Abstract

How memory shapes animals' movement paths is a topic of growing interest in ecology, with connections to planning for conservation and climate change. Empirical studies suggest that memory has both temporal and spatial components, and can include both attractive and aversive elements. Here, we introduce reinforced diffusions (the continuous time counterpart of reinforced random walks) as a modelling framework for understanding the role that memory plays in determining animal movements. This framework includes reinforcement via functions of time before present and of distance away from a current location. Focusing on the interplay between memory and central place attraction (a component of home ranging behaviour), we explore patterns of space usage that result from the reinforced diffusion. Our efforts identify three qualitatively different behaviours: bounded wandering behaviour that does not collapse spatially, collapse to a very small area, and, most intriguingly, convergence to a cycle. Subsequent applications show how reinforced diffusion can create movement trajectories emulating the learning of movement routes by homing pigeons and consolidation of ant travel paths. The mathematically explicit manner with which assumptions about the structure of memory can be stated and subsequently explored provides linkages to biological concepts like an animal's ‘immediate surroundings' and memory decay.

Keywords: movement ecology, spatial memory, reinforced diffusion, reinforced random walk, time since last visit

1. Introduction

Understanding how memory influences animal movement has emerged as a major challenge in spatial ecology [1]. Memory, which facilitates movement decision-making based on non-contemporaneous information that may originate far beyond an animal's perceptual range, is advantageous in allowing consumers to match the location and timing of their resources [2,3]. For example, investigations of movement patterns by long-lived blue whales suggest that the whales eschew tracking of local gradients in resource distributions and instead navigate to areas where, over the long term, resources will be reliably available in abundance [4]. Avoidance of previously used areas is another way in which memory can shape movement [5,6]. For example, after making a kill in one area of the range, African lions tend to avoid those areas and hunt preferentially in different areas not recently exploited [5].

However, memory is actually quite difficult to study in field settings, and there have been only a few direct studies outside the laboratory. For example, studies of bird flight, in the context of both annual migration [7] and homing [8] have demonstrated how learning achieved via repeated experience with the same journeys can shape the paths flown. Working with roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), Ranc et al. [9] combined an experimental manipulation of food resources with an analysis of revisitation patterns to demonstrate that memory, rather than simply perception, governed movements of consumers seeking resources in a dynamic setting. Bracis & Mueller [3] came to similar conclusions for migrating zebras, finding that memory improved the migratory accuracy (with respect to seasonally available target regions) up to four times compared to migrants restricted to using perception. Effects due to memory of prior visits have also been included in so-called ‘step-selection functions', which are statistical analyses that seek to understand animals' preferences for space use by predicting future movement steps based on prior patterns of movement [10]. Efforts to understand animals' reuse of specific trackways in complex landscapes also highlight the importance of memory-based cognitive mechanisms for movement [11].

Given the difficulties inherent in developing empirical evidence for the importance of memory as a determinant of movement, theoretical studies remain an important approach for understanding how memory can shape movement paths and patterns of space use. Efforts to build memory into theoretical models of animal movement have taken diverse forms. Examples include individual-based models [12–17], multi-scaled random walks [18], partial differential equations [17,19] and stochastic models involving continuous time and continuous space (i.e. stochastic differential equations (SDEs)) [20,21]. Collectively, these models have highlighted how memory, particularly memory that operates on more than one temporal scale, can have a major influence on space use. Application scenarios for theoretical studies of memory-mediated movement include migration [3,12,21], foraging in heterogeneous landscapes [13,20] and the establishment of home ranges and spatial segregation [16,17,22].

Among the set of mathematical tools available for studying memory-based movement are reinforced random walks [23,24]. Reinforced random walks are stochastic processes in which ‘memory', or more specifically the effects of the random walker's pattern of revisitation and repetition, influences subsequent movements. In a general form, reinforced random walks can be used to represent situations where a random walker is either attracted to or repulsed by areas to which it has previously been [25,26]. The key point for reinforced random walks is that all or part of the history of a random walker's journey shapes the next step in the process (see also [10,22]). Applications of reinforced random walks are diverse. For example, in cancer biology, such processes have been studied in connection with tumour angiogenesis [27] and metastasis [28]. Reinforced random walks on graphs, in which the reinforcement from prior movements can happen at vertices or along the edges within the graph, are particularly useful in analyses of human and animal traffic patterns [29,30] and analyses of information networks [31].

In the applied mathematics literature, several authors have investigated reinforced random walks as representations of biological processes in which moving organisms leave behind a ‘trail' that can influence the movement of other organisms. For example, Sleeman & Levine [32] studied a model in which moving organisms leave behind a diffusible attractant that can spread away from the immediate location of deposition to influence the motion of animals elsewhere in the system. In related work, Stevens & Othmer [33] modelled the behaviour of myxobacteria that leave behind a slime trail as they move. Unlike attractants in most chemotaxis models, the slime is considered to be strictly local in nature and does not diffuse away from the position of deposition. Even without a diffusible attractant, the model of Stevens & Othmer [33] admits solutions in which the bacteria aggregate as a result of the increased ease of movement on the slime trails. Smouse et al. [26] suggested that reinforced random walks had promise as an approach for studying the movements of animals with memory. They specifically noted that reinforced random walks should be extended to allow for movement biases towards distant remembered locations (i.e. models should include memory-based movement relative to both prior space use and elapsed time).

The continuous time, continuous space counterparts to reinforced random walks are reinforced diffusions, a subject about which there remains much to learn mathematically [34]. Reinforced diffusions are written as SDEs, and in their simplest form, reinforced diffusions are Brownian motion with reinforcement. However, the reinforced diffusion approach allows for more complicated formulations as well, such as models featuring drift terms and weightings on the parameters of motion [34].

Here, we study reinforced diffusions with drift as theoretical models of animal movement. The primary advances of our models are that we include both reinforcement as a function of time and effects of distance, following the suggestions of Smouse et al. [26]. Reinforcement as a function of time allows for a continuous time mathematical representation of the ‘time since last visit' construct that has proven useful in prior studies of territoriality [6,35] and ‘cultivation grazing' [36]. We also include effects of distance to accommodate situations in which more distant locations are remembered with less (or more) fidelity than more proximate locations (e.g. [37]).

2. Methods

2.1. Model formulation

One of the simplest models for an animal's movement without memory is given by two-dimensional Brownian motion Wt, i.e. Xt = Wt, where Xt is the location of the animal at time t. The model can be expanded to include bias towards or away from certain spatial features via a generic SDE that includes a spatially dependent drift term:

| 2.1 |

where a is a diffusion coefficient (or matrix), b is the drift vector and x is a vector in . The drift term represents the spatial bias of the stochastic process either towards or away from features in its domain. In this formulation, the stochastic process is Markovian, and the history of how the stochastic process arrived at a present location does not influence the future motion.

To explore the effects of memory, we need to shift to a non-Markovian formulation. With memory, functions a and b expand to depend on time, and we have

| 2.2 |

where u is indexing elapsed time and the coefficients depend on the trajectory of the process up to time t. Note that a now depends on the current position of X, and also on all past points on the trajectory.

We can then expand the drift coefficient to have several components, allowing both the animal's movement history and elements of its landscape to shape future movements. For example, we can write

| 2.3 |

Here, the function represents the influence on the track at current time t by the past position at time t − s. The influence is quantified by the unit vector between Xt−s and Xt, which is scaled by two scalar functions T and U. Function T (positive or negative) quantifies the reinforcement provided by an element of an animal's historical path as a function of time, whereas function U quantifies the strength of the attraction/repulsion an animal experiences from its current position relative to a previously visited path element as a function of distance in space. The collective influence of all past path elements is quantified by integrating over these individual path elements. θ > 0 is the strength of the animal's attraction to the attractive location (e.g. a den or nest site), and V models the distribution of the animal's resources that depends on time and space (and to which the animal responds via gradient-following: is the gradient at point Xt and time t, i.e. the direction and intensity of the greatest local increase in the resource distribution V). The time-dependence function T may decay exponentially as a function of time or be considered equal to zero for all the values of the argument larger than a certain positive τ. These options correspond to the impact of the past track decaying to zero as it becomes more distant in time from the present, either in the limit as the difference goes to infinity, or at some finite time, respectively. The spatial dependence function U can take various forms, but a reasonable choice would be a non-negative function that decays to zero as the argument increases; this would correspond to past points on the track having less influence when they are more distant in space from the present location.

For the purposes of modelling or simulation, the integral in equation (2.3) can be approximated by its Riemann sum, and individual possible trajectories can be generated by numerically approximating the solution using Euler's method, with the addition of an appropriately scaled random vector at each step.

2.2. Scenario exploration

In our explorations of equation (2.3), we consider several different scenarios focusing on the interplay between memory and central place attraction, while noting the space usage that results from the reinforced diffusion. We pay particular attention to the effects of, and the interactions between, the time-dependent and spatially dependent components of memory. We save complications due to resource-driven movement for future work.

The distance weight function U is assumed to be positive, finite, non-strictly monotonically decreasing, with . The memory weight function T is likewise assumed to be finite and to go to zero, . Furthermore, the integral of these functions from 0 to positive infinity should be finite. These assumptions mean that points on the past track either very distant from the current point in space, or from very far in the past, have minimal influence on dXt.

If T is of bounded variation (any smooth bounded function with limit 0 at infinity which does not oscillate falls into this category), T can be decomposed into the difference of two positive finite decreasing monotonic functions:

| 2.4 |

The integral is split into two terms based on this linear combination:

| 2.5 |

This reformatting treats the effect of memory as two separate terms: one for short-term repulsion, and one for long-term attraction. This also allows the possibility, in future work, of investigating short- and long-term memory effects with completely different distance functions, with U replaced with Ulong and Ushort in the respective terms; for the present work, a common distance function U will be used.

We can reduce the number of parameters without restricting the allowable functions by vertically scaling the functions Tshort, Tlong and U by norming them to , respectively, and then combining the constants associated with each into two parameters scaling the respective short- and long-term memory integrals: α = Tlong(0)U(0), β = Tshort(0)U(0).

In summary, mlong, mshort, D all must have the following properties (where f(c) is a generic function standing in for any of them):

-

—

Z: the function takes positive values and gives an output between 0 and 1.

-

—

: the function has value 1 for input 0 (either 0 delay in the past for mlong, mshort, or 0 spatial distance for D), and goes to zero as distance in space or time becomes very large.

-

—

f decreases monotonically (non-strictly: it may be constant over some intervals): more distant points, in space or in time, have a weaker effect than closer ones.

Additionally, for mlong and mshort, but not necessarily for D, must be finite. This prevents the possibility of the memory vector becoming indefinitely large.

When we once again use f(c) as a generic function, the three function types that fit these first three properties (though not necessarily the finite integral condition) are the following.

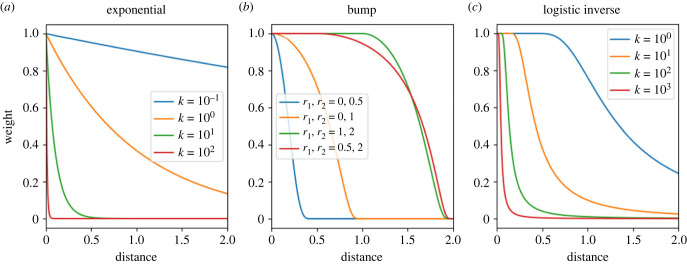

-

1.

Exponential decay (figure 1a). Takes a single parameter λ < 0 f(c) = eλc. For negative λ, the function decays to zero as u increases; the half-life H of the function is inversely proportional to λ, H = −ln(2)/λ. Exponential decay satisfies the finite integral condition.

-

2.

Bump (figure 1b). Takes two parameters, 0 ≤ r1 < r2 f(c) = 1 for c < r1

f(c) = 0 for c > r2.

Figure 1.

Candidate functions for the decay of memory. We interpret the distance over which the memory weight is approximately 1 as animals' ‘immediate surroundings' in which they have complete knowledge of the path traversed. Equations given in Methods.

If used for the distance function U, this would correspond to a memory effect that is constant over some neighbourhood in space, then gradually drops to zero at some distance from the current location, and is zero everywhere beyond a certain distance. Biologically, this might correspond to an animal's perceptual range: objects within a certain distance of the animal (such as landmarks remembered from a previous visit) have the same impact regardless of distance; objects at a greater distance are more difficult to distinguish and recognize, and have a lesser but still positive influence on the animal; and objects beyond the perceptual range entirely have no impact at all. The bump function satisfies the finite integral condition.

-

3.

Logistic inverse (figure 1c). Takes a single parameter k > 0

f(0) = 1

In the logistic inverse case, the parameter k determines how quickly memories decay as a function of time or space (i.e. k determines how intensely long-ago or far-away movements shape future movement). Moreover, the smaller the value of k the greater the time frame or the distance over which f(c) ≍ 1, meaning the greater the distance over which the animal has a complete memory of its movement, un-degraded by time or distance.

While this function may seem abstruse, it is in fact a composition of two common and relevant functions: the logistic function and the inverse square. Many phenomena in nature diminish in intensity approximately with the inverse square of the distance from their source. In the vicinity of the source of these stimuli, the stimulus is very high (in the theoretical case, where the source is treated analogously to a ‘point mass' in gravitational physics, the stimulus becomes infinitely intense as one approaches it). However, the animal responding to stimulus has some maximal response—its top speed. The logistic function takes the inverse square intensity of the stimulus as argument, and maps this value between 0 and 1. The logistic inverse function does not satisfy the finite integral condition, and therefore is only suitable for use as the distance function D.

Initially, we explored a broad variety of possible parameter combinations: a typical exploratory trial involved choosing a range of n values of some first parameter, a range of m values of some second parameter, and running the m × n possible parameter combinations for each of several possible function choices (e.g. bump, logistic inverse etc.). Two expected common system behaviours quickly emerged: either the system did not appear qualitatively different from similar systems without a long-term attractive component, or the trajectory nearly coalesced to a single point. Both of these behaviours will be discussed in greater depth later. These behaviours were easily foreseeable: if long-term memory is not strong enough, its effect is insubstantial; if it is very strong, it overwhelms all other effects and causes the trajectory to attract to itself and condense.

However, under certain parameter and function choices, a third behaviour emerged: the appearance of apparently stable and persistent reused tracks. In our preliminary explorations, this third behaviour did not occur when we used bump functions for either the spatial or temporal components of memory. When we did use bump functions, any effects of track reuse were either too weak (the trajectory would briefly reuse an earlier segment of its track, then lose it), or too strong (the trajectory would encounter an earlier segment of its track, follow it in a loop, and spiral inwards towards a single point). For this reason, we focused our efforts on models in which the temporal component of memory decayed exponentially (case 1 above) and in which the spatial component of memory follows the logistic inverse function (case 3 above). We refer to the distance over which f(c) ≍ 1 as the extent of the animal's ‘immediate surroundings' in which it has complete knowledge of its past movements (figure 1c).

For the home-ranging term θ(μ − X), we simply used θ(μ − X) = γ(μ − X), γ ≥ 0. θ then represents a vector from X towards μ, increasing linearly with the distance between the two points. If the overall equation were reduced to θ and the white noise term alone, this would describe an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process. For the functional term a modifying the white noise Wt, we used a constant multiplier a(u) = δ ≥ 0.

The overall function we investigated, then, has the form

| 2.6 |

This function has one initial condition, five parameters, plus three function types to choose, each of which has 1–2 additional parameters. When one further restricts X0 = μ = 0, restricts mshort and mlong to exponential decay functions, and restricts D to the logistic inverse function, the number of parameters is reduced to 7.

2.3. Computational modelling

We explored the effects of memory on movement in equation (2.6) computationally, noting emergent qualitative behaviours in the resulting movement tracks. We ran all the models with various parameter combinations for 200 time units, with 5000 (for figure 8) or 10 000 (for figures 2–7) steps per time unit as a numerical approximation of the continuous-time dynamics.

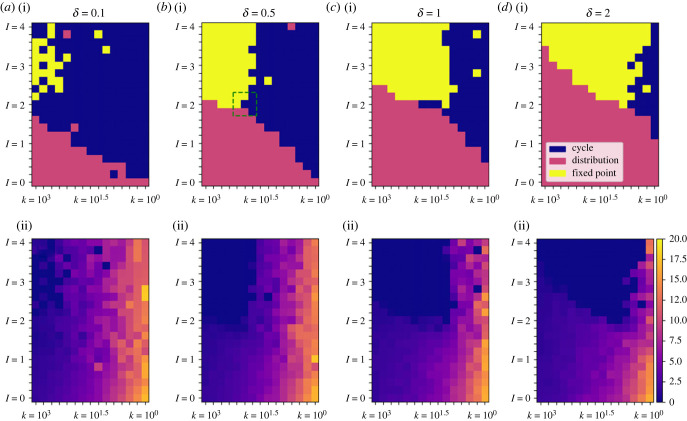

Figure 8.

Qualitative model output as a function of the relative intensities of the long- and short-term memories (I), the breadth of the distance function for memory (k) and the magnitude of white noise (δ). Each cell's information is derived from the results of a single trial under the given parameter conditions (315 parameter combinations in total). Row (i) shows the qualitative behaviours of the trajectories, corresponding to the movement track patterns illustrated in figures 2–6 and characterized in terms of the y-axis crossing values (plots i in figures 2–6). Row (ii) presents the standard deviation of the y-axis crossing values from the last 80 time units of each trial. Note that I > 1 corresponds to long-term attractive memory dominating whereas I < 1 corresponds to short-term aversive memory dominating. Note also that the k values decrease from left to right: this corresponds to an increase in the breadth of the distance function (i.e. an increase in the region a moving animal treats as its immediate surroundings; figure 1c). The colour bar and key are common to all panels in their respective rows. The dotted green square in (b(i)) indicates the 3 × 3 set of parameter conditions that was selected for additional trials to test whether different qualitative behaviours can form under the same parameter conditions (table 4 and figure 9 for results).

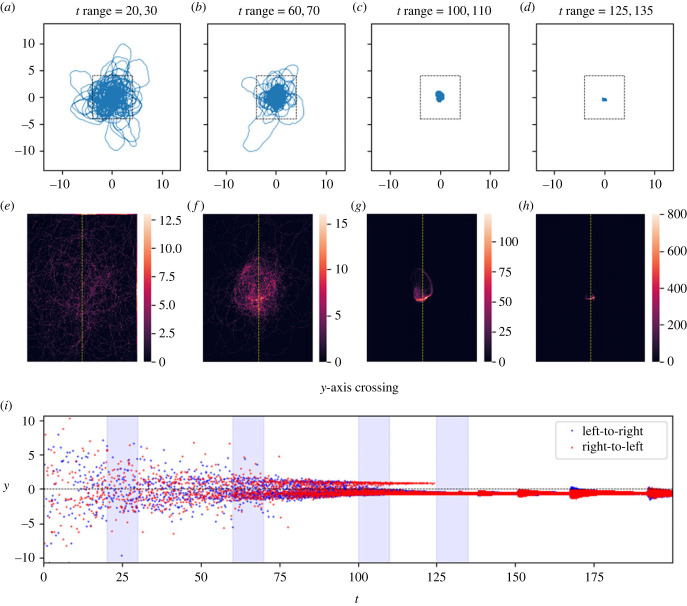

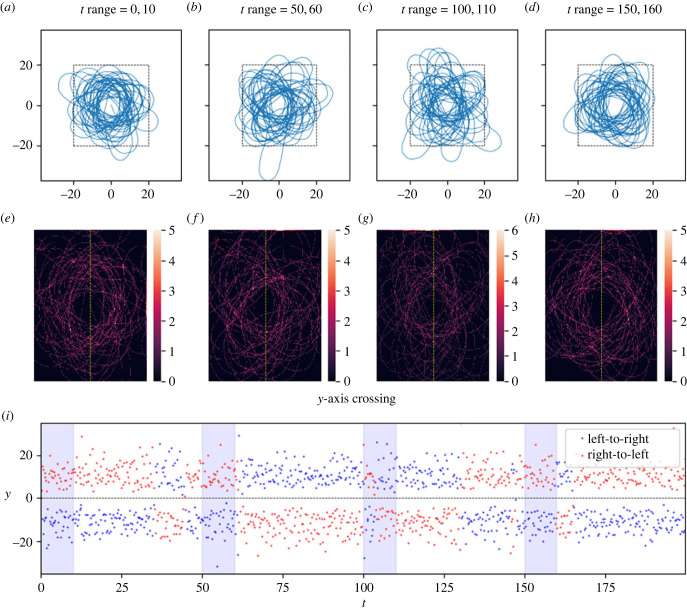

Figure 2.

In this figure, the track coalesces to a very tight distribution, which we call an ‘attractive point'. The track was allowed to evolve over 200 timesteps. Plots (a–d) show the track in various timeframes. Plots (e–h) are heatmaps showing the density of tracks by dividing a subset of x,y space (shown by black dashed lines in plots a–d) into cells and counting the number of tracks per cell. Each heatmap (e–h) corresponds to the time window of the plot (a–d) above it. Plot (i) shows the times and y values of the crossings of the y-axis (marked by the dashed yellow line on the heatmaps), with direction indicated by colour. The four time windows of plots (a–h) are shown in light blue. Parameters as in table 2. After t ≈ 135, the distribution appears to expand and contract several times: this is the result of numerical instability of the solver in the vicinity of the highly attractive point (the system becomes ‘stiff'), a common issue with forward ODE solvers. Link to animation: https://youtu.be/bAJU2k6dVcU.

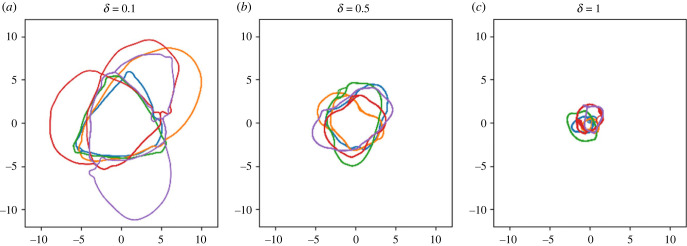

Figure 7.

Illustration of the diversity of possible cycles that can form under identical parameter conditions. In each plot, five trajectories are shown, each of which evolved under identical parameters, but with a unique random walk. Each plot has a different noise level (the parameter δ), whose impact on cycle size is clear. Parameters as in table 2.

This computational effort proved quite sufficient to characterize the qualitative behaviour of the models. However, because of the summative nature of the memory terms, model runs became very computationally demanding as the number of time units increased. This placed strong constraints on the number of parameter combinations that we could explore given our allotment on the University of Maryland's high performance computing system. Within the limits set by our allotment, we fixed the values of all but three parameters: noise level, the logistic inverse parameter k corresponding to the ‘broadness' of the distance function D, and the intensity of the long-term memory. Notably, we fixed the short-term memory function, mshort(s), to decay 100 times faster than the long-term memory function, mlong(s). The full set of fixed parameters is listed in table 1, and the varied parameter values are listed in tables 2 and 3 (for figures 2–7 and 8, respectively).

Table 1.

| parameter | interpretation | functions or values used |

|---|---|---|

| x0 | starting position | (0, 0) |

| μ | Ornstein–Uhlenbeck mean point | (0, 0) |

| mshort(s) | short-term memory function | exp(−10s), half-life = 0.0693 time units |

| mlong(s) | long-term memory function | exp(−0.1s), half-life = 6.93 time units |

| β | initial intensity of short-term memory | fixed at 50 000 |

| γ | intensity of central place attraction | fixed at 1 |

Table 2.

| figure | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qualitative behaviour | attractive point | cycle | cycle | distribution | distribution | cycles | |

| parameter | interpretation | values | |||||

| δ | magnitude of white noise | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | {0.1, 0.5, 1} |

| α | initial intensity of long-term memory | calculated from I for a fixed value of β | |||||

| I | relative intensity of short- and long-term memories | 2 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0 | 2 |

| k | logistic inverse function parameter (higher = narrower) | 100 | 25 | 10 | 25 | 5 | 25 |

| heatmap cell size | 0.0267 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.133 | n.a. | |

Table 3.

Parameters varied to make figure 8.

| parameter | interpretation | numerical values used |

|---|---|---|

| δ | magnitude of white noise | {0.1, 0.5, 1, 2} |

| α | initial intensity of long-term memory | calculated from I for a fixed value of β |

| I | relative intensity of short- and long-term memories | I = ((α/β)/100) (ratio of initial intensities over ratio of half-lives) |

| 21 different values, linearly spaced, from 0 to 4 | ||

| k | logistic inverse function parameter (higher = narrower) | 15 different values, logarithmically spaced from 1 to 1000 (figure 8) |

We chose to focus on the effect of parameters for which we had seen clear impacts on the qualitative behaviour of the system in our initial exploration of the parameter space and which were comparatively computationally inexpensive to test in hundreds of possible combinations. One notable omission is the exploration of the effect of the difference in time scales between short- and long-term memory. This is because long-term memory duration directly impacts computational time in a way that other parameter values do not, and systematically investigating this relationship would have been far more computationally expensive.

3. Results

We found that, on a qualitative level, the model admits at least three different long-run behaviours for the resulting movement tracks (figures 2–6). These are: (1) ‘distributions', in which the movement track wanders continually in some bounded region centred at the origin, (2) ‘attractive points', in which the movement track converges to a specific location and stays there (technically, these attractive points are not single points but rather very small regions of space because of the stochasticity inherent in the model, but there is nonetheless clear spatial convergence), and, perhaps most interesting, (3) ‘cycles' in which the movement track converges to a single path that is repeated continually. As a compact way of scoring model performance with respect to these qualitative behaviours, we recorded the time, location and direction of every transit of the movement track across the y-axis.

Figure 6.

Without long-term attraction to the past path, the trajectory again forms what we term a ‘distribution' (this is always the case when α = 0; figure 8). In this case, even without long-term attraction, the trajectory tends to orbit the origin: this is clear from the axis-crossing direction in plot (i). While this direction of rotation switches several times, the pattern of rotation is constant throughout. This rotation appears most clearly for ‘broad' distance functions (note in table 2 that k is lower for this figure than for figures 2–5). The function of long-term attraction, in these cases, is to take this existing rotational trend and condense it to a single reused closed path. Panels (a–i) as in figure 2. Parameters as in table 2.

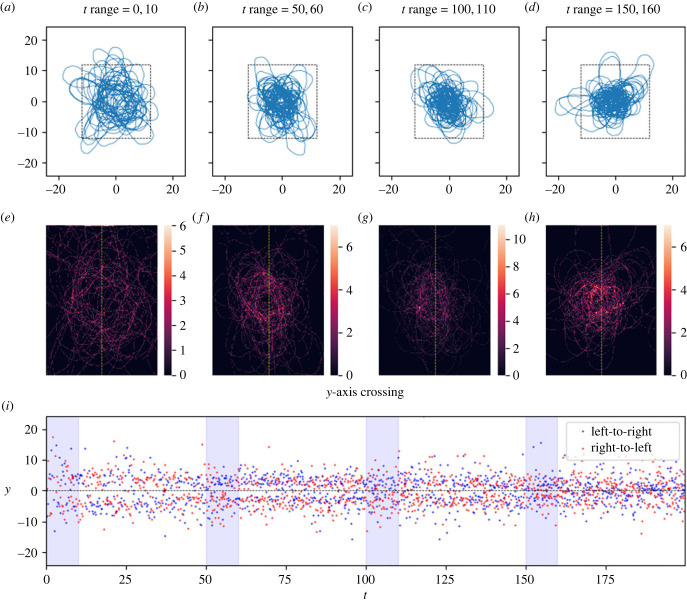

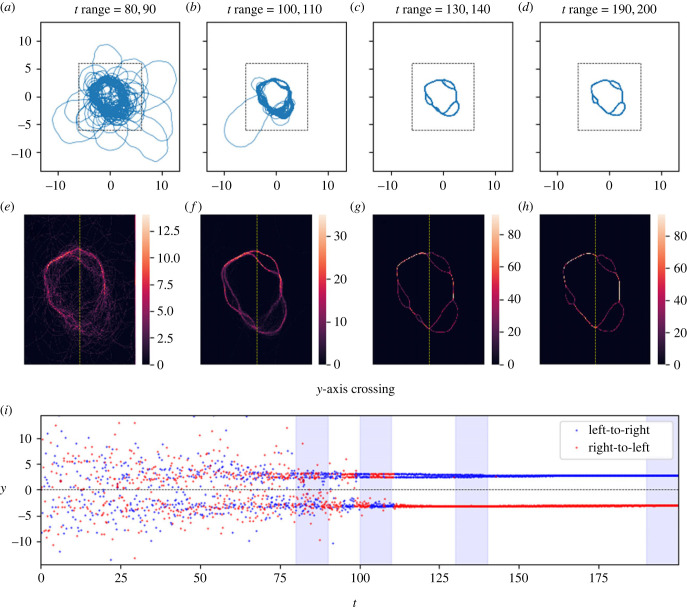

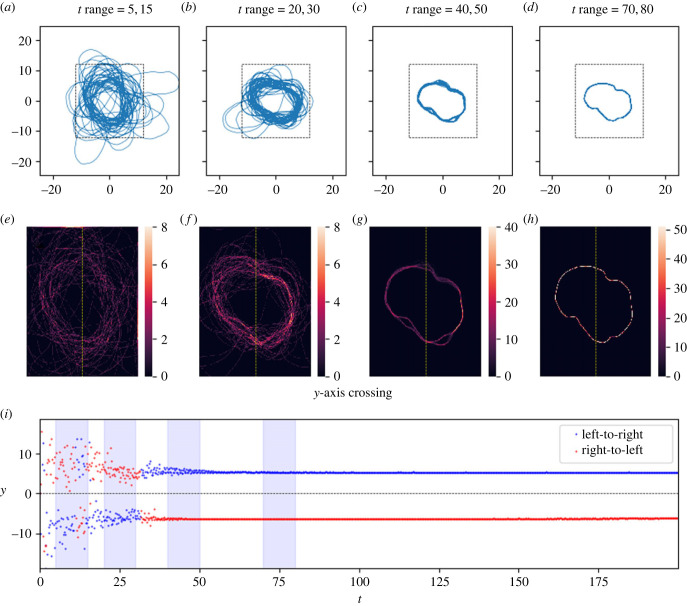

Figures 2–6 illustrate tracks that display these behaviours at four stages each of their evolution, as well as heat maps of track density and plots of y-axis crossings as a function of time. For distribution-type movement tracks, the y-axis crossings do not converge as t gets large (figures 5 and 6). While our analyses cannot rule out the possibility that distributions will ultimately converge to attractive points, we see no evidence of convergence over the time periods considered in tracks classified as distributions. By contrast, for attractive-point-type movement tracks, there is a clear convergence to a specific location as t gets large (subject to intrinsic small-scale stochasticity) (figure 2). Lastly, for cycle-type movement tracks, we observed clear convergence to a pattern in which the movement track crosses the y-axis in a leftward direction at one location, and then crosses in a rightward direction at a different location (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 5.

Here, the effect of the long-term memory draws the trajectory into a tighter distribution than it exhibits initially, but this distribution persists going forward and does not collapse to an attractive point. Panels (a–i) as in figure 2. Link to animation: https://youtu.be/fi93coWPgmY.

Figure 3.

Here, the track coalesces into a cycle about the origin. Panels (a–i) as in figure 2. At several points in space, the cycle separates from itself, then re-merges. However, these forking areas either shrink or disappear with time: between plots (c/d) and (g/h), the smallest fork (located at about 7 o'clock) disappears entirely, and the other three become shorter. Note that several times in plot (b), the track wanders off from the cycle for a time, then rejoins it. As can be seen in the plane-crossing plot (i), when the track rejoins the cycle, it sometimes starts moving along the cycle in the opposite direction. This implies that the long-term attraction of the path keeps the trajectory on the path, but does not dictate direction. Parameters as in table 2; the parameters here are the same as for figure 5, except that the long-term memory is 14% stronger in this case. This slight change produces this dramatically different behaviour. Link to animation: https://youtu.be/zIS2OJ-KjVw.

Figure 4.

As in figure 3, here the trajectory forms a cycle about the origin, though in this case this happens much more quickly. While initially the cycle contains several forks, all of these disappear. Parameters as in table 2; note that the only difference in parameters between the cycle here and the distribution in figure 5 is the broadness of the distance function: a broader distance function (corresponding to greater ‘immediate surroundings') produces a clear reused path where a narrower one produces a distribution of tracks over space. Panels (a–i) as in figure 2. Link to animation: https://youtu.be/y3at1lwaE24.

Initially, the networks of reused paths are more complicated than simple closed loops: the reused paths diverge and then recombine, like a river passing around islands. Given time, though, the distance between points of divergence and recombination shrinks (figure 3c,d/g,h), or one branch of the fork disappears altogether (figure 4c,d/g,h). While not every cycle was a simple closed loop by the end of the timeframe studied, most cycles were, and those that were not were clearly developing towards a closed loop. For a given set of parameters that yielded cycles, different cycles formed for each random walk, and different noise levels (δ) had strong impacts on cycle size (figure 7).

To transition from these case-wise illustrations to large-scale numerical work in which we sought to classify model behaviour over a large range of parameters, we adopted some simple rules for identifying each class of movement. To score the model behaviour for a particular parameter set as an attractive point, we required that the 20-time-unit sliding window of the standard deviation of the y-axis crossing points dropped below a threshold of 0.1. To score model behaviour as a cycle we required the ratio of the standard deviation of positive-valued y-axis crossings to the standard deviation of all y-axis crossings (again taken over a 20-time-unit sliding window) to fall below 0.1; this definition meant that the points above the x-axis would coalesce together, as would the points below the x-axis, but these two coalesced groups would stay separate. In some cases, we observed cycle-like behaviour that slowly decayed inward to an attractive point in a ‘death spiral' type manner as the locations of the leftward and rightward axis crossings slowly converged; we scored these cases as attractive points. Finally, we scored a parameter set as a distribution if neither of the above criteria was met. In some cases, the model would coalesce to an attractive point or a cycle that was off-centre from the origin. In such cases we replaced all references to crossings of the y-axis with crossings of a vertical line passing through the 20-time-unit moving average position of the track to ensure that the crossing plane passed through the trajectories, and therefore that plane crossings captured the dynamics. In practice, this moving average moved the crossing plane little, but allowed us to capture attractive points appearing slightly off-centre from the origin.

Figure 8 summarizes how these three classes of movement tracks depend on key parameters of the model, specifically on the ratio of the intensity of long-term memory relative to that of short-term memory (I in table 3), the breadth of the distance function for memory (determined by the parameter k in table 3), and the magnitude of the white noise term (δ).

The relative ‘intensity’ of the two memory functions is quantified by comparing their integrals. . If mlong, mshort are exponential functions, this simplifies to : if an exponential memory function has 100 times the initial intensity compared with another function, for example, but decays 100 times as quickly, they will be equally ‘intense'. For I < 1, attractive points are unstable: even if the track has spent its entire history at a single point, if it is perturbed slightly, the trajectory will move away from this point, because the short-term repulsion is more intense than the long-term attraction. Interestingly, in many areas of the parameter space where I > 1, attractive points do not form despite being stable if they were to form.

A clear inverse relationship exists between noise level and track formation: higher noise leads areas that once formed cycles to either (a) fail to form tracks or (b) collapse. In other words, a greater level of white noise constrains opportunities for the formation of cycles and increases opportunities for distribution- and attractive-point-type results. For a given level of noise, the breadth of the distance function for memory sets the opportunities for the formation of cycles. Depending on the noise level, ‘immediate surroundings' must be sufficiently large for cycles to form. By contrast, attractive points form when ‘immediate surroundings' are small and long-term memory is substantially more intense than short-term memory. Panels labelled ‘standard deviation' present the standard deviation of the y-axis crossing values (see plot i in figures 2–6) from the last 80 time units of each trial. In parameter regions corresponding to cycles, these standard deviation values closely positively correlate with the average diameter of the cycle formed.

The boundaries among the three qualitative classes of behaviour in figure 8 are a bit ragged, especially at low noise levels. We believe that this is due to the fact that multiple possible qualitative behaviours can coexist at the boundaries of the distinct regions of the parameter space; since each cell was the classification of a single trial under the parameter conditions, only one of three categorical options is displayed, rather than a distribution of possible outcomes for those parameters. In these cases, the particular underlying random walk of an individual trial determines whether the system becomes a fixed point, a distribution, or a cycle, with some probability assigned to each of those three possibilities.

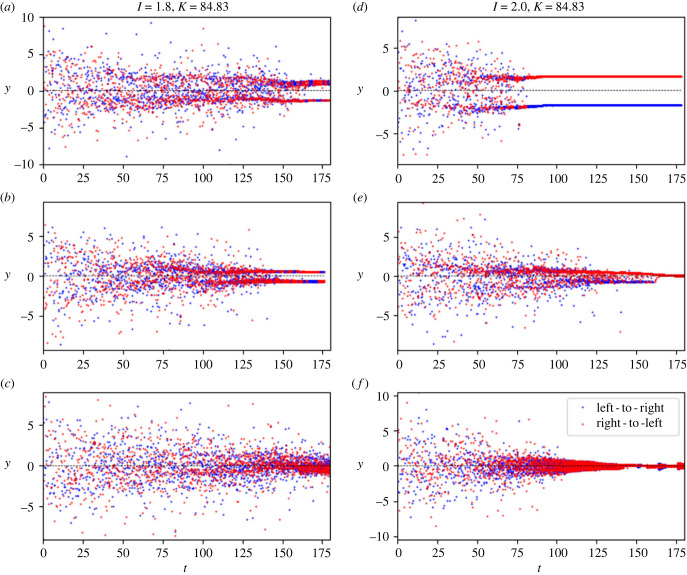

While we were not able to investigate this for the entire parameter space due to computational constraints, we did investigate the possibility of multiple behaviours in a subset of the parameter space near the triple point (the intersection of the three regions) in figure 8b–i. In this case, we observed qualitatively different behaviour occurring in simulations based on identical parameter conditions, but with unique random components. We selected a 3 × 3 grid of values of I and k, ran eight trials for each of the nine parameter combinations, and categorized them (this categorization, done by inspection, is shown in table 4). Several illustrative examples of qualitatively different patterns under the same parameter conditions are shown in figure 9.

Table 4.

Parameter combination for which eight trials each were carried out in the vicinity of (I, k) = (2.0, 84.83) corresponding to the triple point in figure 8, and the number of trials resulting in different qualitative behaviours.

| parameter combinations | no. of distributions | no. of cycles | no. of attractive points |

|---|---|---|---|

Figure 9.

Each panel is a plane-crossing diagram of the same type as panel (i) in figures 2–6. Within the groups (a–c) and (d–f) all simulations use identical parameters (parameters as figure 8b, with I and k given here). However, in each of these groups, different trials with different random components produce qualitatively different results. Groups (a) and (b) form cycles (as indicated by the pair of groups of plane crossings), while (c) does not. Group (e) forms a cycle that collapses to a fixed point; (f) directly collapses to a fixed point without forming a cycle first; and (c) forms a cycle that remains stable. Table 4 shows the count of behaviour classifications (out of eight trials per parameter combination) for a region of the parameter space (indicated with a green square in figure 8b(i)) based on results like those shown here.

This origin-circling trend appears with or without long-term memory. In cases where long-term memory is absent, noise is low, and the immediate surroundings are broad, this origin-circling behaviour is quite clear (figure 6): the long-term attraction to the past track, then, takes this general trend in the motion and condenses it into a single reused path. Notably, while this reused path clearly derives from the underlying (non-long-term-memory-driven) trend, it is not a mere averaging of this trend: rather than being a perfect circle, particular features of the random walk are recorded in the reused path and persist through the timeframe (see figure 7 for examples of different tracks forming under identical parameters).

Further examples of long-term memory condensing diffuse trends into single reused paths can be seen in the examples in electronic supplementary material, A, which examine, in less detail than the preceding, animals using reinforced diffusion to move between discrete points. These studies are motivated by empirical examples in which homing pigeons (Columba livia) learn their routes and in which Argentine ants (Linepithima humile) move between focal areas.

For mathematically inclined readers, some detailed notes supporting the existence of non-degenerate recurrent solutions in reinforced diffusion models (such as the cycles mentioned above) appear as electronic supplementary material, B.

4. Discussion

We have introduced reinforced diffusion as a model of animal movement with both short- and long-term memory. Our efforts have identified, and characterized the parametric dependence of, three qualitative behaviours: wandering behaviour that is bounded but does not collapse spatially, collapse to a very small area, and convergence to a cycle. In other words, different parameter values produce qualitatively different invariant sets, which are, very nearly, zero-, one- or two-dimensional (attractive points, cycles, and distributions, respectively). Conditions separating these three behaviours hinge on the relative intensity of long-term versus short-term memory, how memory decays as a function of distance between current locations and previously visited locations, and the amount of stochastic noise inherent in the movement process (figure 8).

The phenomenon of cycle formation, as we describe it here, bears similarity to both patrolling of territorial boundaries by wolves [6] and the formation of route-following by homing pigeons following displacement [8,38]. In homing pigeons, route consolidation with increasing number of flights flown appears to be visually driven and involve fixed waypoints, leading to flight paths that are followed consistently, even if they are not the most efficient routes. We see route consolidation in our models as an animal's patch coalesces over time onto a repeated cycle. Except for the existence of a single attractive point in the central place attraction component of our models, space itself is homogeneous and free of any cues for movement, so the route consolidation leading to cycles derives solely from the animal's memory of previous tracks followed. A simple adaptation of the model in equation (2.6), which successfully produced the pigeon-like behaviour of reused, convergent tracks while homing, is discussed in electronic supplementary material, A.

As with repeated use of homing paths, memory-based movement should (given sufficiently strong attractive pressures and sufficiently weak aversive pressures) lead to the establishment of well-used trackways as trips through a habitat create a reinforcement effect that carries forward to favour re-use of the same routes. Evidence for repeated use of favoured routes has recently been documented in several Neotropical mammals, though the intensity and spatial scale of the track repetition varied among species [11]. In some observed cases, these favoured routes are not necessarily the most direct path between destinations, but are instead either reinforcement of an essentially random aspect of the first path taken through the landscape [8] (see also electronic supplementary material, A), or the persistent impact of aspects of the landscape which are no longer present [39]. In patchy landscapes, such preferences for re-use of previously used navigational routes could have a strong effect of patterns of connectivity. This is especially relevant in cases where animals cross highways in particular areas, leading to opportunities and challenges for road-crossing structures (e.g. overpasses, underpasses) that reduce wildlife–vehicle collisions [40]: loyalty to existing paths could potentially make wildlife less likely to use seemingly well-placed structures that do not take extant movement patterns into account.

Another link to empirical movement patterns may also exist with regard to the role of aversive and attractive memory in our model of reinforced diffusion. In models of collective motion, sociality can structure movement as individuals attempt to maintain their position relative to the positions of other animals via the interplay of aversive and attractive forces that operate on different spatial scales (e.g. [41]). Similar effects seem at work here as an individual's aversion and attraction to elements of its remembered pathway shape subsequent movements. Solving reinforced diffusion models becomes computationally challenging because of the compounding nature of the time integrals in equation (2.6) as time increases. Constraints on our use of the University of Maryland's high performance cluster restricted the scope of our investigations here. However, what we have done has suggested several opportunities for future work. One area of future work should explore the structure of the home-ranging term (equations (2.3), (2.6)), which has its roots in Ornstein–Uhlenbeck motion [42]. For example, is the home-ranging term essential to the qualitative behaviours observed, or is it possible to achieve cycles just using memory alone? We believe the term is required, but full understanding requires more investigation. Likewise, are different or additional behaviours possible if the home-ranging term has more than one attractive centre?

Another topic ripe for further development is to posit that the mobile animals are consumers and then incorporate a resource distribution and gradient following. There is tremendous interest in the role that resource memory plays in consumer movement. This includes theoretically oriented research [12,13,19–21,37], analyses of empirical movement data both with and without comparative models [4–6], and experimental manipulations of resource distribution [9,43]. Although we have not explored the influences of resources on movement here, we did include such a possibility in the full drift term in equation (2.3), suggesting opportunities for further theoretical investigation.

We also see opportunities for continued exploration of functions like the inverse logistic model (used here to represent the spatial component of memory) as a platform for investigating the interplay between perception and memory. We refer to the distance over which the function U() = 1 before declining towards 0 as the animal's ‘immediate surroundings'. This means that all portions of the animal's track that fall within this distance of the animal's current location are remembered perfectly and have the potential to fully influence subsequent movement, tempered only by memory decay associated with the passage of time as represented by the function T(). At a conceptual level, we link these ‘immediate surroundings' with the animal's perceptual range, which, in the empirical literature, is defined as the maximum distance at which landscape features can be identified (e.g. [44,45]). Perceptual ranges may influence movement through acquisition of non-local information about resources or habitats and may vary across species and spatial contexts [44,46,47]. Theoretical studies have examined the utility of perception for acquiring resources in a dynamic landscape [48] and for mate finding [49,50]. Other work has explored perceptual range as an evolvable trait [51]. Future studies of reinforced diffusion should examine the benefits (or potential costs; see [48]) of memory functions featuring spatially extended ‘immediate surroundings' in models with resources. Such studies could shed insight on results like those of Bracis & Mueller [3], which found that memory, not just perception, was essential to the navigational success of migrating zebras.

A final area of future work should attend to further explorations of the temporal and spatial decay functions T() and U() in equation (2.5), respectively. For example, if instead of an exponential function, the temporal decay of memory followed a bump function (in which there was complete knowledge of behaviour out to some previous time, rather than initiating the decay process immediately), how would that interact with the logistic inverse function for the spatial component of memory already in place?

An altogether different approach would be to link memory to the noise term instead of the drift functionals. The basic idea here is that increasing memory could reduce diffusivity and make the path more deterministic towards a nest site, a high-quality region, etc. In practice, a noise term that decreases with increasing memory would lead to a decreased tendency to wander (or explore new areas). Empirical work on juvenile whooping cranes (Grus americana) demonstrates such an effect in that juvenile cranes flying in the absence of older, more experienced individuals tend to wander during migration, whereas similarly aged birds flying with more experienced birds (which are inferred to have better memory by virtue of having repeated the migratory journey several times) exhibit more linear migrations, with substantially reduced wandering [7].

At present, we view reinforced diffusion models as tools for theoretical studies. However, additional work beyond the introductory treatment we present here may afford opportunities to link models of this type to empirical animal movement data. For example, one way to link reinforced diffusion models to empirical data might be through the behavioural concept of ‘landmarks', such as are hypothesized to operate in homing pigeons' movement via visual pilotage [8]. Explorations of such ideas could proceed mathematically by modifying the memory functional so that it was discontinuous with non-zero values only in some vicinity of each landmark. Another option would be to integrate reinforced diffusion models with parameter estimation approaches recently developed to gauge the importance of memory in a ‘time since last visit’ framework (see [52] for a case study involving seasonal movement of grizzly bears). Movement data are typically collected in discrete intervals (e.g. as GPS ‘fixes'), but methods exist for interpolating such discrete data into continuous paths relevant to the reinforced diffusion framework (e.g. [53]). Empirical movement data from animal reintroduction efforts [54–56] may be especially useful in teasing out memory-related effects (e.g. [22]).

We have introduced reinforced diffusions as a platform for modelling the role of memory in animal movement. Advantages of this approach include the explicit manner with which assumptions about the structure of memory can be stated and subsequently explored; this provides an opportunity to link biological concepts like an animal's ‘immediate surroundings' and memory decay explicitly to mathematical representations. Computational cost is a concern as the integrals that summarize memory (equation (2.6)) take longer to solve as the duration of memory increases. Intriguingly, our explorations have revealed three qualitatively different classes of movement behaviour (attractive points, cycles, and distributions), which are determined parametrically and interpretable biologically. We see opportunities for using this kind of modelling to address certain questions regarding the role of memory in animal movement and suggest several directions for further work.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants at the 2022 Workshop on Spatial Ecology in Sheffield, UK, for helpful suggestions. Steve Cantrell, Chris Cosner, Ricardo Martínez-García and Chris Fleming provided additional helpful comments on the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the University of Maryland supercomputing resources (http://hpcc.umd.edu) made available for conducting the research reported in this paper.

Data accessibility

Code for producing these results is available at https://github.com/fmcbride/trailblazer/.

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [57].

Authors' contributions

W.F.F.: conceptualization, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, writing—original draft; F.M.: software, visualization, writing—review and editing; L.K.: investigation, methodology, software, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by NSF award DMS1853465.

References

- 1.Fagan WF, et al. 2013. Spatial memory and animal movement. Ecol. Lett. 16, 1316-1329. ( 10.1111/ele.12165) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller T, Fagan WF. 2008. Search and navigation in dynamic environments—from individual behaviors to population distributions. Oikos 117, 654-664. ( 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16291.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bracis C, Mueller T. 2017. Memory, not just perception, plays an important role in terrestrial mammalian migration. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170449. ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.0449) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrahms B, Hazen EL, Aikens EO. 2019. Memory and resource tracking drive blue whale migration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5582-5587. ( 10.1073/pnas.1819031116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valeix M, Chamaillé-Jammes S, Loveridge AJ, Davidson Z, Hunt JE, Madzikanda H, Macdonald DW. 2011. Understanding patch departure rules for large carnivores: lion movements support a patch-disturbance hypothesis. Am. Nat. 178, 269-275. ( 10.1086/660824) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlägel UE, Merrill EH, Lewis MA. 2017. Territory surveillance and prey management: wolves keep track of space and time. Ecol. Evol. 7, 8388-8405. ( 10.1002/ece3.3176) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller T, O'Hara R, Urbanek R, Converse S, Fagan WF. 2013. Social learning of migratory performance. Science 341, 999-1002. ( 10.1126/science.1237139) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biro D, Meade J, Guilford T. 2004. Familiar route loyalty implies visual pilotage in the homing pigeon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 17 440-17 443. ( 10.1073/pnas.0406984101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranc N, Moorcroft PR, Ossi F, Cagnacci F. 2021. Experimental evidence of memory-based foraging decisions in a large wild mammal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2014856118. ( 10.1073/pnas.2014856118) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira-Santos LGR, Forester JD, Piovezan U, Tomas WM, Fernandez FA. 2016. Incorporating animal spatial memory in step selection functions. J. Anim. Ecol. 85, 516-524. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12485) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alavi SE, Vining AQ, Caillaud D, Hirsch BT, Havmøller RW, Havmøller LW, Kays R, Crofoot MC. 2022. A quantitative framework for identifying patterns of route-use in animal movement data. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 743014. ( 10.3389/fevo.2021.743014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett DA, Tang W. 2006. Modelling adaptive, spatially aware, and mobile agents: elk migration in Yellowstone. Int. J. Geographical Info. Sci. 20, 1039-1066. ( 10.1080/13658810600830806) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller T, Fagan WF, Grimm V. 2011. Integrating individual search and navigation behaviors in mechanistic movement models. Theor. Ecol. 4, 341-355. ( 10.1007/s12080-010-0081-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avgar T, Deardon R, Fryxell JM. 2013. An empirically parameterized individual based model of animal movement, perception, and memory. Ecol. Model. 251, 158-172. ( 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.12.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fronhofer EA, Hovestadt T, Poethke H-J. 2013. From random walks to informed movement. Oikos 122, 857-866. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.21021.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riotte-Lambert L, Benhamou S, Chamaillé-Jammes S. 2015. How memory-based movement leads to nonterritorial spatial segregation. Am. Nat. 185, E103-E116. ( 10.1086/680009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potts JR, Lewis MA. 2016. How memory of direct animal interactions can lead to territorial pattern formation. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20160059. ( 10.1098/rsif.2016.0059) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautestad AO. 2011. Memory matters: influence from a cognitive map on animal space use. J. Theor. Biol. 287, 26-36. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.07.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurarie E, Potluri S, Cosner GC, Cantrell RS, Fagan WF. 2022. Memories of migrations past: sociality and cognition in dynamic, seasonal environments. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 647. ( 10.3389/fevo.2021.742920) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bracis C, Gurarie E, Van Moorter B, Goodwin RA. 2015. Memory effects on movement behavior in animal foraging. PLoS ONE 10, e0136057. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0136057) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin HY, Fagan WF, Jabin PE. 2021. Memory-driven movement model for periodic migrations. J. Theor. Biol. 508, 110486. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110486) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranc N, Cagnacci F, Moorcroft PR. 2022. Memory drives the formation of animal home ranges: evidence from a reintroduction. Ecol. Lett. 25, 716-728. ( 10.1111/ele.13869) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis B. 1990. Reinforced random walk. Prob. Theory Relat. Fields 84, 203-229. ( 10.1007/BF01197845) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Q, Johansson A, Tero A, Nakagaki T, Sumpter DJ. 2013. Current-reinforced random walks for constructing transport networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20120864. ( 10.1098/rsif.2012.0864) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Codling EA, Plank MJ, Benhamou S. 2008. Random walk models in biology. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, 813-834. ( 10.1098/rsif.2008.0014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smouse PE, Focardi S, Moorcroft PR, Kie JG, Forester JD, Morales JM. 2010. Stochastic modelling of animal movement. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 2201-2211. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plank MJ, Sleeman BD. 2003. A reinforced random walk model of tumour angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic strategies. Math. Med. Biol. 20, 135-181. ( 10.1093/imammb/20.2.135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson ARA, Chaplain MAJ, Newman EL, Steele RJC, Thompson AM. 2000. Mathematical modelling of tumour invasion and metastasis. J. Theor. Med. 2, 129-154. ( 10.1080/10273660008833042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perna A, Latty T. 2014. Animal transportation networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140334. ( 10.1098/rsif.2014.0334) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benson AR, Gleich DF, Lim LH. 2017. The spacey random walk: a stochastic process for higher-order data. SIAM Rev. 59, 321-345. ( 10.1137/16M1074023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mei Q, Guo J, Radev D. 2010. DivRank: the interplay of prestige and diversity in information networks. In Proc. 16th ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 July 2010, pp. 1009-1018. New York, NY: ACM. ( 10.1145/1835804.1835931) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sleeman BD, Levine HA. 1997. A system of reaction diffusion equations arising in the theory of reinforced random walks. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 57, 683-730. ( 10.1137/S0036139995291106) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Othmer HG, Stevens A. 1997. Aggregation, blowup, and collapse: the ABC's of taxis in reinforced random walks. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 57, 1044-1081. ( 10.1137/S0036139995288976) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pemantle R. 2007. A survey of random processes with reinforcement. Probab. Surv. 4, 1-79. ( 10.1214/07-PS094) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlägel UE, Lewis MA. 2014. Detecting effects of spatial memory and dynamic information on animal movement decisions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 1236-1246. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12284) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Preen A. 1995. Impacts of dugong foraging on seagrass habitats: observational and experimental evidence for cultivation grazing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 124, 201-213. ( 10.3354/meps124201) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Moorter B, Visscher D, Benhamou S, Börger L, Boyce MS, Gaillard JM. 2009. Memory keeps you at home: a mechanistic model for home range emergence. Oikos 118, 641-652. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17003.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meade J, Biro D, Guilford T. 2005. Homing pigeons develop local route stereotypy. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 17-23. ( 10.1098/rspb.2004.2873) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dupuis-Desormeaux M, Kaaria TN, Mwololo M, Davidson Z, MacDonald SE. 2018. A ghost fence-gap: surprising wildlife usage of an obsolete fence crossing. PeerJ 6, e5950. ( 10.7717/peerj.5950) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denneboom D, Bar-Massada A, Shwartz A. 2021. Factors affecting usage of crossing structures by wildlife—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 777, 146061. ( 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146061) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katz Y, Tunstrøm K, Ioannou CC, Huepe C, Couzin ID. 2011. Inferring the structure and dynamics of interactions in schooling fish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18 720-18 725. ( 10.1073/pnas.1107583108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uhlenbeck GE, Ornstein LS. 1930. On the theory of Brownian motion. Biophys. Rev. 36, 823-841. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall RE, Hurly TA, Sturgeon J, Shuker DM, Healy SD. 2013. What, where and when: deconstructing memory. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20132194. ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.2194) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zollner PA, Lima SL. 1997. Landscape-level perceptual abilities in white-footed mice: perceptual range and the detection of forested habitat. Oikos 80, 51-60. ( 10.2307/3546515) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mech SG, Zollner PA. 2002. Using body size to predict perceptual range. Oikos 98, 47-52. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2002.980105.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forero-Medina G, Vieira MV. 2009. Perception of a fragmented landscape by neotropical marsupials: effects of body mass and environmental variables. J. Trop. Ecol. 25, 53-62. ( 10.1017/S0266467408005543) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prevedello JA, Forero-Medina G, Vieira MV. 2011. Does land use affect perceptual range? Evidence from two marsupials of the Atlantic Forest. J. Zool. 284, 53-59. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00783.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fagan WF, Gurarie E, Bewick S, Howard A, Cantrell RS, Cosner C. 2017. Perceptual ranges, information gathering, and foraging success in dynamic landscapes. Am. Nat. 189, 474-489. ( 10.1086/691099) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laidre KL, Born EW, Gurarie E, Wiig Ø, Dietz R, Stern H. 2013. Females roam while males patrol: divergence in breeding season movements of pack-ice polar bears (Ursus maritimus). Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20122371. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.2371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinez-Garcia R, Fleming CH, Seppelt R, Fagan WF, Calabrese JM. 2020. How range residency and long-range perception change encounter rates. J. Theor. Biol. 498, 110267. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110267) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swain A, Hoffman T, Leyba K, Fagan WF. 2021. Exploring the evolution of perception: an agent-based approach. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 698041. ( 10.3389/fevo.2021.698041) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson PR, Lewis MA, Edwards MA, Derocher AE. 2022. Time-dependent memory and individual variation in Arctic brown bears (Ursus arctos). Mov. Ecol. 10, 18. ( 10.1186/s40462-022-00319-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fleming CH, Fagan WF, Mueller T, Olson KA, Leimgruber P, Calabrese JM. 2016. Estimating where and how animals travel: an optimal framework for path reconstruction from autocorrelated tracking data. Ecology 97, 576-582. ( 10.1890/15-1607.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berger-Tal O, Saltz D. 2014. Using the movement patterns of reintroduced animals to improve reintroduction success. Curr. Zool. 60, 515-526. ( 10.1093/czoolo/60.4.515) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He K, et al. 2019. Movement and activity of reintroduced giant pandas. Ursus 29, 163-174. ( 10.2192/URSUS-D-17-00030.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mertes K, Stabach JA, Songer M, Wacher T, Newby J, Chuven J, Al Dhaheri S, Leimgruber P, Monfort S. 2019. Management background and release conditions structure post-release movements in reintroduced ungulates. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7, 470. ( 10.3389/fevo.2019.00470) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fagan WF, McBride F, Koralov L. 2023. Reinforced diffusions as models of memory-mediated animal movement. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6472264) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Code for producing these results is available at https://github.com/fmcbride/trailblazer/.

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [57].