Abstract

In the environment, aquatic organisms are not only directly exposed to pollutants, but the effects can be exacerbated along the food chain. In this study, we investigated the effect of the food (water flea) on the secondary consumer (zebrafish) with the exposure diclofenac (DCF) Both organisms were exposed to an environmentally relevant concentrations (15 µg/L) of diclofenac for five days, and zebrafish were fed exposed and non-exposed water fleas, respectively. Metabolites of the water fleas were directly analyzed using HRMAS NMR, and for zebrafish, polar metabolite were extracted and analyzed using liquid NMR. Metabolic profiling was performed and statistically significant metabolites which affected by DCF exposure were identified. There were more than 20 metabolites with variable importance (VIP) score greater than 1.0 in comparisons in fish groups, and identified metabolites differed depending on the effect of exposure and the effect of food. Specifically, exposure to DCF significantly increased alanine and decreased NAD + in zebrafish, which means energy demand was increased. Additionally, the effects of exposed food decreased in guanosine, a neuroprotective metabolite, which explained that the neurometabolic pathway was perturbated by the feeding of exposed food. Our results which short-term exposed primary consumers to pollutants indirectly affected the metabolism of secondary consumers suggest that the long-term exposure further study remains to be investigated.

Keywords: Diclofenac, Metabolomics, Aquatic food chain, Zebrafish

Introduction

Aquatic pollution is a global concern. Many impacts of water pollution had been investigated, but most of the research was on a single organism. In a natural environment, aquatic organisms are not only affected by environmental concentrations, but chemicals could also transmit to higher organisms along the food chain. Some previous studies have investigated the food chain effects of environmental pollutants such as heavy metals, microplastics, nanoparticles and nanowires, and industrial organics in aquatic systems [1–4]. These studies showed chemicals could transfer along the experimental aquatic food chain. However, they considered the chemical exposures on only a single organism (food) without considering the effects of their consumers’ environments. On the other hand, most previous studies have performed the chemical exposure experiment with undegradable chemical compositions. There is little study based on the effect of residual drugs on the food chain.

Diclofenac (DCF), a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is widely used to treat rheumatic diseases, chronic inflammatory arthritis in medicine, and joint diseases [5], but has a low absorption rate. Most ingested drugs will be excreted by urine and feces after oral administration, and it is not completely removed from wastewater treatment plants due to their poor degradation and high consumption rates [6, 7]. Since the early 2000s, DCF has become one of the most detectable residual drugs in water [8], with concentrations ranging from microgram to nanogram level. It could already be detected in concentrations of 15 µg/L in pond and river waters twenty years ago [9], the highest concentration ever measured in the industrial area was 216 µg/L [10].

For this study, two aquatic organisms, water flea and zebrafish were used. Water fleas (Daphna magna) stand for the primary consumer. They are invertebrates living in small bodies of water. They are sensitive animals to various therapeutical classes of pharmaceuticals [11], and are good model organisms in ecotoxicology studies. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) stand for the secondary consumer. They are significant and widely used vertebrate model organisms in scientific research, which have achieved advances in the fields of developmental biology, toxicology, and environmental sciences [12].

Metabolomics comprehensively assesses biological responses by identifying changes in endogenous metabolites. Metabolic perturbation is the first response to a stressful environment. It can be detected following physical or chemical exposure, even though there is no mortality or observable morphological change. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has been recognized in the metabolomics community as a useful method for untargeted and targeted metabolite analysis. It has the advantages of being nondestructive, nonbiased, easily quantifiable, requires little or no chromatographic separation, sample treatment, or chemical derivatization, and it permits the routine identification of novel compounds [13]. High resolution magic angle spinning (HRMAS) NMR has the additional benefit of analyzing nonliquid samples with the particular magic angle to neglect “solid effects” [14]. D. magna are small, and the number of individuals required for liquid NMR was three times more than that of HRMAS NMR, but the signal intensities of metabolites in liquid NMR were lower than HRMAS NMR [15]. Therefore, we used HRMAS NMR for metabolic profiling of D. magna in this study. This study was conducted under the assumption that secondary consumers would be influenced by both the environment and primary consumers (food). Therefore, we simulated simple aquatic food chain conditions and used NMR-based metabolomics to identify metabolic changes induced by DCF exposure.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

Diclofenac (CAS: 15307-86-5, ≥ 98%) was obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd (JAPAN). Dimethyl sulfoxide (CAS: 67-68-5, ReagentPlus, ≥ 99.5%), methanol (CAS: 67-56-1, for HPLC, ≥ 99.9%), chloroform (CAS: 67-66-3, for HPLC, ≥ 99.8%), 3-(Trimethylsilyl) propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid sodium salt -(TSP-d4, CAS: 24493-21-8, 98 atom% D), and dimethyl sulfoxide (CAS: 67-68-5, ≥ 99.9%) were purchased from SIGMA-ALDRICH (USA). Deuterium oxide (CAS: 7789-20-0, 99.90% D) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (USA), and Water (CAS:7732-18-5, HPLC) was from J.T.Baker.

Test media

Both experiments of D. magna and zebrafish were in an environmental DCF concentration of 15 µg/L. The stock solution was prepared with a concentration of 1.5 mg/mL diclofenac in DMSO. It was diluted to 15 µg/L diclofenac in water and culture media to conduct experiments. Moreover, the stock solution was kept in a light-proof reagent cabinet at room temperature. The concentration of DMSO was 0.001% in all experiments. A former study showed that 0.001% of DMSO has little effect on D. magna and zebrafish which would not impact the experiment result [16].

Test organisms and experiment design

D. magna were raised for generations in our laboratory and followed the standard methods for breeding D. magna [17]. Briefly, D. magna were maintained in glass beakers filled with cultural media. We changed the culture media and fed them algae, and yeast, cerophyll, trout chow (YCT) regularly. The temperature was kept at 20 ± 1 ℃, and the light/dark period was set at 16/8 h with the light intensity of about 800 lx.

The experiment started with 24 to 48 h old D. magna. They were divided into two groups of 100 each, DCF-exposed group (DCF group) and the control group (CON group). DCF group were exposed to 15 µg/L of DCF for five days. After exposure, each D. magna were rinsed three times with distilled water to remove the surface water. Then, they were collected in a conical tube, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C before feeding to fish and NMR analysis.

Wild-type male zebrafish were purchased from a local aquarium (Green Fish, Korea), gender was distinguished by appearance. Fish were acclimated to the laboratory environment for two weeks in a 25 L glass tank and the light/dark period was set at a ratio of 14/10 h, and the water temperature was 27 ± 1 ℃. Fish were randomly divided into three groups for the experiment. Each group has five fish with 3 L test media in a glass tank, and each fish had about 30 thawed D. magna per day.

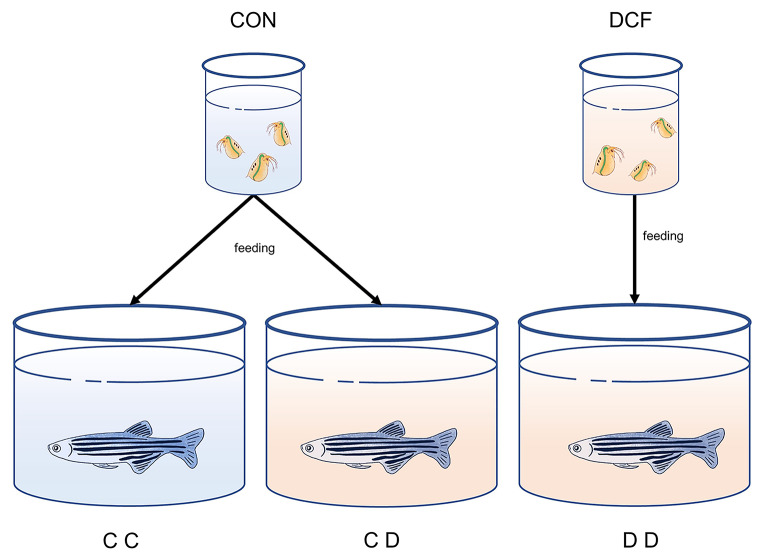

Control zebrafish were fed non-exposed D. magna (CC group). Exposed zebrafish were divided into two groups; one group was fed diclofenac-exposed D. magna (DD group), and the other was fed non-exposed D. magna (CD group). The schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 1. In this study, we consider the DD group is more similar to the natural environmental situation as an ecological mimic system group. CD group is a laboratory condition group, similar to many other experiments, representing the only exposed zebrafish to DCF solution.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of experimental groups. The blue color of water means non-exposed, and the orange means diclofenac exposure

NMR analysis

HRMAS NMR analysis of D. magna

Sixteen D. magna were put into a nanotube directly (Agilent Sample Tube, 4 mm) with 28 µL deuterium oxide buffer (pH:7.4) containing 2 mM of 3-(Trimethylsilyl) propionic-2,2,3,3,d4 acid sodium salt (TSP-d4) as a reference. The Agilent 600 MHz 1 H HRMAS NMR (Aglilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to obtain spectra. The Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence with presaturation of water resonance was used to offset the macromolecular substances’ signal and water peak. The spectra were acquired with 1.5 s relaxation delay and 3 s acquisition time at 298 K. A total of 128 scans were acquired for each sample.

Liquid NMR analysis of zebrafish

After the exposure of the zebrafish, they were transferred into fresh water to remove the surface chemical residual for 1 h. They were collected in 2 ml e-tubes, flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen, and freeze-dried for 24 h. After the lyophilization, samples were homogenized, and the water-soluble layer was extracted. The extraction was referred to as Bligh and Dyer’s method [18] and it was optimized in this experiment. 2 ml water-soluble layer was collected in a 15ml tube, froze with liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized again. The residue was resolved in 600 µL deuterium oxide buffer (pH 7.4) before being tested. The spectra were acquired using 600 MHz NMR and CPMG pulse with 1.5 s relaxation delay, 3 s acquisition time at 298 K. A total of 128 scans were acquired for each sample.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Metabolic profiling was performed by Chenomx NMR Suite7.1 software (Chenomx Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada) according to the 600 MHz human metabolome database (HMDB) library. The reference compound for chemical shift was TSP-d4 peak at 0.0 ppm and metabolite concentrations were automatically calculated from TSP-d4 peak integration. A total normalization was performed before concentration analysis.

For multivariate statistical analysis, we used the web-based software MetaboAnalyst 5.0 with auto-scaling and without data transformation. The score plot of principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal projections to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) model was performed to observe the differences between groups. The apparent advantage of OPLS-DA is that a single component is employed as a class predictor, while the remaining components describe variance orthogonal to the initial predictive component [19]. Metabolites with VIP score of 1.0 or higher were considered significant. A student’s t-test was used to distinguish the significant metabolites in the comparison between groups. Metabolites with a p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

There was no mortality or observable morphological deformities in D. magna and zebrafish during the exposure period, which indicates the tested medications are not endanger the organisms’ existence at the concentration levels (15 µg/L) examined.

Analysis results of D. magna

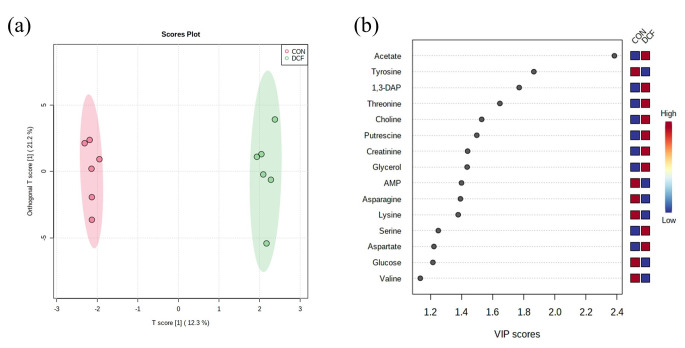

A total of 41 metabolites were identified and quantified in D. magna. The score plot of the OPLS-DA model between the control (CON) and the DCF exposed group (DCF) showed clear separation (R2X = 0.123, R2Y = 0.84, and Q2 = 0.421), which means the two groups have differences in metabolic profiling (Fig. 2a). Metabolites with VIP > 1.0 are shown in Fig. 2b. Among them, the concentration of 1,3-diaminopropane and putrescine were significantly increased, and threonine was significantly decreased in DCF compared to CON. (student’s t-test, p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Multivariate statistical analysis of D. magna metabolite concentrations. OPLS-DA score plots (a) and VIP plot (b) (CON, control; DCF, DCF exposed group)

Analysis results of zebrafish

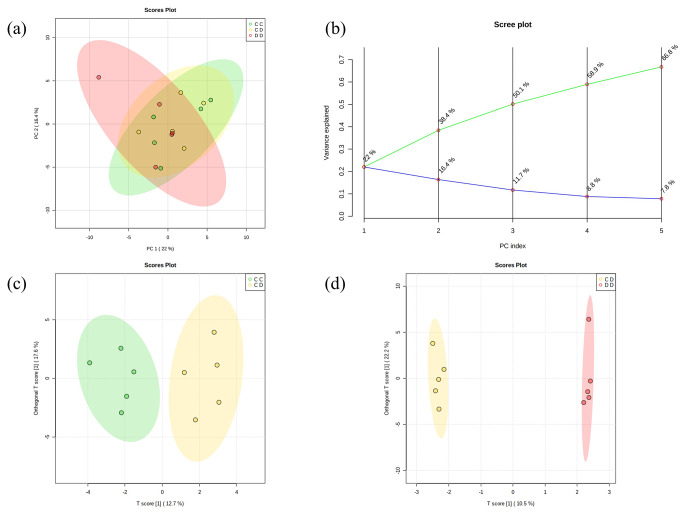

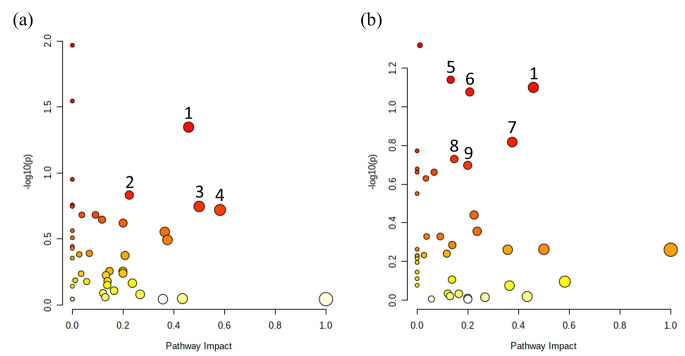

A total of 58 metabolites were identified in zebrafish. First, PCA was performed to show the metabolic trends in three groups (Fig. 3a and 3b). Then, OPLS-DA was performed to focus on group separations and identified significant metabolites. In the comparison of the CC and the CD groups, the OPLS-DA score plot showed clear separations (Fig. 3c, R2X = 0.127, R2Y = 0.76, and Q2 = -0.021), and there were 20 metabolites with VIP scores higher than 1.0 (Table 1) The concentration of alanine, and niacinamide were significantly upregulated, and the concentration of NAD + and pantothenate were significantly decreased (p < 0.05). The OPLS-DA score plot between the CD and the DD groups also showed clear separations (Fig. 3d, R2X = 0.105, R2Y = 0.655, and Q2 = -0.059), and 21 metabolites were identified by VIP score (Table 1). It showed significant upregulations in guanosine and UDP-glucose, which were not identified in CC-CD comparison. The pathway analysis was conducted with normalized concentrations of metabolites by the web-based software MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (Fig. 4). Only nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism was matched in both CC-CD and CD-DD comparisons. Histidine metabolism, D-Glutamine, D-glutamate metabolism, alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism were matched in the CC-CD comparison. Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, ascorbate and alternate metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and purine metabolism were matched in the CD-DD comparison. (Impact > 0.1, p < 0.2).

Fig. 3.

Multivariate statistical analysis of zebrafish metabolite concentrations. PCA score plot (a) and its variance explanation (b) of three groups. OPLS-DA score plot between CC and CD groups (c) and between CD and-DD (d)

Table 1.

The VIP score list of which metabolite’s VIP value more than 1.0 that affect the separation between CC-CD and CD-DD in OPLS-DA score scatter plot for metabolites with their fold changes and the result of student’s t-test. (“*”, p < 0.05; “**”, p < 0.01)

| CC-CD | VIP | Fold Change % | p-Value | CD-DD | VIP | Fold Change % | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 2.2263 | 26.39 | ** | Guanosine | 2.0095 | 60.27 | * |

| Niacinamide | 1.8835 | 46.3 | * | UDP-glucose | 1.9196 | 77.94 | * |

| IMP | 1.7845 | 26.16 | Pantothenate | 1.8918 | 29.79 | * | |

| Valine | 1.7446 | 17.46 | 2-Aminobutyrate | 1.8576 | -21.11 | * | |

| myo-Inositol | 1.7288 | -53.21 | Niacinamide | 1.8252 | -24.71 | * | |

| NAD+ | 1.6887 | -38.21 | * | UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine | 1.7245 | 8.21 | * |

| Pantothenate | 1.6152 | -23.14 | * | Glutarate | 1.6388 | 15.14 | |

| UDP-glucuronate | 1.6042 | -19.04 | NAD+ | 1.5329 | 63.01 | ||

| Aspartate | 1.5831 | -10.78 | Alanine | 1.4987 | -9.54 | ||

| Sarcosine | 1.5207 | 32.73 | Aspartate | 1.3908 | 17.09 | ||

| Isoleucine | 1.5064 | 12.81 | 3-Hydroxyisobutyrate | 1.3728 | 35.18 | ||

| 2-Aminobutyrate | 1.3821 | 17.77 | IMP | 1.3609 | -22.84 | ||

| AMP | 1.3054 | 7.81 | GTP | 1.2742 | 10.1 | ||

| Glutamate | 1.2894 | 19.65 | Glutamine | 1.1767 | -14.47 | ||

| Taurine | 1.2648 | -5.8 | Histidine | 1.1704 | -16.99 | ||

| Glutathione | 1.1865 | -17.65 | Methionine | 1.1512 | 17.32 | ||

| O-Acetylcarnitine | 1.1615 | 27.26 | Isopropanol | 1.0643 | 15.52 | ||

| GTP | 1.1568 | 8.09 | UDP-glucuronate | 1.0402 | 28.24 | ||

| 2-Hydroxyisobutyrate | 1.1015 | -10.64 | Glycine | 1.0279 | 18.37 | ||

| Glutamine | 1.059 | 17.71 | Phenylalanine | 1.0163 | 15.15 | ||

| Succinate | 1.0511 | 20.88 | Isobutyrate | 1.0124 | 29.28 | ||

| Inosine | 1.0013 | 38.27 |

Fig. 4.

(a) Overview of pathway analysis between CC-CD, (b) Overview of pathway analysis between CD-DD. (1: Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism; 2: Histidine metabolism; 3: D-Glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism; 4: Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism; 5: Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism; 6: Pentose and glucuronate interconversions; 7: Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism; 8: Cysteine and methionine metabolism; 9: Purine metabolism)

Discussion

DCF is an emergent environmental pollutant due to its widespread presence in freshwater ecosystems. It would cause a serious threat to aquatic animals, plants, and mammals, and it can affect the development, growth, and immune system [20]. Sub-chronic exposure to environmental concentrations of diclofenac can interfere with the biochemical functions of fish and lead to tissue damage [21]. A recent study on fish confirmed that environmentally relevant concentrations of DCF alone or in combination with caffeine induce oxidative stress, and is neurotoxic for fish [22]. Marion Letzel’s group suggested, measured and predicted DCF concentrations, especially in highly polluted water courses, may have negative impacts and perhaps pose a threat to the health of the affected fish populations [23]. A study found that high concentration of DCF (25 mg/L) decreased the reproduction in D. magna, and decrease the trend in the hatching success and delay hatching time in fish (0.001–10 mg/L of DCF) [24]. Therefore, it is necessary to study the effect of DCF at the environmental concentration.

Previous studies suggested that D. magna are subject to oxidative stress in 9.7 mg/L of diclofenac [25]. In this result, 1,3-diaminopropane (+ 14.50%, p < 0.05) and putrescine (+ 14.14%, p < 0.05) were raised in the DCF group compared to CON group, which closely relate to oxidative stress. Putrescine up-regulates benefit to defense against oxidative stress [26]. It oxidizes to other polyamines such as spermidine and spermine [27], which produce 1,3-diaminopropane [28]. From putrescine to 1,3-diaminoproane, the polyamines are included in microalgae, a nutrient source of D. magna, and protect the organism against several environmental stress [28, 29]. In addition, the concentration of threonine (+ 75.68%, p < 0.05) decreased in DCF-exposed D. magna compared to the control. Threonine can promote cell immune defense function, and optimum threonine improves antioxidant and immune capacity [30]. Therefore, we suggest that D. magna was subject to oxidative stress while metabolizing DCF at an environmental concentration.

Zebrafish showed metabolic perturbation even under an environmental concentration exposure experiment in the CD group (fed CON D. magna to exposed zebrafish) compared to the CC group (fed CON D. magna to non-exposed zebrafish). A previous study has suggested that fish exposure to 15 µg/L DCF significantly increased energy expenditure in fish [31]. In this experiment, DCF exposure significantly changed alanine (+ 26.39%, p < 0.01) in zebrafish. Alanine is essential for maintaining glucose and nitrogen levels and supplying energy to the body. It also protects cells from damage during high-intensity aerobic exercise [32]. In addition, we discovered that metabolites related to energy metabolism were changed. Fumarate (+ 7.28%) and citrate (− 5.84%) which are TCA cycle intermediates, fluctuated, although the data is insignificant. In the TCA cycle, GDP and NAD + convert to GTP and NADH. The concentrations of NAD+ (− 38.21%, p < 0.05) were decreased and those of GTP (+ 8.09%, VIP > 1) were increased in DCF-exposed fish compared to control. Furthermore, the increases in alanine, valine, isoleucine, glutamate, and glutamine, which could supply the intermediates in the TCA cycle were observed. These results indicated that the TCA cycle had been activated, and energy demand was increased in the CD group by the exposure to DCF compared to the CC group.

Niacinamide (+ 46.30%, p < 0.05) and NAD+ (− 38.21%, p < 0.05) are related to nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism. Nicotinic acid, also known as vitamin B3, can be converted to nicotinamide, which is the main precursor of NAD + by transamination [33, 34]. An increase in the concentration of niacinamide and a decrease in the concentration of NAD + indicate changes in nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, which is closely related to the anti-inflammatory effect [35]. Research has suggested that elevated concentrations of NAD + result in the inhibition of releasing inflammatory factors to achieve the effect of anti-inflammation [35]. However, the concentration of NAD + was decreased in the CD group. Therefore, we can only infer that it has an impact in the anti-inflammatory effect in this condition, but the specific effect needs to be explored.

The DD group (fed DCF D. magna to diclofenac-exposed zebrafish) as an ecological mimic system group added a food element compared to the CD group. Marcela’s group did a 14-day exposure experiment with DCF in 0.4 µg/L, which revealed a neurotoxic effect of DCF through the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity in fish muscle [22]. We ascertain that food plays an important role in the experiment of the secondary consumer. In our study, the concentration of guanosine (+ 60.27%, p < 0.05) was increased significantly in DD compared to CD, which was not changed in CC-CD comparison. Guanosine functions as an antioxidant and promotes glutamate absorption by astrocytes, providing neuroprotection against glutamatergic excitotoxicity [36]. It is produced in the brain under normal and pathological situations, lowering neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and excitotoxicity while also having trophic effects in neuronal and glial cells [37]. The chief metabolic product of guanosine is guanine [38], and guanine-based purines release increases under certain harmful conditions [39]. In addition, UDP-glucose (+ 77.94%, p < 0.05) increase is known to provide a substrate for the enzyme UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase, which is used to mitigate ceramide toxicity normally [40]. This indicates that the neuroprotective effect was conducted by the food that zebrafish intake. It is believed that the primary consumer ingested by zebrafish as food cause neurotoxicity in zebrafish. DCF catabolism products in aquatic creatures are 4’-hydroxydiclofenac (4’OH-DCF), 5’-hydroxydiclofenac (5’OH-DCF), 4′-hydroxy diclofenac dehydrate (4′-OHDD), diclofenac acyl glucuronide (DicGluA) and diclofenac glutathione thioester (DicSG), etc. [41–43]. Among them, 4’OH-DCF and 5’OH-DCF are more toxic to aquatic organisms than DCF, and more prone to bioaccumulation and increase ROS formation [43, 44]. In addition, DCF can also transform into several oxidation products and conjugates in aquatic invertebrates, such as diclofenac taurine conjugate or diclofenac methyl ester, which has more than a hundred times acute toxicity compared to DCF [45]. Therefore, it is believed that incompletely degraded DCF and its derivatives accumulated in D. magna, resulting in changes in the zebrafish metabolisms when D. magna is ingested by zebrafish as food.

In addition, a recent study suggested that purine metabolism is an essential response to oxidative stress [46]. The lack of ascorbate causes a compensatory increase in uric acid as an antioxidant. The purine metabolism would be activated to produce uric acid, which has a powerful antioxidant effect [47]. On the other hand, methionine is a constituent of glutathione, which acts as an antioxidant. Methionine can also activate endogenous antioxidant enzymes. An increase in methionine can increase the cellular tolerance to the oxidizing agent and reduces oxidative stress [48]. The concentration of glutathione decreased, and methionine increased. It can refer to the consumption of glutathione and the activation of methionine metabolism. The concentration of histidine showed a 17% decrease in the DD group. Histidine and other imidazole compounds have anti-oxidation and anti-inflammatory properties. They scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by cells during acute inflammatory response [49]. It also has been reported that histidine levels are negatively associated with inflammation and oxidative stress [50]. These changes indicate that zebrafish suffered from oxidative stress in the DD group compared to the CD group.

In conclusion, this study revealed that diclofenac in environmental concentration could cause metabolic perturbation in D. magna and zebrafish. We used two aquatic organisms to conduct a simple food chain simulation, including exposure experiments to single species and the overall aquatic environment. The statistical analysis showed that D. magna were subjected to oxidative stress while metabolizing diclofenac. For zebrafish, energy metabolism and nicotinate metabolism were affected by exposure. Adding the effects of the food to the premise of water environment exposure had other influences on secondary consumers. The intake of the exposed D. magna caused neurotoxicity and oxidative stress. It indicates that exposed D. magna (primary consumers) occupies a position that cannot be underestimated in the entire food chain. In this experiment, the exposure was carried out for only five days under the environmental concentration. There were unexpected changes in such a short period, and whether long-term exposure will have a more significant impact remains to be investigated.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection was performed by Youzhen Li, analysis were performed by Youzhen Li, Seonghye Kim and Sujin Lee. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Suhkmann Kim and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Grant number NRF-2020R1I1A2075016).

Declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in the current work were approved with approval number PNU-2019-2473 and were following the ethical standards of the Department of Chemistry, Pusan National University, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (PNU-IACUC).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nkwunonwo UC, Odika PO, Onyia NI. A review of the Health Implications of Heavy Metals in Food Chain in Nigeria. Sci World J. 2020;2020:6594109. doi: 10.1155/2020/6594109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang W, Gao H, Jin S, Li R, Na G. The ecotoxicological effects of microplastics on aquatic food web, from primary producer to human: a review. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;173:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.01.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chae Y, An YJ. Toxicity and transfer of polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanowires in an aquatic food chain consisting of algae, water fleas, and zebrafish. Aquat Toxicol. 2016;173:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Y, Liu Y, Chen Y, Zhang W, Zhao J, He S, et al. A review: Research progress on microplastic pollutants in aquatic environments. Sci Total Environ. 2021;766:142572. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott PN (2010) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Drugs in Sport. 317

- 6.Fatta-Kassinos D, Hapeshi E, Achilleos A, Meric S, Gros M, Petrovic M, et al. Existence of Pharmaceutical Compounds in Tertiary treated Urban Wastewater that is utilized for reuse applications. Water Resour Manage. 2011;25(4):1183–1193. doi: 10.1007/s11269-010-9646-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fent K, Weston AA, Caminada D (2006) Ecotoxicology of human pharmaceuticals. Aquat Toxicol 78:207. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bonnefille B, Gomez E, Courant F, Escande A, Fenet H. Diclofenac in the marine environment: a review of its occurrence and effects. Mar Pollut Bull. 2018;131(Pt A):496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jux U, Baginski RM, Arnold HG, Kronke M, Seng PN. Detection of pharmaceutical contaminations of river, pond, and tap water from Cologne (Germany) and surroundings. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2002;205(5):393–398. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanif H, Waseem A, Kali S, Qureshi NA, Majid M, Iqbal M, et al. Environmental risk assessment of diclofenac residues in surface waters and wastewater: a hidden global threat to aquatic ecosystem. Environ Monit Assess. 2020;192(4):204. doi: 10.1007/s10661-020-8151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tkaczyk A, Bownik A, Dudka J, Kowal K, Ślaska B. Daphnia magna model in the toxicity assessment of pharmaceuticals: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2021;763:143038. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roper C, Tanguay RL (2018) Chapter 12 - Zebrafish as a model for developmental biology and toxicology. In: Slikker W, Paule MG, Wang C (eds) Handbook of developmental neurotoxicology, 2nd edn. Academic Press;, pp 143–151. 10.1016/B978-0-12-809405-1.00012-2

- 13.Emwas AH, Roy R, McKay RT, Tenori L, Saccenti E, Gowda GAN et al (2019) NMR spectroscopy for metabolomics research. Metabolites 9:123. 10.3390/metabo9070123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Gowda GN, Raftery D (2019) NMR-Based metabolomics: methods and protocols. Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9690-2

- 15.Kim S, Lee S, Lee W, Lee Y, Choi J, Lee H, et al. Comparison of metabolic profiling of Daphnia magna between HR-MAS NMR and solution NMR techniques. J Korean Magn Reson Soc. 2021;25(2):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.David RM, Jones HS, Panter GH, Winter MJ, Hutchinson TH, Chipman JK. Interference with xenobiotic metabolic activity by the commonly used vehicle solvents dimethylsulfoxide and methanol in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae but not Daphnia magna. Chemosphere. 2012;88(8):912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber CI (Ed.) (1991) Methods for measuring the acute toxicity of effluents and receiving waters to freshwater and marine organisms (p. 197).

- 18.Wu H, Southam AD, Hines A, Viant MR. High-throughput tissue extraction protocol for NMR-and MS-based metabolomics. Anal Biochem. 2008;372(2):204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westerhuis JA, van Velzen EJ, Hoefsloot HC, Smilde AK. Multivariate paired data analysis: multilevel PLSDA versus OPLSDA. Metabolomics. 2010;6(1):119–128. doi: 10.1007/s11306-009-0185-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sathishkumar P, Meena RAA, Palanisami T, Ashokkumar V, Palvannan T, Gu FL. Occurrence, interactive effects and ecological risk of diclofenac in environmental compartments and biota - a review. Sci Total Environ. 2020;698:134057. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehinto AC, Hill EM, Tyler CR. Uptake and Biological Effects of environmentally relevant concentrations of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory Pharmaceutical Diclofenac in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(6):2176–2182. doi: 10.1021/es903702m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muñoz-Peñuela M, Moreira RG, Gomes ADO, Tolussi CE, Branco GS, Pinheiro JPS, et al. Neurotoxic, biotransformation, oxidative stress and genotoxic effects in Astyanax altiparanae (Teleostei, Characiformes) males exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of diclofenac and/or caffeine. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2022;91:103821. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2022.103821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letzel M, Metzner G, Letzel T. Exposure assessment of the pharmaceutical diclofenac based on long-term measurements of the aquatic input. Environ Int. 2009;35(2):363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Ji K, Lim Kho Y, Kim P, Choi K. Chronic exposure to diclofenac on two freshwater cladocerans and japanese medaka. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2011;74(5):1216–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomez-Olivan LM, Galar-Martinez M, Garcia-Medina S, Valdes-Alanis A, Islas-Flores H, Neri-Cruz N. Genotoxic response and oxidative stress induced by diclofenac, ibuprofen and naproxen in Daphnia magna. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2014;37(4):391–399. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2013.870191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tkachenko A, Nesterova L, Pshenichnov M. The role of the natural polyamine putrescine in defense against oxidative stress in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 2001;176(1):155–157. doi: 10.1007/s002030100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenis YY, Elmetwally MA, Maldonado-Estrada JG, Bazer FW. Physiological importance of polyamines. Zygote. 2017;25(3):244–255. doi: 10.1017/S0967199417000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin H-Y, Lin H-J. Polyamines in Microalgae: something borrowed, something New. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(1):1. doi: 10.3390/md17010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller-Fleming L, Olin-Sandoval V, Campbell K, Ralser M. Remaining Mysteries of Molecular Biology: the role of polyamines in the cell. J Mol Biol. 2015;427(21):3389–3406. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habte-Tsion H-M, Ren M, Liu B, Ge X, Xie J, Chen R. Threonine modulates immune response, antioxidant status and gene expressions of antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant-immune-cytokine-related signaling molecules in juvenile blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;51:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duarte IA, Reis-Santos P, Novais SC, Rato LD, Lemos MFL, Freitas A, et al. Depressed, hypertense and sore: long-term effects of fluoxetine, propranolol and diclofenac exposure in a top predator fish. Sci Total Environ. 2020;712:136564. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarojnalini C, Hei A (2019) Fish as an important functional food for quality life. U: Functional Foods, (Lagouri, V, Ured) 77–97.

- 33.Penberthy WT. Editorial [hot topic: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biology and disease (executive editor: w. todd penberthy)] Curr Pharm Design. 2009;15(1):1–2. doi: 10.2174/138161209787185779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.James EL, Lane JA, Michalek RD, Karoly ED, Parkinson EK. Replicatively senescent human fibroblasts reveal a distinct intracellular metabolic profile with alterations in NAD + and nicotinamide metabolism. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38489. doi: 10.1038/srep38489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma Y, Bao Y, Wang S, Li T, Chang X, Yang G, et al. Anti-Inflammation Effects and potential mechanism of saikosaponins by regulating Nicotinate and Nicotinamide Metabolism and Arachidonic Acid Metabolism. Inflammation. 2016;39(4):1453–1461. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cittolin-Santos GF, de Assis AM, Guazzelli PA, Paniz LG, da Silva JS, Calcagnotto ME, et al. Guanosine exerts neuroprotective effect in an experimental model of Acute Ammonia Intoxication. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(5):3137–3148. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9892-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bettio LE, Gil-Mohapel J, Rodrigues ALS. Guanosine and its role in neuropathologies. Purinergic Signalling. 2016;12(3):411–426. doi: 10.1007/s11302-016-9509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang S, Fischione G, Giuliani P, Romano S, Caciagli F, Di Iorio P. Metabolism and distribution of guanosine given intraperitoneally: implications for spinal cord injury. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2008;27(6):673–680. doi: 10.1080/15257770802143962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanznaster D, Dal-Cim T, Piermartiri TC, Tasca CI. Guanosine: a neuromodulator with therapeutic potential in Brain Disorders. Aging Dis. 2016;7(5):657–679. doi: 10.14336/AD.2016.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zimmer BM, Barycki JJ, Simpson MA. Integration of Sugar Metabolism and Proteoglycan Synthesis by UDP-glucose dehydrogenase. J Histochem Cytochem. 2021;69(1):13–23. doi: 10.1369/0022155420947500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swiacka K, Szaniawska A, Caban M. Evaluation of bioconcentration and metabolism of diclofenac in mussels Mytilus trossulus - laboratory study. Mar Pollut Bull. 2019;141:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Syed M, Skonberg C, Hansen SH. Mitochondrial toxicity of diclofenac and its metabolites via inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation (ATP synthesis) in rat liver mitochondria: possible role in drug induced liver injury (DILI) Toxicol In Vitro. 2016;31:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oviedo-Gómez DGC, Galar-Martínez M, García-Medina S, Razo-Estrada C, Gómez-Oliván LM. Diclofenac-enriched artificial sediment induces oxidative stress in Hyalella azteca. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;29(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stulten D, Zuhlke S, Lamshoft M, Spiteller M. Occurrence of diclofenac and selected metabolites in sewage effluents. Sci Total Environ. 2008;405(1–3):310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu Q, Fedrizzi D, Kosfeld V, Schlechtriem C, Ganz V, Derrer S, et al. Biotransformation Changes Bioaccumulation and Toxicity of Diclofenac in aquatic organisms. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(7):4400–4408. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b07127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian R, Yang C, Chai SM, Guo H, Seim I, Yang G. Evolutionary impacts of purine metabolism genes on mammalian oxidative stress adaptation. Zool Res. 2022;43(2):241–254. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2021.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furuhashi M. New insights into purine metabolism in metabolic diseases: role of xanthine oxidoreductase activity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;319(5):E827–E34. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00378.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez Y, Li X, Liu G, Bin P, Yan W, Mas D, et al. The role of methionine on metabolism, oxidative stress, and diseases. Amino Acids. 2017;49(12):2091–2098. doi: 10.1007/s00726-017-2494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peterson JW, Boldogh I, Popov VL, Saini SS, Chopra AK. Anti-inflammatory and antisecretory potential of histidine in Salmonella-challenged mouse small intestine. Lab Invest. 1998;78(5):523–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feng RN, Niu YC, Sun XW, Li Q, Zhao C, Wang C, et al. Histidine supplementation improves insulin resistance through suppressed inflammation in obese women with the metabolic syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2013;56(5):985–994. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2839-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]