Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the reported impact of noncompete clauses (NCCs) on practitioners in the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA). Thirty-seven percent of respondents indicated they currently worked under a NCC, 33% reported working under one in the past, and 30% reported never working under one. Responses on the effects of NCCs on practitioners’ personal and work lives were mixed. Some respondents reported benefits associated with working under an NCC such as increased pay and reduced commute. However, a concerning number of respondents reported being involved in litigation, having to partially or completely stop working in the field of ABA, having to turn away clients due to NCCs, or contemplating leaving the field altogether. Further, many owners reported using NCCs to protect trade secrets, to avoid losing clients, and reduce employee turnover. The impact of NCCs in ABA, the rights of employees and owners, and suggestions for potential solutions in the field are discussed.

Keywords: applied behavior analysis, autism spectrum disorder, noncompete clauses

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is the application of principles of behavior principles and operant learning theory to address problems of social significance in a variety of areas such as the treatment of developmental disabilities, improving organizational performance, and in education (Baer et al., 1968; Horner & Sugai, 2015; Roane et al., 2016; Wilder et al., 2009). At present, one the largest area of application of ABA is in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Decades of research and several meta analyses have demonstrated that ABA treatments are effective for teaching communication, adaptive skills, and reducing dangerous behaviors exhibited by individuals with ASD (Makrygianni et al., 2018; Peters-Scheffer et al., 2011; Virués-Ortega, 2010). The number of behavior analysts certified by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB) has continually grown since the development of the credential in 2008 and the demand for behavior analysts increased by over 4000% between 2010 and 2020 (BACB, 2021a, b).

As with any other service provided to consumers, ABA organizations1 that provide ABA services to individuals must produce a profit to stay viable. In addition to paying employees’ salary and benefits, organizations must bear costs such as rent, insurance, administrative support staff, and supplies, to name a few. A requirement of most insurance companies that cover ABA services is that the services (including those implemented by technicians) are overseen by a board certified behavior analyst (BCBA). Thus, the ability of organizations that provide only or mostly ABA services to obtain payment for services and remain viable is closely tied to the number of BCBAs and board certified behavior analysts-doctoral (BCBA-Ds) who work within the organization to oversee service delivery. Given the existing shortage of individuals credentialed by the BACB, and the demand for people who hold credentials offered by the BACB, it is imperative that organizations retain these employees. Therefore, it is an understatement to say that the availability of BCBAs and BCBA-Ds are critical for these organizations and the field of ABA to grow.

One organizational practice that directly affects the availability of ABA practitioners is the use of noncompete clauses as part of employment agreements. Noncompete clauses (NCCs) are clauses in employment contracts that prevent an employee from working in the same field for defined period of time and/or within a defined geographic region after leaving an organization (Huntoon et al., 2020). Employees of ABA organizations who sign NCCs and later desire to leave their position could be prohibited from practicing ABA for a period of time within a specific geographic region. For example, an employee who signed a NCC may not be allowed to work in the field of ABA for 6 months within a 50-mile radius of the organization. Violation of the NCC can potentially result in costly legal disputes and the employee having to resign their new job if the NCC is enforced.

Although the use of NCCs are not new, NCCs have recently been discussed on a national level due to their potential to affect the U.S. economy. Of note, the Biden White House issued an Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy on July 9, 2021 (Executive Order No. 14036, 2021). In this order, the importance of competition in the U.S. economy was stressed, and the executive order specifically sought government agency support to “to address agreements that may unduly limit workers’ ability to change jobs” and “curtail the unfair use of non-compete clauses and other clauses or agreements that may unfairly limit worker mobility” (section 5g). It is clear, NCCs and their restriction on when and where employees can go to work are not aligned with the values of this executive order.

Noncompete clauses have also received special attention in medical professions (see Beh, 2011; Huntoon et al., 2020; Pashkov & Harkusha, 2019). A recent publication from the Journal of the American Medical Association called attention to the need for a national solution for NCCs in the practice of medicine (Smith, 2021). The main concern echoed across many of these commentaries is one that is unique to medical professions: the risk that NCCs can restrict client access to necessary medical treatment(s). Smith (2021) summarizes the issue by stating that “health care workforce integrity and mobility is a national problem” and that the continued use of NCCs causes NCCs to “stifle patient access to care and prevent physicians from practicing medicine in their own communities” (p. 3).

The same risk of NCCs interfering with client access to care in medicine also exists in the field of ABA. Although NCCs have the potential to protect the interests of business owners, they also have the potential to reduce the number of qualified practitioners (e.g., BCBAs) available within a given geographic region. Brodhead et al. (2018) were the first to caution on the use of NCCs in the field of ABA. In their article, they clarified what NCCs are, what they mean for the practicing behavior analyst, and urged caution on the part of behavior analysts who were asked to sign them. Reasons given for this caution include the questionable relevance of NCCs in ABA, potential to limit the bargaining power of employees, and the potential for the contract to cause undue pressure for a behavior analyst to have to stay at an organization despite ethical concerns. They summarized their section on NCCs by encouraging behavior analysts who are presented with one to review it with their legal counsel before signing any such contract.

In May 2020, the Behavioral Health Center of Excellence (BHCOE), the only accrediting body specific to ABA service provision at the time of writing this article, published a position paper in which they outlined their views and recommendations for organizational use of NCCs in ABA. The BHCOE advised that ABA organizations should consider whether NCCs are necessary, should use the least restrictive employment contract necessary to protect business interests, and consider the affect NCCs may have on the ABA industry (BHCOE, 2020). As a result, BHCOE’s 2021 Accreditation Standards now include an item (D.06) that indicates NCCs, if used, are limited to executive-level employees (BHCOE, n.d.).

To date, one study has examined the use of NCCs in the field of ABA. Brown et al. (2020) surveyed 610 practicing behavior analysts on the prevalence and views on the use of NCCs in the field of ABA. Their survey contained questions on practitioner opinions on the use of NCCs from business and practice standpoints. Results indicated that 33% of respondents reported that they had an employment contract that contained an NCC. In general, practitioner responses indicated that they viewed NCCs negatively from both a business and practice standpoint. A majority of respondents indicated they believed NCCs were not in the best interests of employees, were not necessary to protect trade secrets, were not necessary to protect businesses from losing employees, impaired the growth of ABA in some way, and believed NCCs were not in the best interests of consumers. Other questions yielded more mixed results, such whether respondents agreed that NCCs are in the best interests of owners, whether NCCs impaired their ability to practice, if NCCs were necessary for preventing departing employees from taking clients to their new organization, and if NCCs impaired owners’ abilities to effectively and ethically managing employees.

Although the survey by Brown et al. (2020) was an important step in examining the prevalence of NCCs and how practitioners view them, there were limitations to their survey. First, their survey reported practitioner opinions of NCCs and did not poll respondents about the actual effects NCCs had on them. Second, the survey by Brown et al. did not poll registered behavior technicians (RBT), who implement the bulk of ABA services delivered to consumers (BACB, 2021a), on the prevalence of NCCs with this population. Considering that RBTs implement the bulk of direct ABA services, assessing the impact of NCCs on their practice would give a more complete picture of the effects NCCs have on the field of ABA. Finally, Brown et al. did not poll owners of ABA organizations to find out why they used NCCs in their organizations. Answers to these questions are necessary for a complete analysis of the impact of NCCs in the field of ABA and to further understand the basis for their continued application. Finally, answering these questions may allow for the development of specific recommendations for behavior analysts and business owners to balance their individual rights to practice, earn a living, and run an organization while simultaneously maximizing high-quality consumer care and protection. Therefore, there are two research question(s) addressed in the current study: (1) What, if any, effect do NCCs have on BACB practitioners (including RBTs) personally and professionally? and (2) How frequently do owners who are BACB certificants use NCCs with their employees and why?

Method

Participants

Surveys were distributed to RBTs, board certified assistant behavior analysts (BCaBAs), BCBAs, and BCBA-Ds via the BACB’s mass email service and ABA groups/pages on social media sites (Facebook, Reddit). Broad survey distribution ensured that both owners and employees who were not subscribed to the BACB mass email service had an opportunity to be contacted. The BACB mass email service distributed links to the survey in the United States and the links on social media were freely available online. The survey was designed to not record the geographic locations of participants and did not allow for respondents to answer the survey more than once.

Materials

The survey was hosted by the Qualtrics (Provo, UT) survey site at a state university in the Midwest. The survey received approval from an institutional review board and contained a statement that completing the survey implied consent and that the respondent could withdraw at any time. The survey was comprised 38 questions, but the number of questions answered by each respondent could differ depending on how the respondent answered each question. Five questions asked about basic demographic and employment information. Six questions were for respondents who indicated that they currently were working under an NCC. A total of 23 questions were for respondents who indicated they previously worked under an NCC. Four questions were for individuals who indicated they were owners of ABA organizations. In addition to the questions above, the survey included text-based follow-up questions after some forced-choice questions that allowed respondents to input a text-based response.

Procedure

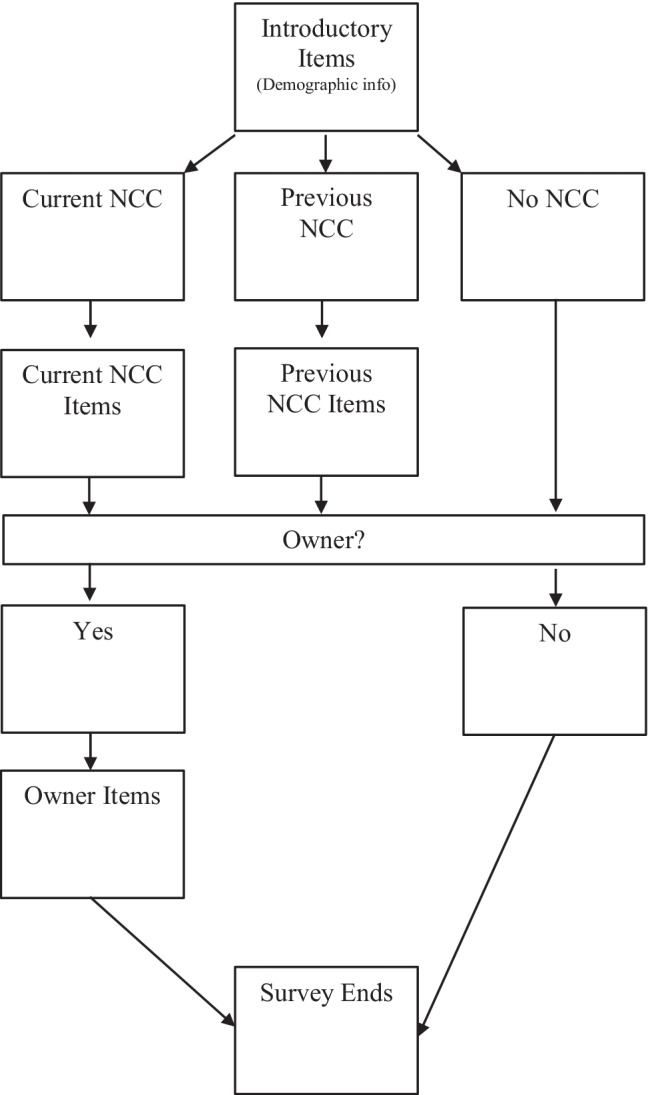

The survey was available for respondents to complete for 2 weeks. In the original recruitment post/email and on the consent page of the survey, potential respondents were informed they would have the option to provide their email address for a chance to receive one of four $25.00 gift cards for participation. The last question of the survey had a link to a separate form on Qualtrics for respondents to enter their email address. Emails notifying those who were selected to receive a gift card were sent out after the survey closed. Some of the questions allowed respondents to select more than one answer and total percentages may exceed 100%. To be included in analysis, respondents had to at least indicate their current certification level, their position in an ABA organization, and whether they currently, previously, or never had worked under an NCC. See Fig. 1 for the survey logic for all participants. Responses to survey items are reported as the percentage of respondents who endorsed a response choice out of all respondents who answered the question (i.e., valid percentage).

Fig. 1.

Survey logic for current study

Data Cleaning and Analysis

Prior to data analysis, data were screened and cleaned to ensure quality. Data from 18 respondents were removed for not indicating their current certification level, their position in an ABA organization, and whether they had experience with NCCs in ABA. In addition to the 18 who did not answer the required questions, data from 15 respondents who gave dichotomous responses across items (i.e., indicating they both received monetary compensation and no compensation for signing an NCC; see below) or who reporting working in the field for an improbable duration (80 or more years) were removed from analysis. The survey inadvertently asked respondents whether they had received compensation for signing an NCC on two items. These responses were recoded into a new variable so that the percentage of respondents who indicated they received compensation on either question were counted as an affirmative response. This left 5 questions for those who indicated they currently were working under an NCC and 22 for those who indicated they previously worked under an NCC used in analysis.

Text Follow-Up Questions

After certain survey questions, respondents were asked a follow-up question that allowed for text input to provide more detail (e.g., how far [in miles] was the geographic restriction of your noncompete clause?). Some of the answers to these questions were outliers (e.g., 150+ miles scope of NCC, moving more than 500 miles due to an NCC) that would have influenced reports of the mean. To reduce the impact of these outliers and help provide a more accurate picture of the responses to these questions, percentiles were calculated for all responses for each question. Responses above the 90th percentile and below the 10th percentile were eliminated and descriptive statistics were calculated based on the remaining data (10% trimmed mean; see Trimmed Mean, n.d.).

Results

Participant Demographics

At first, 923 individuals completed the survey with a total of 890 providing responses that met inclusion criteria and were included in data analysis. Of those who completed the survey, 186 (20.9%) were BCBA-Ds, 422 (47.4%) were BCBAs, 112 (12.6%) were BCaBAs, and 170 (19.1%) were RBTs. A total of 238 (26.7%) indicated they were owners of an ABA business, 408 (45.8%) were employees in a private practice, 167 (18.8%) were employees in a nonprofit, 35 (3.9%) worked in a university setting, and 42 (4.7%) worked in another type of setting. When asked about time working in the field of ABA, respondents were able to enter their response via text. Data on time working in the field of ABA were then recoded into ordinal variables for ease of analysis.

Of the 890 respondents, 803 (90.2%) provided information on how long they had been practicing in the field of ABA. Twenty-two (2.7%) indicated they had worked less than 1 year, 170 (21.2%) had worked 1–2 years, 247 (30.8%) had worked 3–4 years, 202 (25.2%) had worked 6–10 years, and 162 (20.2%) had worked over 10 years in the field (see Table 1). Results for survey items are organized by category and described in more detail below.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Credential | ||

| BCBA-D | 186 | 20.9 |

| BCBA | 422 | 47.4 |

| BCaBA | 112 | 12.6 |

| RBT | 170 | 19.1 |

| Position in ABA | ||

| Owner | 238 | 26.7 |

| Employee in private practice | 408 | 45.8 |

| Employee in nonprofit | 167 | 18.8 |

| Employee at a university | 35 | 3.9 |

| Other | 42 | 4.7 |

| Time in the Field | ||

| Less than 1 year | 22 | 2.7 |

| 1–2 years | 170 | 21.2 |

| 3–4 years | 247 | 30.8 |

| 6–10 years | 202 | 25.2 |

| 10+ years | 162 | 20.2 |

General Prevalence of Noncompete Clauses

In total, 337 (37.9%) of respondents indicated they currently were working under a NCC in their employment contract. Two hundred ninety respondents (32.6%) had worked under a NCC previously, and 263 (29.6%) had never worked under an NCC (see Table 2). Table 3 lists the percentages who reported currently, previously, and never working under an NCC by BACB credential and employment position.

Table 2.

Percentages of respondents reporting noncompete clauses

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, current NCC | 337 | 37.9 |

| Yes, past NCC | 290 | 32.6 |

| No NCC ever | 263 | 29.6 |

NCC = Noncompete clause

Table 3.

Reported prevalence of noncompete clauses in ABA by category

| Yes, Current NCC | Yes, Past NCC | No NCC Ever | |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Credential | |||

| BCBA-D | 101 (54.3%) | 39 (21%) | 46 (24.7%) |

| BCBA | 139 (32.9%) | 148 (35.1%) | 135 (32%) |

| BCaBA | 36 (32.1%) | 56 (50%) | 20 (17.9%) |

| RBT | 61 (35.9%) | 47 (27.6%) | 62 (36.5%) |

| By Employment Position | |||

| Owner/Director | 134 (56.3%) | 55 (23.1%) | 49 (20.6%) |

| Employee in private practice | 149 (36.5%) | 140 (34.3%) | 119 (29.2%) |

| Employee in nonprofit | 46 (27.5%) | 62 (37.1%) | 59 (35.3%) |

| University employee | 7 (20%) | 13 (37.1%) | 15 (42.9%) |

| Other position | 1 (2.4%) | 20 (47.6%) | 21 (50%) |

NCC = Noncompete clause

Results for Those Currently Working under an NCC

Of the respondents who reported that they were currently working under an NCC, 118 (36.9%) indicated they were informed of the NCC during the interview, 134 (41.9%) were informed during contract negotiations, 46 (14.4%) were informed after they accepted the job, and 22 (6.9%) found out about the NCC after they started working with the organization. When asked about the length of work restrictions on their current NCC, 95 (29.9%) indicated restrictions were less than 6 months, 128 (40.3%) indicated restrictions were 7 months to 1 year in length, 72 (22.6%) indicated restrictions were more than 1 year, and 23 (7.2%) indicated they were not sure. A total of 81 (25.7%) respondents indicated a geographic restriction on their NCC, 169 (53.7%) indicated there was no geographic restriction, and 65 (20.6%) indicated they were not sure if there was a geographic restriction. The average distance of reported NCCs for those currently working under one was 42.57 miles (range: 12–100 miles).

When asked why respondents signed an NCC, 60 respondents (17.8%) indicated they felt they had limited viable job options at the time of the offer. A total of 36 (10.7%) indicated they were not fully aware of what NCCs were when they signed their contract. A total of 115 (34.1%) of respondents indicated they thought the job offer was fair with the NCC. A total of 24 (7.1%) indicated they were unaware their contract contained an NCC. A total of 222 (65.9%) indicated they were offered some type of additional compensation for signing their contract with an NCC. A total of 97 (28.8%) indicated that the NCC did not affect their decision to take the job. A total of 15 (4.5%) indicated some other reason (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Responses to survey items for those currently working under an noncompete clause

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| When Were You Informed of The NCC in Your Contract | ||

| During the interview | 118 | 36.9 |

| During contract negotiations | 134 | 41.9 |

| After accepting the job | 46 | 14.4 |

| After starting work at the organization | 22 | 6.9 |

| Length of Postemployment Work Restrictions | ||

| Less than 6 months | 95 | 29.9 |

| 7 months to 1 year | 128 | 40.3 |

| More than 1 year | 72 | 22.6 |

| Not sure | 23 | 7.2 |

| Geographic Restriction on NCC | ||

| Yes | 81 | 25.7 |

| No | 169 | 53.7 |

| Not sure | 65 | 20.6 |

| Reasons for Signing an NCC | ||

| Limited viable employment options | 60 | 17.8 |

| Not fully aware of what an NCC was | 36 | 10.7 |

| Job offer with NCC was fair | 115 | 34.1 |

| Unaware contract contained NCC | 24 | 7.1 |

| Received compensation for signing NCC | 222 | 65.9 |

| NCC did not impact job decision | 97 | 28.8 |

| Other reason | 15 | 4.5 |

NCC = Noncompete clause

Results for Those Previously Working under an NCC

Of the respondents who indicated they previously worked under an NCC, 64 (23%) indicated they worked under one within the previous year, 92 (33.1%) indicated they worked under an NCC within the last 1–2 years, 70 (25.2%) indicated they worked under an NCC 2–3 years ago, and 52 (18.7%) indicated they worked under an NCC more than 3 years ago. Forty-seven (17%) respondents indicated their NCC lasted less than 6 months, 132 (47.7%) indicated the NCC lasted 7 months to 1 year, 70 (25.3%) indicated their NCC lasted more than 1 year, and 28 (10.1%) indicated they were not sure. A total of 82 (29.8%) respondents indicated their NCC had a geographic work restriction, 131 (47.6%) reported no geographic work restriction, and 62 (22.5%) reported they were unsure if their NCC had a geographic restriction. The average distance of reported NCCs for those who previously worked under one was 48.76 miles (range: 10–100 miles).

For respondents who indicated they previously had a NCC, 24 (8.6%) indicated they were informed about the NCC during the interview with the company, 104 (37.4%) were informed during contract negotiations, 113 (40.6%) were informed after they accepted the job offer, and 37 (13.3%) were informed after they started the job. When respondents were asked why they signed a contract with an NCC, 74 (25.5%) indicated they had limited viable job opportunities at the time. A total of 71 (24.5%) indicated the NCC did not affect their decision to take the job. A total of 67 (23.1%) indicated they were not fully aware of what an NCC was when signing their employment contract. A total of 44 (15.2%) indicated they were unaware their employment contract contained an NCC. A total of 35 (12.1%) indicated they thought the job offer including the NCC was fair. A total of 21 respondents (7.2%) provided other answers. Of those who previously signed an NCC, 141 (48.6%) indicated they were offered some type of additional compensation for doing so.

Impact of NCCs on Those Who Previously Worked under One

A total of 159 (57.4%) respondents who previously worked under an NCC stated they had to move to a different geographic location due to work restrictions on their NCC. For respondents who reported moving, the average distance reported was 61.72 miles (range: 3–342 miles). A total of 98 (36.7%) of respondents reported their daily work commute increased as a result of an NCC, 86 (32.2%) reported their daily commute was shorter, and 83 (31.1%) reported it was equal. For respondents who reported an increase in work commute, the average increase was 27.33 miles (range: 3–100 miles). For respondents who reported a decrease in work commute, the average decrease was 27.37 miles (range: 5–150 miles).

When asked about effects on yearly personal income, a total of 118 (44.4%) respondents indicated their yearly income decreased due to restrictions of an NCC, a total of 67 (25.2%) indicated their income increased, and 81 (30.5%) indicated their income was not affected. For those who reported a decrease in income, the average decrease was $5,908 (range: $9–$25,000). For respondents who reported an increase in income, the average increase was $1,965 (range: $4–$10,000). A total of 123 (47.1%) respondents indicated they were involved in some type of litigation (had to hire/retain a lawyer) to deal with the effects of their NCC, with 125 (47.9%) indicating they were not involved in some type of litigation, and 13 (5%) indicating they preferred not to answer. For those who reported being involved in litigation, the average personal cost of the litigation in dollars respondents reported was $1,189 (range: $8–$9,200).

When asked about the impact on their work in the field of ABA, 52 respondents (19.8%) indicated that they completely stopped working in the field of ABA due to the effects of their NCC. A total of 121 (46.2%) respondents indicated they partially stopped working in the field, and 89 (34%) indicated they had not stopped working in the field of ABA. For respondents who reported partial or complete work stoppage, the average duration of the stoppage in months was 11.69 (range: 2–65 months). Thirty-seven (14.2%) respondents indicated that NCCs had a very positive effect on their ability to practice ABA and 55 (21.2%) indicated NCCs had a positive effect on their ability to practice ABA. Seventy-three (28.1%) respondents indicated the NCC had no effect on their ability to practice ABA. In contrast, 57 (21.9%) respondents indicated NCCs had a negative impact on their ability to practice ABA and 38 (14.6%) indicated they believed their NCC had a very negative effect on their ability to practice. One hundred sixty-six (64.3%) respondents who previously worked under an NCC indicated they considered leaving the field of ABA due to the effects of their NCC with 92 (35.7%) indicating they did not consider leaving the field. Finally, a total of 179 respondents (69.6%) indicated they had to turn away potential clients due to the effects of their NCC, and 78 (30.9%) indicated they did not have to turn away clients (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Responses to survey items for those previously working under an noncompete clause

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| When Were You Informed of The NCC in Your Contract | ||

| During the interview | 24 | 8.6 |

| During contract negotiations | 104 | 37.4 |

| After accepting the job | 113 | 40.6 |

| After starting work at the organization | 37 | 13.3 |

| Length of Postemployment Work Restrictions | ||

| Less than 6 months | 47 | 17 |

| 7 months to 1 year | 132 | 47.7 |

| More than 1 year | 70 | 25.3 |

| Not sure | 28 | 10.1 |

| Geographic Restriction on NCC | ||

| Yes | 82 | 29.8 |

| No | 131 | 47.6 |

| Not sure | 62 | 22.5 |

| Reported Reasons for Signing an NCC | ||

| Limited viable employment options | 74 | 25.5 |

| Not fully aware of what an NCC was | 67 | 23.1 |

| Job offer with NCC was fair | 35 | 12.1 |

| Unaware contract contained NCC | 44 | 15.2 |

| Received compensation for signing NCC | 141 | 48.6 |

| NCC did not impact job decision | 71 | 24.5 |

| Other reason | 21 | 7.2 |

| How Recently NCC was in Effect | ||

| Less than 1 year ago | 64 | 23 |

| 1–2 years ago | 92 | 33.1 |

| 2–3 years ago | 70 | 25.2 |

| 3+ years ago | 52 | 18.7 |

| Reported Having to Move to a Different Region Due to a NCC | ||

| Yes | 159 | 57.4 |

| No | 118 | 42.6 |

| Reported Effects on Daily Work Commute Post-NCC | ||

| Increased | 98 | 36.7 |

| Decreased | 86 | 32.2 |

| No Change | 83 | 31.1 |

| Reported Effects on Yearly Income Due to a NCC | ||

| Increased | 67 | 25.2 |

| Decreased | 118 | 44.4 |

| No Change | 81 | 30.5 |

| Reported Being Involved in Litigation/Hired a Lawyer | ||

| Yes | 123 | 47.1 |

| No | 125 | 47.9 |

| Prefer not to answer | 13 | 5 |

| Reported Impact on Work in the Field of ABA | ||

| Partially stopped working | 121 | 46.2 |

| Completely stopped working | 52 | 19.8 |

| Did not stop working | 89 | 34 |

| Reported Effect on Ability to Practice | ||

| Very Positive Effect | 37 | 14.2 |

| Positive Effect | 55 | 21.2 |

| No Effect | 73 | 28.1 |

| Negative Effect | 57 | 21.9 |

| Very Negative Effect | 38 | 14.6 |

| Reported Effect on Practitioners’ Personal Mental Health | ||

| Very Positive Effect | 27 | 10.4 |

| Positive Effect | 73 | 28.1 |

| No Effect | 69 | 26.5 |

| Negative Effect | 52 | 20 |

| Very Negative Effect | 39 | 15 |

| Reported Considered Leaving the Field of ABA | ||

| Yes | 166 | 64.3 |

| No | 92 | 35.7 |

| Reported Having to Turn Away Clients | ||

| Yes | 179 | 69.6 |

| No | 78 | 30.9 |

NCC = Noncompete clause

Effects of NCCs on Mental Health

When respondents were asked about the effects their previous NCCs had on their personal mental health, 27 (10.4%) indicated their NCC had a very positive effect, 73 (28.1%) indicated a positive effect, 69 (26.5%) indicated no effect, 52 (20%) indicated a negative effect, and 39 (15%) indicated a very negative effect.

Responses of Owners on the Use NCCs

One hundred sixty (70.5%) respondents who were owners of ABA organizations indicated that the employment contract in their organization contained an NCC and 67 (29.5%) indicated their contract did not contain an NCC. Of the owners who reported their business contract contained an NCC, 94 (58.8%) indicated clinical supervisors (clinical coordinators, site directors) were made to sign NCCs, 61 (38.1%) indicated BCBAs/BCBA-Ds overseeing or implementing direct service were made to sign NCCs, 25 (15.6%) indicated BCaBAs were made to sign NCCs, and 9 (5.6%) indicated RBTs/technicians were made to sign NCCs. When asked why their employment contracts contained an NCC, 87 (54.4%) of owners who used them indicated NCCs protect against losing trade secrets, 51 (31.9%) indicated NCCs were used to avoid losing clients, 43 (26.9%) indicated NCCs were used to protect against high employee turnover, 36 (22.5%) indicated NCCs were used to prevent former employees from starting a competing business, 12 (7.5%) indicated an NCC was a legal suggestion when the business was created, and 21 (13.1%) indicated that NCCs were used to help the business grow (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Responses to survey items for owners

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Does Your Organizational Contract Contain an NCC? | ||

| Yes | 160 | 70.5 |

| No | 67 | 29.5 |

| Who is Made to Sign an NCC in Your Organization? | ||

| Clinical coordinators/site directors | 94 | 58.8 |

| BCBAs/BCBA-Ds | 61 | 38.1 |

| BCaBAs | 25 | 15.6 |

| RBTs | 9 | 5.6 |

| Reported Reasons for Using NCCs | ||

| To protect trade secrets | 87 | 54.4 |

| To avoid losing clients | 51 | 31.9 |

| To reduce turnover | 43 | 26.9 |

| To prevent employees from starting a business | 36 | 22.5 |

| Legal suggestion when business was created | 12 | 7.5 |

| To help the business grow | 21 | 13.1 |

NCC = Noncompete clause

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of NCCs in the field of ABA and extended previous research by Brown et al. (2020). A slightly higher percentage of respondents indicated they currently worked under an NCC (37.9%) compared to that reported by Brown et al. (33.1%). Seventy percent of respondents in the current study reported having worked under an NCC at some point in their time in the field of ABA. For comparison, a recent national survey of over 11,000 members of the U.S. workforce found that 18% of respondents currently were working under an NCC and 38% had agreed to one in the past (Starr et al., 2021). Implications of these findings, and recommendations for future research and practice, are discussed in greater detail below.

The Need for Informed Practitioners

Over 75% respondents currently working under an NCC indicated they were informed about the organization’s use of an NCC during the interview or during contract negotiation stages. This percentage of respondents was noticeably lower for those who previously worked under an NCC in the past, with about 46% of respondents indicating they were informed about the NCC during these early stages of the employment relationship. To summarize, those who previously worked under an NCC indicated they were told later in the hiring process more often than those who currently were under an NCC. Still, over 20% of respondents who were currently working under an NCC and over 50% of those who previously worked under an NCC reported being informed about the NCC after the job offer or after they started working at the organization. Further, a total of 7.1% of respondents who reported currently working under an NCC and 15.2% who reported working under an NCC in the past reported they were not sure of what an NCC was or were not aware their contract contained one when they signed it.

Brodhead et al. (2018) discussed the importance of the pre-interview and interview process when evaluating organizations and the data obtained here emphasizes the continued importance of practitioners asking organizations about the presence of NCCs during the interview process. ABA practitioners who are seeking employment need to familiarize themselves with the potential benefits and risks of NCCs and what their employment contract means for them. Even if a potential job seeker has limited options, it is still the responsibility of the potential employee to know the possible benefits and risks associated with signing an NCC. Knowing the benefits and drawbacks of NCCs and asking questions can allow practitioners to make more informed decisions during employment negotiations, potentially have the NCCs removed/modified, or negotiate better compensation for signing a contract with an NCC. Having information on NCCs also places the potential employee in a position to negotiate a better contract during the bargaining process. For reference, data from the current survey indicated that only 65% of those currently working under an NCC and 48% of those who did in the past indicated that they received additional compensation for signing their contract with an NCC. In other words, knowledge of NCCs and asking questions early in the hiring process ensures “mutual benefit,” which refers to instances in which both parties benefit from a contractual agreement. Ensuring mutual benefit is important because “instances when only employers benefit from contractual agreements are considered poor practice” (Brodhead et al., 2018, p. 171) and can prevent employees from being taken advantage of by their employers. Potential employee should also ask about the geographic scope of the NCC, its duration, and how they are being compensated within the contract for essentially agreeing to not work for a length of time after leaving an organization.

Ethical Considerations for BACB Certificants Working as Owners

Core Principle 1 in the Ethics Codes for Behavior Analysts (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2020) indicates that behavior analysts should “focus on the long and short term effects of their professional activities” (emphasis added) and to behave “in an honest and trustworthy manner” (BACB, 2020, p. 4). BCBAs who are owners of organizations (and thus beholden to the BACB Code in their professional capacity) should therefore inform prospective employees early in the interview about whether an NCC is part of the employment contract. By not informing potential employees about NCCs early during employment negotiations, prospective employees could potentially be unable to make an informed decision about their job (short-term effects) offer and how an NCC could affect their career (long-term effects). Though prospective employees do have the responsibility to consider how an NCC will affect them in the future, they cannot do so unless they are informed of all elements of their contract. Of course, once signed, BCBAs have an ethical responsibility to follow through on their contractual obligations to the extent to which they are required by law (see also BACB Code Core Principle #3). Therefore, knowing the expectations and elements of an employment contract, especially with regard to NCCs, is crucial.

We acknowledge that many ABA business owners do not have a professional credential or license and are therefore not beholden to an enforceable code of ethics. Here, accreditation bodies (e.g., BHCOE) that clarify the conditions under which NCCs may or may not be appropriate are of value. Still, the absence of a professional credential, license, and/or organizational accreditation does not preclude anyone or anything from making ethical business decisions. Further, because NCCs may be legal business practices does not mean they are ethical business practices. Our findings suggest the use of NCCs in ABA is widespread, and given the negative impacts we describe below, along with the limited (if any) benefits they bring to employees, we call on ABA business owners from all backgrounds to do what is right and end the inappropriate and harmful use of NCCs.

In Table 7 we provide several suggestions for questions practitioners to consider asking of potential employers during the interview process if they are presented with a noncompete clause in their contract. These questions are information seeking and ethics-related questions we have developed based on the obtained results of our study, as well as our collective experiences working in the field of ABA and reviewing employment contracts for ourselves and our supervisees. Our suggestions are intended to serve as a starting point for prospective employees to consider while searching for jobs. We strongly encourage potential employees to seek the advice of mentors and advisors when on the job market, and finally, if a potential employee ever has a question about a contract, we encourage them to seek legal counsel.

Table 7.

Suggested information seeking and ethics questions to ask during an interview

| Information Seeking Questions | Function |

| 1. Does the contract I am expected to sign when joining this organization contain a noncompete clause or other stipulation that prevents me from freely leaving and working in the field of ABA? | 1. Establishes whether the business uses an NCC. |

| 2. Does the contract contain a geographic restriction on where an ex-employee works, time restriction on an ex-employee works, or both? | 2. Allows the potential employee to determine what kinds of work restrictions will be in effect if they agree to an NCC. |

| 3. What is the geographic/time restriction for the NCC? | 3. Allows the potential employee to determine the distance of any future work restrictions if they agree to an NCC. |

| 4. What additional compensation is being offered in excess of regular salary for signing a contract with an NCC? | 4. Allows the potential employee to ascertain whether they are receiving additional salary, benefits, or other type of compensation specifically for signing on with an NCC. |

| 5. Is there a point during my employment the NCC ceases to be in effect? Does it still apply after a promotion or-reclassification (e.g., promotion to BCBA from RBT)? | 5. Allows the potential employee to better understand how the NCC can impact them as they advance within the company, are promoted, or gain a credential. |

| 6. Does the organization provide relocation assistance to practitioners who would have to move from the area to continue working in the field of ABA? | 6. Allows the potential employee to plan if they desire to stop working with the company and are subject to an NCC and/or negotiate this assistance in their contract. |

| Ethics Questions | Relevant BACB Code Principles and Code Standards |

| 1. How does the organization balance the right of clients to receive treatment with the restrictions used on their NCC? | 1. Core Principle 1; Standards 1.03, 1.13, 2.10, and 3.01 |

| 2. If an unforeseen event (e.g., health issues, personal issues, family issues) forced me to stop working in the field, would I still be subject to the requirements of the NCC? | 2. Core Principle 2; Standards 1.03 and 2.10 |

| 3. Why does the organization use NCCs that restrict the ability of an ex-employee to work and not other agreements such as nondisclosure or nonsolicitation agreements? | 3. Core Principles 1, 2, and 3; Standards 1.03 and 2.10 |

| 4. What performance management initiatives does the organization use to encourage employees to stay rather than preventing them from leaving? | 4. Core Principles 1, 2, and 3; Standards 1.03, 1.13 and 2.10 |

Impact on Practitioners

In the current study, we found that more than half of the respondents who previously worked under an NCC indicated they had to move to a different geographic location to work, and over a third indicated their work commute increased. Having to move or commute longer distances to work likely places strain on practitioners in the form of increased transportation costs and decrease in leisure time. Previous research has found links between satisfaction with work commute and overall levels of “happiness” (Olsson et al., 2013).

Geographical restrictions may also reduce the available practitioners in certain locations, and this negative effect could be most pronounced in areas with a high client need where organizations may use NCCs to prevent employees from “jumping ship.” In general, one of the major ways in which NCCs can affect a workforce is by its effect on “geographic worker mobility,” which can broadly be defined as a worker’s ability to find new gainful employment within a field (Halton, 2021). In human service fields such as ABA, reductions in worker mobility/availability are directly tied to client access to service in general. In essence, NCCs can reduce geographic worker mobility within a field, such as ABA, by preventing employees from seeking out new opportunities. In theory, this can lead to fewer job offers to these individuals as well as lower wages, although research is mixed on the topic (Bishara & Starr, 2016; Marx et al., 2015; Starr et al., 2019). Our findings indicate that 66% of respondents reported having to stop working in the field for some duration and 69% reported having to turn away potential clients. Considering the recent increase in the prevalence of ASD to 1 in 44 children (Maenner et al., 2021), the issue of the appropriate use of NCCs in ABA is as critical as ever.

Over 40% of respondents who previously worked under an NCC reported a reduction in personal income and nearly half reported having to hire or retain a lawyer and being involved with litigation regarding their NCC. It is not surprising that over a third of respondents indicated that NCCs had a negative effect on their personal mental health. The potential financial and emotional toll of NCCs on the ABA workforce are especially alarming given the demand for qualified professionals in autism services and the demand for qualified members of the workforce in the United States in general. One related area of particular importance is employee burnout in ABA and the effect this has on the field (see Novack & Dixon, 2019; Plantiveau et al., 2018). It is possible that NCCs may contribute to employee burnout; however, future research is needed to explore this relation further. In any event, our findings highlight the potential ramifications of NCCs and how those ramifications extend well beyond protecting legitimate business interests.

Although Brown et al. (2020) reported high levels of negative opinions on NCCs, the current study found the self-reported effects on practitioners can vary widely and those effects are not uniformly negative. Over 57% of respondents who previously worked under an NCC indicated they did not have to move to a new location due to an NCC and over 60% indicated their commute decreased or was equal to what it was before. About 25% of those who previously worked under an NCC reported their income increased due to the effects of an NCC. Nearly the same percentage of respondents who stated they were involved with litigation (47.1%) indicated they were not involved with litigation (47.9%) and a higher percentage (38%) reported that NCCs had a positive effect on their mental health. As mentioned above, if practitioners become more familiar with NCCs and their possible benefits/drawbacks and discuss them earlier in the employment negotiations, the chance of adverse outcomes for practitioners due to NCCs may be reduced and the opportunity for fair negotiation may be maximized. Put another way: having skills to ask and negotiate about NCCs can reduce negative impacts to those who would be negatively affected, which the data obtained here suggest this positive impact would be sizable. However, future research is needed in order to explicitly evaluate this relationship.

Impact on Registered Behavior Technicians

A total of 35.9% of RBT respondents indicated they were currently working under an NCC and 27.6% indicated they worked under one previously. This finding is alarming, because the RBT credential is a paraprofessional certification for individuals who provide ABA services only under the direction of a BCaBA or BCBA. Although RBTs cannot practice independently, they deliver the services designed by BCBAs and BCaBAs and currently outnumber BCBAs 2 to 1 in the workforce (BACB, 2021a). Further, 59% of the RBTs who previously worked under an NCC reported they stopped working (40.5% partially, 19% completely) in the field of ABA and nearly 70% reported work restrictions that lasted 7 months or more.

The reported prevalence of NCCs on RBTs is alarming for several reasons. First, RBTs cannot “compete” in the same way a BCaBA or BCBA can after leaving an organization. RBTs cannot carry caseloads, deliver services, or bill insurance on their own. Without a supervising behavior analyst (e.g., a BCBA), an RBT cannot engage in the practice of ABA under the scope of that RBT credential (BACB, 2021c). RBTs represent the largest portion of the behavioral workforce and provide a significant portion of the behavior analytic services designed by BCBAs. Limiting such a large and vital portion of the workforce has the potential for negative effects in the field of ABA in terms of readily available trained staff. Limiting an already strained workforce can contribute to poor service outcomes for clients, increased training costs for organizations, and reduced access to services for clients and their families.

In addition, RBTs likely receive the least amount of financial compensation of all categories of survey respondents, and we hypothesize low financial compensation may positively correlate with training and education. Thus, limiting their ability to change employers within the field of ABA may make them more likely to seek alternative career options than professionals with a bachelors or master’s-level credential because RBTs have not yet invested significant time and effort into undergraduate and graduate degree programs and hours of supervised fieldwork. Given the demand for services, workplace shortages, and unmeasurable value that RBTs bring to the profession, we see no reason why RBTs should sign an NCCs unless under unique and demanding circumstances.

Reported Impact on the Practice of ABA

A total of 66% respondents who previously worked under an NCC indicated they had to stop working in ABA either partially or completely. Over 20% indicated the work restriction on their NCC were over 1 year in duration and nearly 70% of respondents indicated having to turn away potential clients after they left their position with an NCC. These findings are incredibly concerning, again given the demand for behavioral services and the potential financial and emotional impacts of NCCs. In fact, 64% of those who previously worked under an NCC reported considering leaving the field of ABA altogether. We interpret our findings as providing preliminary support that NCCs are contributing to a lack of qualified practitioners in the field directly through work restrictions on BCBAs and RBTs. However, future research on the effects of NCCs on the field of ABA is needed to fully understand their impacts on employee retention.

A Complex Situation

On the surface, it would seem the use of NCCs in the field of ABA boils down to balancing the rights of practitioners’ seeking jobs and owners/organizations who find them necessary to protect their business interests. A more complex issue is at hand, though. Although practitioners and owners can do more to be more transparent and inform themselves about NCCs in the field, the question still exists as to whether NCCs are appropriate in human service fields such as ABA. Even if employees negotiate better employment or benefits for signing NCCs or owners are transparent about their use of NCCs, the question remains as to whether NCCs are in the best interest of current and potential clients and families.

The BACB Code defines stakeholders as “An individual, other than the client, who is affected by and invested in the behavior analyst’s services” (p. 3). Future clients and families in a geographical area in which one resides and/or works are stakeholders who are affected by organizational action (e.g., using NCCs). Given that NCCs can stifle economic growth, even those without direct ties to or interests in ABA services are also stakeholders in organizational decisions about whether to use NCCs (see Epstein & Hanson, 2021, and Liautaud, 2021, for further discussion). In a sense, the use of NCCs in the field of ABA does allow for the restriction of practice to come to under the discretion of practitioners and businesses who use NCCs in hiring. But given the BACB’s definition of stakeholder, and how the term is widely understood in business ethics, limiting an analysis of the impact of NCCs to the employer and employee is incomplete at best and harmful at worst.

To be clear, the BACB and state licensing boards’ job is to regulate practice of ABA and not the practice of businesses. ABA organizations can, however, take steps to reduce the risk to clients where the practice of business interferes with the practice of the respective profession(s) they oversee, as well as the stakeholders affected by those decisions. The principle of “Justice” outlined in the current Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct from the American Psychological Association (APA) urges practitioners to “recognize that fairness and justice entitle all persons to access to and benefit from the contributions of psychology and to equal quality in the processes, procedures, and services being conducted by psychologists” (APA, 2017). This sentiment is echoed in the BACB core principle “Benefit Others” that guides practitioners to protect “the welfare and rights of clients above all others” (BACB, 2020, p. 4) Taking steps to limit the use of NCCs would be consistent with this principle and with the actions of some states (e.g., Oregon and Illinois; see BHCOE, 2020) have taken already.

Business owners in the current survey indicated that protecting trade secrets, preventing lost clients, and reducing employee turnover were the three top reasons for using NCCs. Brown et al. (2020) made several suggestions for alternative employment arrangements that can help businesses. Examples include nondisclosure agreements (NDA) and nonsolicitation agreements (NSA), which are tools available to business owners that can legally prohibit the disclosure of trade secrets and stop previous employees from trying to take clients away, respectively. Legal “functional alternatives” for the reasons practitioner/owners reportedly use NCCs do exist. Given the increased prevalence of ASD, demand for appropriately trained practitioners, and effects reported in this survey, and practitioner/owner reasons for using NCCs, NDAs and NSAs seem more appropriate.

It is true that contingencies may vary and potentially compete as a function of the presence or absence of a professional credential, license, and/or organizational accreditation. However, it is important to emphasize that the absence of a professional credential, license, and/or organizational accreditation does not preclude anyone or anything from making ethical business decisions. Further, because NCCs may be a legal business practice in some jurisdictions does not mean they are an ethical business practice. Our findings suggest the use of NCCs in ABA is widespread, and given the negative impacts we describe in this article, along with the limited (if any) benefits they bring to employees, we call on ABA business owners from all backgrounds to come together and do what is right and end the inappropriate and harmful use of NCCs.

Until more formal guidance can be provided to behavior analysts to complement guidance already provided by accreditation agencies (e.g., BHCOE), we provide initial suggestions for questions to ask during the interview process that concern NCCs. These recommendations are depicted in Table 7 and provide suggestions for information seeking and ethics-related questions practitioners could ask of potential employers during the interview process.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Survey research will always be limited in that respondents report their own experiences, which are commonly subject to bias (Slattery et al., 2011). The current survey used general questions that allowed respondents to answer categorically. For instance, knowing the reasons someone indicated that an NCC had a very positive or negative effect on them would be important for future research. The current study reported data on the extent or degree on some of the answers from respondents such as how much income increased after a leaving a position with an NCC. However, some text-based responses were variable and required systematic removal of outliers; though data cleaning is a common process used in survey research (see Van den Broeck et al., 2005), our results should be viewed with this potential limitation as context. That said, some of the text responses from participants were exceptionally concerning. For example, when asked about the geographic restriction of their NCC, responses such as “the entire world-no joke,” “the entire island of Maui,” “every contiguous county to where I lived,” and “the entire state” were provided. Several other respondents reported NCC distances more than 200 miles, and these were excluded from analysis due to being an outlier. If these reports are accurate, it would appear NCCs are being abused in the field (though future research is needed to confirm this finding).

The current study did not collect geographic data on respondents. Collecting data on where NCCs are most prevalent would allow for trends to be observed in where NCCs are use most as well as where they have the greatest impact on clients. Geographical data could also allow to see how NCCs are used in underserved areas (see Drahota et al., 2020, and Yingling et al., 2021, for specific examples), which could allow for researchers and policy makers in these locations to better understand how NCCs help or hurt access to service in those areas.

Despite the above limitations, this survey took several important steps in the analysis of NCCs in the field of ABA. This survey distinguished between those who currently work under an NCC, surveyed RBTs, and assessed the reported impact of these clauses on practitioners personally and professionally, expanding upon the method and results reported by Brown et al. (2020). Although personal benefits of NCCs were reported for some respondents, it is a matter of concern that a percentage reported having to stop working in the field, being involved in litigation, considered leaving ABA altogether, and turning away clients.

In Table 7 we provide concrete recommendations for questions practitioners can ask during an interview in order to further aid in their assessment of an organization’s use of NCCs based on the preliminary results of this study. To summarize, the main concern with NCCs in the field of ABA is that NCCs can reduce ABA practitioners’ availability to clients in need. NCCs are also costly to ABA practitioners in terms of time, money, and mental health. We understand this issue is complex and involves an interplay among the rights of clients, practitioners, and business owners. It is hoped that the data obtained here will allow for a more complete analysis and discussion of NCCs in ABA. A complete analysis might allow policy makers a chance to identify and solve potential problems associated with the use of NCCs in ABA to maximize the benefit to all parties involved.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This project received approval from Youngstown State University’s Institutional Review Board (091-21).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

We acknowledge that organizations are not organisms, and therefore cannot behave. However, we have chosen to use this rhetorical structure throughout the article for the sake of brevity and readability.

Kristopher J. Brown acknowledges Mary Brown, MS, and Stephen Flora, PhD, for their early input and feedback on survey items.

This article was updated to correct errors introduced into the income ranges in the section "Impact of NCCs on Those Who Previously Worked under One." The errors were introduced during production and the authors are not responsible.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/8/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40617-022-00724-6

References

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beh HG. Non-compete clauses in physician employment contracts are bad for our health. Hawaii Bar Journal. 2011;14(13):79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ethics-Code-for-Behavior-Analysts-210902.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2021a). BACB certificant data. https://www.bacb.com/bacb-certificant-data/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2021b). US employment demand for behavior analysts: 2010–2020. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BurningGlass2021_210126.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2021c). RBT registered behavior technician handbook.https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/RBTHandbook_220112.pdf

- Behavioral Health Center of Excellence. (May, 2020). Position statement on the use of non-compete agreements with applied behavior analysis workers. https://www.bhcoe.org/project/non-compete-agreements-with-applied-behavior-analysis-workers/

- Behavioral Health Center of Excellence. (n.d.). BHCOE accreditation standards. https://www.bhcoe.org/standards/

- Bishara ND, Starr E. The incomplete noncompete picture. Lewis & Clark Law Review. 2016;20:497–546. [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT, Quigley SP, Cox DJ. How to identify ethical practices in organizations prior to employment. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(2):165–173. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0235-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KJ, Flora SR, Brown MK. Noncompete clauses in applied behavior analysis: A prevalence and practice impact survey. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13(4):924–938. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota A, Sadler R, Hippensteel C, Ingersoll B, Bishop L. Service deserts and service oases: Utilizing geographic information systems to evaluate service availability for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2020;24:2008–2020. doi: 10.1177/1362361320931265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein MC, Hanson KO. Rotten: Why corporate misconduct continues and what to do about it. Lanark Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Executive Order No. 14036, (July 9, 2021).

- Halton, C. (2021, July 23). Geographical labor mobility. Investopedia.https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/geographical-mobility-of-labor.asp

- Horner RH, Sugai G. School-wide PBIS: An example of applied behavior analysis implemented at a scale of social importance. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(1):80–85. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntoon K, Stacy J, Cioffi S, Swartz K, Mazzola C, Profitt C, Adogwa O. The enforceability of noncompete clauses in the medical profession: A review by the Workforce Committee and the Medicolegal Committee of the Council of State Neurosurgical Societies. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(6):1085–1090. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liautaud S. The power of ethics: How to make good choices in a complicated world. Simon & Schuster; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., … & Cogswell, M. E. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 70(11), 1. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/ss/pdfs/ss7011a1-H.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Makrygianni MK, Gena A, Katoudi S, Galanis P. The effectiveness of applied behavior analytic interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analytic study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2018;51:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marx M, Singh J, Fleming L. Regional disadvantage? Employee non-compete agreements and brain drain. Research Policy. 2015;44(2):394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2014.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Novack MN, Dixon DR. Predictors of burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover in behavior technicians working with individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2019;6(4):413–421. doi: 10.1007/s40489-019-00171-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson LE, Gärling T, Ettema D, Friman M, Fujii S. Happiness and satisfaction with work commute. Social Indicators Research. 2013;111(1):255–263. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashkov, V. M., & Harkusha, A. О. (2019). Enforceability of non-Compete agreements in medical practice: Between law and ethics. Wiadomości Lekarskie, 72(12), 2421–2426. 10.36740/WLek201912201 [PubMed]

- Peters-Scheffer N, Didden R, Korzilius H, Sturmey P. A meta-analytic study on the effectiveness of comprehensive ABA-based early intervention programs for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(1):60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plantiveau C, Dounavi K, Virués-Ortega J. High levels of burnout among early-career board-certified behavior analysts with low collegial support in the work environment. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2018;19(2):195–207. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2018.1438339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roane HS, Fisher WW, Carr JE. Applied behavior analysis as treatment for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;175:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery EL, Voelker CC, Nussenbaum B, Rich JT, Paniello RC, Neely JG. A practical guide to surveys and questionnaires. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2011;144(6):831–837. doi: 10.1177/0194599811399724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. B. (2021). Ending physician noncompete agreements—Time for a national solution. JAMA Health Forum, 2(12).10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Starr E, Frake J, Agarwal R. Mobility constraint externalities. Organization Science. 2019;30(5):961–980. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2018.1252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starr E, Prescott JJ, Bishara N. Noncompete agreements in the us laborforce. Journal of Law and Economics. 2021;64(1):53–84. doi: 10.1086/712206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmed mean. (n.d.). Statistics.com: Data science, analytics & statistics courses. https://www.statistics.com/glossary/trimmed-mean/

- Van den Broeck J, Cunningham SA, Eeckels R, Herbst K. Data cleaning: Detecting, diagnosing, and editing data abnormalities. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2(10):e267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virués-Ortega J. Applied behavior analytic intervention for autism in early childhood: Meta-analysis, meta-regression and dose–response meta-analysis of multiple outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(4):387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder DA, Austin J, Casella S. Applying behavior analysis in organizations: Organizational behavior management. Psychological Services. 2009;6(3):202–211. doi: 10.1037/a0015393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yingling, M. E., Ruther, M. H., Dubuque, E. M., & Mandell, D. S. (2021). County-level variation in geographic access to board certified behavior analysts among children with autism spectrum disorder in the United States. Autism, 25(6), 1734–1745. 10.1177/13623613211002051 [DOI] [PubMed]