Abstract

The E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin plays neuroprotective functions in the brain and the deficits of parkin’s ligase function in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is associated with reduced survival of dopaminergic neurons. Thus, compounds enhancing parkin expression have been developed as potential neuroprotective agents that prevent ongoing neurodegeneration in PD environments. Besides, iron chelators have been shown to have neuroprotective effects in diverse neurological disorders including PD. Although repression of iron accumulation and oxidative stress in brains has been implicated in their marked neuroprotective potential, molecular mechanisms of iron chelator’s neuroprotective function are largely unexplored. Here, we show that the iron chelator deferasirox provides cytoprotection against oxidative stress through enhancing parkin expression under basal conditions. Parkin expression is required for cytoprotection against oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells with deferasirox treatment as confirmed by abolished deferasirox’s cytoprotective effect after parkin knockdown by shRNA. Similar to the previously reported parkin inducing compound diaminodiphenyl sulfone, deferasirox-mediated parkin expression was induced by activation of the PERK-ATF4 pathway, which is associated with and stimulated by mild endoplasmic reticulum stress. The translational potential of deferasirox for PD treatment was further evaluated in cultured mouse dopaminergic neurons. There was a robust ATF4 activation and parkin expression in response to deferasirox treatment in dopaminergic neurons under basal conditions. Consequently, the enhanced parkin expression by deferasirox provided substantial neuroprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced oxidative stress. Taken together, our study results revealed a novel mechanism through which an iron chelator, deferasirox induces neuroprotection. Since parkin function in the brain is compromised in PD and during aging, maintenance of parkin expression through the iron chelator treatment could be beneficial by increasing dopaminergic neuronal survival.

Keywords: Parkin induction, Parkinson’s disease, Dopaminergic cell protection, Iron chelator, Deferasirox, ER stress

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease is one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders with a characteristic loss of midbrain dopaminergic neurons which is associated with accumulating oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and α-synuclein aggregation [1–3]. Several mutations on the E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin, encoded by PARK2, and the resultant dysfunction of its ligase activity is thought to be responsible for the pathogenesis of autosomal recessive PD [4, 5]. Moreover, post-translational modifications such as tyrosine phosphorylation and S-nitrosylation [4, 6–8] on parkin under pathological conditions of sporadic PD can also result in reduced parkin ligase activity. Recently, it was also shown that parkin expression is downregulated during aging which is the most significant risk factor for neurodegenerative disease [9]. Physiological parkin activity is critical in the maintenance of diverse biological processes via regulating polyubiquitination and proteasomal clearance of many parkin’s substrates, as such dysfunctional parkin can lead to the accumulation of toxic substrates which contribute to poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1)-dependent cell death (Parthanatos) [10–12], dysfunction of mitochondrial biogenesis [13, 14] and defective mitophagy [15, 16]. In this regard, understanding regulators of parkin activity or expression is imperative as it would provide an insight into a therapeutic strategy through replenishing parkin expression and thereby preventing pathological biological events mediated by parkin substrates accumulation in PD.

To increase the parkin expression, analysis of parkin promoter and studies on the mechanisms by which this promoter is regulated have been conducted [9, 17, 18]. High throughput screening has been conducted to find potential drugs that can increase the expression of parkin. Recently it was reported that hydrocortisone (a glucocorticoid) can lead to the induction of parkin expression levels via the cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) pathway [18]. The CREB pathway can be activated by glucocorticoid receptor bound to a stress hormone corticosteroid. Phosphorylated-CREB acts on the parkin promoter to increase the expression level of parkin [18]. In addition to the previously identified activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) pathway through which parkin expression is induced by diaminodiphenyl sulfone, there seems to be multiple signaling pathways that can be targeted to improve parkin expression thereby enhancing dopaminergic neuronal survival against the pathological environment in PD [9].

Iron is involved in essential physiological processes, such as mitochondrial respiration in neurons of the central nervous system. Therefore, iron homeostasis in nerve cells whose iron concentration has changed due to disease is very important for the neurons [19, 20]. However, it has been reported that excessive accumulation of iron in neurons causes a wide range of serious neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Multiple sclerosis, and PD. The accumulation of iron induces oxidative stress in neurons, leading to cytotoxicity and protein aggregation [21–23]. Previous studies have confirmed that iron chelator prevents cytotoxicity induced by oxidative stress [22, 24–26] suggesting that oxidative stress and iron accumulation have a reciprocal pathological interaction. The maintenance of p21 expression which regulates apoptosis has been suggested as a molecular mechanism of iron chelator’s cytoprotective funciton [26]. However, molecular mechanisms of the cytoprotective function especially in neurons afforded by iron chelation are largely unexplored.

Our group has previously screened potential neuroprotective compounds using a parkin promoter-luciferase reporter cell line and confirmed that several compounds including deferasirox, an iron chelator, have properties to induce parkin expression [18]. In this study, we confirmed that deferasirox increases parkin expression and enhances cell survival against oxidative stress. Deferasirox-stimulated parkin expression contributed to its cytoprotective function in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Mechanistically, we showed that parkin expression by deferasirox is mediated by mild endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced ATF4 signaling pathway that has been previously shown to contribute to parkin transcription. Finally, deferasirox treatment in primary cultured mouse dopaminergic neurons stimulated the ATF4-parkin pathway with concomitant cytoprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine induced neurotoxicity, suggesting its potential therapeutic value in PD.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

Deferasirox (Cat# sc-207,509) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The Primary antibodies used in this study were: mouse Parkin (Prk8) monoclonal antibody (Western blot, cat# 4211, Cell signaling Technology), rabbit Parkin polyclonal antibody (Immunofluorescence, cat# 2132, Cell signaling Technology), rabbit pPERK polyclonal antibody (cat# 3179, Cell signaling Technology), rabbit PERK polyclonal antibody (cat# 5683, Cell signaling Technology), rabbit ATF4 polyclonal antibody (cat# sc-200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The dilution rate of the above antibodies is 1:5,000. The secondary antibodies used for Western blot were: goat anti-mouse IgG polyclonal antibody (HRP) (cat# GTX213111-01, GeneTex), goat anti-rabbit IgG polyclonal antibody (HRP) (cat# GTX213110-01, GeneTex), HRP-conjugated beta-actin mouse antibody (cat# A3854, Sigma-Aldrich). The dilution rate of the goat anti-mouse IgG polyclonal antibody (HRP), goat anti-rabbit IgG polyclonal antibody (HRP) is 1:5,000 and that of HRP-conjugated beta-actin mouse antibody is 1:10,000.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cells (parkin reporter HEK-293T cell line has been described previously [18]) and SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC CRL-2266, generous gift from Dr. Yun Il Lee from DGIST) were grown in culture media composed of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics (cat# P4333, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were grown in humid incubators that were maintained at 95% air / 5% CO2. For transfection, SH-SY5Y cells were passed to 6-well plates at a cell density of 1 × 10^6 cells/well. Cells were transfected by X-tremeGENE HP transfection reagent (cat# 6,366,236,001, Roche) 16 ~ 18 h after plating in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (DNA: X-tremeGENE = 1:1 ratio). After 48 h, the cells were harvested and lysated for sampling to proceed to western blot analysis. For cell viability analysis, SH-SY5Y cells were passed to 12-well plates at a cell density of 0.5× 10^6 cells/well.

Luciferase assay

Stable reporter cell lines (Parkin-Luc-HEK-293T) were harvested after treatment with each compound. Cell lysates were analyzed for firefly luciferase activity using a microplate luminometer (Berthold Technologies) and a luciferase reporter analysis system (Promega, Madison, WI). The negative group was treated with 0.1% DMSO. After chemical treatment, the luciferase activity value was normalized to the value of DMSO control.

Real-time quantitative PCR

To extract total mRNA, QIAzol Lysis buffer was used and DNase I treatment was included to prevent DNA contamination. For cDNA synthesis, iScript cDNA synthesis kit (cat# 1,708,891, Bio-RAD) was used, cDNA was obtained from total mRNA (1.5 µg). Ct values of the target gene were measured with SYBR green-based RT (real-time)-PCR using a Real-Time PCR system (Quantstudio 6 flex, Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA expression levels of each gene were obtained by the ΔΔCt method using GAPDH as a housekeeping gene that serves as an internal loading control. The manufacturer’s protocol was applied to the PCR SYBR green master mix (cat# 4,309,155, Applied Biosystems). The primer used for RT (real time)-PCR was as follows: GAPDH (Forward): AAATCCCATCACCATCTTCCAG; GAPDH (Reverse): AGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTCT; Parkin (Forward): CAGCAGTATGGTGCAGAGGA; Parkin (Reverse): TCAAATACGGCACTGCACTC.

Trypan blue cell viability assay

Each SH-SY5Y cell was seeded at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells in a well.

Following transfection with target plasmids, SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in DMEM media containing 10% FBS, and antibiotics, and then cells were transfected to target plasmids for 2 days. After hydrogen peroxide or vehicle control treatment, SH-SY5Y cells were harvested. Harvested cells were blended with the same volume of 0.4% trypan blue (wt/vol) and dyed at room temperature for 1 min. The number of dead and living cells was measured with an automatic cell counter (Countess, Invitrogen).

Dopaminergic neuron culture

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of Sungkyunkwan University (Approval number: SKKUIACUC2022-07-41-1) and were conducted in accordance with all applicable international guidelines. ICR mice were purchased from Orient Co. (Suwon, Korea) for use in the neuronal progenitor cells (NPC) isolation and culture. NPCs were obtained from the ventral midbrain dissected from the ICR mouse embryo (E10-12) as previously described. NPCs extracted from VM were plated in pre-coated culture dishes with a coating solution in DW containing 30 µg/ml poly-L-ornithine and 2 µg/ml fibronectin (overnight). For the proliferation of NPCs, completed N2 media including b27 supplement (Gibco), 5 µg/ml insulin, 20 ng/ml bFGF (Basic fibroblast growth factor, R&D systems), and 20 ng/ml EGF (Epithelial growth factor, R&D systems) was used. During the three-day NPC proliferation period, the completed N2 media was refreshed every day. NPCs were separated by pipetting in HBSS buffer and transferred to newly prepared pre-coated culture plates. To differentiate NPC into dopamine cells, NPC is differentiated for approximately 7 days under the same conditions using N2 medium for differentiation containing ascorbic acid (0.2 mM, Sigma), insulin, b27 supplement.

Immunofluorescence

Differentiated dopamine cells are fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then blocked by 20% Goat serum (cat# 01-6201, Invitrogen) in 0.1% Triton X-100 (sigma) for 1 h (room temperature) in a shaker. Dopamine cells were then incubated with primary antibodies against proteins of interest at 4 ° C overnight. Then, the primary antibodies be removed and cells were washed twice with PBS. To fluorescence label the primary antibody, the secondary antibody was attached for 1 h, followed by DAPI staining and then the coverslips were mounted by Immu-Mount (cat# 9,990,402, Fisher Scientific). Fluorescent images were observed using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Microscope Axio Imager.M2).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for at least three independent experiments. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for comparison of two groups or analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with Tukey post hoc analysis for comparison of three or more groups were used to assess statistical significance. Assessments with a P value of 0.05 were considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism v. 5.03 (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the preparation of all plots and statistical analyses.

Results

Iron chelator, deferasirox activates parkin promoter and increases parkin expression

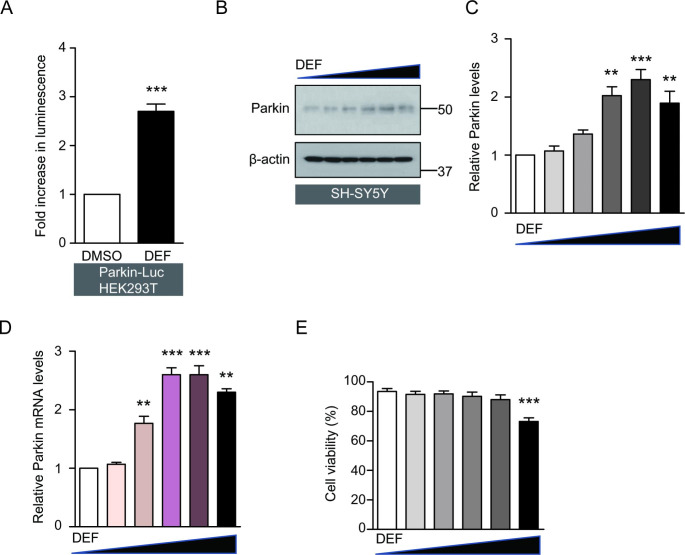

To confirm that deferasirox could induce parkin promoter activity, we used the stable reporter cell line (Parkin-Luc-HEK-293T) containing luciferase construct with parkin promoter element (three repeats of CREB/ATF4 binding motifs) [17, 18]. This stable cell line was established in a previously published study [18]. Compared to the DMSO treatment (control group), deferasirox treatment increased the parkin promoter activity in the stable reporter HEK-293T cell line by more than two folds (Fig. 1 A). To examine the deferasirox’s potential effect on parkin expression in neuroblastoma cell lines, we conducted experiments with SH-SY5Y cells. The SH-SY5Y cells were treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of deferasirox (0, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100 µM). The results showed that parkin mRNA and protein levels increased up to 50 µM (Fig. 1B, C, D) in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment with a dose of 100 µM deferasirox, parkin mRNA, and protein expression was slightly reduced as compared with treatment with a dose of 50 µM, although the parkin expression level was still higher when compared with DMSO treatment. Apart from a high dose of deferasirox (100 µM) which showed mild toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells, the other concentrations had no cytotoxic effect in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Deferasirox increases parkin expression. (A) Parkin promoter activity regulation by deferasirox (DEF) treatment (10 µM, 24 h) in HEK-293T parkin reporter cells (Parkin-Luc-HEK-293T), determined by luciferase assay (n = 3 per group). (B) Representative western blot of parkin protein expression in SH-SY5Y cells treated with increasing concentrations of deferasirox (0, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100 µM, 24 h). (C) Quantification of relative parkin protein levels in each treatment group normalized by β-actin internal loading control (n = 3, right panel). (D) Quantification of relative parkin mRNA levels in SH-SY5Y cells treated with increasing concentrations of deferasirox (0, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100 µM, 24 h), determined by real-time RT PCR (n = 3). GAPDH levels were used as an internal loading control for normalization. (E) Trypan blue exclusion assessment of cell viability for SH-SY5Y cells treated with increasing concentrations of deferasirox (0, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100 µM, 24 h) (n = 3). Quantified data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test (A) and ANOVA test followed by Tukey post hoc analysis (B, C, D). The comparison was made with DMSO vehicle treatment

Parkin is required for the deferasirox-mediated cytoprotective effect

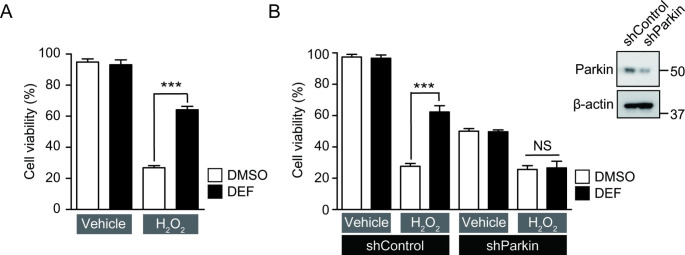

According to the previous studies [27], iron chelator has a protective effect against oxidative stress. Since deferasirox treatment induced cytoprotective E3 ligase parkin expression in SH-SY5Y cells, we sought to determine whether the cytoprotective effect against H2O2-induced oxidative stress was dependent upon parkin induction. To verify whether deferasirox treatment has a cell-protective effect on SH-SY5Y cells against oxidative stress, a cell viability experiment was conducted by trypan blue exclusion assay. Cell survival improved from 30 to 60% after deferasirox pretreatment (10 µM, 24 h) under oxidative stress conditions (1 mM H2O2 for 16 h) in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2 A). Cell survival enhancement effect by deferasirox was dependent on induced parkin expression because shRNA-mediated parkin knockdown abolished the cytoprotective effect of deferasirox under H2O2 stress (Fig. 2B). Cell viability was markedly reduced with shRNA-mediated parkin knockdown even without oxidative stress (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the parkin knockdown experiment clearly indicates that parkin expression is essential in mediating the cytoprotective function of the iron chelator deferasirox.

Fig. 2.

Deferasirox-mediated cytoprotection against oxidative stress is dependent on parkin expression. (A) Assessment of cytoprotection effects exerted by deferasirox treatment (10 µM, 24 h) in SH-SY5Y cells challenged with hydrogen peroxide (1 mM, 16 h), determined by trypan blue exclusion assay (n = 6). (B) Assessment of cell viability in SH-SY5Y cells with DMSO, or deferasirox treatment (10 µM, 24 h) in the background of parkin knockdown by shRNA transient transfection (shParkin, 24 h) or shRNA to DsRed as a control (shControl) (n = 6). Oxidative stress was given to the indicated groups by treating SH-SY5Y cells with hydrogen peroxide (1 mM, 16 h). Knockdown of parkin protein by shParkin transfection to SH-SY5Y cells was confirmed by representative western blot on the right upper side. Quantified data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. ***p < 0.001, ANOVA test followed by Tukey post hoc analysis (A, B). NS, nonsignificant

Deferasirox induces parkin expression via ATF4 signaling pathway

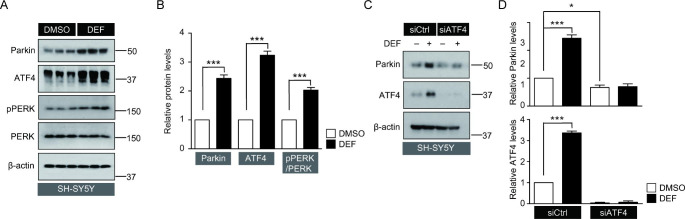

Next, we investigated the molecular mechanisms through which deferasirox induces parkin expression. Parkin promoter information has been revealed in the previous studies [17] and contains an ATF4/CREB binding motif. Several studies have confirmed that mild endoplamic reticulum (ER) stress-induced ATF4 activation induces parkin expression. Consistent with these reports, in the present study, deferasirox treatment led to the activation of mild ER stress-induced signaling pathways such as PERK phosphorylation and ATF4 induction (Fig. 3 A, B). There was a concomitant increase in parkin expression along with activation of the PERK-ATF4 pathway (Fig. 3 A, B). To determine whether ATF4 expression was required for deferasirox-induced parkin expression in this condition, a small interfering RNA (siRNA) was used to reduce endogenous ATF4 expression in SH-SY5Y cells. siATF4 transfection effectively reduced endogenous ATF4 expression and consequently suppressed deferasirox-induced ATF4 upregulation effectively (Fig. 3 C, D). Knockdown of ATF4 by siRNA prevented deferasirox-induced parkin expression (Fig. 3 C, D), and thus, it was confirmed that deferasirox-induced parkin expression was mediated by ATF4 activation in SH-SY5Y cells. In addition, knockdown of endogenous ATF4 by siRNA decreased basal parkin expression (Fig. 3 C, D), suggesting that ATF4 activity might contribute to maintaining parkin expression under basal conditions.

Fig. 3.

Parkin expression in response to deferasirox is mediated by PERK-ATF4 activation. (A) Western blot analysis of parkin, ATF4, phosphorylated PERK (pPERK), and PERK expression in SH-SY5Y cells treated with deferasirox (10 µM, 24 h) or DMSO as a vehicle. (B) Relative expression levels of parkin and ATF4 normalized by β-actin internal loading control. Relative pPERK levels were normalized to total PERK levels (n = 3 per group). (C) Representative western blots of parkin and ATF4 expression in SH-SY5Y cells treated with deferasirox (10 µM, 24 h) or DMSO, following transient transfection with small interfering RNA to ATF4 (siATF4) or scrambled siRNA as control (siCtrl, 24 h). (D) Quantification of relative parkin or ATF4 expression levels in each experimental group normalized to β-actin loading control (n = 3). Quantified data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. ***p < 0.001, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test (B), and ANOVA test followed by Tukey post hoc analysis (D)

Deferasirox activates ATF4-parkin pathway and increases dopaminergic neuronal survival against oxidative stress

In addition to the above-mentioned experiments on the neuroblastoma cell line, a primary dopaminergic neuron culture was used to assess the neuronal protective effect of deferasirox against oxidative stress. To perform primary dopamine neuron culture, we proliferated and differentiated neural precursor cells from the ventral midbrain of mouse embryos into dopamine neurons as previously described [28]. Efficient differentiation into dopaminergic neurons was confirmed by a positive immunofluorescence signal of dopamine neuron marker, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (Fig. 4 A). The expression levels of parkin and ATF4 in TH positive dopaminergic neurons were monitored by immunofluorescence. Deferasirox-treated TH-positive dopamine neurons showed more than three folds increase in immunofluorescence intensities of both parkin and ATF4 compared to the control group (Fig. 4 A, B). We subsequently examined whether parkin-inducing deferasirox exhibits a dopaminergic neuroprotective effect against 6-OHDA-induced oxidative stress. TUNEL assay was performed to evaluate the dopaminergic neuronal death, and based on the BrdU-positive signal analysis, we verified that deferasirox largely prevented the 6-OHDA-induced dopaminergic neuronal death (Fig. 4 C, D).

Fig. 4.

Deferasirox treatment leads to ATF4/parkin expression and cytoprotection against 6-OHDA in cultured mouse dopaminergic neurons. (A) Representative immunofluorescence of ATF4 and parkin in cultured mouse dopaminergic neurons treated with deferasirox (10 µM, 24 h) or DMSO as a vehicle. Dopaminergic neurons were labeled with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-specific antibodies. The ATF4 and parkin signals are pseudo-colored for original red fluorescence. Scale bar = 30 μm. (B) Quantification of immunofluorescence intensities of ATF4 or parkin in TH-positive dopaminergic neurons that were treated with deferasirox (10 µM, 24 h) or DMSO as a vehicle (n = 25–33 cells from 3 slides per group). (C) Representative TUNEL imaging for dopaminergic neurons of deferasirox (10 µM, 24 h) or DMSO treatment followed by challenging with 6-OHDA (70 µM, 16 h). The BrdU-Red signal is pseudo-colored for original red fluorescence. Scale bar = 300 μm. (D) Quantification of BrdU-positive cell ratio in the indicated experimental groups (n = 21–34 cells from 3 slides per group). Quantified data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. ***p < 0.001, ANOVA test followed by Tukey post hoc analysis (B, D)

Discussion

In this study, we first showed that the iron chelator, the deferasirox-mediated cytoprotective effect is largely mediated by the neuroprotective E3 ligase parkin expression. Although deferasirox is an iron-chelating agent commonly used to remove iron in patients with excess iron due to blood transfusion [29], beneficial effects of deferasirox on central nervous symptoms and signs have been previously reported [30, 31]. Importantly, it is known that deferasirox can cross the blood-brain barrier, and therefore it has been reported as a potential treatment agent for neurological diseases [30]. In animals’ experiments with iron overload, low doses of deferasirox removed iron from certain brain regions related to dopamine metabolism [32] without side effects. In addition, in another study deferasirox reduced mortality in experimental animals with intracranial bleeding [33, 34]. In a study examining the effects of iron chelator on Alzheimer’s disease (AD), it was concluded that continuous administration of iron chelator could slow the clinical progression of dementia associated with AD [35]. Translational application of iron chelator in neurodegenerative diseases has also been conducted in PD animal models. It was confirmed that deferasirox reduced oxidative stress in the 6-OHDA-induced rat model of PD [27]. Collectively, deferasirox has been proved to be beneficial in alleviating diverse neurological disorders including AD, and PD. Our study provides novel insights into the mechanism through which deferasirox exerts neuroprotective effects, especially against oxidative stress in diverse neurological disorders.

We also elucidated the molecular mechanism by which deferasirox induces parkin expression. Mild endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by deferasirox treatment was responsible for the downstream parkin expression. Deferasirox treatment-induced mild ER stress was evidenced by increased phosphorylation of PERK, the ER stress marker, and ATF4 expression (Fig. 3 A, B). This mild stress-induced ATF4 activation seems necessary for parkin expression by deferasirox because siRNA knockdown of ATF4 abolished parkin induction by deferasirox. This involvement of ATF4 activation in parkin expression is consistent with the previously identified signaling pathways for parkin transcriptional activation by diaminodiphenyl sulfone [9]. It was shown that age-dependent decline of parkin downregulation and dopaminergic neuron loss can be reversed with the treatment of diaminodiphenyl sulfone [9]. In addition, diaminodiphenyl sulfone-induced parkin expression provided substantial dopaminergic neuroprotection and rescued motor behavioral deficits in a toxin-induced PD mouse model. Deferasirox increases parkin expression through mild ER stress and ATF4 activation in a similar manner to diaminodiphenyl sulfone. A similar mechanism between deferasirox and diaminodiphenyl sulfone suggests that deferasirox could have therapeutic value in preventing dopaminergic neuron loss during aging processes as well as in PD. For clinical application of deferasirox in these chronic situations, it would be important to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetic profile of deferasirox with long-term administration in preclinical PD animal models, given the previously reported nephrotoxicity with systemic deferasirox treatment [36].

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (2018R1D1A1B07046762), the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) and Korea Dementia Research Center (KDRC), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (HU22C0143000022).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., and Y.L.; methodology, S.H., J-Y.S., J.H.K. and H.K.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, S.H., J-Y.S., J.H.K.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H., J.H.K., and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.H., J.H.K., and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Sangwoo Ham and Ji Hun Kim these authors contributed equally to this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sangwoo Ham, Email: ham89p12@gmail.com.

Yunjong Lee, Email: ylee69@skku.edu.

References

- 1.Grayson M (2016) Parkinson’s disease. Nature 538:S1. 10.1038/538S1a [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lang AE, Lozano AM (1998) Parkinson’s disease. First of two parts. N Engl J Med 339:1044–1053. 10.1056/nejm199810083391506 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lang AE, Lozano AM (1998) Parkinson’s disease. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med 339:1130–1143. 10.1056/nejm199810153391607 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Dawson TM (2006) Parkin and defective ubiquitination in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl 209–213. 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_32 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Moore DJ (2006) Parkin: a multifaceted ubiquitin ligase. Biochem Soc Trans 34:749–753. 10.1042/bst0340749 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Chung KK, Thomas B, Li X, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Marsh L, Dawson VL, Dawson TM (2004) S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin’s protective function. Science 304:1328–1331. 10.1126/science.1093891 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ko HS, Lee Y, Shin JH, Karuppagounder SS, Gadad BS, Koleske AJ, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM (2010) Phosphorylation by the c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase inhibits parkin’s ubiquitination and protective function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:16691–16696. 10.1073/pnas.1006083107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Imam SZ, Zhou Q, Yamamoto A, Valente AJ, Ali SF, Bains M, Roberts JL, Kahle PJ, Clark RA, Li S (2011) Novel regulation of parkin function through c-Abl-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci 31:157–163. 10.1523/jneurosci.1833-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Lee YI, Kang H, Ha YW, Chang KY, Cho SC, Song SO, Kim H, Jo A, Khang R, Choi JY, Lee Y, Park SC, Shin JH (2016) Diaminodiphenyl sulfone-induced parkin ameliorates age-dependent dopaminergic neuronal loss. Neurobiol Aging 41:1–10. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Golbe LI, Di Iorio G, Sanges G, Lazzarini AM, La Sala S, Bonavita V, Duvoisin RC (1996) Clinical genetic analysis of Parkinson’s disease in the Contursi kindred. Ann Neurol 40:767–775. 10.1002/ana.410400513 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Venderova K, Park DS (2012) Programmed cell death in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2. 10.1101/cshperspect.a009365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lee Y, Karuppagounder SS, Shin JH, Lee YI, Ko HS, Swing D, Jiang H, Kang SU, Lee BD, Kang HC, Kim D, Tessarollo L, Dawson VL, Dawson TM (2013) Parthanatos mediates AIMP2-activated age-dependent dopaminergic neuronal loss. Nat Neurosci 16:1392–1400. 10.1038/nn.3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Stevens DA, Lee Y, Kang HC, Lee BD, Lee YI, Bower A, Jiang H, Kang SU, Andrabi SA, Dawson VL, Shin JH, Dawson TM (2015) Parkin loss leads to PARIS-dependent declines in mitochondrial mass and respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:11696–11701. 10.1073/pnas.1500624112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Pirooznia SK, Yuan C, Khan MR, Karuppagounder SS, Wang L, Xiong Y, Kang SU, Lee Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM (2020) PARIS induced defects in mitochondrial biogenesis drive dopamine neuron loss under conditions of parkin or PINK1 deficiency. Mol Neurodegener 15:17. 10.1186/s13024-020-00363-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Narendra D, Walker JE, Youle R (2012) Mitochondrial quality control mediated by PINK1 and parkin: links to parkinsonism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4. 10.1101/cshperspect.a011338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Winklhofer KF (2014) Parkin and mitochondrial quality control: toward assembling the puzzle. Trends Cell Biol 24:332–341. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bouman L, Schlierf A, Lutz AK, Shan J, Deinlein A, Kast J, Galehdar Z, Palmisano V, Patenge N, Berg D, Gasser T, Augustin R, Trümbach D, Irrcher I, Park DS, Wurst W, Kilberg MS, Tatzelt J, Winklhofer KF (2011) Parkin is transcriptionally regulated by ATF4: evidence for an interconnection between mitochondrial stress and ER stress. Cell Death Differ 18:769–782. 10.1038/cdd.2010.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Ham S, Lee YI, Jo M, Kim H, Kang H, Jo A, Lee GH, Mo YJ, Park SC, Lee YS, Shin JH, Lee Y (2017) Hydrocortisone-induced parkin prevents dopaminergic cell death via CREB pathway in Parkinson’s disease model. Sci Rep 7:525. 10.1038/s41598-017-00614-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ward RJ, Zucca FA, Duyn JH, Crichton RR, Zecca L (2014) The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol 13:1045–1060. 10.1016/s1474-4422(14)70117-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mezzaroba L, Alfieri DF, Colado Simão AN, Vissoci Reiche EM (2019) The role of zinc, copper, manganese and iron in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotoxicology 74:230–241. 10.1016/j.neuro.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Smith MA, Harris PL, Sayre LM, Perry G (1997) Iron accumulation in Alzheimer disease is a source of redox-generated free radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:9866–9868. 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Deas E, Cremades N, Angelova PR, Ludtmann MH, Yao Z, Chen S, Horrocks MH, Banushi B, Little D, Devine MJ, Gissen P, Klenerman D, Dobson CM, Wood NW, Gandhi S, Abramov AY (2016) Alpha-synuclein oligomers interact with metal ions to induce oxidative stress and neuronal death in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 24:376–391. 10.1089/ars.2015.6343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yarjanli Z, Ghaedi K, Esmaeili A, Rahgozar S, Zarrabi A (2017) Iron oxide nanoparticles may damage to the neural tissue through iron accumulation, oxidative stress, and protein aggregation. BMC Neurosci 18:51. 10.1186/s12868-017-0369-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sakamoto K, Suzuki T, Takahashi K, Koguchi T, Hirayama T, Mori A, Nakahara T, Nagasawa H, Ishii K (2018) Iron-chelating agents attenuate NMDA-Induced neuronal injury via reduction of oxidative stress in the rat retina. Exp Eye Res 171:30–36. 10.1016/j.exer.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Jiménez-Solas T, López-Cadenas F, Aires-Mejía I, Caballero-Berrocal JC, Ortega R, Redondo AM, Sánchez-Guijo F, Muntión S, García-Martín L, Albarrán B, Alonso JM, Del Cañizo C, Hernández-Hernández Á, Díez-Campelo M (2019) Deferasirox reduces oxidative DNA damage in bone marrow cells from myelodysplastic patients and improves their differentiation capacity. Br J Haematol 187:93–104. 10.1111/bjh.16013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Miao J, Xu M, Kuang Y, Pan S, Hou J, Cao P, Duan X, Chang Y, Hasem H, Zhou N, Tan K, Fan Y (2020) Deferasirox protects against hydrogen peroxide-induced cell apoptosis by inhibiting ubiquitination and degradation of p21(WAF1/CIP1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 524:736–743. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.01.155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Dexter DT, Statton SA, Whitmore C, Freinbichler W, Weinberger P, Tipton KF, Della Corte L, Ward RJ, Crichton RR (2011) Clinically available iron chelators induce neuroprotection in the 6-OHDA model of Parkinson’s disease after peripheral administration. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 118:223–231. 10.1007/s00702-010-0531-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Kim H, Shin JY, Jo A, Kim JH, Park S, Choi JY, Kang HC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Shin JH, Lee Y (2021) Parkin interacting substrate phosphorylation by c-Abl drives dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Brain 144:3674–3691. 10.1093/brain/awab356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Cappellini MD (2007) Exjade(R) (deferasirox, ICL670) in the treatment of chronic iron overload associated with blood transfusion. Ther Clin Risk Manag 3:291–299. 10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.2.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Loréal O, Turlin B, Pigeon C, Moisan A, Ropert M, Morice P, Gandon Y, Jouanolle AM, Vérin M, Hider RC, Yoshida K, Brissot P (2002) Aceruloplasminemia: new clinical, pathophysiological and therapeutic insights. J Hepatol 36:851–856. 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00042-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Mariani R, Arosio C, Pelucchi S, Grisoli M, Piga A, Trombini P, Piperno A (2004) Iron chelation therapy in aceruloplasminaemia: study of a patient with a novel missense mutation. Gut 53:756–758. 10.1136/gut.2003.030429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Ward RJ, Dexter D, Florence A, Aouad F, Hider R, Jenner P, Crichton RR (1995) Brain iron in the ferrocene-loaded rat: its chelation and influence on dopamine metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol 49:1821–1826. 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00521-m [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Hua Y, Keep RF, Hoff JT, Xi G (2008) Deferoxamine therapy for intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl 105:3–6. 10.1007/978-3-211-09469-3_1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Selim M (2009) Deferoxamine mesylate: a new hope for intracerebral hemorrhage: from bench to clinical trials. Stroke 40:S90–91. 10.1161/strokeaha.108.533125 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Crapper McLachlan DR, Dalton AJ, Kruck TP, Bell MY, Smith WL, Kalow W, Andrews DF (1991) Intramuscular desferrioxamine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 337:1304–1308. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92978-b [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Martin-Sanchez D, Gallegos-Villalobos A, Fontecha-Barriuso M, Carrasco S, Sanchez-Niño MD, Lopez-Hernandez FJ, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J, Ortiz A, Sanz AB (2017) Deferasirox-induced iron depletion promotes BclxL downregulation and death of proximal tubular cells. Sci Rep 7:41510. 10.1038/srep41510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]