Abstract

Identifying the maintaining contingencies of problem behavior can lead to effective treatment that reduces the occurrence of problem behavior and increases the potential for the occurrence of alternative behaviors. Many studies use descriptive assessments, but results vary in effectiveness and validity. Comparative research further supports the superior utility of analog functional analyses over descriptive assessments, but clinicians continue to report the consistent use of descriptive assessments in practice. Direct training on the recording of descriptive assessments as well as the process for interpreting the results are limited. The absence of research-based guidance leaves clinicians to interpret the results as they see fit rather than following best practice guidelines for this critical activity. This study examined the potential impact of direct training on several components of descriptive assessment: the recording of narrative antecedent-behavior-consequence data, interpretation of the data, and the selection of a function-based treatment. Implications for training and practice are reviewed.

Keywords: staff training, descriptive assessment, functional analysis, ABC data

When attempting to implement an appropriate and effective function-based intervention, one must first identify the maintaining variable of the individual’s problem behavior, which is usually and best done through a functional behavior assessment (Hanley, 2012; Iwata et al., 2000). The process typically involves the completion of indirect assessments (e.g., rating scales, interviews, and questionnaires), descriptive assessments (e.g., narrative or checklist data collection of antecedent-behavior-consequence and scatterplots), and a functional analysis (Hanley, 2012). According to the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts, conducting assessments based on scientific evidence is essential before designing a behavior-change program (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2020). In addition, the law requires public schools to implement functional behavior assessments for student cases where the educational placement is due to problem behaviors and for all students with an individualized education plan (IDEA; P.L. 101-476).

Clinicians and researchers have used experimental functional analyses for many years and have demonstrated their accuracy in identifying functions of problem behaviors that then lead to the implementation of a function-based treatment (Hanley et al., 2003). For this reason, the experimental functional analysis has become the gold standard for function identification in the field (Madsen et al., 2016; Oliver et al., 2015; Schlinger & Normand, 2013). However, in a survey completed by behavior analysts, only 36% reported using experimental functional analyses to help determine the function of behavior (Oliver et al., 2015). The most commonly reported assessment method was descriptive assessments, with 94% of respondents stating they “almost always” or “always” implement them (Oliver et al., 2015).

The most frequently used descriptive assessment methodology includes the antecedent-behavior-consequence (ABC) procedure (Sasso et al., 1992). These assessments involve the creation of an operational definition of the problem behavior and environmental variables, and then the coding of the occurrences of each (Bijou et al., 1968). One method of the ABC procedure includes narrative data collection where the clinician writes a brief description about what immediately occurred before a behavior, the behavior that occurred, and what immediately occurred after the behavior (Iwata et al., 2000). Another method of the ABC procedure includes structured data collection where a clinician completes a form of predetermined antecedents and consequences by selecting those that occurred before and after the identified problem behavior. Following the direct observation for both methods, the assessor quantifies and summarizes the data to determine correlations between the problem behavior and environmental variables.

Researchers have conducted validity studies comparing descriptive assessments to experimental functional analyses that suggest limited validity of descriptive assessments (Camp et al., 2009; Lerman & Iwata, 1993; Mace & Lalli, 1991; St. Peter et al., 2005; Thompson & Iwata, 2007). Intermittent reinforcement in the natural environment may lead to some of the inaccuracies of descriptive assessments due to mistakenly identifying some consequences as possible reinforcers of the problem behavior (Camp et al., 2009). Intermittent reinforcement delivery may also result in low occurrences of the maintaining consequence observed during the observation period, which might skew the data collected in descriptive assessments. Results can also be skewed to show a positive correlation with consequent events that are highly probable, regardless of the function of the problem behavior (St. Peter et al., 2005; Thompson & Iwata, 2001).

Descriptive assessments continue to be used across the field, either alone or in combination with an experimental functional analysis, despite the validity concerns identified in research (Mayer & DiGennaro Reed, 2013; Oliver et al., 2015; Roscoe et al., 2015). Reasons for the continuation of use may include (1) not being able to directly manipulate the environmental variables to further assess the target behavior (Lerman & Iwata, 1993); (2) reduced risk of establishing new behavioral functions during assessment (Lerman & Iwata, 1993; Mace & Lalli, 1991); (3) shorter experimental sessions when used in combination (Lerman & Iwata, 1993); and (4) the ability to identify naturally occurring contingencies that may be missed in the experimental analysis (Lerman & Iwata, 1993; Mace & Lalli, 1991; Sasso et al., 1992; Thompson & Iwata, 2001).

Descriptive assessments are an alternative to experimental functional analyses that require individuals to be specifically trained in their implementation as that expertise may not be available in the setting (Hanley, 2012). Often there are limited resources even for behavior analysts to personally conduct the descriptive assessment, leaving it to the direct-care staff (Madsen et al., 2016). The direct-care staff implementing the descriptive assessment typically do not have an adequate understanding of behavior and the complexity of variables that may maintain the behavior (Madsen et al., 2016). In general, without proper training the direct-care staff are not well-prepared for the extensive effort required to implement the descriptive assessment concurrently with regularly occurring activities, which lowers the reliability and validity of the assessment data (Lerman & Iwata, 1993). Furthermore, descriptive assessments require highly skilled individuals to accurately interpret the data to ensure the interpretations remain objective rather than subjective (Lerman & Iwata, 1993).

Training individuals to complete experimental functional analyses with success has been well-studied in the field (Hagopian et al., 1997; Hanley, 2012: Iwata et al., 2000). Researchers and clinicians have used a variety of training methods to teach individuals how to conduct assessment sessions (Iwata et al., 2000) and interpret these results for experimental analyses (Hagopian et al., 1997). Some of the training components include written and verbal instructions (Hagopian et al., 1997; Iwata et al., 2000), video or live models (Hagopian et al., 1997; Iwata et al., 2000), rehearsal (Hagopian et al., 1997; Iwata et al., 2000), and performance feedback (Hagopian et al., 1997; Iwata et al., 2000).

Though researchers have used these procedures to successfully train the use of experimental functional analyses, researchers have not completely examined how to conduct and interpret descriptive assessments (Hanley, 2012; Madsen et al., 2016). Few researchers have conducted studies on training descriptive assessments but each of which only examined the data recording during descriptive assessments (Lerman et al., 2009; Luna et al., 2018; Mayer & DiGennaro Reed, 2013; Pence & St. Peter, 2018). Research on the interpretation of the data has demonstrated differing results based on the interpretation technique (St. Peter et al., 2005). If an increase in the amount and/or quality of training descriptive assessments occurred, the validity of descriptive assessments may increase.

Mayer and DiGennaro Reed (2013) implemented a training package to increase the accuracy1 of the direct-care staff’s data collection during a descriptive assessment. The training package consisted of written instructions for detailed completion of a narrative ABC form and feedback on performance. The researchers collected data on each aspect of the narrative ABC form. Participants scored the highest accuracy during baseline in the behavior domain of the form and low variable scores across participants for the antecedent and consequence domains. The training package resulted in increased identification of maintaining variables for all participants. A similar study conducted by Luna et al. (2018) implemented group training with verbal instruction and group feedback to improve the completion of narrative and structured ABC forms with video vignettes of behavioral episodes. All participants increased accuracy with identifying events depicted in video vignettes following training, most of which achieved mastery.

Pence and St. Peter (2018) further examined the training of teachers and a clinician enrolled in a verified course sequence in applied behavior analysis, to collect ABC data. In experiment 1, the researchers examined if the ability to identify maintaining variables would improve upon increased practice but low percent agreement remained across time. Experiment 2 applied a training package consisting of written instructions and a recorded lecture. Although the training increased participant identification and recording of maintaining variables using ABC data, limited experimental control precludes a conclusion regarding causation for the performance change.

Research has demonstrated the use of evidence-based training techniques to increase the agreement between observers recording data during descriptive assessments (Luna et al., 2018; Mayer & DiGennaro Reed, 2013; Pence & St. Peter, 2018). Another study demonstrated that didactic training strategies have not been effective to increase the validity of descriptive assessment among teachers (Ellingson et al., 2000). Research suggests that performance skills, such as recording and interpreting descriptive assessments to select a function-based treatment, requires competency-based training for skill mastery (Falender & Shafranske, 2012; Parsons et al., 2012). Competency-based training emphasizes the real-world demonstration of the skill to a predetermined criterion (Falender & Shafranske, 2012). Components of competency-based training consist of defining the skill to be trained, providing precise written descriptions of the skill, demonstrating the skill, practicing the skill, and providing feedback during practice (Parsons et al., 2012). Practicing the skill with feedback is recommended to be repeated until mastery of the skill is achieved (Parsons et al., 2012).

Research highlights the importance of feedback within training models and identifies an occasional need for additional feedback for participants to meet proficiency (Roscoe & Fisher, 2008). In a review of asynchronous training to teach behavioral assessments and interventions, Gerencser et al. (2020) found that several of the included studies required additional training and feedback for their participants to achieve their mastery criteria regardless of training methodology. Of the studies that provided additional training and feedback to participants, approximately 73% of the studies provided synchronous feedback.

Given the frequent use of descriptive assessments by clinicians, the inconsistent results they provide, the potential for misleading interpretations that follow from these data, and the minimal research on training the implementation and interpretation of descriptive assessments, further analysis needs to determine if training can improve the identification of maintaining variables. If the accuracy can be improved, descriptive assessments might serve as a useful alternative or ancillary data collection procedure. The purpose of the current investigation was to train graduate students in behavior analysis in three-component skills of descriptive assessments: identifying antecedents and consequences, interpreting descriptive assessments, and selecting a function-based intervention.

Methods

Participants, Setting, and Materials

Nine graduate students of applied behavior analysis participated in the study as a part of their required course. The researcher provided no additional compensation for participating in the study to participants as the material was required within their course; however, participants must achieve a passing grade for the course for graduation. Before the study, each participant consented to use their de-identified data for research and the IRB approved the study. Three participants identified as male and six identified as female. Six participants were between the ages of 20 and 29, two participants were between the ages of 30 and 39, and one was between the ages of 40 and 49. All participants had experience working with individuals with problem behavior. Their experience with applied behavior analysis in the workplace ranged from 0 to 7 years (M = 2.7); one participant (Evelina) reported experience with coursework on how to implement and interpret descriptive assessments. Four of the participants were registered behavior technicians (RBT; Addison, Callum, Shelby, and Danika).

The researcher conducted the study via the internet on the online course platform Canvas and synchronous sessions occurred via Zoom. The researcher instructed all participants to go to a distraction-free space during the training; however, the researcher could not directly monitor their compliance.

Materials for the study included access to the internet and platforms used, and training materials, such as handouts and copies of PowerPoint presentations (available per request to the first author). Before the study, the researcher created written instructions and video recorded lectures for each skill to be trained, which included definitions for the targeted task, a rationale for the skill to be demonstrated, and two examples for practice. From the Research Units in Behavioral Intervention (RUBI) Autism Network’s commercially available training (Bearss et al., 2018), the researcher selected 24 video scenarios for participants to score during each session (two per session). The video scenarios were a mean of approximately 30 s long (range: 9–43 s) and included one to two children and one to two adults per video. The scenarios each displayed one or more antecedents to problem behavior, the problem behavior, and one or more consequences to the problem behavior. For example, one scenario showed a mother reading at the table and a child coming into the room requesting a brownie. Upon requesting the brownie, the mother denied it and the child protested, by yelling and stomping his feet. The mother then told him he could have one brownie and gave him the brownie. The researcher presented these scenarios to participants along with worksheets that the researcher scored for accuracy. In addition, the researcher selected and modified four written scenarios for generalization probes from materials commercially available from The RUBI Autism Network (Bearss et al., 2018). Each written scenario was one paragraph in length and described a situation surrounding a problem behavior occurring in the home. The researcher created narrative and structured ABC worksheets for these videos, along with worksheets for analyzing and selecting the function-based interventions.

Response Definitions

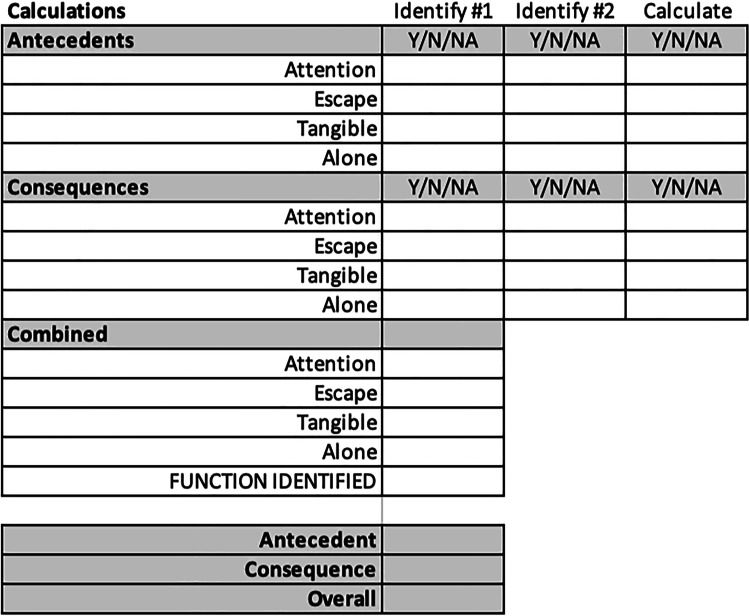

The researcher collected data on the accuracy of recording narrative ABC data, interpretation of the data, and selection of a function-based treatment using a rubric for each skill (Appendix B). The researcher scored the accuracy of recording the narrative ABC data using a rubric that specified all of the necessary components for data collection as 27 objective measures. The researcher noted an accurate response if the participant's recording on the worksheet matched the event occurrence on the video and an inaccurate response if the participant did not record an event that occurred in the video or recorded an event that did not occur. Interpretation of the data, using conditional probabilities, was scored using a rubric that included each aspect that encompassed the identification of the accurate function of each antecedent and consequence and the calculation of the conditional probabilities for each of the four functions. Instructions for calculating conditional probabilities used the method outlined in Lerman and Iwata (1993) for antecedents, consequences, and antecedents and consequences combined. The function with the highest conditional probability was the identified function. The researcher scored the response as an accurate response if the participant correctly calculated the conditional probability for that function. The researcher scored an inaccurate response if the participant did not complete a conditional probability for the function and variable or if the participant did not correctly calculate the conditional probability. The selection of the function-based treatment was scored as correct on the rubric if the participants identified: a target behavior and intervention for antecedent manipulation; a replacement behavior to increase; and the challenging target behavior to decrease. Though the researcher provided the participants with a target behavior to watch for in each scenario, all participants made errors identifying the challenging target behavior to decrease in multiple baseline sessions. Each aspect had to align with the accurate function of the behavior for the researcher to score as correct. In addition, participants needed to also identify an appropriate treatment for each of these elements, based on the accurate function. Each participant could identify different target behaviors and interventions as long as each aspect matched the accurate function. The researcher calculated the percent accuracy for each skill based on the corresponding scoring rubric by adding the number of items marked correct by the total number of items on the rubric and multiplying by 100.

Interobserver Agreement and Procedural Integrity

Secondary observers collected interobserver agreement (IOA) data by independently scoring 33% of sessions across phases. All secondary observers were doctoral students in applied behavior analysis. The second observer collected data via permanent records completed by the participants during each session. Secondary observers collected IOA data on percent accuracy as identified in each rubric for each targeted skill (Appendix B). Each skill noted on the rubric by the second observer was marked as an agreement or disagreement as compared with the primary researcher’s scores. IOA was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. Mean agreement across all participants was 91% (range: 81%–100%) for recording the data, 98% (range: 90%–100%) for interpreting the data, and 90% (range: 83%–100%) for selecting a function-based treatment.

Secondary observers also completed procedural integrity checks. A doctoral-level student in behavior analysis served as a secondary observer and scored each training video lecture to determine adherence to the training model. Items scored for the training on recording the descriptive assessment data included narrative ABC form defined, the rationale for ABC data collection presented, sections described, examples provided, and two codewords presented vocally and visually. Items scored for the training on interpreting the descriptive assessment data included a rationale for ABC data collection, stated steps to interpret ABC data, reviewed functions of correlated with observations, provided examples of functions, described conditional probabilities, described how to calculate conditional probabilities, provided two examples of calculating conditional probabilities, and two codewords presented vocally and visually. Items scored for the training on selecting a function-based treatment included stated steps to identify a function-based treatment, provided examples of each function and reinforcers, described and provided examples of antecedent manipulations, described and provided examples of replacement behaviors, treatments described for each function of behavior, reviewed reductive strategies and ethical concerns with their use, and two codewords presented vocally and visually.

The researcher recorded the synchronous feedback sessions and later two doctoral-level behavior analysis students scored the videos based on a provided rubric. The rubric included the following items: ensures students received written feedback, identifies common errors for class, provides examples with a walk-through of their completion, provides practice examples, provides positive and corrective feedback, and provides instruction for next steps. The researcher calculated the percentage of adherence to the training model for both procedural integrity measures (i.e., for training and feedback). The secondary observer collected procedural integrity data for 41% of synchronous feedback opportunities and the data collected showed 100% accuracy.

Social Validity Measures

Expert Evaluation

Twelve doctoral-level behavior analysts scored each video scenario for the level of difficulty, identification of antecedents, and identification of consequences. The evaluators were selected using a convenience sample and they were all professors of behavior analysis with experience teaching master level students. The scenarios were randomly assigned a number label that correlated with the number label on the worksheet. The researcher provided each evaluator with a worksheet that provided an operational definition of the target behavior for each number labeled scenario to score and access to an electronic folder containing all scenarios. Each evaluator independently and asynchronously scored the scenarios. Upon completion of the worksheet, the evaluators emailed their completed worksheets to the researcher.

Evaluators assessed the level of difficulty for each video scenario to ensure equal distribution of difficulty across the sessions. The researcher instructed each evaluator to “please rank how you view the level of difficulty to record narrative ABC data from the video clip to then be analyzed for a possible function of behavior.” The evaluators were not provided with operational definitions of the levels of difficulty but instructed to use their own clinical judgment.

The evaluators also scored if the scenarios had at least one observable antecedent and at least one observable consequence. The worksheet had one column for the score for antecedent and one column for the score for consequence. The evaluators scored each scenario by selecting “yes” or “no” within the designated columns for that scenario and variable. The researcher provided the evaluators with the descriptions of what constitutes an antecedent and a consequence to what immediately occurs before and after the stated behavior for each scenario, respectively. The evaluators were also given the example “after stating the instruction once (antecedent) and the stated target behavior occurred, did something occur instead of compliance to the instruction such as repeated instruction or continued access to the item engaged in before instruction (consequence).”

In addition, these evaluators provided a measure of social validity, as the evaluators assessed the video exemplars for relevance to natural clinical contexts. Using the same worksheet and procedure as above, the researcher also instructed the evaluators to “please select if you find the video scenario to demonstrate an example of problem behavior or non-compliance that could be observed in clinical practice.” On the worksheet, the evaluators scored each scenario for clinical relevance by selecting “yes” or “no” within the designated column for that scenario.

Participant Evaluation

Following the study, each participant completed an anonymous questionnaire that assessed the social validity of their participation in the study. The participants completed the survey anonymously via an online survey website, Qualtrics. The participants responded to seven questions on the survey using a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) for each training completed (Table 1). Two open-ended questions also allowed the participants to comment on areas of strengths and weaknesses of the trainings by asking “Things I liked about the lesson” and “Recommendations for improvement.” The researcher developed the questions to identify components of instruction and to get feedback for the development and implementation of future training.

Table 1.

Participant Evaluation of Social Validity Results

| Question | Skill Training | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recording | Interpretation | Selection | |

| The written handout was clear | 4.33 | 4.22 | 4.00 |

| The video lecture helped me understand the content | 4.67 | 4.44 | 4.33 |

| The examples provided further helped my understanding | 4.67 | 4.44 | 4.56 |

| The individual feedback further helped my understanding | 4.67 | 4.67 | 4.33 |

| I believe this training would assist others in the field | 4.56 | 4.67 | 4.44 |

| I would recommend this training for other students of behavior analysis | 4.56 | 4.67 | 4.44 |

| I feel more confident conducting and analyzing ABC data as a result of this training | 4.67 | 4.44 | 4.33 |

Note. The average score of participant responses based on the selection of strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree (4), or strongly agree (5).

Experimental Design and Procedures

This study evaluated the effects of the training procedure using a multiple baseline design across skills. The researcher implemented training for all skills in the same order given the natural progression of recording data, then analyzing the data, and finally selecting a function-based intervention. The analysis consisted of two phases: (1) baseline and (2) training. The training for each skill included written instruction, video lectures with demonstrations, practice, and feedback. The researcher implemented the components based on past research and the delivery method of the trainings.

Baseline

Before training, all participants had access to an operational definition of a behavior, were individually shown two video scenarios of the target behavior, and were provided a worksheet for completion based on the episodes viewed. The researcher instructed the participants to individually complete the worksheet to the best of their abilities based on the videos they viewed. The worksheets had space for narrative ABC data collection, interpretation of results, and selection of intervention (see Appendix A). The researcher did not provide feedback on the skills targeted for intervention. Each session consisted of two novel videos demonstrating the stated target behavior for that session, and participants were able to watch the videos as many times as needed for them to complete the worksheet.

Training

The researcher provided the participants with a 1–4-page handout of written instructions to read based on previous studies. The handout for recording ABC data collection was 1.5 pages and based on the instructions provided in Mayer and DiGennaro Reed (2013). The handout included a bulleted list of key items required to be recorded for each section. For example, in the first section, it lists items such as date, time (within 10 min of occurrence), specific location (with examples and nonexamples), and the therapist’s initials. The antecedent section listed items that may have occurred before the target behavior that need to be included such as the ratio of people present, what task or activity was occurring, environmental variables such as noise level, and if a person denied requests or items. The behavior section included items such as the general class of the behavior and the topography of the observed instance. The consequence section included items such as the staff and parent response to the behavior, who intervened, was a peer present and if so what they did, and if a new activity was presented.

The interpretation of the results handout was a one-page handout based on the description of calculating conditional probabilities from Lerman and Iwata (1993). This handout included the table from Lerman and Iwata that outlined the calculation of conditional probabilities for antecedents and consequences. Following the table, written instructions detailed each step found in the table. For example, it instructed the participants to count the number of occurrences of an event that occurred as an antecedent equaling the target function then divide that by the total occurrences of the target behavior observed.

The selection of intervention handout was a 4-page handout that included decision trees for each function; automatic (Berg et al., 2016), escape (Geiger et al., 2010), attention (Grow et al., 2014), and tangible (adapted from Tiger et al., 2008). Each decision tree started with the identified function and branched down to treatment options based on the characteristics of the behavior and environmental conditions. For example, Geiger et al. (2010) started by asking if the curriculum (or demand) is appropriate. This question leads to either modifying the demand or the second tier that then asks if the environment can tolerate the present level of behavior. If the environment can tolerate the level of behavior the next tier is introduced but if it cannot then demand fading is recommended. The questions continue through six possible evidence-based treatment options.

Participants then watched a short video-recorded lecture (approximately 10–17 min in length). Each video lecture included a PowerPoint presentation with voice-over narration that defined and explained terms and provided a step-by-step explanation and demonstration of the target skill with a given example. Participants were able to view the video-recorded lecture as many times as they wanted for review in between sessions during the training. The participants viewed the video recorded lecture for recording ABC data a mean of 3.38 times (range: 1–8), for interpreting results a mean of 6.75 times (range: 3–17), and for selecting treatment a mean of 5.13 times (range: 1–12). Participants had continued access to the treatment materials throughout the study as clinicians often review protocols before conducting assessments. The participants had access to a handout of PowerPoint slides from the lecture (without the codewords for submission) and a handout of the written instructions available for them to download and save to use as a reference.

After participants read the written instructions and watched the video lectures asynchronously, they submitted two codewords presented in the lecture to ensure contact with the material. The researcher then provided the participants with an operational definition of a behavior, individually showed two episodes of the target behavior, and provided a worksheet for completion based on the episodes viewed. Participants completed all sections of the worksheet to the best of their abilities regardless of the skill trained.

The lead researcher provided written feedback for the specific skill targeted in the training to each participant individually. The written feedback was provided via message in Canvas and included corrective feedback for commission and omission errors as well as positive feedback for correctly completed items. If proficiency (80% accuracy or better) of the skill was not acquired in any session, the participant met with the lead researcher to receive more specific feedback via Zoom synchronously. The items covered within the scoring rubrics (see Appendix B) were items reviewed with participants to ensure consistency of items discussed across feedback sessions. The researcher created a PowerPoint presentation for each session’s synchronous feedback review that included a review of content from the video lecture, common errors made, a presentation of a corrected example, a practice example, and next steps for the participants. The lead researcher varied verbal feedback as appropriate, based on participant performance and the scoring rubric for the skill. The participant was able to ask questions to the researcher, which included clarifying questions of the material and questions about the next steps for completion. In each synchronous feedback session, there were one to three participants. Only one participant attended two synchronous feedback sessions because they were the only one to not reach proficiency for that session. The remaining sessions had two to three participants as the amount varied based on participant availability to meet and how many participants required feedback per session based on performance.

The training of each skill continued until proficiency (80% or better accuracy) was observed across three sessions for that participant. The researcher selected this level of proficiency based on past research demonstrating that accuracy at this level across multiple sessions is an acceptable learning criterion (Luna et al., 2018; Roscoe & Fisher, 2008; Sidman, 1987). Once the participant met proficiency of the target skill, the researcher introduced the training of the next skill in the same manner. This study controlled access to materials with the use of the online platform’s ability to lock assignments for students as needed, and until proficiency of prior material was assured. The researcher only unlocked assignments upon completion and proficiency of the previous assignments.

Generalization

The participants completed generalization probes in baseline and after criterion was met at the conclusion for training of all skills. During these probes, the researcher presented the participants with written scenarios instead of a video scenario. Participants completed one probe, in baseline and after criterion was met at the conclusion of training, with the narrative ABC worksheet from training. This probe assisted in determining generalization to other types of scenarios (written vs. video), as behavior analysts are often provided with descriptions of potential clients during a record review to begin hypothesizing antecedents and consequences to problem behavior. Another probe was conducted, in baseline and after criterion was met at the conclusion of training, using a structured ABC worksheet. This probe assisted in determining whether training conducted with the narrative form would generalize to other types of data collection used during descriptive assessments.

Results

Figure 1 depicts the mean percent accuracy of all participants across phases and skills. Low percent accuracy was observed in the baseline for each skill with an increase in accuracy levels to proficiency following training for each skill. Individual written feedback occurred following every session regardless of whether proficiency was met. Synchronous feedback sessions were required for participants to reach proficiency a mean of 1.22 times for recording, 1.33 times for interpreting, and .44 times for selecting an intervention. Common errors made for recording included missed occurrences of behavior and omissions of location and ratio of people present. Common errors for interpreting included omission of possible functions and calculating conditional probabilities per occurrence of behavior instead of cumulative across the occurrences. Common errors for selecting an intervention included errors in identifying a function-based target behavior for increase and treatment for decreasing behavior. All participants generalized performance to criterion with the written scenarios using the narrative form and seven participants generalized performance to criterion using the structured form.

Fig. 1.

Average Participants’ Percent Accuracy across Skills and Phases

Figure 2 displays the percent accuracy across baseline and training for Brody, Danika, and Faith. The left panel displays Brody’s performance with a mean of 27% accuracy for recording, a mean of 3% accuracy for interpreting, and 0% accuracy for selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 92% for recording, a mean of 69% for interpreting (mean of 96% across the last five sessions), and 95% for selecting an intervention. Brody required two synchronous feedback sessions to achieve proficiency in the skills of recording and interpreting and one synchronous feedback session for selecting an intervention. Brody demonstrated generalization to the written scenario with the narrative form. Though Brody's performance increased in the generalization probe with the written scenario with the structured form, he did not meet the criterion. The middle panel displays Danika’s performance with a mean of 39% accuracy for recording and a mean of 0% accuracy for interpreting and selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 95% for recording, a mean of 80% for interpreting, and 88% for selecting an intervention. Danika required two synchronous feedback sessions to achieve proficiency for interpreting and one synchronous feedback session for recording and selecting an intervention. Both generalization probes conducted after criterion was met at the conclusion of training for Danika met proficiency. The right panel of Figure 2 displays the percent accuracy across baseline and training for Faith and her responding mirrors Danika’s performance; however, Faith only required one synchronous feedback session to reach proficiency for each skill.

Fig. 2.

Percent Accuracy across Skills for Brody, Danika, and Faith

Figure 3 displays the percent accuracy across baseline and training for Addison and Zachary. Both participants had similar patterns across skill sets. The left panel displays Addison’s performance with a mean of 27% accuracy for recording, a mean of 13% accuracy for interpreting, and a mean of 11% for selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 96% for recording, a mean of 80% for interpreting, and 100% for selecting an intervention. Addison required two synchronous feedback sessions to reach proficiency for recording and interpreting and did not require synchronous feedback sessions for selecting an intervention. Addison demonstrated generalization to the written scenario with the narrative form. Though Addison's performance increased in the generalization probe with the written scenario with the structured form, she did not reach the criterion. The right panel displays Zachary's performance with a mean of 23% accuracy for recording, a mean of 3% accuracy for interpreting, and a mean of 20% for selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 93% for recording, a mean of 86% for interpreting, and 100% for selecting an intervention. Zachary required one synchronous feedback session to reach proficiency for recording and interpreting and did not require synchronous feedback sessions for selecting an intervention. Both generalization probes conducted after criterion was met at the conclusion of training for Zachary met proficiency.

Fig. 3.

Percent Accuracy across Skills for Addison and Zachary

Figure 4 displays the percent accuracy across baseline and training for Shelby and Evelina. The left panel displays Shelby’s performance with a mean of 41% accuracy for recording, a mean of 10% accuracy for interpreting, and a mean of 37% for selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 96% for recording, a mean of 80% for interpreting, and 91% for selecting an intervention. Shelby required one synchronous feedback session to reach proficiency for each skill. Both generalization probes conducted after criterion was met at the conclusion of training for Shelby met proficiency. The right panel displays Evelina’s performance with a mean of 34% accuracy for recording, a mean of 10% accuracy for interpreting, and a mean of 56% for selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 96% for recording, a mean of 83% for interpreting, and 100% for selecting an intervention. Evelina required one synchronous feedback session to reach proficiency for recording and interpreting and did not require synchronous feedback sessions for selecting an intervention. Both generalization probes conducted after criterion was met at the conclusion of training for Evelina met proficiency.

Fig. 4.

Percent Accuracy across Skills for Shelby and Evelina

Figure 5 displays the percent accuracy across baseline and training for Rylee and Callum. The left panel displays Rylee’s performance with a mean of 26% accuracy for recording, a mean of 7% accuracy for interpreting, and a mean of 50% for selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 96% for recording, a mean of 86% for interpreting, and 100% for selecting an intervention. Rylee required one synchronous feedback session to reach proficiency for recording and interpreting and did not require synchronous feedback sessions for selecting an intervention. Both generalization probes conducted after criterion was met at the conclusion of training for Rylee met proficiency. The right panel displays Callum’s performance with a mean of 30% accuracy for recording, a mean of 10% accuracy for interpreting, and a mean of 50% for selecting an intervention. Upon implementation of training, all three skills displayed an immediate increase in level to proficiency, with a mean of 90% for recording, a mean of 80% for interpreting, and 100% for selecting an intervention. Callum required one synchronous feedback session to reach proficiency for recording and interpreting and did not require synchronous feedback sessions for selecting an intervention. Both generalization probes conducted after criterion was met at the conclusion of training for Zachary met proficiency.

Fig. 5.

Percent Accuracy across Skills for Rylee and Callum

Social Validity

Expert Evaluation

The evaluators scored the majority of the video scenarios at an easy or moderate level of difficulty. The randomization presented scenarios with an equal level of difficulty as evidenced by the evaluators scoring scenarios within one level of difficulty (easy and moderate) for 21 of the 24 scenarios. The three scenarios rated by some scorers as difficult were randomly assigned to the last session of training for the second skill and the last two sessions of training for the third skill limiting the extent to which this influenced skill acquisition.

The evaluators also scored each video scenario and written scenario as having one or more antecedents and one or more consequences identifiable. The twelve evaluators scored a mean of 95% (range: 79%–100%) of the video scenarios having an identifiable antecedent and a mean of 85% (range: 13%–100%) of the video scenarios having an identifiable consequence. The written scenarios have a mean of 98% (range: 75%–100%) for identifiable antecedents and 94% (range: 50%–100%) for identifiable consequences. One of the evaluator’s scores appears to be an outlier from the remainder of the group, as the evaluator frequently noted opposite rankings from the other evaluators. However, even with the outlier data set included, the data still fell within the acceptable range of at or above 85% (Cooper et al., 2020; Kleinmann et al., 2009).

The 12 evaluators also scored each video scenario based on relevance to natural clinical contexts and scored a mean of 99% of the video scenarios (range: 92%–100%) as clinically applicable. All the evaluators also scored all four of the written scenarios as clinically applicable.

Participant Evaluation

Following the completion of the study, all nine participants completed an anonymous questionnaire that assessed social validity (Table 1). Each question had a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. All questions resulted in mean scores of four or higher demonstrating that participants found the trainings helped further their understanding, could assist others in the field, and increased their confidence to conduct and analyze ABC data. One participant commented that they were able to use other knowledge from the course to complete this skill and one participant stated the lectures and handouts were very helpful for this skill. Comments from participants on the open-ended questions included that they liked the live feedback to engage in more practice with clear examples, they formed a better understanding of the functions of behavior as it relates to the observed antecedents and consequences, and they wanted more practice in selecting a function-based treatment. In general, participants viewed all skills as relevant to practice and of importantance to learn.

Discussion

The current study investigated a training for graduate students in behavior analysis for three-component skills of descriptive assessments: identifying antecedents and consequences, interpreting descriptive assessments, and selecting a function-based intervention. All participants in this study increased performance on all three skills following the training. For those participants who did not initially reach proficiency following the training, proficiency was met following synchronous feedback on performance. Though the researcher collected data on each aspect of the skill (antecedent, consequence, combination of total skill), participants did not demonstrate differences across the aspects. Performance of all participants increased from a baseline mean of 13% accuracy across skills to a mean of 91% accuracy across skills following the training. With direct training on the aspects of a descriptive assessment, participants increased the accuracy of the assessment and demonstrated an increase in performance on both generalization probes. The generalization probes increased from a mean at baseline of 9% accuracy to a mean of 94% after criterion was met at the conclusion of training. The consistency across participants, on recording the observed antecedents and consequences and on interpreting the function of the behavior, is clear. Overall, the study demonstrates an increase in the accuracy of the implementation of the descriptive assessment.

This study adds to the training literature on descriptive assessments. The current use of descriptive assessments is high (Oliver et al., 2015) and the current study provides an effective method for increasing future clinicians’ ability to accurately implement all components of descriptive assessments. This training extended training to other components of the process as compared to previous research solely focusing on the recording of the data (Luna et al., 2018; Mayer & DiGennaro Reed, 2013; Pence & St. Peter, 2018). Furthermore, different techniques of interpretation may lead to different outcomes and reduce the chances of the clinicians implementing a function-based treatment (St. Peter et al., 2005). This study also supports specific training on calculating the conditional probabilities to determine the hypothesized function of the problem behavior in a scenario. The use of conditional probabilities brings a level of specification to the process that may aid acquisition and increase the reliability and validity of the method to then select a function-based treatment.

Further support for the need for training the selection of function-based treatments is evident in the inconsistencies seen in the participants’ baseline performances. Inconsistent accuracy to select function-based treatments may lead to procedures being implemented that only temporarily reduce problem behavior or that inadvertently reinforce the problem behavior. In this study, some participants demonstrated variable baseline performances, with some data points above the criterion (Rylee, Callum, and Evelina). It should be noted that one of those participants was an RBT (Callum) and one of those participants indicated that they had previous coursework on descriptive assessments (Evelina). Variable baseline performances also may have been partially the result of the participant's clinical experience working in the field before the start of the study. Upon the implementation of the training package, all participants consistently selected appropriate function-based interventions. This finding has important potential implications for their future clinical work as it further supports the need for training the selection of function-based treatments following the identification of the function.

The use of asynchronous methodologies to train clinicians also offers a valuable resource for clinicians by reducing time spent with trainees without reducing their time in training. One unique element of the instruction within this training was that it was presented asynchronously with electronically submitted assessments. This does require familiarity and access to online platforms. The researcher selected the platform, Canvas, for this study as it was the platform provided by the college of the participants; however, other platforms could be used such as Google Drive. One advantage of the asynchronous methodology was that participants were able to view lectures and videos individually and on their own time. All of the participants viewed at least one video lecture multiple times and seven of the nine participants viewed all the video lectures multiple times. Continued access to the video lectures may have provided additional learning opportunities and further increased their comprehension of the more complex material.

Clinicians and researchers need to examine other applications of the approach, including training in the identification of complex behavioral functions and extending the training to include live observations. Clinicians and researchers should also investigate the use of this training method with more complex scenarios, including live observations, as the current investigation used scenarios scored as easy to moderate levels of difficulty and were video recorded. Following the demonstration of improving the accuracy of descriptive assessments, researchers should then compare the descriptive assessment with a functional analysis to determine if the accurate implementation of the descriptive assessment increases its validity.

A component analysis would also be beneficial to determine which specific instructional element(s) makes a difference in training clinicians to accuracy. All participants received individualized written feedback after each session of training. For participants to meet proficiency, all participants required additional feedback via synchronous sessions with the researcher for recording and interpreting the descriptive assessments. Four of the nine participants required additional synchronous feedback with the researcher for selecting a function-based treatment. The majority of additional synchronous feedback sessions within this study occurred publically in that more than one participant was present; however, there were two sessions that only one participant was present due to being the only participant that did not reach proficiency for that session. It is possible that the different types of synchronous feedback sessions played a role in the participants’ acquisition. The need for additional feedback within this study further supports literature stating the importance of feedback within training models for participants to meet proficiency (Gerencser et al., 2020; Roscoe & Fisher, 2008). Future research should continue to explore this area with online trainings, by completing a component analysis and by investigating the effects of public and private synchronous sessions.

Not having the adequate time or staff trained to implement functional analyses is a stated barrier for many behavior analysts (Hanley, 2012; Lerman & Iwata, 1993; Madsen et al., 2016). Multiple participants completed the training method used in the current investigation asynchronously, allowing for less time spent training individuals. One benefit to this methodology is the ability to train more individuals with minimal additional time from the trainer. Furthermore, extending this model to group training contexts could further enhance the efficiency of the training. In this study, this training method was also generalized to the structured ABC data collection method for six of the nine participants, which further supports less additional training time needed for other types of descriptive assessments.

Time-efficient trainings are a vital consideration given that time spent training is a limited commodity and the allocation of training resources must be carefully considered within organizations. The asynchronous training model used within this study decreases the time spent implementing training. The trainings did require time spent making materials and recording lectures for the training, which was not directly measured for this study. However, the materials can be reused in future renditions of the same training. The implementation of each synchronous feedback session added some additional time from the trainer but eat session was only approximately 21 min. Future research should further examine the efficiency of the training by measuring the time the participants spent in training and the time the trainer spent creating materials.

Although this study has both research and clinical implications, it is not without its limitations. One limitation resulted from the training being implemented within a graduate-level course. The course format introduced some variables outside of the researcher’s influence. The restriction of timelines played a large role in the development of the trainings. All training needed to be scheduled within that course's semester. Trainings were spaced out evenly throughout the semester, with ample weeks between trainings to ensure proficiency of skills before the implementation of the next skill. Still, the semester format imposed real-world logistical challenges and deadlines. Limited practice opportunities for selecting a function-based treatment may be why the participants scored this training's effectiveness lower than the other two trainings.

Future research should implement the training outside of a course to further enhance aspects of the training. Conducting the training during supervised fieldwork experiences, instead of during coursework, may increase the learning opportunities and improve the social validity of the study by demonstrating that the implementation of the intervention using these skills led to more effective behavioral treatment in the field. It may also help to ensure adequate time for training, rehearsal, and feedback, as more practice time was requested by at least one participant in the social validity survey. Furthermore, conducting the training outside of an online graduate course would enhance the ability to generalize the skills to live observations, as a limitation to this study was that it only examined generalization across data collection systems and to written scenarios. The generalization to live in-vivo observations would further enhance the value of the training presented in the current study.

Providing the training within courses also added limitations regarding procedures and participant motivation. The asynchronous nature of the training allowed participants to view the video scenarios as many times as needed to complete the descriptive assessment. Multiple views of the same occurrence of problem behavior are not possible when conducting descriptive assessments live with clients unless behavioral episodes are video recorded. The participants' motivation to get a good grade in the class may also have affected participant performance. Receiving a passing grade on the assignment to pass the course may increase student motivation to thoroughly complete the assignment. Addison's and Zachary's data showed a sudden decrease to zero accuracy in the selection of treatment during baseline which suggests a possible change in motivation due to grades. Participants received full credit for assignments regardless of performance on skills not yet trained. It is possible that Addison and Zachary learned the contingency of a good grade regardless of performance on untrained skills, which reduced their responses on those skills until the contingency changed following training. Future research should investigate the training procedures in other settings, where grades are not a contingency, such as in clinical settings.

Another limitation of the study is a possible sequence effect of the skills taught. Each participant received the training in the same order. This sequence represents the natural progression of the skills and the order in which clinicians conduct descriptive assessments, as one cannot select a function-based treatment without first interpreting data to hypothesize a function and one cannot interpret data until one records data. All participants required synchronous feedback sessions for the first two skills taught, and some participants required multiple feedback sessions before the criterion was reached. Participants required fewer feedback sessions for the final skill taught than for previous skills, which may be a result of a sequence effect of the training. Future research should examine if the reduced need for feedback was the result of a sequence effect or the result of clinical experience with selecting a function-based treatment before training.

Continuation in this line of research is essential to learn more about how training can develop competent clinical skill sets in assessment. Furthermore, much more research is needed to ensure that assessment results link to proper treatment selection and effective implementation with clients. Future research should examine the comparison of descriptive assessments after implementation of the competency-based training with experimental functional analyses. This comparison is essential to understand the relative accuracy and rigor of descriptive assessment (when well-trained). In addition, research should focus on the implementation of training to larger groups of individuals, the use of various online platforms, generalization of training to live observations, the provision of additional practice and feedback opportunities as a way to boost effectiveness and clinician competence, and acquired skill maintenance over time.

Given the low validity of descriptive assessments and their high level of clinical use, researchers and clinicians are faced with a choice of how to proceed. They can either abandon their use or work to better understand their potential use by exploring how to improve them. Stopping their use appears to be premature; the implementation and interpretation of descriptive assessments could be improved, which may lead to more accurate results. This study supports working to improve their accuracy through competency-based training to proficiency and suggests that an increase in the accuracy of descriptive assessments is possible. More research is needed to replicate and extend these preliminary results.

Appendix A

The Worksheet for Participant Completion.

Appendix B

Scoring Rubric for Recording ABC Data

Scoring Rubric for Interpreting Data with Conditional Probabilities

Scoring Rubric for Selecting a Function-Based Intervention

Declarations

Conflict of interests

We have no known conflict of interests to disclose and no funding was provided for this project. Study-specific approval was granted from an ethics committee due to research involving humans and informed consent to participate in the research was received.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Footnotes

In this article, the researchers defined accuracy as the agreement of the observers scoring the same behavior

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bearss K, Johnson CR, Handen BL, Butter E, Lecavalier L, Smith T, Scahill L. Parent training for disruptive behavior: The RUBI autism network, parent workbook. Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berg WK, Wacker DP, Ringdahl JE, Stricker J, Vinquist K, Salil Kumar Dutt A, Dolezal D, Luke J, Kemmerer L, Mews J. An integrated model for guiding the selection of treatment components for problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49(3):617–638. doi: 10.1002/jaba.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijou SW, Peterson RF, Ault MH. A method to integrate descriptive and experimental field studies at the level of data and empirical concepts. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(2):175–191. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp EM, Iwata BA, Hammond JL, Bloom SE. Antecedent versus consequent events as predictors of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42(2):469–483. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson SA, Miltenberger RG, Stricker J, Galensky TL, Garlinghouse M. Functional assessment and intervention for challenging behaviors in the classroom by general classroom teachers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2000;2(2):85–97. doi: 10.1177/109830070000200202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falender CA, Shafranske EP. The importance of competency-based clinical supervision and training in the twenty-first century: Why bother? Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2012;41(3):129–137. doi: 10.1007/s10879-011-9198-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger KB, Carr JE, LeBlanc LA. Function-based treatments for escape-maintained problem behavior: a treatment-selection model for practicing behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2010;3(1):22–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03391755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerencser KR, Akers JS, Becerra LA, Higbee TS, Sellers TP. A review of asynchronous trainings for the implementation of behavior analytic assessments and interventions. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2020;29:122–152. doi: 10.1007/s10864-019-09332-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grow LL, Carr JE, LeBlanc LA. Treatments for attention-maintained problem behavior: Empirical support and clinical recommendations. Journal of Evidence-Based Practices for Schools. 2014;10(1):70–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Fisher WW, Thompson RH, Owen-DeSchryver J, Iwata BA, Wacker DP. Toward the development of structured criteria for interpretation of functional analysis data. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30(2):313–326. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G. Functional assessment of problem behavior: Dispelling myths, overcoming implementation obstacles, and developing new lore. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(1):54–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03391818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, McCord BE. Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36(2):147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinmann AE, Luiselli JK, DiGennaro FD, Pace GM, Langone SR, Chochran C. Systems-level assessment of interobserver agreement (IOA) for implementation of protective holding (therapeutic restraint) in a behavioral healthcare setting. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2009;21:473–483. doi: 10.1007/s10882-009-9153-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DC, Hovanetz A, Strobel M, Tetreault A. Accuracy of teacher-collected descriptive analysis data: A comparison of narrative and structured recording formats. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2009;18(2):157–172. doi: 10.1007/s10864-009-9084-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DC, Iwata BA. Descriptive and experimental analyses of variables maintaining self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26(3):295–319. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna O, Petri JM, Palmier J, Rapp JT. Comparing accuracy of descriptive assessment methods following a group training and feedback. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2018;27(4):488–508. doi: 10.1007/s10864-018-9297-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mace C, Lalli JS. Linking descriptive and experimental analyses in the treatment of bizarre speech. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(3):553–562. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EK, Peck JA, Valdovinos MG. A review of research on direct-care staff data collection regarding the severity and function of challenging behavior in individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2016;20(3):296–306. doi: 10.1177/1744629515612328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KL, DiGennaro Reed FD. Effects of a training package to improve the accuracy of descriptive analysis data recording. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2013;33(4):226–243. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2013.843431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver AC, Pratt LA, Normand MP. A survey of functional behavior assessment methods used by behavior analysts in practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(4):817–829. doi: 10.1002/jaba.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MB, Rollyson JH, Carolina N, Reid DH. Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(2):2–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence ST, St. Peter CC. Training educators to collect accurate descriptive-assessment data. Education & Treatment of Children. 2018;41(2):197–222. doi: 10.1353/etc.2018.0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe EM, Fisher WW. Evaluation of an efficient method for training staff to implement stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41(2):249–254. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe EM, Phillips KM, Kelly MA, Farber R, Dube WV. A statewide survey assessing practitioners’ use and perceived utility of functional assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(4):830–844. doi: 10.1002/jaba.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasso GM, Reimers TM, Cooper LJ, Wacker D, Berg W, Steege M, Kelly L, Allarire A. Use of descriptive and experimental analyses to identify the functional properties of aberrant behavior in school settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(4):809–821. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger HD, Normand MP. On the origin and functions of the term functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46(1):285–288. doi: 10.1002/jaba.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Two choices are not enough. Behavior Analysis. 1987;22(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- St. Peter CC, Vollmer TR, Bourret JC, Borrero CSW, Sloman KN, Rapp JT. On the role of attention in naturally occurring matching relations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38(4):429–443. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.172-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RH, Iwata BA. A descriptive analysis of social consequences following problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34(2):169–178. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RH, Iwata BA. A comparison of outcomes from descriptive and functional analyses of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40(2):333–338. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.56-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiger JH, Hanley GP, Bruzek J. Functional communication training: a review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1(1):16–23. doi: 10.1007/BF03391716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ethics-Code-for-Behavior-Analysts-2102010.pdf

- Cooper, J. C., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Iwata, B. A., Kahng, S., Wallace, M. D., & Lindberg, J. S. (2000). The functional analysis model of behavioral assessment. In J. Austin & J. E. Carr (Eds.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis (pp. 61–89). Context Press.