Abstract

The majority of pediatric central nervous system (CNS) tumors are located in eloquent anatomical areas making surgical resection and, in some cases, even biopsy risky or impossible. This diagnostic predicament coupled with the move towards molecular classification for diagnosis has exposed an urgent need to develop a minimally-invasive means to obtain diagnostic information. In non-CNS solid tumors, the detection of circulating tumor DNA in plasma and other bodily fluids has been incorporated into routine practice and clinical trial design for selection of molecular targeted therapy and longitudinal monitoring. For primary CNS tumors, however, detection of ctDNA in plasma has been challenging. This is likely related at least in part to anatomical factors such as the blood brain barrier. Due to the proximity of primary CNS tumors to the CSF space, our group and others have turned to CSF as a rich alternative source of ctDNA. While multiple studies at this time have demonstrated the feasibility of CSF ctDNA detection across multiple types of pediatric CNS tumors, the optimal role and utility of CSF ctDNA in the clinical setting has not been established. In this review we discuss the work-to-date on CSF ctDNA liquid biopsy in pediatric CNS tumors and the associated technical challenges and review the promising opportunities that lie ahead for integration of CSF ctDNA liquid biopsy into clinical care and clinical trial design.

Introduction:

Pathological classification of pediatric central nervous system (CNS) tumors increasingly relies on molecular biomarkers to define distinct clinical entities and standardize diagnoses, as reflected in the 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System.1

Obtaining diagnostic tissue generally requires invasive neurosurgical procedures, and tumor sampling in certain anatomical locations such as the optic pathway or medulla may entail significant risks to the patient. Furthermore, repeat sampling to monitor treatment response is rarely feasible. As such, there is a need to develop alternative, minimally-invasive means to obtain accurate diagnostic information at the time of initial diagnosis and/or for longitudinal monitoring. Tumors shed small fragments of tumor DNA (i.e. circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)) into bodily fluids2–5. While in non-CNS solid tumors, assessment of ctDNA is increasingly being incorporated into clinical trials6–10, and for some disease types such as non-small-cell lung cancer has begun to enter routine clinical practice11, detection of ctDNA in plasma of primary CNS tumor patients has been challenging2, 12, 13 and likely due to unique anatomical factors, such as the blood-brain barrier, as well as the low-grade biology of many entities resulting in a slow tumor cell turnover. Our group and others have shown that using CSF for liquid biopsy for primary CNS tumor patients is superior to using plasma due to increased amounts of ctDNA in the CSF with low background noise from the acellular microenvironment, leading to higher rates of ctDNA detection12–14. These feasibility studies have set the stage for future clinical implementation of CSF ctDNA liquid biopsy for molecular diagnosis, longitudinal monitoring/assessment of treatment response and prognostication in primary CNS tumor patients.

What is cell-free DNA?

Cell-free DNA is composed of fragments of DNA that are released from various tissues in the body after cell-death. In individuals without underlying malignancies, this DNA derives predominantly from apoptotic hematopoietic cells15, and is typically composed of fragments that are approximately 167 base pairs16. In cancer patients the amount of circulating ctDNA is increased. The proportion of ctDNA that is derived from the tumor tissue is specifically called circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and is composed of shorter fragments (145 base pairs)17, 18. The process of ctDNA fragmentation leading to the formation of characteristic signatures based on the tissue of origin is determined by nucleosomal organization, gene expression, chromatin structure and the nuclease content in the tissue of origin19, 20. It has now been extensively demonstrated that these fragments of ctDNA can be found throughout bodily fluids of patients with underlying malignancies such as plasma, saliva, sputum, stool, urine, and CSF (in primary CNS tumor patients)21–24.

Historical experience with ctDNA in patients with primary CNS tumors

It is well established that in patients with primary and secondary CNS tumors, the yield of plasma ctDNA is much lower than that of non-CNS malignancies2, 12, 13, 25 and detectable only in a small subset of patients with widely disseminated disease. As an alternative to plasma, CSF has emerged as a rich source of ctDNA in primary CNS tumor patients, which can be used for downstream targeted or genome-wide sequencing4, 5, 12, 14, 25–27. Several studies across the adult and pediatric populations have now established the feasibility of CSF ctDNA for use in tumor diagnosis, molecular classification, and response monitoring (Table 1)4, 5, 12–14, 26, 28–32. Furthermore, CSF ctDNA detection has been associated with tumor proximity to the CSF space, tumor burden, active disease, and leptomeningeal spread of disease12, 28, 33. In this review, we will focus on the studies to date performed on CSF ctDNA in patients with pediatric CNS tumors and the clinical scenarios in which different approaches may be the most beneficial.

Table 1.

Selected Studies using CSF ctDNA for Liquid Biopsy in Primary Brain Tumors

| Number of Patients | Tumor Type | Sequencing Methods | Sequencing Targets | Major Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. 2021 | 123 | Medulloblastoma | sWGS, | N/A | Association of ctDNA and DNA CNV in CSF with treatment response and risk of tumor recurrence |

| Miller et al. 2019 | 85 | Glioma | NGS | MSK-IMPACT (341/410/468 gene panels) | Detection of CSF ctDNA in 42/85 (49.4%) patients and associated with disease burden and adverse outcome |

| Miller et al. 2022 | 64 | Pediatric/AYA primary brain tumors | NGS | MSK-IMPACT (468 gene panel) | Detection of CSF ctDNA in 30/64 patients (46.8%), with clinical impact on diagnosis, molecular classification, treatment selection and/or response monitoring to therapy |

| Pan et al. 2019 | 57 | Primary brainstem tumors | NGS | Panel of 68 glioma-associated genes | Detection of ≥1 somatic mutation in CSF ctDNA in 6/9 (67%) samples |

| Pentsova et al. 2016 | 53 | Primary brain tumors and CNS metastases | NGS | MSK-IMPACT (341 gene panel) | Detection of CSF ctDNA in 20/32 (63%) CNS metastases and 6/12 (50%) PBTs |

| Panditharatna et al. 2018 | 48 | Pediatric HGG and DMG | ddPCR | H3 K27M mutation | Detection of H3 K27M in CSF and plasma in 88% of DMGs, and H3 K27M ctDNA in CSF of 20/23 (87%) H3 K27M mutant tumors |

| Wang et al. 2015 | 35 | Primary brain tumors and CNS metastases | ddPCR, WES | Tumor guided | Detection of CSF ctDNA in 26/35 (74%) patients |

| Fujioka et al. 2021 | 34 | Diffuse glioma | ddPCR | IDH1, TERT promoter, H3 K27M mutations | Detection of diagnostic mutations in intracranial CSF in 20/34 (71%) compared to detection in 28/34 (82%) in tumor samples |

| Izquierdo et al. 2021 | 32 | Pediatric HGG and DMG | ddPCR | Tumor guided | Detection of ≥1 somatic mutation in CSF ctDNA in 6/9 (67%) samples |

| Cantor et al. 2022 | 24 | DMG | ddPCR, | H3 K27M mutation | Changes in VAF of H3 K27M are associated with treatment response and recurrence |

| Martinez-Ricarte et al. 2018 | 20 | Glioma | ddPCR, NGS | Targeted glioma panel | Detection of CSF ctDNA in 17/20 (85%) |

| Mouliere et al. 2018 | 13 | Glioma | sWGS | N/A | Detection of CSF somatic copy number alterations in 5/13 (38.4%) patients |

| Escuerdo et al.2020 | 13 | Medulloblastoma | ddPCR | Tumor guided | Detection of CSF ctDNA in 10/13 (76.9%) patients |

| De Mattos-Arruda et al. 2015 | 12 | Primary brain tumors and CNS metastases | ddPCR, NGS | Tumor guided MSK-IMPACT (341 gene panel) | Detection of CSF ctDNA in 12/12 (100%) cases, MAF was associated with disease burden and treatment response |

| Huang et al. 2017 | 11 | Pediatric brain tumors | ddPCR | H3 mutations | Test sensitivity of 87.5% and specificity of 100%, detection of H3 K27M in CSF of 4/6 (66.7%) DMGs |

| Pan et al. 2015 | 7 | Primary brain tumors and CNS metastases | ddPCR, Targeted Amplicon | Tumor guided | Detection of diagnostic mutations in CSF in 6/7 (86%) patients |

AYA, adolescent and young adult; CNV, copy number variation; ddPCR, digital droplet PCR; DMG, diffuse midline glioma; H3, histone H3; HGG, high grade glioma; MAF, mutant allele fraction; NGS, next generation sequencing; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; sWGS, shallow whole genome sequencing; WES, whole exome sequencing;.

Diagnostic utility and challenges

Several groups have shown the feasibility and utility of using CSF ctDNA for molecular diagnosis of diffuse midline glioma (DMG), including diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), capitalizing on the high prevalence of the recurrent hotspot mutation K27M in histone H3. Huang et al. used Sanger sequencing of H3F3A and HIST1H3B or nested PCR with mutation specific primers to detect CSF ctDNA34. Sufficient CSF ctDNA was isolated from 5/6 patients, and H3K27M was detected in 4/6 (66.7%). In another patient, H3.3G34V was detected34. Subsequently, other groups showed increased sensitivity and estimation of the variant allele frequency (VAF) employing digital droplet PCR (ddPCR)35–37. In a large study, Panditharatna et al. used ddPCR on CSF from 28 patients with DMGs, they were able to detect H3K27M in 75% of samples collected at diagnosis, 67% collected during treatment, and 90% collected postmortem25. Furthermore, they demonstrated that while the H3K27M hotspot could also be detected via ddPCR in plasma, the VAF was much higher in CSF likely due to the lower amount of non-tumor DNA25. They were also able to demonstrate that in serial plasma samples from children with diffuse midline glioma, VAF of H3K27M tracked with radiographic and subsequent clinical progression25.

Pan et al. performed deep sequencing on CSF ctDNA obtained from patients with brainstem gliomas using a panel of 68 glioma-associated genes38. Most samples were obtained intra-operatively prior to surgical manipulation of the tumors (52/57). They were able to detect a tumor-specific mutation in over 82.5% of CSF ctDNA samples (47/57). Of these, the majority had pathognomonic, disease defining alterations in H3F3A (53.2%) or IDH1 (8.5%). Common secondary driver mutations were also detectable with high frequency, such as TP53 (48.9%), ATRX (11.7%), PIK3CA (10.6%), and PDGFRA (10.6%)38.

We were able to detect a BRAF-KIAA1549 alteration in three out of four patients with diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumor who had a prior non-diagnostic biopsy due to low tumor content,33 not only leading to a diagnosis, but also revealing a therapeutically actionable driver alteration. All three patients were subsequently started on MEK inhibitor therapy with favorable clinical responses.

Disease-response monitoring

Optimal clinical care requires accurate, reproducible assessments to track response to therapy, and MRI continues to be the mainstay for patients with CNS tumors. However, imaging changes may lag behind clinical progression and can be difficult to assess. In one study, there was a significant amount of variability when four readers measured 50 post-radiation MRI scans with T2-weighted, post-contrast T1-weighted, and FLAIR sequences from DIPG patients39.

Another clinical problem is distinguishing true tumor progression from pseudoprogression following treatment of gliomas with radiation and/or immunotherapy. Pseudoprogression refers to transient imaging findings that are consistent with tumor progression but reflect an immune stimulatory/inflammatory response that subsequently improves without additional treatment. Distinguishing true progression from pseudoprogression is critical both for patients treated on clinical trials and according to standard-of-care, as it strongly influences clinical decision-making and the uncertainty leads to significant emotional distress for patients. Our group showed that in adult glioma patients the detection of CSF ctDNA was associated with shorter survival, i.e. patients with positive ctDNA lived for an average of 3.82 months vs. 11.97 months for the patients in whom CSF ctDNA could not be detected12. These findings support the notion that the likelihood of CSF ctDNA detection is higher in patients with active disease.

CSF ctDNA can also be used for longitudinal monitoring of disease response and recurrence. Liu et al. showed the significant potential for CSF ctDNA in disease monitoring of medulloblastoma patients26. Analyzing longitudinally collected CSF samples from medulloblastoma patients enrolled on a clinical trial, they demonstrated that shallow whole genome sequencing (sWGS) of CSF ctDNA was highly associated with disease burden, treatment response and tumor recurrence26. Furthermore, diagnostically informative DNA copy number profiles could be generated from the sequencing data. ctDNA detection rates were highest in samples from patients with metastatic disease, and detection of CSF ctDNA predated imaging progression by at least 3 months in over 60% of relapsing patients26. A positive sample at the end of therapy was significantly associated with inferior progression-free survival (PFS), suggesting that CSF ctDNA sequencing may help guide therapeutic decision making in the future. Similarly, Escudero et al. employed whole exome DNA sequencing along with customized ddPCRs on CSF ctDNA for medulloblastoma subgrouping, detection of minimal residual disease, and tracking of tumor evolution40. Cantor et al. integrated serial CSF and plasma ctDNA collection into a multi-site Phase 1 trial with imipridone (ONC201) for children with DMGs14, using ddPCR for H3K27M on CSF and plasma, comparing changes in VAF with imaging findings. They were able to show that the change in VAF was associated with prolonged PFS and that spikes in VAF preceded imaging progression in approximately 50% of patients14. These studies have paved the way for real-time integration of serial CSF ctDNA analysis into future clinical trials.

Implementation of CSF ctDNA sequencing in clinical care

Our group published the first study to describe real-time implementation of CSF ctDNA testing and reporting in the clinical realm33. We used MSK-IMPACT™, a next-gen sequencing panel that captures all protein-coding exons of 468 cancer-associated genes and select introns (now updated to include 505 genes). This assay is compliant with clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA), approved by the New York State Department of Health and authorized by the FDA for clinical use. In this study, we reported on 64 CSF samples from 45 pediatric, adolescent, and young adult (AYA) patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent primary CNS tumors across 12 histopathological subtypes. We were able to detect somatic alterations in 30/64 samples (46.9%) and at least one sample per individual patient in 21/45 patients33. We identified three areas in which CSF ctDNA provided additional clinical information:1) for diagnosis and/or identification of actionable alterations; (2) monitoring response to therapy; and (3) tracking tumor evolution. Overall, we found that 33% of patients derived a clinical benefit from CSF ctDNA analysis.

Use of CSF ctDNA to deepen our understanding of the clonal evolution of pediatric primary CNS tumors

Genome-wide sequencing of CSF ctDNA throughout the disease course offers the opportunity to unravel molecular mechanisms underlying the diffuse infiltrative growth, tumor dissemination and leptomeningeal spread that predominate in pediatric CNS tumor subtypes including high-risk medulloblastoma. Wu et al. have shown that molecular alterations in medulloblastoma metastases can be tracked back to rare subclonal events in the primary tumor41. Work by our group has demonstrated that newly acquired oncogenic alterations that were undetectable in the primary tumor can be detected in CSF ctDNA, including in PDGFRA in an IDH wild-type adult glioma patient and PIK3CA in a DMG patient,12, 33 representing potentially clinically actionable mutations with molecular targeted therapy. Furthermore, we found that as the interval between tumor and CSF collection increased, there was increased heterogeneity especially within the growth factor signaling pathways12. Typically, the discordance was within the same genes or related pathways consistent with a pattern of convergent evolution12. The non-invasiveness of CSF ctDNA sequencing offers the opportunity to obtain multiple samples throughout the course of disease, unraveling the patterns of clonal evolution that underlie tumor progression and development of therapeutic resistance in real-time, ultimately leading to improved clinical decision making and outcomes.

Technical challenges with CSF ctDNA liquid biopsy

To date, the development of ctDNA-based liquid biopsy assays for pediatric primary CNS tumor patients has lagged behind the development of assays for patients with solid tumors due to the comparably low levels of shed ctDNA12,4 (PMID: 29615461)12, 25, 26, 33, especially in localized, non-disseminated, low-grade tumors. This difference may be attributed to low quantities of ctDNA especially early in the disease course or where there is an intact blood brain barrier. Remarkably though, ddPCR analysis for hotspot alterations is feasible with as low as 2.5 pg of genomic DNA as a template as shown by Pandutharatna et al. with ddPCR for H3K27M in diffuse midline glioma patients25. Furthermore, Bruzek et al. demonstrated a 0.1 femtomole DNA limit of hotspot detection using Nanopore sequencing of ultra-short pHGG CSF cf-tDNA fragments in patients with pediatric HGG42. These amounts are much lower than those required for next-gen sequencing though this too can be successful with low DNA input33. In this study by our group we showed that Next-Gen sequencing of CSF ctDNA is possible even with amounts as low as 0.088 ng of total input CSF ctDNA though this was significantly lower that the median concentration of extracted ctDNA that led to detection of somatic alterations which was 1.18 ng/ml (vs. 0.067 for the negative samples)33. CSF ctDNA sampling is possible with such low amounts of ctDNA because of the enriched ratio of tumor-derived ctDNA in the CSF as compared to normal circulating DNA (due to the relatively acellular nature of CSF) creating little background noise. Hence, despite low overall nucleic acid yield, mutations can be captured at high VAF.

Clearly, further efforts to improve the sensitivity of ctDNA testing in CNS tumor patients are needed by optimizing existing assays and developing novel testing platforms. Li et al. reported on whole-genome methylation sequencing of CSF cell-free DNA from medulloblastoma patients to detect tumor subtype, as well as DNA methylation changes in serial samples that were associated with treatment response and tumor recurrence43.

Summary

The discovery of CSF ctDNA in pediatric primary CNS tumor patients, along with the development of increasingly sensitive molecular testing platforms, has not only led to novel insights into tumor biology, but also for the first time allows both clinical researchers as well as clinicians to perform minimally invasive molecular diagnostics in this population.

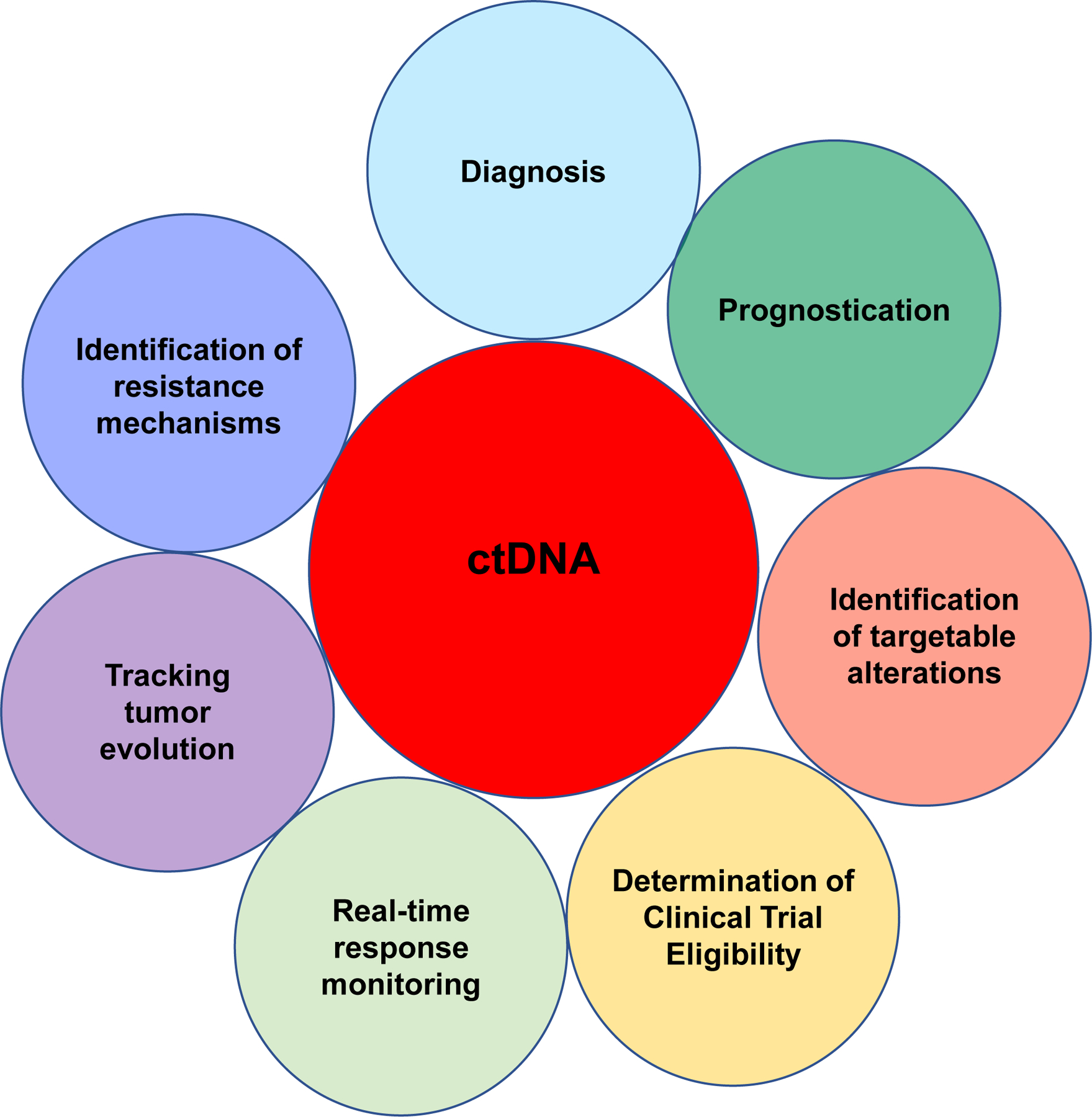

As the testing platforms continue to improve, opportunities for clinical research will continue to increase. At the same time, the proportion of pediatric CNS tumor patients benefitting from this novel, minimally-invasive diagnostic approach in the clinic is likely to increase as well. Tangible benefits for a subset of patients already include improved molecular diagnosis, prognostication, treatment response monitoring, and in some cases, selection of appropriate molecular targeted therapies. Furthermore, CSF ctDNA offers the potential to reveal the genomic changes that underlie tumor progression via serial sequencing to monitor ongoing tumor evolution and identify the emergence of new clones. As the field of CSF liquid biopsy rapidly evolves, its critical to recognize that different assays will likely be needed depending on the scientific or clinical objective (Figure 1). For example, next-generation limited panel-based or PCR-based sequencing approaches with very high sensitivity are best suited for an initial diagnosis and molecular tumor classification, including in instances where biopsy is considered high-risk, whereas broader genome-wide sequencing approaches such as the use of large-panel or genome wide next-generation sequencing assays may be better suited for analyzing the changing clonal landscape of disseminated and metastatic tumors over time.

Figure 1: Clinical and research applications of CSF ctDNA.

Current applications of CSF ctDNA in the clinical setting have primarily focused on diagnostics. As assay sensitivity improves, we anticipate that additional clinical applications will be developed including use of CSF ctDNA for real-time response monitoring during treatment and clinical trials. Furthermore, liquid biopsy technologies will provide us with a better understanding of pediatric brain tumor biology through tracking of clonal evolution.

Besides providing minimally-invasive molecular diagnostics for patients at the time of initial diagnosis or disease recurrence, CSF ctDNA testing also has the potential to allow for minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring and help tailor therapy. An ideal MRD assay would have to have both very high sensitivity and specificity. For this purpose, perhaps assays that utilize an approach to evaluate fragmentation patterns of cell-free DNA across the genome may be the most promising20,44,45. Another option would be a bespoke approach which utilizes a tumor-informed approach based on the development of a patient specific targeted panel developed from the mutations identified through whole exome or whole genome sequencing of the primary tumor46, 47. Either way, much additional research will be needed for careful clinical validation before such assays can be incorporated into standard care.

While the field of pediatric CSF liquid biopsy has been rapidly progressing, to date most of these studies have been retrospective and limited in size. To truly understand the utility of liquid biopsy in the clinical care of pediatric CNS tumor patients, integration of this assay into prospective clinical trials is essential. Building on the work by Cantor et al.14, CSF ctDNA is now being integrated into large consortium-based studies such as those run by the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium (NCT04743661) and Pacific Neuro-Oncology Consortium (NCT04732065, NCT05009992). In a multi-institutional effort, our group is also opening a prospective clinical trial for diffuse midline glioma patients where they will undergo Ommaya placement to facilitate frequent CSF collections for longitudinal monitoring of H3 K27M to evaluate ctDNA dynamics in response to treatment.

Given the rapid technological advances and growing body of clinical research, we anticipate that CSF ctDNA is going to be increasingly integrated into the care of pediatric brain tumor patients within the next decade for the purposes of: (1) diagnosis and molecular characterization for tumors in eloquent areas that are not amenable to biopsy; (2) disease-response monitoring both during standard treatment as well as clinical trials; (3) uncovering molecular mechanisms of resistance to therapy and disease progression (Figure 1). We believe that along with continued progress in identifying more effective and less toxic therapies, liquid biopsy assays including CSF ctDNA testing will help fulfill the promise of improved outcomes for children afflicted with CNS tumors.

Acknowledgement:

This work was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant P30 CA008748. We would like to acknowledge Joseph Olechnowicz for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: AMM has nothing to disclose. MAK received consulting and personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, CereXis, QED Therapeutics and Recursion Pharma.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM, Reifenberger G, Soffietti R, von Deimling A, Ellison DW. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231–51. Epub 2021/06/30. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, Bartlett BR, Wang H, Luber B, Alani RM, Antonarakis ES, Azad NS, Bardelli A, Brem H, Cameron JL, Lee CC, Fecher LA, Gallia GL, Gibbs P, Le D, Giuntoli RL, Goggins M, Hogarty MD, Holdhoff M, Hong SM, Jiao Y, Juhl HH, Kim JJ, Siravegna G, Laheru DA, Lauricella C, Lim M, Lipson EJ, Marie SK, Netto GJ, Oliner KS, Olivi A, Olsson L, Riggins GJ, Sartore-Bianchi A, Schmidt K, Shih l M, Oba-Shinjo SM, Siena S, Theodorescu D, Tie J, Harkins TT, Veronese S, Wang TL, Weingart JD, Wolfgang CL, Wood LD, Xing D, Hruban RH, Wu J, Allen PJ, Schmidt CM, Choti MA, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Diaz LA Jr. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra24. Epub 2014/02/21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J, Wynne JF, Eclov NC, Modlin LA, Liu CL, Neal JW, Wakelee HA, Merritt RE, Shrager JB, Loo BW Jr., Alizadeh AA, Diehn M. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med. 2014;20(5):548–54. Epub 2014/04/08. doi: 10.1038/nm.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Springer S, Zhang M, McMahon KW, Kinde I, Dobbyn L, Ptak J, Brem H, Chaichana K, Gallia GL, Gokaslan ZL, Groves ML, Jallo GI, Lim M, Olivi A, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Rigamonti D, Riggins GJ, Sciubba DM, Weingart JD, Wolinsky JP, Ye X, Oba-Shinjo SM, Marie SK, Holdhoff M, Agrawal N, Diaz LA Jr., Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Bettegowda C. Detection of tumor-derived DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with primary tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(31):9704–9. Epub 2015/07/22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511694112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pentsova EI, Shah RH, Tang J, Boire A, You D, Briggs S, Omuro A, Lin X, Fleisher M, Grommes C, Panageas KS, Meng F, Selcuklu SD, Ogilvie S, Distefano N, Shagabayeva L, Rosenblum M, DeAngelis LM, Viale A, Mellinghoff IK, Berger MF. Evaluating Cancer of the Central Nervous System Through Next-Generation Sequencing of Cerebrospinal Fluid. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2404–15. Epub 2016/05/11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.6487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, Jamal-Hanjani M, Constantin T, Salari R, Le Quesne J, Moore DA, Veeriah S, Rosenthal R, Marafioti T, Kirkizlar E, Watkins TBK, McGranahan N, Ward S, Martinson L, Riley J, Fraioli F, Al Bakir M, Gronroos E, Zambrana F, Endozo R, Bi WL, Fennessy FM, Sponer N, Johnson D, Laycock J, Shafi S, Czyzewska-Khan J, Rowan A, Chambers T, Matthews N, Turajlic S, Hiley C, Lee SM, Forster MD, Ahmad T, Falzon M, Borg E, Lawrence D, Hayward M, Kolvekar S, Panagiotopoulos N, Janes SM, Thakrar R, Ahmed A, Blackhall F, Summers Y, Hafez D, Naik A, Ganguly A, Kareht S, Shah R, Joseph L, Marie Quinn A, Crosbie PA, Naidu B, Middleton G, Langman G, Trotter S, Nicolson M, Remmen H, Kerr K, Chetty M, Gomersall L, Fennell DA, Nakas A, Rathinam S, Anand G, Khan S, Russell P, Ezhil V, Ismail B, Irvin-Sellers M, Prakash V, Lester JF, Kornaszewska M, Attanoos R, Adams H, Davies H, Oukrif D, Akarca AU, Hartley JA, Lowe HL, Lock S, Iles N, Bell H, Ngai Y, Elgar G, Szallasi Z, Schwarz RF, Herrero J, Stewart A, Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Van Loo P, Dive C, Lin CJ, Rabinowitz M, Aerts H, Hackshaw A, Shaw JA, Zimmermann BG, consortium TR, consortium P, Swanton C. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2017;545(7655):446–51. doi: 10.1038/nature22364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathios D, Johansen JS, Cristiano S, Medina JE, Phallen J, Larsen KR, Bruhm DC, Niknafs N, Ferreira L, Adleff V, Chiao JY, Leal A, Noe M, White JR, Arun AS, Hruban C, Annapragada AV, Jensen SO, Orntoft MW, Madsen AH, Carvalho B, de Wit M, Carey J, Dracopoli NC, Maddala T, Fang KC, Hartman AR, Forde PM, Anagnostou V, Brahmer JR, Fijneman RJA, Nielsen HJ, Meijer GA, Andersen CL, Mellemgaard A, Bojesen SE, Scharpf RB, Velculescu VE. Detection and characterization of lung cancer using cell-free DNA fragmentomes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5060. Epub 2021/08/22. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24994-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellmann MD, Nabet BY, Rizvi H, Chaudhuri AA, Wells DK, Dunphy MPS, Chabon JJ, Liu CL, Hui AB, Arbour KC, Luo J, Preeshagul IR, Moding EJ, Almanza D, Bonilla RF, Sauter JL, Choi H, Tenet M, Abu-Akeel M, Plodkowski AJ, Perez Johnston R, Yoo CH, Ko RB, Stehr H, Gojenola L, Wakelee HA, Padda SK, Neal JW, Chaft JE, Kris MG, Rudin CM, Merghoub T, Li BT, Alizadeh AA, Diehn M. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis to Assess Risk of Progression after Long-term Response to PD-(L)1 Blockade in NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(12):2849–58. Epub 2020/02/13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smyth LM, Reichel JB, Tang J, Patel JAA, Meng F, Selcuklu DS, Houck-Loomis B, You D, Samoila A, Schiavon G, Li BT, Razavi P, Piscuoglio S, Reis-Filho JS, Taylor BS, Baselga J, Solit DB, Hyman DM, Berger MF, Chandarlapaty S. Utility of Serial cfDNA NGS for Prospective Genomic Analysis of Patients on a Phase I Basket Study. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5. Epub 2021/07/13. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devarakonda S, Sankararaman S, Herzog BH, Gold KA, Waqar SN, Ward JP, Raymond VM, Lanman RB, Chaudhuri AA, Owonikoko TK, Li BT, Poirier JT, Rudin CM, Govindan R, Morgensztern D. Circulating Tumor DNA Profiling in Small-Cell Lung Cancer Identifies Potentially Targetable Alterations. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(20):6119–26. Epub 2019/07/14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heitzer E, van den Broek D, Denis MG, Hofman P, Hubank M, Mouliere F, Paz-Ares L, Schuuring E, Sultmann H, Vainer G, Verstraaten E, de Visser L, Cortinovis D. Recommendations for a practical implementation of circulating tumor DNA mutation testing in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100399. Epub 20220221. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller AM, Shah RH, Pentsova EI, Pourmaleki M, Briggs S, Distefano N, Zheng Y, Skakodub A, Mehta SA, Campos C, Hsieh WY, Selcuklu SD, Ling L, Meng F, Jing X, Samoila A, Bale TA, Tsui DWY, Grommes C, Viale A, Souweidane MM, Tabar V, Brennan CW, Reiner AS, Rosenblum M, Panageas KS, DeAngelis LM, Young RJ, Berger MF, Mellinghoff IK. Tracking tumour evolution in glioma through liquid biopsies of cerebrospinal fluid. Nature. 2019;565(7741):654–8. Epub 20190123. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Mattos-Arruda L, Mayor R, Ng CKY, Weigelt B, Martinez-Ricarte F, Torrejon D, Oliveira M, Arias A, Raventos C, Tang J, Guerini-Rocco E, Martinez-Saez E, Lois S, Marin O, de la Cruz X, Piscuoglio S, Towers R, Vivancos A, Peg V, Ramon y Cajal S, Carles J, Rodon J, Gonzalez-Cao M, Tabernero J, Felip E, Sahuquillo J, Berger MF, Cortes J, Reis-Filho JS, Seoane J. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8839. Epub 2015/11/12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantor E, Wierzbicki K, Tarapore RS, Ravi K, Thomas C, Cartaxo R, Yadav VN, Ravindran R, Bruzek AK, Wadden J, John V, Babila CM, Cummings JR, Kawakibi AR, Ji S, Ramos J, Paul A, Walling D, Leonard M, Robertson P, Franson A, Mody R, Garton HJL, Venetti S, Odia Y, Kline C, Vitanza NA, Khatua S, Mueller S, Allen JE, Gardner S, Koschmann C. Serial H3K27M cell-free tumor DNA (cf-tDNA) tracking predicts ONC201 treatment response and progression in diffuse midline glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2022. Epub 2022/02/10. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lui YY, Chik KW, Chiu RW, Ho CY, Lam CW, Lo YM. Predominant hematopoietic origin of cell-free DNA in plasma and serum after sex-mismatched bone marrow transplantation. Clin Chem. 2002;48(3):421–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markus H, Chandrananda D, Moore E, Mouliere F, Morris J, Brenton JD, Smith CG, Rosenfeld N. Refined characterization of circulating tumor DNA through biological feature integration. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1928. Epub 20220204. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05606-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leon SA, Shapiro B, Sklaroff DM, Yaros MJ. Free DNA in the serum of cancer patients and the effect of therapy. Cancer Res. 1977;37(3):646–50. Epub 1977/03/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouliere F, Robert B, Arnau Peyrotte E, Del Rio M, Ychou M, Molina F, Gongora C, Thierry AR. High fragmentation characterizes tumour-derived circulating DNA. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e23418. Epub 2011/09/13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder MW, Kircher M, Hill AJ, Daza RM, Shendure J. Cell-free DNA Comprises an In Vivo Nucleosome Footprint that Informs Its Tissues-Of-Origin. Cell. 2016;164(1–2):57–68. Epub 2016/01/16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cristiano S, Leal A, Phallen J, Fiksel J, Adleff V, Bruhm DC, Jensen SØ, Medina JE, Hruban C, White JR, Palsgrove DN, Niknafs N, Anagnostou V, Forde P, Naidoo J, Marrone K, Brahmer J, Woodward BD, Husain H, van Rooijen KL, Ørntoft M-BW, Madsen AH, van de Velde CJH, Verheij M, Cats A, Punt CJA, Vink GR, van Grieken NCT, Koopman M, Fijneman RJA, Johansen JS, Nielsen HJ, Meijer GA, Andersen CL, Scharpf RB, Velculescu VE. Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer. Nature. 2019;570(7761):385–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Z, Wang W, Li M, Liu J, Zhang Y. Cytological-negative pleural effusion can be an alternative liquid biopsy media for detection of EGFR mutation in NSCLC patients. Lung Cancer. 2019;136:23–9. Epub 2019/08/20. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Almeida EF, Abdalla TE, Arrym TP, de Oliveira Delgado P, Wroclawski ML, da Costa Aguiar Alves B, de SGF, Azzalis LA, Alves S, Tobias-Machado M, de Lima Pompeo AC, Fonseca FL. Plasma and urine DNA levels are related to microscopic hematuria in patients with bladder urothelial carcinoma. Clin Biochem. 2016;49(16–17):1274–7. Epub 2016/10/23. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diehl F, Schmidt K, Durkee KH, Moore KJ, Goodman SN, Shuber AP, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Analysis of mutations in DNA isolated from plasma and stool of colorectal cancer patients. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(2):489–98. Epub 2008/07/08. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura H, Fujiwara Y, Sone T, Kunitoh H, Tamura T, Kasahara K, Nishio K. EGFR mutation status in tumour-derived DNA from pleural effusion fluid is a practical basis for predicting the response to gefitinib. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(10):1390–5. Epub 2006/10/25. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panditharatna E, Kilburn LB, Aboian MS, Kambhampati M, Gordish-Dressman H, Magge SN, Gupta N, Myseros JS, Hwang EI, Kline C, Crawford JR, Warren KE, Cha S, Liang WS, Berens ME, Packer RJ, Resnick AC, Prados M, Mueller S, Nazarian J. Clinically Relevant and Minimally Invasive Tumor Surveillance of Pediatric Diffuse Midline Gliomas Using Patient-Derived Liquid Biopsy. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(23):5850–9. Epub 2018/10/17. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu APY, Smith KS, Kumar R, Paul L, Bihannic L, Lin T, Maass KK, Pajtler KW, Chintagumpala M, Su JM, Bouffet E, Fisher MJ, Gururangan S, Cohn R, Hassall T, Hansford JR, Klimo P Jr., Boop FA, Stewart CF, Harreld JH, Merchant TE, Tatevossian RG, Neale G, Lear M, Klco JM, Orr BA, Ellison DW, Gilbertson RJ, Onar-Thomas A, Gajjar A, Robinson GW, Northcott PA. Serial assessment of measurable residual disease in medulloblastoma liquid biopsies. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(11):1519–30 e4. Epub 2021/10/23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Mattos-Arruda L, Mayor R, Ng CK, Weigelt B, Martinez-Ricarte F, Torrejon D, Oliveira M, Arias A, Raventos C, Tang J, Guerini-Rocco E, Martinez-Saez E, Lois S, Marin O, de la Cruz X, Piscuoglio S, Towers R, Vivancos A, Peg V, Cajal SR, Carles J, Rodon J, Gonzalez-Cao M, Tabernero J, Felip E, Sahuquillo J, Berger MF, Cortes J, Reis-Filho JS, Seoane J. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8839. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Springer S, Mulvey CL, Silliman N, Schaefer J, Sausen M, James N, Rettig EM, Guo T, Pickering CR, Bishop JA, Chung CH, Califano JA, Eisele DW, Fakhry C, Gourin CG, Ha PK, Kang H, Kiess A, Koch WM, Myers JN, Quon H, Richmon JD, Sidransky D, Tufano RP, Westra WH, Bettegowda C, Diaz LA Jr., Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Agrawal N. Detection of somatic mutations and HPV in the saliva and plasma of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(293):293ra104. Epub 2015/06/26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa8507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan W, Gu W, Nagpal S, Gephart MH, Quake SR. Brain tumor mutations detected in cerebral spinal fluid. Clin Chem. 2015;61(3):514–22. Epub 2015/01/22. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.235457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Izquierdo E, Proszek P, Pericoli G, Temelso S, Clarke M, Carvalho DM, Mackay A, Marshall LV, Carceller F, Hargrave D, Lannering B, Pavelka Z, Bailey S, Entz-Werle N, Grill J, Vassal G, Rodriguez D, Morgan PS, Jaspan T, Mastronuzzi A, Vinci M, Hubank M, Jones C. Droplet digital PCR-based detection of circulating tumor DNA from pediatric high grade and diffuse midline glioma patients. Neurooncol Adv. 2021;3(1):vdab013. Epub 2021/06/26. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdab013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujioka Y, Hata N, Akagi Y, Kuga D, Hatae R, Sangatsuda Y, Michiwaki Y, Amemiya T, Takigawa K, Funakoshi Y, Sako A, Iwaki T, Iihara K, Mizoguchi M. Molecular diagnosis of diffuse glioma using a chip-based digital PCR system to analyze IDH, TERT, and H3 mutations in the cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurooncol. 2021;152(1):47–54. Epub 2021/01/09. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03682-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mouliere F, Mair R, Chandrananda D, Marass F, Smith CG, Su J, Morris J, Watts C, Brindle KM, Rosenfeld N. Detection of cell-free DNA fragmentation and copy number alterations in cerebrospinal fluid from glioma patients. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10(12). Epub 2018/11/08. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller AM, Szalontay L, Bouvier N, Hill K, Ahmad H, Rafailov J, Lee AJ, Rodriguez-Sanchez MI, Yildirim O, Patel A, Bale TA, Benhamida JK, Benayed R, Arcila ME, Donzelli M, Dunkel IJ, Gilheeney SW, Khakoo Y, Kramer K, Sait SF, Greenfield JP, Souweidane MM, Haque S, Mauguen A, Berger MF, Mellinghoff IK, Karajannis MA. Next-generation Sequencing of Cerebrospinal Fluid for Clinical Molecular Diagnostics in Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Brain Tumor Patients. Neuro Oncol. 2022. Epub 2022/02/12. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang TY, Piunti A, Lulla RR, Qi J, Horbinski CM, Tomita T, James CD, Shilatifard A, Saratsis AM. Detection of Histone H3 mutations in cerebrospinal fluid-derived tumor DNA from children with diffuse midline glioma. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Ricarte F, Mayor R, Martinez-Saez E, Rubio-Perez C, Pineda E, Cordero E, Cicuendez M, Poca MA, Lopez-Bigas N, Ramon YCS, Vieito M, Carles J, Tabernero J, Vivancos A, Gallego S, Graus F, Sahuquillo J, Seoane J. Molecular Diagnosis of Diffuse Gliomas through Sequencing of Cell-Free Circulating Tumor DNA from Cerebrospinal Fluid. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(12):2812–9. Epub 2018/04/05. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stallard S, Savelieff MG, Wierzbicki K, Mullan B, Miklja Z, Bruzek A, Garcia T, Siada R, Anderson B, Singer BH, Hashizume R, Carcaboso AM, McMurray KQ, Heth J, Muraszko K, Robertson PL, Mody R, Venneti S, Garton H, Koschmann C. CSF H3F3A K27M circulating tumor DNA copy number quantifies tumor growth and in vitro treatment response. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6(1):80. Epub 2018/08/17. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0580-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li D, Bonner ER, Wierzbicki K, Panditharatna E, Huang T, Lulla R, Mueller S, Koschmann C, Nazarian J, Saratsis AM. Standardization of the liquid biopsy for pediatric diffuse midline glioma using ddPCR. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5098. Epub 2021/03/05. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84513-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan C, Diplas BH, Chen X, Wu Y, Xiao X, Jiang L, Geng Y, Xu C, Sun Y, Zhang P, Wu W, Wang Y, Wu Z, Zhang J, Jiao Y, Yan H, Zhang L. Molecular profiling of tumors of the brainstem by sequencing of CSF-derived circulating tumor DNA. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137(2):297–306. Epub 2018/11/22. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1936-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayward RM, Patronas N, Baker EH, Vezina G, Albert PS, Warren KE. Inter-observer variability in the measurement of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2008;90(1):57–61. Epub 2008/07/01. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9631-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Escudero L, Llort A, Arias A, Diaz-Navarro A, Martinez-Ricarte F, Rubio-Perez C, Mayor R, Caratu G, Martinez-Saez E, Vazquez-Mendez E, Lesende-Rodriguez I, Hladun R, Gros L, Ramon YCS, Poca MA, Puente XS, Sahuquillo J, Gallego S, Seoane J. Circulating tumour DNA from the cerebrospinal fluid allows the characterisation and monitoring of medulloblastoma. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5376. Epub 2020/10/29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19175-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X, Northcott PA, Dubuc A, Dupuy AJ, Shih DJ, Witt H, Croul S, Bouffet E, Fults DW, Eberhart CG, Garzia L, Van Meter T, Zagzag D, Jabado N, Schwartzentruber J, Majewski J, Scheetz TE, Pfister SM, Korshunov A, Li XN, Scherer SW, Cho YJ, Akagi K, MacDonald TJ, Koster J, McCabe MG, Sarver AL, Collins VP, Weiss WA, Largaespada DA, Collier LS, Taylor MD. Clonal selection drives genetic divergence of metastatic medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;482(7386):529–33. Epub 20120215. doi: 10.1038/nature10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruzek AK, Ravi K, Muruganand A, Wadden J, Babila CM, Cantor E, Tunkle L, Wierzbicki K, Stallard S, Dickson RP, Wolfe I, Mody R, Schwartz J, Franson A, Robertson PL, Muraszko KM, Maher CO, Garton HJL, Qin T, Koschmann C. Electronic DNA Analysis of CSF Cell-free Tumor DNA to Quantify Multi-gene Molecular Response in Pediatric High-grade Glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(23):6266–76. Epub 20201021. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J, Zhao S, Lee M, Yin Y, Li J, Zhou Y, Ballester LY, Esquenazi Y, Dashwood RH, Davies PJA, Parsons DW, Li XN, Huang Y, Sun D. Reliable tumor detection by whole-genome methylation sequencing of cell-free DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of pediatric medulloblastoma. Sci Adv. 2020;6(42). Epub 2020/10/18. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cristiano S, Leal A, Phallen J, Fiksel J, Adleff V, Bruhm DC, Jensen SO, Medina JE, Hruban C, White JR, Palsgrove DN, Niknafs N, Anagnostou V, Forde P, Naidoo J, Marrone K, Brahmer J, Woodward BD, Husain H, van Rooijen KL, Orntoft MW, Madsen AH, van de Velde CJH, Verheij M, Cats A, Punt CJA, Vink GR, van Grieken NCT, Koopman M, Fijneman RJA, Johansen JS, Nielsen HJ, Meijer GA, Andersen CL, Scharpf RB, Velculescu VE. Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer. Nature. 2019;570(7761):385–9. Epub 2019/05/31. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peneder P, Stutz AM, Surdez D, Krumbholz M, Semper S, Chicard M, Sheffield NC, Pierron G, Lapouble E, Totzl M, Erguner B, Barreca D, Rendeiro AF, Agaimy A, Boztug H, Engstler G, Dworzak M, Bernkopf M, Taschner-Mandl S, Ambros IM, Myklebost O, Marec-Berard P, Burchill SA, Brennan B, Strauss SJ, Whelan J, Schleiermacher G, Schaefer C, Dirksen U, Hutter C, Boye K, Ambros PF, Delattre O, Metzler M, Bock C, Tomazou EM. Multimodal analysis of cell-free DNA whole-genome sequencing for pediatric cancers with low mutational burden. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3230. Epub 2021/05/30. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23445-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zviran A, Schulman RC, Shah M, Hill STK, Deochand S, Khamnei CC, Maloney D, Patel K, Liao W, Widman AJ, Wong P, Callahan MK, Ha G, Reed S, Rotem D, Frederick D, Sharova T, Miao B, Kim T, Gydush G, Rhoades J, Huang KY, Omans ND, Bolan PO, Lipsky AH, Ang C, Malbari M, Spinelli CF, Kazancioglu S, Runnels AM, Fennessey S, Stolte C, Gaiti F, Inghirami GG, Adalsteinsson V, Houck-Loomis B, Ishii J, Wolchok JD, Boland G, Robine N, Altorki NK, Landau DA. Genome-wide cell-free DNA mutational integration enables ultra-sensitive cancer monitoring. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1114–24. Epub 2020/06/03. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0915-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Isaksson S, George AM, Jonsson M, Cirenajwis H, Jonsson P, Bendahl PO, Brunnstrom H, Staaf J, Saal LH, Planck M. Pre-operative plasma cell-free circulating tumor DNA and serum protein tumor markers as predictors of lung adenocarcinoma recurrence. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(8):1079–86. Epub 2019/06/25. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1610573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]