Abstract

Interventions engaging men that challenge unequal gender norms have been shown to be effective in reducing violence against women (VAW). However, few studies have explored how to promote anti-VAW positive masculinity in young adults. This study aims to identify key multicountry strategies, as conceived by young adults and other stakeholders, for promoting positive masculinities to improve gender equity and prevent and target VAW. This study (2019–2021) involved young adults (aged 18–24 years) and stakeholders from Ireland, Israel, Spain, and Sweden. We applied concept mapping, a participatory mixed-method approach, in phases: (1) brainstorming, using semi-structured interviews with young adults (n = 105) and stakeholders (n = 60), plus focus group discussions (n = 88), to collect ideas for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinity; (2) development of an online questionnaire for sorting (n = 201) and rating ideas emerging from brainstorming by importance (n = 406) and applicability (n = 360); (3) based on sorting and rating data, creating rating maps for importance and applicability and clusters/strategies using multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis with groupwisdom™ software; and (4) interpretation of results with multicountry stakeholders to reach agreement. The cluster map identified seven key strategies (41 actions) for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinities ranked from highest to lowest: Formal and informal education and training; Preventive education and activities in different settings/areas; Skills and knowledge; Empathy, reflection, and understanding; Media and public efforts; Policy, legislation, and the criminal justice system; and Organizational actions and interventions. Pattern matches indicated high agreement between young people and stakeholders in ranking importance (r = 0.96), but low agreement for applicability (r = 0.60). Agreement in the total sample on prioritizing statements by importance and applicability was also low (r = 0.20); only 14 actions were prioritized as both important and applicable. Young people and stakeholders suggested seven comprehensive, multidimensional, multi-setting strategies to facilitate promoting positive masculinity to reduce VAW. Discrepancy between importance and applicability might indicate policy and implementation obstacles.

Keywords: domestic violence, perceptions of domestic violence, prevention, sexual assault, intervention/treatment, youth violence

Background

Previous research has shown that hegemonic masculinity is less likely to support gender equity and more likely to be involved in the perpetration of men’s violence against women (VAW) and intimate partner violence (IPV), while positive forms of masculinity are more accepting of gender equity and less likely to be engaged in gender-based violence (GBV) (Fulu et al., 2013; Salazar et al., 2020). Research has also shown adolescents and young adults are more likely to be engaged in VAW as perpetrators or victims (Edwards et al., 2014; Herbert, 2021; World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). For example, dating violence at this age indicates that perceptions of masculinity and VAW are likely formed in early adulthood (Jennings et al., 2017). Therefore, interventions that target early adulthood might be highly effective (Lundgren & Amin, 2015). However, few studies have explored how positive masculinity can be promoted, particularly among young people, to engage men in gender equity, and IPV and VAW prevention.

Ending men’s VAW is essential for achieving healthy and thriving societies; as such, it has been named in Goal 5 (Achieving Gender Equality) of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (Sachs, 2012). While women of all ages, socioeconomic status levels, and countries are affected by VAW (WHO, 2021), its prevalence varies by age, with recent evidence suggesting younger women experience higher exposure to violence. Global data from the WHO has shown that women’s exposure to physical/sexual violence from a current or former partner in the last year was higher among women aged 15 to 30 years (15–16%) compared to women aged 30 to 49 years (5–13%) (WHO, 2021). Recent global data show that past-year IPV was 16% (14–19%) and 16% (13–19%) among young women aged 15 to 19 years and 20 to 24 years, respectively, compared to 13% (11–17%) among women aged 30 to 34 years, and 10% (8–13%) among women aged 40 to 44 years (Sardinha et al., 2022). A study based on data from a survey conducted by the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) showed that, among young women aged 18 to 24 years, prevalence of current physical or sexual IPV was 7%, and lifetime psychological abuse was almost 30%, compared to 5% and 26%, respectively, in women aged 25 to 29 years (Sanz-Barbero et al., 2018). Studies in high-income settings (Daoud et al., 2012; Herbert, 2021; Jennings et al., 2017; Renner & Whitney, 2010; Sanz-Barbero et al., 2019) have found that IPV is pervasive among young women. Of women who reported ever being exposed to violence, IPV ranged from 23% in a rural area survey in the United States (Edwards et al., 2014) to 40% in a population-based UK study (Herbert, 2021), and 52% in Canada (Daoud et al., 2012). This is an important issue of concern, given evidence showing that perpetration or exposure to VAW during childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood is a risk factor for repeated VAW exposure or perpetration later in life (Cui et al., 2013; Stöckl et al., 2014). Preventing, detecting, and responding to VAW among young people is thus paramount for decreasing its incidence later in life and supporting women’s overall health.

Preventing and responding to VAW in general, including among young people, requires a multipronged societal response (García-Moreno et al., 2015; Morrison et al., 2007). Research shows these coordinated actions must include strengthening women’s access to the justice system (e.g., improving countries’ legal frameworks and police response), facilitating VAW detection by the health-care system (Daoud et al., 2019), increasing women’s access to supportive and rehabilitation services (i.e., free legal aid, housing stability) (Daoud et al., 2016), preventing violence by challenging social norms underpinning it (García-Moreno et al., 2015; Morrison et al., 2007), and supporting a gender transformative educational approach (Pérez-Martínez et al., 2021).

With regard to challenging social norms, evidence shows that engaging young men in VAW prevention is beneficial. Their involvement can transform unequal gender norms (Jewkes et al., 2015) and change masculine ideals that sustain and promote VAW as a tool for controlling women (Morrison et al., 2007). A systematic review of interventions aimed at decreasing IPV and sexual violence in adolescent populations showed that school and community-based interventions, as well as parenting interventions, can challenge unequal gender norms (including harmful forms of masculinities) and succeed in decreasing VAW (Lundgren & Amin, 2015). This finding is in line with data from recent interventions conducted in Mexico (Makleff et al., 2020) and South Africa (Gibbs et al., 2020).

In this paper, we define masculinities as socially constructed patterns of actions considered appropriate for men in a given society (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Connell and Messerschmidt (2005) argue that multiple forms of masculinities coexist and interrelate through power relations, dominance, and marginalization (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Among these, “hegemonic” masculinity is defined as “the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees the dominant position of men (Conell, 2005). Several studies internationally have shown that men who endorse beliefs about hegemonic masculinity and values are at higher risk of enacting VAW (Fulu et al., 2013; Gibbs et al., 2018; Jewkes et al., 2011).

Evidence has uncovered other masculinities that reject VAW and strive for gender equity (Elliott, 2015; Pérez-Martínez et al., 2021; Salazar & Öhman, 2015; Taliep et al., 2021; Torres et al., 2012). In this paper, we name these “positive masculinities.” Enacting positive masculinities can be challenging, as men might experience social pressure to conform to unequal gender norms or face exclusion by peer groups or family (Casey & Ohler, 2012; Torres et al., 2012). Thus, it is critical to identify how positive masculinities can be promoted and sustained in a diversity of societal settings. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have identified which actions/strategies young men, young women, and other stakeholders believe are needed to promote and support positive anti-VAW masculinities.

In the current study, we aim to identify conceptions of existing masculinities and develop a “road map” of key strategies for promoting positive masculinities that oppose VAW and support gender equity across four countries (Ireland, Israel, Spain, and Sweden).

Methods

Study Setting

The current study is part of a multicountry study (2019–2022) conducted in Ireland, Israel, Spain, and Sweden. The study was approved by ethics board committees in each of the participating universities (one in each country, names withheld due to the JIPV policy of blind review). All participants provided signed or oral consent to participate in each study phase.

We use a mixed methods approach called concept mapping (CM) to identify ideas for promoting anti-VAW masculinities in the quantitative stage of brainstorming, then used these ideas to develop a survey that prompted participants to group the ideas into clusters and rank them by importance and applicability. CM is a widely used participatory research method for program planning and evaluation (Trochim & Kane, 2005; Trochim & McLinden, 2017). Rosas and Kane (2012) pointed out the high validity of using CM in different fields and contexts. It enables groups of participants to visualize ideas on an issue of mutual interest and develop common frameworks through a structured, participatory process (Trochim & Kane, 2005). Qualitative and quantitative data are generated and integrated through sequential phases, developing conceptual maps based on multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis (Kane & Trochim, 2007). A CM study consists of the following phases: (1) brainstorming ideas regarding a question of interest (a focal question); (2) consolidation of ideas and development of a structured questionnaire; (3) sorting and rating of preliminary ideas generated during brainstorming using the questionnaire developed in the previous phase; (4) analysis of quantitative data obtained through sorting and rating; (5) creation of the following: a “concept map,” that is, a map that is computed by a multidimensional scaling analysis, which locates each statement as a separate point on a map; a “point map,” a map that shows the statements or ideas were placed by multidimensional scaling; a “cluster map,” which shows how statements or ideas were grouped by the cluster analysis; “pattern matches,” that represent pairwise comparisons of cluster ratings across criteria such as different stakeholder groups or rating variables, using a ladder graph representation; and “Go-Zones” that include bivariate graphs of statement values for two rating variables within a cluster, divided into quarters above and below the mean of each variables, showing a “go-zone” quadrant of statements that are above average on both variables (Kane & Trochim, 2007, p. 13); and (6) interpretation of findings with study participants and stakeholders.

Study Sample, Recruitment, and Data Collection

Our target population included two main groups: young people and other stakeholders. The inclusion criteria for young people was age 18 to 24 years. This broad inclusion criteria allowed participation of a wide range of young people from diverse sections of society without any exclusion. Young people could be perpetrators of VAW or those that oppose VAW. Similarly, female participants could be women who experience/d violence or not. Also, young people could be active or not in organization that promote ideas related to gender equity and positive masculinity.

As for the stakeholders, inclusion criteria included working (at volunteer basis or for salary) with young people to promote ideas related to gender equity, masculinity, or feminism. The stakeholders in our sample included a range of professionals such as social workers, consultants, educators, health promoters and health educators, academics, and police. Stakeholders were recruited from relevant government ministries and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working with youth (youth, women’s and men’s organizations), in the four participating countries (Salazar et al, 2020). Individual participants were recruited through a purposeful snowball sample with the assistance of the study’s local advisory boards, community partners, youth and women’s organizations (NGOs), social media (e.g., Facebook), universities websites, flyers, and emails. Personal emails were sent to the individuals to invite them to participate. Table 1 presents the study sample for each phase. The participants in each phase overlap, as participants in one phase were invited to participate in the following phase.

Table 1.

Study Sample* and Distribution of Participants (Young People and Stakeholders) in Brainstorming, Sorting, and Rating Activities (1 and 2) in Participating Countries.

| Spain | Sweden | Ireland | Israel** | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brainstorming (September 2019 to May 2020) | |||||

| In-depth interviews with young people | 20 | 23 | 27 | 35 | 105 |

| In-depth interviews with stakeholders | 19 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 60 |

| Total for brainstorming | 39 | 35 | 41 | 50 | 165 |

| Sorting (July to November 2020 and March 2021) | |||||

| Stakeholders | 20 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 60 |

| Young men and women and nonbinary | 24 | 54 | 27 | 36 | 141 |

| Total for sorting | 44 | 67 | 40 | 50 | 201 |

| Rating 1 (importance) (July to November 2020 and March 2021) | |||||

| Stakeholders | 30 | 14 | 20 | 28 | 92 |

| Young men, women, and nonbinary | 70 | 60 | 76 | 108 | 314 |

| Total rating 1 | 100 | 74 | 96 | 136 | 406 |

| Rating 2 (applicability) (July to November 2020 and March 2021) | |||||

| Stakeholders | 30 | 14 | 20 | 24 | 88 |

| Young men, women, and nonbinary | 70 | 59 | 59 | 84 | 272 |

| Total for rating 2 | 100 | 73 | 79 | 108 | 360 |

The study samples in the different stages overlap as participants in one stage were invited to the next stages.

The sample in Israel included Palestinian-Arab and Jewish participants.

Brainstorming and collecting ideas on promoting anti-VAW positive masculinities

This phase (September 2019 to May 2020) aimed to elicit ideas for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinities in young people. Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) with young people, and semi-structured interviews with other stakeholders. In total, 165 people from all countries participated in the semi-structured interviews (105 young people, 60 stakeholders), and 88 young people participated in 12 FGDs (Table 1). The number of the semi-structured interview participants in each country ranged 20 to 35 for young people and 12 to 19 for stakeholders (Table 1). Interviews were conducted either face to face or by Zoom (following COVID-19 restrictions imposed in 2020).

Using the following questions, participants in the interviews and FGDs were asked to suggest ideas and actions to promote anti-VAW positive masculinities and support men who oppose VAW:

What can be done to promote masculinities that oppose violence against women among young men in your country? How so?

In order to reduce men’s violence against women and promote positive and nonviolent forms of manhood among young men we should . . .

Identification and consolidation of ideas on anti-VAW positive masculinities to develop a questionnaire

In this phase (April 2020 to July 2020), we identified and consolidated actions emerging from the brainstorming phase, then developed a questionnaire for use in the next phase of sorting and rating. Each country team read and cleaned up their local data by deleting redundant actions and ideas. These were then inputted into one file that included a total of 401 statements. Following multiple discussions, the multicountry research teams removed duplication (based on similarities, uniqueness, and relevance) to consolidate a shortlist of 101 statements. The list was further distilled into 58 statements/actions, then to 41, as the research teams agreed to shorten the number of statements in order to reduce the burden on participants (Kane & Trochim, 2007). Based on that final list of statements, we prepared an online questionnaire for sorting and rating. To ensure clarity and understanding of the statements, this questionnaire was pilot tested in each country with 5–6 young adults (ages 18–24 years) and stakeholders. The pilot revealed very few language changes in the instructions of the online sorting and rating activities. No changes were conducted on the statements or questions.

Sorting and rating phase

In this phase (July 2020 and March 2021), participants ranked actions and identified strategies (clusters) for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinities based on the statements and ideas in the previous phase. Recruitment took place by inviting participants from the previous phase of brainstorming, plus recruitment of new participants, with the help of the local partners and advisory board members, through social media, ads, and snowball sampling.

The study team sent an email to those who agreed to participate containing information about the study, instructions for conducting online sorting and rating activities, and a link for carrying out these activities. In each country, for this phase in particular, between 100 and 140 young people and stakeholders were recruited. In total, from all countries, 252 participated in the sorting activity; of these, 201 had complete data and were included in the analysis. In the rating activity, 406 participated in rating the importance of each idea, and 360 completed rating the applicability of each idea to their communities (Table 1).

In the sorting activity, participants were asked to use their own opinions to group the 41 statements into different piles “in a way that makes sense to them” and to give each group or category of items a descriptive name or label. In doing so, participants generated labels for their clusters of ideas/statements. In the rating activities, participants were asked to, first, rate the 41 ideas in terms of importance in promoting anti-VAW masculinity, and, second, rate the applicability of the idea in their country/community context. Rating was conducted online using a Likert-type scale for importance (1 = not important at all to 6 = most important) and applicability (1 = very hard to apply to 6 = very easy to apply in a participant’s community context).

Data analysis and creation of cluster maps, pattern matches, and Go-Zones

We used groupwisdom™ software to conduct analyses for data from sorting and rating.

All participating countries (except Ireland) translated the statements and cluster’s names into English after data cleaning. The groupwisdom™ software (The Concept System®, 2022) team linked all data files from the four countries into one data set, while Ben-Gurion University team, which led the CM study, analyzed the multicountry data.

We used multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis to identify clusters or groups of actions based on the participants’ sorting and rating (Kane & Trochim, 2007). Multidimensional scaling aggregates participant sorting patterns, creates x- and y-coordinates for each item, then plots them on a two-dimensional plane. Hierarchical cluster analysis uses these coordinates to create cluster solutions that we displayed visually as boundaries around groups of points on a plot called a cluster map. Data analysis resulted in the creation of a point map, a cluster map, cluster rating maps (for importance and applicability), Go-Zones, and pattern matches for the multicountry data.

The point map shows participants’ opinions of similarities and differences between statements. Each point represents a statement, the number beside represents a statement number of the 41 statements, and the distance between points indicates similarity (or that participants grouped these points into one cluster). Points cannot be moved. The further one statement is from another, the less likely it is that those statements were put into the same group; the closer, the more likely those statements were to have been put into the same group. Cluster rating maps were computed by averaging the rating of each item in the cluster (Kane & Trochim, 2007). As noted earlier, during sorting, participants suggested cluster names. The groupwisdom™ software produced cluster names based on the frequency with which these appeared. The research team discussed and agreed to the names, after which, following some modifications, they were approved by the study advisory board members and participants in the interpretation phase. The stress value of the study cluster solutions was 0.180. The idea of the stress value is similar to that of reliability. It measures the degree to which the distances on the cluster map are discrepant from the values in the input similarity matrix. A low stress value indicates a low discrepancy (Kane & Trochim, 2007).

The linear correlation between the cluster ratings of our study-sample subgroups was estimated using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) (Kane & Trochim, 2007). For pattern matches, cluster ratings, and Go-Zones, we compared importance and applicability for the total sample and among stakeholders versus young people.

Interpretation phase

A main objective of this phase was to agree on key strategies and statements within clusters that emerged from our analysis of the sorting and rating data from all participating countries. Results of this phase can inform policy and help with the design of customizable future interventions for use in various community settings in the participating countries (e.g., youth organizations, relevant ministries, NGOs, schools, universities, and colleges). For this purpose, we conducted a multicountry workshop via Zoom with young people (n = 12) and members of the advisory boards and community partners (n = 6) who participated in different study phases.

We used purposeful sample to recruit the participants in the multicounty workshop. The research team in each country sent an email to the local advisory board of the study and to previous study participants. The aim was to recruit four youth participants and two stakeholders from each country, including equal number of men and women in each group. Four study team members attended this workshop (ND, RB, ACT, MS). After introducing the CM study and presenting the main findings, two study team members (ND and RB) led a discussion with the goal of reaching agreement on the strategies and statements for promoting anti-VAW masculinity emerging from previous study phases. One team member took notes [initials withheld]. In general, wide agreement emerged among participants on the cluster map and statements in each cluster. The workshop served as a forum to exchange suggestions for improving the results, which included some modifications of cluster names, and moving Statement 25 from Cluster 6 about “Preventive, education and activities in different settings/areas,” to Cluster 2 on “Skills and knowledge” (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Cluster Solutions and Ideas for Promoting Anti-VAW Masculinity, Total Mean Scores and by Importance and Applicability.

| Importance (n = 406) |

Applicability (n = 360) |

Cluster total Average |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| 1. Empathy, reflection, and understanding | 4.76 (1.2) | 4.08 (1.3) | 4.42 (0.2) | |

| 2 | Help men identify and recognize that they have the qualities and abilities to contribute to preventing VAW | 4.81 (1.2) | 3.93 (1.3) | |

| 4 | Use personal stories of women who have experienced different forms of violence as an educational tool | 4.61 (1.3) | 4.56 (1.3) | |

| 14 | Present male role models who reject VAW to children and young people in families and communities and have them give lectures, classes, and programs | 4.72 (1.3) | 4.53 (1.3) | |

| 29 | Promote men’s empathy toward women experiencing violence, including understanding its effects on their lives | 4.94 (1.1) | 3.76 (1.3) | |

| 40 | Provide a nonjudgmental space for men to reflect on how their behaviors can foster VAW | 4.62 (1.3) | 3.75 (1.4) | |

| 30 | Promote understanding among men and women on how different groups of women experience violence differently, based on class, race, ethnicity, and citizenship status | 4.85 (1.3) | 3.93 (1.3) | |

| 2. Skills and knowledge | 5.10 (1.2) | 3.96 (1.3) | 4.53 (0.7) | |

| 19 | Develop men’s and boys’ skills to recognize, manage, and express feelings in a nonviolent way | 5.33 (1.1) | 4.01 (1.4) | |

| 32 | Educate men on how gender roles and VAW can harm their own health, happiness, and well-being | 4.81 (1.4) | 4.01 (1.4) | |

| 33 | Develop women’s and men’s skills on how to recognize and actively prevent and stop VAW | 5.27 (1.1) | 4.12 (1.3) | |

| 41 | Educate men to recognize how their upbringing, society, and life experiences influence their attitudes, values, and behaviors toward VAW | 5.07 (1.2) | 3.74 (1.4) | |

| 1 | Develop men’s skills to help them reject peer pressure and macho norms | 5.04 (1.2) | 3.54 (1.4) | |

| 25 | Educate men and women on what nonviolent, trustworthy, and respectful romantic relationships look like | 5.08 (1.2) | 4.32 (1.3) | |

| 3. Media and public efforts | 4.59 (1.3) | 4.11 (1.3) | 4.35 (0.2) | |

| 5 | Provide men who reject VAW with a wider public platform to speak out | 4.15 (1.6) | 4.17 (1.4) | |

| 9 | Promote continuous, fresh, and relevant male-led campaigns designed to prevent and reject VAW and promote gender equality | 4.37 (1.4) | 4.24 (1.3) | |

| 22 | Promote age-relevant and relatable mass media representations of positive and nonviolent forms of manhood | 4.79 (1.2) | 4.24 (1.4) | |

| 35 | Recruit high-profile public figures (actors, football players, filmmakers) to promote gender equality and nonviolent forms of manhood that reject VAW | 4.28 (1.4) | 4.42 (1.4) | |

| 39 | Establish a wide activist movement that opposes VAW and rejects violent forms of masculinity | 4.63 (1.4) | 3.88 (1.4) | |

| 13 | Promote forms of manhood that reject VAW in religious institutions, meetings, and congregations | 4.71 (1.4) | 3.35 (1.5) | |

| 37 | Raise public awareness about the problem and extent of VAW, and public responsibility in preventing it | 5.19 (1.1) | 4.46 (1.3) | |

| 4. Organizational actions and interventions | 4.32 (1.4) | 3.99 (1.4) | 4.15 (0.1) | |

| 10 | Provide or expand rehabilitation programs for men who perpetrate VAW, such as anger management treatment | 4.77 (1.3) | 3.98 (1.4) | |

| 21 | Provide ongoing financial security to activists and organizations which promote nonviolent forms of manhood in preventing VAW | 4.55 (1.3) | 3.83 (1.5) | |

| 28 | Establish an award and quality ratings for organizations and educational institutions that engage men for their work in preventing and tackling VAW | 3.63 (1.6) | 4.16 (1.4) | |

| 5. Policy, legislation, and the criminal justice system | 4.70 (1.4) | 3.69 (1.6) | 4.19 (0.1) | |

| 7 | Promote restrictive access to pornography for adults only | 4.01 (1.8) | 2.91 (1.9) | |

| 11 | Have longer sentences for people who commit acts of VAW | 4.66 (1.6) | 3.75 (1.7) | |

| 12 | Change the way the criminal justice system treats rape cases to understand the specific difficulties faced by rape victims, and to be more attentive toward their experiences | 5.39 (1.1) | 3.56 (1.6) | |

| 16 | Appoint more women in policy decision-making regarding VAW | 4.95 (1.3) | 4.19 (1.4) | |

| 26 | Establish special police units trained to identify and prevent VAW | 4.83 (1.4) | 3.88 (1.6) | |

| 36 | Establish a central government unit to improve coordination between different organizations, services, and programs working toward nonviolent forms of manhood | 4.48 (1.4) | 3.53 (1.5) | |

| 38 | Promote governmental support for men taking paternity leave and undertaking caregiving tasks/roles | 4.54 (1.5) | 3.93 (1.5) | |

| 6. Preventive education and activities in different settings/areas | 4.89 (1.2) | 4.32 (1.3) | 4.60 (0.1) | |

| 3 | Promote positive, nonviolent, and respectful forms of parenting in parents’ groups during antenatal/post-natal care | 4.96 (1.2) | 4.35 (1.3) | |

| 8 | Educate in workplaces about prevention of VAW | 4.86 (1.2) | 4.38 (1.4) | |

| 15 | Educate in sports organizations and clubs about positive and nonviolent forms of manhood and prevention of VAW | 4.69 (1.3) | 4.12 (1.3) | |

| 20 | Provide education on what healthy, positive, and nonviolent forms of being a man looks like | 5.06 (1.3) | 4.37 (1.3) | |

| 24 | Support and train youth groups, youth movements, student unions, gaming clubs, and different associations to promote a culture of gender equity and reject violent forms of manhood | 4.83 (1.3) | 4.34 (1.3) | |

| 7. Formal and informal education and training | 4.99 (1.2) | 4.23 (1.4) | 4.61 (0.1) | |

| 6 | Educate parents, children, and young people on the negative impacts of using pornography | 4.80 (1.4) | 4.17 (1.5) | |

| 17 | Support teachers to question their own prejudices on gender norms and VAW | 4.74 (1.3) | 4.34 (1.3) | |

| 23 | Implement mandatory sex education and sexual consent education in schools, universities, and community programs | 5.36 (1.2) | 4.38 (1.6) | |

| 27 | Implement after-school activities where students discuss norms around gender and violence | 4.28 (1.4) | 3.98 (1.5) | |

| 34 | Ensure that age-appropriate compulsory education about gender stereotypes, equality, and VAW is integrated across the school curriculum, starting at a young age | 5.34 (1.1) | 4.24 (1.4) | |

| 31 | Raise boys to respect women, reject VAW, and oppose unequal gender norms | 5.50 (1.0) | 4.29 (1.4) | |

| 18 | Educate young people to recognize and reject gender stereotypes in the media and popular culture | 4.86 (1.3) | 4.15 (1.3) | |

Note. VAW = violence against women.

Findings

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 2 presents the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. Of the initial 455 study recruits, 32 were excluded because they did not complete sorting and rating. The final sample included 423 participants with complete data: 326 young people and 97 stakeholders (77.1 and 22.9%, respectively). The mean age of the total study sample was 26.4 years; ages ranged from 18 to 72 years. The mean age of young participants was 21 years (range 18–24 years), and, for stakeholders, 38.4 years (range 25–72 years). One third of participants were from Israel, 24.8% from Ireland, 23.6% from Spain, and 18.4% from Sweden. About half (53.6%) defined their gender as “woman,” 44.9% as “man,” and 1% reported another gender. Similar to gender, 54.3% of participants reported being born female, 44.6% male, and 0.7% chose not to disclose. Almost half (48.1%) of all participants reported secondary/high school education as their last level of schooling, and 43.8% reported last completing higher education. Most young participants had completed secondary/high school (58%), while 80.4% of stakeholders completed higher education. Almost one third of study participants reported that they are involved in some way in activism related to VAW: 14.6% volunteer in an activist role regarding VAW/ positive masculinity, 10.4% are salaried employees of a community organization, and 8% are salaried in a government office.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants With Complete Sorting and Rating Data.

| Total N = 423 (100%) |

Young PeopleN = 326 (77.1%) |

Stakeholders N = 97 (22.9%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Country | |||

| Ireland | 105 (24.8) | 81 (24.8) | 24 (24.7) |

| Israel | 140 (33.0) | 111 (34.0) | 29 (29.8) |

| Spain | 100 (23.6) | 70 (21.4%) | 30 (30.9) |

| Sweden | 78 (18.4)) | 64 (19.6) | 14 (14.4) |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 227 (53.6) | 169 (51.8) | 58 (59.7) |

| Men | 190 (44.9) | 151 (46.3) | 39 (40.2) |

| Nonbinary | 5 (1.1) | 5 (1.5) | 0 |

| Chose not to disclose | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| What sex were you at birth? | |||

| Female | 230 (54.3) | 173 (53.0) | 57 (58.7) |

| Male | 189 (44.6) | 151 (46.3) | 38 (39.1) |

| Chose not to disclose | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) |

| Did not respond | 1 (0.2) | - | 1 (1.0) |

| Education (N = 413)* | |||

| No formal schooling | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Secondary school/high school | 199 (48.1) | 184 (58.0) | 15 (15.4) |

| College or university (BA, MA, PhD) | 181 (43.8) | 103 (32.4) | 78 (80.4) |

| Other training | 24 (5.8) | 22 (6.9) | 2 (2.0) |

| Did not respond | 7 (1.6) | 6 (1.8) | 2 (2.0) |

| Activism around violence | |||

| Salaried in a community organization | 44 (10.4) | 0 | 44 (45.3) |

| Salaried in a government office | 34 (8.0) | 0 | 34 (35.0) |

| Volunteering in activist role around VAW or positive masculinity | 62 (14.6) | 43 (13.1) | 19 (19.5) |

| Not involved in activist role around VAW or positive masculinity | 223 (52.7) | 223 (68.4) | 0 |

| Other | 60 (14.1) | 60 (18.4) | 0 |

Note. VAW = violence against women.

There were missing answers for education among young adults (N = 317). The percentage not reaching 100% due to missing cases.

Clusters and Statements for Promoting Anti-VAW Masculinity

Our analysis revealed a final list of 41 statements for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinity, which participants grouped into seven clusters in the sorting activity. Table 3 shows the clusters, statements in each cluster, and the total average score for each cluster. Each cluster implies a key strategy for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinity, and each statement forms an action. From highest to lowest, the total averages were as follows: (7) Formal and informal education and training (4.61); (6) Preventive education and activities in different settings/areas (4.61); (2) Skills and knowledge (4.53); (1) Empathy, reflection, and understanding (4.42); (3) Media and public efforts (4.35); (5) Policy, legislation, and the criminal justice system (4.2); and (4) Organizational actions and interventions (4.2). Notably, the mean scores of the clusters were different for importance and applicability.

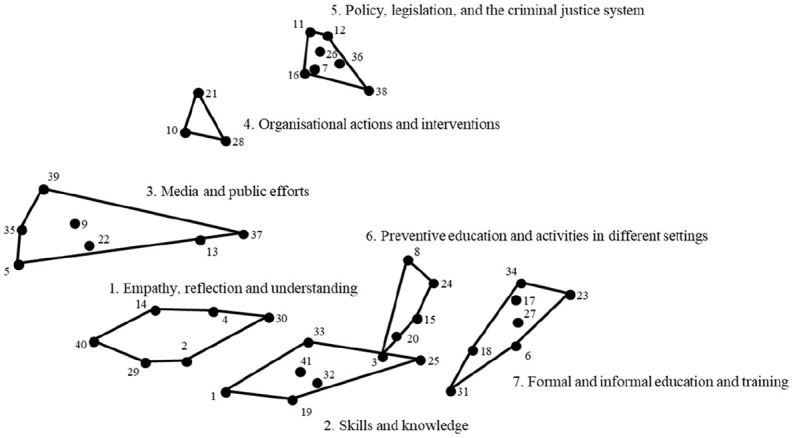

Cluster Map

The cluster map (Figure 1) shows proximity between clusters. The distance between these indicates how they relate with regard to similarity of content. For example, Cluster 5 on Policy, legislation, and the criminal justice system is far from Clusters 2, 6, and 7, which relate to providing knowledge and skills, prevention, education, but was closer to Cluster 4 on “Organizational actions and interventions.” The size of each cluster shows how close the statements in each cluster are. For example, Clusters 5 and 3 have a similar number of statements. However, Cluster 5 statements were sorted by more participants for similarity and put into this group compared to Cluster 3, where fewer participants sorted statements as belonging to this cluster. Cluster 6, about preventive educational activities, and Cluster 2, on Skills and knowledge, overlap, as Statement 3 (“promote positive, nonviolent, and respectful forms of parenting in parents’ groups during antenatal/postnatal care”) connects them both. Statement 3 was grouped by study participants as prevention, or as providing skills or knowledge.

Figure 1.

Cluster map for ideas to promote anti-VAW positive masculinity.

Note. VAW = violence against women.

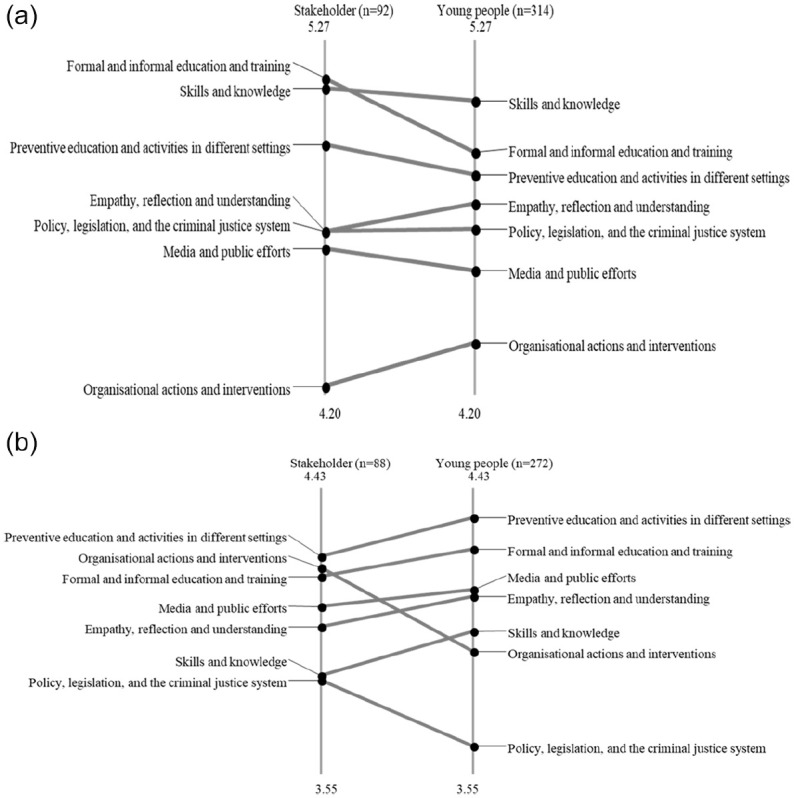

Pattern Match and Ranking the Clusters

We conducted “pattern match” to compare rankings of clusters in the study’s two groups of interest: young people and stakeholders. These comparisons related to ranking of the clusters by importance and applicability. Figure 2a shows the pattern match for importance among young people and for stakeholders, revealing a high correlation between ranking (r = 0.96) by these groups: they both ranked the clusters almost in the same order of importance. Only the first two clusters of “Formal and informal education and training” and “Skills and knowledge” differed: “Formal and informal education and training” was ranked of first importance among stakeholders, but second by young people, while “Skills and knowledge” was ranked of first importance by young people, but second by stakeholders.

Figure 2.

Pattern match for clusters’ ranking (a) by importance comparing young people versus stakeholders and (b) applicability comparing young people versus stakeholders.

Regarding applicability rankings (Figure 2b), the correlation was lower between stakeholders and young people (r = 0.60), with stakeholders ranking “Organizational actions and interventions” second, while young people ranked it sixth. It should be noted that in Figure 2a (importance), stakeholders use a wider scoring range, while in Figure 2b (applicability), it is young people who use a wider range.

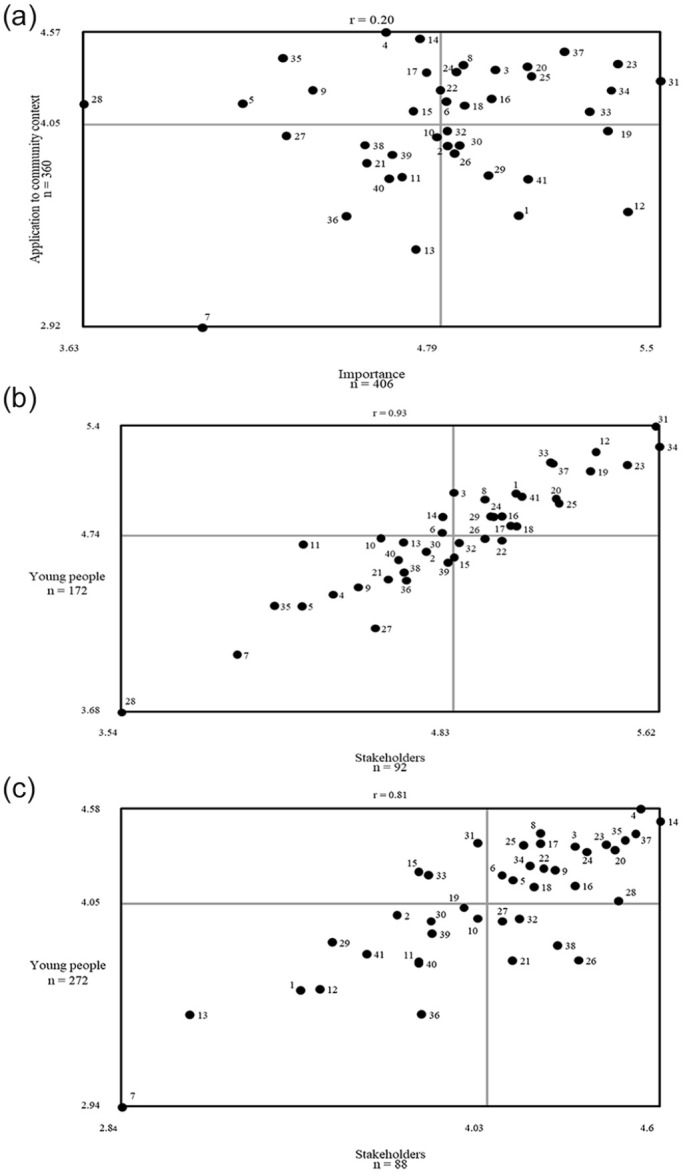

Go-Zones and Prioritization of Statements/Actions

The “Go-Zones” compare prioritization of all statements by groups of participants (Figure 3a). First, we compared prioritization of all statements by importance versus applicability among all participants (Figure 3a). This Go-Zone shows a low correlation (r = 0.20). This means participants who rated statements as highly important did not necessarily rate them as highly applicable for their community’s context.

Figure 3.

(a) Go-Zone and prioritization all statements by importance versus applicability for the total sample. (b) Go-Zone for importance among young participants versus stakeholders. (c) Go-Zone for applicability among young participants versus stakeholders.

Only 14 statements in the top right quadrant of the Go-Zone were ranked as being of high importance and applicability (Figure 3a). These included Statements 6, 23, 34, 31, and 18 (Cluster 7 on “Formal and informal education and training”); Statements 3, 8, 20, and 24 (Cluster 6 on “Prevention and educational activities in different settings”); Statement 16 (Cluster 5 on “Policy, legislation, and the criminal justice system”); Statements 22 and 37 (Cluster 3 on “Media and public efforts”); and Statements 33 and 25 (Cluster 2 “Skills and knowledge”) (Table 4). The mean scores for importance of the 14 statements were higher than those for applicability. Notably, none of the statements in Clusters 1 or 4 were ranked as both important and applicable.

Table 4.

Statements Prioritization as Both Important and Applicable by Participants (Mean Scores and Mean’s Difference).

| Importance (n = 406) |

Applicability (n = 360) |

Mean’s Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| 2. Skills and knowledge | ||||

| 33 | Develop women’s and men’s skills on how to recognize and actively prevent and stop VAW | 5.27 (1.1) | 4.12 (1.3) | 1.15 |

| 25 | Educate men and women on what nonviolent, trustworthy, and respectful romantic relationships look like | 5.08 (1.2) | 4.32 (1.3) | 0.76 |

| 3. Media and public efforts | ||||

| 22 | Promote age-relevant and relatable mass media representations of positive and nonviolent forms of manhood | 4.79 (1.2) | 4.24 (1.4) | 0.55 |

| 37 | Raise public awareness about the problem and extent of VAW, and public responsibility in preventing it | 5.19 (1.1) | 4.46 (1.3) | 0.73 |

| 5. Policy, legislation, and the criminal justice system | ||||

| 16 | Appoint more women in policy decision-making regarding VAW | 4.95 (1.3) | 4.19 (1.4) | 0.76 |

| 6. Preventive education and activities in different settings/areas | ||||

| 3 | Promote positive, nonviolent and respectful forms of parenting in parents’ groups during antenatal/post-natal care | 4.96 (1.2) | 4.35 (1.3) | 0.61 |

| 8 | Educate in workplaces about prevention of VAW | 4.86 (1.2) | 4.38 (1.4) | 0.48 |

| 20 | Provide education on what healthy, positive, and nonviolent forms of being a man looks like | 5.06 (1.3) | 4.37 (1.3) | 0.69 |

| 24 | Support and train youth groups, youth movements, student unions, gaming clubs, and different associations to promote a culture of gender equity and reject violent forms of manhood | 4.83 (1.3) | 4.34 (1.3) | 0.49 |

| 7. Formal and informal education and training | ||||

| 6 | Educate parents, children, and young people on the negative impacts of using pornography | 4.80 (1.4) | 4.17 (1.5) | 0.63 |

| 23 | Implement mandatory sex education and sexual consent education in schools, universities, and community programs | 5.36 (1.2) | 4.38 (1.6) | 0.98 |

| 34 | Ensure that age-appropriate compulsory education about gender stereotypes, equality, and VAW is integrated across the school curriculum, starting at a young age | 5.34 (1.1) | 4.24 (1.4) | 1.1 |

| 31 | Raise boys to respect women, reject VAW, and oppose unequal gender norms | 5.50 (1.0) | 4.29 (1.4) | 1.21 |

| 18 | Educate young people to recognize and reject gender stereotypes in the media and popular culture | 4.86 (1.3) | 4.15 (1.3) | 0.71 |

Note. VAW = violence against women.

Next, we compared prioritization of all statements by importance (Figure 3b) and applicability (Figure 3c) by young people versus stakeholders, and we found high agreement on importance (r = 0.93, Figure 3b) and high agreement on applicability (r = 0.81, Figure 3c).

Discussion

Using the CM study method (Kane & Trochim, 2007), we identified seven key strategies with actions and measures for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinity. The ranking from highest to lowest for these strategies or clusters was as follows: Formal and informal education and training; Preventive education and activities in different settings/areas; Skills and knowledge; Empathy, reflection, and understanding; Media and public efforts; Policy, legislation, and the criminal justice system; Organizational actions and interventions. This ranking was calculated by the mean scores for importance and applicability and might indicate an order for implementing these clusters.

Our findings include a range of ideas that incorporate different levels of action, target groups, and settings that could comprehensively promote anti-VAW positive masculinity and, by that, can help to create new norms and a broader culture of gender equity (Jewkes et al., 2015). The ideas comprehensively target not just young men, but also women, parents, teachers and educators, as well as other audiences, such as social media influencers, football players, filmmakers, services providers, policemen, judges, and the general public. Participants also proposed different settings where these audiences can be targeted, such as in families, communities, health-care facilities (e.g., pre- and postnatal care clinics), schools, workplaces, religious institutions, informal education institutions, ministries, sports clubs, student unions, youth movements, and women’s and men’s NGOs and associations.

These clusters/strategies also ranged in focus and level of intervention. The first level was prevention oriented, including activities like raising awareness, education in formal and informal institutions, providing skills and knowledge, and being empathetic and understanding toward women (Clusters 6, 7, 2, and 1). A second level of strategies focused on actions toward perpetrators of violence, such as increasing punishments for acts of IPV, improving treatment of VAW cases in the criminal justice system (Cluster 5), and providing support and training to organizations so they can implement perpetrator rehabilitation programs and interventions (Clusters 4 and 7). A third level of strategies aimed to change public opinion and using role models of gender equality and anti-VAW stances (Cluster 3). Finally, there was the level of advocacy, such as establishing an overriding authority to improve coordination between different authorities (Cluster 5).

These dynamic levels correspond with the WHO’s socio-ecological framework for tackling VAW, which incorporates multiple levels of action for prevention and treatment of VAW in society (Heise, 1998; Krug et al., 2002). However, our clusters add solutions for preventing and tackling VAW that aim to promote and support positive masculinity. As such it has a more comprehensive scope of interventions. These include the macro level of policy, laws, and creating a culture of gender equity (Clusters 5 and 3); the meso level of community horizontal work, including supporting institutions such as schools and informal educational settings, the health-care and welfare systems, and family and friends, for raising awareness on gender equity as a value that opposes VAW (Clusters 4, 6, and 7); and the micro individual level of changing knowledge, attitudes, and personal practices (Clusters 1 and 2).

It is worth noting that no cluster in our CM analysis was unidimensional. Rather, each interacts with others, showing a high level of dynamism. Some ideas for action (statements) can be shared in more than one cluster and implemented at more than one level of the socio-ecological model. For example, Statement 14 in Cluster 1, about the individual and family, relates to the microlevel and meso level in the socio-ecological model; and Statement 21 in Cluster 4, regarding budgets, relates to organizational action (meso level), but also needs policy (macro level) to support its implementation.

The strategies we identified in our study correspond with a recent qualitative review that pinpoints approaches for working with men to promote anti-VAW positive masculinity (Taliep et al., 2021), despite our study is a mixed methods bottom-up approach. The approaches presented in the literature review underline the importance of implementing a more positive approach when working with men, rather than pointing at them as perpetrators of VAW; using a more participatory approach that engages community stakeholders; combining multiple intervention strategies that consider the cultural context; and creating awareness to alter young people’s perceptions and behaviors (Taliep et al., 2021). Another approach can be found in a literature review on educational interventions to reduce IPV, GBV (Pérez-Martínez et al., 2021). The review found that these educational interventions should focus on a gender-transformative approach to promote positive masculinities to reduce these types of violence. Also future GBV interventions should combine content on gender equality with content on the costs of adhering to narrow constructions of masculinity for marginalized men (Pérez-Martínez et al., 2021)

Indeed, our findings indicate the need for a more comprehensive approach for prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation when working with young adults to promote anti-VAW positive masculinity. However, most current interventions for addressing VAW among young people focus on specific elements, rather than applying such a comprehensive approach (Casey et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2015). And, indeed, interventions that focus on one element, such as changing men’s attitudes, have been shown to be effective only for the short term (Jewkes et al., 2015). This implies that the dynamic approach arrived at by our participants might bring more lasting change.

Another important finding in our study related to the comparisons we made between rankings by between young people and stakeholders who volunteer or work in youth or women’s organizations or ministries offices. Our pattern-match analysis, which allows such comparisons, showed high agreement between the two groups in rankings of clusters of statements (representing ideas for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinity) for their importance. However, we found low agreement for applicability of statements/actions. We also found low agreement between importance and applicability in the Go-Zones analysis of prioritizing actions/statements. This discrepancy might relate to perceptions about effectiveness, and barriers such as lack of investment in VAW prevention via support and promotion of positive masculinity. Low applicability might relate to participants’ perceptions of barriers for implementation of these ideas, such as low financial feasibility of interventions and likelihood of economic support by governments in participating countries, specifically in interventions that focus on positive masculinity. Finally, lower agreement between young participants and stakeholders on applicability (compared to importance) might relate to the fact that young participants may lack experience in the areas that some statements refer to (e.g., stakeholders would have a better sense of the organizational and legal difficulties involved in implementation of some statements.). Therefore, the effectiveness of these interventions might be limited (Jewkes et al., 2015). Our multicountry findings showing a gap between importance and applicability might highlight the need to address obstacles for successful implementation of the study to strategies.

Furthermore, our Go-Zone analysis revealed high agreement on prioritization regarding only 14 statements. These statements reached high agreement for both importance and applicability and should be prioritized, despite the mean difference in scoring. Notably, most of these statements (12/14) relate to prevention, including formal and informal educational actions related to gender norms, raising awareness about VAW, and providing skills for promoting positive masculinity. The other two statements relate to representativeness of positive and nonviolent manhood in the media and appointment of more women in policy decision-making levels regarding VAW.

Strength and Limitations

Using the CM mixed method study to generate ideas and strategies for promoting anti-VAW positive masculinity as perceived by young adults and other stakeholders was a primary strength of this research. The CM blends quantitative and qualitative methods, study results are inductive, and interventions based on these ideas should be tailored to the study population (Kwok et al., 2020; Lobb et al., 2013). While we used purposeful sampling, which might reduce generalizability of results, our inclusion of young adults from four countries in Europe and the Middle East added strength to the study. Israel context is different from other Middle-Eastern counties, however it is still patriarchal society in terms of gender-equity. Our study participants included Jewish and Palestinian-Arab citizens in Israel which makes a unique study sample. Likewise, participants in the study were highly diverse, as we recruited young adults, as well as stakeholders, through social media and with the assistance of a variety of NGOs and governmental organizations working with youth and women to prevent VAW. However, our sample is not representative of all youth and stakeholders in the participating countries. One limitation was that we did not ask about involvement in VAW (as perpetrators or victims of VAW). Future research should explore ideas to promote positive masculinity among perpetrators of VAW and among victims of VAW. Solutions provided by participants incorporated a wide range of ideas applicable across contexts and societies for supporting and promoting at positive masculinity and tackling VAW at different levels and settings. Findings from a previous multicountry study (in Africa, North and South America, Australia, and Asia) conducted with 48 organizations (Casey et al., 2013) showed that programs and interventions that invite participation by men and boys have a mostly narrow focus on masculinity and do not incorporate gender equity or the intersectionality of other factors, such as class, gender orientation, nationality, or political or economic factors (Casey et al., 2013).

Conclusions and Recommendations for Policy

The seven strategies and 41 actions to promote anti-VAW positive masculinities produced in our mixed-methods CM study lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive, multilevel approach to ending VAW. Ranking of strategies by young people in four countries aligned closely with those of more seasoned stakeholders. The fact that study participants were skeptical about the applicability of ideas they considered important for promoting positive masculinity might speak to the pervasiveness of hegemonic masculinity. Most of the actions that are considered important but less feasible to implement focus of educating men or fostering their individual change. This highlights the need for policies that allocate more human and material resources to make these actions feasible.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the young people, professionals, and advisory board members who participated in this study.

Author Biographies

Nihaya Daoud, MPH, PhD, is a Professor of Public Health and a social epidemiologist at the School of Public Health at Ben Gurion University of the Negev. Her research focuses on health inequities and considers the impacts of discriminatory policies on minorities health and the intersections of ethnonational identity with gender and class. Her recent research focuses on violence against women, positive masculinity, and health-care system responses to violence.

Ayelet Carmi, PhD, is an art historian. Her research focuses on representations of masculinities in modern and contemporary American photography.

Robert Bolton, PhD, earned a PhD in Social Studies in 2018. His research deploys interactionist theory alongside an ethnographic approach to explore how young masculinities are performed.

Ariadna Cerdán-Torregrosa, PhD candidate, is a Sociologist of MSSc Research Methodology, a PhD Student in Gender Studies, and predoctoral researcher at the University of Alicante (Spain). Her research focuses on masculinities, gender-based violence, and public health.

Anna Nielsen, PhD, is a Registered Nurse/Midwife, with a Master Global Health and PhD in Medical Sciences. Her research focuses on sexual and reproductive health and rights among young people and public health.

Samira Alfayumi-Zeadna, MPH, PhD, is a social epidemiologist whose research interests include mental health, perinatal depression, social determinants of health, barriers to health-care and social services, and health intervention research.

Claire Edwards, MA, PhD, is the Director of the Institute for Social Science in the 21st Century (ISS21) at UCC. Her research sits at the intersection of social geography, social policy, and critical disability studies. Her most recent work focuses on disabled people’s fear and experience of violence and hostility, including gender-based violence.

Fiachra Ó Súilleabháin, MSW, DSocSc, is a Social Work academic and researcher in the School of Applied Social Studies, University College Cork, Ireland. His research focuses on sexualities and genders, violence against women and children, the scholarship of teaching and learning, and contemporary social work practice issues.

Belén Sanz-Barbero, MPH, PhD, is a Scientific Researcher at the Health Institute Carlos III (Spain) and Professor of Epidemiology at the National School of Public Health (Madrid, Spain). She is an expert in gender based violence from the stand point of Social Epidemiology analysis.

Carmen Vives-Cases, MPH, PhD, is Professor of Preventive Medicine and Public Health at the University of Alicante (Spain). She is Director of several research projects about violence against women, immigration, ethnic minorities and public health. She has authored more than 100 articles published in indexed journals and was awarded Doctor Honoris Causa by Umëa University (Sweden) in 2019.

Mariano Salazar, PhD, is a mixed-methods social epidemiologist. His research focuses on sexual and reproductive health, particularly at the intersections of gender-based violence, masculinities, and sexual health.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This work was part of a multisite study supported by GENDER NET Plus CoFund (reference number 2018-00968). It was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain (Ref. PCI2019-103580), the Swedish Research Council (Grant number: 2018-00968), the Irish Research Council, and the Ministry of Science & Technology of Israel (315662).

ORCID iDs: Nihaya Daoud  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4542-8978

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4542-8978

Ariadna Cerdán-Torregrosa  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1273-774X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1273-774X

Carmen Vives-Cases  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6797-5051

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6797-5051

Claire Edwards  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4325-0339

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4325-0339

References

- Casey E. A., Carlson J., Fraguela-Rios C., Kimball E., Neugut T. B., Tolman R. M., Edleson J. (2013). Context, challenges, and tensions in global efforts to engage men in the prevention of violence against women: An ecological analysis. Men and Masculinities, 16(2), 228–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey E. A., Ohler K. (2012). Being a positive bystander: Male antiviolence allies’ experiences of “stepping up”. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(1), 62–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conell R. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W., Messerschmidt J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Ueno K., Gordon M., Fincham F. D. (2013). The continuation of intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 75(2), 300–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud N., Berger-Polsky A., Sergienko R., O’Campo P., Leff R., Shoham-Vardi I. (2019). Screening and receiving information for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: A cross-sectional study of Arab and Jewish women of childbearing age in Israel. BMJ Open, 9(2), e022996–e022996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud N., Matheson F. I., Pedersen C., Hamilton-Wright S., Minh A., Zhang J., O’Campo P. (2016). Pathways and trajectories linking housing instability and poor health among low-income women experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV): Toward a conceptual framework. Women Health, 56(2), 208–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud N., Urquia M., O’Campo P., Heaman M., Janssen P., Smylie J., Thiessen K. (2012). Prevalence of abuse and violence before, during, and after pregnancy in a national sample of Canadian women. American Journal of Public Health, 102(10), 1893–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K. M., Mattingly M. J., Dixon K. J., Banyard V. L. (2014). Community matters: Intimate partner violence among rural young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(1–2), 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott K. (2015). Caring masculinities: Theorizing an emerging concept. Men and Masculinities, 19(3), 240–259. [Google Scholar]

- Fulu E., Jewkes R., Roselli T., Garcia-Moreno C. (2013). Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Global Health, 1(4), e187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C., Hegarty K., d’Oliveira A. F. L., Koziol-McLain J., Colombini M., Feder G. (2015). The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1567–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A., Jewkes R., Willan S., Washington L. (2018). Associations between poverty, mental health and substance use, gender power, and intimate partner violence amongst young (18-30) women and men in urban informal settlements in South Africa: A cross-sectional study and structural equation model. PLOS One, 13(10), e0204956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A., Washington L., Abdelatif N., Chirwa E., Willan S., Shai N., Jewkes R. (2020). Stepping stones and creating futures intervention to prevent intimate partner violence among young people: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(3), 323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. L. (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4(3), 262–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert A. (2021). Risk factors for intimate partner violence and abuse among adolescents and young adults: Findings from a UK population-based cohort. Wellcome Open Research, 5(176). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings W. G., Okeem C., Piquero A. R., Sellers C. S., Theobald D., Farrington D. P. (2017). Dating and intimate partner violence among young persons ages 15–30: Evidence from a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R., Flood M., Lang J. (2015). From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: A conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. Lancet, 385(9977), 1580–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R., Sikweyiya Y., Morrell R., Dunkle K. (2011). Gender inequitable masculinity and sexual entitlement in rape perpetration South Africa: Findings of a cross-sectional study. PLOS One, 6(12), e29590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W. L., Manning W. D., Giordano P. C., Longmore M. A. (2015). Relationship context and intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(6), 631–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M., Trochim W. M. K. (2007). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Krug E. G., Mercy J. A., Dahlberg L. L., Zwi A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok E. Y. L., Moodie S. T. F., Cunningham B. J., Oram Cardy J. E. (2020). Selecting and tailoring implementation interventions: A concept mapping approach. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb R., Pinto A., Lofters A. (2013). Using concept mapping in the knowledge-to-action process to compare stakeholder opinions on barriers to use of cancer screening among South Asians. Implementation Science, 8(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren R., Amin A. (2015). Addressing intimate partner violence and sexual violence among adolescents: Emerging evidence of effectiveness. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1 Suppl), S42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makleff S., Garduño J., Zavala R. I., Barindelli F., Valades J., Billowitz M., et al. (2020). Preventing intimate partner violence among young people—A qualitative study examining the role of comprehensive sexuality education. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17(2), 314–325. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A., Ellsberg M., Bott S. (2007). Addressing gender-based violence: A critical review of interventions. The World Bank Research Observer, 22(1), 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Martínez V., Marcos-Marcos J., Cerdán-Torregrosa A., Briones-Vozmediano E., Sanz-Barbero B., Davó-Blanes M., Daoud N., Edwards C., Salazar M., La Parra-Casado D, Vives-Cases C. (2021). Positive masculinities and gender-based violence educational interventions among young people: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15248380211030242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner L. M., Whitney S. D. (2010). Examining symmetry in intimate partner violence among young adults using socio-demographic characteristics. Journal of Family Violence, 25(2), 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas S. R., Kane M. (2012). Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: A pooled study analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(2), 236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J. D. (2012). From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2206–2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar M., Daoud N., Edwards C., Scanlon M., Vives-Cases C. (2020). PositivMasc: Masculinities and violence against women among young people. Identifying discourses and developing strategies for change, a mixed-method study protocol. BMJ Open, 10(9), e038797–e038797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar M., Öhman A. (2015). Negotiating masculinity, violence, and responsibility: A situational analysis of young Nicaraguan men’s discourses on intimate partner and sexual violence. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 24(2), 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Barbero B., Barón N., Vives-Cases C. (2019). Prevalence, associated factors and health impact of intimate partner violence against women in different life stages. PLOS One, 14(10), e0221049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Barbero B., López Pereira P., Barrio G., Vives-Cases C. (2018). Intimate partner violence against young women: Prevalence and associated factors in Europe. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 72(7), 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardinha L., Maheu-Giroux M., Stöckl H., Meyer S. R., García-Moreno C. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet, 399(10327), 803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckl H., March L., Pallitto C., Garcia-Moreno C. (2014). Intimate partner violence among adolescents and young women: Prevalence and associated factors in nine countries: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14, 751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliep N., Lazarus S., Naidoo A. V. (2021). A qualitative meta-synthesis of interpersonal violence prevention programs focused on males. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), Np1652–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Concept System®. (2022). groupwisdom™ (Build 2021.24.01) [Web-based Platform]. Ithaca, NY. Available from https://www.groupwisdom.tech [Google Scholar]

- Torres V. S., Goicolea I., Edin K., Öhman A. (2012). ‘Expanding your mind’: The process of constructing gender-equitable masculinities in young Nicaraguan men participating in reproductive health or gender training programs. Global Health Action, 5(1), 17262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trochim W., Kane M. (2005). Concept mapping: An introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 17(3), 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trochim W., McLinden D. (2017). Introduction to a special issue on concept mapping. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]