Abstract

Background.

Maternal sleep-disordered breathing is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes and considered deleterious to the developing fetus. Maternal obesity potentiates sleep-disordered breathing which, in turn, may contribute to the influence of maternal obesity on adverse fetal outcomes. However, few empirical studies have evaluated the contemporaneous effects of maternal sleep-disordered breathing events on fetal well-being. These events include apnea and/or hypopnea with accompanying desaturations in oxyhemoglobin.

Objectives.

This report is aimed at reconciling contradictory findings regarding associations between maternal apnea/hypopnea events and clinical indicators of fetal compromise. It also seeks to broaden the knowledge base by examining fetal heart rate and variability before, during, and after episodes of maternal apnea/hypopnea. To accomplish this, we employed overnight polysomnography, the gold standard for ascertaining maternal sleep-disordered breathing and synchronized it with continuous fetal electrocardiography (fECG).

Study Design.

Eighty-four pregnant women with obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥30kg/m2] participated in laboratory-based polysomnography with digitized fECG recording during or near the 36th week of gestation. Sleep was recorded, on average, for 7 hours. Decelerations in fetal heart rate were identified. Fetal heart rate and variability were quantified before, during and following each apnea/hypopnea event. Event-level intensity [desaturation magnitude, duration, and nadir oxygen saturation (SpO2) level] and person-level characteristics based on the full overnight recording [Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), mean SpO2, and SpO2 variability] were analyzed as potential moderators using linear mixed effects models.

Results.

A total of 2,936 sleep-disordered breathing events were identified, distributed across all but 2 participants. On average, participants exhibited 8.7 episodes of apnea/hypopnea per hour (M desaturation duration = 19.1 seconds, M SpO2 nadir = 86.6% per episode); nearly half (n = 39) met criteria for obstructive sleep apnea. Only 45 of 2936 apnea/hypopnea events were followed by decelerations (1.5%). Conversely, most (333 or 88%) of the 378 observed decelerations, including prolonged ones, did not follow an apnea/hypopnea event. Maternal sleep-disordered breathing burden, BMI, and fetal sex were unrelated to the number of decelerations. Fetal heart rate variability increased during periods of maternal apnea/hypopnea but returned to initial levels soon thereafter. There was a dose-response association between the size of the increase in fetal heart rate variability and maternal AHI, event duration, and desaturation depth. Longer desaturations generated less rebound in variability following the event. Mean fetal heart rate did not change during episodes of maternal apnea/hypopnea.

Conclusions.

Episodes of maternal sleep apnea/hypopnea did not evoke decelerations in fetal heart rate, despite the predisposing risk factors that accompany maternal obesity. The significance of the modest transitory increase in fetal heart rate variability in response to apnea/hypopnea episodes is not clear but may reflect compensatory, delimited autonomic responses to momentarily adverse conditions. This study found no evidence that episodes of maternal sleep-disordered breathing pose immediate jeopardy, as reflected in fetal heart rate responses, to the near-term fetus.

Keywords: pregnancy, sleep, polysomnography, fetal assessment, heart rate variability, decelerations, obesity, sleep apnea, fetal electrocardiogram, Monica AN24

Condensation.

Episodes of maternal apnea/hypopnea during sleep transiently increase fetal heart rate variability but do not result in fetal heart rate decelerations.

Introduction

Pregnancy amplifies disordered sleep. In particular, sleep-disordered breathing, characterized by recurrent episodes of complete (apnea) or partial (hypopnea) airway obstruction and oxyhemoglobin desaturation, is implicated in a host of adverse outcomes, including gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, preterm delivery and stillbirth.1–4 Maternal obesity, a significant risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing, also poses well-identified and overlapping threats making it difficult to isolate independent contributions of either.5 In contrast to the robust research literature on these and related maternal outcomes, there is limited evidence on whether episodes of apnea/hypopnea have direct, contemporaneous effects on fetal well-being. Such associations could indicate physiological mediators for outcomes linked to both sleep-disordered breathing and maternal obesity and may pose distinct, persistent threats to fetal development.

Patterns in antepartum heart rate are the most conspicuous and accessible indicators of fetal well-being. Concerns regarding a precipitating role of maternal apnea/hypopnea on fetal hypoxia were raised in several case reports.6–8 Systematic studies since then rely on clinical indicators of fetal compromise and have yielded contradictory results. These range from failure to detect any deceleratory episodes and/or loss in variability following sleep-disordered breathing events9 to linking the majority of observed fetal heart rate decelerations to such events.10 Each of these reports includes approximately 20 women. In 29 growth-restricted fetuses, 20% of fetal heart rate decelerations and/or loss in variability were reported to have had a respiratory event in the 5 preceding minutes,11 but those associations did not persist when analyses compared control periods of comparable duration.12

Study objective.

This study describes the proximal effects of maternal sleep-disordered breathing on fetal heart rate. It seeks to reconcile the contradictory findings regarding decelerations as a particular example of a fetal response while broadening scope to include the potential influence of sleep-disordered breathing on continuous measurement of fetal heart rate and variability. Unlike prior studies, all instances of maternal apnea/hypopnea were identified throughout the night using polysomnography, the gold standard for identifying sleep-disordered breathing, and fetal heart rate was measured throughout. To maximize the incidence of sleep-disordered breathing and restrict confounding, enrollment was limited to pregnant women with obesity, yielding a large number of events for analysis. We hypothesized that fetal responsiveness to apnea/hypopnea would be potentiated in women exhibiting more frequent and intense episodes due to repeated exposure to oxyhemoglobin desaturation.

Materials and methods

Participants

Non-smoking, obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) women ≥18 years of age, carrying singleton fetuses without conditions jeopardizing pregnancy or normal development, and without diagnosed sleep disorders, were recruited. Among 131 enrolled participants, 107 completed polysomnography; the remainder delivered prior to assessment (n = 7, 5.3%), developed exclusionary complications (n = 7, 5.3%), or declined (n = 10, 7.6%). Technical challenges in collecting continuous fetal data resulted in 22 (20.5%) recordings with high levels of missing data. These values are consistent with those detailed elsewhere.13,14 These cases, and one with total sleep time < 1 hour, were excluded. This report is based on the remaining 84 maternal-fetal dyads.

Select participant demographic and relevant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Twelve women (14%) had gestational or adult-onset diabetes and 15 (18%) had gestational or pre-existing hypertension; most (63; 75%) had neither, 3 were comorbid. As expected, participants had an array of treated and untreated clinical conditions but no single condition or medication was prevalent enough to allow inclusion as a covariate. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (NA_00093511). Women provided written consent.

Table 1.

Select maternal and infant characteristics (n = 84)

| Measure | M (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal | |

| Gestational week at recording | 36.2 (.8) |

| Weight (lbs) at recording | 247.1 (41.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) at recording | 41.6 (6.1) |

| Age (years) | 26.9 (6.3) |

| Education | |

| Some high school | 13 (15%) |

| High school graduation | 40 (48%) |

| Some college | 25 (30%) |

| Bachelor or masters degree | 6 (7%) |

| Self-identified race/ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 76 (91%) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 6 (7%) |

| Multiple race/Hispanic | 2 (2%) |

| Primiparous | 36 (43%) |

| Infant* | |

| Gestational age delivery (weeks) | 39.3 (1.1) |

| Birth weight (g) | 3285.3 (468.7) |

| 5-minute Apgar score | 8.8 (0.7) |

| Weight for gestational age | |

| Appropriate (AGA) | 78 (92.9%) |

| Small (SGA) | 2 (2.4%) |

| Large (LGA) | 3 (3.6%) |

| Caesarean section delivery | 36 (43%) |

| Female sex | 42 (50%) |

Infant data unavailable for one case due to delivery outside of study hospital.

Procedure

Polysomnography

Overnight in-laboratory polysomnography relied on standard techniques and scored using American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines.15 Data were recorded via RemLogic 1.3 N7000 data acquisition system (Natus Medical, Broomfield, CO) and included electroencephalograms, electrooculograms, submental and tibialis electromyograms, modified V5 electrocardiogram, finger pulse oximetry and respiratory inductance plethysmography. Airflow was monitored using a nasal pressure cannula and oronasal thermistor. Apneas were defined as a complete cessation of airflow lasting ≥10 seconds and hypopneas as a ≥30% decrease in airflow lasting ≥10 seconds in association with oxygen desaturation of ≥ 3% or an arousal. Onset and offset of each apnea/hypopnea event were established and the desaturation magnitude, desaturation duration, and associated nadir oxygen saturation (SpO2) of each was quantified. Data collection commenced upon lights out; maternal sleep staging and time spent in supine (i.e., on back) sleep were scored.

Fetal monitoring

The fetal electrocardiogram (fECG) was derived from electrodes placed on the maternal abdominal wall and digitized simultaneously with maternal polysomnography using a Monica AN24 device (Monica Healthcare, Nottingham, UK), which detects and extracts the fECG from the maternal signal. This wireless device is about the size of a cellphone and uses customized software for data collection (VS version 2.71a) and analysis (DK version 2.1). Signal detection is based on five disposable electrode patches arrayed on the maternal abdominal wall in a standard configuration. The AN24 is the most widely adopted commercially available fECG device and has been validated against intrapartum monitoring with scalp electrodes13,16 and with antepartum cardiotocography.14 R-wave intervals were timed and output sampled at 0.5 Hz to generate continuous fetal heart rate values. Periods of fECG signal loss shorter than 16 contiguous seconds were treated with interpolation; longer segments were excluded from analysis. Detail about the data compilation and error rejection process is available elsewhere.17 Figure 1 provides an example of the compiled data used in this report from one participant, sampled early and late in the overnight recording.

Figure 1. Sample data.

Sample data from an individual participant collected near the beginning (23: 00) and end (04:00) of polysomnography; each plot represents approximately 1 hour. Continuous fetal (upper line) and maternal (lower line) heart rate data are superimposed over maternal sleep staging denoted by background color (see key); vertical blue lines reflect transient arousals. Apnea/hypopnea events are designated by yellow bars; onset and offset of desaturations are in orange. Periods of sleep-disordered breathing are observable during each hour, both occur during REM sleep. Prolonged decelerations such as the one near 04:00 were uncommon.

Decelerations were digitally quantified and defined as declines in fetal heart rate ≥15 bpm below baseline for ≥15 seconds. A subset of prolonged decelerations of ≥ 2 minutes in length was identified to allow comparison with the most frequently linked type of deceleration reported elsewhere.10 Decelerations were considered linked to a sleep-disordered breathing event if they began during an apnea/hypopnea or an accompanying desaturation, or within 1 minute after desaturation offset. Decelerations that were embedded in multiple events were attributed once. All episodes identified as a deceleration were visually reviewed to ensure they were not a function of signal artifact.

Fetal heart rate values were epoched and averaged during the 10-second period immediately preceding each event, during each event, and during the 10-second period following event conclusion; mean values (FHR) for each period were calculated. The standard deviation of fetal heart rate was computed for each epoch, yielding a measure of variability (FHRV_SD). The 10-second before/after interval was required to avoid interference with offset/onset of proximal apneas/hypopneas. Note that because the fECG device outputs averaged beat to beat intervals over 2 seconds for synchronization with polysomnography data, the variability metric was neither frequency nor time domain based.

Characterization of sleep-disordered breathing severity

Two sets of sleep-disordered breathing variables were derived. The first characterizes the intensity of each event and includes desaturation magnitude, desaturation duration, and SpO2 nadir (event-level measures). The second summarizes each woman’s overall burden of sleep-disordered breathing and includes the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI; number of apneas plus hypopneas/hour of sleep), mean SpO2, and lability (SD) in SpO2 (person-level measures).

Statistical analyses

Analysis of enumerated decelerations was primarily descriptive; Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to evaluate associations with person-level measures and covariates. Unadjusted FHR and FHRV_SD values were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance with 3 levels for time (i.e., before, during and after each event). Subsequently, these were followed by linear mixed effect models to assess the contribution of the event-level and person-level measures to FHR and FHRV_SD changes between each period (i.e., pre-event to during event; during event to post-event; pre-event to post-event) in which change was detected. Maternal BMI, age, and time spent in supine sleep were included as general covariates in the mixed effect models based on well-described existing evidence regarding factors that affect sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy. Analyses used R, v 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Maternal sleep onset began, on average, at 22:27 (SD = 68 minutes). Data collection continued to approximately 06:00 when participants either awakened spontaneously or the recording was terminated [M sleep time for recording, 7 hours, 11 minutes (SD = 50 minutes)]. On average, women spent 107 minutes (SD = 115 minutes) sleeping in the supine position. A total of 2,936 maternal apnea/hypopnea events with fetal heart rate data of analyzable quality were identified. Apart from 2 participants, all expressed at least one qualifying event. Nearly half (46.4%, n = 39) met the diagnostic threshold for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA; AHI ≥ 5/hour) with most of those (82%, n = 32) classified as mild (AHI 5 to <15/hour). However, 687 (24.7%) events were attributed to two participants with severe OSA. Maternal weight at the time of polysomnography ranged from 166 to 417 lbs (M = 247); corresponding BMIs ranged from 32 to 64 kg/m2 (M = 61.6). As expected, women with higher BMI expressed significantly higher levels of sleep disordered breathing (r (82) = .51, p < .001), lower levels of SpO2 (r (82) = −.23, p < .05) and greater SpO2 labilty (r (82) = .52, p < .001).

Fetal response to maternal SDB events

Decelerations

A total of 378 decelerations during overnight recordings were identified; most (90%) participants displayed at least one (M = 4.5, SD = 2.9, range 0 to 13). The number of decelerations was not higher in fetuses of women with higher BMI (r (82) = .04), or in those who spent more time in supine sleep (r (82) = −.09). Overall maternal burden of sleep-disordered breathing, including maternal AHI, mean SpO2 and lability in SpO2 during the entire night, was also not related to the number of fetal decelerations (rs range from .05 to .13).

A total of 45 (11.9%) decelerations followed an apnea/hypopnea event. An additional 52 (13.8%) followed a maternal arousal or brief period of wakefulness after sleep onset (see example, Figure 1). Put another way, only 1.5% (45/2936) of sleep-disordered breathing events were accompanied by a deceleration. Twelve prolonged (i.e., ≥ 2 minutes) decelerations were identified. Of these, one followed an apnea/hypopnea event, one preceded an event, and 4 followed or preceded a period of arousal or wakefulness; the remainder occurred during uninterrupted periods of sleep. Decelerations occurred most often during maternal non-REM sleep (50.5%), followed by periods of waking or while settling into sleep (41.5%). However, although only 8% of decelerations occurred during REM sleep, nearly half (46.7%) of the 45 decelerations linked to maternal sleep-disordered breathing occurred during REM sleep. Fetal sex was not a significant factor in either the number of decelerations or whether they were linked to sleep-disordered breathing events.

Fetal heart rate and variability

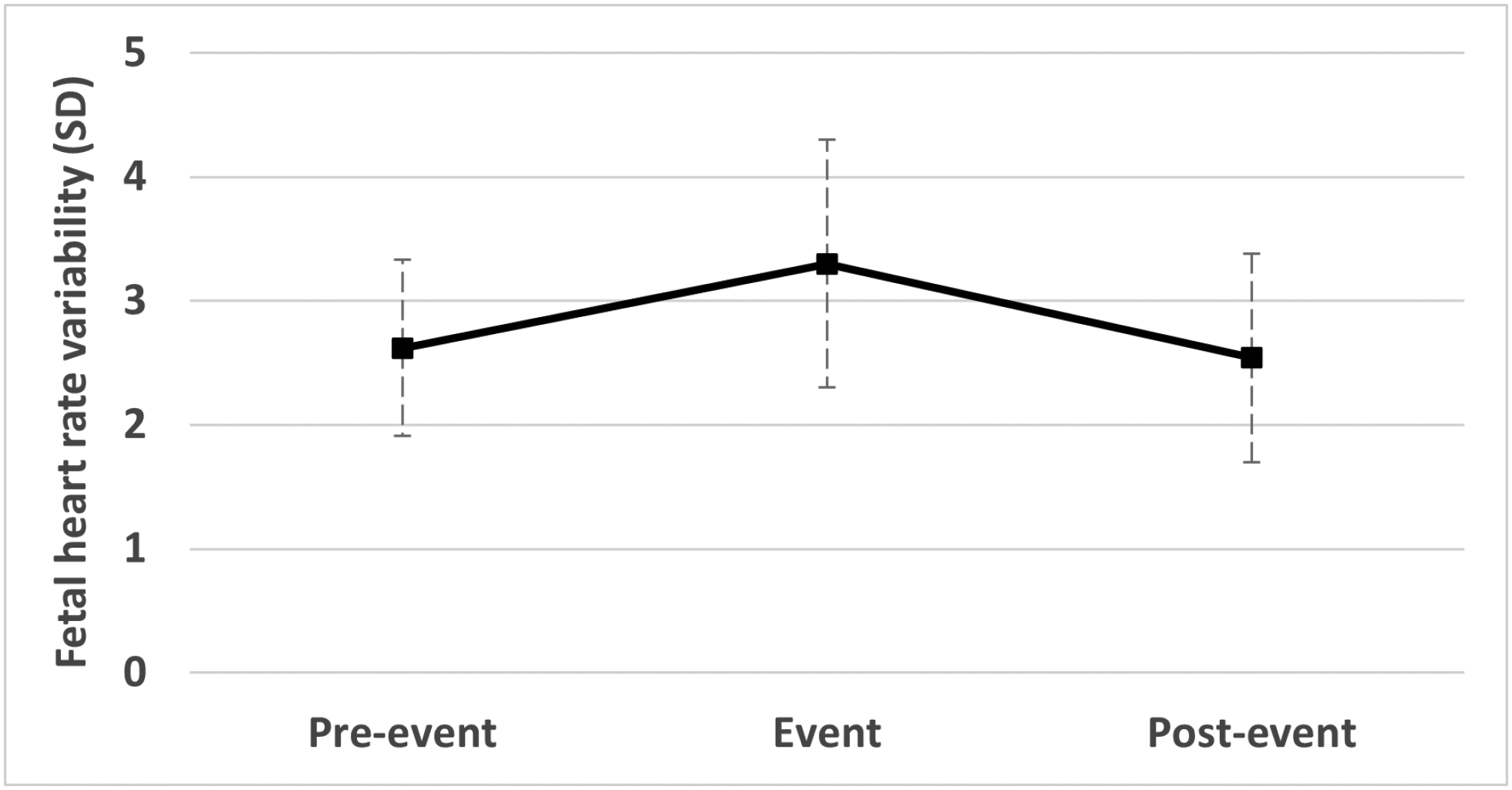

Mean FHR and FHRV_SD values measured before, during and following sleep-disordered breathing events are presented in Figure 2. As evident from Figure 2a, FHR was unaffected by episodes of apnea/hypopnea. This was confirmed by a non-significant unadjusted repeated measures analysis of variance result (F (2, 160) = 0.82). In contrast, Figure 2b shows a significant increase in FHRV_SD (β = 0.7999, t = 12.21, p < .0001) followed by a significant decrease after the desaturation ended (β −0.852, t = 12.45, p < .0001). FHRV_SD was no different in the 10 seconds after events than immediately preceding them (β = −0.0436, t = −1.04, p = .299), indicating a return to initial levels.

Figure 2. Mean fetal responses.

Mean fetal responses to sleep-disordered breathing (i.e., apnea/hypopnea) events; error bars reflect standard deviation. Figure 2a reveals lack of mean fetal heart rate (FHR) response to events; Figure 2b depicts an increase in fetal heart rate variability (FHRV_SD) during maternal apnea/hypopnea events, followed by a return to pre-event levels within 10 seconds. The response was modest in magnitude but statistically significant. FHRV_SD responses were greater when maternal sleep-disordered breathing was more frequent, and desaturations were longer and deeper.

The next set of analyses were multivariate and controlled for maternal age, BMI and supine positioning. The goal of these was to evaluate whether maternal and event characteristics modified the observed changes. FHRV_SD increased more when maternal desaturations were longer (β = 0.018, t = 4.34, p < .0001) and reached a lower SpO2 nadir (β = −0.004, t = −1.99, p < .05). Fetuses of women with higher AHI exhibited greater increase in FHRV_SD to events (β = 0.0097, t = 2.26, p < .05). Similarly, the longer the desaturation, the less FHRV_SD returned to pre-event levels (β = −.0197, t = −4.77, p < .0001).. FHR or FHRV_SD responses did not differ based on whether participants met the clinical threshold for diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (46.4%, n = 39) or by fetal sex.

Consideration of outlier influence on results

As noted, two participants with severe obstructive sleep apnea (i.e., AHIs of 55.4 and 91.9 events/hour) contributed a disproportionate number of events. Observed decelerations were below average in one (2) and above average in another (10). To examine whether these outliers exerted undue influence on results of continuous measures, the same models for FHR and FHRV_SD were rerun without these two participants. Statistical significance was unchanged.

Comment

a. Principal Findings.

Using fetal heart rate decelerations as an indicator of fetal compromise, we found no evidence that episodes of maternal apnea/hypopnea place the fetus in immediate jeopardy. Only 1.5% of sleep-disordered breathing events were followed by decelerations. This is roughly the same percentage as associated with transient maternal waking. Although 12% of decelerations followed a sleep-disordered breathing event, some of these may be the result of chance, particularly in participants with many events. Decelerations were not more common in fetuses of women with higher overnight levels of apnea/hypopnea or lower or more labile oxyhemoglobin levels, suggesting that accumulating levels of exposure do not further destabilize the fetus over the course of a night.

The second set of findings involves the continuously measured variables surrounding and during maternal sleep-disordered breathing events. Mean fetal heart rate did not change to maternal apnea/hypopnea, ruling out bradycardia as a response. Fetal heart rate variability increased during desaturations but decreased soon afterwards to initial levels. There was a dose-response association between increases in fetal heart rate variability and overall maternal sleep-disordered breathing burden (i.e., AHI), event duration, and desaturation depth. Fetal heart rate variability was less likely to return to initial levels within the allotted time following longer desaturations.

b. Results in context.

Our inability to detect an association between fetal decelerations and maternal sleep-disordered breathing confirms findings from some studies9,12 but not others.10,11 At least one other study also reported no association between the overall burden of maternal sleep-disordered breathing and the number of observed fetal decelerations.11 Considering variation in populations, gestational ages, methods and monitoring techniques, there is no obvious explanation for the prior inconsistencies which may simply be the result of the vagaries of small samples. The current study has taken a more comprehensive approach by quantifying episodic and continuous fetal heart rate responses to all instances of maternal apnea/hypopnea.

c. Clinical implications.

In this journal in the early 1980’s, Patrick and colleagues reported extended periods of very low fetal heart rate in recordings of healthy term fetuses, observing that “Fortunately, most low FHR measurements are made overnight between 0200 and 0600 hours, when patients and clinicians are normally asleep” (p. 538)18 In the current study, fetuses displayed, on average, between 4 and 5 decelerations during the night. The incidence of decelerations did not increase with higher maternal BMI or time spent in supine sleep. With the exception of associations with maternal waking, it is unclear how many were associated with other commonly identified sources, including uterine motility, changes in maternal position, and/or fetal motor activity,12 that were not measured in this study. However, we have ascertained that they are infrequently linked to apnea/hypopnea events. Thus, periods of sleep-disordered breathing do not appear to cause worrisome fetal heart rate responses, a finding that may be reassuring to women and their providers concerned about implications for fetal well-being.

The implications of the observed transient elevations in fetal heart rate variability during apnea/hypopnea episodes are unknown. The magnitude of these changes was modest, despite statistical significance, corresponding to a change of less than one standard deviation of the variability measure. This is unlikely to be visible by eye and is not representative of the markedly high fetal heart rate variability (i.e., zig zag pattern) that can appear during labor and may be associated with adverse perinatal outcomes.19

d. Research implications.

In addition to providing relevant data on the effects of maternal sleep-disordered breathing on the fetus, this study fits into a broader framework based on long-standing clinical and academic interest in the role of antenatal hypoxia on long term perinatal and infant outcomes. Neurological insults suggestive of hypoxic-ischemic injury often manifest at or following delivery without antepartum or intrapartum antecedents. Documentation of the functional consequences of transient periods of decreased maternal oxygenation on the developing fetus is often necessarily limited to experimental animal preparations. In the numerous studies conducted over decades based on fetal sheep models, effects of induced hypoxia on fetal heart rate variability differ based on design factors including duration, intensity and chronicity.20,21 However, the degree of induced hypoxia in such models often exceeds those relevant to human pregnancy conditions. Experimental clinical studies have, to a far lesser extent, tried to address the issue. An early study, that would not be permissible today, altered maternal oxygenation through both psychological (i.e., fear-inducing stimuli and sham hypoxia) and physiological (i.e., hypoxic and hyperoxic) manipulations to evaluate effects on fetal heart rate.22 More recently, a growing body of research evaluates fetal heart rate and other parameters before and after strenuous maternal aerobic exercise at maximal and submaximal levels of maternal oxygen uptake.23

In contrast, sleep-disordered breathing is a spontaneous physiological phenomenon of variable intensity that can be evaluated in relation to the nature and intensity of the fetal response. Here we found that the frequency of apnea/hypopnea events and the magnitude of desaturations was commensurate with the increase in fetal heart rate variability, signifying a causal relationship. This pattern of response to desaturations may reflect adaptive, regulatory, or compensatory processes of sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation in neurologically intact fetuses with adequate placental function and reserves. Additional work is necessary to understand the implications, if any, of these responses.

This study characterized the extent of sleep-disordered breathing in a sample of pregnant women with obesity. Participants had episodes of apnea/hypopnea, on average, 9 times a night, although the average event duration was only 19 seconds. As noted above, while we did not see evidence of cumulative effects of repetitive exposure during the night, it is possible that chronicity of exposure over many nights may generate a cascade of responses. We have previously reported that fetuses of women in this sample with higher sleep-disordered breathing are more active during the day.24 These fetuses also showed modest reductions in the temporal integration between heart rate and motor activity, an indicator of fetal neurodevelopment. There are a few reports that maternal sleep-disordered breathing interferes with aspects of subsequent child development.25–27 Much remains to be learned about whether there are persistent effects on neurological development manifest in childhood and beyond, and when noted, any effects are adequately distinguished from the confounding factor of obesity through appropriate controls.

e. Strengths and Limitations.

The principal strength of this study is the use of laboratory-based polysomnography to characterize sleep-disordered breathing events in tandem with simultaneous fECG monitoring overnight. This approach, and the relatively large sample for a study of this kind, allowed analysis of a large number of respiratory events. The restriction of participants to women with obesity amplified the number of events available for analysis and results are therefore applicable to those most at risk for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. It is a limitation in the degree to which it may restrict generalizability; however the recent estimates of pre-pregnancy obesity rates in this population neared 40% and are steadily rising.28

The principal limitation of this report is the peril at concluding that sleep-disordered breathing is benign to the developing fetus when our measurement was restricted to patterns of fetal heart rate. Several pathophysiological mechanisms that go beyond the more commonly recognized modifications to oxygenation have been proposed to mediate sleep-disordered breathing and adverse fetal and pregnancy outcomes. These include disruptions to restorative sleep, neuroendocrine systems, inflammatory processes, metabolic demands, and telomere shortening,29–31 none of which is readily measurable on a moment to moment basis within the fetal milieu, but may have persistent influence. An equally important consideration is that the sample, despite the risks conferred by maternal obesity, is comprised of maternal/fetal dyads that had attained near-term gestation without growth restriction or other indication of significant fetal compromise. As described earlier, slightly over 10% of enrolled participants (n = 14) either delivered prior to their scheduled polysomnography or developed exclusionary criteria based on developing pregnancy or fetal concerns. It is unknown whether maternal sleep-disordered breathing would have generated the same results in these fetuses or other populations with inadequate reserves or pathology, or during the remaining weeks leading up to delivery.

f. Conclusions.

Maternal sleep-disordered breathing events do not pose immediate jeopardy to the near-term fetus, despite the predisposing risk factor of maternal obesity. Confidence in the novel findings regarding the influence of apnea/hypopnea episodes on fetal heart rate variability is bolstered by the dose-response nature of the relationship. It is unclear whether these repetitive, transitory perturbations to fetal heart rate variability reflect normal, delimited physiological responses to momentarily adverse situations or if they reveal instability in fetal autonomic regulation.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Sleep-disordered breathing characteristics

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Event-level Intensity measures (n = 2,936) | |

| Desaturation magnitude, SpO2 % change | 3.5 (4.3) |

| Desaturation length (seconds) | 19.1 (12.7) |

| Desaturation nadir, SpO2, % | 86.6 (24.9) |

| Person-level SDB measures (n = 84) | |

| Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), events/hour | 8.7 (13.6) |

| Mean SpO2 level, % | 96.6 (1.2) |

| SpO2 variability, (SD) | 95 (.4) |

At a glance.

A: Why was this study conducted?

Limited information exists on whether episodes of maternal sleep-disordered breathing have contemporaneous, deleterious effects on the fetus.

B: Key findings

Fetal heart rate, the most conspicuous indicator of fetal well-being, was measured continuously during laboratory-based polysomnography, the gold standard for detecting maternal sleep-disordered breathing (i.e., apnea and/or hypopnea), in 84 pregnant women with obesity.

Only 45 (1.5%) of the nearly 3,000 observed episodes of maternal apnea/hypopnea were temporally associated with decelerations in fetal heart rate.

Apnea/hypopnea episodes generated transient increases in fetal heart rate variability.

C: What does this add to what is known?

This study evaluates fetal heart rate responses to all maternal sleep-disordered breathing events over the course of a night and provides the most comprehensive information to date on the topic.

Acknowledgments.

We thank the dedication and generosity of our study families without whom this work would not be possible.

Funding:

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) award R01 HD079411. NIH had no role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Glossary:

- Sleep-disordered breathing

This term describes conditions characterized by abnormal respiratory patterns and abnormal gas exchange during sleep, including obstructive sleep apnea, in which repetitive episodes of partial or complete upper airway collapse occur, leading to sleep disruption and recurrent oxyhemoglobin desaturation events

- Desaturation

A period of reduced blood oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) that often accompanies apnea and hypopnea

- Apnea/hypopnea

Complete (apnea) or partial (hypopnea) cessation of airflow, generally lasting for at least ten seconds and usually associated with a drop in SpO2

- Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI)

A standard measure of the severity of sleep-disordered breathing, based on the frequency of events exhibited per hour of sleep

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest

Conference presentation: Preliminary results were presented by Pien, G. et al, at the 34th Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies, Virtual meeting, June 13 – 17, 2020.

References

- 1.Brown NT, Turner JM, Kumar S. The intrapartum and perinatal risks of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:147–61 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garbazza C, Hackethal S, Riccardi S, et al. Polysomnographic features of pregnancy: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2020;50:101249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu Q, Zhang X, Wang Y, et al. Sleep disturbances during pregnancy and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2021;58:101436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warland J, Dorrian J, Morrison JL, O’Brien LM. Maternal sleep during pregnancy and poor fetal outcomes: A scoping review of the literature with meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2018;41:197–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Souza R, Horyn I, Pavalagantharajah S, Zaffar N, Jacob CE. Maternal body mass index and pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2019;1:100041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joel-Cohen S, Schoenfeld A. Fetal response to periodic sleep apnea: a new syndrome in obstetrics. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1978;8:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roush S, Bell L. Obstructive sleep apnea in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Pract 2004;17:292–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahin F, Koken G, Cosar E, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in pregnancy and fetal outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;100:141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olivarez S, Maheshwari B, McCarthy M, et al. Prospective trial on obstructive sleep apnea in pregnancy and fetal heart rate monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitts DS, Treadwell MC, O’Brien LM. Fetal heart rate decelerations in women with sleep-disordered breathing. Reprod Sci 2021; 28:2602–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skrzypek H, Wilson DL, Fung AM, et al. Fetal heart rate events during sleep, and the impact of sleep disordered breathing, in pregnancies complicated by preterm fetal growth restriction: An exploratory observational case-control study. BJOG 2022. online ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson DL, Fung AM, Skrzypek H, et al. Maternal sleep behaviours preceding fetal heart rate events on cardiotocography. J Physiol 2022;600:1791–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamber KK, Hayes DJL, Carey SJ, Wijekoon JHB, Heazell AEP. A systematic scoping review to identify the design and assess the performance of devices for antenatal continuous fetal monitoring. PLoS One 2020;15:e0242983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiPietro JA, Watson H, Raghunathan RS. Measuring fetal heart rate and variability: Fetal cardiotocography versus electrocardiography. Dev Psychobiol 2022;64:e22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2.0. Darien, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen WR, Ommani S, Hassan S, et al. Accuracy and reliability of fetal heart rate monitoring using maternal abdominal surface electrodes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:1306–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiPietro JA, Raghunathan RS, Wu HT, et al. Fetal heart rate during maternal sleep. Dev Psychobiol 2021;63:945–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick J, Campbell K, Carmichael L, Probert C. Influence of maternal heart rate and gross fetal body movements on the daily pattern of fetal heart rate near term. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982;144:533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarvonen MJ, Lear CA, Andersson S, Gunn AJ, Teramo KA. Increased variability of fetal heart rate during labour: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. BJOG 2022, online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parer JT, Dijkstra HR, Vredebregt PP, Harris JL, Krueger TR, Reuss ML. Increased fetal heart rate variability with acute hypoxia in chronically instrumented sheep. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1980;10:393–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw CJ, Allison BJ, Itani N, et al. Altered autonomic control of heart rate variability in the chronically hypoxic fetus. J Physiol 2018;596:6105–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Copher DE, Huber C. Heart rate response of the human fetus to induced maternal hypoxia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1967;98:320–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monga M Fetal heart rate response to maternal exercise. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2016;59:568–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiPietro JA, Watson H, Raghunathan RS, Henderson JL, Sgambati FP, Pien GW. Fetal neuromaturation in late gestation is affected by maternal sleep disordered breathing and sleep disruption in pregnant women with obesity. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2022;157:181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bin YS, Cistulli PA, Roberts CL, Ford JB. Childhood health and educational outcomes associated with maternal sleep apnea: A population record-linkage study. Sleep 2017;40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tauman R, Zuk L, Uliel-Sibony S, et al. The effect of maternal sleep-disordered breathing on the infant’s neurodevelopment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:656 e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrakotkhiew W, Chirdkiatgumchai V, Tantrakul V, Thampratankul L. Early developmental outcome in children born to mothers with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2021;88:90–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Driscoll AK, Gregory ECW. Prepregnancy body mass index and infant outcomes race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2020. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2021;70:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johns EC, Denison FC, Reynolds RM. Sleep disordered breathing in pregnancy: A review of the pathophysiology of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2020;229:e13458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salihu HM, King L, Patel P, et al. Association between maternal symptoms of sleep disordered breathing and fetal telomere length. Sleep 2015;38:559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson NT, Turner JM, Kumar S. Pathophysiological changes associated with sleep disordered breathing and supine sleep position in pregnancy. Sleep Med Rev 2019;46:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.