Abstract

This study uses data from the 2003-2004 to 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) to assess whether a difference exists in dietary vitamin A intake as a marker of consumption of vitamin A–rich foods among Black, Hispanic, and White adults in the US.

Vitamin A, including retinol and provitamin A carotenoids, regulates cell growth and differentiation. Low vitamin A intake is associated with increased risk of chronic diseases and mortality.1 Research suggests a lower vitamin A status among Black and Hispanic individuals than White individuals.2 We investigated whether a difference exists in dietary vitamin A intake as a marker of consumption of vitamin A–rich foods (ie, fruits, leafy green vegetables, fish, and dairy) among Black, Hispanic, and White adults in the US.

Methods

This study used continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cycles from 2003-2004 (response rate, 79%) to 2017-2018 (response rate, 52%). NHANES is nationally representative, assesses the health and nutritional status of noninstitutionalized adults and children in the US, and includes interviews and physical examinations. Race and ethnicity were self-reported, mutually exclusive categories: non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic (including Mexican American and other Hispanic ethnicities), or non-Hispanic White. Other races were not included because of small numbers and no Asian category until 2011. Adults aged 20 years or older were eligible. Levels of vitamin A were determined by food intake in the last 24 hours obtained through in-person interviews at mobile examination centers (day 1). Gamma generalized linear regression models were used to estimate mean vitamin A intake differences between Black and Hispanic participants vs White participants with adjustment for confounders and using weighted data (eAppendix in Supplement 1). Vitamin A and beta carotene supplements were not included because they are not part of a usual diet. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and Stata version 17 (StataCorp); statistical significance was defined by a 2-sided α = .05. The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board deemed this study to be exempt from review. NHANES participants provided written informed consent.

Results

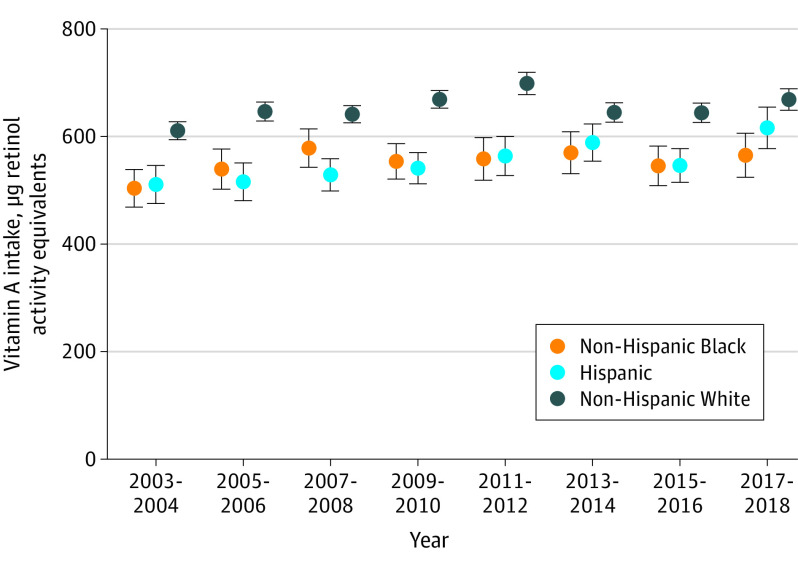

Among 35 929 eligible participants with dietary vitamin A levels, 8524 (23.7%) were Black (52.1% female; mean age, 48.6 [SD, 17.2] years), 9895 (27.5%) were Hispanic (52.9% female; mean age, 47.0 [SD, 16.8] years), and 17 510 (48.7%) were White (50.6% female; mean age, 52.5 [SD, 19.0] years) (Table). The percentage of missing covariates ranged from 1% to 2.1%. The overall trend in dietary vitamin A intake was stable for Black participants (P = .16 for trend) and for White participants (P = .22 for trend) but increasing for Hispanic participants (P = .005 for trend) (Figure). In the 2003-2004 cycle, compared with White adults (mean vitamin A intake, 610.5 μg retinol activity equivalents [RAEs]), levels were significantly lower among Black adults (503.0 μg RAEs; difference, 108.8 [95% CI, 64.3-153.2] μg RAEs; P < .001) and Hispanic adults (509.6 μg RAEs; difference, 102.1 [95% CI, 55.5-148.6] μg RAEs; P < .001). In the 2017-2018 cycle, compared with White adults (668.6 μg RAEs), levels remained significantly lower for Black adults (563.8 μg RAEs; difference, 104.6 [95% CI, 51.3-157.8] μg RAEs; P < .001) and lower but not significant for Hispanic adults (615.1 μg RAEs; difference, 53.3 [95% CI, −3.3 to 110.0] μg RAEs; P = .07).

Table. Participant Sociodemographic Characteristics in Continuous NHANES Cycles: Overall, 2003-2004, 2009-2010, and 2017-2018a.

| Characteristics | NHANES cycle, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2003-2004 | 2009-2010 | 2017-2018 | |

| Total | 35 929 (100) | 4316 (100) | 5458 (100) | 3880 (100) |

| Race and ethnicityb | ||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 8524 (23.7) | 880 (20.4) | 1025 (18.8) | 1128 (29.1) |

| Hispanic | 9895 (27.5) | 1016 (23.5) | 1647 (30.2) | 1058 (27.3) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 17 510 (48.7) | 2420 (56.1) | 2786 (51.0) | 1694 (43.6) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 18 536 (51.6) | 2246 (52.0) | 2811 (51.5) | 1996 (51.4) |

| Male | 17 393 (48.4) | 2070 (48.0) | 2647 (48.5) | 1884 (48.6) |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 20-39 | 11 954 (33.3) | 1471 (34.1) | 1794 (32.9) | 1141 (29.4) |

| 40-59 | 11 387 (31.7) | 1221 (28.3) | 1833 (33.6) | 1166 (30.1) |

| ≥60 | 12 588 (35.0) | 1624 (37.6) | 1831 (33.5) | 1573 (40.5) |

| Educational levelc | ||||

| Less than grade 9 | 4061 (11.3) | 616 (14.3) | 676 (12.4) | 325 (8.4) |

| Grade 9-11 | 5403 (15.1) | 650 (15.1) | 898 (16.5) | 460 (11.9) |

| High school graduate or GED | 8675 (24.2) | 1088 (25.2) | 1271 (23.3) | 1013 (26.2) |

| Some college or advanced degree | 10 651 (29.6) | 1173 (27.2) | 1542 (28.3) | 1346 (34.7) |

| College graduate or higher | 7102 (19.8) | 783 (18.2) | 1060 (19.5) | 730 (18.8) |

| Marital statusc | ||||

| Married | 21 203 (59.0) | 2594 (60.1) | 3237 (59.3) | 2199 (56.7) |

| Divorced, widowed, or separated | 8360 (23.3) | 1022 (23.7) | 1275 (23.4) | 967 (24.9) |

| Never married | 6349 (17.7) | 698 (16.2) | 943 (17.3) | 712 (18.4) |

| Family income-to-poverty ratio | ||||

| 0 to <1 | 6980 (19.4) | 756 (17.5) | 1090 (19.9) | 664 (17.1) |

| 1 to <2 | 9041 (25.2) | 1103 (25.6) | 1355 (24.8) | 1012 (26.1) |

| 2 to <3 | 5184 (14.4) | 686 (15.9) | 741 (13.6) | 589 (15.2) |

| 3 to <4 | 3708 (10.3) | 472 (10.9) | 547 (10.0) | 357 (9.2) |

| 4 to <5 | 2609 (7.3) | 389 (9.0) | 390 (7.2) | 267 (6.9) |

| ≥5 | 8407 (23.4) | 910 (21.1) | 1335 (24.5) | 991 (25.5) |

| Body mass indexc,d | ||||

| <25 | 9495 (26.8) | 1296 (30.5) | 1448 (26.8) | 856 (22.3) |

| 25 to <30 | 11 918 (33.6) | 1494 (35.3) | 1838 (34.0) | 1196 (31.2) |

| ≥30 | 14 082 (39.6) | 1448 (34.2) | 2124 (39.2) | 1785 (46.5) |

| Smoking statusc | ||||

| Current | 7659 (21.3) | 983 (22.8) | 1185 (21.7) | 750 (19.3) |

| Former | 9120 (25.4) | 1187 (27.5) | 1368 (25.1) | 1007 (26.0) |

| Never | 19 148 (53.3) | 2145 (49.7) | 2905 (53.2) | 2123 (54.7) |

| Physically active | ||||

| Yese | 16 633 (46.3) | 2495 (57.8) | 2142 (39.3) | 1920 (49.5) |

| No | 19 296 (53.7) | 1821 (42.2) | 3316 (60.7) | 1960 (50.5) |

| Disease historyf | ||||

| Arthritis | 10 287 (28.6) | 1244 (28.8) | 1522 (27.9) | 1278 (32.9) |

| Diabetes | 4602 (12.8) | 467 (10.8) | 641 (11.7) | 619 (20.0) |

| Thyroid problem | 3736 (10.4) | 435 (10.1) | 540 (9.9) | 480 (12.4) |

| Cancer | 3615 (10.1) | 416 (9.6) | 570 (10.4) | 440 (11.4) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1653 (4.6) | 238 (5.5) | 237 (4.3) | 201 (5.2) |

| Stroke | 1455 (4.0) | 175 (4.1) | 191 (3.5) | 200 (5.2) |

| Congestive heart disease | 1261 (3.5) | 165 (3.8) | 155 (2.8) | 148 (3.8) |

Abbreviations: GED, General Educational Development Test; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The cycles were the first, middle, and last cycles in the analysis, respectively.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported and categorized as non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White.

Numbers may not sum to the total number of participants due to missing data.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Reported vigorous or moderate activity during the last 30 days.

No history includes borderline diabetes, declined to answer, and don’t know.

Figure. Adjusted Mean Dietary Vitamin A Intake Values for Adults Participating in 2003-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Cycles.

Results are from day one 24-hour recall. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals of mean estimates. Estimates comparing non-Hispanic Black vs non-Hispanic White and Hispanic vs non-Hispanic White adults were statistically significant (P < .05), except for Hispanic vs non-Hispanic White in the 2017-2018 cycle (P = .07).

Discussion

Using a single 24-hour dietary recall, differences in dietary vitamin A intake persisted between Black and White adults, while the gap between Hispanic and White adults narrowed. Prepandemic data showed similar patterns.3 The mean intake levels among the 3 race and ethnicity groups were below the recommended dietary allowance (900 μg RAEs for men and 700 μg RAEs for women), suggesting many are at risk of diseases associated with low vitamin A intake.

The persistent difference in dietary vitamin A intake suggests that access to fresh fruits, vegetables, fish, and dairy may be limited in Black and Hispanic communities. Black households have experienced the highest percentages of food insecurity and very low food security among all racial and ethnic groups in the US between 2001 and 2021.4 Greater access to high-quality produce rich in vitamin A is needed. The Biden administration recently announced a new initiative aiming to improve nutrition by 2030.5

Study limitations include declining NHANES response rates and measurement errors in dietary recalls. Day 2 dietary data obtained through telephone interviews were not used because of racial differences between day 1 and day 2 intake.6 Use of day 1 and day 2 data (eg, the National Cancer Institute method) may lead to biased results in comparing racial differences in vitamin A intake.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

eAppendix. Supplementary Methods

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Ha K, Sakaki JR, Chun OK. Nutrient adequacy is associated with reduced mortality in US adults. J Nutr. 2021;151(10):3214-3222. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson C, Lyden E, Abresch C, Anderson-Berry A. Serum retinol concentrations, race, and socioeconomic status in of women of childbearing age in the United States. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):508. doi: 10.3390/nu8080508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.USDA Agricultural Research Service . What We Eat in America, NHANES 2017-March 2020 Prepandemic. Published 2022. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/1720/Table_2_NIN_RAC_1720.pdf

- 4.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service . Trends in US food security. Published 2022. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/interactive-charts-and-highlights/#trends

- 5.The White House . Biden-Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health. Published September 2022. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/White-House-National-Strategy-on-Hunger-Nutrition-and-Health-FINAL.pdf

- 6.Steinfeldt LC, Martin CL, Clemens JC, Moshfegh AJ. Comparing two days of dietary intake in What We Eat in America (WWEIA), NHANES, 2013-2016. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2621. doi: 10.3390/nu13082621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Supplementary Methods

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement