinal photocoagulation

2. Design features of included trials for type 1 diabetics, by date trial initiated or earliest publication.

| Design feature | Larsen | Chase | EUCLID | DIRECT | RASS | AdDIT | |

| DIRECT Prevent 1 | DIRECT Protect 1 | ||||||

| Year trial initiated | 1985 | 1993a | 1997a | 2001 | 2001 | 2002a | 2009 |

|

Definition of "hypertension," SBP/DBP, mmHg |

> 150/90 | ≥ 141/90 | > 155/90 | > 130/85 | > 130/85 | > 135/85 or antihypertensive medication | na |

| Primary outcome, parent trial | Blood‐retinal barrier leakage |

AER | AER | Diabetic retinopathy | Diabetic retinopathy | Nephropathy |

ACR |

| Type of interventions: | |||||||

| More control | ACEi | ACEi | ACEi | ARB | ARB | ARB or ACEi | ACEi |

| Less control | None | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo |

| Blood pressure target: | |||||||

| More control | Reduce MABP by ≥ 5 mmHg | None | DBP < 75 mmHg | None | None | < 130/80, mmHg | na |

| Less control | None | None | DBP < 75 mmHg | None | None | < 130/80, mmHg | na |

| Other randomized intervention(s) | None | None | None | None | None | None | Statin vs placebo |

| Method of DR diagnosis/classification | Photos read by masked observer. | Fundus exam + photos read by ophthalmologist. | Photos read centrally.b | Photos read centrally.c | Photos read centrally.c | Photos read centrally.d | Photos read centrally. |

aDate of earliest publication. bAarhus, Denmark. cImperial College (London) Retinopathy Grading Centre. dWisconsin Ocular Epidemiology Reading Center.

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor ACR, albumin/creatinine ratio AER, albumin ejection rate ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker DBP, diastolic blood pressure, mmHg DR, diabetic retinopathy MABP, mean arterial blood pressure, mmHg na, information not found in study publications NPDR, non‐proliferative diabetic retinopathy SBP, systolic blood pressure, mmHg

3. Baseline characteristics of normotensive or treated hypertensive type 2 diabetic participants, by date trial initiated or earliest publication.

| Characteristic | ABCD (1) | Ravid 1993 | Medi‐Cal | ABCD‐2V (1) | Pradhan | ACCORD Eye | DIRECT Protect 2 | J‐EDIT | Knudsen | ROADMAP | Wang | Zhao |

| Number randomized | 480 | 108 | 358 | 129 | 40 | 1590 | 1905 | 1173 | 24 | 4477 | 317 | 224 |

| Age, years (mean) | 59 | 44 | 55 | 56 | 51 | 61 | 57 | 72 | 61 | 58 | 64 | 66 |

| Women, % | 46 | 55 | 72 | 32 | 54 | 46 | 50 | 54 | 42 | 51 | 44 | 65 |

| White, % | 74 | na | 42 | 75 | na | 69 | 96 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| DM duration, years (mean) | 9 | 6.8 | 9.7 | 7.6 | 11 | 10 | 8.8 | 17 | 11 | 6.3 | 10.5 | 7.2 |

| Current smoker, % | 13 | na | 14 | 8 | na | 13 | 15 | 54 | 29 | 16 | na | 8 |

| SBP, mmHg (mean) | 136 | na | 135 | 140 | na | 138 | 133 | 137 | 142 | 137 | 127 | 128 |

| DBP, mmHg (mean) | 84 | na | 78 | 81 | na | 76 | 78 | 76 | 84 | 80 | 77 | 77 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (mean) | 11.6 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 10.6 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 7.6 |

| Body mass index (mean) | 31.5 | 24.4 | 32.3 | 32.0 | 26.9 | 32.4 | 29.4 | 24.2 | 28.9 | 30.7 | 24.3 | 25.2 |

| Number assessed for DR | 463 | 94 | 200 | 119 | 40 | 1261 | 1905 | 940 | 24 | 1758 | 317 | 168 |

| ≤ 20/20 or microaneurysms only, % | 50 | na | 55 | na | 0 | 49 | 28 | 53 | 0 | na | 44 | na |

| 31 to 37, mild NPDR, % | 46 | na | 38 | 42 | 0 | 18 | 54 | 31 | 16 | na | 31 | na |

| 41 to 53, moderate/severe NPDR, % | na | 100 | 36 | 17 | 8 | 84 | na | 26 | na | |||

| > 53, PDR or PRP, % | 4 | na | 7 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | na | 0 | na |

| Myocardial infarction, % | 24 | na | na | 2.4 | na | na | 5.2 | 0 | na | 5.7 | na | na |

| Stroke, % | 3.5 | na | na | 0.8 | na | na | 1.4 | 0 | na | 2.3 | na | na |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure, mmHg DM, diabetes mellitus DR, diabetic retinopathy na, information not found in study publications NPDR, non‐proliferative diabetic retinopathy PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy PRP, panretinal photocoagulation SBP, systolic blood pressure, mmHg

4. Design features of trials for normotensive or treated hypertensive type 2 diabetic participants, by date initiated or earliest publication.

| Characteristic | ABCD (1) | Ravid 1993 | Medi‐Cal | ABCD‐2V (1) | Pradhan | ACCORD Eye | DIRECT Protect 2 | J‐EDIT | Knudsen | ROADMAP | Wang | Zhao |

| Year trial initiated | 1991 | 1993 | 1995 | 1997 | 1997 | 2001 | 2001 | 2001 | 2003 | 2004 | 2008 | 2008 |

|

Definition of "hypertension," SBP/DBP, mmHg or other |

DBP > 90, not on medication | > 150/90 |

> 135/85 | SBP ≥ 140, DBP ≥ 90, or on medication |

> 140/90 | 1x SBP ≥ 160 or 2x ≥ 140 |

≥ 130/85, ≥ 160/90 on medication |

> 130/85 | na | ≥ 130/80 | na | ≥ 130/80 |

| Primary outcome, parent study | 24‐hour creatinine clearance | Proteinuria, kidney function |

Glycated hemoglobin | 24‐hour creatinine clearance, UAE | DR | Death, MI, stroke | DR | CVD, DM complications | Diabetic maculopathy | ACR | DR | Composite (death, CVD, stroke, retinopathy, etc.) |

| Type of intervention: | ||||||||||||

| More BP control | ACEi or CCA | ACEi | Monthly case management | ARB + | ACEi | Antihypertensive medications by algorithm | ARB | Intense multifactorial intervention.a |

ARB | ARB | ACEi | Intensive management (monthly) |

| Less BP control | Placebo | Placebo | Routine care | Placebo + | Multivitamin | Antihypertensive medications by algorithm | Placebo | Conventional management | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Standard care |

| Blood pressure target: | ||||||||||||

| More BP control | DBP decrease ≥ 10 mmHg | < 145/95 mmHg | ≤ 135/85 mmHg | DBP ≤ 75 mmHg | na | SBP < 120 mmHg | na | < 130/85 mmHg | na | < 130/80 mmHg | na | < 130/80 mmHg |

| Less BP control | DBP 80 to 89 mmHg |

< 145/95 mmHg | ≤ 135/85 mmHg | DBP 80 to 89 mmHg |

na | SBP 130 to 139 mmHg |

na | None | na | < 140/90 mmHg | na | < 130/80 mmHg |

| Other randomized intervention(s) | None | None | None | None | None | Glycemic control | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Method of DR diagnosis | Photos graded centrally.b | Fundus exams |

Photos graded centrally.c |

na | Fundus exams + photos | Photos graded centrally.b | Photos graded centrally.d | Fundus exams + photos | OCTs photos, FAs, by 2 examiners | PRP, vitreous heme | Photos + OCT images | Unclear |

aBody mass index, glycated hemoglobin, triglycerides, high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol. bWisconsin Fudus Photograph Reading Center. c"Santa Barbara", one of the study clinics. dImperial College Retinopathy Grading Centre.

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker BP, blood pressure CCA, calcium channel antagonist CVD, cardiovascular disease DBP, diastolic blood pressure, mmHg DM, diabetes mellitus DR, diabetic retinopathy FA, fluorescein angiography na, information not found in study publications OCT, ophthalmic computed tomography PRP, panretinal photocoagulation SBP, systolic blood pressure, mmHg UAE, urinary albumin excretion

5. Baseline characteristics of hypertensive type 2 diabetic participants in included trials, by date trial initiated or earliest publication.

| Characteristic | UKPDS/HDS | ABCD (2) | Steno‐2 | Rachmani 2002 | ADDITION‐Europe | ADVANCE/AdRem | DEMAND | BENEDICT | HINTS | J‐DOIT3 |

| Number randomized | 1148 | 470 | 160 | 141 | 3057 | 2130 | 380 | 1209 | 503 | 2542 |

| Mean age, years | 56 | 58 | 55 | 57 | 60 | 66 | 61 | 62 | 64 | 59 |

| Women, % | 45 | 33 | 26 | 51 | 42 | 39 | 35 | 46 | 5 | 38 |

| White, % | 87 | 66 | na | na | 94 | 48 | na | 100 | 47 | na |

| Mean DM duration, years | 2.6 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 0 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 7.4 | na | 8.6 |

| Current smoker, % | 23 | na | 30 | 0 | 27 | 14 | 13 | 10 | 21 | 23 |

| SBP, mmHg (mean) | 160 | 155 | 148 | 161 | 149 | 143 | 147 | 152 | 145 | 134 |

| DBP, mmHg (mean) | 94 | 98 | 86 | 96 | 86 | 79 | 88 | 89 | na | 80 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (mean) | 6.9 | 11.6 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 5.8 | 5.9 | na | 8.0 |

| Body mass index (mean) | 29.6 | 31.8 | 29.9 | 28.6 | 31.6 | 27.7 | 29.6 | 28.7 | 30.4 | 24.8 |

| Number assessed for DR | 929 | 470 | 160 | 129 | 2190 | 1602 | 237 | 550 | 194 | 2540 |

| ≤ 20/20 or microaneurysms only, % | 67 | 40 | 73 | 15 | na | 82 | 81 | 84 | 70 | na |

| 31 to 37, mild NPDR, % | 25 | 55 | 21 | na | 8 | 19 | 15 | 30 | na | |

| 41 to 53, moderate/severe NPDR, % | 8 | na | 8 | na | ||||||

| > 53, PDR or PRP, % | 5 | 6 | na | 1 | 1 | na | ||||

| Myocardial infarction, % | 0 | 0 | na | 0 | 6.4 | 12 | na | 0 | na | na |

| Stroke, % | 0 | 0 | na | 0 | 2.4 | 9 | na | 0 | na | na |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure, mmHg DM, diabetes mellitus DR, diabetic retinopathy na, information not found in study publications NPDR, non‐proliferative diabetic retinopathy PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy PRP, panretinal photocoagulation SBP, systolic blood pressure, mmHg

6. Design features of trials for hypertensive type 2 diabetic participants, by date trial initiated or earliest publication.

| Characteristic | UKPDS/HDS | ABCD (2) | Steno‐2 | Rachmani 2002 | ADDITION‐Europe | ADVANCE/AdRem | DEMAND | BENEDICT | HINTS | J‐DOIT3 |

| Year trial initiated | 1987 | 1991 | 1992 | 1995 | 2001 | 2002 | 2002 | 2003a | 2006 | 2006 |

|

Definition of "hypertension", SBP/DBP, mmHg, or otherb |

≥ 160/95 or antihypertensive medication | DBP ≥ 90 | ≥ 160/95 (≥ 135/85) |

> 140/90 or antihypertensive medication | > 135/85 | > 140/90 or antihypertensive medication | ≥ 130/85 or antihypertensive medication | na | > 140/90 or antihypertensive medication | > 130/80 |

| Primary outcome, parent study | Macro‐ and microvascular complications | 24‐hour creatinine clearance | Nephropathy | eGFR | Death, CVD events | Macro‐ and microvascular complications | GFR | Microalbuminuria | BP control | Macrovascular diabetic complications |

| Type of intervention: | ||||||||||

| More BP control | ACEi or β blocker |

ACEi or CCA | Intensive intervention |

Patient participation in education and care | Stepped antihypertensive medication | ACEi or diuretic | ACEi or CCB | ACEi, ndCCB, or combination | Nurse management |

"Intensive intervention" |

| Less BP control | No ACEi or β blocker |

Placebo | Conventional treatment | Standard care | Routine care | Placebo | CCB or placebo | Placebo | Usual care | Conventional intervention |

| Blood pressure target: | ||||||||||

| More BP control | < 150/85 mmHg | DBP < 75 mmHg | < 140/85 (< 130/80c) |

< 130/85 mmHg | ≤ 120/80 mmHg | na | < 120/80 mmHg | < 120/80 mmHg | ≤ 140/80 mmHg | ≤ 120/75 mmHg |

| Less BP control | < 180/105 mmHg | DBP 80 to 89 mmHg | < 160/95 (< 135/85c) |

na | ≤ 135/85 mmHg | na | < 120/80 mmHg | < 120/80 mmHg | ≤ 140/80 mmHg | ≤ 130/80 mmHg |

| Other randomized intervention(s) | Intense glucose control vs standard | None | None | None | Intense glucose and cholesterol control vs standard | Intense glucose control vs standard | None | ndCCB vs placebo | None | None |

| Method of DR diagnosis | Photos graded centrally. | Photos graded centrally.d | Photos graded centrally.e | Fundus exams | Photos graded centrally.e |

Photos graded centrally.f | Fundus exams + photos | Fundus exams + photos | Diagnosis in electronic chart | Fundus exams + records |

aDate of earliest publication. bAs defined by investigators. cFrom 2000. dWisconsin Fundus Photograph Reading Center. eBaseline photos taken up to 3 months before/after randomization. fAdRem Sub‐study Coordination Centre, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor BP, blood pressure (systolic/diastolic) or other CCA, calcium channel antagonist CCB, calcium channel blocker CVD, cardiovascular disease DBP, diastolic blood pressure, mmHg DR, diabetic retinopathy eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate GFR, glomerular filtration rate na, information not found in study publications ndCCBs, non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers SBP, systolic blood pressure, mmHg

Study design

The included trials were conducted in North America, Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and Australia. The trials varied in size: the largest trial randomized 4477 participants (ROADMAP), but only 1758 were analyzed for diabetic retinopathy outcomes; the next‐largest trial enrolled 3057 participants (ADDITION‐Europe). The smallest trial enrolled 16 participants (Chase). In total, 4620 participants with type 1 diabetes mellitus and 22,565 participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus enrolled in the included trials. Among the trial participants, 4382 type 1 and 16,290 type 2 diabetics had baseline ophthalmic evaluations (Table 2; Table 4; Table 6). Most trials reported diabetic retinopathy outcomes only for participants who had both baseline and follow‐up photographs or examinations. Three trials reported findings from randomized participants at a subset of participating centers where baseline and follow‐up retinal examinations were performed (BENEDICT; DEMAND; Medi‐Cal). Two trials analyzed a subset of participants randomized in a larger parent study who agreed to participate in additional retinal examinations (ACCORD Eye; ADVANCE/AdRem); one study added a trial of blood pressure control during the course of the larger trial (UKPDS/HDS). Three trials were conducted within the Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in Diabetes Trial (ABCD), two for initially normotensive participants, ABCD (1); ABCD‐2V (1), and one for hypertensive participants (ABCD (2)). The ABCD trials and three other trials conducted within another parent study, DIRECT Prevent 1; DIRECT Protect 1; DIRECT Protect 2, were designed, conducted, analyzed, and published as three separate RCTs. Length of study intervention and follow‐up varied among included studies, from less than one year, Knudsen; Pradhan, to nine or more years, UKPDS/HDS; Zhao.

Study participants

Type 1 diabetes

Among the seven trials (4620 participants) that reported outcome data for type 1 diabetics (AdDIT; Chase; DIRECT Prevent 1; DIRECT Protect 1; EUCLID; Larsen; RASS), diabetic retinopathy outcomes were designated by the trial investigators as of primary interest in only two of the trials (DIRECT Prevent 1; DIRECT Protect 1). Except for Chase, diabetic retinopathy was diagnosed and staged by individuals masked to treatment assignment; in five of these six studies the retinal photographs were sent to a reading center for central grading of retinopathy severity.

Participants in these seven trials were young, with mean age per trial of about 30 years, except for AdDIT, and had blood pressures in the normal range at baseline (i.e. were normotensive). Almost all participants in the three trials that reported race/ethnicity were specified to be "white." A large majority of participants had either no retinopathy, microaneurysms only, or mild non‐proliferative retinopathy at baseline. Four trials enrolled a few participants with more severe retinopathy at baseline (Table 2) (Chase; DIRECT Protect 1; EUCLID; RASS). Participants in EUCLID had lower mean glycated hemoglobin levels than participants in the other six trials; mean time since diagnosis of diabetes was shorter for participants in AdDIT, reflecting the younger age of the participants (Table 2). Among trials conducted in the 2000s, hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure greater than 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 85 mmHg in the absence of antihypertensive medication, which are lower blood pressure values than for trials conducted earlier in this population.

Type 2 diabetes

Individuals with type 2 diabetes enrolled in 22 trials (22,565 participants). The mean ages of participants were primarily in the sixth or seventh decade. Four of the 22 trials were conducted in Asia (J‐DOIT3; J‐EDIT; Wang; Zhao).

In 12 trials (10,825 participants; Table 4), outcome data were reported for participants who at the time of enrollment were defined by the investigators to be either normotensive or hypertensive with blood pressure controlled with antihypertensive medication (ABCD (1); ABCD‐2V (1); ACCORD Eye; DIRECT Protect 2; J‐EDIT; Knudsen; Medi‐Cal; Pradhan; Ravid 1993; ROADMAP; Wang; Zhao). Definitions of normal blood pressure tended to be more restrictive in trials initiated in 1995 or later; blood pressure targets set by the investigators of later trials were correspondingly lower. Diabetic retinopathy was the primary outcome of interest to the investigators of only three of the 10 trials of normotensive participants (DIRECT Protect 2; Pradhan; Wang). In four studies, retinal photographs were sent to a central site for interpretation and grading of diabetic retinopathy severity (ABCD (1); ACCORD Eye; DIRECT Protect 2; Medi‐Cal).

Ten trials (11,740 participants; Table 6) reported outcome data for type 2 diabetics who were hypertensive at baseline as defined by the study investigators (ABCD (2); ADDITION‐Europe; ADVANCE/AdRem; BENEDICT; DEMAND; HINTS; J‐DOIT3; Rachmani 2002; Steno‐2; UKPDS/HDS). None of the 10 trials of type 2 diabetics with hypertension specified diabetic retinopathy outcomes as outcomes of primary interest. In five of the 10 studies in this subgroup, either an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or a calcium channel blocker had been given to participants in one arm for comparison with placebo in the other arm (ABCD (2)); ADVANCE/AdRem; BENEDICT; DEMAND; UKPDS/HDS). In five trials, various approaches to the management of hypertension, and often other conditions as well, were compared with "routine," "standard," "conventional," or "usual" care (ADDITION‐Europe; HINTS; J‐DOIT3; Rachmani 2002; Steno‐2). In five of the 10 trials, retinal photographs were assessed centrally to diagnose and/or grade the severity of diabetic retinopathy and to assess outcomes (ABCD (2); ADDITION‐Europe; ADVANCE/AdRem; Steno‐2; UKPDS/HDS).

Study interventions

In all seven trials in which participants with type 1 diabetes mellitus were enrolled, the investigators had randomized participants to an antihypertensive agent (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor [ACEi] or angiotensin II receptor blocker [ARB]) versus placebo or no treatment for comparison of outcomes. Three of the trials reported blood pressure targets for participants (EUCLID; Larsen; RASS).

In addition to all seven trials of participants with type 1 diabetes, eight of the 12 trials that enrolled normotensive or treated hypertensive participants with type 2 diabetes compared antihypertensive medication to placebo or no treatment (ABCD (1); ABCD‐2V (1); DIRECT Protect 2; Knudsen; Pradhan; Ravid 1993; ROADMAP; Wang). The antihypertensive medication was an ACEi in three trials and an ARB in four trials, while in ABCD (1), participants in the intervention arm were assigned randomly to one of these two types of medication. In the remaining four trials, intensive case management and monitoring by clinical personnel was compared with usual (routine, conventional, or standard) care.

Among the 10 trials enrolling participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension, the randomized comparison was between an antihypertensive medication and placebo or another medication in five trials. In two of the 10 trials, a program for patient education and clinical management of hypertension was compared with usual care. In ADDITION‐Europe, ADVANCE/AdRem, and UKPDS/HDS, participants were assigned randomly to different blood glucose control strategies in addition to blood pressure control strategies.

Five trials reported that antihypertensive medications could be added to the assigned intervention at the discretion of the treating clinicians (ABCD (1); ADVANCE/AdRem; BENEDICT; DEMAND; Steno‐2). Flexible dosing schedules for antihypertensive medications were permitted in two trials (ABCD (1); EUCLID). In two trials comparing intensive versus standard blood pressure management and monitoring, the class(es) of antihypertensive prescribed were not specified (HINTS; Zhao). In one of these trials (HINTS), behavioral home blood pressure telemonitoring was also incorporated.

Study outcomes

Incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy

Methods of diagnosing and classifying diabetic retinopathy varied among the included studies. Masked personnel at central reading centers evaluated photographs submitted for grading in 12 of the 29 included trials, including 5 of the 7 trials of type 1 diabetics (AdDIT; DIRECT Prevent 1; DIRECT Protect 1; EUCLID; RASS), and 9 of the 22 trials of type 2 diabetics (ABCD (1); ABCD (2); ACCORD Eye; ADDITION‐Europe; ADVANCE/AdRem; DIRECT Protect 2; Medi‐Cal; Steno‐2; UKPDS/HDS). The investigators of the remaining two trials of type 1 diabetics reported that diabetic retinopathy was assessed by local ophthalmologists masked to treatment assignment (Chase; Larsen).

Among 11 of the remaining 13 trials of participants with type 2 diabetes that reported the method of ascertaining outcomes, investigators of three trials reported local assessment by a masked examiner (BENEDICT; DEMAND; Pradhan). Six trials based retinopathy outcomes on diagnosis and classification by local ophthalmologists (J‐DOIT3; J‐EDIT; Knudsen; Rachmani 2002; Ravid 1993; Wang); one on retrieval of diagnoses recorded in electronic records (HINTS); and one on documentation of photocoagulation treatment for PDR or macular edema or vitrectomy for VH (ROADMAP). Reports from the remaining trials either did not specify the method used for diagnosing retinopathy or described it unclearly (ABCD‐2V (1); Zhao).

Almost all studies that used central or local grading of photographs to diagnose and monitor progression of diabetic retinopathy employed some version of the severity scale developed for the ETDRS or a modified or simplified version of it. Two trials used the EURODIAB 5‐step scale (EUCLID; Steno‐2).

Regarding the primary outcomes of this review, five‐year incidence of diabetic retinopathy was reported in one trial of type 1 diabetics, DIRECT Prevent 1, and in 10 trials of type 2 diabetics (ABCD (1); ACCORD Eye; ADVANCE/AdRem; BENEDICT; DEMAND; DIRECT Protect 2; J‐EDIT; Rachmani 2002; Ravid 1993; Steno‐2; UKPDS/HDS). Five‐year progression was reported in five trials, one trial of participants with type 1 diabetes, DIRECT Protect 1, and four trials of participants with type 2 diabetes (ADVANCE/AdRem; DIRECT Protect 2; J‐EDIT; UKPDS/HDS).

Trial investigators reported five‐year combined incidence and progression of retinopathy for participants with type 1 diabetes enrolled in one trial (RASS), for normotensive participants with type 2 diabetes in two trials (ABCD (1); ACCORD Eye), and for participants with type 2 diabetes and hypertension in five trials (ABCD (2); ADDITION‐Europe; ADVANCE/AdRem; HINTS; Steno‐2).

Investigators of ACCORD Eye and ROADMAP reported data from observational follow‐up of trial participants. These data from the ROADMAP observational study were the only diabetic retinopathy data reported from that study. We excluded the data from the observational study periods of both studies from analyses of effects of interventions on outcomes for this review.

Incidence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), clinically significant macular edema (CSME), or vitreous hemorrhage (VH)

The investigators of nine trials reported five‐year incidence of PDR, CSME, or VH which typically result in treatment of affected eyes (ABCD (1); ADDITION‐Europe; ADVANCE/AdRem; DIRECT Protect 1; DIRECT Protect 2; Rachmani 2002; RASS; Ravid 1993; Steno‐2).

Visual acuity

Only two trials reported moderate loss of visual acuity (loss of 3 to 5 lines on a visual acuity chart with a logMAR scale) (ACCORD Eye; UKPDS/HDS), through four years and eight years, respectively. Investigators in these same trials and in Steno‐2 also reported the incidence of blind eyes among participants.

Other outcomes

Other outcomes, including quality of life, cost‐effectiveness data, and adverse events from individual trials, were reported infrequently, as described in the Effects of interventions section of this updated review.

Sources of funding

Eight trials were sponsored entirely by pharmaceutical companies (ABCD‐2V (1); BENEDICT; DEMAND; DIRECT Prevent 1; DIRECT Protect 1; DIRECT Protect 2; EUCLID; ROADMAP). Ten trials were conducted with partial support from industry and additional support from governmental agencies and foundations (ABCD (1); ABCD (2); ACCORD Eye; BENEDICT; Chase; Knudsen; Medi‐Cal; RASS; Steno‐2; UKPDS/HDS). Partial support from industry was typically in the form of study drugs and supplies or support for conducting specific procedures or analyses. Nine trials were conducted with support exclusively from governmental agencies, foundations, or grants from participating institutions (AdDIT; ADDITION‐Europe; ADVANCE/AdRem; HINTS; J‐EDIT; Pradhan; Ravid 1993; Wang; Zhao). Source of funding to conduct the trial was not reported in Larsen or Rachmani 2002.

Excluded studies

The primary reasons for excluding each of the 21 studies selected during the updated searches are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We excluded 10 RCTs of blood pressure control because no data were available for diabetic retinopathy outcomes, although diabetic retinopathy was specified as a secondary outcome in a trial publication or registration record. We contacted trial investigators who were first authors of primary reports from the trials to ascertain whether retinopathy outcomes were available. None of the respondents provided data because diabetic retinopathy outcomes had not been evaluated in the trials. We excluded 10 additional studies because they were not RCTs or because they had not investigated blood pressure control interventions. We excluded a report of data from two RCTs because the investigators had reported combined findings from the two trials and did not provide outcome data from the two individual trials in a manner that permitted estimation of effects in each trial.

Risk of bias in included studies

An overall summary of the risk of bias assessments of the included trials with respect to this review is provided in Figure 2. Details for each individual study are presented in the risk of bias section of the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Missing cells indicate that study did not measure corresponding review outcomes.

Allocation

We judged 20 trials to be at low risk of bias for random sequence generation (ABCD (1); ABCD (2); ABCD‐2V (1); ACCORD Eye; AdDIT; ADDITION‐Europe; ADVANCE/AdRem; DEMAND; DIRECT Prevent 1; DIRECT Protect 1; DIRECT Protect 2; EUCLID; HINTS; J‐DOIT3; Rachmani 2002; RASS; Ravid 1993; ROADMAP; UKPDS/HDS; Zhao), as reports from these studies indicated that an appropriate randomization method had been used. We assessed the remaining nine trials as having an unclear risk of bias due to insufficient descriptions of random sequence generation in the trial reports (BENEDICT; Chase; J‐EDIT; Knudsen; Larsen; Medi‐Cal; Pradhan; Steno‐2; Wang).

We judged allocation concealment methods as at low risk of bias for 14 trials that employed methods such as assignments made by a central co‐ordinating center; unclear risk of bias for 14 trials for which we could not find a description of the random allocation method employed (AdDIT; ADDITION‐Europe; BENEDICT; Chase; J‐EDIT; Knudsen; Larsen; Medi‐Cal; Pradhan; Rachmani 2002; RASS; Ravid 1993; Wang; Zhao); and high risk of bias for one trial that did not describe an allocation concealment method and did not mask treatments (Steno‐2). Block size in Steno‐2 was also fixed so that later assignments in each block of four could have been known to the investigators.

Consequently, a total of 14 trials were at low risk of selection bias based on both the description of the random allocation process and concealment of the random allocation before assignment (Figure 2).

Masking (performance bias and detection bias)

In 18 of the 28 trials in which one or more of the primary outcomes for this review were reported, it was indicated that assessors of the diabetic retinopathy outcomes were masked to the assigned treatment. We judged these 18 trials to be at low risk, six trials to be at unclear risk (Chase; Medi‐Cal; Rachmani 2002; Ravid 1993; Wang; Zhao), and the remaining four trials to be at high risk of performance and detection bias for retinopathy outcomes (Figure 2) (ABCD‐2V (1); HINTS; J‐DOIT3; J‐EDIT). Of the 19 trials that reported our secondary outcomes, we judged eight trials to be at low risk of performance and detection bias based on proper methods of masking (ABCD (1); DIRECT Protect 1; DIRECT Protect 2; EUCLID; Knudsen; Larsen; RASS; Steno‐2); three trials to be at high risk of performance and detection bias due to lack of masking for visual acuity assessment (Chase; J‐DOIT3; Pradhan); and the remaining seven trials to have an unclear risk of performance and detection bias (ACCORD Eye; ADDITION‐Europe; Pradhan; Rachmani 2002; Ravid 1993; UKPDS/HDS; Wang).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged eight trials to be at high risk of bias due to incomplete primary outcome data, including missing data for roughly 40% of randomized participants in two trials (ABCD (1); ABCD (2)), and the exclusion of participants with missing baseline retinal photographs in one trial (ADVANCE/AdRem). In ADDITION‐Europe, retinal images were taken at a follow‐up visit or extracted from medical records for only 2190 (76.6%) of 2861 participants alive at five years. In AdDIT, there were 15% withdrawals from the trial; 19 participants were excluded from the combined placebo arm and 18 participants from the combined ACEi arm. In J‐EDIT, diabetic retinopathy data were reported for only 940 (80.1%) of 1173 participants due to the inability to see fundus details in photographs; attrition was similar in Zhao and Medi‐Cal. Outcomes for participants with cataract, vitreous heme, or other opacities would thus have been excluded. Furthermore, the dropout rate after six years was 8.9% (104 cases). Investigators of eight trials did not provide sufficient information regarding completeness of follow‐up, thus we judged these trials as being at unclear risk of attrition bias (ABCD‐2V (1); EUCLID; Larsen; Rachmani 2002; RASS; Ravid 1993; ROADMAP; Steno‐2). One trial did not measure our primary outcome of interest; we judged the remaining 12 trials to have a low risk of attrition bias for primary outcome data. Secondary outcomes specified for this review were reported less frequently than primary outcomes; for 11 trials, no single one of our secondary outcomes was reported, so that risk of attrition bias was not applicable for secondary outcomes in those instances.

Selective reporting