Abstract

This was the first study to evaluate procedures for teaching leg shaving to individuals with disabilities. Using a video prompting teaching package in a concurrent multiple baseline design across participants with different diagnoses (i.e., paraplegia, Down Syndrome, and intellectual disability), all participants learned to shave their legs and maintained responding two weeks post-intervention.

Keywords: leg shaving, video prompting

Independence with self-care tasks is important for people with disabilities because it may improve quality of life for both them and their caregivers (Mays & Heflin, 2011). Although many individuals choose to shave their legs, some adults with disabilities may not have this option due to safety concerns or lack of effective teaching procedures. For individuals who prefer to have shaved legs, learning to independently shave may increase their satisfaction with their appearance, allow for increased privacy (Williamson, 2015), and provide comfort when participating in certain activities (e.g., swimming). Research to date has predominantly focused on teaching beard shaving or other self-care skills, and few studies have taught self-care skills to women with disabilities (e.g., feminine hygiene; Veazey et al., 2016). To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated procedures for teaching leg shaving.

Video modeling has been effective in teaching a variety of daily living chains (e.g., Rosenberg et al., 2010; Shipley-Benamou et al., 2002) and offers advantages, including capturing naturalistic interactions and environments that are difficult to simulate in clinical settings, providing a consistent model, and providing recordings that can be reused across clients (Charlop-Christy et al., 2000). Point-of-view (POV) video modeling (i.e., recorded from the participant’s perspective) and video prompting (VP; steps divided into shorter clips; Sigafoos et al., 2007) have been used to teach complex behavior chains. Gardner and Wolfe (2015) used POV VP with error correction to teach four adolescents with developmental disabilities to wash dishes. After watching the video model, if the participant did not respond within 30 s of the instruction, “Now you do it,” or responded incorrectly, error correction included least-to-most prompts in the sequence: second presentation of VP, model prompt, and manual prompt.

Although teaching leg shaving to individuals with disabilities may be a socially valid goal, there is currently no research to assist clinicians. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to evaluate the effects of an intervention package that included VP with error correction and reinforcement (with components based on Gardner & Wolfe, 2015) to teach leg shaving to women with developmental disabilities. Barriers to individuals with disabilities learning leg shaving may include: the fine motor skills necessary to manage water, shaving cream, and the razor blade, and risk of injury from a razor blade. To address these issues, we taught participants to use the Finishing Touch Flawless Legs™ shaving device because (a) it can be used without water or shaving cream; (b) individuals with fine motor deficits can safely handle the device; and (c) the device does not have a sharp blade that can injure the user. An additional barrier when teaching shaving may be the multitude of similar steps. That is, because the sections to be shaved are similar to each other, finishing one section may not function as a strong discriminative stimulus for shaving the next section. To address this issue, we created a task analysis with pictures of legs divided into zones (for instructor use) and used POV VP to teach the task analysis. Post-intervention probes were included to examine whether fading the video prompts and thinning reinforcement was necessary. We also conducted maintenance probes and assessed generalization and social validity.

Method

Participants and Setting

Three women with disabilities between 22 and 56 years old participated in the study. Allison was a 22-year-old woman diagnosed with Down Syndrome who lived with her parents. Lydia was a 32-year-old woman diagnosed with intellectual disability and schizoaffective disorder who lived with her parents. Lorraine was a 56-year-old woman with paraplegia from an acquired spinal cord injury who lived by herself. None of the participants had exposure to video modeling as an intervention. All participants were included because they expressed interest in learning to shave independently. To be included in the study, all participants could hold the shaver, tolerate the vibration and sound of the shaver, and engage in at least one other chain of behavior independently for 2 min (skills assessment described below). We assessed assent by asking each participant if they were interested in shaving their legs, when they would like to have sessions, and where they would like to practice. We conducted sessions at the participant’s preferred times and at least four times per week to ensure enough practice opportunities. Sessions were conducted in the home based on their preference: basement entertainment room (Allison), bedroom (Lydia), and lounge (Lorraine).

Materials

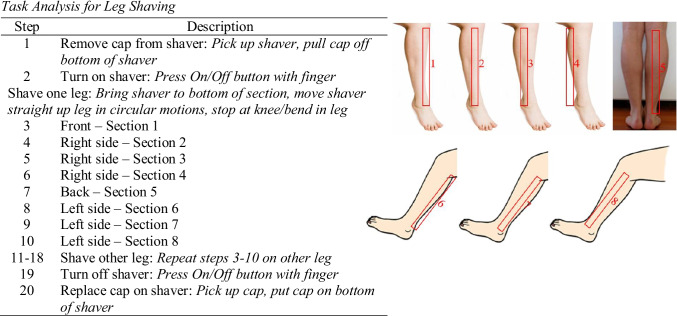

Each participant was given a Finishing Touch Flawless Legs™ device. At the start and end of every session, the experimenter cleaned the device with a towel. A laptop computer was used to play the video prompts. All sessions were video recorded for subsequent data collection. Three preferred items/activities were identified for each participant via a multiple stimulus without replacement preference assessment (MSWO; DeLeon & Iwata, 1996). A token board with 20 3.175-cm buttons with Velcro® was used for reinforcement. Video prompts were used as model prompts for each step in the leg-shaving task-analysis (Table 1). The VPs were recorded on a downward angle over the model’s shoulder to simulate the participant’s POV while shaving (Gardner & Wolfe, 2015). The VPs (20 total) ranged in length from 5 s to 18 s (M = 9.2 s) for each step in the chain. There was no voice-over instruction.

Table 1.

Task Analysis for Leg Shaving

Pre-experimental Procedures

Prior to the study, all participants demonstrated the following skills without prompts or errors: grasping and holding the shaver while it was turned off, holding the shaver while it was turned on (i.e., vibrating), a 2-min daily living task with multiple steps, and imitation of three different gross motor skills within 10 s from a video model. Additionally, because none of the participants had previously used token systems, prior to the study, we exposed each participant to the token system by asking them to imitate various gross motor actions, delivering tokens, and providing backup reinforcers. Specific procedures available upon request.

Data Collection

Data were collected on independent, correct completion of each step of the shaving task analysis and summarized as the percentage of independent, correct steps per session. A step was scored as independent and correct if the participant initiated the step within 10 s of the end of the VP (or within 10 s of completing the previous step) and accurately completed the behavior described in the step (see Table 1 for the task analysis).

Data were also collected on an Outcome Rating Assessment (ORA) for Lydia and Allison. These data were based on caregiver report of the amount of leg hair remaining at the end of a session. After the session, the experimenter asked the caregiver, “In your opinion, how well do you think (the participant) shaved her legs today based on the amount of hair, or no hair, remaining on her legs?” The question was based on a 5-point Likert-type scale (i.e., 1 = not well at all, 2 = not well, 3 = neutral, 4 = well, 5 = very well).

Experimental Design and Procedure

A concurrent multiple-baseline design across participants was used to assess the effectiveness of the intervention.

Pre-intervention

Prior to each session, the participant selected one item from the top three items identified in the MSWO. Next, the experimenter, sitting adjacent to the participant, presented the shaver and said, “Shave your legs.” No prompts, error correction, or programmed consequences were delivered contingent upon shaving behaviors. When the participant did not interact with the device for 30 s or indicated that she was finished, the experimenter ended the session and provided access to the selected item.

Intervention: Total-task presentation, POV VP, reinforcement, error correction

Intervention sessions were identical to pre-intervention, with the following exceptions. The experimenter placed the computer and token board in front of the participant and played the VP for Step 1 in the task analysis. If a participant attempted to begin the step before the VP concluded, the experimenter said, “Watch the video all the way through first.” If the participant imitated the VP correctly, the experimenter placed a token on the token board and then played the VP for Step 2. Similar to Gardner and Wolfe (2015), errors of commission or omission resulted in the experimenter implementing an error correction procedure in a least-to-most prompt hierarchy. If the participant did not respond after 10 s, the experimenter said, “Now you try.” If the participant responded incorrectly, or did not respond a second time, the experimenter said, “That’s not quite right. Here, let’s watch the video again” and replayed the video prompt. If the participant responded incorrectly or did not respond a third time, the experimenter would have replayed the VP and provided a manual prompt to correctly complete the step. Once the participant completed all 20 steps, she was given the preferred item.

Post-intervention

When the participant correctly and independently completed all 20 steps across three consecutive sessions, post-intervention probes, in which video prompts and reinforcement were removed, were conducted. Criterion for mastery was three consecutive post-intervention probes with 100% independent, correct completion of all steps in the task analysis.

Generalization and Maintenance

Generalization probes were completed during pre- and post-intervention conditions by the participant’s caregiver (Lydia, Allison). After reaching mastery, caregivers were asked to provide the participant the opportunity to shave at least twice a week, under pre-intervention conditions. The experimenter returned to the participant’s residence 2 weeks following mastery and conducted a maintenance probe under pre-intervention conditions (and without preferred items).

Social Validity

Social validity was assessed by asking Lydia’s and Allison’s caregivers to complete a modified Treatment Acceptability and Rating Form-Revised (TARF-R, Reimers & Wacker, 1988). Questions were based on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all acceptable, 4 = neutral, 7 = very acceptable). We also asked participants to share their opinions throughout and following completion of the study.

Interobserver Agreement (IOA) and Procedural Integrity (PI)

Independent observers scored secondary data during 33% of randomly selected sessions across all conditions for all participants. IOA was calculated by dividing the number of agreements (both data collectors scoring a plus or minus for each step) by the total number of task-analysis steps, multiplied by 100. Mean IOA was 100% for Allison, 99.1% (range = 97.4%–100%) for Lydia, and 98% (range = 92.1%–100%) for Lorraine. PI was assessed by an independent observer for 33% of randomly selected sessions across all conditions for each participant. Procedural integrity was calculated by dividing the total number of steps completed accurately (correct presentation of materials, instructions, videos, manual prompts, error correction, and delivery of consequences) by the total number of steps, and multiplying by 100. Mean PI was a minimum of 80% across participants (range = 77%–100%).

Results

Figure 1 shows responding during pre- and post-intervention, intervention, generalization probes, and maintenance for all participants. For Allison, during pre-intervention, correct completion of the task analysis steps was near zero, and her caregiver scored her shaving as a 1 (i.e., not well at all) on the ORA. During the intervention, she reached criterion within seven sessions, and her caregiver scored her shaving as 5 (i.e., very well). Manual prompts were only required during the first session. Generalization data with her caregiver were 0 during pre-intervention but increased to mastery during post-intervention probes.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of Independently Completed Steps of the Shaving Task Analysis. Note. Open circles indicate generalization probes. X indicates outcome rating (right y-axis)

Similarly, during pre-intervention, Lydia correctly completed a mean of 9% of task analysis steps (range = 3%–13%), and her caregiver scored her shaving as a 1 (not well at all) on the ORA. During the intervention, she reached mastery within nine sessions, and her caregiver scored her shaving as 5 (very well). Manual prompts were required for a few steps during the first six sessions. Generalization data with her caregiver was 8% during pre-intervention, but increased to mastery during post-intervention probes.

Lorraine, during pre-intervention, completed a mean of 15% of task analysis steps (range = 8%–16%). During intervention, performance reached mastery criterion within six sessions. Generalization probes, the ORA, and the TARF-R were not completed for Lorraine because she lived independently. During post-intervention probes without the video prompts and tokens, all three participants continued to complete all steps of the task analysis independently for three consecutive sessions and performance was maintained at the 2-week maintenance probe.

Results of the social validity measures are as follows. Overall, caregivers reported favorably on all measures with a mean of 6.4 and range of 5.5–7 across questions. Of note, caregivers did not find the shaver to be too expensive (M = 1.0; 1 = not at all), and they identified that the participants did not experience discomfort during the procedures (M = 1.0; 1 = not at all). Additionally, when asked how likely the treatment was to make permanent improvements in the participant’s behavior, caregivers reported favorably (M = 6.0, range 5–7; 7 = very likely). Participants reported favorably, as well, stating they were happy with the outcome. Immediately upon completion of the study Lydia reported she wore a new dress to a party to show off her legs. Lorraine reported previously being scared to shave due to fear of cutting her legs but felt confident wearing skirts now. Allison expressed thanks because her mother previously prohibited leg shaving for fear of cutting herself, but she could now do it independently. She shared with us that she went to the beach immediately upon completion.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the effects of an intervention package, including POV VP, error correction, and reinforcement, on leg shaving with participants with a variety of disabilities. Participants learned to independently shave their legs within a mean of 7.3 sessions (range = 6–9 sessions) and maintained responding during maintenance probes. The quick acquisition of skills using VP with error correction demonstrated similar results to Gardner and Wolfe (2015). To our knowledge, this was the first empirical evaluation of procedures to teach leg shaving to individuals with disabilities.

The study also extended the research on whether a video fading procedure was required to minimize prompt dependency and promote independent acquisition. In this study, post-intervention probes were implemented to assess whether further teaching procedures would be needed following the removal of the intervention package. Each participant maintained mastery and did not require additional reinforcement thinning procedures to maintain independent responding. These findings are different from Sigafoos et al. (2007) that found the abrupt removal of the videos resulted in incorrect responding. Possible reasons for these differences may include that during the fading phase, there was no time limit, instruction, or steps to follow. Thus, the participants were able to complete the steps in any order and had the opportunity to go back over areas of their legs. This flexibility likely allowed for skill maintenance after the video prompts were removed. Additionally, systematic fading of the video prompts and thinning of reinforcement was potentially not needed because the behavior contacted the natural contingencies under which leg shaving should occur. That is, we taught shaving in the environment where each participant would shave and with the same materials they would use when independently shaving following intervention.

As noted, the current study used several components to promote leg shaving acquisition. Because this study was completed as part of the first author’s master’s thesis, we initially anticipated some participants with a variety of disabilities and potential barriers related to reinforcement; thus, we included a system that we could use consistently across all participants. Additionally, not only could a token system function as reinforcement, but also as marking to signal how many steps were completed and how many were left. Going forward, we recommend practitioners individualize the treatment package components to use whichever motivation system they already have or that would be effective with their clients. The token system may not be needed, as completion of each step in the task analysis should function as a reinforcer for the preceding step and a discriminative stimulus for the next step. Additionally, fading of the reinforcement system may be difficult. However, removing components of the intervention package was not a problem in the present study.

The current study also included an error correction procedure with repetitions of the video prompt and finally a manual prompt. Manual prompts were included because we replicated Gardner and Wolfe (2015). They were required for assistance completing some steps in the task analysis but were quickly faded. Replications of this intervention may omit this component of the error correction. If it is included, it is recommended manual prompts are minimized (e.g., fourth component of the error correction procedure).

When choosing when to conduct the sessions, it is important to consult with the clients and their families to identify timing of the sessions. We conducted sessions in the client’s preferred location and arranged the environment to promote privacy. However, when initially teaching the skill, we recommend frequent practice opportunities to ensure skill acquisition. A benefit of using the Finishing Touch Flawless Legs™ shaving device is that it will not cause the individual harm, even if there is little or no hair growth on the body part. Thus, practitioners may choose to first teach the skill and then identify conditions under which to teach the client to shave. Clients may prefer to shave weekly, regardless of environmental factors (e.g., they are not frequently wearing shorts because it is winter) or may choose to shave only when the hair is above ¼ in. long. Practitioners should balance practicing frequently and then identify when to teach clients to discriminate when it is time to shave their hair (e.g., skin feels rough or when they will wear shorts).

There are some limitations that practitioners may want to address in future replications. One recommendation is to add steps to the task analysis to clean the razor and to charge the razor in the task analysis. Additionally, to assess social validity of the procedures, we used an outcome rating assessment. In the current study, caregivers reported favorably on the outcomes of the intervention and found participants learned to independently shave their legs. We did not assess after each session as this was a secondary measure. We did not formally assess these measures with our participants but did ask their opinions throughout the study. A formal assessment could provide additional information to confirm participants are satisfied with the intervention. Practitioners and future researchers might more formally collect social validity data from the participants themselves. One way is to ask the participant to respond after each session, “How well do you feel you shaved your legs today?” or wait until a mastery criterion is met before asking.

This treatment package includes the possibility for generalization of the skill. If caregivers were taught to use video prompting, such as through behavior skills training, they could then implement the teaching procedures with their child. Additionally, these procedures could be used with individuals with higher support needs if they have an imitative repertoire, as we identified this as a prerequisite skill. If an individual does not have an imitative repertoire, this skill could potentially be taught with colored soap placed on their leg and then taught to shave until no color is left. Additionally, any other body part could be included using these procedures and new video prompts. Overall, these procedures can be adapted and implemented by practitioners in a variety of settings.

Authors' Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Information regarding software used in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Caldwell University Institutional Review Board and performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to Participate

Freely-given, informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Consent for Publication

Freely-given, informed consent to use data obtained during the study for publication purposes was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Charlop-Christy MH, Le L, Freeman KA. A comparison of video modeling with in vivo modeling for teaching children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(6):537–552. doi: 10.1023/a:1005635326276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon IG, Iwata BA. Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29(4):519–533. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner SJ, Wolfe PS. Teaching students with developmental disabilities daily living skills using point-of-view modeling plus video prompting with error correction. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2015;30(4):195–207. doi: 10.1177/1088357614547810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mays NM, Heflin LJ. Increasing independence in self-care tasks for children with autism using self-operated auditory prompts. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(4):1351–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers TM, Wacker DP. Parents' ratings of the acceptability of behavioral treatment recommendations made in an outpatient clinic: A preliminary analysis of the influence of treatment effectiveness. Behavioral Disorders. 1988;14(1):7–15. doi: 10.1177/019874298801400104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg NE, Schwartz IS, Davis CA. Evaluating the utility of commercial videotapes for teaching hand washing to children with autism. Education and Treatment of Children. 2010;33(3):443–455. doi: 10.1353/etc.0.0098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley-Benamou R, Lutzker BR, Taubman M. Teaching daily living skills to children with autism through instructional video modeling. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2002;4:166–177. doi: 10.1177/10983007020040030501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigafoos J, O'Reilly M, Cannella H, Edrisinha C, de la Cruz B, Upadhyaya M, Lancioni GE, Hundley A, Andrews A, Garver C, Young D. Evaluation of a video prompting and fading procedure for teaching dishwashing skills to adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2007;16(2):93–109. doi: 10.1007/s10864-006-9004-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veazey, S. E., Valentino, A. L., Low, A. I., McElroy, A. R., & LeBlanc, L. A. (2016). Teaching feminine hygiene skills to young females with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Behavior Analysis in Practice,9(2), 184–189. 10.1007/s40617-015-0065-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Williamson, H. (2015). Social pressures and health consequences associated with body hair removal. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing, 4, (3), 131–133. 10.12968/joan.2015.4.3.131

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Information regarding software used in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.