Abstract

The political status of Puerto Rico has been discussed in US Congress for decades. This article examines the main features of the island and key issues that make its political status increasingly relevant. It analyzes the results of popular referendums and their impact on the political status of the territory. Moreover, it addresses Joe Biden’s position on the issue, outlines the procedure for admitting a territory to the United States as a state, and examines the bills that are currently under consideration by Congress. This article also analyzes the factors that prevent Puerto Rico from becoming a state and the prospects that Puerto Rico will be granted statehood in the future.

Keywords: political status of Puerto Rico, unincorporated territory of the United States, American citizens, popular referendums, 51st US state, bills on the political status of Puerto Rico

INTRODUCTION

The territory of Puerto Rico is located on the island of the same name in the Caribbean and is part of the Greater Antilles archipelago, which is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean in the north and the Caribbean Sea in the south. The first settlers of Puerto Rico were the Ortoiroids, an ancient culture. It is believed that their tribe originated in the Orinoco Valley in South America, and then they moved to the Antilles. By the time Christopher Columbus arrived in 1493, the Taíno tribe lived in Puerto Rico. The discoverer of the New World declared the island a colony of Spain and gave it the name San Juan de Bautista in honor of St. John the Baptist.

In 1508, the Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon landed on the island and founded the city of Caparra, the first European settlement. A year later, having subjugated the majority of the indigenous population, he proclaimed himself the first governor of Puerto Rico. The very name Puerto Rico means “rich port” in Spanish. At first, this was the name of the administrative center of the colony, but gradually the name was assigned to the entire territory. In 1509, the city of San Juan was founded, which became the capital largely due to its favorable geographical position.

With the advent of European conquerors, the Taino culture fell into decline; the population of about 30 000 in 1508 dropped to a little more than 1000 in 1530.1 With the importation of slaves from Africa, various diseases began to penetrate the island, which caused epidemics among the indigenous people. The sharp decline in the population was also caused by the difficult working conditions on the cane plantations and displacement from ancestral lands. The remaining Taínos mingled with Spanish settlers and African slaves, resulting in the formation of a new nationality, Puerto Ricans.

As a result of the Spanish–American War, the United States of America gained new territories, including Puerto Rico. The island has a number of features. First, its area is 9104 sq. km, making it the third largest island in the United States after Hawaii and Kodiak, as well as the largest of the 16 American territories. Second, Puerto Rico is relatively close to the mainland: the distance from San Juan to the capital of the nearest state of Florida is less than 1700 km. Third, more than 3 million people live in Puerto Rico, making it the most densely populated territory in the United States.2 Approximately 5.8 million Puerto Ricans live on the continental United States, i.e., almost two times more than on the island.3 The Jones–Shafroth Act was signed in 1917, granting US citizenship to Puerto Ricans. This, along with the fact that many have relatives living on the mainland and the relatively close location of the island, made it more and more likely for people to move.

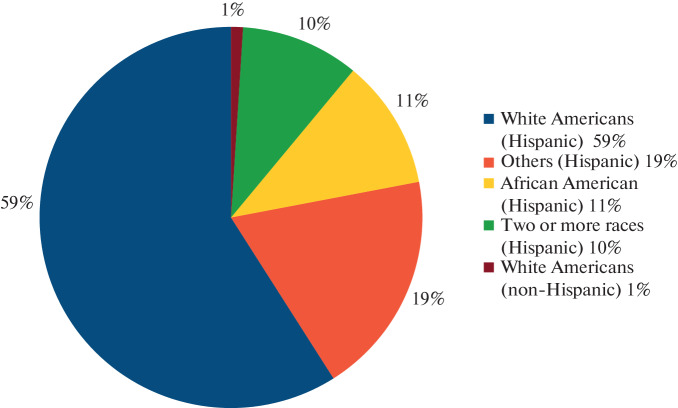

In 2020, more than 98% of Puerto Ricans were Hispanic. Figure 1 shows the racial and ethnic composition of the island.4 Most Puerto Ricans categorize themselves as “White American” racially. The chart does not show racial–ethnic groups that make up less than 1%.

Fig. 1.

Racial and ethnic composition of Puerto Rico. Source: Puerto Rico, 2020, Data USA. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/puerto-rico. Cited June 15, 2022.

PUERTO RICO IS AN UNINCORPORATED ORGANIZED TERRITORY OF THE UNITED STATES

After joining the United States, the island was given the status of “unincorporated organized territory of the United States,” which it retains to this day. The official name is the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The official languages are Spanish and English and the national currency is the American dollar.

Supreme power belongs to the US Congress. The island has its own system of self-government, with three branches of government. Puerto Rico also has its own constitution, while the powers of the US Constitution are limited on the island. Since January 3, 2017, the position of Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico in the US Congress has been held by Jennifer Gonzalez-Colon, a representative of the New Progressive Party (NPP) of Puerto Rico, which actively advocates joining the United States as a state. She is Puerto Rico’s only representative in Congress. Jennifer Gonzalez-Colon not only became the first woman to hold the office, but she received more votes than any other candidate elected to the position.5 As of January 2, 2021, the governorship of Puerto Rico is held by Pedro Pierluisi, who was Puerto Rico’s representative in the US Congress from 2009 to 2017.

In recent years, due to a number of factors, the issue of political status has taken on particular relevance to Puerto Rico. First, there has been a series of natural disasters, including Hurricane Maria, which hit the island in 2017, leaving enormous losses and causing a humanitarian disaster, as well as numerous earthquakes in 2019–2021.

Second is the protracted economic crisis. From 2004 to 2020, the economic growth rate decreased by almost 12.5%; the population of the island decreased by more than 16%; and public debt amounted to approximately $70 billion, i.e., 68% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020.6 The coronavirus has further exacerbated the situation. If before the pandemic the unemployment rate in Puerto Rico was above 8%, then during the pandemic it reached a record 23%.7 At the same time, the authorities of the island do not have economic sovereignty; that is, they do not have supremacy in domestic economic affairs and economic equality in the international arena, since the supreme power, including in trade and currency issues, is assigned to federal regulatory bodies.

San Juan receives financial assistance from Washington, but it is obvious that it is not enough to solve the problems of the island. The disbursement process is complicated by multiple checks on how the funds will be distributed due to bureaucracy problems in Puerto Rico and the wait for federal approval. For example, in 2019, the US Congress allocated $42.5 billion, while the damage caused by Hurricane Maria amounted to $90 billion; after the $42.5 billion was allocated, Puerto Rico received less than $14 billion in the first month.8

In addition to natural disasters and a deep economic crisis, Puerto Rico has longstanding problems, including the low level of political representation in the US Congress and the lack of voting rights at a federal level. Pedro Pierluisi put it this way: “We are very much a part of America. We want to have the same rights. We want to vote for president, have congressional representation—voting congressional representation—and equal treatment in all the federal programs.”9 The population of Puerto Rico is larger than more than 20 states. Despite this, there are no representatives of Puerto Rico in the upper house of Congress, and only one serves in the lower house, which does not have the right to vote. Residents of the island cannot participate in midterm or US presidential elections, as the territory is not a state. They only vote in elections for local governments and the Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico. Former governor Anibal Vila commented as follows: “Yes, we still have self-government, but the truth is that the sovereignty of the people of Puerto Rico and all the important powers are in Congress, not here.”10

Moreover, US citizens living on the island face limited access to federal assistance programs such as Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). This is because Puerto Rico is not a state and its residents do not pay all federal taxes.

Speaking to then US Vice President Joe Biden in 2012, one Puerto Rican said “I am Puerto Rican, and despite Puerto Ricans possessing American citizenship by birth, and thousands of brave Puerto Rican soldiers like my father having served and even died for our nation, many dying as we speak, we are denied equal voting and representation rights under the American flag.”11 Becoming a state would give the island more opportunities for recovery and development, including more financial resources to deal with the pandemic and its economic and humanitarian consequences, as well as enfranchisement of American citizens at the federal level, equal representation in the US Congress, and equal access to social assistance programs.

REFERENDUMS: RESULTS AND IMPACT ON THE CHANGE IN POLITICAL STATUS

In Puerto Rico, six referendums have been organized to determine which political status residents prefer. The last referendum took place in 2020. Many Americans support statehood. Others vote to keep the current status, and some are in favor of alternative paths, including independence, but this option, as a rule, does not enjoy widespread support from the people of Puerto Rico. Table 1 shows the results of referendums in percentage terms.12

Table 1.

Referendum results in Puerto Rico, thousand voters

| Political status of Puerto Rico | 1967 | 1993 | 1998 | 2012 | 2017 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current political status | No | No | 0.1 | No | 1.3 | No |

| Commonwealth | 60.4 | 48.6 | No | No | No | No |

| State | 39 | 46.3 | 46.5 | 61.3 | 97.2 | 52.5 |

| Independent state | 0.6 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 1.5 | No |

| Free associated state | No | No | 0.3 | 33.2 | Merged with the Independent State variant | No |

| None of the above | No | No | 50.3 | No | No | 47 |

| Referendum turnout, % | 66 | 74 | 71 | 79 | 23 | 55 |

Puerto Rico’s Plebiscites, Puerto Rico Report, May 2022. https://www.puertoricoreport.com/puerto-ricos-plebiscites/#.Yo354pJBzIV (date of the request Jun 16, 2022).

As can be seen from Table 1, in 1967, most voters voted for commonwealth status and almost 40% supported joining the US as a state. By 2020, the situation had changed significantly. It is also worth noting that the frequency of nationwide voting has grown. If 26 years have passed between the first and second referendum, then only 5 years have passed between the second and third and only 3 years between the penultimate and the last, which proves the relevance of the issue.

There was no option for commonwealth in 1998, 2012, and 2017. This is due to the fact that the US Congress rejected the definition of this term as proposed by the authorities of Puerto Rico.13 The ballots of 1998 and 2017 offered maintaining the current territorial status as an option, but very few voters voted for it. In the 1998 vote, the Popular Democratic Party (PDP), Puerto Rico’s second major party to support maintaining the current territorial status, called on its constituents to vote for the none of the above, which received 50.3% of the vote. Of course, this option was also chosen by those who did not support any of the other proposed ones.

In 2012, there was option for no none of the above on the ballot; voters opposed to statehood but against independence cast their votes for the status of free associated state (33.2%), while 61.3% voted for statehood. The US federal government has repeatedly said that Puerto Rico has the right to self-determination. In April 2021, during a press conference, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi said “On the statehood issue, that’s up to the people of Puerto Rico. It’s up to them to decide whether they want to be a state, and then we’ll see what happens after that.”14

It is worth noting the turnout. From 1967 until 2012, most Puerto Ricans took part in referendums. A dramatic change came in 2017. That year, two opposition parties—the Popular Democratic Party and the Puerto Rican Independence Party—boycotted the vote, resulting in only 23% of voters taking part. Most of them chose statehood.

The latest referendum, which took place in 2020, was different from previous ones. If earlier there were several options for political status on the ballots, then in 2020 the general vote was held in the format of a question, which was formulated as follows: “Should Puerto Rico be immediately admitted to the United States as a state?” This was the only option, making it possible to learn the attitude of residents to statehood. The wording emphasized the relevance of the topic. That year, the voter turnout was 55%; that is, out of 2.3 million voters, 1.2 million voted.15 At the same time, 52.3% voted in favor of changing the political status in favor of statehood and 47% voted against it.

Thus, the history of referendums that were held from 1967 to 2020 demonstrates the following: first, the proportion of voters supporting maintaining the current political status has declined, while the proportion in favor of joining the United States as a state has increased. At the same time, the group of Puerto Ricans voting for independence remains relatively small. Second, the level of political participation of Puerto Rican voters has declined in recent years. In this regard, it is not possible to argue that the majority support joining the United States as a state or maintaining the current status, which fundamentally affects the prospects for considering the issue of the political status of the island in the US Congress.

Third, it is important to note the disunity of the main political forces of the island. There are three main political parties in Puerto Rico: the New Progressive Party, the Popular Democratic Party, and the Puerto Rican Independence Party. Each of them defends a certain position regarding political status that contradicts the positions of the other two parties. Thus, the New Progressive Party actively advocates granting Puerto Rico statehood, the Popular Democratic Party supports the preservation of the current status, and the Independence Party promotes the idea of establishing the island as a separate state. The disunity of the main political forces on this issue not only leads to incidents such as the boycott of the popular vote that took place in 2017, but it also complicates the negotiation process with Washington regarding political status and weakens the position of Puerto Rico as an American territory.

In 2020, Joe Biden stated: “I happen to believe that statehood would be the most effective means to ensure that residents of Puerto Rico are treated equally with equal representation at the federal level. The people of Puerto Rico must decide and the United States federal government must respect and act on that decision.16 After becoming president, Biden began to attach great importance to the issue of Puerto Rico. He began full-scale work to restore the territory. In 2021 alone, the Federal Emergency Management Agency approved almost $3 billion for 3542 different Hurricane Maria and earthquake relief projects, an unprecedented level of support affecting all sectors of Puerto Rico’s economy.17 In February 2022, President Biden announced a new aid package. However, the issue of granting statehood to the island, despite the support of the president, is moving at a slow pace.

It is important to note that referendums held in Puerto Rico are not legally binding, so they do not have the proper impact on the issue of political status. Only Congress can authorize a referendum, as it has supreme power. In other words, neither the results of popular votes, the decisions of the authorities of Puerto Rico, nor the orders of the US executive branch play a key role in granting statehood to the territory. According to Article 4, Section 3 of the US Constitution, it is Congress that admits new states to the Union. This requires a simple majority of votes in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

BILLS REGARDING THE POLITICAL STATUS OF PUERTO RICO: CONTROVERSY IN THE US CONGRESS

The issue of adding Puerto Rico as a state has been discussed in Congress for decades, but no decision has been made. It is an issue that has become particularly relevant in recent years. Many congresspeople have spoken out in support of the change in political status. Senator Bernie Sanders said “For too long, the people of Puerto Rico have faced inadequate [federal] assistance and colonial exploitation in the wake of natural disasters, a decade-long crippling economic crisis, and unjust human suffering.”18

Former Democratic National Committee Chairwoman Donna Brazile, discussing the political status of Puerto Rico, made the following statement: “This is about making America a more perfect union. It’s the oldest constitutional democracy in the world and yet some of its citizens do not have all the full voting rights because of where they reside. If we’re going to end racial injustice in America and talk about a new beginning for the country, we can’t sidestep old issues.”19 This affects more than 3 million American citizens whose rights are limited and whose standard of living is much lower than in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

There are currently two bills pending in Congress regarding the political status of the island: HR 1522, the Puerto Rico Statehood Admission Act of 2021, and HR 2070, the Puerto Rico Self-Determination Act of 2021. The first bill was introduced by Darren Soto, a member of the Florida House of Representatives of Puerto Rican origin. It provides for holding a referendum on the island, approved by Congress, that is, with legally binding force. It is planned that, during the voting, residents will answer the following question: “Should Puerto Rico be admitted immediately to the Union as a state?”

The initiative was supported by 82 members of the House of Representatives, including 63 Democrats and 19 Republicans.20 It is worth noting the following: first, the 17 congresspeople who are in favor of passing the bill represent the state of Florida. This is due to the fact that Puerto Rican Americans are the second largest group among the Hispanic diaspora in the United States, and the largest group of Puerto Ricans in the mainland United States is in the state of Florida, where they make up more than 20% of the entire Hispanic community.21 The 13 other members of Congress who supported the bill represent the state of California, which has a significant Hispanic population, and in 2019 their number exceeded 15 million, while the proportion of white Americans in the state was just over 14 million.22

Second, the bill is supported by delegates from Guam and the Virgin Islands, whose position is similar to that of Puerto Rico. Their representatives do not have the right to vote in Congress either, and their residents are US citizens, but cannot participate in federal midterm and presidential elections. In the future, these islands could potentially become states. The fact that they are in favor of this bill demonstrates their position on the issue of changing the political status of their territories.

Some congresspeople believe that the bill limits the will of the people of Puerto Rico, as it disregards other options, in particular, independence or the status of a Freely Associated State. In 2021, Nydia Velázquez, the first Puerto Rican woman to serve in Congress; Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Puerto Rican member of the House of Representatives; and Bob Menendez, Cuban-born US Senator, introduced a bill for Puerto Rico’s right to self-determination. It provides for the selection of delegates by the people of Puerto Rico, who, after agreement with Congress and the US Department of Justice, will present several alternative options for the current status of the island. These include state status, independent state, free associated state, and any other option other than current status. It is noteworthy that the bill was supported by 77 members of the Democratic Party.23

OBSTACLES TO PUERTO RICO BECOMING THE 51ST US STATE

It is important to note a number of factors that prevent Puerto Rico from obtaining statehood. To do this, let us look at history. In 1901, the US Supreme Court ruled on the status of the island territories that came under US administration after the Spanish–American War of 1898. Puerto Rico became an “unincorporated territory”; such statuses was given to territories that were not considered potential states.

Some congresspeople (including Senator Lisa Murkowski, who was born in Alaska when it was still an incorporated territory of the United States24) who are now actively campaigning for statehood for Puerto Rico, refer to Alaska, which, in their opinion, has gone through the same difficult path. Alaska joined the Union in 1959, and the bill to join as a state was put forward in 1916. Moreover, a referendum was held in the territory. However, such a comparison is not entirely correct, since Alaska, like Hawaii, had the status of incorporated territory before joining the union; that is, they were initially considered as potential states.

Another important factor is the position of members of the Republican and Democratic parties. Republicans tended to oppose statehood, which hindered the consideration of bills. This is largely due to the political views of Hispanic Americans, who make up the majority of Puerto Rico. Traditionally they expressed support for the Democratic Party. Republicans feared that, if Puerto Rico joined the United States as a state, Democratic members from the new state would be elected to Congress and the influence of Republicans would decrease.

The Pew Research Center finds that most Puerto Ricans are conservative.25 This explains why Americans living on the island tend to elect local leaders who identify as Republicans. Puerto Rican Resident Commissioner Jennifer Gonzalez-Colon is also a spokesperson for this party. In the mainland United States, six Republicans from Florida and a significant number of Republicans across the country are in favor of granting Puerto Rico statehood.26 These changes, of course, contribute to the consideration of bills.

The most important factor is the will of the people of Puerto Rico. The proportion of voters who support statehood is gradually increasing. However, it is not possible to assert that the majority will vote for it. One complicating factor is the relatively low political activity of Puerto Ricans in recent years. If more than 65% of voters took part in the referendums that took place in 1967, 1993, and 1998, and in 2012 there was a record 79%, then in 2020 a little more than half voted. This dynamic may have been driven by the turmoil that Puerto Rico has experienced in recent years; the divided politics of the three main political forces; and the realization by voters that the ongoing referendums are not legally binding, meaning their outcomes cannot affect the situation.

It is important to note that the discussion of the political status of Puerto Rico has brought divisions among Democrats: some are backing Darren Soto’s statehood bill while others are pushing for Puerto Rico’s right to self-determination initiative, which provides multiple options for the island’s future. The first bill, of course, is a faster way to resolve the issue, because, firstly, it provides only one option, and secondly, it finds support among the congresspeople of the two parties. However, its adoption may not take into account the views of a large part of the population of Puerto Rico, in particular those residents who are in favor of maintaining the current status and those who prefer independence. Although the latter option has never enjoyed widespread support among Puerto Ricans, it is worth noting that for decades, Puerto Rico did not have such an opportunity, so it did not receive much attention from the inhabitants of the island.

In this regard, Puerto Rico’s second Self-Determination Act represents a more equal opportunity. However, a bill that includes several alternatives is likely to take significantly longer to consider, agree on, and pass, which could negatively affect Puerto Rico due to its difficult situation. Moreover, this initiative is supported by only one party.

In the United States, the federal bill approval system has five stages: introduction, approval by the House of Representatives, approval by the Senate, referral to the president, and making the bill legally binding. At the moment, both bills are in the first stage, despite the fact that they were put forward in 2021. This suggests that the review process is moving at a slow pace, and the issue of the political status of Puerto Rico itself is not of paramount importance in the US Congress.

Carlos Ivan Gorrín Peralta, professor at the Inter American University of Puerto Rico, identifies three criteria for granting statehood to a territory.27 First is the will of the majority. Second is the acceptance and observance of the fundamental values of American democracy. Puerto Rico has a relatively high level of corruption and bureaucracy, which violates the principles of a democratic system. Third is solvency of the territory, that is, the ability to ensure the work of the government of the future state and carry its share of the federal budget. It will be difficult for Puerto Rico to do this in the near future.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the referendums show that a large proportion of Americans living on the island support joining the United States as a state. However, it is not yet a majority. Until the will of the Puerto Ricans is clear, Congress will not give priority to this issue.

Congresspeople are promoting initiatives to change the political status of the island. It is noteworthy that the first bill finds support among both parties, while only one party is in favor of the second bill. Although the number of congresspeople supporting the bills is gradually increasing, at the moment this is not enough to pass them. Complicating matters is the fact that opinion in Congress is divided.

Thus, it can be assumed that Puerto Rico is unlikely to become an American state during the presidency of Joe Biden. In regards to the prospects for resolving this issue in the next few decades, the unincorporated territory of the United States has a chance to become a state, but it will depend on the will of the people of Puerto Rico and the level of support in Congress.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Puerto Rico, Genocide Studies Program, Yale University. https://gsp.yale.edu/case-studies/colonial-genocides-project/puerto-rico, Cited February 25, 2022.

United States Territories 2022, World Population Review, 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/states/puerto-rico-population. Cited August 17, 2022.

Puerto Rican population in the States, Puerto Rico Report, October 2020. https://www.puertoricoreport.com/puerto-rican-population-in-the-states/#.Yo3375JBzIV. Cited February 25, 2022.

Puerto Rico, 2020, Data USA. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/puerto-rico/. Cited June 15, 2022.

Jenniffer González-Colón, Puerto Rico, House Republicans, GOP. https://www.gop.gov/member/jenniffer-gonzalez-colon/. Cited March 15, 2022.

Cheatham, A. and Roy, D., Puerto Rico: A US territory in crisis, Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/puerto-rico-us-territory-crisis. Cited June 18, 2022.

Ibid.

Timm, J.C., Fact check: Trump says Puerto Rico got $92 billion. They’ve seen only a fraction, NBC News, June 2019. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/fact-check-trump-says-puerto-rico-got-92-billion-they-n1031276. Cited February 17, 2022.

Luciano, L., Is statehood the answer to Puerto Rico’s problems?, CBSNews, June 2021. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/puerto-rico-statehood-debate/. Cited March 7, 2022.

Ibid.

Does Joe Biden support statehood for Puerto Rico?, PR51st, December 2020. https://www.pr51st.com/does-joe-biden-support-statehood-for-puerto-rico/. Cited April 6, 2022.

Puerto Rico’s plebiscites, Puerto Rico Report, May 2022. https://www.puertoricoreport.com/puerto-ricos-plebiscites/#.Yo354pJBzIV. Cited October 7, 2022.

None of the above: The strange history of Puerto Rico’s status votes, PR51st, June 2019. https://www.pr51st.com/none-of-the-above-the-strange-history-of-puerto-ricos-status-votes/. Cited July 5, 2022.

Manriquez, P., Speaker Pelosi says Puerto Rico must determine its own status, Latino Rebels, April 2021. https://www.latinorebels.com/2021/04/22/speakerpelosipuertoricostatus/. Cited May 16, 2022.

Corujo, C., Puerto Rico votes in favor of statehood. But what does it mean for the island?, ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/puerto-rico-votes-favor-statehood-island/story?id=74055630. Cited May 15, 2022.

Does Joe Biden support statehood for Puerto Rico?, PR51st, December 2020. https://www.pr51st.com/does-joe-biden-support-statehood-for-puerto-rico/. Cited April 6, 2022.

Fact sheet: The Biden–Harris administration supports Puerto Rico’s recovery and renewal in its first year in office, The White House, January 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/20/fact-sheet-the-biden-harris-administration-supports-puerto-ricos-recovery-and-renewal-in-its-first-year-in-office/. Cited May 12, 2022.

HR1522—Puerto Rico Statehood Admission Act, 117th Congress (2021–2022). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1522/cosponsors?q=%7B"party"%3A"all"%7D. Cited August 19, 2022.

Smith, D., New stars on the American flag? Fresh hope as Puerto Rico and DC push for statehood, The Guardian, February 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/feb/20/puerto-rico-washington-dc-statehood-politics. Cited April 9, 2022.

US HR1522 Puerto Rico Statehood Admission Act, Bill Track 50. https://www.billtrack50.com/BillDetail/1336137. Cited August 19, 2022.

Puerto Rican population in the states, Puerto Rico Report, October 2020. https://www.puertoricoreport.com/puerto-rican-population-in-the-states/#.YhKTqyVBzIU. Cited January 15, 2022.

Resident population of California in 2019, by race and ethnicity, Statista, January 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/306026/california-population-ethnicity-race/. Cited April 19, 2022.

HR 2070: Puerto Rico Self-Determination Act of 2021, GovTrack.us. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/117/hr2070/cosponsors. Cited August 19, 2022.

Lopez, M.H., Sen. Murkowski could move the Puerto Rico statehood bill forward, The Hill, Sept. (2021). https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/542064-sen-murkowski-could-move-the-puerto-rico-statehood-bill-forward. Cited July 16, 2022.

Rashid Carlos Jamil Marcano Rivera, Puerto Rico wants statehood – but only Congress can make it the 51st state in the United States, The Conversation, December 2020. https://theconversation.com/puerto-rico-wants-statehood-but-only-congress-can-make-it-the-51st-state-in-the-united-states-150503. Cited April 7, 2022.

Lopez, M.H., Sen. Murkowski could move the Puerto Rico statehood bill forward, The Hill, September 2021. https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/542064-sen-murkowski-could-move-the-puerto-rico-statehood-bill-forward. Cited July 16, 2022.

Newkirk, V.R., II, Puerto Rico’s plebiscite to nowhere, The Atlantic, June 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/06/puerto-rico-statehood-plebiscite-congress/530136/. Cited June 2, 2022.

Marina Andreevna Chernykh is a Laboratory Researcher at the Arbatov Institute for US and Canada Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences.