Abstract

Home visiting programs can provide critical support to mothers in recovery from substance use disorders (SUDs) and young children prenatally exposed to substances. However, families impacted by maternal SUDs may not benefit from traditional child-focused developmental home visiting services as much as families not impacted by SUDs, suggesting the need to adjust service provision for this population. Given the need to implement tailored services within home visiting programs for families impacted by SUDs, we sought to investigate the implementation barriers and facilitators to inform future integration of a relationship-based parenting intervention developed specifically for parents with SUDs (Mothering from the Inside Out) into home visiting programs. We conducted nine interviews and five focus groups with a racially diverse sample (N = 38) of parents and providers delivering services for families affected by SUDs in the USA. Qualitative content analysis yielded three most prominent themes related to separate implementation domains and their associated barriers and facilitators: (1) engagement, (2) training, and (3) sustainability. We concluded that the home visiting setting may mitigate the logistical barriers to access for families affected by SUDs, whereas relationship-based services may mitigate the emotional barriers that parents with SUDs experience when referred to home visiting programs.

Keywords: parental substance use disorder, relationship-based parenting intervention, home visiting, implementation, barriers, facilitators

Infants and toddlers who are prenatally exposed to substances may demonstrate a variety of developmental concerns including motor delays (Hans & Jeremy, 2001; Yeoh et al., 2019), language and cognitive delays (Beckwith & Burke, 2015; Skumlien et al., 2020), and emotional and behavioral problems (Hall et al., 2019). Participation in home visiting programs, such as Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Programs or Part C Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Early Intervention, is related to positive developmental outcomes for infants and young children who were prenatally exposed to substances (Frank et al., 2002), highlighting the importance of implementing these services with this population of high-risk families. However, families impacted by substance disorders (SUDs) frequently face unique challenges engaging in home visiting services such as stigma, fear of child welfare involvement, and mistrust (Peacock-Chambers et al., 2020; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2019), thus limiting the potential benefit of these programs. One key method for increasing family engagement and mitigating the negative effects of prenatal substance exposure on child development is to address parental mental health and its impact on parent-child relationships (Ko et al., 2017). Providing parenting supports in settings that are most accessible to families (e.g., in the home) may also increase receipt of integrated parental mental health treatment that ultimately benefits children (Zhou et al., 2019).

Although helpful in decreasing psychiatric symptoms and increasing abstinence, adult mental health and substance use treatment alone is not sufficient to improve child and family outcomes (Barth et al., 2006; Choi & Ryan, 2007; Dore & Doris, 1998; Niccols et al., 2012). In contrast, treatment programs that view women with SUDs more holistically and focus on nurturing their roles as mothers tend to have long-lasting and meaningful positive outcomes including decreased maternal depression, decreased parenting stress, higher likelihood of substance use treatment completion, fewer new reports of child abuse or neglect, better adherence to routine well-child care, increased dyadic reciprocity, enhanced caregiving sensitivity, and improved child attachment security (Dore & Doris, 1998; Hanson et al., 2019; Pajulo et al., 2011; Suchman et al., 2004; Suchman et al., 2017). Similarly, child-focused programs that integrate parental mental health supports demonstrate direct and indirect benefits to the child including improved parenting strategies, decreased maternal distress, decreased child behavior problems, and more secure parent-child attachment (Lieberman et al., 2006; Shafi et al., 2019; Suchman et al., 2017).

The selection and implementation of services for families impacted by SUDs within home visiting programs should be considered thoughtfully. Several studies suggest that commonly used psychoeducational, behavioral, and skills-based approaches may not lead to the desired lasting improvements for families impacted by SUDs on important indices of family bonding, family conflict, children’s prosocial skills, children’s perceptions of their parents’ love and involvement, and children’s risk for developing SUDs later in life (Catalano et al., 1999; Haggerty et al., 2008; Kumpfer, 1998; Suchman et al., 2004; Suchman et al., 2006). This is likely related to a multitude of factors. Notably, many widely available skills-based approaches rely on teaching or coaching parents to engage in caregiving behaviors thought to support child development. However, these approaches typically focus on addressing child behavior without resolving the underlying causes of the parenting challenges experienced by mothers with SUDs. Substance use may be initiated in an attempt to cope with or tolerate psychiatric illness or symptoms, or to self-regulated difficult affect. Simply coaching mothers with SUDs to engage in caregiving behaviors such as co-regulation, time-out, and limit-setting may be particularly difficult for mothers in recovery, may even elevate stress, and trigger cravings for substance use (Rutherford et al., 2011). Service providers and parents have previously identified the potential need for service provision to this population to require a paradigm shift from child-focused services toward family-oriented services in order to enhance the emotional quality of the parent-child relationship (Peacock-Chambers et al., 2022).

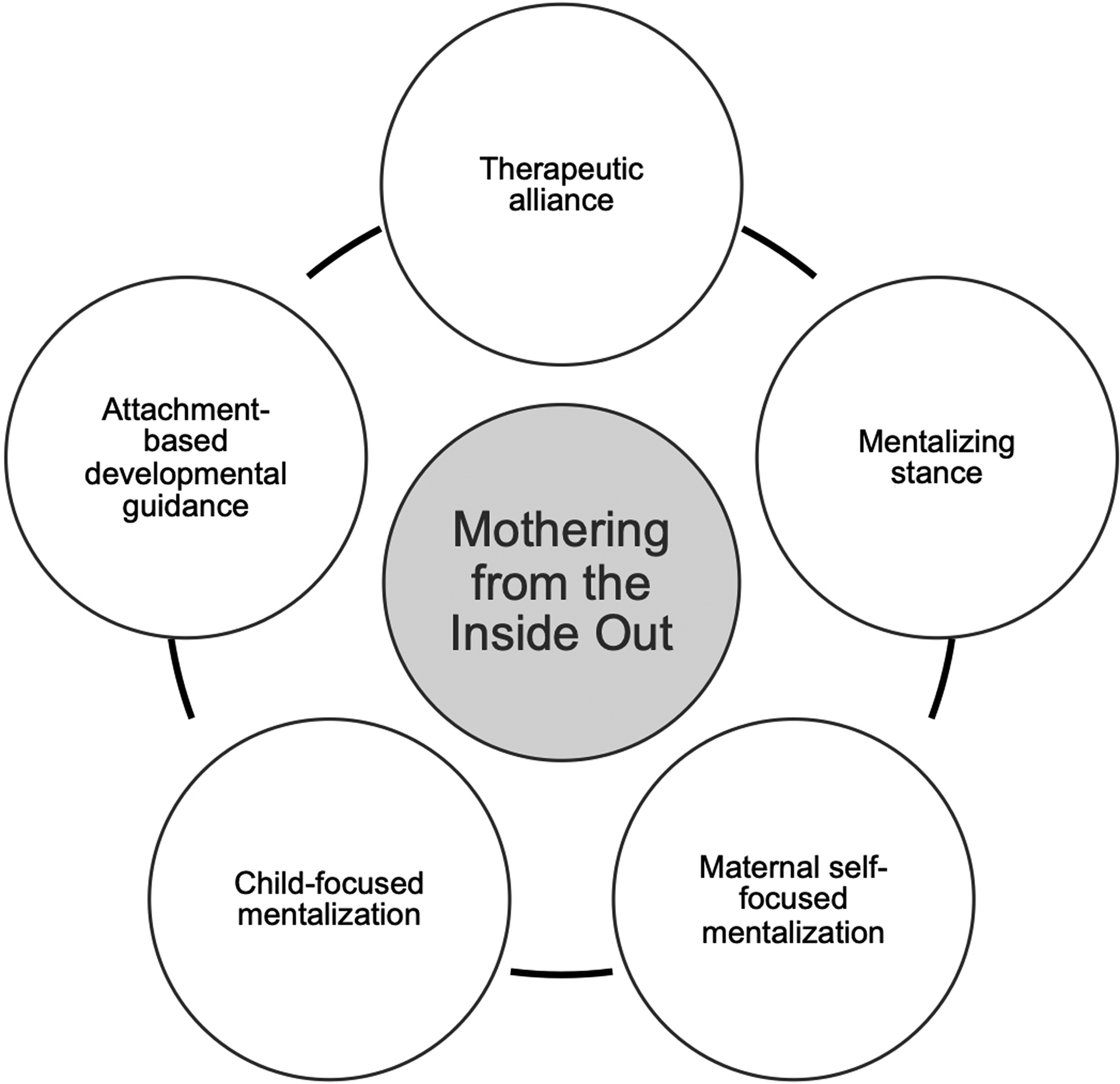

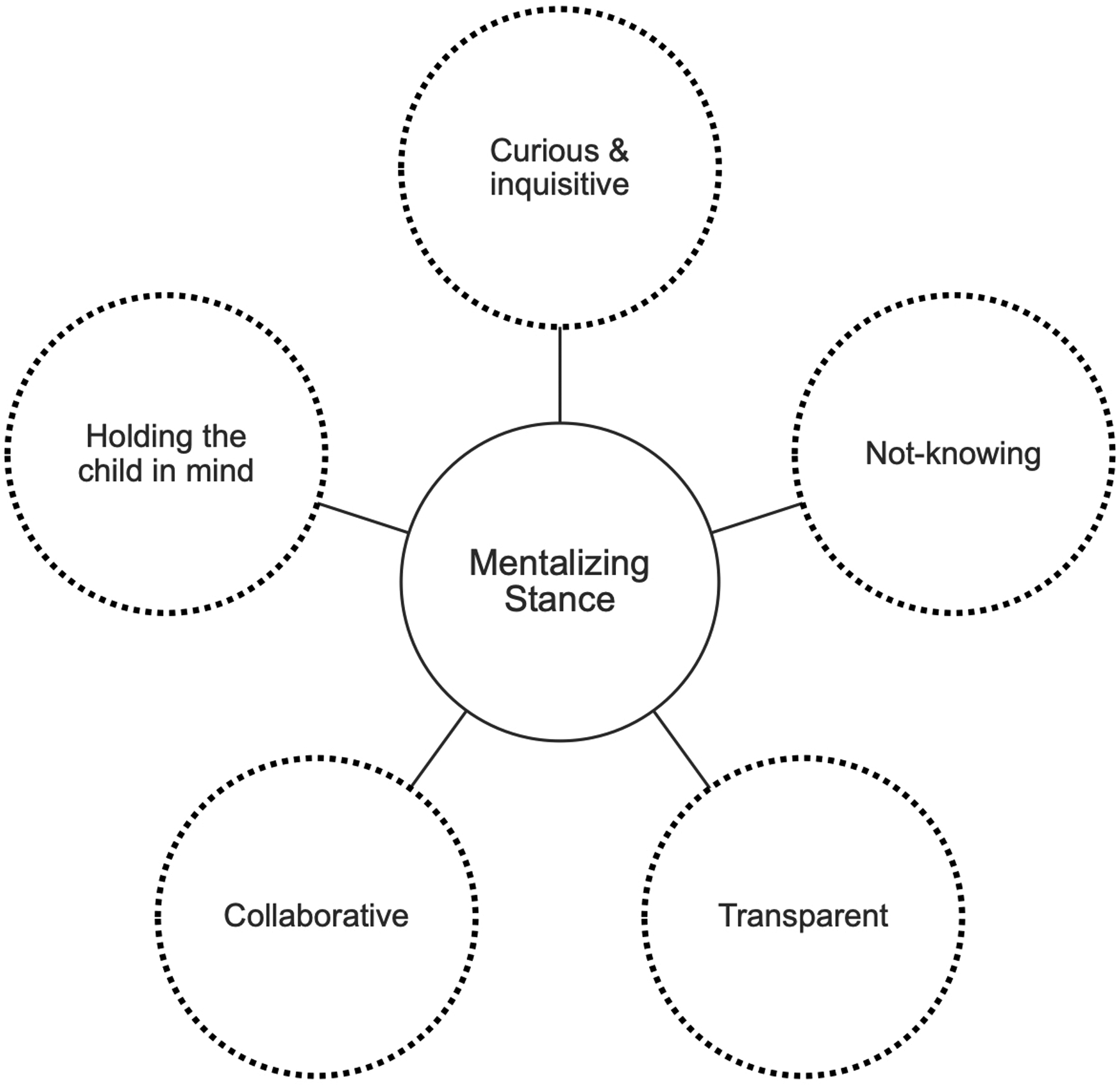

Mothering from the Inside Out (MIO) is one such approach specifically designed for mothers with SUDs that has the potential to be integrated into home visiting programs to improve the quality of mother-child relationships in dyads affected by substance use. MIO is a 12-week, individual approach to parenting intervention that fosters a mother’s capacity to mentalize, or make sense of behavior in terms of underlying mental states (Allen et al., 2008). MIO specifically targets mothers’ parental reflective functioning, or her ability to meaningfully and accurately understand the thoughts, emotions, wishes, and attachment needs that drive her child’s behavior and her own caregiving behavior (Slade, 2005). Grounded in the principles of reflective parenting programs first described by Slade (2007), MIO directly addresses parental reflective functioning by engaging the mother in explicit discussion about what her child’s behavior may be trying to communicate, how this makes her feel, and how these emotions impact her caregiving. This is achieved by building a safe and strong therapeutic alliance, maintaining a reflective stance, supporting mothers’ self-focused mentalization, facilitating mothers’ child focused mentalization, and providing attachment-based developmental guidance (See Figures 1 and 2). The ultimate goal is to improve the emotional quality of the parent child relationship by increasing the mother’s interest and curiosity in her child’s internal world (Suchman et al., 2018; Suchman et al., 2013; Suchman, 2016; Suchman & DeCoste, 2018). Previous trials testing MIO have demonstrated its efficacy at improving parental reflective functioning, caregiving sensitivity, maternal depression and substance use, and children’s positive involvement with their mothers during dyadic interactions (Suchman et al., 2008; Suchman et al., 2010; Suchman et al., 2011; Suchman et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

MIO Core Components

Figure 2.

Mentalizing Stance

Although originally designed as an adjunct to outpatient addiction treatment and previously studied in the SUD treatment setting (Suchman et al., 2008; Suchman et al., 2010; Suchman et al., 2011; Suchman et al., 2017), we proposed that child or family-focused home visitors with training in counseling or therapy could also feasibly deliver the intervention in the home setting. Feasibility and acceptability of an evidence-based intervention in a new context are important implementation outcomes to consider (Proctor et al., 2011). Such outcomes help to ensure a goodness of fit between the proposed new intervention and the treatment setting. However, many factors about this treatment setting, provider training, and the broader home visiting systems and culture must first be carefully understood in order to optimize implementation of this intervention.

Implementation frameworks can be particularly useful in guiding the adaptation of evidence-based practices for existing service settings (G. A. Aarons et al., 2012). The EPIS (Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment) framework in particular stresses the importance of dedicating sufficient time and resources to understand the treatment setting and to adequately prepare and adapt the intervention to meet the needs of that setting prior to implementation (G. A. Aarons et al., 2011). This can improve the implementation process upon its introduction and avoid wasted efforts and resources on costly implementation attempts (Saldana et al., 2012). Thus, through the use of a community-engaged research approach, we sought to identify the most salient implementation considerations needed for integrating MIO into the home visiting setting. We employed qualitative methods identify themes related to potential implementation barriers and facilitators. Knowledge gained from this study is needed to understand whether integration of MIO into home visiting services is likely to be feasible and acceptable, and which adaptations or specific implementations strategies are needed in the implementation process.

Methods

Participant Recruitment

We employed a community-engaged research approach in the design, participant recruitment, data collection, and analysis of this qualitative study. We recruited participants (i.e., parents in recovery from SUDs, home visiting program providers, and directors, physicians, nurses, social workers, child welfare staff, and addiction treatment providers) via local perinatal collaboratives and coalitions focused on improving healthcare for pregnant and postpartum mothers with SUDs in several urban and rural communities in western Massachusetts. Members of the research team distributed study advertisements and contact information to members of perinatal coalitions at in-person meetings and through email list serves. Staff members at the same community organizations represented in these coalitions also subsequently distributed flyers to other potentially interested parents. Members of the research team screened potential participants who expressed interest in participating to ensure that they were English-speaking and at least 18 years old. To be eligible, parents also had to identify as people with lived experience with SUDs, and providers had to have experience working directly with families affected by SUDs. We provided eligible participants with the option to participate in a focus group with lunch provided, or in an individual interview at a time of their choice. Interviews and focus groups have different methodological strengths and weaknesses when discussing potentially stigmatizing topics (Ruff et al., 2005). For example, focus groups provide insight into social norms as well as observation of interactive discussion between group members. However, logistical challenges associated with focus group participation, particularly for under-resourced communities, can be a barrier to enrollment particularly for parents in recovery. Therefore, we offered participants the choice for either form of participation based on preference, availability, and logistical considerations. We conducted the focus groups and interviews at healthcare facilities, community-based service organizations, or participant’s homes, and compensated participants for their time with a $50 gift card. We screened 43 potential participants and recruited participants until thematic saturation was achieved (N = 38). This study was approved by the Baystate Medical Center Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt based on the minimal risk posed to study subjects.

Data Collection

Participants met with the PI (E.P.C.) and one or more additional study team member(s) to complete verbal informed consent, an interview or focus group, and a brief written questionnaire. Interviews ranged from 30 to 60 minutes in length, and focus groups ranged from 90 to 120 minutes in length. Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded, and field notes were handwritten or typed by the PI and an additional study team member.

At the time of each interview or focus group, participants were first informed that the research team was proposing to integrate and deliver services specifically tailored for parents in recovery from SUDs within the context of home visiting programs, particularly Part C Early Intervention or other similar programs. Participants were provided with a description of Mothering from the Inside Out (MIO), a relationship-based reflective parenting intervention specifically designed for parents in recovery from SUDs (Figure 1 and 2). Participants were also provided with a summary of MIO’s evidence base, including findings from multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrating MIO’s efficacy at improving the parent-child relationship as well as children’s interactional behavior and attachment security, mothers’ caregiving behaviors, and mothers’ substance use and psychiatric symptoms (Suchman et al., 2008; Suchman, 2017; Suchman et al., 2010; Suchman et al., 2011; Suchman et al., 2017; Suchman et al., 2016). Lastly, participants were provided with some background about the similarities and differences between MIO and behaviorally-based parenting interventions that are widely available but potentially less efficacious among parents with SUDs at improving the parent-child relationship (Suchman et al., 2004; Suchman et al., 2006).

After learning about MIO and reading a passage from a parent about what they gained from MIO (Suchman et al., 2013), participants were asked two primary questions: “What is your initial reaction to the information you just heard?” and “How would the program need to be adapted to meet your needs (or the needs of your community)?” Additional probes focused on potential individual and program level challenges that could arise during integration of the intervention into the home visiting setting. Probes were informed by a conceptual model of service engagement developed in prior qualitative work and the EPIS implementation framework (Gregory A Aarons et al., 2011; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2022). The conceptual model describes the interaction of important factors that drive perinatal service engagement among mothers with SUD and informed the need for more in-depth questions about home visiting. Demographic data were collected at the conclusion of each interview and focus group. Recruitment continued until thematic saturation was achieved, i.e., when no new themes emerged in the final interviews or focus groups.

Data Analysis

Recordings were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were coded independently by two members of the research team. NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) was used to organize the analysis, which included inductive and deductive analytic codes and corresponding definitions in a codebook (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Deductive codes originated from the EPIS framework and conceptual model referenced above while inductive codes allow for exploration of unforeseen concepts that may be important in this particular context. Coders met biweekly to resolve discrepancies between codes until consensus was achieved. The codebook described definitions for specific codes, and memos were used to document discussion of the codes. Themes were iteratively identified through open coding, with monitoring for thematic saturation. Deductive codes and thematic analysis were guided by the EPIS implementation framework (Gregory A Aarons et al., 2011). Interviews and focus group data were analyzed together using the same codebook a thematic analysis process. A descriptive thematic analysis, themes, and sub-themes are reported below (Boyatzis, 1998).

Results

Participants

Five focus groups and 9 individual interviews were conducted. Participants included 25 providers (i.e., home visiting staff and directors, physicians, nurses, social workers, addiction counselors, and recovery coaches) and 13 parents in recovery from SUDs. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Home visiting programs represented included Early Intervention, Head Start, Healthy Families, Parents as Teachers, and in-home therapy. Participants came from racially diverse urban areas as well as predominantly white rural areas in [state], however individual race/ethnicity data was not collected.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics – Focus Groups and Interviews

| Work Experience Mean Years (range) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus group | 74 | 10 | Rural | 24–63 | Substance use treatment (n=2) Healthcare (n=2) Early Intervention (n=1) Other* (n=4) Multiple¥ (n=1) |

15 (1–38) |

| Focus group | 66 | 4 | Urban | 36–58 | Substance use treatment (n=2) Healthcare (n=1) Other* (n=1) |

7 (1–15) |

| Focus group | 71 | 7 | Urban | 27–59 | Healthcare (n=1) Early Intervention (n=4) Multiple¥ (n=2) |

11 (2–20) |

| Interviews | Mean: 38 Range: 26–56 |

4 | Rural (n=2) Urban (n=2) |

27–65 | Healthcare (n=1) Early Intervention (n=2) Multiple¥ (n=1) |

15 (4–26) |

| Demographic information primary language, number of children (range), education | ||||||

| Focus group | 30 | Father (n=1) Mother (n=1) |

Urban | 27–30 | English speaking (n=2), 2–2 children, 10th grade (n=1), some college (n=1) | |

| Focus group | 35 | Mothers (n=6) | Rural | 20–48 | English speaking (n=6), 1–3 children, 10th grade (n=1), some college (n=1), college graduate (n=2), graduate school (n=1), unknown (n=1) | |

| Interviews | Average: 36 Range: 25–45 |

Fathers (n=2) Mothers (n=3) |

Rural (n=0) Urban (n=5) |

25–45 | English speaking (n=4), other language (n=1), 1–6 children, 7th grade (n=1), GED/high school graduate (n=2), some college (n=2) | |

Other occupations included: Child welfare services, department of public health, home visiting programs, Early Head Start, social work, outreach specialist/case management.

Multiple occupations included: Developmental Specialist, Parent Educator/Home Visitor Specialist and Recovery Coach, clinical social worker, mental health counselor and supervisor, and registered nurse.

Themes

Analysis of implementation considerations for integration of MIO into the home visiting setting resulted in the emergence of three primary themes: (1) engaging families affected by SUDs, (2) preparing the clinical team, and (3) ensuring sustainability, as well as several corresponding sub-themes. Each theme and its corresponding sub-themes are presented in Table 2 and described below in more detail.

Table 2.

Implementation Considerations for integrating Mothering from the Inside Out into home visiting settings

| Implementation Considerations Themes & Subthemes |

Barriers | Facilitators | Future Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Engagement - Engaging families affected by SUDs | |||

| 1.1 Thoughtfully framing MIO to families impacted by SUDs | Parents believe home visiting is only for children with delays or developmental disabilities Engagement in home visiting services can trigger feelings of guilt Parents do not distinguish among parenting interventions |

When MIO is described in detail, parents are more receptive | Inform local opinion leaders Identify and prepare champions Involve patients/consumers and family members Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants Conduct educational outreach visits |

| 1.2 Building strong therapeutic relationships | Home visiting programs have not traditionally succeeded in retaining families impacted by SUDs Parents report experiencing judgement and stigma by child-serving systems Parents may not have experienced strong healthy relationships in childhood |

Clinicians recognize the importance of building strong therapeutic relationships MIO focuses specifically on supporting the development of a strong relationship |

Obtain and use patient/consumer and family feedback |

| 2. Training - Preparing the clinical team | |||

| 2.1 Training in attachment, mentalization, and reflective functioning | Providers have variable background in attachment and reflective practice Home visiting programs employ behavioral, psychoeducational, parent coaching approaches |

Clinicians have strong background in child development Home visiting programs have adopted models that emphasize the parents’ role in their children’s development |

Conduct ongoing training Make training dynamic Provide clinical supervision Create a learning collaborative |

| 2.2 Training in SUDs | Providers have variable formal training in treating individuals with SUDs | Clinicians may already have on-the-job experience working with families impacted by SUDs | Conduct ongoing training Make training dynamic Provide clinical supervision Create a learning collaborative |

| 2.3 Training in trauma and adult mental health | Home visiting programs have traditionally been child-focused Home visiting agencies may attract professionals who are more interested in working with children than parents |

Clinicians recognize the role of parents’ mental health in their children’s development MIO includes components that can be integrated into the work of non-mental health providers |

Conduct ongoing training Make training dynamic Provide clinical supervision Revise professional roles Create a learning collaborative |

| 3. Sustainability - Ensuring sustainability | |||

| 3.1 Establishing a relational framework within the home visiting system | There are important differences between MIO and parent coaching models that have already been widely adopted within EI | Clinicians are open to learning how to implement more holistic, family-focused services | Provide ongoing consultation Build a coalition |

| 3.2 Ensuring appropriate funding and staffing | State agencies have limited funding Clinicians are overburdened There is frequent staff turnover at home visiting agencies Cost of training new providers |

MIO would be a billable service Providers expressed desire to share knowledge and training resources |

Fund and contract for the clinical innovation Make billing easier Develop resource-sharing agreements Use train-the-trainer strategies Build a coalition Create a learning collaborative Centralize technical assistance |

| 3.3 Capitalizing on the flexibility of service provision | Services begin after a child is born | Home visiting services like EI can have up to a 3-year duration Location of service provision is flexible Ability to involve both mothers and fathers |

Place on fee for service lists/formularies |

Theme 1: Engagement - Engaging Families affected by SUDs

Thoughtfully Framing MIO to Families Impacted by SUDs

A primary barrier to overcome in terms of bringing MIO into the home visiting setting was the perception by parents with SUDs that home visiting programs are meant for children with developmental problems. This was particularly true of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Part C Early Intervention (EI) programs, that are available to children with or at risk for developmental delay. One EI provider indicated that many parents with SUDs refrain from engaging in EI because “it makes them sound like their kid has special needs.” Another provider indicated that “I’ve seen mothers in recovery, they’re so anxious about the fact that ‘something that I’ve done has hurt my child.’ And we’re a reminder that maybe it did.” One mother in recovery echoed this sentiment firsthand and offered a solution:

I think a lot of people think Early Intervention is just for kids with disabilities, because that’s what I used to think, when it’s a lot more than that. So I feel like putting this program in it as well would really give it like, “Okay, Early Intervention has this as well. It’s not just for kids with disabilities or developmental issues.”

Overall, parents and providers stressed the importance of framing home visiting as a support that could be beneficial to many types of families with infants and toddlers.

In order to shift the perception of programs like EI, participants indicated that home visiting programs would need to be extremely thoughtful in how they described and presented MIO to parents in recovery. The importance of engaging families thoughtfully was echoed by mothers with SUDs who indicated that they are frequently offered programs that are not clearly distinguishable: “I feel like everybody is trying to do the same thing but put a different name on it… but it’s all the same.” This perception by parents about the redundancy of parenting programs appears again when mothers describe how they are not getting anything new out of the programming they are being offered, suggesting the need to be extremely thoughtful and intentional when marketing MIO in order to lessen parental concerns. One mother said:

It seems like there’s so much that we’re missing, you know? We keep readdressing the same things over and over, and rehashing the same things over and over again. It’s not going to make a difference in the outcomes. Somebody really needs to think outside the box and really come up with some ideas, you know? What we’re doing isn’t really working in my opinion.

When described to families in detail, mothers and fathers with SUDs were extremely open to the MIO framework and could see its strong potential within home visiting.

Ultimately, however, if home visiting programs were to begin to have the opportunity to provide MIO to families, participants emphasized the need for a concerted effort on the part of programs to overcome preexisting perceptions of these programs and to describe how MIO may be different from traditional service delivery models. One solution involved selecting who should provide families with a description of MIO. For example, one father expressed that he would feel most receptive to MIO if it were presented to him by his addiction treatment providers because “my providers know about my addiction and aren’t judging me.” Similarly, one mother in recovery noted that “the best kind of people to reach people [in recovery] are people that understand and have been through it.” Another mother suggested:

The initial meeting where you guys are bringing it on to a person – have that person [who has already completed MIO] come in and be like, ‘Well, hey, you know? I’ve been in this program for this long. This is what it did for me’ … And it might even help them be like, ‘Good. You know what? This could end up great.’

Participants repeatedly emphasized that parents with SUDs may be more likely to engage in services if they were to learn about MIO from a peer they perceived as trustworthy or someone who had previously participated in the intervention and experienced positive results.

Building Strong Therapeutic Relationships

When engaging families with SUDs, providers recognized the importance (and challenge) of building strong therapeutic relationships: “Once we get them in Early Intervention, it’s a really hard population to keep… it’s really hard to build that relationship.” Fortunately, providers were able to make good guesses about the reasons that families with SUDs had difficulty engaging with home visiting programs, including previous experiences of judgement and worries about stigma. One provider described the therapeutic relationship as a remedy to these challenges:

I also feel that when a parent is coming from a background where they’ve dealt with substance use issues, they probably have more of a history of being judged by service providers… and systems that are supposed to be helping systems. And I wouldn’t want to come in and kind of portray [the MIO approach] as another one of those sorts of experiences and I think that having that kind of rapport-building and really ‘What can we do to support you because this is about you and your family and not us and whatever agenda we’re coming in with.’ I think it’s helpful to have that piece in place, particularly when you do have a vulnerable client who may have a history with helping systems that is not so great.

Parents with SUDs agreed that building a strong therapeutic alliance was a key starting point, with one mother in residential substance use treatment noting that “I’m very open to things when it’s genuine.” More specifically, mothers indicated that building a strong relationship made it possible to do meaningful therapeutic work: “I’ve definitely come to the point where I’ve actually gained a lot of good relationships with all of my service providers… So, we actually talk about all of these things.”

Finally, the need for building strong therapeutic relationships with parents was highlighted by several parents’ indication that their childhoods were not characterized by supportive or healthy relationships. One mother noted that MIO would be beneficial given that “especially parents in recovery need to hear those kinds of things, because we never really—some of us didn’t have the upbringing.” The experience of building a strong therapeutic alliance with an MIO clinician was therefore additionally seen as a way for parents to build skills for forming other healthy relationships within the family or the larger community that they could then call upon in times of need.

Theme 2: Training - Preparing the Clinical Team

Training in Attachment, Mentalization, and Reflective Functioning

The second theme that participants identified as a critical focus for integration of MIO into home visiting programs was the preparation of the team. Participants emphasized various training needs that providers would require to be well-equipped to work with families impacted by SUDs. Specifically, given that many members of home visiting teams (e.g., physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, special educators) may not have formal training or background in providing mental health counseling, it was suggested that in addition to training social workers in MIO, it would also be necessary to give all home visiting providers on a team an “understanding of attachment theory and… some language around helping parents to kind of reframe what they think maybe their child is saying to them” (Provider). While providers felt confident in delivering many forms of developmental services and parent skills training, the task of fostering parents’ ability to reflect on their own and their children’s mental states was regarded as potentially new for some providers.

Notably, providing greater training in attachment theory and mentalization was seen as a way to boost providers’ confidence and competence in working with families impacted by SUDs, particularly when providers are new to the field. One provider gave an example of what she might say to a parent, and the potential value of the MIO framework: “‘Let’s think about what might be happening in that moment? Let’s try to imagine what your child’s going through’… I think a lot of staff, especially young staff, feel a little stuck by not knowing that piece of it.” MIO was thus seen as a framework which could supply providers with concrete techniques for fostering a reflective stance in parents.

Training in SUDs

Home visiting providers recognized that despite their high educational attainment and advanced practical training, their background in child development had not fully prepared them to work with families impacted by SUDs. As the number of these high-risk families enrolled in home visiting programs such as EI have increased with the rise of the opioid epidemic, providers acknowledged their need for additional specialty training in SUDs:

I’ve been in Early Intervention for 35 years, and it’s been in the past 10 years that I’ve had to shift my practice… ‘cause I haven’t had this population in such numbers before, and learning skills that I haven’t previously had to have… we need more training in how do we work with this population.

Parents with SUDs were in agreement that they would benefit from providers having additional background in and understanding of SUDs. They saw this as a key component of establishing a strong relationship which could lead to other meaningful work: “Having that service provider be… a recovery coach in a way… I could see it may be helping that initial bond and comfort to want to continue the program and being able to open up with that person.” In this case, the mother thought that parents with lived experience of their own SUDs could help bridge connections to the service and develop a bond with home visitors.

Similarly, participants recognized the importance of providing evidence-based intervention in the context of an understanding, validating, and judgement-free environment. In particular, one NICU nurse mentioned the value of providers developing their own tools to mentalize for the parents with whom they are working: “I absolutely think [providers] need training on addiction as a disease, as well as sensitivity training. You’ve got to make it relevant to the workers and give them the tools to check their judgments at the door.” In other words, training in SUDs was seen as a stand-alone training need, as well as an integral component of reflective practice.

Training in Trauma and Adult Mental Health

Some providers also acknowledged that in addition to training in the area of SUDs, more general clinical background was needed to work directly with parents through MIO: “Historically, the [home visiting] system’s been a child-serving system, so the people who are employed in it are more oriented towards serving kids rather than parent[s].” Training in adult mental health was also seen as necessary given the overlap between SUDs, other psychiatric disorders, and their impact on child development. One recovery coach summarized: “We often run into co-occurring disorders. We have this, we have that, and we have this, and they all play a role in a person’s recovery and success.” Providers were aware of their varying levels of training and comfort in the mental health issues that often occur alongside SUDs:

There’s such a diverse professional background of all of the different disciplines within EI and some folks probably had a heavier training background in substance use and some people might have had none. So… it might be helpful to have that additional background in substance use, substance abuse, and the mental health issues that surround that, as well.

Notably, participants acknowledged the potential role that trauma may be playing the in the mental health and parenting behaviors of mothers and fathers with SUDs. As a result, they saw the need for training in how to support families impacted by trauma: “I’m a firm believer if you’re going to have … people working with families, to have them well-trained and well-versed in dealing with situations like trauma” (Provider). In addition to childhood trauma that parents may have experienced, it was suggested that providers would also need to have an understanding that many parents with SUDs had experienced trauma in the form of child removal by child protective services: “It did ruin everything, I lost my job, my car, everything, and I lost my dignity on top of it… I had to really fight a lot of bullets… just to get my kids” (Mother). This experience (or even the potential of this experience) was enough to induce significant fear in parents which in turn impacted their willingness to engage in home visiting programs:

I’m so afraid of what’s going to happen to me, what’s going to happen to my children, the displacement possibilities, you know, the foster care system, the – just everything, everything is frightening. That parent, the parent who is sitting there not knowing which way to go, what’s the right thing to do at this point, who is scared to make the right move, that’s the parent that needs the help the most.

Participants were hopeful that the reflective nature of MIO could facilitate parents’ recognition and regulation of their anxiety and the ways in which it may be impacting caregiving capacities and relationship with their child.

When discussing the role of trauma and adult mental health in the lives of parents with SUDs, providers expressed concern about whether services like MIO fell beyond the scope of home visiting programs: “Because if they’re bringing this trauma up and they’re speaking about things that they’re really not ready to speak about, then who’s going to provide that emotional support?” In fact, one provider noted that “a lot of us are not counselors or therapists or maybe not that comfortable going to that place with a family or a parent.” Given the interdisciplinary nature of programs like EI, some participants questioned how much involvement with parental mental health fell within their services designation and skillsets. As a result, other members of home visiting teams (e.g., physical therapists, occupational therapists) wondered how they might still integrate core components of MIO (such as building a strong therapeutic alliance and maintaining a mentalizing stance) within their work in order to support parental mental health and the parent-child relationship, even if their role did not involve the direct provision of mental health counseling.

Theme 3: Sustainability - Ensuring Sustainability

Promoting a Mentalization-based Relational Framework within Home Visiting Programs

In order to ensure sustainability of MIO within home visiting settings, participants acknowledged that a relational framework would need to be consistently prioritized in their programs. Although programs such as EI have already begun the shift toward a more relational approach, there were apparent differences in the current model and the MIO framework being proposed. In particular, the focus of MIO is on building parents’ reflective capacities so they may begin to understand their own (and their child’s) thoughts and emotions, how thoughts and emotions are impacted by interpersonal interactions and past experiences, and how mental states impact behavior. This is in contrast to other widely used models which encourage parents’ and children’s confidence, competence, and mutual enjoyment through the facilitation of parent-child interaction. One provider described her perception of the differences between the MIO approach and the current model of service delivery, as well as how MIO would be particularly beneficial for parents in recovery from SUDs:

The ability to help [the] parent to be able to reflect on their parenting is so critical. And building that level of insight is not easy, especially for a lot of the parents where substance abuse has been part of their background… You’re helping parents to be able to step back by asking them reflective questions, by encouraging them to think, “What was that about?” The ability to analyze perhaps their own feelings or be empathetic with their child [by] saying, “What do you think your child was feeling in that moment?”… You’re helping the parent to understand and you’re helping the parent to learn… You’re helping them to really be mindful of how it is that they act, [and] how they react.

Generally, when the specific goals and nuances of the MIO approach were made explicit, participants expressed an appreciation of how it differs from the general approach across the broader home visiting program and how it could potentially be impactful for parents with SUDs.

Fortunately, providers expressed openness to learning and willingness to provide relationship-based services to complex parent-child dyads: “We work with the whole family. Our focus is yes, the child, but our focus really is the family. That’s how Early Intervention works now.” Additionally, there has been a recent shift at the governmental level away from providers engaging in direct service provision with children, to instead focus on empowering parents to interact with their children therapeutically and in ways that will facilitate optimal development: “This falls within [the] model that [the department of public health] is kind of pushing for EI right now… it fits the model that they’re trying to institute across the state” (Provider). Providers also indicated that they were comfortable with taking a relational approach, and they expressed familiarity with describing this type of approach to families.

Ensuring Appropriate Funding and Staffing

Participants expressed concern regarding how MIO would be funded long-term. They expressed enthusiasm and desire to keep it sustainable but raised several possible barriers to its implementation given the financial position of state agencies. Participants emphasized that limited funding often equates to limited personnel. One provider expressed that home visiting agencies and their employees are strained as-is— without adding a new framework to their workload: “We are chronically short of staff. So while I love an intensive model, and I think there are populations that really would benefit, we’re not positioned in a place where we have more to give” (Provider). In addition, these staffing constraints are amplified by frequent staff turnover which raised concern (and solutions) about the costs of training new providers:

I think staff turnover is a big thing because we have had several staff that have been trained in these different areas and have then left and gone to other programs or gone on back to school, gone to other areas… What are we able to do after that? It’s kind of a big expense up front, and [how] are we able to then sustain that with the model that we have? I think a train the trainer model would be beneficial.

Ultimately, participants believed that “the services themselves are somewhat self-sustaining because they’re [billable], so providing the service itself [is not a problem], it is the training that is the cost that might be more difficult” (Provider).

Additional creative solutions to reduce financial burdens placed on individual agencies included fostering collaborative relationships among local and state organizations. One provider indicated the importance of “making sure that knowledge is passed down… [through] a statewide collaboration” in which home visiting programs could share centralized resources for training. In addition to sharing resources, others noted the importance of sharing ownership of the task of helping families impacted by SUDs rather than assuming that any one type of service bears sole responsibility for children impacted by prenatal exposure: “If you’re looking to keep it sustainable, you could convince [multiple] state agencies that it’s worth collaborating around, I think that would offset the cost hugely… because they’re all our kids” (Provider). It became evident that inter-agency collaboration was seen as particularly valuable given that various types of programs may touch the lives of families living with SUDs at different points in time (e.g., prenatally, postnatally, early childhood): “that’s gonna make it more sustainable as well- if it’s carried across systems” (Provider). Simply put, it was suggested that “we share our resources financially… as well as the expertise everyone has throughout this journey” (Provider).

Finally, when discussing the impact of funding in the quest to scale these services and meet the needs of more families impacted by SUDs, some participants brought up the need for equitable access to MIO among further marginalized populations, including families of color. Notably, one provider stated worry about a “lack of services that are typically provided to communities of color because there are large barriers to access, either insurance or state-based, on subvert-prejudicial grounds… I want to see it flourish and actually be used in an equitable way.” Participants recommended the need for a concerted effort to address inequity in access to the intervention and home visiting services across different racial and ethnic communities when planning the integration of MIO.

Capitalizing on the Flexibility of Service Provision

One factor that emerged as a way of ensuring the sustainability of MIO was the overall flexibility of the home visiting system. This flexibility came in many forms, including duration, location, and inclusion of multiple child caregivers. With respect to duration, home programs are not as time-limited (i.e., birth to 3- or 5-years) as the treatment period in previous MIO efficacy trials (12 weeks). Providers thus indicated optimism that greater treatment progress could possibly be achieved over a longer period of time working with a family: “We follow kiddos for three years… Early Intervention could be an ideal place to have ongoing [support], not just 12 weeks.” One recovery coach noted: “I think longer would absolutely be better because it’s just a blip on the radar of what’s gonna happen because brain chemistry changes, I mean, everything [changes] for moms, everything.” Flexibility of the location of treatment delivery was another important benefit of providing MIO within home visiting programs, with one mother indicating: “A lot of people in recovery, especially early in recovery, they don’t have vehicles… Just convenience-wise and bringing their kids out, it’s just a lot more comfortable for them in the home. Some people don’t have transportation.”

Another area in which the flexibility of home visiting programs was seen as beneficial to the sustainable implementation of MIO included the ability to involve both mothers and fathers. Interventions such as MIO are often implemented in female-dominant settings (such as residential treatment facilities for pregnant and parenting women), thereby excluding fathers, if unintentionally. For example, one father described how his role as a parent was often neglected as a treatment need: “I’ve always just gone to therapists myself… I’ve gone to AA, you know, NA… But as far as parenting, no.” Another father highlighted the importance of including fathers as well as the universality of MIO: “The program should be both [mothers and fathers]. The same [intervention] you would give mom at counseling… that would be the same intervention I would take.” Given that a majority of home visiting programs do not have constraints about which parents may participate, it was therefore seen as an ideal setting to touch all caregivers in a child’s life.

In contrast to the ways in which home visiting programs were described as flexible, one major limitation in the flexibility of some home visiting programs, specifically EI, included a generally standard protocol of beginning services after the birth of the child. Both providers and parents wished programs such as EI could be begin prenatally. There were several reasons for this, including providing emotional support to mothers with SUDs during labor and delivery, a time that is often complicated by fear and uncertainty: “my experience with moms here at the hospital is that they come with so much anxiety” (Provider). Participants also saw value in beginning services “ideally before the baby is born so the [therapeutic] relationship is established” and can continue seamlessly during the stressful transition to parenting a newborn.

Discussion

Given that families impacted by SUDs have shown a need for tailored services within home visiting programs in order to improve engagement and child development outcomes, we sought to determine potential barriers and facilitators that would inform implementation strategies for integrating an evidence-based parenting intervention designed specifically for parents with SUDs: Mothering from the Inside Out (MIO). Exploration of potential barriers and facilitators prior to delivery of a new intervention is an important step in adaptation and implementation meant to ensure appropriateness of fit between the intervention and setting, optimize implementation, and avoid wasted resources and efforts in failed implementation attempts (G. A. Aarons et al., 2011; Saldana et al., 2012). We anticipated that participants would identify many barriers to integrating MIO into the home visiting setting. However, we also sought to elicit and identify potential adaptations to the integration of MIO into community settings that could be made to address these barriers. We aimed to discover which facilitators could be leveraged for successful implementation and learn about the unique ways in which home visiting programs may be well-suited for the implementation of MIO.

Overall, our results suggest the need for a variety of nuanced implementation considerations that address contextual determinants for families affected by SUDs at multiple levels of implementation. Participants’ descriptions of barriers and facilitators when adopting this new approach coalesced upon three specific implementation domains: 1) engagement, 2) training, and 3) sustainability. Within each of these three domains, we encountered potential implementation strategies across many of the six broad implementation categories identified by Powell et al. (2012): planning, educating, restructuring, financing, managing quality, and attending to the policy context. Our study further emphasizes the need to consider the emotional experiences of families and providers in order to shift organizational culture and improve receptiveness to a new framework. In this study, the engagement domain required greater consideration of emotional barriers whereas the sustainability domain addressed primarily logistical barriers. The training domain encompassed both emotional and logistical barriers, bridging the gap between the interpersonal and the organizational implementation settings (See Table 2).

The specific implementation themes that arose as most salient to support integration of MIO into the home visiting programs (engagement, training, sustainability), are frequently identified as important considerations for other community-based mental health programs (Gregory A Aarons et al., 2012; Banwell et al., 2021; Scantlebury et al., 2018; Velasco et al., 2020; Webb et al., 2021). Our findings describe nuances in these themes specific to working with families affected by SUDs as well as the implementation of a parenting intervention that is not curriculum based. As a relationship-based treatment, MIO is naturally designed to address some of the emotional barriers identified. However, the flexible content may require greater upfront investment to train providers, shift organizational culture, and ensure sustainability long-term. Below we discuss each of the three themes and the implementation considerations in greater detail.

MIO may address emotional barriers to engagement in home visiting programs

Our findings that parents with SUDs demonstrate limited enrollment and engagement in home visiting programs help us to better understand previous qualitative and quantitative studies demonstrating limited engagement in home visiting programs among this population (Peacock-Chambers et al., 2020; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2019). The qualitative findings from our current study provide a more nuanced understanding of the myriad reasons for this, namely the difficulty of introducing a new approach and building a lasting therapeutic alliance with parents with SUDs. Notably, parents’ limited engagement may be related to the possibility that the developmental assessment and treatment services that are typically associated with home visiting programs, such as EI, could confirm fears that their substance use has somehow damaged their infant. Our findings therefore highlight the importance of thoughtful marketing of services for this population in ways that address their fears and establish trust in the program, including learning about MIO from parents who had participated in it previously.

It may be possible that if a description of MIO is included in an initial explanation of home visiting services offered to families with SUDs, engagement in these services in general may be more successful. Notably, relationship-based approaches like MIO provide a roadmap to addressing barriers to engagement in home visiting programs described previously, including parents’ fear, shame, and guilt related to their substance use, parents’ perceived judgement, and parents’ difficulty feeling comfortable within the therapeutic relationship (Peacock-Chambers et al., 2020). Prior qualitative work also suggests that pregnant mothers with SUDs often hold beliefs that substance use during pregnancy can negatively impact their baby by causing birth defects and learning problems, or encouraging the intergenerational transmission of addiction (Van Scoyoc et al., 2017). The worry that one has damaged their infant has been shown to drive feelings of guilt, shame, and failure, a common experience reported by pregnant women struggling with substance use (Ehrmin, 2001; Kruk & Banga, 2011; Shieh & Kravitz, 2002; Silva et al., 2013; Söderström, 2012; Wiewel & Mosley, 2006). Interventions aimed specifically at managing these unresolved emotions within the maternal role are greatly needed (Ehrmin, 2001), and relationship-based treatments like MIO are uniquely suited to help parents manage the guilt and worry they often describe as holding them back from engaging in treatment by facilitating parents’ self-focused reflective capacity (see Figure 1) and addressing the emotional aspects of the parent-child relationship in the context of addiction.

Training providers in MIO, including how to maintain a mentalizing stance toward families (see Figure 2) may serve as a key facilitator for parental engagement in home visiting services more broadly given that it equips providers with skills to work collaboratively, demonstrate curiosity, maintain transparency, and build strong therapeutic relationships with parents in recovery. This stance could be one key factor in lessening the likelihood that parents will feel judged and avoid engaging in services. Best practice guidelines suggest that providers must be able to empathize with parents with SUDs in order to build trust, a prerequisite for meaningful recovery work to take place (McLafferty et al., 2016). Similarly, other qualitative work points to the necessity of safety within relationships between healthcare professionals and pregnant women with SUDs (Söderström, 2012) which can potentially serve as a model for secure attachment (Peacock-Chambers et al., 2020).

Beyond the capacity to empathize, our findings suggest that is also important for providers to be aware of and understand parents’ experiences of stigma (Yonkers et al., 2011) and fear of punishment by helping agencies (Jessup et al., 2003) in order to foster parents’ reflective capacities. Overall, the importance of the therapeutic relationship between parents with SUDs and their providers cannot be overstated when addressing feelings of guilt, shame and promoting engagement in services. Countless studies demonstrate the positive effects of taking a relationship-based approach with parents in recovery from SUDs (Berlin et al., 2014; McLafferty et al., 2016; Pajulo et al., 2012; Pajulo et al., 2006; Suchman et al., 2004; Suchman et al., 2006). As eloquently stated by Söderström (2012, p. 465), “Just as the child needs relational safety, acceptance and psychological availability in order to thrive, interventions must offer these mothers a safe base from which they can explore and reprocess their often troubled relational experiences, including those with drugs.”

Implementing MIO in home visiting will require both training and programmatic shifts

Preparing the clinical team to provide this relational safety for parents with SUDs emerged as another important area full of barriers and facilitators to adopting MIO. It was evident that providing high quality care to families impacted by SUDs would require training in the family-related domains of attachment, mentalization, and reflective functioning. This presents a particular challenge given previous literature suggesting that home visitors rate their confidence and competence relatively low in the area of family-centered practices as compared to other areas of their work (Bruder et al., 2011). Fortunately, our results suggest that providers are open to this more reflective way of working with families, particularly if they are provided with training and ongoing support in the work.

Importantly, our results also suggest that more training would likely be needed in the adult-focused domains of SUDs, trauma, and mental health. Our findings corroborate previous work demonstrating that patients with SUDs expressed concern that their providers had little knowledge about addiction, which made them hesitant to openly discuss their substance use and related issues (McNeely et al., 2018). This suggests the importance of training in this area even for professionals in traditionally child-serving systems. One overarching related challenge from our finding further suggests that providers who are drawn to careers in home visiting programs are often understandably more invested in child development rather than adult psychopathology. An important training consideration that may increase providers’ buy-in around learning more in this area may be framing training in SUDs and psychopathology in terms of the effects of developmental trauma. Providers may also be able gain insight into a parent’s own childhood and how early adverse experiences can influence adult trajectories in ways that shape both addiction and caregiving. In our experience, including this content area in the training of new MIO providers has the added bonus of helping to maintain a mentalizing stance toward parents with SUDs.

Fortunately, providers’ self-efficacy was positively related to the number of in-service trainings and amount of clinical supervision they received (Bruder et al., 2013), suggesting that providing training and supervision in MIO could be quite beneficial in addressing this discrepancy. Despite the great importance of training, however, previous work suggests that education in this area is not enough, and providers must also be held within safe environments by their agencies when working with parents in recovery (Söderström, 2012).

Concomitant with the theme of preparing the clinical team were the broad sustainability matters of funding and staffing. With regard to sustainability, healthcare providers noted that even with extensive training background in SUDs, they felt they would benefit from ongoing administrative and reflective supervision of their work with patients with SUDs (McNeely et al., 2018). Previous work also emphasizes the importance of ongoing supervision in predicting better treatment outcomes and confidence on the part of the provider (Dunst et al., 2011). Though helpful, these organizational practices require additional funding, a resource that is often scarce in federally funded agencies and home visiting programs. Participants in our study generated several solutions to this issue, predominantly the formation of collaborative efforts across agencies within a given state and the adoption of a train-the-trainer model.

Home visiting programs may address logistical barriers to delivering MIO

Participants also described ways in which home visiting already lends itself to the implementation of MIO. Specifically, participants noted that MIO could be successfully delivered within the home visiting setting given its flexibility in treatment location and duration, which early work suggests is extremely important for parents with SUDs (Dore & Doris, 1998). For example, literature indicates that when offering integrated support to mothers with SUDs, longer length of treatment was associated with more favorable outcomes (Conners et al., 2006). Similarly, in conjunction with longer length of services, earlier engagement was associated with greater service use, which was in turn related to favorable treatment outcomes such as decreased substance use, improved parent-child relationships, positive child development, and higher likelihood of retaining custody of their child (Andrews et al., 2018). Overall, the home visiting setting may support similarly positive outcomes by mitigating the logistical barriers to access for families affected by SUDs. Conversely, MIO may facilitate positive outcomes by limiting the emotional barriers that parents with SUDs experience when referred for home visiting services.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study recruited parents as well as providers to participate in rich discussions about their perceptions of a proposition to integrate MIO within existing home visiting programs for families affected by SUDs. We obtained valuable insight from multiple perspectives, allowing for thematic analysis, and providing directions for future research. Although our participants represented a diverse array of viewpoints, we did not collect specific race/ethnicity data to describe participants. Our findings and conclusions were also limited to what could be learned from English-speaking individuals in the northeast United States. Importantly, home visiting systems vary widely across the country, and the priorities, regulations, and organizational culture of home visiting programs, including EI, within Massachusetts may differ from those of other states. However, given that our qualitative findings are highly specific to the context and community in which our larger program of research may be embedded, we are poised to precisely address the distinct barriers and facilitators identified in this study as we conduct future research. Moving forward, studies should examine the implementation of MIO within home visiting programs, including its acceptability to both parents and providers, as well as its efficacy at improving outcomes for infants and toddlers impacted by parental SUDs.

Conclusions

Our study delineated several potential implementations considerations for the integration of an evidence-based parenting intervention designed specifically for parents with SUDs, MIO, within the home visiting setting. Interestingly, several of the barriers identified may be successfully addressed by the MIO framework itself, thereby suggesting the advantage of adopting it more broadly. Overall, MIO was seen as a potentially valuable approach to facilitate the work home visitors are already doing with families impacted by SUDs, encourage greater engagement in home visiting services, and equip providers with tools that address the unique needs of this population. The home visiting setting was also seen as an ideal setting for the provision of MIO given its flexibility and built-in organizational structure. Despite the barriers to its implementation, providers expressed eagerness to develop new skills for helping parents with SUDs to improve the emotional quality of the parent-child relationship and facilitate positive developmental outcomes for their young children.

Key Findings.

Parent engagement, provider training, and sustainability were the implementation domains identified as having the greatest impact on integration of an evidence-based parenting intervention for parents with substance use disorder into existing home visiting services.

Home visiting services have the potential to address logistical barriers to accessing support services for families affected by substance use disorders.

Integrated relationship-based treatment has the potential to address the emotional barriers to accessing home visiting services among families affected by substance use disorders.

Statement of Relevance.

Families affected by substance use disorder often do not benefit fully from home visiting programs for a variety of reasons. Integrating targeted, relationship-based parenting interventions may make home visiting programs more beneficial to families; however, barriers and facilitators to integration are not well understood. In this study, we identify the implementation domains and themes that are most important to consider when integrating relationship-based interventions for families affected by substance use disorder into home visiting programs.

Acknowledgements:

The study presented in this manuscript honors of the legacy of Dr. Nancy Suchman, cherished mentor, and distinguished clinician scientist. Through this work, we carry forward her vision of thoughtfully bringing “Mothering from the Inside Out” to communities in need. We also thank our community partners who made this study possible, including the Hampden County Perinatal Collaborative.

Funding statement:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health KL2 TR002545, K23DA050731 and T32 DA019426. The views presented in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies Dr. Byatt has received salary and/or funding support from Massachusetts Department of Mental Health via the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms (MCPAP for Moms). She is also the statewide Medical Director of MCPAP for Moms and the Executive Director of Lifeline for Families. She has served on the Medscape Steering Committee on Clinical Advances in Postpartum Depression. She received honoraria from Global Learning Collaborative, Medscape, and Mathematica. She has also served as a consultant for The Kinetix Group. Dr. Lowell receives financial support to provide training and supervision concerning the delivery of Mothering from the Inside Out in clinical and research settings. The remaining authors have no financial interests to report.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest statement: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing and data availability statement:

Research data are not available to be shared.

References

- Aarons GA, Green AE, Palinkas LA, Self-Brown S, Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR, Silovsky JF, Hecht DB, & Chaffin MJ (2012). Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention. Implement Sci, 7, 32. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Green AE, Palinkas LA, Self-Brown S, Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR, Silovsky JF, Hecht DB, & Chaffin MJ (2012). Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention. Implementation Science, 7(1), 1–9. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JG, Fonagy P, & Bateman AW (2008). Mentalizing in clinical practice (1st ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews NC, Motz M, Pepler DJ, Jeong JJ, & Khoury J (2018). Engaging mothers with substance use issues and their children in early intervention: Understanding use of service and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 83, 10–20. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banwell E, Humphrey N, & Qualter P (2021). Delivering and implementing child and adolescent mental health training for mental health and allied professionals: A systematic review and qualitative meta-aggregation. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 1–23. 10.1186/s12909-021-02530-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Gibbons C, & Guo S (2006). Substance abuse treatment and the recurrence of maltreatment among caregivers with children living at home: A propensity score analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(2), 93–104. 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith AM, & Burke SA (2015). Identification of early developmental deficits in infants with prenatal heroin, methadone, and other opioid exposure. Clinical Pediatrics, 54(4), 328–335. 10.1177/0009922814549545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Shanahan M, & Appleyard Carmody K (2014). Promoting supportive parenting in new mothers with substance‐use problems: A pilot randomized trial of residential treatment plus an attachment‐based parenting program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(1), 81–85. 10.1002/imhj.21427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis R (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder MB, Dunst CJ, & Mogro-Wilson C (2011). Confidence and competence appraisals of early intervention and preschool special education practitioners. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 3(1), 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder MB, Dunst CJ, Wilson C, & Stayton V (2013). Predictors of confidence and competence among early childhood interventionists. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 34(3), 249–267. 10.1080/10901027.2013.816806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Gainey RR, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, & Johnson NO (1999). An experimental intervention with families of substance abusers: One‐year follow‐up of the Focus on Families project. Addiction, 94(2), 241–254. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9422418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, & Ryan JP (2007). Co-occurring problems for substance abusing mothers in child welfare: Matching services to improve family reunification. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(11), 1395–1410. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conners NA, Grant A, Crone CC, & Whiteside-Mansell L (2006). Substance abuse treatment for mothers: Treatment outcomes and the impact of length of stay. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31(4), 447–456. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore MM, & Doris JM (1998). Preventing child placement in substance-abusing families: Research-informed practice. Child Welfare, 77(4), 407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, & Deal AG (2011). Effects of in‐service training on early intervention practitioners’ use of family‐systems intervention practices in the USA. Professional Development in Education, 37(2), 181–196. 10.1080/19415257.2010.527779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmin JT (2001). Unresolved feelings of guilt and shame in the maternal role with substance‐dependent African American women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(1), 47–52. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, & Muir-Cochrane E (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Frank DA, Jacobs RR, Beeghly M, Augustyn M, Bellinger D, Cabral H, & Heeren T (2002). Level of prenatal cocaine exposure and scores on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development: Modifying effects of caregiver, early intervention, and birth weight. Pediatrics, 110(6), 1143–1152. 10.1542/peds.110.6.1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty KP, Skinner M, Fleming CB, Gainey RR, & Catalano RF (2008). Long‐term effects of the Focus on Families project on substance use disorders among children of parents in methadone treatment. Addiction, 103(12), 2008–2016. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02360.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ES, McAllister JM, & Wexelblatt SL (2019). Developmental disorders and medical complications among infants with subclinical intrauterine opioid exposures. Population Health Management, 22(1), 19–24. 10.1089/pop.2018.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans SL, & Jeremy RJ (2001). Postneonatal mental and motor development of infants exposed in utero to opioid drugs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(3), 300–315. 10.1002/imhj.1003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KE, Duryea ER, Painter M, Vanderploeg JJ, & Saul DH (2019). Family‐Based Recovery: An innovative collaboration between community mental health agencies and child protective services to treat families impacted by parental substance use. Child Abuse Review, 28(1), 69–81. 10.1002/car.2545 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup MA, Humphreys JC, Brindis CD, & Lee KA (2003). Extrinsic barriers to substance abuse treatment among pregnant drug dependent women. Journal of Drug Issues, 33(2), 285–304. 10.1177/002204260303300202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Wolicki S, Barfield WD, Patrick SW, Broussard CS, Yonkers KA, Naimon R, & Iskander J (2017). CDC Grand Rounds: Public health strategies to prevent neonatal abstinence syndrome. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(9), 242. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6609a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk E, & Banga PS (2011). Engagement of substance-using pregnant women in addiction recovery. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 30(1), 79–91. 10.7870/cjcmh-2011-0006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL (1998). Selective prevention interventions: The Strengthening Families Program. In Drug abuse prevention through family interventions (Vol. 177, pp. 160–207). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Ghosh Ippen C, & Van Horn P (2006). Child-Parent Psychotherapy: 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(8), 913–918. 10.1097/01.chi.0000222784.03735.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty LP, Becker M, Dresner N, Meltzer-Brody S, Gopalan P, Glance J, Victor GS, Mittal L, Marshalek P, & Lander L (2016). Guidelines for the management of pregnant women with substance use disorders. Psychosomatics, 57(2), 115–130. 10.1016/j.psym.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely J, Kumar PC, Rieckmann T, Sedlander E, Farkas S, Chollak C, Kannry JL, Vega A, Waite EA, & Peccoralo LA (2018). Barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of substance use screening in primary care clinics: A qualitative study of patients, providers, and staff. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 13(1), 8. 10.1186/s13722-018-0110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niccols A, Milligan K, Sword W, Thabane L, Henderson J, & Smith A (2012). Integrated programs for mothers with substance abuse issues: A systematic review of studies reporting on parenting outcomes. Harm Reduction Journal, 9(1), 14. 10.1186/1477-7517-9-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajulo M, Pyykkönen N, Kalland M, Sinkkonen J, Helenius H, & Punamäki R-L (2011). Substance abusing mothers in residential treatment with their babies: Postnatal psychiatric symptomatology and its association with mother–child relationship and later need for child protection actions. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 65(1), 65–73. 10.3109/08039488.2010.494310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajulo M, Pyykkönen N, Kalland M, Sinkkonen J, Helenius H, Punamäki RL, & Suchman N (2012). Substance‐abusing mothers in residential treatment with their babies: Importance of pre‐and postnatal maternal reflective functioning. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33(1), 70–81. 10.1002/imhj.20342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajulo M, Suchman N, Kalland M, & Mayes L (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of residential treatment for substance abusing pregnant and parenting women: Focus on maternal reflective functioning and mother‐child relationship. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(5), 448–465. 10.1002/imhj.20100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock-Chambers E, Buckley D, Lowell A, Clark MC, Suchman N, Friedmann P, Byatt N, & Feinberg E (2022). Relationship-based home visiting services for families affected by substance use disorders: A qualitative study. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 10.1007/s10826-022-02313-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock-Chambers E, Feinberg E, Senn-McNally M, Clark MC, Jurkowski B, Suchman N, Byatt N, & Friedmann PD (2020). Engagement in early intervention services among mothers in recovery from opioid use disorders. Pediatrics, 145(2). 10.1542/peds.2019-1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock-Chambers E, Leyenaar JK, Foss S, Feinberg E, Wilson D, Friedmann PD, Visintainer P, & Singh R (2019). Early intervention referral and enrollment among infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 40(6), 441–450. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, Glass JE, & York JL (2012). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical care research and review, 69(2), 123–157. 10.1177/1077558711430690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, & Hensley M (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo qualitative data analysis software. In (Version 12)

- Ruff CC, Alexander IM, & McKie C (2005). The use of focus group methodology in health disparities research. Nurs Outlook, 53(3), 134–140. 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]