Abstract

Oxidative stress including decreased antioxidant enzyme activities, elevated lipid peroxidation, and accumulation of advanced glycation end products in the blood from children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) has been reported. The mechanisms affecting the development of ASD remain unclear; however, toxic environmental exposures leading to oxidative stress have been proposed to play a significant role. The BTBRT+Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) strain provides a model to investigate the markers of oxidation in a mouse strain exhibiting ASD-like behavioral phenotypes. In the present study, we investigated the level of oxidative stress and its effects on immune cell populations, specifically oxidative stress affecting surface thiols (R-SH), intracellular glutathione (iGSH), and expression of brain biomarkers that may contribute to the development of the ASD-like phenotypes that have been observed and reported in BTBR mice. Lower levels of cell surface R-SH were detected on multiple immune cell subpopulations from blood, spleens, and lymph nodes and for sera R-SH levels of BTBR mice compared to C57BL/6 J (B6) mice. The iGSH levels of immune cell populations were also lower in the BTBR mice. Elevated protein expression of GATA3, TGM2, AhR, EPHX2, TSLP, PTEN, IRE1α, GDF15, and metallothionein in BTBR mice is supportive of an increased level of oxidative stress in BTBR mice and may underpin the pro-inflammatory immune state that has been reported in the BTBR strain. Results of a decreased antioxidant system suggest an important oxidative stress role in the development of the BTBR ASD-like phenotype.

Keywords: Autism, BTBR, Oxidative stress, Surface thiols, Glutathione, Antioxidant

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in humans is characterized by the existence of numerous indicators such as verbal impairment, deficiency in social interaction, and stereotypical patterns of behavioral phenotypes. ASD prevalence in the USA was reported to be 1 in 44 children aged 8 years in 2018 (Maenner et al. 2021). ASD involves a dysfunctional immune system including activation of both innate and adaptive immune cells; dysregulated T cell subsets such as Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg have been associated with ASD (Ahmad et al. 2017; Nadeem et al. 2020). Oxidative stress and damage occur when antioxidant defense systems fail to protect against reactive oxygen species (Birben et al. 2012). Glutathione (GSH) is the primary antioxidant accountable for maintaining the reducing intracellular and extracellular microenvironment that is crucial for normal cellular function and viability (Lushchak 2012; Deponte 2017; Iskusnykh et al. 2022). Recently, an increase in oxidant-modified protein and DNA damage has been reported in relation to the decrease in intracellular and plasma GSH in children with ASD (Liu et al. 2022). Lower levels of GSH, higher levels of glutathione disulfide (GSSG), and reduced GSH/GSSG redox ratio have been reported in ASD individuals (Bjørklund et al. 2020). ASD severity also has been correlated with lower GSH levels and increased oxidative stress (Chen et al. 2021). Moreover, the dysregulated pattern of metallothionein (MT), a major non-enzymatic antioxidant, also has been observed within the ASD population (Meguid et al. 2019). By affecting the availability of free zinc (Zn2+), MT like Zn2+ can have anti- and pro-inflammatory influences (Haase and Rink 2007; Maares and Haase 2016). MT may also affect immunity due to its chemotactic activity (Yin et al. 2005). Oxidant-antioxidant imbalance and inflammatory cytokines in individuals diagnosed with ASD play a prominent role in the development and severity of neurobehavioral dysregulation (Pangrazzi et al. 2020). Elevated levels of protein and lipid peroxidation products such as nitrotyrosine and TBARS have been reported both in the periphery and central nervous system (CNS) of autistic individuals (Ei-Ansary and Al-Ayadhi 2012; Frye and James 2014). Dysregulated enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants in the brain and blood of individuals with ASD have also been reported. Importantly, GSH level has been shown to be steadily diminished in autistic children both in the blood and CNS (Chauhan et al. 2012; Gu et al. 2013). Oxidative stress indicators, e.g., reactive oxygen derivatives, were found in children with ASD, which can cause DNA damage leading to changes in DNA function and regulation of gene expression. Additionally, higher toxic oxygen derivatives can damage the neuro-messenger serotonin in the brain (Ramaekers et al. 2020). Compared to controls, the ASD cohort showed a significant increase in oxidative DNA damage in lymphocytes (Ramaekers et al. 2020). Elevated levels of oxidative stress in the brain and peripheral immune cells (Nadeem et al. 2019) as well as additional biomarkers, which may contribute to the ASD-like behavioral phenotype of BTBR mice, need to be investigated.

Irregular eating behaviors in children with ASD may play a key role in worsening ASD symptoms (Peretti et al. 2019). The use of antioxidant nutritional supplements has shown potential therapeutic value for ASD treatment. Reduced blood levels of vitamin D have been reported for ASD individuals (Wang et al. 2016), and a 3-month treatment with Vitamin D3 improved measures of behavioral abnormality in younger children advancing this therapeutic potential for the treatment of ASD (Jia et al. 2015; Feng et al. 2017; Saad et al. 2016). Vitamin D has a homeostatic influence on innate and adaptive immune cells to help control autoimmune responses (Szodoray et al. 2008; Baeke et al. 2010; Dupuis et al. 2021), including neurological diseases (Plantone et al. 2022; Lee et al. 2020). Vitamin D and folic acid have been recommended for fetal brain development (Tan et al. 2020; Freedman et al. 2022). Irregular metabolism of folic acid is linked to ASD, and its shortage in the brains has been reported for individuals with ASD (Karin et al. 2017).

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) contributes to brain development, and altered PTEN gene expression has been linked to the behaviors of ASD (Ledderose et al. 2022). Various stress and apoptosis-related molecules such as transglutaminase 2 (TGM2), inositol-requiring enzyme 1alpha (IRE1α), and growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) have been involved in various neurodegenerative conditions including multiple sclerosis, inflammation, brain injury, and behavioral changes (Crider et al. 2018; Dong et al. 2018; Adela and Banerjee 2015); these biomarkers are evaluated herein. Increased brain expression of GATA-3 may also contribute to the development of ASD (Rout and Clausen 2009). Higher levels of epoxide hydrolases (EPHX2), which hydrolyze anti-inflammatory epoxy lipids have been reported in neuroinflammation and leading to neuropathology (Ghosh et al. 2020). Excessive expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) also plays an important function in developmental brain toxicity (Akahoshi et al. 2006). Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is an epithelial cytokine expressed at barrier surfaces of the skin, gut, nose, and lung, including the central nervous system, and in the brain, it is upregulated in myelin-degenerative brain disease (Kitic et al. 2014).

The BTBRT+Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mouse strain has been increasingly used to study the underlying mechanisms for the development of ASD, due to the ASD-like behavioral traits it exhibits, such as the following: decreased social interaction, increased levels of stereotypies such as self-grooming and decreased vocalizations during social interactions (McFarlane et al. 2008). BTBR mice have an altered immune system with higher production of proinflammatory cytokines, autoantibodies (autoAbs), and activation of numerous immune populations, which are similar in nature to an autistic individual (Bjorklund et al. 2016; Careaga et al. 2015). As in many families with an ASD person, the BTBR mice have autoAbs to brain antigens and poor immunity to microbes (Heo et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2013; Uddin et al. 2020a, b).

In our previous studies, we reported higher levels of serum IgG, IgG anti-brain antibodies (Abs), and higher expression of some cytokines in the periphery and brain of BTBR mice (Heo et al. 2011). The maternal environment importantly maternal anti-brain autoAbs was shown to influence the development of ASD-like behaviors in offspring (Zhang et al. 2013). An increase of Tfh cells and Ab-producing plasma cells in BTBR mice was also reported (Uddin et al. 2020a, b).

Herein, we measure the oxidative stress biomarkers in the BTBR mouse model of ASD and investigated expression levels of specific proteins suggested to be associated with brain functions, oxidative stress, and/or contribute to or be bystander biomarkers of the ASD-like behavior.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult C57BL/6 J (B6) and BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J (BTBR) mice were initially purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and then bred to maintain a colony at our facility. Male and female mice (8–12 weeks of age) were used for all procedures. Female and male BTBR mice have been reported to have equivalent ASD-like behavior (Zhang et al. 2013). No differences were observed between males and females for all our measures; thus, all findings were collapsed across gender within each strain for data presentation. Mouse colonies were maintained on a 12:12 h light–dark cycle (lights on 7 AM) in our AAALAC-approved Animal Facility. All experimental procedures were approved by the Wadsworth Center’s IACUC.

Cell and serum preparation

Spleens and lymph nodes were harvested and collected into cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Single-cell suspensions were prepared by pressing through a cell strainer (Fisherband, Sterile Cell strainer, 100 µM Cat No: 22363549, Fisher Scientific). Red blood cells (RBC) from spleens were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (Cat; 00–4333-57, eBioscience/Invitrogen) before staining. Cells were enumerated with an automated cell counter (Countess II FL, Invitrogen) after staining with Live/dead dyes Acridine Orange (Cat #A3568, Invitrogen) and ethidium homodimer (Cat# E1169, Invitrogen) used at 1:100 and 1:200 dilution in PBS, respectively; viable cells (1 × 106) were used for flow cytometry. For surface R-SH and immunophenotyping, blood samples were stained as described later followed by RBC lysis with BD FACS lysing solution (BD Biosciences, Ref 349,202) or BD Pharm lyse (BD Biosciences, Cat: 555,899).

For collecting serum, blood samples were obtained by trans-cardiac bleeds and aliquoted into centrifuge tubes (2 mL Axygen microtubes, Cat# MCT-200-C, ThermoFisher) and kept at room temperature for 30–60 min and separated by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min. Serum samples were aliquoted and preserved at − 80 °C until use.

Measurement of serum R-SH

Serum R-SH was quantified using Measure-iT™ Thiol Assay Kit (M30550) (Molecular probe) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 100 µL of the Measure-iT™ thiol quantitation reagent working solution was loaded into each microplate well. The Measure-iT™ thiol quantitation standards (10 µL) were added into wells for standard and mixed well. Test sera (10 µL) were added into sample wells and mixed well. Duplicate wells were used for standard and test samples. Finally, after 5-min incubation, fluorescence/well was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek EL808) at excitation/ emission maxima of 494/517 nm.

Quantification of the GSH/GSSG ratio

GSH/GSSG Ratio Assay (referred to as Fluorometric – Green ab138881 kit, Abcam) was performed to detect oxidative stress effects on serum. Enzymes were removed from the diluted serum (1/10) by using the deproteinizing chemical trichloroacetic acid (TCA), neutralized to pH 5 using NaHCO3, and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C with the supernatants collected as test samples. For GSH detection, GSH Assay Mixture (GAM; 50 µL) was added into each GSH standard and test well to make the total assay volume 100 µL/well of a 96-well Costar plate (Cat #3369, Corning). For total GSH + GSSG (reduced and oxidized), 50 µL of total Glutathione Assay Mixture (TGAM) was added into each GSSG standard and test well to make the total assay volume 100 µL/well. The assay plates were incubated at room temperature for 40 min in the dark. Fluorescence at Ex/Em = 490/520 nm was recorded. GSH/GSSG Ratio = [GSH]/[GSSG] = [GSH]/[(Total Glutathione – GSH)/2].

Surface and intracellular staining

Cells from the spleens and lymph nodes were transferred into a FACS tube (100 µl, 1 × 106 cell), blocked with mouse Fc Block™ (cat #553,142, BD Pharmingen), and stained with surface antibodies. Cells were then washed and resuspended with BD FACS buffer, and data were analyzed by flow cytometry. For intracellular staining, cells were first stained for surface markers. After washing, cells were fixed and permeabilized with fixation/permeabilization buffer (Fixation/Permeabilization buffer set, Cat: 00–5123-43, eBioscience). Intracellular staining and washing were performed in the presence of a permeabilization buffer (Permeabilization buffer, Cat:00–8333-56, eBioscience). After final washing, cells were resuspended in FACS buffer, and data were collected by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

The cells were stained for surface and/or intracellular molecules and analyzed by FACS Canto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The following fluorochrome-conjugated Abs: PerCP Cy5.5-CD45, APC Cy7-CD45, PerCP Cy5.5-CD4, PE-CD4, FITC-CD4, FITC-CD3, APC-CD3e, PerCP-CD3e, APC Cy7-CD3, PE-CD11b, PE Cy7-CD11b, FITC-MHC-II, PerCP Cy5.5-MHCII, PE-CD19, FITC-CD19, PE Cy7-CD19, PE Cy7-NK1.1, PE-IL-4R, PE-IL-12Rβ1, and Fc Block™ (anti-CD16/32) were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), Biolegend (San Diego, CA), or eBiosciences (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). All flow cytometry data was acquired with a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Frequencies and numbers of populations in the spleens and lymph nodes of B6 and BTBR mice were gated based on FSC-A and SSC-A, followed by gating on single cells and finally gated on CD45+ cells before subpopulation analyses as described. Acquired FCS files were analyzed by Flow Jo-V10. Granulocytes (SSC-Ahi/CD45low), monocytes (SSC-Amed/CD45med), and lymphocytes (SSC-Alow/CD45hi) are gated based on the SSC-A and CD45 expression. The immune subpopulations such as B cell (CD19+CD3−), T cell (CD3+ CD19−), CD4+T cell (CD3+ CD4+ CD19−), CD8+T cell (CD3+ CD8+ CD19−), NK cell (CD3−CD19−NK1.1+), NKT cell (CD3+CD19−NK1.1+), and CD11b+ myeloid cells (CD3−CD19−NK1.1−CD11b+) were identified based on the surface expression of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, NK1.1, and CD11b on CD45+ population.

Detection of cell surface-free thiols (R-SH)

The impermeant thiol-specific probe Alexa Fluor™ 488 C5 Maleimide (AFM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Catalog number: A10254) was dissolved in DMSO to make a 2.5 mM stock. To assess cell surface-free R-SH, blood cells were washed with ice-cold HBSS, incubated in 5 μM AFM for 15 min on ice, and then washed and surface stained for cell surface markers. After incubation, RBC were lysed, and cells were fixed. Cells were then washed and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Measurement of intracellular glutathione

Spleen and lymph node cells were washed and resuspended in PBS at 107 cells/ml. A cell suspension (1 × 106 cells/100 µl) was stained with the appropriate surface antibody mixture and incubated for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Cells were then washed and resuspended with 5 mM N-methyl maleimide (NEM) (Sigma Cat 12,828–7) in cytofix/cytoperm solution (BD biosciences, Cat: 554,722) for overnight at 4 °C. After 2 × washing with Perm/wash solution (BD biosciences, Cat: 554,723) cells were resuspended in 100 µl Perm/Wash solution containing 2 µg AlexaFluor 488-conjugated 8.1-GSH mAb (anti-GS-NEM, MilliporeSigma MAB3194). Cells were then incubated for 30 min, washed 2 × with Perm/Wash solution, and analyzed with a flow cytometer.

Western blot analysis

Total protein concentration was detected by BCA assay using bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) for the standard curve. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by 10–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% v/v fish gelatin (Cat#G7665, MilliporeSigma) and made up in TBST (20 mM Tris base, pH 7.6, 140 mM NaCl, 0.05% v/v Tween-20) and membranes were incubated on a rocker for 2 h at room temperature. After blocking the membranes incubated with primary antibodies: anti-GATA3 (1:100;HG3-31; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz), rat anti-TSLP (1: 250;151,805 (Bio Legend), rabbit anti-AhR (1: 2000; 5A-210, Biomol), rabbit anti-PTEN (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000; 9559; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-IRE1α (1: 1000; 3294; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-GDF15 (1:100; A0185; Abclonal), rabbit anti-EPHX2 from Abclonal (1:1000; A1855), anti-MT monoclonal antibody (UC1MT) was gifted from Dr. Michael A Lynes (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT) and was used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Primary antibodies were followed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti rat, rabbit anti-mouse, or goat anti-rabbit antibody. Anti-β-actin primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used for loading control. The blots were developed by incubation with Super Signal/chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) for 5 min and were assayed with a LAS-3000plus imager (Fuji). The results are reported as “normalized fold expression,” which was calculated as the chemiluminescence value of the indicated analyte divided by that of the loading control.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by MS Excel and are presented as mean ± SEM, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to determine p values, and p < 0.05 was measured as a statistically significant difference.

Results

Surface thiols (R-SH) on Immune cells

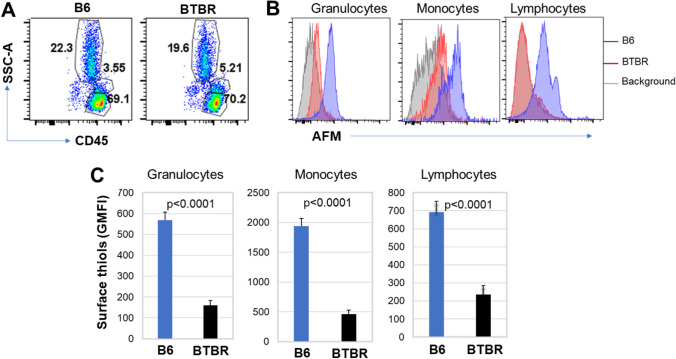

Organ and tissue damage occurs due to excessive oxidative stress. R-SH is one of the key protective means to mitigate oxidative stress, and changes in the status of R-SH affect various diseases and is very significant in the pathogenesis of oxidative stress–mediated diseases. Therefore, levels of R-SH in and on the surface of immune cells (granulocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes) from BTBR and B6 mice were investigated. The blood leukocyte populations were identified by their CD45 expression and position in SSC-A vs FSC-A plots. The frequency of CD45+ granulocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes in B6 and BTBR mice are shown (Fig. 1A); based on the level of AFM, the expression of surface R-SH was reduced on granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes from BTBR mice (Fig. 1B). The geometric mean fluorescent intensity (GMFI) of AFM, which indicates available R-SH able to be alkylated by AFM, was significantly reduced on cells of BTBR mice compared to B6 mice (Fig. 1C and Table 1) suggesting a greater level of oxidative stress.

Fig. 1.

Surface thiols (R-SH) on granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes of BTBR B6 mice. Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD45+ cells (A) from B6 and BTBR blood sample. Granulocytes (SSC-Ahi/CD45low), monocytes (SSC-Amed/CD45med) and lymphocytes (SSC-Alow/CD45hi) are shown. The overlay histograms (B) show the expression of surface R-SH on granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes population; the background histogram is shown for the absence of AFM to label surface thiols. The geometric mean fluorescent intensity (GMFI) of R-SH on granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes in the blood of B6 and BTBR mice is shown (C). Data are representative of three or four independent experiments with 4–6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

Table 1.

Surface R-SH levels of blood cells (GMFI)

| Cell type | B6 (n = 6) | BTBR (n = 6) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granulocyte | 568 ± 38 | 159 ± 22 | p < 0.0001 |

| Monocytes | 1936 ± 132 | 462 ± 69 | p < 0.0001 |

| Lymphocytes | 693 ± 60 | 236 ± 48 | p = 0.001 |

| CD19+ B cells | 574 ± 36 | 168 ± 49 | p = 0.001 |

| CD4+ T cells | 351 ± 32 | 145 ± 10 | p = 0.001 |

| CD8+ T cells | 1492 ± 193 | 492 ± 80 | p = 0.01 |

| NK cells | 189 ± 19 | 61.3 ± 6 | p = 0.001 |

| NKT cells | 220 ± 21 | 73 ± 9 | p = 0.001 |

| CD4+IL-4R+ T cells | 1015 ± 111 | 718 ± 25 | p = 0.07 |

| CD4+ IL-12Rβ1+ T cells | 1386 ± 124 | 1074 ± 62 | p = 0.04 |

Surface R-SH of T and B cells

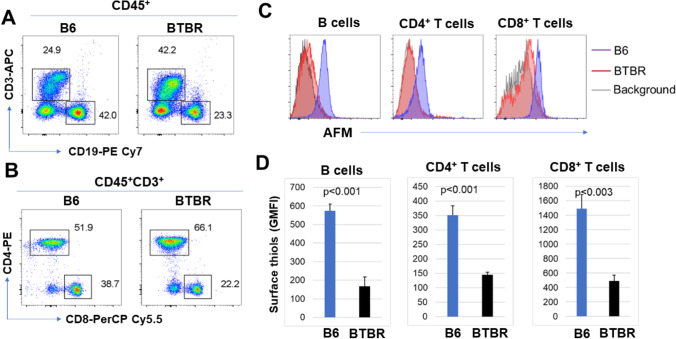

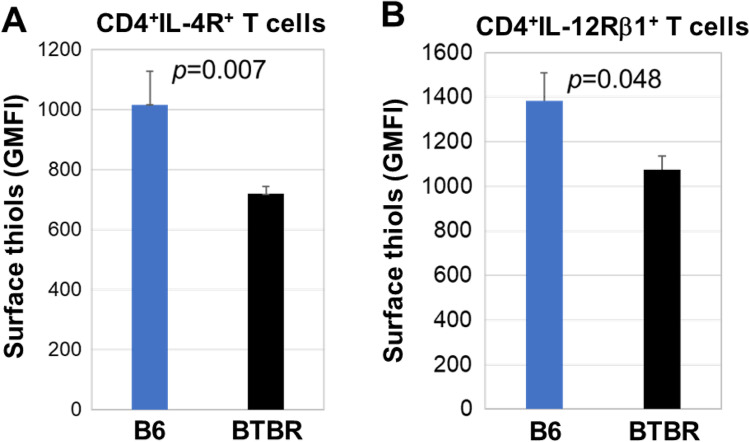

To assess the abundance of surface R-SH in T cell and B cell populations, we labeled the AFM-treated cells with antibodies to CD19, CD3, CD4, and CD8 and evaluated their R-SH levels. The representative gating strategies are shown (Fig. 2A). The R-SH levels of B and T cells were reduced in BTBR mice compared to B6 mice (Fig. 2B). Statistical analysis reveals that the GMFI of AFM on B cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells were significantly reduced for BTBR mice (Fig. 2C and Table 1) compared with B6 mice. The CD4+ T cells were further differentiated for surface R-SH based on their expression of IL-4R or IL-12Rβ1. Both IL-4R+ and IL-12Rβ1+ CD4+ T cells had a significantly lower number of R-SH on BTBR cells than B6 cells (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

Fig. 2.

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells from BTBR mice show decreased surface R-SH levels. Representative flow cytometric analysis (A, B) of CD3+, CD19+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells (A, B) from B6 and BTBR blood samples are shown. Overlay histograms (C) show the expression of surface R-SH on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells. The GMFI of surface R-SH is shown (D). Data are representative of three or four independent experiments with 4–6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

Fig. 3.

The surface R-SH level (GMFI) on CD4+IL-4R+ cells (A) and CD4+IL-12Rβ1+ (B) cells are lower in BTBR mice compared to B6 mice. Data are representative of three or four independent experiments with 4–6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

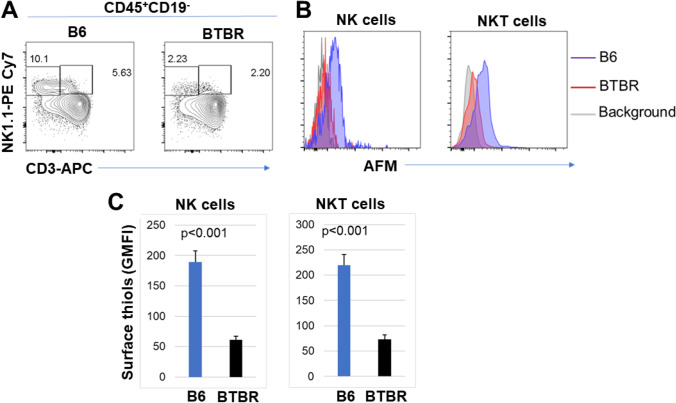

Surface R-SH on innate cells

To investigate the surface levels of R-SH on the innate immune cell population, NK and NKT cells in blood from B6 and BTBR mice were assayed with antibodies to CD3 and NK1.1. The gating for the NK and NKT cells is shown (Fig. 4A). The abundance of surface R-SH was reduced on both NK cells and NKT cells (Fig. 4B) from BTBR mice compared to B6 mice. The GMFI analysis indicated a significant reduction for the BTBR mice (Fig. 4C and Table 1).

Fig. 4.

BTBR mice have significantly lower surface R-SH on NK and NKT cells than B6 mice. Representative flow cytometric analysis (A) of NK and NKT cells from B6 and BTBR blood samples. The overlay histograms (B) shows the expression levels on NK and NKT cell populations. The GMFI of surface R-SH on NK and NKT cells in the blood of B6 and BTBR mice is shown (C). Data are representative of three or four independent experiments with 4–6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

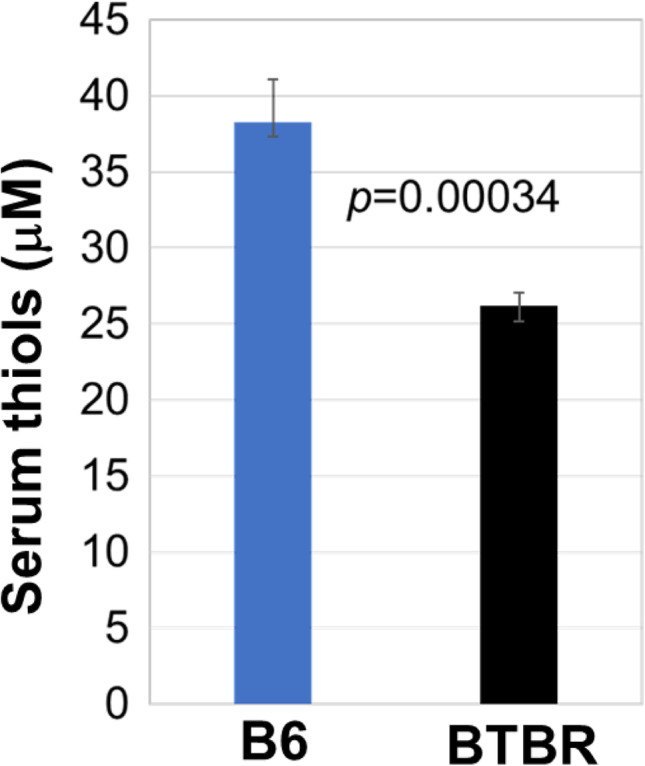

Serum R-SH level

Since surface levels of R-SH were lower on all assayed leukocyte populations and the extracellular GSH is known to support cellular R-SH levels and GSH is the major serum R-SH, serum R-SH levels were measured. BTBR mice had significantly lower serum levels of R-SH (Fig. 5) than B6 mice. The lower levels of R-SH in BTBR sera further indicate the reduced antioxidant capacity of BTBR mice compared to B6 mice.

Fig. 5.

Lower levels of serum thiols in BTBR mice have a lower level of serum thiols than B6 mice. ELISA of BTBR and B6 serum thiols. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with 6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

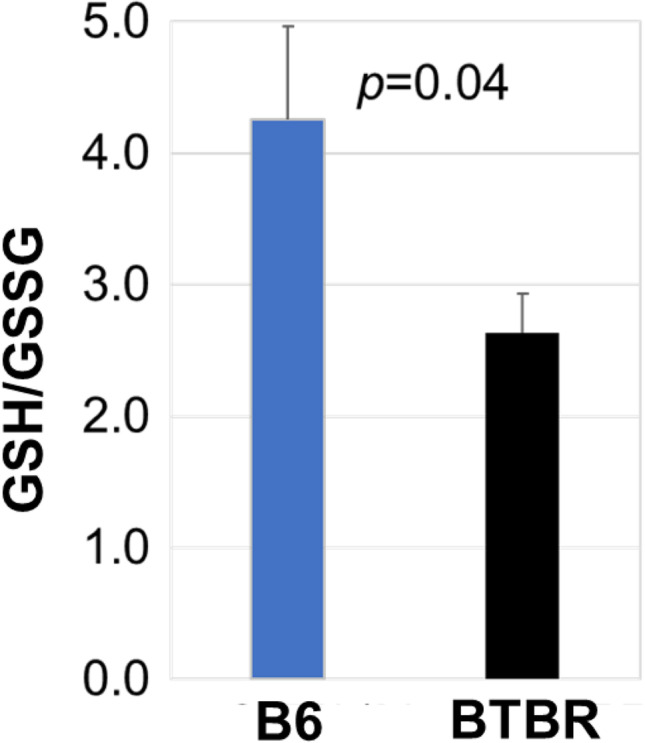

GSH/GSSG ratio of sera

Since GSH is a very important scavenger of reactive oxygen species (ROS) its concentration with the oxidized form of glutathione (GSSG) in serum, the GSH/GSSG ratio can be used as a marker of the oxidative stress condition and as an indirect analysis of GSH synthesis. The GSH/GSSG ratio was significantly lower for BTBR sera compared to sera from B6 mice (Fig. 6). The low GSH/GSSG ratio of BTBR mice further indicates the oxidative stress state in BTBR mice, which might contribute to both the altered behavior and immunity of BTBR mice.

Fig. 6.

BTBR mice have a lower serum GSH/GSSG ratio than B6 mice. Data are representative of three independent experiments with 6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

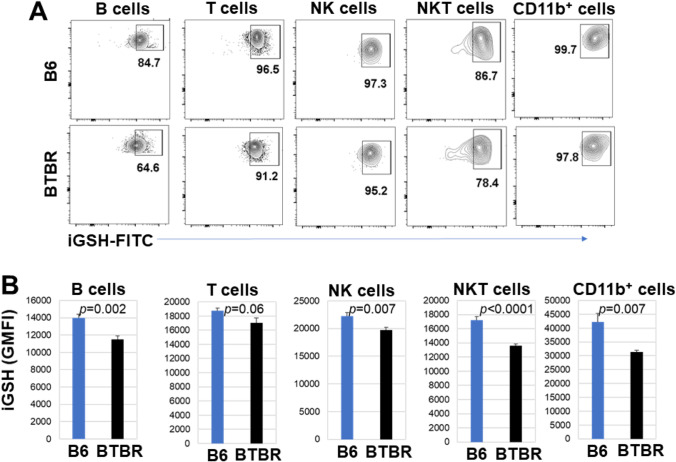

Level of intracellular glutathione (iGSH)

Since the R-SH of sera and the surface R-SH of blood leukocytes were lower for BTBR than B6 mice, iGSH levels were evaluated. The iGSH level is essential for controlling cellular redox and detoxification status of cells and tissues against oxidative stress and free radicals. The iGSH levels of B, T, NK, NKT, and CD11b+ cells were evaluated by flow cytometry. For splenic B, T, NK, NKT, and CD11b+ cells, there was a lower percentage of IGSH+ cells from BTBR mice than B6 mice (Fig. 7A and Table 2), and the GMFIs of iGSH of B, T, and NKT cells were reduced in BTBR mice compared to B6 mice. However, the NK and CD11b+ cellular levels of iGSH were not significantly different for BTBR and B6 samples (Fig. 7B and Table 2). Interestingly, for cells isolated from the lymph nodes, there were similar iGSH results as spleen for B and NKT cells; however, the T cells were not significantly different and the NK and CD11b+ cells were significantly different between BTBR and B6 mice (Fig. 8A and Table 2).

Fig. 7.

BTBR splenic cells have lower intracellular glutathione (iGSH) levels than those of B6 mice. Representative flow cytometric analysis of the iGSH expression (A) for pre-gated lymphocytes (SSC-Alow/CD45hi) or myeloid cells (SSC-Amed−hi/CD45low−med) and assayed for subpopulations of B (CD19+CD3−), T (CD3+), NK (CD3−CD19− NK1.1+CD11b+/−), NKT (CD3+CD19−NK1.1+ CD11b+/−) lymphoid, and CD11b+ myeloid cells from B6 and BTBR mice. GMFI of intracellular glutathione expressions of subpopulations from B6 and BTBR mice are compared (B). Data are representative of three or four independent experiments with 4–6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

Table 2.

The iGSH level of splenic and cervical lymph node cells (GMFI)

| Cell type | B6 (n = 6) | BTBR (n = 6) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical lymph node cells | |||

| CD19+ B cells | 13,963 ± 448 | 11,492 ± 413 | p = 0.01 |

| CD3+ T cells | 18,749 ± 393 | 17,015 ± 734 | p = 0.063 |

| NK cells | 22,261 ± 585 | 19,740 ± 490 | p = 0.01 |

| NKT cells | 17,228 ± 465 | 13,587 ± 259 | p < 0.0001 |

| CD11b+ cells | 42,142 ± 3169 | 31,332 ± 634 | p = 0.01 |

| Spleen cells | |||

| CD19+ B cells | 7307 ± 237 | 6050 ± 207 | p = 0.01 |

| CD3+ T cells | 11,302 ± 324 | 9988 ± 364 | p = 0.02 |

| NK cells | 10,111 ± 295 | 9533 ± 560 | p = 0.38 |

| NKT cells | 9488 ± 275 | 7085 ± 356 | p = 0.001 |

| CD11b+ cells | 18,898 ± 881 | 20,202 ± 673 | p = 0.24 |

Fig. 8.

BTBR lymph node cells have less iGSH than those of B6 mice. Representative flow cytometric analysis of the iGSH expression (A) in B, T, NK, NKT, and CD11b+ cells from B6 and BTBR lymph nodes; gated and analyzed as described in Fig. 7 (B). Data are representative of three or four independent experiments with 4–6 pairs of mice in each experiment. The bars show means ± SEM and p values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for B6 and BTBR differences

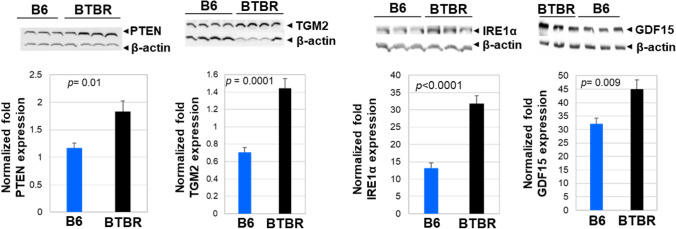

Oxidative stress marker in the brain of BTBR and B6 mice

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and its signal cascades regulate brain development during multiple stages. PTEN is an interesting target to study ASD etiology because of its regulation of many proteins involved in disease development. We measured the level of PTEN in the brain tissue of B6 and BTBR mice by western blot. Our results indicate a significantly higher PTEN protein level in the brain of BTBR mice compared to B6 mice (Fig. 9). Higher levels of PTEN in BTBR mice might account for the abnormal mitochondrial functions and energy production seen in this mouse strain (Yao et al 2022).

Fig. 9.

Western blot analysis of multi-functional phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN, a molecular marker of proinflamatory cytokines), transcription factor transglutaminase II (TGM2, an endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein sensor0, and IRE1 alpha and growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) in the brains of B6 and BTBR mice. The protein expression of PTEN, TGM2, IRE1α, and GDF15 in the brains of B6 (n = 3–4) and BTBR (n = 3–4) mice were assayed. β-actin was used as a loading control. The data is presented as mean ± SEM; p values by Student’s t test are shown for B6 and BTBR comparisons

Since TGM2 is involved in various disorders including neurodegeneration, multiple sclerosis, and brain injury, and is a stress-induced gene, we investigated brain expression of this protein. Western blot analysis showed significantly higher protein levels of TGM2 in BTBR brains compared to B6 brains (Fig. 9).

IRE1α protein is a single-pass, type 1 membrane protein within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that functions as a sensor of unfolded ER proteins. IRE1α autophosphorylates under ER stress conditions. Western blot analysis indicated that BTBR brains have more IRE1 alpha than B6 brains (Fig. 9).

GDF15 is a stress-responsive cytokine and is a biomarker of oxidative stress, inflammation, and hormonal changes. GDF15 levels are also affected by environmental factors independently of genetic background. BTBR brains had a significantly higher amount of GDF15 protein level than B6 brains (Fig. 9).

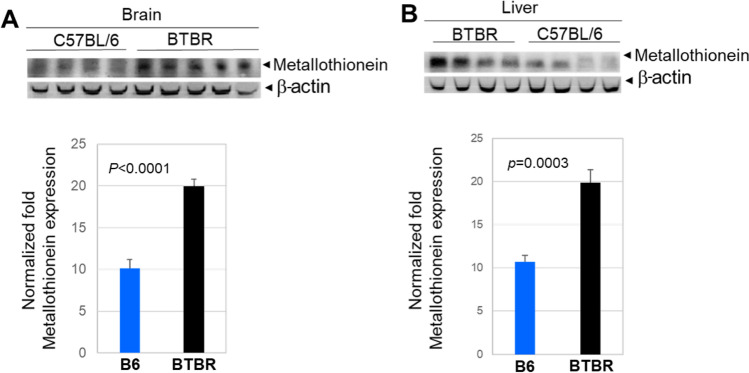

Metallothionein (MT) expression in the brain and liver

Metallothioneins (MT) are low molecular weight cysteine-rich vital proteins for the cellular defense antioxidant system and detoxification. The protective role of MT against ROS damage in biological systems has been widely reported. Different studies have shown that the thiolate ligands in cysteine residues confer the redox activity of MT. These residues can be oxidized by cellular oxidants during this process. Western blot analysis indicated upregulation of MT protein levels in the brains (Fig. 10A) and livers (Fig. 10B) of BTBR mice compared to B6 mice.

Fig. 10.

Metallothionein (MT) protein expression in the brains (A) and livers (B) of B6 (n = 4) and BTBR (n = 4–5) mice. β-actin was used as a loading control. The data is presented as mean ± SEM; p values by Student’s t test are shown for B6 and BTBR comparisons

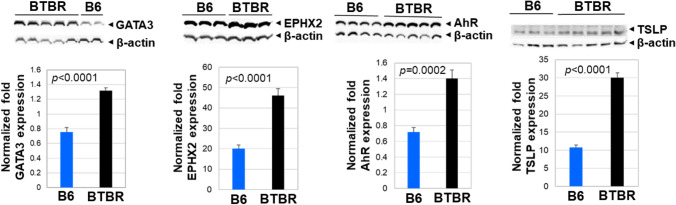

Inflammatory and toxic molecule in the brain of BTBR and B6 mice

Expression of the transcription factor GATA-3 controls a wide range of biologically and clinically important genes. The GATA-3 transcription factor is critical for the embryonic development of various tissues as well as for inflammatory and humoral immune responses. Additionally, GATA-3 is involved in the development of the brain. Western blot analysis indicated GATA-3 protein levels were significantly increased in BTBR brains compared to B6 brains (Fig. 11A).

Fig. 11.

Western blot analysis of GATA3, EPHX2, AhR, and TSLP of protein expression in the brains from B6 (n = 2–4) and BTBR (n = 4–6) mice. β-actin was used as a loading control. The data is presented as mean ± SEM; p values by Student’s t test are shown for B6 and BTBR comparisons

Epoxy fatty acids have anti-inflammatory functions, but their activities are obstructed by rapid hydrolysis due to epoxide hydrolase activity. Increased levels of EPHX2 have been reported in neuronal disease and its inhibition reduced neuro-inflammation. The levels of EPHX2 were significantly higher in BTBR brains than in B6 brains (Fig. 11).

AhR has been expressed in several regions of the brain and regulates the transcription of multiple genes through interaction with the xenobiotic-responsive element (XRE). Studies have found that AhR modulates the balance between regulatory and effector T cell functions and drives T cell differentiation of many diseases. Since AhR may play a major role in developmental neurotoxicity, we investigated the level of AhR in the brains of BTBR and B6 mice. Western blot analysis revealed a significant upregulation of AhR protein levels in BTBR brains compared to B6 brains (Fig. 11), which may indicate accelerated neurotoxicity in the brain of BTBR mice. Higher AhR levels may disturb brain formation with unbalanced differentiation causing functional and behavioral changes in BTBR mice.

TSLP is a protein belonging to the epithelial cytokine family. It is known to play an important role in the maturation of T cell populations through the activation of antigen-presenting cells. TSLP is also expressed in the brain and may enhance neurodegenerative disease. Proinflammatory cytokines, Th2-related cytokines, and IgE also induce or enhance TSLP production. Western blot analysis showed significantly higher TSLP protein levels in BTBR brains than in B6 brains (Fig. 11). Increased levels of TSLP in the brains of BTBR mice may relate to BTBR’s higher neuroinflammation and higher Th2 type T cell response compared to B6 mice (Heo et al. 2011; Uddin et al. 2020b).

Discussion

Numerous studies have indicated the immune system, which is affected by oxidative stress, has an impact on the development of autism, and an abnormal oxidative stress state has been reported for ASD patients, which may cause inflammation, alteration of immune cells, and effects on the pathogenesis and/or severity of ASD (Pangrazzi et al. 2020). Thus, we investigated the oxidative stress condition in the periphery as well as the brain of the BTBR mouse model of ASD. BTBR mice have behaviors that resemble ASD (McFarlane et al. 2008; Wöhr et al. 2011). In our previous studies and research from others, the important impact of immune alteration on ASD-like behaviors of BTBR mice has been noted, in that BTBR mice have a higher level of autoAbs to brain antigens and lower immune defenses against Listeria (Heo et al. 2011). BTBR mice also have higher levels of plasma cells and fewer B cells (Uddin et al. 2020a, b). Herein, oxidative stress and the expression of proteins known to influence immunity and/or brain functions were investigated.

Lipid peroxidation is a critical component of oxidative stress with which reactive oxygen species (ROS) target lipids containing carbon–carbon double bonds (polyunsaturated fatty acids, PUFAs). Increased level of malondialdehyde (MDA) content in the blood has been detected as a characteristic sign of lipid peroxidation in children with ASD (Liu et al. 2022). Children with ASD have a higher level of mitochondrial dysfunction, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) over replication, and mtDNA deletions than regular developing children, and those outcomes could significantly intensify brain dysfunction (Rose et al. 2018; Genovese and Butler 2020; Wang et al. 2022). Studies also reported mitochondrial dysfunction (MtD) and immune abnormalities may cause the development of ASD in children (Giulivi et al. 2010; Napoli et al. 2014; Rose et al. 2014). The BTBR mouse strain has been reported to have MtD (Yao et al. 2022). R-SH are important antioxidants, which would be able to lessen lipid peroxidation and MtD. We observed a reduced level of R-SH in T, B, NK, and NKT cells from BTBR mice. Extracellular and intracellular losses of R-SH in immune cells and sera of BTBR mice indicate a lower level of antioxidant capacity for the BTBR strain. With a diminished level of R-SH, there likely would be less ability to recover from any oxidative stress condition, which would further increase the inflammatory condition in BTBR mice.

The adaptive cellular immune functions in children with ASD may reflect dysfunctional immune functions, which may be linked to the behavioral disorders and other developmental functions (Ashwood et al. 2011). Various neurologic disorders are recognized as autoimmune diseases due to the presence of autoAbs specific for numerous brain antigens (Moscavitch et al. 2009; Steinman 2004). ASD individuals have higher amounts of total IgG Abs and brain Ag-specific autoAbs (Dalton et al. 2003; Wills et al. 2007). BTBR mice have a higher Th2 profile with elevated humoral immune responses, and due to an increased level of cytokines, antibodies and immune cells are highly susceptible to neuroinflammation (Silverman et al. 2015). Previously, we reported higher GATA3 expression in BTBR mice and increased numbers of Th2 cells (Zhang et al. 2013; Uddin et al. 2020b), which can induce higher plasma cell numbers and higher levels of serum antibody in BTBR mice (Uddin et al. 2020a, b) and in the brain of patients with ASD (Li et al. 2009). The BTBR brains did have high expression of GATA3 and TSLP.

Oxidative stress contributes to the development of inflammation and plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of numerous devastating diseases including neurodegenerative illness (Lugrin et al. 2014). With less intracellular and extracellular R-SH, there would be more cell death creating the potential release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). With DAMPs comes more cellular stress or tissue injury with more stimulation of inflammation by inducing pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of the innate immune system during the non-infectious inflammatory condition (Chen and Nuñez 2010). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can affect T helper 1 (Th1)/T helper 2 (Th2) cell and T helper 17 (Th17) cell/regulatory T cell (Treg) balance, and aberrant immune balance, especially low Treg activity, has significance in autoimmune diseases. CD4+ T helper cell subsets Th1/Th2 could contribute to autoimmune diseases (Mosmann et al. 1986). IFN-γ producing Th1 cells primarily function in cellular immunity, while IL-4/5/6/13-producing Th2 cells are more involved in humoral immunity. The Th1/Th2 balance works in both directions during autoimmune disease: for example, Th1 prevalence in RA (Schulze-Koops and Kalden 2001) and Th2 in SLE (Charles et al. 2010). Additionally, the Th17/Treg balance has a key role in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (Noack and Miossec 2014). Unified developing pathways enable the plasticity between Th17 and Treg phenotypes in multiple inflammatory (Sakaguchi et al. 2013) and oxidative (Moro-García et al. 2018; Jackson et al. 2004) diseases. In NOX2(NADPH oxidase)-deficient mice, the phenotype of T cell is skewed to the Th1 and Th17 lineages (Tse et al. 2010; Efimova et al. 2011). Additionally, Tregs from NOX2-deficient mice exercise much weaker inhibition of CD4+ effector T cells (Peterson et al. 1998), and antioxidant NAC or NOX inhibitors also encourage changes in the Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg balance. Previously, we reported that BTBR mice have a significantly lower ratio of Th1 cells compared to Th2 cells (Uddin et al. 2020b) and a lower level of Treg cells (Uddin et al. 2020b; Uddin et al. 2022), which might be because of the oxidative stress condition. Cytokines from antigen-presenting cells (APC) influence the Th1/Th2 differentiation from Th0 cells. Shortage of glutathione (GSH) in APC over a short time causes inhibition of Th1-associated cytokines and enhances Th2-associated cytokine production (Peterson et al. 1998). Similarly, H2O2 can prevent IFN-γ production in activated Th1 cells and enhance IL-4 production by the Th2 cell (Frossi et al. 2008). The reduced GSH/GSSG ratio and the level of intracellular glutathione (iGSH) in BTBR mice further suggest that the oxidative stress condition might contribute to altered ASD-like behavior.

Oxidative stress can cause chronic inflammatory diseases, and high levels of ROS can trigger signaling pathways to secrete higher amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Chan 2001). T cells present in the brain and brain microglia cells may secrete pro-inflammatory molecules, in a malicious cycle of inflammation–oxidative stress–inflammation (Popa-Wagner et al. 2013). In ASD, ROS accumulation from oxidized proteins and lipid peroxidation may directly stimulate neuroinflammation causing cell death and neurodegeneration (Popa-Wagner et al. 2013). Furthermore, protein oxidation may induce the secretion of peroxiredoxin 2 (PRDX2), a known inflammatory signal functioning as a redox-dependent inflammatory mediator, that triggers macrophages to produce TNF (Salzano et al. 2014). Additionally, lower levels of GSH lead to higher ROS production, which directly stimulates inflammation (Ghezzi 2011). Oxidative stress can also cause inflammation in the brain consequently affecting neuronal damage (Shemer et al. 2015). Studies have reported inflammatory mediators may be secreted by microglia and astrocytes during an oxidative stress event (Chiurchiù and Maccarrone 2011; Fischer and Maier 2015; Voet et al. 2019). Moreover, T cells that have infiltrated into CNS may play a critical role in causing neuroinflammation (Smolders et al. 2018; Daglas et al. 2019). Importantly, pro-inflammatory molecules produced by brain microglia cells or brain-infiltrated T cells may link to brain functions through the increased level of ROS (Dulken et al. 2019). A similar condition may exist in the brains of ASD individuals and the brains of BTBR mice.

The PTEN gene has been cited to be a potential cause of ASD (Napoli et al. 2012; Herman et al. 2007). When defective, the PTEN protein interacts with Tp53 to dampen energy production in neurons. Deficient PTEN-Tp53 signaling may lead to severe stress with a spike in harmful mitochondrial DNA changes and abnormal levels of energy production in the cerebellum and hippocampus, brain regions critical for social behavior and cognition (Napoli et al 2012). However, the PTEN level was higher in BTBR brains suggesting it may be mutated or unable to properly signal with Tp53 since the BTBR mice have MtD (Ahn et al 2020; Yao et al 2022). Transglutaminase 2 (TGM2) is a stress-induced gene and is known to contribute to brain injury and numerous neurodegenerative diseases including multiple sclerosis (Crider et al. 2018; Jeitner et al. 2009). IRE1α is known for its function as an ER stress sensor governing the unfolded protein response to ER stress (Kumar and Maity 2021). Furthermore, there is an indication that the stimulation of IRE1α intensifies the histopathological advancement of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Duran-Aniotz et al. 2017). The inhibition of the IRE1α pathway in AD protects mitochondrial function by controlling the malfunction of mitochondria-associated ER-membranes (MAMs) (Chu et al. 2021). Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) is a stress-responsive cytokine and its expression is linked to oxidative stress, inflammation, and hormonal changes (Adela and Banerjee 2015; Wischhusen et al. 2020). In the BTBR brain, the expressions of PTEN, TGM2, IRE1α, and GDF15 support an oxidative stress state, which further exacerbates the inflammatory condition.

Metallothionein (MT) induction was observed in different regions of the brain due to stress (Jacob et al. 1999), and MT plays a role in inflammatory diseases and can shape innate and adaptive immunity (Dai et al. 2021). MT expression in the brain may also recruit immune cells to enter the brain since it has chemotactic activity (Yin et al. 2005). Under inflammatory conditions, MT may exert effects through interactions with the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and with a low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) (Bhandari 1989). Presently, there are no reports characterizing CXCR4 in the BTBR brain but it is possible that an increased level of MT might contribute to the leukocyte trafficking (Uddin et al. 2022; Yin et al. 2005) in the BTBR brain. MT has been implicated in brain inflammation and damage (Manso et al 2011; Juárez-Rebollar et al 2017).

GATA3 is involved in the development of the brain and regulates cell differentiation and synthesis of neurotransmitters and hormones (van Doorninck et al. 1999). GATA3 also controls the expression of numerous inflammatory cytokines and promotes the secretion of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 from Th2 cells in humans and has similar actions on comparable mouse lymphocytes (Zhu et al. 2006), which could promote the higher production of Abs including autoAbs. EPHX2 has been described in neuro-inflammation (Ghosh et al. 2020) and AhR is involved in brain toxicity (Akahoshi et al. 2006). TSLP expression is linked to many conditions including asthma (Ying et al. 2005), inflammatory arthritis (Koyama et al. 2007), and atopic dermatitis (Ebner et al. 2007). Our study found that BTBR brains had elevated levels of GATA3, EPHX2, AHR, and TSLP, which in turn could underlie the ASD-like phenotypes in BTBR mice.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that BTBR mice have a lower level of surface R-SH on the lymphocyte, granulocyte, and monocyte populations including CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, B cell, NK cell, NKT, and CD11b+ immune cells. The level of sera R-SH and intracellular glutathione was also reduced in BTBR mice. Additionally, GATA3, TGM2, AHR, EPHX2, TSLP, PTEN, IRE1alpha, GDF15, and MT were shown to have elevated levels in BTBR mice compared to B6 mice. The altered immune oxidative stress state is suggested to cause the irregularities in brain development that in turn result in the ASD-like behaviors observed in the BTBR mouse; however, more studies are required to understand the connection more fully between the molecular/cellular abnormalities and how they directly or indirectly result in the ASD-like behaviors of BTBR mice.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Michael Lynes (University of Connecticut Storrs) for his monoclonal antibody (UC1MT) to metallothionein.

Abbreviations

- Ab

Antibody

- AFM

Alexa Fluor™ 488 C5 Maleimide

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorders

- AhR

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- B6

C57BL/6 J

- CNS

Central nervous system

- GSSG

Glutathione disulfide

- iGSH

Intracellular glutathione

- GMFI

Geometric mean fluorescent intensity

- MT

Metallothionein

- R-SH

Thiol

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- TGM2

Transglutaminase 2

- IRE1α

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1alpha

- GDF15

Growth differentiation factor 15

- EPHX2

Epoxide hydrolases

- TSLP

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- XRE

Xenobiotic-responsive element

Funding

The study was funded by a grant to DAL from NIEHS R01ES025584.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adela R, Banerjee SK (2015) GDF-15 as a target and biomarker for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases: a translational prospective. J Diabetes Res 2015:490842. 10.1155/2015/490842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ahmad SF, Zoheir KMA, Ansari MA, Nadeem A, Bakheet SA, Al-Ayadhi LY, Alzahrani MZ, Al-Shabanah OA, Al-Harbi MM, Attia SM. Dysregulation of Th1, Th2, Th17, and T regulatory cell-related transcription factor signaling in children with autism. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(6):4390–4400. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn Y, Sabouny R, Villa BR, Yee NC, Mychasiuk R, Uddin GM, Rho JM, Shutt TE. Aberrant mitochondrial morphology and function in the BTBR mouse model of autism is improved by Two weeks of ketogenic diet. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3266. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akahoshi E, Yoshimura S, Ishihara-Sugano M. Over-expression of AhR (aryl hydrocarbon receptor) induces neural differentiation of Neuro2a cells: neurotoxicology study. Environ Health. 2006;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz-Picciotto I, Hansen R, Pessah IN, Van de Water J (2011) Altered T cell responses in children with autism. Brain Behav Immun 25(5)840-849. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baeke F, Takiishi T, Korf H, Gysemans C, Mathieu C. Vitamin D: modulator of the immune system. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(4):482–496. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari S (1989) “The chemotactic role of metallothionein in the extracellular environment” (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1989

- Birben E, Sahiner UM, Sackesen C, Erzurum S, Kalayci O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5(1):9–19. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182439613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørklund G, Tinkov AA, Hosnedlová B, Kizek R, Ajsuvakova OP, Chirumbolo S, Skalnaya MG, Peana M, Dadar M, El-Ansary A, Qasem H, Adams JB, Aaseth J, Skalny AV. The role of glutathione redox imbalance in autism spectrum disorder: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;160:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund G, Saad K, Chirumbolo S, Kern JK, Geier DA, Geier MR, Urbina MA (2016) Immune dysfunction and neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorder. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 76(4):257–268. 10.21307/ane-2017-025 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Careaga M, Schwartzer J, Ashwood P. Inflammatory profiles in the BTBR mouse: how relevant are they to autism spectrum disorders? Brain Behav Immun. 2015;43:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PH. Reactive oxygen radicals in signaling and damage in the ischemic brain. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metabolism. 2001;21(1):2–14. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles N, Hardwick D, Daugas E, Illei GG, Rivera J. Basophils and the T helper 2 environment can promote the development of lupus nephritis. Nat Med. 2010;16(6):701–707. doi: 10.1038/nm.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Audhya T, Chauhan V. Brain region-specific glutathione redox imbalance in autism. Neurochem Res. 2012;37(8):1681–1689. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, Nuñez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(12):826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Shi XJ, Liu H, Mao X, Gui LN, Wang H, Cheng Y. Oxidative stress marker aberrations in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 87 studies (N = 9109) Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):15. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiurchiù V, Maccarrone M. Chronic inflammatory disorders and their redox control: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxidant Redox Signal. 2011;15(9):2605–2641. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B, Li M, Cao X, Li R, Jin S, Yang H, Xu L, Wang P, Bi J (2021) IRE1α-XBP1 Affects the mitochondrial function of Aβ25–35-treated SH-SY5Y cells by regulating mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Front Cell Neurosci 15:614556. 10.3389/fncel.2021.614556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crider A, Davis T, Ahmed AO, Mei L, Pillai A. Transglutaminase 2 induces deficits in social behavior in mice. Neural Plast. 2018;2018:2019091. doi: 10.1155/2018/2019091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daglas M, Draxler DF, Ho H, McCutcheon F, Galle A, Au AE, Larsson P, Gregory J, Alderuccio F, Sashindranath M, Medcalf RL. Activated CD8+ T cells cause long-term neurological impairment after traumatic brain injury in mice. Cell Rep. 2019;29(5):1178–1191.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Wang L, Li L, Huang Z, Ye L (2021) Metallothionein 1: a new spotlight on inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 12:739918. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.739918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dalton P, Deacon R, Blamire A, Pike M, McKinlay I, Stein J, Styles P, Vincent A. Maternal neuronal antibodies associated with autism and a language disorder. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(4):533–537. doi: 10.1002/ana.10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deponte M. The incomplete glutathione puzzle: just guessing at numbers and figures? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;27(15):1130–1161. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D, Zielke HR, Yeh D, Yang P. Cellular stress and apoptosis contribute to the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2018;11(7):1076–1090. doi: 10.1002/aur.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulken BW, Buckley MT, Navarro Negredo P, Saligrama N, Cayrol R, Leeman DS, George BM, Boutet SC, Hebestreit K, Pluvinage JV, Wyss-Coray T, Weissman IL, Vogel H, Davis MM, Brunet A. Single-cell analysis reveals T cell infiltration in old neurogenic niches. Nature. 2019;571(7764):205–210. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis ML, Pagano MT, Pierdominici M, Ortona E. The role of vitamin D in autoimmune diseases: could sex make the difference? Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13293-021-00358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Aniotz C, Cornejo VH, Espinoza S, Ardiles ÁO, Medinas DB, Salazar C, Foley A, Gajardo I, Thielen P, Iwawaki T, Scheper W, Soto C, Palacios AG, Hoozeman JJM, Hetz C. IRE1 signaling exacerbates Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134(3):489–506. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner S, Nguyen VA, Forstner M, Wang YH, Wolfram D, Liu YJ, Romani N. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin converts human epidermal Langerhans cells into antigen-presenting cells that induce proallergic T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(4):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimova O, Szankasi P, Kelley TW (2011) Ncf1 (p47phox) is essential for direct regulatory T cell mediated suppression of CD4+ effector T cells. PloS One 6(1):e16013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- El-Ansary A, Al-Ayadhi L. Lipid mediators in plasma of autism spectrum disorders. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:160. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Shan L, Du L, Wang B, Li H, Wang W, Wang T, Dong H, Yue X, Xu Z, Staal WG, Jia F. Clinical improvement following vitamin D3 supplementation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutr Neurosci. 2017;20(5):284–290. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2015.1123847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer R, Maier O (2015) Interrelation of oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease: role of TNF. Oxid Med Cell Longevity 2015:610813. 10.1155/2015/610813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Freedman R, Hunter SK, Law AJ, Clark AM, Roberts A, Hoffman MC. Choline, folic acid, Vitamin D, and fetal brain development in the psychosis spectrum. Schizophr Res. 2022;247:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frossi B, De Carli M, Piemonte M, Pucillo C. Oxidative microenvironment exerts an opposite regulatory effect on cytokine production by Th1 and Th2 cells. Mol Immunol. 2008;45(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye RE, James SJ. Metabolic pathology of autism in relation to redox metabolism. Biomark Med. 2014;8(3):321–330. doi: 10.2217/bmm.13.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese A, Butler MG. Clinical assessment, genetics, and treatment approaches in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(13):4726. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi P. Role of glutathione in immunity and inflammation in the lung. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:105–113. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S15618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Comerota MM, Wan D, Chen F, Propson NE, Hwang SH, Hammock BD, Zheng H (2020) An epoxide hydrolase inhibitor reduces neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med 12(573):eabb1206. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Giulivi C, Zhang YF, Omanska-Klusek A, Ross-Inta C, Wong S, Hertz-Picciotto I, Tassone F, Pessah IN. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism. JAMA. 2010;304(21):2389–2396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu F, Chauhan V, Chauhan A. Impaired synthesis and antioxidant defense of glutathione in the cerebellum of autistic subjects: alterations in the activities and protein expression of glutathione-related enzymes. Free Rad Biol Med. 2013;65:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase H, Rink L. Signal transduction in monocytes: the role of zinc ions. Biometals. 2007;20(3–4):579–585. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo Y, Zhang Y, Gao D, Miller VM, Lawrence DA (2011) Aberrant immune responses in a mouse with behavioral disorders. PloS one 6(7):e20912. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herman GE, Butter E, Enrile B, Pastore M, Prior TW, Sommer A. Increasing knowledge of PTEN germline mutations: two additional patients with autism and macrocephaly. Am J Med Genetics Part A. 2007;143A(6):589–593. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskusnykh IY, Zakharova AA, Pathak D (2022) Glutathione in brain disorders and aging. Molecules 27(1):324. 10.3390/molecules27010324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jackson SH, Devadas S, Kwon J, Pinto LA, Williams MS. T cells express a phagocyte-type NADPH oxidase that is activated after T cell receptor stimulation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(8):818–827. doi: 10.1038/ni1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob ST, Ghoshal K, Sheridan JF. Induction of metallothionein by stress and its molecular mechanisms. Gene Expr. 1999;7(4–6):301–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeitner TM, Muma NA, Battaile KP, Cooper AJ. Transglutaminase activation in neurodegenerative diseases. Future Neurol. 2009;4(4):449–467. doi: 10.2217/fnl.09.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F, Wang B, Shan L, Xu Z, Staal WG, Du L. Core symptoms of autism improved after vitamin D supplementation. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e196–e198. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juárez-Rebollar D, Rios C, Nava-Ruíz C, Méndez-Armenta M. Metallothionein in brain disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:5828056. doi: 10.1155/2017/5828056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin I, Borggraefe I, Catarino CB, Kuhm C, Hoertnagel K, Biskup S, Opladen T, Blau N, Heinen F, Klopstock T. Folinic acid therapy in cerebral folate deficiency: marked improvement in an adult patient. J Neurol. 2017;264(3):578–582. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitic M, Wimmer I, Adzemovic M, Kögl N, Rudel A, Lassmann H, Bradl M. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is expressed in the intact central nervous system and upregulated in the myelin-degenerative central nervous system. Glia. 2014;62(7):1066–1074. doi: 10.1002/glia.22662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama K, Ozawa T, Hatsushika K, Ando T, Takano S, Wako M, Suenaga F, Ohnuma Y, Ohba T, Katoh R, Sugiyam H, Hamada Y, Ogawa H, Okumura K, Nakao A. A possible role for TSLP in inflammatory arthritis. Biochem Biophysical Res Com. 2007;357(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Maity S. ER stress-sensor proteins and ER-mitochondrial crosstalk-signaling beyond (ER) stress response. Biomol. 2021;11(2):173. doi: 10.3390/biom11020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose JMT, Benitez JA, Roberts AJ, Reed R, Bintig LME, Sachdev RNS, Furnari F, Eickholt BJ. The impact of phosphorylated PTEN at threonine 366 on cortical connectivity and behaviour. Brain. 2022;145(10):3608–3621. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PW, Selhorst A, Lampe SG, Liu Y, Yang Y, Lovett-Racke AE. Neuron-specific vitamin D signaling attenuates microglia activation and CNS autoimmunity. Front Neurol. 2020;11:19. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Chauhan A, Sheikh AM, Patil S, Chauhan V, Li XM, Ji L, Brown T, Malik M. Elevated immune response in the brain of autistic patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;207(1–2):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Lin J, Zhang H, Khan NU, Zhang J, Tang X, Cao X, Shen L (2022) Oxidative stress in autism spectrum disorder-current progress of mechanisms and biomarkers. Front Psychiatry 13:813304. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.813304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lugrin J, Rosenblatt-Veli N, Parapanov R, Liaudet L. The role of oxidative stress during inflammatory processes. Biol Chem. 2014;395(2):203–230. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lushchak VI (2012) Glutathione homeostasis and functions: potential targets for medical interventions. J Amino Acids, 2012:736837. 10.1155/2012/736837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maares M, Haase H. Zinc and immunity: an essential interrelation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;611:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Durkin MS, Esler A, Furnier SM, Hallas L, Hall-Lande J, Hudson A, Hughes MM, Patrick M, Pierce K, Poynter JN, Salinas A, Shenouda J, Vehorn A, Warren Z, Constantino JN, DiRienzo M, Fitzgerald RT, Grzybowski A, Spivey MH, Pettygrove S, Zahorodny W, Ali A, Andrews JG, Baroud T, Gutierrez J, Hewitt A, Lee LC, Lopez M, Mancilla KC, McArthur D, Schwenk YD, Washington A, Williams S, Cogswell ME (2021) Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ 70(11):1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Manso Y, Adlard PA, Carrasco J, Vašák M, Hidalgo J. Metallothionein and brain inflammation. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011;16:1103. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0802-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane HG, Kusek GK, Yang M, Phoenix JL, Bolivar VJ, Crawley JN. Autism-like behavioral phenotypes in BTBR T+tf/J mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7(2):152–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguid NA, Bjørklund G, Gebril OH, Doşa MD, Anwar M, Elsaeid A, Gaber A, Chirumbolo S. The role of zinc supplementation on the metallothionein system in children with autism spectrum disorder. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119(4):577–583. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro-García MA, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Alonso-Arias R. Influence of inflammation in the process of T lymphocyte differentiation: proliferative, metabolic, and oxidative changes. Front Iimmunol. 2018;9:339. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscavitch SD, Szyper-Kravitz M, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune pathology accounts for common manifestations in a wide range of neuro-psychiatric disorders: the olfactory and immune system interrelationship. Clin Immunol. 2009;130(3):235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL (1986) Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol 136(7):2348–2357 [PubMed]

- Nadeem A, Ahmad SF, Al-Harbi NO, Attia SM, Alshammari MA, Alzahrani KS, Bakheet SA. Increased oxidative stress in the cerebellum and peripheral immune cells leads to exaggerated autism-like repetitive behavior due to deficiency of antioxidant response in BTBR T + tf/J mice. Prog Neuro-Psychopharm Biol Psychiatry. 2019;89:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem A, Ahmad SF, Attia SM, Al-Ayadhi LY, Al-Harbi NO, Bakheet SA (2020) Dysregulation in IL-6 receptors is associated with upregulated IL-17A related signaling in CD4+ T cells of children with autism. Prog Neuro-psychopharmacology Biological Psychiatry 97:109783. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109783 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Napoli E, Wong S, Hertz-Picciotto I, Giulivi C. Deficits in bioenergetics and impaired immune response in granulocytes from children with autism. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1405–e1410. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli E, Ross-Inta C, Wong S, Hung C, Fujisawa Y, Sakaguchi D, Angelastro J, Omanska-Klusek A, Schoenfel, R, Giulivi C (2012) Mitochondrial dysfunction in Pten haplo-insufficient mice with social deficits and repetitive behavior: interplay between Pten and p53. PloS one, 7(8), e42504. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Noack M, Miossec P. Th17 and regulatory T cell balance in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(6):668–677. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangrazzi L, Balasco L, Bozzi Y. Oxidative stress and immune system dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3293. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti S, Mariano M, Mazzocchetti C, Mazza M, Pino MC, Verrotti Di Pianella A, Valenti M. Diet: the keystone of autism spectrum disorder? Nutr Neurosci. 2019;22(12):825–839. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2018.1464819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JD, Herzenberg LA, Vasquez K, Waltenbaugh C. Glutathione levels in antigen-presenting cells modulate Th1 versus Th2 response patterns. Proc National Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(6):3071–3076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantone D, Prmiano G, Manco C, Locci S, Servidei S, De Stefano N. Vitamin D in neurological diseases. Int j Mol Sci. 2022;24(1):87. doi: 10.3390/ijms24010087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa-Wagner A, Mitran S, Sivanesan S, Chang E, Buga AM (2013) ROS and brain diseases: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Oxidat Med Cell Longevity 2013:963520. 10.1155/2013/963520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ramaekers VT, Sequeira JM, Thöny B, Quadros EV. Oxidative stress, folate receptor autoimmunity, and CSF findings in severe infantile autism. Autism Res Treat. 2020;2020:9095284. doi: 10.1155/2020/9095284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S, Niyazov DM, Rossignol DA, Goldenthal M, Kahler SG, Frye RE. Clinical and molecular characteristics of mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder. Mol Diagn Ther. 2018;22(5):571–593. doi: 10.1007/s40291-018-0352-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S, Frye RE, Slattery J, Wynne R, Tippett M, Pavliv O, Melnyk S, James SJ (2014) Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial dysfunction in a subset of autism lymphoblastoid cell lines in a well-matched case control cohort. PloS One 9(1):e85436. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rout UK, Clausen P. Common increase of GATA-3 level in PC-12 cells by three teratogens causing autism spectrum disorders. Neurosci Res. 2009;64(2):162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad K, Abdel-Rahman AA, Elserogy YM, Al-Atram AA, Cannell JJ, Bjørklund G, Abdel-Reheim MK, Othman HA, El-Houfey AA, Abd El-Aziz NH, Abd El-Baseer KA, Ahmed AE, Ali AM. Vitamin D status in autism spectrum disorders and the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in autistic children. Nutr Neurosci. 2016;19(8):346–351. doi: 10.1179/1476830515Y.0000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Vignali DA, Rudensky AY, Niec RE, Waldmann H. The plasticity and stability of regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):461–467. doi: 10.1038/nri3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzano S, Checconi P, Hanschmann EM, Lillig CH, Bowler LD, Chan P, Vaudry D, Mengozzi M, Coppo ., Sacre S, Atkuri KR, Sahaf B, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA, Mullen L, Ghezzi P (2014) Linkage of inflammation and oxidative stress via release of glutathionylated peroxiredoxin-2, which acts as a danger signal. Proc National Acad Sci USA 111(33):12157-1216210.1073/pnas.1401712111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schulze-Koops H, Kalden JR. The balance of Th1/Th2 cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Best Practice & Research Clin Rheum. 2001;15(5):677–691. doi: 10.1053/berh.2001.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemer A, Erny D, Jung S, Prinz M. Microglia plasticity during health and disease: an immunological perspective. Trend Immunol. 2015;36(10):614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JL, Pride MC, Hayes JE, Puhger KR, Butler-Struben HM, Baker S, Crawley JN. GABAB receptor agonist r-baclofen reverses social deficits and reduces repetitive behavior in two mouse models of autism. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;40(9):2228–2239. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolders J, Heutinck KM, Fransen NL, Remmerswaal EBM, Hombrin P, Ten Berge IJM, van Lier RAW, Huitinga I, Hamann J. Tissue-resident memory T cells populate the human brain. Nat Comm. 2018;9(1):4593. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L. Elaborate interactions between the immune and nervous systems. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(6):575–581. doi: 10.1038/ni1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szodoray P, Nakken B, Gaal J, Jonsson R, Szegedi A, Zold E, Szegedi G, Brun JG, Gesztelyi R, Zeher M, Bodolay E. The complex role of vitamin D in autoimmune diseases. Scand J Immunol. 2008;68(3):261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Yang T, Zhu J, Li Q, Lai X, Li Y, Tang T, Chen J, Li T. Maternal folic acid and micronutrient supplementation is associated with vitamin levels and symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorders. Reprod Toxicol. 2020;91:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2019.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse HM, Thayer TC, Steele C, Cuda CM, Morel L, Piganelli JD, Mathews CE. NADPH oxidase deficiency regulates Th lineage commitment and modulates autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2010;185(9):5247–5258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin MN, Yao Y, Mondal T, Matala R, Manley K, Lin Q, Lawrence DA (2020a) Immunity and autoantibodies of a mouse strain with autistic-like behavior. Brain Behav Immun Health, 4:100069. 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Uddin MN, Yao Y, Manley K, Lawrence DA (2020b) Development, phenotypes of immune cells in BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J mice. Cell Immunol. 358:104223. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104223 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Uddin MN, Manley K, Lawrence DA (2022) Altered meningeal immunity contributing to the autism-like behavior of BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J mice. Brain Behav Immun Health 26:100563. 10.1016/j.bbih.2022.100563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- van Doorninck JH, van Der Wees J, Karis A, Goedknegt E, Engel JD, Coesmans M, Rutteman M, Grosveld F, De Zeeuw CI (1999) GATA-3 is involved in the development of serotonergic neurons in the caudal raphe nuclei. J Neurosci 19(12):RC12. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-j0002.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Voet S, Prinz M, van Loo G. Microglia in central nervous system inflammation and multiple sclerosis pathology. Trend Mol Med. 2019;25(2):112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Shan L, Du L, Feng J, Xu Z, Staal WG, Jia F. Serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(4):341–350. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Guo X, Hong X, Wang G, Pearson C, Zuckerman B, Clark AG, O'Brien KO, Wang X, Gu Z. Association of mitochondrial DNA content, heteroplasmies and inter-generational transmission with autism. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3790. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30805-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills S, Cabanlit M, Bennett J, Ashwood P, Amaral D, Van de Water J (2007) Autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Ann New York Acad Sci 1107:79–91.10.1196/annals.1381.009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wischhusen J, Melero I, Fridman WH. Growth/differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15): from biomarker to novel targetable immune checkpoint. Front Immunol. 2020;11:951. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöhr M, Roullet FI, Crawley JN. Reduced scent marking and ultrasonic vocalizations in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Uddin MN, Manley K, Lawrence DA (2022) Improvements of autism-like behaviors but limited effects on immune cell metabolism after mitochondrial replacement in BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J mice. J Neuroimmunol 368:577893. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577893 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yin X, Knecht DA, Lynes MA. Metallothionein mediates leukocyte chemotaxis. BMC Immunol. 2005;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying S, O'Connor B, Ratoff J, Meng Q, Mallett K, Cousins D, Robinson D, Zhang G, Zhao J, Lee TH, Corrigan C. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression is increased in asthmatic airways and correlates with expression of Th2-attracting chemokines and disease severity. J Immunol. 2005;174(12):8183–8190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gao D, Kluetzman K, Mendoza A, Bolivar VJ, Reilly A, Jolly JK, Lawrence DA. The maternal autoimmune environment affects the social behavior of offspring. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;258(1–2):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.02.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Yamane H, Cote-Sierra J, Guo L, Paul WE. GATA-3 promotes Th2 responses through three different mechanisms: induction of Th2 cytokine production, selective growth of Th2 cells and inhibition of Th1 cell-specific factors. Cell Res. 2006;16(1):3–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]