Abstract

Background

Although previous studies have provided data on early pandemic periods of alcohol and substance use in adolescents, more adequate studies are needed to predict the trends of alcohol and substance use during recent periods, including the mid-pandemic period. This study investigated the changes in alcohol and substance use, except tobacco use, throughout the pre-, early-, and mid-pandemic periods in adolescents using a nationwide serial cross-sectional survey from South Korea.

Methods

Data on 1,109,776 Korean adolescents aged 13–18 years from 2005 to 2021 were obtained in a survey operated by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. We evaluated adolescents’ alcohol and substance consumption prevalence and compared the slope of alcohol and substance prevalence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to see the trend changes. We define the pre-COVID-19 period as consisting of four groups of consecutive years (2005–2008, 2009–2012, 2013–2015, and 2016–2019). The COVID-19 pandemic period is composed of 2020 (early-pandemic era) and 2021 (mid-pandemic era).

Results

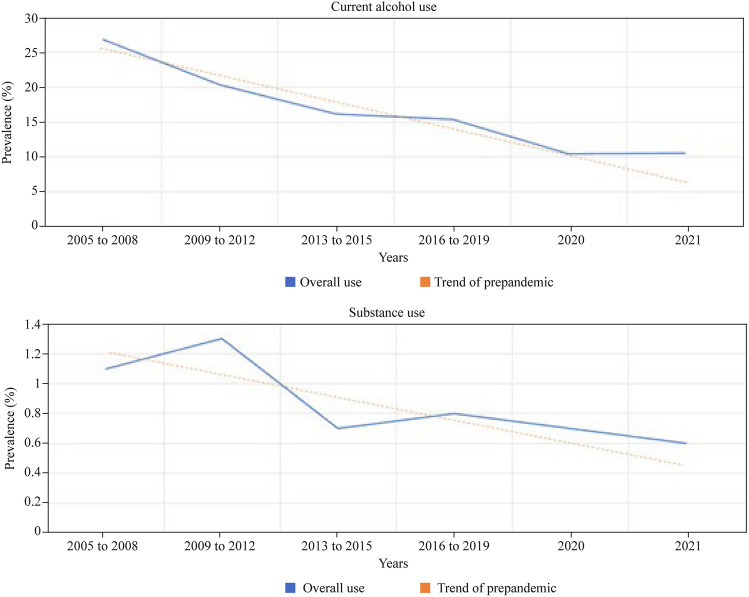

More than a million adolescents successfully met the inclusion criteria. The weighted prevalence of current alcohol use was 26.8% [95% confidence interval (CI) 26.4–27.1] from 2005 to 2008 and 10.5% (95% CI 10.1–11.0) in 2020 and 2021. The weighted prevalence of substance use was 1.1% (95% CI 1.1–1.2) from 2005 to 2008 and 0.7% (95% CI 0.6–0.7) between 2020 and 2021. From 2005 to 2021, the overall trend of use of both alcohol and drugs was found to decrease, but the decline has slowed since COVID-19 epidemic (current alcohol use: βdiff 0.167; 95% CI 0.150–0.184; substance use: βdiff 0.152; 95% CI 0.110–0.194). The changes in the slope of current alcohol and substance use showed a consistent slowdown with regard to sex, grade, residence area, and smoking status from 2005 to 2021.

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of alcohol consumption and substance use among over one million Korean adolescents from the early and mid-stage (2020–2021) of the COVID-19 pandemic showed a slower decline than expected given the increase during the prepandemic period (2005–2019).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12519-023-00715-9.

Keywords: Alcohol, Adolescent, Corona virus disease 2019, South Korea, Substance use

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in considerable impacts on mortality and economic consequences [1, 2], and lockdown and physical distancing [3] have changed habitual or daily behaviors, physical activity and mental health [4]. The health and social consequences of this infectious disease are still under investigation [5], and alcohol and substance consumption may also arise as a significant risk factor.

In particular, alcohol and substance use can harm adolescents in various ways, and it is important to investigate the prevalence of adolescents’ substance use to prevent addiction [6]. The striatal reward/motivation and limbic-emotional circuits are hyperactive during adolescence, leading to greater emotional reactivity and reward-seeking behaviors [7]. The prefrontal cortex of adolescents cannot fully self-regulate, leading to high impulsivity and risk taking [7]. Therefore, early exposure to substance use may further impair the development of the prefrontal cortex, increasing the long-term risk for addiction. Despite the risk of alcohol and substance use in adolescents, however, limited studies have been performed on the prevalence of adolescents’ alcohol and substance use during the pandemic.

Some studies have provided data only on early pandemic periods of substance use in adolescents [2, 8] that may be inadequate to predict the trends of substance use during this period [1, 9]. Additionally, there are studies that examine the prevalence of alcohol and substance use in adolescents reporting inconsistent results [2, 8]. Thus, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol and substance use in adolescents remains unclear. The interrupted global prediction for health indications based on pre-pandemic data on alcohol and substance use trends needs to be considered as a major public health issue.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate trend changes in alcohol and substance use among adolescents of South Korea in the early/mid-pandemic period and analyzed the changes.

Methods

Study population and data sources

We obtained data from the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS) between 2005 and 2021, a survey operated by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) for government policies [10]. The study investigated a sample of respondents to present representative data of the nation and estimate the total population of adolescents in South Korea. To account for this, the study population was selected using sophisticated statistical methods of two-step stratification, sample clustering, and weightings [10]. In the stratification stage, the population was divided into 117 layers using regional groups and school levels. Then, the number of sample schools was allocated by applying a proportional allocation method to match the population composition ratio and sample composition ratio by stratification variable. For sampling, the first extraction unit was school, and the second extraction unit was class using stratified cluster sampling.

Adolescents in middle to high school (aged 12–18 years) were voluntarily involved in a web-based survey in their schools (average response rate: 95%) [10]. The study protocol has been endorsed by the University of Sejong (endorsement for data use; SJU-HR-E-2020-003) and KDCA (endorsement for study construction).

Endpoints and covariates

The adolescent participants were asked to respond how many days they consumed an alcohol drink within 30 days: none, 1–2 days, 3–5 days, 6–9 days, 10–19 days, 20–29 days, and every day. We sorted participants into nondrinkers and current drinkers and defined current drinkers as those who drink alcohol in 1–30 days within 30 days. Moreover, those who drink alcohol every day were defined as daily drinkers. They were also asked if they had used substances except for treatment purposes, with the response options of inhalants, central nervous system depressants and stimulants, and others. As it is not easy to find adolescents who have continuously used drugs under Korean culture and law prohibiting all substances, the study focused on whether the participants have substance use experiences in their entire life. Tobacco usage was excluded because the Korean social context deals with smoking a distinct category and handles it accordingly.

The 17-year trends of changes regarding alcohol drinking and substance use were the main outcomes to understand whether COVID-19 affected these trends. Furthermore, we presented the trend change for both alcohol and substance use in each subgroup by sex, grade, residence area, and smoking during the COVID-19 pandemic and before it.

Data on age (years), grade (middle school: 7th–9th grade; high school: 10th–12th grade), sex (male and female), body mass index (kg/m2), parents’ highest educational levels (high school or lower, and college or higher), familial economic status (high, middle-high, middle, middle-low, low), academic performance (high, middle-high, middle, middle-low, low), depressive symptoms (yes and no), smoking habits (yes and no), and residential areas (rural and urban) [11] were obtained from self-report questionnaires, as mentioned above [10]. To manage the age and cohort effect, we presented school grade divided by middle school (7th–9th grade) and high school (10th–12th grade) as the criteria to see the trend changes in each group and to compare each other.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC,

USA) and SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value less than 0.05 [12].

Data were collected from the KYRBS between 2005 and 2021. Those with missing data were excluded from the analysis. We explored the trend changes in the proportion of drinking alcohol and substance use stratified by sex, grade, residence area, and smoking status. We set four groups of consecutive years (2005–2008, 2009–2012, 2013–2015, and 2016–2019) as the pre-COVID-19 period to obtain stable prevalence estimates that would be found in each one-year unit and two groups (2020 and 2021) as the COVID-19 pandemic period of the KYRBS cycle.

Weighted complex sampling analysis was conducted using linear and logistic regression models. For the trend of prevalence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, we obtained β-coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a linear regression model. We analyzed the β-difference to indicate the difference between before the pandemic (2005–2019) and during the pandemic (2020 and 2021). A logistic regression model was used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs of the KYRBS cycle in the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 and 2021) versus the last cycle before the pandemic (2016–2019).

Results

A total of 1,109,776 adolescents were included in the KYRBS from 2005 to 2021, with 52.4% males (95% CI 51.8–53.1). Table 1 provides an illustration of their general characteristics. The weighted estimated mean age was 15.04 years (95% CI 15.03–15.05), including 573,932 (weighted %, 50.3%) middle school students and 535,844 (weighted %, 49.7%) high school students. The sample size of adolescents in each time period is 269,289 in 2005–2008, 288,910 in 2009–2012, 206,381 in 2013–2015, 238,217 in 2016–2019, 53,534 in 2020 and 53,445 in 2021.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participating adolescents in the KYRBS, 2005–2021 (n = 1,109,776)

| Characteristics | Weighted sample, n (%) or weighted average % (95% CI) | Crude sample, n (%) or median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 56,122,639 (100.0) | 1,109,776 (100.0) |

| Age, y | 15.04 (15.03–15.05) | 15.00 (14.00–16.00) |

| Grade | ||

| 7th–9th grade (middle school) | 50.3 (49.9–50.6) | 573,932 (51.7) |

| 10th–12th grade (high school) | 49.7 (49.4–50.1) | 535,844 (48.3) |

| Sex, male | 52.4 (51.8–53.1) | 572,055 (51.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 20.7 (20.7–20.8) | 20.3 (18.5–22.6) |

| Underweight (below 5th percentile) | 8.2 (8.2–8.3) | 89,892 (8.1) |

| Normal (5th–85th percentile) | 76.2 (76.1–76.3) | 842,428 (76.0) |

| Overweight (85th–95th percentile) | 8.1 (8.0–8.1) | 91,002 (8.2) |

| Obese (above 95th percentile) | 7.5 (7.4–7.6) | 85,453 (7.7) |

| Region of residence | ||

| Rural | 45.9 (45.5–46.3) | 514,496 (46.4) |

| Urban | 54.1 (53.7–54.5) | 595,280 (53.6) |

| Smoking | 9.5 (9.4–9.7) | 103,793 (9.4) |

| Substance use | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 10,282 (0.9) |

| Alcohol use | 19.3 (19.2–19.5) | 211,679 (19.1) |

| Depression | 31.5 (31.3–31.6) | 347,456 (31.3) |

| Highest educational level of parents | ||

| High school or lower | 46.4 (46.1–46.7) | 521,635 (47.0) |

| College or higher | 38.5 (38.2–38.8) | 409,612 (36.9) |

| Unknown | 15.1 (15.0–15.2) | 178,529 (16.1) |

| Economic level | ||

| High | 8.1 (8.0–8.2) | 87,663 (7.9) |

| Middle-high | 27.0 (26.8–27.2) | 291,759 (26.3) |

| Middle | 46.7 (46.6–46.9) | 523,241 (47.1) |

| Middle-low | 14.3 (14.2–14.5) | 163,052 (14.7) |

| Low | 3.8 (3.8–3.9) | 44,061 (4.0) |

| School performance | ||

| High | 12.2 (12.1–12.3) | 135,726 (12.2) |

| Middle-high | 25.5 (25.4–25.6) | 281,457 (25.4) |

| Middle | 28.5 (28.4–28.6) | 316,853 (28.6) |

| Middle-low | 23.4 (23.3–23.5) | 259,611 (23.4) |

| Low | 10.4 (10.3–10.5) | 116,129 (10.5) |

BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, IQR interquartile range, KYRBS Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey

Figure 1 shows the trends in alcohol consumption and substance use prevalence among Korean adolescents from 2005 to 2021, including the period of COVID-19 pandemic. A decreasing trend was presented in the proportions of current alcohol drinkers and substance users with different slopes at each period. Tables 2 and Supplementary Table 1 show the trend changes and rates for drinking alcohol (current drinkers and daily drinkers), and Table 3 shows the trend changes and rates for using substances between 2005 and 2021. The downward slope, however, decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the prepandemic period, which means that the absolute value of the downward slope decreased (current alcohol use: βdiff, 0.167; 95% CI 0.150–0.184; and substance use: βdiff, 0.152; 95% CI 0.110–0.194). The expected prevalence in the pandemic period based on the trend of the prepandemic period is 10.1% in 2020 (versus 10.5% for the estimated prevalence) and 6.3% in 2021 (versus 10.6% for the estimated prevalence) for alcohol use and 0.6% in 2020 (versus 0.7% for the estimated prevalence) and 0.5% in 2021 (versus 0.6% for the estimated prevalence) for substance use.

Fig. 1.

Nationwide 17-year trends and prevalence of alcohol and substance use among one million Korean adolescents from 2005 to 2021

Table 2.

National estimated prevalence and trend of current alcohol use among the adolescent population in South Korea using the KYRBS, 2005–2021

| Characteristics | Current alcohol use, weighted % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2008 | 2009–2012 | 2013–2015 | 2016–2019 | 2020 (early pandemic) | 2021 (mid pandemic) | |

| Overall | 26.8 (26.4–27.1) | 20.3 (20.0–20.6) | 16.2 (15.8–16.6) | 15.4 (15.1–15.7) | 10.5 (10.1–10.9) | 10.6 (10.1–11.0) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 28.2 (27.7–28.6) | 23.2 (22.8–23.6) | 19.7 (19.2–20.2) | 17.4 (17.0–17.8) | 11.9 (11.3–12.6) | 12.3 (11.7–12.9) |

| Female | 25.2 (24.7–25.7) | 17.1 (16.7–17.5) | 12.4 (11.9–12.8) | 13.2 (12.8–13.6) | 8.9 (8.4–9.5) | 8.7 (8.2–9.2) |

| Grade | ||||||

| 7th–9th grade (middle school) | 17.2 (16.9–17.5) | 11.9 (11.7–12.2) | 8.0 (7.8–8.3) | 7.3 (7.1–7.5) | 5.3 (5.0–5.6) | 5.5 (5.2–5.9) |

| 10th–12th grade (high school) | 38.5 (37.9–39.1) | 28.6 (28.1–29.2) | 23.9 (23.2–24.6) | 22.4 (21.9–22.9) | 15.7 (14.9–16.4) | 15.8 (15.1–16.7) |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Rural | 26.2 (25.7–26.6) | 19.5 (19.1–20.0) | 15.3 (14.7–15.8) | 14.1 (13.8–14.5) | 9.6 (9.0–10.3) | 9.6 (9.0–10.2) |

| Urban | 27.3 (26.7–27.9) | 21.0 (20.5–21.5) | 16.3 (16.3–17.5) | 16.4 (16.0–16.8) | 11.1 (10.5–11.8) | 11.2 (10.6–11.9) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | 20.0 (19.7–20.3) | 14.2 (14.0–14.5) | 11.3 (11.0–11.6) | 11.8 (11.6–12.1) | 8.0 (7.7–8.4) | 8.1 (7.8–8.5) |

| Yes | 74.9 (74.2–75.7) | 65.5 (64.7–66.2) | 65.5 (64.6–66.4) | 69.3 (68.4–70.2) | 65.2 (62.8–67.6) | 64.4 (62.3–66.5) |

| Substance use | ||||||

| No | 26.3 (26.0–26.7) | 20.0 (19.7–20.3) | 16.0 (15.6–16.4) | 15.2 (14.9–15.5) | 10.4 (9.9–10.8) | 10.5 (10.0–10.9) |

| Yes | 48.4 (46.2–50.6) | 44.6 (42.6–46.6) | 45.3 (42.0–48.7) | 40.7 (38.4–43.1) | 26.5 (22.0–31.6) | 25.6 (20.6–31.3) |

| Characteristics | Trends in current alcohol use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend in prepandemic, β (95% CI)a | Trend after the pandemic, β (95% CI)a | Trend difference, βdiff (95% CI) | OR (95% CI)b | |

| Overall | − 0.297 (− 0.308 to − 0.285) | − 0.130 (− 0.143 to − 0.118) | 0.167 (0.150–0.184) | 0.646 (0.620–0.673) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | − 0.255 (− 0.268 to − 0.242) | − 0.125 (− 0.140 to − 0.111) | 0.130 (0.111–0.149) | 0.654 (0.624–0.686) |

| Female | − 0.353 (− 0.369 to − 0.336) | − 0.138 (− 0.155 to − 0.121) | 0.215 (0.191–0.239) | 0.634 (0.599–0.670) |

| Grade | ||||

| 7th–9th grade (middle school) | − 0.413 (− 0.426 to − 0.400) | − 0.099 (− 0.118 to − 0.080) | 0.314 (0.291–0.337) | 0.724 (0.685–0.765) |

| 10th–12th grade (high school) | − 0.316 (− 0.331 to − 0.301) | − 0.126 (− 0.141 to − 0.111) | 0.190 (0.169–0.211) | 0.647 (0.616–0.680) |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Rural | − 0.320 (− 0.335 to − 0.306) | − 0.129 (− 0.146 to − 0.112) | 0.191 (0.169–0.213) | 0.647 (0.610–0.685) |

| Urban | − 0.281 (− 0.289 to − 0.264) | − 0.132 (− 0.150 to − 0.115) | 0.149 (0.127 to 0.171) | 0.644 (0.609–0.680) |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | − 0.273 (− 0.284 to − 0.261) | − 0.127 (− 0.140 to − 0.114) | 0.146 (0.129–0.163) | 0.654 (0.628–0.681) |

| Yes | − 0.121 (− 0.141 to − 0.102) | − 0.059 (− 0.083 to − 0.035) | 0.062 (0.031–0.093) | 0.816 (0.751–0.886) |

| Substance use | ||||

| No | − 0.301 (− 0.312 to − 0.289) | − 0.129 (− 0.142 to − 0.117) | 0.172 (0.155–0.189) | 0.648 (0.623–0.675) |

| Yes | − 0.106 (− 0.154 to − 0.058) | − 0.193 (− 0.254 to − 0.132) | − 0.087 (− 0.165 to − 0.009) | 0.513 (0.416–0.633) |

Numbers in bold indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05)

CI confidence interval, KYRBS Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey, OR odds ratio

aEstimated β was calculated using linear regression, and this model included the KYRBS cycle (2005–2008, 2009–2012, 2013–2015, 2016–2019, 2020 and 2021) as a continuous variable

bEstimated OR was derived using logistic regression, and this model included the KYRBS cycle (2016–2019 versus 2020–2021) as a categorical variable

Table 3.

National estimated prevalence and trend of substance use among the adolescent population in South Korea using the KYRBS, 2005–2021

| Characteristics | Substance use, weighted % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2008 | 2009–2012 | 2013–2014 | 2016–2019 | 2020 (early pandemic) | 2021 (mid pandemic) | |

| Overall | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | 1.3 (1.2–1.3) | 0.7 (0.7–0.7) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.4 (1.4–1.5) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) |

| Female | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| Grade | ||||||

| 7th–9th grade (middle school) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| 10th–12th grade (high school) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Rural | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| Urban | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 0.5 (0.5–0.5) | 0.6 (0.6–0.6) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| Yes | 3.4 (3.2–3.7) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 3.2 (2.9–3.6) | 3.4 (3.1–3.8) | 2.2 (1.6–2.9) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) |

| Current alcohol use | ||||||

| Yes | 2.1 (1.9–2.2) | 2.8 (2.6–3.0) | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 2.0 (1.9–2.2) | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) |

| No | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 0.5 (0.4–0.5) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) |

| Characteristics | Trends in substance use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend in prepandemic, β (95% CI)a | Trend after the pandemic, β (95% CI)a | Trend difference, βdiff (95% CI) | OR (95% CI)b | |

| Overall | − 0.196 (− 0.223 to − 0.168) | − 0.044 (− 0.076 to − 0.013) | 0.152 (0.110–0.194) | 0.885 (0.797–0.982) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | − 0.205 (− 0.238 to − 0.171) | − 0.074 (− 0.114 to − 0.034) | 0.131 (0.079–0.183) | 0.804 (0.697–0.928) |

| Female | − 0.175 (− 0.219 to − 0.131) | 0.004 (− 0.046 to 0.054) | 0.179 (0.112–0.246) | 1.025 (0.882–1.192) |

| Grade | ||||

| 7th–9th grade (middle school) | − 0.258 (− 0.291 to − 0.224) | − 0.076 (− 0.120 to − 0.032) | 0.182 (0.127–0.237) | 0.764 (0.665–0.877) |

| 10th–12th grade (high school) | − 0.115 (− 0.158 to − 0.073) | − 0.016 (− 0.060 to 0.028) | 0.099 (0.038–0.160) | 1.005 (0.865–1.168) |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Rural | − 0.138 (− 0.175 to − 0.101) | − 0.073 (− 0.117 to − 0.030) | 0.065 (0.008–0.122) | 0.817 (0.705–0.947) |

| Urban | − 0.246 (− 0.285 to − 0.207) | − 0.023 (− 0.067 to 0.021) | 0.223 (0.164–0.282) | 0.935 (0.810–1.080) |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | − 0.178 (− 0.210 to − 0.145) | 0.012 (− 0.026 to 0.050) | 0.190 (0.140–0.240) | 1.053 (0.938–1.183) |

| Yes | − 0.017 (− 0.060 to 0.026) | − 0.146 (− 0.197 to − 0.096) | − 0.129 (− 0.195 to − 0.063) | 0.556 (0.434–0.712) |

| Current alcohol use | ||||

| Yes | − 0.014 (− 0.054 to 0.027) | − 0.055 (− 0.103 to − 0.007) | − 0.041 (− 0.104 to 0.022) | 0.827 (0.681–1.004) |

| No | − 0.208 (− 0.242 to − 0.174) | 0.008 (− 0.032 to 0.049) | 0.216 (0.163–0.269) | 1.045 (0.927–1.177) |

Numbers in bold indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05)

CI confidence interval, KYRBS Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey, OR odds ratio

aEstimated β was calculated using linear regression, and this model included the KYRBS cycle (2005–2008, 2009–2012, 2013–2014, 2016–2019, 2020 and 2021) as a continuous variable

bEstimated OR was derived using logistic regression, and this model included the KYRBS cycle (2016–2019 versus 2020–2021) as a categorical variable

Current alcohol use showed a national weighted rate of 26.8% (95% CI 26.4–27.1) from 2005 to 2008 and 10.5% (95% CI 10.1–11.0) in 2020 and 2021 (Table 2). The 17-year trend slope of the overall rate of current alcohol use illustrated a consistent decreasing trend in subgroups by sex, grade, residence area, and smoking. The expected prevalence of alcohol use during the pre-pandemic period based on the trend of the pandemic period was 21.8% during 2005–2008, 19.4% during 2009–2012, 17.0% during 2013–2015, and 14.6% during 2016 and 2019. The annual alcohol use prevalence was 16.6% in 2018 and 14.7% in 2019. It showed a decline of 1.9% in one year, which was a larger amount of change than 0.1% in 2020 and 2021.

The national weighted rate of daily alcohol use was 0.4% (95% CI 0.4–0.5) from 2005 to 2008 and 0.1% in 2020 (95% CI 0.1–0.2) and 2021 (95% CI 0.1–0.1; Supplemental Table 1). Its prevalence presents a consistent decline in the slope of each subgroup by sex, grade, residence area of urban, and nonsmoking. However, there was no significant change in the slopes of the subgroup within the rural residence area (βdiff, 0.057; 95% CI − 0.057 to 0.171) and smoking group (βdiff, 0.047; 95% CI − 0.051 to 0.145) comparing trends before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The national weighted rate of substance use was 1.1% (95% CI 1.1–1.2) from 2005 to 2008, 0.7% (95% CI 0.6–0.8) in 2020, and 0.6% (95% CI 0.6–0.7) in 2021 (Table 3). The decline in the slope of the trend regarding the rate of substance use within each subgroup of sex, grade, residence area, and smoking status was consistent with the overall prevalence. The expected prevalence of substance use in the pre-pandemic period based on the trend of the pandemic period was 1.1% during 2005–2008, 1.0% in 2009–2012, 0.9% in 2013–2015, and 0.8% during 2016–2019. The annual prevalence of substance use was 0.9% in 2018, 0.8% in 2019, 0.7% in 2020, and 0.6% in 2021.

Discussion

Findings of our study

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first long-term serial cross-sectional study and nationwide large-scale investigation using a representative population-based dataset to investigate trend changes in alcohol and substance use in over one million South Korean adolescents and weighted to match population characteristics. In this study, representing the nationwide population of adolescents in South Korea, we found that 17-year trends in the overall prevalence of alcohol and/or substance use tended to decrease; however, the estimated prevalence during the pandemic from 2020 to 2021 was higher than the expected prevalence. Furthermore, a similar tendency was found in the stratified analysis by age, sex, area of residence, and smoking status.

Comparison with previous studies

Several studies have previously described the trend of alcohol or substance use in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The few studies on alcohol use have shown inconsistent results: decrease in Iceland (n = 59,701) [2, 8], USA (n = 7842) [13], Spain (n = 303) [14], Switzerland (n = 8972) [15], Netherlands (n = 6070) [16], and Norway (n = 227,258) [17]; increase in Indonesia (n = 2932) [18], Canada (n = 6721) [19], Bosnia-Herzegovina (n = 661) [2] and USA (n = 1084)[20]; and no change in USA (n = 1006) [21], Canada (n = 1054) [22], and nine countries (China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, United States, n = 1330) [23]. Furthermore, several studies on other types of substance use have shown inconsistent results: increases in Indonesia (n = 2932) [18] and the USA (n = 7843) [13]; decreases in the Netherlands (n = 6070) [24] and Finland (n = 10,000) [25]; and no change in Canada (n = 619) [26].

A recent systemic review of 49 intervention trials suggested that the prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, and substance use among adolescents has largely declined during the pandemic [27], supporting findings from the present study. However, their small sample size (mostly less than 10,000), the heterogeneous population in several countries, short-term follow-up period (mostly less than three years) and inappropriate study design (non-representative or nonrandom selection of participants, including convenience, purposive, or volunteer sampling) have potentially contributed to low levels of evidence and inconsistent results [2, 4, 13–23]. Compared to those studies, our study had a large sample size and a homogenous population only in South Korea, was based on a long-term survey conducted for 17 years, and utilized weighted analyses to match population characteristics.

Most of the studies were conducted in America or Europe, and studies from Asia are scarce [2, 4, 13–23]. These studies only showed the prevalence of substance use up to the early pandemic period in 2020 [2, 4, 13–23]. However, our study provides adolescent alcohol and/or substance use prevalence and β-coefficients to easily compare the amount of change in prevalence in each divided period from 2005 to 2021. The present study benefits from a large population-based sample utilizing the sampling strategy and weighting to match population characteristics to make the study adequate to see trend changes.

Possible explanations of our results

The prevalence of alcohol and substance use among adolescents can be explained by various components, which are likely due to the interaction of complex factors. The decrease in the 17-year trends in the overall prevalence of alcohol and/or substance use may be explained by the government’s efforts to reduce the proportion of those using alcohol and substances since before the COVID-19 pandemic [28]. Substance and alcohol awareness campaigns, prevention trainings and other policies to facilitate the prohibition of substance use were actively practiced [29].

Since the start of the pandemic, the limitations implemented have impacted the availability of such substances, and health concerns have potentially facilitated a decrease in substance and alcohol use. Adolescents’ alcohol use was highly dependent on the environment. Adolescents usually drink alcohol with friends outside the home [30]. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, public health restrictions limited the time most adolescents spent in person with friends, limiting availability and access to alcohol and substances during community lockdowns. Young people confined to their homes with parents had fewer opportunities to access and use [30]. Limited in-person contact with friends, adolescents’ decreased availability and access to substances, and increased time staying at home with parents are known to be effective factors in preventing substance and alcohol use [30].

Additionally, socioeconomic status is an important factor in substance use among adolescents [31].The downturn in the economy caused by COVID-19 led to unemployment, financial insecurity, and poverty [31]. Financial difficulties caused by the pandemic are presumed to positively affect substance consumption for adolescents.

Nevertheless, the observed prevalence of substance and alcohol use during the pandemic from 2020 to 2021 was higher than its expected prevalence. The prevalence can be broken down into several factors: parental support, social system, psychological factors, lack of treatment for the patients, peer context, the education system during the COVID-19 period, and accessibility to substances.

Studies among adolescents have identified parental support as a protective factor for substance use, including alcohol use [32]. Lenient parental attitudes and behaviors toward drinking and substances could encourage adolescents’ alcohol and other substance use. Some studies showed that adolescents consuming alcohol with their parents used other substances immediately after social distancing measures were implemented [24]. Additionally, in contrast to teenagers who do not report drinking with their parents, those who use substances with their parents during the COVID-19 crisis will be more likely to use alcohol [24].

Individual psychological factors may lead to a higher risk of alcohol and substance usage. Contrary to the less anxious, fearful and depressed adolescents, those who are more concerned about their safety due to the COVID-19 issue are more prone to use substances alone to cope with the stress of COVID-19 [22, 33]. In addition, the impact of parents’ psychological issues on depression and anxiety [22, 33] may lead to an increased rate of alcohol and substance use.Studies have reported an increase in domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic [22, 33], suggesting an increase in adolescents at risk of family conflict and dysfunction and that stress from family violence may increase the consumption of alcohol and substance use.

Peer context also exists in the less decreasing trend of alcohol and substance use [34]. In the context of substance use among adolescents, there are concerns about how social distancing affects their peer reputations [34], which means that popular adolescents are attempting to uphold group norms via solitary substance use [22]. Adolescents who are less popular, who may have less confidence that their friendships can withstand social distancing, may be more willing to engage in risky behavior, such as face-to-face substance use during a pandemic, to maintain their social status. Thus, it is possible that some adolescents were more likely to engage in substance use with peers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, via technology and sending posts to friends in virtual contexts, it is available to drink with friends in different places and share the experiences of using substance together as in a peer group [34].

Limitations in the school education system during COVID-19 may have an impact on the trend of the use of alcohol and substances. Some reports state that distance learning negatively affects the social development of adolescents [35]. There is a high possibility of exposure to alcohol and substance addiction when there is a lack of social development.

Strengths and limitations

This study has strengths in its examination of large-scale population-based data, a nationwide study that investigates the trend of alcohol and substance usage in Korean adolescents. The data we used are long-term serial data from 2005 to 2021, which helps to examine the change in alcohol and other substance use. Additionally, the inclusion of 2021 data not only examines the changes between the pre-pandemic and early pandemic periods but also examines the most recent trends of substance use in the mid-pandemic period [36, 37].

However, there are several limitations to this study. First, the specific types of substances used are unknown, which limits the detailed analysis of each type. This may lead to a bias of the substance use trend in adolescents regarding a particular substance they used. Second, data on electronic cigarette use were not separately taken into the study. As electronic cigarettes have different traits from usual tobacco [38], there is the possibility of a difference between electronic cigarettes and tobacco’s trend changes early during the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, since our data only included South Korean adolescents, the results cannot represent the general population around the world. Fourth, the number of daily alcohol users in adolescents was insufficient, so there were some differences in trends compared with the current alcohol use group in smoking groups and the rural resident group (Supplementary Table 1). Fifth, missing data were excluded from the analyses, which may have biased the findings of the study. Finally, our study handled data in the pre-pandemic and early to middle stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, so there needs to be continuous monitoring to reflect other effects on the trend of adolescents’ alcohol and substance use in the late phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sixth, although the data we used were based on a web-based survey conducted in a representative class in each selected school by the sampling process, selection bias may not be fully ruled out. Finally, limitations of web-based surveys, including response bias, may have existed, although the survey was anonymized and self-reported.

In conclusion, this study utilizes nationwide data from over one million adolescents and examines the trend changes in alcohol and substance use from 2005 to 2021, with a special emphasis on the early and mid-stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. The observed alcohol and substance use during the pandemic period (2020–2021) was higher than expected compared to the prepandemic period (2005–2019). In particular, both South Korean adolescents’ current alcohol and substance use were consistently higher in males, rural residents, and habitual smoking groups. Our study helps to comprehend the trends in adolescents’ substance use, including alcohol consumption, in the long term and changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. To help the development of public health systems and parental and individual strategies to prevent addiction, future studies might want to look at how specific characteristics changed before and after the pandemic to identify the factors that influence adolescents’ use of alcohol and other substances in detail.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

DKY: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, writing–review and editing, writing–original draft. SP, HY: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, writing–review and editing, writing–original draft. MJK: formal analysis. CYB, HS, SE, SWL, JUS, AK, LJ, LS, CM, AÖY, SYK, JL, VH, RK, GF, LB, SK, JWH, NK, EL, VB, SYR, JIS, HGW: supervision. SP and HY contributed equally as first authors.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HV22C0233 and grant number: HI22C1976). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request. Study protocol, statistical code: available from DKY (email: yonkkang@gmail.com). Data set: available from the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KCDA) through a data use agreement.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical approval

The KYRBS data were anonymous and the study protocol was approved by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KCDA) and Institutional Review Board of Sejong University (SJU-HR-E-2020-003).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jae Il Shin, Email: SHINJI@yuhs.ac.

Dong Keon Yon, Email: yonkkang@gmail.com.

Ho Geol Woo, Email: nr85plasma@naver.com.

References

- 1.Eisenhut M, Shin JI. COVID-19 vaccines and coronavirus 19 variants including alpha, delta, and omicron: present status and future directions. Life Cycle. 2022;2:e4. doi: 10.54724/lc.2022.e4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilic B, Zenic N, Separovic V, Jurcev Savicevic A, Sekulic D. Evidencing the influence of pre-pandemic sports participation and substance misuse on physical activity during the COVID-19 lockdown: a prospective analysis among older adolescents. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2021;34:151–163. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SW, Yuh WT, Yang JM, Cho YS, Yoo IK, Koh HY, et al. Nationwide results of COVID-19 contact tracing in South Korea: individual participant data from an epidemiological survey. JMIR Med Inform. 2020;8:e20992. doi: 10.2196/20992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SW, Yang JM, Moon SY, Kim N, Ahn YM, Kim JM, et al. Association between mental illness and COVID-19 in South Korea: a post-hoc analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:271–272. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00043-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etowa J, Hyman I. Unpacking the health and social consequences of COVID-19 through a race, migration and gender lens. Can J Public Health. 2021;112:8–11. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00456-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson SF, Laursen TM, Osler M, Hjorthøj C, Benros ME, Ethelberg S, et al. Adverse SARS-CoV-2-associated outcomes among people experiencing social marginalisation and psychiatric vulnerability: a population-based cohort study among 4,4 million people. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;20:100421. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan CJ, Andersen SL. Sensitive periods of substance abuse: early risk for the transition to dependence. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2017;25:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorisdottir IE, Asgeirsdottir BB, Kristjansson AL, Valdimarsdottir HB, Jonsdottir Tolgyes EM, Sigfusson J, et al. Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: a longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:663–672. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith L, Shin JI, Koyanagi A. Vaccine strategy against COVID-19 with a focus on the omicron and stealth omicron variants: life cycle committee recommendations. Life Cycle. 2022;2:e5. doi: 10.54724/lc.2022.e5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim MJ, Lee KH, Lee JS, Kim N, Song JY, Shin YH, et al. Trends in body mass index changes among Korean adolescents between 2005–2020, including the COVID-19 pandemic period: a national representative survey of one million adolescents. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:4082–4091. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202206_28978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo IK, Marshall DC, Cho JY, Yoo HW, Lee SW. N-Nitrosodimethylamine-contaminated ranitidine and risk of cancer in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Life Cycle. 2021;1:e1. doi: 10.54724/lc.2021.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SW. Methods for testing statistical differences between groups in medical research: statistical standard and guideline of life cycle committee. Life Cycle. 2022;2:e1. doi: 10.54724/lc.2022.e1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelham WE, 3rd, Tapert SF, Gonzalez MR, McCabe CJ, Lisdahl KM, Alzueta E, et al. Early adolescent substance use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal survey in the ABCD study cohort. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogés J, Bosque-Prous M, Colom J, Folch C, Barón-Garcia T, González-Casals H, et al. Consumption of alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco in a cohort of adolescents before and during COVID-19 confinement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7849. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albrecht JN, Werner H, Rieger N, Widmer N, Janisch D, Huber R, et al. Association between homeschooling and adolescent sleep duration and health during COVID-19 pandemic high school closures. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2142100. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pigeaud L, de Veld L, van Hoof J, van der Lely N. Acute alcohol intoxication in dutch adolescents before, during, and after the first COVID-19 lockdown. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:905–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Soest T, Kozak M, Rodriguez-Cano R, Fluit DH, Cortes-Garcia L, Ulset VS, et al. Adolescents' psychosocial well-being one year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6:217–228. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01255-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sen LT, Siste K, Hanafi E, Murtani BJ, Christian H, Limawan AP, et al. Insights into adolescents' substance use in a low-middle-income country during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:739698. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.739698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaiton M, Dubray J, Kundu A, Schwartz R. Perceived impact of COVID on smoking, vaping, alcohol and cannabis use among youth and youth adults in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67:407–409. doi: 10.1177/07067437211042132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romm KF, Patterson B, Crawford ND, Posner H, West CD, Wedding D, et al. Changes in young adult substance use during COVID-19 as a function of ACEs, depression, prior substance use and resilience. Subst Abus. 2022;43:212–221. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1930629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaffee BW, Cheng J, Couch ET, Hoeft KS, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents' substance use and physical activity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:715–722. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM. What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lansford JE, Skinner AT, Godwin J, Chang L, Deater-Deckard K, Di Giunta L, et al. Pre-pandemic psychological and behavioral predictors of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in nine countries. Dev Psychopathol. 2021 doi: 10.1017/S0954579421001139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallet J, Dubertret C, Le Strat Y. Addictions in the COVID-19 era: current evidence, future perspectives a comprehensive review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;106:110070. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuitunen I. Social restrictions due to COVID-19 and the incidence of intoxicated patients in pediatric emergency department. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191:1081–1083. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02686-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawke LD, Szatmari P, Cleverley K, Courtney D, Cheung A, Voineskos AN, et al. Youth in a pandemic: a longitudinal examination of youth mental health and substance use concerns during COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e049209. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho J, Bello MS, Christie NC, Monterosso JR, Leventhal AM. Adolescent emotional disorder symptoms and transdiagnostic vulnerabilities as predictors of young adult substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediation by substance-related coping behaviors. Cogn Behav Ther. 2021;50:276–294. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2021.1882552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das JK, Salam RA, Arshad A, Finkelstein Y, Bhutta ZA. Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:S61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67:1–114. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Philipsborn P, Stratil JM, Burns J, Busert LK, Pfadenhauer LM, Polus S, et al. Environmental interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and their effects on health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:Cd012292. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012292.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones TM, Hill KG, Epstein M, Lee JO, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Understanding the interplay of individual and social-developmental factors in the progression of substance use and mental health from childhood to adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28:721–741. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurley E, Dietrich T, Rundle-Thiele S. A systematic review of parent based programs to prevent or reduce alcohol consumption in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1451. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7733-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kapetanovic S, Ander B, Gurdal S, Sorbring E. Adolescent smoking, alcohol use, inebriation, and use of narcotics during the Covid-19 pandemic. BMC Psychol. 2022;10:44. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00756-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergman BG, Wu W, Marsch LA, Crosier BS, DeLise TC, Hassanpour S. Associations between substance use and instagram participation to inform social network-based screening models: multimodal cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e21916. doi: 10.2196/21916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mann MJ, Smith ML, Kristjansson AL, Daily S, McDowell S, Traywick P. Our children are not "behind" due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but our institutional response might be. J Sch Health. 2021;91:447–450. doi: 10.1111/josh.13016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin H, Park S, Yon H, Ban CY, Turner S, Cho SH, et al. Estimated prevalence and trends in smoking among adolescents in South Korea, 2005–2021: a nationwide serial study. World J Pediatr. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s12519-022-00673-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon R, Koo MJ, Lee SW, Choi YS, Shin YH, Shin JU, et al. National trends in physical activity among adolescents in South Korea before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2009–2021. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e28456. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallus S, Stival C, Carreras G, Gorini G, Amerio A, McKee M, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products during the Covid-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2022;12:702. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04438-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Study protocol, statistical code: available from DKY (email: yonkkang@gmail.com). Data set: available from the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KCDA) through a data use agreement.