Abstract

Objective:

The causes of substance use disorders (SUDs) are largely unknown and the effectiveness of their treatments is limited. One crucial impediment to research and treatment progress surrounds how SUDs are classified and diagnosed. Given the substantial heterogeneity among individuals diagnosed with a given SUD (e.g., alcohol use disorder), identifying novel research and treatment targets and developing new study designs is daunting.

Method:

In this paper, we review and integrate two recently developed frameworks, the NIDA Phenotyping Assessment Battery (NIDA PhAB) and the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), that hope to accelerate progress in understanding the causes and consequences of psychopathology by means of deep phenotyping, or finer-grained analysis of phenotypes.

Results and Conclusions:

NIDA PhAB focuses on addiction-related processes across multiple units of analysis, whereas HiTOP focuses on clinical phenotypes and covers a broader range of psychopathology. We highlight that NIDA PhAB and HiTOP together provide deep and broad characterizations of people diagnosed with SUDs and complement each other in their efforts to address widely known limitations of traditional classification systems and their diagnostic categories. Next, we show how NIDA PhAB and HiTOP can be integrated to facilitate optimal rich phenotyping of addiction-related phenomena. Finally, we argue that such deep phenotyping promises to advance our understanding of the neurobiology of SUD and addiction, which will guide the development of personalized medicine and interventions.

Keywords: Substance use disorders, heterogeneity, psychopathology, mechanism, precision medicine

In 2018, an estimated 11.7% of the US population aged 12 years and older reported using an illicit drug in the past month, with rates rising to almost 24% among individuals aged 18 to 25 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2019). Accordingly, substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses are common, with nearly 4% of the US population meeting diagnostic criteria in the past 12 months and 10% meeting criteria in their lifetime (Grant et al., 2016). At the same time, the effectiveness of existing treatments for SUDs is limited (Bentzley et al., 2021; Volkow, 2020; Witkiewitz et al., 2019). Although some people do recover without formal treatment, large numbers of individuals treated for an SUD drop out of treatment, do not respond to it, or return to harmful use. One crucial impediment to progress in the field is how SUDs are classified and diagnosed. Current nosologies, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and the International Classification of Disease (ICD; World Health Organization, 2004) are associated with a host of limitations, such as within-disorder heterogeneity, poor reliability, and extensive comorbidity (Kotov et al., 2021; Strain, 2021; Volkow, 2020). As a result, traditional diagnostic categories are suboptimal targets for research and treatment.

Two recently developed frameworks, the NIDA Phenotyping Assessment Battery (NIDA PhAB) and the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), were created with three broad goals in mind: (1) to improve upon the limitations of existing diagnostic systems; (2) to accelerate progress in understanding the causes, correlates, and consequences of psychopathology; and (3) to accelerate the pace and efficacy of service delivery/treatment through precision medicine and related approaches. NIDA PhAB and HiTOP have not yet been integrated. The present paper outlines the interface between these two systems and argues that their integration can provide a broad and detailed characterization of people diagnosed with SUDs through deep phenotyping, which may ultimately illuminate treatment targets that maximize treatment effectiveness (Kuhlemeier et al., 2021).

DSM-5/ICD-11 Substance Use Disorders

SUDs encompass a wide variety of characteristics that span neurobiological, cognitive, and social/interpersonal domains. Traditionally, SUDs have been conceptualized as coherent, homogeneous syndromes that are categorical in nature and distinct from other forms of psychopathology (Hasin et al., 2013). Yet, substantial evidence has contradicted these assumptions (see Boness et al., 2021 and Watts et al., 2021, for reviews). In turn, conventional taxonomies (e.g., DSM-5, ICD-11) have attempted to shift away from purely categorical descriptions of SUDs and towards dimensional diagnoses that grade along severity continua. Still, contemporary SUD diagnoses remain plagued by other issues, including that they are characterized by relatively poor reliability and exhibit considerable within-disorder heterogeneity and comorbidity (Kotov et al., 2021; Litten et al., 2015; Strain, 2021).

Furthermore, diagnostic criteria of SUDs have been criticized because they contain a complex blend of core and peripheral (or fundamental and accessory) features. DSM-5 SUDs contain criteria that appear central to addiction or dependence (e.g., tolerance, withdrawal, craving), whereas others reflect sequelae (or downstream consequences) of excess substance use (e.g., social/interpersonal problems, role interference, hazardous use; Martin et al., 2014) that may be overlapping with other psychopathology (e.g., externalizing, personality disorders; McDowell et al., 2019; Watts et al., 2022). For instance, drunk driving is sufficient to qualify for the hazardous use criterion, but it appears to reflect general externalizing liability as opposed to liability specific to alcohol use disorder (Quinn & Harden, 2013). Additionally, some aspects of SUDs reflect dispositional or premorbid characteristics (i.e., impulsivity, reward sensitivity), whereas others reflect acquired neuroadaptations in response to excessive and chronic substance use (e.g., tolerance, withdrawal; Boness et al., 2021).

Given the multifaceted nature of SUDs, there is considerable variability among people diagnosed with a given SUD (e.g., alcohol use disorder) in terms of consumption patterns, symptom presentation, age of onset, profiles of comorbid psychopathology, and treatment outcomes (Litten et al., 2015). At the same time, the specific sources of heterogeneity in SUDs remain largely elusive (Kwako et al., 2016; Litten et al., 2015), although new empirical efforts to identify more homogeneous symptom clusters within SUDs appear promising. For instance, the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) identifies three broad neurofunctional dimensions that are thought to be central to addiction progression: incentive salience, negative emotionality, and executive dysfunction (Kwako et al., 2016). Other research has shown that alcohol use disorder, specifically, can be parsed into separable, genetically distinct dimensions that relate differentially with external criteria: tolerance and excess consumption, withdrawal and continued use, and loss of control (Kendler et al., 2012). Tolerance to tobacco has been similarly dissociated from other aspects of dependence (Perkins, 2002), suggesting that adaptation to excessive and prolonged substance use may be distinct from the rest of the addiction (or dependence) syndrome (Watts et al., 2021, 2022). Nevertheless, multidimensional conceptualizations of SUDs are not yet widely adopted.

In contrast with conventional taxonomies, prevailing modern models of addiction typically acknowledge that SUDs are phenotypically and etiologically heterogeneous and are undergirded by multiple dimensions of liability, as opposed to being unidimensional in nature (Koob & Le Moal, 2001; Kwako et al., 2016; Robinson & Berridge, 2001). These dimensions may be substance-specific (i.e., unique liability for a given SUD), substance-general (i.e., unique liability for SUDs more broadly), externalizing-general (i.e., unique liability for externalizing disorders) or psychopathology-general (i.e., common liability for psychopathology broadly construed). Thus, conceptualizations of each SUD as unitary, as in DSM, likely obscure investigations of neurobiological underpinnings and impede the development of targeted treatment strategies in the pursuit of precision medicine approaches.

Additionally, SUDs are highly comorbid with each other, and with other disorders, including other externalizing disorders (i.e., those characterized by poor behavioral and emotional control), psychotic disorders, and to a lesser extent with internalizing disorders (i.e., those characterized by pronounced negative emotionality; Grant et al., 2016). A major contributing factor to observed comorbidity is that DSM- and ICD-defined disorders draw arbitrary distinctions between various conditions that share features and causes. For instance, the considerable comorbidity among SUDs appears caused by shared genetic mechanisms reflecting tendencies toward addiction proneness (Hatoum et al., 2021). Further, comorbidity between SUDs and other disorders is, at least in part, facilitated by tendencies towards externalizing and internalizing psychopathology broadly construed (Kendler et al., 2011; Krueger et al., 2005; Kushner et al., 2012; Tully & Iacono, 2016). Indeed, SUDs share genetic and neurobiological mechanisms with a variety of externalizing, internalizing, and psychotic disorders (Krueger et al., 2002; Walters et al., 2018).

These and other unresolved issues are best addressed within frameworks that (1) acknowledge that SUDs are dimensional and heterogeneous, and (2) harness their overlapping nature with other forms of psychopathology by delineating shared elements at a fine-grained level. Such frameworks have the potential to refine our ability to construct meaningful symptom profiles within SUDs, detect neurobiological mechanisms responsible for substance use and addiction, and tailor interventions. Given the heterogeneity of SUD, a “one size fits all” approach to research and treatment is not practical (Volkow, 2020).

NIDA PhAB and HiTOP

NIDA PhAB and HiTOP offer particularly promising frameworks for the classification and treatment of SUDs. Although NIDA PhAB and HiTOP were developed separately, they both emerged in response to two shared goals: (1) to overcome limitations of traditional nosologies and (2) to better account for heterogeneity and comorbidity in a data-driven manner. Neither NIDA PhAB nor HiTOP include traditional diagnoses. Instead, they include basic dimensions that describe individual differences in the experience of psychopathology.

Moreover, neither explicitly mentions specific etiological or biological features. Rather, NIDA PhAB and HiTOP expect that data-driven phenotypes are more coherent etiologically as compared to arbitrarily defined diagnostic categories (e.g., Perkins et al., 2020). That is, data-driven phenotypes are expected to map more directly onto etiologic mechanisms, resulting in increased consistency between clinical phenotypes and their biological and psychological processes. In turn, NIDA PhAB and HiTOP provide more optimal targets in neurobiological investigations and treatment of SUDs (Latzman et al., 2020; Ruggero et al., 2019). As a result, NIDA PhAB and HiTOP can better guide care and the application or development of the best treatment for a given person (Keyser-Marcus et al., 2021; Ruggero et al., 2019).

NIDA PhAB.

NIDA PhAB is the latest and most comprehensive extension of the NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) to addiction, extending upon a related addiction-specific project from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the Alcohol and Addictions RDoC (AARDoC). RDoC is a dimensional approach to studying psychopathology that is based on the concept of transdiagnostic neurofunctional domains. Unlike conventional taxonomies (e.g., DSM, ICD), RDoC describes psychopathology in terms of mechanistically meaningful dimensions (e.g., negative valence, positive valence, cognitive, social, arousal & regulation; O’Donnell & Ehlers, 2015; Sanislow et al., 2010). RDoC inspired the conception of (a) the AARDoC and the corresponding assessment battery known as the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA; Kwako et al., 2016) and (b) NIDA PhAB. The ANA and PhAB models share the same goal of classifying individuals by functional domains, rather than traditional means of using signs and symptoms to render diagnoses.

The AARDoC and ANA were derived from Koob and LeMoal’s model of addiction (Koob & Le Moal, 2001), which describes addiction as cyclical and stage-like, whereby its central features are acquired over time. Many people consume high amounts of a substance (binge-intoxication stage) because of its initial pleasurable effects. Over time, substance use is thought to escalate due to increased tolerance. As high amounts of certain substances are consumed, short- and long-term periods of abstinence cause distress and associated aversive physiologic responses due to withdrawal (e.g., elevated heart rate, sweating; withdrawal-negative affect stage). During protracted periods of abstinence, withdrawal intensifies, and one experiences an intense need for the substance (i.e., craving, preoccupation; preoccupation-anticipation stage). Then, as negative affect and craving intensify, their experience is thought to compromise one’s executive functioning, leading to loss of control over abstinence. Thus, one reverts to binge-intoxication. Failure to self-regulate at each stage is thought to result in additional distress, which escalates the progression through the addiction cycle. Therefore, per Koob and LeMoal (2001), addiction arises because of failed self-regulation at each stage of the model.

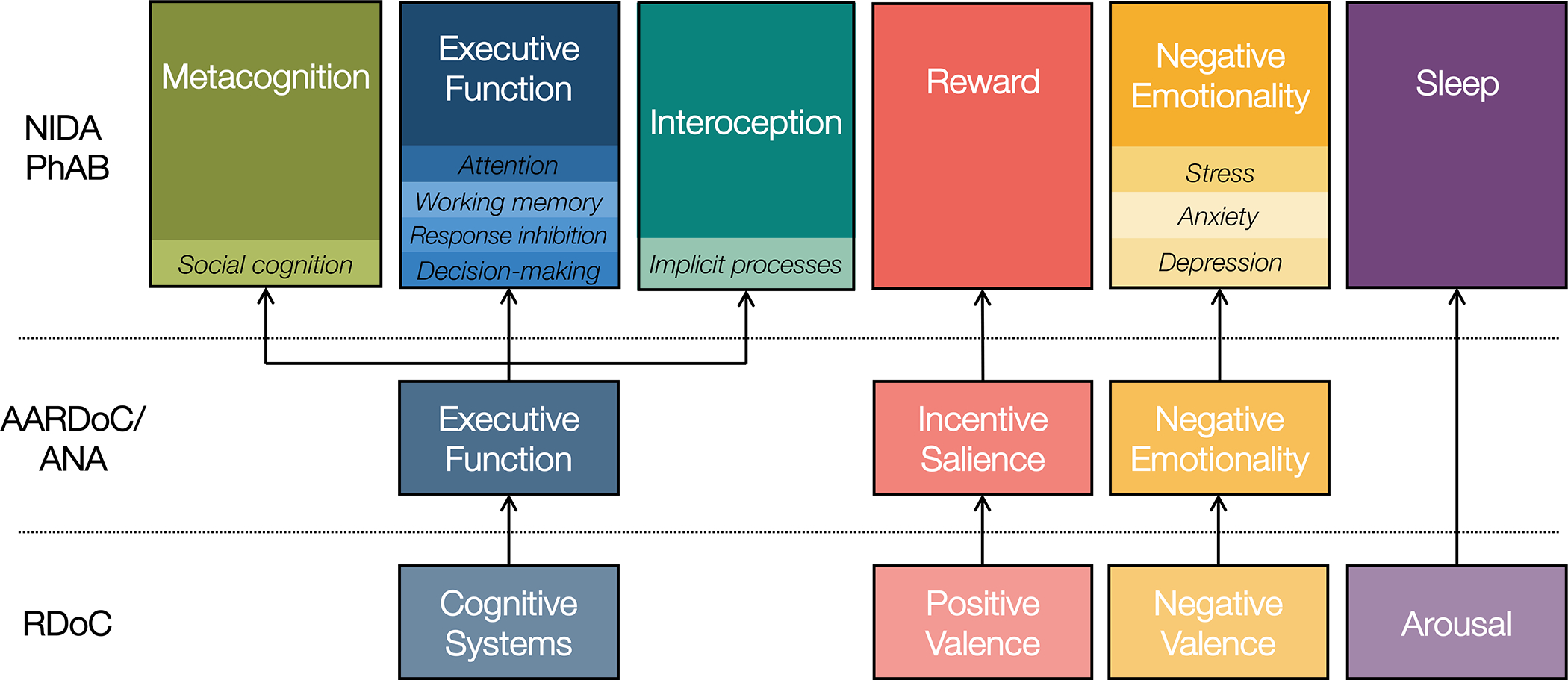

NIAAA’s ANA consists of three neurofunctional domains that map on to Koob and LeMoal’s stages of addiction (see Figure 1): Negative Emotionality (withdrawal-negative affect stage), Incentive Salience (binge-intoxication stage), and Executive Function (preoccupation-anticipation stage; Kwako et al., 2016). The ANA has now been validated in several independent laboratories and in at least two substances, alcohol (Nieto et al., 2021; Stein et al., 2021; Votaw et al., 2020) and methamphetamine (Nieto & Ray, 2022), where the three-domain structure was supported. NIDA PhAB extended ANA to encompass six domains (Figure 1): Reward (Incentive Salience), Negative Emotionality, Sleep, Metacognition, Executive Function, and Interoception (conceptualized as pre-cognition; see Table 1 for all construct definitions). In addition, NIDA PhAB was meant to be usable in any human clinical trial testing a medication. That said, there were strict limits applied in terms of its feasibility, based on time needed for its application during one visit, no more than 2 hours. NIDA PhAB is more likely than ANA to be used in drug development trials given that the ANA battery takes about 10 hours to complete.

Figure 1.

National Institute on Drug Abuse Phenotyping Battery (NIDA PhAB).

Note. This figure illustrates the expansion of 3-domain model of addiction from the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) to the six NIDA Phenotyping Assessment Battery (PhAB) domains, as described in the text. PhAB retained ANA’s Incentive Salience/Reward and Negative Emotionality domains and made several other changes to their model. ANA Cognition was broken into three distinct domains: Interoception, or implicit pre-cognitive processes; Metacognition, or social cognition; and Executive Function, which captures the standard cognitive executive functions (e.g., attention, working memory). Finally, PhAB introduced Sleep to address the role of arousal in neurofunctional responding. © 2022. This work is licensed under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license.

Table 1.

Definitions of NIDA PhAB domains and major HiTOP dimensions.

| NIDA PhAB Domains | |

| Metacognition | Cognitive awareness of one’s own thoughts (i.e., thinking about thinking). |

| Executive Function † | Higher order thought processes, including working memory, flexible thinking, and inhibitory control. |

| Interoception | Awareness and processing of internal bodily states/sensations. |

| Reward † | The incentive salience/motivational drive associated with a given substance. |

| Negative Emotionality † | The tendency to negatively perceive/experience events and circumstances and exhibit a negative emotional response (e.g., anger, hostility, sadness, anxiety). |

| Sleep | Sleep habits/patterns and quality of sleep experienced. |

|

| |

| Major HiTOP Dimensions | |

|

| |

| Internalizing | Experience of negative emotionality. |

| Somatoform | Experience of physical bodily symptoms in the presence of psychological distress. |

| Thought Disorder | Unconventional and creative thinking, as well as perceptions and cognitions that are loosely tethered to reality. |

| Detachment | Reduced volition, sociability, and affective expression. |

| Disinhibited Externalizing | Acting on impulse, without consideration for potential consequences. |

| Antagonistic Externalizing | Navigating interpersonal situations using antipathy and conflict, and to hurt other people intentionally, with little regard for their rights and feelings. |

Note.

= also included in the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment.

NIDA PhAB was constructed using a Delphi method, where experts were asked to select representative and time-efficient measures to ensure that the PhAB is both operational and possible to complete in a single visit. A feasibility study indicated that participants were able to complete the phenotyping portion of the battery in approximately 1.5 hours (Keyser-Marcus et al., 2021). An additional battery was developed as a supplement to the core PhAB battery, which includes a flexible complement of self-report scales assessing an array of factors involved in SUDs that can be used flexibly upon the need of a particular study. Analyses are now underway to validate PhAB’s six-factor model (Keyser-Marcus et al., 2021), and a sociocultural companion to the battery is under development. PhAB is available to researchers and is in the public domain, and all PhAB phenotyping measures are amenable to electronic administration. Because PhAB extends ANA, we focus here on PhAB, though any overlap between HiTOP and PhAB dimensions is thought to extend to ANA.

HiTOP.

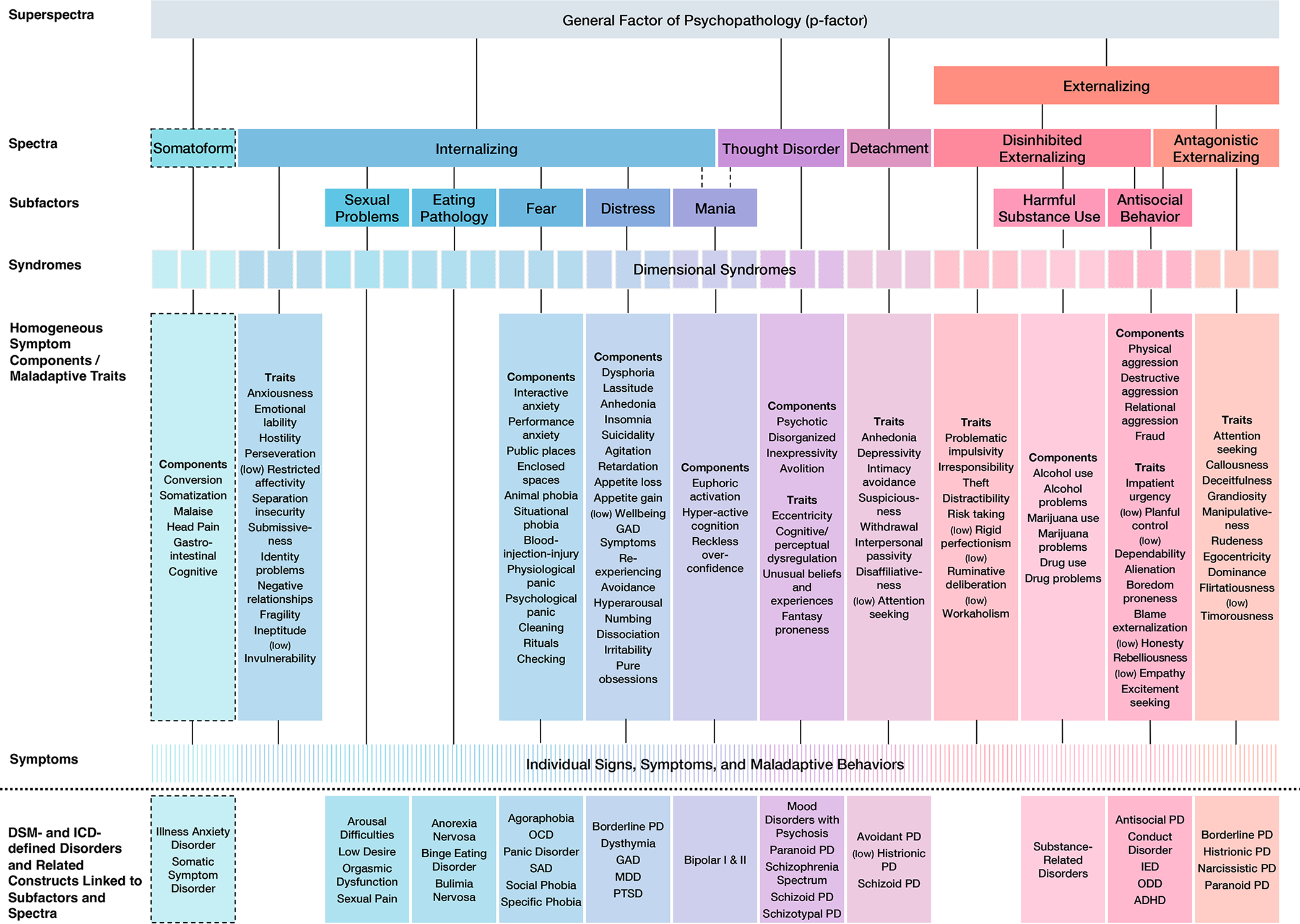

HiTOP was developed by a consortium of scientists to address shortcomings of traditional diagnostic systems (Kotov et al., 2021). It is a grass-roots effort that was inspired by quantitative studies of nosology. HiTOP uses a long-established quantitative approach, typically factor analysis, to organize psychopathology based on the covariation of signs, symptoms, and maladaptive behaviors and traits (Kotov et al., 2017). This body of work has converged on a fine-grained, hierarchical structure of psychopathology (see Table 1 for definitions of major dimensions and Figure 2). At the bottom of the hierarchy are relatively narrow symptom and trait dimensions, which are grouped into increasingly broad dimensions based on their covariation as one proceeds up the hierarchy (Kotov et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

Official baseline Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) Figure.

Note. This figure depicts the full HiTOP framework described in Kotov et al. (2017), combining the information from Figures 2 and 3, as well as features described in-text. Dashed lines indicate dimensions included as provisional aspects of the framework. Notably, the ‘disorders and related constructs linked to subfactors and spectra’ are not formal parts of the framework but were listed in Figure 2 “for convenience of communication” (p. 461) to identify the constructs that have been used in many studies of the higher-order dimensions. Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; IED, intermittent explosive disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; PD, personality disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder. © 2022. This work is licensed under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license.

The lowest levels of HiTOP include numerous specific dimensions, many of which are relevant to addiction, including alcohol use, alcohol problems, other drug use, and risk taking, to name a few (see Figure 2, “Homogeneous symptom components/maladaptive traits”). Closely related narrow dimensions are grouped into broader dimensional syndromes (e.g., alcohol-related), which are grouped into broader subfactors (e.g., substance abuse). Then, related subfactors are grouped into spectra (e.g., disinhibited externalizing, antagonistic externalizing), which in turn define superspectra (e.g., externalizing; Figure 2). SUDs are grouped in the Externalizing superspectrum, which describes the broad tendency towards poor behavioral control that manifests outwardly as dysregulated, disruptive behavior. Within Externalizing, SUDs make up the Harmful Substance Use subfactor (termed “Substance Abuse” in the original conceptualization of HiTOP, Kotov et al., 2017; but see Watts & Boness, 2022) that is situated within the Disinhibited Externalizing spectrum. Disinhibited Externalizing also includes the subfactor Antisocial Behavior, which is shared with the Antagonistic Externalizing spectrum. Disinhibited Externalizing includes tendencies to act on impulse without consideration for potential consequences, whereas Antagonistic Externalizing includes tendencies to navigate interpersonal situations with antipathy and conflict, and to hurt other people intentionally with little regard for their rights and feelings (Krueger et al., 2021).

By describing psychopathology dimensionally and hierarchically, HiTOP aims to improve: 1) the substantial unreliability of traditional diagnoses by characterizing psychopathology in terms of empirically-derived dimensions as opposed to categories, 2) the validity and clinical utility of diagnosis by better delineating disorder boundaries and enabling practitioners to treat characteristics common to multiple conditions, and 3) within-disorder heterogeneity and comorbidity by identifying coherent constructs within (splitting) and across (lumping) traditional categorical disorders. Along the way, HiTOP dimensions have been validated with respect to their incremental utility above and beyond traditional diagnostic categories (Kotov et al., 2021), as well as their etiology, course, and treatment response (Kotov et al., 2021; Krueger et al., 2018; Latzman et al., 2020).

With respect to clinical assessment, the HiTOP Clinical Translation Workgroup has developed a battery to assist clinicians in the implementation of HiTOP in practice, called the Digital Assessment and Tracker (HiTOP DAT; Ruggero et al., 2019). This battery, along with a manual that facilitates the interpretation of scores, is freely available to clinicians upon request (Kotov et al., 2021). The HiTOP-DAT takes 45 minutes to complete (https://osf.io/8hngd/) and is freely available to clinicians upon request (Kotov et al., 2021). Other training materials are available online (https://hitop.unt.edu/introduction). Also, the HiTOP Measurement Workgroup is currently developing an assessment battery with careful attention to psychometrics, structural validity, and otherwise adequate coverage of latent symptom dimensions (from the perspective of item response theory). Rather than using one or two items to assess complex constructs, which is often the case in large-scale epidemiologic efforts, HiTOP’s official battery contains around 8 items (on average) per target construct, so that much of the latent trait for each is well covered by the assessment (see (Simms et al., 2022; this measure is expected to be available to the public in late 2023).

Integrating NIDA PhAB and HiTOP

NIDA PhAB is newly developed, so direct evidence regarding NIDA PhAB and HiTOP is limited (Kotov et al., 2021), though there are clear conceptual overlaps between the dimensions outlined in NIDA PhAB and HiTOP. Briefly, we present a proposed interface between NIDA PhAB and HiTOP (Table 2). based on definitions of constructs in the two models (Table 1). We focus on connections that are most relevant to SUDs (see Michelini et al., 2021 and Kotov et al., 2021, for a broader discussion that is much less focused on SUDs).

Table 2.

Relevant intersections between NIDA PhAB domains and major HiTOP dimensions.

| NIDA PHAB Domains | HiTOP Dimension | Type of Relationship | Description of Overlap and Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Emotionality | Internalizing | Conceptually isomorphic | PhAB and HiTOP describe the same basic phenomena, the experience of negative affect (Latzman et al., 2021; Michelini et al., 2021). |

| Antagonistic Externalizing | Overlapping | Antagonistic externalizing contains tendencies towards certain forms of negative affect (i.e., anger, irritability; Krueger et al., 2021). Also, it is associated with emotion dysregulation, which also indicates internalizing. | |

| Executive Function | Disinhibited Externalizing | Conceptually isomorphic | PhAB and HiTOP describe the same basic phenomena (Michelini et al., 2021). In particular, loss of control over use is thought to reflect a critical factor that maintains substance use and addiction. Also, deficits in inhibitory control and attention appear more general to disinhibited externalizing (e.g., Krueger et al., 2021; Michelini et al., 2021). |

| Thought Disorder | Overlapping | Disordered thought is associated with deficits in a broad array of higher-order cognitive processes, including attention, cognitive control, perception (i.e., auditory and visual abnormalities), and memory (Michelini et al., 2021). | |

| Reward | Disinhibited Externalizing | Overlapping | Consummatory reward (“liking”) is implicated in early stages of addiction, promoting substance use. As one becomes addicted to a substance, reward shifts from consummatory to anticipatory (“wanting;” Robinson & Berridge, 2001). Also, broader aspects of reward processing are implicated in disinhibited externalizing (both positive and negative associations, depending on the form of disinhibited externalizing; Michelini et al., 2021). |

| Metacognition | Antagonistic Externalizing | Overlapping | Metacognition pertains to awareness of one’s thoughts and feelings, and antagonistic externalizing includes self-centeredness and the tendency to navigate interpersonal situations in an egocentric manner (Krueger et al., 2021). |

| Sleep | Internalizing | Overlapping | HiTOP Internalizing is broader than NIDA PhAB Sleep, but sleep problems (i.e., insomnia, lassitude, nightmares; Watson et al., 2021) are directly incorporated into HiTOP’s Internalizing assessment battery (Watson et al., 2021). |

| Interoception | Not enough evidence at this time. | ||

Negative emotionality.

NIDA PhAB and HiTOP outline dimensions relevant to the experience of negative emotions (e.g., sadness, worry, anger), which is termed Negative Emotionality in NIDA PhAB and is encompassed by the Internalizing spectrum in HiTOP. These two dimensions across the systems are conceptually isomorphic (Boness et al., 2021). Relatedly, NIDA PhAB’s Negative Emotionality domain is conceptually isomorphic with RDoC’s Negative Valence domain, and there is substantial support for the links between it and HiTOP Internalizing (Michelini et al., 2021). Additionally, HiTOP’s Antagonistic Externalizing contains tendencies towards certain forms of negative affect (e.g., anger, irritability), so we propose a positive link between it and NIDA PhAB Negative Emotionality (Michelini et al., 2021). Supporting this connection is the established finding that there is a marked degree of covariation among tendencies towards negative affect, antagonism, and impulsivity, each of which coalesce to form tendencies towards antagonistic forms of externalizing behavior (Krueger et al., 2021). Along these lines, Kwako and colleagues (2019) found that aggression loaded substantially on ANA’s negative emotionality domain such that it was the strongest indicator of it (see Boness et al., 2021, for a critique).

Executive function.

Most directly, we propose a link between NIDA PhAB’s Executive Function subdomain (housed under Cognition) and HiTOP’s Harmful Substance Use subfactor. Executive Function deficits include attention, working memory, response inhibition, and decision-making, each of which is empirically linked to specific aspects of the addiction cycle. In specific stages of the addiction cycle, loss of control over substance use (or inability to abstain) is thought to reflect a critical maintenance factor in relapse, and is a downstream consequence of increased negative affect from withdrawal during periods of abstinence and preoccupation over the substance and urges to use (e.g., Koob & Le Moal, 2001).

More generally, we propose linkages between NIDA PhAB’s Executive Function subdomain and HiTOP’s Disinhibited Externalizing and Thought Disorder spectra because executive control deficits tend to characterize tendencies towards rash action (i.e., disinhibited externalizing) and disordered thought (i.e., disorganized or irrational thoughts and beliefs). In fact, the NIDA PhAB battery contains tasks (e.g., delay discounting, stop signal) that are widely thought of as proxies for externalizing tendencies (Boness et al., 2021; Keyser-Marcus et al., 2021), and the cognitive control component of executive control is conceptually isomorphic with disinhibition even though the two literatures tend to use different modalities to assess their constructs (i.e., executive control tends to use laboratory-based tasks and the disinhibition literature tends to use questionnaires, interviews, and sometimes laboratory-based tasks; cf., Cyders & Coskunpinar, 2011). Finally, disordered thought is associated with deficits in a broad array of higher-order cognitive processes, including attention, cognitive control, perception (i.e., auditory and visual abnormalities), and memory (Michelini et al., 2021).

Reward.

NIDA PhAB’s Reward domain refers to a relatively narrow component of reward, incentive salience, or the motivational drive associated with a substance (Robinson & Berridge, 2001). Early on in the addiction cycle, substance use is thought to arise from consummatory reward, or “liking,” which promotes substance use. As addiction develops, the experience of reward is thought to shift from “liking” to “wanting,” or from the experience of anticipatory reward to consummatory reward. With protracted substance use, cues or stimuli associated with the substance may become especially salient or appealing, and individuals diagnosed with SUDs are thought to attribute excessive salience to substance-related cues (the so-called experience of a substance “hijacking” one’s reward system). Thus, incentive salience is, by definition, relevant to HiTOP’s Harmful Substance Use subfactor.

In addition, broader reward processing is probably implicated in several other HiTOP dimensions, including Disinhibited Externalizing and Detachment spectra, as well as the Distress subfactor. First, there are both positive and negative associations between reward sensitivity and Disinhibited Externalizing. For instance, some research suggests that impulsigenic traits are associated with increased reward sensitivity, but other research suggests that people diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (which has characteristics in the disinhibited externalizing spectra) are more likely to have deficits in features of reward processing (Michelini et al., 2021). Thus, we propose both positive and negative links between NIDA PhAB and HiTOP Disinhibited Externalizing, which will require further research and close attention to the relations between specific symptom components and specific features of reward processing and sensitivity.

Also, we propose some more provisional connections. Both psychosis and depression are associated with decreased reward sensitivity and lower positive affect, so we propose linkages between NIDA PhAB Reward and the HiTOP (a) Thought Disorder spectrum and (b) Distress subfactor. Although psychosis is technically housed within Thought Disorder and depression in Internalizing, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, which contain avolition and anhedonia, may be better placed in the Detachment superspectrum (Michelini et al., 2021). Likewise, depression is a complex construct that contains a mix of high negative affect and low positive affect, so the links between depression and reward processing may be better described by low reward sensitivity and positive affect captured in Detachment as opposed to dysphoria and anhedonia captured in Distress (Michelini et al., 2021).

Metacognition.

We propose a negative link between NIDA PhAB Metacognition and HiTOP Antagonistic Externalizing. Metacognition is included in the social cognition domain and involves an ability to look inside ourselves, perceive a relationship between ourselves and others, and to monitor our thought processes. HiTOP Antagonistic Externalizing includes tendencies to navigate interpersonal situations using antipathy and conflict, with little regard for their rights and feelings, and can be described by tendencies towards self-centeredness or egocentricity, manipulativeness, deceitfulness, rudeness, and grandiosity, which reflect a lack of attention to and care for others’ perspectives and needs (Krueger et al., 2021). Thus, narrower components of metacognition are relevant to antagonistic externalizing.

Sleep.

NIDA PhAB’s Sleep dimension probably also overlaps with HiTOP’s Internalizing spectrum given that some sleep problems (i.e., insomnia, lassitude, nightmares) are directly incorporated into the assessment of HiTOP Internalizing (Watson et al., 2021). Instead, both systems focus on the potential bidirectional associations between internalizing and sleep problems, such that stress, anxiety, and depression are thought to cause disruptions in sleep and poor sleep quality, which exacerbates anxiety and mood problems (Cox & Olatunji, 2020). Within the context of SUDs, specifically, alcohol and other substances disrupt sleep, which may elicit the causal association between sleep problems, on the one hand, and anxiety and mood problems, on the other (Koob & Colrain, 2020; Miller et al., 2020). The relevance of other sleep problems, such as circadian disorders, to NIDA PhAB and HiTOP is less clear.

Interoception.

At this time, we do not propose linkages between NIDA PhAB Interoception and HiTOP dimensions. There is limited research on the role of interoception, or awareness and processing of internal bodily states/sensations, in psychopathology (Desmedt et al., 2022). We look forward to research examining the specific interface between interoception, SUDs, and other forms of psychopathology. Currently, much attention is being paid to Interoception via the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research, the NIH BRAIN Initiative, and the NIH Director’s Pioneer Award program, all of which focus on neural circuits that underpin interoceptive processes.

Key Differences Between NIDA PhAB and HiTOP

Although NIDA PhAB and HiTOP are compatible in several ways, there are important differences between them. NIDA PhAB exists exclusively for the field of addiction drug and therapeutics development research, whereas HiTOP incorporates dimensions that span most forms of psychopathology. NIDA PhAB outlines dimensions salient to addiction, but they are almost certainly implicated in other psychopathology as well (Boness et al., 2021). For instance, as we mentioned earlier, NIDA PhAB’s Negative Emotionality domain likely contains mechanisms relevant to HiTOP’s Internalizing spectrum. Also, certain presumably substance-specific behaviors (e.g., drunk driving) may reflect liability for a broad swath of externalizing psychopathology.

First, notwithstanding the expected content overlap of NIDA PhAB and HiTOP dimensions, they stem from different conceptual backgrounds. HiTOP is broad and descriptive, and NIDA PhAB is narrow in terms of its exclusive focus on SUDs but deep in terms of focus on mechanisms. Indeed, whereas HiTOP is relatively agnostic regarding etiological processes, focusing instead on the empirical covariance structure of symptoms, both ANA and NIDA PhAB were influenced by Koob and LeMoal’s model of addiction (2001). Nevertheless, although NIDA PhAB and HiTOP stem from different conceptual backgrounds, existing evidence from nonhuman animal paradigms that influenced most modern models of addiction supports the viability of individual difference focused accounts of SUD and addiction, such as HiTOP. In fact, focusing on individual differences appears promising for precision medicine efforts in the treatment of alcohol use disorder (Kuhlemeier et al., 2021). Relatedly, critical yet largely unchartered territory for HiTOP and NIDA PhAB is their integration into experimental paradigms, which have also historically neglected individual differences. NIDA PhAB already incorporates laboratory-based tasks that are often used in experimental paradigms, and it has the potential to enrich existing experimental paradigms. Also, HiTOP has begun to incorporate popular constructs in laboratory paradigms, such as delay discounting, into its assessment battery. An added benefit of translating between the constructs outlined in NIDA PhAB and HiTOP is that doing so offers the opportunity for reverse translation between constructs studied in preclinical nonhuman animal models and in human laboratory paradigms, which will likely increase consilience between siloes of addiction science (Kotov et al., 2022).

Second, in HiTOP, SUDs are squarely positioned under the Disinhibited Externalizing subfactor. Nevertheless, NIDA PhAB’s model implies that SUDs involve mechanisms that are dispersed around the HiTOP model (see the “Integrating NIDA PhAB and HiTOP” section for more examples). As one example, NIDA PhAB incorporates Negative Emotionality and Sleep domains, which are more closely aligned with HiTOP Internalizing than they are with Externalizing and its subforms. As empirical work mounts, if it suggests that subcomponents of SUDs do not fit into Disinhibited Externalizing, the model may be revised.

Third, within the context of PhAB and ANA, negative emotionality may be viewed primarily as an acquired as opposed to premorbid characteristic. The model that inspired ANA and NIDA PhAB does not necessarily account for a premorbid “pathway” to addiction whereby dispositional negative emotionality increases the risk for later substance use and misuse (Hussong et al., 2011). Similarly, in this model (Koob & Le Moal, 2001), withdrawal and negative affect are followed by preoccupation and anticipation, which entails a loss of control over consumption and self-regulation (i.e., executive functioning). Again, this model conceptualizes loss of control as a feature that is acquired throughout the addiction cycle, but there is considerable evidence that dispositional or otherwise premorbid disinhibition (which entails the inability to suppress an inappropriate or unwanted behavior, such as substance use) is among the foremost risk factors for substance use and misuse (Krueger et al., 2021). Accordingly, at this time, HiTOP does not necessarily differentiate acute (or state-like) disinhibition that is acquired from alcohol consumption from dispositional externalizing tendencies. Ultimately, both dispositional and state-like increases in disinhibition after accounting for dispositional disinhibition are important in the prediction of negative consequences associated with alcohol use (Moeller & Dougherty, 2002).

Although PhAB is informed by a model that describes addiction as cyclical in nature, it does not currently attempt to differentiate acquired and premorbid characteristics of addiction. Similarly, HiTOP’s current model distinguishes transient symptoms from stable traits but does not specifically identify acquired characteristics (see Boness et al., 2021, for a discussion). Nevertheless, doing so is likely critical in terms of identifying treatment targets, causes, and consequences of addiction (Perkins et al., 2020). The inattention to separating premorbid characteristics from acquired, state-like addiction characteristics likely limits our ability to map trajectories of SUD, both in treatment (e.g., risk for returning to harmful use, treatment adherence, arrest) and basic research (e.g., prospective, longitudinal studies of risk for substance use and associated harm across the lifespan).

Relatedly, neither HiTOP nor NIDA PhAB – at least in terms of cross-sectional assessments of their dimensions – most adequately capture complex dynamics among components of SUD. Nevertheless, the dimensions articulated in both systems are likely to serve as useful targets in intensive longitudinal designs that aim to characterize the temporal unfolding of SUDs over time. Thus, including information about the course of illness is an important future direction for both HiTOP and NIDA PhAB. Ultimately, both NIDA PhAB and HITOP can provide a broad and deep clinical characterization of people with SUDs, but from complementary perspectives, reinforcing the need to study, implement, and refine them in tandem.

Applications of HiTOP and NIDA PhAB to a Research Question

SUDs are increasingly conceptualized as continuously distributed in the population, phenotypically and etiologically heterogeneous, and overlapping with numerous other forms of psychopathology. Yet, the modal research question fails to conceptualize SUDs as such. Clinical addictions research overwhelmingly relies on case-control designs that compare individuals diagnosed with SUDs with controls, or even heavy drinkers with light drinkers, and many times these studies screen out participants with marked degrees of other psychopathology. This common type of study design presumes that SUDs (1) are categorical (by virtue of a diagnostic cut-off); (2) are unitary, such that varied symptom presentations are treated as equally indicative of disorder (cf., Lane & Sher, 2015); and (3) occur in a vacuum, with other forms of psychopathology bearing no relevance to the research question. Regarding the latter problem, in particular, it is increasingly unlikely that many of SUDs’ correlates and causes are unique to SUD given robust empirical support for transdiagnostic dimensions of psychopathology and proposed mechanisms underlying them (e.g., Walters et al., 2018).

Consider a project that aims to identify risk factors for future return to harmful use among individuals diagnosed with opioid use disorder who achieved 12 months of abstinence from all substances and improved quality of life. A DSM-based study designed to examine this research question may reveal that persistent craving, severity of opioid use disorder during its worst episode, and the number of failed abstinence attempts, predict a return to harmful use following the 12-month abstinence period. Presuming other psychopathology was assessed, the study may also find that comorbid disorders (e.g., depressive disorder, antisocial personality) increased risk of return to harmful use (e.g., Stein et al., 2021; Votaw et al., 2020),

HiTOP and NIDA PhAB take a different approach, and their conceptualization of psychiatric phenomena has several potential benefits for research. First, because psychopathology is conceptualized and assessed as dimensional, each psychopathology dimension is more likely to have sufficient variance to be examined meaningfully in a variety of samples. As we mentioned earlier, HiTOP’s under-development battery, as well as its existing battery of well-validated instruments (Ruggero et al., 2019), were composed with careful attention to psychometrics, so that much of the latent trait for each is well covered by the assessment (see Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2022, for a description of stage 1 of the HiTOP Externalizing battery; all HiTOP spectra have a paper in this special issue). More generally, there are several HiTOP-conformant dimensional, omnibus assessments of psychopathology, so interested researchers need not rely on the HiTOP battery per se. Rather than using one or two items to assess complex constructs like anhedonia, HiTOP-conformant dimensional assessments contain several (e.g., 8) items per target construct. This psychometric approach provides sufficient variability in psychopathology, which improves statistical power to detect external correlates of SUDs and risk for return to harmful use.

Second, HiTOP-inspired research questions do not apply diagnostic cutoffs, nor do they screen out participants for comorbid psychopathology. Rather, NIDA PhAB and HiTOP-conformant research draws participants either from the non-treatment seeking or treatment-seeking populations, or both, to capture a range of variance in the dimensions of interest, and include participants with a variety of substance use profiles. Importantly, HiTOP’s treatment of psychopathology as dimensional is associated with increased reliability and validity (e.g., Markon et al., 2011). Although more traditional designs may assess other forms of psychopathology, treating them as categorical limits statistical power to detect patterns of comorbidity and external correlates.

Sampling based on diagnostic categories is not advisable for many questions in psychopathology research, but oversampling individuals who fall at the high-risk end of the dimension in question can be quite useful for research. For a treatment intervention, clinical trial, or a more general study of a particular SUD, investigators might sample patients with a sufficiently high elevation (e.g., at least 1.5 standard deviations from the norm) on a corresponding HiTOP dimension (e.g., externalizing) to ensure that the sample includes participants who are most likely to benefit from the target treatment. For a future medication trial adopting such an approach, for example, investigators might take a reverse translational approach whereby they recruit a sample of patients with elevated degrees of HiTOP Internalizing or NIDA PhAB Negative Emotionality to investigate the effectiveness of a medication that targets narrow biological mechanism(s) associated with the experience of negative emotionality. If the medication is effective in reducing internalizing symptoms, it may indicate a possible biological mechanism. Such medication may then be useful for treating multiple forms of psychopathology that are housed under the internalizing dimension. Further, rather than screening out other, likely comorbid disorders, researchers can use assessment of other HiTOP dimensions to statistically covary them, or investigate the extent to which a putative SUD-specific finding (e.g., SUDs and delay discounting) is general to some broader dimension (e.g., externalizing; Quinn & Harden, 2013).

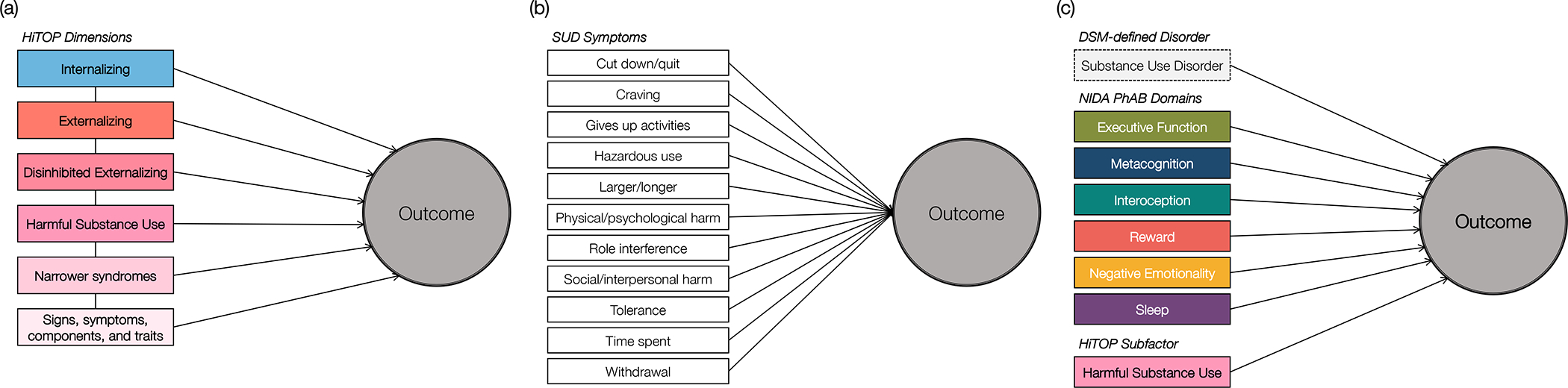

Third, the thorough assessment of psychopathology associated with HiTOP-inspired study designs enables investigators to consider over 100 dimensions of psychopathology besides the current symptoms of SUDs. Assessment of other forms of psychopathology allows researchers to ask a variety of questions (Figure 3). In Figure 3, we display several research questions addressed with HiTOP and NIDA PhAB.1 As one example, a HiTOP-informed study design can ask whether the association between opioid use disorder and return to harmful use is specific to opioid use disorder or is more general to other forms of psychopathology (e.g., externalizing, internalizing; Figure 3a), which may reveal additional predictors of opioid use that would be overlooked by focusing exclusively on that specific diagnostic category. Such predictors might include maladaptive traits of risk-taking and excitement seeking from the Disinhibited Externalizing spectrum, anxiousness and emotional liability from the Internalizing spectrum, and unusual beliefs from the Thought Disorder spectrum. A key advantage of HiTOP’s hierarchical treatment of psychopathology is that it allows researchers to attempt to pinpoint specific symptom components of disorders that increase the risk of returning to harmful use following treatment, such as anxiousness and emotional liability, which are narrower facets of several internalizing disorders. Further, finding that return to harmful use is associated with other forms of psychopathology may generate additional research questions, such as whether the associations between opioid use disorder and subsequent harmful use after a period of abstinence (or reduced use) are due to one or more transdiagnostic mechanisms that are shared across numerous disorders (e.g., antisocial personality disorder, depression, schizophrenia).

Figure 3.

Research questions facilitated by NIDA PhAB and HiTOP.

Note. Figure 3a facilitates questions regarding the extent to which a finding between a given disorder (harmful substance use) and an outcome is more specific to a subset of symptoms, or more general to broader transdiagnostic dimensions. Figure 3b facilitates comparison of substance use disorder heterogeneity, to test whether a disorder’s association with an outcome is specific to one or more symptoms within the disorder. Figure 3c facilitates comparison of the utility of diagnoses, mechanism-focused dimensions outlined in NIDA PhAB, and HiTOP dimensions in the statistical prediction of an outcome.

Fourth, HiTOP’s hierarchical organization also allows researchers to answer questions about SUD heterogeneity, such as whether the association between relapse and opioid use disorder is most robust at the level of a specific symptom, a set of symptoms, or the diagnosis itself (Figure 3b). For instance, a return to harmful use after abstinence may be attributable to a narrower set of symptoms within opioid use disorder, such as continued use despite physical or psychological harm and withdrawal. In sum, HiTOP provides a richer risk profile and can inspire hypotheses about why these characteristics increase risk (e.g., risk taking may lead to harmful use because the person underestimates long-term negative consequences) but does not include tools for testing such mechanisms.

Hence, a NIDA PhAB-informed study design compliments a HiTOP-informed one in several ways. NIDA PhAB includes measures of several processes, or mechanisms, implicated in addiction. Thus, it can increase both the predictive and explanatory power of the causes of addiction. For instance, a NIDA PhAB study design may reveal predictors of a return to harmful use after abstinence that are more aligned with specific etiologic mechanisms, such as high delay discounting in the Executive Function domains, low distress tolerance in the Negative Emotionality domain, high alexithymia in the Interoception domain, and negative beliefs about the controllability of thoughts in the Metacognition domain. Also, NIDA PhAB is more focused on addiction than is HiTOP, and, in many respects, its assessment of SUDs is finer-grained.

Along these lines, the joint assessment of NIDA PhAB and HiTOP constructs also facilitates important research questions. One such question might consider the incremental contribution of NIDA PhAB domains and HiTOP dimensions above and beyond DSM-defined disorders, as well as above and beyond each other, in the statistical prediction of clinical outcomes, such as a return to harmful use after abstinence or improvements in quality of life. Another research question might attempt to better tie HiTOP dimensions to mechanisms by way of NIDA PhAB’s domains given that they are more directly tied to mechanisms and explanatory frameworks such as RDoC. In sum, an assessment battery that includes NIDA PhAB and HiTOP constructs provides a thorough broad and deep evaluation of potential risk factors.

Hypothetical Application of HiTOP and NIDA PhAB to Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment

In applied practice settings, the joint implementation of NIDA PhAB and HiTOP will allow for an efficient clinical assessment approach that provides a general broadband screener for psychopathology to assess comorbidity within patients with SUDs (HiTOP) as well as a deeper dive into more specific phenotypes of interest (NIDA PhAB). An integrated assessment approach can also be flexible, in that the battery can be adjusted as needed depending on the researcher or clinician’s needs or the resolution of interest (i.e., superspectra, spectra, subcomponents). In terms of expanding access to SUD care, routine assessments across all HiTOP spectra (including brief ones) may identify people with high degrees of SUD, or those at risk for it, even when harmful substance use is not the presenting complaint.

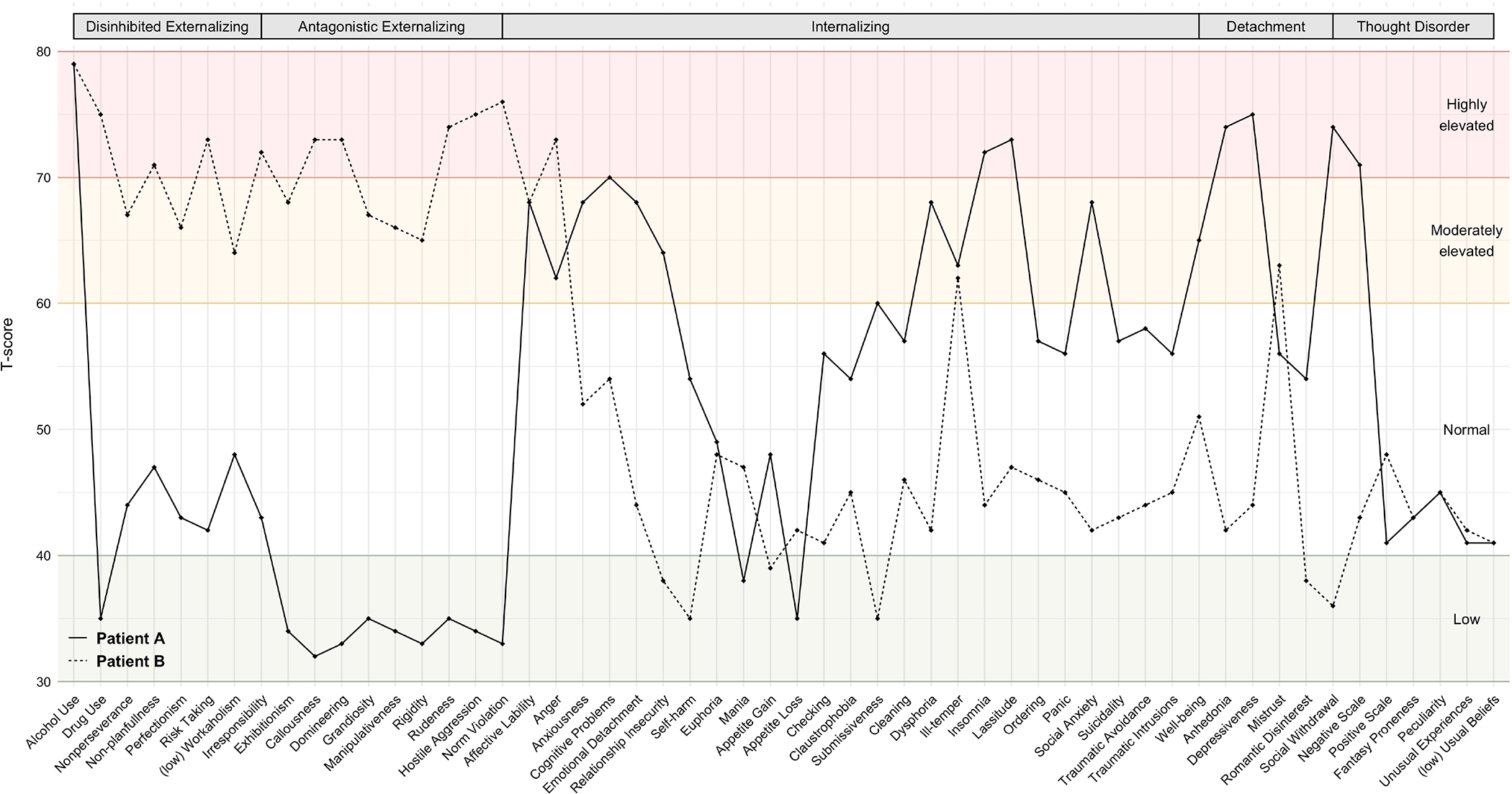

Consider two hypothetical patients diagnosed with AUD. With a thorough assessment of psychopathology provided by HiTOP’s battery, we see that they differ fairly dramatically in terms of patterns of comorbidity (Figure 4): Patient A exhibits elevations on alcohol use, other drug use, several dimensions of externalizing (i.e., risk taking, irresponsibility, callousness, domineering, rudeness, hostile aggression, norm violation, anger), and low to normal levels of dimensions of internalizing, detachment, and thought disorder. In terms of NIDA PhAB’s battery, Patient A also scores highly on Reward, per their performance on the hypothetical purchase task. Patient B, in contrast, exhibits elevations in alcohol use but not drug use, dimensions of internalizing (i.e., insomnia, lassitude), detachment (i.e., anhedonia, depressiveness), and thought disorder (i.e., negative symptoms). They also score highly on NIDA PhAB’s Negative Emotionality domain per their scores on various measures of negative affect and their performance on the emotional no-go task. Both patients clearly have different profiles of comorbidity, suggesting they might benefit from different treatments. In both cases, because each patient’s HiTOP-informed psychopathology profiles suggest comorbidities, therefore we might choose a transdiagnostic treatment that addresses both areas of dysfunction, rather than an alcohol-specific treatment (see Boness et al., 2021, Table 3, for examples of treatments that may be most effective for specific clinical presentations). Patient A’s clinical profile suggests that they might benefit from treatments that target broader externalizing or reward sensitivity, whereas Patient B’s profile of internalizing and negative emotionality suggests that they may benefit from a transdiagnostic treatment that targets negative emotionality more generally.

Figure 4.

Hypothetical patient profiles of HiTOP psychopathology dimensions.

Note. Patient A is displayed as a solid line and Patient B is displayed as a dashed line. Scores on HiTOP syndrome scales are displayed as T-scores.

Of course, these examples are necessarily hypothetical. By presenting these case examples and their comorbidity profiles, we hope to illuminate how clinicians may personalize treatment, both pharmacological and psychological, to specific symptom profiles. These efforts are consistent with treatment movements that target transdiagnostic dimensions (i.e., negative emotionality; Harvey et al., 2004), as well as with broader precision or personalized medicine efforts in addiction (Litten et al., 2015; Volkow, 2020; Witkiewitz et al., 2019). Nevertheless, efforts to link specific symptoms or subdimensions of SUD with treatments are in their relative nascence, which further highlights the immense importance of research that parses heterogeneity in SUDs and ties them to specific mechanisms and processes.

HiTOP and NIDA PhAB: Moving Forward

HiTOP and NIDA PhAB provide powerful alternatives to traditional classification systems and their diagnostic constructs. Still, in their current forms, both HiTOP and NIDA PhAB possess other important limitations that are worth mentioning. In this section, we detail past and ongoing initiatives to revise the HiTOP and NIDA PhAB systems with an eye towards (1) improving their utility in intervention and prevention, and (2) improving diversity, equity, and inclusion in psychopathology classification.

The DSM remains dominant and seemingly pragmatically necessary in clinical settings.

One limitation of HiTOP in its current state is that it cannot yet supplant DSM for the purposes of insurance reimbursement, disability, and service eligibility. Nevertheless, the DSM’s dominance in clinical settings does not imply that it is more useful: Surveys of clinicians find that formal diagnoses are generally perceived as having only limited usefulness in treatment selection and prognostication, and are is used primarily for billing, training, and communication among professionals (First et al., 2018). Further, psychiatrists often rely on presenting symptoms rather than diagnoses to plan treatment (Waszczuk et al., 2017), and clinicians rate dimensional approaches as more clinically useful than the DSM (Milinkovic & Tiliopoulos, 2020). Nevertheless, because clinical decisions are usually dichotomous and different actions are appropriate for different levels of severity, HiTOP articulates multiple severity ranges on its dimensions, each indicating a particular action (e.g., low range for prevention, higher for outpatient treatment). Traditional diagnosis, in contrast, provides only one threshold (although a hybrid diagnostic model is notable in the DSM-5’s handling of SUD, which recognizes a severity range above a minimum threshold). To improve HiTOP’s clinical utility, the consortium recently published a crosswalk between HiTOP constructs and ICD-10-CM codes to help clinicians translate between them. All told, given the limitations of both DSM and HiTOP, traditional diagnoses and dimensional diagnoses can co-exist and complement each other.

HiTOP and NIDA PhAB’s focus on graded manifestations of psychopathology are useful for prevention.

A promising avenue for HiTOP and NIDA PhAB surrounds prevention. Because HiTOP and NIDA PhAB thoroughly characterize subthreshold psychopathology and provide a graded, multidimensional picture of vulnerabilities, they are better suited than the DSM and ICD to identify high-risk groups than most diagnostic manuals, which provide little guidance for identifying individuals with subclinical psychopathology. Also, because the standard in diagnostic assessments is a structured or semi-structured clinical interview, the DSM and ICD’s scalability is limited. In contrast, HiTOP can be assessed either by interview or self-report (Simms et al., 2022). To facilitate dissemination and implementation in prevention-based efforts, HiTOP is developing a screener that can be used to identify elevated spectra and refer people for care and further evaluation. Either the screener or the full inventory can be distributed to diverse populations (e.g., students in a school, patients in a primary care clinic), facilitating large-scale addiction detection, treatment, and prevention.

HiTOP and NIDA PhAB must attend to social determinants of health as they pertain to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

To adequately improve the field’s ability to reduce the burden of mental illness, HiTOP and NIDA PhAB must grapple with the fact that many modern conceptualizations of psychopathology are based on Western norms and ideals. HiTOP is often studied and validated on predominantly white, U.S. based samples (Verona, 2022). Although the initial validation study of the PhAB includes a more racially diverse sample, (64% of participants identified as Black/African American), additional multi-center validation studies need to be performed with special attention to recruiting diverse samples, and taking those differences into account when examining outcomes. Moving forward, it is imperative for both systems to consider their generalizability to, or invariance across, a broad array of populations. Several large studies have provided initial evidence for the generalizability of HiTOP’s structure, particularly internalizing and externalizing dimensions, across different countries, gender, age, and sexual orientation (see Eaton, 2020, for a review). Nevertheless, both HiTOP and NIDA PhAB should not consider the issue of invariance completely resolved until their models are validated in a wider array of subpopulations.

A potential benefit of HiTOP defined dimensions is that may avoid some of the biases and stigma associated with DSM-defined diagnoses (Eaton, 2020). Consider the extent of comorbidity associated with a SUD diagnosis. People diagnosed with a SUD are at substantially increased risk for a broad swath of diagnoses: antisocial personality disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, other personality disorders (e.g., borderline), conduct disorder, and other impulse control disorders, to name a few (Tully & Iacono, 2016). The notion that a person “has” 5 or more diagnoses contributes to stigma, but this multi-diagnosis stigma is at least in part due to DSM’s drawing arbitrary boundaries around interrelated phenomena (Eaton, 2020). In the case of the diagnoses we just mentioned, HiTOP’s conceptualization of this particular patient could be described more parsimonioously as a broad elevation on the Externalizing superspectrum, reducing the number of labels from 5 to 1. Within the context of SUDs and addiction, attention toward decreasing stigma in psychiatric classification is particularly urgent given that SUDs are among the most stigmatized mental disorders (Kilian et al., 2021).

Moreover, diagnostic literalism by means of close adherence to DSM-defined criteria obscures the fact that SUD criteria may contribute to mis- or overdiagnosis due to societal assumptions regarding alcohol and other drug use, which have historically manifested in racist and moralistic drug policies (Jordan et al., 2020). This (mis)classification concern is more practical than abstract, too: The legal problems criterion for SUD was removed from DSM-5 just ten years ago because it contributed to overdiagnosis of SUD among people with marginalized racial and ethnic identities, and underdiagnosis in women (e.g., Saha et al., 2006). Thus, attention to invariance across a variety of subgroups and sociocultural contributors to addiction and other psychopathology may pay dividends with respect to improving equity in psychiatric classification. In addition to ongoing attention towards invariance in HiTOP, NIDA PhAB is currently developing its model to include sociocultural aspects of addiction.

Finally, Verona (2022) rightly emphasized that our nosologies are pervaded by “individualism,” or the assumption that “all mental disorders are constituted by bodily states and processes (viz., behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunctions and the symptomatic patterns they produce) within the individual who has the disorder” (Poland, 2015, p. 28). This assumption is exemplified by the fact that the Brain Disease Model of addiction (Koob & Le Moal, 2001) remains widely popular, owing to the field’s more general emphasis on neurobiological models of psychopathology. Often overlooked in these models is the role of social and environmental factors that might contribute to addiction (Heather et al., 2022), such as stress resulting from racism, sexism, and so on (Jordan et al., 2020), which are difficult to incorporate into nonhuman animal models.

Advancing Deep Phenotyping in Addictions

NIDA PhAB and HiTOP reflect two highly complementary frameworks that, when integrated, may reflect more than the sum of their parts. In particular, both NIDA PhAB and HiTOP provide empirically based deep phenotyping needed to accelerate progress in understanding the causes and consequences of substance use and other psychopathology. NIDA PhAB’s treatment-oriented biobehavioral framework generated from theoretical and preclinical nonhuman animal models of addiction will likely illuminate the neurophysiological underpinnings of substance use and addiction-relevant dimensions outlined in HiTOP, which can ultimately be directly incorporated into HiTOP and other psychiatric taxonomies. HiTOP can provide psychometrically robust clinical targets for NIDA PhAB given that NIDA PhAB emphasized basic processes and provides little information on signs and symptoms.

Together, NIDA PhAB and HiTOP can facilitate the clinical application of biobehavioral frameworks like RDoC by providing a crosswalk between clinical presentation and neuroscience-based constructs. Treating dimensions outlined in NIDA PhAB and HiTOP will likely be more efficient than treating DSM- and ICD-defined disorders (Ruggero et al., 2019), and focusing on them can aid in the development of novel, personalized treatments that target specific mechanisms responsible for SUDs and addiction. Through deep phenotyping approaches facilitated by NIDA PhAB and HiTOP, treatments can be better matched to person-specific profiles, which is consistent with precision medicine efforts (Litten et al., 2015).

Public health significance statement:

Two recently developed frameworks, NIDA’s Phenotyping Assessment Battery (NIDA PhAB) and the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), provide unique opportunities for deep phenotyping in addictions. NIDA PhAB focuses on addiction-related processes, whereas HiTOP focuses on clinical phenotypes relevant to a broad array of psychopathology. Together, they provide broad and deep characterization of people diagnosed with SUDs.

Funding and Related Acknowledgements:

ALW is funded through K99AA028306 (Principal Investigator: Watts). RFK is supported by R01MH122537. The development of NIDA PhAB was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD) grant U54DA038999. TR was substantially involved in U54DA038999, consistent with her role as Scientific Officer. TR had no substantial involvement in the other cited grants. The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy or position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Footnotes

Conway and colleagues (2022) recently developed a tutorial that guides researchers through statistical tests of the conceptual models (among others) displayed in Figure 3, with open data and R code. In addition to the examples provided here, other HiTOP papers have outlined possible research questions that are broadly applicable to psychopathology (Conway et al., 2019; Latzman et al., 2021).

Scientific Knowledge Dissemination: This manuscript has been posted on OSF and PsyArXiv as of July 20, 2022 (https://osf.io/3pmw4/; DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/3PMW4).

References

- American Psychiatric Association, & American Psychiatric Association (Eds.). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzley BS, Han SS, Neuner S, Humphreys K, Kampman KM, & Halpern CH (2021). Comparison of treatments for cocaine use disorder among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 4(5), e218049–e218049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boness CL, Watts AL, Moeller KN, & Sher KJ (2021). The etiologic, theory-based, ontogenetic hierarchical framework of alcohol use disorder: A translational systematic review of reviews. Psychological Bulletin, 147(10), 1075–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway CC, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Fried EI, Hallquist MN, Kotov R, Mullins-Sweatt SN, Shackman AJ, Skodol AE, South SC, Sunderland M, Waszczuk MA, Zald DH, Afzali MH, Bornovalova MA, Carragher N, Docherty AR, Jonas KG, Krueger RF, … Eaton NR (2019). A Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology Can Transform Mental Health Research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 419–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway CC, Forbes MK, & South SC (2022). A Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) primer for mental health researchers. Clinical Psychological Science, 10(2), 236–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RC, & Olatunji BO (2020). Sleep in the anxiety-related disorders: A meta-analysis of subjective and objective research. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 51, 101282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Coskunpinar A (2011). Measurement of constructs using self-report and behavioral lab tasks: Is there overlap in nomothetic span and construct representation for impulsivity? Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 965–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmedt O, Luminet O, Maurage P, & Corneille O (2022). Discrepancies in the Definition and Measurement of Interoception: A Comprehensive Discussion and Suggested Ways Forward. PsyArXiv. h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR (2020). Measurement and mental health disparities: Psychopathology classification and identity assessment. Personality and Mental Health, 14(1), 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Rebello TJ, Keeley JW, Bhargava R, Dai Y, Kulygina M, Matsumoto C, Robles R, Stona A-C, & Reed GM (2018). Do mental health professionals use diagnostic classifications the way we think they do? A global survey. World Psychiatry, 17(2), 187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Smith SM, Pickering RP, Huang B, & Hasin DS (2016). Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(1), 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A, Watkins E, Mansell W, & Shafran R (2004). Cognitive Behavioural Processes across Psychological Disorders (DRAFT): A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, Compton WM, Crowley T, Ling W, Petry NM, Schuckit M, & Grant BF (2013). DSM-5 criteria for Substance Use Disorders: Recommendations and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(8), 834–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum AS, Johnson EC, Colbert SMC, Polimanti R, Zhou H, Walters RK, Gelernter J, Edenberg HJ, Bogdan R, & Agrawal A (2021). The addiction risk factor: A unitary genetic vulnerability characterizes substance use disorders and their associations with common correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Field M, Moss AC, & Satel S (Eds.). (2022). Evaluating the brain disease model of addiction. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, & Boeding S (2011). An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(3), 390–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Mathis ML, & Isom J (2020). Achieving Mental Health Equity: Addictions. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 43(3), 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Knudsen GP, Røysamb E, Neale MC, & Reichborn-Kjennerud T (2011). The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal and subsyndromal common DSM-IV Axis I and all Axis II disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(1), 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Prescott CA, Crabbe J, & Neale MC (2012). Evidence for multiple genetic factors underlying the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. Molecular Psychiatry, 17(12), 1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyser-Marcus LA, Ramey T, Bjork J, Adams A, & Moeller FG (2021). Development and Feasibility Study of an Addiction-Focused Phenotyping Assessment Battery. The American Journal on Addictions, ajad.13170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian C, Manthey J, Carr S, Hanschmidt F, Rehm J, Speerforck S, & Schomerus G (2021). Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: An updated systematic review of population studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(5), 899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, & Colrain IM (2020). Alcohol use disorder and sleep disturbances: A feed-forward allostatic framework. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(1), 141–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, & Le Moal M (2001). Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(2), 97–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Cicero DC, Conway CC, DeYoung CG, Dombrovski A, Eaton NR, First MB, Forbes MK, Hyman SE, Jonas KG, Krueger RF, Latzman RD, Li JJ, Nelson BD, Regier DA, Rodriguez-Seijas C, Ruggero CJ, Simms LJ, Skodol AE, … Wright AGC (2022). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) in psychiatric practice and research. Psychological Medicine, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, Brown TA, Carpenter WT, Caspi A, Clark LA, Eaton NR, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Goldberg D, Hasin D, Hyman SE, Ivanova MY, Lynam DR, Markon K, … Zimmerman M (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Cicero DC, Conway CC, DeYoung CG, Eaton NR, Forbes MK, Hallquist MN, Latzman RD, Mullins-Sweatt SN, Ruggero CJ, Simms LJ, Waldman ID, Waszczuk MA, & Wright AGC (2021). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A quantitative nosology based on consensus of evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 83–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, & McGue M (2002). Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(3), 411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hobbs KA, Conway CC, Dick DM, Dretsch MN, Eaton NR, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Keyes KM, Latzman RD, Michelini G, Patrick CJ, Sellbom M, Slade T, South SC, Sunderland M, Tackett J, Waldman I, Waszczuk MA, … HiTOP Utility Workgroup. (2021). Validity and utility of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): II. Externalizing superspectrum. World Psychiatry, 20(2), 171–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Kotov R, Watson D, Forbes MK, Eaton NR, Ruggero CJ, Simms LJ, Widiger TA, Achenbach TM, Bach B, Bagby RM, Bornovalova MA, Carpenter WT, Chmielewski M, Cicero DC, Clark LA, Conway C, DeClercq B, DeYoung CG, … Zimmermann J (2018). Progress in achieving quantitative classification of psychopathology. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 282–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, & Iacono WG (2005). Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: A dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(4), 537–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlemeier A, Desai Y, Tonigan A, Witkiewitz K, Jaki T, Hsiao Y-Y, Chang C, & Van Horn ML (2021). Applying methods for personalized medicine to the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(4), 288–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Wall MM, Krueger RF, Sher KJ, Maurer E, Thuras P, & Lee S (2012). Alcohol dependence is related to overall internalizing psychopathology load rather than to particular internalizing disorders: Evidence from a national sample: alcohol dependence is related to overall internalizing psychopathology. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(2), 325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Momenan R, Litten RZ, Koob GF, & Goldman D (2016). Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment: A neuroscience-based framework for addictive disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 80(3), 179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SP, & Sher KJ (2015). Limits of current approaches to diagnosis severity based on criterion counts: An example with DSM-5 alcohol use disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(6), 819–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, DeYoung CG, & THE HITOP NEUROBIOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS WORKGROUP. (2020). Using empirically-derived dimensional phenotypes to accelerate clinical neuroscience: The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) framework. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(7), 1083–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Krueger RF, DeYoung CG, & Michelini G (2021). Connecting quantitatively derived personality–psychopathology models and neuroscience. Personality Neuroscience, 4, e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Falk DE, Reilly M, Fertig JB, & Koob GF (2015). Heterogeneity of alcohol use disorder: Understanding mechanisms to advance personalized treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(4), 579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Chmielewski M, & Miller CJ (2011). The reliability and validity of discrete and continuous measures of psychopathology: A quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(5), 856–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Langenbucher JW, Chung T, & Sher KJ (2014). Truth or consequences in the diagnosis of substance use disorders. Addiction, 109(11), 1773–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell YE, Vergés A, & Sher KJ (2019). Are some alcohol use disorder criteria more (or less) externalizing than others? Distinguishing alcohol use symptomatology from general externalizing psychopathology. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(3), 483–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Koob GF, & Volkow ND (2022). Preaddiction—A Missing Concept for Treating Substance Use Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini G, Palumbo IM, DeYoung CG, Latzman RD, & Kotov R (2021). Linking RDoC and HiTOP: A new interface for advancing psychiatric nosology and neuroscience. Clinical Psychology Review, 86, 102025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milinkovic MS, & Tiliopoulos N (2020). A systematic review of the clinical utility of the DSM–5 section III alternative model of personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11(6), 377–397. 10.1037/per0000408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Freeman L, Curtis AF, Boissoneault J, & McCrae CS (2020). Sleep Health and Alcohol Use. In Neurological Modulation of Sleep (pp. 255–264). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]